Abstract

Conditional adjustment of cooperativeness to the expected pay-off might be a useful strategy to avoid being exploited in public good situations. Parental care provided towards all offspring in a communal nest (containing offspring of several females) resembles a public good. Females indiscriminately caring for all young share the costs equally, but the pay-off may vary depending on their contribution to the joint nest (number of own offspring). Females with fewer offspring in the joint nest will be exploited and overinvest relative to their contribution. We experimentally created a situation of high conflict in communally nursing house mice, by using a genetic tool to create a difference in birth litter sizes. Females in the high conflict situation (unequal litter sizes at birth) showed a reduced propensity to give birth as part of a communal nest, therefore adjusting their cooperativeness to the circumstances.

Keywords: house mouse, public good, cooperation, communal nursing, infanticide, litter size

1. Introduction

The use of public resources leads to conflict, known as the collective action problem [1] or the public goods dilemma (tragedy of the commons) [2]. Individuals have an incentive to increase their own benefit by cheating at the expense of the other group members. Many examples of cooperation in animals can be classified as such social dilemmas and raise the question of how cooperation is stabilized [3]. Both theoretical and empirical research revealed that kin selection or coercion (punishment) can prevent the collapse of the cooperation in a public goods dilemma [4–8]. However, the importance of punishment in animal systems is debated [9].

The classical public good is defined as non-excludable, meaning that individuals cannot be excluded from the benefits. However, situations exist in which individuals have the option to be neutral bystanders and not join a cooperation. Under such conditional cooperation, individuals decide based on the context whether to participate in the cooperation or not. This opens the possibilities for other mechanisms to stabilize cooperation. In a theoretical model, Hauert et al. [10] showed for example that the evolution of costly punishment is facilitated under such conditional cooperation.

Cooperative offspring care is a situation that resembles a public good and may be conditional. Communal breeding or joint nesting can be observed in many different taxa (social spiders [11], insects [12], birds [13] and mammals [14]). In communally caring species, several females pool their clutches or litters in one nest or help raise the offspring of others, with varying degrees of reproductive skew among females. The public good is the parental care provided by the females (and potentially also by males or non-reproducing helpers) towards all young. In species where several reproducing females indiscriminately care for offspring in a joint nest, females share costs equally, but the benefits for the individuals can vary depending on the number of offspring they have in the nest and the amount of care they provide. Indiscriminate care of young has been described for a number of communally breeding species such as beetles [15], birds [16], bats [17] and rodents [18]. Communal offspring care may also be conditional, because individuals can choose to participate in the public good (by forming a communal nest) [19–21] or nest solitarily instead.

This is the case for house mice (Mus musculus domesticus), a species in which females show two different breeding strategies, rearing their young either solitarily, or communally together with one or several other females (Auclair et al. [22] observed on average 2.2 ± 0.1 (mean ± s.e.) females per communal nest). A recent field study revealed that females did not always communally nurse when given the opportunity (when at least one other female in the social group had dependent offspring at the time the focal female gave birth). Only 33% of those females formed communal nests; the other 67% raised their young solitarily instead [23]. Such a low percentage seems surprising, considering that in a laboratory setting, females nursing their young communally together with a sister were found to have an increased lifetime reproductive success in comparison with solitary nursing females [24]. Further benefits described for communal nursing in mice are an increased pup survival [25,26] and a reduction in the time females allocate to spending with their young, without increasing the total amount of time pups were alone [22]. The relative low frequency of communal nursing indicates that females might not always benefit from cooperation. Analysing the potential for conflict among females and under what conditions they decide against cooperation could help to understand the mechanisms stabilizing it.

Females rearing litters communally do not discriminate between their own and alien offspring [27] and produce milk according to the total number of pups in the joint nest and not their own litter size [28], which provides scope for exploitation. As soon as females differ in litter size, the one with the larger litter will exploit the other. Litter size differences arise if females give birth to differently sized litters, or if litters differ in their survival probability after birth. We would expect the conflict potential to be the smallest and females most likely to cooperate when they benefit equally, in other words, if they have similar litter sizes, and to be less cooperative when litters differ in size.

One way to minimize exploitation and as a consequence the collapse of the public good is to decide against communal nursing in an enhanced conflict situation, when litters differ in size. This would require females to have information on not only their own, but also the litter size of their potential social partner, enabling them to adjust their propensity to cooperate to the circumstances. According to this hypothesis, females with the smaller litter size will not form communal nests and therefore avoid the public good situation if there is a pronounced asymmetry in the expected pay-off.

Alternatively, females may reduce the conflict by adjusting their partner's litter size through infanticide. Infanticide towards pups that are not their own has been described for female house mice and other mammals and birds, with females giving birth (or laying eggs) first being more susceptible to infanticide [24,29,30]. Considering that females are unable to discriminate between own and alien offspring, they should only be infanticidal while still pregnant. In addition, we expect female infanticide to be constrained by the partner's interest. If a female kills too many pups, then the partner might leave the empty nest or small litter, before the second female gives birth, because the costs of abandoning the litter may be smaller than staying and raising almost exclusively another female's litter. Under this hypothesis, we predict female-induced infanticide to correlate with the difference in litter size, with the second female killing more pups if her partner has a larger litter than herself. To test the two hypotheses, we experimentally created asymmetries in litter sizes of two familiar full sisters within a social group to analyse their behaviour and their propensity to engage in communal nursing. We used a genetic tool to prenatally manipulate litter sizes, which allowed us to: (i) measure a female's propensity to cooperate under an enhanced conflict situation, and (ii) test whether female infanticide serves as a tool to minimize conflict by equalizing litter sizes.

2. Material and methods

(a). Animals and husbandry

Laboratory-born F1–F3 descendants from a wild house mouse population near Illnau, Switzerland were used as study subjects. For a description of the wild population of origin, see König and Lindholm [31]. The experiments were conducted in Zurich between April 2011 and December 2012. Mice were kept under a constant light : dark cycle of 14 : 10 h (light on at 05.30 h CET) and at a temperature of 22–24°C. Food (laboratory animal diet for mice and rats, no 3430, Kliba) and water were provided ad libitum, along with paper towels and cardboard that served as nest building material.

(b). Experimental design

Females were on average 93 days old (range: 62–209 days) and sexually naive at the beginning of the experiment. Two full sisters (litter mates) were kept together with an unrelated male in a cage system, consisting of three Macrolon type II cages (18 × 24 × 14 cm), connected via transparent plastic tubes. Such a set-up was used in previous studies and may allow females to defend a cage each [32]. A pair of females living together with a male in a cage system from here onwards will be referred to as a social group.

To manipulate litter size and create an asymmetry between females in our experimental groups, we used the t haplotype, a selfish genetic element carrying a lethal allele, present in our wild population of origin (see the electronic supplementary material or [33]). Within each group, one of the two sisters was +/+, whereas the other was +/t. Using +/t and +/+, females in both the experimental and control treatment allowed us to control for potential effects of the t on female behaviour. In the experimental treatment (n = 14 pairs, 28 females) females were kept together with a previously unfamiliar, genetically unrelated +/t male. The +/t female was therefore expected to have a smaller litter than her +/+ sister, owing to in utero mortality of t/t homozygous embryos [34]. In the control treatment (n = 11 pairs, 22 females) the male was +/+, and as a consequence no substantial differences in litter size between females was expected. Males remained with the females for the whole duration of the experiment. The experiment was stopped as soon as females had raised two communal nests, or if the females did not raise two communal nests within 100 days.

Forty out of 50 females were milked while raising their last litter as part of a different experiment [28]. Milking was shown to have no effect on offspring survival probability, and those litters were therefore included in analyses here.

(c). Monitoring reproduction

From day 19 after introduction of the male, we checked social groups daily in the morning for newborn pups and documented the total number of pups. We did not handle the pregnant females to avoid the risk of stress-induced abortions. Tissue samples were taken from pups found dead, as well as from pups alive at weaning to assess their maternity if they could not be assigned to one of the two litters (see the electronic supplementary material for more information about the genotyping and parentage analysis). Litters were removed from the group when 28 days old.

Mouse pups start to forage independently when they are 17 days old and are fully weaned with 23 days. Following König [24], we defined a communal nest as two litters being born within 17 days of each other and being raised in one nest. When litters were more than 17 days apart in age, we did not consider this as a communal nest, because the older litter was no longer fully dependent on milk and had only a small influence on female investment.

(d). Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with R v. 3.0.2 [35]. Generalized linear models (GLMs) were conducted, unless the nested design of the study (two sisters within a social group, several litters per female) required additional random effects to control for dependencies within the data. In these situations, linear (LMM) and generalized linear-mixed models (GLMMs) were performed with the package lme4 [36]. Fulfilment of model assumptions was inspected visually, and the data were transformed if necessary or the appropriate link function was chosen. GLMs and GLMMs with a binomial error distribution were tested for overdispersion.

During model selection, the full model was used as starting model and then compared against all lower-level models. Models were ranked based on their Akaike information criterion corrected for small sample size (AICc) value and the one with the lowest value chosen as best model. If two or more models were within 2 delta AICc of each other, then the one with the lower number of degrees of freedom was used. Table 1 summarizes all analyses, giving the type of model used, the full model and the most adequate model after model selection. To assess the significance of fixed effects parametric bootstrapping was used (see the electronic supplementary material for more details).

Table 1.

Summary of statistical models used for data analyses. Full models and most adequate models after model selection are given. (Abbreviations: ♂ or ♀ genotype, male or female genotype (+/t or +/+); trt, treatment (control or experiment); proportion succ. communal nests, proportion of successful communal nests (at least one pup from each litter survived to weaning) in relation to all communal nests (successful and unsuccessful ones); proportion of communal nests, proportion of communal nests in relation to all reproductive events (communal nests and solitary nests); ord, birth order within the nest (first- or second-born litter); agediff, age difference between the litters  ; ls diff, difference in litter size between the females; cnID, communal nest identity; ♀ID, female identity; litterID, litter identity; wstart, female body weight at the beginning of the experiment; wbirth, female bodyweight after having given birth.)

; ls diff, difference in litter size between the females; cnID, communal nest identity; ♀ID, female identity; litterID, litter identity; wstart, female body weight at the beginning of the experiment; wbirth, female bodyweight after having given birth.)

| type of model | response variable | fixed effects: full model | most adequate model | random effects: |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| effect of the t haplotype on litter size | ||||

| LMM | litter size at birth | ♂genotype×♀genotype | ♂genotype×♀genotype | social group/♀ID |

| LMM | litter size at weaning | ♂genotype×♀genotype | ♂genotype×♀genotype | social group/♀ID |

| propensity to engage in communal nursing | ||||

| GLM (quasi-binomial) | proportion succ. communal nests | trt | only the intercept | — |

| GLM (quasi-binomial) | proportion of communal nests | trt | trt | — |

| infanticide | ||||

| GLMM (binomial) | proportion of pups alive (weaning) | trt×♀genotype×ord+agediff | ord | cnIDc/♀ID |

| GLMM (poisson) | no. of pups killeda | ls diff + litter size at birth | —b | social group/♀ID |

| GLMM (binary) | birthing order (1 or 2) | trt*genotype + wstart + wbirth + ls diff | only the intercept | cnIDc/♀ID |

aOnly first-born litters were used for this analysis.

bNo AICc can be calculated for a GLM with a Poisson error distribution and all factors were retained in the model for further analyses.

cIn those two analysis the cnID was used as random factor instead of the social group, because the two litters within a communal nest were directly compared to each other specifically.

3. Results

(a). Effect of the t haplotype on litter size

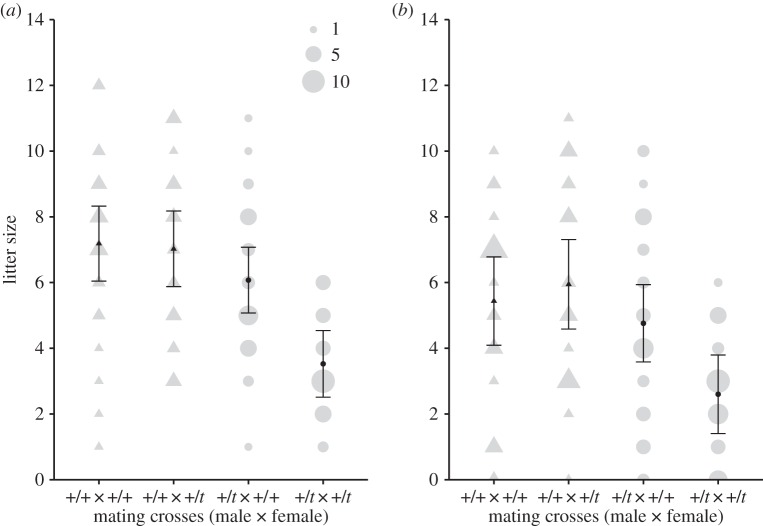

Pairing +/t males with +/t females resulted in litter size reduction at birth in the experimental treatment (mean [95% confidence interval (CI)] of the difference in the number of pups between +/t and +/+ females, 2.5 [1.6–3.5]) compared with the control (0.2 [−1.0–1.3]), owing to the recessive lethal nature of the t haplotype (LMM: parametric bootstrapping, male genotype/female genotype interaction: χ2 = 8.82, p = 0.004; figure 1a). Our treatment hence succeeded in creating a situation of enhanced conflict among females based on different birth litter sizes.

Figure 1.

Litter size for all mating crosses (male genotype × female genotype) between +/t and +/+ mice at (a) birth and at (b) weaning. Triangles represent mating crosses from the control and circles from the experimental treatment. Model estimates and the 95% CI of the mean are displayed (LMM). Raw data are plotted in grey and the point/triangle size indicates the sample size for a certain litter size (n = 104 litters, excluding eight litters from four communal nests that were born on the same day and whose litter size at birth was unknown).

+/+ females gave birth to (mean [95% CI]) 7.2 [6.0–8.3] pups per litter in the control treatment (paired with a +/+ male) and 6.1 [5.1–7.1] pups in the experimental treatment (paired with a +/t male). +/t females had on average 7.0 [5.9–8.2] pups in the control treatment and 3.5 [2.5–4.5] in the experimental treatment (figure 1). Litter size differences at weaning between +/+ and +/t females were not significant, but tended to be larger in the experimental than the control treatment (LMM: parametric bootstrapping: male genotype/female genotype interaction: χ2 = 4.27, p = 0.060; figure 1b).

(b). Propensity to cooperate

A total of 112 litters were born in 25 social groups (14 groups in the experimental treatment and 11 groups in the control treatment). Ninety-four of the litters were raised in 47 communal nests. The remaining 18 litters were solitarily reared, meaning that no other litter was born within 17 days before or after its birth (10 of the solitary litters were raised by +/+ females and 8 by +/t females). The two litters in communal nests were on average 3.1 ± 0.6 days in age apart in the control and 3.4 ± 0.7 days in age apart in the experimental treatment (mean ± s.e.; in 7/47 communal nests, the two litters were born on the same day). At least one pup from 100 litters survived until weaning (day 23); 12 litters were lost entirely (four solitary litters and eight litters from communal nests).

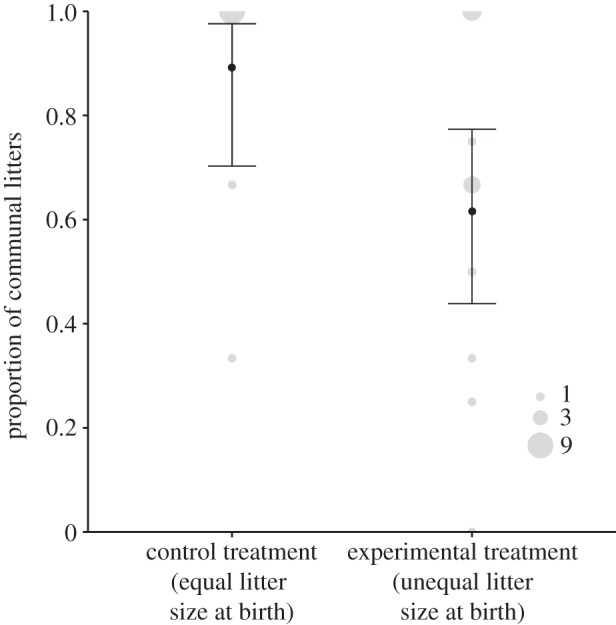

We define a communal nest as successfully reared if at least one pup from each litter survived until weaning. Female pairs did not differ significantly between control and experimental treatment in their probability of successfully raising a communal nest (GLM:  , p = 0.727). However, the number of communal nests (successful and unsuccessful ones) in relation to the total number of reproductive events (communal nests plus solitary litters) was significantly higher in the control than in the experimental treatment (GLM:

, p = 0.727). However, the number of communal nests (successful and unsuccessful ones) in relation to the total number of reproductive events (communal nests plus solitary litters) was significantly higher in the control than in the experimental treatment (GLM:  , p = 0.028). Females in the experimental treatment (unequal litter size at birth) showed a reduced propensity to give birth within 17 days from each other, i.e. to form communal nests (figure 2).

, p = 0.028). Females in the experimental treatment (unequal litter size at birth) showed a reduced propensity to give birth within 17 days from each other, i.e. to form communal nests (figure 2).

Figure 2.

The proportion of communal nests (two litters born within 17 days of each other) in relation to all litters (reared communally and solitarily) raised by females in the control (similar litter size at birth) and experimental (unequal litter size at birth) treatment. Displayed are backtransformed model means and the 95% CI. Raw data are plotted in grey and the point size reflects the frequency (n = 25 social groups).

(c). Infanticide

From the 137 pups that did not reach weaning age, 131 disappeared or were found dead within their first five days. Pups found dead had wounds typically caused by adult conspecifics (bites on their head, bites in the neck region or missing body parts), as described in other studies reporting infanticide in house mice [26,37,38].

Pup survival did not differ between the control and the experimental treatment (the factor treatment was not retained during model selection). Moreover, larger litters in the experimental treatment (litters of +/+ females) did not have a lower survival probability and this was true whether they were the first- or second-born litter in a communal nest (the two-way interaction genotype : treatment and the three-way interaction genotype : treatment : order were not retained during model selection, table 1).

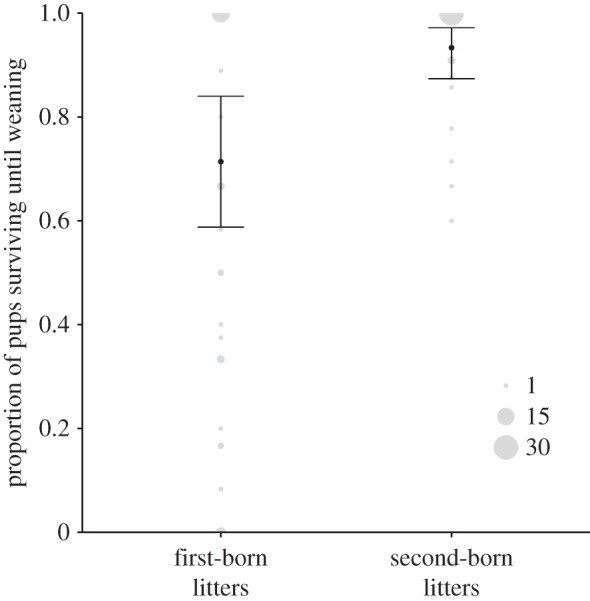

The birth order in a communal nest, however, had a significant effect on the proportion of pups that reached weaning age (parametric bootstrapping, χ2 = 19.29, p < 0.010; figure 3). First-born litters suffered more often from a partial litter loss, and only first-born litters were lost completely. In two cases, litters were born on the same day and we were not able to determine whether the pups found dead were from the first- or second-born litter. Of the 79 pups that died from first-born litters, 65 were found dead before the second litter was born.

Figure 3.

The proportion of pups alive at weaning for first- and second-born litters within communal nests. Plotted are back transformed model estimates (mean) and 95% CI of the mean. Raw data are plotted in grey and the point size indicates the frequency (n = 80 litters from 44 different females in 40 different communal nests, excluding seven communal nests with pups born on the same day and consequently no information available on the birthing order).

If females used infanticide to equalize litter sizes, then we would expect the number of killed pups in the first litter to correlate with the actual difference in litter size. Significantly more pups died before weaning in larger litters (GLMM: slope 0.27 (0.082–0.502)), but the actual differences in litter size at birth between females had no significant effect on the number of pups killed (factor was not retained during model selection).

We were unable to predict birth order among pairs of females. Neither female body weight (at the start of the experiment or after they had given birth), a female's genotype, the male's genotype (treatment) or the difference in litter size (focal litter—other litter) had an influence on a female's probability to give birth first or second. None of the included factors improved the model significantly, and only the intercept was retained during model selection (n = 68 birth events as part of 36 different communal nests by 42 different females).

4. Discussion

Female house mice conditionally adjusted their propensity to cooperate to the potential for conflict. In a situation in which high conflict between females was expected owing to pronounced differences in litter size, females raised a higher number of litters solitarily and did not cooperate. Contrary to our predictions, females did not raise two solitary litters concurrently, but instead they avoided communal litters by not giving birth within 17 days of each other, the duration of full pup dependence. Our experiment further revealed competition over reproduction among cooperatively nursing full sisters in the form of infanticide. Female infanticide, however, did not equalize litter sizes within groups, and thus did not eliminate the conflict among the two females. The number of pups found dead shortly after birth was independent of the differences in litter size of the partners involved. Females that gave birth first in a communal nest suffered from elevated pup mortality, most probably caused by infanticide committed by the still pregnant partner.

(a). Propensity to cooperate

In the experimental treatment, under the enhanced conflict, more litters were born and raised solitarily. This was not because females avoided communal nests by giving birth in different areas of the cage system, but because only one of the females produced a litter. Such a situation arises if one female does not mate, fails to conceive or aborts her litter during pregnancy. Mating failure can either be caused by unwillingness to mate on the female's side, or it could be a consequence of the male (males were together with the females for the whole duration of the experiment). We cannot exclude that the male's genotype in the experimental treatment interfered with the females' behaviour. Females carrying the selfish genetic element (+/t) suffer from a reduction in litter size when they mate with +/t males and may therefore avoid such costly matings [34]. There is evidence from other populations that +/t females are able to recognize the presence of the t haplotype and prefer +/+ males based on odour alone [39]. However, Lindholm et al. [34] found, using mice from the same population as used here, that neither +/t nor +/+ females showed a reduced propensity to give birth when mated monogamously with a +/t male. Furthermore, Sutter et al. [40] showed that in a polyandrous situation, females presented with a +/t and +/+ male readily mated with both, making it unlikely that females avoided the +/t male in our experiment.

Alternatively, increased competition among females influenced the rate of successful pregnancies and consequently led to the higher number of solitary litters as observed in the experimental treatment. This would require that females were able to not only estimate their own, but their social partner's litter size prenatally and that this subsequently influenced a female's likelihood to continue the pregnancy. Avoiding communal nursing when females differ in litter size could prevent the collapse of the public good insofar as it prevents exploitation during cooperation.

Female competition could lead to only one female giving birth in two ways. First, females may abstain from reproduction if it is too costly under the given circumstances by either not implanting their embryos or through an early abortion. Second, it might be that females suppress their partner's reproduction for example by using aggression to instigate stress-induced abortions (see review [41]). We never observed two concurrent solitary litters raised in separate nests. A study using the same cage system found a high occurrence of communal nursing, but similarly never solitary litters if another female was also breeding (there were never two nests at the same time) [32]. Similar to the results here, Weidt et al. [32] observed a number of cases where only one female of a pair gave birth, despite both having constant access to a male. We therefore assume that in our laboratory setting females did not have the option to simultaneously raise two litters solitarily within the space available; they either had the option to pool litters in a communal nest or abstain from reproduction. Withholding reproduction thus might have been the only way to avoid communal nursing.

Not to reproduce, on the other hand, might be associated with even higher costs than being the dam of the smaller litter in a communal nest. This could explain why communal nests still occurred in the high conflict treatment. Under natural conditions, females might instead of abstaining from reproduction choose to raise their litters solitarily in a separate nest, as has been described in a recent study where females were shown to raise their litters solitarily even if they had the option for communal nursing [23]. Additionally, females might be presented with not only one potential partner for cooperation, but instead have the ability to choose among several females. Indeed, there is evidence that social partner choice plays a role in a wild population of house mice. With an increasing number of available partners for cooperation, the proportion of females rearing their litters communally increased, independent of population density [23].

An alternative explanation for communal nursing in a high conflict situation could be that we used full sisters in our experiment. Mathot et al. [42] showed theoretically and empirically that individuals are more likely to tolerate exploitation through relatives, owing to the smaller costs of exploitation (indirect fitness benefits). If females giving birth first can prevent females from joining them, then we would expect higher levels of cooperation among sisters even with varying litter sizes, because females should be more likely to tolerate being joined by a related versus an unrelated partner. Wilkinson & Baker [43] observed that communal nursing preferentially occurs among genetically similar females in a wild population.

(b). Infanticide as a competitive reproductive strategy

The two litters within a communal nest had different survival rates, with higher survival in the second-born litters, resulting in females weaning unequal numbers of pups, not only in our experimental treatment with elevated potential for conflict, but also in the control treatment. However, we did not find that survival was influenced by litter size differences, or our experimental treatment. As a consequence, litter sizes were not equalized after the infanticide occurred; on the contrary, the differences in survival probability often created the asymmetries in the number of pups weaned.

Pups from the older litter (first-born in a communal nest) had a lower survival probability than their younger nest-mates. Younger pups (second-born) had a significantly higher survival probability and no entire litter was lost when older pups were already present (figure 3). Such an effect of the sequence of birth in a joint nest on the pups' survival probability has been seen in other studies investigating related and unrelated communally nursing female pairs [24,44].

Both male and female house mice commit infanticide [45], but female infanticide is more likely in this scenario. Males were shown not be infanticidal towards a female's pups if they previously mated and cohabited with that female [46]. By contrast, pregnant female house mice commit infanticide when confronted with pups shortly before giving birth themselves [47]. This could explain why almost no infanticide occurred after both females have given birth. It is also consistent with an inability to discriminate their own from alien offspring as seen in a cross-fostering experiment under restricted feeding, where females did not selectively kill alien young when they needed to sacrifice some pups in order to be able to raise their litters [27]. Based on these findings and in agreement with our results, killing offspring is only expected to occur before a female gives birth to her litter to avoid killing own young. Killing some of the other female's offspring seems to be a widespread strategy in mammals and birds to competitively bias reproductive success to one's own benefit [29,30,48,49].

(c). Females benefit unequally

Communal nests were mostly formed sequentially (less than 15% of communal nests were composed of litters born on the same day); one female gave birth first and as a consequence risked losing part of her litter before the other female joined. No relationship between the relative litter size and the probability to give birth first was found. Dominance among the females might determine the order in which they contribute to a communal nest and consequently which of the females is going to benefit more. Laboratory studies, however, did not reveal any signs for behavioural dominance among pairs of cooperating full sisters [24]. As soon as the litters in a communal nest are mixed, females invest according to the total number of pups in the joint nest [28] and have only limited options to prevent exploitation by the social partner. Aggression of highly pregnant females towards their partner's pups thus seems to be the most important mechanism to prevent exploitation and to gain reproductive benefits. However, only the female giving birth second in a communal nest can follow such a strategy. A study over a longer time period would help to determine whether communally nursing females will alternate in birth order and thus gain balanced lifetime reproductive success. Considering that house mice have a rather short life expectancy (average of 196 days, [50]) and might not necessarily cooperate again with the same social partner, the probability for reproductive skew will be high. In contrast to communally breeding birds that continue laying eggs if all of theirs had been destroyed [30,51], mammals cannot add more own young to the nest. Communally nursing females therefore do not equally benefit from their cooperation, and some may even have a disadvantage compared with solitarily nursing females.

Females might be unable to prevent another female from joining the nest. Consequently, they may find themselves in a ‘best of a bad job’ situation as soon as another female joins the nest. Because they are unable to discriminate their own from alien offspring, they either have to stay and invest into the combined litter or they have to abandon their pups, which very likely would result in even higher pup mortality. Given the rather short life expectancy of house mice, the better option might be to stay and raise the communal nest, because the costs of staying may still outweigh the costs of abandoning a litter. Communal nesting and communal nursing may additionally provide other benefits for a female, as in better protection of pups against infanticide by non-group members [25,26] or improved weaning weight of pups [28].

Our findings support the hypothesis that females avoid exploitation by conditionally adjusting their propensity to cooperate to the conflict potential in a public good situation. Furthermore, female infanticide revealed pronounced reproductive competition even among full sisters.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We thank Jari Garbely for the genetic analysis and Gabriele Stichel for the animal care. Andri Manser and Barbara Tschirren kindly commented on a previous version of the manuscript. We further thank Andreas Sutter for statistical advice and discussions.

Ethics

All experiments have been approved by the Veterinary Office Zurich, Switzerland (licence no. 65/2011).

Data accessibility

Supporting data have been included in the electronic supplementary material.

Authors' contributions

A.K.L., B.K. and M.F. contributed to the design of the study and wrote the manuscript. M.F. performed the experiment. All authors approved the text for publication.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Funding

This study was funded by the University of Zurich.

References

- 1.Olson M. 1965. The logic of collective action: public goods and the theory of group. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hardin G. 1968. The tragedy of the commons. Science 162, 1243–1248. ( 10.2307/1724745) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rankin DJ, Bargum K, Kokko H. 2007. The tragedy of the commons in evolutionary biology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 22, 643–651. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2007.07.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Dijk RE, Kaden JC, Argüelles-Ticó A, Dawson DA, Burke T, Hatchwell BJ. 2014. Cooperative investment in public goods is kin directed in communal nests of social birds. Ecol. Lett. 17, 1141–1148. ( 10.1111/ele.12320) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peters HE, Ünür AS, Clark J, Schulze WD. 2004. Free-riding and the provision of public goods in the family: a laboratory experiment. Int. Econ. Rev. 45, 283–299. ( 10.1111/j.1468-2354.2004.00126.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kümmerli R, Gardner A, West SA, Griffin AS. 2009. Limited dispersal, budding dispersal, and cooperation: an experimental study. Evolution 63, 939–949. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00548.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wenseleers T, Helanterä H, Hart A, Ratnieks FLW. 2004. Worker reproduction and policing in insect societies: an ESS analysis. J. Evol. Biol. 17, 1035–1047. ( 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2004.00751.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fehr E, Gächter S. 2000. Cooperation and punishment in public goods experiments. Am. Econ. Rev. 90, 980–994. ( 10.2307/117319) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raihani NJ, Thornton A, Bshary R. 2012. Punishment and cooperation in nature. Trends Ecol. Evol. 27, 288–295. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2011.12.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hauert C, Traulsen A, Brandt H, Nowak MA, Sigmund K. 2007. Via freedom to coercion: the emergence of costly punishment. Science 316, 1905–1907. ( 10.1126/science.1141588) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schneider JM. 2002. Reproductive state and care giving in Stegodyphus (araneae: Eresidae) and the implications for the evolution of sociality. Anim. Behav. 63, 649–658. ( 10.1006/anbe.2001.1961) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heg D, Heyl S, Rasa OAE, Peschke K. 2006. Reproductive skew and communal breeding in the subsocial beetle Parastizopus armaticeps. Anim. Behav. 71, 427–437. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2005.06.001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mumme RL, Koenig WD, Pitelka FA. 1988. Costs and benefits of joint nesting in the acorn woodpecker. Am. Nat. 131, 654–677. ( 10.2307/2461671) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.König B. 1997. Cooperative care of young in mammals. Naturwissenschaften 84, 95–104. ( 10.1007/s001140050356) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eggert A-K, Müller JK. 1992. Joint breeding in female burying beetles. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 31, 237–242. ( 10.2307/4600746) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riehl C, Strong M. 2015. Social living without kin discrimination: experimental evidence from a communally breeding bird. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 69, 1293–1299. ( 10.1007/s00265-015-1942-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Watkins LC, Shump J, Karl A. 1981. Behavior of the evening bat Nycticeius humeralis at a nursery roost. Am. Midl. Nat. 105, 258–268. ( 10.2307/2424744) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holmes WG, Sherman PW. 1982. The ontogeny of kin recognition in two species of ground squirrels. Am. Zool. 22, 491–517. ( 10.1093/icb/22.3.491) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McShea WJ, Madison DM. 1984. Communal nesting between reproductively active females in a spring population of Microtus pennsylvanicus. Can. J. Zool. 62, 344–346. ( 10.1139/z84-053) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scott MP, Williams SM. 1993. Comparative reproductive success of communally breeding burying beetles as assessed by PCR with randomly amplified polymorphic DNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 90, 2242–2245. ( 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2242) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lott DF, Mastrup SNA. 1999. Facultative communal brood rearing in California quail. The Condor 101, 678–681. ( 10.2307/1370200) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Auclair Y, König B, Ferrari M, Perony N, Lindholm AK. 2014. Nest attendance of lactating females in a wild house mouse population: benefits associated with communal nesting. Anim. Behav. 92, 143–149. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2014.03.008) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weidt A, Lindholm AK, König B. 2014. Communal nursing in wild house mice is not a by-product of group living: females choose. Naturwissenschaften 101, 73–76. ( 10.1007/s00114-013-1130-6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.König B. 1994. Components of lifetime reproductive success in communally and solitarily nursing house mice: a laboratory study. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 34, 275–283. ( 10.1007/BF00183478) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manning CJ, Dewsbury DA, Wakeland EK, Potts WK. 1995. Communal nesting and communal nursing in house mice, Mus musculus domesticus. Anim. Behav. 50, 741–751. ( 10.1016/0003-3472(95)80134-0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Auclair Y, König B, Lindholm AK. 2014. Socially mediated polyandry: a new benefit of communal nesting in mammals. Behav. Ecol. 25, 1476–1473. ( 10.1093/beheco/aru143) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.König B. 1989. Kin recognition and maternal care under restricted feeding in house mice (Mus domesticus). Ethology 82, 328–343. ( 10.1111/j.1439-0310.1989.tb00513.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferrari M, Lindholm AK, König B. 2015. The risk of exploitation during communal nursing in house mice, Mus musculus domesticus. Anim. Behav. 110, 133–143. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2015.09.018) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andersson M, Eriksson MOG. 1982. Nest parasitism in goldeneyes Bucephala clangula: some evolutionary aspects. Am. Nat. 120, 1–16. ( 10.1086/283965) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koenig WD, Mumme RL, Stanback MT, Pitelka FA. 1995. Patterns and consequences of egg destruction among joint-nesting acorn woodpeckers. Anim. Behav. 50, 607–621. ( 10.1016/0003-3472(95)80123-5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.König B, Lindholm A. 2012. The complex social environment of female house mice (Mus domesticus). In Evolution of the house mouse (eds Macholàn M, Baird SJE, Mundlinger P, Piàlek J), pp. 114–134. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weidt A, Hofmann SE, König B. 2007. Not only mate choice matters: fitness consequences of social partner choice in female house mice. Anim. Behav. 75, 801–808. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2007.06.017) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferrari M, Lindholm A, König B. 2014. A genetic tool to manipulate litter size. Front. Zool. 11, 18 ( 10.1186/1742-9994-11-18) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindholm AK, Musolf K, Weidt A, König B. 2013. Mate choice for genetic compatibility in the house mouse. Ecol. Evol. 3, 1231–1247. ( 10.1002/ece3.534) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.R Core Team 2013. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S. 2014. lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using Eigen and S4. R package v. 1.1-7. J. Stat. Softw.67, 1–48 ( 10.18637/jss.v067.i01) [DOI]

- 37.Huck WU, Soltis RL, Coopersmith CB. 1982. Infanticide in male laboratory mice: effects of social status, prior sexual experience, and basis for discrimination between related and unrelated young. Anim. Behav. 30, 1158–1165. ( 10.1016/S0003-3472(82)80206-6) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Labov JB, Huck UW, Elwood RW, Brooks RJ. 1985. Current problems in the study of infanticidal behavior of rodents. Q. Rev. Biol. 60, 1–20. ( 10.2307/2827598) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lenington S, Coopersmith C, Williams J. 1992. Genetic basis of mating preferences in wild house mice. Am. Zool. 32, 40–47. ( 10.1093/icb/32.1.40) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sutter A, Lindholm AK. 2015. Detrimental effects of an autosomal selfish genetic element on sperm competitiveness in house mice. Proc. R. Soc. B 282, 20150974 ( 10.1098/rspb.2015.0974) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wasser SK, Barash DP. 1983. Reproductive suppression among female mammals: implications for biomedicine and sexual selection theory. Q. Rev. Biol. 58, 513–538. ( 10.2307/2829326) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mathot KJ, Giraldeau L-A. 2010. Within-group relatedness can lead to higher levels of exploitation: a model and empirical test. Behav. Ecol. 21, 843–850. ( 10.1093/beheco/arq069) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilkinson GS, Baker AM. 1988. Communal nesting among genetically similar house mice. Ethology 77, 103–114. ( 10.1111/j.1439-0310.1988.tb00196.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palanza P, Della Seta D, Ferrari PF, Parmigiani S. 2005. Female competition in wild house mice depends upon timing of female/male settlement and kinship between females. Anim. Behav. 69, 1259–1271. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2004.09.014) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.vom Saal FS. 1984. Proximate and ultimate causes of infanticide and parental behaviourin male house mice. In Infanticide: comparative and evolutionary perspectives (eds Hausfater G, Hrdy S), pp. 401–424. New York, NY: Aldine Transaction. [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCarthy MM, Vom Saal FS. 1986. Inhibition of infanticide after mating by wild male house mice. Physiol. Behav. 36, 203–209. ( 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90004-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McCarthy MM, vom Saal FS. 1985. The influence of reproductive state on infanticide by wild female house mice (Mus musculus). Physiol. Behav. 35, 843–849. ( 10.1016/0031-9384(85)90248-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hansson B, Bensch S, Hasselquist D. 1997. Infanticide in great reed warblers: secondary females destroy eggs of primary females. Anim. Behav. 54, 297–304. ( 10.1006/anbe.1996.0484) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Young AJ, Clutton-Brock T. 2006. Infanticide by subordinates influences reproductive sharing in cooperatively breeding meerkats. Biol. Lett. 2, 385–387. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2006.0463) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Manser A, Lindholm AK, König B, Bagheri HC. 2011. Polyandry and the decrease of a selfish genetic element in a wild house mouse population. Evolution 65, 2435–2447. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01336.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Riehl C. 2011. Living with strangers: direct benefits favor non-kin cooperation in a communally breeding bird. Proc. R. Soc. B 278, 1728–1735. ( 10.1098/rspb.2010.1752) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Supporting data have been included in the electronic supplementary material.