Abstract

Aim

To evaluate the inter-rater reliability of measuring structural changes in the tendon of patients, clinically diagnosed with supraspinatus tendinopathy (cases) and healthy participants (controls), on ultrasound (US) images captured by standardised procedures.

Methods

A total of 40 participants (24 patients) were included for assessing inter-rater reliability of measurements of fibrillar disruption, neovascularity, as well as the number and total length of calcifications and tendon thickness. Linear weighted κ, intraclass correlation (ICC), SEM, limits of agreement (LOA) and minimal detectable change (MDC) were used to evaluate reliability.

Results

‘Moderate—almost perfect’ κ was found for grading fibrillar disruption, neovascularity and number of calcifications (k 0.60–0.96). For total length of calcifications and tendon thickness, ICC was ‘excellent’ (0.85–0.90), with SEM(Agreement) ranging from 0.63 to 2.94 mm and MDC(group) ranging from 0.28 to 1.29 mm. In general, SEM, LOA and MDC showed larger variation for calcifications than for tendon thickness.

Conclusions

Inter-rater reliability was moderate to almost perfect when a standardised procedure was applied for measuring structural changes on captured US images and movie sequences of relevance for patients with supraspinatus tendinopathy. Future studies should test intra-rater and inter-rater reliability of the method in vivo for use in clinical practice, in addition to validation against a gold standard, such as MRI.

Trial registration number

NCT01984203; Pre-results.

Keywords: Reliability, Tendinopathy, ULTRASONOGRAPHY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A standardised procedure for US capturing and measuring structural changes of the supraspinatus tendon is presented.

A specific procedure for grading and interpreting tendinopathy-related changes is presented.

Grading and measurement can be performed reliably.

Performance of the method in vivo is warranted to validate the method in clinical practice.

Introduction

Rotator cuff (RC) tendinopathy can be considered a continuum of pathology, and tailored rehabilitation according to the stage in this continuum is recommended.1 2 Anamnesis and special orthopaedic tests are often used when diagnosing RC tendinopathy, but these tests often lack high specificity and sensitivity, making diagnosis uncertain,3 thus challenging precise and targeted treatment.

Grey-scale (GS) ultrasound (US) and Power Doppler (PD) visualisation of RC tendons may be helpful to detect signs of tendinopathy, such as hypoechoic areas, fibrillar disruption (FD), neovascularisation (NV), calcifications (CAs) embedded in the tendon or oedema, and confirm the ‘a priori’ hypothesis of RC tendinopathy, provided satisfactory clinimetric properties of the US method.4 5

However, US is an operator-dependent technique and requires thorough training and experience in performance and assessment before precise diagnoses can be made, especially in relation to more subtle changes as often seen within tendinopathy.6 Poor to fair reliability has previously been found when comparing US diagnoses made by novel and experienced clinicians.7–9 Further, when grading subtle structural tendon changes, especially hypoechoic areas, only fair and therefore unsatisfactory reliability has been found, even among experienced clinicians.6 8 10–12

Standardised procedures for capturing and assessing US are known to increase reliability of US-based diagnoses.6 Previously, assessment of tendinopathy were found reliable, in patients with tendinopathy in the elbow, ankle or knee, when using standardised procedures for measuring GS and PD.4 11

For the shoulder, however, there is a lack of clinically relevant, standardised and reliable methods for assessing tendinopathy. Since US is highly influenced by clinician experience and technique, both standardised US procedures for image and movie capturing and standardised procedures for assessment of structural changes in relation to tendinopathy need to be defined.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the inter-rater reliability of measuring and grading structural changes in the tendons of patients clinically diagnosed with supraspinatus tendinopathy (cases) and healthy participants (controls), on images and movies captured through standardised US procedures.

Materials and methods

Study design

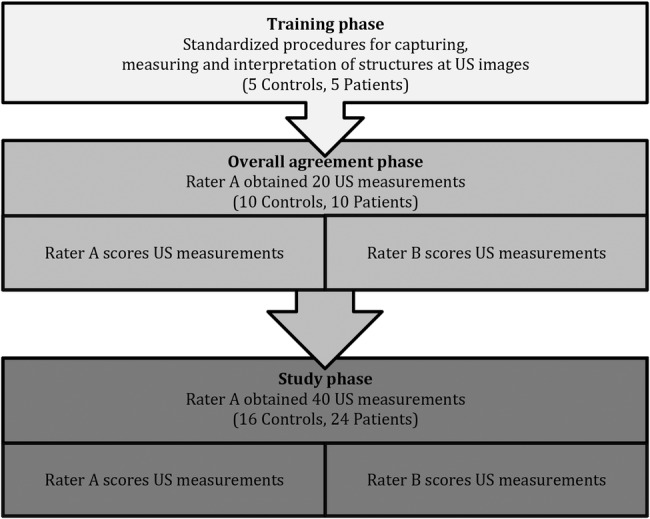

The study followed the protocol for diagnostic procedures in reproducibility studies.13 This protocol includes a three-phase study design consisting of (1) training, (2) an overall agreement and (3) a study phase (the actual reliability study; figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the training, overall agreement and study phase. US, ultrasound.

The phases constitute a methodological model for optimising procedures, and aim at eliminating clinician subjectivity as much as possible. The aim of the training phase is to ensure that raters have sufficient competence and experience in performing the procedures. The overall agreement phase is an extended training phase and ensures that gross systematic bias between raters is minimised, and requires at least 80% agreement between raters before proceeding to phase 3. The study phase is the final evaluation of reliability of the developed procedures.13

Inter-rater reliability (phase 3) between two raters (raters A and B) was tested on measuring and grading structural changes relevant to tendinopathy on US-captured images and movies. Rater A (KGI; physiotherapist) had 1 year of clinical musculoskeletal US experience, and rater B (JH; radiologist) had more than 15 years of clinical musculoskeletal US experience.

US image capturing and measurement

On the basis of the literature,4 10 11 14–17 consensus was made on definitions of relevant potential pathological structural changes related to tendinopathy, including (1) FD, (2) NV, (3) CA and (4) tendon thickness (TT). Hereafter, a standardised protocol for US capturing was developed, consisting of three static images (GS), three dynamic movie sequences (GS) and one Doppler movie sequence (table 1).

Table 1.

Description of US procedures for capturing image and movie sequences of FD, NV, CAs and TT

|

(1) FD: FD was defined as a clear collagen fascicle discontinuity or irregularity of fibrils in an otherwise regular parallel structuring of fibres in the tendon. A GS picture in the longitudinal axis of the supraspinatus was taken at the sight where FD was most apparent (FD picture). The FD static image was used for classifying the presence of FD. A GS PA dynamic movie sequence (PA movie) in the longitudinal plane of the supraspinatus tendon was captured by moving the transducer slowly in the PA direction. Further, a CC transversal GS dynamic movie sequence (CC movie) of the supraspinatus tendon was recorded by moving the transducer slowly in the CC direction. The static image and the movie sequence recordings were used as confirmation and assistance in assessing the grade of structural changes, and to secure identification of potential ambiguous GS features, such as anisotropy (erroneous signal caused when the transducer is angled obliquely to the tendon). FD was classified in relation to tendon thickness as: 0=normal, 1=mild, 2=moderate, 3=severe, 4=partial rupture (table 2). |

Grade 2 FD |

|

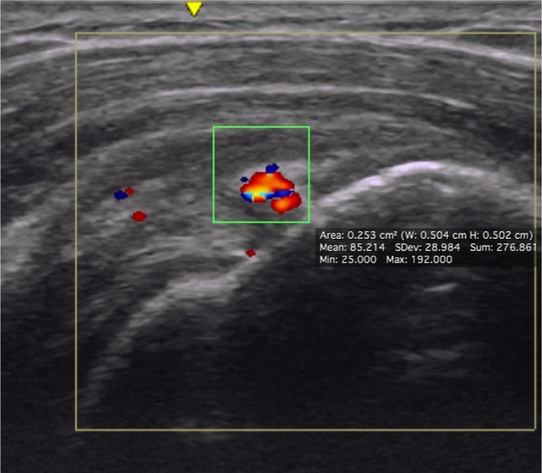

(2) NV: NV was defined as a visualised PD signal with minimal artefactual noise. The supraspinatus tendon was evaluated for presence of NV by moving the transducer slowly in the PA direction, with the PD feature activated. In case NV was present, a 10 s dynamic movie sequence was recorded at the point with most NV signal (PD movie). When grading NV from the PD movie sequence, a static image of the location with the most visible NV was captured from the PD movie. A ROI (5×5 mm) was placed around the NV and used for grading NV. In participants with no NV, a movie sequence was recorded at a random location in the tendon to verify absence of NV. NV was classified in relation to ROI as 0=normal, 1=mild, 2=moderate, 3=severe, 4=extreme (table 2). |

Grade 2 NV |

|

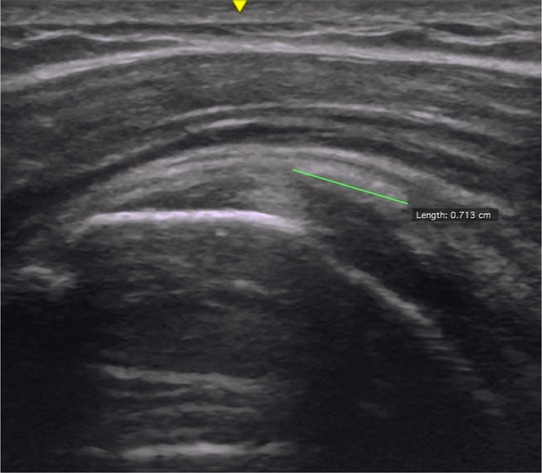

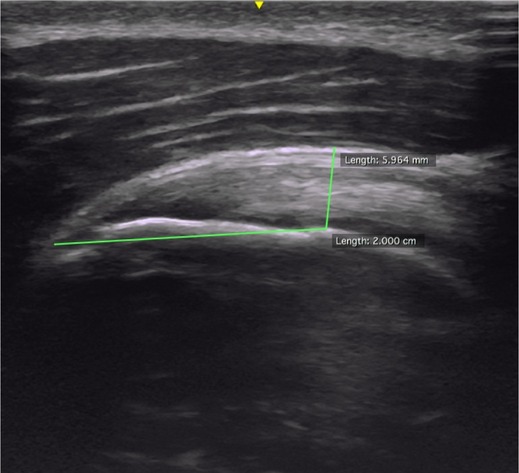

(3) CA: CA was defined as distinct white borders, imbedded in the length of the tendon, often with ‘shadows’ underneath. The PA movie was used to identify the number of CA in the tendon and to measure the length of each CA in the longitudinal axis of the supraspinatus. The length was measured between the most medial and lateral aspects of the distinct white boarder (in mm). The CC movie was used as confirmation and assistance in identifying CA. CA was counted and measured (mm). To obtain the total length of CA, the individual CA lengths were added up to one total per participant. |

CA length measure |

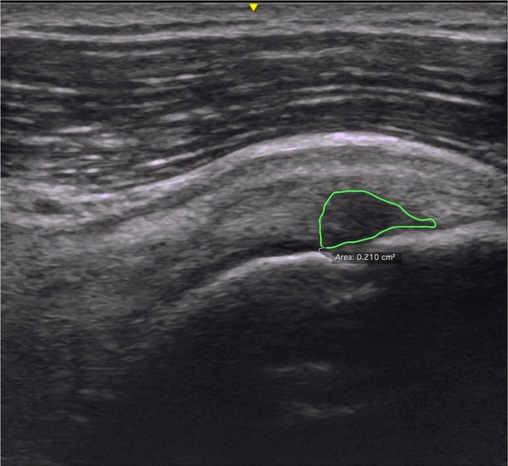

|

(4) TT: TT was defined as the height, from the humeral head, at a point 20 mm from the supraspinatus tendon-snip (tendon insertion) in the longitudinal axis of the tendon, to the most superficial part of the tendon. In practice, an image was captured at a fixed point just laterally from the anterior-lateral corner of the acromion in the longitudinal plane of the supraspinatus. When measuring TT, a mark was placed 20 mm cranial from the supraspinatus tendon-snip (tendon insertion), on the edge of the cartilage of the humeral head. From that mark, the perpendicular thickness of the tendon was recorded.18 The TT picture was recorded bilaterally. TT was measured in mm. |

TT measure |

CA, calcification; CC, caudal–cranial; FD, fibrillar disruption; GS, grey-scale; NV, neovascularity; PA, posterior–anterior; PD, Power Doppler; ROI, Region of interest; TT, tendon thickness.

Second, on the basis of previous scales used to measure structural changes in tendinopathy at the elbow,4 16 two ordinal grading scales for FD and NV were adjusted for use in the shoulder.19 The scales ranged from 0 to 4 (FD: 0=normal tendon; 4=partial rupture, corresponding to disruption of the fibres in the full thickness of the tendon; NV (0=normal, including no signal; 4=extreme, including Doppler activity in more than 50% of the region of interest, ROI; table 2; see online supplementary appendix).

Table 2.

Grading scales with definitions for FD and NV

| Grade | FD | NV |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Normal | Normal (no signal) |

| 1 | Mild (involving under 25% of the height of the tendon) | Mild (single small signal in the ROI) |

| 2 | Moderate (involving 25–50% of the height of the tendon) | Moderate (Doppler activity in <25% of the ROI) |

| 3 | Severe (involving more than 50% of the height of the tendon) | Severe (Doppler activity in 25–50% of the ROI) |

| 4 | Partial rupture (disruption of the fibres in the full thickness of the tendon) | Extreme (Doppler activity in more than 50% of the ROI) |

FD, fibrillar disruption; NV, neovascularity; ROI, region of interest.

bmjopen-2016-011746supp.pdf (2.8MB, pdf)

CA was analysed as number of CAs and total length (in mm), while TT was measured in mm.18

Rater A performed capture of all US images and movie sequences with the participant seated, the shoulder internally rotated with the dorsal side of the hand placed on the sacrum, and the elbow flexed and directed laterally, to optimise visualisation of the supraspinatus tendon.20

A GE LOGIQ e B12 (GE Healthcare) with a 5.0–13.0 MHz linear transducer was used for image capturing. All US scannings were standardised and performed for GS imaging at 13.0 MHz and 56% gain, while PD scanning was performed with a pulse repetition frequency of 0.41 kHz and gain at 56%. Manufacturer recommendations for musculoskeletal imaging of the shoulder were preset for the remaining parameters.

Captured images and movie sequences were stored with unique identifier labels on an external hard disk. Measurement of captured images and movie sequences was performed in ‘OsiriX V.5.8.2 32-bit’ (rater A) and RadiAnt DICOM viewer V.1.9.16 (32 bit; rater B).

In the overall agreement and study phase, raters were blinded to each other's results and the participant status (case/control), and images and movies were stored for at least 21 days before measurements to secure blinding of rater A.

Training and overall agreement phases

In the training phase, raters A and B practised the US procedures for capturing, measuring and grading the captured images and movies on 10 participants (cases and controls). Overall agreement phase was performed on 20 participants (10 cases and 10 controls), and the overall agreement of at least 80% on each parameter (present/not present for dichotomised variables, CA, NV, FD; no significant (p>0.05) rater difference for continuous variables, TT, CA) was obtained before the actual reliability study.

Study phase 3 (actual reliability study)

Participants

General inclusion criteria were: 18–65 years old; the ability to understand spoken and written Danish; no prior shoulder surgery/dislocation; no sensory or motor deficits in the neck/arm; no suspected competing diagnoses (rheumatoid arthritis, cancer, neurological disorders, fibromyalgia, psychiatric illness).

Inclusion criteria for cases were: clinical diagnosis of RC tendinopathy with current shoulder symptoms lasting for at least 3 months prior to inclusion; pain located in the proximal lateral aspect of the upper arm (C5 dermatome) aggravated by shoulder abduction; positive ‘full can test’ and/or ‘Jobe's test’, and/or pain at ‘resisted external rotation test’; and positive ‘Hawkins-Kennedy test’ and/or ‘Neer's test’; and US verification of at least one of the following characteristics: FD, NV, CA (the involved side), or side difference (increased/decreased) TT of the supraspinatus tendon.21

Exclusion criteria for cases were pain (during rest) rated above 40 mm (visual analogue pain scale, range 0–100 mm); bilateral shoulder pain; <90° of active elevation of the arm; full thickness rupture in the supraspinatus tendon (verified by US); CA above 5 mm in the vertical distance (X-ray); corticosteroid injection within the latest 6 weeks; humerus fracture (X-ray); diagnoses of glenohumeral osteoarthritis; frozen shoulder; clinically suspected labrum lesion; symptomatic osteoarthritis in the acromioclavicular joint; or symptoms from the cervical spine.21

Inclusion criteria for controls were no shoulder discomfort within the latest 3 months and negative clinical shoulder tests.

Cases were consecutively recruited from specialised shoulder units at three hospitals in Denmark as part of a randomised controlled trial.21 Controls were recruited by advertisement among staff from The Department of Sports Science and Clinical Biomechanics, University of Southern Denmark, and the Rehabilitation Department, Lillebaelt hospital—Vejle hospital.

Informed consent was obtained from participants before inclusion.

Statistics

Linear weighted Cohen's κ (LWk) was used to calculate inter-rater reliability with 95% CIs for the ordinal variables (FD, number of CA and NV). First, a linear weighing (LWk V.1) was applied, corresponding to the formula: 1−|i−j|/(k−1), where i and j are the number of rows and columns, and k is the maximum number of possible ratings.22 Second, the same weighing was used (LWk V.2), but with the restriction that disagreement between grades 0 and >0 was weighted as 0, to account for the ability to differentiate between healthy and non-healthy.

The κ was interpreted as ≤0.00=poor; 0.01 to 0.20=slight; 0.21 to 0.40=fair; 0.41 to 0.60=moderate; 0.61 to 0.80=substantial and 0.81 to 1.00=almost perfect.23

For the continuous variables (TT, total length of CA), intraclass correlation (ICC; 3.1) was calculated as a measure of reliability. ICC was interpreted as <0.40=poor, 0.40 to 0.75=fair to good and >0.75=excellent reliability.24 Bland-Altman plots with 95% limits of agreement (LOA) were calculated as a measure of absolute agreement for TT (right and left) and total length of CA, and between-rater difference was tested by a paired t-test. Funnel effects and systematic bias were assessed visually and from Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r). SEM was calculated as SEM(Agreement)25 to extrapolate results to the general population of potential raters, and minimal detectable change (MDC) was calculated at individual (MDCIndividual) and group (MDCgroup) levels.26 Unpaired t-test was calculated for defining a potential cut-point of TT between cases and controls.

For the study phase, a sample size of 40 participants was applied, as previously recommended for reliability studies.13

Data were analysed in Stata/IC V.14 (2015, Statacorp, College Station, Texas, USA). p Values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

There were no differences in demographics between cases and controls, except for pain and discomfort, as expected, due to the study design (table 3).

Table 3.

Demographics (study phase; n=40))

| Cases (n=24) | Controls (n=16) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (woman/men) | 10/14 | 10/6 | 0.20 |

| Mean age (years) (SD) | 47.0 (9.3) | 39.8 (15.4) | 0.13 |

| Height (cm) (SD) | 176.2 (10.75) | 171.9 (7.8) | 0.18 |

| Weight (kg) (SD) | 79.7 (18.1) | 71.6 (19.3) | 0.10 |

| BMI | 25.4 (3.6) | 24.1 (5.7) | 0.12 |

| Dominant arm right | 21/24 | 14/16 | 0.30 |

| Duration of pain (months) (SD) | 24.3 (34.9) | 0 (0) | <0.01 |

| VAS rest (0–100) (SD) | 6.5 (7.4) | 0 (0) | <0.01 |

| VAS activity (0–100) (SD) | 36.8 (16.4) | 0 (0) | <0.01 |

| VAS sleep (0–100) (SD) | 30.0 (23.6) | 0 (0) | <0.01 |

| VAS maximum (0–100) (SD) | 70.5 (14.1) | 0 (0) | <0.01 |

| DASH (0–100) (SD) | 23.6 (11.1) | 1.0 (2.29) | <0.01 |

Bod typeface represents p values less then 0.001.

BMI, body mass index; DASH, Disability of Arm, Shoulder and Hand questionnaire; VAS, visual analogue scale.

Total agreement ranged from 83% to 99%, LWk V.1 for FD, NV and CA ranged from 0.60 to 0.96, and κ with constraints (LWk V.2) varied from 0.51 to 0.98, representing reliability of ‘moderate—almost perfect’ (table 4).

Table 4.

Inter-rater reliability of grading presence of FD, NV and number of CAs (study phase; n=40)

| Ordinal scale | Total agreement (LWκ V.1) (%) | LWκ (V.1) (95% CI) |

LWκ (V.2) (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| FD | 83.3 | 0.60 (0.40 to 0.79) | 0.51 (0.30 to 0.72) |

| CA | 93.8 | 0.72 (0.59 to 0.85) | 0.75 (0.56 to 0.89) |

| NV | 99.2 | 0.96 (0.85 to 1.0) | 0.98 (0.93 to 1.0) |

LWκ (V.1): no cut-point applied in the weights schedule.

LWκ (V.2): cut-point applied in weights when raters A and B disagree between grades 0 and >0.

CA, calcification; FD, fibrillar disruption; LWκ, linear weighted κ; NV, neovascularity.

For total length of CA and TT, ICC ranged from 0.85 to 0.90 (excellent), with SEM(Agreement) ranging from 0.63 to 2.94 mm, MDC(group) from 0.28 to 1.29 mm and MDC(individual) from 1.75 to 8.15 mm (table 5).

Table 5.

Inter-rater reliability of TT and total length of CA (study phase; n=40)

| Continuous scale | Rater A (mm (SD)) | Rater B (mm (SD)) | Difference (mm (SD)) | P | LOA (mm) | SEM (mm) | MDC(G) (mm) | MDC(I) (mm) | ICC (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TT right | 7.18 (1.08) | 7.29 (1.09) | −0.11 (0.56) | 0.22 | −1.20; 0.98 | 0.63 | 0.28 (3.87%) | 1.75 (24.2%) | 0.87 (0.76 to 0.93) |

| TT left | 6.96 (1.26) | 7.11 (0.98) | −0.15 (0.49) | 0.07 | −1.11; 0.81 | 0.74 | 0.33 (4.69%) | 2.05 (29.1%) | 0.90 (0.82 to 0.95) |

| Total length CA | 2.81 (4.95) | 2.28 (4.16) | 0.53 (2.45) | 0.18 | −4.27; 5.34 | 2.94 | 1.29 (72.01%) | 8.15 (320.2%) | 0.85 (0.74 to 0.92) |

CA, calcification; ICC, intraclass correlation; LOA, limits of agreement; MDC(G), minimal detectable change (group level); MDC(I), minimal detectable change (individual level); TT, tendon thickness.

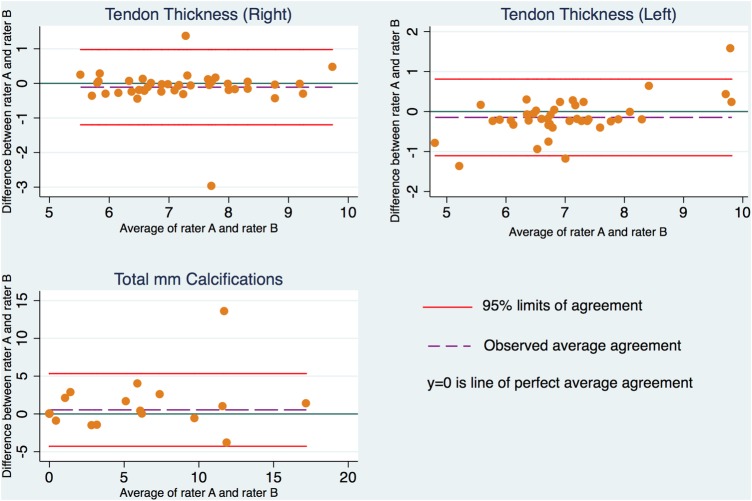

No systematic rater differences were found in measured TT and total length of CA (table 5). Bland-Altman plots showed no funnel effects, but a small interaction between difference and increased mean was found for TT in the left shoulder (r=0.35, p=0.03; figure 2). In general, LOA showed a larger variation for CA than for TT (table 5 and figure 2).

Figure 2.

Bland-Altman plots with 95% LOA for TT (right and left) and total length of CAs. CA, calcifications; LOA, limits of agreement; TT, tendon thickness.

No significant difference was found between cases and controls in TT.

Discussion

The inter-rater reliability study showed moderate to perfect reliability for grading FD, NV and number of CAs, using standardised procedures. Inter-rater reliability for measuring the total length of CA and TT was excellent, and MDC indicated small detectable changes for group level, especially in TT.

FD and hypoechoic areas

Despite merging hypoechoic areas and FD into one scale, reliability was still only moderate (LWk of 0.60 and 0.51). This was, however, in line with previous studies of tendinopathy, where agreement on subtle changes (‘mild abnormality’ and ‘normal’) was considered especially difficult, presumably due to difficulties in differing structural changes and anisotropy.4 6 8 10 11 Grading FD may be more easily interpreted with in vivo US examinations, as the examiner is more flexible when evaluating presence of anisotropy.

Neovascularisation

The current reliability of NV was almost perfect. The reason for the high reliability in the current study may be the grading of NV in relation to a predetermined ROI (fixed box of 5×5 mm placed over the area with most NV), as opposed to grading NV relative to the TT or the tendon in general as previously in tendinopathy of the elbow.4 16 The current modification was performed to increase standardisation, as well as to account for between and within variations in TT, of interest in intervention studies.

Other studies have found prevalence of NV in 30–65% of symptomatic shoulders with only 25% of asymptomatic shoulders.27 28 This study found prevalence of NV in 38% of the cases and 0% in the control group. This large variation in prevalence across previous studies may be due to different populations, PD settings, measurement methods and the position of the participant arm during US image capturing. This study placed the hand at the sacrum, to maximally stretch the supraspinatus tendon, which may have increased the risk of overlooking NV due to restricted flow in the neovessels. Different study designs across studies make it difficult to compare prevalence and establish normative levels for use in clinical practice.

Calcification

The substantial κ for detecting the total number of CA is in line with previous studies,4 8 but LOA, SEM and MDC showed considerable variation on the total length of CA. This variation may be due to US methodological problems, for example, that shadows underneath CA may falsely be interpreted as FD and/or normal tendon structure may appear hyperechoic, thus resembling CA, which may result in misclassifications. However, reliability of number of CA was high, indicating that measuring individual lengths of CA and/or few undetected/misclassified CA have influenced agreement of total length of CA. One outlier seen in the Bland-Altman plots (figure 2) indicates that raters A and B disagreed on at least one larger structural change, which, owing to the generally small size and low prevalence of CA, has influenced the variation considerably.

Tendon thickness

Excellent reliability, and MDC of ≤0.33 mm, indicates that the variable is sensitive for detecting changes, in line with a previous study using the same method for measuring TT.18 This means that it may be a clinically relevant measurement for assessment of changes in tendon properties, such as increased/decreased oedema. Some studies have found significant differences in TT between symptomatic and non-symptomatic participants,29 30 which are in contrast with the current study and a recent study.18 The reason for the discrepancy across studies may be due to the use of different methods for measuring TT, small sample sizes, different inclusion criteria or, as in this study, the inclusion of more active controls (recruited among health personnel) with potentially thicker tendons than the average population.

One limitation of the study is the transferability to clinical setting, as this study used captured images and strictly standardised procedures, which are rarely used in clinical settings. In vivo, raters would be more flexible when evaluating presence of anisotropy in the interpretation of potential FD; also, they would be able to perform repeated image capturing and measurements when CA or NV were suspected to be present. Use of a standardised protocol for reliability studies13 may be a weakness, since reliability of the current US method and procedures may have been deceptively high compared with a clinical setting. However, if the standardised method has poor reliability in a standardised setting, reliability is also assumed to be poor and the method less relevant for use in a clinical setting. The raters measured and graded the captured images and movies on different DICOM viewers. Whether this has influenced the reliability is unknown. However, since reliability is found to be high on most variables, it is considered to not be important and to mimic clinical practice.

The strengths of this study are the design, incorporating a stepwise and standardised procedure in order to minimise bias and increase reliability.13 The present standardisation of US image and movie capturing, measuring and grading structural changes are anticipated to increase reliability and sensitivity of the method. Despite one of the raters having relatively few years of US experience, reliability was still high and satisfactory, indicating that the protocol can even be followed by other than very US-experienced clinicians. By using captured images and movie sequences, it was ensured that both raters had equal underlying bases for interpretation of the reliability study.

Further, the use of weighing with restrictions when calculating κ was considered important, due to the importance of being able to differ between cases and controls.

Conclusion

Inter-rater reliability was moderate to almost perfect when a standardised procedure was applied for measuring structural changes on captured US images and movie sequences of relevance for patients with supraspinatus tendinopathy. Future studies should test intra-rater and inter-rater reliability of the method in vivo for use in clinical practice, in addition to validation against a gold standard, such as MRI.

Footnotes

Contributors: KGI, BJ-K, HE and CML conceived and designed the study protocol. KGI and BJ-K procured the project funding. KGI, BJ-K, JV and JH developed and standardised the ultrasound procedure and defined the grading scale. JV and JH secured access and coordinated screening procedures at the shoulder units. KGI was the project coordinator and performed the inclusion and US image capturing. KGI and JH were raters. KGI and BJ-K planned and coordinated the statistical analyses. KGI performed the statistical analyses. KGI drafted the manuscript, and BJ-K, JH, JV, HE and CML contributed to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. KGI is the guarantor.

Funding: Region of Southern Denmark's Research fund, The Danish Rheumatism Association and the Ryholts Foundation funded the trial.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The Regional Scientific Ethics Committee of Southern Denmark has approved the trial (project ID: S-20130071).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Cook JL, Purdam CR. Is tendon pathology a continuum? A pathology model to explain the clinical presentation of load-induced tendinopathy. Br J Sports Med 2009;43:409–16. 10.1136/bjsm.2008.051193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewis JS. Rotator cuff tendinopathy: a model for the continuum of pathology and related management. Br J Sports Med 2010;44:918–23. 10.1136/bjsm.2008.054817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hegedus EJ, Goode A, Campbell S et al. Physical examination tests of the shoulder: a systematic review with meta-analysis of individual tests. Br J Sports Med 2008;42:80–92; discussion 92 10.1136/bjsm.2007.038406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poltawski L, Ali S, Jayaram V et al. Reliability of sonographic assessment of tendinopathy in tennis elbow. Skeletal Radiol 2012;41:83–9. 10.1007/s00256-011-1132-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ottenheijm RP, Jansen MJ, Staal JB et al. Accuracy of diagnostic ultrasound in patients with suspected subacromial disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2010;91:1616–25. 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naredo E, Möller I, Moragues C et al. Interobserver reliability in musculoskeletal ultrasonography: results from a “Teach the Teachers” rheumatologist course. Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65:14–19. 10.1136/ard.2005.037382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ottenheijm RP, van't Klooster IG, Starmans LM et al. Ultrasound-diagnosed disorders in shoulder patients in daily general practice: a retrospective observational study. BMC Fam Pract 2014;15:115 10.1186/1471-2296-15-115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Connor PJ, Rankine J, Gibbon WW et al. Interobserver variation in sonography of the painful shoulder. J Clin Ultrasound 2005;33:53–6. 10.1002/jcu.20088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thoomes-de Graaf M, Scholten-Peeters GG, Duijn E et al. Inter-professional agreement of ultrasound-based diagnoses in patients with shoulder pain between physical therapists and radiologists in the Netherlands. Man Ther 2014;19:478–83. 10.1016/j.math.2014.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Connor PJ, Grainger AJ, Morgan SR et al. Ultrasound assessment of tendons in asymptomatic volunteers: a study of reproducibility. Eur Radiol 2004;14:1968–73. 10.1007/s00330-004-2448-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sunding K, Fahlstrom M, Werner S et al. Evaluation of Achilles and patellar tendinopathy with greyscale ultrasound and colour Doppler: using a four-grade scale. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2014. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weinreb JH, Sheth C, Apostolakos J et al. Tendon structure, disease, and imaging. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J 2014;4:66–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patijn JV, Beek JV, Blomberg S et al. Reproducibility and validity studies of diagnostic procedures in manual/musculoskeletal medicine. In: J Patijn, ed.. International Federation for manual/musculoskeletal medicine. 2004:3–35. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohberg L, Alfredson H. Ultrasound guided sclerosis of neovessels in painful chronic Achilles tendinosis: pilot study of a new treatment. Br J Sports Med 2002;36:173–5; discussion 176-7 10.1136/bjsm.36.3.173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Venu KM, Howlett DC, Garikipati R et al. Evaluation of the symptomatic supraspinatus tendon—a comparison of ultrasound and arthroscopy. Radiography 2002;8:235–40. 10.1053/radi.2002.0382 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krogh TP, Fredberg U, Stengaard-Pedersen K et al. Treatment of lateral epicondylitis with platelet-rich plasma, glucocorticoid, or saline: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Sports Med 2013;41:625–35. 10.1177/0363546512472975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ottenheijm RP, Joore MA, Walenkamp GH et al. The Maastricht Ultrasound Shoulder pain trial (MUST): ultrasound imaging as a diagnostic triage tool to improve management of patients with non-chronic shoulder pain in primary care. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2011;12:154 10.1186/1471-2474-12-154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hougs Kjaer B. Intra-rater and inter-rater reliability of standardized ultrasound protocol for assessing subacromial structures (Submitted after revision). Physiother Theory Pract 2017. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ingwersen KG, Hjarbaek J, Eshoej H et al. Sonographic assessment of supraspinatus tendinopathy as a future diagnostic and effect measure—a reliability study of the assessment methode. XXV Congress of the International Society of Biomechanics; Glasgow, UK: ISB, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martinoli C. Musculoskeletal ultrasound: technical guidelines. Insights Imaging 2010;1:99–141. 10.1007/s13244-010-0032-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ingwersen KG, Christensen R, Sørensen L et al. Progressive high-load strength training compared with general low-load exercises in patients with rotator cuff tendinopathy: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2015;16:27 10.1186/s13063-014-0544-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sim J, Wright CC. The kappa statistic in reliability studies: use, interpretation, and sample size requirements. Phys Ther 2005;85:257–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159–74. 10.2307/2529310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fleiss JL. Reliability of measurement. The design and analysis of clinical experiments. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Vet HC, Terwee CB, Knol DL et al. When to use agreement versus reliability measures. J Clin Epidemiol 2006;59:1033–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Vet HCW TC, Mokkink LB, Knol DLL. Measurement in medicine—a practical guide. New York, USA: Cambridge University Press, New York, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kardouni JR, Seitz AL, Walsworth MK et al. Neovascularization prevalence in the supraspinatus of patients with rotator cuff tendinopathy. Clin J Sport Med 2013;23:444–9. 10.1097/JSM.0b013e318295ba73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewis JS, Raza SA, Pilcher J et al. The prevalence of neovascularity in patients clinically diagnosed with rotator cuff tendinopathy. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2009;10:163 10.1186/1471-2474-10-163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arend CF, Arend AA, da Silva TR. Diagnostic value of tendon thickness and structure in the sonographic diagnosis of supraspinatus tendinopathy: room for a two-step approach. Eur J Radiol 2014;83:975–9. 10.1016/j.ejrad.2014.02.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Michener LA, Subasi Yesilyaprak SS, Seitz AL et al. Supraspinatus tendon and subacromial space parameters measured on ultrasonographic imaging in subacromial impingement syndrome. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2015;23:363–9. 10.1007/s00167-013-2542-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-011746supp.pdf (2.8MB, pdf)