Abstract

Vitamin B12 is necessary for formation of red blood cells, DNA synthesis, neural myelination, brain development, and growth. Vitamin B12 deficiency is often asymptomatic early in its course; however, once it manifests, particularly with neurological symptoms, reversal by dietary changes or supplementation becomes less effective. Access to easy, low cost, and personalized nutritional diagnostics could enable individuals to better understand their own deficiencies as well as track the effects of dietary changes. In this work, we present the NutriPhone, a mobile platform for the analysis of blood vitamin B12 levels in 15 minutes. The NutriPhone technology comprises of a smartphone accessory, an app, and a competitive-type lateral flow test strip that quantifies vitamin B12 levels. To achieve the detection of sub-nmol/L physiological levels of vitamin B12, our assay incorporates an innovative “spacer pad” for increasing the duration of the key competitive binding reaction and uses silver amplification of the initial signal. We demonstrate the efficacy of our NutriPhone system by quantifying physiologically relevant levels of vitamin B12 and performing human trials where it was used to accurately evaluate blood vitamin B12 status of 12 participants from just a drop (~40 μl) of finger prick blood.

Vitamin B12 is a water-soluble vitamin that is necessary for DNA synthesis, the metabolism of amino acids and fatty acids1 which are required for normal blood formation2, cell synthesis3, and neurological functions4,5 in the human body. Low levels of vitamin B12 can consequently lead to a wide range of hematologic and neurological abnormalities6,7. Specifically, poor vitamin B12 status has been associated with several acute and chronic conditions including anaemia7,8, paraesthesia1,9, and cognitive impairments10. Vitamin B12 deficiency during pregnancy and early in life is also associated with neural tube defects, poor infant growth and psychomotor function, and impaired brain development11. The primary dietary sources of vitamin B12 are meats, fish, shellfish, and dairy products and as such the deficiency has been reported to be the highest among populations with predominantly a vegetarian or vegan diet12,13. In the US, the deficiency rate among vegetarians has been estimated at 60%14, while the rate as high as 81% has been reported in India15 where there is a high percentage of vegetarians and vegans16.

Depending on the severity, underlying cause, and if detected early, the manifestations of vitamin B12 deficiency can often be reversed by consuming supplements and/or by changes in diet, as recommended by a healthcare practitioner. In an attempt to reduce the barrier to diagnosis of micronutrient deficiencies, our group has previously developed the vitaAID – vitamin AuNP-based Immunoassay Device – a system for colorimetric quantification of vitamin D levels on a smartphone17. In that work a novel gold nanoparticle (AuNP) based immunoassay for vitamin D was developed and anlayzed by our smartphone platform, enabling quantification of serum samples without the need of sophisticated laboratory equipment such as spectrophotometers. However its deployment for point-of-care (POC) applications was limited by the persisting requirements for off-chip blood sample processing, multiple pipetting steps and the non-trivial incubation time (~3 h).

A possible solution to the aforementioned limitations is the adaptation of lateral flow immunoassay principles to diagnose micronutrient deficiencies. Lateral flow assays are widely used in diagnosing numerous diseases18,19,20 and medical conditions21,22,23 in POC settings because they are rapid, simple and produce simple qualitative results that can be interpreted by untrained personnel. Development of lateral flow test for B12 however is significantly more challenging due to the extremely low limit of detection that is required. One of the recommended cut-offs for vitamin B12 insufficiency is defined in humans by serum vitamin B12 below 221 pmol/L24 (compared with 50–75 nmol/L 25(OH)D for vitamin D25). Traditionally commercial lateral flow assays have lower limits of detection in the tens of nmol/L range26.

Here we present a novel POC vitamin B12 assessment test, implement it on our “NutriPhone” mobile platform, and demonstrate its performance in a series of human trials. The test uses a finger-stick of blood and comprises of a novel competitive-type lateral flow assay which is able to process whole blood samples, store the necessary reagents, and has built-in flow control directly on the test strip. Controlled and repeatable imaging of the B12 test strips with the smartphone platform, and computational image processing via the smartphone app enable the NutriPhone system to provide quantitative information from traditionally non-quantitative lateral flow test strips. As in other smartphone based diagnostics systems, our system inherits the abilities to track changes with time, provide user-free error tracking, and communicate results via e-mail or social networking service27,28,29,30,31.

In this paper we describe the NutriPhone system and demonstrate how the incorporation of an innovative “spacer pad” for an extended competitive binding interaction, silver enhancement of the initial colorimetric signal32, and optical detection via a smartphone platform push the limit-of-detection (LOD) of our B12 lateral flow assay into the required range. We show that vitamin B12 levels in standard solutions can be accurately quantified in less than 15 min by evaluating the ratio of test to control line signals (T/C ratio). We then validate the performance of our vitamin B12 assay in a small trial with human participants.

Results

NutriPhone system and vitamin B12 test operation

The NutriPhone system consists of: a reusable smartphone accessory, a disposable custom test strip for vitamin B12, and a smartphone app. The accessory has been designed to accept test strips and align them to a CMOS camera with an embedded focusing lens (f = 12 mm) in the optical path, which allows for capturing focused images of test strip signals in a compact accessory space. In order to minimize the variability caused by the different external lighting conditions, the accessory relies on two white surface mount LEDs (placed 10 mm on either sides focusing lens, facing the test strip 12 mm away) to uniformly illuminate the front of the test strip while blocking the ambient light entrance. While more LEDs could be adapted (e.g. to illuminate from other angles) to improve the uniformity further, they were compromised for longer accessory operation using two AA batteries at 3 V.

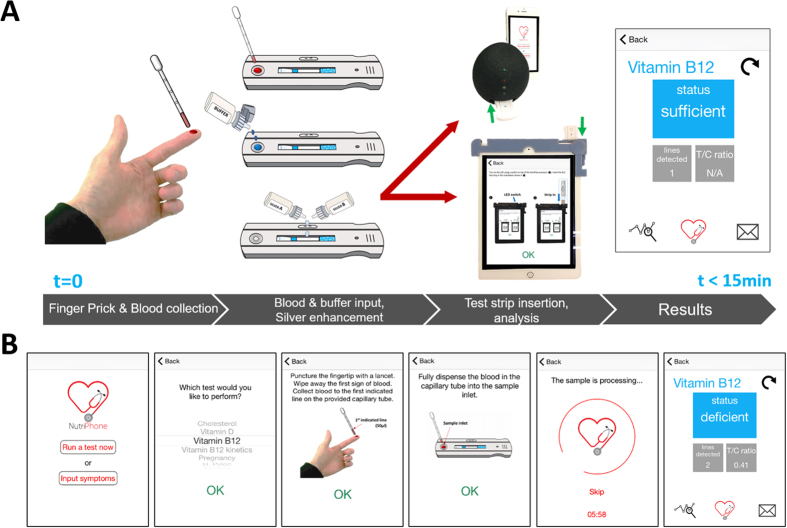

To run a vitamin B12 deficiency test in POC settings as shown in Fig. 1a, the user starts the NutriPhone app on his or her smartphone and follows the step-by-step instructions as shown in Fig. 1b. Briefly, the user collects a whole blood sample via a finger prick and applies it directly onto the test strip’s inlet. After allowing for 4 min of incubation, the user initiates the sample flow by applying droplets of the chase buffer from the dropper bottle. The colorimetric signal develops in the subsequent 6 min after which the signals are amplified by applying a droplet of silver enhancement solution from the respective dropper bottles. The user then inserts the test strip into the NutriPhone accessory, and the amplified colorimetric signals are captured by the smartphone camera after 2 min and anlayzed by the smartphone app for the total start-to-results time of less than 15 min.

Figure 1. NutriPhone system for PON vitamin B12 analysis.

(A) System overview showing the custom B12 test strip that accepts and anlayzes whole blood samples, two versions of the smartphone based accessory that accurately read the test strips, and smartphone app (B) NutriPhone app for guiding the users step-by-step through the test protocol and displaying the B12 results at the end.

Vitamin B12 lateral flow assay architecture and principles

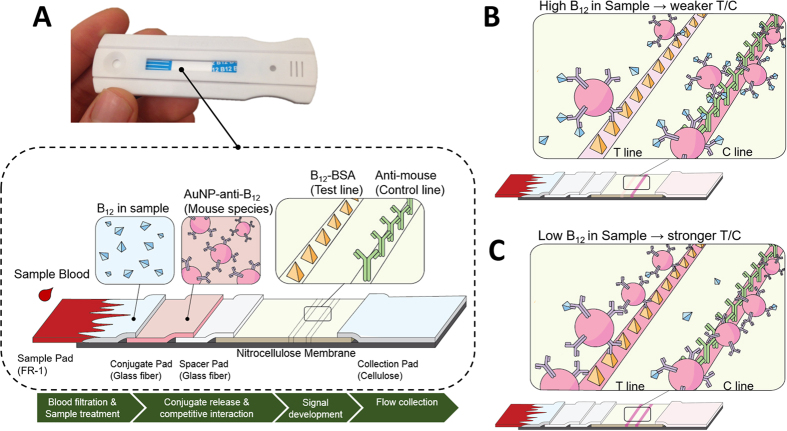

The custom vitamin B12 test strip shown in Fig. 2a was developed as a lateral flow assay which integrates: a whole blood filtration membrane (FR-1), a conjugate pad that dry-stores the AuNP-anti-B12 conjugates, a novel spacer pad that allows for longer sample interaction with AuNP-anti-B12 conjugates, a nitrocellulose membrane that immobilizes the vitamin B12-BSA molecules and secondary antibodies as test and control lines respectively, and a cellulose fibre absorbent pad that collects the waste sample at the end. This architecture represents a competitive-type lateral flow assay which was used here to accommodate the small size of vitamin B12 molecules (~1355 g/mol) that prevents their binding to more than one antibody at time33,34.

Figure 2. Vitamin B12 Lateral Flow Assay.

(A) Strip image and schematic of the custom B12 test strip architecture and components (B) Competitive interaction between the sample B12 and bound BSA-B12 at test line for a limited binding regions on AuNP-anti-B12 results in a weak T/C signal intensity for high B12 in the sample, and (C) strong T/C signal intensity for low B12 in the sample.

When a blood sample is applied onto the sample pad of our vitamin B12 assay, the blood cells are filtered and only the plasma proceeds to the conjugate pad and releases the AuNP-anti-B12 conjugates that become free to interact with the B12 in the sample. The sample to AuNP-anti-B12 interaction is the critical step in our assay, where there are limited binding regions on the AuNP-anti-B12 and their interaction with the sample B12 determines their availability downstream for binding to the BSA-B12 on the test line. In conventional lateral flow assays, such interaction occurs over tens of seconds which is too short for an accurate and thorough binding reactions to occur, especially when the target molecules are found in low (i.e. sub-nmol/L) concentrations. The innovation in our NutriPhone B12 assay that enables the detection of sub-nmol/L B12 has been the addition of the spacer pad between the conjugate pad and the nitrocellulose membrane. This spacer pad effectively prevents the sample—AuNP-anti-B12 mixture from flowing onto the nitrocellulose membrane before additionally activated by the user, thereby allowing for a more thorough interaction. In our optimized NutriPhone protocol, the user allows an additional 4 min of interaction time between the sample B12 and the AuN-anti-B12 before adding chase buffers to complete the test. For samples with high B12 levels as shown in Fig. 2b, most of the AuNP-anti-B12 conjugates are occupied with B12 molecules from the initial sample, resulting in only a subtle change in the colorimetric signal at the test line. Here the preoccupied AuNP-anti-B12 that pass the test line without binding are still captured by the secondary antibodies on the control line to exhibit a strong signal, which leads to weak T/C ratios for testing high B12 samples. For samples with low B12 levels as shown in Fig. 2c, the test line develops an intense colour that reflects the high number of AuNP-anti-B12 bound at the test line. This leads a weak control line signal which is indicative of the depleted number of AuNP-anti-B12 reaching the control line, and consequently strong T/C ratios are observed for testing low B12 samples. For the earlier versions of our B12 strips under the same preparation and operating conditions but without the spacer pad incorporation, the T/C ratio remained insensitive to the increase in the sample B12 concentrations up until tens of nmol/L which demonstrates the significance of the spacer pad in the B12 detection in the sub-nmol/L ranges.

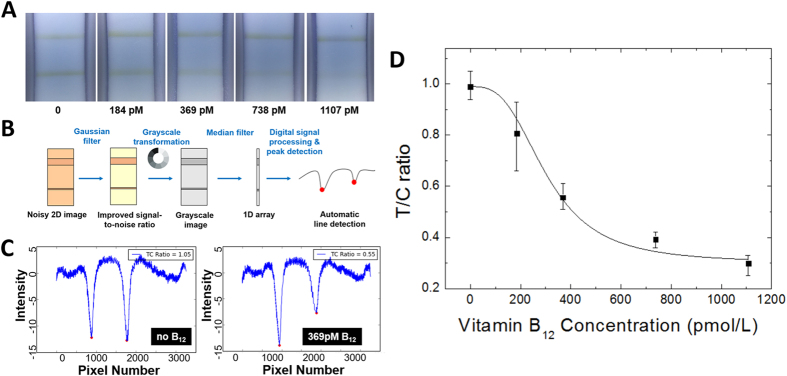

Vitamin B12 quantification in standard solutions

Once the competitive binding of AuNP-anti-B12 conjugates on the test and control lines was performed, the resulting colorimetric signals were silver enhanced and captured by our NutriPhone system. In Fig. 3a, we show the colorimetric change of the test and control lines at different known concentrations of vitamin B12 standards. The captured images were then processed by our NutriPhone app based on the algorithm shown in Fig. 3b. Briefly, a noisy 2D image was filtered and converted to the grayscale, followed by a median filtering to reduce the 2D image into a 1D array which simplified our task to a 1D digital signal processing problem. As shown in in Fig. 3c, the test and control regions of highly concentrated AuNP-anti-B12 were detected as local minima on the grayscale intensity plot, and the respective peak values could be used to calculate T/C ratios. In Fig. 3d we show that T/C ratios can be correlated to the vitamin B12 concentration in the standard solutions. At each concentration, three test strips were used and the maximum lower and upper deviations from the average T/C values were shown. The coefficient of variation of our assay to range from 5.62% at 0 pM of B12 to 16.9% at 184 pM of B12. We then fitted a four-parameter logistic curve such that [B12] = f(T/C). The calibration function was stored and used by the NutriPhone app to predict B12 concentrations from the T/C ratios, where the calibration was performed for each batch of test strips in order to account for the batch-to-batch variations.

Figure 3. NutriPhone image acquisition and processing for vitamin B12 quantification.

(A) Colorimetric variation of the test and control line regions on the silver enhanced B12 lateral flow test strip at different known concentrations of standard vitamin B12 samples (B) image processing algorithm used by our NutriPhone platform (C) Test and control line signals detected by the NutriPhone app as local intensity minima for 0 and 369 pmol/L of B12 standard samples (D) Calibration curve showing the T/C ratios of the colorimetric signals at different standard B12 concentrations: T/C ratio = d + (a–d)/(1+([B12]/c)^b), where a = 0.99, b = 3, c = 303.7, and d = 0.3. Four parameter curve was fitted with R2 = 0.8776. At each concentration 3 strips were used and the maximum and minimum deviation from the average were shown as error bars.

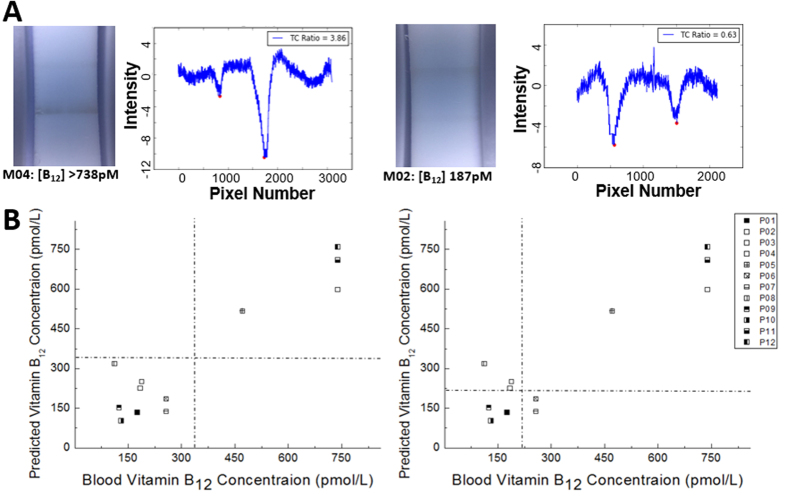

Vitamin B12 deficiency testing using whole blood samples

The performance of our NutriPhone system in POC settings was evaluated by using it to diagnose the vitamin B12 status of human participants. Here, a single finger prick of blood was collected from each of the 12 participants and used as direct inputs to our NutriPhone B12 test strips. In Fig. 4a we show the colorimetric change on the B12 test strips for the two participant samples with sufficient (>738 pmol/L B12) and deficient (186.7 pmol/L B12) levels of vitamin B12. As expected for our competitive B12 strips, the T/C ratio for a deficient B12 case appears to be significantly greater than that for a sufficient B12 case, and this difference could be quantified by our NutriPhone app. Fig. 4b demonstrates the vitamin B12 levels of the 12 participants as predicted by our NutriPhone B12 system based on a calibration curve pre-determined for the tested batch of B12 test strips and compares them to the levels as determined by the laboratory standard method (Chemiluminescence Immunoassay on the IMMULITE 2000 Immunoassay system, Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics, Deerfield , IL). The comparison shows that our system has a median bias of −0.3%, and a high correlation at +0.93 (p < 0.0001). The NutriPhone system in the current state has a cut-off of 332 pmol/L B12, in which it can accurately distinguish eight participants with B12 levels less than 332 pmol/L from the other four participants with B12 levels greater than 332 pmol/L. The current NutriPhone system shows a reduced sensitivity/specificity when lower cut-offs are imposed, however it maintains a high sensitivity and specificity of 87% and 100% respectively using a 258 pmol/L cut-off. The NutriPhone’s performance for other cut-off concentrations can also be found from the Reciever operating characteristic (ROC) curve in Supplementary Fig. S2.

Figure 4. NutriPhone vitamin B12 human trials.

(A) B12 test strip images and the corresponding T/C signals as illustrative results from the human trials (B) Blood vitamin B12 concentrations of 12 human participants as predicted by the NutriPhone system and comparison to the standard method results, where B12 deficiency cut-off was set differently at 332 pmol/L (left) and 221 pmol/L (right).

Discussion

In this paper we have demonstrated a NutriPhone system which allows for the POC determination of vitamin B12 status in under 15 min. This is achieved by developing a competitive-type lateral flow assay for vitamin B12 that incorporates a novel spacer pad and produces colorimetric test/control line signals that can be anlayzed by our system to give quantitative T/C ratios, which can then be correlated with sample vitamin B12 concentrations. We further validate the system in a human trial where it was used to diagnose vitamin B12 status of 12 human participants using a single drop of finger prick blood as the input to the system. Our device can immediately have an impact in some situations that require screening of <369 pmol/L B12 samples and B12 quantification in the higher concentration region35; however we plan to enable better quantification in the future and tune the device to operate with a lower cut-off of 150 pmol/L B12, one of the cut-off points used to diagnose vitamin B12 deficiency24. These results represent a significant step in the development of a POC tool for accurate and rapid quantification of blood vitamin B12 levels, with great potential for deployment in the direct consumers market as well as for clinical and community health care settings in developing countries.

In the near future, the performance of the NutriPhone system for B12 should be further validated by ensuring sufficient number of replicate measurements per test; for the current prototype version of NutriPhone, the reported performance could suffer from bias due to the low numbers of replicate measurements that we performed. Before the validation, our current prototype device can be improved in terms of both performance and usability. Currently, the quantification of B12 levels in the range 0–332 pmol/L of B12 is demonstrated only in standard solutions, whereas the reduced performance in whole blood is likely due to its constituents that interfere with our test’s key binding reaction between the sample B12 and the AuNP-anti-B12. This could be improved by treating our sample pad to include more effective detergents to facilitate the binding interaction, and/or further optimizing the current incubation time after the initial sample application. On the other hand, the limiting step that prevents our vitamin B12 assay from being a complete sample-in-answer-out test is the silver enhancement step which additionally requires the user to apply silver enhancer solutions onto the test strip. For better usability by the end users, the next generation B12 test strips could dry-store the silver enhancing reagents on-chip as has been demonstrated elsewhere36. With these improvements, we hope to extend the human trials in populations with a wider range of B12 status to ensure adequate replicates at the lower end of the physiological and the deficient range of vitamin B12.

Methods

AuNP-anti-B12 conjugate pad preparation

The monoclonal anti-vitamin B12 IgG produced in mouse (CalBioreagents Inc.) came in >95% purity and was conjugated with 40 nm AuNPs using the InnovaCoat Gold Conjugation Kit (Innova Bioscinces Ltd.). Briefly, 0.23 μg AuNP in freeze dried form was mixed with 1 μg anti-vitamin B12 IgG in 0.01 M amine-free phosphate buffer saline (PBS) buffer at pH 7.4. The anti-vitamin B12 IgG attached stably to the surface of AuNP via lysine residues during the 15 min incubation and the reaction was terminated by adding 0.1 M tris-buffered saline (TBS) with 0.1% Tween 20. To remove any excess antibodies, 0.01 M TBS with 0.1% Tween 20 was added in 10 times the volume of the conjugate mixture and was centrifuged at 9000 g for 10 min. Upon removal of the supernatants, the final AuNP-anti-B12 conjugates were reconstituted in 0.01 M TBS containing 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and the final optical density (O.D.) was checked using Spectramax 384 at 530 nm. The conjugates were stored at 4 °C until use.

To prepare the conjugate pads for the B12 assay, the AuNP-anti-B12 conjugates were first diluted to 0.060 O.D. in the conjugate buffer (2 mM borate buffer with 5% sucrose) which contained the preservative and resolubilization agents37. The Glass Fibre Conjugate Pads (EMD Millipore) with 30 cm × 5 mm dimensions were soaked in the diluted conjugate solution for 1 min, followed by drying at 37 °C for 10 h.

Vitamin B12 lateral flow assay preparation

High Flow Plus 180 Membrane Cards (HF180; EMD Millipore) with a 2 mm clear polyester film backing was used as the assay platform, housing the nitrocellulose membrane and the adhesive parts where the conjugate, sample and absorbent pads could be attached. The nitrocellulose portion of HF180 Membrane Cards is 2.5 cm in length and has a nominal capillary flowrate of 45 seconds/cm, which represents the slowest rate offered by the manufacturer and was chosen for our application requiring highly sensitive detection. Before the assembly, the test and control lines were prepared on the nitrocellulose membrane using the Lateral Flow Reagent Dispenser (Claremont Biosolution) to dispense 0.325 mg/ml Vitamin B12-BSA conjugate (CalBioreagents Inc.) and 0.75 mg/ml anti-mouse IgG produced in goat (Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC), respectively. The two lines are separated by 3 mm and uniform line widths of 1 mm could be obtained by operating the Legato 200 Dual Syringe Pump (Claremont Biosolution) at 6.4 μl/min. The membrane cards were subsequently dried for 2 h at 37 °C, then at room temperature overnight. The B12 lateral flow assay was assembled into its final form shown in Fig. 1a by first attaching the spacer pad (i.e. untreated Glass Fibre Conjugate Pads with 30 cm × 5 mm dimensions) to the adhesive region of the assay platform below the nitrocellulose membrane with an overlap of 0.5 mm. The AuNP-anti-B12 treated conjugate pad was then attached below the spacer pad with 0.5 mm overlap. The FR-1 Membrane (035; MDI Membrane Technologies) with 30 cm × 13.5 mm dimensions was then attached below the AuNP-anti-B12 conjugate pad with the 2 mm overlap to serve as the sample pad of the assay. The FR-1 membrane has a thickness of 0.35 mm and whole blood holding capacity of 30 μl/cm2. Notably the 5 mm length of the spacer pad was such that the gap created between the nitrocellulose membrane and the conjugate pad is sufficiently long to prevent the sample—AuNP–anti-B12 mixture from entering the nitrocellulose membrane at the initial 40 μl sample application. While the 5 mm length can be increased and retain the proper function of the spacer pad, this would necessarily decrease the length of the FR-1 membrane (where the total available length below the nitrocellulose was set by the HF180 platform’s backing length of 20 mm) and thereby decrease the blood holding capacity for the test. As done for the commercial rapid diagnostic tests, a specialized covertape (Kenosha C.V.) with arrows printed to indicate the sample input location, was attached on the top of these membranes and ensured proper contact between the membranes during the sample flow. The Cellulose Fibre Sample Pad (EMD Millipore) was attached above the nitrocellulose membrane with the 2 mm overlap to serve as the absorbent pad of the assay. The assembled assay was cut into individual strips of 4 mm width using a rotary paper trimmer (Dahle). The strips were then kept sealed in a plastic container to prevent contamination from dirt/dust, at room temperature. Also, silica gel desiccants (Dry-Packs™) were added for moisture control, where condensing water vapour could displace the immobilized agents on the nitrocellulose and/or negatively affect the AuNP–anti B12 conjugate stability by causing sugar complexes to form37,38. Storage up to 4 weeks without loss in strip performance has been observed, however longer storage times of up to one year have been widely used for similar, commercial strips (e.g. strips from AccuBioTech Co., Ltd) that use additional control measures (e.g. lamination of pads and membranes) and proprietary additives for lengthened reagent stability.

NutriPhone test strip protocol and human trials

In a NutriPhone test for vitamin B12 deficiency, the use of capillary tubes and dropper bottles allows the users to apply appropriate amounts of key reagents in POC settings. First, vitamin B12 samples (Abcam) in the range from 0 to 1107 pmol/L were prepared in standard 1x PBS buffer solutions. To initiate the B12 assay, the user collects the sample up to an indicated line on the capillary tube (~40 μl) and dispenses it fully onto the test inlet. This is followed by applying 2 droplets (~40 μl) of the chase buffer (1x TBS with 1% BSA, 1.5% Tween20, 0.1% sodium azide) from the dropper bottle. The addition of the chase buffer allows the sample to fully wet the conjugate pad and begin the sample B12 interaction with AuNP-anti-B12, while the presence of the spacer pad prevents the sample from entering the nitrocellulose membrane. After waiting for 4 min, the user adds additional 4 droplets (~80 μl) of chase buffer to allow the sample to proceed beyond the spacer pad and complete the flow through the assay by being collected at the absorbent pad upstream. The initial colorimetric signal develops in the subsequent 6 min at which point the user applies a droplet (~20 μl) each from the silver enhancers A and B (Ted Pella Inc.) directly on the test/control regions on the nitrocellulose membrane. The NutriPhone app automatically takes a test strip image after waiting for an additional 3 min for amplification of the initial colorimetric signal, and computes a T/C ratio. Here, using a stop solution to quench the silver enhancement reaction is a viable option, however it would represent an additional step in our testing procedures which is undesirable for the intended point-of-care applications. We therefore did not use a stop solution, and instead computed T/C ratios from the images taken at the same time point. Throughout the procedures, the NutriPhone app incorporates the step-by-step instructions and timers to prevent its users from the common operation errors.

Our human trials were approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Subjects at Cornell University, and carried out in accordance with their guidelines and regulations. The informed consent was obtained from all participants. In the trials, the participants were finger-pricked for a drop of blood (~40 μL) which was collected using a capillary tube and dispensed onto the inlet of the B12 test strip for carrying out the NutriPhone B12 test as described in the protocol above. A trained and certified phlebotomist then drew ~5 mL of blood via venipuncture. Following 1 hour incubation at room temperature, serum was separated from whole venous blood by centrifugation at 2000 rpm for 10 min. Serum vitamin B12 was measured by chemiluminescence immunoassay on the Immulite 2000 platform (Siemens Healthcare Laboratory Diagnostics). The Siemens vitamin B12 kit reports normal reference values between 142–724 pmol/L with a lower limit of detection at 92 pmol/L.

NuriPhone app and image processing

The majority of the iOS app was written in Objective-C. The image processing algorithm was written in pure C to improve speed and performance. There were no major 3rd party libraries used in the final version of the app; everything was either the default iOS libraries, or written by the authors. After an image was captured by the NutriPhone app, a series of image processing steps as shown in Fig. 3b were performed to improve the limit of detection and accuracy over the conventional visual inspection. First, a 3 × 3 Gaussian filter was applied to the raw image to smooth out some of the noise. The image was then converted to the grayscale, so that the grayscale intensity could be used as a single-channel measurement that distinguishes the background from the colorimetric lines. The grayscale intensity of the coloured control and test lines are lower than the hue of the background, so that the presence of a line could be detected by finding a local minimum in the hue data. After the grayscale conversion, the 2D image was reduced to a 1D array by replacing each row in the 2D image with the median hue value along that row. The median filtering reduces the noise, and the lower dimensionality reduces the process of peak detection to a 1D digital signal processing problem. The local minima corresponding to the test and control lines were located by stepping through the 1D array and storing all points which are at least 10 intensity values below the last inflection point on both sides. The values of local minima were then compared to yield T/C ratios, which were lastly converted into vitamin B12 concentrations based on the pre-determined calibration curve, [B12] = f(T/C).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Lee, S. et al. NutriPhone: a mobile platform for low-cost point-of-care quantification of vitamin B12 concentrations. Sci. Rep. 6, 28237; doi: 10.1038/srep28237 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

D.E. and S.M. acknowledge funding from the National Science Foundation through grant IIP-1430092. In addition, S.L. acknowledges the support of the National Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) through a Postgraduate scholarship. S.L would like to thank Aadhar Jain and Elizabeth Rey for the helpful discussions on the assay development. The authors also thank Erica Bender for performing finger pricks and venipunctures in human trials, and Vicky Simon for running the Immulite system in the Human Metabolic Research Unit in the Division of Nutritional Sciences. The optical density measurement described in this paper was performed in the Nanobiotechnology Center at Cornell University (NBTC).

Footnotes

Author Contributions S.L., S.M. and D.E. designed the study. S.L. developed the NutriPhone test strips. S.L., D.O. and J.H. developed the NutriPhone accessory. D.O. and J.H. developed the NutriPhone app. S.L. and D.O. ran the NutriPhone tests and anlayzed the data. S.C. assisted in running the laboratory standard tests. All co-authors contributed to writing and edited the paper. D.E. and S.M. are principal investigators on the NSF grant that resulted in this work and supervised all aspects of the study.

References

- Allen R. H., Stabler S. P., Savage D. G. & Lindenbaum J. Metabolic abnormalities in cobalamin (vitamin B12) and folate deficiency. FASEB J. 7, 1344–1353, doi: 10.1096/fj.1530-6860 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baik H. & Russell R. Vitamin B12 deficiency in the elderly. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 19, 357–377, doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.19.1.357 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dror D. K. & Allen L. H. Effect of vitamin B12 deficiency on neurodevelopment in infants: current knowledge and possible mechanisms. Nutr. Rev. 66, 250–255, doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00031.x (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenech M. The role of folic acid and vitamin B12 in genomic stability of human cells. Mutat Res-Fund Mol M 475, 57–67, doi: 10.1016/S0027-5107(01)00079-3 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall C. A. Function of vitamin B12 in the central nervous system as revealed by congenital defects. Am. J. Hematol. 34, 121–127, doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830340208 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stabler S. P. Vitamin B12 Deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 368, 149–160, doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1113996 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh R. & Brown D. L. Vitamin B12 deficiency. Am. Fam. Physician 67, 979–986, doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031155 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stabler S. P. & Allen R. H. Vitamin B12 deficiency as a worldwide problem. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 24, 299–326, doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.24.012003.132440 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wokes F., Badenoch J. & Sinclair H. Human dietary deficiency of vitamin B12. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 3, 375–382 (1955). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore E. et al. Cognitive impairment and vitamin B12: a review. Int. Psychogeriatr. 24, 541–556, doi: 10.1017/S1041610211002511 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein J. L., Layden A. J. & Stover P. J. Vitamin B-12 and Perinatal Health. Adv Nutr. 6, 552–563, doi: 10.3945/an.115.008201 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeuschner C. L. et al. Vitamin B12 and vegetarian diets. Med. J. Aust. 199, S27–32, doi: 10.5694/mjao11.11509 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak R., Parrott S. J., Raj S., Cullum-Dugan D. & Lucus D. How prevalent is vitamin B(12) deficiency among vegetarians? Nutr. Rev. 71, 110–117, doi: 10.1111/nure.12001 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane M. G., Sample C., Patchett S. & Register U. Vitamin B12 Studies in Toal Vegetarians (Vegans). J of Nutri. Med. 4, 419–430, doi: 10.3109/13590849409003591 (1994). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yajnik C. et al. Vitamin B12 deficiency and hyperhomocysteinemia in rural and urban Indians. JAPI 54, 775–782 (2006). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak R., Lester S. E. & Babatunde T. The prevalence of cobalamin deficiency among vegetarians assessed by serum vitamin B12: a review of literature. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 68, 541–548, doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2014.46 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Oncescu V., Mancuso M., Mehta S. & Erickson D. A smartphone platform for the quantification of vitamin D levels. Lab Chip 14, 1437–1442, doi: 10.1039/c3lc51375k (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blacksell S. D. Commercial dengue rapid diagnostic tests for point-of-care application: recent evaluations and future needs? BioMed Res. Int. 2012, 1–12, doi: 10.1155/2012/151967 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackowska T., Grzelczyk-Wielgorska M. & Pawlik K. Rapid Test for Influenza in Diagnostics. Vol. 756 (eds Mieczyslaw Pokorski) Ch. 33, 263–269 (Springer: Netherlands, , 2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Malaria rapid diagnostic test performance: results of WHO product testing of malaria RDTs: round 5 (2014)(Date of access:03/14/2016).

- Allin K. H. & Nordestgaard B. G. Elevated C-reactive protein in the diagnosis, prognosis, and cause of cancer. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 48, 155–170, doi: 10.3109/10408363.2011.599831 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner T. A., Gravett C. A., Gravett M. G. & Rubens C. E. A global health opportunity: The potential of multiplexed diagnostics in low-resource settings. J Glob Health 1, 138 (2011). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monno R. et al. Evaluation of a rapid test for the diagnosis of pneumococcal pneumonia. J. Microbiol. Methods 92, 127–131, doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2012.11.011 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malouf R. & Areosa Sastre A. Vitamin B12 for cognition. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3, Cd004326, doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd004326 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lips P. Worldwide status of vitamin D nutrition. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. 121, 297–300, doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.02.021 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posthuma-Trumpie G. A., Korf J. & Amerongen A. Lateral flow (immuno)assay: its strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats. A literature survey. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 393, 569–582, doi: 10.1007/s00216-008-2287-2 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng S. et al. Immunochromatographic Diagnostic Test Analysis Using Google Glass. ACS Nano 8, 3069–3079, doi: 10.1021/nn500614k (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg B. et al. Cellphone-Based Hand-Held Microplate Reader for Point-of-Care Testing of Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays. ACS nano 9, 7857–7866, doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b03203 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallegos D. et al. Label-free biodetection using a smartphone. Lab Chip 13, 2124–2132, doi: 10.1039/C3LC40991K (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oncescu V., Mancuso M. & Erickson D. Cholesterol testing on a smartphone. Lab Chip 14, 759–763, doi: 10.1039/C3LC51194D (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson D. et al. Smartphone technology can be transformative to the deployment of lab-on-chip diagnostics. Lab Chip 14, 3159–3164, doi: 10.1039/c4lc00142g (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anfossi L., Di Nardo F., Giovannoli C., Passini C. & Baggiani C. Increased sensitivity of lateral flow immunoassay for ochratoxin A through silver enhancement. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 405, 9859–9867, doi: 10.1007/s00216-013-7428-6 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu E. et al. Modeling of a Competitive Microfluidic Heterogeneous Immunoassay: Sensitivity of the Assay Response to Varying System Parameters. Anal. Chem. 81, 3407–3413, doi: 10.1021/ac802672v (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradelles P., Grassi J., Creminon C., Boutten B. & Mamas S. Immunometric assay of low molecular weight haptens containing primary amino groups. Anal. Chem. 66, 16–22, doi: 10.1021/ac00073a005 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travica N., Ried K., Bujnowski R. & Sali A. Integrative health check reveals suboptimal levels in a number of vital biomarkers. AIMED, 1–6, doi: 10.1016/j.aimed.2015.11.002 (2015). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cho I.-H., Seo S.-M., Paek E.-H. & Paek S.-H. Immunogold–silver staining-on-a-chip biosensor based on cross-flow chromatography. J. Chromatogr. B 878, 271–277, doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.07.016 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millipore E. Rapid Lateral Flow Test Strips: Considerations for Product Development, (Date of access:02/18/2016) (2008).

- Mansfield M. A. Lateral Flow Immunoassay. Vol. 1 (eds Raphael Wong & Harley Tse) Ch. 6, 101–102 (Springer, 2009). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.