Abstract

Asthma is a complex and heterogeneous disease that is characterized by airway hyperreactivity (AHR) and airway inflammation. Although asthma was long thought to be driven by allergen-reactive Th2 cells, it has recently become clear that the pathogenesis of asthma is more complicated and associated with multiple pathways and cell types. A very exciting recent development was the discovery of innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) as key players in the pathogenesis of asthma. ILCs do not express antigen receptors but react promptly to “danger signals” from inflamed tissue and produce an array of cytokines that direct the ensuing immune response. The roles of ILCs may differ in distinct asthma phenotypes. ILC2s may be critical for initiation of adaptive immune responses in inhaled allergen-driven AHR, but may also function independently of adaptive immunity, mediating influenza-induced AHR. ILC2s also contribute to resolution of lung inflammation through their production of amphiregulin. Obesity-induced asthma, is associated with expansion of IL-17A-producing ILC3s in the lungs. Furthermore, ILCs may also contribute to steroid-resistant asthma. Although the precise roles of ILCs in different types of asthma are still under investigation, it is clear that inhibition of ILC function represents a potential target that could provide novel treatments for asthma.

Keywords: airway hyperreactivity, allergy, asthma, innate lymphoid cells, influenza, obesity

Introduction

Asthma is an immunological disease of the airways characterized by airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR), a cardinal feature of asthma, and airway inflammation. Allergen-specific Th2 cells have long been thought to critically orchestrate the adaptive TH2 immune responses in the lung resulting in allergic asthma, the most common form of asthma [1]. More recently, it has become clear that asthma is a very heterogeneous and complex disease, involving much more than adaptive immunity, and that there are both allergic and non-allergic phenotypes, mediated by innate and adaptive immune cells which regulate and shape pulmonary inflammation [2].

Innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) have recently been identified as a unique group of innate immune cells which are characterized by their lack of T-cell and B-cell receptors (TCRs and BCRs, respectively) [3, 4]. ILCs play critical roles in host defense and tissue homeostasis, particularly in mucosal tissues [3]. ILCs have been shown to rapidly produce cytokines at high levels in response to a wide range of innate signals, i.e. IL-25, IL-33, TSLP and IL-1β. Traditionally, T cells were thought to be the key players in the regulation of immune responses by producing type 1 (TH1), type 2 (TH2) and type 3 (TH17 and TH22) cytokines. As counterparts of these T-cell subsets, ILCs may also be classified into distinct subsets based on cytokine profiles and functional characteristics, which reflect those of their T-cell subset counterparts [4–6] Although the interaction between T cells and ILCs and their contribution to distinct types of immune responses is still under investigation, recent studies have shown that ILCs provide new paradigms for mechanisms underlying immune responses, particularly in mucosal tissues such as intestine and lungs [7–10]. In this review, we will focus on the role of ILCs in various forms of asthma.

Heterogeneity of asthma

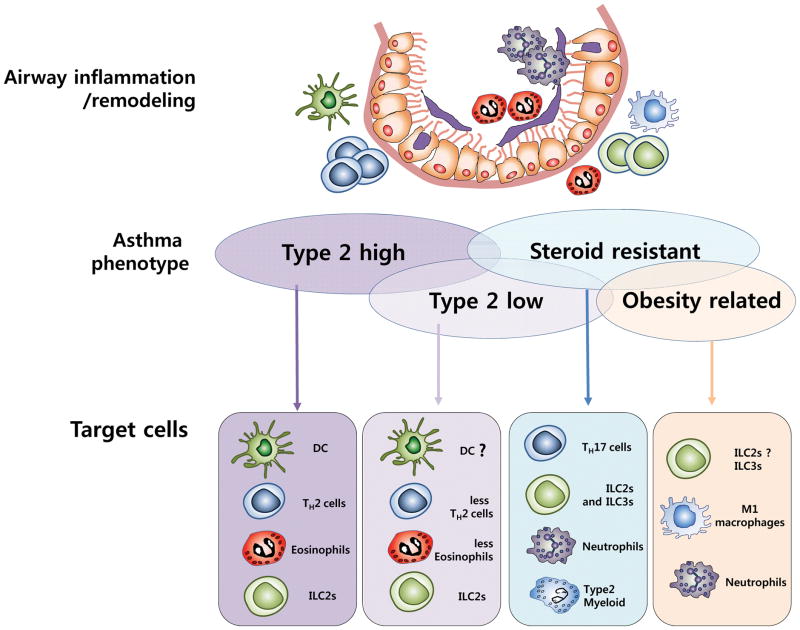

Asthma, which has increased considerably in prevalence over the past three decades, and now affects approximately 300 million people worldwide [11], is a heterogeneous disease caused by environmental factors in combination with major and minor susceptibility genes [12, 13]. This heterogeneity in asthma is based on clinical features including the presence of allergy, symptom-induction by air pollution [14, 15] or cigarette smoke [16], or association with obesity [8, 17, 18] and viral infection [7, 19, 20], as well as age, gender, lung function and body mass index (BMI). To understand the underlying disease mechanisms of asthma, investigators have examined the participation of distinct immunological cell types, e.g., cells producing Type 2 cytokines, Th17 or other cytokines. By synthesizing past and recent studies, distinct phenotypes of asthma have been proposed that implicate a role for these distinct immunological cell types, e.g., Type 2high, Type 2low, steroid resistant and obesity related phenotypes [21] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Asthma phenotypes and related immune cell types.

Asthma is a heterogeneous disease with multiple phenotypes associated with different cell types and cytokines. The Type 2high phenotype is associated with Type 2 cytokines and activation of TH2 cells. This phenotype is often correlated with eosinophilia and activation of DCs, as well as ILC2s. In the Type 2low phenotype observed in some asthmatics, lower levels of TH2 cytokines and fewer eosinophils are detected. Type 2 cytokine inhibitors could be promising therapeutic targets for these phenotypes. Although Type 2 inflammation is important for asthma development, steroid-resistant and obesity-associated asthma phenotypes are often associated with non-Type 2 inflammatory responses. ILC2s, ILC3s and T2M (type 2 myeloid cells) have been associated with steroid-resistant asthma. M1 macrophages, ILC3s, and neutrophils induce inflammation to worsen obesity-related asthma. Further understanding of these diverse asthma phenotypes may lead to new therapies.

Whereas allergic asthma was traditionally considered a TH2-associated disease mediated by T helper type 2 (TH2) cells [22], recent studies have shown a role for ILCs in the development of asthma, and their distinct roles in various forms of asthma such as virus-induced asthma, obesity-related asthma, as well as neutrophilic asthma [7, 8, 23, 24]. Therefore, understanding the mechanisms underlying each asthma phenotype will foster the development of improved and more appropriate therapeutic strategies for asthma.

Heterogeneity of the innate lymphoid cell family

ILCs lack rearranged antigen-specific receptors and are therefore, antigen nonspecific. However, ILCs react rapidly to a wide range of environmental triggers that induce cytokine production in epithelial cells and other immune cells, e.g., IL-33, IL-25, and TSLP, which then profoundly affect ILC growth and differentiation. ILCs play divergent roles in tissue homeostasis, repair, as well as inflammation [25]. ILCs were first characterized by several different groups in 2010 as cells that produced large quantities of IL-5 and IL-13 in response to IL-25 and IL-33. Moro et al. identified a population of lineage-negative cells expressing c-kit, Sca-1, IL-33 receptor T1/ST2 (IL1RL1), IL-7 receptor and CD25 in fat-associated lymphoid clusters (FALCs) that they termed “natural helper cells” [26]. Following this, Neill et al. described “nuocytes”, lineage-negative cells producing large amounts of IL-13 after IL-25 administration or helminth infection with Nippostrongylus brasiliensis [10]. Subsequently, Price et al., using IL-4 and IL-13 reporter mice, identified “innate helper type 2 cells (Id2 cells)” in mesenteric lymph nodes, spleen, and liver, which respond to IL-25 (and IL-33) [27]. In 2013, the nomenclature and definition of these cell types was agreed by consensus as “Innate lymphoid cells (ILCs)” [6].

Accordingly, ILCs have since been classified into three groups, depending on the expression of effector cytokines and transcription factors: ILC1s, ILC2s, and ILC3s; this classification mirrors, for the most part, the phenotypic and functional characteristics of the respective T-cell subsets (type 1 (TH1), type 2 (TH2) and type 3 (TH17 and TH22) [25]. Developmentally, the ILCs develop from CLPs (common lymphoid progenitors), which also give rise to T- and B-cell LPs (lymphoid progenitors). NK (Natural killer) cells develop from an intermediate progenitor distinct from that of the CHILP (common helper ILC precursor) that gives rise to the “helper-like” ILC lineages ILC1, ILC2, and ILC3, which are the counterparts of the TH1, TH2, TH3 subsets [28, 29]. NK cells express the transcription factors T-bet (T-box transcription factor) and eomesodermin (Eomes) [30] [31]. Although cytotoxic NK cells share some phenotypic characteristics such as T-bet and IFN-γ expression with the non-cytotoxic ILC1 lineage, they express perforin and granzymes, and are thought to be distinct from ILC1s. Thus, NK cells more closely reflect the characteristics of CD8+ T cells, and could be considered as their innate counterpart. Developmentally, all ILCs, except NK cells and LTi cells, develop from common helper ILC precursors (ChILPs) which express Id2 and PLZF (promyelocytic leukaemia zinc finger protein) [28, 29]. ILC1s produce IFN-γ and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α, and express T-bet, but do not express Eomes [29]. ILC2s produce a set of cytokines similar to that produced by TH2 cells such as IL-5, IL-9, and IL-13 [10, 26, 32], and require the transcription factors RORα [33, 34] and Bcl11b [35, 36] for their development and maturation. ILC2s have been shown to mediate AHR and lung inflammation in several models, which will be described in detail in the following sections of this review. Group 3 ILCs (ILC3s) produce IL-17A, IL-22, granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and TNF-α. ILC3s display further heterogeneity and may be subdivided into several subgroups, such as CCR6+ LTis and CCR6− ILC3s [37]. Although usually grouped with ILC3s, lymphoid tissue inducer (LTi) cells have been shown to be developmentally PLZF-independent [28, 38], CCR6+, and consist of two subpopulations, CD4+ LTi cells or CD4− LTi cells [39]. CCR6− ILC3 cells can be subdivided based on the expression of natural cytotoxicity receptor (NCR) [40]. Although RAR-related orphan receptor gamma T (RORγt) is a key transcription factor for ILC3 development, T-bet is required for upregulation of NKp46 expression on CCR6− ILC3 cells [29, 40, 41]. The fact that ILC1s and ILC3s share some transcription factors for their development suggests that they may be functionally plastic in response to environmental stimuli.

ILC2s in allergic asthma

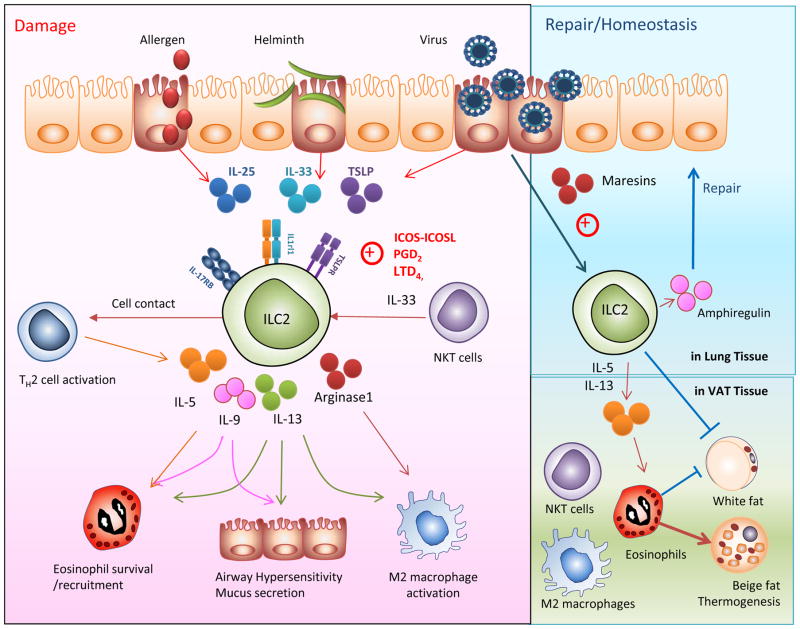

The discovery of ILC2 cells in the lungs, where they can produce high levels of type 2 cytokines such as IL-5 and IL-13, provided a breakthrough in understanding of the cell types and innate pathways underlying the development of asthma. In the naïve mouse, pulmonary ILC2s have been shown to express CD25, CD90, CD127, ICOS and variable amounts of CD117, ST2 (IL1rl1), and IL-17RB [42] (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Two faces of ILC2 cells: pathogenic and protective functions in asthma.

(A)In response to allergen, helminth or viral infection, or sensed “danger” signals, airway epithelial cells release innate cytokines, particularly interleukin-25 (IL-25), interleukin-33 (IL-33), and thymic stromal lymphopoeitin (TSLP), which activate ILC2s and initiate an inflammatory cascade leading to lung inflammation and hyperreactivity. Activated ILC2s produce Type 2 cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, IL-9 and IL-13. IL-4 subsequently stimulates Th2 cells, IL-5 induces eosinophilic inflammation, IL-9 induces airway hypersensitivity and IL-13 causes airway hypersensitivity as well as activation of M2 macrophages. ILC2s also produce arginase-1 which stimulates M2 macrophages. NKT cells directly interact with macrophages, inducing further IL-33 production to stimulate ILC2s. (B) In contrast, ILCs also participate in lung and metabolic homeostasis. ILC2s produce amphiregulin, which promotes repair of the airway epithelium. ILC2s and NKT cells sustain eosinophils and M2 macrophages by secretion of type 2 cytokines including IL-5 and IL-13, and promote beige fat biogenesis. The ILC2-eosinophil axis protects from metabolic dysregulation and protects against obesity-associated asthma.

Several studies have shown an important role for ILC2 cells in allergen-induced asthma [43–45]. In an OVA allergen-induced mouse model of asthma, ILC2s were shown to expand in the lungs and provide an innate source of IL-13 [43]. Moreover, both ILC2s and TH2 cells produced IL-5 and IL-13 in mice exposed to HDM or OVA [45]. Papain, a protease-containing allergen, was shown to induce eosinophilia and mucus hypersecretion in Rag1−/− mice. RAGs encode enzymes required for immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor rearrangement during the process of VDJ recombination, therefore, Rag1−/− mice do not contain mature B and T lymphocytes but still have ILCs. However, papain did not induce eosinophilia and mucus hypersecretion in Rag2−/− Il2rg−/− mice, due to the absence of ILCs. Il2rg−/− mice (interleukin 2 receptor, gamma chain) lack functional receptors for many cytokines, in particular IL-7, which is critical for ILC development. Therefore the Rag2−/− Il2rg−/− lack ILCs and adaptive immunity, suggesting that ILC2s are critical for the development of papain-induced asthma [44].

ILC2s express both IL17RB, the receptor for IL-25, and T1/ST2 (IL1RL1), the receptor for IL-33 [10]. Intranasal administration of IL-25 or IL-33 to mice has been shown to induce the activation and proliferation of pulmonary ILC2s, resulting in the development of AHR and goblet cell hyperplasia independently of adaptive immune responses [43, 46, 47]. Following IL-25 and IL-33 administration, ILC2s accumulating in the lung are the major source of the type 2 cytokines IL-13 and IL-5 which are critical for the development of AHR and airway inflammation [45] (Figure 2). IL-33 induces ILC2 activation and pulmonary contraction more effectively than IL-25 [48], although IL-25 stimulates several other cell types which produce type 2 cytokines, including type 2 myeloid (T2M) cells [49], MPP (multipotent progenitor) type 2 cells [50], TH2 cells and type 2 iNKT cells [51]. In addition, allergen provocation of asthmatic subjects with house dust mite (HDM), pollen or cat, selected based on the sensitivity of the patient, was shown to enhance IL-25 receptor expression on mast cells, eosinophils, endothelial cells and T cells in asthmatic bronchial mucosa and skin dermis of atopic subjects [52]. Binding of IL-25 to its receptor on such cells can activate cytokine production that further amplifies lung inflammation.

In humans, ILC2s defined by expression of CD127, CRTH2 and CD161, were identified in various tissues including lung, sinus mucosa of individuals with chronic rhinosinusitis, and peripheral blood [53, 54]. The prevalence of ILC2s in blood was higher in subjects with allergic asthma, and PBMCs from allergic subjects produced greater amounts of IL-5 and IL-13 in response to IL-25 or IL-33 than control subjects [55]. Human genome-wide association studies have reproducibly found an association between genetic variants in IL33 and IL1RL1 (the IL-33 receptor) and asthma [56–58]. IL-33 expression is higher in asthmatic patients [59]. A key role for IL-33-driven ILC2s in atopic dermatitis has also been demonstrated [60]. Together these studies indicate an important role for innate-driven responses in atopic disease and asthma (Figure 1).

IL-33 coordinates an innate Type 2 response not only by activating ILC2s and TH2 cells, but also by activating several innate cell types, including mast cells, basophils and eosinophils, all of which express the IL-33 receptor T1/ST2 (IL1rl1) and are also involved in Type 2 inflammation. When triggered by IL-33, mast cells, basophils and eosinophils can induce or potentiate Type 2 inflammation, independently of adaptive TH2 cells. IL-33 induces degranulation, strong eicosanoid and proinflammatory cytokine production in IgE-sensitized mast cells, and mediates anaphylactic shock in mice, and acts in synergy with stem cell factor and the IgE receptor on human mast cells and basophils [61]. In addition, IL-33 enhances the survival of eosinophils and eosinophil degranulation in humans [62], serving to potentiate the allergic lung response. Moreover, mast cells can produce IL-33 and eosinophils can produce IL-13, amplifying the allergic immune response, independently of TH2 cells. Therefore, IL-33 plays an important role in type 2 inflammation in the lung, by expanding not only ILC2s, but also all of the other cell types commonly associated with allergic inflammation.

Recent studies revealed that murine ILC2 cells may produce not only IL-5 and IL-13 but also IL-9 [32, 63]. Pulmonary ILC2s have been shown to produce IL-9 after the administration of papain or helminth infection in mouse lungs [32, 63]. IL-9 produced by ILC2 cells promotes ILC2 survival by inducing upregulation of the anti-apoptotic protein, Bcl3 [63], and inducing IL-5 and IL-13 production in an autocrine manner [32]. IL-9 signaling also contributes to mast cell accumulation, airway eosinophilia, and mucus production. IL-9 signaling has also been shown, however, to be important in the restoration of lung integrity and function, since it promotes worm expulsion and production of amphiregulin by ILC2s [63]. Interestingly, ILC2s, which express the cysteinyl leukotriene receptor CysLT1R, were shown to produce IL-4 in addition to IL-5 and IL-13 when stimulated with leukotriene D4 (LTD4), but not when stimulated with IL-33 [64]. LTD4 also enhanced ILC2 proliferation [64]. Leukotrienes have long been known to be important mediators in human asthma [65], and this finding demonstrates that ILC2s are an additional target for their activities.

Most studies have focused on the role of ILC2s in asthma using mouse models with short term exposure of allergens, referred to as “innate-type asthma”. However, the role of ILC2 cells in chronic asthma remains to be elucidated. For example, Il1rl1−/− mice manifested normal AHR responses after sensitization and challenge with OVA, and the recall response to recurring antigen exposures preferentially triggered CD4+ Th2 cells rather than ILC2s [66]. A recent study demonstrated that IL-33-ST2 signals selectively enhanced IL-5 production by memory Th2 cells, resulting in eosinophilic airway inflammation and AHR, indicating the critical importance of memory Th2 cells in the pathogenesis of chronic asthma [67]. Therefore, the role of ILC2s in the initiation of asthma versus the maintenance and resolution phases of allergic inflammation appears to differ and requires further investigation.

In humans, exposure to airborne allergens is considered an important risk factor for asthma, and exposure to fungi such as Alternaria and Aspergillus is associated with exacerbation of asthma [68, 69]. Recent studies have examined AHR and lung inflammation in mice following exposure to combinations of aeroallergens such as house dust mite or ryegrass with fungal extracts. These aeroallergens were found to act synergistically, and mice exposed to house dust mite or ryegrass plus Alternaria and/or Aspergillus developed robust eosinophilic airway inflammation, AHR, and type 2 cytokine responses. Both TH2 cell recruitment and ILC2 expansion were observed in the lungs of mice exposed to aeroallergens and contributed to airway pathogenesis [70–72]. In mice [70, 71] as well as in pediatric patients with fungal sensitization [69], exposure to Alternaria was associated with higher airway IL-33 levels and type 2 cytokine production (Figure 1). Il1rl1−/− and Tslpr−/− (Thymic Stromal Lymphopoietin (TSLP) receptor) mice showed significant reduction of airway inflammation, IgE production and AHR following airborne allergen exposure compared with WT mice, indicating the importance of these cytokines in orchestrating a network of innate and adaptive Th2 responses and airway pathology [71, 72].

ILC2s themselves were shown to rapidly produce type 2 cytokines in response to airborne allergens [72, 73]. Exposure of Rag1−/− mice to Alternaria induced a rapid increase in IL-33 production [72]. IL-5 and IL-13 production in Rag1−/− mice was similar to that of wild-type mice, suggesting that these responses occur independently of adaptive immunity [72]. In another study, the fungal molecule chitin was shown to initiate innate type 2 lung inflammation by stimulating expression of the epithelial cytokines IL-25, IL-33 and TSLP, which activated ILC2s to produce IL-5 and IL-13, and was necessary for accumulation of eosinophils and alternatively activated macrophages (AAMs) [73], also referred to as M2 macrophages [74]. Interestingly, ablation of ILC2s in Rag1−/− mice increased the activation of IL-17A-producing γδ T cells [64] and neutrophilic inflammation of the airways following chitin challenge. Therefore, while ILC2 activation promotes type 2 immunity and eosinophilia, ILC2 activation may also inhibit γδ T-cell-mediated neutrophilic airway inflammation [73]. Taken together, these studies indicate the previously unrecognized and key roles of ILC2s in the development of various forms of allergic asthma.

ILC2s in lung inflammation associated with viral infections

Viral infections are important triggers of asthma exacerbations in most patients with asthma, regardless of the presence of allergies. At least 50% of exacerbations in adults and children are associated with viral infections [19]. Several viruses such as rhinoviruses (RV), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), influenza and parainfluenza viruses, human metapneumovirus, and adenoviruses have been shown to contribute to asthma exacerbations [20]. Viral infections occur mainly in the epithelium of the conducting airways and trigger airway epithelial cell (AEC) production of a variety of pro-inflammatory cytokines [75], such as TSLP [24], IL-33, [7, 76, 77] and IL-25 [23, 46, 78], presumably by causing cellular injury and/or pyroptosis [7, 76, 77], all of which have been shown to contribute to ILC2 expansion [73] (Figure 1). In addition to airway epithelial cells, alveolar macrophages, type II pneumocytes, and DCs have been shown to produce IL-33 during viral infection [7, 76, 77].

For example, in a provocative study, Beale et al. showed that IL-25, which was expressed in high levels in asthmatic subjects following experimental RV infection, is a key mediator of RV-induced pulmonary inflammation [78]. Other studies have shown that following RV infection, IL-25 produced by murine AEC [23] and IL-33 induced in human primary BECs [79] stimulated the expansion and activation of ILC2s. Finally, infection with RSV has been associated with subsequent development of asthma, independent of allergen challenge [80]. Infection of AEC with RSV stimulates production of TSLP in both human and mouse [24]. Moreover, AEC from asthmatic children produced significantly higher levels of TSLP after RSV infection than cells from healthy children [24]. Altogether, these findings suggest that pulmonary virus infection might stimulate ILC2s to induce the development of asthma.

Influenza virus is another important respiratory pathogen that causes significant morbidity and mortality in patients with asthma. Using experimental models of asthma, we and others have shown that influenza A virus (H3N1) can rapidly induce AHR by inducing the activation of ILCs independently of the adaptive immune system [7, 81]. Influenza virus infection induced IL-33 secretion from alveolar macrophages, DC [7] as well as NKT cells [81], which in turn induces ILC2 activation and subsequent production of IL-5 and IL-13, and accumulation of eosinophils in the lungs [81]. Although influenza A virus causes the acute development of AHR by stimulating ILC2s, in a Janus-like behavior, ILC2s also have a beneficial role during the recovery phase of infection of virus-induced AHR [9, 82]. In this respect, ILC2s promote lung homeostasis by producing amphiregulin (Figure 2, upper right), and depletion of ILCs has been shown to result in loss of airway epithelial integrity and diminished lung function in mice [9]. Similarly, ILC2s in the lung produce arginase-1 which stimulates M2 macrophages and is thought to have a regulatory role during allergic inflammation [83, 84]. Taken together, improving our understanding of the links between ILC2s, virus-induced epithelial injury, and virus-induced asthma exacerbations may provide novel therapeutic approaches for the treatment of lung inflammation associated with viral infection.

ILCs in non-Th2 type of asthma

For many years the focus of research on asthma and its treatment was on allergic asthma, mediated by type 2 responses and driven by TH2 cells. However, many clinical and experimental studies performed over the last 10 years have indicated that asthma is a much more heterogeneous and complex disease than indicated by mouse models of allergic asthma. Non-allergic forms of asthma, triggered by environmental factors such as air pollutants, or obesity-associated asthma and neutrophilic asthma, all appear to occur independently of TH2 cells (Figure 1) [2]. Obesity has been shown to be a major risk factor for the development of asthma, particularly a severe, steroid-resistant form of asthma [17, 18]. In some studies, obese patients were found to have elevated levels of sputum IL-5 and submucosal eosinophils, but not sputum eosinophils [85, 86] suggesting that eosinophils may play a role in this disease phenotype. However, researchers have recently recognized the role of IL-17A and type 3 immunity in the development of asthma in mice and humans [8, 87, 88]. These studies have shown that IL-17A production by pulmonary Th17 cells or direct administration of recombinant IL-17A into the lungs can induce airway inflammation and AHR by inducing contraction of smooth muscle cells. Moreover, IL-17A in the sputum or peripheral blood of asthmatics is correlated with the severity of asthma [89, 90] and associated with airway neutrophilia [89] (Figure 1).

Using a mouse model of obesity, we demonstrated that mice fed a high-fat diet spontaneously developed AHR and had significant numbers of CCR6+ ILC3s producing IL-17A, a potent neutrophil chemotactic agent, in their lungs (Figure 1) [8], suggesting an important role for IL-17A in asthma associated with obesity. ILC3s were also observed in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients with asthma [8]. This study also demonstrated the critical role of IL-1β produced by M1 macrophages in the lungs and adipose tissue, which rapidly stimulated ILC3s to produce IL-17A, (Figure 1). Associated with type 1 responses, M1 macrophages, which increase inflammation and activate immune responses [74], have been shown to increase in number in adipose tissue in obese patients [91].

Although ILC2s in the lungs have been shown to enhance airway inflammation, a protective role for ILC2s in VAT in the development of obesity has been recently demonstrated [92–94] (Figure 2, lower right). ILC2s are resident in VAT and are the major source of IL-5 and IL-13, cytokines which promote the accumulation of eosinophils and M2 macrophages. Associated with Type 2 cytokines, M2 macrophages play key anti-inflammatory roles in VAT [95]. Moreover, ILC2s control adiposity in mice by increasing caloric expenditure via production of enkephalin peptides, which elicit the beiging of fat, which in turn provides defense against cold and obesity [93]. Investigators have determined that IL-33 or IL-25 are critical for the maintenance of ILC2s in WAT (white adipose tissue) or beige fat [92–94]. Together, these studies indicate that ILC2s in VAT provide protection from fat-associated inflammatory pathology, which can lead to metabolic syndrome and obesity-associated asthma. However, it may be that while ILC2s play a protective role in healthy adipose tissue, the overall type 2 responsiveness is supplanted by type 3 responses in the adipose tissue of obese individuals, resulting in a relative deficiency of these protective ILC2s in the tissue and the development of obesity-associated asthma.

Innate cells in steroid-resistant asthma

A significant proportion of patients with asthma develop resistance to corticosteroid treatments, resulting in a form of asthma that is difficult to treat and which is associated with significant morbidity and high severity [96]. In a mouse model of asthma induced by OVA/allergen sensitization, treatment with dexamethasone generally attenuated airway inflammation [97], consistent with the experience in patients with corticosteroid-responsive asthma. In contrast, when mice were challenged with OVA plus IL-33, researchers observed persistent numbers of ILC2s and considerable production of type 2 cytokines despite dexamethasone treatment [97]. In this study, TSLP was found to play a pivotal role in corticosteroid resistance, by controlling phosphorylation of STAT5 and expression of Bcl-xL in ILC2s [97]. Furthermore, high levels of the ILC2-inducing cytokine IL-33 were associated with resistance to oral steroid therapy in severe pediatric asthma with fungal sensitization [69]. In the same study, exposure of mice to A. alternata resulted in increased numbers of IL-33-mediated ILC2 cells and steroid-resistant AHR [69]. These findings suggest that in corticosteroid-resistant forms of asthma driven by IL-33 and fungal sensitization, as well as in allergen-driven asthma, ILC2 cells play a critical role and may be a potential therapeutic target.

In addition to ILC2s, a recently described innate cell type termed type 2 myeloid (T2M) cells, which expands following repeated allergen exposure, has been shown to mediate a steroid-resistant form of asthma (Figure 1) [49]. Interestingly, administration of IL-25 after repeated allergen exposure induced IL-4 and IL-13 production predominantly in T2M cells and not in ILC2s, and high-dose dexamethasone treatment failed to regulate this pulmonary T2M response. The response was dependent on the IL-25 receptor (IL-17RB) since Il17rb−/− mice showed lower inflammation and decreased type 2 cytokine production from T2M cells [49].

As discussed above, obesity-induced asthma is often steroid-resistant and associated with the presence of IL-17A. In some patients with steroid-resistant asthma, significantly increased levels of both IL-17A and IFN-γ [98] are observed. IL-17A produced by CD4+ T cells can also induce AHR and airway inflammation. Thus, in a mouse asthma model, CD4+ TH17 cells were shown to induce AHR, which was not attenuated by dexamethasone treatment [87]. In a separate report, IL-17A produced by αβ T cells was shown to drive AHR in mice and directly enhance both mouse and human smooth muscle contraction [88]. Altogether, these results suggest that innate cells including ILC2s, ILC3s, and T2M as well as CD4+ TH17, may be associated with the development of a steroid-resistant asthma phenotype (Figure 1). Therefore, the relationships between these innate and adaptive immune cells, and the signaling pathways associated with steroid resistance require further study, and such studies may lead to improved treatments for corticosteroid-resistant asthma patients.

Crosstalk between ILC2s and other immune cells in airway inflammation

ILC2s and TH2 cells

A body of evidence now demonstrates that ILCs have important roles in the development of asthma, even in the absence of adaptive immunity. However, the interaction between ILC2s and TH cells in the development of asthma is not fully understood. Upon stimulation, ILCs expand and secrete cytokines rapidly, suggesting they contribute to the initiation or potentiation of adaptive immunity. Several recent studies demonstrated that ILC2 and T-cell crosstalk contributed to their mutual maintenance, expansion and function [10, 99, 100]. ILCs express MHC class II (MHCII), and have been shown to process and present antigen to potentiate CD4+ T-cell responses [10, 100]. For example, Oliphant et al. demonstrated that MHCII-expressing ILC2s interact with antigen-specific T cells to promote Nippostrongylus brasiliensis expulsion [100]. The presence of MHCII on the ILC2s was required, since deletion of MHCII rendered the ILC2s incapable of inducing N. brasiliensis expulsion [100]. Mirchandani et al. showed that ILC2s and T cells potently stimulate each other’s function in vitro [99]. IL-2 production by CD4+ T cells stimulated type 2 cytokine production by ILC2s, while ILC2s modulated naïve CD4+ T-cell activation, favoring TH2-cell differentiation.

With respect to how this interaction contributes to airway inflammation, Gold et al. showed that ILC2s are critical for the adaptive immune response to inhaled allergens [101]. Multiple intranasal injections of HDM into mice induced the development of allergic lung inflammation including the recruitment of eosinophils, TH2-cell differentiation, and IgE production. In contrast, systemic priming with OVA with or without adjuvant, followed by respiratory exposure to OVA, circumvented the requirement for ILC2s in inducing TH2-driven lung inflammation [101]. Taken together, it is clear that ILC2s and TH2 cells amplify each other, and that the crosstalk between ILC2s and T cells is an important component of lung inflammation.

ILC2s, NKT cells and M2 macrophages

NKT (Natural Killer T) cells are innate immune cells that express an invariant TCR, and the role of NKT cells in asthma has been demonstrated using various animal models of asthma induced by allergen, viral infection, ozone exposure, or bacterial components [102]. Since NKT cells have been shown to induce AHR in the absence of adaptive immunity, NKT cells and ILCs may interact to induce AHR. This hypothesis was examined in a study using glycolipid antigens in a murine model of asthma [56]. Glycolipid antigens directly activated NKT cells, which in turn were shown to stimulate the production of IL-33 from alveolar macrophages (AM) [76]. IL-33 then activated ILC2 cells as well as NKT cells to increase production of IL-13, which correlated with increased AHR [76] (Figure 2). Moreover, following influenza virus infection, NKT cells have been shown to be a direct source of IL-33 production, in addition to AMs [81].

Another interesting study examined the relationship between ILC2s, NKT cells, and macrophages using an obese mouse model [94]. Administration of IL-25 to obese mice resulted in decreased body weight and adipose tissue volume and improved glucose tolerance. This was associated with increased infiltration of ILC2s, NKT cells, eosinophils, as well as M2 macrophages into the visceral adipose tissue (VAT). Similarly, transferring ILC2 or NKT cells into obese mice induced transient weight loss and stabilized glucose homeostasis, suggesting a beneficial regulatory role for these cells in protection against obesity. Although this study examined the interactions of ILCs and NKT cells in adipose tissue, these results suggest the possibility of ILC2 crosstalk with other innate immune cells such as NKT cells and AMs in multiple tissues beyond the adipose tissue [73].

ILC2s and eosinophils

Allergic asthma is characterized by lung eosinophilia controlled by type 2 cytokines. IL-5 and chemokines such as eotaxin mediate eosinophil development, survival, and tissue recruitment. ILC2 cells in the lung constitutively produce IL-5, suggesting that ILC2s contribute to eosinophil homeostasis [95, 103] (Figure 2). Despite the constitutive presence of IL-5 locally, few eosinophils are present in the lung at baseline. However, when ILC2s are stimulated by infection or inflammation, ILC2s upregulate IL-13 production and stimulate epithelial production of eotaxins, including eotaxin-1 (CCL11) [103].

Interestingly, eosinophils are abundant in the small intestine where eotaxin is present constitutively and ILC2s co-express IL-5 and IL-13. Expression levels of IL-5 and IL-13 by intestinal ILC2s are modulated by nutrient intake. ILC2s respond to vasoactive peptide (VIP) through the VPAC2 receptor and release IL-5, which is associated with increased eosinophil levels. Therefore, ILC2s sustain eosinophils by secretion of cytokines and chemokines, and this regulation is dependent on multiple external factors [103].

Further studies demonstrated the importance of ILC2s in VAT, where, as the major source of IL-5 and IL-13, ILC2s promote activation of eosinophils and M2 macrophages, critical for metabolic homeostasis and insulin sensitivity [92] [94, 95]. IL-5 deficiency was shown to result in impaired eosinophil accumulation, increased adiposity and insulin resistance. In contrast, IL-33 administration led to a rapid increase in eosinophils and M2 macrophages in VAT in an ILC2-dependent manner [95]. Depletion of ILC2s resulted in elevated weight gain whereas IL-25 treatment reduced obesity [94]. Other studies showed that ILC2- and eosinophil-derived type 2 cytokines promote beige fat biogenesis [92, 93] by stimulating PDGFRα+ adipocyte precursors via IL-4Rα signaling. Taken together, these results highlight the importance of ILC2s in regulating metabolic homeostasis, and show that by type2-associated immune stimulation, the ILC2-eosinophil axis may serve to protect from metabolic dysregulation and protect against obesity-associated asthma (Figure 2).

Regulation strategy of asthma by targeting ILC2s

IL-25 and IL-33 receptor

As ILC2s were originally identified by their responsiveness to IL-25 and IL-33 [10, 26, 27], and pulmonary IL-25 and IL-33 production appears to be a consistent hallmark of allergen exposure, understanding the pathways of IL-25 and IL-33 will be important for regulating ILC2s and asthma. When IL-33 or IL-25 signaling pathways are defective, mice fail to develop AHR induced by virus, glycolipid, as well as allergen [7, 76, 104]. Exogenous IL-33 or IL-25 results in the activation of NF-kB and STAT5 which in turn drives IL-5 and IL-13 expression in ILC2s [105]. In addition, IL-33 can promote the translation of IL-13 protein through activation of the mTOR signaling pathway [106]. Thus, targeting the molecules related to IL-33 and IL-25 signaling may be a strategy to control the function of ILC2s. However, there are beneficial effects of IL-33, such as in obesity and in cardiovascular disease and in the development of CD8+ T cells during viral infection, so limiting IL-33 function requires caution.

Common γ-chain receptors

Cytokine signaling is important for ILC differentiation, homeostasis and function. ILC2 cells express IL-7Rα [26], IL-2Rα[10, 26], IL-9R [27, 32, 63], and IL-4Rα [64], and these signals are induced by common γ chain signaling which in turn activates the JAK3–STAT5 pathway, essential for the function of ILC2s [105]. Numerous in vitro studies of ILC2s have shown the role of IL-7Rα, IL-2Rα, IL-9R, and IL-4Rα in the activation of ILC2s in combination with IL-33 and/or IL-25 [10, 26, 27, 63, 64]. However, the in vivo role of these cytokines in regulating ILC2 cell function is uncertain. For example, while T cell-derived IL-2 augments ILC2 cell proliferation in vitro [99], the in vivo source of IL-2 for ILC2 cells is not clear. A recent study demonstrated that the major source of IL-2 essential for the development of eosinophilic crystalline pneumonia was supplied by ILC3s in the lung [107].

Lipid signaling

G proteins and their receptors have been shown to play a role in the activation of immune cells, smooth muscle cells, as well as airway epithelial cells and contribute to the pathogenesis of asthma [108]. The function of ILC2s is regulated through signaling via several GPCRs (G protein coupled receptors) [53, 64, 103, 109, 110]. GPCRs are known to be involved in immune-modulation and directly involved in suppression of TLR-induced immune responses from T cells. GPCRs described on ILC2 cells thus far are CRTH2, FPR2, CysLT1R, and VIP. One of the defining markers of human ILC2 cells is CRTH2 [53]. CRTH2 is a chemoattractant receptor that binds to prostaglandin D2 (PGD2), a major proinflammatory mediator released from activated mast cells. PGD2 has been shown to induce both human and mouse ILC2s to produce type 2 cytokines, including IL-5, IL-13 and IL-4 [109, 110]. Murine ILC2s express CysLT1R (Cysteinyl leukotrienes receptor 1), which enables signaling from cysteinyl leukotriene C4 (LTC4). Cysteinyl leukotrienes are induced by various stimuli and contribute to asthma pathogenesis. In ILC2s, LTC4 signaling via CysLT1R induces IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 production [64]. Moreover, murine ILC2s in the intestine and lungs express the vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) receptor VPAC2 [103]. The circadian synchronizer VIP stimulates ILC2s through the VPAC2 receptor to release IL-5 and IL-13. As a result, basal eosinophilopoiesis and tissue eosinophil accumulation is regulated by ILC2s, and this regulation can be tuned by nutrient intake and central circadian rhythms [81]. Human ILC2s have been shown to express FPR2, the receptor for the lipoxin A4 [109]. Lipoxin A4 transduces anti-inflammatory signaling into ILC2s to suppress IL-13 production. The finding that ILC2s express endogenous anti-inflammatory lipid receptors suggest the possibility of additional roles for ILC2s during resolution of inflammation.

Other known signaling pathways

ILC2s express the pro-survival molecule inducible T-cell costimulator, (ICOS) [10, 111], and ICOS:ICOS-ligand interaction promotes cytokine production and survival of ILC2s [111, 112]. Blocking ICOS:ICOS-ligand interaction or deficiency of ICOS on murine ILC2s reduced the development of AHR and lung inflammation [111]. Thus, the ICOS:ICOS-ligand signaling pathway could be a strong candidate for regulating ILC2 function (Figure 2). In addition, KLRG1 was shown to be expressed by mature ILC2s, both in the mouse and in humans [60, 113, 114]. More recently, Huang et al, have shown that inflammatory ILC2s (iILC2s) express high levels of KLRG1 in the lungs of Nippostrongylus brasiliensis- and Candida albicans-infected mice [114], indicating that KLRG1 expression can be a marker of specific subtype of ILC2s [114]. Binding of KLRG1, an inhibitory C-type lectin to E-cadherin, was shown to inhibit Gata3 expression, cytokine production and proliferation of ILC2s [60, 113], suggesting that promotion of KLRG1 ligation may negatively regulate ILC2 function.

Since ILC2 expansion, differentiation and activation involves a complex signaling network, understanding the molecular mechanisms that regulate ILC responses is critical for finding new therapeutic strategies of asthma. Targeting transcription factors, ILC modulators such as lipoxin A4 and KLRG1 could limit their pathologic potentials. However, since ILCs and T cells share numerous markers, finding specific targets that selectively regulate ILC responses might be considered. Since ILC2s have multiple beneficial effects in immune homeostasis, devising strategies targeting ILC2s to specifically inhibit airway inflammation may be difficult.

Concluding remarks

Following the initial identification and characterization of ILC2s in 2010, our knowledge of this novel cell type has expanded rapidly. In mice, ILC2s show both pathological and protective functions in virus- or allergen-induced allergic immune responses by producing type 2 cytokines and amphiregulin, respectively. Furthermore, ILC2s also work with many other immune cells, such as CD4+ T cells, macrophages, eosinophils, NKT cells as well as epithelial cells, to promote the development and persistence of allergic airway inflammation. However, the role of ILC2s in chronic and recurrent airway inflammation that is observed in human patients with asthma and other allergic diseases, such as atopic dermatitis and chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, has not been fully characterized. Further understanding of the contributions of ILC subsets and molecular mechanisms underlying their activation in asthma and other atopic diseases may lead to new therapies for this important health problem.

Acknowledgments

HYK is supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT& Future planning (2014R1AA1A3052488) and the Cooperative Research Program of Basic Medical Science and Clinical Science from Seoul National University College of Medicine (800-20140168). RDK is supported by National Institutes of Health Grants: PO1 AI-054456 (Freeman, DeKruyff, Umetsu) and R01 AI089955 (Freeman, DeKruyff).

Abbreviations

- AAMs

Alternatively activated macrophages

- AEC

Airway epithelial cell

- AHR

Airway Hyperreactivity

- AM

alveolar macrophages

- DC

Dendritic cells

- ILC

Innate Lymphoid Cell

- NK

Natural Killer

- NKT

Natural Killer T

- RSV

respiratory syncytial virus

- RV

rhinovirus

- T2M

Type 2 myeloid

- TSLP

Thymic Stromal Lymphopoietin

- VAT

Visceral adipose tissue

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

DTU is an employee of Genentech. The other authors declare no financial or commercial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Busse WW, Lemanske RF., Jr Asthma. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:350–362. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102013440507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim HY, DeKruyff RH, Umetsu DT. The many paths to asthma: phenotype shaped by innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:577–584. doi: 10.1038/ni.1892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Artis D, Spits H. The biology of innate lymphoid cells. Nature. 2015;517:293–301. doi: 10.1038/nature14189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eberl G, Colonna M, Di Santo JP, McKenzie AN. Innate lymphoid cells. Innate lymphoid cells: a new paradigm in immunology. Science. 2015;348:aaa6566. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa6566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hazenberg MD, Spits H. Human innate lymphoid cells. Blood. 2014;124:700–709. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-11-427781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spits H, Artis D, Colonna M, Diefenbach A, Di Santo JP, Eberl G, Koyasu S, Locksley RM, McKenzie AN, Mebius RE, Powrie F, Vivier E. Innate lymphoid cells--a proposal for uniform nomenclature. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:145–149. doi: 10.1038/nri3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang YJ, Kim HY, Albacker LA, Baumgarth N, McKenzie AN, Smith DE, Dekruyff RH, Umetsu DT. Innate lymphoid cells mediate influenza-induced airway hyper-reactivity independently of adaptive immunity. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:631–638. doi: 10.1038/ni.2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim HY, Lee HJ, Chang YJ, Pichavant M, Shore SA, Fitzgerald KA, Iwakura Y, Israel E, Bolger K, Faul J, DeKruyff RH, Umetsu DT. Interleukin-17-producing innate lymphoid cells and the NLRP3 inflammasome facilitate obesity-associated airway hyperreactivity. Nat Med. 2014;20:54–61. doi: 10.1038/nm.3423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monticelli L, Sonnenberg G, Abt M, Alenghat T, Ziegler C, Doering T, Angelosanto J, Laidlaw B, Yang C, Sathaliyawala T, Kubota M, Turner D, Diamond J, Goldrath A, Farber D, Collman R, Wherry E, Artis D. Innate lymphoid cells promote lung-tissue homeostasis after infection with influenza virus. Nature Immunol. 2011 doi: 10.1031/ni.2131. advance online pub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neill DR, Wong SH, Bellosi A, Flynn RJ, Daly M, Langford TK, Bucks C, Kane CM, Fallon PG, Pannell R, Jolin HE, McKenzie AN. Nuocytes represent a new innate effector leukocyte that mediates type-2 immunity. Nature. 2010;464:1367–1370. doi: 10.1038/nature08900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Croisant S. Epidemiology of asthma: prevalence and burden of disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;795:17–29. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-8603-9_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonnelykke K, Sparks R, Waage J, Milner JD. Genetics of allergy and allergic sensitization: common variants, rare mutations. Curr Opin Immunol. 2015;36:115–126. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Umetsu DT, McIntire JJ, Akbari O, Macaubas C, DeKruyff RH. Asthma: an epidemic of dysregulated immunity. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:715–720. doi: 10.1038/ni0802-715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pichavant M, Goya S, Meyer EH, Johnston RA, Kim HY, Matangkasombut P, Zhu M, Iwakura Y, Savage PB, DeKruyff RH, Shore SA, Umetsu DT. Ozone exposure in a mouse model induces airway hyperreactivity that requires the presence of natural killer T cells and IL-17. J Exp Med. 2008;205:385–393. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim HY, Chang YJ, Chuang YT, Lee HH, Kasahara DI, Martin T, Hsu JT, Savage PB, Shore SA, Freeman GJ, Dekruyff RH, Umetsu DT. T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 1 deficiency eliminates airway hyperreactivity triggered by the recognition of airway cell death. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:414–425. e416. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tamimi A, Serdarevic D, Hanania NA. The effects of cigarette smoke on airway inflammation in asthma and COPD: therapeutic implications. Respir Med. 2012;106:319–328. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Camargo CA, Jr, Weiss ST, Zhang S, Willett WC, Speizer FE. Prospective study of body mass index weight change and risk of adult-onset asthma in women. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:2582–2588. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.21.2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holguin F, Bleecker ER, Busse WW, Calhoun WJ, Castro M, Erzurum SC, Fitzpatrick AM, Gaston B, Israel E, Jarjour NN, Moore WC, Peters SP, Yonas M, Teague WG, Wenzel SE. Obesity and asthma: an association modified by age of asthma onset. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:1486–1493. e1482. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dougherty RH, Fahy JV. Acute exacerbations of asthma: epidemiology, biology and the exacerbation-prone phenotype. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:193–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03157.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson DJ, Johnston SL. The role of viruses in acute exacerbations of asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:1178–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.04.021. quiz 1188–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore WC, Meyers DA, Wenzel SE, Teague WG, Li H, Li X, D’Agostino R, Jr, Castro M, Curran-Everett D, Fitzpatrick AM, Gaston B, Jarjour NN, Sorkness R, Calhoun WJ, Chung KF, Comhair SA, Dweik RA, Israel E, Peters SP, Busse WW, Erzurum SC, Bleecker ER National Heart L. and Blood Institute’s Severe Asthma Research P. Identification of asthma phenotypes using cluster analysis in the Severe Asthma Research Program. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:315–323. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200906-0896OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robinson DS, Hamid Q, Ying S, Tsicopoulos A, Barkans J, Bentley AM, Corrigan C, Durham SR, Kay AB. Predominant Th2-like bronchoalveolar T-lymphocyte population in atopic asthma. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:298–304. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199201303260504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hong JY, Bentley JK, Chung Y, Lei J, Steenrod JM, Chen Q, Sajjan US, Hershenson MB. Neonatal rhinovirus induces mucous metaplasia and airways hyperresponsiveness through IL-25 and type 2 innate lymphoid cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee HC, Headley MB, Loo YM, Berlin A, Gale M, Jr, Debley JS, Lukacs NW, Ziegler SF. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin is induced by respiratory syncytial virus-infected airway epithelial cells and promotes a type 2 response to infection. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:1187–1196. e1185. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spits H, Di Santo JP. The expanding family of innate lymphoid cells: regulators and effectors of immunity and tissue remodeling. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:21–27. doi: 10.1038/ni.1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moro K, Yamada T, Tanabe M, Takeuchi T, Ikawa T, Kawamoto H, Furusawa J, Ohtani M, Fujii H, Koyasu S. Innate production of T(H)2 cytokines by adipose tissue-associated c-Kit(+)Sca-1(+) lymphoid cells. Nature. 2010;463:540–544. doi: 10.1038/nature08636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Price AE, Liang HE, Sullivan BM, Reinhardt RL, Eisley CJ, Erle DJ, Locksley RM. Systemically dispersed innate IL-13-expressing cells in type 2 immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11489–11494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003988107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Constantinides MG, McDonald BD, Verhoef PA, Bendelac A. A committed precursor to innate lymphoid cells. Nature. 2014;508:397–401. doi: 10.1038/nature13047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klose CS, Flach M, Mohle L, Rogell L, Hoyler T, Ebert K, Fabiunke C, Pfeifer D, Sexl V, Fonseca-Pereira D, Domingues RG, Veiga-Fernandes H, Arnold SJ, Busslinger M, Dunay IR, Tanriver Y, Diefenbach A. Differentiation of type 1 ILCs from a common progenitor to all helper-like innate lymphoid cell lineages. Cell. 2014;157:340–356. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gordon SM, Chaix J, Rupp LJ, Wu J, Madera S, Sun JC, Lindsten T, Reiner SL. The transcription factors T-bet and Eomes control key checkpoints of natural killer cell maturation. Immunity. 2012;36:55–67. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strowig T, Brilot F, Munz C. Noncytotoxic functions of NK cells: direct pathogen restriction and assistance to adaptive immunity. J Immunol. 2008;180:7785–7791. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.12.7785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilhelm C, Hirota K, Stieglitz B, Van Snick J, Tolaini M, Lahl K, Sparwasser T, Helmby H, Stockinger B. An IL-9 fate reporter demonstrates the induction of an innate IL-9 response in lung inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:1071–1077. doi: 10.1038/ni.2133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Halim TY, MacLaren A, Romanish MT, Gold MJ, McNagny KM, Takei F. Retinoic-acid-receptor-related orphan nuclear receptor alpha is required for natural helper cell development and allergic inflammation. Immunity. 2012;37:463–474. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wong SH, Walker JA, Jolin HE, Drynan LF, Hams E, Camelo A, Barlow JL, Neill DR, Panova V, Koch U, Radtke F, Hardman CS, Hwang YY, Fallon PG, McKenzie AN. Transcription factor RORalpha is critical for nuocyte development. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:229–236. doi: 10.1038/ni.2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walker JA, Oliphant CJ, Englezakis A, Yu Y, Clare S, Rodewald HR, Belz G, Liu P, Fallon PG, McKenzie AN. Bcl11b is essential for group 2 innate lymphoid cell development. J Exp Med. 2015;212:875–882. doi: 10.1084/jem.20142224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu Y, Wang C, Clare S, Wang J, Lee SC, Brandt C, Burke S, Lu L, He D, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Dougan G, Liu P. The transcription factor Bcl11b is specifically expressed in group 2 innate lymphoid cells and is essential for their development. J Exp Med. 2015;212:865–874. doi: 10.1084/jem.20142318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Montaldo E, Juelke K, Romagnani C. Group 3 innate lymphoid cells (ILC3s): Origin, differentiation, and plasticity in humans and mice. Eur J Immunol. 2015;45:2171–2182. doi: 10.1002/eji.201545598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ishizuka IE, Chea S, Gudjonson H, Constantinides MG, Dinner AR, Bendelac A, Golub R. Single-cell analysis defines the divergence between the innate lymphoid cell lineage and lymphoid tissue-inducer cell lineage. Nat Immunol. 2016 doi: 10.1038/ni.3344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sonnenberg GF, Artis D. Innate lymphoid cells in the initiation, regulation and resolution of inflammation. Nat Med. 2015;21:698–708. doi: 10.1038/nm.3892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klose CS, Kiss EA, Schwierzeck V, Ebert K, Hoyler T, d’Hargues Y, Goppert N, Croxford AL, Waisman A, Tanriver Y, Diefenbach A. A T-bet gradient controls the fate and function of CCR6-RORgammat+ innate lymphoid cells. Nature. 2013;494:261–265. doi: 10.1038/nature11813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rankin LC, Groom JR, Chopin M, Herold MJ, Walker JA, Mielke LA, McKenzie AN, Carotta S, Nutt SL, Belz GT. The transcription factor T-bet is essential for the development of NKp46+ innate lymphocytes via the Notch pathway. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:389–395. doi: 10.1038/ni.2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McKenzie AN. Type-2 innate lymphoid cells in asthma and allergy. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(Suppl 5):S263–270. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201403-097AW. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barlow JL, Bellosi A, Hardman CS, Drynan LF, Wong SH, Cruickshank JP, McKenzie AN. Innate IL-13-producing nuocytes arise during allergic lung inflammation and contribute to airways hyperreactivity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:191–198. e191–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Halim TY, Krauss RH, Sun AC, Takei F. Lung natural helper cells are a critical source of th2 cell-type cytokines in protease allergen-induced airway inflammation. Immunity. 2012;36:451–463. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Klein Wolterink RG, Kleinjan A, van Nimwegen M, Bergen I, de Bruijn M, Levani Y, Hendriks RW. Pulmonary innate lymphoid cells are major producers of IL-5 and IL-13 in murine models of allergic asthma. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:1106–1116. doi: 10.1002/eji.201142018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fort MCJ, Yen D, Li J, Zurawski SM, Lo S, Menon S, Clifford T, Hunte B, Lesley; R, Muchamuel T, Hurst SD, Zurawski G, Leach MW, Gorman DM, Rennick DM. IL-25 induces IL-4, IL-5, IL-13 and Th2-associated pathologies in vivo. Immunity. 2001;15:985–995. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00243-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kondo Y, Yoshimoto T, Yasuda K, Futatsugi-Yumikura S, Morimoto M, Hayashi N, Hoshino T, Fujimoto J, Nakanishi K. Administration of IL-33 induces airway hyperresponsiveness and goblet cell hyperplasia in the lungs in the absence of adaptive immune system. Int Immunol. 2008;20:791–800. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barlow JL, Peel S, Fox J, Panova V, Hardman CS, Camelo A, Bucks C, Wu X, Kane CM, Neill DR, Flynn RJ, Sayers I, Hall IP, McKenzie AN. IL-33 is more potent than IL-25 in provoking IL-13-producing nuocytes (type 2 innate lymphoid cells) and airway contraction. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:933–941. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Petersen BC, Budelsky AL, Baptist AP, Schaller MA, Lukacs NW. Interleukin-25 induces type 2 cytokine production in a steroid-resistant interleukin-17RB+ myeloid population that exacerbates asthmatic pathology. Nat Med. 2012;18:751–758. doi: 10.1038/nm.2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saenz SS, MC, Perrigoue JG, Spencer SP, Urban JF, Jr, Tocker JE, Budelsky AL, Kleinschek MA, Kastelein RA, Kambayashi T, Bhandoola A, Artis D. IL25 elicits a multipotent progenitor cell population that promotes T(H)2 cytokine responses. Nature. 2010;464:1362–1366. doi: 10.1038/nature08901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Watarai H, Sekine-Kondo E, Shigeura T, Motomura Y, Yasuda T, Satoh R, Yoshida H, Kubo M, Kawamoto H, Koseki H, Taniguchi M. Development and function of invariant natural killer T cells producing T(h)2- and T(h)17-cytokines. PLoS Biol. 2012;10:e1001255. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Corrigan CJ, Wang W, Meng Q, Fang C, Eid G, Caballero MR, Lv Z, An Y, Wang YH, Liu YJ, Kay AB, Lee TH, Ying S. Allergen-induced expression of IL-25 and IL-25 receptor in atopic asthmatic airways and late-phase cutaneous responses. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mjosberg JM, Trifari S, Crellin NK, Peters CP, van Drunen CM, Piet B, Fokkens WJ, Cupedo T, Spits H. Human IL-25- and IL-33-responsive type 2 innate lymphoid cells are defined by expression of CRTH2 and CD161. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:1055–1062. doi: 10.1038/ni.2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shaw JL, Fakhri S, Citardi MJ, Porter PC, Corry DB, Kheradmand F, Liu YJ, Luong A. IL-33-responsive innate lymphoid cells are an important source of IL-13 in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:432–439. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201212-2227OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bartemes KR, Kephart GM, Fox SJ, Kita H. Enhanced innate type 2 immune response in peripheral blood from patients with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:671–678. e674. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Grotenboer NS, Ketelaar ME, Koppelman GH, Nawijn MC. Decoding asthma: translating genetic variation in IL33 and IL1RL1 into disease pathophysiology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:856–865. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moffatt MF, Gut IG, Demenais F, Strachan DP, Bouzigon E, Heath S, von Mutius E, Farrall M, Lathrop M, Cookson WO, Consortium G. A large-scale, consortium-based genomewide association study of asthma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1211–1221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Torgerson DG, Ampleford EJ, Chiu GY, Gauderman WJ, Gignoux CR, Graves PE, Himes BE, Levin AM, Mathias RA, Hancock DB, Baurley JW, Eng C, Stern DA, Celedon JC, Rafaels N, Capurso D, Conti DV, Roth LA, Soto-Quiros M, Togias A, Li X, Myers RA, Romieu I, Van Den Berg DJ, Hu D, Hansel NN, Hernandez RD, Israel E, Salam MT, Galanter J, Avila PC, Avila L, Rodriquez-Santana JR, Chapela R, Rodriguez-Cintron W, Diette GB, Adkinson NF, Abel RA, Ross KD, Shi M, Faruque MU, Dunston GM, Watson HR, Mantese VJ, Ezurum SC, Liang L, Ruczinski I, Ford JG, Huntsman S, Chung KF, Vora H, Li X, Calhoun WJ, Castro M, Sienra-Monge JJ, del Rio-Navarro B, Deichmann KA, Heinzmann A, Wenzel SE, Busse WW, Gern JE, Lemanske RF, Jr, Beaty TH, Bleecker ER, Raby BA, Meyers DA, London SJ, Gilliland FD, Burchard EG, Martinez FD, Weiss ST, Williams LK, Barnes KC, Ober C, Nicolae DL Mexico City Childhood Asthma, S, Children’s Health, S., study, H, Genetics of Asthma in Latino Americans Study, S. o. G.-E, Admixture in Latino, A, Study of African Americans, A. G. Environments, Childhood Asthma, R. Education N., Childhood Asthma Management P., Study of Asthma P. Pharmacogenomic Interactions by R.-E., Genetic Research on Asthma in African Diaspora S. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies of asthma in ethnically diverse North American populations. Nat Genet. 2011;43:887–892. doi: 10.1038/ng.888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lloyd CM. IL-33 family members and asthma - bridging innate and adaptive immune responses. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22:800–806. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Salimi M, Barlow JL, Saunders SP, Xue L, Gutowska-Owsiak D, Wang X, Huang LC, Johnson D, Scanlon ST, McKenzie AN, Fallon PG, Ogg GS. A role for IL-25 and IL-33-driven type-2 innate lymphoid cells in atopic dermatitis. J Exp Med. 2013;210:2939–2950. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Silver MR, Margulis A, Wood N, Goldman SJ, Kasaian M, Chaudhary D. IL-33 synergizes with IgE-dependent and IgE-independent agents to promote mast cell and basophil activation. Inflamm Res. 2010;59:207–218. doi: 10.1007/s00011-009-0088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cherry WB, Yoon J, Bartemes KR, Iijima K, Kita H. A novel IL-1 family cytokine, IL-33, potently activates human eosinophils. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:1484–1490. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Turner JE, Morrison PJ, Wilhelm C, Wilson M, Ahlfors H, Renauld JC, Panzer U, Helmby H, Stockinger B. IL-9-mediated survival of type 2 innate lymphoid cells promotes damage control in helminth-induced lung inflammation. J Exp Med. 2013;210:2951–2965. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Doherty TA, Khorram N, Lund S, Mehta AK, Croft M, Broide DH. Lung type 2 innate lymphoid cells express cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1, which regulates TH2 cytokine production. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.03.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Singh RK, Tandon R, Dastidar SG, Ray A. A review on leukotrienes and their receptors with reference to asthma. J Asthma. 2013;50:922–931. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2013.823447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guo L, Huang Y, Chen X, Hu-Li J, Urban JF, Jr, Paul WE. Innate immunological function of TH2 cells in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:1051–1059. doi: 10.1038/ni.3244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Endo Y, Hirahara K, Iinuma T, Shinoda K, Tumes DJ, Asou HK, Matsugae N, Obata-Ninomiya K, Yamamoto H, Motohashi S, Oboki K, Nakae S, Saito H, Okamoto Y, Nakayama T. The interleukin-33-p38 kinase axis confers memory T helper 2 cell pathogenicity in the airway. Immunity. 2015;42:294–308. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bush RK, Prochnau JJ. Alternaria-induced asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Castanhinha S, Sherburn R, Walker S, Gupta A, Bossley CJ, Buckley J, Ullmann N, Grychtol R, Campbell G, Maglione M, Koo S, Fleming L, Gregory L, Snelgrove RJ, Bush A, Lloyd CM, Saglani S. Pediatric severe asthma with fungal sensitization is mediated by steroid-resistant IL-33. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Iijima K, Kobayashi T, Hara K, Kephart GM, Ziegler SF, McKenzie AN, Kita H. IL-33 and thymic stromal lymphopoietin mediate immune pathology in response to chronic airborne allergen exposure. J Immunol. 2014;193:1549–1559. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kouzaki H, Iijima K, Kobayashi T, O’Grady SM, Kita H. The Danger Signal, Extracellular ATP, Is a Sensor for an Airborne Allergen and Triggers IL-33 Release and Innate Th2-Type Responses. Journal of Immunology. 2011;186:4375–4387. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Doherty TA, Khorram N, Chang JE, Kim HK, Rosenthal P, Croft M, Broide DH. STAT6 regulates natural helper cell proliferation during lung inflammation initiated by Alternaria. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;303:L577–588. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00174.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Van Dyken SJ, Mohapatra A, Nussbaum JC, Molofsky AB, Thornton EE, Ziegler SF, McKenzie AN, Krummel MF, Liang HE, Locksley RM. Chitin activates parallel immune modules that direct distinct inflammatory responses via innate lymphoid type 2 and gammadelta T cells. Immunity. 2014;40:414–424. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Martinez FO, Gordon S. The M1 and M2 paradigm of macrophage activation: time for reassessment. F1000Prime Rep. 2014;6:13. doi: 10.12703/P6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bulek K, Swaidani S, Aronica M, Li X. Epithelium: the interplay between innate and Th2 immunity. Immunol Cell Biol. 2010;88:257–268. doi: 10.1038/icb.2009.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kim HY, Chang YJ, Subramanian S, Lee HH, Albacker LA, Matangkasombut P, Savage PB, McKenzie AN, Smith DE, Rottman JB, DeKruyff RH, Umetsu DT. Innate lymphoid cells responding to IL-33 mediate airway hyperreactivity independently of adaptive immunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:216–227. e211–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Le Goffic R, Arshad MI, Rauch M, L’Helgoualc’h A, Delmas B, Piquet-Pellorce C, Samson M. Infection with influenza virus induces IL-33 in murine lungs. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;45:1125–1132. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0516OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Beale J, Jayaraman A, Jackson DJ, Macintyre JD, Edwards MR, Walton RP, Zhu J, Ching YM, Shamji B, Edwards M, Westwick J, Cousins DJ, Hwang YY, McKenzie A, Johnston SL, Bartlett NW. Rhinovirus-induced IL-25 in asthma exacerbation drives type 2 immunity and allergic pulmonary inflammation. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:256ra134. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jackson DJ, Makrinioti H, Rana BM, Shamji BW, Trujillo-Torralbo MB, Footitt J, Jerico DR, Telcian AG, Nikonova A, Zhu J, Aniscenko J, Gogsadze L, Bakhsoliani E, Traub S, Dhariwal J, Porter J, Hunt D, Hunt T, Hunt T, Stanciu LA, Khaitov M, Bartlett NW, Edwards MR, Kon OM, Mallia P, Papadopoulos NG, Akdis CA, Westwick J, Edwards MJ, Cousins DJ, Walton RP, Johnston SL. IL-33-dependent type 2 inflammation during rhinovirus-induced asthma exacerbations in vivo. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:1373–1382. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201406-1039OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Blanken MO, Rovers MM, Molenaar JM, Winkler-Seinstra PL, Meijer A, Kimpen JL, Bont L, Dutch RSVNN. Respiratory syncytial virus and recurrent wheeze in healthy preterm infants. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1791–1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gorski SA, Hahn YS, Braciale TJ. Group 2 innate lymphoid cell production of IL-5 is regulated by NKT cells during influenza virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003615. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wills-Karp M, Finkelman FD. Innate lymphoid cells wield a double-edged sword. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:1025–1027. doi: 10.1038/ni.2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bando JK, Nussbaum JC, Liang HE, Locksley RM. Type 2 innate lymphoid cells constitutively express arginase-I in the naive and inflamed lung. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;94:877–884. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0213084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Knippenberg S, Brumshagen C, Aschenbrenner F, Welte T, Maus UA. Arginase 1 activity worsens lung-protective immunity against Streptococcus pneumoniae infection. Eur J Immunol. 2015;45:1716–1726. doi: 10.1002/eji.201445419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Desai D, Newby C, Symon FA, Haldar P, Shah S, Gupta S, Bafadhel M, Singapuri A, Siddiqui S, Woods J, Herath A, Anderson IK, Bradding P, Green R, Kulkarni N, Pavord I, Marshall RP, Sousa AR, May RD, Wardlaw AJ, Brightling CE. Elevated sputum interleukin-5 and submucosal eosinophilia in obese individuals with severe asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:657–663. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201208-1470OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lloyd CM, Saglani S. Eosinophils in the spotlight: Finding the link between obesity and asthma. Nat Med. 2013;19:976–977. doi: 10.1038/nm.3296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.McKinley L, Alcorn JF, Peterson A, Dupont RB, Kapadia S, Logar A, Henry A, Irvin CG, Piganelli JD, Ray A, Kolls JK. TH17 cells mediate steroid-resistant airway inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness in mice. J Immunol. 2008;181:4089–4097. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.4089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kudo M, Melton AC, Chen C, Engler MB, Huang KE, Ren X, Wang Y, Bernstein X, Li JT, Atabai K, Huang X, Sheppard D. IL-17A produced by alphabeta T cells drives airway hyper-responsiveness in mice and enhances mouse and human airway smooth muscle contraction. Nat Med. 2012;18:547–554. doi: 10.1038/nm.2684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sun YC, Zhou QT, Yao WZ. Sputum interleukin-17 is increased and associated with airway neutrophilia in patients with severe asthma. Chin Med J (Engl) 2005;118:953–956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Agache I, Ciobanu C, Agache C, Anghel M. Increased serum IL-17 is an independent risk factor for severe asthma. Respir Med. 2010;104:1131–1137. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lumeng CN, Bodzin JL, Saltiel AR. Obesity induces a phenotypic switch in adipose tissue macrophage polarization. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:175–184. doi: 10.1172/JCI29881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lee MW, Odegaard JI, Mukundan L, Qiu Y, Molofsky AB, Nussbaum JC, Yun K, Locksley RM, Chawla A. Activated type 2 innate lymphoid cells regulate beige fat biogenesis. Cell. 2015;160:74–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Brestoff JR, Kim BS, Saenz SA, Stine RR, Monticelli LA, Sonnenberg GF, Thome JJ, Farber DL, Lutfy K, Seale P, Artis D. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells promote beiging of white adipose tissue and limit obesity. Nature. 2015;519:242–246. doi: 10.1038/nature14115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hams E, Locksley RM, McKenzie AN, Fallon PG. Cutting edge: IL-25 elicits innate lymphoid type 2 and type II NKT cells that regulate obesity in mice. J Immunol. 2013;191:5349–5353. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Molofsky AB, Nussbaum JC, Liang HE, Van Dyken SJ, Cheng LE, Mohapatra A, Chawla A, Locksley RM. Innate lymphoid type 2 cells sustain visceral adipose tissue eosinophils and alternatively activated macrophages. J Exp Med. 2013;210:535–549. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yim RP, Koumbourlis AC. Steroid-resistant asthma. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2012;13:172–176. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2011.05.002. quiz 176–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kabata H, Moro K, Fukunaga K, Suzuki Y, Miyata J, Masaki K, Betsuyaku T, Koyasu S, Asano K. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin induces corticosteroid resistance in natural helper cells during airway inflammation. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2675. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chambers ES, Nanzer AM, Pfeffer PE, Richards DF, Timms PM, Martineau AR, Griffiths CJ, Corrigan CJ, Hawrylowicz CM. Distinct endotypes of steroid-resistant asthma characterized by IL-17A and IFN-gamma immunophenotypes: Potential benefits of calcitriol. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mirchandani AS, Besnard AG, Yip E, Scott C, Bain CC, Cerovic V, Salmond RJ, Liew FY. Type 2 innate lymphoid cells drive CD4+ Th2 cell responses. J Immunol. 2014;192:2442–2448. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Oliphant CJ, Hwang YY, Walker JA, Salimi M, Wong SH, Brewer JM, Englezakis A, Barlow JL, Hams E, Scanlon ST, Ogg GS, Fallon PG, McKenzie AN. MHCII-mediated dialog between group 2 innate lymphoid cells and CD4(+) T cells potentiates type 2 immunity and promotes parasitic helminth expulsion. Immunity. 2014;41:283–295. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gold MJ, Antignano F, Halim TY, Hirota JA, Blanchet MR, Zaph C, Takei F, McNagny KM. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells facilitate sensitization to local, but not systemic, TH2-inducing allergen exposures. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1142–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Umetsu DT, Dekruyff RH. Natural killer T cells are important in the pathogenesis of asthma: the many pathways to asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:975–979. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nussbaum JC, Van Dyken SJ, von Moltke J, Cheng LE, Mohapatra A, Molofsky AB, Thornton EE, Krummel MF, Chawla A, Liang HE, Locksley RM. Type 2 innate lymphoid cells control eosinophil homeostasis. Nature. 2013;502:245–248. doi: 10.1038/nature12526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kearley J, Buckland KF, Mathie SA, Lloyd CM. Resolution of allergic inflammation and airway hyperreactivity is dependent upon disruption of the T1/ST2-IL-33 pathway. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:772–781. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200805-666OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Guo L, Junttila IS, Paul WE. Cytokine-induced cytokine production by conventional and innate lymphoid cells. Trends Immunol. 2012;33:598–606. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Salmond RJ, Mirchandani AS, Besnard AG, Bain CC, Thomson NC, Liew FY. IL-33 induces innate lymphoid cell-mediated airway inflammation by activating mammalian target of rapamycin. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:1159–1166. e1156. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Roediger B, Kyle R, Tay SS, Mitchell AJ, Bolton HA, Guy TV, Tan SY, Forbes-Blom E, Tong PL, Koller Y, Shklovskaya E, Iwashima M, McCoy KD, Le Gros G, Fazekas de St Groth B, Weninger W. IL-2 is a critical regulator of group 2 innate lymphoid cell function during pulmonary inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Druey KM. Regulation of G-protein-coupled signaling pathways in allergic inflammation. Immunol Res. 2009;43:62–76. doi: 10.1007/s12026-008-8050-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Barnig C, Cernadas M, Dutile S, Liu X, Perrella MA, Kazani S, Wechsler ME, Israel E, Levy BD. Lipoxin A4 regulates natural killer cell and type 2 innate lymphoid cell activation in asthma. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:174ra126. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Xue L, Salimi M, Panse I, Mjosberg JM, McKenzie AN, Spits H, Klenerman P, Ogg G. Prostaglandin D2 activates group 2 innate lymphoid cells through chemoattractant receptor-homologous molecule expressed on TH2 cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1184–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.10.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Maazi H, Patel N, Sankaranarayanan I, Suzuki Y, Rigas D, Soroosh P, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH, Akbari O. ICOS:ICOS-ligand interaction is required for type 2 innate lymphoid cell function, homeostasis, and induction of airway hyperreactivity. Immunity. 2015;42:538–551. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Paclik D, Stehle C, Lahmann A, Hutloff A, Romagnani C. ICOS regulates the pool of group 2 innate lymphoid cells under homeostatic and inflammatory conditions in mice. Eur J Immunol. 2015;45:2766–2772. doi: 10.1002/eji.201545635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]