Abstract

The scavenger receptor class B, type I (SR-BI), is a cell-surface glycoprotein that mediates selective uptake of high density lipoprotein (HDL)-derived cholesteryl ester. SR-BI plays an important role in cellular delivery of cholesterol. Both human and rodent SR-BI are expressed most abundantly in the liver parenchymal cells and steroidogenic cells of the adrenal gland and gonads, where the selective pathway exhibits its highest activity. In steroidogenic cells, the expression of SR-BI is regulated by trophic hormones (adrenocorticotropic hormone or gonadotropins luteinizing hormone or follicle-stimulating hormone) in concert with the regulation of steroid hormone production. DNA methylation has been implicated in a large number of biological processes mainly by regulating gene expression. The SR-BI promoter contains one CpG island (CGI) in its promoter and seven CGIs in its intronic regions. Here, we studied the DNA methylation status of SR-BI gene and provide evidence that the DNA methylation is cell specific in this gene promoter as well as in intronic regions. The DNA methylation in the SR-BI promoter is subject to N6, 2′-O-dibutyryladenosine3′:5′-cyclic monophosphate regulation in mouse adrenal Y1 cells and mouse Leydig tumor cells (MLTCs). The seven intron CGIs are methylated differentially in Y1 cells, MLTCs, ovarian granulosa cells, and mouse liver hepa 1–6 cells. Our experiments raised the possibility that DNA methylation participates in hormonal regulation of SR-BI expression in a tissue-specific manner. We further suggest that the cell-specific DNA methylation in SR-BI intronic regions may be associated with specific biological function(s) of these regions, including regulation of gene expression.

Introduction

Scavenger receptor class B, type I (SR-BI) is an integral plasma membrane protein that binds high density lipoprotein (HDL), low density lipoprotein (LDL), modified LDL, and very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) (Reaven et al., 2004). SR-BI mediates selective uptake of HDL-derived cholesteryl esters (CEs), a process in which HDL-CE is taken into cells without concomitant uptake and degradation of the HDL particle (Azhar and Reaven, 2002; Shen et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2015). This process drives the movement of cholesterol from peripheral tissues to the liver for excretion and is commonly referred to as “reverse cholesterol transport.” In human and rodent steroidogenic tissues, SR-BI transports the CEs into cells and regulates steroidogenesis (Azhar and Reaven, 2002). SR-BI is expressed most abundantly in liver, adrenal gland, ovary, and testis, tissues that exhibit highest selective HDL-CE uptake (Trigatti et al., 2000). The regulation of SR-BI expression occurs both at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels, whereas the protein could be glycosylated and phosphorylated (Babitt et al., 1997; Shen et al., 2014; Hu et al., 2015). In steroidogenic cells of the adrenal gland and gonads, SR-BI mRNA and protein expression are regulated by the tissue-specific trophic hormones, including estrogen, luteinizing hormone (LH)/human chorionic gonadotropin, and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) (Rigotti et al., 1996; Webb et al., 1997). Several transcription factors, such as SF-1, Sp1, Creb, yy1, and Srebf-1a, have been shown to regulate SR-BI expression (Lopez and McLean, 1999; Mizutani et al., 2000; Malerød et al., 2002). The protein but not mRNA level of hepatic SR-BI, however, is primarily regulated post-transcriptionally through protein–protein interaction with PDZK1/NHERF3 (Ikemoto et al., 2000; Kocher and Krieger, 2009). We previously showed that two other NHERF family members, NHERF1 and NHERF2, negatively regulate the protein level of SR-BI in steroidogenic cells (Hu et al., 2013). MicroRNAs-125a, -185, -455, -96, and -223 repress the SR-BI expression through directly binding to the 3′ UTR of SR-BI mRNA (Hu et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2013).

Gene expression can be regulated by epigenetic modifications such as DNA methylation, histone modifications, chromatin remodeling, and noncoding RNA hybridization. Among these, DNA methylation is one of the most widely studied forms of epigenetic modification (Jones and Takai, 2001; Bird, 2002; Egger et al., 2004). DNA methylation occurs by the covalent addition of a methyl group at the 5′ carbon of the cytosine ring, resulting in the formation of 5-methylcytosine (Bird, 2002). Clusters of CpGs, called CpG islands (CGIs), are often found in association with genes, most often in the promoters and first exons but also in regions more toward the 3′ end (Jones and Takai, 2001). Genome-scale DNA methylation analyses show that tissue-specific differentially methylated regions (tDMRs) are frequently in mammalian genomes and related to tissue-specific gene expression (Song et al., 2005; Rakyan et al., 2008; Yagi et al., 2008; Song et al., 2009).

As a long-term regulation of steroidogenesis, DNA methylation has been shown to regulate steroidogenesis by modifying genes at the transcription level, which are involved in this process. However, the information about the contribution of DNA methylation in the regulation of steroidogenesis remains unclear. There are a battery of proteins and enzymes that participate in steroidogenesis, such as SF-1, StAR, LDLR, CYP11A1, CYP17A1, and CYP19A1 (Schimmer and White, 2010). The patterns and the extent of DNA methylation particularly in SF-1 gene promoter may be modulated by DNA methylation inhibitor, 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (Azad), and prenatal caffeine ingestion (Liu et al., 2004; Ping et al., 2014). Moreover, an association has been demonstrated between activity of intronic enhancers and their DNA methylation in SF-1 gene (Hoivik et al., 2011). Published reports demonstrate an association between expression of LDLR, HSD11B2, and CYP17A1 genes and extent of methylation in the promoters of these genes (Flück and Miller, 2004; Alikhani-Koopaei et al., 2004; Zhi et al., 2007; Missaghian et al., 2009). In rat granulosa cell, the methylation status of CpG sites in StAR promoter as well as CYP19A1 promoter exhibits polymorphism (Lee et al., 2012). Treatment with parathyroid hormone induces active demethylation of the CpG sites in CYP27B1 gene promoter, whereas the parathyroid hormone was reported to stimulate CYP27B1 expression (Kim et al., 2009).

Although an earlier study has shown that caffeine could increase DNA methylation frequency in the proximal promoter of SR-BI in the adrenal gland (Wu et al., 2015), the underlying mechanism involved in the regulation of DNA methylation in SR-BI is not fully understood. In addition to one CGI in the SR-BI promoter, there are seven potential CGIs in SR-BI 11 introns (six CGIs in the first intron and one in the ninth intron). Again, neither the function of promoter DNA methylation on chromatin configuration and transcriptional regulation nor the role of gene body methylation is well understood. In this study, we characterized the DNA methylation profile of SR-BI gene in three commonly used steroidogenic model cells (mouse adrenal tumor Y1 cells, mouse Leydig tumor cells (MLTCs), and ovarian granulosa cells) and mouse liver hepa 1–6 cells by bisulfite sequencing PCR. We also treated these three steroidogenic cells with a second messenger of trophic hormone, N6, 2′-O-dibutyryladenosine3′:5′-cyclic monophosphate (Bt2cAMP), and assessed the changes in DNA methylation status in the SR-BI promoter and intronic CGIs. Thus, we characterized the polymorphism of DNA methylation in SR-BI gene in different steroidogenic and liver cells and evaluated the relationship between SR-BI expression and DNA methylation.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Bt2cAMP, insulin, transferrin, and hydrocortisone were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. Most of the tissue culture supplies were supplied by Life Technologies through its Gibco Cell Culture Media Division. The PCR and qPCR stuffs were purchased from TAKARA Biotechnology (Dalian) Co. Ltd. All other reagents used were of analytical grade.

Mice granulosa cells isolation and culture

All animal procedures in this investigation conform to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH publication No. 85-23, revised 1996) and the approved regulations set by the Laboratory Animal Care Committee at Nanjing Normal University. Female C57/BL6 mice were purchased from the Model Animal Research Center of Nanjing University. Granulosa cells were isolated from the ovaries using the follicle puncture method and cultured as described previously (Reaven et al., 1996; Manna and Stocco, 2011). In brief, cells were cultured in 35-mm culture dishes that were precoated with 1% serum. Dishes were plated with 1–2 × 105 cells in 1.5 mL of basal culture medium (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's-F12 medium supplemented with 15 mM Hepes, bovine serum albumin [1 mg/mL], insulin [2 μg/mL], transferrin [5 μg/mL], hydrocortisone [100 ng/mL], streptomycin [100 μg/mL], and penicillin G [100 U/mL]). After 72 h of culture, cells were treated with either vehicle alone or Bt2cAMP (2.5 mM) for 24 h to cause luteinization of the granulosa cells. Subsequently, the cells were maintained under their respective basal or stimulated (+Bt2cAMP) culture conditions for an additional 6 h.

Cell culture

Mouse adrenal Y1 cells (ATCC®-CCL-79™), MLTC-1, MLTCs (catalog No. CRL-2065™), and mouse liver hepa 1–6 cells (catalog No. CRL-1830™) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Y1 cells were cultured in Ham's F12 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. MLTC-1 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics. Hepa 1–6 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics. All cell cultures were maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2/95% air. Most of the tissue culture supplies were purchased from Life Technologies™ through its Gibco® Cell Culture Media Division. When required, cells were incubated with Bt2cAMP (2.5 mM) for an appropriate time (Manna and Stocco, 2011).

RNA extraction and quantitative PCR

Total RNA from different cell lines (Y1 cells, MLTCs, hepa 1–6 cells, and mouse granulosa cells) was extracted by miRNeasy mini kit (Qiagen). All the procedures were carried out according to manufacturer's protocol. The mRNA was then transcribed to first strand cDNA from 1 μg of total RNA by incubating for 15 min at 37°C with PrimeScript RT Master Mix (catalog. no. RR036A). Amplification of cDNAs was performed with an ABI StepOneplus system according to manufacturer's instructions. Each sample consisted of 2 μL cDNA (10 times diluted from original cDNA), 500 nM of each sense and antisense primer, 10 μL 2× SYBER Green premix, and 0.4 μL Rox (qPCR kit, catalog no. RR420A; TAKARA Biotechnology) in a final volume of 20 μL. 36B4 was used as an internal control (Laborda, 1991; Hu et al., 2012). All primers for qPCR are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers Used for Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction and Bisulfite Sequencing Polymerase Chain Reaction

| Primers for qPCR | |

| Mouse | 5′-GCTGTATCTGGCGCTTTTTC-3′-F |

| SR-BI | 5′-TCCGAATACCCTCTGGTGAG-3′-R |

| Mouse 36B4 | 5′-GAAAAGGTCAAGGCCTTCCT-3′-F |

| 5′-GAAAAGGTCAAGGCCTTCCT-3′-R | |

| Primers for bisulfite sequencing PCR | |

| Mouse | 5′-GGGTTGATTGTAATTGATTTTAATGTAGGGGAG-3′-F |

| SR-BI promoter CGI | 5′-CAACAACCCCAAAACGCCCAACCCC-3′-R |

| Mouse | 5′-AGGTTTATTTTAGAGGTTTGGTTTGAG-3′-F |

| SR-BI intron CGI-1 | 5′-CTCTCGAGACTGGCAGGCAGTGTGG-3′-R |

| Mouse | 5′-GTTTTGGTAGAGGTAGATACGATTTAGG-3′-F |

| SR-BI intron CGI-2 | 5′-CCTCGACAAACCTAAATCGTATCTACC-3′-R |

| Mouse | 5′-GGGTTGGTATAGAGATTAAGGATGG-3′-F |

| SR-BI intron CGI-3 | 5′-AATCAACTCCAAAATCCCTCCC-3′-R |

| Mouse | 5′-ATTATAAAGGTAGTGGATTAGAAGGAAGAG-3′-F |

| SR-BI intron CGI-4 | 5′-ATCACTAACAAAAAAAAACAACTATCCAC-3′-R |

| Mouse | 5′-GGAGGTGTTTTGATAAAGTAGGAGAG-3′-F |

| SR-BI intron CGI-5 | 5′-CTCAACTTCAATCCCCATACTACTCC-3′-R |

| Mouse | 5′-GGGAGGGAGGGAGATTAATGG-3′-F |

| SR-BI intron CGI-6 | 5′-CTTAACCTACGCCATAAACCCTCC-3′-R |

| Mouse | 5′-GGTTAAAGTGGGTTGGTTACGG-3′-F |

| SR-BI intron CGI-7 | 5′-CTCTATATAAACCACCTTCCCCTCC-3′-R |

CGI, CpG island; qPCR, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; SR-BI, scavenger receptor class B, type I.

Western blotting

Cells (Y1 cells, MLTCs, hepa 1–6 cells, and mouse granulosa cells) were harvested and homogenized in RIPA buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate) supplemented with complete protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche, catalog no. 11697498001). Equal amounts of protein samples (10–20 μg) were separated on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel elctrophoresis, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and detected using specific antibodies. Membranes were incubated with either rabbit anti-SR-BI or mouse anti-GAPDH (Santa Cruz Biotech) antibodies for 2 h. SR-BI polyclonal antibody was raised against a peptide to the C terminus of rat SR-BI (amino acids 489–509, AYSESLMSPAAKGTVLEQEAKL) (Hu et al., 2013). After three washes with Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20, the membranes were incubated with IRDye® 800CW goat antirabbit or IRDye® 6800LT goat antimouse secondary antibodies (LI-COR Biosciences) for 1.5 h. Proteins were detected with the Odyssey® Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences).

CGI prediction and bisulfite sequencing PCR assay

The potential CGIs were predicted in silico using the CpG Island Searcher (http://uscnorris.com/cpgislands2/cpg.aspx) (Takai and Jones, 2002). Mouse SR-BI gene sequence was got from GenBank (GenBank accession No., NP_001192011.1) and used for CGIs prediction. Genomic DNA was extracted from different cells (Y1 cells, MLTCs, hepa 1–6 cells, and mouse granulosa cells) and subjected to bisulfite modification using an EZ DNA Methylation-Gold kit (Zymo Research) according to manufacturer's protocol. PCR amplification (STAR polymerase; TAKARA Biotechnology) using primers specific for bisulfite-converted DNA sequence was carried out for different CGIs according to Table 1. PCR products were analyzed by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis, stained with ethidium bromide, and observed under UV illumination. The amplicons were then purified and cloned into a pGEM-T-easy vector (Promega) and subsequently sequenced and analyzed. PCR clones with <95% C to T conversion efficiency outside CpG sites were excluded from further analysis.

Statistical analysis

The Student's t-test was used to compare mRNA expression level and the percentage of CGI loci methylated or methylation level in control and cAMP-treated samples. For mRNA expression analysis, differences between groups were assessed by two-tailed, unpaired t-test. To compare means between paired samples, paired t-test was used for CpG DNA methylation level analysis. Statistica 10 software (StatSoft, Inc.) was used for analysis. p values of <0.05 were accepted as being statistically significant.

Results

Expression and hormonal regulation of SR-BI

SR-BI is expressed at high levels in parenchymal cells of liver and steroidogenic cells of adrenal and gonads (Trigatti et al., 2000). Hepatocytes and ovarian steroidogenic cells, such as luteinized ovarian granulosa cells, mouse Y1 cells, and MLTCs, express high but variable levels of SR-BI. In steroidogenic cells, SR-BI is primarily localized on the cell surface, and its expression is regulated by trophic hormones (ACTH or LH or follicle-stimulating hormone), which also regulate steroid hormone production (Rigotti et al., 1996; Webb et al., 1997). Treatment of Y1 cells, MLTCs, and granulosa cells with Bt2cAMP increased the mRNA (2.5 mM Bt2cAMP for 3 h) and protein (2.5 mM Bt2cAMP for 5 h) levels of SR-BI (Fig. 1A, B). Although high-dose estrogen treatment dramatically reduced SR-BI in the liver (Landschulz et al., 1996), the expression of SR-BI was significantly increased with Bt2cAMP treatment in hepa 1–6 liver cells (Fig. 1A, C). This result indicated that the regulation of liver SR-BI expression by estrogen might not be through the cAMP pathway.

FIG. 1.

Bt2cAMP-mediated expression and regulation of SR-BI. (A) mRNA expression of SR-BI in Y1 cells, MLTCs, ovarian granulosa cells, and hepa 1–6 cells treated with or without Bt2cAMP (2.5 mM for 3 h). (B) Bt2cAMP (2.5 mM for 5 h) upregulates SR-BI protein levels in Y1 cells, MLTCs, and granulosa cells. (C) SR-BI protein levels in hepatic hepa 1–6 cells treated with or without Bt2cAMP (2.5 mM for 5 h). ***p < 0.001. Bt2cAMP, N6, 2′-O-dibutyryladenosine3′:5′-cyclic monophosphate; MLTCs, mouse Leydig tumor cells; SR-BI, scavenger receptor class B, type I.

The CGI of SR-BI promoter and intronic regions

Mouse SR-BI gene spans 64,025 bp in chromosome 5 from exon 1 (1, transcription start site [TSS]) to the end of exon 12 (64,025, including transcript termination) (Fig. 2). To identify potential CGI in the promoter and intron regions of SR-BI gene, we analyzed the sequence corresponding to the promoter (−1900 to +355) and 11 introns of SR-BI in silico using the CpG Island Searcher. The selection criteria for a CGI included length >200 bp, GC content higher than 55%, and observed methylated CpG to expected CpG ratio higher than 0.65. One CGI was identified in the promoter region and seven CGIs in the introns (six CGIs in the first intron and one in the ninth intron) (Fig. 2). The SR-BI promoter CGI contained a total of 36 CpG sites in a region spanning −219/+264 bp relative to TSS. As shown in Figure 2, the CGIs in SR-BI gene introns varied in different regions both in size and the number of CpG sites. The presence of CpG sites in the promoter and intron raised the possibility that their transcriptional activities may be regulated by DNA methylation.

FIG. 2.

Schematic representation of mouse SR-BI gene structure and CpG islands prediction. The sequence data were obtained from GenBank (SR-BI gene id 20778; SR-BI isoform2 mRNA, Genbank accession No. NM_001205082.1). TSS, transcription start site.

Cell-specific and hormonal regulation of DNA methylation in the SR-BI promoter in steroidogenic cells

Caffeine has been shown to increase DNA methylation frequency in the proximal promoter region of the SR-BI (Wu et al., 2015). Trophic hormones, such as ACTH, regulate adrenal SR-BI expression through cAMP-PKA signaling pathway (Martin et al., 1999). Although SR-BI expression is induced by Bt2cAMP, the changes in the DNA methylation pattern of SR-BI promoter in response to Bt2cAMP treatment are largely unknown. We assessed the methylation status within the CGI region in the SR-BI gene promoter (−219 bp∼+264 bp) in different cells using bisulfite sequencing PCR assays. Positive clones were identified by PCR followed by sequencing. As shown in Figure 3, the methylation status of CGI in the SR-BI promoter was cell specific and hormonally regulated. (Note: black and white circles represent methylated and unmethylated CpGs, respectively). In Y1 cells, the Bt2cAMP treatment decreased the DNA methylation frequency in the SR-BI promoter from 21.94% to 8.89% (paired t-test: t = 8.24, df = 35, p < 0.001; Fig. 3A, B). In MLTCs, the DNA methylation frequency was decreased from 75% to 55.28% (paired t-test: t = 8.97, df = 35, p < 0.001; Fig. 3C, D). In contrast, promoter of SR-BI gene is hypomethylated in mouse ovarian granulosa cells (Fig. 3E). These studies demonstrate a cell-specific DNA methylation pattern in the promoter of SR-BI.

FIG. 3.

Effect of Bt2cAMP treatment on DNA methylation of SR-BI promoter. (A) Bt2cAMP treatment down regulated DNA methylation of SR-BI promoter in Y1 cells. (B) Frequency of DNA methylation at SR-BI promoter CpG sites in Y1 cells. (C) Bt2cAMP down regulated DNA methylation of SR-BI promoter in MLTCs. (D) Frequency of DNA methylation at SR-BI promoter CpG sites in MLTCs. (E) The SR-BI promoter is hypomethylated in ovarian granulosa cells with or without Bt2cAMP treatment. Black and white circles represent methylated and unmethylated CpGs, respectively. ***p < 0.001.

DNA methylation polymorphism of SR-BI gene intron CGIs in steroidogenic cells

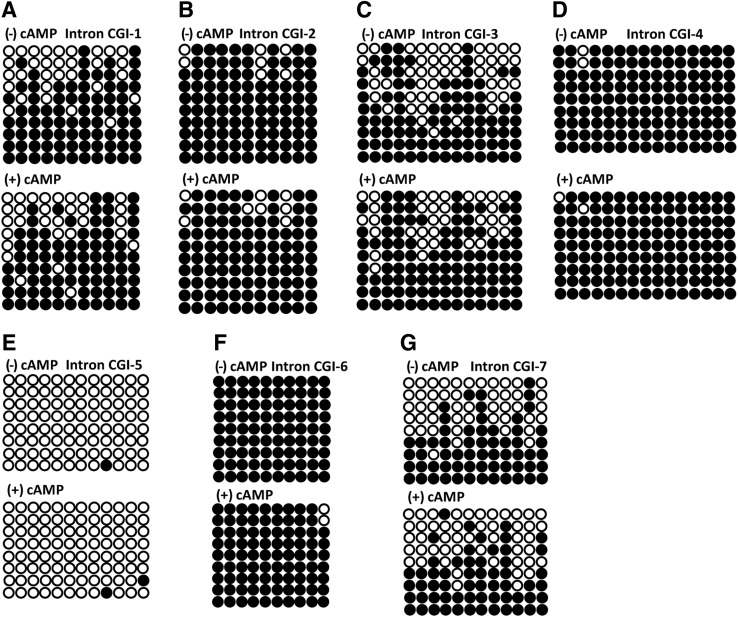

In the SF-1/Ad4BP gene, the DNA in three intronic enhancers (the fetal adrenal-specific enhancer, the VMH-specific enhancer, and the pituitary gonado-trope-specific enhancer) is differentially methylated in a tissue-specific manner (Hoivik et al., 2011). This led us to conclude that the DNA methylation in intronic regions has an effect on the gene expression and function. Thus, we attempted to illuminate the DNA methylation profile in the intronic regions in the SR-BI gene. We detected the DNA methylation in intron CGI of SR-BI gene in Y1 cells, MLTCs, granulosa cells, and hepa1–6 cells. Figure 4 shows the DNA methylation status at the CpG sites in the SR-BI intron region in Y1 cells. A total of 8 to 10 clones were analyzed in each case. The introns CGI-3, -4, -5, and -6 were hypermethylated, whereas introns CGI-1, -2, and -7 were hypomethylated.

FIG. 4.

DNA methylation status in SR-BI intron CpG islands in Y1 cells with or without Bt2cAMP treatment. (A–G) The DNA methylation in intron CGIs (intron CGI-1, …, -7) presented in Figure 2 was analyzed by bisulfite sequencing PCR. Black and white circles represent methylated and unmethylated CpGs, respectively. CGI, CpG island.

In comparison to Y1 cells, bisulfite sequencing revealed that the DNA was hypomethylated in the SR-BI gene intron CGI-5 in MLTCs (Fig. 5). In introns CGI-2, -4, and -6, the DNA was also hypermethylated both in MLTCs and in Y1 cells. Furthermore, in the intron CGI-3, there were several CpG sites that were unmethylated. Also, the frequencies of DNA methylation in introns CGI-1 and -7 in MLTCs were significantly higher than in Y1 cells.

FIG. 5.

DNA methylation status in SR-BI intron CpG islands in MLTCs with or without Bt2cAMP treatment. (A–G) The DNA methylation in intron CGIs (intron CGI-1, …, -7) presented in Figure 2 was analyzed by bisulfite sequencing PCR. Black and white circles represent methylated and unmethylated CpGs, respectively.

Although the DNA was hypomethylated in the promoter of SR-BI in granulosa cells, the DNA methylation frequencies in introns CGI-1 and -2 were relatively low (Fig. 6A, B). The DNA methylation status in introns CGI-3, -4, -5, and -6 in granulosa cells was comparable in Y1 cells, and all were hypermethylated (Fig. 6C–F). The frequency of DNA methylation in intron CGI-7 was similar in MLTCs. Above all, the DNA methylation profile in SR-BI intron CGIs was cell specific. However, our result also demonstrated that Bt2cAMP treatment of cells had no discernible effect on the DNA methylation pattern in SR-BI intron CGIs in all three types of steroidogenic cells examined (Y1 cells, MLTCs, and granulosa cells).

FIG. 6.

DNA methylation status in SR-BI intron CpG islands in ovarian granulosa cells with or without Bt2cAMP treatment. (A–G) The DNA methylation in intron CGIs (intron CGI-1, …, -7) presented in Figure 2 was analyzed by bisulfite sequencing PCR. Black and white circles represent methylated and unmethylated CpGs, respectively.

DNA methylation profile in hepa 1–6 cells

In the liver, SR-BI is mainly expressed in parenchymal cells (hepatocytes), which account for >90% of liver mass (Shen et al., 2014). Mouse liver tumor cell line hepa 1–6 cells expressed high level of SR-BI. We examined the DNA methylation profile of SR-BI in hepa 1–6 cells. As shown in Figure 7, the promoter CGI was hypomethylated both with and without Bt2cAMP treatment. The introns CGI-1 and -2 of SR-BI gene in hepa 1–6 cells were hypomethylated, whereas other intron CGIs were hypermethylated. Thus, hepa 1–6 cells exhibit a unique DNA methylation profile compared with the other cell types.

FIG. 7.

DNA methylation status in SR-BI promoter (A) and intron CpG islands (B–H) in hepa 1–6 cells. The DNA methylation in CpG islands presented in Figure 2 was analyzed by bisulfite sequencing PCR. Black and white circles represent methylated and unmethylated CpGs, respectively.

Discussion

Steroid hormone production can be divided into two broad stages: (1) cholesterol mobilization and (2) its catabolism to steroids by tissue-specific steroidogenic enzymes. There are three potential sources of cholesterol that can provide precursor cholesterol for steroidogenesis. The cholesterol can be synthesized de novo from acetate in the endoplasmic reticulum or directly obtained from exogenous circulating lipoproteins (Azhar and Reaven, 2002). Plasma lipoproteins, LDL, and HDL provide cholesterol for the steroid hormone production preferentially through LDL receptor endocytic and SR-BI-selective pathways, respectively (Shen et al., 2014).

SR-BI is expressed abundantly in liver and steroidogenic tissues. Its expression is regulated transcriptionally by trophic hormones and involves the participation of several transcription factors, including SF-1. Previously we provided the evidence that SR-BI expression is significantly up regulated by specific peptide hormones and cAMP in several model steroidogenic cells (Hu et al., 2012). DNA methylation in the promoter region represses gene transcription through inhibition of transcription factor binding or the recruitment of methyl-binding proteins (Robertson and Jones, 2000). DNA methylation was reported to be regulated by hormone treatment (Kim et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2012). We tried to clarify the hormonal regulation of SR-BI expression and DNA methylation. The SR-BI gene structure is similar in human (GenBank accession No., NP_001076428.1) and mouse (GenBank accession No., NP_001192011.1), and the CGI was identified both in human and mouse SR-BI gene promoter. Using bisulfite sequencing assay, we detected the DNA methylation in the SR-BI promoter region in several kinds of typical mouse SR-BI expression cell lines. In both Y1 cells and MLTCs, the CpG sites in the SR-BI promoter were partially methylated. The methylation frequencies were 21.94% and 75% in Y1 cells and MLTCs, respectively. After treatment of cells with Bt2cAMP, the methylation frequencies were reduced to 8.89% in Y1 cells and 55.28% in MLTCs. This reduced DNA methylation frequency was consistent with the increased SR-BI mRNA expression levels in these two cell types. Furthermore, these results indicated an association between hormone-dependent regulation of the SR-BI DNA methylation profile and mRNA expression for the first time. Interestingly, there was no methylated CpG sites in the promoter CGIs of SR-BI gene both in control and in Bt2cAMP-treated mouse ovarian granulosa. Thus, we wonder whether no DNA methylation in the SR-BI promoter in ovarian granulosa cell is species specific. We also detected the DNA methylation status in the SR-BI promoter in rat granulosa cell and got the same result as in the mouse (data not shown). This led us to conclude that the DNA methylation status in the SR-BI promoter was not linked to the SR-BI mRNA level in ovarian granulosa cells. These cell-specific DNA methylation polymorphisms are in accordance with the demonstration that in most promoters, methylation is associated with low gene expression, whereas some tDMRs are unmethylated that also have low gene expression (Robertson and Jones, 2000). In a model mouse liver cell line, hepa 1–6 cells, the CpG sites in the promoter CGI of SR-BI were also poorly methylated.

Although most of the earlier DNA methylation studies focused on the CGIs in the promoter region, relatively little is known about the DNA methylation profile in intragenic regions of individual genes. We analyzed the sequence of SR-BI intronic regions and identified seven potential CGIs (designated as intron CGI-1, intron CGI-2, intron CGI-3, intron CGI-4, intron CGI-5, intron CGI-6, and intron CGI-7) (Fig. 2). In Y1 cells, the intron CGI-1, intron CGI-2, and intron CGI-7 were partially methylated. Whereas the other four intron CGIs were almost completely methylated, only several sites were unmethylated in these four intron CGIs. In contrast,intron CGI-3, intron CGI-1, and intron CGI-7 were only partially methylated in MLTCs. However, the overall frequencies of DNA methylation were significantly higher than in Y1 cells. In MLTCs, DNA was hypermethylated in intron CGI-2, CGI-4, and CGI-6, whereas it was hypomethylated in intron CGI-5. In ovary granulosa cells, intron CGI-1 and intron CGI-2 were hypomethylated, intron CGI-7 was partially methylated, whereas the other intron CGIs were close to being fully methylated. In hepa 1–6 cells, however, intron CGI-1 and intron CGI-2 were hypomethylated, and the other five intron CGIs were hypermethylated. Thus, our analysis of DNA methylation showed varying levels of methylation in SR-BI intron CGIs in different SR-BI expressing cells. These differential results may be related to the different function of these intron CGIs in the regulation of SR-BI expression in different cell types. Interestingly, Bt2cAMP stimulation had no effect on the DNA methylation frequencies in SR-BI intron CGIs in steroidogenic cells. We speculate that hormone treatment increases SR-BI mRNA levels primarily by modifying the binding of transcription factor(s) to the promoter of SR-BI and less likely by altering the DNA methylation in intron of SR-BI.

In summary, we provide data showing the cell-specific DNA methylation profile in the SR-BI promoter and intron CGIs. We suggest that changes in DNA methylation in the SR-BI promoter by Bt2cAMP treatment may be responsible for the altered expression of SR-BI in Y1 cells and MLTCs. Additional studies are needed to further characterize the function of DNA methylation polymorphism in SR-BI intron CGIs. We believe that our data on the DNA methylation in SR-BI presented here will greatly aid in understanding the SR-BI gene structure and its relevance to SR-BI expression and DNA methylation in SR-BI expressing cells and tissues.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions, Natural Science Fund of Colleges, and Universities in Jiangsu Province (14KJB180012), National Natural Science Foundation of China (31400659), Jiangsu Provincial Natural Science Foundation (BK20140920), Office of Research and Development, Medical Service, Department of Veterans Affairs, and National Institutes of Health, NIHLB, Grant 2R01HL033881 (S.A.).

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interest exist.

References

- Alikhani-Koopaei R., Fouladkou F., et al. (2004). Epigenetic regulation of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 expression. J Clin Investig 114, 1146–1157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azhar S., and Reaven E. (2002). Scavenger receptor class BI and selective cholesteryl ester uptake: partners in the regulation of steroidogenesis. Mol Cell Endocrinol 195, 1–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babitt J., Trigatti B., Rigotti A., et al. (1997). Murine SR-BI, a high density lipoprotein receptor that mediates selective lipid uptake, is N-glycosylated and fatty acylated and colocalizes with plasma membrane caveolae. J Biol Chem 272, 13242–13249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird A. (2002). DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory. Genes Dev 16, 6–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger G., Liang G., Aparicio A., et al. (2004). Epigenetics in human disease and prospects for epigenetic therapy. Nature 429, 457–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flück C.E., and Miller W.L. (2004). GATA-4 and GATA-6 modulate tissue-specific transcription of the human gene for P450c17 by direct interaction with Sp1. Mol Endocrinol 18, 1144–1157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoivik E.A., Bjanesoy T.E., Mai O., et al. (2011). DNA methylation of intronic enhancers directs tissue-specific expression of steroidogenic factor 1/adrenal 4 binding protein (SF-1/Ad4BP). Endocrinology 152, 2100–2112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z., Hu J., Shen W.J., et al. (2015). A novel role of salt-inducible kinase 1 (SIK1) in the post-translational regulation of scavenger receptor class b type 1 activity. Biochemistry 54, 6917–6930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z., Hu J., Zhang Z., et al. (2013). Regulation of expression and function of scavenger receptor class B, type I (SR-BI) by Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factors (NHERFs). J Biol Chem 288, 11416–11435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z., Shen W.J., Kraemer F.B., et al. (2012). MicroRNAs 125a and 455 repress lipoprotein-supported steroidogenesis by targeting scavenger receptor class B type I in steroidogenic cells. Mol Cell Biol 32, 5035–5045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikemoto M., Arai H., Feng D., et al. (2000). Identification of a PDZ-domain-containing protein that interacts with the scavenger receptor class B type I. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97, 6538–6543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones P.A., and Takai D. (2001). The role of DNA methylation in mammalian epigenetics. Science 293, 1068–1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M.S., Kondo T., Takada I., et al. (2009). DNA demethylation in hormone-induced transcriptional derepression. Nature 461, 1007–1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocher O., and Krieger M. (2009). Role of the adaptor protein PDZK1 in controlling the HDL receptor SR-BI. Curr Opin Lipidol 20, 236–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laborda J. (1991). 36B4 cDNA used as an estradiol-independent mRNA control is the cDNA for human acidic ribosomal phosphoprotein PO. Nucleic Acids Res 19, 3998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landschulz K.T., Pathak R.K., et al. (1996). Regulation of scavenger receptor, class B, type I, a high density lipoprotein receptor, in liver and steroidogenic tissues of the rat. J Clin Invest 98, 984–995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee L., Asada H., Kizuka F., et al. (2012). Changes in histone modification and DNA methylation of the StAR and Cyp19a1 promoter regions in granulosa cells undergoing luteinization during ovulation in rats. Endocrinology 154, 458–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Li X.D., Vaheri A., et al. (2004). DNA methylation affects cell proliferation, cortisol secretion and steroidogenic gene expression in human adrenocortical NCI-H295R cells. J Mol Endocrinol 33, 651–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez D., McLean M.P. (1999). Sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1a binds to cis elements in the promoter of the rat high density lipoprotein receptor SR-BI gene 1. Endocrinology 140, 5669–5681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malerød L., Juvet L.K., Hanssen-Bauer A., et al. (2002). Oxysterol-activated LXRα/RXR induces hSR-BI-promoter activity in hepatoma cells and preadipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 299, 916–923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna P.R., and Stocco D.M. (2011). The role of specific mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling cascades in the regulation of steroidogenesis. J Signal Transduct, Article ID 821615, 13 pages [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin G., Pilon A., Albert C., et al. (1999). Comparison of expression and regulation of the high-density lipoprotein receptor SR-BI and the low-density lipoprotein receptor in human adrenocortical carcinoma NCI-H295 cells. Eur J Biochem 261, 481–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missaghian E., Kempná P., Dick B., et al. (2009). Role of DNA methylation in the tissue-specific expression of the CYP17A1 gene for steroidogenesis in rodents. J Endocrinol 202, 99–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizutani T., Yamada K., Minegishi T., et al. (2000). Transcriptional regulation of rat scavenger receptor class B type I gene. J Biol Chem 275, 22512–22519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ping J., Wang J., Liu L., et al. (2014). Prenatal caffeine ingestion induces aberrant DNA methylation and histone acetylation of steroidogenic factor 1 and inhibits fetal adrenal steroidogenesis. Toxicology 321, 53–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakyan V.K., Down T.A., Thorne N.P., et al. (2008). An integrated resource for genome-wide identification and analysis of human tissue-specific differentially methylated regions (tDMRs). Genome Res 18, 1518–1529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reaven E., Cortez Y., Leers-Sucheta S., Nomoto A., and Azhar S. (2004). Dimerization of the scavenger receptor class B type I: formation, function, and localization in diverse cells and tissues. J Lipid Res 45, 513–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reaven E., Tsai L., and Azhar S. (1996). Intracellular events in the “selective” transport of lipoprotein-derived cholesteryl esters. J Biol Chem 271, 16208–16217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigotti A., Edelman E.R., Seifert P., et al. (1996). Regulation by adrenocorticotropic hormone of the in vivo expression of scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI), a high density lipoprotein receptor, in steroidogenic cells of the murine adrenal gland. J Biol Chem 271, 33545–33549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson K.D., and Jones P.A. (2000). DNA methylation: past, present and future directions. Carcinogenesis 21, 461–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimmer B.P., and White P.C. (2010). Minireview: steroidogenic factor 1: its roles in differentiation, development, and disease. Mol Endocrinol 24, 1322–1337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W.J., Hu J., Hu Z., et al. (2014). Scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI): a versatile receptor with multiple functions and actions. Metabolism 63, 875–886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song F., Mahmood S., Ghosh S., et al. (2009). Tissue specific differentially methylated regions (TDMR): changes in DNA methylation during development. Genomics 93, 130–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song F., Smith J.F., Kimura M.T., et al. (2005). Association of tissue-specific differentially methylated regions (TDMs) with differential gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102, 3336–3341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takai D., and Jones P.A. (2002). Comprehensive analysis of CpG islands in human chromosomes 21 and 22. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99, 3740–3745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trigatti B., Rigotti A., and Krieger M. (2000). The role of the high-density lipoprotein receptor SR-BI in cholesterol metabolism. Curr Opin Lipidol 11, 123–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Jia X.J., Jiang H.J., et al. (2013). MicroRNAs 185, 96, and 223 repress selective high-density lipoprotein cholesterol uptake through posttranscriptional inhibition. Mol Cell Biol 33, 1956–1964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb N.R., De Villiers W.J., Connell P.M., et al. (1997). Alternative forms of the scavenger receptor BI (SR-BI). J Lipid Res 38, 1490–1495 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D.M., He Z., Ma L.P., et al. (2015). Increased DNA methylation of scavenger receptor class B type I contributes to inhibitory effects of prenatal caffeine ingestion on cholesterol uptake and steroidogenesis in fetal adrenals. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 285, 89–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi S., Hirabayashi K., Sato S., et al. (2008). DNA methylation profile of tissue-dependent and differentially methylated regions (T-DMRs) in mouse promoter regions demonstrating tissue-specific gene expression. Genome Res 18, 1969–1978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H., Yan L., Qian P., et al. (2015). Icariin inhibits foam cell formation by down-regulating the expression of CD36 and up-regulating the expression of SR-BI. J Cell Biochem 116, 580–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhi Y.F., Huang Y.S., Li Z.H., et al. (2007). Hypermethylation in promoter area of LDLR gene in atherosclerosis patients. J Mol Cell Biology 40, 419–427 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]