Abstract

The plant bug, Nesidiocoris tenuis (Hemiptera: Miridae), is one of the most thermophilous dicyphines in agroecosystems and is widely distributed in China. Little is known regarding the genetic structure of N. tenuis and the effect of historical climatic fluctuations on N. tenuis populations. We analyzed partial sequences of three mitochondrial protein-coding genes (COI, ND2 and CytB) and nuclear genes (5.8S, ITS2 and 28S) for 516 specimens collected from 37 localities across China. Analyses of the combined mitochondrial dataset indicated that the Southwestern China group (SWC) was significantly differentiated from the remaining populations, other Chinese group (OC). Asymmetric migration and high level of gene flow across a long distance within the OC group was detected. The long-distance dispersal of N. tenuis might be affected by air currents and human interference. Both the neutrality tests and mismatch distributions revealed the occurrence of historical population expansion. Bayesian skyline plot analyses with two different substitution rates indicated that N. tenuis might follow the post-LGM (the Last Glacial Maximum) expansion pattern for temperate species. Pleistocene climatic fluctuation, complicated topography and anthropogenic factors, along with other ecological factors (e.g. temperature and air current) might have accounted for the current population structure of N. tenuis.

The plant bug Nesidiocoris tenuis is considered as a major natural enemy and has shown its beneficial role in control of several pests such as whiteflies, leafminers, aphids, thrips and spider mites1. This species also may feed on certain host plants (e.g. tobacco) causing flower abortion and viral diseases under prey shortage conditions1,2, but the relevant studies demonstrated that when the N. tenuis populations are well established, pest infestation is less severe1 and financial gain due to reduction in pest numbers greatly exceeds any losses3. N. tenuis is currently widely commercialized and mass supplied in southern and warm production areas1,3. Although the bug is small in size and exhibits limited ability for active dispersal4, it is widely distributed in China5. As one of the most thermophilous species of all dicyphines6, the range of N. tenuis covers various climate types, from temperate to subtropical and tropical region4. Thus, China provides excellent opportunity to study population genetics and demographic history of N. tenuis, due to, wide range of climate types and the presence of several refugia.

N. tenuis is a model organism of biological control potential, and knowledge of its population genetics and associated factors is fundamentally crucial for species management and conservation strategies. Multiple factors can influence population dynamics, genetic diversity and population structure7. For example, strong dispersal ability and human interference promote frequent gene flow between populations, which can decrease genetic subdivision within populations. In contrast, low gene flow between populations can lead to genetic subdivision of populations8, and genetic divergence arises from geographic barriers, adaptation to pesticides and other environmental factors7,9. The Quaternary Period has played an important role in shaping current distribution and genetic diversity of organisms on earth10. Sea level, ocean currents and peninsular climate have changed repeatedly during the Pleistocene, and organisms have shown diverse contraction and expansion patterns, e.g. some species went extinct, some recolonized in new locations, some survived in refugia and expanded after glacial periods10. To date, a number of studies have focused on the morphology, biological characteristics, thermal biology of N. tenuis, and its efficacy against pests3,4,6,11. However, the factors for population structure of N. tenuis in China remained unknown.

Herein we investigated its genetic diversity, population structure and demographic history using sequences of mitochondrial and nuclear data. The objectives of this study were to (1) reveal the genetic distribution of N. tenuis related to current factors (geographical barriers, ecological factors and human interference); and (2) investigate demographic history of N. tenuis affected by Pleistocene climate fluctuation in China.

Results

Population genetic diversity and structure

For the mitochondrial genes, 27 haplotypes for COI, 65 haplotypes for ND2, and 30 haplotypes for CytB were identified, respectively. A total of 130 haplotypes were detected in a combined mitochondrial dataset, which included 2, 226 bp of protein-coding regions (COI: 726 bp, ND2: 837 bp and CytB: 663 bp). Among these identified haplotypes, 102 were unique haplotypes and six haplotypes (H1, H4, H6, H12, H13 and H17) were most widely shared. The H1 haplotype was shared by 120 individuals and was detected in most populations. The H4, H6, H12, H13, H17 haplotypes accounted for 9.50%, 7.75%, 10.47%, 5.04%, and 6.40%, respectively. In addition, we observed 145 polymorphic sites, which were composed of 54 parsimony-informative sites (2.29%) and 91 singleton-variable sites (4.09%). High haplotype diversity (Hd) and low nucleotide diversity (Pi) were shown in all 37 populations (Table S1). The haplotype diversity ranged from 0.705 (TX) to 1.000 (XICH) with the average of 0.913, while the nucleotide diversity ranged from 0.0012 (TX) to 0.0052 (KM) with the average of 0.0030 (Table S1).

For the nuclear data, 509 sequences were successfully obtained with the length of 753 bp (5.8S: 82 bp, ITS2: 423 bp and 28S: 248 bp). Compared to the results of the combined mitochondrial dataset, fewer haplotypes (HN = 30) and a lower level of genetic diversity (Hd = 0.183) were observed in the nuclear data. In addition, we observed 34 polymorphic sites, which were composed of one parsimony-informative site (0.13%) and 33 singleton-variable sites (4.38%).

For the combined mitochondrial dataset, the spatially explicit BAPS model for clustering of individuals identified three clusters in the 37 populations (Fig. 1). The first cluster (red color in Fig. 1), mainly distributed in three populations from Southwestern China, and accounted for 71.43% (KM), 70.00% (XICH), and 69.23% (QJ) of samples at each location. The second cluster (green color in Fig. 1) was distributed in the rest of the 34 populations as a majority (more than 53.33%), and the third cluster (yellow color in Fig. 1) was distributed as a minority (less than 35.7%).

Figure 1. Results of spatial clustering of the Nesidiocoris tenuis individuals analysis in the programs BAPS based on the combined mitochondrial dataset.

Pie chart with color indicates the proportion of three predicated clusters in each population. Upper-case letters are the abbreviation of 37 sampled locations. KM: Kunming, Yunnan; QJ: Qujing, Yunnan; XICH: Xichang, Sichuan; HNA: Danzhou, Hainan; YUX: Yuxi, Yunnan; DL: Dali, Yunnan; XAW: Xuanwei, Yunnan; YA: Yong’an, Fujian; HZ: Hezhou, Guangxi; XIX: Xinxiang, Henan; GY: Guiyang, Guizhou; ZY: Zunyi, Guizhou; ZHY: Zhenyuan, Guizhou; GM: Gaomi, Shandong; TS: Tangshan, Hebei; WEX: Wenxi, Shanxi; RY: Ruyuan, Guangdong; TX: Tongxiang, Zhejiang; SZ: Shengzhou, Zhejiang; JY: Jiangyin, Jiangsu; LX: Lanxi, Zhejiang; DZ: Dongzhi, Anhui; CHS: Changsha, Hunan; FC: Fengcheng, Jiangxi; BB: Bengbu, Anhui; NG: Ningguo, Anhui; XUC: Xuchang, Henan; DAC: Dancheng, Henan; DEZ: Dengzhou, Henan; XY: Xiangyang, Hubei; SL: Shangluo, Shaanxi; SYA: Yan’an, Shaanxi; XXA: Xi’an, Shaanxi; GUY: Guangyuan, Sichuan; HX: Huixian, Gansu; LZ: Lanzhou, Gansu; LF: Langfang, Hebei. Map was generated with ArcGIS 10.0 (http://www.esri.com/software/arcgis/arcgis-for-desktop) and modified with Adobe Photoshop CS6 (http://www.adobe.com/products/photoshop).

The pairwise FST values for genetic differentiation varied from −0.076 to 0.254 based on the combined mitochondrial dataset, and from −0.090 to 0.170 based on the nuclear data. For the combined mitochondrial dataset, three populations (KM, QJ and XICH) exhibited the most significant genetic differentiation (Table S2). Moreover, the pairwise FST values among KM, QJ and XICH population were relatively low and non-significant, indicating that high gene flow existed among these populations.

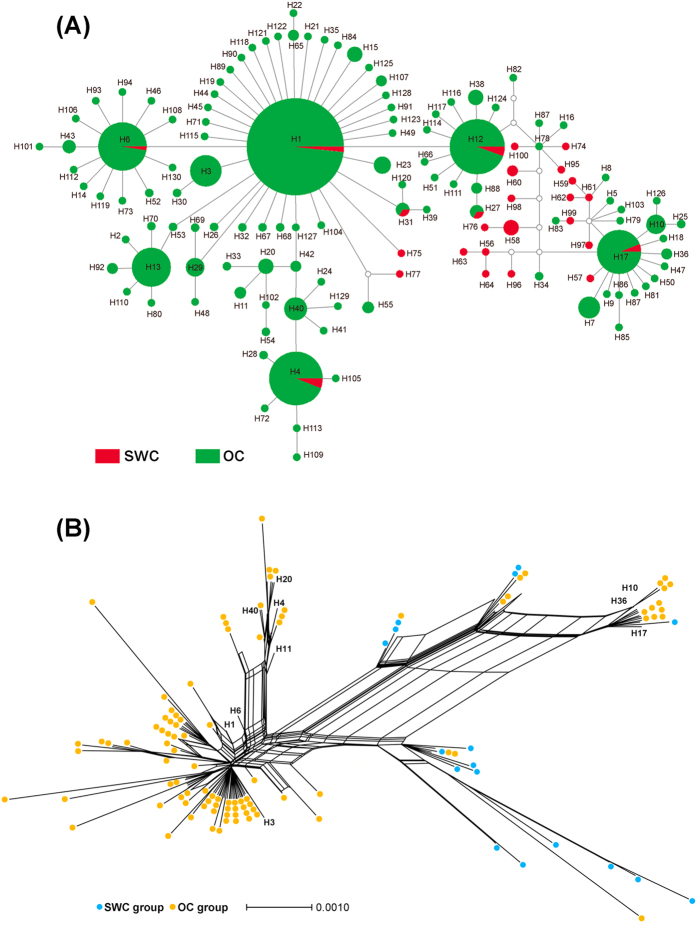

The median-joining network construction among the mitochondrial haplotypes also identified two groups (Fig. 2A), which was consistent with the result of BAPS analysis (Fig. 1). One group was the clustering of three Southwestern populations (KM, QJ and XICH) (red in Fig. 2A), which contained large amount of unique haplotypes and a few shared haplotypes. The other group included six most frequent haplotypes and their derived haplotypes from remaining populations (green in Fig. 2A). The ancestral haplotype H1 is represented by the largest circle. For the nuclear data, the median-joining network construction showed a big star-like shape with the H1 haplotype as the center, along with its derived haplotypes and no obvious geographically separated clusters (Fig. S2). Furthermore, the analysis using SplitsTree for the combined mitochondrial dataset revealed that a minor group was separated from the other haplotypes (blue color in Fig. 2B). This minor group was composed of haplotypes from three Southwestern populations (KM, QJ and XICH), corresponding to the result in Bayesian tree (Fig. S4) based on the combined mitochondrial haplotypes.

Figure 2. The median-joining network and splits network for Nesidiocoris tenuis based on the combined mitochondrial dataset.

(A) Haplotype network with the median-joining algorithm. The circle size of haplotype denotes the number of observed individuals. White dots represent lost haplotypes. The shortest trees with median vectors were shown. (B) The splits network constructed by the neighbor-net method. The “H” with a number represents the haplotype shared by different populations.

The results above suggested two well-supported groups as follows: the SWC group included three populations from Southwestern China (KM, QJ and XICH); and the OC group included the remaining 34 populations in China (JY, LX, FC, CHS, DZ, YUX, XAW, DL, YA, HZ, XIX, GY, ZY, ZHY, GM, TS, WEX, HNA, RY, TX, SZ, BB, NG, XUC, DAC, DEZ, XY, SL, SYA, XXA, GUY, HX, LZ, LF).

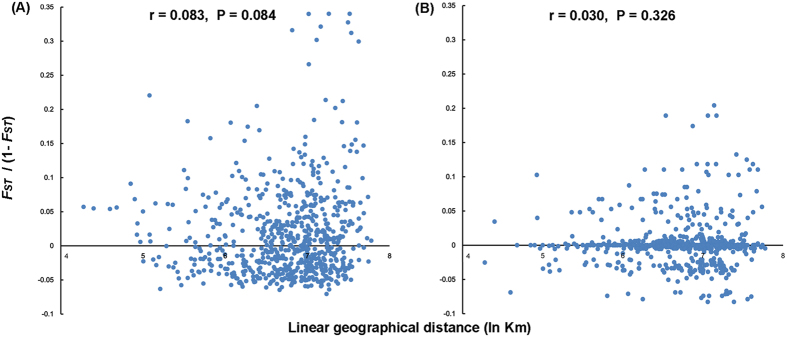

Non-significant isolation-by-distance (IBD) effect was detected among populations of N. tenuis, based on analyses of Mantel tests for both the combined mitochondrial dataset (r = 0.083, P = 0.084; Fig. 3A) and nuclear data (r = 0.030, P = 0.326; Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Scatter plots of genetic distance vs. geographic distance for pairwise population comparisons based on the combined mitochondrial dataset (A) and the nuclear data (B). Both analyses are calculated from 1,000 randomizations.

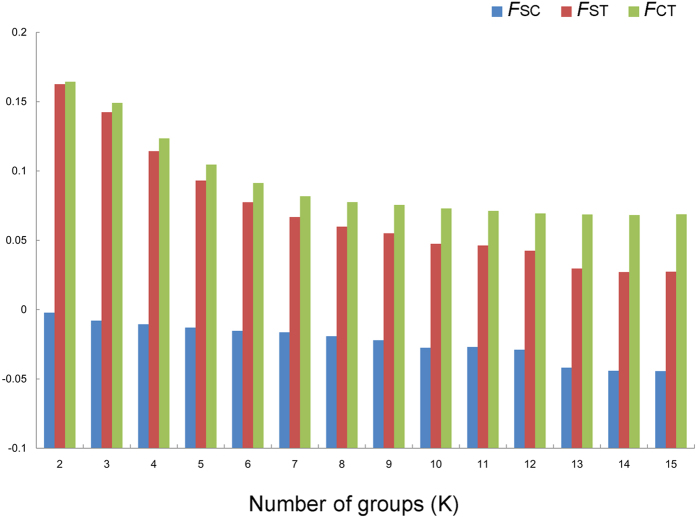

Hierarchical analysis of molecular variance and test to group definition

For the combined mitochondrial dataset, significant genetic structure among all populations (ΦST = 0.01809, P < 0.05) was observed. AMOVA analysis showed that 1.81% of the variation was partitioned among populations and the other 98.19% was within populations. SAMOVA analysis revealed that the FCT value reached the peak at K = 2 and decreased subsequently (Fig. 4), which supported a two-group structure. The pairwise FST value (FST = 0.1295, P < 0.001) also showed the significant genetic differentiation between two defined groups (SWC and OC). Moreover, the three-level AMOVA analysis indicated extremely significant structure between two groups (ΦCT = 0.1298, P < 0.001), with 12.97% genetic variation.

Figure 4. Fixation indices correspond to the number of groups (K) defined by SAMOVA analysis based on the combined mitochondrial dataset.

For the nuclear data, SAMOVA analysis demonstrated that the FCT was highest at eight groups when K value increased from 2 to 15 (Fig. S3). Non-significant genetic structure between two groups and most genetic variation (99.72%) within populations were detected using AMOVA analysis (Table 1).

Table 1. Hierarchical analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) for Nesidiocoris tenuis based on the combined mitochondrial dataset and the nuclear data.

| Gene | Source of variation | d.f. | SS | Percentage | Fixation indx |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COI+ND2+Cytb | Two level | ||||

| Among populations | 36 | 148.376 | 1.81 | ||

| Within populations | 479 | 1571.002 | 98.19 | ΦST = 0.0181* | |

| Three levels | |||||

| Among groups | 1 | 36.723 | 12.97 | ΦCT = 0.1298*** | |

| Among populations within groups | 35 | 111.653 | -0.17 | ΦSC = −0.0020 | |

| Within populations | 479 | 1571.002 | 87.20 | ΦST = 0.1280* | |

| 5.8S+ITS2+28S | Two level | ||||

| Among populations | 36 | 4.075 | 0.28 | ||

| Within populations | 472 | 51.442 | 99.72 | ΦST = 0.0028 | |

| Three levels | |||||

| Among groups | 1 | 0.178 | 0.77 | ΦCT = 0.0077 | |

| Among populations within groups | 35 | 3.896 | 0.15 | ΦSC = 0.0016 | |

| Within populations | 472 | 51.442 | 99.08 | ΦST = 0.0092 | |

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.02; ***P < 0.001. d.f., degree of freedom; SS, sum of squares.

Analyses on divergence of COI sequence indicate that genetic distances between the populations are in the range from 0.06% to 0.38%, and genetic distance between established groups SWC v OC is 0.28%.

Gene flow

The median-joining network analysis demonstrated that some haplotypes were widely shared, indicating the occurrence of frequent gene flow across China despite of long geographic distance (Fig. 2A and Fig. S2). It appeared that SWC group was significantly differentiated from OC group, and high level of gene flow existed between populations in OC group (Table S2). Therefore, analysis for direction of gene flow was performed within OC group.

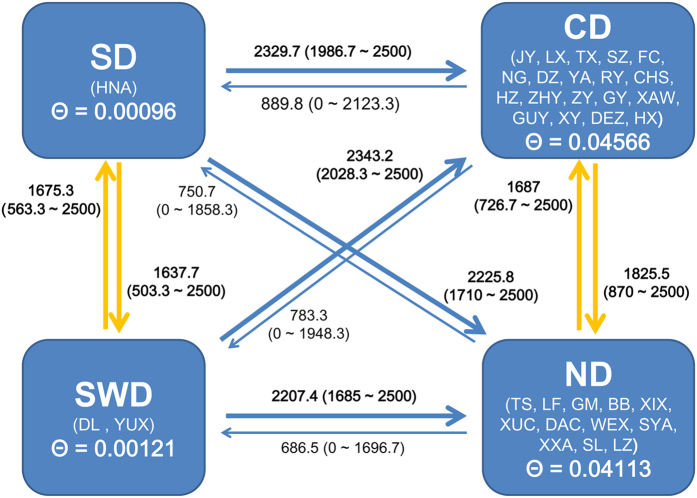

When four geographical districts were analyzed, estimates of effective population size (θ) were consistently low and ranged from 0.00096 for Southern District (SD) to 0.04566 for Central District (CD) (Fig. 5). Estimates of migration rate between regions were bi-directional and relatively high, which ranged from 686.5 to 2343.2. The highest M value (2343.2) was found for samples from Southwestern District (SWD) to CD, while the lowest M value (686.5) was for samples from the Northern District (ND) to SWD. Significant asymmetrical migration rates among long-distance district pairs, e.g. SWD-CD pair, were discovered by non-overlapping 95% confidence intervals of each estimate.

Figure 5. Estimates of the migration (M and θ) among four geographic districts of Nesidiocoris tenuis based on the combined mitochondrial dataset.

θ represents the mutation-scaled population size, and M indicates the mutation-scaled migration rate.

When the θ values and M values were translated into effective migrants per generation (Nem = θM), most migrants into CD (290.39) and ND (257.42) were obtained (Table S3). Estimate of migrants leaving out of SD and SWD was considerably high with the values of 199.90 and 199.39, respectively; however, extremely low values were detected for migrants entering into SD (3.18) and SWD (3.76). Therefore, SD and SWD were regarded as the major producers of migrants.

Demographic history

When two groups were defined, Fu and Li’s D*, Fu and Li’s F* and Tajima’s D values were not significantly negative in the SWC group, but were significantly negative in the OC group. When all samples were considered as one group, three neutrality tests were statistically significant (P < 0.02), which indicated that N. tenuis experienced recent demographic expansion (Table 2).

Table 2. Genetic diversity and demographic analysis for two defined groups (SWC and OC groups) and all samples of Nesidiocoris tenuis based on the combined mitochondrial dataset.

| Parameter | SWC group | OC group | All samples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hd | 0.976 | 0.904 | 0.912 |

| Pi | 0.0048 | 0.0028 | 0.0030 |

| Tajima’s D | −0.112 | −1.998* | −2.057* |

| Fu and Li’s D* | −0.277 | −11.268** | −10.598** |

| Fu and Li’s F* | −0.261 | −7.703** | −7.240** |

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.02. Hd, haplotype diversity; Pi, nucleotide diversity.

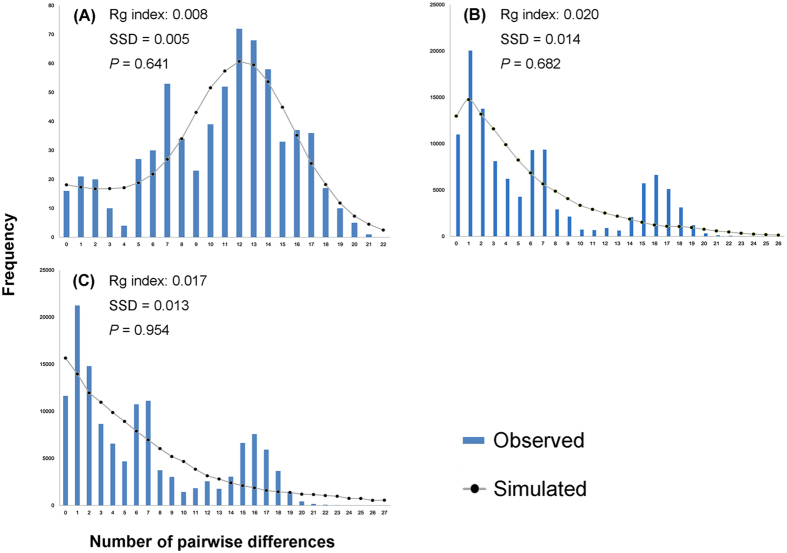

For SWC group, the multimodal mismatch distribution demonstrated that the group was under a model of population stability, which was consistent with the results of neutrality tests (Fig. 6A). OC group and whole populations were characterized by left skewed unimodal mismatch distributions, suggesting the population expansion models. Small Rg values but non-significant SSD values also indicated sudden population expansion, which was in line with the results of neutrality tests (Fig. 6B,C).

Figure 6.

Mismatch distributions of the combined mitochondrial dataset in the SWC group (A), OC group (B) and all samples of Nesidiocoris tenuis from China (C). X-axis represents the number of pairwise differences, and Y-axis represents the relative frequencies of pairwise comparisons.

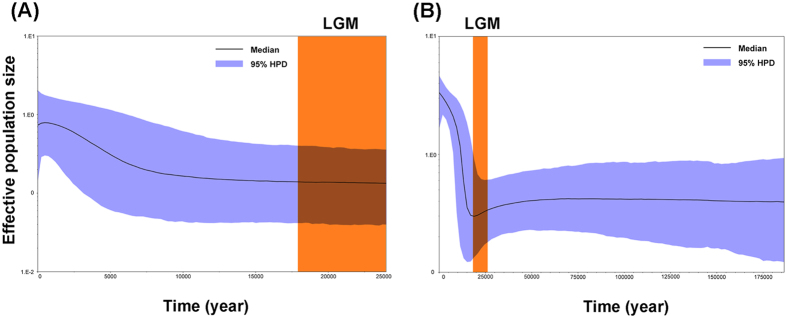

When using the Bayesian skyline plot with the substitution rate at 1.77% per million years based on COI gene, the effective population size of whole populations remained stable for a long period, and was followed by expansion about 9,000 years ago in a slow manner (Fig. 7A). Analysis with a slower substitution rate at 1.15% per million years based on the combined mitochondrial dataset also supported a growth pattern of effective population size through time, in which a sharp rise occurred about 15,000 years ago and later expanded in a considerably fast manner (Fig. 7B). Before the sharp rise, the population size remained stable over a long period, but a small decrease started after the last inter-glacial (LIG) and throughout the last glacial maximum12 (LGM: 26 Kya ~ 18 Kya; Kya: 1000 years ago). Both analyses suggested the population expansion after the LGM, which was the coldest period dating back.

Figure 7.

Demographic history of Nesidiocoris tenuis reconstructed using Bayesian skyline plots based on COI gene with substitution rate of 0.0177 (A) and the combined mitochondrial dataset with substitution rate of 0.0115 (B). X-axis is the timescale before present, and Y-axis is the estimated effective population size. Solid curves indicate median effective population size; the shaded range indicates 95% highest posterior density (HPD) intervals. LGM represents Last Glacial Maximum.

Discussion

According to Hebert13, more than 98% of species pairs exceed 2% sequence divergence, but divergences of COI sequence in our study are much less than 2%, suggesting that our result is in the context of divergences within species. Our analyses based on the combined mitochondrial dataset suggested that SWC group was significantly differentiated from OC group, while the analyses of nuclear data showed an extensive level of shared haplotypes between groups. Incongruence between mitochondrial and nuclear data is a common issue for phylogeographic study, which might be caused by various factors, e.g. potentially sex-biased dispersal, incomplete lineage sorting or recent secondary contact14,15,16,17. If males exhibited higher ability to disperse due to the natal philoparty of females, the expected result would be significant IBD effect based on the mitochondrial dataset and non-significant IBD effect based on nuclear data17,18. However, our analyses for both the mitochondrial and nuclear data displayed non-significant IDB effects, indicating that the incongruence could not be mainly explained by sex-biased dispersal (e.g. the higher male dispersal ability). In addition, we found that common haplotypes were widely shared by populations, and descendant haplotypes coexisted with ancestral haplotypes. This genetic pattern could be affected either by secondary contact or incomplete lineage sorting19. If the observed mitochondrial DNA pattern resulted from incomplete lineage sorting, a shallower divergence pattern would be expected in the nuclear data, given the larger effective population size and thus a longer sorting time20. However, no distinct genetic differentiation was revealed in nuclear data (Fig. S2), suggesting that incomplete lineage sorting was unlikely to be the primary factor.

Nesidiocoris tenuis was the most thermophilous species of all dicyphines in the Mediterranean region6, and our Bayesian skyline plot results suggested that this species might rapidly expand from refugial areas and establish secondary contact during the warm period after the LGM. Thus, the recent secondary contact followed by gene flow was mainly responsible for the incongruence between mitochondrial and nuclear data, which was reported in the vinous-throated parrotbill Paradoxornis webbianus21. Another apparent indication of recent secondary contact was found in the Hainan population (HNA). HNA population was expected to separate from the populations in the mainland due to its isolation by the Qiongzhou strait. However, our analysis revealed non-significant FST value between HNA and most continental populations. The most common haplotype (H1) was detected in the HNA population as well (Fig. 1). Such case was probably attributed to secondary contact by historically isolated refugia because the Quaternary glacial/interglacial cycles could cause the connection and isolation between Hainan Island and mainland repeatedly22.

The SWC group was located in the Hengduan Mountains, which were considered as one biodiversity hot-spot because of their temperature and humidity, specific topography, and refugia for many organisms23,24, especially in the suitable habitats for SWC group (e.g. higher genetic diversity in Table 2). Many unique haplotypes in the SWC group were not observed in other locations in the OC group, indicating habitat quality variation and geographic barriers might largely contribute to genetic division between SWC group and OC group. In addition, small local extinctions and different selection pressure might arise the phylogeographic breaks without geographic barriers25, e.g. SWC group and other sites located in the Hengduan Mountains (XAW, YUX and DL). The unique haplotypes in the SWC group were favored in local habitats because of selection pressure25, thus phylogeographic breaks could persist despite much gene flow.

N. tenuis populations in the OC group didn’t reveal a strong genetic division within a large range of locations, although its small size and limited ability for active dispersal might be expected to prevent gene flow. No correlation between genetic distance [FST/(1 − FST)] and geographic distance (ln Km) were determined using Mantel tests based on both molecular datasets, indicating IBD effect was non-significant among populations of N. tenuis in China (Fig. 3). Gene flow among populations across a long distance was observed within this group. The lowest pairwise FST values (−0.076) between CHS population and TS population (geographic distance = 1385.467 Km), and a non-significant FST value (0.007) was detected between the two furthest populations (TS and HNA; geographic distance = 2386.816 Km). We therefore speculated the homogeneity of populations was likely related to long-distance dispersal by human interference. It might be possible that biological companies introduced N. tenuis into different locations as a biological control agent and long-distance dispersal might be carried out due to the distribution chain operational in many countries11,26. Another possible human interference might be with respect to the frequent trade of crops, e.g. tobacco. Host plant dispersal could promote passive invading that was reported in the oriental fruit moth Grapholita molesta27. Likewise, a similar situation was reported for other small and sedentary species, e.g., booklouse Liposcelis bostrychophila was capable of long-distance dispersal (over 15,000 km) due to human-transport28, and the red flour beetle Tribolium castaneum widely colonized grain storages primarily through anthropogenic dispersal29.

Furthermore, our gene flow analyses confirmed long-distance dispersal, which demonstrated asymmetrical migration and high migration rates (Fig. 5). High migration rate was an indication of historically recurring gene flow, resulting from ancestral haplotypes persisting throughout glacial/interglacial periods and high frequencies of common haplotypes among regions30. A great number of migrants were detected moving from southern and southwestern districts to the central and northern districts of China, while rare migrants were obtained in the reverse direction (Table S3). The ‘South to North’ dispersal routes might be affected by thermal activity and air currents. Hughes et al. had shown limited dispersal abilities of N. tenuis from autumn to spring in certain temperate regions, while some dispersal would be possible in the summer4. Many small-sized insects could use air currents to carry out long-distance dispersal31. Our dispersal pattern of N. tenuis was consistent with that of the Asian subtropical monsoon, which occurs from southern and southwestern to northern direction in spring and summer31.

A variety of analyses indicated recent demographic expansion events for N. tenuis. Mitochondrial and nuclear network construction showed multiple star-like shapes, which implied that N. tenuis experienced population expansion events more than once32. Both the neutrality tests (Table 2) and mismatch distributions (Fig. 6C) indicated that N. tenuis experienced recent demographic expansion events. The results were in line with the estimates using Bayesian skyline plots with different rates (Fig. 7A,B). The estimated time of the expansion event, using the COI gene, was about 9 Kya (after the LGM). The interspecific substitution rate used in the previous COI analysis was much lower than mutation rate within species due to the delayed effects of purifying selection33. Consequently, our estimated population expansion time might be earlier. Based on the combined mitochondrial dataset, N. tenuis populations were estimated to start expanding nearly 15 Kya, which was consistent with the result of population expansion after the LGM. Although the results from the substitution rates based on COI gene and the combined mitochondrial dataset were different, the same post-LGM expansion pattern was obtained.

Unlike the expansion during the LIG to LGM transition, which has been observed in other organisms in Asia34,35, our results were consistent with the general consensus on a classic post-LGM expansion pattern for most thermophilous species in Europe. Moreover, our Bayesian skyline plot result based on the combined mitochondrial dataset demonstrated a contraction in population size during the LIG to LGM transition and throughout LGM period. We speculated that the demographic expansion of N. tenuis after the LGM was related to climate changes, because temperate species may present contracted distribution during glacial periods and experience range expansions during interglacial periods10. N. tenuis was proved to be the most thermophilous of all dicyphines in the Mediterranean region6 and lacks cold tolerance3,4. Thereby the numbers of beneficial habitats were increasing as the climate became warmer after the LGM. Other reasons for the demographic expansion after the LGM might be the wider distribution of the prey36 and human population expansions37 (~7 Kya), which provided food sources and long-distance dispersal to support rapid population expansion. The post-LGM expansion pattern was also observed in other insects such as the stable fly Stomoxys calcitrans38 and locusts Locusta migratoria39, whose effective population size rapidly increased approximately 12 Kya ~ 7 Kya and 5 Kya, respectively.

In summary, a combination of historical factors (the Quaternary glacials/interglacials cycles), ecological factors (specific topography and comfortable climate) and anthropogenic factors (passive dispersal ability by long-distance) might have shaped the current population structure pattern and dispersal routes of N. Tenuis.

Materials and Methods

Sample collection, DNA extraction and sequencing

In this study, a total of 516 adult N. tenuis individuals were collected from 37 locations, covering all representative distributions in China5. All specimens were stored in absolute ethanol at −20 °C until DNA extraction. Genomic DNA was extracted from single adult insect using a TIANamp genomic DNA kit (TIANGEN Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). The abdomen was removed prior to DNA extraction. Voucher specimens were deposited at the Entomological Museum of China Agricultural University, Beijing, China.

Considering the genetic variability of different genes, three mitochondrial protein-coding genes (a partial sequence of COI, a fragment of ND2 and partial CytB gene) and nuclear genes (partial 5.8S, complete ITS2 and partial 28S region) were used as molecular markers. Primers for three mitochondrial genes were specifically designed based on the complete mitochondrial genome of N. tenuis40, while primer pairs of nuclear data were used from a previous study41 (Table S4). The PCR amplifications were performed using Takara rTaq polymerase (Takara Biomedical, Japan) in a total volume of 25μl with the following conditions: an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 50 s, followed by 35–40 cycles with 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 45–52 °C, and 1–2 min at 72 °C, and a final extension step at 72 °C for 5 min. PCR products were visualized on 1.0% agarose gels under UV light. Purified PCR products were sequenced in both directions by Ruibo Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Beijing, China). All sequences have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers, KF017246 - KF017265 and KT598365 - KT598371 for COI, KT587084 - KT587148 for ND2, KT587054 - KT587083 for CytB, and KT587149 - KT587178 for ITS2 plus partial 5.8S and 28S.

Population genetic diversity and structure

Sequences of mitochondrial and nuclear markers were aligned independently using Clustal W implemented in MEGA version 5 42 with default parameters. Alignment of nucleotide sequences of the mitochondrial protein-coding genes (COI, ND2 and CytB) were inferred from the amino acid alignment. The number of polymorphic sites (S), the number of haplotypes (HN), haplotype diversity (Hd), nucleotide diversity (Pi) and average number of nucleotide differences (K) for each location were calculated using Arlequin version 3.5 43.

Several approaches were used in order to understand the population genetic structure of N. tenuis. The spatially explicit BAPS model for clustering of individuals, implemented in BAPS version 6.044, was performed for mitochondrial genes. 20 runs (K = 20) were performed to ensure consistency and convergence of the results. Pairwise FST analysis with 10,000 permutations was also calculated using Arlequin version 3.5 43 to estimate the genetic differentiation for population pairs. The median-joining networks among haplotypes were further reconstructed using Network version 4.6.1.3 45, based on the combined mitochondrial dataset and nuclear data independently.

To reveal the relationships among mitochondrial haplotypes, the splits network was constructed using SplitsTree version 4.13.1 46. The neighbor-net method was used under the p-distance model. Additionally, a phylogenetic tree based on the combined mitochondrial dataset was constructed with Bayesian inference (BI) using MrBayes version 3.2.1 47. The plant bug, Trigonotylus caelestialium, was chosen as the out-group48. Separate partitions were created for each gene in the combined mitochondrial dataset with the best-fit model that was determined under the Akaike Information Criterion using jModelTest version 0.1.1 49. The best-fit model was GTR+I+G for ND2, GTR+G for COI and GTR+G for CytB, respectively. The analysis was performed with two runs and four chains for 15 million generations, and the chains were sampled every 1000 generations. The first 25% of samples were discarded as burn-in.

To detect the effect of geographical isolation, Mantel tests50 with 1,000 randomizations for both the combined mitochondrial dataset and nuclear data were performed. The correlations of matrix of genetic distances [FST/(1 − FST)] vs. linear geographic distance (ln Km) were investigated using Mantel tests implemented in the software Arlequin version 3.543.

Hierarchical analysis of molecular variance and test to group definition

The spatial analysis of molecular variance (SAMOVA) was performed using SAMOVA version 1.0 51. The number of groups ranged from 2 to 15, and the values of fixation indices were compared among different group numbers with 1,000 permutations. To test the rationality of defined groups, pairwise FST values between defined groups and hierarchical analyses of molecular variance (AMOVA) with 10,000 permutations were executed using Arlequin version 3.543 for both the combined mitochondrial dataset and nuclear data. To confirm our study in the context of divergences within species, analyses on divergence of COI sequence (DNA barcoding marker) were performed using MEGA version 542 with the Kimura-two-parameter (K2P) model.

Gene flow

Four districts were defined based on the zoogeographic regions of China52,53 to infer asymmetric dispersal accurately and present gene flow intuitively. Definitions were as follows (population codes): (1) Southern District (SD): HNA; (2) Central District (CD): JY, LX, TX, SZ, FC, NG, DZ, YA, RY, CHS, HZ, ZHY, ZY, GY, XAW, GUY, XY, DEZ and HX; (3) Northern District (ND): TS, LF, GM, BB, XIX, XUC, DAC, WEX, SYA, XXA, SL and LZ; and (4) Southwestern District (SWD): DL and YUX.

To estimate effective number of migrants entering and leaving each region per generation (θM), the mutation-scaled population size (θ; θ = Neμ, where Ne = effective population size and μ = mutation rate per generation) and the mutation-scaled migration rate (M; M = m/μ, where m = migration rate) were estimated using Bayesian inference implemented in Migrate version 3.6.454. The first run was estimated from FST values, and three subsequent runs were started with θ and M from the previous run to confirm the consistency of results. For each run, one long chain with five independent replicates was contained, other parameters were as follows: long-inc = 20, longsample = 1,000,000, burn-in = 100,000. To increase the efficiency of the MCMC, four heating chains were used with approximately exponential increasing temperatures at 1.0, 1.5, 3.0, and 1,000,000. The final estimates of parameters along with 95% confidence intervals were reported here.

Demographic history

Multiple approaches were explored to investigate the demographic history of N. tenuis. Neutrality analyses of Fu and Li’s F*, Fu and Li’s D* and Tajima’s D for the defined groups and whole populations were calculated using DnaSP version 5.0 program55. Under the assumption of neutrality, the population expansion produced a significantly negative value, whereas processes such as a population subdivision or recent population bottleneck were reflected in significantly positive values. Another method, pairwise mismatch distributions using Arlequin version 3.5 43, was used to infer whether demographic expansions had occurred. Unimodal mismatch distributions represented expanding populations, while multimodal formats revealed populations with relatively constant-size37. In addition, the statistics of the raggedness (rg) index of the observed distribution and the sum of square deviations (SSD) between the observed and the expected mismatch were also calculated using Arlequin version 3.5 43. A small value of the rg index indicated that populations had undergone recent demographic expansions, and a significant value of SSD was an indication of population stability38.

To estimating population expansion through time, Bayesian skyline plots were implemented in BEAST version 1.6.1 56. For the COI gene, a substitution rate of 1.77% per million years57 and the GTR+G model were adopted. The Markov Chain length was set to 300 million generations under an uncorrelated lognormal relaxed clock model, which allowed rate variation among branches. Samples were taken every 10,000 steps. The piecewise-linear skyline model for Bayesian skyline coalescent tree priors was selected and otherwise default parameters were used. The result of Bayesian skyline plot was checked and analyzed using Tracer version 1.4 56 with a burn-in of 10%. For the combined mitochondrial dataset, a slower substitution rate with 1.15% per million years58 and the GTR+I+G model were adopted.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Xun, H. et al. Population genetic structure and post-LGM expansion of the plant bug Nesidiocoris tenuis (Hemiptera: Miridae) in China. Sci. Rep. 6, 26755; doi: 10.1038/srep26755 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Al Fournier (University of Arizona, USA) for his suggestions and comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript. We wish to thank Guangyu Zhao (China Agricultural University), Ping Zhao (Kaili University), Jianxin Cui (Henan Institute of Science and Technology), Mengqing Wang (Institute of Plant Protection, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences) for help in collecting samples. This work was funded by the National Basic Research Program of China (No. 2013CB127600), the National Key Technology R & D Program of the Ministry of Science and Technology (2012BAD19B00) and the Special Fund for Scientific Research (No. 2012FY111100), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos 31372229, 31420103902, 31401991).

Footnotes

Author Contributions H.X., H.L. and W.C. designed and performed the research. H.X., L.Z. and P.J. collected samples. H.X. and P.J. performed the molecular work. H.X., H.L., L.Z., S.W. and F.S. analyzed the data. All authors discussed results and implications. H.X., H.L., S.L., L.Z., S.W. and W.C. wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Arnó J. & Gabarra R. Side effects of selected insecticides on the Tuta absoluta (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) predators Macrolophus pygmaeus and Nesidiocoris tenuis (Hemiptera: Miridae). J. Pest. Sci. 84, 513–520 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Castañé C., Arnó J., Gabarra R. & Alomar O. Plant damage to vegetable crops by zoophytophagous mirid predators. BiolControl 59, 22–29 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Hughes G. E., Bale J. S. & Sterk G. Thermal biology and establishment potential in temperate climates of the predatory mirid Nesidiocoris tenuis. BioControl 54, 785–795 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Hughes G. E., Alford L., Sterk G. & Bale J. S. Thermal activity thresholds of the predatory mirid Nesidiocoris tenuis: implications for its efficacy as a biological control agent. BioControl 55, 493–501 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Cai W. Z. Miridae in Insects of tobacco and related integrated pest management in China (eds Wu J. W. et al.). 121–124 (China Agricultural Science & Technology Press, Beijing, 2003). [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez J. A., Lacasa A., Arnó J., Castañé C. & Alomar O. Life history parameters for Nesidiocoris tenuis (Reuter) (Het., Miridae) under different temperature regimes. J. Appl. Entomol. 133, 125–132 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- David J. P., Huber K., Failloux A. B., Rey D. & Meyran J. C. The role of environment in shaping the genetic diversity of the subalpine mosquito, Aedes rusticus (Diptera, Culicidae). Mol. Ecol. 12, 1951–1961 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slatkin M. Gene flow and the geographic structure of natural populations. Science 236, 787–792 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avise J. C. Phylogeography: retrospect and prospect. J. Biogeogr. 36, 3–15 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt G. M. Genetic consequences of climatic oscillations in the Quaternary. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London, Ser. B 359, 183–195 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollá O., González-Cabrera J. & Urbaneja A. The combined use of Bacillus thuringiensis and Nesidiocoris tenuis against the tomato borer Tuta absoluta. BioControl 56, 883–891 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Clark U. et al. The Last Glacial Maximum. Science 325, 710–714 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert P. D. N., Cywinska A., Ball S. L. & deWaard J. R. Biological Identification through DNA Barcode. P. Roy. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 270, 313–321 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard J. W., Chernoff B. & James A. C. Divergence of mitochondrial DNA is not corroborated by nuclear DNA, morphology, or behavior in Drosophila simulans. Evolution 56, 527–545 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk D. J. & Omland K. E. Species-level paraphyly and polyphyly: frequency, causes, and consequences, with insights from animal mitochondrial DNA. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 34, 397–423 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Zink R. M. & Barrowclough G. F. Mitochondrial DNA under siege in avian phylogeography. Mol. Ecol. 17, 2107–2121 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saied A. et al. Loggerhead turtles nesting in Libya: an important management unit for the Mediterranean stock. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 450, 207–218 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Cooper S. J. B., Harvey M. S., Saint K. M. & Main B. Y. Deep phylogeographic structuring of population of the trapdoor spider Moggridgea tingle (Migidae) from Southwestern Australia: evidence for long-term refugia within refugia. Mol. Ecol. 20, 3219–3236 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoelzer G. A. Inferring phylogenies from mtDNA variation: mitochondrial-genes trees versus nuclear-gene trees revisited. Evolution 51, 622–626 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sefc K. M., Payne R. B. & Sorenson M. D. Genetic continuity of brood-parasitic indigobird species. Mol. Ecol. 14, 1407–1419 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Y. H. et al. Incomplete lineage sorting or secondary admixture: disentangling historical divergence from recent gene flow in the vinous-throated parrotbill (Paradoxornis webbianus). Mol. Ecol. 21, 6117- 6133 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederick H. S. et al. Phylogeography of the magpie-robin species complex (Aves: Turdidae: Copsychus) reveals a Philippine species, an interesting isolating barrier and unusual dispersal patterns in the Indian Ocean and Southeast Asia. J. Biogeogr. 36, 1070–1083 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Chen S. Y. et al. Molecular phylogeography of alpine plant Metagentiana striata (Gentianaceae). J. Syst. Evol. 46, 573–585 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Y. X., Fu C. X. & Comes H. P. Plant molecular phylogeography in China and adjacent regions: tracing the genetic imprints of quaternary climate and environmental change in the world’s most diverse temperate flora. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 59, 225–244 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin D. E. Phylogeographic breaks without geographic barriers to gene flow. Evolution 56, 2383–2394 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo F. J., Bolckmans K. & Belda J. E. Release rate for a pre-plant application of Nesidiocoris tenuis for Bemisia tabaci control in tomato. BioControl 57, 809–817 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Wei S. J. et al. Population genetic structure and approximate Bayesian computation analyses reveal the southern origin and northward dispersal of the oriental fruit moth Grapholita molesta (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) in its native range. Mol. Ecol. 24, 4094–4111 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikac K. M. & Clarke G. M. Tracing the geographic origin of the cosmopolitan parthenogenetic insect pest Liposcelis bostrychophila (Psocoptera: Liposcelididae). Bull. Entomol. Res. 96, 523–530 (2006). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drury D. W., Siniard A. L. & Wade M. J. Genetic differentiation among wild populations of Tribolium castaneum estimated using microsatellite markers. J. Hered. 100, 732–741 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh Y. C. et al. Historical connectivity, contemporary isolation and local adaptation in a widespread but discontinuously distributed species endemic to Taiwan, Rhododendron oldhamii (Ericaceae). Heredity 111, 147–156 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei S. J. et al. Genetic structure and demographic history reveal migration of the diamondback moth Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae) from the southern to northern regions of China. PLoS ONE 8, e59654 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slatkin M. & Hudson R. R. Pairwise comparisons of mitochondrial-DNA sequences in stable and exponentially growing populations. Genetics 129, 555–562 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho S. Y. W., Shapiro B., Phillips M. J., Cooper A. & Drummond A. J. Evidence for time dependency of molecular rate estimates. Syst. Biol. 56, 515–522 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Z., Zhu G. P., Chen P. P., Zhang D. L. & Bu W. J. Molecular data and ecological niche modeling reveal the Pleistocene history of a semi-aquatic bug (Microvelia douglasi douglasi) in East Asia. Mol. Ecol. 23, 3080–3096 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z. et al. Phylogeography of Chinese bamboo partridge, Bambusicola thoracica thoracica (Aves: Galliformes) in south China: inference from mitochondrial DNA control-region sequences. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 56, 273–280 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez J. A. Zoophytophagy in the plantbug Nesidiocoris tenuis. Agric. For. Entomol. 10, 75–80 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Rogers A. R. & Harpending H. Population growth makes waves in the distribution of pairwise genetic differences. Mol. Biol. Evol. 9, 552–569 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dsouli-Aymes N. et al. Global population structure of the stable fly (Stomoxys calcitrans) inferred by mitochondrial and nuclear sequence data. Infect. Genet. Evol. 11, 334–342 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C. et al. Mitochondrial genomes reveal the global phylogeography and dispersal routes of the migratory locust. Mol. Ecol. 21, 4344–4358 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X. et al. The complete mitochondrial genome of the plant bug Nesidiocoris tenuis (Reuter) (Hemiptera: Miridae: Bryocorinae: Dicyphini). Zootaxa 3554, 30–44 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Marcilla A. et al. The ITS-2 of the nuclear rDNA as a molecular marker for populations, species, and phylogenetic relationships in Triatominae (Hemiptera: Reduviidae), vectors of Chagas disease. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 18, 136–42 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K. et al. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2731–2739 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Excoffier L. & Lischer H. E. L. Arlequin suite ver 3.5: a new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 10, 564–567 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L., Connor T. R., Sirén J., Aanensen D. M. & Corander J. Hierarchical and spatially explicit clustering of DNA sequences with BAPS software. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 1224–1228 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandelt H. J., Macaulay V. & Richards M. Median networks: speedy construction and greedy reduction, one simulation, and two case studies from human mtDNA. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 16, 8–28 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huson D. H. & Bryant D. Application of phylogenetic networks in evolutionary studies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23, 254–267 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F. & Huelsenbeck J. P. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19, 1572–1574 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Li H., Wang P., Song F. & Cai W. Z. Comparative mitogenomics of plant bugs (Hemiptera: Miridae): identifying the AGG codon reassignments between serine and lysine. PLoS ONE 9, e101375 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posada D. Selection of models of DNA evolution with jModelTest. Methods Mol. Biol. 537, 93–112 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantel N. The detection of disease clustering and a generalized regression approach. Cancer Res. 27, 209–220 (1967). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupanloup I., Schneider S. & Excoffier L. A simulated annealing approach to define the genetic structure of populations. Mol. Ecol. 11, 2571–2581 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holger K. & Walter J. Comment on “An update of Wallace’s zoogeographic regions of the world”. Science 341, 343 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R. Z. In Zoogeography of China. (Science Press, Beijing, 1999). [Google Scholar]

- Beerli P. & Felsenstein J. Maximum likelihood estimation of a migration matrix and effective population sizes in n subpopulations by using a coalescent approach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 4563 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Librado P. & Rozas J. DnaSP v5: A software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics 25, 1451–1452 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond A. J. & Rambaut A. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol. Biol. 7, 214 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulou A., Anastasiou I. & Vogler A. P. Revisiting the insect mitochondrial molecular clock: the mid-Aegean trench calibration. Mol. Biol. Evol. 27, 1659–1672 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brower A. V. Z. Rapid morphological radiation and convergence among races of the butterfly Heliconius erato inferred from patterns of mitochondrial DNA evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 6491–6495 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.