Abstract

Sarcomere length dependent activation (LDA) of myocardial force development is the cellular basis underlying the Frank-Starling law of the heart, but it is still elusive how the sarcomeres detect the length changes and convert them into altered activation of thin filament. In this study we investigated how the C-domain of cardiac troponin I (cTnI) functionally and structurally responds to the comprehensive effects of the Ca2+, crossbridge, and sarcomere length of chemically skinned myocardial preparations. Using our in situ technique which allows for simultaneous measurements of time-resolved FRET and mechanical force of the skinned myocardial preparations, we measured changes in the FRET distance between cTnI(167C) and cTnC(89C), labeled with FRET donor and acceptor, respectively, as a function of [Ca2+], crossbridge state and sarcomere length of the skinned muscle preparations. Our results show that [Ca2+], cross-bridge feedback and sarcomere length have different effects on the structural transition of the C-domain cTnI. In particular, the interplay between crossbridges and sarcomere length has significant impacts on the functional structural change of the C-domain of cTnI in the relaxed state. These novel observations suggest the importance of the C-domain of cTnI and the dynamic and complex interplay between various components of myofilament in the LDA mechanism.

INTRODUCTION

The Frank-Starling law of the heart describes the ability of the heart to adjust ventricular pressure and stroke volume in response to a change in diastolic ventricular filling (Lakatta 1987). An increase in ventricular filling stretches the myocardium, and increases the sarcomere length of the myofilament, which leads to increased Ca2+ response and contractile force of the left ventricle. This stretch associated myocardium regulation is known as length dependent activation (LDA). Extensive efforts have been made to elucidate the underlying molecular basis of LDA, but the mechanism that connects sarcomere length changes and myofilament regulation is still unknown (Huxley 1973, de Tombe, Mateja et al. 2010, Li, Rieck et al. 2014). Early studies using dextran have shown that osmotic pressure decreases inter-filament spacing and increases Ca2+ sensitivity of chemically skinned cardiac muscle at short sarcomere length (McDonald and Moss 1995, Fuchs and Wang 1996, Farman, Walker et al. 2006). In a following study by Cazorla, the inter-filament spacing was found to be related to the magnitude of the titin based passive tension; whereas Ca2+ sensitivity was found to be correlated to titin based passive tension rather than sarcomere length (Cazorla, Wu et al. 2001). Recently, small-angle X-ray diffraction was implemented to show changes in sarcomere length may alter the crossbridge order and affect myofilament activation level (Farman, Gore et al. 2011). The results from the experiments described above suggest that the mechanism of LDA very likely involves a dynamic and complex interplay between different components of the myofilament, including inter-filament spacing, titin based passive tension, and crossbridges (de Tombe, Mateja et al. 2010, Campbell 2011), but it is unclear how sarcomere length dependent effects produced by these components are translated to enhanced Ca2+ sensitivity of thin filament regulation. One plausible mechanism for the signal translation is that the changes in the sarcomere length of myocardium may alter the conformation of troponin via crossbridge feedback, which is essential for cardiac myofilament regulation.

In an effort to understand the molecular mechanisms underlying LDA, we recently developed an in situ optical-mechanical approach to determine the influence of sarcomere length of myocardial preparations on Ca2+ mediated thin filament regulation and to examine the roles of crossbridges in the LDA process (Rieck, Li et al. 2013, Li, Rieck et al. 2014). It is known that Ca2+ binding to troponin C (cTnC) facilitates a series of conformational changes in thin filament proteins, including cardiac troponin I (cTnI), to activate myofilament regulation (Kobayashi, Kobayashi et al. 2000, Dong, Xing et al. 2001, Dong, Robinson et al. 2003). As the molecular basis of myofilament regulation, these Ca2+-induced structural changes are expected to be involved in LDA and sensitive to changes in sarcomere length and crossbridge states. Considering that cTnC is the myofilament Ca2+ sensor and sarcomere length-induced enhancement of myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity is a hallmark of LDA, in our previous study we implemented in situ time-resolved FRET in chemically-skinned muscle preparation study to simultaneously monitor the Ca2+-induced opening of the N-domain of cTnC and mechanical force development of the muscle preparations at various sarcomere lengths (Rieck, Li et al. 2013, Li, Rieck et al. 2014). We found that the Ca2+ induced opening of the N-domain of cTnC is sarcomere length dependent. Furthermore, the modulation of sarcomere length on myofilament activation is critically dependent on strongly bound crossbridge. These results provide a mechanistic link between sarcomere length and Ca2+ binding to cTnC via strong crossbridge binding, suggesting the sarcomere length-dependent crossbridge feedback may be a key determinant in length-dependent Ca2+ sensitivity that is associated with LDA

In this study, we aimed to investigate the impact of sarcomere length on the regulatory function of cTnI to understand the role of the C-domain of cTnI in the LDA process. The C-domain of cTnI is composed of the inhibitory region, switch region and mobile domain. Together with tropomyosin, the C-domain of cTnI regulates the “on” and “off” of actomyosin interaction through steric blocking of myosin-binding sites on actin (Haselgrove 1972, Huxley 1973, Parry and Squire 1973). Therefore, evidence connecting sarcomere length to the regulatory role of the C-domain of cTnI would provide insight into how upstream sarcomere length changes are transduced to the Ca2+-troponin through the C-domain of cTnI. To achieve the goal, in situ time-resolved FRET measurements were performed on fluorophore-labeled cTnI(167C)AEDANS (FRET donor) and cTnC(89C)DDPM (FRET acceptor) incorporated into skinned myocardial preparations to determine the effects of sarcomere length changes on the interaction between cTnC and the C-domain of cTnI. By simultaneous measurements of mechanical force developments of the myocardial preparation and time-resolved FRET between AEDANS and DDPM, we were able to determine AEDANS-DDPM distance distributions as a function of cross-bridge states, and sarcomere length. Our results indicate that the Ca2+-induced movement of cTnI is sarcomere length dependent and the length dependent change in the C-domain of cTnI is more significant at relaxed state and under normal crossbridge cycling condition. This suggests that the interplay between sarcomere length and crossbridge feedback, involving the C-domain of cTnI, may be critical for thin filament regulation in the diastole of the heart.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal Handling Protocols

The handling of all the experimental animals followed the institutional guidelines and protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee and the Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare, National Institutes of Health. Our muscle preparation study also followed the established guidelines of and was approved by the Washington State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Preparation of Proteins

The recombinant single-cysteine mutant cTnC(S89C) and cTnI(S167C) from rat cDNA clones were subcloned into a pET-3d vector, which were then transformed into BL21(DE3) cells (Invitrogen) and expressed under isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside induction. The expressed proteins were purified as previously described (Dong, Xing et al. 1999, Dong, Xing et al. 2001, Robinson, Dong et al. 2004). A protocol established previously (Robinson, Dong et al. 2004) was used to modify the single-cysteine cTnI with 5-((((2-iodoacetyle)amino)ethyl)amino)naphthalene-1-sulfonic acid (AEDANS) as FRET donor and modify cTnC(S89C) with N-(4-dimethylamino- 3,5-dinitrophenyl)maleimide (DDPM) as FRET acceptor. The labeling ratio was determined spectroscopically using ε325 = 6000 cm−1 M−1 for AEDANS and ε442 = 2930 cm−1 M−1 for DDPM. Labeling ratios for all protein modification were >95%.

Preparation of pCa Solutions

The pCa (−log of free Ca2+ concentration) solutions were prepared based on calculations of the program by Fabiato (Fabiato and Fabiato 1979). The 20 mM EGTA relaxing solution contained (in mM) 50 BES, 30.83 K-Propionate, 10 NaN3, 20 EGTA, 6.29 MgCl2, and 6.09 Na2ATP. The activating solution (pCa 4.3) contained (in mM) 50 BES, 5 NaN3, 10 EGTA, 10.11 CaCl2, 6.61 MgCl2, 5.95 Na2ATP and 51 K-propionate. Similarly, the relaxing solution (pCa 9.0) was composed of (in mM) 50 BES, 5 NaN3, 10 EGTA, 0.024 CaCl2, 6.87 MgCl2, 5.83 Na2ATP and 71.14 K-propionate. For crossbridge inhibition, 1 mM sodium Vi was added to the above pCa solutions. For promotion of ADP-mediated non-cycling, strong-binding cross-bridge interactions, ATP in the relaxing and activating solutions was replaced with 5 mM Mg2+-ADP. The ionic strength of all pCa solutions was 180 mM. In addition, protease inhibitors including 5 μM bestatin, 2 μM E-64, 10 μM leupeptin, and 1 μM pepstatin were also added to these solutions (Chandra, Tschirgi et al. 2007).

Preparation of Detergent-Skinned Cardiac Muscle Preparations

Left ventricular papillary bundles were prepared from adult (6–8 months in age) Sprague Dawley rats using previously established protocol (Terui, Shimamoto et al. 2010, Rieck, Li et al. 2013, Li, Rieck et al. 2014). Animals were deeply anesthetized by inhalation of 3% isoflurane and hearts were quickly excised and placed into ice-cold 20 mM EGTA relaxing solution in the presence of 1.0 mM DTT, and 20 mM 2, 3-butanedione monoxime. Fresh protease inhibitors including 4 μM benzamidine-HCl, 5 μM bestatin, 2 μM E-64, 10 μM leupeptin, 1 μM pepstatin and 200 μM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride were added to the solution. Papillary muscle bundles were carefully removed from the left ventricles of rat hearts. Muscle preparations (~150–200 μm in diameter and 2.0 mm in length) were dissected and skinned overnight at 4 °C using 1% triton X-100 in 20 mM EGTA relaxing solution.

Incorporation of Fluorescently Labeled cTnI(167C) and cTnC(89C) Constructs into Detergent Skinned Myocardial Preparations

Troponin (cTn) complex containing cTnC(89C)DDPM, cTnI(167C)AEDANS and wild-type cTnT was reconstituted at a molar ratio of 1:1:1 cTnC:cTnI:cTnT using protocol modified from previous study (Sumandea, Vahebi et al. 2009). For the donor-acceptor samples, endogenous troponin in the detergent skinned rat cardiac muscle preparations were exchanged by overnight incubation in exchange solution containing the reconstituted cTn complex. To ensure efficient exchange with fluorescence acceptor, cTnC(89C)DDPM, muscle preparations were subjected to an additional overnight incubation in exchange solution containing cTnC(89C)DDPM (1.5 mg mL−1). To measure donor-only samples the same exchange procedure was followed, but the cTnC(89C)DDPM in the reconstituted cTn was replaced by wild-type cTnC. The exchange solution contained (in mM): 50 BES, 30.83 K-propionate, 10 NaN3, 20 EGTA, 6.29 MgCl2, 6.09 Na2ATP, BDM, 1 DTT, 0.005 bestatin, 0.002 E-64, 0.01 leupeptin, and 0.001 pepstatin.

Western Blotting Analysis of Reconstitution Levels of Modified cTnI in Cardiac Muscle

To assess the efficiency of the protein exchange using our protocol, detergent-skinned myocardial preparations were reconstituted with cTn complex containing c-myc tagged cTnI. The reconstituted muscle preparations were incubated in 10 μL of a protein extraction buffer per 1 muscle preparation on ice for 1 hr. Skinned muscle preparations that had not undergone exchange were similarly incubated to create a negative control. The protein extraction buffer contained 2.5% SDS, 10% glycerol, 50 mM Tris base (pH 6.8 at 4 °C), 1 mM DTT, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 4 mM benzamidine HCl, 5 μM bestatin, 2 μM E-64, 10 μM leupeptin, and 1 μM pepstatin. After incubation, samples were sonicated for 20 min in a water bath at 4 °C and centrifuged at 10k rpm. Equal amounts of supernatants fractions were loaded to 4 – 20% SDS–PAGE gels for Western blotting analysis following the protocol established previously (Rieck, Li et al. 2013, Li, Rieck et al. 2014). Loading amounts were standardized by estimating the total protein concentration using a Protein Assay Kit (Biorad #5000121). The incorporation of c-myc cTnI was evaluated using a primary antibody against cTnI (Abcam #58544) followed by horseradish peroxidase conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (GE healthcare RPN 2108).

Simultaneous Measurement of Isometric Force and Time-Resolved Fluorescence Intensity in Detergent-Skinned Cardiac Muscle Preparations

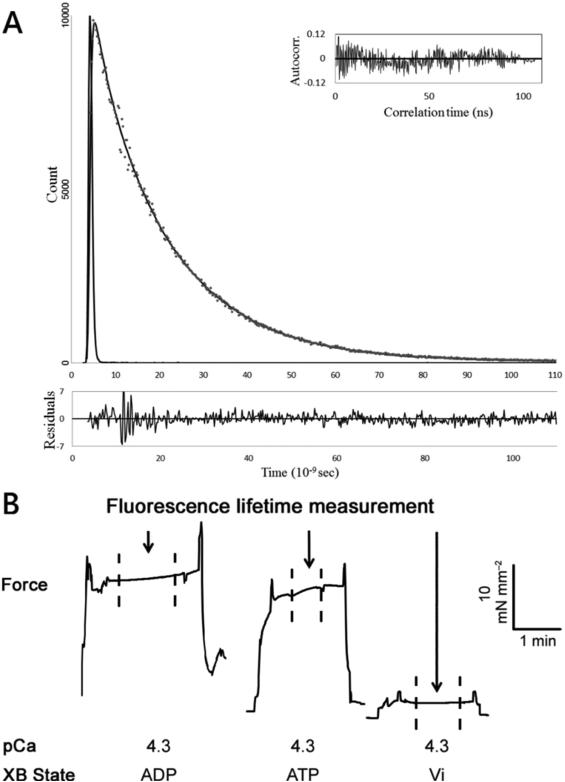

Following a protocol previously established in our lab (Rieck, Li et al. 2013, Li, Rieck et al. 2014), Güth MRS OPT modified with a TBX picosecond photon detection module (HORIBA Jobin Yvon) was used in this study to simultaneously make biomechanical and optical measurements. Briefly, after mounting the skinned muscle preparations onto the force transducer and a stationary tweezer, isometric force measurements were conducted using a force transducer (SI Heidelberg KG7A) capable of measuring 5 mN with a resonance frequency of 500 Hz. The sarcomere length of the muscle preparation was adjusted to either 1.8 or 2.2 μm using He-Ne laser diffraction measurements. The experimental temperature of the pCa solution was controlled at 20 ± 0.2 °C using a bipolar temperature controller (Cell MicroControls TC2BIP) coupled with a cooling/heating module (Cell MicroControls CH). FRET decays of the skinned muscle preparations containing fluorescently modified troponin were acquired with excitation 340nm from a NanoLED (HORIBA Jobin Yvon N-340) with a <1.2 ns pulse width and a 500nm cutoff filter. Time-resolved measurements were made when force reached steady state to ensure the elimination of uncontrolled factors that can affect protein conformation during the rising phase of force development. The fluorescence intensity decays were processed and recorded by a FluoroHub-B (HORIBA Jobin Yvon). Typically, a total of 10,000 photon counts at peak channel for each decay collection was collected in 1–1.5 min. Figure 1 demonstrates a typical fluorescence intensity decay (A) with residue and auto-correlation analysis, and contractile force (B) measured at 1.8 μm sarcomere length. The distance at the peak of the distribution was taken as the mean distance (r) between donor and acceptor sites within the cTnI and cTnC population being observed. The spread of the distance distribution is described by a full width at half maximum (FWHM). For each measurement, sarcomere length was adjusted to either 1.8 or 2.2 μm using laser diffraction and subjected to an initial cycle of activation and relaxation, after which the sarcomere length was readjusted if necessary. Half of our measurements were started at 1.8 μm sarcomere length, whereas the other half was started at 2.2 μm sarcomere length. Isometric force and fluorescence intensity decay were then synchronously, digitally recorded as the muscle preparation was subjected to pCa 4.3 solution at the chosen sarcomere length. These measurements were performed repeatedly in the presence of cycling cross-bridges (5 mM Mg-ATP); Mg2+-ADP-induced non-cycling, strong-binding cross-bridges (5 mM Mg-ADP + 0 mM ATP); and vanadate-induced non-cycling, weak-binding cross-bridges (1 mM Vi + 5 mM Mg-ATP).

Figure 1.

Simultaneous measurements of isometric force and time-resolved fluorescence intensity decay were performed in detergent-skinned cardiac muscle preparations reconstituted with fluorescence donor, cTnI(167C)AEDANS, and nonfluroescent acceptor, cTnC(89C)DDPM. (A) (Upper panel) Representative trace of the In Situ total fluorescence intensity decay of FRET donor in the presence of nonfluorescent acceptor DDPM (grey dots), which was measured at 1.8 μm sarcomere length in the presence of Ca2+ (pCa 4.3). The decay data was fitted with Eq. 1 (black line). The autocorrect (inset) and residual (lower panel) were used to judge the goodness of fit. (B) Fluorescence intensity decays were measured when force had reached steady state as indicated by the arrows and dash lines. Different crossbridge (XB) states are also indicated. The magnitudes of force and time are indicated by the horizontal and vertical bars.

Determination of Inter-Probe Distance Distributions from Measured Fluorescence Intensity Decays

The AEDANS-DDPM inter-probe distance distribution associated with a specific test condition was determined as follows. The AEDANS excited-state decays observed for the donor-only samples were fitted with a multi-exponential function (Liao, Wang et al. 1992):

| (1) |

where the αi represents the fractional amplitude associated with each correlation time τi contributing that contributes to the overall excited-state decay process. In the presence of the non-fluorescent acceptor DDPM, the AEDANS excited-state decays observed for donor–acceptor samples were fit to the following equation using DecayFit 1.4 (Fluorescence Decay Analysis Software, FluorTools):

| (2) |

where r is the distance between the donor and acceptor fluorophores; αDi and τDi are the fractional amplitude and correlation time parameters, respectively, determined for AEDANS in the absence of DDPM; and Ro is the Förster critical distance at which energy transfer is 50% efficient. P(r) is the probability distribution of inter-probe distances, and in this study we assume it to be a single Gaussian as follows:

| (3) |

where r is the mean distance and σ is the standard deviation of the distribution. P(r) is normalized by area, and Z is the normalization factor. The full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the distribution is given by FWHM ≈ 2.3548σ. In practice, the integration limits in Eq. 3 are not from 0 to ∞, and the integral is instead calculated over a range of distances from rmin to rmax with the lower limit being about 5 Å.

The Förster distance Ro in Eq. 2 was calculated from the spectral properties of AEDANS and DDPM:

| (4) |

where n is the refractive index of the solution and was taken as 1.4, Q is the donor quantum yield, κ2 is the orientation factor, and J is the spectral overlap integral that is given by

| (5) |

where FD(λ) is the fluorescence intensity of the donor at wavelength λ and εA(λ) is the molar absorptivity of the acceptor at λ. J was calculated by numerical integration. Dynamic averaging and the associated value of ⅔ for κ2 were assumed.

Statistical Data Analysis

Contractile and conformational parameters were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA. The factors in the analysis include 1) sarcomere length (1.8μm or 2.2μm), and 2) crossbridge states (weakly bound, cycling, or strongly bound crossbridge state). Post-hoc tests (planned multiple pairwise comparisons) were made using uncorrected Fisher's LSD method after the analyses of two-way ANOVA. Comparisons were made to determine the effects of sarcomere length and crossbridges on contractile and conformational parameters. Fitted values of r and FWHM values are reported as mean ± SEM with statistical significance level set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

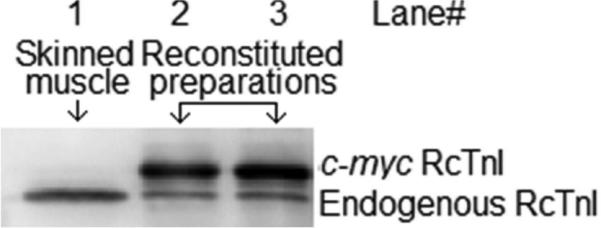

Western Blot Analysis of the Reconstituted Cardiac Muscle Preparations

The c-myc-tagged cTnI(wt) was used as a control for assessing our reconstitution scheme. To determine the effects of sarcomere length on the conformational transition of the C-domain of cTnI, the troponin complex consisting of cTnI(167c)AEDANS, cTnC(89c)DDPM, and cTnT(wt) was reconstituted into skinned cardiac muscle preparations. To ensure that the concentration of the fluorescence acceptor, cTnC(89c)DDPM, was higher than that of the fluorescence donor, cTnI(167c)AEDANS, in the reconstituted muscle preparations, the preparations were subjected to an additional overnight incubation of cTnC(89c)DDPM. To estimate the relative incorporation of fluorescently labeled troponin subunits in the samples, the c-myc cTnI reconstituted muscle preparations were digested in a protein extraction buffer (10% glycerol, 50mM Tris base, 2.5% SDS, 1mM DTT, 1mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 4mM benzamidine HCl, 5 μM bestatin, 2 μM E-64, 10 μM leupeptin, and 1 μM pepstatin, pH 6.8 at 4 °C) using a previously described protocol (Tsaturyan, Koubassova et al. 2005, Rieck, Li et al. 2013). Equal quantities of digested muscle preparation samples were separated on SDS-PAGE gels for Western blotting analysis (see Methods). The differences in migration speed between the c-myc-tagged cTnI(wt) and the endogenous cTnI enabled us to probe the level of incorporation of the c-myc-tagged protein. The relative incorporation of c-myc cTnI(wt) was >80% (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Western blot analysis of reconstituted cardiac muscle preparations. Anti cTnI antibody was used to access the level of incorporation of c-myc tagged Rat cTnI (RcTnI) in the reconstituted cardiac muscle preparations. Starting from the left, Lane 1, 2 and 3 shows skinned cardiac preparation, c-myc cTnI reconstituted cardiac muscle preparation, and preparations subjected to an additional overnight incubation of cTnC(89C)DDPM, respectively. Image J software was used to for densitometric analysis of band intensities and the relative amount of incorporated c-myc cTnI(wt) was >80%.

Effects of Crossbridge States on Ca2+ Activated Maximum Force Production at Sarcomere Length of 1.8 and 2.2 μm

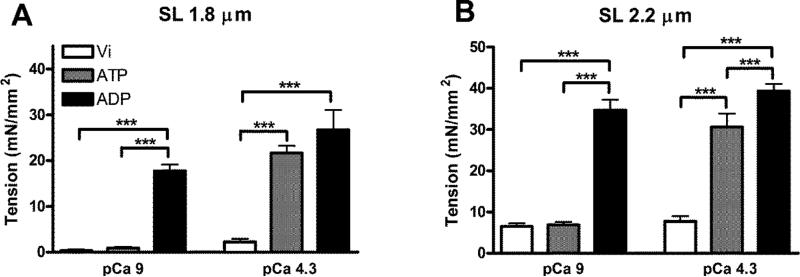

First, we examined the effects of crossbridge state on Ca2+ activated maximum force production (at pCa 4.3) at short (1.8 μm) and long sarcomere lengths (2.2 μm) (Fig. 3 and Table 1). Sarcomere lengths of 1.8 and 2.2 μm were chosen in this study because the range of 1.8-2.2 μm is a part of the ascending limb that close to optimal sarcomere length for cardiac function. A two-way ANOVA (See Statistical Data Analysis for details) showed no significant interaction effects, but revealed a significant main effect (p < 0.001) of sarcomere length on Ca2+ activated maximum force production. Post-hoc multiple comparisons showed that Vi significantly inhibited Ca2+ activated force production at both short (Fig. 3A) and long (Fig. 3B) sarcomere lengths. The maximum force production was significantly increased by ~28% at 2.2 μm in the presence of ADP (Fig. 3B), whereas the increase was not significant at 1.8 μm. On the other hand, when sarcomere length was reduced from 2.2 to 1.8 μm, the Ca2+ activated maximum force production was decreased by ~30% and ~32% under ATP and ADP conditions, respectively. To assess potential detrimental effects on the mechanical properties of skinned myocardial preparation by protein exchanges, passive tension and active force of skinned muscle preparations with and without troponin exchange were measured. Passive tension of skinned muscle preparations at sarcomere length of 1.8 and 2.2 μm are 0.34 ± 0.10 and 6.54 ± 0.40 mN/mm2, respectively; whereas active tension at sarcomere length of 1.8 and 2.2 μm are 22.21 ± 0.98 and 34.65 ± 1.51 mN/mm2, respectively. These numbers are close to the numbers listed in Table 1 obtained for skinned muscle preparations after reconstituted with extrinsic troponin. These results suggest that the length dependent changes in Ca2+-activated maximum force production are not affected by the states of crossbridges or by muscle preparation reconstitution with fluorophore-modified troponin proteins.

Figure 3.

Effects of crossbridge state on force production at 1.8 μm (A) and 2.2 μm (B) sarcomere length (SL). Ca2+ independent and activated force production were measured at both sarcomere lengths. Addition of Vi significantly inhibited Ca2+ activated force production, while ADP significantly increased force production at both sarcomere lengths even at pCa 9. Parameters values are reported as mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.05

Table 1.

Force values (mean ± SEM, n = 4-6) from FRET donor-acceptor reconstituted muscle preparations measured at pCa 9 and 4.3 as a function of crossbridge states and sarcomere lengths (SL).

| Cross-bridge state | Force (mN mm–2) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| pCa | 1.8 μm SL | 2.2 μm SL | |

| 1 mM Via | 9.0 | 0.31 ± 0.32 | 6.47 ± 0.74 |

| 4.3 | 2.25 ± 0.64 | 7.75 ± 1.27 | |

| 5 mM ATP | 9.0 | 0.89 ± 0.28 | 6.9 ± 0.70 |

| 4.3 | 21.67 ± 1.54β | 30.63 ± 3.25β | |

| 5 mM ADPb | 9.0 | 17.76 ± 1.37*,α | 34.70 ± 2.54*,α |

| 4.3 | 26.71 ± 4.36β | 39.34 ± 1.70β,† | |

Vi solutions also contained 5 mM ATP.

ATP was absent in ADP solutions.

Statistical significance level set at p < 0.05 for the following:

Control: Vi (pCa 9.0).

Control: ATP (pCa 9.0).

Control: Vi (pCa 4.3).

Control: ATP (pCa 4.3).

Effects of Crossbridge States on the Ca2+ Independent Tension at Low [Ca2+] at Sarcomere Lengths of 1.8 and 2.2 μm

We also examined the effects of crossbridge states on Ca2+ independent tension (at pCa 9) at short (1.8 μm) and long (2.2μm) sarcomere lengths (Table 1). A significant interaction effect (p < 0.005) was revealed by two-way ANOVA, suggesting a divergent impact of crossbridge states on how sarcomere length modulates Ca2+ independent tension development. Post-hoc tests using multiple comparisons were used to identify the main factor responsible for the significant interaction effect. Post-hoc tests demonstrated that in comparison with ATP, ADP had an impact on Ca2+ independent tension at both sarcomere lengths, while Vi did not have an effect (Fig. 3). On the other hand, a reduction in sarcomere length reduced Ca2+ independent tension under all crossbridge state conditions. Thus, sarcomere length dependent mediated effects on Ca2+ independent tension were retained within each crossbridge state group.

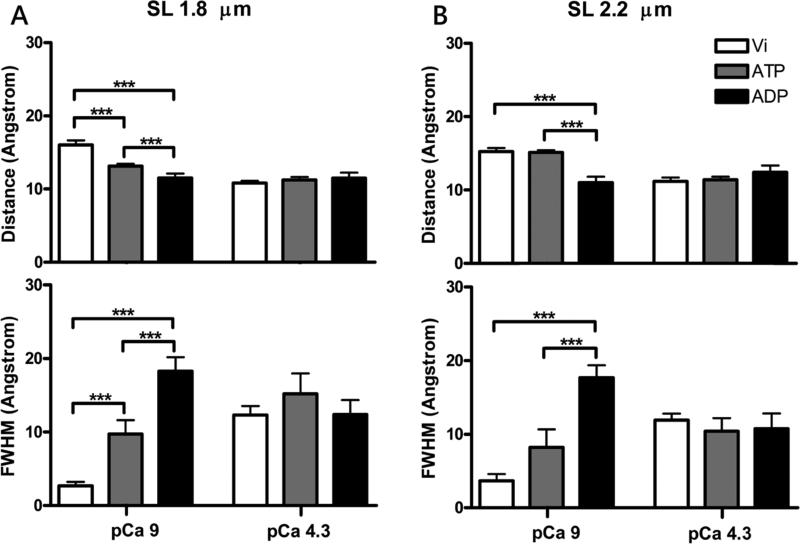

Effects of Crossbridge States on The Conformational Transition of the C-domain of Troponin I at Low [Ca2+] at Sarcomere Lengths of 1.8 and 2.2 μm

Conformational change in the C-domain of cTnI in skinned myocardial preparations the relaxed state in response to tension development was examined by monitoring changes in FRET distance between cTnI(167C)AEDANS and cTnC(89C)DDPM in different crossbridge states. The mean distances (r) and FWHM recovered from analysis of intensity decay measurements are summarized in Table 2. Two-way ANOVA showed a significant interaction effect (p < 0.05), which suggests that the interplay between crossbridge state and sarcomere length modulates the conformational transition of the C-domain of cTnI at low [Ca2+]. Post-hoc multiple comparisons revealed that crossbridges have divergent impacts on the conformation of the C-domain of cTnI sarcomere lengths of 1.8 and 2.2 μm. When the measurements were performed sarcomere length of 1.8 μm under ATP condition, the mean distance, r, between cTnI and cTnC was ~3 Å closer (p < 0.005) than the distance measured under the Vi condition (Fig. 4A), but no significant change in the mean distance was observed when the measurements were performed at sarcomere length of 2.2 μm (Fig. 4B). When measurements were performed in the presence of ADP rather than ATP, the mean distance was further decreased at both sarcomere lengths. Furthermore, multiple comparison analysis revealed that under ATP condition the mean distance obtained at sarcomere length of 1.8 μm was significantly closer (p < 0.05) than that obtained at sarcomere length of 2.2 μm (Fig. 4A). Thus, these observations suggest that crossbridge cycling (ATP state), strongly bound crossbridges (ADP state), and sarcomere length affect the conformation of the C-domain of cTnI.

Table 2.

Distance distributions observed in cTnI(167C)AEDANS and cTnC(89C)DDPM reconstituted muscle preparations under different biochemical conditions. Absolute parameter values are given as mean ± SEM, n = 4-6.

| Cross-bridge state |

r

a (Å) |

FWHM b (Å) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pCa | 1.8 μm SL | 2.2 μm SL | 1.8 μm SL | 2.2 μm SL | |

| 1 mM Vic | 9.0 | 16.04 ± 0.62 | 15.26 ± 0.49 | 2.68 ± 0.57 | 3.68 ± 0.92 |

| 4.3 | 10.82 ± 0.28 | 11.17 ± 0.52 | 12.30 ± 1.22 | 11.92 ± 0.87 | |

| 5 mM ATP | 9.0 | 13.15 ± 0.29* | 15.15 ± 0.28 | 9.74 ± 1.86* | 8.24 ± 2.41 |

| 4.3 | 11.23 ± 0.41 | 11.39 ± 0.43 | 15.22 ± 2.78 | 10.42 ± 1.76 | |

| 5 mM ADPd | 9.0 | 11.51 ± 0.61*,α | 11.00 ± 0.81β,† | 18.30 ± 1.88*,α | 17.69 ± 1.69β,† |

| 4.3 | 11.48 ± 0.76 | 12.42 ± 0.91 | 12.39 ± 1.95 | 10.76 ± 2.05 | |

r is the mean distance associated with the distribution.

FWHM denotes the full width at half maximum.

Vi solutions also contained 5 mM ATP.

ATP was absent in ADP solutions.

Statistical significance level set at p < 0.05 for the following:

Control: Vi at 1.8 μm (pCa 9.0).

Control: ATP at 1.8 μm (pCa 9.0).

Control: Vi at 2.2 μm (pCa 9.0).

Control: ATP at 2.2 μm (pCa 9.0).

Figure 4.

Distance and FWHM recovered from cTnI(167C)AEDANS and cTnC(89C)DDPM reconstituted muscle preparations at pCa 9 and pCa 4.3. Effects of crossbridge binding state on the conformational transition of the C-cTnI switch region at short 1.8 μm (A) and long 2.2 μm (B) SL. Upper panels show the distance between cTnI(167C)AEDANS and cTnC(89C)DDPM under different crossbridge states and [Ca2+], while the lower panels show the FWHM of the corresponding distance. Parameters values are reported as mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.05.

FWHM describes the breadth of the range of distances between cTnI(167C)AEDANS and cTnC(89C)DDPM; it is therefore closely correlated with the dynamic information associated with the structure monitored by FRET. A large FWHM derived from FRET decays suggests a dynamic/flexible structure, whereas a small FWHM suggests a relatively rigid structure. Two-way ANOVA showed no significant interaction effects, but revealed a significant main effect (p < 0.0001) of crossbridge states on the FWHM of FRET distance distributions between cTnC and cTnI. When measurements were performed at sarcomere length of 1.8 μm, post-hoc multiple comparisons showed that FWHM was significantly increased from the force inhibition (Vi) state to the crossbridge cycling (ATP) state (p < 0.05) and the strong crossbridge (ADP) state (p < 0.005) (Fig. 4A). The small FWHM value in the Vi state suggests that the structure monitored by FRET between cTnI(167C)AEDANS and cTnC(89C)DDPM is relatively rigid and less dynamic. This implies that the inhibition of strongly bound crossbridge by Vi allows the C-domain of cTnI to interact strongly with the actin filament and therefore significantly reduces the structural dynamics of the C-domain of cTnI. On the other hand, the presence of MgADP promotes strong crossbridge formation, which shifts tropomyosin to a state that significantly weakens the interaction between the C-domain of cTnI and the actin filament (Xing, Chinnaraj et al. 2008). Thus, the weakened interaction may release the C-domain of cTnI from actin binding leading to increased structural dynamics. Collectively, the linear increase in the FWHM from Vi to ATP to ADP suggests that there exists a mixture of strongly bound crossbridges and weak interactions between the C-domain of cTnI and actin under ATP condition. A similar increase in FWHM was also seen for the longer (2.2 μm) sarcomere length (Fig. 4B), although the difference between the Vi and ATP conditions was not statistically significant. Taken together, our results suggest that the impact of crossbridge states on the structural dynamics of cTnI and cTnC is not affected by sarcomere length.

Effects of Crossbridge States on the Ca2+ Induced Conformational Transition of the C-Domain of Troponin I at Sarcomere Lengths of 1.8 and 2.2 μm

The mean FRET distances and FWHM of the distance distributions derived from measurements performed at pCa 4.3 for both short and long sarcomere lengths are shown in Figure 4 and Table 2. In contrast to the results obtained for the relaxed state, discussed above, when saturating Ca2+ was present two-way ANOVA showed no interaction effect. Post-hoc multiple comparisons showed no significant differences in either the mean FRET distances between cTnI(167C) and cTnC(89C) or the associated FWHM values obtained for the three different crossbridge states and two different sarcomere lengths. Residue 167 of cTnI modified with AEDANS as the FRET donor in our measurements is located at the C-terminal end of the switch region of cTnI. Therefore, the conformational change monitored by our FRET measurements primarily reflects the structural interaction between the N-domain of cTnC and the switch region of cTnI. It is known that the affinity of the N-domain of cTnC binding to the switch peptide of cTnI in the saturating Ca2+ state is significantly higher than that in the absence of Ca2+ state (Gomes, Potter et al. 2002). Because the Ca2+-induced strong interaction between the N-domain of cTnC and the switch region of cTnI in the activated muscle preparations brings the region of cTnI away from the actin filament, it is not surprising that the structural behaviors represented by our FRET mean distance and the associated FWHM results are insensitive to changes in crossbridge state and sarcomere length.

DISCUSSION

Length dependent activation plays important roles in cardiac muscle contraction and relaxation. It is very likely that the modulation role of sarcomere length in cardiac myofilament activation involves the binding of crossbridges to actin filament (Bordas, Svensson et al. 1999, Adhikari, Regnier et al. 2004, Smith, Tainter et al. 2009, Farman, Gore et al. 2011) and crossbridge feedback on Ca2+-induced thin filament regulation (Tsaturyan, Koubassova et al. 2005, Zhou, Li et al. 2012, Rieck, Li et al. 2013). In this study we continued our efforts to investigate how the Ca2+-activated troponin regulation is affected by the sarcomere length of skinned cardiac muscle preparations through crossbridge feedback. Using our in situ FRET technique specifically developed for studies of skinned cardiac muscle preparations (Rieck, Li et al. 2013, Li, Rieck et al. 2014), we examined the in situ structural change of the C-domain, specifically the switch region, of cTnI with variations in Ca2+, crossbridge state, and sarcomere length. As demonstrated in previous in vitro studies (Xing, Jayasundar et al. 2009), the structural change of the C-domain of cTnI within skinned cardiac muscle preparations was monitored by measuring the FRET distance between residue 167 of cTnI modified with AEDANS as the FRET donor and residue 89 of cTnC modified with DDPM as the FRET acceptor. This unique in situ FRET technique allows us to monitor the mechanical tension development of the skinned muscle preparations and structural changes of the C-domain of cTnI for various crossbridge conditions and sarcomere lengths simultaneously (Fig. 1).

In agreement with previous studies (Allen and Kurihara 1982, Smith, Tainter et al. 2009, Li, Rieck et al. 2014), our tension measurements with skinned cardiac muscle preparations reconstituted with FRET donor/acceptor modified troponins showed that the Ca2+ induced maximum tension in the presence of normal crossbridge cycling (ATP state) at longer sarcomere length was significantly higher than that at the shorter sarcomere length (Table 1). In the presence of ADP, cardiac tissue exhibits nearly maximum force even at very low [Ca2+] regardless of changes in sarcomere length (Fig. 3 and Table 1). It is known that nucleotide ADP binds strongly to myosin heads, causing a conformational change in the myosin heads. This conformational change strengthens the interaction between the myosin heads and actin (Nishikawa, Monroy et al. 2011), leading to maximum force of the cardiac tissue. On the other hand, when vanadate (Vi) is present, no contraction of the muscle preparations is observed regardless of the presence of Ca2+ or changes in sarcomere length as Vi inhibits strong interactions between myosin heads and actin (Martyn, Smith et al. 2007); and therefore, it restrains any Ca2+ induced contractile force generation.

Along with these force changes, conformational changes of the C-domain of cTnI monitored by FRET measurements were found to be sensitive not only to [Ca2+], but also to crossbridge states and sarcomere lengths (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). The conformational changes of the C-domain of cTnI in this study are characterized by 1) the mean FRET distance between cTnI(167C)AEDANS and cTnC(89C)DDPM, which describes structural movement involving the C-domain of cTnI, and 2) the FWHM associated with the FRET distance distribution under each condition, which describes the structural dynamics of the domain. The primary findings from our in situ FRET measurements include the following.

-

1)

As an activator of thin filament regulation, Ca2+ binding to troponin is major contributor to the observed conformational changes involving cTnI(167C)AEDANS-cTnC(89C)DDPM. Consistent with previous in vitro studies (Xing, Jayasundar et al. 2009), a change in the experimental condition from pCa 9.0 to pCa 4.3 significantly reduced the mean FRET distance between cTnC and cTnI (Table 2) as a consequence of Ca2+ induced interaction between the N-domain of cTnC and the switch region of cTnI (Dong, Robinson et al. 2003, Xing, Chinnaraj et al. 2008), which brings the C-domain of cTnI away from the actin filament and closer to cTnC. Along with the structural movement of the C-domain of cTnI, FWFMs are significantly increased (Fig. 4), suggesting that with movement away from the actin filament the C-domain of cTnI becomes more dynamic. However, significant alterations in conformational changes are only observed in the normal crossbridge cycling (ATP) state and the crossbridge inhibition (Vi) state. No significant Ca2+-induced change was observed when strongly bound crossbridges (ADP state) were present, as the presence of ADP detached the C-domain region of cTnI from the actin filament and shifted the conformation of the domain closer to its activated state (Table 1).

-

2)

The conformation of the C-domain of cTnI within skinned muscle preparations can be modulated by crossbridge, and the modulation is dependent on Ca2+ and sarcomere length (Fig 3. and Fig. 4). When muscle preparation is in a relaxed state (pCa 9), the inhibition of crossbridge formation by Vi and the induction of strongly bound crossbridges by ADP have opposite effects on the conformational changes of the C-domain of cTnI. The binding of Vi completely inhibits force development of the muscle preparations (Fig. 1) and removes the crossbridge effects on the Ca2+-induced thin filament regulation, which leads to a larger separation between cTnI(167C)AEDANS and cTnC(89C)DDPM with a narrower distance distribution (small FWHM). This structural change is correlated with strong binding of the C-domain of cTnI to the actin filament. In contrast, ADP binding leads to a Ca2+ independent maximum tension development of the muscle preparations (Fig. 1) and decreases the distance with increased FWHM. This structural change is consistent with ADP-induced activation of the thin filament, which promotes the interaction between cTnC and the C-domain of cTnI. In cycling crossbridge state (in the presence of ATP), it is likely that there is an equilibrium of two populations of strongly and weakly bound crossbridges. Our results suggest that the overall effects of these two populations of crossbridges on the conformational changes of the cTnI C-domain are dependent on sarcomere lengths (Fig. 4), suggesting that crossbridge feedback and sarcomere length may have to work together to modulate troponin regulation. However, these modulation effects of crossbridge state observed in the relaxed state are blunted when the skinned muscle preparations are activated by Ca2+ (Fig. 4). Modulation effects of crossbridges on the functional structural changes involving the switch region of cTnI are more significant in the relaxed state than in the activated state; therefore, they may play a role in myocardium relaxation.

-

3)

The Ca2+ induced conformational changes involving the switch region of cTnI are dependent on sarcomere length. It was interesting to note that under the normal cycling crossbridge (ATP) condition, the mean FRET distance between the donor and acceptor in the relaxed state was significantly longer at long sarcomere length than that observed at short sarcomere length (Table 2). As a consequence of this sarcomere length enhanced separation between cTnC and the switch region of cTnI, Ca2+-induced overall structural changes involving the cTnC-cTnI interaction was much larger at long sarcomere length comparing to that at short sarcomere length. For example, under ATP condition the mean distance difference between pCa 9 and pCa 4.3 at sarcomere length of 2.2 μm is 3.76 ± 0.51Å, which is significantly larger (p < 0.05) than 1.92 ± 0.50Å at 1.8 μm. These results imply that the functional role of the C-domain of cTnI in myofilament activation may depend on the sarcomere length. The changes in FWHM associated with the FRET distance changes also showed some extent of sarcomere length dependent, but the changes were not statistically significant. No significant changes were observed in other crossbridge states.

These results provide novel information on in situ conformational changes in the C-domain, specifically the switch region, of cTnI in response to Ca2+ activation, crossbridge feedback and sarcomere length modulation. It seems the switch region of cTnI is more structurally sensitive to crossbridge feedback and sarcomere length modulation in the relaxed state than in the activated state. Furthermore, the Ca2+-induced structural transition of the switch region of cTnI was found not to be sensitive to strong (ADP) crossbridge feedback. These observations are not consistent with our previous study of the in situ behaviors of the N-domain of cTnC, which showed significant effects of crossbridge state on the conformation of the N-domain of cTnC at both sarcomere lengths (Li, Rieck et al. 2014). More importantly, strongly bound (ADP) crossbridges play an important role in translating the modulation effects of sarcomere lengths to the N-domain of cTnC (Rieck, Li et al. 2013, Li, Rieck et al. 2014). However, in this study the critical role of strong crossbridges was not observed. The cause of the divergence of the observations between this study and those from the previous one is likely due to that the two studies monitored different structural transitions. In the previous study, the effects of crossbridge states and sarcomere lengths on thin filament regulation were monitored using the Ca2+ induced opening of the N-domain of cTnC as a structural probe. In the current study, the Ca2+ induced interaction between cTnC and the switch region of cTnI was used as a probe. The switch region is connected by the inhibitory region and the mobile domain of cTnI at its N- and C-terminal ends, respectively, and strongly interacts with the N-domain of cTnC upon Ca2+ binding. Thus, it was expected that the structural behaviors of the switch region monitored in this study would not only correlate with the Ca2+ induced conformational changes observed in our previous study, but also provide information on the interaction between the C-domain of cTnI and actin filament.

In our measurements, structural behavior of the switch region was examined by monitoring the FRET distance between cTnI(167C)AEDANS and cTnC(89C)DDPM. The residue 167 of cTnI is located in the junction region of the C-terminus of the switch region and the N-terminus of the mobile domain. It is likely that the unique location of residue 167 contributes to some unique structural behaviors revealed by our FRET measurement. For instance, in this study the sarcomere length dependent effects were observed only for relaxed muscle preparation measurements and were independent of strong crossbridges (Table 2), while in the previous study of the N-domain of cTnC (Li, Rieck et al. 2014), the length dependent effects were primarily observed at activated muscle preparations and required the presence of strong crossbridges. The observations in the current study may be consistent with the notation for the role of the mobile domain in thin filament regulation. It is known that the mobile domain is a second actin binding region of cTnI. Previous in vitro studies (Shoemaker, Portman et al. 2000, Hoffman, Blumenschein et al. 2006, Zhou, Li et al. 2012) suggested that the primary functional role of the mobile domain of cTnI in the thin filament regulation is to bind the actin filament in the relaxed state and strengthen the inhibition of myofilament activation. It is expected that at the relaxed state the interaction with actin will be sensitive to sarcomere length induced strong crossbridge interaction. When Ca2+ is present, the Ca2+ induced interaction between the switch region of cTnI and the N-domain of cTnC brings the mobile domain away from actin, which makes the structural behavior of the mobile domain less sensitive to the presence of strong crossbridge and sarcomere length changes.

In addition to the potential contribution of the structural behavior of the mobile domain discussed above, it is acknowledged that other mechanisms may lead to less effect of the strong crossbridge on the sarcomere length induced changes in the conformational behaviors of the switch region of cTnI. For example, a recent ventricular trabeculae study found that reconstitution of cTnC mutant with a high Ca2+ affinity is able to enhance the Ca2+ sensitivity of muscle preparations at short sarcomere length to match with that of long sarcomere length and this effect is independent of crossbridges (Feest, Steven Korte et al. 2014). This study indicates that changes in sarcomere length may be directly related to an alteration of Ca2+ affinity of cTnC and Ca2+-induced structural changes of troponin. Another study using polarized fluorescence has revealed some novel structural transitions of cTnC that have not been seen in vitro (Linari, Brunello et al. 2015). The study demonstrated that at low [Ca2+] the N-domain of cTnC is very dynamic as if it was actively seeking cTnI, while in the Ca2+ activated state the N-domain of cTnC, along with the C-domain of cTnI, bends over towards the C-domain of cTnC. Though the measurements were performed at the long sarcomere length only, the results indicate that the C-domain, including the switch region and mobile domain, of cTnI may experience constant dynamic changes and may be sensitive to the effects of crossbridges at relaxed state. Once muscle preparations are activated, the mobile domain together with the C-terminal end of the switch region dissociate from actin filament and are therefore less sensitive to the crossbridges. These results suggest that different regions of the C-domain of cTnI may play different roles in myofilament regulation and have different unique responses to crossbridges and sarcomere lengths during muscle regulation.

Another interesting observation in this study is that the presence of the crossbridge inhibitor (Vi) significantly reduced structural dynamics of the switching region of cTnI, reflected by decreases in FWHM comparing to ATP and ADP groups when skinned muscle preparations was at relaxed state (Table 2 and Fig. 4). In the absence of Ca2+, strong interaction between the mobile domain and actin can significantly restrain structural dynamics of the switching region. Comparing the structural dynamics of cTnI in the presence of weakly bound crossbridges (Vi) to that of the normal cycling crossbridge (ATP), weakly bound crossbridges appeared to stabilize the interaction between cTnI and actin. This is because that Vi locked myosin heads in a weak crossbridge state, which allows all mobile domains of cTnI to strongly bind to the actin filament thereby restraining the dynamics of the C-terminus of the switching region of cTnI. On the other hand, strongly bound crossbridges (ADP) appeared to have a destabilizing effect on the interactions between cTnI and actin, because strongly bound crossbridges dissociate the mobile domain from actin binding. The dissociation of the mobile domain from actin leads to an increase in structural dynamics of the C-terminus of the switching region, where residue 167 is located. When skinned myocardial preparations are at ATP state in the absence of Ca2+, our ensemble FRET measurements show an intermediate dynamics of the C-terminus of the switching region of cTnI as if the structural dynamics under the ATP condition is a combination of the structural dynamics observed under Vi and ADP conditions. However, crossbridges are not expected to strongly bind to actin in the absence of Ca2+ and ADP. Our results suggest that the intermediate state between weakly and strongly bound crossbridges may play a role in thin filament regulation through modulating the structural dynamics. Lastly, since sarcomere length dependent effect on the structural behavior of the switching region of cTnI is completely blunted in the presence of Vi (Table 2), reduced structural dynamics are observed at both sarcomere lengths.

Caution should be taken in interpreting physiological significance of our findings considering the sarcomere lengths selected for our measurements. The ascending limb of the length-tension relationship is steep at the range of 1.8 μm to 2.0 μm, and the tension developed is optimal at sarcomere lengths of 2.0 μm to 2.2 μm (Gordon, Huxley et al. 1966, Shiels and White 2008). Hence, force development and protein conformational changes may be more prominent from 1.8 μm to 2.0 μm, but changes in 2.0 μm to 2.2 μm may be relatively small. Similar behavior have been noted in skeletal muscle that the distribution of myosin binding protein C and its ability to bind to actin changes at long sarcomere length range but not the short ones (Reconditi, Brunello et al. 2014). Since the sarcomere lengths (1.8 μm and 2.2 μm) selected in this study are at the extremities of the length tension relationship, our results do not represent the non-linear transition from 1.8 μm to 2.2 μm. Considering that the physiological operating range of sarcomere length may be between 1.96 μm and 2.16 μm (Chung and Granzier 2011), the findings presented in this study only reflect force and conformational changes at the chosen sarcomere lengths, and may not represent changes under physiological condition. Limitation of this study also includes that both force and fluorescence measurements were conducted under steady state condition. The findings in this study with skinned myocardial preparations only reflect steady-state condition, where the heart is never in steady state. The objective of this study is to understand the role of troponin in LDA and how the structural change in troponin in response to Ca2+ activation is affected by a change in sarcomere length. Information on the steady-state structural changes may provide a base for us to understand the molecular dynamics in the heart. Although our data were collected at steady state and only showed structural effects at two end states of the dynamic range of the heart, the presented results showed changes in structural effects from one state to another one and shine lights on how SL-based effects is transduced to troponin regulation. Finally, this study was performed with chemically skinned myocardial preparations, which allows rapidly exchanging activation solutions and manipulating muscle contraction and relaxation. However, one of the limitations of using skinned muscle preparations is that the effects of kinases on myofilament proteins are compromised. It has been shown previously that in intact muscle stretching muscle length alters the post-translational modifications of myofilament proteins (Ait mou, Guennec et al. 2008, Monasky, Biesiadecki et al. 2010, Yar, Monasky et al. 2014), which does not occur in our skinned muscle preparations. Multiple myofilament proteins, including cTnI, cTnT, Tm, myosin light chain-2, myosin binding protein C and titin, have been identified as phosphorylation targets in the myocardium (Solaro and Kobayashi 2011), but it is still unclear which kinases and phosphorylation sites are regulated under stretched conditions. Furthermore, phosphorylation of cTnI at Ser23/Ser24, Ser43/Ser44, or Thr144 are known to have divergent effects on maximum tension and crossbridge kinetics (Solaro, Henze et al. 2013). Because of the compounding effects of phosphorylation of myofilament proteins, it is difficult to speculate the possible impact of these post-transitional modifications on our results. Further studies in the presence of different phosphorylated myofilament proteins are needed in the future to acquire such information.

In summary, this in situ study provides evidence that the conformation of the C-domain, specifically the switch region, of cTnI with respect to cTnC is sensitive to Ca2+, crossbridges and changes in sarcomere length. The results show that changes in sarcomere length have significant effects on the conformation of the switch region of cTnI, but only under the relaxed condition and in the normal crossbridge cycling state. These observations imply interplay between sarcomere length and crossbridge in myofilament regulation at low Ca2+. It is noted that results from this study reflect only steady-state situations, but the heart never functions in steady state. To fully understand the role of the C-domain of cTnI in the LDA process, additional works are needed in the future to examine dynamic information associated with the these structural changes, as well as the role of other regions, especially the inhibitory region, of cTnI in translating the effects of sarcomere length to troponin regulation via crossbridge feedback.

The conformational change of C-domain of cTnI is Ca2+ and crossbridge states dependent.

The C-domain of cTnI is sensitive to sarcomere length and crossbridge states changes only in relaxed muscle.

The dynamic behavior of C-domain of cTnI is closely related to changes in the binding states of crossbridges on the actin filament.

Changes in the structural dynamics of C-domain of cTnI reflect its functional importance in the thin filament regulation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work is supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 4 HL80186-5S1 (to W.-J.D.), PO1 HL 062426 (to R.J.S.), and R21 HL109693 (to W.-J.D.) and also the M. J. Murdock Charitable Trust (to W.-J.D.).

ABBREVIATIONS

- Tn

troponin

- TnC

troponin C

- TnI

troponin I

- TnT

troponin T

- c

cardiac muscle

- FRET

Förster resonance energy transfer

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- EGTA

ethelene glycol-bis-(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N’,N’-tetraacetic acid

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- BDM

2, 3-butanedione monoxime

- IAEDANS

5-(io-doacetamidoethyl)aminonaphthelene-1-sulfonic acid

- DDPM

N-(4-dimethylamino-3,5-dinitrophenyl)maleimide

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adhikari BB, Regnier M, Rivera AJ, Kreutziger KL, Martyn DA. Cardiac Length Dependence of Force and Force Redevelopment Kinetics with Altered Cross-Bridge Cycling. Biophysical Journal. 2004;87(3):1784–1794. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.039131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ait mou Y, Guennec J-Y, Mosca E, Tombe PP, Cazorla O. Differential contribution of cardiac sarcomeric proteins in the myofibrillar force response to stretch. Pflügers Archiv - European Journal of Physiology. 2008;457(1):25–36. doi: 10.1007/s00424-008-0501-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen DG, Kurihara S. The effects of muscle length on intracellular calcium transients in mammalian cardiac muscle. J. Physiol. 1982;327:79–94. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordas J, Svensson A, Rothery M, Lowy J, Diakun GP, Boesecke P. Extensibility and Symmetry of Actin Filaments in Contracting Muscles. Biophysical Journal. 1999;77(6):3197–3207. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77150-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell KS. Impact of myocyte strain on cardiac myofilament activation. Pflugers Arch. 2011;462(1):3–14. doi: 10.1007/s00424-011-0952-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazorla O, Wu Y, Irving TC, Granzier H. Titin-based modulation of calcium sensitivity of active tension in mouse skinned cardiac myocytes. Circ. Res. 2001;88(10):1028–1035. doi: 10.1161/hh1001.090876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra M, Tschirgi ML, Ford SJ, Slinker BK, Campbell KB. Interaction between myosin heavy chain and troponin isoforms modulate cardiac myofiber contractile dynamics. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293(4):R1595–1607. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00157.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung CS, Granzier HL. Contribution of titin and extracellular matrix to passive pressure and measurement of sarcomere length in the mouse left ventricle. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;50(4):731–739. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Tombe PP, Mateja RD, Tachampa K, Mou YA, Farman GP, Irving TC. Myofilament length dependent activation. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2010;48(5):851–858. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong W-J, Xing J, Robinson JM, Cheung HC. Ca2+ induces an extended conformation of the inhibitory region of troponin I in cardiac muscle troponin. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2001;314(1):51–61. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong WJ, Robinson JM, Stagg S, Xing J, Cheung HC. Ca2+-induced conformational transition in the inhibitory and regulatory regions of cardiac troponin I. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(10):8686–8692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212886200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong WJ, Xing J, Villain M, Hellinger M, Robinson JM, Chandra M, Solaro RJ, Umeda PK, Cheung HC. Conformation of the regulatory domain of cardiac muscle troponin C in its complex with cardiac troponin I. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274(44):31382–31390. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.44.31382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiato A, Fabiato F. Calculator programs for computing the composition of the solutions containing multiple metals and ligands used for experiments in skinned muscle cells. J. Physiol. (Paris) 1979;75(5):463–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farman GP, Gore D, Allen E, Schoenfelt K, Irving TC, de Tombe PP. Myosin head orientation: a structural determinant for the Frank-Starling relationship. Am. J. Physiol. - Heart C. 2011;300(6):H2155–H2160. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01221.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farman GP, Walker JS, de Tombe PP, Irving TC. Impact of osmotic compression on sarcomere structure and myofilament calcium sensitivity of isolated rat myocardium. Am. J. Physiol. - Heart C. 2006;291(4):H1847–H1855. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01237.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feest ER, Steven Korte F, Tu A.-y., Dai J, Razumova MV, Murry CE, Regnier M. Thin filament incorporation of an engineered cardiac troponin C variant (L48Q) enhances contractility in intact cardiomyocytes from healthy and infarcted hearts. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2014;72:219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs F, Wang Y-P. Sarcomere Length Versus Interfilament Spacing as Determinants of Cardiac Myofilament Ca2+Sensitivity and Ca2+Binding. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1996;28(7):1375–1383. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes AV, Potter JD, Szczesna-Cordary D. The role of troponins in muscle contraction. IUBMB Life. 2002;54(6):323–333. doi: 10.1080/15216540216037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon AM, Huxley AF, Julian FJ. The variation in isometric tension with sarcomere length in vertebrate muscle fibres. The Journal of physiology. 1966;184(1):170–192. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1966.sp007909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haselgrove JC. X-ray evidence for a conformational change in the actin-containing filaments of vertebrate striated muscle. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Qant. Biol. 1972;37:341–352. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman RM, Blumenschein TM, Sykes BD. An interplay between protein disorder and structure confers the Ca2+ regulation of striated muscle. J Mol Biol. 2006;361(4):625–633. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxley HE. Structural Changes in the Actin- and Myosin-eontaining Filaments during Contraction. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology. 1973;37:361–376. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T, Kobayashi M, Gryczynski Z, Lakowicz JR, Collins JH. Inhibitory region of troponin I: Ca2+-dependent structural and environmental changes in the troponin-tropomyosin complex and in reconstituted thin filaments. Biochemistry. 2000;39:86–91. doi: 10.1021/bi991903b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakatta EG. Starling's law of the heart is explained by an intimate interaction of muscle length and myofilament calcium activation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1987;10(5):1157–1164. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(87)80361-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li KL, Rieck D, Solaro RJ, Dong W. In situ time-resolved FRET reveals effects of sarcomere length on cardiac thin-filament activation. Biophysical journal. 2014;107(3):682–693. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao R, Wang CK, Cheung HC. Time-resolved tryptophan emission study of cardiac troponin I. Biophys J. 1992;63(4):986–995. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81685-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linari M, Brunello E, Reconditi M, Fusi L, Caremani M, Narayanan T, Piazzesi G, Lombardi V, Irving M. Force generation by skeletal muscle is controlled by mechanosensing in myosin filaments. Nature. 2015;528(7581):276–279. doi: 10.1038/nature15727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyn DA, Smith L, Kreutziger KL, Xu S, Yu LC, Regnier M. The effects of force inhibition by sodium vanadate on cross-bridge binding, force redevelopment, and Ca2+ activation in cardiac muscle. Biophys. J. 2007;92(12):4379–4390. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.096768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald KS, Moss RL. Osmotic compression of single cardiac myocytes eliminates the reduction in Ca2+ sensitivity of tension at short sarcomere length. Circ. Res. 1995;77(1):199–205. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.1.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monasky MM, Biesiadecki BJ, Janssen PM. Increased phosphorylation of tropomyosin, troponin I, and myosin light chain-2 after stretch in rabbit ventricular myocardium under physiological conditions. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2010;48(5):1023–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa KC, Monroy JA, Uyeno TE, Yeo SH, Pai DK, Lindstedt SL. Is titin a ‘winding filament’? A new twist on muscle contraction. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 2011 doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry DA, Squire JM. Structural role of tropomyosin in muscle regulation: analysis of the x-ray diffraction patterns from relaxed and contracting muscles. J. Mol. Biol. 1973;75(1):33–55. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(73)90527-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reconditi M, Brunello E, Fusi L, Linari M, Martinez MF, Lombardi V, Irving M, Piazzesi G. Sarcomere-length dependence of myosin filament structure in skeletal muscle fibres of the frog. J Physiol. 2014;592(Pt 5):1119–1137. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.267849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieck DC, Li KL, Ouyang Y, Solaro RJ, Dong WJ. Structural basis for the in situ Ca(2+) sensitization of cardiac troponin C by positive feedback from force-generating myosin cross-bridges. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics. 2013;537(2):198–209. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2013.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JM, Dong WJ, Xing J, Cheung HC. Switching of troponin I: Ca(2+) and myosin-induced activation of heart muscle. J Mol Biol. 2004;340(2):295–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiels HA, White E. The Frank-Starling mechanism in vertebrate cardiac myocytes. The Journal of experimental biology. 2008;211(Pt 13):2005–2013. doi: 10.1242/jeb.003145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker BA, Portman JJ, Wolynes PG. Speeding molecular recognition by using the folding funnel: the fly-casting mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(16):8868–8873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160259697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith L, Tainter C, Regnier M, Martyn DA. Cooperative cross-bridge activation of thin filaments contributes to the frank-starling mechanism in cardiac muscle. Biophys. J. 2009;96(9):3692–3702. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solaro RJ, Henze M, Kobayashi T. Integration of troponin I phosphorylation with cardiac regulatory networks. Circ Res. 2013;112(2):355–366. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.268672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solaro RJ, Kobayashi T. Protein phosphorylation and signal transduction in cardiac thin filaments. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(12):9935–9940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.197731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumandea MP, Vahebi S, Sumandea CA, Garcia-Cazarin ML, Staidle J, Homsher E. Impact of Cardiac Troponin T N-Terminal Deletion and Phosphorylation on Myofilament Function. Biochemistry. 2009;48(32):7722–7731. doi: 10.1021/bi900516n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terui T, Shimamoto Y, Yamane M, Kobirumaki F, Ohtsuki I, Ishiwata S, Kurihara S, Fukuda N. Regulatory mechanism of length-dependent activation in skinned porcine ventricular muscle: role of thin filament cooperative activation in the Frank-Starling relation. J. Gen. Physiol. 2010;136(4):469–482. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201010502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsaturyan AK, Koubassova N, Ferenczi MA, Narayanan T, Roessle M, Bershitsky SY. Strong Binding of Myosin Heads Stretches and Twists the Actin Helix. Biophysical Journal. 2005;88(3):1902–1910. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.050047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing J, Chinnaraj M, Zhang Z, Cheung HC, Dong WJ. Structural studies of interactions between cardiac troponin I and actin in regulated thin filament using Forster resonance energy transfer. Biochemistry. 2008;47(50):13383–13393. doi: 10.1021/bi801492x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing J, Jayasundar JJ, Ouyang Y, Dong WJ. Forster resonance energy transfer structural kinetic studies of cardiac thin filament deactivation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(24):16432–16441. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808075200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yar S, Monasky MM, Solaro RJ. Maladaptive modifications in myofilament proteins and triggers in the progression to heart failure and sudden death. Pflugers Archiv : European journal of physiology. 2014;466(6):1189–1197. doi: 10.1007/s00424-014-1457-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Li K-L, Rieck D, Ouyang Y, Chandra M, Dong W-J. Structural dynamics of C-domain of cardiac troponin I protein in reconstituted thin filament. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287(10):7661–7674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.281600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]