Abstract

In late pregnancy, maternal insulin resistance occurs to support fetal growth but little is known about insulin-glucose dynamics close to delivery. This study measured insulin sensitivity in mice in late pregnancy, day (D) 16, and near term, D19, (term 20.5D). Non-pregnant (NP) and pregnant mice were assessed for metabolite and hormone concentrations, body composition by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry, tissue insulin signalling protein abundance by Western blotting, glucose tolerance and utilisation, and insulin sensitivity using acute insulin administration and hyperinsulinaemic-euglycaemic clamps with 3H-glucose infusion. Whole body insulin resistance occurred in D16 pregnant dams in association with basal hyperinsulinaemia, insulin-resistant endogenous glucose production and downregulation of several proteins in hepatic and skeletal muscle insulin signalling pathways relative to NP and D19 values. Insulin resistance was less pronounced at D19 with restoration of NP insulin concentrations, improved hepatic insulin sensitivity and increased abundance of hepatic insulin signalling proteins. At D16, insulin resistance at whole body, tissue and molecular levels will favour fetal glucose acquisition while improved D19 hepatic insulin sensitivity will conserve glucose for maternal use in anticipation of lactation. Tissue sensitivity to insulin, therefore, alters differentially with proximity to delivery in pregnant mice with implications for human and other species.

Keywords: Insulin sensitivity, Insulin resistance, Glucose metabolism, Pregnancy

INTRODUCTION

During pregnancy, maternal metabolism adapts to support offspring growth. In particular, there are changes in insulin sensitivity, which affects the availability and fate of nutrients in both mother and conceptus (1,2). The specific adaptations depend on the stage of pregnancy as metabolic demands increase with expansion of the gravid uterus (3,4). In humans and rats, early pregnancy is a period of lipid accumulation and unchanged or increased insulin sensitivity, whereas, later pregnancy is characterised by lipid mobilisation and insulin resistance, common features of overt Type 2 diabetes (1,2,5,6). Indeed, whole body resistance to the hypoglycaemic action of insulin has been reported during late pregnancy in a wide range of species including rabbits, dogs, sheep, horses as well as rats and humans (7-13). It is often accompanied by reduced maternal glucose utilisation, particularly in skeletal muscle, although there is less consensus about the actions of insulin on hepatic glucogenesis during pregnancy (10,12,14,15). Most studies of insulin sensitivity during late pregnancy have been carried out between 60-85% of gestation with few measurements closer to term when fetal nutrient demands are maximal yet maternal nutrient requirements may also be changing in preparation for the imminent onset of labour and lactation.

Total conceptus mass varies not only with increasing gestational age but also between species both in total and as a percentage of maternal mass (16). Fetal growth rate is high during late mouse pregnancy and results in the gravid uterus accounting for 30% of maternal mass at term (16). This is a higher percentage than found in monotocous species like humans and sheep (5-9%) or the values of 12-25% seen in other polytocous animals like dogs, pigs and rats (16). Despite this, little is known about insulin sensitivity in pregnant mice, even though they are used widely in genetic and developmental studies in which variations in maternal insulin sensitivity may affect the ensuing offspring phenotype (17,18). The molecular basis of insulin resistance during late pregnancy is also still poorly understood in many species. Tissue insulin receptor (IR) abundance appears to be unaffected by pregnancy, although there is evidence for defects in the early stages of insulin signal transduction downstream of the IR in skeletal muscle of both rats in late pregnancy and pregnant women insulin resistant due to obesity or gestational diabetes (19-23). Hence, the aims of this study were to measure glucose-insulin dynamics, whole body insulin sensitivity and tissue insulin signalling proteins in non-pregnant (NP) mice and in pregnant dams in late gestation and close to term. C57B1/6 mice was used in the study because this strain has been used extensively to investigate the genetic and environmental regulation of feto-placental development (17,24).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

C57Bl/6 females (n=123) were group housed at 21°C under 12hr dark:12hr light conditions with free access to water and food (RM3, Special Diet Services). Aged 8-12 weeks, females were time mated with C57Bl/6 males with the presence of a copulatory plug defined as day (D)1 of a D20.5 pregnancy. Pregnant (n=77) and remaining non-pregnant (NP, n=46) mice were weighed every five days while food intake was measured every three days. Mice were allocated to one of the following procedures: 1) tissue and blood collection (n=30), (2) dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA, n=29) scanning, (3) glucose tolerance tests (GTT, n=28) or insulin tolerance tests (ITT, n=20) or (4) a hyperinsulinaemic-euglycaemic clamp (HEC) together with D-3H-glucose and 2-deoxyglucose (2DG) administration (n=18). All experiments were carried under the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 after ethical review by the University of Cambridge.

Experimental procedures

Tissue and blood collection

Between 08.00-10.00 h in fed conditions, pregnant dams at D16 and D19 and age-matched NP females (n=10 mice per group) were weighed and anaesthetised (10 μl/g of fentanyl-fluanisone: midazolam in sterile water, 1:1:2, Jansen Animal Health, ip). A cardiac blood sample was taken before euthanasia by cervical dislocation. In NP mice, liver, heart, kidneys, skeletal muscle (biceps femoris) and retroperitoneal fat were dissected, weighed and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. In pregnant dams, the gravid uterus, hysterectomised carcass and individual fetuses and placentas were weighed before maternal tissue collection. Blood glucose concentrations were measured on a hand held glucometer (One Touch Ultra, LifeScan, UK). After centrifugation, the plasma was stored at −20°C to measure metabolite and hormone concentrations.

DEXA scanning

Whole body fat and lean mass content were determined by DEXA scanning (Lunar PIXImus densitometer; GE lunar Corp., Madison WI) in intact NP females (n=10) and hysterectomised pregnant mice killed by cervical dislocation between 08.00-10.00 h (D16 n=7, D19 n=10). Values were expressed as a proportion of total body weight in NP mice and of hysterectomised weight in pregnant dams.

Glucose tolerance test and insulin tolerance test

Conscious NP and pregnant mice received either a GTT (NP n=11, D16, n=9, D19 n-8) or ITT (n=6-8 mice per group) after fasting from 08.00 h for 6 h or 3.5 h, respectively. Blood samples (≤ 5μl) were taken from the tail vein immediately before intraperitoneal administration of either glucose (10% w/v, 1 g/kg body weight) or insulin (0.25 U/kg, human insulin, Actrapid, Novo Nordisk) and, thereafter, at 15 to 30 min intervals for 120 min to measure blood glucose concentrations as above. The mice were then killed by cervical dislocation.

Hyperinsulinaemic-euglycaemic clamp

The HEC was performed as described previously (25). Briefly, NP and pregnant mice fasted for 2.5 h (NP n=7, D16, n=5, D19 n=6) were anaesthetised with a mixture of ventranquil: dormicum: fentanyl (1:2:10 in 3 units of water, 10 μl/g body weight, ip, Janssen-Cilag, Tilburg, Netherlands) and maintained at 37°C using a servo-controlled thermopad (Harvard Instruments, UK). After catheterising a tail vein, D-3H-glucose was infused continuously (0.006MBq/min in PBS, 50μl/hr, iv, 370-740GBq/mmol Perkin Elmer, UK). After steady state was achieved at 60 min (basal state, ≈ 3.5 h fasted), two blood samples (≤ 50μl each) were taken 10 min apart from the tail. Insulin was then injected as a bolus (3.3 mU, iv, Actrapid, human insulin, Novo Nordisk) followed by infusion (0.09 mU/min) together with the D-3H-glucose. Blood glucose levels was monitored every 5 min for the first 20 min after insulin administration and then at 10 min intervals until the end of the protocol (≤ 5 μl per sample). When a decrease in blood glucose concentration was detected 5-10 min after beginning the insulin infusion, a variable rate glucose infusion (12.5% w/v PBS, Sigma, iv) was begun and adjusted every 5-10 min thereafter to maintain blood glucose concentrations at mean basal levels. At 50 min after insulin infusion, 2-deoxy-glucose (14C-2DG, specific activity: 9.25-13.0GBq/mmol, Perkin Elmer, UK) was injected intravenously. By 70 min of insulin administration, blood glucose levels were clamped at basal concentrations and a further three blood samples (≤ 50μl each) were collected from the tail at 10 min intervals. The mice were then killed by cervical dislocation and samples of biceps femoris and retroperitoneal fat were collected from all animals together with the fetus and placenta adjacent to the cervix in each horn (n=2 fetuses and placentas per litter) for analysis of tissue 14C-2DG content. The rates of glucose utilization and production in basal and hyperglycaemic states together with whole body and hepatic sensitivity to insulin were calculated as described previously (25,26).

Biochemical analyses

Hormone and metabolite concentrations

Plasma D-3H-glucose concentrations were measured by scintillation counting (Hidex 300SL, LabLogic Ltd, Sheffield, UK), after samples were deproteinised with 20% trichloric acid and dried to eliminate tritiated water. Plasma leptin and insulin concentrations in the fed state were measured simultaneously using a 2-plex specific immunoassay (Meso Scale Discovery). The inter-assay coefficients of variation (CV) were 10.8% and 9.7%, respectively. Plasma insulin concentrations during the HEC were measured by ELISA (Crystal Chem Inc., 90090), which detected both murine and human insulin. The inter-assay CV was ≤ 10%. Plasma IGF1 levels were also measured by ELISA (ImmunoDiagnostic Systems) with an inter-assay CV of 4.6%. Enzymatic assay kits were used to determine the plasma concentrations of triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol (Siemens Healthcare, CV 5.5% and 4.9% respectively) and free fatty acids (Roche, CV 4.5%).

Tissue biochemical composition

Hepatic glycogen content was measured enzymatically, using amyloglucosidase as reported previously (27). The total fat content of the liver and pooled samples of skeletal muscle were measured using the modified Folch method (28). To determine tissue phosphorylated 2DG (p2DG) content, tissues were homogenised in 0.5% perochloric acid and the homogenates neutralised to separate p2DG from 2DG by precipitation, as described previously (29).

Protein expression in insulin signalling and lipid metabolism pathways

Proteins were extracted (~100 mg, NP n=10, D16 n=5, D19 n=5-6) from the liver and skeletal muscle and quantified using Western blotting as described previously [30]. Successful transfer and equal protein loading was confirmed by Ponceau-S staining of membranes before incubation with antibody (Table 1). Protein abundance was determined by measuring pixel intensity of the protein bands using ImageJ analysis software (U.S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Table 1.

List of primary antibodies used in this study.

| Primary antibody | Manufacturer | Dilution |

|---|---|---|

| Insulin receptor (InsR) | Santa Cruz, sc-711 | 1/400 |

| Insulin like growth factor receptor type 1 IGF1R | Santa Cruz, sc-713 | 1/400 |

| Catalytic subunits of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (p110α/β) | Cell Signalling, 4249, 3011 | 1/1000 |

| Regulatory subunits of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (p85α) | Millipore, 06-195 | 1/5000 in 1% milk |

| Kinase Akt | Cell Signalling, 9272 | 1/1000 |

| Phosphorylated (p)Akt Thr308 | Cell Signalling, 9275 | 1/1000 |

| pAkt Ser473 | Cell Signalling, 9271 | 1/1000 |

| Glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) | Cell Signalling, 9315 | 1/1000 |

| pGSK3 Ser21/9 | Cell Signalling, 9331 | 1/1000 |

| Ribosomal S6 kinase (S6K) | Cell Signalling, 2708 | 1/1000 |

| pS6K Thr 389 | Cell Signalling, 9234 | 1/1000 |

| Eukaryotic translocation initiation factor 4 binding protein (4EBP) | Cell Signalling, 9644 | 1/1000 |

| p4EBP Ser65 | Cell Signalling, 9451 | 1/1000 |

| Mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) | Cell Signalling, 4695 | 1/1000 |

| pMAPK Thr202/Tyr204 | Cell Signalling, 4370 | 1/1000 |

| Lipoprotein lipase (LPL) | Abcam, 21356 | 1/1000 |

| Sterol regulatory element binding protein (SREBP) | Abcam, 3259 | 1/200 |

| Fatty acid synthase (FAS) | Cell Signalling, 3180 | 1/1000 |

| Peroxisome proliferator – activated receptor alpha (PPARα) | Abcam, 8934 | 1/1500 |

| Peroxisome proliferator – activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) | Santa Cruz, sc-7273 | 1/200 |

| Fatty acid transport protein 1 (FATP1) | Santa Cruz, sc-31955 | 1/400 |

Statistics

All statistical analyses and calculations were performed on the GraphPad Prism 4.0. For most of the data, differences between NP, D16 and D19 animals were analysed by one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post hoc test. When the ANOVA indicated an effect of pregnancy, differences between D16 and D19 of pregnancy were assessed separately by unpaired t-test. Changes within the same group were assessed by paired t-test or by t-test the mean change differing from zero. For GTT and ITT protocols, the changes in glucose concentration were analysed by two-way ANOVA with time as a repeated measure. The area above the curve (AAC) in the GTT and area under the curve (AUC) in the ITT for the changes in glucose concentrations were calculated using the trapezoid rule. Fetal and placental data were averaged for each litter before calculation of mean values at each gestational age.

RESULTS

Biometry

Pregnant dams were heavier than NP females due to the gravid uterus and increased weights of several maternal tissues, although, when weights were expressed as a percentage of total or hysterectomised body weight, only the liver and retroperitoneal fat pads were proportionately heavier during pregnancy (Table 2). However, DEXA scanning showed that no significant changes in body fat content during pregnancy (Table 2). As expected [31], the gravid uterus and individual fetuses weighed less while the placentas weighed more at D16 than D19 with no difference in litter size between the two groups (Table 2). Hepatic fat and glycogen content were higher in total during pregnancy in line with the increased tissue weight but not when expressed per mg tissue (Table 2). Skeletal muscle fat content of pooled samples appeared to be greater in pregnant than NP animals when expressed per mg tissue (Table 2). Pregnant dams increased their food intake relative to NP females from D9 of pregnancy (data not shown).

Table 2.

The effect of pregnancy and gestational age on the biometry and biochemical composition in non-pregnant females and pregnant dams at day (D)16 and D19 of pregnancy.

| Non-pregnant | Pregnant | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| D16 | D19 | ||

| Biometry | |||

| Total body weight BW (g) | 21.0 ± 0.4a (20) | 31.0 ± 1.1b (13) | 35.0 ± 1.2b (16) |

| Hysterectomised weight HW (g) | - | 24.0 ± 0.7b (13) | 23.0 ± 0.8b (15) |

| Liver (mg) (% )† | 1099 ± 28a (10) | 1903 ± 57b (13) | 1856 ± 76b (16) |

| 5.5 ± 0.2a (10) | 7.9 ± 0.1b (13) | 8.1 ± 0.3b (16) | |

| Kidney (mg) (% )† | 234.0 ± 6.5a (10) | 277 ± 12b (11) | 271 ± 11b (15) |

| 1.20 ± 0.02 (10) | 1.10 ± 0.02 (11) | 1.20 ± 0.04 (15) | |

| Heart (mg) (% )† | 106.0 ± 6.5a (10) | 132 ± 5b (13) | 137 ± 7b (16) |

| 0.50 ± 0.03 (10) | 0.50 ± 0.01 (13) | 0.60 ± 0.03 (16) | |

| Retroperitoneal fat (mg) (%)† | 30 ± 2a (16) | 73 ± 7b (13) | 63 ± 6b (16) |

| 0.1 ± 2.0a (16) | 0.30 ± 0.03b (13) | 0.30 ± 0.03b (16) | |

| Gravid uterus (g) | - | 7.3 ± 0.4 (13) | 11.2 ± 0.7* (15) |

| Placenta average per litter (mg) | - | 104.0 ± 1.8 (13) | 88.0 ± 2.7* (16) |

| Fetus average per litter (mg) | - | 427 ± 12 (13) | 1204 ± 17* (16) |

| Litter size | - | 7.8 ± 0.5 (13) | 7.1 ± 0.4 (16) |

| Biochemical composition | |||

| DEXA absolute fat mass (g)† | 3.9 ± 0.2 (10) | 4.4 ± 0.3 (7) | 4.5 ± 0.2 (7) |

| DEXA fat mass (%)† | 17.6 ± 0.9 (10) | 17.8 ± 1.2 (7) | 19.2 ± 0.5 (7) |

| DEXA absolute lean mass (g)† | 18.2 ± 0.6a (10) | 20.3 ± 0.5b (7) | 18.7 ± 0.7ab (10) |

| DEXA lean mass (%)† | 82.4 ± 0.9 (10) | 82.3 ± 1.2 (7) | 80.9 ± 0.5 (10) |

| Hepatic glycogen (mg/g) | 55 ± 3 (15) | 49 ± 1 (6) | 57 ± 6 (6) |

| Total hepatic glycogen (mg) | 61 ± 4a (15) | 86 ± 3b (6) | 103 ± 11b (6) |

| Hepatic fat content (%) | 5.4 ± 0.3 (15) | 5.1 ± 0.3 (6) | 4.7 ± 0.3 (6) |

| Total hepatic fat content (mg) | 59 ± 5a (15) | 91 ± 6b (6) | 86 ± 6b (6) |

| Skeletal muscle fat content (%)§ | 4.0 | 15.4 | 20.4 |

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM with the number of dams/litters in parentheses. Values with different superscripts are significantly different from each other (p<0.05, one way ANOVA).

significant difference between D16 and D19 pregnant dams (p<0.05, t-test).

Organ weights and DEXA results were expressed as % of total body weight for NP females and of hysterectomised for pregnant dams.

skeletal muscle fat content was measured on samples pooled from 3-5 animals from each group.

Metabolites and hormones concentrations

Blood glucose concentrations were unaffected by pregnancy in the fed state but were significantly lower than NP values in both pregnant groups after 3.5 h of fasting (Table 3). At 6 h of fasting, blood glucose levels were similar to those seen at 3.5 h of fasting in NP and D19 groups but were significantly higher than at 3.5 h of fasting in D16 dams (Table 3). In fed animals, plasma FFA concentrations were significantly lower in both pregnant groups than in NP females with the lowest values in D16 dams (Table 3). Cholesterol concentrations were also significantly lower during pregnancy and declined significantly between D16 and D19 (Table 3). Insulin concentrations were significantly higher in D16 dams than NP females with intermediate values in D19 dams (Table 3). Plasma leptin concentrations were higher while plasma IGF1 levels were lower in pregnant than NP groups, with no significant differences with gestational age (Table 3).

Table 3.

The effect of pregnancy and gestational age on blood glucose concentrations in the fed and fasted state, plasma concentrations of free fatty acids (FFA), triglycerides (TG), cholesterol, insulin, leptin and insulin-like growth factor (IGF)1 in non-pregnant females and dams at day (D)16 and D19 of pregnancy in the fed state.

| Non-pregnant | Pregnant | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| D16 | D19 | ||

| Glucose Fed state (mmol/l) | 9.3 ± 0.5 (10) | 10.3 ± 0.3 (11) | 9.4 ± 0.6 (16) |

| Fasted 3.5h (mmol/l) | 7.1 ± 0.4a (8) | 5.3 ± 0.3b (6) | 5.5 ± 0.3b (6) |

| Fasted 6h (mmol/l) | 6.9 ± 0.3a (11) | 6.8 ± 0.2a† (9) | 5.2 ± 0.3b (8) |

| FFA Fed (μmol/l) | 637 ± 49a (10) | 256 ± 42b (9) | 381 ± 41b*(10) |

| TG Fed (mmol/l) | 1.0 ± 0.1 (10) | 1.2 ± 0.2 (9) | 1.0 ± 0.1 (10) |

| Cholesterol Fed (mmol/l) | 1.8 ± 0.1a (10) | 1.4 ± 0.1b (9) | 1.0 ± 0.1c (10) |

| Insulin Fed (μg/L) | 0.19 ± 0.04a (10) | 1.3 ± 0.3b (10) | 0.6 ± 0.1ab (10) |

| Leptin Fed (pg/ml) | 766 ± 71a (10) | 4058 ± 656b (10) | 3927 ± 709b (10) |

| IGF1 Fed (pg/ml) | 487 ± 68a (10) | 299 ± 23b (12) | 253 ± 20b (12) |

Data are expressed as mean±SEM with the number of animals shown in parentheses. Values with different superscripts are significantly different from each other (p<0.05, one way ANOVA). The asterisk indicates a significant difference between D16 and D19 of pregnancy (p<0.05, t-test).

indicates a significantly different values between animals fasted for 3.5h and 6h in the same group.

Glucose tolerance

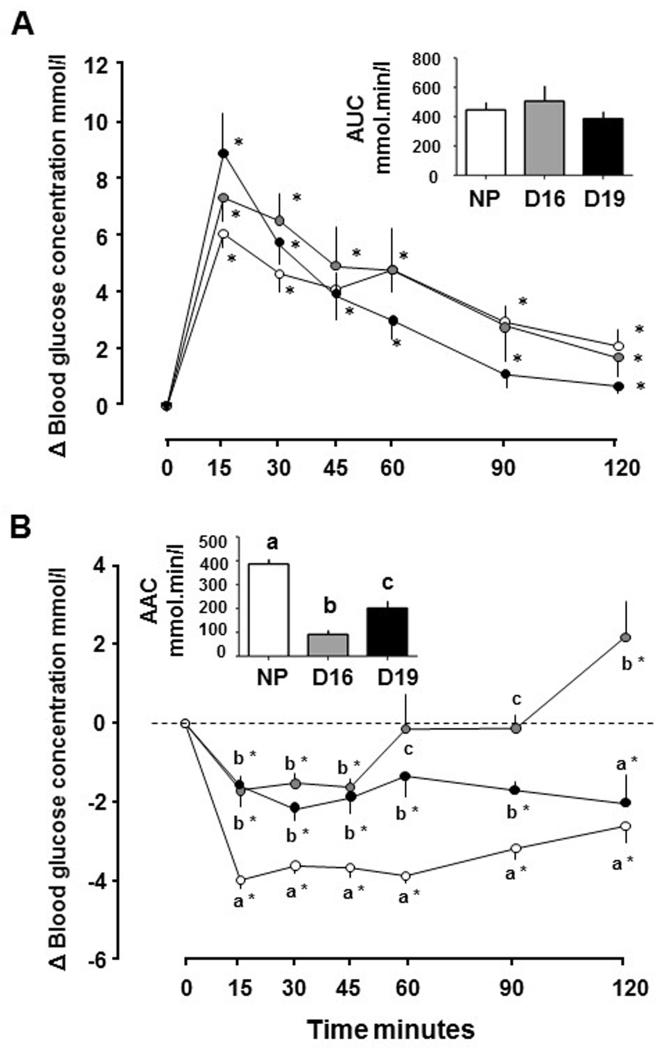

The increment in blood glucose concentrations, the time course of the concentration changes and the AUC did not differ with pregnancy or gestational age (Figure 1A). Blood glucose concentrations remained elevated for the entire 120 min after glucose injection in all 3 groups (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Mean ± SEM changes in blood glucose concentrations from basal pre-treatment values with time after intraperitoneal administration of (A) glucose (1 g/kg) and (B) insulin (0.25 U/kg) in non-pregnant (NP) females (n=8-11, open symbols) and pregnant dams at day (D)16 (n=6-9, grey symbols) and D19 (n=6-8, black symbols). Inserts show area (a) under the glucose curve (AUC) and (b) above the glucose curve (AAC). In (a) and (b), *significant increment above baseline values in each group (p<0.05, paired t-test). In (b) values at each sampling time with different letters indicate significant differences between groups (p<0.05, one way ANOVA).

Insulin sensitivity

Blood glucose concentrations were significantly lower than baseline 15 min after acute insulin injection in all 3 groups and remained depressed for up to 120 min (Figure 1B). However, the decrement in blood glucose concentrations was greater in NP than both pregnant groups from 15-90 min after insulin injection (Figure 1B). In D16 dams, blood glucose level returned to baseline by 60 min and were significantly greater than baseline 120 min after insulin injection (Figure 1B). The AAC also differed significantly with pregnancy and gestational age, and indicated that pregnant dams were less sensitive to insulin than NP females, particularly at D16 (Figure 1B).

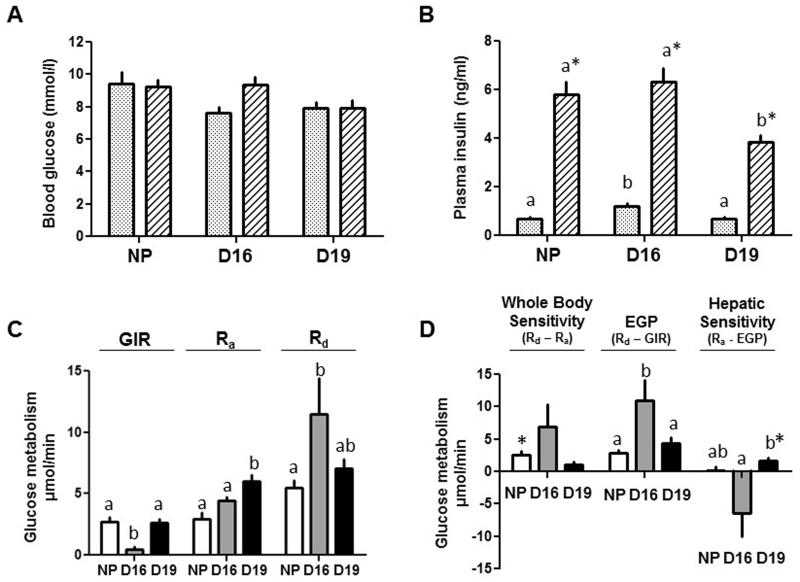

Whole body and hepatic insulin sensitivity were investigated in more detail by HEC coupled with 3H-glucose infusion. In all 3 groups, blood glucose levels were clamped at basal, euglycaemic levels by 70-90 min after beginning insulin infusion (Figure 2A). At this time, plasma insulin concentrations were within the post-prandial range and 5-6 fold higher than the basal values in all 3 groups (Figure 2B). However, steady-state insulin concentrations during the clamp were significantly lower in the D19 than NP or D16 groups (Figure 2B). Whole body insulin sensitivity, measured as GIR, was lower in D16 dams than in the other two groups and similar in NP and D19 pregnant groups (Figure 2C). The findings were identical when GIR was adjusted for the differences in the increment in insulin concentration during the clamp period (data not shown). Whole body insulin sensitivity was also calculated as the difference between glucose utilisation in hyperinsulinaemic (Rd) and basal states (Ra). This difference varied widely between individuals, particularly in D16 dams, and was only a significant increment in NP females, indicative of insulin resistance in both D16 and D19 dams (Figure 2D). During hyperinsulinaemia, EGP continued at a significant rate in all 3 groups (p<0.02, greater than zero, all groups, t-test) and occurred at the highest rate in D16 dams (Figure 2D). Hepatic insulin sensitivity, calculated as a significant difference in glucose production between basal and hyperinsulinaemic states, was only detected in D19 dams and was greater in absolute value at D19 than D16 (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Mean ± SEM concentrations of (A) blood glucose and (B) plasma insulin in the basal (stippled columns) and hyperinsulinaemic (Stripped columns) periods of the hyperinsulinaemic-euglycaemic clamp, rates of glucose infusion (GIR), appearance (Ra) and disappearance (Rd) measured directly (C) or derived indirectly as differences in rates (D) from tritiated glucose infusion and the HEC protocol (whole body and hepatic insulin sensitivity and endogenous glucose production, EGP) in non-pregnant (NP) females (n=7, white columns) and pregnant dams at D16 (n=5, grey columns) and D19 (n=6, black columns). In (B) *significant difference in concentration from the basal period (p<0.01, paired t-test) while, within each period of the clamp, values with different superscripts are significantly different from each other (p<0.05, one-way ANOVA). In (C) and (D) rates with different superscripts are significantly different from each other (p<0.05, one-way ANOVA). In (D) * significant difference between the values in the two states of the clamp (P<0.02, paired t-test).

Whole body and tissue glucose utilisation

Whole body glucose utilization was significantly greater in D19 dams than NP females in basal conditions (Ra) while, during hyperinsulinaemia (Rd), it was higher in D16 dams than NP females with intermediate values in D19 dams (Figure 2C). Tissue glucose utilization during hyperinsulinaemia, measured as p2DG content, in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue varied widely, particularly in NP females, but was not significantly different between pregnant and NP animals nor between D16 and D19 dams (Table 4). Fetal p2DG content was similar to that of maternal tissues at both ages (Table 4). Placental p2DG content was significantly higher than in the fetus or maternal tissues at D19, but not at D16 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Glucose utilisation by skeletal muscle and adipose tissue of the adult non-pregnant and pregnant mice and by the feto-placental tissues of the pregnant dams at day (D)16 and D19 of pregnancy.

| p2DG content (nmol/mg) | Non-pregnant | Pregnant | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| D16 | D19 | ||

| Skeletal muscle | 6.8 ± 2.4 | 4.2 ± 2.1 | 2.0 ± 0.6 |

| White adipose tissue | 3.2 ± 1.3 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.8 |

| Placenta | - | 4.8 ± 1.9 | 5.4 ± 1.2† |

| Fetus | - | 3.5 ± 1.8 | 1.7 ± 0.3 |

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM for non-pregnant females (n=7) and pregnant dams/litters (D16 n=5, D19 n=6 with 2 conceptuses per litter).

Significantly different from the other tissues at this stage of pregnancy (p<0.01, one-way ANOVA).

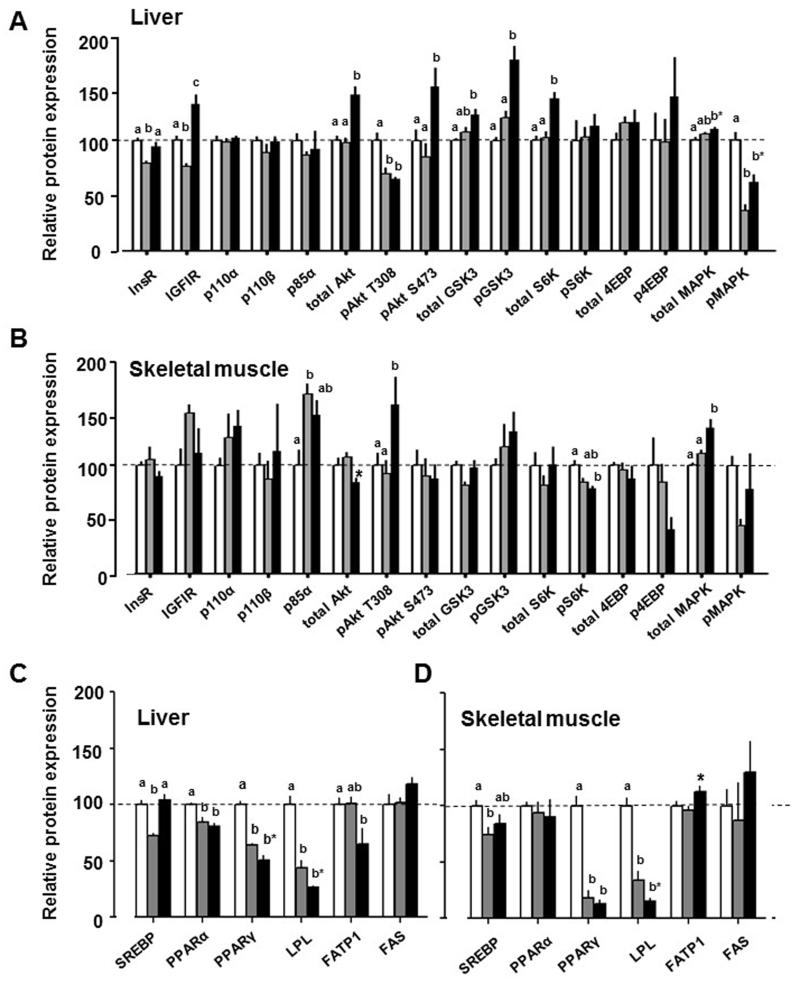

Tissue insulin-IGF signalling and lipid metabolism

Hepatic insulin-IGF signalling pathway was largely downregulated in D16 dams compared with NP females (InsR, IGF1R, pAkt-T308, pMAPK, Figure 3A). In contrast, at D19, the insulin signalling pathway was largely upregulated, compared to NP and D16 pregnant groups (IGF1R, total Akt, pAkt-S473, total Gsk3, pGsk3, total S6K, total MAPK and pMAPK, Figure 3A). Pregnancy had less effect on insulin signalling pathways in skeletal muscle with increased abundance of p85α at D16 and of pAkt T308 and total MAPK at D19 compared to NP values and decreased total Akt and pS6K abundance at D19 compared to either NP or D16 values (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Mean ± SEM abundance of insulin signalling (a,b) and lipid metabolism (c,d) proteins in liver (A, C) and skeletal muscle (B, D) of non-pregnant (NP) females (n=10, white columns) and pregnant dams at D16 (n=5, grey columns) and D19 (n=5-6, black columns). Values with different superscripts are significantly different from each other (p<0.05, one way ANOVA). *significant difference between D16 and D19 dams (p<0.05, t-test).

Hepatic abundance of lipogenic SREBP was reduced at D16 but normalised by D19 while PPARα, PPARγ and LPL were reduced in both pregnant groups relative to NP values (Figure 3C). Hepatic abundance of PPARγ and LPL was significantly lower in D19 than D16 dams (Figure 3D). Hepatic FATP1 was lower in D19 dams than NP females (Figure 3C). In skeletal muscle, SREBP was reduced in D16 but not D19 dams while PPARγ and LPL abundance were lower in both pregnant groups relative to NP values (Figure 3D). Skeletal muscle expression of LPL was greater and FATP1 was less at D16 than D19 (Figure 3D).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to measure insulin sensitivity of glucose metabolism in pregnant mice and shows significant changes in insulin-glucose dynamics with both pregnancy and gestational age over the last 20% of gestation. In particular, there were changes in insulin concentration, glucose utilization and production, and in whole body and tissue insulin sensitivity between D16 and D19 of pregnancy. Protein abundance in the hepatic and skeletal muscle insulin signalling pathways also differed during pregnancy in line with the gestational changes in insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism. Overall, insulin resistance and EGP capacity were more pronounced at D16 than D19, which indicates that mice adapt their metabolic strategy for supporting pregnancy as delivery approaches. There were also changes in body composition, tissue lipogenic signalling proteins and circulating concentrations of leptin and IGFI during pregnancy which indicate that, like other species (2,5), mice accumulate fat in specific deposits during early but not late pregnancy and are resistant to the actions of leptin, as well as insulin, in late pregnancy, when their food intake increases despite hyperleptinaemia.

While glucose tolerance was unaffected by pregnancy, insulin resistance was evident in D16 pregnant mice. These dams were hyperinsulinaemic in both fed and fasted states, had a significantly smaller hypoglycaemic response to acute insulin administration and required 80-85% less exogenous glucose to maintain euglycaemia during the HEC than the other two groups of animals. This decrement in GIR from NP values was greater than seen in rats, dogs and women at an equivalent stage of pregnancy (7,9,12). In addition, insulin failed to inhibit EGP in D16 mouse dams. Similar findings have been made in pregnant rats but, in women, rabbits and dogs with a proportionately smaller gravid uterus, insulin continues to reduce EGP during late pregnancy, although not always as effectively as in the NP state (9,10,12,14,15). Furthermore, whole body glucose utilisation varied widely and did not increase significantly during hyperinsulinaemia in D16 pregnant mice, unlike the significant increment seen in NP females. Although there were no significant changes in tissue p2DG content, skeletal muscle expression of p85α, a known regulator of human muscle insulin resistance (32), was increased while hepatic expression of IR and several downstream insulin signalling proteins were decreased in D16 mouse dams, consistent with their reduced whole body and liver insulin sensitivity. Collectively, these findings indicate that insulin resistance occurs at whole body, tissue and molecular levels at D16 of mouse pregnancy.

By D19, insulin concentrations in fed and fasted states had returned to NP levels and the hypoglycaemic response to acute insulin administration was greater than at D16, although still less than in NP females. Insulin concentrations were also lower during the clamp in D19 dams which suggests increased insulin clearance consistent with findings in dogs during late pregnancy (12). A degree of hepatic insulin sensitivity was restored in D19 pregnant mice as insulin infusion now reduced EGP. Hepatic expression of several proteins in the insulin signalling pathway were also up-regulated at D19 relative to the other two groups. Improved hepatic insulin signalling at D19 is also suggested by normalised expression of the insulin-regulated transcription factor, SREBP (33). Furthermore, the GIR required to maintain euglycamia during hyperinsulinaemia was significantly greater at D19 than D16, indicative of improved whole body insulin sensitivity near term. However, tissue p2DG content showed no change between D16 and D19, and whole body glucose utilisation was unresponsive to insulin at D19, which suggests that a degree of insulin resistance still persists in pregnant mice close to delivery. These apparent contradictions probably reflect the non-insulin dependent, transplacental flux of glucose, which would increase GIR and lead to overestimation of the actual maternal insulin sensitivity, particularly when fetal glucose demands are high near term (2,34). Insulin sensitivity, therefore, appears to change differentially in individual maternal tissues with proximity to delivery in pregnant mice.

In basal conditions, the rate of endogenous glucose production (Ra) in the NP females fasted for 3.5hr in the present study was higher than that seen previously in older male mice fasted overnight (25). Insulin also had little effect on the rate of EGP in NP females in the present study compared to its inhibitory actions in males published previously (25). Whether these differences are sex-linked or due to the differing ages and length of fasting remain unclear but insulin sensitivity is known to be greater in juvenile than adult animals and in adult women than men (35,36). In the present study, basal glucose production (Ra) was higher in pregnant than NP females as seen previously in dogs, sheep and women during late pregnancy (11,12,14). In mice, this is consistent with the greater total availability of hepatic glycogen associated with the increased relative size of the liver during pregnancy. Particularly at D16, EGP was activated readily and sustained for several hours. Blood glucose concentrations were higher after fasting for 6 h than 3.5 h and could be increased above pre-treatment levels 2 h after initiating an acute hypoglycaemic challenge at D16 but not D19. EGP were also significantly higher during hyperinsulinaemia in D16 dams than in the other two groups. Since hepatic glycogen content and activity of glucose-6-phosphatase are similar at D16 and D19 (37), the results indicate that, in addition to differences in hepatic insulin sensitivity, there may also be a greater gluconeogenic capacity and/or a more robust counter-regulatory response to hypoglycaemia at D16 than D19. Mice may, therefore, appear to rely more heavily on glucose production to meet the glucose demands of the gravid uterus at D16 than D19. Although the causes of the changes in insulin sensitivity and glucose production with proximity to delivery remain unknown, they closely parallel gestational changes in maternal concentrations of corticosterone, a known insulin antagonist (4,37), with maximal values at D16 and progressively declining concentrations thereafter towards term (38).

Fetal glucose utilisation tended to be less at D19 than D16, consistent with the changes in glucose metabolism seen in fetal sheep towards term (39). At D19, weight specific rates of glucose utilisation by the fetus (≈ 39 μmol/min/kg) and placenta (≈ 120 μmol/min/kg), estimated from their p2DG contents, were within the range of values reported previously for other species at ≥ 90% of gestation (40-42). Estimation of total feto-placental glucose utilization by the whole litter indicates that this increases by 15-20% between D16 and D19 while total conceptus mass increases by 120%. Mouse pups must, therefore, be using nutrients other than glucose to sustain their growth rate during late gestation. Indeed, previous studies have shown that their growth is positively correlated to placental glucose transport at D16, but not at D19, and becomes progressively more dependent on placental amino acid transport towards term (43). A greater ATP requirement for active amino acid transport by the D19 placenta is consistent with its high rate of glucose utilization relative to other fetal and maternal tissues at this age. In addition, the lower maternal FFA and cholesterol concentrations during pregnancy indicate that lipids may also provide alternative substrates for feto-placental tissues during late gestation (44).

In summary, the marked insulin resistance of glucose utilisation and production at D16 will favour fetal glucose acquisition when fetuses are entering their maximal growth phase (31). When the fetuses have nearly reached term weight and can use other substrates at D19, insulin sensitivity of maternal tissues like the liver improves, which will conserve proportionally more glucose for maternal use in anticipation of the imminent demands of labour and lactation. This late change in insulin-glucose dynamics is likely to be particularly important in mice in which the gravid uterus accounts for such a large proportion of maternal weight at term but may also have a significant role in the maternal metabolic preparations for delivery in other species when the primary site of maternal-offspring nutrient allocation switches from the uterus to the mammary gland.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the staff of the animal facilities for their care of the mice.

FUNDING

We are grateful to the Medical Research Council for funding the research through a studentship to Barbara Musial and an in vivo skills award (MR/J500458/1 and MRC CORD G0600717).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

GUARANTOR STATEMENT

Professor Fowden is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is an author-created, uncopyedited electronic version of an article accepted for publication in Diabetes. The American Diabetes Care Association (ADA), publisher of Diabetes, is not responsible for any errors or omissions in this version of the manuscript or any version derived from it by third parties. The definitive publisher-authenticated version will be available in a future issue of Diabetes in print and online at http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Di Cianni G, Micooli R, Volpe L, Lencioni C, Del Prato S. Intermediate metabolism in normal pregnancy and in gestational diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2003;19:259–270. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Catalano PM. Obesity, insulin resistance and pregnancy outcome. Reproduction. 2010;140:365–371. doi: 10.1530/REP-10-0088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ladyman SR, Augustine RA, Grattan DR. Hormone interactions regulating energy balance during pregnancy. J Neuroendocrinol. 2010;22:805–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2010.02017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vejrazkova D, Vcelak J, Vankova M, Lukasova O, Halkova T, Kancheva R, Bendlova B. Steroids and insulin resistance in pregnancy. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;139:122–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.López-Luna P, Muñoz T, Herrera E. Body fat in pregnant rats at mid- and late-gestation. Life Sci. 1986;39:1389–1393. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(86)90338-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramos MP, Crespo-Solans MD, del Campo S, Cacho J, Herrera E. Fat accumulation in the rat during early pregnancy is modulated by enhanced insulin responsiveness. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;285:E318–E328. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00456.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Catalano PM, Tyzbir ED, Wolfe RR, Calles J, Roman NM, Amini SB, Sims EA. Carbohydrate metabolism during pregnancy in control subjects and women with gestational diabetes. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:E60–E67. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1993.264.1.E60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryan EA, O’Sullivan MJ, Skyler JS. Insulin action during pregnancy: studies with the euglycaemic clamp technique. Diabetes. 1985;34:380–389. doi: 10.2337/diab.34.4.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leturque A, Ferre P, Satabin P, Kervran A, Girard J. In vivo insulin resistance during pregnancy in the rat. Diabetologia. 1980;19:521–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00253179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hauguel S, Gilbert M, Girard J. Pregnancy-induced insulin resistance in liver and skeletal muscle of the conscious rabbit. Am J Physiol. 1987;252:E165–E169. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1987.252.2.E165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petterson JA, Dunshea FR, Ehrhardt RA, Bell AW. Pregnancy and undernutrition alter glucose metabolic responses to insulin in sheep. J Nutr. 1993;123:1286–1295. doi: 10.1093/jn/123.7.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connolly CC, Papa T, Smith MS, Lacy DB, Wiliams PE, Moore MC. Hepatic and muscle insulin action during late pregnancy in the dog. Am J Physiol Regal Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292:R447–R452. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00385.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.George LA, Staniar WB, Cubitt TA, Treiber KH, Harris PA, Geor RJ. Evaluation of the effects of pregnancy on insulin sensitivity, insulin secretion, and glucose dynamics in Thoroughbred mares. Am J Vet Res. 2011;72:666–674. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.72.5.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Catalano PM, Tyzbir ED, Wolfe RR, Roman NR, Amini SB, Sims EAH. Longitudinal changes in basal hepatic glucose production and suppression during insulin infusion in normal pregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167:913–919. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(12)80011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davidson MB. Insulin resistance of late pregnancy does not include the liver. Metabolism. 1984;33:532–537. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(84)90008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fowden AL, Moore T. Maternal-fetal resource allocation: co-operation and conflict. Placenta. 2012;33:e11–5. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rawn SM, Cross JC. The evolustion, regulation and function of placenta-specific genes. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2008;24:159–181. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.24.110707.175418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rawn SM, Huiang C, Highes M, Shaykhutdinov R, Vogel HJ, Cross JC. Pregnancy hyperglycaemia in prolactin receptor deficient mutant but nor prolactin n=mutant mice and feeding-responsive regulation of placental lactogen genes implies placental control of maternal glucose homeostasis. Biol Reprod. 2012;93:75–1. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.115.132431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saad MJA, Maeda L, Breneli SL, Carvalho CRO, Paiva RS, Velloso LA. Defects in insulin signal transduction in liver and muscle of pregnant rats. Diabetologia. 1997;40:179–186. doi: 10.1007/s001250050660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Catalano PM, Nizielski SE, Shao J, Preston L, Qiao L, Friedman JE. 2002 Downregulated IRS-1 and PPARgamma in obese women with gestational diabetes: relationship to FFA during pregnancy. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002;282:E522–E533. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00124.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamashita H, Shao J, Friedman JE. Physiologic and molecular alterations in carbohydrate metabolism during pregnancy and gestational diabetes mellutis. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2000;43:87–98. doi: 10.1097/00003081-200003000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shao J, Yamashita H, Qiao L, Draznin B, Friedman JE. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase redistribution is associated with skeletal muscle insulin resistance in gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes. 2002;51:19–29. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedman JE, Ishizuka T, Shao J, Huston L, Highman T, Catalano P. Impaired glucose transport and insulin receptor tyrosine phosphorylation in skeletal muscle from obese women with gestational diabetes. Diabetes. 1999;48:1807–1814. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.9.1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vaughan OR, Sferruzzi-Perri AN, Coan PM, Fowden AL. Environmental regulation of placnetal phenotype: implications for fetal growth. Repro Fert Develop. 2012;24:80–96. doi: 10.1071/RD11909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Voshol PJ, Jong MC, Dahlmans VEH, Kratky D, Levak-Frank S, Zechner R, Romijn JA, Havekes LM. In muscle-specific lipoprotein lipase-overexpressing mice, muscle triglyceride content is increased without inhibition of insulin-stimulated whole-body and muscle-specific glucose uptake. Diabetes. 2001;50:2585–2590. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.11.2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leturque A, Burnol AF, Ferre P, Girard J. Pregnancy-induced insulin resistance in the rat: assessment by glucose clamp technique. Am J Physiol. 1984;246:E25–E31. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1984.246.1.E25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roehrig KL, Allred JB. Direct enzymatic procedure for the determination of liver glycogen. Anal Biochem. 1974;58:414–421. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(74)90210-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Folch J, Lees M, Sloane Stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipids from animal tissues. J Biol Chem. 1957;226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sacks W, Sacks S. Conversion of glucose phosphate-14C to glucose-14C in passage through human brain in vivo. J App Physiol. 1968;24:817–27. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1968.24.6.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sferruzzi-Perri AN, Vaughan OR, Coan PM, Suciu MC, Darbyshire R, Constancia M, Burton GJ, Fowden AL. Placental-specific Igf2 deficiency alters developmental adaptations to undernutrition in mice. Endocrinol. 2011;152:3202–3212. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-0240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coan PM, Ferguson-Smith AC, Burton GJ. Developmental dynamics of the definitive mouse placenta assessed by stereology. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:1806–1813. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.024166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barbour LA, Mizanoor Rahman S, Gurevich I, Leitner JW, Fischer SJ, Roper MD, Knotts TA, Vo Y, McCurdy CE, Yakar S, Leroith D, Kahn CR, Cantley LC, Friedman JE, Draznin B. Increased P85alpha is a potent negative regulator of skeletal muscle insulin signaling and induces in vivo insulin resistance associated with growth hormone excess. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:37489–37494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506967200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Porstmann T, Santos CR, Griffiths B, Cully M, Wu M, Leevers S, Griffiths JR, Chung YL, Schulze A. SREBP activity is regulated by mTORC1 and contributes to Akt-dependent cell growth. Cell Metab. 2008;8:224–236. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carrara MA, Batista MR, Saruhashi TR, Felisberto AM, Guilhermetti M, Bazotte RB. Coexistence of insulin resistance and increased glucose tolerance in pregnant rats: A physiological mechanism for glucose maintenance. Life Science. 2012;90:831–837. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2012.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yki-Jarvinen H. Sex and insulin sensitivity Metabolism. 1984;33:1011–1015. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(84)90229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barbieri M, Rizzo MR, Manzella D, Paolisso G. Age-related insulin resistance: is it an obligatory finding? The lesson from healthy centenarians. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2001;17:19–26. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vaughan OR, Fisher HM, Dionelis KN, Jefferies EC, Higgins JS, Musial B, Sferruzzi-Perri AN, Fowden AL. Corticosterone alters materno-fetal glucose partitioning and insulin signalling in pregnant mice. J Physiol. 2015;593:1307–1321. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.287177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barlow SM, Morrison PJ, Sullivan FM. Plasma corticosterone levels during pregnancy: the relative contribution of the adrenal glands and foeto-placental units. J Endocrinol. 1974;60:473–483. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0600473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hay WW, Myers SA, Sparks JW, Wilkening RB, Meschia G, Battaglia FC. Glucose and lactate oxidation rates in the fetal lamb. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1983;173:553–563. doi: 10.3181/00379727-173-41686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fowden AL. Comparative aspects of fetal carbohydrate metabolism. Equine Vet J. 1997;24:19–25. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.1997.tb05074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leturque A, Hauguel S, Kande J, Girard J. Glucose utilization by the placenta of anesthetized rats: effect of insulin, glucose and ketone bodies. Pediatr Res. 1987;22:483–487. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198710000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haggarty P, Allstaff S, Hoad G, Ashton J, Abramovich DR. Placental nutrient transfer capacity and fetal growth. Placenta. 2002;23:86–92. doi: 10.1053/plac.2001.0743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coan PM, Vaughan OR, McCarthy J, Mactier C, Burton GJ, Constancia M, Fowden AL. Dietary composition programmes placental phenotype in mice. J. Physiol. 2011;589:3659–3670. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.208629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Woollett LA. Review: transport of maternal cholesterol to the fetal circulation. Placenta. 2011;32(Suppl. 2):S218–21. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]