Abstract

Importance

Some cigarette smokers may not be ready to quit immediately but may be willing to reduce cigarette consumption with the goal of quitting.

Objective

To determine efficacy and safety of varenicline for increasing smoking abstinence rates through smoking reduction.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled, multinational clinical trial with a 24-week treatment period and 28-week follow-up conducted between July 2011 and July 2013 at 61 centers in 10 countries. 1510 cigarette smokers not willing or able to quit smoking within the next month but willing to reduce smoking and make a quit attempt within the next 3 months recruited through advertising.

Interventions

Twenty-four weeks of varenicline titrated to 1 mg twice daily or placebo with reduction target of ≥ 50% in number of cigarettes smoked by 4 weeks and ≥ 75% by 8 weeks and a quit attempt by 12 weeks.

Main Outcome Measures

Primary efficacy endpoint was carbon monoxide (CO)-confirmed self-reported abstinence during weeks 15-24. Secondary outcomes were CO-confirmed self-reported abstinence rate for weeks 21-24 and weeks 21-52.

Results

The varenicline group (N = 760) had significantly higher continuous abstinence rates during weeks 15-24 versus placebo (N = 750) (32.1% vs 6.9%; risk difference (RD) 25.2%; 95% CI 21.4%, 29.0%; relative risk (RR) = 4.6; 95% CI 3.5, 6.1). The varenicline group had significantly higher continuous abstinence rates versus placebo during weeks 21-24 (37.8% vs 12.5%; RD 25.2%; 95 CI 21.1%, 29.4%; RR 3.0; 95% CI 2.4, 3.7) and weeks 21-52 (27.0% vs 9.9%; RD 17.1%; 95% CI 13.3%, 20.9%; RR 2.7; 95% CI 2.1, 3.5). Serious adverse events occurred in 3.7% and 2.2% of the varenicline and placebo groups, respectively (P = 0.07).

Conclusions and Relevance

Among cigarette smokers not willing or able to quit within the next month but willing to reduce cigarette consumption and make a quit attempt in the next 3 months, use of varenicline for 24 weeks compared with placebo significantly increased smoking cessation rates through 6 months of follow up. Varenicline offers a treatment option for smokers whose needs are not addressed by clinical guidelines recommending abrupt smoking cessation.

Trial Registration

www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01370356): https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=NCT01370356&Search=Search

Introduction

Forty percent of cigarette smokers make an average of two quit attempts annually.1 In a telephone survey of 1000 current daily cigarette smokers, 44% reported a preference to quit through reduction in the number of cigarettes smoked, and 68% would consider using a medication to facilitate smoking reduction.2 However, the U.S. Clinical Practice Guidelines recommend that smokers quit abruptly3 even though only 8% of smokers report being ready to quit in the next month.4 Developing effective interventions to achieve tobacco abstinence through gradual reduction could engage more smokers in quitting.5–7

Among cigarette smokers not ready to quit, tobacco reduction incorporating nicotine replacement therapy and behavioral interventions decrease cigarettes smoked and increase future smoking abstinence.6,7 Population-based studies suggest that quitting gradually may be less successful than quitting abruptly.8 However, a systematic review comparing both approaches suggests that reducing cigarettes before the quit date and quitting abruptly without prior reduction yields comparable quit rates.9

Almost all prior studies of pharmacotherapy-aided reduction have examined nicotine replacement therapies. Varenicline is a partial agonist binding with high affinity and selectivity at α4β2 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors.10 Varenicline significantly increases smoking abstinence rates among smokers seeking treatment and quitting abruptly.11,12 Among smokers not trying to stop, varenicline significantly reduces cigarette consumption13 and may increase quit attempts.14

Varenicline may be an effective intervention for smokers who are not willing or able to make an immediate quit attempt but who would be willing to reduce their smoking in preparation for a quit attempt in the future (ie, a “reduce-to-quit” approach). A prior reduce-to-quit study of varenicline was small, provided only 8 weeks of varenicline, and obtained equivocal results.14 We conducted a large, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial providing varenicline for 6 months to evaluate a “reduce-to-quit” approach.

Methods

Study Design

A phase 4, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial was conducted at 61 centers in 10 countries (Australia, Canada, Czech Republic, Egypt, Germany, Japan, Mexico, Taiwan, U.K., and U.S.) between July 2011 and July 2013. Study sites included clinical trial centers, academic centers, and outpatient clinics. Study site training was provided at an investigator meeting with training materials maintained and accessible through a shared website. The study consisted of a 24-week treatment period followed by a 28-week non-treatment follow-up phase. The first 12 weeks of treatment were the reduction phase and the next 12 weeks were the abstinence phase. Written consent forms and study procedures were approved by the institutional review boards or ethics committees of participating institutions. Participants were recruited through advertising. Recruitment advertisements included the following language: “Want to quit smoking but prefer to cut down first?” and “Are you ready to quit but prefer to do it gradually?” and “Want to quit smoking, but hate the idea of going cold turkey?” Enrollment ended when recruitment goals were achieved.

Screening and Eligibility Criteria

Eligible participants were ≥ 18 years of age, smoked an average of ≥ 10 cigarettes/day with no continuous abstinence period > 3 months in the past year, had an exhaled carbon monoxide (CO) > 10 parts per million (ppm), and were not willing or able to quit smoking within the next month but were willing to reduce their smoking and make a quit attempt within the next 3 months.

Exclusion criteria included: a history of suicide attempt or suicidal behavior in previous 2 years as assessed by the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS)15 and the Suicide Behavior Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R)16; physician-assessed severe major depressive or anxiety disorder (lifetime or current) or unstable (ie, medication dose change or exacerbations last 6 months); lifetime diagnosis of psychosis, panic disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, or schizophrenia; alcohol or substance abuse in the last 12 months; a diagnosis of severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; clinically significant cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease in the previous 2 months; taking more than a limited number of doses of varenicline previously; and self-reported inability to abstain from non-cigarette tobacco products, marijuana, or smoking cessation aids (including electronic cigarettes). Females were excluded if pregnant, lactating, or likely to become pregnant and unwilling to use contraception.

Study Procedures

Participants were randomized to varenicline or placebo for 24 weeks of treatment in a 1:1 ratio using a computer-generated block randomization schedule within site. Investigators obtained participant identification numbers and treatment group assignments through a web-based or telephone call-in drug management system. Participants, investigators, and research personnel were blinded to randomization until after the database was locked.

Race/ethnicity was self-reported. At each clinic visit and telephone contact, information was collected on cigarette or other nicotine product use. Exhaled CO measurements were obtained at all clinic visits. Tobacco dependence was assessed with the Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence (FTCD).17 Study design is shown in the eFigure.

Adverse events (AEs) and Food and Drug Administration defined serious AEs (SAEs: AEs resulting in death, hospitalization, or other important medical events) were collected during study visits during the treatment phase and up to 1 month after last treatment dose. A semi-structured interview solicited information about psychiatric AEs. Suicidal ideation and behavior were assessed using the C-SSRS at baseline and all study visits. Participants completed the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-918 to assess the frequency and severity of potential depression-related events every other week during the treatment phase and at clinic visits during the follow-up phase.

Interventions

Participants were asked to reduce baseline smoking rate by ≥ 50% by week 4 with further reduction to 75% from baseline by week 8 with the goal of quitting by week 12. Counseling training was provided at the investigator meeting. Smoking cessation counseling was provided consistent with recommendations of the “Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence” clinical practice guideline.3 Participants received the “Clearing the Air – Quit Smoking Today” booklet. Advice on reduction techniques was provided such as systematically increasing the amount of time between cigarettes and rank-ordering cigarettes from easiest to hardest to give up and giving up the easiest to the hardest.14 Counseling was tailored to the participant’s needs during the reduction, abstinence, and posttreatment phases. Counsellors were urged to be consistent and brief, to focus on problem solving (eg, what triggers the urge to smoke) and skills training (eg, practical actions to avoid smoking), and to highlight successes not failures. Individual counseling lasted ≤ 10 minutes per visit during 18 clinic and 10 telephone visits. The last cigarette was to be smoked prior to midnight on the day prior to the week 12 visit. Participants could reduce their smoking faster and could make a quit attempt prior to week 12. Participants who had not reduced or made a quit attempt by week 12 were encouraged to continue medications and visits and make quit attempts, and participants who relapsed after week 12 were encouraged to make new quit attempts. After the 24-week treatment phase (ie, 12 weeks of reduction and 12 weeks post quit attempt) participants were followed through to week 52 (28-week non-treatment follow-up phase).

Participants started with a recommended varenicline (or matching placebo) dosage of 0.5 mg once daily for 3 days, increasing to 0.5 mg twice daily for days 4 to 7, and then to the maintenance dose of 1 mg twice daily.

Study Endpoints

The primary efficacy endpoint was the CO-confirmed continuous smoking abstinence rate (CAR) during the last 10 weeks of treatment (ie, weeks 15 through 24). A participant was considered abstinent from tobacco if he or she self-reported tobacco abstinence throughout the period and had an exhaled CO ≤ 10 ppm at each visit. In the case of a missing visit, participants were considered abstinent if they were abstinent at the next nonmissed visit and also reported not smoking during the missed visit. A missing CO did not disqualify a participant from meeting the endpoint if they self-reported not smoking Secondary efficacy endpoints were the CARs during weeks 21 through 24 and during weeks 21 through 52. We also calculated the non-prespecified endpoint of the CAR for weeks 15 to 52.

Statistics

The efficacy analysis was based on the intent-to-treat population (all randomized participants). Drop-outs were treated as smokers. A sample size of 1404 randomized participants in a 1:1 ratio (702 in each group) was estimated to provide ≥ 90% power to detect a difference between varenicline and placebo of 10.3% in the primary endpoint of CAR during weeks 15 to 24, assuming a CAR of 17.2% for varenicline and 6.9% for placebo using a 2-group continuity-corrected 2-sided Chi-Square test at the 0.05 significance level.9,19,20

A logistic regression model included treatment effect as the explanatory variable and investigative center as covariate. In addition, an expanded logistic regression model including the treatment-by-center interaction was used to test for the interaction effect. However, as prespecified in the statistical analysis plan, the inferences were based solely on the predesignated logistic regression model including only the main effects of treatment and center, regardless of the significance of the treatment by center interaction (tested at the 0.05 significance level). Relative Risks (RRs) and Risk Differences (RDs) calculated using Proc Freq with option RELRISK and RISKDIFF, respectively, are reported for efficacy endpoints. We conducted a sensitivity analysis for the primary endpoint in which participants who were missing a CO during weeks 15-24 were classified as smokers.

To preserve the type-I family-wise error rate of 0.05, a fixed-sequence procedure was used. The treatment comparison was performed first for weeks 15 through 24, then for weeks 21 through 24, and then for weeks 21 to 52. A post-hoc analysis was conducted in the same manner for the endpoint of the CAR for weeks 15 to 52. Each test used a 0.05 level of significance. We used SAS Version 9.2 for statistical analyses.

Adverse events were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA; version 16.1).21 Adverse events occurring during treatment and up to 30 days after last dose of study drug are reported. All safety analyses included all randomized participants who received any dose of study medication. Our study was not powered to detect significant differences in AEs between groups.

Results

Enrollment and Follow-Up

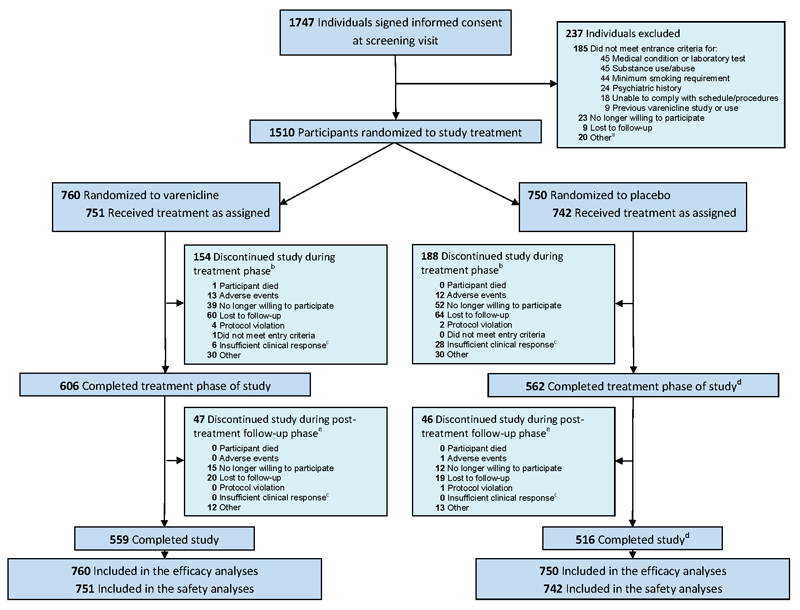

Of 1747 potentially-eligible participants screened, 1510 (86%) were randomly assigned to varenicline (N = 760) and placebo (N = 750). Overall study completion was defined as completion of the week 52 visit and was 73.6% (559/760 participants) in the varenicline group and 68.7% (516/750 participants) in the placebo group (Figure 1). Participants assigned to study groups were similar in demographic and smoking characteristics at baseline (Table 1). Participants who discontinued treatment were encouraged to remain in the study.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram

aParticipants not randomized to study treatment due to reasons classified by the investigators as “other” included reasons such as: did not attend randomization visit; unable to commit to attending study visits; change in work schedule; change in concomitant medications; change in personal circumstances; and unavailability of urine drug screening kits. bTreatment phase was weeks 1 through 24. Includes 9 varenicline participants and 7 placebo participants who withdrew from the study before receiving study medication counted under the respective category for reasons of withdrawal. Note that one placebo participant stayed in the study although did not take any study medication, also see d. Discontinuations from study due to reasons classified by the investigators as “other” included reasons such as: new job or change in work schedule; moved out of area; change in personal or family circumstances; and unwilling or unable to attend visits. cInsufficient clinical response was a prepopulated option chosen by the investigators on the case report forms. dIncludes 1 placebo participant who did not receive any study medication but completed the study. ePost-treatment follow-up phase was weeks 25 through 52. Discontinuations from study due to reasons classified by the investigators as “other” included reasons such as: new job or change in work schedule; moved out of area; change in personal or family circumstances; and unwilling or unable to attend visits.

Table 1. Participant Characteristics.

| Varenicline (N = 760) | Placebo (N = 750) | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | ||

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 425 (55.9) | 426 (56.8) |

| Female | 335 (44.1) | 324 (43.2) |

| Age, years | ||

| Mean (SD) | 44.7 (11.8) | 44.4 (12.0) |

| Range | 19-79 | 18-78 |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 476 (62.6) | 463 (61.7) |

| Black | 36 (4.7) | 47 (6.3) |

| Asian | 175 (23.0) | 177 (23.6) |

| Other | 73 (9.6) | 63 (8.4) |

| Smoking Characteristics | ||

| Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependencea, mean (SD) | 5.5 (2.1) | 5.6 (2.0) |

| Age started smoking, years, mean (SD) | 17.3 (4.3) | 17.3 (4.4) |

| Number of cigarettes per day in past month, mean (SD) | 20.6 (8.5) | 20.8 (8.2) |

| Longest period of abstinence, days | ||

| Since started smokingMedian (25th, 75th percentile) | 30 (3, 240)272 | 21 (2, 180)206 |

| Mean | ||

| In past year | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 1) |

| Median (25th, 75th percentile) | 4 | 3 |

| Mean | ||

| Number of serious quit attempts by any method, n (%) | ||

| Since started smoking | ||

| None | 130 (17.1) | 159 (21.2) |

| One | 191 (25.1) | 188 (25.1) |

| Two | 139 (18.3) | 110 (14.7) |

| Three or more | 300 (39.5) | 293 (39.1) |

Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence measures degree of cigarette dependence with scores ranging from 0 to 10 with higher scores indicating a higher degree of dependence.17

Abbreviations: N = all randomized participants; n = number of participants with the given characteristic; SD = standard deviation.

Smoking Abstinence

The varenicline group (N = 760) had significantly higher continuous abstinence rates during weeks 15-24 versus placebo (N = 750) (32.1% vs 6.9%; risk difference (RD) = 25.2%; 95% CI 21.4%, 29.0%; relative risk (RR) = 4.6; 95% CI 3.5, 6.1) (Table 2). The varenicline group had significantly higher continuous abstinence rates versus placebo during weeks 21-24 (37.8% vs 12.5%; RD = 25.2%; 95% CI 21.1%, 29.4%; RR = 3.0; 95% CI 2.4, 3.7) and weeks 21-52 (27.0% vs 9.9%; RD = 17.1%; 95% CI 13.3%, 20.9%; RR = 2.7; 95% CI 2.1, 3.5). No significant treatment-by-center interaction for the primary endpoint was observed in the logistic regression model.

Table 2. Continuous Abstinence for Weeks 15–24, 21–24, 21–52, and 15–52.

| Continuous Abstinence n (%) | Risk Difference, % (95% CI) versus placebo | Relative Risk (95% CI) versus placebo | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Endpoint | ||||

| Weeks 15–24 | Varenicline (N = 760) | 244 (32.1) | 25.2 (21.4, 29.0) | 4.6 (3.5, 6.1) |

| Placebo (N = 750) | 52 (6.9) | |||

| Secondary Endpoints | ||||

| Weeks 21–24 | Varenicline (N = 760) | 287 (37.8) | 25.2 (21.1, 29.4) | 3.0 (2.4, 3.7) |

| Placebo (N = 750) | 94 (12.5) | |||

| Weeks 21–52 | Varenicline (N = 760) | 205 (27.0) | 17.1 (13.3, 20.9) | 2.7 (2.1, 3.5) |

| Placebo (N = 750) | 74 (9.9) | |||

| Post-hoc Endpoint | ||||

| Weeks 15–52 | Varenicline (N = 760) | 182 (24.0) | 18.0 (14.5, 21.4) |

4.0 (2.9, 5.4) |

| Placebo (N = 750) | 45 (6.0) | |||

Abbreviations: N = all randomized participants; n = number of participants continuously abstinent during time period; CI = confidence interval

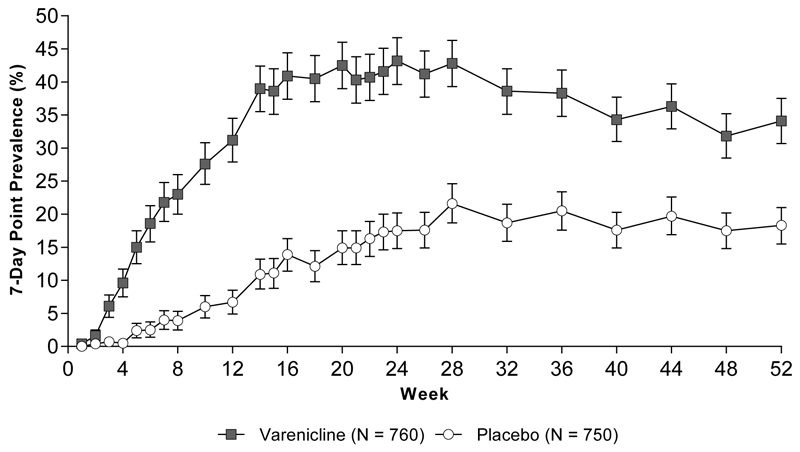

Among the 244 varenicline participants who were counted as abstinent for the primary endpoint, there were 25 with at least one missing CO measurement (including those with missing visits) during weeks 15-24; among the 52 placebo participants who met the primary endpoint there were 4 such participants with missing CO. We conducted a sensitivity analysis with participants who were missing a CO being classified as smokers for the week 15-24 continuous abstinence rate (varenicline 219 [28.8%] vs. placebo 48 [6.4%]). The relative risk for this analysis was 4.5 (95% CI: 3.4, 6.1). This value approximates the value we observed using the pre-specified imputation (RR = 4.6; 95% CI 3.5, 6.1). Among participants meeting the primary endpoint (abstinent during weeks 15-24), the median time from baseline to the beginning of the continuous abstinence period was 50 days for varenicline and 85 days for placebo (P < .0001). The varenicline group also had a significantly higher 7-day point prevalence smoking abstinence rate compared with placebo at weeks 12, 24, and 52 (Figure 2). Varenicline significantly increased the 4-week point prevalence smoking abstinence rate compared with placebo at week 52 (32.8% vs 17.3%; RD = 15.4%; 95% CI 11.1%, 19.7%; RR = 1.9; 95% CI 1.6, 2.3)

Figure 2.

7-Day Point Prevalence Smoking Abstinence and 95% Confidence Intervals

Week 12 RD = 24.5%; 95% CI 20.8%, 28.3%; RR = 4.7; 95% CI 3.5, 6.2. Week 24 RD = 25.7%; 95% CI 21.2%, 30.1%; RR = 2.5; 95% CI 2.1, 3.0. Week 52 RD = 15.8%; 95% CI 11.5%, 20.2%); RR = 1.9, 95% CI 1.6, 2.2.

Abbreviations: RD, risk difference; RR, relative risk; CIs, confidence intervals; N, all randomized participants.

Smoking Reduction (Weeks 1 to 12)

At week 4, 47.1% (358/760) of varenicline-treated participants reduced the number of cigarettes (i.e., average number of cigarettes during days on which smoking occurred over the last week) smoked per day compared with baseline by ≥ 50% or abstained completely compared with 31.1% (233/750) of participants in placebo (RD = 16.0%; 95% CI 11.2%, 20.9%; RR = 1.5; 95% CI 1.3, 1.7). After 8 weeks, 26.3% (200/760) of the varenicline group reduced smoking by ≥ 75% from baseline or abstained compared with 15.1% (113/750) of placebo (RD = 11.3; 95% CI 7.2%, 15.3%; RR = 1.8; 95% CI 1.4, 2.2).

Safety

The percentage of participants with AEs was higher in the varenicline group than in the placebo group (618/751 [82.3%] vs 538/742 [72.5%] participants). AEs with the greatest risk difference between varenicline and placebo (> 2%) were nausea, abnormal dreams, insomnia, constipation, vomiting, and weight gain (Table 3). AE incidence resulting in permanent treatment discontinuation was not significantly different between the 2 groups (63/751 [8.4%] vs 52/742 [7.0%] participants; P = .27). Percentages of participants with SAEs were not significantly different between varenicline and placebo (28/751 [3.7%] vs 16/742 [2.2%] participants; P = .07). During treatment and ≤ 30 days after the last dose, suicidal ideation or behavior was recorded on the C-SSRS in 6/751 (0.8%) varenicline participants and 10/742 (1.4%) placebo participants. Any increases in PHQ-9 depression scores from baseline to any time point during the post-baseline phase occurred in 169/751 (22.5%) participants treated with varenicline compared with 145/742 (19.5%) of placebo participants (P = .16).

Table 3. Adverse Events Occurring During Treatment Plus 30 Days in ≥ 2% of Participants who Received ≥ 1 Dose of Study Drug in Either Treatment Group.

| Adverse Events MedDRA Preferred Term | Varenicline (N = 751) n (%) | Placebo (N = 742) n (%) | Risk Difference (%) (varenicline vs. placebo) | 95% Confidence Interval (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nausea | 209 (27.8) | 67 (9.0) | 18.80 | 14.99, 22.61 |

| Nasopharyngitis | 98 (13.0) | 89 (12.0) | 1.05 | -2.30, 4.41 |

| Abnormal dreams | 86 (11.5) | 43 (5.8) | 5.66 | 2.83, 8.49 |

| Insomnia | 80 (10.7) | 51 (6.9) | 3.78 | 0.92, 6.64 |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 63 (8.4) | 63 (8.5) | -0.10 | -2.92, 2.72 |

| Headache | 62 (8.3) | 54 (7.3) | 0.98 | -1.74, 3.69 |

| Anxiety | 52 (6.9) | 65 (8.8) | -1.84 | -4.56, 0.89 |

| Fatigue | 46 (6.1) | 34 (4.6) | 1.54 | -0.74, 3.82 |

| Irritability | 39 (5.2) | 30 (4.0) | 1.15 | -0.98, 3.28 |

| Constipation | 38 (5.1) | 13 (1.8) | 3.31 | 1.48, 5.14 |

| Increased appetite | 37 (4.9) | 30 (4.0) | 0.88 | -1.22, 2.98 |

| Sleep disorder | 37 (4.9) | 29 (3.9) | 1.02 | -1.06, 3.10 |

| Dizziness | 32 (4.3) | 27 (3.6) | 0.62 | -1.35, 2.60 |

| Vomiting | 31 (4.1) | 13 (1.8) | 2.38 | 0.67, 4.08 |

| Back pain | 28 (3.7) | 29 (3.9) | -0.18 | -2.12, 1.76 |

| Weight increased | 28 (3.7) | 12 (1.6) | 2.11 | 0.48, 3.74 |

| Diarrhea | 27 (3.6) | 23 (3.1) | 0.50 | -1.33, 2.32 |

| Depressed mood | 26 (3.5) | 27 (3.6) | -0.18 | -2.05, 1.70 |

| Depression | 25 (3.3) | 35 (4.7) | -1.39 | -3.38, 0.61 |

| Decreased appetite | 20 (2.7) | 19 (2.6) | 0.10 | -1.52, 1.72 |

| Agitation | 20 (2.7) | 14 (1.9) | 0.78 | -0.74, 2.29 |

| Dyspepsia | 19 (2.5) | 9 (1.2) | 1.32 | -0.05, 2.69 |

| Abdominal pain upper | 18 (2.4) | 7 (0.9) | 1.45 | 0.16, 2.75 |

| Middle insomnia | 17 (2.3) | 11 (1.5) | 0.78 | -0.59, 2.16 |

| Flatulence | 17 (2.3) | 6 (0.8) | 1.46 | 0.21, 2.70 |

| Influenza | 16 (2.1) | 12 (1.6) | 0.51 | -0.86, 1.89 |

| Dry mouth | 16 (2.1) | 11 (1.5) | 0.65 | -0.70, 2.00 |

| Abdominal distention | 16 (2.1) | 8 (1.1) | 1.05 | -0.22, 2.32 |

| Somnolence | 15 (2.0) | 10 (1.3) | 0.65 | -0.65, 1.95 |

| Initial insomnia | 15 (2.0) | 9 (1.2) | 0.78 | -0.49, 2.06 |

| Cough | 14 (1.9) | 23 (3.1) | -1.24 | -2.81, 0.34 |

| Disturbance in attention | 13 (1.7) | 17 (2.3) | -0.56 | -1.98, 0.86 |

| Sinusitis | 12 (1.6) | 16 (2.2) | -0.56 | -1.94, 0.82 |

| Bronchitis | 10 (1.3) | 23 (3.1) | -1.77 | -3.26, -0.28 |

Abbreviations: MedDRA = Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities; N = number of participants who received ≥1 dose of study drug, including partial doses; n = number of participants reporting AEs.

All participants had been randomized and had received at least 1 dose (including partial doses) of study drug; and includes all participants who had experienced an adverse event from the date of first dose of study drug and up to 30 days after the last dose of study drug. Adverse events were recorded in the clinical report form (volunteered and observed adverse events) and, in addition, neuropsychiatric adverse events were solicited in a semi-structured neuropsychiatric adverse event interview. Adverse events were coded according to MedDRA; v16.1 (http://www.meddra.org/).

Participants were counted once per row but could be counted in multiple rows.

Discussion

Among cigarette smokers not willing or able to quit smoking in the next month but willing to reduce with the goal of quitting in the next 3 months, varenicline produced a statistically and clinically significant increase in the CARs at the end of treatment and after 28 weeks posttreatment. Varenicline produced greater smoking reduction than placebo prior to quitting. Varenicline was not associated with significant increases in treatment discontinuations due to AEs.

Smokers enrolled in the current study were not ready to quit in the next month, and overall smoking abstinence rates would have been expected to be low. Although they were low in the placebo group, varenicline increased the rates of achieving abstinence such that the absolute abstinence rates were similar to those observed in studies of varenicline in smokers motivated to quit after one week of treatment.11,12

The mechanism of varenicline action as an aid to gradual cessation could relate to a reduction in cigarette craving or blockade of the reinforcing action of nicotine through partial agonist activity at the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors.10 Ancillary effects from varenicline may exist with respect to confidence in ability to quit. However, this should have been controlled through study blinding and any effect via this route is likely to be small given limited evidence that confidence plays a causal role in sustaining quitting attempts.22

Adverse events caused by varenicline were similar to previous observations. In the present study, varenicline was associated with an increased rate of constipation and weight gain. However, both are established effects of smoking cessation,23,24 and it is possible that the greater incidence of abstinence with varenicline and not the direct effect of varenicline was the cause. The incidence of bronchitis was lower in those treated with varenicline, an effect which is possibly mediated by an increased rate of smoking cessation.25 Varenicline did not increase the risk of suicidal ideation or behavior or other psychiatric AEs.

Major strengths of this study include the randomized design, large sample size, large treatment effect, and convergent validity of the findings across multiple outcomes and measures. One limitation of this study relates to the exclusion of potential participants if they had severe psychiatric, pulmonary, cardiovascular, or cerebrovascular disease. As a result, the generalizability of this treatment approach to a broader population of smokers who need to quit smoking but may want to achieve it through reduction is unknown. In addition, participants in the current study were provided with significant support with counseling from trained staff occurring during 18 clinic and 10 telephone visits. Because of this, the observed abstinence rates with varenicline in actual clinical practice might be expected to be less than that observed in the current trial. We did not test whether varenicline would be more effective for reduce-to-quit than other tobacco treatments such as nicotine replacement therapy.

Uncertainty remains as to the prevalence of smokers in the general population who meet the definition of smokers enrolled in this study. In a cross-sectional study collecting data via telephone or face-to-face interview with daily smokers responding to the Current Population Survey, the prevalence of contemplators (i.e., interested in quitting smoking in next 6 months but not in the next 30 days) was 33.2%.26 We were not attempting to fit smokers into a specific stage of change based upon the transtheoretical model.27 Instead, our approach aimed to reduce barriers to engaging in the quitting process by allowing and facilitating smoking reduction in a precessation phase.28 Our sample most closely resembles the 33% of smokers who want to quit sometime between 1 and 6 months in the future. The approach used in this study would be expected to be of interest to 14 million of the 42 million current smokers.

The U.S. Public Health Service3 and other guidelines recommend smokers set a quit date in the near future and quit abruptly. However, many smokers may be unwilling to commit to a quit date at a clinic visit. Since most clinicians are likely to see smokers at times when a quit date in the next month is not planned, the current study indicates that prescription of varenicline with a recommendation to reduce the number of cigarettes smoked per day with the eventual goal of quitting could be a useful therapeutic option for this population of smokers. The approach of reduction with the goal of quitting increases the options for a clinician caring for a smoker.

Conclusion

This study provides evidence that varenicline can increase smoking abstinence rates among smokers electing to reduce their smoking rate over 3 months while working toward the goal of smoking abstinence. This approach could engage a substantial number of additional smokers in the quitting process. Treatment with varenicline in this population using this approach is effective and safe.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all investigators and study site personnel involved in the study.

Editorial support in the form of developing tables and figures; editing, proofing, and formatting the text; collating review comments; and preparing the manuscript for submission was provided by Abegale Templar, PhD, of Engage Scientific, Horsham, UK and was funded by Pfizer Inc.

Funding/Support: This study was funded by Pfizer Inc (www.clinical trials.gov identifier: NCT01370356).

Footnotes

Article Information

Author Contributions: Drs. Ebbert and Yu had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Dr. Yu of Pfizer Inc was responsible for and conducted data analysis.

Study concept and design: Dr. Hughes, Dr. West, Dr. Rennard, Dr. Russ, Ms. Treadow, Dr. Yu, Dr. Park

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Dr. Ebbert, Dr. Hughes, Dr. West, Dr. Rennard, Dr. Russ, Dr. McRae, Ms. Treadow, Dr. Yu, Dr. Dutro, Dr. Park

Drafting of the manuscript: Dr. Ebbert, Dr. Hughes, Dr. West, Dr. Rennard, and Dr. Russ

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Dr. Ebbert, Dr. Hughes, Dr. West, Dr. Rennard, Dr. Russ, Dr. McRae, Ms. Treadow, Dr. Yu, Dr. Dutro, Dr. Park

Final approval of the version to be published: Dr. Ebbert, Dr. Hughes, Dr. West, Dr. Rennard, Dr. Russ, Dr. McRae, Ms. Treadow, Dr. Yu, Dr. Dutro, Dr. Park

Accountability: Dr. Ebbert, Dr. Hughes, Dr. West, Dr. Rennard, Dr. Russ, Dr. McRae, Ms. Treadow, Dr. Yu, Dr. Dutro, Dr. Park

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Dr. Ebbert reports grants from Pfizer, Orexigen and JHP Pharmaceuticals and personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline during the conduct of the study. Dr. Hughes reports personal fees from Alere/Free and Clear, Equinox, GlaxoSmithKline, Healthwise, Pfizer, Embera, Selecta, DLA Piper, Dorrffermeyer, Nicoventures, Pro Ed, Publicis, Cicatelli, and non-financial support from Swedish Match, outside the submitted work. Dr. West reports grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, and Johnson & Johnson outside the submitted work. Dr. Rennard reports personal fees from Almirall, Novartis, Nycomed, Pfizer, A2B Bio, Dalichi Sankyo, APT Pharma/Britnall, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Decision Resource, Dunn Group, Easton Associates, Gerson, GlaxoSmithKline, Roche, Theravance, Almirall, CSL Behring, MedImmune, Novartis, Pearl, Takeda, Forest, CME Incite, Novis, PriMed, Takeda, grants from AstraZeneca, Novartis, Otsuka, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, and Johnson & Johnson, outside the submitted work. Dr. Russ, Dr. McRae, Ms. Treadow, Dr. Yu, Dr. Dutro, and Dr. Park are employees and stock holders of Pfizer Inc.

Role of the Sponsor: Pfizer Inc was involved in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

References

- 1.Borland R, Partos TR, Yong HH, Cummings KM, Hyland A. How much unsuccessful quitting activity is going on among adult smokers? Data from the International Tobacco Control Four Country cohort survey. Addiction. 2012 Mar;107(3):673–682. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03685.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shiffman S, Hughes JR, Ferguson SG, Pillitteri JL, Gitchell JG, Burton SL. Smokers' interest in using nicotine replacement to aid smoking reduction. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007 Nov;9(11):1177–1182. doi: 10.1080/14622200701648441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. [Accessed December 31, 2014];Clinical Practice Guideline. 2008 http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/tobacco/index.html.

- 4.Boyle P, Gandini S, Robertson C, et al. Characteristics of smokers’ attitudes towards stopping. Eur J Public Health. 2000;10(3 Supplement):5–14. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asfar T, Ebbert JO, Klesges RC, Relyea GE. Do smoking reduction interventions promote cessation in smokers not ready to quit? Addict Behav. 2011 Jul;36(7):764–768. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang D, Connock M, Barton P, Fry-Smith A, Aveyard P, Moore D. 'Cut down to quit' with nicotine replacement therapies in smoking cessation: a systematic review of effectiveness and economic analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2008 Feb;12(2):iii–iv. ix–xi, 1–135. doi: 10.3310/hta12020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore D, Aveyard P, Connock M, Wang D, Fry-Smith A, Barton P. Effectiveness and safety of nicotine replacement therapy assisted reduction to stop smoking: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009;338:b1024. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheong Y, Yong HH, Borland R. Does how you quit affect success? A comparison between abrupt and gradual methods using data from the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007 Aug;9(8):801–810. doi: 10.1080/14622200701484961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindson N, Aveyard P, Hughes JR. Reduction versus abrupt cessation in smokers who want to quit. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(3):CD008033. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008033.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coe JW, Brooks PR, Vetelino MG, et al. Varenicline: an alpha4beta2 nicotinic receptor partial agonist for smoking cessation. J Med Chem. 2005 May 19;48(10):3474–3477. doi: 10.1021/jm050069n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonzales D, Rennard SI, Nides M, et al. Varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs sustained-release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006 Jul 5;296(1):47–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jorenby DE, Hays JT, Rigotti NA, et al. Efficacy of varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs placebo or sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006 Jul 5;296(1):56–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ashare RL, Tang KZ, Mesaros AC, Blair IA, Leone F, Strasser AA. Effects of 21 days of varenicline versus placebo on smoking behaviors and urges among non-treatment seeking smokers. J Psychopharmacol (Oxf) 2012 Oct;26(10):1383–1390. doi: 10.1177/0269881112449397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hughes JR, Rennard SI, Fingar JR, Talbot SK, Callas PW, Fagerstrom KO. Efficacy of varenicline to prompt quit attempts in smokers not currently trying to quit: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011 Oct;13(10):955–964. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Posner K. Suicidality issues in clinical trials: Columbia Suicide Adverse Event Identification in FDA Safety Analyses. 2007 http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/07/slides/2007-4306s1-01-CU-Posner.ppt.

- 16.Osman A, Bagge CL, Gutierrez PM, Konick LC, Kopper BA, Barrios FX. The Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R): validation with clinical and nonclinical samples. Assessment. 2001 Dec;8(4):443–454. doi: 10.1177/107319110100800409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991 Sep;86(9):1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001 Sep;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hatsukami DK, Rennard S, Patel MK, et al. Effects of sustained-release bupropion among persons interested in reducing but not quitting smoking. Am J Med. 2004 Feb 1;116(3):151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cahill K, Stead LF, Lancaster T. Nicotine receptor partial agonists for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(3):CD006103. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006103.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) [Accessed December 31, 2014]; http://www.meddra.org/.

- 22.Vangeli E, Stapleton J, Smit ES, Borland R, West R. Predictors of attempts to stop smoking and their success in adult general population samples: a systematic review. Addiction. 2011 Dec;106(12):2110–2121. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hajek P, Gillison F, McRobbie H. Stopping smoking can cause constipation. Addiction. 2003 Nov;98(11):1563–1567. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aubin HJ, Farley A, Lycett D, Lahmek P, Aveyard P. Weight gain in smokers after quitting cigarettes: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;345:e4439. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e4439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Willemse BW, Postma DS, Timens W, ten Hacken NH. The impact of smoking cessation on respiratory symptoms, lung function, airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammation. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:464–476. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00012704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wewers ME, Stillman FA, Hartman AM, Shopland DR. Distribution of daily smokers by stage of change: Current Population Survey results. Prev Med. 2003 Jun;36(6):710–720. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prochaska J, DiClemente C. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51(3):390–395. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baker TB, Mermelstein R, Collins LM, et al. New methods for tobacco dependence treatment research. Ann Behav Med. 2011 Apr;41(2):192–207. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9252-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.