Abstract

`Primary' pulmonary hypertension, which is rare in western countries, was found to be relatively common in Ceylon.

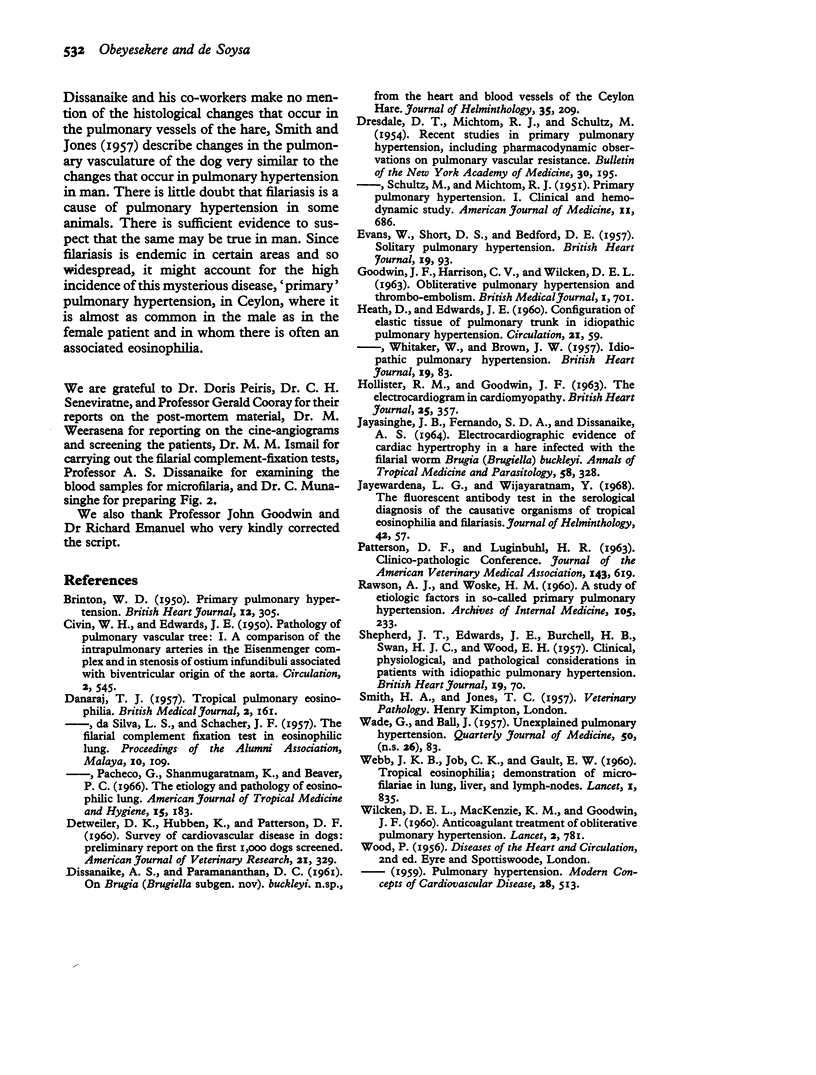

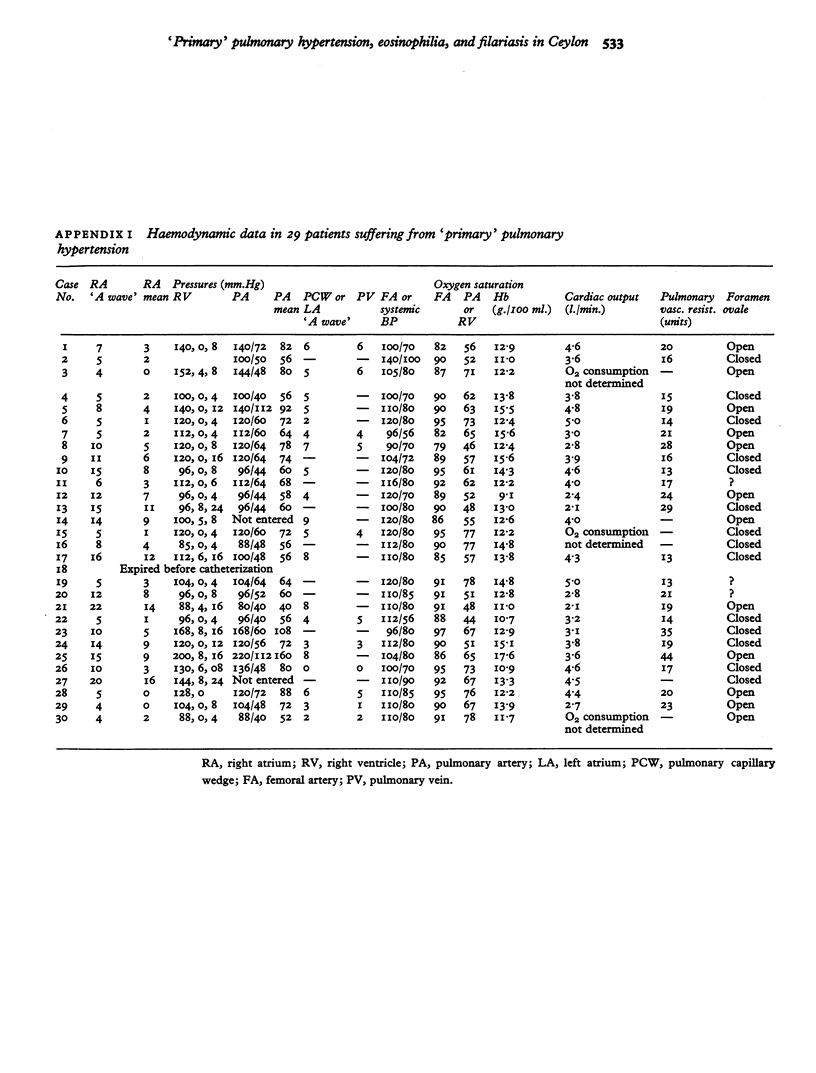

The clinical and haemodynamic features were studied. There were two distinct types of the disease, malignant and benign. Patients with the malignant form of the disease had a rapidly progressive illness of short duration and an invariably fatal outcome. Those with the benign form gave a long history and, in spite of severe pulmonary hypertension, were only slightly disabled. They seemed to tolerate the disease better. An important factor which determined the clinical course of the disease was the patency of the foramen ovale. This appeared to act as a safety valve permitting a right-to-left shunt in times of stress. The foramen ovale was closed in all patients with the malignant type. The therapeutic implications of this need further study.

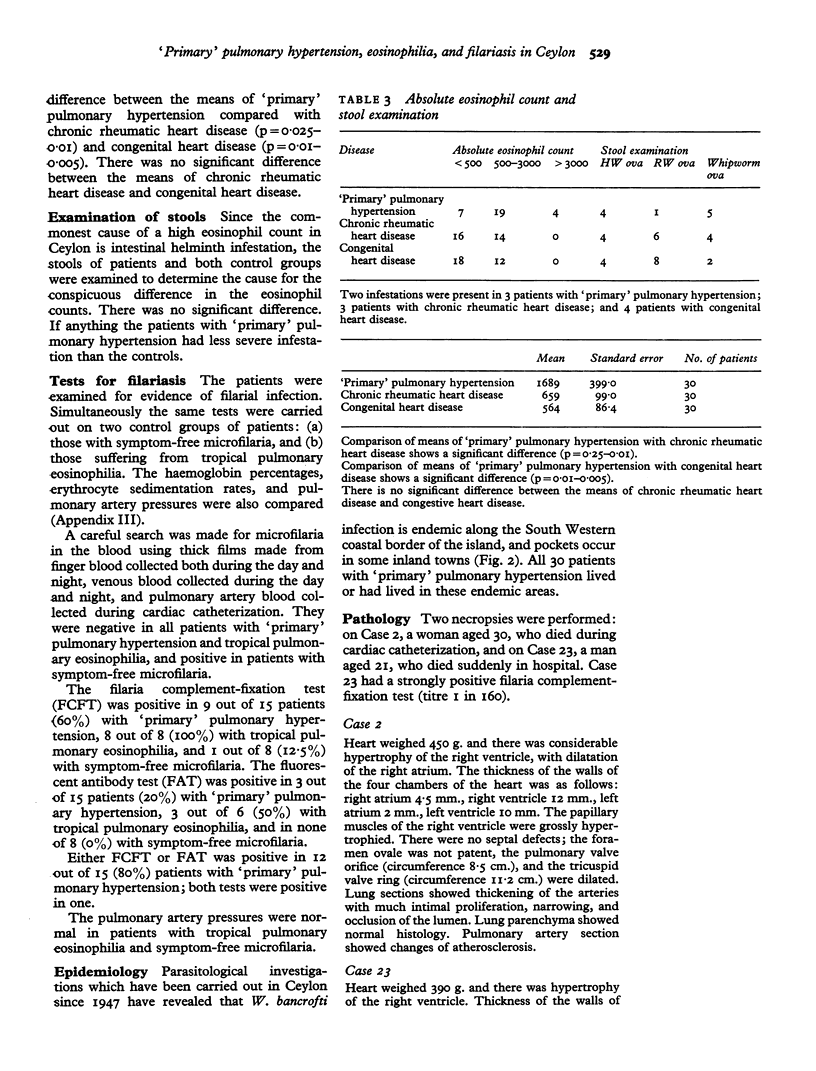

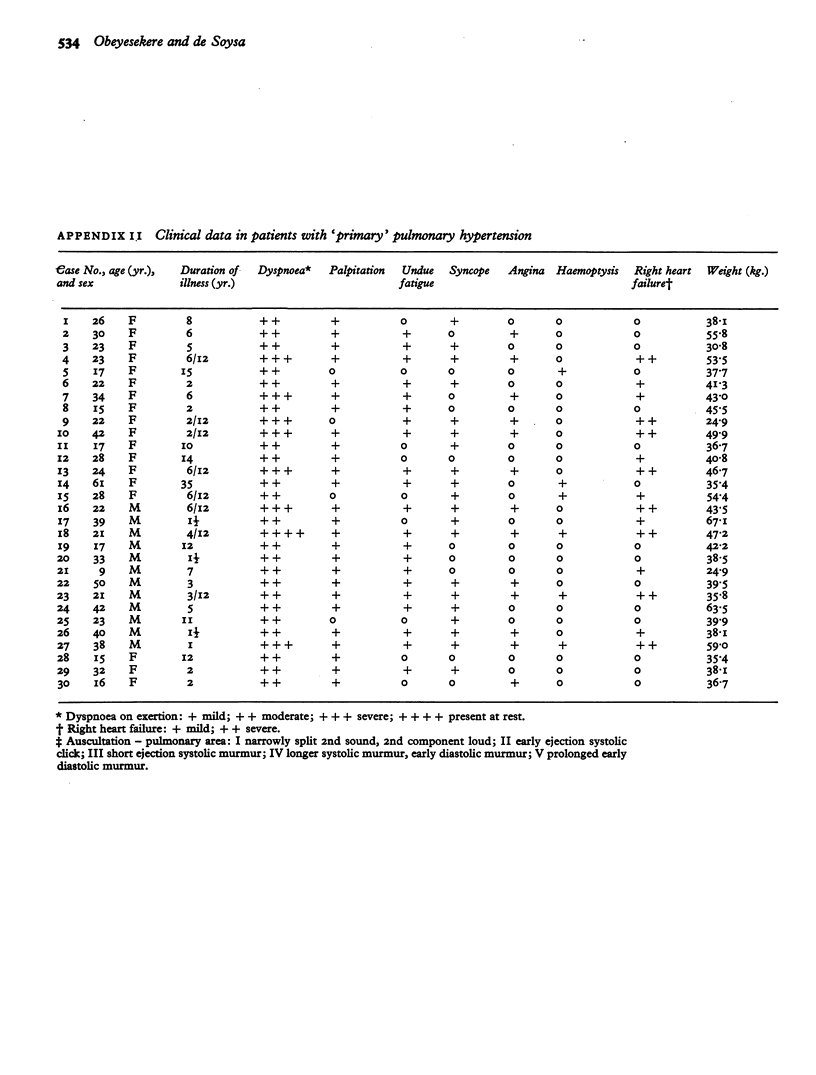

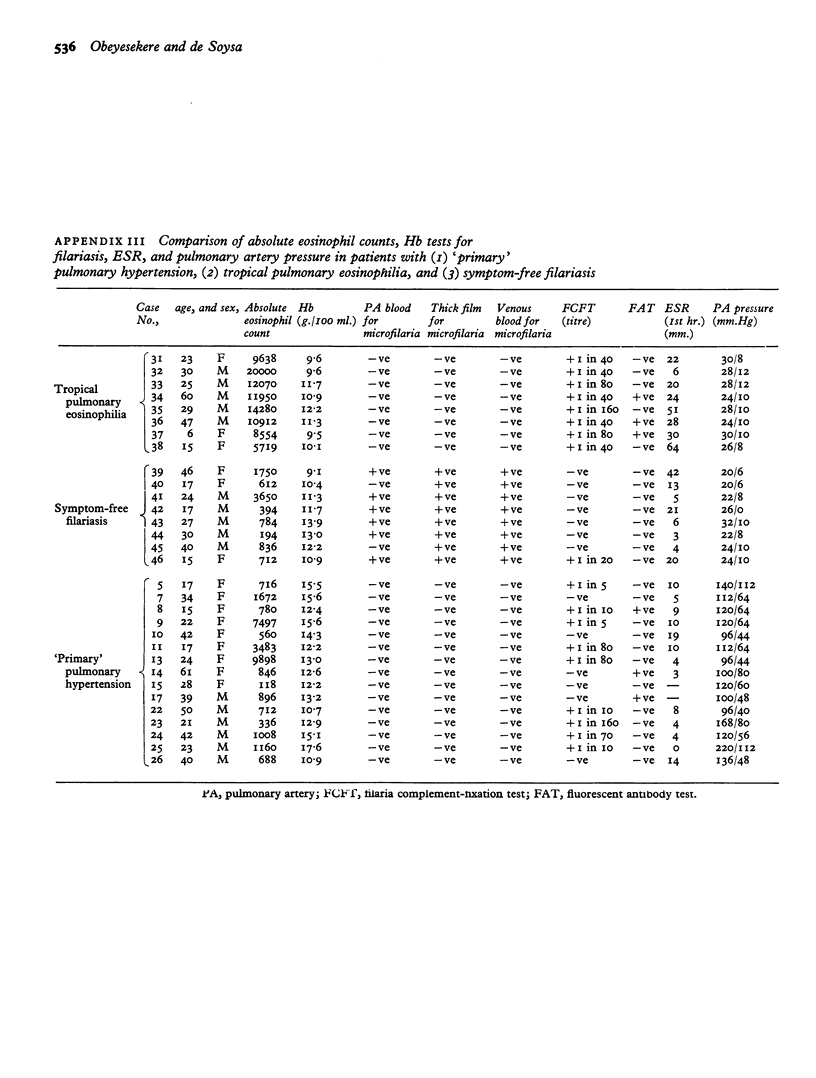

Many patients with `primary' pulmonary hypertension had an unusually high eosinophil count (normal range for Ceylon, 0–500 per cu.mm.). Patients in hospitals often have higher counts ranging from 0–1000 per cu.mm. due to intestinal parasitic infestation. Patients with `primary' pulmonary hypertension were found to have a significantly higher mean eosinophil count than age-matched, sex-matched controls admitted to the Cardiology Unit with chronic rheumatic heart disease and congenital heart disease. The higher count was not due to intestinal parasitic infestation, and none of the other known causes of a raised eosinophil count were present.

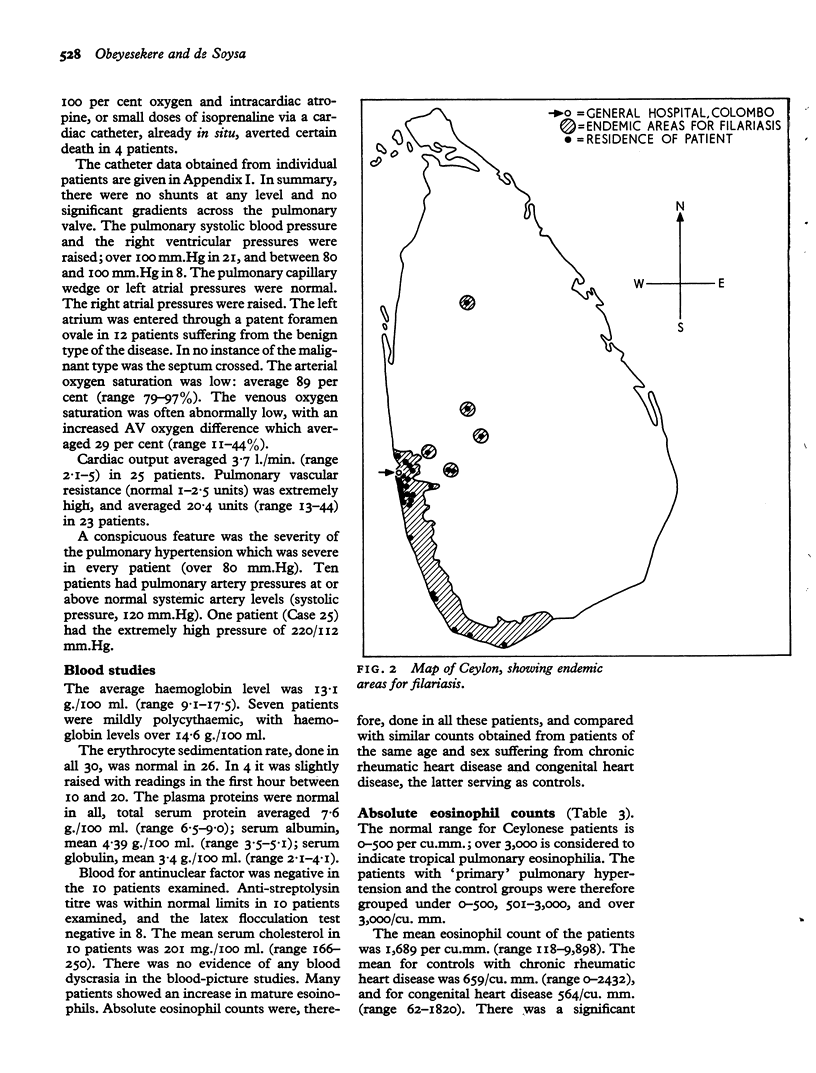

Four patients had eosinophil counts over 3,000 per cu.mm., the range commonly associated with tropical pulmonary eosinophilia, a disease caused by filariasis. These patients did not manifest any of the symptoms of tropical pulmonary eosinophilia. Patients with `primary' pulmonary hypertension were examined for evidence of filariasis (clinical, haematological, and serological). Volunteers from among patients with tropical pulmonary eosinophilia and symptom-free patients positive for Wuchereria bancrofti microfilaria were similarly tested and also catheterized for evidence of pulmonary hypertension. The results of these investigations and their significance are discussed. The geographical incidence of `primary' pulmonary hypertension and filariasis was similar.

Filarial worms are known to cause pulmonary hypertension in animals. There is sufficient evidence to suspect that the same may be true in humans. This may explain the high incidence of the disease in Ceylon and its unusually high prevalence among men.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- BRINTON W. D. Primary pulmonary hypertension. Br Heart J. 1950 Jul;12(3):305–311. doi: 10.1136/hrt.12.3.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CIVIN W. H., EDWARDS J. E. Pathology of the pulmonary vascular tree. I. A comparison of the intrapulmonary arteries in the Eisenmenger complex and in stenosis of ostium infundibuli associated with biventricular origin of the aorta. Circulation. 1950 Oct;2(4):545–552. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.2.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DETWEILER D. K., HUBBEN K., PATTERSON D. F. Survey of cardiovascular disease in dogs--preliminary report on the first 1,000 dogs screened. Am J Vet Res. 1960 May;21:329–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DISSANAIKE A. S., PARAMANANTHAN D. C. On Brugia (Brugiella subgen. nov.) buckelyi n.sp., from the heart and blood vessels of the Ceylon hare. J Helminthol. 1961;35:209–220. doi: 10.1017/s0022149x00004570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DRESDALE D. T., MICHTOM R. J., SCHULTZ M. Recent studies in primary pulmonary hypertension, including pharmacodynamic observations on pulmonary vascular resistance. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1954 Mar;30(3):195–207. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEATH D., EDWARDS J. E. Configuration of elastic tissue of pulmonary trunk in idiopathic pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 1960 Jan;21:59–62. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.21.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLLISTER R. M., GOODWIN J. F. The electrocardiogram in cardiomyopathy. Br Heart J. 1963 May;25:357–374. doi: 10.1136/hrt.25.3.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JAYASINGHE J. B., FERNANDO S. D., DISSANAIKE A. S. ELECTROCARDIOGRAPHIC EVIDENCE OF CARDIAC HYPERTROPHY IN A HARE INFECTED WITH THE FILARIAL WORM BRUGIA (BRUGIELLA) BUCKLEYI. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1964 Sep;58:328–332. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1964.11686250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayewardene L. G., Wijayaratnam Y. The fluorescent antibody test in the serological diagnosis of the causative organisms of tropical eosinophilia and filariasis. J Helminthol. 1968;42(1):57–64. doi: 10.1017/s0022149x00027231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAWSON A. J., WOSKE H. M. A study of etiologic factors in so-called primary pulmonary hypertension. Arch Intern Med. 1960 Feb;105:233–243. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1960.00270140055006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEBB J. K., JOB C. K., GAULT E. W. Tropical eosinophilia: demonstration of microfilariae in lung, liver, and lymphnodes. Lancet. 1960 Apr 16;1(7129):835–842. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(60)90730-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILCKEN D. E., MACKENZIE K. M., GOODWIN J. F. Anticoagulant treatment of obliterative pulmonary hypertension. Lancet. 1960 Oct 8;2(7154):781–783. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(60)91854-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]