Abstract

BACKGROUND

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection leads to acute induction of Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) in the stomach that is associated with the initiation of gastritis. The mechanism by which H. pylori induces Shh is unknown. Shh is a target gene of transcription factor Nuclear Factor-κB (NFκB). We hypothesize that NFκB mediates H. pylori-induced Shh.

Materials and METHODS

To visualize Shh ligand expression in response to H. pylori infection in vivo, we used a mouse model that expresses Shh fused to green fluorescent protein (Shh::GFP mice) in place of wild-type Shh. In vitro, changes in Shh expression were measured in response to H. pylori infection using 3-dimensonal epithelial cell cultures grown from whole dissociated gastric glands (organoids). Organoids were generated from stomachs collected from the fundic region of control and mice expressing a parietal cell-specific deletion of Shh (PC-ShhKO mice).

RESULTS

Within 2 days of infection H. pylori induced Shh expression within parietal cells of Shh::GFP mice. Organoids expressed all major gastric cell markers, including parietal cell marker H+,K+-ATPase and Shh. H. pylori infection of gastric organoids induced Shh expression; a response that was blocked by inhibiting NFκB signaling and correlated with IκB degradation. H. pylori infection of PC-ShhKO mouse-derived organoids did not result in the induction of Shh expression.

CONCLUSION

Gastric organoids allow for the study of the interaction between H. pylori and the differentiated gastric epithelium independent of the host immune response. H. pylori induces Shh expression from the parietal cells, a response mediated via activation of NFκB signaling.

INTRODUCTION

Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) is a morphogen involved in the maintenance of gastric epithelial differentiation and function (1–3), and the initiation of the gastric immune response to Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection (4) and epithelial injury (5, 6). The dysregulation of Shh during inflammation may be seen as a global increase or decrease in expression during the innate to adaptive immune response. Initially Shh is up-regulated early in inflamed tissues of the gastrointestinal tract including that of H. pylori infection (4, 7). We have reported that H. pylori induces the release of Shh from the stomach within 2 days of infection (4). H. pylori-induced Shh subsequently acts as a macrophage chemoattractant during the initiation of gastritis (4). Here we extend our current knowledge through use of a novel in vitro fundic organoid model, by identifying the mechanism of H. pylori-induced Shh expression in the stomach and involvement of the H. pylori virulence factor, CagA, in this process.

NFκB activation is a critical step for the development of H. pylori-induced gastritis (8) and is associated with persistent infection (9). There are also a number of studies that demonstrate Shh to be a target gene of NFκB (10–12). Notably, binding sites for NFκB sub-units in the Shh promoter region of DNA have been located by sequence alignment (13). In vitro, NFκB induces Shh gene expression and signaling in human gastric cancer cell lines (14), and Shh is a known target gene of NFκB during tumor growth in the pancreas (13). However, in vivo studies investigating the mechanism of Shh induction are hindered due to recruitment of hematopoetic factors that may confound the interpretation of results. Thus assessing the direct involvement of H. pylori infection on NFκB activation and subseqently downstream regulation of Shh expression has been limited.

Gastric organoids are three-dimensional spheroids generated from the primary culture of murine gastric glands that express all major gastric cell lineages (15–17). Importantly, gastric organoids are isolated from the systemic response to infection thus making this culture system ideal for mechanistic studies investigating gene regulation in the epithelium in response to bacterial infection. Here we report the development and use of gastric organoids derived from whole dissocated glands of the corpus (or fundic) region of the stomach to study H. pylori-induced Shh expression specifically from the parietal cells. Stange et al. (18) demonstrate that Troy-positive chief cells may be used to generate long-lived gastric fundic organoids, but in vitro these cultures are differentiated toward the mucus-producing cell lineages of the neck and pit regions. The Troy-derived organoids are distinct from the cultures that are derived from whole dissociated glands reported here such that the parietal cells of the fundus are maintained.

The current work demonstrates that infection with H. pylori leads to Shh expression in the gastric epithelium via an NFκB mediated pathway, specifically within the acid-secreting parietal cell. Furthermore, these studies identify gastric organoids as a model for future studies into the epithelial response to infection as well as strain-specific factors involved in bacterial-epithelial interactions in the stomach.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Shh::GFP and PC-ShhKO mice

To visualize Shh ligand expression in response to H. pylori infection in vivo, we used a mouse model that expresses Shh fused to green fluorescent protein in place of wild-type Shh (Shh::GFP mice, The Jackson Laboratory, stock number 08466). GFP is inserted into the Shh protein such that secreted ligand retains both GFP and lipid modifications required for signaling. Genotyping was performed using polymerase chain reaction the forward primer (TGG TCC AAC CGA GTG AGA CA) for wild-type and mutant Shh, the reverse primer (TAA GTC CTT CAC CAG CTT GG) for wild-type Shh, and the reverse primer (AGC ACT GCA CGC CGT AGG TC) for mutant Shh. All mice were 8–10 weeks of age when inoculated.

Gastric organoids were generated from stomachs collected from 8–10 week old mice expressing a parietal cell-specific Shh deletion (PC-ShhKO). As published, PC-ShhKO mice were generated using transgenic animals bearing loxP sites flanking exon 2 of the Shh gene (Shh loxP, obtained from Dr J. A. Whitsett, Department of Pediatrics, University of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH, with permission from Dr A. P. McMahon, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA) and mice expressing a Cre transgene under the control of the H+,K+–adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase) β subunit promoter (HKCre, obtained from Dr J. Gordon, Washington University, St Louis, MO) (Xiao et al., 2010). Age-matched Shh loxP (homozygous for the loxP sites without the Cre transgene) and HKCre littermates were used to generate control gastric organoids. All mouse studies were approved by the University of Cincinnati Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) that maintains an American Association of Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) facility.

Helicobacter pylori culture and mouse inoculations

In the current study Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) strain G27 was used. H. pylori strain G27 was originally isolated from an endoscopy patient from Grosseto Hospital (Tuscany, Italy) (19). The G27 strain has been used extensively in H. pylori research because it is readily transformable and therefore amenable to gene disruption (20). Of relevance to the current study, strain G27 also efficiently delivers the translocated virulence factor CagA to cells in culture (21–25). Therefore, we chose G27 to study the mechanism of H. pylori-induced Shh expression using a strain that efficiently expresses virulence factor CagA. H. pylori strain G27 wild type (19) was grown on blood agar plates containing Columbia Agar Base (Fisher Scientific), 5% horse blood (Colorado Serum Company), 5 μg/ml vancomycin and 10 μg/ml trimethoprim as previously described (4). Plates were incubated for 2–3 days at 37°C in a humidified microaerophilic chamber (26). Bacteria were then harvested and re-suspended in filtered Brucella broth (BD Biosciences) supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum in a humidified microaerophilic chamber (BBL Gas System, with CampyPak Plus packs; BD Microbiology, Sparks, MD) in a shaking incubator at 37°C for 16 hours. Bacteria were harvested and used to inoculate mouse stomachs by oral gavage with 108 bacteria per 200 μL of Brucella broth. Uninfected mice received 200 μL of Brucella broth as control. Mice were analyzed 2 days post-inoculation.

H. pylori colonization was confirmed by quantitative cultures. Briefly, the wet weight of gastric tissue collected from uninfected and infected mice was measured. Tissue was then homogenized in 1 mL saline and a dilution of 1:1000 was spread on blood agar plates as described above. Plates were incubated for 5–10 days at 37°C in a humidified microaerophilic chamber. Single colonies from these plates tested positive for urease (BD Diagnostic Systems), catalase (using 3% H2O2), and oxidase (DrySlide; BD Diagnostic Systems).

Fundic gastric organoid generation and culture

Fundic gastric organoids were derived from the stomachs of age-matched (8–10 weeks) PC-ShhKO, Shh loxP (homozygous for the loxP sites without the Cre transgene) or HKCre littermates based on existing protocols (15) with modifications (16). After euthanasia, mouse stomachs were removed, opened along the greater curvature and washed in ice-cold Dulbecco’s Phosphate-Buffered Saline without magnesium and calcium (DPBS w/o Ca2+/Mg2+). Serosal muscle was stripped from the epithelium under a dissecting microscope using micro-dissecting scissors and fine forceps. Tissue was cut into approximately 5 mm2 pieces and incubated in DPBS (w/o Ca2+/Mg2+) supplemented with 5 mM EDTA (Sigma) with gentle rocking at 4°C for 2 hours. Tissue was then removed and transferred into 5 ml dissociation buffer (43.4 mM sucrose, 54.9 mM D-sorbitol (Sigma), in DPBS w/o Ca2+/Mg2+), and shaken vigorously for 2 minutes to dissociate whole glands from tissue. Medium containing dissociated glands was centrifuged at 150 g for 5 minutes, and the pellet re-suspended in matrigel (BD biosciences). Suspended glands in matrigel were added to 12 well culture plates or 2 well chamber slides (50 μl matrigel per well). Matrigel polymerization was achieved by incubating plates and slides at 37°C for 15–20 minutes. Glands suspended in matrigel were then overlaid with gastric organoid growth media made of Advanced Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium: Nutrient Mixture F-12 (DMEM/F-12, gibco by Life Technologies, 12634-010) Media supplemented with: Wnt-conditioned media (50%), R-spondin-conditioned media (10%), [Leu15]-Gastrin I (10 nM: Sigma), nAcetylcysteine (1mM: Sigma), FGF10 (100 ng/ml: Pepro Tech), EGF10 (50 ng/ml: Pepro Tech), Noggin (100 ng/ml: Pepro Tech), and Y-27632 (initial 4 days only, 10 nM, Sigma). Media was changed to fresh media every 4 days. For subsequent experiments, organoids cultured for 7 days were used.

Generating Wnt and R-spondin conditioned media

L cells (received as a gift from Dr. Hans Clevers, Hubrecht Institute for Developmental Biology and Stem Cell Research, Netherlands) were grown in T175 cm2 flasks (431080, Corning) in 40 ml Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium Glutamax 1 (DMEM plus Glutamax 1, 10569-010, gibco by Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin and zeocin (100mg/ml, Invitrogen) until 70–80% confluent. One flask of L cells was then passaged into 25 150mm×25mm cell culture dishes (430599, Corning) with 23 ml DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin and cultured for 7 days. Wnt conditioned media was collected and filtered through a 0.22 μm filter (27).

A modified HEK-293T R-spondin-secreting cell line was donated by Dr. Jeff Whitsett (Section of Neonatology, Perinatal and Pulmonary Biology, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and The University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, USA). Cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Once cells attached to plate, media is changed to OPTIMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Media was collected and filtered through a 0.22 μm filter after 7 days in culture. Both Wnt and R-spondin conditioned media activities were assayed by the TOPFlash assay. TOPFlash vector was kindly donated by Dr. Clevers.

Gastric organoid microinjections and treatments

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) strain G27 wild type (19) (CagA+) and a mutant G27 strain bearing a cagA deletion (ΔcagA::cat) (28) were grown on blood agar plates containing Campylobacter Base Agar, 5% horse blood, 5 μg/mL vancomycin, and 10 μg/mL trimethoprim as described above (see section Helicobacter pylori culture and mouse inoculations). Prior to microinjection, bacteria were resuspended in Brucella broth and checked for motility. H. pylori or Brucella broth was microinjected using the Nanoject II (Drummond) microinjector apparatus into 7 day old gastric organoids using a technique developed for Xenopus oocytes (29, 30) and enteroids (31). Injection needles were pulled on a horizontal bed puller (Sutter Instruments). In a separate series of experiments, organoids were pre-incubated with 10 μM of NFκB inhibitor IV ((E)-2-Fluoro-4′-methoxystilbene; EMD Biosciences, #481412) for 1 hour prior to microinjection. Approximately 200 nl of brucella broth containing 1×109 H. pylori per ml were injected per organoid. Approximately 2×105 bacteria were injected per organoid. As a negative control, Escherichia coli (E. coli K-12) bacteria were grown in brain heart infusion broth for 16 hours, harvested and approximately 2×105 bacteria injected per organoid. Twenty four hours post-injection, organoids were collected and washed with ice-cold PBS followed by RNA isolation using TRIzol® (Life Technologies). Quantitative cultures were used to confirm bacterial colonization of organoids at 24 hours post-injection by homogenization of organoids in saline followed by re-culture of bacteria on blood agar plates.

Confocal time lapse imaging microscopy

For fluorescence labeling, H. pylori were incubated with 5μM CFDA-SE (carboxyfluorescein diacetate, succinimidyl ester: Invitrogen) for 10 minutes, followed by 3 washes with Brucella broth prior to microinjection. Gastric organoids were grown on chambered coverglass (Thermo Scientific) time lapse imaging. Experiments were performed with coverglass in organoid culture media under 5% CO2 and 37°C conditions (incubation chamber, PeCon, Erbach, Germany). The chamber was placed on an inverted confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 710), and bacterial motility was monitored using a Zeiss EC plan-Neofluar ×10 objective. Transmitted light images were collected at 30 minute intervals.

Immunofluoresence and histology

Stomachs were embedded in Tissue-Tek® optimum cutting temperature (O.C.T) compound and sectioned longitudinally an 8 μm thickness and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes at room temperature. Sections were first blocked in 20% normal goat serum for 20 minutes at room temperature followed by a 1:200 dilution of rabbit polyclonal antibody to GFP (Abcam, ab290) at 4°C for 16 hours. Sections were then incubated by a 1:100 dilution of goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen, Carlasbad, CA) for 1 hour at room temperature, followed by a 1 hour room temperature incubation using a 1:1000 dilution of mouse anti-H+,K+ ATPase β subunit antibody (Affinity Bioreagents, MA3-923). Sections were then incubated with a 1:100 dilution of goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 633 secondary antibody (Invitrogen, Carlasbad, CA) for 1 hour at room temperature. Coverslips were mounted onto slides with Prolong Gold Antifade Reagent Mounting Medium (Molecular Probes) and analyzed with a Zeiss LSM510 META confocal microscope.

Organoids were harvested using ice-cold DPBS w/o Ca2+/Mg2+, and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes at room temperature. Organoids were centrifuged and embedded in Histogel (Thermo Scientific) followed by paraffin embedding. 5 μm sections were cut for and stained using hematoxylin eosin (H&E).

Whole mount staining was performed using organoids suspended in matrigel that were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes at room temperature, followed by permeablization with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 20 minutes. Organoids were then blocked in 20% normal rabbit for 20 minutes at room temperature. Fixed and permeabilized organoids were then incubated at 4°C for 16 hours with antibodies specific for H+/K+-ATPase (1:1000) and Shh (1:50, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-1194). Next, organoids were incubated with anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 and anti-goat Alexa Fluor 633 (1:100) for a further 16 hours at 4°C. After incubation with the secondary antibodies organoids were counterstained using nuclear stain (Hoechst 33342, 10μg/ml, Invitrogen) for 20 minutes at room temperature. Whole mount sections were visualized using the Zeiss LSM710.

Western blot analysis

Organoids were harvested from matrigel using ice-cold DPBS w/o Ca2+/Mg2+ and lysed in M-PER Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent (Thermo Scientific, IL) supplemented with protease inhibitors (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Cell lysates were resuspended in 40 μl Laemmli Loading Buffer containing beta-mercaptoethanol (Bio-Rad Laboratories, CA) before western blot analysis. Samples were loaded onto 4–20% Tris-Glycine Gradient Gels (Invitrogen) and run at 80 V, 3.5 hours before transfer to nitrocellulose membranes (Whatman Protran, 0.45 μM) at 105 V, 1.5 hours at 4°C. Membranes were blocked for 1 hour at room temperature using KPL Detector Block Solution (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Inc.). Membranes were incubated for 16 hours at 4°C with a 1:100 dilution of anti-IκBα antibody (Cell Signaling, #4814), 1:100 dilution of anti-IKKα (Cell Signaling, #2682) or 1:2000 dilution of anti-GAPDH (Millipore, MAB374) antibodies followed by a 1 hour incubation with a 1:1000 dilution anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 680 (Invitrogen). Blots were imaged using a scanning densitometer along with analysis software (Odyssey Infrared Imaging Software System).

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from gastric organoids using TRIzol® (Life Technologies) according to the mansufacturer’s protocol. The High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit was used for cDNA synthesis from 100 ng of RNA following the recommended protocol (Applied Biosystems). Predesigned real-time PCR assays were purchased for the following genes (Applied Biosystems): Pepsinogen C (Mm01278038_m1), Somatostatin (Mm00436671_m1), H+,K+-ATPase (Mm01176574), Gastrin (Mm00439059), Muc5AC (Mm01276711), Muc6 (Mm00725185), Shh (Mm00436528_m1), Ptch (Mm00970977_m1) and HPRT (Mm00446968_m1). PCR amplifications were performed in a total volume of 20 μL containing 20X TaqMan Expression Assay primers, 2X TaqMan Universal Master Mix (TaqMan Gene Expression Systems; Applied Biosystems), and complementary DNA template. Each PCR amplification was performed in duplicate wells in a StepOne Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) using the following conditions: 50°C for 2 minutes, 95°C for 10 minutes, 95°C for 15 seconds (denature), and 60°C for 1 minute (anneal/extend) for 40 cycles. Fold change was calculated as (Ct – Ct high) = n target, 2ntarget/2nGAPDH = fold change where Ct = threshold cycle. For experiments testing Shh induction, results were expressed as average fold change in gene expression relative to uninjected organoid group. HPRT was used as an internal control. Data were calculated according to Livak and Schmittgen (32).

Statistical Analyses

The significance of the results was tested by two-way ANOVA using commercially available software (GraphPad Prism, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). A P value <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

H. pylori induces Shh ligand expression within the gastric parietal cells

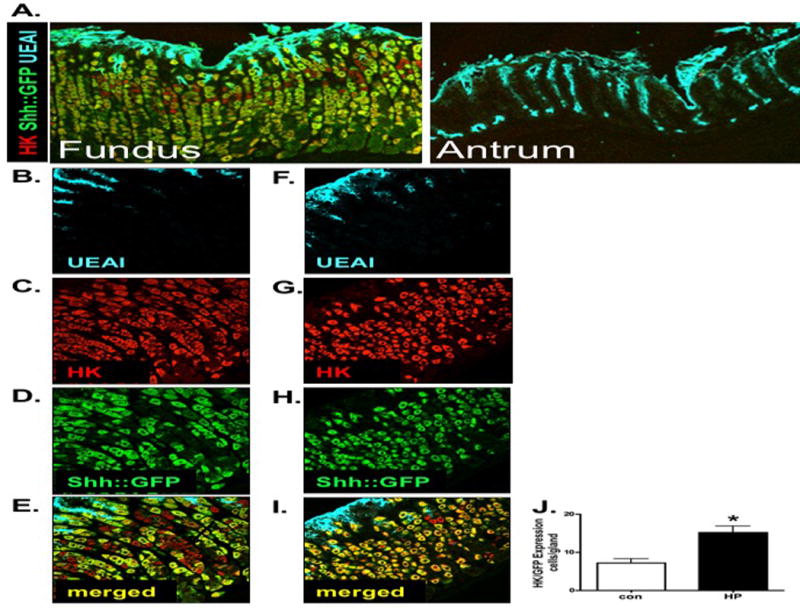

To visualize Shh ligand expression in response to H. pylori infection in vivo, we used a mouse model that expressed Shh fused to green fluorescent protein (Shh::GFP mice). Based on the expression pattern of GFP, we observed that Shh ligand was predominantly expressed within parietal cells of the fundic mucosa and absent from the antrum (Figure 1A). Expression of GFP within the parietal cells was identified by co-localization of H+,K+-ATPase and GFP (Figure 1A). Due to the lack of antral Shh expression, regulation of fundic Shh in response to H. pylori infection was studied for the remainder of the studies. While Shh was expressed within the parietal cells of uninfected mice, we observed that Shh::GFP was not expressed in every parietal cell (Figure 1B–E). Compared to the uninfected group, infected stomachs showed an increase in the number of parietal cell co-expressing Shh::GFP (Figure 1F–I). Quantification of the number of H+,K+-ATPase/Shh::GFP-positive cells revealed an increase in the number of H+,K+-ATPase/Shh::GFP co-expressing cells in response to H. pylori infection (Figure 1J). Collectively, these data show H. pylori infection induces Shh ligand expression within the parietal cells of the gastric epithelium within 2 days infection.

Figure 1. Parietal cell-expressed Shh.

(A) Fundic and antral sections were collected from stomachs of Shh::GFP mice an immunostained using antibodies specific for GFP (Shh-expressing cells, green), H+,K+-ATPase (parietal cells, red) and UEAI (surface pit cells, blue). Fundic sections collected from stomachs of Shh::GFP mice inoculated with (B–E) Brucella broth (controls) or (F–I) H. pylori were immunostained using antibodies specific for GFP (Shh-expressing cells, green), H+,K+-ATPase (parietal cells, red) and UEAI (surface pit cells, blue). (J) The number of cells co-expressing Shh::GFP and H+,K+-ATPase were quantified and expressed as cells/gland. Data is expressed as the mean ± SEM where *P<0.05 compared to controls, n = 6 mice per group.

Fundic gastric organoids express parietal cells, Shh and gastric cell lineage markers

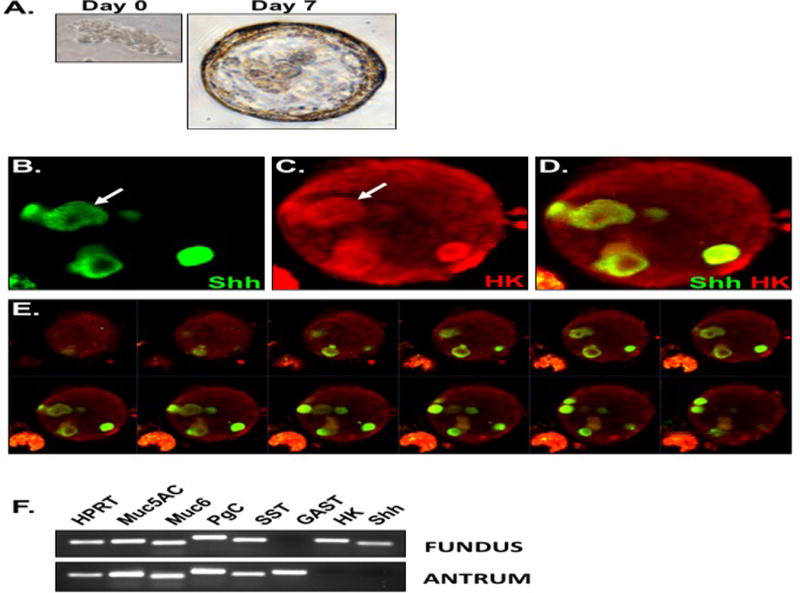

Figure 2 documents an organoid culture system for the fundic region of the mouse stomach using a modified protocol based on conditions described by Barker et al. (15) and optimized by our laboratory (16). Fundic gastric glands formed cyst-like structures that were visible within 4 days of culture and maintained this spheroid morphology at 7 days when organoids were large enough for microinjection (Figure 2A). Notably, 7 day gastric organoid cultures expressed both parietal cells and Shh that co-expressed within the same cells (Figure 2B–E). To further examine the cellular nature of the gastric organoids, we determined the gene expression of gastric-specific cell lineage markers at 7 days of culture. Both fundic and antral organoids expressed mucin 5AC (surface mucous pit cells), mucin 6 (mucous neck cells), pepsinogen C (zymogen/chief cells) and somatostatin (D cells) (Figure 2F). In contrast, the expression of gastrin (G cells) was specific to antral organoids, whereas H+,K+-ATPase (parietal cells) was specific to fundic organoids (Figure 2F). In support of our in vivo data using the Shh::GFP mouse model, Shh expression was not detected in antral gland-derived organoids when compared to the fundic cultures (Figure 2F). Therefore, due to the lack of antral Shh expression, regulation of Shh in response to H. pylori infection was studied in fundic gland-derived organoids. This expression profile indicated that our fundic organoids expressed the expected cell lineage genes representing the tissue from which they were derived. Importantly, the organoid cultures expressed Shh within the parietal cells that was consistent with the expression pattern observed in the native tissue.

Figure 2. Parietal cell-expressed Shh within mouse-derived fundic gastric organoids.

(A) Gastric glands grow into spheroids by day 7 in culture. Fundic organoids were immunostained using antibodies specific for (B) Shh (green) and (C) H+,K+-ATPase (parietal cells, red). Merged image is shown in (D). (E) Z stack of whole mount organoid shown in D demonstrating the presence of multiple parietal cells-expressing Shh. Images were collected at 1.5 μm intervals. (F) RNA extracted from fundic organoids was used to measure the expression of major gastric cell lineages including mucin 5AC (Muc5AC), mucin 6 (Muc6), pepsinogen C (PgC), somatostatin (SST), gastrin (GAST), H+,K+-ATPase (HK) and Shh using RT-PCR.

Fundic gastric organoids are colonized by H. pylori after microinjection

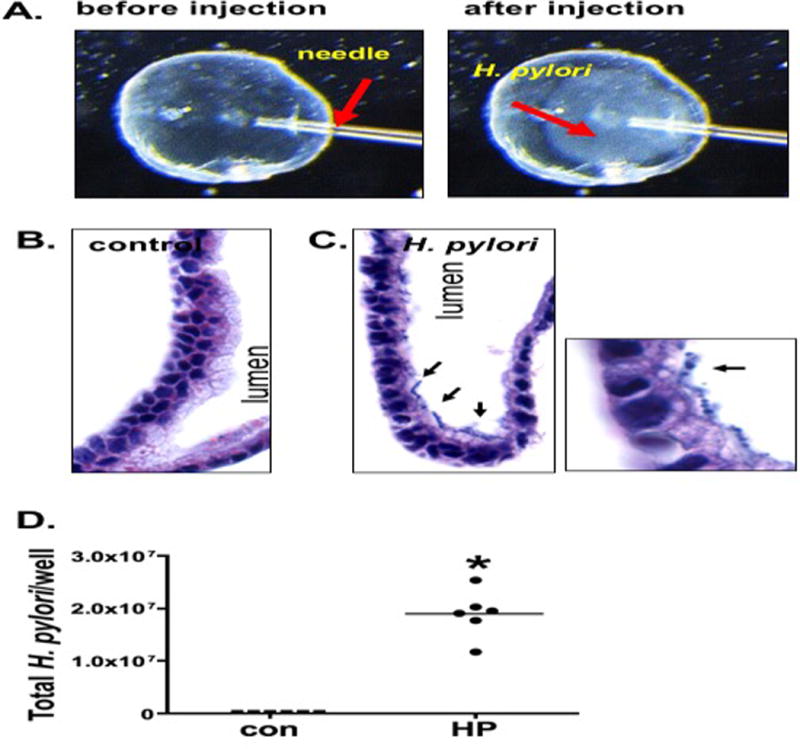

To identify the role of NFκB signaling as a mediator of H. pylori-induced Shh expression, 7 day old fundic organoids were intra-luminally microinjected with 2 × 105 bacteria/organoid using a Drummond Nanoject II nanoliter injector (Figure 3A). Figure 3A shows the organoid prior to injection with the needle inserted. The bacteria appeared as a hazy area within the organoid upon injection (Figure 3A, arrow). Colonization was documented by histological evaluation using H&E staining. Bacteria appeared on the epithelium within the lumen of infected organoids (Figure 3C) compared to the uninfected organoids (Figure 3B). Time lapse microscopy using organoids infected with fluorescently-labelled H. pylori documented colonization of the organoid epithelium by motile bacteria (video 1). Quantitative cultures further confirmed colonization of the organoids by H. pylori 24 hours post-injection (Figure 3D). Collectively, we show that fundic gastric organoids microinjected with H. pylori maintain motility post-injection and adhere to the epithelial cells on the luminal side at the time of analysis.

Figure 3. H. pylori infection of fundic organoids.

(A) Micro-injection of H. pylori into fundic organoids. H. pylori appears as a cloud within the organoid. H&E of organoid sections microinjected with (B) culture media or (C) H. pylori. Arrows in C show H. pylori attachment to epithelium of fundic gastric organoids. (D) Quantitative cultures of control (con) and H. pylori (HP) infected organoids.

NFκB signaling mediates H. pylori-induced Shh expression

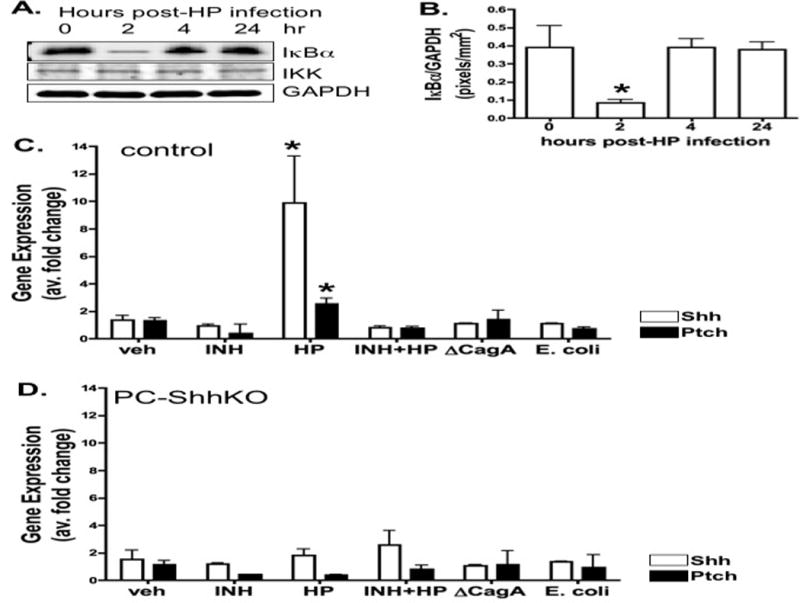

Using the fundic organoid culture model detailed in Figure 3, the role of NFκB signaling as a mediator of H. pylori-induced Shh expression was identified. Inhibitory IκBα is an inhibitory protein that complexes with NFκB subunits in the cytoplasm, thus preventing translocation of NFκB subunits to the nucleus. Activation of NFκB signaling pathway results in phosphoryation allowing for proteosome-mediated degradation of IκBα, removing the inhibitory effect and allowing NFκB subunits to enter the nucleus to regulate gene transduction (Brown et al., 1993). NFκB activation was confirmed by western blot for IκBα demonstrating a reduction at 2 hours post-infection (Figure 4A, B). As IκBα is a target gene of canonical NFκB signaling, re-expression of IκBα at 4 hours post-injection further indicates NFκB pathway activation (Figure 4A, B). The data show that H. pylori infection induced activation of NFκB signaling pathway in the fundic gastric organoid cultures.

Figure 4. H. pylori-induced NFκB activation and Shh expression.

(A) NFκB status was measured using protein lysates extracted from organoids infected with H. pylori for 0, 2, 4, and 24 hours. Changes in IκBα, IKKα and GAPDH expression were measured by western blot. Quantification of Changes in IκBα relative to GAPDH is shown in B. Data are expressed as the mean + SEM, where *P<0.05 compared to time 0 hours, n = 3 individual organoid cultures. Organoids were derived from the fundus of (C) control or (D) PC-ShhKO mice. Organoids were treated with vehicle (veh), NFκB inhibitor alone (INH) or NFκB inhibitor pre-treatment followed by H. pylori infection (HP+INH), and H. pylori infection alone (HP). Shh and Ptch expression was analyzed by qRT-PCR 24 hours post-infection. *P<0.05 compared to veh group, n=6 individual wells per group.

To identify the role of NFκB signaling as a mediator of H. pylori-induced Shh expression, organoids were cultured from either control mouse stomachs or mice expressing a parietal cell-specific Shh deletion (PC-ShhKO mice). While Shh expression was significantly induced in response to H. pylori infection in the control organoids (Figure 4C), H. pylori-induced expression was absent in the PC-ShhKO-derived cultures (Figure 4D). Importantly, 1 hour pretreatment with NFκB inhibitor IV blocked H. pylori-induced Shh expression in control organoid cultures (Figure 4C). The H. pylori mutant strain lacking CagA (ΔCagA) did not induce Shh expression suggesting that the response to H. pylori was CagA-dependent (Figure 4C). In addition, to test whether other bacteria induce Shh we tested the common E. coli bacterial strain and observed that the induction of Shh was specific to H. pylori infection (Figure 4C). Changes in Hedgehog signaling target genes Patched (Ptch) and Gli1 in response to H. pylori infection were also measured by qRT-PCR. An approximate 2-fold induction in Ptch in response to H. pylori infection was observed in the control mouse fundic-derived organoids (Figure 4C), but absent in PC-ShhKO mouse-derived organoids (Figure 4D). Gli1 expression was not detected in the gastric fundic organoids (data not shown). Collectively, these data demonstrate that H. pylori-induced Shh expression is mediated by NFκB signaling and is CagA-dependent.

DISCUSSION

We have reported that H. pylori induces the expression and release of Shh from the stomach within 2 days of infection (4). Here we extend our current knowledge by identifying a mechanism by which H. pylori induces Shh expression in the stomach. Our study demonstrates that: 1) in mice expressing a fluorescently-tagged processed Shh ligand (Shh::GFP) H. pylori induces Shh expression almost exclusively within the parietal cells, and 2) using a novel gastric organoid model NFκB signaling mediates H. pylori-induced Shh expression.

The expression pattern of Shh in response to infection was studied using gastric sections collected from Shh::GFP mice inoculated with H. pylori. Shh::GFP expression was clearly co-expressed within the parietal cells that were readily identified by their distinctive morphology and abundance within the neck compartment of the gastric unit and stained positive for H+,K+-ATPase. We also observed expression of Shh within the surface pit cells. The expression of Shh was also confined to the fundic region of the stomach and absent from the antrum. These data are consistent with other studies including analysis of stomachs collected from mouse, Mongolian gerbils, and human demonstrating the expression of Shh within parietal cells and the surface pit cells (1, 3, 14, 33–35). Based on our data, H. pylori did not induce Shh expression within organoids derived from PC-ShhKO mouse stomachs. Given that these organoids express a parietal cell-specific deletion of Shh, these data suggest that H. pylori-induced Shh expression is specific to the parietal cells.

Using gastric organoids derived from control mice, Shh expression was rapidly induced in response to H. pylori infection, a response that was not observed in organoids derived from PC-ShhKO mouse stomachs. Moreover, H. pylori-induced Shh expression was inhibited by NFκB inhibitor treatment. Thus, extending existing knowledge within published data (13, 14) we find that NFκB signaling mediates H. pylori-induced Shh expression and may explain the early up-regulation of Shh observed in the inflamed stomach (4). Furthermore, the temporal regulation of canonical NFκB signaling was demonstrated to be intact within gastric organoids whereby such degradation of IκBα lead to its re-expression by 4 hours post-injection (36). In support of our findings, Shh is a known target gene of NFκB during tumor growth in pancreas (13) and in human gastric cancer cell lines, NFκB induces Shh gene expression and signaling (14). Using an immortalized gastric cancer cell line, it has been shown that incubation with H. pylori leads to translocation of NFκB p65/p50 heterodimer and p50 homodimer to the nucleus (37). NFκB activation has also been observed in gastric tissue specimens from infected patients (37). Kasperczyk et al. identified that NFκB sub-units bind to the Shh promoter region of DNA (13) thus demonstrating a capacity for NFκB to directly regulate Shh expression at the transcriptional level. Indeed, studies have linked the activation of NFκB in cancer cell lines to expression of Shh. Induction of Shh, Patched, and Gli1 in gastric cancer cells by H. pylori was shown to be inhibited by pre-treatment with the NFκB inhibitor PTDC (10).

H. pylori-induced Shh expression was lost in response to infection with a mutant strain lacking CagA (ΔCagA). The H. pylori virulence factor, CagA plays a pivotal role in the etiology of disease (38, 39). In support of our data, experiments performed in gastric cancer cells report that Shh, Ptch, and transcription factor Gli1 were overexpressed in response to H. pylori infection. Notably, infection with CagA positive H. pylori resulted in significantly higher Shh expression (10). Such data suggest that the induction of Shh expression in response to H. pylori infection may be CagA-dependent.

Collectively these studies demonstrate a capacity for NFκB signaling to induce Shh expression in the stomach. Until now, the use of cancer cell lines that are not representative of native tissue have precluded the ability to identify the cell type in which this induction occurs and to definitively demonstrate H. pylori induces Shh via an NFκB dependent mechanism in the stomach. The development and use of fundic gastric organoids allows us to demonstrate that H. pylori interactions with the epithelium lead to NFκB-mediated Shh induction specifically from the parietal cell. These studies reveal the utility of fundic organoids for studies of strain-specific H. pylori factors that mediate pathogenecity.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Video 1: Confocal imaging of CFDA-SE labeled H. pylori motility within the lumen of a fundic organoid by confocal microscopy.

Acknowledgments

DISCLOSURES

This work was supported by NIH 1R01DK083402 grant (Zavros) and the Albert J. Ryan Fellowship and University of Cincinnati Graduate School Dean’s Fellowship (Schumacher). This project was supported in part by PHS Grant P30 DK078392 (Integrative Morphology Core) of the Digestive Diseases Research Core Center in Cincinnati. We gratefully acknowledge Drs. Meritxell Huch, Sina Bartfeld, and Hans Clevers (Hubrecht Institute for Developmental Biology and Stem Cell Research, Netherlands) for the kind gift of L-cells and the technical discussion. We also acknowledge Dr. Jeffrey Whitsett for kindly donating the modified HEK-293T cells (Section of Neonatology, Perinatal and Pulmonary Biology, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and The University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, OH).

Abbreviations

- H. pylori

Helicobacter pylori

- Shh

Sonic Hedgehog

- NFκB

Nuclear Factor-κB

- PC-ShhKO

mice expressing a parietal cell-specific Shh deletion

- DPBS w/o Ca2+/Mg2+

Dulbecco’s Phosphate-Buffered Saline without magnesium and calcium

- DMEM/F-12

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium: Nutrient Mixture F-12

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Xiao C, Ogle SA, Schumacher MA, Orr-Asman MA, Miller ML, Lertkowit N, Varro A, Hollande F, Zavros Y. Loss of Parietal Cell Expression of Sonic Hedgehog Induces Hypergastrinemia and Hyperproliferation of Surface Mucous Cells. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:550–561. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van den Brink GR, Hardwick JC, Nielsen C, Xu C, ten Kate FJ, Glickman J, van Deventer SJ, Roberts DJ, Peppelenbosch MP. Sonic hedgehog expression correlates with fundic gland differentiation in the adult gastrointestinal tract. Gut. 2002;51:628–633. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.5.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zavros Y, Orr MA, Xiao C, Malinowska DH. Sonic hedgehog is associated with H+,K+-ATPase-containing membranes in gastric parietal cells and secreted with histamine stimulation. Am J Physiol. 2008;295:G99–G111. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00389.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schumacher MA, Donnelly JM, Engevik AC, Xiao C, Yang L, Kenny S, Varro A, Hollande F, Samuelson LC, Zavros Y. Gastric Sonic Hedgehog Acts as a Macrophage Chemoattractant During the Immune Response to Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1150–1159. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xiao C, Feng R, Engevik A, Martin J, Tritschler J, Schumacher M, Koncar R, Roland J, Nam K, Goldenring J, Zavros Y. Sonic Hedgehog contributes to gastric mucosal restitution after injury. Lab Invest. 2013;93:96–111. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2012.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engevik AC, Feng R, Yang LYZ. The Acid-secreting parietal cell as an endocrine source of sonic hedgehog during gastric repair. Endocrinology. 2013;154:4627–4639. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nielsen CM, W J, van den Brink GR, Lauwers GY, Roberts DJ. Hh pathway expression in human gut tissues and in inflammatory gut diseases. Lab Invest. 2004;84:1631–1642. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrero RL, Avé P, Ndiaye D, Bambou JC, Huerre MR, Philpott DJ, Mémet S. NF-kappaB activation during acute Helicobacter pylori infection in mice. Infect Immun. 2008;76:551–561. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01107-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brandt S, Kwok T, Hartig R, König W, Backert S. NF-kappaB activation and potentiation of proinflammatory responses by the Helicobacter pylori CagA protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9300–9305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409873102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim JH, Choi YJ, Lee SH, Shin HS, Lee IO, Kim YJ, Kim H, Yang WI, Kim H, Lee YC. Effect of Helicobacter pylori infection on the sonic hedgehog signaling pathway in gastric cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2010;23:1523–1528. doi: 10.3892/or_00000791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh AP, Arora S, Bhardwaj A, Srivastava SK, Kadakia MP, Wang B, Grizzle WE, Owen LB, Singh S. CXCL12/CXCR4 protein signaling axis induces sonic hedgehog expression in pancreatic cancer cells via extracellular regulated kinase- and Akt kinase-mediated activation of nuclear factor κB: implications for bidirectional tumor-stromal interactions. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:39115–39124. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.409581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghorpade DS, Sinha AY, Holla S, Singh V, Balaji KN. NOD2-nitric oxide-responsive microRNA-146a activates Sonic hedgehog signaling to orchestrate inflammatory responses in murine model of inflammatory bowel disease. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:33037–33048. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.492496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kasperczyk H, Baumann B, Debatin KM, Fulda S. Characterization of sonic hedgehog as a novel NF-kappaB target gene that promotes NF-kappaB-mediated apoptosis resistance and tumor growth in vivo. FASEB J. 2009;23:21–33. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-111096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Zaatari MTA, Grabowska AM, Kumari R, Scotting PJ, Kaye P, Atherton J, Clarke PA, Powe DG, Watson SA. De-regulation of the sonic hedgehog pathway in the InsGas mouse model of gastric carcinogenesis. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:1855–1861. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barker N, Huch M, Kujala P, van de Wetering M, Snippert HJ, van Es JH, Sato T, Stange DE, Begthel H, van den Born M, Danenberg E, van den Brink S, Korving J, Abo A, Peters PJ, Wright N, Poulsom R, Clevers H. Lgr5(+ve) stem cells drive self-renewal in the stomach and build long-lived gastric units in vitro. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahe MM, Aihara E, Schumacher MA, Zavros Y, Montrose MH, Helmrath MA, Sato T, Shroyer NF. Establishment of Gastrointestinal Epithelial Organoids. Current Protocols in Mouse Biology. 2013;3:217–240. doi: 10.1002/9780470942390.mo130179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng R, Aihara E, Kenny S, Y L, Li J, Varro A, Montrose MH, Shroyer N, Wang TC, Shivdasani RA, Zavros Y. Indian Hedgehog Mediates Gastrin-Induced Proliferation in Stomach of Adult Mice. Gastroenterology. 2014 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stange DE, Koo BK, Huch M, Sibbel G, Basak O, Lyubimova A, Kujala P, Bartfeld S, Koster J, Geahlen JH, Peters PJ, van Es JH, van de Wetering M, Mills JC, Clevers H. Differentiated Troy+ chief cells act as reserve stem cells to generate all lineages of the stomach epithelium. Cell. 2013;155:357–368. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Covacci A, Censini S, Bugnoli M, Petracca R, Burroni D, Macchia G, Massone A, Papini E, Xiang Z, Figura N, et al. Molecular characterization of the 128-kDa immunodominant antigen of Helicobacter pylori associated with cytotoxicity and duodenal ulcer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:5791–5795. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Censini S, Lange C, Xiang Z, Crabtree JE, Ghiara P, Borodovsky M, Rappuoli R, Covacci A. cag, a pathogenicity island of Helicobacter pylori, encodes type I- specific and disease-associated virulence factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:14648–14653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amieva MR, Vogelmann R, Covacci A, Tompkins LS, Nelson WJ, Falkow S. Disruption of the epithelial apical-junctional complex by Helicobacter pylori CagA. Science. 2003;300:1430–1434. doi: 10.1126/science.1081919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El-Etr SH, Mueller A, Tompkins LS, Falkow S, Merrell DS. Phosphorylation-independent effects of CagA during interaction between Helicobacter pylori and T84 polarized monolayers. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:1516–1523. doi: 10.1086/424526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guillemin K, Salama NR, Tompkins LS, Falkow S. Cag pathogenicity island-specific responses of gastric epithelial cells to Helicobacter pylori infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:15136–15141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182558799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stein M, Rappuoli R, Covacci A. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the Helicobacter pylori CagA antigen after cag-driven host cell translocation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:1263–1268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Segal ED, Cha J, Lo J, Falkow S, Tompkins LS. Altered states: involvement of phosphorylated CagA in the induction of host cellular growth changes by Helicobacter pylori. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:14559–14564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee A, O’Rourke J, Ungria MCd, Robertson B, Daskalopoulos G, Dixon MF. A standardized mouse model of Helicobacter pylori infection: Introducing the Sydney Strain. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1386–1397. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bell SM, Schreiner CM, Wert SE, Mucenski ML, Scott WJ, Whitsett JA. R-spondin 2 is required for normal laryngeal-tracheal, lung and limb morphogenesis. Development. 2008;135:1049–1058. doi: 10.1242/dev.013359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amieva MR, Salama NR, Tompkins LS, Falkow S. Helicobacter pylori enter and survive within multivesicular vacuoles of epithelial cells. Cell Microbiology. 2002;4:677–690. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2002.00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cunningham SA, Worrell RT, Benos DJ, Frizzell RA. cAMP-stimulated ion currents in Xenopus oocytes expressing CFTR cRNA. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:C783–788. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.262.3.C783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hitchcock MJ, Ginns EI, Marcus-Sekura CJ. Microinjection into Xenopus oocytes: equipment. Methods Enzymol. 1987;152:276–284. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)52031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Engevik MA, Aihara E, Montrose MH, Shull GE, Hassett DJ, Worrell RT. Loss of NHE3 alters gut microbiota composition and influences Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron growth. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2013;305:G697–711. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00184.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Livak K, Schmittgen T. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suzuki H, Minegishi Y, Nomoto Y, Ota T, Masaoka T, van den Brink GR, Hibi T. Down-regulation of a morphogen (sonic hedgehog) gradient in the gastric epithelium of Helicobacter pylori-infected Mongolian gerbils. J Pathol. 2005;206:186–197. doi: 10.1002/path.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shiotani A, Iishi H, Uedo N, Ishiguro S, Tatsuta M, Nakae Y, Kumamoto M, Merchant JL. Evidence that loss of sonic hedgehog is an indicator of Helicobater pylori-induced atrophic gastritis progressing to gastric cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:581–587. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.El-Zaatari MGA, McKenzie AJ, Powe DG, Scotting PJ, Watson SA. Cyclopamine inhibition of the sonic hedgehog pathway in the stomach requires concomitant acid inhibition. Regul Pept. 2008;146:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2007.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoffmann A, Levchenko A, Scott ML, Baltimore D. The IkappaB-NF-kappaB signaling module: temporal control and selective gene activation. Science. 2002;298:1241–1245. doi: 10.1126/science.1071914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keates S, Hitti YS, Upton M, Kelly CP. Helicobacter pylori infection activates NF-kB in gastric epithelial cells. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1099–1109. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9322504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peek RM, Jr, Miller GG, Tham KT, Perez-Perez GI, Zhao X, Atherton JC, Blaser MJ. Heightened inflammatory response and cytokine expression in vivo to cagA+ Helicobacter pylori strains. Lab Invest. 1995;73:760–770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blaser JM, Perez-Perez GI, Kleanthous H, et al. Infection with Helicobacter pylori strains possessing cagA is associated with an increased risk of developing adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Cancer Research. 1995;55:2111–2115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Video 1: Confocal imaging of CFDA-SE labeled H. pylori motility within the lumen of a fundic organoid by confocal microscopy.