Abstract

We have investigated the role of phospholipase A2 (PLA2) enzymes in generating membrane tubules at the trans-Golgi network (TGN). Constitutive TGN membrane tubules and those induced by over-expressing kinase dead protein kinase D were inhibited by the PLA2 inhibitors ONO-RS-082 (ONO) and bromoenol lactone. These antagonists also inhibited secretory delivery of both soluble and transmembrane cargoes. Finally, use of the reversible antagonist ONO and time-lapse imaging revealed for the first time that PLA2 antagonists inhibit the initiation of membrane tubule formation at the TGN. Thus, PLA2 enzymes appear to have an important role in the earliest steps of membrane tubule formation at the TGN, which are utilized for membrane trafficking.

Keywords: membrane tubules, phospholipid remodeling, PKD, PLA2, TGN

Cargo exiting the trans-Golgi network (TGN) can be targeted to basolateral or apical plasma membranes or endosomes and may be concentrated in coated vesicles or membrane tubules. Some protein cargoes are found primarily in TGN-derived membrane tubules (1,2), whereas others are more often associated with vesicles that bud from the TGN (3,4). The mechanism of cargo sorting into either membrane tubules or coated vesicles, and how that cargo is targeted to endosomes or the plasma membrane, is largely unknown. For vesicular trafficking, recent studies have revealed a role for clathrin in the sorting and packaging of some proteins to the basolateral domain of epithelial cells (5). The current model for TGN tubule formation is that membrane domains in the TGN become enriched in transport cargo, but exclude resident TGN proteins (3). Tubules are then pulled from these domains with the help of kinesin and then undergo fission (2). Some of the factors involved in fission include heterotrimeric G proteins and protein kinase D (PKD) (6,7). Over-expression of the kinase inactive (dead) form of PKD, which inhibits secretory vesicle fission, leads to an extensive network of tubules from the TGN, but not the Golgi complex (8,9).

Fission of TGN secretory membrane tubules requires many factors including the phospholipids within the membrane itself. The metabolism of phosphatidic acid (PA), diacylglycerol (DAG) and phosphatidylinositol (PI) are all thought to have roles in tubule fission (3). PKD itself binds to DAG (9,10), which may act as a binding platform for the fission machinery that may include C-terminal-binding protein 3 (CtBP3)/brefeldin A-ADP-ribosylated substrate (BARS) (11). Certain phospholipids are also thought to generate unstable domains within the membrane that promote hemi-fission and eventual membrane fission by altering the curvature and physical properties of the membrane itself (3). Although a great deal is known about how TGN transport carriers separate from the donor membrane, little is known about how these extensive TGN tubules form. Previous studies have also suggested the importance of phospholipids in regulating not only the membrane tubule fission, but also membrane tubule formation (12).

A variety of pharmacological, biochemical and siRNA-mediated knockdown studies have implicated cytoplasmic phospholipase (PLA) enzymes in the generation and/or maintenance of membrane tubules (12–14). Specific cytoplasmic PLA1 and PLA2 enzymes have been shown to have a role in the formation of membrane tubules that function in retrograde trafficking from the Golgi (15), intra-Golgi movement of secretory cargo (16), assembly of an intact Golgi ribbon (17), delivery to the cell surface (16–18) and endocytic recycling (19). PLA enzymes generate lysophospholipids (LPLs), which may increase positive curvature on the cytosolic leaflet of organelle membranes leading to tubule formation (12). As PLA2 enzymes have been linked to membrane tubules in other organelles, PLA2 enzymes may also have a role in forming membrane tubule transport carriers at the TGN. In addition, although cytoplasmic PLA enzymes have been closely linked to membrane tubule formation, there is no direct evidence that PLA activity is required for the initiation of TGN membrane tubules in vivo.

Here, we use a pharmacological and live-cell imaging approach to examine the role of PLA2 enzymes in the formation of membrane tubules at the TGN. We conclude from the results that PLA2 activity is required for the initiation of membrane tubules from the TGN, which mediate export of secretory cargoes.

Results and Discussion

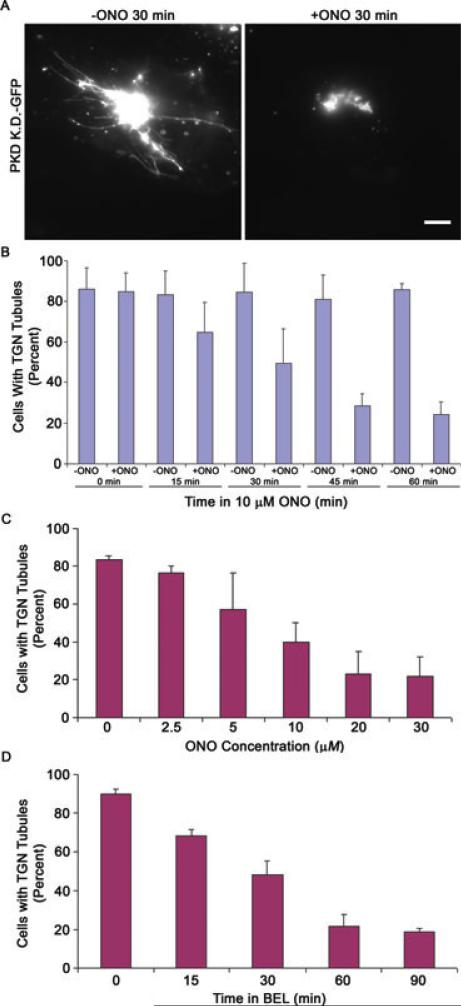

PKD-KD-induced TGN tubules are inhibited by PLA2 antagonists

The TGN has been shown to form clathrin-coated vesicles as well as membrane tubules and tubulo-vesicular clusters that transport secretory cargo to the plasma membrane and endosomes. We tested if cytoplasmic PLA2 enzymes have a role in the formation of these transport carriers by treating cells with PLA2 antagonists. The kinase dead (KD) form of PKD is known for generating dramatic TGN tubules, which result from the impediment of membrane tubule fission (8). Cells transfected with PKDKD-green fluorescent protein (GFP) exhibited numerous TGN membrane tubules, whereas transfected cells treated with ONO-RS-082 (ONO) did not (Figure 1A). Fewer cells contained TGN membrane tubules as early as 15 min after ONO addition, and by 60 min almost no cells contained membrane tubules (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. PLA2 antagonists inhibit PKD-KD-induced TGN membrane tubules.

HeLa cells transfected with PKD-KD-GFP were incubated with 10 μm ONO or a solvent control for up to 60 min. A) Cells without ONO had abundant TGN membrane tubules containing PKD-KD-GFP while after treatment with ONO for 30 min, few cells contained tubules. B) Cells were counted as containing TGN membrane tubules, or not, for each time-point. C) HeLa cells transfected with PKD-KD-GFP were treated with varying concentrations of ONO for 30 min. The number of cells with TGN tubules was counted. D) HeLa cells transfected with PKD-KD-GFP were treated with 10 μm BEL for up to 90 min. The number of cells containing TGN membrane tubules was counted. Error bars represent standard deviation for three independent experiments and 300 cells counted. Scale = 10 μm.

The inhibitory effects of ONO on TGN tubule formation were concentration dependent with an IC50 of 10 μM (Figure 1C). A second cytoplasmic PLA2 antagonist, bromoenol lactone (BEL), was also tested for any changes in TGN tubules. At 10 μM, BEL effectively inhibited TGN membrane tubules generated by PKD-KD as well (Figure 1D). Similar to ONO, BEL significantly diminished the number of cells with TGN tubules after 15 min. Our previous studies determined that these concentrations of ONO and BEL effectively inhibit cytoplasmic PLA2 activity (13,14,20).

ONO is a Ca2+-dependent-PLA2 (cPLA2) inhibitor with an IC50~10 μM; however, BEL inhibits Ca2+-independent-PLA2 (iPLA2) enzymes at 1 μM and cPLA2 enzymes at 10 μM. Little effect was seen when BEL was used at 1 μM (data not shown). This implies that a cPLA2 may be responsible for the formation of TGN tubules, consistent with previous studies that showed that cPLA2α is involved in TGN to plasma membrane trafficking (16,18). Taken together with previous data, evidence now exists for both iPLA2 and cPLA2 enzymes in membrane trafficking.

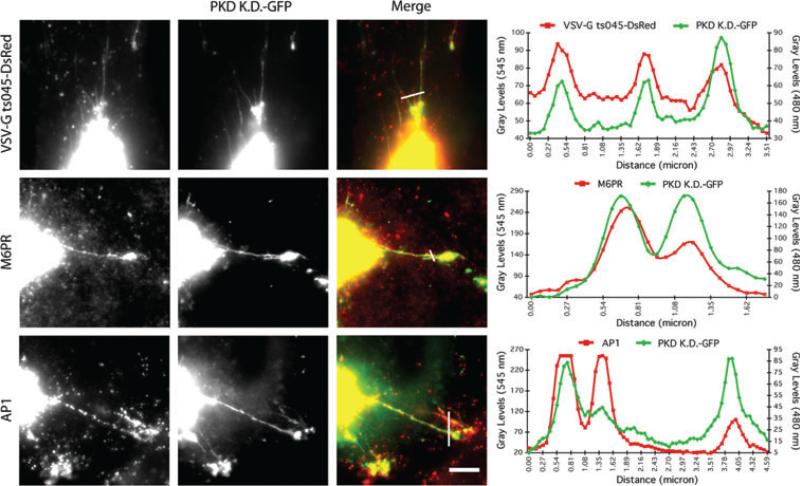

TGN membrane tubules induced by PKD-KD-GFP can contain proteins that would normally be exported to the plasma membrane, i.e. vesicular stomatitis virus G protein (VSV-G), and a subset of TGN markers (8). We asked if these membrane tubules also contain proteins that are normally sorted for export to endosomes such as cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptors (M6PRs) and AP-1 clathrin adaptors (21). Immunofluorescence localization in cells transfected with PKD-KD-GFP revealed that both M6PRs and AP-1 adaptors were found on these tubules, often in puncta (Figure 2). Previous studies have shown that PKD-KD over-expression does not effect trafficking of membrane proteins from the TGN to endosomes (8). Interestingly, Liljedahl et al. (8) did not find clathrin itself associated with PKD-KD-induced membrane tubules, whereas we clearly observed AP-1 staining. We currently have no explanation for this discrepancy, but our combined results suggest that M6PR-dependent sorting of lysosomal enzymes might occur normally on these membrane tubules, even though fission of VSV-G enriched vesicles is inhibited.

Figure 2. PKD-KD-GFP-induced TGN membrane tubules contain proteins destined for the plasma membrane and endosomes.

HeLa cells transfected with PKD-KD-GFP were incubated at 20°C for 2 h to block TGN secretion. Cells were shifted to the permissive temperature of 32°C for 30 min and then fixed and stained with antibodies against various TGN cargo proteins. Line intensity plots were generated using NIH ImageJ software. Scale = 10 μm.

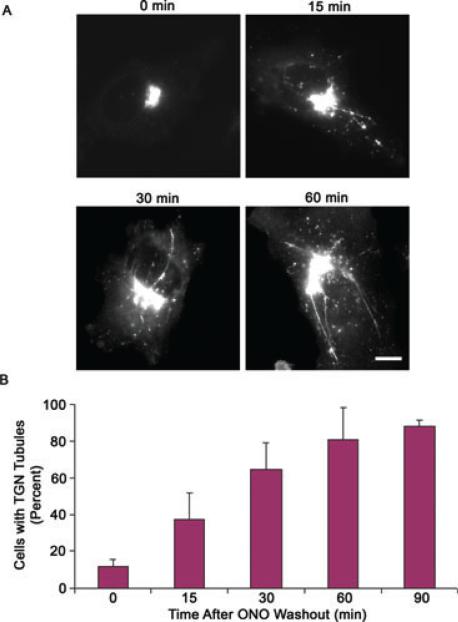

PLA2 activity is required for the formation of TGN tubules

To determine if PLA2 enzymes function in the formation and/or maintenance of TGN membrane tubules, we took advantage of ONO, which is reversible (13). Cells transfected with PKD-KD were treated with ONO for 60 min to ensure that nearly all cells lacked TGN membrane tubules. When cells were washed free of ONO, membrane tubules reformed at the TGN within 15 min (Figure 3A). Taken together, the PLA2 antagonists ONO and BEL appear to have a direct role in inhibiting the formation of TGN membrane tubules that contain the fission machinery PKD.

Figure 3. PLA2 antagonists inhibit the formation of TGN membrane tubules.

HeLa cells transfected with PKD-KD-GFP were treated with 10 μm ONO for 60 min. The media was then replaced without ONO and cells were visualized at various periods of time thereafter. A) Within 15 min of ONO washout, the TGN reformed membrane tubules which became more numerous and extensive after 30 and 60 min. B) Cells were counted for containing TGN membrane tubules at various time-points after ONO washout. After 60 min, nearly all cells contained tubules. Error bars represent standard deviation for three independent experiments and 300 cells counted. Scale = 10 μm.

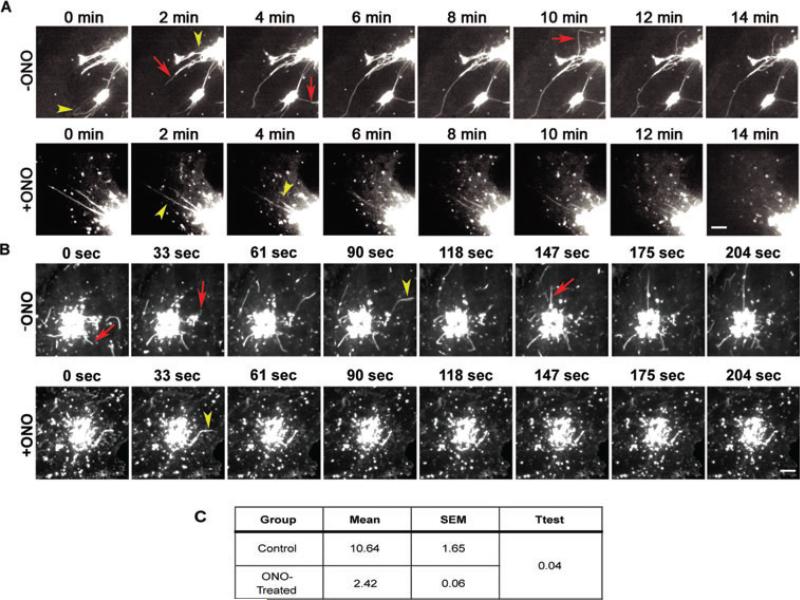

Although ONO decreases the number of cells containing PKD-KD-induced TGN membrane tubules, the fate of pre-existing tubules is unclear. Membrane tubules may sever from the TGN and/or retract back. As PKD-KD inhibits fission (8), the latter hypothesis is favored. To determine the fate of TGN membrane tubules after the addition of ONO, live-cell imaging was used to follow existing tubules before and after the addition of ONO. In untreated cells, TGN tubules containing PKD-KD-GFP were very dynamic and in a constant state of extension and retraction, as well as severing from the TGN (Figure 4A, Movie S1). Red arrows and yellow triangles indicate, respectively, forming/growing or retracting membrane tubules (Figure 4A). A similar dynamic was seen in cells treated with ONO, but tubules that either sever or retract were not replaced with new tubules (Figure 4B, Movie S2). This implies a role for PLA2 enzymes in the formation, but not necessarily the maintenance or fission of TGN membrane tubules.

Figure 4. Live-cell imaging of membrane tubules in cells over-expressing PKD-KD-GFP or ts045VSV-G-YFP.

In untreated cells, membrane tubules are dynamic in that they form, retract and/or break off. In cells treated with 10 μm ONO, membrane tubules similarly retract and break off, but do not reform. A) Control and ONO treated (10 μm) cells expressing PKD-KD-GFP. Micrographs were taken from Movies S1 and S2. B) Control and ONO treated (10 μm) cells expressing ts045VSV-G-YFP. Micrographs were taken from Movies S3 and S4. Red arrows indicate forming membrane tubules while yellow triangles indicate retracting tubules. C) Quantification of ts045VSV-G-YFP membrane tubules formed from the TGN over 5 min. Data represents three independent experiments with over 30 cells counted. A two-tailed Student's t-test with unequal variance was performed. A) Scale = 5 μm. B) Scale = 10 μm.

The above studies raise the question of whether or not PLA2 antagonists would similarly inhibit the initiation of membrane tubules that normally exit the TGN. To address this issue, cells expressing ts045VSV-G-YFP were subjected to a 20°C temperature block to accumulate it in the TGN, shifted to 32°C to induce export from the TGN and then imaged by time-lapse confocal microscopy. The results clearly showed that addition of ONO had a significant inhibitory effect on the initiation of ts045VSV-G-YFP-containing membrane tubules (Figure 4B,C, Movies S3 and S4). Similar to PKD-KD-induced membrane tubules, normal TGN membrane tubule retraction occurred in ONO, but few new ones formed.

Constitutive TGN to the plasma membrane trafficking requires PLA2 activity

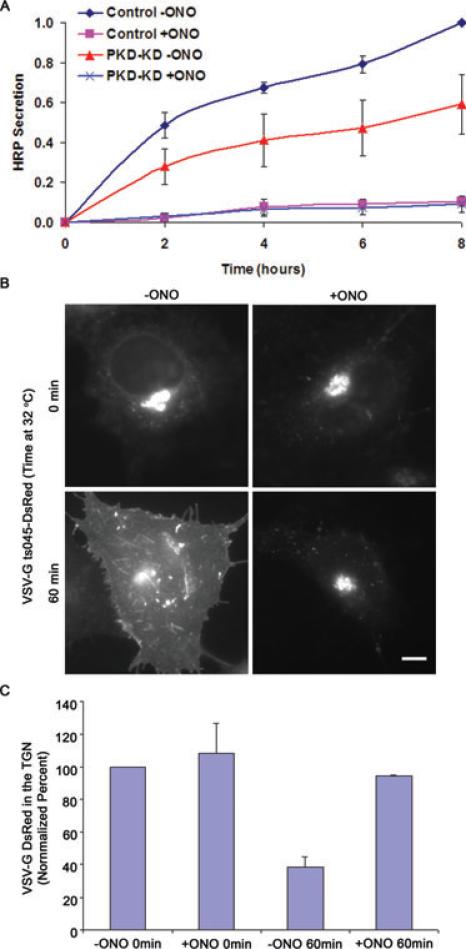

Although PLA2 antagonists clearly inhibit TGN membrane tubules generated by PKD-KD-GFP, their effect on constitutive export is not known. To see if ONO blocks bulk trafficking from the cell, a secreted form of horseradish peroxidase (ssHRP) was used to monitor secretion. Cells expressing PKD-KD have been previously shown to slow, although not completely block, the secretion of ssHRP (8). We found that cells treated with ONO were significantly inhibited in ssHRP secretion, even more so than cells expressing PKD-KD-GFP alone (Figure 5A). As expected, cells with PKD-KD-GFP and ONO also exhibited no significant secretion.

Figure 5. Constitutive trafficking from the TGN to the plasma membrane is inhibited by PLA2 antagonists.

HeLa cells were transfected with empty vector or PKD-KD-GFP for 24 h followed by transfection with ssHRP-FLAG for 24 h. Cells media was replaced and media samples were taken at the indicated times. A) Cells treated with 10 μm ONO had complete inhibition of ssHRP secretion and cells over-expressing PKD-KD-GFP had approximately 50% reduction in secretion. B) Cells transfected with ts045VSV-G-DsRed were incubated at 40°C for 18 h then 20°C for 3 h and then permissive temperature of 32°C for 60 min. Cells without ONO readily transported VSV-G to the plasma membrane within 60 min at the permissive temperature, while cells treated with 10 μm ONO retained VSV-G in the TGN. C) TGN-localized VSV-G was quantified by measuring fluorescence intensity of DsRed in the TGN versus the entire cell. Numbers were normalized to control and show that ONO blocked ts045VSV-G-DsRed escape from the TGN. Scale = 10 μm.

Because ONO could inhibit secretory trafficking at multiple stages, we used the well-characterized ts045VSV-G-DsRed, as above, to examine its export from different organelles. Cells were incubated at 40°C for 18 h to accumulate ts045VSV-G-DsRed in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and then shifted to 20°C to allow its transport to the TGN. Both control and ONO treated cells showed an accumulation of VSV-G in the TGN at 20°C (Figure 5B), indicating that ONO did not inhibit transport from the ER to the TGN. However, when cells expressing ts045VSV-G-DsRed in the TGN were shifted to 32°C for 60 min to allow transport to the plasma membrane, only the control cells exhibited significant cell surface localization (Figure 5B,C). ONO treated cells retained ts045VSV-G-DsRed in the TGN at similar levels seen before the temperature shift. Also, ONO treated cells contained many fewer TGN membrane tubules labeled with ts045VSV-G-DsRed. These results strongly indicate a role for PLA2 enzymes in generating membrane tubule transport carriers at the TGN.

Conclusions

Our studies provide the first evidence that PLA2 activity is important for membrane tubule-mediated export from the TGN to the plasma membrane. We found that the PLA2 antagonists ONO and BEL inhibit TGN tubules induced by the over-expression of PKD-KD. The effect is concentration dependent as well as reversible. In addition, ONO also blocks TGN to plasma membrane transport of both soluble cargo (ssHRP) and transmembrane cargo (VSV-G). Using live-cell imaging, we observed the dynamics of normal TGN membrane tubules and those generated by PKD-KD. Our data showed that ONO had little effect on existing tubules, but prevented the formation of new tubules. Although other data has suggested that PLA2 activity is important for the initiation or maintenance of Golgi membrane tubules (12), studies here are the first to provide evidence that PLA2 activity is primarily required for the initiation of TGN membrane tubule formation in vivo.

We hypothesize that PLA2 enzymes generate LPLs with large head groups and free fatty acids that may be able to alter the membrane from a flat surface to a curved membrane, as LPLs are shaped like inverted cones instead of cylindrical phospholipids. This change in membrane morphology may be critical for forming the shape of a membrane tubule, in the binding of curvature-inducing proteins (22,23), and/or in the recruitment of fission-inducing proteins such as CtBP3/BARS (4).

Finally, it is becoming increasingly clear that Lands Cycle remodeling of phospholipids to regulate the PL:LPL ratio plays a key role in regulating the structure and function of the Golgi complex and TGN (24). This remodeling appears to be important for both membrane curvature changes and the scission of tubules and coated vesicles. Three cytoplasmic phospholipases, PAFAH Ib, iPLA2γ and cPLA2α, influence membrane curvature at the Golgi by producing LPLs that likely contribute to these processes (15–17). In addition, recent work has shown that reacylation of LPLs by a Golgi-associated lysophosphatidic acid acyltransferase 3 (LPAAT3) is important for export from the TGN and overall Golgi morphology (24–26). LPAAT3 generates PA, which can be used to alter membrane curvature and recruit important effectors such as CtBP3/BARS. In addition, PA can be converted to DAG to recruit PKD for membrane fission (3). PA and DAG are also involved in coat protein I (COPI) vesicle and tubule formation from the Golgi stack (27–29). Thus, similar to the requirement for continual remodeling of PI by PI kinases and PI phosphatases (30), Golgi membrane trafficking events require continual phospholipid remodeling by PLA2 and LPAAT enzymes.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and imaging

HeLa cells were grown in minimal essential media (MEM) (MediaTech) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (MediaTech) and grown at 37°C with 5% CO2 unless otherwise indicated. Fugene (Roche) was used for transient transfections according to manufacturer's instructions. The inhibitors ONO and BEL (Biomol) were made in stock solution in ethanol unless otherwise indicated and added to MEM in the absence of FBS. For visualization of steady-state conditions, cells were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS pH 7.4 for 10 min and processed for immunofluorescence as previously described (31). For colocalization analysis, cells transfected with PKD-KD-GFP were incubated at 20°C for 2 h to block secretion at the TGN. Cells were shifted to the permissive temperature of 32°C for 30 min. Cells were then fixed and stained as described using rabbit anti-bovine cation-independent M6PR (32) and mouse anti-AP-1 (Sigma–Aldrich). Imaging and cell quantification was done using the Zeiss Axioscope2 and National Institutes of Health (NIH) ImageJ software. For live-cell imaging, media was changed to MEM with 10 mm HEPES and one-tenth sodium bicarbonate concentration. For ts045VSV-G-YFP live-cell imaging, cells were incubated at the restrictive temperature of 20°C to block ts045VSV-G-YFP trafficking out of the TGN. Then cells were shifted to the permissive temperature of 32°C with or without 10 μm ONO and imaged. All confocal images and time-lapse movies were generated using the Perkin-Elmer Ultraview spinning disk confocal microscope.

DNA constructs

PKD-KD-GST and ssHRP-FLAG were both generous gifts from Dr Vivek Malhotra. PKD-KD was cut from the parent vector with SmaI and SalI and ligated into pEGFP-C1 (Clontech) to generate PKD-KD-GFP. Ts045VSV-G-YFP was a generous gift from Dr Brian Storrie and was cut from the parent vector using BamHI and XhoI and ligated into pEDsRed N-1 (Clontech).

ssHRP and VSV-G secretion assays

Cells were transfected with ssHRP-Flag for 24 h. Cell media was removed and the cells were washed 3× and replaced with fresh media. To sample HRP activity in the media, 50 μL of media was removed from the culture dishes for every time-point and to measure non-secreted HRP activity, the cells were scraped from the dishes, incubated in PBS +1% NP-40 for 10 min and microcentrifuged to remove cell debris. For each sample, 10 μL was incubated with 50 μL of 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine reagent (Sigma–Aldrich). When samples turned blue, 50 μL of 1 m HCl was added to stop the reaction. All reactions were done in duplicate and measured using the SpectraMax 190 (Molecular Devices) 96-well plate reader at 450 nm. To measure ts045 VSV-G DsRed localization, 100 images from fixed cells were processed using ImageJ software (NIH) to measure the pixel intensity in the Golgi and total cell regions of interest (ROI). Background values of pixel intensity per unit area were measured and subtracted from each ROI.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Vivek Malhotra for the PKD-KD and ssHRP construct and Dr Brian Storrie for the ts045VSV-G-YFP construct. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, DK 51596 (to W. J. B.).

Footnotes

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- 1.Hirschberg K, Miller CM, Ellenberg J, Presley JF, Siggia ED, Phair RD, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Kinetic analysis of secretory protein traffic and characterization of Golgi to plasma membrane transport intermediates in living cells. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1485–1503. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.6.1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polishchuk EV, Di Pentima A, Luini A, Polishchuk RS. Mechanism of constitutive export from the Golgi: bulk flow via the formation, protrusion, and en bloc cleavage of large trans-Golgi network tubular domains. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:4470–4485. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-01-0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bard F, Malhotra V. The formation of TGN-to-plasma-membrane transport carriers. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006;22:439–455. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.012704.133126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Matteis MA, Luini A. Exiting the Golgi complex. Nat Rev. 2008;9:273–284. doi: 10.1038/nrm2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deborde S, Perret E, Gravotta D, Deora A, Salvarezza S, Schreiner R, Rodriguez-Boulan E. Clathrin is a key regulator of basolateral polarity. Nature. 2008;452:719–723. doi: 10.1038/nature06828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diaz Anel AM, Malhotra V. PKCeta is required for beta1gamma2/ beta3gamma2- and PKD-mediated transport to the cell surface and the organization of the Golgi apparatus. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:83–91. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200412089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeaman C, Ayala MI, Wright JR, Bard F, Bossard C, Ang A, Maeda Y, Seufferlein T, Mellman I, Nelson WJ, Malhotra V. Protein kinase D regulates basolateral membrane protein exit fromtrans-Golgi network. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:106–112. doi: 10.1038/ncb1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liljedahl M, Maeda Y, Colanzi A, Ayala I, Van Lint J, Malhotra V. Protein kinase D regulates the fission of cell surface destined transport carriers from the trans-Golgi network. Cell. 2001;104:409–420. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00228-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maeda Y, Beznoussenko GV, Van Lint J, Mironov AA, Malhotra V. Recruitment of protein kinase D to the trans-Golgi network via the first cysteine-rich domain. EMBO J. 2001;20:5982–5990. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.21.5982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baron CL, Malhotra V. Role of diacylglycerol in PKD recruitment to the TGN and protein transport to the plasma membrane. Science. 2002;295:325–328. doi: 10.1126/science.1066759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonazzi M, Spano S, Turacchio G, Cericola C, Valente C, Colanzi A, Kweon HS, Hsu VW, Polishchuck EV, Polishchuck RS, Sallese M, Pulvirenti T, Corda D, Luini A. CtBP3/BARS drives membrane fission in dynamin-independent transport pathways. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:570–580. doi: 10.1038/ncb1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown WJ, Chambers K, Doody A. Phospholipase A2 (PLA2) enzymes in membrane trafficking: mediators of membrane shape and function. Traffic. 2003;4:214–221. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2003.00078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Figueiredo P, Drecktrah D, Katzenellenbogen JA, Strang M, Brown WJ. Evidence that phospholipase A2 activity is required for Golgi complex and trans Golgi network membrane tubulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:8642–8647. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Figueiredo P, Polizotto RS, Drecktrah D, Brown WJ. Membrane tubule-mediated reassembly and maintenance of the Golgi complex is disrupted by phospholipase A2 antagonists. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:1763–1782. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.6.1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morikawa RK, Aoki J, Kano F, Murata M, Yamamoto A, Tsujimoto M, Arai H. Intracellular phospholipase A1gamma (iPLA1γ) is a novel factor involved in coat protein complex I- and Rab6-independent retrograde transport between the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi complex. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:26620–26630. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.038869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.San Pietro E, Capestrano M, Polishchuk EV, DiPentima A, Trucco A, Zizza P, Mariggio S, Pulvirenti T, Sallese M, Tete S, Mironov AA, Leslie CC, Corda D, Luini A, Polishchuk RS. Group IV phospholipase A(2)α controls the formation of inter-cisternal continuities involved in intra-golgi transport. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000194. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bechler ME, Doody AM, Racoosin E, Lin L, Lee KH, Brown WJ. The phospholipase complex PAFAH Ib regulates the functional organization of the Golgi complex. J Cell Biol. 2010;190:45–53. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200908105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Regan-Klapisz E, Krouwer V, Langelaar-Makkinje M, Nallan L, Gelb M, Gerritsen H, Verkleij AJ, Post JA. Golgi-associated cPLA2α regulates endothelial cell-cell junction integrity by controlling the trafficking of transmembrane junction proteins. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:4225–4234. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-02-0210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Figueiredo P, Doody A, Polizotto RS, Drecktrah D, Wood S, Banta M, Strang M, Brown WJ. Inhibition of transferrin recycling and endosome tubulation by phospholipase A2 antagonists. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47361–47370. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108508200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Figueiredo P, Drecktrah D, Polizotto RS, Cole NB, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Brown WJ. Phospholipase A2 antagonists inhibit constitutive retrograde membrane traffic to the endoplasmic reticulum. Traffic. 2000;1:504–511. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2000.010608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghosh P, Dahms NM, Kornfeld S. Mannose 6-phosphate receptors: new twists in the tale. Nat Rev. 2003;4:202–212. doi: 10.1038/nrm1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kooijman EE, Chupin V, de Kruijff B, Burger KN. Modulation of membrane curvature by phosphatidic acid and lysophosphatidic acid. Traffic. 2003;4:162–174. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2003.00086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Meer G, Sprong H. Membrane lipids and vesicular traffic. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16:373–378. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bankaitis VA. The Cirque du Soleil of Golgi membrane dynamics. J Cell Biol. 2009;186:169–171. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200907008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drecktrah D, Chambers K, Racoosin EL, Cluett EB, Gucwa A, Jackson B, Brown WJ. Inhibition of a Golgi complex lysophospholipid acyltransferase induces membrane tubule formation and retrograde trafficking. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:3459–3469. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-11-0711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmidt JA, Brown WJ. Lysophosphatidic acid acyltransferase 3 regulates Golgi complex structure and function. J Cell Biol. 2009;186:211–218. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200904147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Asp L, Kartberg F, Fernandez-Rodriguez J, Smedh M, Elsner M, Laporte F, Barcena M, Jansen KA, Valentijn JA, Koster AJ, Bergeron JJ, Nilsson T. Early stages of Golgi vesicle and tubule formation require diacylglycerol. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:780–790. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-03-0256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fernandez-Ulibarri I, Vilella M, Lazaro-Dieguez F, Sarri E, Martinez SE, Jimenez N, Claro E, Merida I, Burger KN, Egea G. Diacylglycerol is required for the formation of COPI vesicles in the Golgi-to-ER transport pathway. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:3250–3263. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-04-0334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang JS, Gad H, Lee SY, Mironov A, Zhang L, Beznoussenko GV, Valente C, Turacchio G, Bonsra AN, Du G, Baldanzi G, Graziani A, Bourgoin S, Frohman MA, Luini A, et al. A role for phosphatidic acid in COPI vesicle fission yields insights into Golgi maintenance. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1146–1153. doi: 10.1038/ncb1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Matteis MA, Godi A. PI-loting membrane traffic. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:487–492. doi: 10.1038/ncb0604-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drecktrah D, Brown WJ. Phospholipase A2 antagonists inhibit nocodazole-induced Golgi ministack formation: evidence of an ER intermediate and constitutive cycling. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:4021–4032. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.12.4021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown WJ, Farquhar MG. The distribution of the 215 kD mannose 6-phosphate receptors within cis (heavy) and trans (light) Golgi subfractions varies in different cell types. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:9001–9005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.9001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.