Abstract

The breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene product BRCA1 is a tumor suppressor but its precise biochemical function remains unknown. The BRCA1 C-terminus acts as a transcription activation domain and germ-line cancer-predisposing mutations in this region abolish transcription activation whereas benign polymorphisms do not. These results raise the possibility that loss of transcription activation by BRCA1 is crucial for oncogenesis. Therefore, identification of residues involved in transcription activation by BRCA1 will help understand why particular germ-line missense mutations are deleterious and may provide more reliable presymptomatic risk assessment.

The BRCA1 C-terminus (aa 1560–1863) consists of two BRCT (BRCA1 C-terminal) domains preceded by a region likely to be nonglobular. We combined site-directed and random mutagenesis followed by a functional transcription assay in yeast. First, error prone PCR-induced random mutagenesis generated eight unique missense mutations causing loss of function, six of which targeted hydrophobic residues conserved in canine, mouse, rat and human BRCA1. Second, random insertion of a variable pentapeptide cassette generated 21 insertion mutants. All pentapeptide insertions N-terminal to the BRCT domains retained wild-type activity whereas insertions in the BRCT domains were, with few exceptions, deleterious. Third, site-directed mutagenesis was used to characterize five known germ-line mutations and to perform deletion analysis of the C-terminus. Deletion analysis revealed that the integrity of the most C-terminal hydrophobic cluster (I1855, L1854, and Y1853) is necessary for activity. We conclude that the integrity of the BRCT domains is crucial for transcription activation and that hydrophobic residues may be important for BRCT function. Therefore, the yeast-based assay for transcription activation can be used successfully to provide tools for structure-function analysis of BRCA1 and may form the basis of a BRCA1 functional assay.

Keywords: BRCA1, tumor suppressor gene, functional assay, breast cancer, risk assessment

INTRODUCTION

Individuals carrying mutations in the BRCA1 gene have increased risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer (1). Mutations in BRCA1 alone account for approximately 45% of families with high incidence of breast cancer and up to 80% of families with both breast and ovarian cancer (2). After an extensive search, BRCA1 was mapped to the long arm of chromosome 17 by linkage analysis (3) and was cloned by positional cloning techniques (4). Human BRCA1 codes for a 1863aa protein with no detectable similarity to known proteins with the exception of a zinc binding RING finger domain located in the N-terminal region (4), and two BRCT (BRCA1 C-terminal) domains found in a variety of proteins involved in cell cycle control and DNA repair (5–7).

Recent evidence points to the involvement of BRCA1 in two basic cellular processes: DNA repair and transcriptional regulation. BRCA1 is present in a complex containing Rad51 (8) and BRCA2 (9) and DNA damage may control BRCA1 phosphorylation and subnuclear location (10,11), strongly suggesting its involvement in the maintenance of genome integrity. Additional evidence for the role of BRCA1 in maintenance of genome integrity is provided by targeted disruption of Brca1 in the mouse. Mouse embryos lacking Brca1 are hypersensitive to γ-irradiation and cells display numerical and structural chromosomal aberrations (12).

We and others have shown that BRCA1 C-terminus has the ability to activate transcription in mammalian and yeast cells and that the introduction of germ-line disease-associated mutations, but not benign polymorphisms, abolishes this activity (13–15). BRCA1 can be copurified with the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme supporting the idea that BRCA1 is involved in transcription regulation (16,17). In addition, BRCA1 causes cell-cycle arrest via transactivation of p21WAF1/CiP1 (18) and regulates p53-dependent gene expression, acting as a coactivator for p53 (19,20). In all of these studies, the C-terminal region was necessary for activity. It is still not clear whether BRCA1 is a multifunctional protein with repair and transcription regulation functions or whether the role of BRCA1 in repair is mediated through transcription activation. In either case, these functions are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

The dearth of knowledge concerning the precise biochemical function of BRCA1 is a major hurdle in developing a functional test to provide reliable presymptomatic assessment of risk for breast and ovarian cancer. The available data derived from linkage analysis indicate that all mutations that cause premature termination (even relatively subtle mutations such as the deletion of 11 amino acids from the C-terminus) will confer high risk (21). However, a considerable number of mutations result in amino acid substitutions that, in the absence of extensive population-based studies or a functional assay, do not allow assessment of risk. Two related yeast-based assays designed to characterize mutations in BRCA1 C-terminal region have generated results that provide an excellent correlation with genetic linkage analysis (13,14,22). This led us to propose the general use of a yeast-based assay to provide functional information and a more reliable risk assessment (23).

In this paper we use site-directed and random mutagenesis to generate mutations in the BRCA1 C-terminal region that disrupt transcription activation with the intention both of defining critical residues for BRCA1 function and of deriving general rules to predict the impact of a particular mutation.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Yeast Strains

Three Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains were used in this study: HF7c [MATα, ura-3-52, his3-200, lys2-801, ade2-101, trp1-901, leu2-3, 112, gal4-542, gal80-538, LYS::GAL1-HIS3, URA3::(GAL4 17mers)3-CYC1-lacZ]; SFY526 [MATα, ura-3-52, his3-200, lys2-801, ade2-101, trp1-901, leu2-3,112, canr, gal4-542, gal80-538, URA3::GAL1-lacZ] (24) and EGY48 [MATα, ura3, trp1, his3, 6 lexA operator-LEU2] (25). HF7c has a HIS3 reporter gene under the control of the GAL1 upstream activating sequence (UAS), responsive to GAL4 transcription activation. The vectors used for expression confer growth in the absence of tryptophan (see below). The SFY526 strain has a lacZ reporter under the control of GAL1 UAS and was transformed with the GAL4 DNA binding domain (DBD) fusion. EGY48 cells were co-transformed with the LexA fusion vectors and plasmid reporters of lacZ under the control of LexA operators (see below). If the fusion proteins activate transcription, EGY48 and SFY526 yeast transformants will produce β-galactosidase and HF7c transformants will grow in medium lacking histidine.

Yeast Expression Constructs

The GAL4 DBD fusion of wild type human BRCA1 C-terminal region (aa 1560–1863) was previously described (13). Alternatively, this fragment was subcloned into the yeast expression vector pLex9 (25) in frame with the DNA binding domain of LexA. Both plasmids have TRP1 as a selectable marker, allowing growth in the absence of tryptophan. We noticed that our previously described BRCA1 (aa 1560–1863) construct (13) was made with a 3’ primer lacking a termination codon. This introduces 16 exogenous amino acids to the C-terminal region of BRCA1. We have corrected this by using primer 24ENDT (5’GCGGATCCTCAGTAGTGGCTGTGGGGGAT 3’). We compared both constructs and ascertained that qualitatively and quantitatively they have the same activity (not shown).

BRCA1 deletion mutants were generated by PCR on a BRCA1 (aa 1560–1863) context using pcBRCA1-385 (a gift from Michael Erdos, National Human Genome Research Institute) as a template and the following primers: H1860X (S9503101, 5’ CGGAATTCGAGGGAACCCCTT ACCTG 3’; S970074, 5’GCGGATCCTCAGGGGATCTGGGG 3’), P1856X (S9503101; S970073, 5’GCGGATCCTCATATCAGGTAGGTGTCC 3’), I1855X (S9503101; 1855STOP, 5’GCGGATCCTCACAGGTAGGTGTCC 3’) and L1854X (S9503101; 1854STOP, 5’GCGGATCCTCAGTAGGTGTCCAGC 3’). Mutant Y1853X corresponds to a germ-line mutation and has been previously described (13). The constructs were sequenced to verify the mutations. The PCR products were digested with EcoRI and BamHI and subcloned into similarly digested pGBT9 vectors. Alternatively, the PCR fragments were subcloned into a vector, pAS2-1 (Clontech), with higher expression levels. Introduction of additional mutations was made using the Quick-Change method. Briefly, a pair of primers encoding each mutation flanked by homologous sequence on each side was added to the wild-type plasmid pLex9 BRCA1 (aa 1560–1863) prepared in a methylation competent strain. The plasmid was amplified using Pfu polymerase (1 cycle 96°C, 30 sec and 12 cycles 96°C, 30 sec; 50°C, 1 min; 68°C, 12 min) and DpnI was added at the end of the reaction to digest the parental plasmid. The mixture was then transformed into bacteria. The following oligonucleotide primers were used: T1561I (T1561IF, 5’-CTGGAATTCGAGGGAATCCCTTACCTCGAGTCTGG-3’; T1561IR, 5’-CCAGACTCGAGGTAAGGGATTCCCTCGAATTCCAG-3’); L1564P (L1564PF, 5’-GAGGGTACCCCTTACCCGGAATCTGGAATCAG-3’; L1564PR, 5’-CTGATTCCAGATT CCGGGTAAGGGGTACCCTC-3’); D1733G (D1733GF, 5’GAAAAATGCTCAATGAGCATG GTTTTGAAGTCCGCGGAG-3’; D1733GR, 5’CTCCGCGGACTTCAAAACCATGCTC ATTCAGCATTTTTC-3’); G1738E (G1738EF, 5’GAGCATGATTTTGAAGTCAGAGAAGA TGTGGTTAACGGAAG-3’; G1738ER, 5’CTTCCGTTAACCACATCTTCTCTGACTTCAA AATCATGCTC-3’); P1806A (P1806AF, 5’-GGTACCGGTGTCCACGCAATTGTG GTTGTGCAGC-3’; P1806AR, 5’GCTGCACAACCACAATTGCGTGGACACCGGTACC 3’).

Yeast plasmid reporters

Plasmid pSH18-34 (25), a kind gift of Erica Golemis (Fox Chase Cancer Center), was used as a reporter in the LexA fusion assays. This vector has lacZ under the control of 8 LexA operators, conferring low stringency of gene expression (26).

Yeast Transformation

Competent yeast cells were obtained using the yeast transformation system (Clontech) based on lithium acetate, and cells were transformed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Filter β-galactosidase Assay

SFY526 and EGY48 transformants (several clones for each construct) were streaked on a filter overlaid on solid medium lacking tryptophan (SFY526) or tryptophan and uracil (EGY48) and allowed to grow overnight. Cells growing on the filter were lysed by freeze/thawing in liquid nitrogen, and each filter was incubated in 2.5 ml of Z buffer (16.1 g/liter Na2HPO4 7H2O, 5.5 g/liter NaH2PO4 H2O, 0.75 g/liter KCl, 0.246 g/liter MgSO4 7H2O, pH 7.2) containing 40 µl of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl β-D-galactopyranoside (X-gal) solution (20 mg/ml of X-gal in N,N-dimethylformamide) at 30°C for up to 16 hr.

Liquid β-galactosidase Assay

Liquid assays were performed as described previously (27). At least three separate transformants were assayed and each was performed at least in duplicate.

Growth Curves

HF7c transformants (several clones) containing different pGBT9 or pAS2 contructs were grown overnight in synthetic medium plus 2% dextrose (SD medium) lacking tryptophan. The saturated cultures were used to inoculate fresh medium lacking tryptophan or tryptophan and histidine to an initial OD600 of 0.0002. Cultures were grown at 30°C in the shaker and the optical density was measured at different time intervals starting at 12 hr, then every 4 hr up to 36 hr after inoculation.

Plasmid recovery from yeast cells

EGY48 transformants were grown to saturation in liquid medium lacking uracil (but in the presence of tryptophan). Cells were harvested and treated with yeast lysis solution (2% Triton X-100, 1% SDS, 100mM NaCl, 10mM Tris [pH 8.0], 1mM EDTA), phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) and 0.3 g of acid-washed beads. The sample was vortexed for 2 min, centrifuged and the supernatant precipitated with 1/10 volume of 3M NaOAc, pH 5.2 and 2.5 volumes of ethanol. Alternatively, plasmid rescue was performed as suggested by Strathern and Higgins (28).

Screening in X-Gal plates

To allow direct screening of the clones with loss of activity, EGY48 cells transformed with the mutagenized cDNAs were plated on X-Gal containing plates: 2% Galactose, 1% Raffinose, X-Gal 80 mg/L, 1× BU salts (1L of 10× BU salts: 70g Na2HPO4.7H2O, 30g NaH2PO4).

Error-prone PCR mutagenesis

A 60-cycle PCR reaction (94°C denaturation; 55°C annealing; 72°C extension) was performed using Taq polymerase and p385-BRCA1 plasmid as a template and oligonucleotide primers (S9503101, 5’-CGGAATTCGAGGGAACCCCTTACCTG-3’; S9503098, 5’-GCGGATCCGTAGTGGCTGTGGGGGAT-3’). The PCR product was gel purified and co-transformed in an equimolar ratio with a NcoI-linearized wild-type pLex9 BRCA1 (aa 1560–1863) plasmid and pSH18-34. After transformation cells were plated on X-gal plates and incubated for five days. Eighty one white and four control blue clones were recovered and re-streaked on master plates. White clones were screened again on a filter assay and the 62 clones that were consistently white were analyzed further. Plasmid DNA was recovered from the yeast cells and transformed into Escherichia coli. Miniprep DNAs from each of two bacterial transformants from the 62 candidates were re-transformed into yeast cells and tested again for β-galactosidase production. The BRCA1 inserts in plasmid DNAs generating white clones were subjected to direct sequencing using dye-terminators.

Pentapeptide scanning mutagenesis

Pentapeptide scanning mutagenesis is a technique whereby 5-amino acid insertions are introduced at random in a target protein (29). Briefly, an E. coli donor strain containing the target plasmid and pHT385, a conjugative delivery vector for transposon Tn4430, is mated with a plasmid-free E. coli recipient strain. By plating the mating mix simultaneously on antibiotics selecting for the recipient, the target plasmid, and Tn4430, transconjugants containing pHT385::target plasmid cointegrates are isolated. This cointegrate resolves rapidly in vivo, regenerating pHT385 and the target plasmid into which a copy of Tn4430 has been inserted. Tn4430 contains KpnI restriction enzyme sites located 5-bp from both ends of the transposon and duplicates 5-bp of target site sequence during transposition. By digesting the target plasmid::Tn4430 hybrid with KpnI and religating the digested DNA, the bulk of the transposon is deleted to generate a target plasmid derivative containing a 15-bp insertion. If the insertion is in a protein-encoding sequence, this will result in a 5-amino acid insertion in the target protein.

Tn4430 insertions in the C-terminal region of BRCA1 were identified either by genetic or physical means. In the former case, 30 separate matings were performed as detailed previously (30) using appropriate antibiotic selections and in which the target plasmid was pLex9 containing the BRCA1 C-terminal region fused to LexA DBD. Transconjugant colonies were harvested by washing from the mating plates and plasmid DNA was isolated from the pooled colonies. The plasmid preparations were pooled further and transformed into S. cerevisiae EGY48 harboring the pSH18-34 reporter plasmid. Transformants were tested for transcription activation by replica-plating to plates containing X-gal. Plasmid DNA was recovered from white colonies and transformed into E. coli XL1-Blue selecting on X-gal-containing plates. Plasmid DNA was isolated from white colonies (which contain only pLex9::BRCA1 C-terminal::Tn4430) and the insertion of Tn4430 into the BRCA1 C-terminal region was confirmed by restriction enzyme mapping. For the identification of Tn4430 insertions by physical means, pooled plasmid DNA from E. coli consisting of the target plasmid into which Tn4430 was inserted was digested with EcoRI and BamHI, enzymes which liberate the BRCA1 insert but do not cut Tn4430. This digestion of pooled plasmid DNA generates four fragments: the pLex9 vector backbone, the pLex9 vector containing Tn4330 insertions, the BRCA1 C-terminal fragment, and the BRCA1 C-terminal fragment containing Tn4430 insertions. The latter fragment was recovered from an agarose gel and recloned in EcoRI-BamHI-digested pLex9 to produce a library of pLex9::BRCA1 C-terminal domain plasmids containing Tn4430 insertions in the BRCA1 C-terminal region. In the case of Tn4430 insertions identified by either genetic or physical means, following further restriction mapping the bulk of Tn4430 was deleted from selected clones by digestion with KpnI and religation. The positions of the 15-bp insertions were determined by sequence analysis. 21 plasmids harboring the BRCA1 C-terminal region with 15-bp insertions were analyzed for transcription activation in S. cerevisiae EGY48 containing pSH18-34.

Western Blots

Yeast cells were grown in selective media to saturation and OD600was measured. Cells were harvested and lysed in cracking buffer (8M Urea; 5% SDS; 40 mM Tris-HCL [pH6.8]; 0.1 mM EDTA; 0.4 mg/ml bromophenol blue; use 100 µl per 7.5 total OD600) containing protease inhibitors. The samples were boiled and separated on a 10% SDS-PAGE. The gel was electroblotted on a wet apparatus to a PVDF membrane. The blots were blocked overnight with 5% skim milk using TBS-tween, and incubated with the α-pLexA (for LexA constructs) or α-GAL4 DBD (for GAL4 constructs) monoclonal antibodies (Clontech) using 0.5% BSA in TBS-tween. After four washes, the blot was incubated with the α-mouse IgG horse radish peroxidase conjugate in 1% skim milk in TBS-tween. The blots were developed using an enhanced chemiluminescent reagent (NEN, Boston, MA).

RESULTS

Germ-line mutations

We analyzed missense mutations occurring in the region from aa 1560 to aa 1863 described in the Breast Cancer Information Core database. To date, 63 missense variants representing mutations in 55 different residues have been documented, most of which have not been characterized either as disease-associated or as benign polymorphisms. Only four missense mutations have been either confirmed or considered very likely to be associated with disease: A1708E (31–33), P1749R (34), R1751Q (33) and M1775R (4,31,35). Three of these four mutations target hydrophobic residues that are conserved in canine, mouse, and rat Brca1. Amino acid composition analysis of this region reveals that only 39% of the residues are hydrophobic. Thus, although the number of characterized mutations is limited, it suggests a preference for loss-of-function mutations to target hydrophobic residues.

Mutagenesis strategies

In order to shed light on the critical residues and regions necessary for function we employed four complementary strategies: i) error-prone PCR mutagenesis followed by a screen for loss of function; ii) pentapeptide insertion mutagenesis; iii) site-directed mutagenesis to analyze documented mutations; and iv) deletion analysis of the C-terminus.

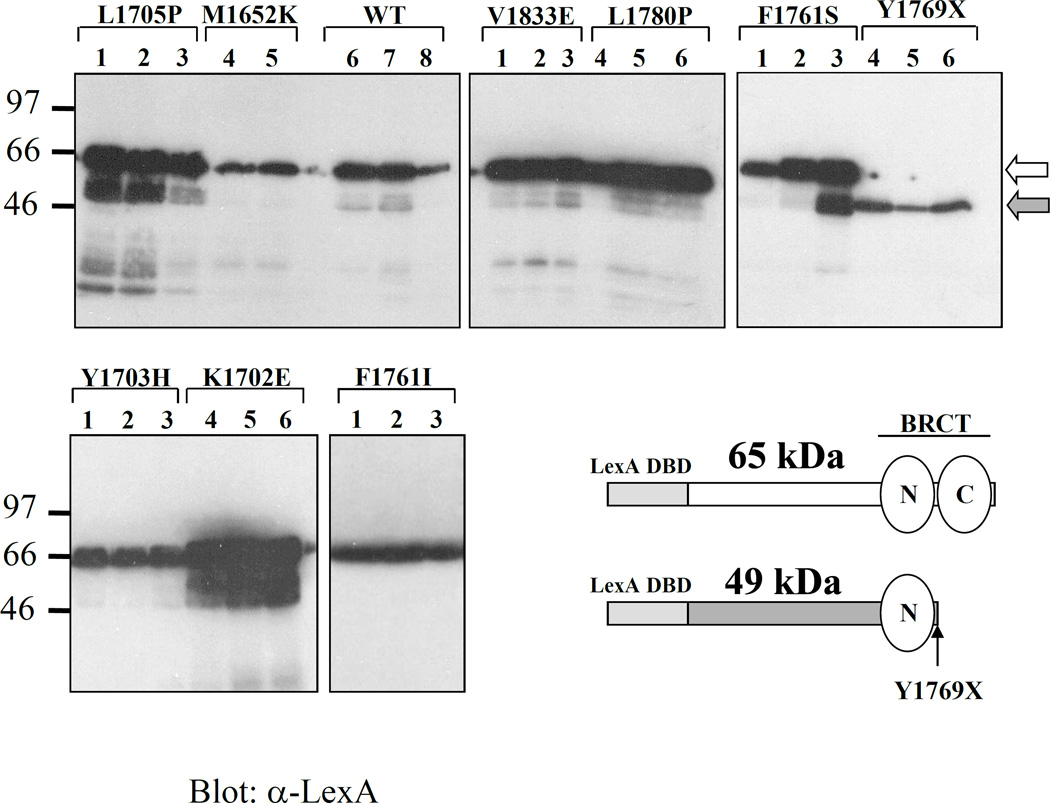

Error-prone PCR mutagenesis reveals critical residues for activation

Approximately 105 yeast clones were screened for loss of transcription activation function. 62 clones were isolated that had lost activity, most of which contained small insertions or deletions causing frameshift mutations and premature termination of the BRCA1 protein, as subsequently confirmed by SDS-PAGE and western blot analysis (not shown). Two independent clones displayed the same nonsense mutation (Y1769X). Four clones had two mutations (E1660G/M1689K; K1727R/L1786P; S1722P/N1774Y; S1715N/Q1811L), limiting their further characterization. The ten remaining clones each had a single missense mutation (one clone also had a silent mutation) and corresponded to 8 distinct mutations (Table 1). Interestingly, the screen revealed that hydrophobic residues were the major targets of mutation (six out of eight). Furthermore, all of the targeted residues are perfectly conserved in canine, mouse and rat Brca1 (Table 1). Even conservative mutations may not be well-accepted in residues that are perfectly conserved in all species. This is illustrated by mutation F1761I where a smaller hydrophobic residue is not tolerated in place of a bulkier one. Loss-of-function mutations were located primarily in the BRCT domains. In particular, mutations that occur in BRCT-C (the most C-terminal BRCT [aa 1756–1855]; BRCT-N [aa 1649–1736] is located N-terminally to BRCT-C) are in residues that constitute the hydrophobic clusters conserved in the BRCT superfamily. Western blot analysis of the mutant clones (three independent clones of each) revealed that all the mutants were expressed at levels comparable to the wild-type, ruling out the possibility that loss of function was due to instability of the protein (Figure 1). It is important to stress, however, that protein levels are relatively variable in different yeast clones carrying the same constructs and should only be taken as a rough estimate.

Table 1.

Missense mutations leading to loss of function (PCR-mediated mutagenesis screen).

| Exon | Mutation | Doga | Mouseb | Ratc | Nucleotided | Base change |

Comments and probable secondary structure elementse |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | M1652K | M | M | M | 5074 | T to A | Residue mutated in germline (M1652T, M1652I). |

| 18 | K1702E | K | K | K | 5223 | A to G | α-helix 2 of BRCT-N. |

| 18 | Y1703H | Y | Y | Y | 5226 | T to C | α-helix 2 of BRCT-N. |

| 18 | L1705P | L | L | L | 5233 | T to C | Found in two independent clones. Located just after α-helix 2 of BRCT-N. |

| 21 | F1761S | F | F | F | 5401 | T to C | BRCT-N/BRCT-C interval. |

| 21 | F1761I | F | F | F | 5400 | T to A | BRCT-N/BRCT-C interval. |

| 22 | L1780P | L | L | L | 5458 | T to C | α-helix 1 of BRCT-C. Hydrophobic residue conserved in BRCT superfamily. Mediates interaction between α-helix 1 and α- helix 3. |

| 24 | V1833E | V | V | V | 5617 | T to A | β-strand 4 of BRCT-C. Residue mutated in germ-line (V1833M) and found in two independent clones. Hydrophobic residue conserved in BRCT superfamily. |

Amino acid correspond to predicted translation from canine Brca1 cDNA deposited in GenBank accession # U50709.

Amino acid correspond to predicted translation from murine Brca1 cDNA deposited in GenBank accession # U68174.

Amino acid correspond to predicted translation from rat Brca1 cDNA deposited in GenBank accession # AF036760.

Nucleotide numbering corresponds to human BRCA1 cDNA deposited in GenBank accession #U14680.

According to a BRCA1 BRCT model from ref. 36.

Figure 1. Expression levels of loss-of-function BRCA1 mutants.

Cell lysates containing comparable cell numbers were separated on SDS-PAGE. At least two independent transformants were assayed for each mutant to control for clonal variation. LexA fusion mutant proteins expressed in yeast were detected by western blot using a monoclonal α-LexA antibody. A schematic representation of the fusion proteins bearing missense mutations (white arrow; M.W. 65 kDa) and a nonsense mutation (gray arrow; M.W. 49 kDa) is shown. Note that mutation Y1769X disrupts the BRCT-C but retains BRCT-N.

Pentapeptide scanning mutagenesis reveals buried regions necessary for activity

The BRCA1 C-terminal region was subjected to pentapeptide scanning mutagenesis in which a variable, five amino acid cassette was introduced at random. The resulting set of mutated proteins included mutants that displayed complete loss of activity, mutants with reduced activity, and mutants with similar or higher activity than wild type. Table 2 groups the insertions by location. The first group includes mutations in the region N-terminal to the BRCT domains (aa 1560–1649); the second group contains mutations in BRCT-N while the third group includes mutations in the intervening region between BRCT-N and BRCT-C. The last group includes mutations in BRCT-C. None of the insertions N-terminal to the BRCT domains had a negative effect on transcription activation. Also, insertions in the interval between the BRCT domains or at its boundary (1723RGTPI) had generally less drastic effects. In contrast, all insertions within BRCT-N and several within BRCT-C had a more severe effect. It is clear that BRCT-C tolerates insertions better (only three out of five showed loss of activity) than BRCT-N (all mutations reduced activity with six out of seven showing drastic impairment). The difficulty in predicting the outcome of mutations can be well exemplified by mutations 1824GGTPI and 1822GVPLH. Both of these mutations target residues at the end of BRCT-C α-helix 2, do not change the net charge of the protein, and are only two residues apart. However, 1822GVPLH has approximately 6% of the wild-type activity, whereas 1824GGTPI has an activity approximately 80% higher than wild type. Interestingly, the 1793GVPLK insertion increased transcriptional activation approximately four-fold suggesting that this region of BRCA1 may directly contact a component of the transcription machinery. The pentapeptide mutagenesis results demonstrated that, in addition to substitution mutations, insertion mutagenesis in the C-terminal region, particularly in the BRCT domains, can profoundly alter transcriptional activity by BRCA1.

Table 2.

Transcriptional activity of insertion mutants.

| Pentapeptide Insertion |

Miller Unitsa | Probable secondary structure elementb |

|---|---|---|

| empty vector | 4.1 ± 3.0 | - |

| wild-type | 99.9 ± 14.1 | - |

| 1571SEGYP | 98.2 ± 98.2 | unknown |

| 1578PSGVP | 120.1 ± 52.6 | unknown |

| 1602PQGVP | 99.3 ± 15.9 | unknown |

| 1620DRGTP | 127.1 ± 11.0 | unknown |

| 1625NGVPH | 81.7 ± 8.2 | unknown |

| 1627MGVPP | 94.4 ± 6.8 | unknown |

| 1665stop | 1.6 ± 0.1 | α-helix 1 of BRCT-N |

| 1676RGTPL | 2.5 ± 0.2 | β-strand 2 of BRCT-N |

| 1678RGTPN | 0.7 ± 0.2 | β-strand 2 boundary of BRCT-N |

| 1695GVPQF | 4.3 ± 1.1 | β-strand 3/α-helix 2 loop of BRCT-N |

| 1709GGTPG | 1.0 ± 0.7 | α-helix 2/β-strand 4 loop of BRCT-N |

| 1717WGTPF | 2.1 ± 0.4 | α-helix 3 of BRCT-N |

| 1723RGTPI | 36.5 ± 15.0 | α-helix 3 boundary of BRCT-N |

| 1724GVPLK | 10.4 ± 2.5 | BRCT-N/BRCT-C interval |

| 1730GVPLN | 57.7 ± 7.2 | BRCT-N/BRCT-C interval |

| 1737GVPLR | 1.0 ± 0.5 | BRCT-N/BRCT-C interval |

| 1769GGYPY | 11.7 ± 11.1 | β-strand 1/α-helix 1 loop of BRCT-C |

| 1780GVPQL | 0.8 ± 0.3 | α-helix 1 of BRCT-C |

| 1793GVPLK | 372.9 ± 113.8 | β-strand 2/β-strand 3 turn of BRCT-C |

| 1822GVPLH | 5.7 ± 0.5 | α-helix 2 of BRCT-C |

| 1824GGTPI | 178.0 ± 34.4 | α-helix 2 boundary of BRCT-C |

Mutants in bold displayed activity equal to or higher than wild-type.

According to a BRCA1 BRCT model from ref. 36.

Characterization of germ-line mutations

In order to assess the activity of variants that have already been documented but not characterized, we decided to introduce a set of mutations and assay for transcription activation in yeast (Table 3). Mutations T1561I and L1564P are both located in the region preceding the BRCT domains and displayed wild-type activity. L1564P was expected to be a polymorphism since proline is the residue found in the rat Brca1 sequence. The three remaining variants are localized to the BRCT domains. Two variants, D1733G and P1806A, displayed wild-type activity and are suggested to be benign polymorphisms. D1733G introduces a glycine that probably does not affect BRCT structure. P1806A involves a conservative change and it is important to note that the rat Brca1 sequence has leucine in that position. Only one of the variants tested, G1738E displayed a loss of function phenotype. Thus, we propose that G1738E is a disease-predisposing variant.

Table 3.

Transcriptional activity of human BRCA1 unclassified variants (aa 1560–1863).

| Exon | Mutation | Activitya | Dogb | Mousec | Ratd | Nucleotidee | Base change |

Probable secondary structure elementf | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | T1561I | + | A | T | T | 4801 | C to T | unknown | Durocher et al 1996 (41) |

| 16 | L1564P | + | L | L | P | 4810 | T to C | unknown | BICg |

| 20 | D1733G | + | D | E | E | 5317 | A to G | BRCT-N/BRCT-C interval | BIC |

| 20 | G1738E | − | G | G | G | 5332 | G to A | BRCT-N/BRCT-C interval | BIC |

| 23 | P1806A | + | P | P | L | 5535 | C to G | β-strand 2/β-strand 3 loop of BRCT-C | BIC |

At least ten independent clones were assayed and scored 8 hours after addition of X-gal. +: blue with same intensity as wild-type control. −: white, similar to two (F1761S; Y1769X) loss-of-function controls.

Amino acid correspond to predicted translation from canine Brca1 cDNA deposited in GenBank accession # U50709.

Amino acid correspond to predicted translation from murine Brca1 cDNA deposited in GenBank accession # U68174.

Amino acid correspond to predicted translation from rat Brca1 cDNA deposited in GenBank accession # AF036760.

Nucleotide numbering corresponds to human BRCA1 cDNA deposited in GenBank accession #U14680.

According to a BRCA1 BRCT model from ref. 36.

Breast Cancer Information Core.

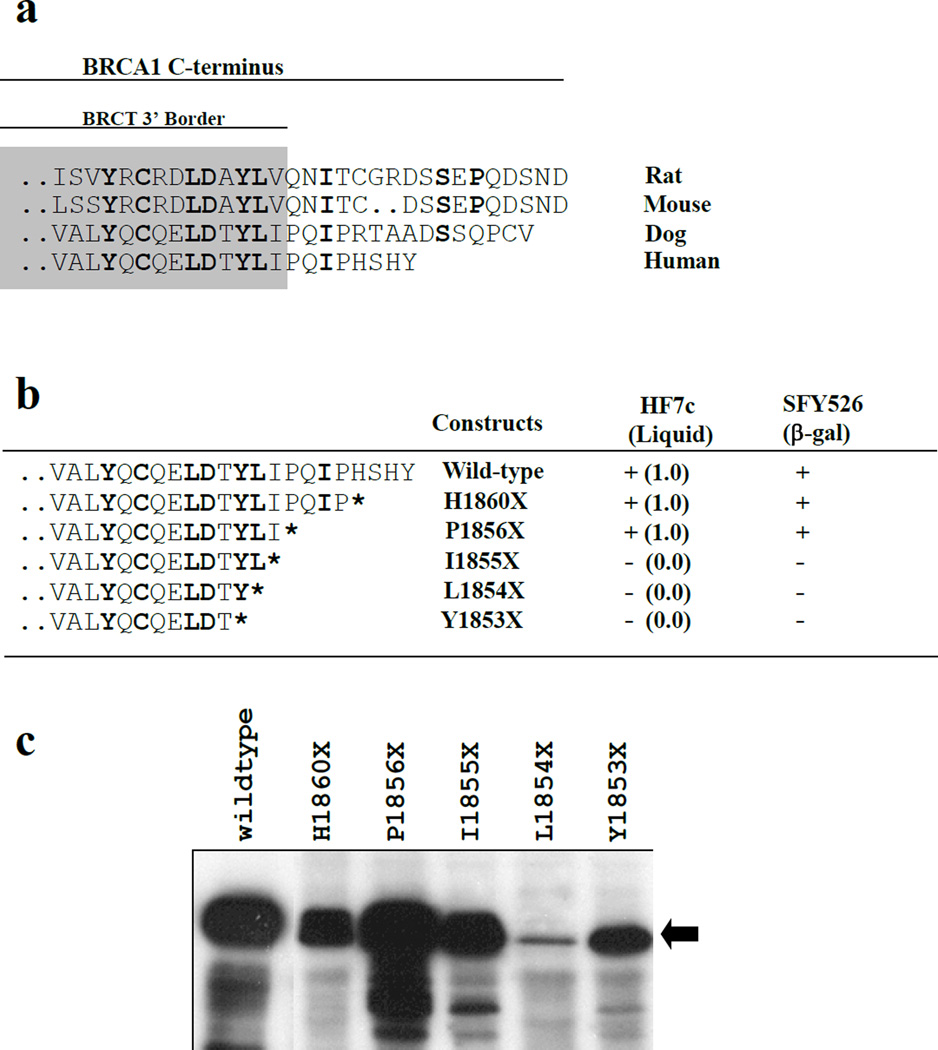

Deletion mutants of C-terminal residues define the Minimal Transactivation Domain (MTD)

A construct carrying the germ-line mutation Y1853X does not have detectable transcriptional activity in the context of a GAL4 DBD fusion of BRCA1 C-terminus (aa 1560–1863)(13,15). A construct containing aa 1760–1863 can be considered the MTD, defining I1760 as a 5’ border of this domain (13,15). Thus, the N-terminal border of the MTD coincides closely with the N-terminal border of BRCT-C (I1760 is the first conserved hydrophobic residue in the BRCT superfamily). In order to identify the C-terminal border of the MTD several deletion mutants were made in the aa 1560–1863 context and assayed for their ability to activate transcription in yeast. Figure 2 shows the several deletion mutants analyzed aligned to mouse, rat, dog and human BRCA1 wild-type sequences. Mutant H1860X introduces a stop codon but maintains all of the conserved amino acids in canine and human BRCA1. P1856X maintains the hydrophobic residues which are conserved in all of the BRCT domains described in several species. I1855X and L1854X delete one and two conserved hydrophobic residues respectively. Y1853X is a mutation found in the germ-line of breast and ovarian cancer patients in high risk families (21). These constructs were transformed into SFY526 and HF7c and analyzed for their ability to activate different reporters (Figure 2b). Activity comparable to the wild-type was obtained with mutants H1860X and P1856X. However, mutations that disrupted the conserved hydrophobic residues (I1855X and L1854X) at the end of the BRCT domain abolished activity. Therefore we define the MTD in BRCA1 as aa 1760–1855. To determine whether the loss of activity by the mutants correlated with the stability of the protein, yeast cells were transformed with the same mutated alleles in a vector conferring high expression (pAS2-1). Transcriptional activity using these constructs (in pAS2-1 backbone) was measured and results were similar with I1855X showing some residual activity. Expression was highly variable and mutants were in general expressed at lower levels than wild type (Figure 2c). There was no correlation between loss of activity and lower levels of expression since the transcriptionally active mutant H1860X was expressed at levels lower or comparable to transcriptionally inactive mutants I1855X and Y1853X (Figure 2c).

Figure 2. Deletion analysis of the C-terminal region.

A. Alignement of the wild-type sequences of the C-terminus of rat, mouse, dog and human BRCA1. Amino acids in bold represent conserved residues. The shaded area corresponds to residues at the 3’ border of the BRCT-C domain. B. Transcriptional activity of GAL4 DBD fusion deletion constructs, made in the context of BRCA1 aa 1560–1863. S. cerevisiae (HF7c) carrying the indicated fusion proteins were assayed for growth in the absence of tryptophan and histidine in liquid medium. Activity relative to cells growing in medium lacking tryptophan alone after 36 hours is shown in parenthesis. Filter β-galactosidase assays for SFY526 were scored at 12 hours after X-gal addition. At least 4 independent clones were assayed for each construct. C. Western blot showing levels of protein expression of the different constructs (black arrow) detected by a α-GAL4-DBD monoclonal antibody.

DISCUSSION

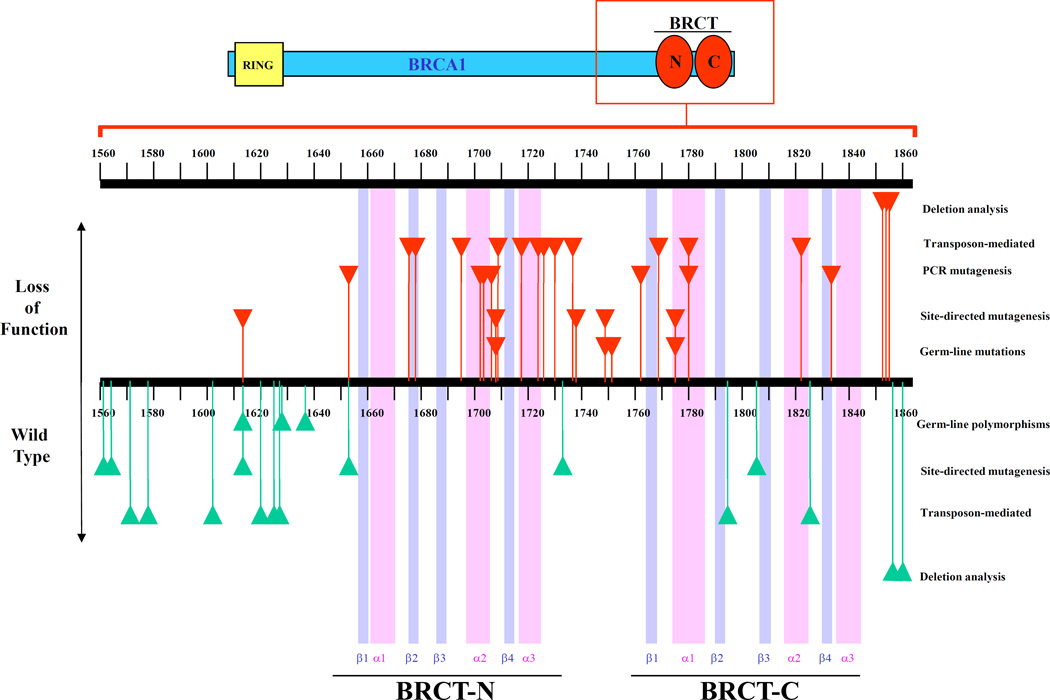

In this paper we describe an extensive mutagenesis analysis of BRCA1 C-terminal region and partly define the critical requirements for transcriptional activity by BRCA1. Four complementary strategies were employed: i) error-prone PCR mutagenesis followed by a screen for loss of function; ii) pentapeptide scanning mutagenesis; iii) site-directed mutagenesis to analyze documented mutations; and iv) deletion analysis of the C-terminus. Our results support the notion that there are no particular hot spots for loss-of-function mutations but rather that these mutations are scattered throughout the coding sequence. Nevertheless, we were able to identify preferential sites critical for activation. An overview of the mutations and their effects is presented in Figure 3. First, we discuss the general conclusion of each strategy and then we analyze the possible structural outcome of the mutations based on the crystal structure of XRCC1 BRCT (36).

Figure 3. Domain structure of BRCA1 C-terminal region (aa 1560–1863) and characterized mutations.

Top panel shows a schematic representation of full length BRCA1 protein featuring the RING domain (yellow box) in the N-terminal region and the BRCT domains (red circles) in the C-terminal region. The region analyzed in this study is contained in the red box which is enlarged and represented in the bottom panel. Purple and pink bars represent predicted β-strands and α-helices, respectively. Secondary structure predictions were made by Zhang et al. (36) based on the crystal structure of XRCC1 BRCT domain. Mutations represented on the upper part (red triangles) result in loss of function whereas mutations on the lower part (green triangles) result in activity equal or higher than wild-type. Germ-line mutations and polymorphisms are variants defined by genetic linkage to be disease-associated and benign polymorphisms, respectively. Site-directed mutagenesis, PCR mutagenesis, transposon-mediated mutagenesis and deletion analysis represent mutations that have been characterized by transcription activation assay in yeast to be either loss of function (upper part) or wild-type (lower part).

Error-prone PCR mutagenesis

Eight distinct BRCA1 mutations were recovered which resulted in loss of transcription activation function. In the course of the screening procedure, many additional clones which displayed a light blue color were noted and were probably mutants with reduced function but only clones with complete loss of function were analyzed further. No PCR-generated mutations were found in the region external to the BRCT domains even though this constitutes approximately 1/3 of the tested sequence, indicating a preference for mutations which affect transcription activation to occur in the BRCT domains (Figure 3).

Six out of eight unique PCR-generated mutations were in hydrophobic residues conserved in human, canine, mouse and rat Brca1 (6,7) supporting the notion that hydrophobic residues are important for the stability of the BRCT domains and BRCA1 function in vivo.

Pentapeptide scanning mutagenesis

Pentapeptide scanning mutagenesis is a method by which a variable five amino acid cassette is introduced at random into a target protein (29,30,37). This approach differs from error-prone mutagenesis since clones are not selected for loss of activity but rather mutations are analyzed only after they have been generated. Therefore, mutants with gain of function, loss of function, and novel activities can be produced (30,37). Moreover, it has been shown that insertion is essentially random (29). The results obtained are in agreement with the PCR-mediated mutagenesis in that the region N-terminal to the BRCT domains (aa 1560–1649) seems to be more tolerant of mutation: none of six different pentapeptide insertions in this region affected transcription activation. The fact that derivatives containing insertion mutations in this region retained wild-type activity suggests that this region is non-globular and is probably a flexible part of the C-terminal region without many critical secondary structure elements. In fact, the region encompassing aa 1524–1661 is predicted to be non-globular (5). The pentapeptide mutagenesis results also suggest that changing the net charge of the protein does not necessarily correlate with an alteration in transcription activity, as would be expected for classical acidic activators (38), since 1793GVPLK (which adds a positive charge) shows a four-fold increase in activity. Interestingly, only four out of the 63 C-terminal germ-line variants involve non-conservative substitutions in acidic residues, thought to be important for activation, suggesting that, contrary to initial predictions, BRCA1 may not be a classical acidic activator (4). The 1793GVPLK mutation which is hyperactive for transcription activation may define a point of contact between the BRCA1 C-terminal region and the transcription machinery.

Deletion analysis

Our analysis demonstrates that residues C-terminal to aa 1855 are dispensable for activation, consistent with the extreme evolutionary divergence of those residues (Figure 2)(39,40). The results also underscore the importance of the last hydrophobic cluster in the sequence (YLI for human and canine, YLV for mouse and rat) and provide a plausible explanation for the complete loss of function (in vitro and in vivo) of Y1853X alleles.

Site directed mutagenesis

Only one out of five germ-line mutations analyzed displayed loss of function, suggesting that a large part of variants in the C-terminal region will probably be benign polymorphisms, including some variants found in the BRCT domains. Very little data is available at this moment to confirm or contradict the results obtained. In particular, T1561I illustrates the difficulties involved in predicting outcome from population data. T1561I was found in one affected individual but not in control individuals (41). This could suggest that T1561I is a disease-predisposing variant. However, although found as a germ-line mutation it was absent from the tumor from the same patient (see 41), indicating that this mutation is a benign polymorphism.

Structural basis for effects of BRCA1 C-terminal domain mutations

The C-terminal BRCT domain of XRCC1 consists of a four-stranded parallel β-sheet (β1–β4) surrounded by three α-helices (α1–α3) (36). The β-sheet forms the core of the structure with a pair of α-helices (β1 and β3) on one side of the β-sheet and the remaining β-helix (β2) on the other side. A model of the more C-terminal BRCT domain of BRCA1 has been constructed based on the crystal structure of the BRCT domain of XRCC1 (36). This model allows an interpretation of the effect of some of the mutations described in this study (Tables 1, 2 and 3) on BRCT domain structure (Figure 3).

The position of the M1652K mutation corresponds to a position (Asp4) in the XRCC1 structure which is thought to form a salt bridge at the BRCT dimer interface (36). While M1652 would not be expected to be involved in salt bridge formation at neutral pH, residues in this region nevertheless may also be involved in homo- or heterodimer formation in BRCA1.

Missense mutations at positions 1702, 1703, and 1705 of the BRCT-N domain and a pentapeptide insertion at position 1822 of the BRCT-C domain abolish transcription activation by the BRCA1 C-terminus (Tables 1 and 2). These mutations are predicted to occur in a region of highly variable length and composition which encompasses helix α2 in BRCT domains (36). It was suggested that this variability indicated that this region was not involved in formation of the core fold of the BRCT domain (36). Nevertheless, the mutations isolated here reveal that this region of the BRCT domains is critical for the transcription activation function of the BRCA1 C-terminus.

Residue F6 forms part of a highly conserved hydrophobic pocket centered on residue W74 in helix α3 in the C-terminal BRCT domain of XRCC1 (36). Mutations at the corresponding position (F1761) in the BRCT-C domain of BRCA1 abolish transcription activation (Table 1). By analogy with XRCC1, residue F1761 of BRCA1 is also predicted to form part of a hydrophobic pocket whose disruption by mutation may compromise correct BRCT domain folding. In contrast, residue L25 is implicated in the interactions between helices α1 and α3 which form a paired helical bundle in the three-dimensional structure of the BRCT domain of XRCC1 (36). A missense mutation of the corresponding residue (L1780) or a pentapeptide insertion at this position in the BRCT-C domain of BRCA1 abolish transcription activation by the BRCA1 C-terminal region (Tables 1 and 2). These mutations are likely to affect the interactions between helices α1 and α3 thereby destabilising BRCT domain structure. Two other missense mutations in the BRCT-C domain, P1806A and V1833E were shown, respectively, to display wildtype activity and to abolish transcription activation (Table 1 and 3). Interestingly, P1806A is predicted to have no obvious effect on the structure while a less drastic mutation at position V1833 (to methionine) has been predicted to destabilise the fold of the domain (36) suggesting that V1833E will behave similarly.

Pentapeptide insertions in many of the predicted secondary structure elements in the C-terminal region of BRCA1 abolish transcription activation (Table 1 and Fig. 3). Some of these insertions are likely to disrupt formation of the correct BRCT domain core fold, e.g., insertions in strand β2 (1676RGTPL), and in helices α2 (1822GVPLH) and α3 (1717WGTPF). In contrast, the 1780GVPQL insertion in helix α1 is predicted to be at the BRCT dimer interface and thereby may affect the association of this domain with another protein, e.g., RNA helicase A which interacts with BRCA1 through residues in helix α1 (17).

Different roles of BRCT-N and BRCT-C

Our insertion mutagenesis results suggest that BRCT-C can tolerate insertions better than BRCT-N without affecting transcription activation function. In addition, BRCT-N is more highly conserved in other species than is BRCT-C (39,40) suggesting a higher constraint for function. The BRCT-N seems to be very important for binding to RNA helicase A (17) even though it seems to lack an independent activation domain (mutant Y1769X is inactive). The borders of BRCT-C coincide well with the limits of the MTD, but only in combination with BRCT-N are high levels of activation achieved (13). It is tempting to speculate that BRCT-N is involved in the interaction of BRCA1 with RNA helicase A and is responsible for presenting BRCT-C in a correct way to obtain a transcriptionally competent activator.

Functional assay

We have performed an extensive analysis of the BRCA1 C-terminal region (aa 1560–1863) and have found that there is a correlation between loss of transcription activation function and the human genetic data suggesting that the assay could be used to predict the effect of missense mutations in this region. Although the effects of mutations on transcriptional activity have been found to be comparable in yeast and mammalian cells (13,15) it is possible that the effect of some mutations may be evident only in mammalian cells, e.g., due to an interaction with mammalian-specific regulators, raising the possibility of a misintrepretation of the data obtained in yeast.

In the results presented here for substitution mutations we have used a reporter gene with relatively low stringency (8 Lex operators)(26). The rationale for this choice was to recover only mutants that cause dramatic reduction or complete loss of activity. Mutations that partially disrupt the function would still activate the reporter. In the absence of knowledge of the minimum in vivo threshold of transcription activity needed for tumor suppression, it would be inappropriate to make decisions on whether a particular mutations would represent a wild type or a cancer predisposing allele. For example, a particular mutation that shows 50% loss of activity in yeast could still be perfectly functional in breast and ovarian cells.

Conclusion

The data presented here suggest that the yeast assay for monitoring transcription activation by BRCA1 will provide a wealth of functional information in a research setting. That includes identifying protein-protein interaction regions, defining critical residues for activity and providing tools to identify possible regulators. A general use of the assay to help in risk assessment and providing information for clinical decisions must await further confirmation from population-based studies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert Coyne and Åke Borg for communicating results prior to publication and Eugene Koonin and Jeff Humphrey for helpful discussion. We would also like to acknowledge the excellent technical help from Jeremy Medalle and the staff of the Rockefeller University sequencing core facility and Hina Abidi for help with the constructs. This work was supported by the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor, the Irving Weinstein and the Lee Kaplan Cancer foundations. Work by FH was initiated while the recipient of Wellcome Trust Research Career Development Fellowship 040822/Z/94/Z in the Department of Biochemistry, University of Oxford, Oxford.

Footnotes

ELECTRONIC-DATABASE INFORMATION

Breast Cancer Information Core, http://www.nhgri.nih.gov/Intramural_research/Lab_transfer/Bic/

REFERENCES

- 1.Smith SA, Easton DG, Evans DGR, Ponder BAJ. Allele losses in the region 17q12-21 in familial breast cancer involve the wild type chromosome. Nature Genet. 1992;2:128–131. doi: 10.1038/ng1092-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Easton DF, Bishop DT, Ford D, Crockford GP Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Genetic linkage analysis in familial breast and ovarian cancer: results from 214 families. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1993;52:678–701. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hall JM, Lee MK, Newman B, Morrow JE, Anderson LA, Huey B, King MC. Linkage of early-onset familial breast cancer to chromosome 17q21. Science. 1990;250:1684–1689. doi: 10.1126/science.2270482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miki Y, Swensen J, Shattuck-Eidens D, Futreal PA, Harshman K, Tavtigian S, Liu Q, et al. A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1. Science. 1994;266:66–71. doi: 10.1126/science.7545954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koonin EV, Altschul SF, Bork P. Functional Motifs. Nature Genet. 1996;13:266–267. doi: 10.1038/ng0796-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bork P, Hofmann K, Bucher P, Neuwald AF, Altschul SF, Koonin EV. A superfamily of conserved domains in DNA damage-responsive cell cycle checkpoint proteins. FASEB J. 1997;11:68–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Callebaut I, Mornon JP. From BRCA1 to RAP1: a widespread BRCT module closely associated with DNA repair. FEBS Letters. 1997;400:25–30. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01312-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scully R, Chen J, Plug A, Xiao Y, Weaver D, Feunteun J, Ashley T, et al. Association of BRCA1 with Rad51 in mitotic and meiotic cells. Cell. 1997;88:265–275. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81847-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen J, Silver DP, Walpita D, Cantor SB, Gazdar AF, Tomlinsom G, Couch F, et al. Stable interaction between the products of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 tumor suppressor genes in mitotic and meiotic cells. Mol. Cell. 1998;2:317–328. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80276-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scully R, Chen J, Ochs RL, Keegan K, Hoekstra M, Feunteun J, Livingston DM. Dynamic changes of BRCA1 subnuclear location and phosphorylation state are initiated by DNA damage. Cell. 1997;90:425–435. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80503-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas JE, Smith M, Tonkinson JL, Rubinfeld B, Polakis P. Induction of phosphorylation on BRCA1 during the cell cycle and after DNA damage. Cell Growth & Diff. 1997;8:801–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shen SX, Weaver Z, Xu X, Li C, Weinstein M, Chen L, Guan XY, et al. A targeted disruption of the murine Brca1 gene causes γ-irradiation hypersensitivity and genetic instability. Oncogene. 1998;17:3115–3124. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monteiro ANA, August A, Hanafusa H. Evidence for a transcriptional activation function of BRCA1 C-terminal region. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:13595–13599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monteiro ANA, August A, Hanafusa H. Common variants of BRCA1 and transcription activation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1997;61:761–762. doi: 10.1086/515515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chapman MS, Verma IM. Transcription activation by BRCA1. Nature. 1996;382:678–679. doi: 10.1038/382678a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scully R, Anderson SF, Chao DM, Wei W, Ye L, Young RA, Livingston DM, et al. BRCA1 is a component of the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:5605–5610. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson SF, Schlegel BP, Nakajima T, Wolpin ES, Parvin JD. BRCA1 protein is linked to the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme complex via RNA helicase A. Nature Genet. 1998;19:254–256. doi: 10.1038/930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Somasundaram K, Zhang H, Zeng YX, Houvras Y, Peng Y, Zhang H, Wu GS, et al. Arrest of the cell-cycle by the tumor suppressor BRCA1 requires the CDK-inhibitor p21Waf1/CiP1 . Nature. 1997;389:187–190. doi: 10.1038/38291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ouchi T, Monteiro ANA, August A, Aaronson SA, Hanafusa H. BRCA1 regulates p53-dependent gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:2302–2306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang H, Somasundaram K, Peng Y, Tian H, Zhang H, Bi D, Weber BL, et al. BRCA1 physically associates with p53 and stimulates its transcriptional activity. Oncogene. 1998;16:1713–1721. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friedman LS, Ostermeyer EA, Szabo C, Dowd P, Lynch ED, Rowell SE, King MC. Confirmation of BRCA1 by analysis of germline mutations linked to breast and ovarian cancer in ten families. Nature Genet. 1994;8:399–404. doi: 10.1038/ng1294-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Humphrey JS, Salim A, Erdos MR, Collins FS, Brody LC, Klausner RD. Human BRCA1 inhibits growth in yeast: potential use in diagnostic testing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:5820–5825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monteiro ANA, Humphrey JS. Yeast-based assays for detection and characterization of mutations in BRCA1. Breast Disease. 1998;10:61–70. doi: 10.3233/bd-1998-101-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bartel PL, Chien CT, Sternglanz R, Fields S. Elimination of false positives that arise in using the two-hybrid system. BioTechniques. 1993;14:920–924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Golemis EA, Gyuris J, Brent R. Two-hybrid system/interaction traps, p. 13.14.1–13.14.17. In: Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston R, Moore D, Seidman J, Smith JA, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Estojak J, Bren R, Golemis EA. Correlation of two-hybrid affinity data with in vitro measurements. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1995;15:5820–5829. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.10.5820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brent R, Ptashne M. A eukaryotic transcriptional activator bearing the DNA specificity of a prokaryotic repressor. Cell. 1985;43:729–736. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90246-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strathern JN, Higgins DR. Recovery of plasmids from yeast into Escherichia coli: shuttle vectors. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:319–329. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hallet B, Sherratt DJ, Hayes F. Pentapeptide scanning mutagenesis: random insertion of a variable five amino acid cassette in a target protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:1866–1867. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.9.1866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayes F, Hallet B, Cao Y. Insertion mutagenesis as a tool in the modification of protein function: extended substrate specificity conferred by pentapeptide insertions in the Ω-loop of TEM-1 β-lactamase. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:28833–28836. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.46.28833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Futreal PA, Liu Q, Shattuck-Eidens D, Cochran C, Harshman K, Tavtigian S, Bennett LM, Haugen-Strano A, et al. BRCA1 mutations in primary breast and ovarian carcinomas. Science. 1994;266:120–122. doi: 10.1126/science.7939630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shattuck-Eidens D, McClure M, Simard J, Labrie F, Narod S, Couch F, Weber B, et al. A collaborative study of 80 mutations in BRCA1 breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene: implications for presymptomatic testing and screening. JAMA. 1995;273:535–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stoppa-Lyonet D, Laurent-Puig P, Essioux L, Pagès S, Ithier G, Ligot L, Fourquet A, et al. BRCA1 sequence variations in 160 individuals referred to a breast/ovarian family cancer clinic. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1997;60:1021–1030. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gayther SA, Harrington PA, Russell PA, Kharkevich G, Gargavtseva RF, Ponder BAJ the UKCCCR Familial Ovarian Cancer Study group. Rapid detection of regionally clustered germ-line BRCA1 mutations by multiplex heteroduplex analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1996;58:451–456. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Szabo CI, King MC. Inherited breast and ovarian cancer. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1995;4:1811–1817. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.suppl_1.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang X, Moréra S, Bates PA, Whitehead PC, Coffer AI, Hainbucher K, Nash RA, et al. Structure of an XRCC1 BRCT domain: a new protein-protein interaction module. EMBO. J. 1998;17:6404–6411. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.21.6404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cao Y, Hallet B, Sherratt DJ, Hayes F. Structure-function correlations in the XerD site-specific recombinase revealed by pentapeptide scanning mutagenesis. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;274:39–53. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gill G, Ptashne M. Mutants of GAL4 protein altered in an activation function. Cell. 1987;51:121–126. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Szabo CI, Wagner LA, Francisco LV, Roach JC, Argonza R, King MC, Ostrander EA. Human, canine and murine BRCA1 genes: sequence comparison among species. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1996;5:1289–1298. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.9.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bennett LM, Brownlee HA, Hagavik S, Wiseman RW. Sequence analysis of the rat brca1 homolog and its promoter region. Mamm. Genome. 1999;10:19–25. doi: 10.1007/s003359900935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Durocher F, Shattuck-Eidens D, McClure M, Labrie F, Skolnick MH, Goldgar DE, Simard J. Comparison of BRCA1 polymorphisms, rare sequence variants and/or missense mutations in unaffected and breast/ovarian cancer populations. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1996;5:835–842. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.6.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]