Significance

Lagging-strand DNA is replicated in multiple segments called Okazaki fragments, whose formation involves a complex molecular cycle mediated by DNA primase, polymerase, and other replisome components. In addition, synthesis of the lagging strand must occur in lockstep with the leading strand. Using the simple replication system of bacteriophage T7, we found that primer release from the DNA primase domain of T7 primase helicase is a critical regulatory event in the initiation of Okazaki fragments and that the T7 single-stranded binding protein, gp2.5, regulates initiation timing.

Keywords: Okazaki fragment, DNA primase, replisome, primer

Abstract

DNA replication occurs semidiscontinuously due to the antiparallel DNA strands and polarity of enzymatic DNA synthesis. Although the leading strand is synthesized continuously, the lagging strand is synthesized in small segments designated Okazaki fragments. Lagging-strand synthesis is a complex event requiring repeated cycles of RNA primer synthesis, transfer to the lagging-strand polymerase, and extension effected by cooperation between DNA primase and the lagging-strand polymerase. We examined events controlling Okazaki fragment initiation using the bacteriophage T7 replication system. Primer utilization by T7 DNA polymerase is slower than primer formation. Slow primer release from DNA primase allows the polymerase to engage the complex and is followed by a slow primer handoff step. The T7 single-stranded DNA binding protein increases primer formation and extension efficiency but promotes limited rounds of primer extension. We present a model describing Okazaki fragment initiation, the regulation of fragment length, and their implications for coordinated leading- and lagging-strand DNA synthesis.

Replicative DNA polymerases require a primer for initiation (1, 2). Although various priming strategies exist, the most ubiquitous involves use of short RNAs synthesized by DNA primases. Although the leading strand is synthesized continuously in the direction of replication fork movement, the lagging strand is synthesized in small segments called Okazaki fragments that are later joined together. Initiation of Okazaki fragment synthesis is a complex, tightly regulated process involving multiple enzymatic events and molecular interactions (1, 3).

The replication machinery of bacteriophage T7 is among the simplest replication systems (4, 5). Only four proteins are required to reconstitute coordinated DNA synthesis in vitro: gene 4 primase-helicase (gp4) unwinds the DNA duplex to provide the template for DNA synthesis. T7 DNA polymerase (gp5), in complex with its processivity factor, Escherichia coli thioredoxin (Trx), is responsible for synthesis of leading and lagging strands. Finally, gene 2.5 single-stranded (ss)DNA-binding protein (gp2.5) stabilizes ssDNA replication intermediates and is essential for coordination of DNA synthesis on both strands. The elegant simplicity of the T7 replication machinery makes it an attractive system for investigating molecular and enzymatic events occurring during DNA replication.

In T7-infected E. coli, Okazaki fragments are initiated by synthesis of tetraribonucleotides by the primase activity of gp4 (6) (Fig. 1A). Gp4 catalyzes the formation of tetraribonucleotides at specific template sequences, designated “primase recognition sites” (PRSs) (7). On encountering a 5′-GTC-3′ sequence, gp4 catalyzes the synthesis of the dinucleotide pppAC. The “cryptic” cytosine in the recognition site is not copied into the oligoribonucleotide. The dinucleotide is extended to a trinucleotide, and finally, to the functional tetraribonucleotide primers, pppACCC, pppACCA, or pppACAC if the appropriate complementary sequence is present (8). Once primers are synthesized, they are delivered to the lagging-strand polymerase (9–11). T7 DNA polymerase alone cannot efficiently use primers shorter than 15 nt in vitro. However, in the presence of gp4, it uses tetramers as primers for DNA synthesis. Therefore, gp4 is critical not only for primer formation, but also for enabling the use of short oligoribonucleotides by T7 DNA polymerase. Critically, the primase domain also fulfills two additional roles apart from primer synthesis: it prevents dissociation of the extremely short tetramer, stabilizing it with the template, and it secures it in the polymerase active site (10, 12).

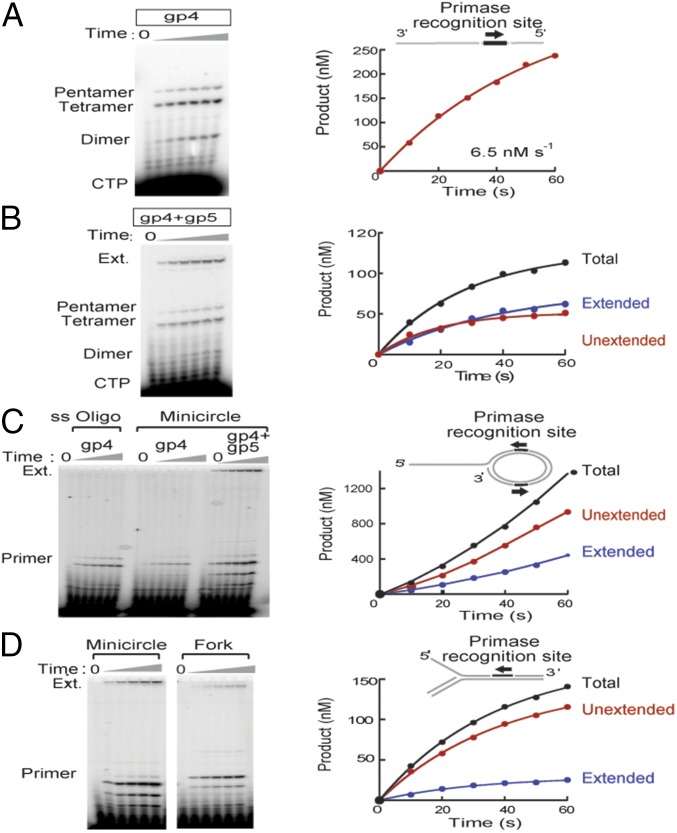

Fig. 1.

Primer synthesis and extension by gp4 and T7 DNA polymerase. (A) gp4 unwinds dsDNA, using its C-terminal helicase domain. At PRSs, the gp4 primase domain synthesizes a short RNA, stabilizing it on the template and mediates its transfer to T7 DNA polymerase. (B) Gp4 enables T7 DNA polymerase to extend tetraribonucleotides; 0.1 µM gp4 hexamer or 0.2–25 µM gp4 primase fragment (PF) was incubated with ssDNA in the absence or presence of T7 DNA polymerase for 5 min at 25 °C. Products are indicated to the right of the gel image. Pentamers are likely not extended efficiently (37, 38). (C) Klenow fragment of E. coli DNA polymerase I and T4 DNA polymerase cannot extend short RNAs synthesized by gp4. Reactions were initiated by adding 10 mM MgCl2, and samples were taken at 10-s intervals. The 0 time point corresponds to a sample of the reaction before MgCl2 addition.

Here we show that the rate-limiting step in initiation of Okazaki fragments by the T7 replisome is primer release from the primase domain of gp4. In the absence of gp2.5, an additional step, distinct from primer release, also limits primer extension. The presence of gp2.5 promotes efficient primer formation and primer utilization. Finally, we propose a model for events controlling Okazaki fragment initiation, length, and coordination with synthesis of the leading strand.

Results

The Use of Short Oligoribonucleotides as Primers by T7 DNA Polymerase Is Dependent on gp4.

T7 gp4 synthesizes tetraribonucleotides from ATP and CTP in the presence of divalent cations and ssDNA containing a PRS (Fig. 1 A and B). In the presence of T7 DNA polymerase, the tetraribonucleotides are extended by incorporation of deoxyribonucleotides in a template-dependent manner (Fig. 1B). Although the primase domain of gp4 is alone sufficient for primer synthesis (13), it enables their use by T7 DNA polymerase ineffectively. The enhanced use of primers by full-length gp4 suggests that the polymerase engages gp4 through contacts with the primase and helicase domains or the helicase domain efficiently tethers the primase domain to DNA. The requirement for a physical interaction between gp4 and T7 DNA polymerase to promote primer extension (14, 15) is underscored by the inability of other polymerases, such as T4 DNA polymerase or the Klenow fragment of E. coli DNA polymerase I, to extend primers synthesized by gp4 (Fig. 1B).

Primer Synthesis Is More Efficient Than Primer Extension.

We determined the kinetics of oligoribonucleotide synthesis and their extension by DNA polymerase using a 26-nt ssDNA template containing a single PRS. Using this template, full-length primers accumulate at a steady-state rate of ∼6.5 nM/s (Fig. 2A). This rate of primer accumulation corresponds to a kcat for primer synthesis of 0.1 s−1 (calculated as described in SI Materials and Methods, using the initial rate of primer synthesis and data in Fig. S1). This result is inconsistent with a previous report (16) of the catalytic activity of a T7 primase fragment where synthesis of pppAC occurs with a rate constant of ∼4 s−1. Our result strongly suggests the existence of a step slower than dimer synthesis in the complete primer synthesis pathway. This step was not observable in the previous report because the authors used a substrate designed to produce dimers exclusively.

Fig. 2.

Primer utilization is slower than primer synthesis. (A, Left) Time course of primer synthesis by gp4 using a ssDNA with a single PRS. Samples were taken before addition of MgCl2 (t = 0) and in 10-s intervals following its addition. Products are indicated. (Right) Primer (tetra- and pentamer) concentration vs. time. The initial rate of primer formation is shown. Product concentration was determined as described in Materials and Methods. (B, Left) Time course of primer synthesis and extension by gp4 and T7 DNA polymerase. Products are indicated (Ext = extended product). (Right) Product concentration vs. time. Extended primer (blue), free (unused) primer (red), and total primer (black). (C, Left) Time course of primer synthesis and extension in the presence of gp4 and T7 DNA polymerase with a minicircle template, diagramed at Upper Right. Presence of gp4 and gp5/Trx is indicated. (Right) Product concentration vs. time for the minicircle reaction. (D, Left) Time course of primer synthesis and extension in the presence of gp4 and T7 DNA polymerase with a fork template (diagramed Upper Right). For comparison, a reaction using the minicircle in C as template is included (run on the same gel, but cropped for simplicity). (Right) Product concentration vs. time for the fork substrate.

Fig. S1.

Active-site titration of gp4 by measurement of product burst amplitude. A fixed, nominal concentration of gp4 (1 µM hexamer, determined by Bradford assay) was incubated at 25 °C with increasing concentrations of a single-stranded template containing a primase recognition site, in the presence of ATP and [α-32P] CTP. Reactions were started by the addition of MgCl2 to a final concentration of 10 mM, allowed to react for 1 s, and quenched with 125 mM EDTA and 0.1% SDS. Products were resolved by denaturing PAGE, and visualized by phosphorimager. The concentration of full-length primer product formed was plotted as a function of template concentration, and the data were fit to a quadratic equation to determine the maximum amount of active gp4–DNA complex formed (0.505 µM) and the KD for their interaction (50 nM). The percentage of active gp4 in our preparations was consistently ∼50%.

Under our experimental conditions, accumulation of extended primer over time follows an exponential shape (Fig. 2B). Fitting extension product concentration over time to an exponential function yielded an observed rate constant for primer utilization of ∼0.03 s−1, a value 10,000-fold smaller than the rate-limiting step of nucleotide incorporation, kpol, for T7 DNA polymerase (∼300 s−1) (17), but closer to the kcat for primer synthesis we obtained. To extend this finding, we examined the relationship between primer synthesis by gp4 and primer extension by T7 DNA polymerase using a variety of DNA constructs (Fig. 2 C and D). In all cases, we observed that synthesis of oligonucleotides by gp4 is more efficient than their utilization by the polymerase.

We tested the rate of primer utilization as a function of primer synthesis rate by varying the concentration of ATP and CTP and measuring the rate of formation of extension product (Fig. 3A). The observed primer utilization rate increases hyperbolically as a function of nucleotide concentration. Fitting these data to a hyperbolic equation yielded a maximum utilization rate of ∼0.03 s−1 (Fig. 3A). To determine whether oligoribonucleotide synthesis per se is responsible for the slow extension, we bypassed the first nucleotide condensation step. Formation of the initial dinucleotide is thought to be the rate-limiting step in primer synthesis by all primases (18). Using a preformed AC dinucleotide, and CTP, we obtained similar maximal rates of primer use as in reactions primed de novo (Fig. 3A, Center). Likewise, bypassing primer synthesis altogether by supplying a preformed tetraribonucleotide, ACCC, resulted in the same maximum rate of extension (Fig. 3A, Right and Fig. S2). A summary of the results from these experiments is presented in Fig. 3B. The maximum observed rate of primer extension is identical, within error, for all three conditions. These results suggest that a step after primer synthesis, but before DNA synthesis, is critical for extension of primers by DNA polymerase. The observed rate of primer extension increases linearly with polymerase concentration until ∼400 nM polymerase, a twofold excess over the total gp4 hexamer present, after which it is constant (Fig. 3C), suggesting that inefficient primer extension is not a consequence of polymerase binding, which we have previously shown to be rapid (19).

Fig. 3.

Primer synthesis does not limit extension. (A, Left) Primer extension reactions were carried out with varying concentrations of ATP and CTP, using [α-32P] dGTP to visualize extension products only. Observed rate constants, kobs, for primer utilization were plotted as a function of nucleotide concentration. (Center) Observed rate constant for primer utilization as a function of AC concentration. Reactions contained 0.5 mM CTP to allow extension of the dinucleotide to a primer. (Right) Observed rate constant for primer extension as a function of the concentration of the tetraribonucleotide ACCC. (B) Tabular representation of the data from A. (C) Observed rate of primer utilization as a function of T7 DNA polymerase concentration. Reaction time courses were fit as above, and the observed rate constant for extension is plotted as a function of polymerase concentration.

Fig. S2.

Primer extension progress curves used to construct the plots in Fig. 3A. Varying concentrations of ATP and CTP (Left), AC diribonucleotide [with a constant (CTP)] (Center), and preformed tetranucleotide ACCC (Right) were used in primer synthesis and extension reactions set up as in Fig. 2B using [α-32P] dGTP to detect extension products only. Concentrations of nucleotides (in μM) are indicated to the right of each curve. The lines represent fits to single-exponential equations. Aliquots were removed at 10-s intervals on addition of 10 mM MgCl2.

Primer Release Is Rate Limiting as Determined by Pre–Steady-State Analysis.

We examined the pre–steady-state kinetics of primer formation by gp4 to better understand the pathway of primer synthesis. Primer formation shows a pre–steady-state burst (Fig. 4A). This type of kinetic behavior is indicative of slow product release following its fast formation (20). The burst of primer formation by gp4 occurs with an observed rate constant of ∼1.5 s−1, followed by a steady state with a rate constant of 0.1 s−1. This result shows that primer synthesis occurs rapidly, and primers are retained by the enzyme after formation, only to be slowly released (Discussion). We conclude that the rate-limiting step in the full pathway for primer synthesis is not dinucleotide formation as previously suggested (6, 16, 18), but the release of primer from the primase active site.

Fig. 4.

Pre–steady-state analysis of primer synthesis and extension. (A) Primer synthesis by gp4 occurs with a burst of primer formation. (Left) Time course of primer synthesis by gp4 using an ssDNA with a single PRS using a rapid quench-flow instrument. (leftmost well:10-min control). (Right) Primer formation vs. time. Data were fit to the pre–steady-state burst equation. (B) Single-turnover primer synthesis by gp4. (Left) Time course of tetramer formation. (Right) Plot of product formation vs. time. Data were fit by numerical integration to the model shown; solid lines show the fit. (C) Single-turnover primer synthesis and extension by gp4 and T7 DNA polymerase. (Left) Denaturing PAGE of reaction time course. (Right) Plot of product formation vs. time. Used primer (blue), free primer (red), and total primer (black). Data were fit to single- or double-exponential functions. Observed rate constants and reaction amplitudes are indicated.

Primer formation is the result of three nucleotidyl transfer reactions. To obtain information on the rate of nucleotide incorporation for each step, as well as information about “abortive” release of intermediates, we used single-turnover primer synthesis experiments. A low concentration of labeled ATP is present with a high concentration of T7 gp4, template, and CTP. The experimental data fit well to a model with three nucleotide condensation steps (Fig. 4B). As reported previously (16), dinucleotide formation occurs rapidly, with a rate constant of ∼4 s−1. The dimer is in equilibrium with the enzyme, and readily dissociates, as evidenced from their accumulation in primer synthesis reactions. Both subsequent CMP incorporation steps are faster than dimer formation by at least fivefold (20 and >50 s−1 for the second and third CMP incorporation steps, respectively). Although the trimer intermediate is capable of dissociating from the primase, the reaction is pushed toward tetramer formation by the comparatively rapid sequential incorporation steps.

Primer Release and Handoff Are Control Points for DNA Chain Initiation.

If primer release is rate limiting in initiating lagging-strand DNA synthesis, the rate of primer utilization under conditions where primer synthesis occurs in a single-turnover regime should be the same as under multiple-turnover conditions. Primer extension under single-turnover primer synthesis proceeds with an observed first-order rate constant of 0.03 s−1 (Fig. 4C), a rate identical to multiple-turnover primer extension experiments. Examination of primer extension progress curves after short reaction times (<2 s) revealed the presence of a lag phase in primer extension (Fig. S3), suggesting that the kinetics we observe result from at least two steps in the pathway, of approximately equal magnitude (20, 21). Fitting the data by numerical integration to a model consisting of two consecutive, irreversible steps yields values for rate constants, k1 = 0.1 s−1 and k2 = 0.05 s−1. Intriguingly, the value of the first rate constant is identical to the kcat for full-length primer synthesis, which we show above to represent primer release. We interpret the second rate constant to represent a slow primer handoff to the polymerase, which may involve repositioning the primer/template into the polymerase active site. Therefore, at least two steps, of similar magnitude, occur on the initiation pathway of Okazaki fragments. In parallel rapid-quench experiments, we determined that T7 DNA polymerase extends a primer annealed to a single-stranded DNA template rapidly (Fig. S4) in agreement with previous reports (17).

Fig. S3.

Observation of a lag in primer extension. (A) Primer synthesis and extension reactions were assembled as described in Materials and Methods and analyzed using a rapid-quench instrument. Samples (t = 0, 0.2, 0.25, 0.3, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1, 2, 3.5, 5, 7.5, and 10 s) were resolved by denaturing PAGE. (B) The extension product was quantified and plotted as a function of time; data up to 2 s are shown. A lag in product buildup, indicating a step preceding the observed state, is clearly visible.

Fig. S4.

DNA synthesis by T7 DNA polymerase is rapid. (A, Top) Time course of primer extension by T7 DNA polymerase in the presence of all four dNTPs. Enzyme (1 µM) was incubated with the single-stranded template used for primer synthesis and extension reactions (0.1 µM) (which was annealed to a 5′-end–labeled 19-nt primer). The reaction was initiated by the addition of 10 mM MgCl2 and 0.3 mM dNTPs (t = 0, 0.0035, 0.004, 0.005, 0.0075, 0.01, 0.015, 0.02, 0.025, 0.035, 0.05, 0.075, and 0.1 s). (Middle) Products were resolved by denaturing PAGE. (Bottom) Extension species were quantified and plotted as a function of time. The data were fit to a processive polymerization model using Kintek Explorer (Kintek), yielding a rate constant for the first polymerization step of 140 s−1. Fitting the decay of intact primer gives a rate constant of similar magnitude (180 s−1). (B) Time course of single-nucleotide incorporation by T7 DNA polymerase. (Upper) Time course of primer extension by T7 DNA polymerase using the primer/template and reaction conditions as in A and the next encoded nucleotide, dGTP only (0.3 mM final concentration). Denaturing PAGE showing that the primer is rapidly extended by the addition of a single nucleotide (t = 0.005, 0.0075, 0.01, 0.015, 0.025, 0.03, 0.05, 0.075, 0.1, 0.15, 0.25, 0.3, and 0.75 s). (Lower) The fraction of product formed was plotted as a function of time (up to 0.15 s) and the data fit to a single-exponential equation, yielding the rate constant for single-nucleotide incorporation, 240 s−1, a value in line with those reported elsewhere (17).

gp2.5 Enhances Primer Synthesis and Promotes Primer Extension.

gp2.5 is critical for coordinating leading- and lagging-strand DNA synthesis (22–24). In addition to DNA binding (25), it interacts with T7 DNA polymerase and gp4 through its acidic C-terminal tail (26, 27). However, the effect of gp2.5 on primer synthesis by gp4 has thus far been equivocal (28, 29).

Gp2.5 slightly tempers primer synthesis using a single-PRS ssDNA template (6.5 vs. 3 nM/s, − and + gp2.5, respectively). DNA binding by gp2.5 may interfere with the ability of gp4 to engage the PRS. We note, however, that the proportion of dimer intermediate in the presence of gp2.5 is diminished by approximately fourfold (Fig. 5A). We observed a similar result with a fork substrate, which has to be first unwound to reveal the PRS (Fig. S5B). Decreased dimer accumulation in the presence of gp2.5 suggests that it may inhibit dissociation of primer intermediates from gp4. Competition experiments, where increasing concentrations of AC dinucleotide were titrated into primer synthesis reactions with or without gp2.5, suggest that gp2.5 decreases dimer dissociation modestly (Fig. S6).

Fig. 5.

gp2.5 increases the efficiency of primer synthesis and extension while restricting product formation. (A) Effect of gp2.5 on primer synthesis. (Upper) Primer synthesis ± 3 µM gp2.5 (t = 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 s). (Lower) primer formation vs time. − (blue) and + (red) 3 µM gp2.5 (t = 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60 s). The initial rate of primer formation is indicated. (B) Effect of gp2.5 on primer synthesis and extension. (Upper) Primer synthesis and extension in the absence and presence of gp2.5. Primer and extension products are indicated (t = 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60 s). (Lower) normalized product formation vs. time for reactions lacking gp2.5 (blue), or with WT (red) or Δ-C gp2.5 (green). (t = 0, 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, and 100 s). Observed rate constants are indicated. (C) Effect of gp2.5 on single-turnover primer synthesis and extension. (Left) Primer synthesis and extension (Materials and Methods) ± 20 µM gp2.5. (t = 0, 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, 100, and 300 s). Primer and extension products are indicated. Right, normalized product formation vs. time for single-turnover reactions lacking gp2.5 (blue), or in the presence of WT gp2.5 (red). (t = 0, 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, and 100 s). Observed rate constants are indicated.

Fig. S5.

(A) Unnormalized plots of product formation vs. time in Fig. 5. (Left) Product formation as a function of time for multiple-turnover primer synthesis reactions lacking gp2.5 (blue), in the presence of WT (red), or Δ-C gp2.5 (green) (t = 0, 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, and 100 s) Observed rate constants and reaction amplitudes are indicated. (Right) Product formation as a function of time for single-turnover primer synthesis reactions lacking gp2.5 (blue), or in the presence of WT gp2.5 (red) (t = 0, 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, and 100 s). Observed rate constants and reaction amplitudes are indicated. (B) Gp2.5 also enhances tetramer formation by gp4 on a fork substrate. (Upper) Representation of fork DNA substrate used (0.1 µM). (Lower) Time course of primer synthesis catalyzed by gp4 (0.1 µM hexamer) in the absence (Left) and presence (Right) of 3 µM gp2.5, using [α-32P] CTP as the labeled substrate (t = 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60 s). Products are indicated to the left of the gel picture. The samples were produced in the same experiment but were run on different gels. (C) E. coli SSB does not inhibit primer extension. Reactions were set up as in Fig. 5B, with 3 μM gp2.5 or E. coli SSB, and aliquots were removed at 10-s intervals on addition of 10 mM MgCl2.

Fig. S6.

Gp2.5 decreases the dissociation of the dimer product. (A) Scheme to test the effect of gp2.5 on dimer dissociation by competitive inhibition of primer synthesis by gp4. Primer synthesis reactions (as in Fig. 2A) containing ATP and labeled CTP were incubated with various concentrations of exogenously added, unlabeled AC diribonucleotide, in the absence and in the presence of 3 μM gp2.5. (B) Plot of the relative rate of primer synthesis as a function of added AC concentration. AC inhibits primer synthesis reactions lacking gp2.5 with a Ki of 30 µM. This value is 60 µM in the presence of gp2.5. A higher concentration of unlabeled AC dinucleotide being required to inhibit primer synthesis suggests that a lower proportion of labeled intermediates are lost through dissociation.

The effect of gp2.5 on extension of gp4-synthesized primers by T7 DNA polymerase is complex. Gp2.5 inhibits primer extension (Fig. S5A), which may be due to DNA binding by gp2.5 sequestering available template. However, extension products are detected at earlier times, reaching a plateau earlier than reactions lacking gp2.5 (Fig. 5B), or those that contain either E. coli SSB protein or gp2.5 Δ-C, a gp2.5 variant lacking the acidic C-terminal tail that retains DNA binding but does not interact with other T7 replication proteins (30) (Fig. 5B and Fig. S5C). Importantly, the presence of gp2.5 does not inhibit DNA synthesis by T7 DNA polymerase. (Fig. S7). Fitting the appearance of extension products over time to an exponential function yields an observed rate constant for primer extension of 0.1 s−1. This value is in line with the value for the observed rate constant for primer release from gp4. We also examined the effect of gp2.5 on primer extension under single-turnover primer synthesis conditions. In agreement with the results in Fig. 5B, gp2.5 enhances the rate of formation of extension product, but limits overall extension (Fig. 5C and Fig. S5A). Rate constants for primer extension in the presence of gp2.5 in multiple-and single-turnover primer synthesis conditions are identical, within error.

Fig. S7.

Gp2.5 does not inhibit T7 DNA polymerase. (A and B) Denaturing PAGE showing efficient extension of 0.1 μM 5′-end–labeled primers by 0.4 μM T7 DNA polymerase in the presence of 0.1 μM gp4 hexamer and/or 3 μM gp2.5 using (A) a primer/template duplex (Right: t = 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60 s; Left: t = 0, 5, 10, 20, 30, and 40 s) or (B) a fork substrate (Right and Left: t = 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60 s; Center: t = 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 s). The structure of the substrate is shown above the gel pictures. (C) Gp2.5 (0, 0.11, 0.33, 1, 3, and 9 μM) enhances DNA synthesis by T7 DNA polymerase (50 nM) using a primed-M13 substrate (20 nM).

These results suggest that two observable kinetic steps, of approximately equal magnitude, are rate limiting for DNA initiation when only gp4 and T7 DNA polymerase are present. We surmise that primer release and handoff are these critical steps. In the presence of gp2.5, however, the extension rate constant is equal to the primer release rate, suggesting that gp2.5 enables optimal assembly of the priming complex and/or primer positioning into the polymerase active site. Consequently, the only step-limiting primer extension in the presence of all T7 replisome components is the release of full-length primer from gp4.

gp2.5 Regulates Lagging-Strand Synthesis by Limiting Primer Synthesis and Utilization.

One of the hallmarks of coordinated DNA synthesis is the relatively narrow size range of Okazaki fragments, centering around 1,000 nt in length in T7-infected E. coli, and under coordinated DNA synthesis in vitro (22, 23), whereas fragments resulting from uncoordinated synthesis are 500 nt or smaller. This observation suggests that during uncoordinated synthesis, primer extension and/or Okazaki fragment termination occur frequently and that coordination of DNA synthesis involves regulatory timing events on the lagging strand. We reasoned that gp2.5 leads to longer Okazaki fragments by limiting primer extension events.

We therefore examined the effect of gp2.5 and gp2.5 Δ-C on Okazaki fragments derived from a minicircle template in reactions with radiolabeled CTP. This labeling results in primers and Okazaki fragments of equal specific activity, allowing a more accurate comparison. Lagging-strand products in reactions containing WT gp2.5 display a higher molecular weight than in reactions lacking gp2.5 or in the presence of gp2.5 Δ-C. However, our ability to accurately determine the size of the products was precluded by our use of native conditions during electrophoresis to maintain the integrity of the labeled RNA termini (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Gp2.5 regulates Okazaki fragment length through primer utilization. (A) Effect of WT or Δ-C gp2.5 (3 µM) on lagging-strand DNA (labeled at the primer terminus). (Left) Samples quenched at 1 or 5 min were loaded on a 0.8% agarose gel (size markers are indicated). Brackets indicate range of extension products. (Right) Effect of gp2.5 on primer synthesis and extension using a minicircle. Samples taken at 10-s intervals and loaded on a denaturing 25% polyacrylamide gel. (B) Quantification of A. (C) Effect of gp2.5 on the time course of lagging-strand product formation. Samples were loaded on a 5% denaturing polyacrylamide gel; 5′ end-labeled size markers are indicated. A labeling artifact dependent on gp5 and gp2.5 is indicated (*).

The presence of gp2.5 leads to decreased levels of extended primer (Fig. 6B). In the presence of gp2.5, ∼4% of primers are used, however, extension products in reactions containing gp2.5 reach a higher molecular weight, greater than 1.5 kb (close to the mobility limit of the gel), determined by denaturing PAGE, and are evident even at the shortest time point analyzed (10 s) (Fig. 6C). The periodicity in the pattern of extension products also shows that PRSs are over-used, i.e., intervening bands representing initiation/termination events of primer extension are overrepresented in the absence of gp2.5 and in the presence of gp2.5 Δ-C. However, when WT gp2.5 is present, these intervening bands are greatly reduced. Thus, gp2.5 restricts primer utilization, perhaps by preventing interactions leading to priming complex formation, resulting in bypass of PRSs in the template. This bypass mechanism may allow leading- and lagging-strand DNA synthesis to proceed at comparable rates.

SI Materials and Methods

Protein Expression and Purification.

Gp5 (an exonuclease-deficient variant bearing aspartate-to-alanine mutations at residues 5 and 65), E. coli thioredoxin, gp2.5, and the primase domain of gp4 were purified as described (12, 19). The expression and purification of gp4 were as previously described (36) with the following modifications: E. coli BL21 (DE3) transformed with pET24-gp4A was grown in terrific broth supplemented with 30 µg/mL kanamycin, 1.5 mM MgSO4, and 0.1 mM ZnCl2 at 37 °C with vigorous agitation. After reaching an OD600 of 2, isopropyl thiogalactopyranoside was added to a final concentration of 1 mM, and the shaker temperature was lowered to 16 °C. Growth continued for 16 h, following which the purification proceeded as previously described (3). Finally, gp4 was concentrated after elution from an ATP-affinity column by anion-exchange chromatography (DEAE-FF; GE Life Sciences). Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford reagent (39). All proteins were greater than 95% pure as judged by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining.

Nucleotides.

Deoxynucleoside triphosphates were from GE Life Sciences. ATP and CTP were from Epicentre. [γ-32P] ATP, [α-32P] CTP, and [α-32P] dGTP were from Perkin-Elmer. All reagents were minimally of reagent grade.

Oligonucleotides.

Oligodeoxyribonucleotides were purchased from IDT and purified in-house by denaturing PAGE. The oligoribonucleotides AC and ACCC were purchased from Dharmacon (GE Life Sciences). The concentration of purified oligonucleotides was determined by absorbance at 260 nm using the supplied extinction coefficients. The minicircle substrate, consisting of a 70-nt circular DNA annealed to a 110-nt oligonucleotide and bearing two primase recognition sites, as well as the fork mimic substrate, was assembled as described (22, 33).

Primer Synthesis Assays.

The standard buffer condition consisted of 40 mM Hepes-KOH, pH 7.5, 50 mM K-glutamate, 5 mM DTT, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 0.3 mM dNTPs. Reactions were initiated by the addition of a final concentration of 10 mM MgCl2 and incubated at 25 °C. Multiple-turnover primer synthesis/extension assays contained 0.1 mM ATP, 0.1 mM CTP, 0.25 mCi/mL [α-32P] CTP or dGTP, 0.1 µM DNA template, and 0.1 µM gp4 hexamer (all gp4 concentrations described, except in Fig. S1, are active concentrations) and when applicable, 0.4 µM gp5/trx and 3 µM gp2.5. In the experiments described in Fig. 3, ATP was substituted by the diribonucleotide AC in the center panel, and ATP and CTP were substituted by the tetraribonucleotide ACCC in the right panel. Single-turnover primer synthesis/extension assays contained 1 nM [γ-32P] ATP, 0.5 mM CTP, 3 µM DNA template, 1.5 µM gp4 (hexamer), and when applicable, 15 µM gp5/trx, and 20 µM gp2.5.

Time courses with time points greater than 5 s were taken by manually withdrawing aliquots of the reaction mixture at the indicated times and quenching them with an equal volume of formamide loading dye [93% (vol/vol) formamide, 50 mM EDTA, 0.01% xylene cyanol, and 0.01% bromophenol blue], followed by denaturing gel electrophoresis and phosphorimaging. For rapid kinetic measurements, we used a rapid quench-flow instrument (RQF-3; KinTek). Gp4, template DNA, dNTPs, ATP, CTP, and, where applicable, gp5/trx and gp2.5 in reaction buffer were loaded in one syringe of the quench-flow apparatus. The other syringe was loaded with a solution containing MgCl2 in reaction buffer. The contents of the two syringes were mixed to start the reaction. Following the indicated incubation times, the reaction was quenched with 125 mM EDTA and 0.1% SDS, followed by analysis by denaturing gel electrophoresis and phosphorimaging. Product concentrations were determined by comparison of their phosphorimager intensity (normalized to the number of labels incorporated) to standard dilution series of radiolabeled substrate.

Coordinated DNA synthesis reactions were set up as previously described (22, 23), with the exception that 0.25 mCi/mL [α-32P] CTP was used as label. Aliquots were taken at various times and quenched with 20 mM EDTA, precipitated with ethanol, resuspended with formamide loading dye, and separated by native agarose or denaturing PAGE. DNA polymerase activity using primed M13 ssDNA was assayed as previously described (40).

Data Analysis.

The rate of product formation for multiple turnover primer synthesis reactions was determined by the initial rate method (41, 42). Product progress curves were fit using Kaleidagraph (Synergy) to a single-exponential function: , where y is the product concentration, is the reaction amplitude, is the observed rate constant, and t is time, in seconds. The slope of the tangent line at was recorded as the initial rate. The rate constant for primer synthesis, kcat, was calculated by dividing the initial rate of primer synthesis in Fig. 2A by the active enzyme concentration, operationally defined as the concentration of gp4 hexamer–DNA complex present in our experimental conditions. Fig. S1 shows that our gp4 preparation is 50.5% active and that the affinity of the gp4–DNA interaction is 50 nM. Therefore, under our conditions, the concentration of synthesis-competent enzyme, the complex of gp4 hexamer and DNA, is present at a concentration of 50 nM. Product formation for primer extension reactions was fit to either a single-exponential function (above) or to a double-exponential function: , where y is the concentration of extension product, and are the reaction amplitude for each step, and are the rate constants for the first and second step, respectively, and is time, in seconds.

Pre–steady-state primer synthesis reactions were fit to the pre–steady-state burst equation , where is the reaction amplitude, is the observed rate constant for the pre–steady-state burst, is the steady-state rate (), and is time, in seconds. Single-turnover primer synthesis reactions progress curves were fit by numerical integration (43), incorporating pre–steady-state burst and multiple-turnover primer synthesis data, to a model with three NTP condensation steps, where each intermediate was in equilibrium with the enzyme, using Kintek Explorer (Kintek). Single-turnover primer extension reactions were similarly fit with Kintek Explorer using a model consisting of two consecutive, irreversible steps. All plotted data are the average value from at least three replicates.

Discussion

Replication of the lagging strand is a complex process that requires a synergy between DNA primase, DNA helicase, DNA polymerase, and single-stranded DNA binding protein. In addition, replication of the lagging strand must be coordinated with events on the leading strand. Although great advances have been made in identifying key enzymes and steps in DNA replication, precisely how the interactions of these components are regulated at the replication fork is largely unknown.

We propose a kinetic model for the initiation of Okazaki fragments by the T7 replisome (Fig. 7A). After encountering a PRS, the primase domain of gp4 catalyzes the formation of pppAC with a rate constant of 4 s−1. This dinucleotide intermediate is in equilibrium with the enzyme, most likely explaining why the dimer is prominent in primer synthesis reactions. The dimer is extended by two rapid, consecutive NMP additions to form a tetramer. Although dissociation of trimer from gp4 is possible, its fast extension to a tetramer prevents its accumulation in the reaction. Release of tetramer from the primase active site is slow, with a rate of release of 0.1 s−1. The rate of association of tetramer to gp4 is very slow, 5 × 10−3 µM/s (calculated from the Ki of preformed tetramer on primer synthesis and the release rate; Fig. S8), making dissociation of primer from the primase domain of gp4 essentially irreversible. The molecular basis for this step, which we hypothesize involves a conformational rearrangement in the primase, is under investigation. Slow release from primase may allow efficient positioning of the polymerase or provide time for other events regulating coordination.

Fig. 7.

Key steps in lagging-strand initiation by gp4 and T7 DNA polymerase and the regulation of Okazaki fragment length by gp2.5. (A) Primers are rapidly synthesized by gp4, but their release is slow, as is their handoff to polymerase. Gp2.5 lowers the rate of primer synthesis but promotes formation of full-length primer by gp4 and assists in assembly of an extension-competent complex. After the primer/template is correctly engaged by the polymerase, DNA synthesis proceeds rapidly. (B) Gp2.5 regulates Okazaki fragment length by restricting access to PRSs and by limiting primer extension. In the absence of gp2.5, encounter of each (or many) PRS leads to primer synthesis, and release of the Okazaki fragment by the polymerase results in short Okazaki fragments. In the presence of gp2.5, most newly encountered PRSs are bypassed, leading to less frequent priming and longer Okazaki fragments. Ultimately, dissociation of gp2.5 from the template, or from the lagging-strand polymerase, occurs and a primer is extended at a new recognition site, releasing the nascent Okazaki fragment.

Fig. S8.

Primer release from gp4 is essentially irreversible. (A) Free primer synthesized by gp4, after being slowly released, could rebind the enzyme. (B) The rate of primer synthesis reactions using a single-stranded DNA template, ATP, and labeled CTP is plotted as a function of exogenously added, unlabeled ACCC primer. The inhibition constant, Ki, (20 µM) calculated with the Cheng–Prusoff equation (44) and values of [E] = 50 nM and [S]/KM = 10 are shown. (C) An estimate of the association rate constant of ACCC for gp4 can be calculated from the Ki and the dissociation (release) rate constant. This value indicates that the reassociation of a primer to gp4 is probably inefficient and proceeds very slowly, given the amount of product formed during our experimental timescale.

After synthesis, the tetraribonucleotide bound to gp4 and the template, is transferred to the DNA polymerase active site for extension. Our previous work suggests that DNA polymerase binding to gp4 occurs rapidly (19, 31). In addition, complex formation is not sufficient for primer extension (32), suggesting that the rate we observe is directly related to the formation of an extension-competent complex. In the absence of gp2.5, the measured primer extension rate constant is slow, which we attribute to inefficient positioning/engagement of the primer/template by the polymerase. In the presence of gp2.5, however, primer handoff ceases to be rate limiting, probably due to efficient formation of an extension-competent complex between gp4, DNA polymerase, and primer/template. Once the primer/template is secured by the polymerase and correctly positioned, DNA synthesis proceeds rapidly.

Our data provide a model for regulating Okazaki fragment length through limiting primer utilization (Fig. 7B). Gp4, translocating in a 5′–3′ direction, encounters a PRS and synthesizes a primer, pausing the replisome while the primer remains bound to gp4 (33–35) before its transfer to DNA polymerase. In this step, gp2.5 promotes more efficient full-length primer synthesis. The primer is handed off to T7 DNA polymerase, a slow event in the absence of gp2.5, but fast in its presence. gp2.5 likely enforces a binding orientation that enables efficient positioning of the primer on the polymerase active site. The primer is rapidly extended by T7 DNA polymerase. As the fork progresses, gp4 encounters additional PRSs. The presence of gp2.5 either masks their recognition or if primer synthesis occurs, formation of the priming complex is prevented. In either case, the lagging-strand polymerase continues extension unimpeded. In the absence of gp2.5, however, when gp4 encounters a PRS, it begins synthesis. This event retards the lagging-strand polymerase and triggers its release (35) and the eventual reformation of a priming complex, leading to a short Okazaki fragment. A high local concentration of primer synthesis products could trigger disengagement of the lagging-strand polymerase. The interplay between DNA synthesis rate and dissociation kinetics of gp2.5 from DNA, or another replisome component may lead to sporadic unmasking of PRSs. Such a scenario would allow initiation of primer synthesis and formation of a priming complex, leading to the lagging-strand polymerase dissociating from the Okazaki fragment.

Materials and Methods

Details of experimental methods are shown in SI Materials and Methods.

Protein Expression and Purification.

Proteins were purified as previously described (12, 19, 36), with a slight modification in the case of gp4 detailed in SI Materials and Methods.

Primer Synthesis Assays.

Reactions (22) were initiated by addition of a final concentration of 10 mM MgCl2 and incubated at 25 °C.

Data Analysis.

Product progress curves were fit using Kaleidagraph (Synergy) or Kintek Explorer (Kintek).

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Cifuentes-Rojas and C.C.R. laboratory members for comments, B. Zhu for WT gp2.5, and S. Moskowitz for figure preparation. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants F32GM101761 (to A.J.H.) and GM54397 (to C.C.R.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1604894113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Kornberg A, Baker TA. DNA Replication. 2nd Ed. W.H. Freeman; New York: 1992. p. xiv. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Costa A, Hood IV, Berger JM. Mechanisms for initiating cellular DNA replication. Annu Rev Biochem. 2013;82:25–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-052610-094414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balakrishnan L, Bambara RA. Okazaki fragment metabolism. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5(2):a010173. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a010173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamdan SM, Richardson CC. Motors, switches, and contacts in the replisome. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:205–243. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.072407.103248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee SJ, Richardson CC. Choreography of bacteriophage T7 DNA replication. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2011;15(5):580–586. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2011.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frick DN, Richardson CC. DNA primases. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:39–80. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mendelman LV, Notarnicola SM, Richardson CC. Roles of bacteriophage T7 gene 4 proteins in providing primase and helicase functions in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89(22):10638–10642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qimron U, Lee SJ, Hamdan SM, Richardson CC. Primer initiation and extension by T7 DNA primase. EMBO J. 2006;25(10):2199–2208. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kato M, Ito T, Wagner G, Richardson CC, Ellenberger T. Modular architecture of the bacteriophage T7 primase couples RNA primer synthesis to DNA synthesis. Mol Cell. 2003;11(5):1349–1360. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00195-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kusakabe T, Richardson CC. Gene 4 DNA primase of bacteriophage T7 mediates the annealing and extension of ribo-oligonucleotides at primase recognition sites. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(19):12446–12453. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.19.12446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakai H, Richardson CC. Dissection of RNA-primed DNA synthesis catalyzed by gene 4 protein and DNA polymerase of bacteriophage T7. Coupling of RNA primer and DNA synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1986;261(32):15217–15224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee SJ, Zhu B, Hamdan SM, Richardson CC. Mechanism of sequence-specific template binding by the DNA primase of bacteriophage T7. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(13):4372–4383. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frick DN, Baradaran K, Richardson CC. An N-terminal fragment of the gene 4 helicase/primase of bacteriophage T7 retains primase activity in the absence of helicase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(14):7957–7962. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.7957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kato M, Ito T, Wagner G, Ellenberger T. A molecular handoff between bacteriophage T7 DNA primase and T7 DNA polymerase initiates DNA synthesis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(29):30554–30562. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403485200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakai H, Richardson CC. Interactions of the DNA polymerase and gene 4 protein of bacteriophage T7. Protein-protein and protein-DNA interactions involved in RNA-primed DNA synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1986;261(32):15208–15216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frick DN, Kumar S, Richardson CC. Interaction of ribonucleoside triphosphates with the gene 4 primase of bacteriophage T7. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(50):35899–35907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.50.35899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel SS, Wong I, Johnson KA. Pre-steady-state kinetic analysis of processive DNA replication including complete characterization of an exonuclease-deficient mutant. Biochemistry. 1991;30(2):511–525. doi: 10.1021/bi00216a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuchta RD, Stengel G. Mechanism and evolution of DNA primases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1804(5):1180–1189. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamdan SM, et al. A unique loop in T7 DNA polymerase mediates the binding of helicase-primase, DNA binding protein, and processivity factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(14):5096–5101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501637102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson KA. A century of enzyme kinetic analysis, 1913 to 2013. FEBS Lett. 2013;587(17):2753–2766. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuzmic P. Application of the Van Slyke-Cullen irreversible mechanism in the analysis of enzymatic progress curves. Anal Biochem. 2009;394(2):287–289. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee J, Chastain PD, 2nd, Kusakabe T, Griffith JD, Richardson CC. Coordinated leading and lagging strand DNA synthesis on a minicircular template. Mol Cell. 1998;1(7):1001–1010. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80100-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee J, Chastain PD, 2nd, Griffith JD, Richardson CC. Lagging strand synthesis in coordinated DNA synthesis by bacteriophage t7 replication proteins. J Mol Biol. 2002;316(1):19–34. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim YT, Tabor S, Bortner C, Griffith JD, Richardson CC. Purification and characterization of the bacteriophage T7 gene 2.5 protein. A single-stranded DNA-binding protein. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(21):15022–15031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hyland EM, Rezende LF, Richardson CC. The DNA binding domain of the gene 2.5 single-stranded DNA-binding protein of bacteriophage T7. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(9):7247–7256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210605200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghosh S, Hamdan SM, Richardson CC. Two modes of interaction of the single-stranded DNA-binding protein of bacteriophage T7 with the DNA polymerase-thioredoxin complex. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(23):18103–18112. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.107656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim YT, Tabor S, Churchich JE, Richardson CC. Interactions of gene 2.5 protein and DNA polymerase of bacteriophage T7. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(21):15032–15040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mendelman LV, Richardson CC. Requirements for primer synthesis by bacteriophage T7 63-kDa gene 4 protein. Roles of template sequence and T7 56-kDa gene 4 protein. J Biol Chem. 1991;266(34):23240–23250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He ZG, Richardson CC. Effect of single-stranded DNA-binding proteins on the helicase and primase activities of the bacteriophage T7 gene 4 protein. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(21):22190–22197. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401100200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marintcheva B, Marintchev A, Wagner G, Richardson CC. Acidic C-terminal tail of the ssDNA-binding protein of bacteriophage T7 and ssDNA compete for the same binding surface. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(6):1855–1860. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711919105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamdan SM, et al. Dynamic DNA helicase-DNA polymerase interactions assure processive replication fork movement. Mol Cell. 2007;27(4):539–549. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wallen JR, Majka J, Ellenberger T. Discrete interactions between bacteriophage T7 primase-helicase and DNA polymerase drive the formation of a priming complex containing two copies of DNA polymerase. Biochemistry. 2013;52(23):4026–4036. doi: 10.1021/bi400284j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pandey M, et al. Coordinating DNA replication by means of priming loop and differential synthesis rate. Nature. 2009;462(7275):940–943. doi: 10.1038/nature08611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee JB, et al. DNA primase acts as a molecular brake in DNA replication. Nature. 2006;439(7076):621–624. doi: 10.1038/nature04317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hamdan SM, Loparo JJ, Takahashi M, Richardson CC, van Oijen AM. Dynamics of DNA replication loops reveal temporal control of lagging-strand synthesis. Nature. 2009;457(7227):336–339. doi: 10.1038/nature07512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee SJ, Richardson CC. Molecular basis for recognition of nucleoside triphosphate by gene 4 helicase of bacteriophage T7. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(41):31462–31471. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.156067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Romano LJ, Richardson CC. Characterization of the ribonucleic acid primers and the deoxyribonucleic acid product synthesized by the DNA polymerase and gene 4 protein of bacteriophage T7. J Biol Chem. 1979;254(20):10483–10489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tabor S, Richardson CC. Template recognition sequence for RNA primer synthesis by gene 4 protein of bacteriophage T7. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78(1):205–209. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.1.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tabor S, Huber HE, Richardson CC. Escherichia coli thioredoxin confers processivity on the DNA polymerase activity of the gene 5 protein of bacteriophage T7. J Biol Chem. 1987;262(33):16212–16223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cao W, De La Cruz EM. Quantitative full time course analysis of nonlinear enzyme cycling kinetics. Sci Rep. 2013;3:2658. doi: 10.1038/srep02658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang MH, Zhao KY. A simple method for determining kinetic constants of complexing inactivation at identical enzyme and inhibitor concentrations. FEBS Lett. 1997;412(3):425–428. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00771-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnson KA. Fitting enzyme kinetic data with KinTek Global Kinetic Explorer. Methods Enzymol. 2009;467:601–626. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)67023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheng Y, Prusoff WH. Relationship between the inhibition constant (K1) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem Pharmacol. 1973;22(23):3099–3108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]