Abstract

Stress-response biologic systems are altered in alcohol-dependent individuals. Early life stress (ELS) is associated with a heightened risk of alcohol-dependence, presumably due to stress-induced neuroplastic changes. This study was designed to assess the contribution of ELS to a stress-induced neural response in alcohol-dependent participants. Fifteen alcohol-dependent men abstinent for 3–5 weeks and 15 age- and race-matched healthy controls were studied. Anticipatory anxiety was induced by a conditioned stimulus paired with an uncertain physically painful unconditioned stressor. Neural response was assessed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. ELS was assessed with the Childhood Adversity Interview (CAI). There was a significant interaction between ELS and group on Blood Oxygen Level-Dependent (BOLD) amplitude during anticipatory anxiety in the right amygdala and bilateral orbitofrontal cortex, posterior putamen, and insula. Higher ELS scores were associated with decreased BOLD amplitude during anticipatory anxiety in alcohol-dependent, but not control, participants. These findings suggest that ELS interacts with alcohol dependence to induce a muted cortico-striatal response to high threat stimuli. Allostatic changes due to both ELS and excessive alcohol use may jointly induce persistent changes in the neural response to acute stressors.

Keywords: alcoholism, brain imaging, childhood adversity, maltreatment, functional magnetic resonance imaging, striatum

INTRODUCTION

Stressful life events play a critical role in the development, onset, and persistence of alcohol use disorders (Keyes et al., 2012). These life events can vary from prolonged, adverse experiences, such as a chronic illness or significant loss (i.e. adversity) to life-threatening events (i.e., trauma). The experience of ELS poses a particularly significant risk for the development of an alcohol use disorder later in life (Brady and Back, 2012) and may worsen the severity of the disorder (Eames et al., in press). This heightened susceptibility to the consequences of ELS is a result, at least in part, of the immature status of a child’s emotional and cognitive regulatory functions (Schumacher et al., 2006). The child’s peripheral and central nervous system is subsequently particularly vulnerable to the neuroplastic changes induced by persistent stressors (Pollak, 2005). These biological changes, coupled with genetic and environmental factors, are thought to underlie the heightened risk for alcohol use disorders in individuals experiencing ELS (Brady and Sinha, 2005; Schepis et al., 2011).

The toxic effects of alcohol can be difficult to differentiate from the biologic perturbations induced by childhood stressors in alcohol-dependent populations. Both events likely induce allostatic responses, processes in which biological systems undergo long-term physiological adaptations in response to environmental demands (Koob and Moal, 2001; Sterling, 2004). Thus, the pathophysiologic responses to early childhood stressors and alcohol- and withdrawal-induced stressors, both resulting in allostatic overload (McEwen, 2008), may overlap. As ELS and alcohol dependence commonly co-occur, disentangling their respective contribution to observed neurobiological disruptions is particularly difficult. For example, in an extensive review of the neuroimaging and childhood abuse literature, Hart and Rubia (2012) conclude that the brain regions most strongly affected by ELS are the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), medial PFC (mPFC), orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), hippocampus, amygdala and cerebellum. The functioning of these areas has also been identified as altered in alcohol-dependent individuals, relative to healthy controls, during craving or stress (George et al., 2001; Seo et al., 2013), although the potential impact of early stressors (e.g., ELS) has not been considered. Clarifying the respective contribution of ELS vs. alcohol dependence to central nervous system disruptions, as well as their interaction, would advance our understanding of both disease processes as well as the pathophysiologic effects of stress (McEwen, 2008).

To explore the relative contributions of chronic alcohol use and ELS to neural reactivity, we assessed the neural response to anticipatory anxiety in a group of abstinent, alcohol-dependent men and age- and race-matched healthy controls. Anticipatory anxiety was utilized as a probe, as this acute stressor offered a high likelihood of evoking an ecologically relevant response in neural systems affected by previous stressors. In an attempt to remove, at least in part, the personalized interpretation and demands of a particular stressor, anxiety was induced by a conditioned stimulus (CS) paired with a painful unconditioned stimulus (US) [see (Ploghaus et al., 2001; Ploghaus et al., 2000; Ploghaus et al., 1999)]. We have previously reported that this paradigm induces marked cortico-limbic-striatal activation in healthy control men during the high-threat conditioned stimulus, relative to a low-threat stimulus, and that the amplitude of Blood Oxygen Level-Dependent (BOLD) signal change generally paralleled the subjective rating of anticipatory anxiety (Yang et al., 2012). However, whereas controls showed increased BOLD activation during anticipatory anxiety in the expected cortico-limbic-striatal regions, alcohol-dependent participants demonstrated a generally decreased BOLD response during the high- vs. low-threat stimulus. Group contrasts revealed that activation of the pregenual ACC/mPFC and PCC BOLD responses were significantly muted in alcohol-dependent men relative to healthy controls (Yang et al., 2013).

As posited by Ganzel et al. (2010), ongoing stressors may significantly influence the allostatic response. For the purposes of our investigation, we considered ELS as the initial allostatic overload that influenced central brain mechanisms involved in stress reactivity. Alcohol dependence (i.e., alcohol intoxication and withdrawal), the putative allostatic overload occurring subsequent to the initial childhood insults, was considered as a potential moderator affecting the relationship between ELS and the neural response to stress. Although previous functional imaging studies have considered adversity/trauma as a dichotomous variable (e.g., abuse vs. no abuse, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) vs. no PTSD), we anticipated few alcohol-dependent subjects would report an absence of previous ELS. Therefore, ELS was considered as a continuous variable to consider the effect of the full range of childhood experiences.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

The participant population and task have previously been described in Yang et al. (2013; 2012) and will be briefly reviewed here. Fifteen alcohol-dependent men reporting heavy drinking for at least 30 days prior to admission and at least a 4-year history of problematic drinking were recruited from three residential treatment units. Patients with active DSM-IV (Association, 2000) Axis I Mood, Schizophrenia or Anxiety (except PTSD) and non-substance abuse psychiatric disorders, significant medical disorders, or a history of major head trauma were excluded. Exclusion criteria also included active use of medications that interfered with stress-response functioning (e.g. psychotropics, anti-hypertensives other than thiazides, hypoglycemic agents). Fifteen healthy male controls did not meet criteria for lifetime diagnosis of a substance use disorder (except nicotine) or any other active Axis I disorder. Controls had no more than one first-degree or two second-degree relatives with substance dependence disorder. Other psychiatric/medical inclusion/exclusion criteria were the same for controls as for alcohol-dependent participants.

Clinical Assessments

Informed consents for both the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (UTSW) and Veterans Administration North Texas Health Science Center (VANTHSC) were obtained after the study was fully explained. Subjects were financially compensated for their participation. Psychiatric and substance use disorders were assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID)-Lifetime (First et al., 1996). Alcohol-dependent patients were detoxified from alcohol and housed in a residential treatment unit until studied at 3–5 weeks of abstinence. The Drinker Inventory of Consequences-Lifetime Version (DrInC) (Miller et al., 1995) was used to assess lifetime severity of alcohol-related problems. A timeline follow-back interview (Sobell and Sobell, 1978) was used to assess 3-month and lifetime drinking history. Depression and anxiety were assessed with the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck et al., 1979) and State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) (Speilberger, 1971), respectively. Smoking was documented with number of cigarettes per day. Clinical measures were obtained in the 2nd to 4th week of abstinence, usually in the week just prior to scanning.

ELS was assessed with the Childhood Adversity Interview (CAI), a semi-structured interview with good inter-rater reliability (Dienes et al., 2006). The CAI evaluates seven subtypes of ELS (separation/loss, life-threatening illness/injury, physical neglect, emotional abuse/assault, physical abuse/assault, witnessing violence, and sexual abuse/assault) occurring before age 12 years and persisting for 6 months or longer. Interviewer-rated scores of 1 (no ELS) to 5 (most severe ELS) were based on summaries of the events, circumstances, and their contexts. The scores from all seven domains were summed to yield a total CAI score (range 7–35).

fMRI Task

Sensory threshold calibration and fMRI studies were performed at the Meadows Diagnostic Imaging Center at UTSW. A computerized thermal stimulator (Pathway Pain & Sensory Evaluation System, Medoc Ltd., Haifa, Israel) administered stimuli through a non-magnetic Contact Heat-Evoked Potential Stimulator (CHEPS) thermode secured to participants’ left ventral inner forearm. Sensitivity to heat was determined using a Method of Limits program (Heldestad et al., 2010; Yarnitsky, 1997) within five days prior to the fMRI session.

The anticipatory anxiety paradigm was designed to induce anticipatory anxiety using a combination of pain (the CS warned of the possibility of an impending painful US) and unpredictability (the participant did not know either if a painful US would occur following any given CS or how soon following the CS onset the US would occur). Two CSs were, therefore, presented: a high threat CS (square) denoting duration uncertainty and the possibility of a painful US and a low threat CS (triangle) denoting a predictable, non-painful US. Visual stimuli were generated using Presentation software (version 10.0; Neurobehavioral Systems, Albany, CA) and projected with an LCD projector (NEC LT260) via a back projection system. For each trial, a triangle or square was presented as a CS and followed by an US: low heat (5°C below pain threshold) or high heat (1°C above pain threshold). A triangle (low-threat CS) signaled the impending and certain application of a low heat US; a square (high-threat CS) signaled the impending application of either a low- or high-heat US. The CS remained on screen throughout the trial. The trial was separated into two periods: Anticipatory Anxiety (10 to 18 seconds) and Heat Pulse (8 seconds). During the first four seconds of the Anticipatory Anxiety period, the CS was accompanied by the question “How anxious are you now?” and a rating scale (1 through 4). Participants were asked to rate their anxiety regarding the impending heat stimulus during this four-second period. The CS (without the rating question) then remained on the screen for an additional 6–14 sec (pseudo-randomized 6, 8, 10, 12, and 14 sec) for the duration of the Anticipatory Anxiety period. During the subsequent (and final) 8 sec of each trial (Heat Pulse period), the heat stimulus increased from a baseline temperature of 32°C by 10°C/sec to the low or high temperature (using a Ramp and Hold program), remained at the peak for 3 sec, and then returned to baseline temperature. Forty trials, 20 squares (10 low heat and 10 high heat) and 20 triangles (all low heat), were presented over a period of 23 minutes. Trial order was pseudo-randomized with the stipulation that neither triangles nor squares were presented more than twice consecutively. A pseudo-randomized interstimulus interval consisted of a circle shown between each trial for 9, 10, or 11 sec. A 90-sec rest period separated the paradigm into halves during which “Break” was presented on the screen.

To familiarize subjects with the paradigm and the MR scanner environment, a mock scan was performed on the same day as threshold testing. The high-heat stimulus was set 2°C lower than threshold to avoid needless exposure to pain, compared to 1°C higher than threshold during fMRI, but the design was otherwise the same as described for the fMRI paradigm. Participants who did not endorse higher ratings for the high threat CS (square) relative to the low-threat CS (triangle) were queried regarding their understanding of the paradigm. To avoid demand characteristics, there was no attempt to encourage or advise subjects to rate the square (high-threat) CS differently than triangle (low-threat) CS.

Participants arrived for testing in the late afternoon. Nicotine-dependent participants were allowed a cigarette one hour before study session and asked to abstain until after completing the session. Scans were obtained on a Siemens 3T TIM Trio scanner, equipped with 12-channel receiver array head coil. fMRI scans were obtained using gradient echo planar imaging (GRE-EPI): TR=2000 ms, TE=20 ms, flip angle=90 degrees, base resolution=64×64, voxel size=3.3×3.3×3.0 mm, field of view (FOV) = 210 mm, A-P phase encode, bandwidth = 2442 Hz/pixel. After 3 discarded acquisitions to establish magnetization equilibrium, 690 image volumes of 40 interleaved sagittal slices with 3-mm slice thickness were obtained (whole brain). Anatomical scans using a T1-weighted multi-planar reformatted MPRAGE sequence (TR=2250 ms, TI = 900 ms, TE=2.9 ms, flip angle=9 degrees, base resolution=256×256, FOV = 230 ms, voxel size=0.9×0.9×1.1 mm) facilitated localization and coregistration of fMRI data.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics quantified drinking characteristics of the alcohol-dependent group, including years of problem drinking and drinks per day in the past 90 days and lifetime. Groups were compared using two-sample t or χ2 tests. Anticipatory anxiety ratings for high and low anxiety CSs were averaged across the 20 ratings. Between-group temperature threshold and anxiety ratings were compared by two-sample t tests.

The fMRI data were analyzed with FEAT (FMRI Expert Analysis Tool) Version 5.98, a tool of FSL (FMRIB’s Software Library, www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl). Preprocessing included motion correction, slice-timing correction, spatial smoothing with a 5mm full-width-half-maximum Gaussian filter, intensity normalization using a grand mean scaling factor, and high-pass temporal filtering (sigma=30.0s) to remove low frequency drift. Brain extraction and registration to high resolution and template (MNI152) images were carried out by BET (Brain Extraction Tool) (Smith, 2002) and FLIRT (FMRIB’s Linear Image Registration Tool) (Jenkinson et al., 2002; Jenkinson and Smith, 2001), respectively.

Time-series statistical analysis was performed by FMRIB’s Improved Linear Model (FILM), in which a general linear model (GLM) framework of the stimulus onset types as explanatory variables, convolved with a hemodynamic response function (HRF) with time derivatives, was used to fit the time-series data of each voxel. Two conditions were analyzed at the subject level: low and high Anticipatory Anxiety (triangle CS, square CS). Individual contrast images were computed for the anticipatory anxiety contrast (square CS vs. triangle CS). Group level inference was at the cluster level, pre-thresholded and constrained by a gray matter mask of 40% probability based on the avg152T1 (average of the T1W anatomic images spatially normalized to the MNI1532 template), using a cluster-defining threshold of Z = 2.58 and an extent threshold corresponding to a corrected p-value less than 0.05 based on Gaussian random field (GRF) theory (Worsley, 2001).

The effect of the interaction between CAI and group on the BOLD response during Anticipatory Anxiety (high threat vs. low threat) was our primary interest. Statistically, the test of this interaction assessed whether the regression of the BOLD response on CAI differed between alcohol-dependent participants and healthy controls. Threshold temperature, smoking, years education, BDI, and STAI scores were used as covariates in the group BOLD regression analysis to remove additional variability in the BOLD response. When anatomically-defined regions were of interest, %BOLD amplitudes of a functionally-derived cluster within specific anatomically-identified regions of interest (ROI) were described based on the FSL atlas (http://www.cma.mgh.harvard.edu/fsl_atlas.html) and an in-house template for striatum (Gopinath et al., 2011). In addition, for those ROIs that exhibited a significant group difference between their respective BOLD responses to CAI, we explored the BOLD/CAI relationship within each group separately to assess whether the alcohol-dependent participants, the healthy controls, or both contributed to the interaction.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics, Temperature Threshold and Anxiety Ratings

As previously described (Yang et al., 2013), control and alcohol-dependent subjects did not significantly differ in race or age. The alcohol-dependent subjects were more likely to smoke cigarettes and had lower education and higher BDI, STAI, and CAI scores relative to control participants. One patient met DSM-IV criteria for PTSD (Table 1). Threshold temperatures were slightly higher in alcohol-dependent relative to control subjects (mean±SD; 46.8±2.3 vs. 45.4±1.4°C, respectively; t = 2.10, df=28, p =.05). High threat ratings were significantly higher in both groups relative to the low threat ratings (controls: 2.7±0.79 vs. 1.1±0.20, alcohol-dependent: 2.8±0.85 vs. 1.3±0.41; t = 7.7, p < .001). There were no significant group differences in subjective anxiety ratings to either the low- (t = 1.35, df = 28, p = 0.17) or high- (t = 0.37, df = 28, p = 0.72) threat CS.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Alcohol-Dependent Participants and Healthy Controls

| Controls (n=15) | Alcohol dependent (n=15) |

t or χ2 |

df | p- value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 45.5±8.5 | 42.3±7.1 | 1.12 | 28 | NS |

| Race | 0.97 | 2 | NS | ||

| White | 12 | 12 | |||

| Black | 3 | 3 | |||

| Hispanic | 0 | 1 | |||

| Handedness | 1.97 | 2 | NS | ||

| Right | 12 | 12 | |||

| Left | 1 | 0 | |||

| Ambidextrous | 1 | 3 | |||

| Education (years) | 15.2 ± 1.5 | 11.4 ± 1.2 | 7.64 | 28 | <0.001 |

| Cigarettes/day | 1.2 ± 4.6 | 14.1 ± 11.9 | 4.25 | 20 | <0.001 |

| CAI | 9.5 ± 2.6 | 13.0 ± 3.0 | 3.41 | 28 | 0.002 |

| BDI | 2.3 ± 2.9 | 7.3 ± 4.3 | 3.77 | 28 | <0.001 |

| STAI | 26.9 ± 7.7 | 34.7 ± 8.3 | 2.67 | 28 | 0.01 |

| DrInC | 8.6 ± 8.0 | 38.5 ± 4.7 | 12.34 | 28 | <0.001 |

| Years of problem drinking |

20.3 ± 7.2 | ||||

| Drinks in 90 days | 1312.9 ± 670.7 | ||||

| Drinks over lifetime |

102410.5 ± 84673.6 |

||||

| Days abstinent | 25.3 ± 5.2 |

Data are mean ± SD. Comparisons between groups were by t test or χ2. BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; STAI, State Trait Anxiety Inventory; DrInC, Drinker Inventory of Consequences-Lifetime Version.

Interaction Between CAI and Group on BOLD Response

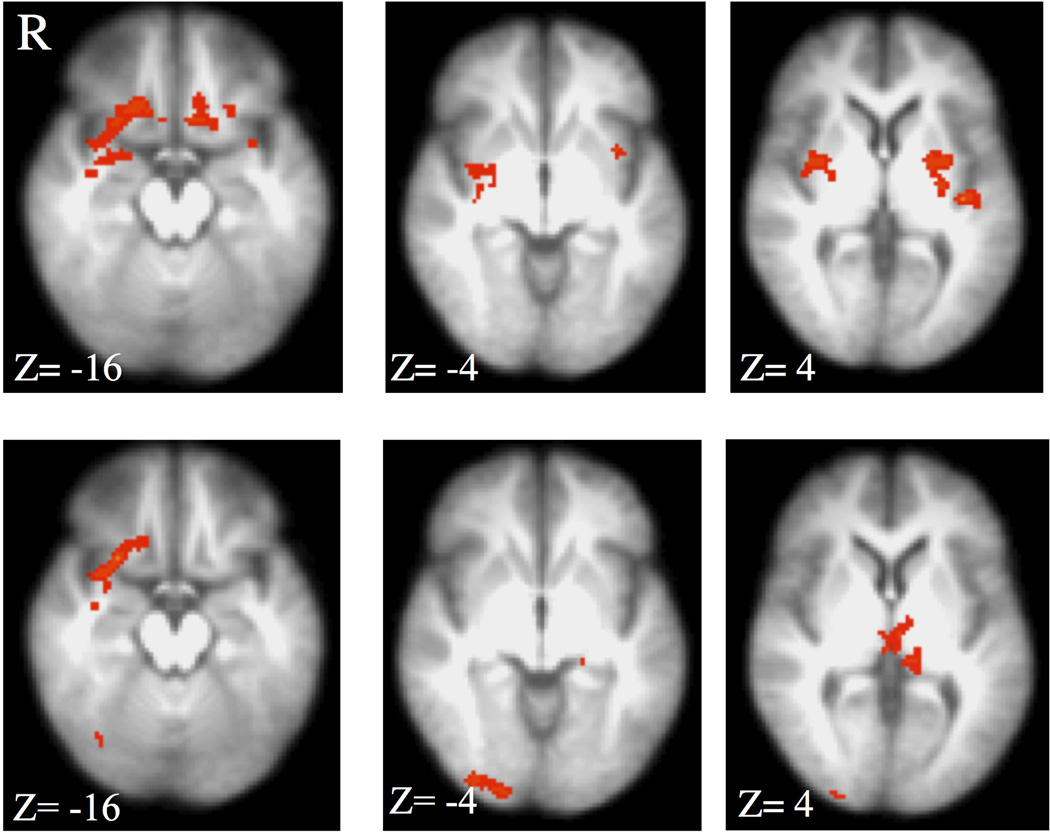

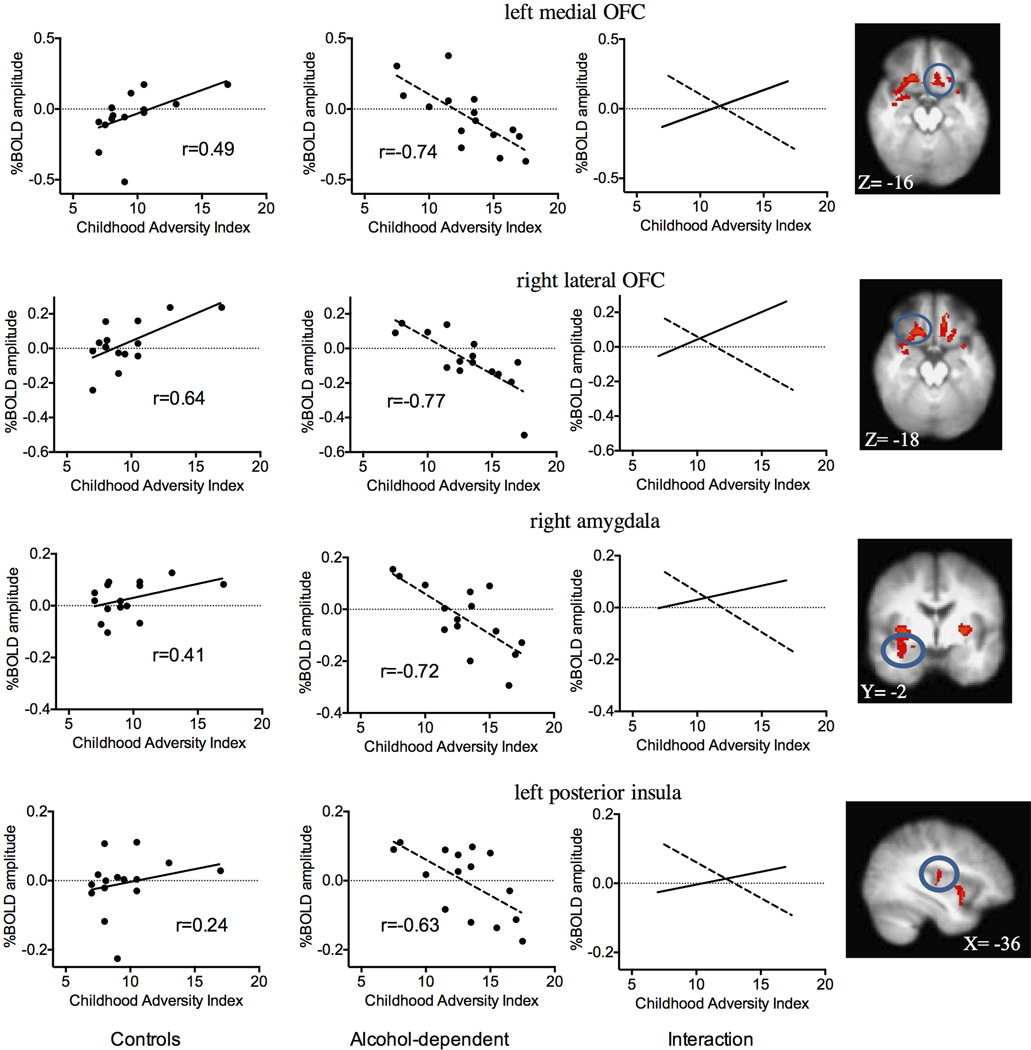

A significant interaction was observed between CAI and group on the high- vs. low-threat BOLD amplitude in the right amygdala, bilateral posterior putamen, left medial OFC, right medial OFC extending into the lateral OFC, right middle insula and left posterior insula (Table 2 and Fig. 1, upper panel). Within-group correlations revealed that the interaction was primarily driven by a negative relationship between CAI and BOLD amplitude in the alcohol-dependent subjects (right amygdala, bilateral posterior putamen, and insular regions; Table 2 and Fig. 2, upper panel). The only significant relationships in the control group were positive correlations between total CAI and the BOLD response in the OFC (Table 2; Fig. 2, lower panel). There were no significant positive relationships between CAI and BOLD high- vs. low-threat responses in the alcohol-dependent individuals or negative relationships in the control participants. Since our population included right-handed, ambidextrous, and left-handed participants, the interaction analysis was conducted using only right-handed subjects (12 in each group). Visual inspection of this analysis revealed nearly identical findings to Fig. 1.

Table 2.

Interaction Between Childhood Adversity Interview (CAI) Score and Group (Alcohol-dependent and Control Participants) on BOLD Response during Anticipatory Anxiety

| MNI Coordinates | Volume (voxels) |

Z max | Sign of Correlation by Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| region | X | Y | Z | controls | alcohol-dep | ||

| lateral OFC, right2 | 22 | 24 | −18 | 232 | 3.54 | positive | |

| putamen, right2 | 34 | −2 | 2 | 122 | 3.50 | negative | |

| insula, right1 | 38 | 0 | 4 | 61 | 3.24 | negative | |

| medial OFC, right1 | 14 | 22 | −20 | 60 | 3.39 | positive | negative |

| amygdala, right2 | 32 | −2 | −16 | 111 | 2.93 | negative | |

| medial OFC, left2 | −10 | 30 | −20 | 183 | 3.48 | positive | |

| putamen, left2 | −26 | −2 | 2 | 150 | 3.56 | negative | |

| insula, left2 | −36 | 8 | −8 | 104 | 3.45 | negative | |

corrected p<0.01

corrected p<0.0001

Figure 1.

Top panel: Interaction between group (alcohol-dependence and control) and Childhood Adversity Interview (CAI) on the BOLD response to high- vs. low-threat CS. A significant interaction (z=2.58, p<0.05, corrected) was observed in the bilateral posterior putamen, right amygdala and middle insula, right and left OFC, and posterior insula. Bottom panel: Interaction between group and CAI subdomain Separation/Loss. Overlapping areas with the total CAI score interaction were limited to the right OFC. R= right, z = MNI transverse coordinate.

Figure 2.

Top panel: Negative relationship between CAI total score and BOLD response to high- vs. low-threat CS in alcohol-dependent participants only. Regions showing a significant relationship (z=2.58, p<0.05, corrected) included the right amygdala, bilateral posterior putamen, and bilateral insular cortex. Bottom panel: Positive relationship between CAI total score and BOLD response to high- vs. low-threat CS in control group only. Regions showing a significant relationship (z=2.58, p<0.05, corrected) were limited primarily to the right OFC. R= right, y = MNI sagittal coordinate, z = MNI transverse coordinate.

To determine whether these findings were particular to domains of the CAI, similar linear models, assessing group and CAI interactions, were applied to each of the domains separately (Fig. 1, lower panel). Only the Separation/Loss domain of the CAI revealed a significant interaction with group. The Separation/Loss domain-specific analysis overlapped with the analysis of total CAI only in the right OFC (Fig. 1, two left panels).

Relationship between BOLD Amplitude and Severity of Alcohol Dependence

Since the negative relationship between high- vs. low-threat BOLD amplitude to high- vs. low-threat and CAI was confined to the alcohol-dependent group, this association may have been due to the severity of alcohol itself rather than ELS. The relationship between BOLD amplitude and several measures of alcohol use (years since onset of problem drinking, number of drinks in lifetime, number of drinks in past 90 days, DrInC total score) was therefore assessed in the alcohol-dependent group. Pearson’s r revealed no significant relationship (r = −0.23 to 0.16, centered near zero) between CAI and alcohol severity measures.

DISCUSSION

During experimentally-induced anticipatory anxiety, the relationship between ELS and the cortical-striatal-limbic BOLD response to a high threat stimulus was significantly affected by the presence or absence of alcohol dependence. Alcohol dependence showed a similar effect on the relationship between the CAI domain Separation/Loss, but not other CAI domains, with the right OFC BOLD response during anticipatory anxiety. Whereas controls tended to show either no relationship or a positive relationship between the amount of self-reported ELS and their cortico-striatal-limbic stressor response, alcohol-dependent participants demonstrated a negative relationship.

In our previous report (Yang et al., 2013), we observed a generally decreased cortico-striatal-limbic BOLD response to the heat threat in alcohol-dependent participants whereas the control subjects showed a robust increase in BOLD amplitude. Our present findings suggest that the decreased BOLD response in the alcohol-dependent group may be explained, at least in part, by the amount of ELS. Several of the regions shown here to be negatively correlated with CAI in the alcohol-dependent group showed either a decreased response during anticipatory anxiety in the alcohol-dependent participants (e.g. right and left medial OFC) or an increased BOLD response in the control, but not alcohol-dependent, participants (e.g. bilateral putamen, right insula). The regions presently identified in the ELS and group interaction (i.e., OFC, right amygdala, and bilateral insula and putamen) are intimately involved in the cortico-limbic-striatal emotional neural circuits, including the formation and storage of emotional memories (amygdala), assessing interoceptive salience (insula), the interpretation of reward sensitivity and evaluation (medial OFC), and the integration of emotional, cognitive, and sensorimotor information for decision-making (putamen/dorsal striatum). As key components of the emotional circuit, including stress response, reward, and craving, these regions may be particularly sensitive to the effects of both acute and chronic stressors (i.e., ELS, alcohol intake and/or alcohol withdrawal). The amygdala is particularly sensitive to the combined effects of multiple stressors and the concomitant hypercortisolemia (Herman, 2012) and others have reported alterations in the amygdala, OFC, and insula in patients with PTSD in response to stress, the retrieval of emotionally-valenced words, or fear acquisition [see (Hart and Rubia, 2012)].

Whereas we hypothesized that there would be an additive allostatic effect of multiple stressors in the alcohol-dependent participants (i.e., ELS, alcohol intoxication, alcohol withdrawal), the combined ELS and excessive alcohol use appeared to have a qualitatively different effect than ELS without alcohol dependence. The absence of a significant correlation between CAI scores and either functional (DrInC) or alcohol use severity measures of dependence suggests that the decrease in BOLD amplitude was not a direct consequence of alcohol use or dependence itself. Although this conclusion would have been strengthened if the CAI scores in the control and alcohol-dependent groups did not significantly differ, there was nevertheless an overlap in scores between the two groups. Consequently, there is evidence that the relationship between ELS and BOLD amplitude is linear for each group and that the slope differential is indicative of a real interaction (i.e., the alcohol-dependent group showed a decrease in BOLD amplitude as CAI scores increased, while the control group showed a more constant to slightly positive BOLD amplitude as CAI scores increased.) That the group CAI distributions overlap to some extent, together with the observation that CAI scores are not correlated with severity of alcohol use, provide some evidence that we do not have complete confounding between group and ELS. Nevertheless, our findings would benefit from replication with ELS negative and positive participants in both control and alcohol-dependent groups.

This interaction suggests that, either due to genetic and/or environmental differences in their childhood, some individuals respond to ELS with an attenuated neural response when confronted with threatening events. This altered neural reactivity may subsequently leave the individual vulnerable to the later development of alcohol dependence, which then further attenuates cortico-limbic activation under stress conditions. These findings are consistent with a number of observations. First, trauma or adversity can down-regulate stress response systems (Heim and Nemeroff, 2001; Trickett et al., 2010). Further, some studies have suggested that muted stress reactivity may confer vulnerability to the development of psychopathology (Delahanty and Nugent, 2006; Ehring et al., 2008). Second, decreased neural cortico-limbic response to stressors has been identified in other psychiatric disorders, including generalized anxiety (Bremner et al., 1999b; Etkin et al., 2010) and post-traumatic stress disorder (Kim et al., 2008). It is unknown if these findings are specific to the psychiatric disorder or to a pre-existing vulnerability. In the case of alcohol dependence, muted stress-reactivity induced by ELS may leave the individual susceptible to the development of alcohol dependence, which may further down-regulate stress response systems. Of course, an alternate explanation could be that ELS increases neural reactivity and that this heightened reactivity increases the risk for alcohol dependence. The allostatic response to chronic alcohol intoxication and withdrawal then dampens the cortico-striatal response to threatening situations.

The control population endorsed relatively constrained levels of ELS (likely due, at least in part, to multiple psychiatric exclusion criteria) that may have obscured relationships with the BOLD response. However, the presence of a positive relationship between bilateral OFC BOLD amplitude and CAI in the control group and the presence of positive trends between CAI and BOLD amplitude in the other regions (Fig. 3) suggest that the inverse relationship was confined to the alcohol-dependent group. These findings support the conclusions offered by Hart and Rubia (2012), who noted that the high prevalence of ELS in psychiatric disorders limit the ability to accurately attribute functional brain alterations to childhood maltreatment, the psychiatric condition, or both. Our findings suggest that co-occurrence of ELS and a psychiatric disorder (in this case, alcohol dependence) do, indeed, significantly complicate our understanding of the resultant neural disruptions. Others have also shown an interaction between ELS and psychiatric illness on the neural response to a stressor (Shin et al., 1999). When exposed to personalized narrative scripts of their trauma, for example, women with childhood sexual abuse and PTSD revealed greater increases in blood flow in the anterior prefrontal cortex and posterior cingulate but larger decreases in blood flow in the hippocampus and inferior temporal cortex than women with childhood sexual abuse who did not have PTSD (Bremner et al., 1999a). Similarly, in contrast to women with childhood abuse but no borderline personality disorder, women with both abuse and the psychiatric disorder failed to activate the anterior cingulate and OFC when exposed to personalized narrative scripts (Schmahl et al., 2004).

Figure 3.

Interaction between CAI and group on BOLD response to anticipatory anxiety (healthy controls on left panel, alcohol-dependent participants on middle panel). Each point on the scatterplots represents an average within identified regions found to be significant by cluster extent inference. Right panel notes specific cluster (from Fig. 1, top panel) used to determine %BOLD amplitude in left and middle panels. r = Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient.

Strengths of this study included the elimination of potential confounds of co-morbid non-substance use disorders and psychotropic medications, both of which confound many studies assessing the effects of ELS in adults. In addition, the assessment of alcohol-dependent subjects following at least three weeks of abstinence avoided the possible effects of alcohol withdrawal. The task was successful in inducing a strong (and similar magnitude) anticipatory anxiety response in both groups. Among the weaknesses of this study, groups were not matched for threshold temperature, smoking, BDI, or STAI. However, consideration of these variables as covariates did not significantly affect our findings. Reports of childhood trauma were not validated with historical records or family confirmation (Widom, 1999). Regardless, this measure is an accurate reflection of the individual’s own interpretation of past events, which may be a more relevant measure than the occurrence of events. Although alcohol-dependent subjects reported higher ELS than healthy controls, the overall CAI score was relatively low. Due to exclusion of participants with Axis I disorders in the study, the finding’s generalizability was limited. The lack of women in the study limits the interpretation of our findings to men, particularly as women are more likely to develop PTSD following traumatic experiences (Tolin and Foa, 2006) and women experience higher rates of certain traumas (e.g., sexual abuse) specifically linked to the development of alcohol use disorders (Kendler et al., 2000). However, as many of the previous imaging studies exploring the effects of childhood have been limited to women, this focus on men with ELS supports the importance of ELS in both sexes. In addition, whereas the prevalence of ELS appears to be relatively similar between the genders, women reportedly are more resilient to developing psychopathology than men and women experience only half the prevalence of alcohol use disorders (Enoch, 2011). It is also of note that the association between neural reactivity and the CAI was most prominent for adverse events (e.g. separation/loss) rather than traumatic events (e.g., physical, sexual or emotional abuse). The interactions observed in our study, therefore, may not have been evident if other, more common measures of childhood trauma, such as the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (Bernstein and Fink, 1998), were used.

In summary, the significant interaction between the ELS and alcohol dependence on the BOLD response to anticipatory anxiety suggests that both pre-morbid experiences and excessive alcohol use may play an important role in subsequent stress reactivity. Future research should explore whether these associations can be replicated in a larger sample of control and alcohol-dependent men and women with a wider range of trauma severity, are specific to alcohol dependence or are evident in other substance use and psychiatric disorders (e.g., depression, PTSD), and have long-term implications upon disease severity and relapse.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by INIAStress U01AA013641 and U01AA16668, UL1TR000451 and the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Clinical Sciences Research and Development. We are grateful to Larry Steier and Victoria Vescovo for their skilled assistance of fMRI scanning and the staff of the Substance Abuse Team at the VA North Texas Health Care System and Homeward Bound, Inc. for their support in the screening and recruitment of study subjects. We also thank Dr. Kaundinya Gopinath for providing the anatomic template for the striatum and Aman Goyal for his assistance with administering the experiment.

Footnotes

The work was conducted at 5323 Harry Hines Blvd., Dallas, TX and 4500 S. Lancaster Rd., Dallas, TX 75216

Authors Contributions

BA, RWB, MDD, and UR were responsible for the study concept and design. YH recruited participants and operated the thermal stimulator. YH performed imaging analysis with guidance from JSS. BA, JSS, RWB, MDD, UR, CN assisted with interpretation of findings. YH drafted the manuscript. BA, JSS, RWB, UR, CN provided critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors critically reviewed content and approved final version for publication.

References

- Association AP. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed, text revision) 4th. Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1979;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Fink LA. The Psychological Corportation. San Antonio: Harcourt Brace & Company; 1998. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: A Retrospective Report. [Google Scholar]

- Brady KT, Back SE. Childhood trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder, and alcohol dependence. Alcohol research : current reviews. 2012;34:408–413. doi: 10.35946/arcr.v34.4.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady KT, Sinha R. Co-occurring mental and substance use disorders: the neurobiological effects of chronic stress. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1483–1493. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Narayan M, Staib LH, Southwick SM, McGlashan T, Charney DS. Neural correlates of memories of childhood sexual abuse in women with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1999a;156:1787–1795. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.11.1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Staib LH, Kaloupek D, Southwick SM, Soufer R, Charney DS. Neural correlates of exposure to traumatic pictures and sound in Vietnam combat veterans with and without posttraumatic stress disorder: a positron emission tomography study. Biol Psychiatry. 1999b;45:806–816. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00297-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delahanty DL, Nugent NR. Predicting PTSD prospectively based on prior trauma history and immediate biological responses. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1071:27–40. doi: 10.1196/annals.1364.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dienes KA, Hammen C, Henry RM, Cohen AN, Daley SE. The stress sensitization hypothesis: understanding the course of bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2006;95:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eames SF, Businelle MS, Suris A, Walker R, North CS, Xiao H, Adinoff B. Stress moderates the effect of childhood trauma and adversity on recent drinking in treatment-seeking alcohol-dependent men. J Consult Clin Psychol. doi: 10.1037/a0036291. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehring T, Ehlers A, Cleare AJ, Glucksman E. Do acute psychological and psychobiological responses to trauma predict subsequent symptom severities of PTSD and depression? Psychiatry Res. 2008;161:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enoch MA. The role of early life stress as a predictor for alcohol and drug dependence. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;214:17–31. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1916-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etkin A, Prater KE, Hoeft F, Menon V, Schatzberg AF. Failure of anterior cingulate activation and connectivity with the amygdala during implicit regulation of emotional processing in generalized anxiety disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:545–554. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09070931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MH, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, patient ed (SCID-I/P, version 2.0) New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ganzel BL, Morris PA, Wethington E. Allostasis and the human brain: Integrating models of stress from the social and life sciences. Psychol Rev. 2010;117:134–174. doi: 10.1037/a0017773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George MS, Anton RF, Bloomer C, Teneback C, Drobes DJ, Lorberbaum JP, Nahas Z, Vincent DJ. Activation of prefrontal cortex and anterior thalamus in alcoholic subjects on exposure to alcohol-specific cues. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:345–352. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.4.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopinath K, Ringe W, Goyal A, Carter K, Dinse HR, Haley R, Briggs R. Striatal functional connectivity networks are modulated by fMRI resting state conditions. Neuroimage. 2011;54:380–388. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart H, Rubia K. Neuroimaging of child abuse: a critical review. Frontiers in human neuroscience. 2012;6:52. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Nemeroff CB. The role of childhood trauma in the neurobiology of mood and anxiety disorders: preclinical and clinical studies. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:1023–1039. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01157-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldestad V, Linder J, Sellersjo L, Nordh E. Reproducibility and influence of test modality order on thermal perception and thermal pain thresholds in quantitative sensory testing. Clin Neurophysiol. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2010.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman JP. Neural pathways of stress integration: relevance to alcohol abuse. Alcohol research : current reviews. 2012;34:441–447. doi: 10.35946/arcr.v34.4.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady M, Smith S. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. Neuroimage. 2002;17:825–841. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)91132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Smith S. A global optimisation method for robust affine registration of brain images. Med Image Anal. 2001;5:143–156. doi: 10.1016/s1361-8415(01)00036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Bulik CM, Silberg J, Hettema JM, Myers J, Prescott CA. Childhood sexual abuse and adult psychiatric and substance use disorders in women: an epidemiological and cotwin control analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:953–959. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.10.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Hatzenbuehler ML, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Stress and alcohol: epidimiologic evidence. Alcohol research : current reviews. 2012;34:391–400. doi: 10.35946/arcr.v34.4.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MJ, Chey J, Chung A, Bae S, Khang H, Ham B, Yoon SJ, Jeong DU, Lyoo IK. Diminished rostral anterior cingulate activity in response to threat-related events in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42:268–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Moal M. Drug addiction, dysregulation of reward, and allostasis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;24:97–129. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Central effects of stress hormones in health and disease: Understanding the protective and damaging effects of stress and stress mediators. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;583:174–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.11.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Tonigan JS, Longabaugh R. The Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrlnC): An Instrument for Assessing Adverse Consequences of Alcohol Abuse. Rockville, MD: National Institutes of Health; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ploghaus A, Narain C, Beckmann CF, Clare S, Bantick S, Wise R, Matthews PM, Rawlins JN, Tracey I. Exacerbation of pain by anxiety is associated with activity in a hippocampal network. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9896–9903. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-24-09896.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploghaus A, Tracey I, Clare S, Gati JS, Rawlins JN, Matthews PM. Learning about pain: the neural substrate of the prediction error for aversive events. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:9281–9286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160266497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploghaus A, Tracey I, Gati JS, Clare S, Menon RS, Matthews PM, Rawlins JN. Dissociating pain from its anticipation in the human brain. Science. 1999;284:1979–1981. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5422.1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak SD. Early adversity and mechanisms of plasticity: integrating affective neuroscience with developmental approaches to psychopathology. Dev Psychopathol. 2005;17:735–752. doi: 10.1017/S0954579405050352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schepis TS, Rao U, Yadav H, Adinoff B. The limbic-hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the development of alcohol use disorders in youth. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:595–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01380.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmahl CG, Vermetten E, Elzinga BM, Bremner JD. A positron emission tomography study of memories of childhood abuse in borderline personality disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:759–765. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher JA, Coffey SF, Stasiewicz PR. Symptom severity, alcohol craving, and age of trauma onset in childhood and adolescent trauma survivors with comorbid alcohol dependence and posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Addict. 2006;15:422–425. doi: 10.1080/10550490600996355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo D, Lacadie CM, Tuit K, Hong KI, Constable RT, Sinha R. Disrupted Ventromedial Prefrontal Function, Alcohol Craving, and Subsequent Relapse Risk. JAMA psychiatry. 2013:1–13. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin LM, McNally RJ, Kosslyn SM, Thompson WL, Rauch SL, Alpert NM, Metzger LJ, Lasko NB, Orr SP, Pitman RK. Regional cerebral blood flow during script-driven imagery in childhood sexual abuse-related PTSD: A PET investigation. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:575–584. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.4.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM. Fast robust automated brain extraction. Hum Brain Mapp. 2002;17:143–155. doi: 10.1002/hbm.10062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell MB, Sobell LC. Behavioral Treatment of Alcohol Problems. New York: Plenum Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Speilberger CD. Trait-state anxiety and motor behavior. Journal of Motor Behavior. 1971;3:265–279. doi: 10.1080/00222895.1971.10734907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling P. Principles of allostasis: optimal design, predictive regulation, pathophysiology and rational therapeutics. In: Schulkin J, editor. Allostasis, Homeostasis, and the Costs of Adaptation. Cambridge University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DF, Foa EB. Sex differences in trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: a quantitative review of 25 years of research. Psychol Bull. 2006;132:959–992. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trickett PK, Noll JG, Susman EJ, Shenk CE, Putnam FW. Attenuation of cortisol across development for victims of sexual abuse. Dev Psychopathol. 2010;22:165–175. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS. Posttraumatic stress disorder in abused and neglected children grown up. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1223–1229. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.8.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worsley KJ. Testing for signals with unknown location and scale in a chi(2) random field, with an application to fMRI. Advances in Applied Probability. 2001;33:773–793. [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Devous MD, Briggs RW, Spence JS, Xiao H, Kreyling N, Adinoff B. Altered Neural Processing of Threat in Alcohol-Dependent Men. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013 doi: 10.1111/acer.12187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Spence JS, Devous MD, Briggs RW, Goyal A, Xiao H, Yadav H, Adinoff B. Striatal-limbic activation is associated with intensity of anticipatory anxiety. Psychiatry Res. 2012;204:123–131. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarnitsky D. Quantitative sensory testing. Muscle Nerve. 1997;20:198–204. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(199702)20:2<198::aid-mus10>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]