Abstract

Argyrophilic grain disease (AGD) is a frequent late-onset, 4-repeat tauopathy reported in Caucasians with high educational attainment. Little is known about AGD in non-Caucasians or in those with low educational attainment. We describe AGD demographics, clinical, and neuropathological features in a multiethnic cohort of 983 subjects ≥50 years of age from São Paulo, Brazil. Clinical data were collected through semistructured interviews with an informant and included in the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly, the Clinical Dementia Rating, and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. Neuropathologic assessment relied on internationally accepted criteria. AGD was frequent (15.2%) and was the only neuropathological diagnosis in 8.9% of all cases (mean, 78.9 ± 9.4 years); it rarely occurred as an isolated neuropathological finding. AGD was associated with older age, lower socioeconomic status (SES), and appetite disorders. This is the first study of demographic, clinical, and neuropathological aspects of AGD in different ethnicities and subjects from all socioeconomic strata. The results suggest that prospective studies of AGD patients include levels of hormones related to appetite control as possible antemortem markers. Moreover, understanding the mechanisms behind higher susceptibility to AGD of low SES subjects may disclose novel environmental risk factors for AGD and other neurodegenerative diseases.

Keywords: Dementia, Neurodegeneration, Neuropathology, Postmortem, Tauopathy

INTRODUCTION

Argyrophilic grain disease (AGD) is an age-related 4-repeat tauopathy, first described as a novel neuropathological entity in 1987 (1, 2). AGD affects both genders equally and shows an age-related increase in prevalence varying from about 9.3% in patients 65 years old to 31.3% in centenarians (3–7). Thus, in subjects of European descent, AGD is the second most common neurodegenerative disease after Alzheimer disease (AD) (5, 8). AGD often overlaps with other neurodegenerative diseases, including AD, Pick disease, tangle-only dementia, progressive supranuclear palsy, corticobasal degeneration, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, Parkinson disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, and TDP-43 proteinopathies (3, 4, 9–13).

The high degree of overlapping between AD-type pathology and AGD lead to the speculation that AGD is a part of the AD spectrum. Recently, however, studies showing distinct AGD characteristics such as a lack of acetylated tau have indicated that AGD is an independent entity (6, 14–21). AGD is characterized by 3 principal neuropathological hallmarks, all of which contain phospho-tau: (1) argyrophilic grains, (2) oligodendrocytic coiled bodies, and (3) neuronal intracytoplasmic pretangles. Associated changes include balloon neurons and phospho-tau positive bush-like astrocytes (1, 9, 22–25). Although AGD remains a predominantly sporadic disease, recent studies described 2 rare microtubule-associated protein tau gene mutations (MAPT S305I and S305S) causing pathological features consistent with AGD in individuals with memory decline and behavioral changes (26, 27). Furthermore, AGD is associated with DNA copy number variations at 17p13.2 (28).

An early study suggested an increased risk of AGD in individuals with apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε2 allele, but further studies failed to confirm this relationship (29–31). The lack of distinctive antemortem features makes AGD virtually unknown to clinicians (9, 20). Clinicopathological studies suggest that AGD manifests mainly as very slowly progressive amnestic mild cognitive impairment, similar to early AD stages (32–34). In rare instances, AGD changes spread beyond their usual limbic localization and the disease presents as a behavioral-variant frontotemporal dementia (34–36). Intriguingly, AGD has been found in up to 31% of cognitively normal individuals, leading to the speculation that AGD is rather a benign condition. (37–39). On the other hand, AGD subjects show neuropsychiatric symptoms including personality changes and emotional instability failure more frequently than age-matched controls, probably reflecting the prominent involvement of the limbic system (3, 9, 40–44).

Although they are comprehensive, all these studies on AGD relied mostly on highly educated Caucasians. Little is known about AGD in other ethnicities, subjects with low school attainment, or low socioeconomic status (SES). Here, we describe AGD demographics, clinical, and neuropathological features in a large multiethnic, population-based postmortem sample.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

The participants belonged to the Brain Bank of the Brazilian Aging Brain Study Group (BBBABSG) from the University of São Paulo, Brazil. The BBBABSG receives brain donations from individuals who die in the metropolitan area of São Paulo (11 million inhabitants) and receive an autopsy in the São Paulo Autopsy Service (45). From February 2004 to March 2014, 983 brain bank donors received a complete clinicopathological workup and were included in this study. This study was approved by the University of São Paulo ethical committee and written informed consent for brain donation and provision of clinical information was obtained from the next of kin (46).

Clinical Evaluation

Trained gerontologists obtained clinical data from a knowledgeable informant who had at least weekly contact with the subject over the 6 months preceding death using a semistructured interview (46). This interview included information about demographics, cardiovascular risk factors, SES, and validated questionnaires covering multiple cognitive domains. SES was categorized using a validated Brazilian scale that grouped subjects into 5 categories (A–E) (47). SES categories were then grouped as high (A/B), middle (C), and low (D/E). The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale (informant section only) and the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE) were used to determine the patients’ cognitive function before death (48, 49). Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia were assessed using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) (50). We analyzed the NPI both as a total score and as individual scores for each item (ie, delusions, hallucinations, agitation, dysphoria, anxiety, apathy, irritability, euphoria, disinhibition, aberrant motor behavior, night-time disturbances, and appetite and eating abnormalities).

APOE Genotyping

Genomic DNA was extracted from blood samples in a subset of the cases. APOE genotyping was performed using real-time polymerase chain reaction assay, as described by Calero et al (51).

Neuropathological Assessment

Brain procurement was performed within 20 hours of death. One hemisphere was fixed in 4% buffered paraformaldehyde and the other hemisphere was coronally sectioned and snap frozen. Samples from the fixed hemisphere were processed and embedded in paraffin. Samples were from the following areas: middle frontal gyrus, middle and superior temporal gyri, angular gyrus, superior anterior cingulate gyrus, visual cortex, hippocampal formation at the level of lateral geniculate body, amygdala, basal ganglia at the level of the anterior commissure, thalamus, midbrain, pons, medulla oblongata, and cerebellum. All sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and selected sections were immunostained with antibodies against β-amyloid (4G8, 1:10,000; Signet Pathology Systems, Dedham, MA), phosphorylated tau (PHF-1, 1:2,000; gift from Peter Davies, NY), transactivation response DNA-binding protein of 43 kDa (TDP-43, 1:500; Proteintech, Chicago, IL), and α-synuclein (EQV-1, 1:10,000; gift from Kenji Ueda, Tokyo, Japan), as previously described (45). Internationally accepted neuropathological criteria and guidelines were used for diagnosing and staging (52–54).

AD-type pathology was scored using the Braak and Braak staging system, the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) criteria and the Thal et al phase system for β-amyloid plaques (55). A neuropathological diagnosis of AD was granted to individuals showing, at least, intermediate AD neuropathologic changes (52). Diagnosis of AGD required: the presence of abundant phosphorylated tau-positive grains in the CA1 sector of the hippocampus; pre-tangles, especially in the hippocampal CA2 sector; and oligodendrocytes with coiled bodies in the hippocampal/temporal white matter; regardless of the presence of other neurodegenerative disease-related lesions (9, 56–58).

Cerebrovascular lesions were analyzed on gross examination and using H&E-stained histological slides in all of the sampled areas. The presence of small vessel disease, lacunae, and large infarcts was registered by topography, size, and number. Small vessel disease diagnosis required widespread and at least moderately severe microvascular changes in 3 cortical regions. A diagnosis of vascular dementia was made in subjects with either 1 large (>1 cm) chronic infarct or 3 lacunae in any of the following strategic areas: thalamus, frontocingular cortex, basal forebrain and caudate, medial temporal area, or angular gyrus (59).

Statistical Analysis

First, we divided the cases into 2 groups according to the presence of AGD (AGD and non-AGD). Table 1 depicts sociodemographics, clinicofunctional and neuropathological variables, and APOE genotype for these 2 groups. Subsequently, we divided the AGD group into “pure” and “mixed” (AGD plus another neurodegenerative disease or AGD plus vascular dementia). Table 2 depicts sociodemographics, clinicofunctional and neuropathological variables, and APOE genotype for these 2 subgroups. Finally, we compared pure-AGD to pure-AD subjects.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the Sample by AGD Status (n = 983)

| Variables | Non-AGD (n = 831) | AGD (n = 152) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic features | |||

| Age, mean (SD) | 73.1 (11.9) | 78.9 (9.4) | <0.001* |

| Female, n (%) | 417 (50.2) | 93 (61.2) | 0.01¥ |

| Race | |||

| White | 575 (69.3) | 108 (71.1) | 0.44£ |

| Black | 88 (10.6) | 19 (12.5) | |

| Brown | 153 (18.4) | 21 (13.8) | |

| Asian | 14 (1.7) | 4 (2.6) | |

| Years of schooling, mean (SD) | 4.3 (3.8) | 3.6 (3.3) | 0.02* |

| SES, n (%) | |||

| High | 214 (25.9) | 27 (17.9) | <0.001¥ |

| Middle | 348 (42.1) | 45 (29.8) | |

| Low | 264 (32.0) | 79 (52.3) | |

| APOE, n (%) | |||

| ϵ2 | 38 (12.3) | 4 (7.0) | |

| ϵ3 | 177 (56.7) | 39 (67.2) | 0.27£ |

| ϵ4 | 97 (31.1) | 15 (25.9) | |

| Cardiovascular risk factors, n (%) | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 229 (28.2) | 43 (28.9) | 0.87¥ |

| Hypertension | 521 (64.2) | 102 (68.5) | 0.31¥ |

| Dyslipidemia | 75 (9.2) | 15 (10.1) | 0.75¥ |

| Smoking | 219 (27.0) | 33 (22.1) | 0.44¥ |

| Alcohol use | 138 (17.0) | 19 (13.0) | 0.48¥ |

| Stroke | 123 (17.2) | 16 (14.5) | 0.48¥ |

| Cognitive, behavioral/psychological, and functional evaluations | |||

| IQCODE, mean (SD) | 3.4 (0.7) | 3.4 (0.6) | 0.63* |

| CDR sum of boxes, mean (SD) | 4 (6.4) | 4 (6.2) | 0.90* |

| CDR | |||

| No impairment, n (%) | 487 (58.6) | 89 (58.6) | 0.90¥ |

| Impairment, n (%) | 344 (41.4) | 63 (41.4) | |

| NPI, n (%) | 536 (64.7) | 106 (69.7) | 0.22¥ |

| NPI symptoms | |||

| Delusions, n (%) | 85 (10.3) | 11 (7.2) | 0.24¥ |

| Hallucinations, n (%) | 125 (15.1) | 14 (9.2) | 0.056¥ |

| Depression, n (%) | 199 (24.0) | 25.7 (39.0) | 0.66¥ |

| Anxiety, n (%) | 198 (23.9) | 38 (25.2) | 0.73¥ |

| Agitation/aggression, n (%) | 176 (21.3) | 24 (15.8) | 0.12¥ |

| Euphoria, n (%) | 29 (3.5) | 3 (2.0) | 0.24£ |

| Disinhibition, n (%) | 70 (8.4) | 9 (5.9) | 0.29¥ |

| Irritability/lability, n (%) | 143 (17.2) | 21 (13.8) | 0.29¥ |

| Apathy, n (%) | 166 (20.0) | 26 (17.1) | 0.40¥ |

| Aberrant motor activity, n (%) | 72 (8.7) | 13 (8.6) | 0.95¥ |

| Nighttime behaviors, n (%) | 193 (23.3) | 36 (23.7) | 0.92¥ |

| Appetite/eating changes, n (%) | 249 (30.0) | 62 (40.8) | 0.009¥ |

| Neuropathological lesions | |||

| Braak, n (%) | <0.001¥ | ||

| 0–II | 568 (68.8) | 60 (41.4) | |

| III–VI | 258 (31.2) | 85 (58.6) | |

| CERAD, n (%) | 0.22¥ | ||

| None/sparse | 630 (75.9) | 108 (71.1) | |

| Moderate/frequent | 200 (24.1) | 44 (28.9) | |

| Lacunar infarct, n (%) | 100 (12.2) | 18 (11.9) | 0.93¥ |

| Hyaline arteriolosclerosis, n (%) | 131 (15.8) | 17 (11.3) | 0.15¥ |

| Lewy-type pathology, n (%) | 83 (10.2) | 17 (11.3) | 0.70¥ |

AGD, argyrophilic grain disease; APOE, apolipoprotein E; CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating; CERAD, Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease; IQCODE, Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly; NPI, Neuropsychiatric Inventory; SD, standard deviation; SES, socioeconomic status.

£Fisher exact test.

¥Pearson chi-square.

*Student t test.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of the AGD Sample According the Presence of Concomitant Neuropathological Diagnosis

| Variables | Pure-AGD (n = 87) | Mixed-AGD (n = 65) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic features | |||

| Age, mean (SD) | 76.5 (9.8) | 82.1 (7.8) | <0.001* |

| Female, n (%) | 50 (57.0) | 43 (66.2) | 0.27£ |

| Race | |||

| White | 58 (66.7) | 50 (76.9) | 0.23¥ |

| Black | 10 (11.5) | 9 (13.8) | |

| Brown | 16 (18.4) | 5 (7.7) | |

| Asian | 3 (3.4) | 1 (1.5) | |

| Years of schooling, mean (SD) | 3.9 (3.6) | 3,17 (2.8) | 0.13* |

| SES, n (%) | |||

| High | 12 (14.0) | 15 (23.1) | 0.35¥ |

| Middle | 27 (31.4) | 18 (27.7) | |

| Low | 47 (54.7) | 32 (49.2) | |

| APOE, n (%) | |||

| ε2 | 3 (11.5) | 1 (3.2) | 0.46£ |

| ε3 | 16 (61.5) | 23 (71.9) | |

| ε4 | 7 (26.9) | 8 (25.0) | |

| Cardiovascular risk factors, n (%) | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 14 (22.2) | 29 (33.7) | 0.12¥ |

| Hypertension | 59 (68.6) | 43 (68.3) | 0.96¥ |

| Dyslipidemia | 5 (7.9) | 10 (11.6) | 0.45¥ |

| Smoking | 22 (25.6) | 11 (17.5) | 0.37¥ |

| Alcohol use | 11 (13.3) | 8 (12.7) | 0.42¥ |

| Stroke | 7 (14.9) | 9 (14.3) | 0.92¥ |

| Cognitive, behavioral/psychological, and functional evaluations | |||

| IQCODE, mean (SD) | 3.2 (0.4) | 3.67 (0.7) | <0.001* |

| CDR sum of boxes, mean (SD) | 2.1 (4.7) | 6.4 (7.1) | <0.001* |

| CDR | |||

| No impairment, n (%) | 65 (74.7) | 24 (36.9) | <0.001¥ |

| Impairment, n (%) | 22 (25.3) | 41 (63.1) | |

| NPI, n (%) | 55 (63.2) | 51 (78.5) | 0.04¥ |

| NPI symptoms | |||

| Delusions, n (%) | 3 (3.4) | 8 (12.3) | 0.04£ |

| Hallucinations, n (%) | 4 (4.6) | 10 (15.4) | 0.02£ |

| Depression, n (%) | 21 (24.1) | 18 (27.7) | 0.62¥ |

| Anxiety, n (%) | 20 (23.0) | 18 (28.1) | 0.47¥ |

| Agitation/aggression, n (%) | 13 (14.9) | 11 (16.9) | 0.74¥ |

| Euphoria, n (%) | 2 (2.3) | 1 (1.6) | 0.61£ |

| Disinhibition, n (%) | 3 (3.4) | 6 (9.2) | 0.12£ |

| Irritability/lability, n (%) | 13 (14.9) | 8 (12.3) | 0.64¥ |

| Apathy, n (%) | 12 (13.8) | 14 (21.5) | 0.21¥ |

| Aberrant motor activity, n (%) | 4 (4.6) | 9 (13.8) | 0.04£ |

| Nighttime behaviors, n (%) | 20 (23.0) | 16 (24.6) | 0.81¥ |

| Appetite/eating changes, n (%) | 34 (39.1) | 28 (43.1) | 0.62¥ |

| Neuropathological lesions | |||

| Braak, n (%) | <0.001¥ | ||

| 0–II | 47 (57.3) | 13 (20.6) | |

| III–VI | 35 (42.7) | 50 (79.4) | |

| CERAD, n (%) | <0.001£ | ||

| None/sparse | 85 (97.7) | 23 (35.4) | |

| Moderate/frequent | 2 (2.3) | 42 (64.6) | |

| Lacunar infarct, n (%) | 3 (3.4) | 16 (25.0) | <0.001£ |

| Hyaline arteriolosclerosis, n (%) | 6 (6.9) | 11 (17.2) | 0.05¥ |

| Lewy-type pathology, n (%) | 1 (1.1) | 16 (25.0) | <0.001£ |

AGD, argyrophilic grain disease; APOE, apolipoprotein E; CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating; CERAD, Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease; IQCODE, Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly; NPI, Neuropsychiatric Inventory; SD, standard deviation; SES, socioeconomic status.

£Fisher exact test.

¥Pearson chi-square.

*Student t test.

For the analysis, we dichotomized some of the variables. Subjects with a CDR = 0 (48) were rated as cognitively normal, whereas a CDR > 0 resulted in the designation of cognitive impairment. The NPI curves were skewed to 0 because of the large number of controls in this series; therefore, NPI score was considered positive if ≥ 1. APOE allele frequencies were counted considering the number of times that each allele was present in each individual. Out of the neuropathological variables, cases were grouped as Braak AD stages 0–II and III–VI. For the CERAD score, cases were grouped into absent/sparse or moderate/frequent groups.

Chi-square or Fisher exact tests were used to analyze categorical variables, and unpaired t-tests were used for continuous ones. Variables that were associated with AGD in univariate analyses (ie, age, sex, education attainment, and SES) were included in a multiple logistic regression model to investigate their independent association with AGD. The level of statistical significance was set at 5%. The statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

In the 983 patients, the mean age at death was 74.0 ± 11.7 years; 52% were female; the mean education was 4.2 ± 3.7 years; and 30% were cognitively impaired (CDR > 0).

AGD Versus Non-AGD

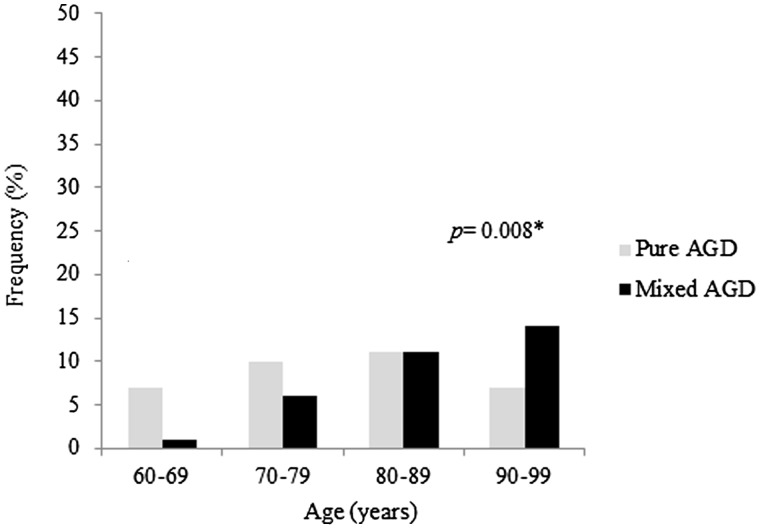

AGD was identified in 15.2% of the sample; it was the third most common neuropathological diagnosis after AD (23%) and vascular dementia (16%). The prevalence of AGD with or without concomitant neurodegenerative disease increased considerably with older age (Fig. 1). Only 3 subjects were younger than 60 years. Participants with AGD were significantly older, more likely to be female, had fewer years of education, and lower SES (Table 1). However, after including age, sex, education, and SES in a multiple logistic regression analysis, AGD was only associated with age (odds ratio [OR]=1.05; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.03–1.07; p < 0.0001) and SES (OR = 1.80; 95% CI = 1.39–2.32; p < 0.0001). Finally, there was no difference in race, cognitive status, or frequency of cerebrovascular risk factors between non-AGD and AGD groups. APOE genotype was available for 368 participants (Table 1); no association between AGD and APOE genotyping was found. In the non-AGD group, subjects with an APOE ε4 showed a higher burden of AD-type hallmarks (neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic plaques) and cerebral amyloid angiopathy (Supplementary Table 1).

FIGURE 1.

Frequency of AGD cases in different age groups in pure-AGD and mixed-AGD subjects. AGD, argyrophilic grain disease.

Some degree of behavioral and psychological manifestations (NPI ≥ 1) was observed in 70% of AGD subjects (Table 1). Appetite changes were more frequent in the AGD group. Among the 62 AGD subjects with appetite changes according to the NPI, the severity of the symptom was moderate to severe in 79%. Hallucinations tended to be more frequent in the non-AGD group, but the results did not reach statistical significance.

Concerning neuropathological parameters, the AGD group had a higher proportion of subjects with moderate to high Braak stages. The neuritic plaques burden, presence of lacunar infarcts, arteriolosclerosis, and Lewy-type pathology were similar between AGD and non-AGD groups (Table 1). Hippocampal sclerosis was present in only a few cases (3% of the series) and was not included in this analysis. In 5% (8/152) of participants in the AGD group, no other neuropathologic changes were identified, including a total absence of neurofibrillary tangles (Braak 0) and senile plaques. Four of these 8 participants showed cognitive impairment: 2 with a CDR = 0.5, 1 with CDR = 1, and 1 with CDR = 3.

Pure-AGD Versus Mixed-AGD

Out of the 65 subjects with mixed-AGD, over half (n = 34) also had AD. Vascular dementia was found in 16 subjects and Lewy body disease in 12. Mixed-AGD subjects were significantly older (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). There was no difference in sex, race, years of schooling, SES, frequencies of cerebrovascular risk factors, and APOE genotyping between pure- and mixed-AGD (Table 2).

There was a higher rate of cognitively normal subjects in pure-AGD (75%) compared to the mixed group (37%). Indeed, dementia (CDR ≥ 1) was found in only 10% of pure-AGD compared to almost 48% in mixed-AGD (p < 0.001).

Behavioral and psychological symptoms were frequently observed independently of the presence of a concomitant neurodegenerative disease (Table 2) or cognitive impairment (Supplementary Fig. 1). Behavioral and psychological symptoms were found in 55% of pure-AGD subjects without cognitive impairment (CDR = 0) and 63% of AGD with only mild neurofibrillary pathology (Braak stage I–II). Delusions, hallucinations, and aberrant motor activities were more frequent in the mixed-AGD group (Supplementary Fig. 1). We did not find differences in appetite/eating changes between pure- and mixed-AGD.

By definition, pure-AGD was more likely to have a low burden of neurofibrillary pathology (57%) than mixed-AGD (20%) (p < 0.001).

Pure-AGD Versus Pure-AD

As predicted, pure-AGD subjects were younger, had a lower proportion of APOE ε4 allele, and better functional scores (according to the IQCODE and CDR) than pure-AD subjects. Surprisingly, pure-AGD subjects belonged to a lower SES. Regarding behavioral and psychological symptoms, pure-AGD subjects were less prone to show delusions, hallucinations, agitation, disinhibition, irritability, and aberrant motor activity (Supplementary Table 2). The frequency of appetite disorders was similar in pure-AGD and pure-AD subjects.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we analyzed 983 subjects from a multiethnic population-based clinicopathological series to investigate possible distinctive demographics and clinical aspects associated with AGD. As novel findings, we identified that AGD is associated with a lower SES and equally affects Caucasians, Africans, and Asians. We also found a correlation between AGD and appetite disorders measured by the NPI.

This study corroborates findings from other series of unselected subjects. AGD prevalence is high, second only to AD among the neurodegenerative diseases. AGD is associated with older age and affects both genders equally (3, 9, 34, 58). In fact, since advanced age is also a risk factor for other neurodegenerative diseases, it is not surprising that the average age in the mixed-AGD group was higher than in the pure-AGD group.

The prevalence of AGD in the current series (15.2%) is slightly higher than in other studies (3, 4, 9, 34, 41, 58) except Josephs et al, who identified AGD in 16% of 359 autopsy cases from a dementia clinic (age range 74–101 years) (20). Tolnay et al found AGD in 9% of 301 consecutive autopsies of individuals over 65 years old (age range 67–100 years) from a hospital series (39). Using silver staining, a method less sensitive than immunohistochemistry, Braak and Braak found an AGD prevalence of 5% among 2,261 non-selected autopsies (age range 25–96 years) from a general hospital (3). Saito et al reported AGD in 4% of 1,241 serial autopsy cases (age range 48–104 years) from a geriatric hospital (58). Martinez-Lage and Munoz observed that the prevalence of AGD was 6% in 300 unselected consecutive autopsies of patients older than 30 years (no age range provided), but 12% in those older than 65 years, reaching 31% in centenarians (4). It is plausible that improvements on immunohistochemistry may partially explain our and Josephs et al higher AGD frequencies; our studies are the most recent ones. Nevertheless, demographic differences among the series may also have contributed to the differences. Although not explicitly described, it is possible to infer than other series on AGD were enriched for individuals belonging to high SES, as oppose to the current series, which included a broad range of SESs with one-third of the subjects in the lower SESs. In fact, the strong association between low SES and AGD even after multivariate analyses was surprising. Because the cross-sectional nature of our series precludes investigating the causes of this association, further studies using longitudinal clinicopathological series including subjects belonging to different SESs may confirm if a low SES is a risk factor to AGD and by which mechanisms. Most importantly, longitudinal series may have information about the subject’s SES during childhood and early adulthood when environmental factors as nutrition, exposure to toxins, and quality of health care may have an higher impact on the risk of developing neurodegenerative conditions in late life (60–63). Unfortunately, our questionnaires were not designed to capture SES status at different life stages.

We failed to find an association between AGD and a specific APOE allele, in line with most of the previous studies (30, 31, 64). It is possible to speculate that our results could be related to particular features of the Brazilian population. Because we identified a similar distribution of APOE alleles in our non-AGD group and series from the United States and Europe (Supplementary Table 1), we hypothesize that the lack of association between a particular APOE allele and AGD is independent of the multiethnic composition of our sample.

The lack of distinctive antemortem clinical features of AGD and the extensive overlap between AGD and other dementing conditions represent considerable challenges to the understanding of the impact of AGD on cognitive decline (19, 20, 65, 66). We detected a total absence of other neuropathological changes in only 8 AGD cases (5%). Half of those had some degree of cognitive decline. Martinez-Lage and Munoz observed intellectual deterioration in 18% (n = 11) and Tolnay et al reported dementia in 54% of 35 clinically well-documented AGD cases (4, 39). However, it is unclear which percentage of these cases had no overlapping neuropathological changes. It is possible that neurofibrillary pathology/β-amyloid pathology under the threshold for AD could have had a role in the cognitive decline (31). Overlapping between AGD and low levels of AD-type pathology is common. In our series, 41% of the AGD cases showed a scarce amount of neurofibrillary tangles (Braak I–II) and 71% had low burden of β-amyloid pathology.

Previous studies suggested that AGD could be benign or even protective against cognitive decline (17). In fact, 59% of the participants with AGD pathology in the present study were cognitively normal, which is in line with several previous studies that have also identified a high prevalence of AGD pathology in controls. Davis et al found AGD in 23% of a total sample of 59 older cognitively normal subjects (37). In addition, Knopman et al found 12 AGD cases in a sample of 39 older cognitively normal individuals (38). Unfortunately, the cross-sectional and retrospectively nature of our study precludes identifying subtle cognitive differences between subjects with or without AGD or to capture a possible slowdown in cognitive decline rate associated to AGD.

Several studies point to a correlation between AGD and behavioral and psychological symptoms. Braak and Braak described that personality changes tend to precede memory failure in AGD and may help to distinguish AGD from AD patients (3). In our series, behavioral and psychological symptoms were found in 55% of pure-AGD subjects without cognitive impairment and 63% of AGD with mild neurofibrillary pathology (Braak stage I–II). Curiously, appetite and eating disorders were the most frequent neuropsychiatric change identified in AGD. Unfortunately, the NPI does not provide specific information on the type of appetite change detected and the neuroanatomical substrate for these changes in appetite remains unclear. It is possible to infer that the appetite changes reflect changes in the hypothalamus, a region vulnerable to AGD (9, 67). A previous human postmortem investigation identified early and prominent involvement of the hypothalamic lateral tuberal nucleus and moderate involvement of the ventromedial nucleus (which is associated with satiety) with relative resistance of tuberomamillary nucleus; the latter is susceptible to AD (67). Moreover, the hypothalamus connects to the hippocampal CA2 sector in mice, including the paraventricular nucleus that participates in appetite regulation (68–70). CA2 is extremely vulnerable to AGD pathology, although it is resistant to other tauopathies, including AD (57). We failed to identify differences in appetite disorders between pure-AGD and pure-AD groups. We believe that this result does not invalidate our findings because the pure-AD group has much worse cognitive status and a higher frequency of other behaviors and neuropsychiatric changes that may impact the appetite.

This study was limited by the lack of complete medical history data and its cross-sectional, retrospective design. The frequency of AGD pathology in subjects with severe AD-type pathology could be underestimated in our sample because a specific antibody marker for AGD is yet to be developed. Despite these limitations, this study has considerable strengths. This is the first study, to our knowledge, that examines demographic, clinical, and neuropathological aspects of AGD in different ethnicities and subjects from all socioeconomic strata.

Despite growing research interest in AGD, its pathophysiological mechanisms and clinical impact remain poorly understood. We hope that this manuscript will instigate other groups to further explore our findings. Prospective clinicopathological studies are needed to investigate the neuronal basis of appetite changes in AGD and investigate if other functions associated with the hypothalamus including sleep and circadian rhythm are part of the AGD clinical phenotype. Hormonal changes reflecting hypothalamic lesions such as leptin and ghrelin could also be explored as antemortem markers of AGD. Moreover, understanding the mechanisms behind the higher susceptibility to AGD in subjects in the lower SESs may disclose novel environmental risks factors for neurodegenerative diseases.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the families of the brain donors, the physicians, and staff of the São Paulo Autopsy service for their unconditional support and the Brazilian Aging Brain Study Group for their assistance with data collection.

REFERENCES

- 1.Braak H, Braak E. Argyrophilic grains: Characteristic pathology of cerebral cortex in cases of adult onset dementia without Alzheimer changes. Neurosci Lett 1987;76:124–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodriguez RD, Grinberg LT. Argyrophilic grain disease: An underestimated tauopathy. Dement Neuropsycol 2015;9:2–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braak H, Braak E. Argyrophilic grain disease: Frequency of occurrence in different age categories and neuropathological diagnostic criteria. J Neural Transm 1998;105:801–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martinez-Lage P, Munoz DG. Prevalence and disease associations of argyrophilic grains of Braak. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1997;56:157–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ding ZT, Wang Y, Jiang YP, et al. Argyrophilic grain disease: Frequency and neuropathology in centenarians. Acta Neuropathol 2006;111:320–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tolnay M, Clavaguera F. Argyrophilic grain disease: A late-onset dementia with distinctive features among tauopathies. Neuropathology 2004;24:269–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pham CT, de Silva R, Haik S, et al. Tau-positive grains are constant in centenarians' hippocampus. Neurobiol Aging 2011;32:1296–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saito Y, Nakahara K, Yamanouchi H, et al. Severe involvement of ambient gyrus in dementia with grains. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2002;61:789–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrer I, Santpere G, van Leeuwen FW. Argyrophilic grain disease. Brain 2008;131:1416–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seno H, Kobayashi S, Inagaki T, et al. Parkinson's disease associated with argyrophilic grains clinically resembling progressive supranuclear palsy: An autopsy case. J Neurol Sci 2000;178:70–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tatsumi S, Mimuro M, Iwasaki Y, et al. Argyrophilic grains are reliable disease-specific features of corticobasal degeneration. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2014;73:30–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masliah E, Hansen LA, Quijada S, et al. Late onset dementia with argyrophilic grains and subcortical tangles or atypical progressive supranuclear palsy? Ann Neurol 1991;29:389–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawashima T, Doh-ura K, Iwaki T. Argyrophilic grains in late-onset Creutzfeldt-Jakob diseased brain. Pathol Int 1999;49:369–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrer I, Barrachina M, Tolnay M, et al. Phosphorylated protein kinases associated with neuronal and glial tau deposits in argyrophilic grain disease. Brain Pathol 2003;13:62–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miserez AR, Clavaguera F, Monsch AU, et al. Argyrophilic grain disease: Molecular genetic difference to other four-repeat tauopathies. Acta Neuropathol 2003;106:363–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tolnay M, Sergeant N, Ghestem A, et al. Argyrophilic grain disease and Alzheimer's disease are distinguished by their different distribution of tau protein isoforms. Acta Neuropathol 2002;104:425–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grinberg LT, Wang X, Wang C, et al. Argyrophilic grain disease differs from other tauopathies by lacking tau acetylation. Acta Neuropathol 2013;125:581–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thal DR, Capetillo-Zarate E, Galuske RA. Tracing of temporo-entorhinal connections in the human brain: Cognitively impaired argyrophilic grain disease cases show dendritic alterations but no axonal disconnection of temporo-entorhinal association neurons. Acta Neuropathol 2008;115:175–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thal DR, Schultz C, Botez G, et al. The impact of argyrophilic grain disease on the development of dementia and its relationship to concurrent Alzheimer's disease-related pathology. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2005;31:270–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Josephs KA, Whitwell JL, Parisi JE, et al. Argyrophilic grains: A distinct disease or an additive pathology? Neurobiol Aging 2008;29:566–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tolnay M, Spillantini MG, Goedert M, et al. Argyrophilic grain disease: Widespread hyperphosphorylation of tau protein in limbic neurons. Acta Neuropathol 1997;93:477–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tolnay M, Mistl C, Ipsen S, et al. Argyrophilic grains of Braak: Occurrence in dendrites of neurons containing hyperphosphorylated tau protein. Neuropathol App Neurobiol 1998;24:53–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tolnay M, Probst A. Ballooned neurons expressing alphaB-crystallin as a constant feature of the amygdala in argyrophilic grain disease. Neurosci Lett 1998;246:165–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Botez G, Probst A, Ipsen S, et al. Astrocytes expressing hyperphosphorylated tau protein without glial fibrillary tangles in argyrophilic grain disease. Acta Neuropathol 1999;98:251–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Togo T, Dickson DW. Ballooned neurons in progressive supranuclear palsy are usually due to concurrent argyrophilic grain disease. Acta Neuropathol 2002;104:53–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kovacs GG, Pittman A, Revesz T, et al. MAPT S305I mutation: Implications for argyrophilic grain disease. Acta Neuropathol 2008;116:103–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ronnback A, Nennesmo I, Tuominen H, et al. Neuropathological characterization of two siblings carrying the MAPT S305S mutation demonstrates features resembling argyrophilic grain disease. Acta Neuropathol 2014;127:297–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Villela D, Kimura L, Schlesinger D, et al. Germline DNA copy number variation in individuals with Argyrophilic grain disease reveals CTNS as a plausible candidate gene. Genet Mol Biol 2013;4:498–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghebremedhin E, Schultz C, Botez G, et al. Argyrophilic grain disease is associated with apolipoprotein E epsilon 2 allele. Acta Neuropathol 1998;96:222–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tolnay M, Probst A, Monsch AU, et al. Apolipoprotein E allele frequencies in argyrophilic grain disease. Acta Neuropathol 1998;96:225–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fujino Y, Wang DS, Thomas N, et al. Increased frequency of argyrophilic grain disease in Alzheimer disease with 4R tau-specific immunohistochemistry. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2005;64:209–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jicha GA, Petersen RC, Knopman DS, et al. Argyrophilic grain disease in demented subjects presenting initially with amnestic mild cognitive impairment. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2006;65:602–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saito Y, Murayama S. Neuropathology of mild cognitive impairment. Neuropathology 2007;27:578–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maurage CA, Sergeant N, Schraen-Maschke S, et al. Diffuse form of argyrophilic grain disease: A new variant of four-repeat tauopathy different from limbic argyrophilic grain disease. Acta Neuropathol 2003;106:575–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ishihara K, Araki S, Ihori N, et al. Argyrophilic grain disease presenting with frontotemporal dementia: A neuropsychological and pathological study of an autopsied case with presenile onset. Neuropathology 2005;25:165–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferrer I, Hernandez I, Boada M, et al. Primary progressive aphasia as the initial manifestation of corticobasal degeneration and unusual tauopathies. Acta Neuropathol 2003;106:419–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davis DG, Schmitt FA, Wekstein DR, et al. Alzheimer neuropathologic alterations in aged cognitively normal subjects. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1999;58:376–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knopman DS, Parisi JE, Salviati A, et al. Neuropathology of cognitively normal elderly. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2003;62:1087–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tolnay M, Schwietert M, Monsch AU, et al. Argyrophilic grain disease: Distribution of grains in patients with and without dementia. Acta Neuropathol 1997;94:353–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ikeda K, Akiyama H, Arai T, et al. Clinical aspects of argyrophilic grain disease. Clin Neuropathol 2000;19:278–84 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Togo T, Isojima D, Akatsu H, et al. Clinical features of argyrophilic grain disease: A retrospective survey of cases with neuropsychiatric symptoms. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005;13:1083–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grau-Rivera O, Gelpi E, Rey MJ, et al. Prominent psychiatric symptoms in patients with Parkinson's disease and concomitant argyrophilic grain disease. J Neurol 2013;260:3002–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Asaoka T, Tsuchiya K, Fujishiro H, et al. Argyrophilic grain disease with delusions and hallucinations: A pathological study. Psychogeriatrics 2010;10:69–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nagao S, Yokota O, Ikeda C. et al. Argyrophilic grain disease as a neurodegenerative substrate in late-onset schizophrenia and delusional disorders. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2014;264:317–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grinberg LT, Ferretti RE, Farfel JM, et al. Brain bank of the Brazilian aging brain study group — A milestone reached and more than 1,600 collected brains. Cell Tissue Bank 2007;8:151–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.de Lucena Ferretti RE,, Damin AE,, Brucki SMD, et al. Post-mortem diagnosis of dementia by informant interview. Dement Neuropsycol 2010;2:138–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Almeida PM, Wickerhauser H. O critério ABA/ABIPEME: Em busca de uma atualização. São Paulo: Editora da Associação Brasileira dos Institutos de Pesquisa de Mercado; 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules. Neurology 1993;43:2412–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jorm AF. A short form of the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE): Development and cross-validation. Psychol Med 1994;24:145–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, et al. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: Comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology 1994;44:2308–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Calero O, Hortiguela R, Bullido MJ, et al. Apolipoprotein E genotyping method by real time PCR, a fast and cost-effective alternative to the TaqMan and FRET assays. J Neurosci Methods 2009;183:238–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Montine TJ, Phelps CH, Beach TG, et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease: A practical approach. Acta Neuropathol 2012;123:1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rub U, et al. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Aging 2003;24:197–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mackenzie IR, Neumann M, Bigio EH, et al. Nomenclature and nosology for neuropathologic subtypes of frontotemporal lobar degeneration: An update. Acta Neuropathol 2010;119:1–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thal DR, Rub U, Orantes M, et al. Phases of A beta-deposition in the human brain and its relevance for the development of AD. Neurology 2002;58:1791–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Braak H, Braak E. Cortical and subcortical argyrophilic grains characterize a disease associated with adult onset dementia. Neuropathol App Neurobiol 1989;15:13–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ishizawa T, Ko LW, Cookson N, et al. Selective neurofibrillary degeneration of the hippocampal CA2 sector is associated with four-repeat tauopathies. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2002;61:1040–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Saito Y, Ruberu NN, Sawabe M, et al. Staging of argyrophilic grains: An age-associated tauopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2004;63:911–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grinberg LT, Nitrini R, Suemoto CK, et al. Prevalence of dementia subtypes in a developing country: A clinicopathological study. Clinics (São Paulo) 2013;68:1140–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Larson EB, Yaffe K, Langa KM. New insights into the dementia epidemic. N Engl J Med 2013;369:2275–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nitrini R, Caramelli P, Herrera E, Jr, et al. Incidence of dementia in a community-dwelling Brazilian population. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2004;18:241–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Evans DA, Hebert LE, Beckett LA, et al. Education and other measures of socioeconomic status and risk of incident Alzheimer disease in a defined population of older persons. Arch Neurol 1997;54:1399–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sattler C, Toro P, Schonknecht P, et al. Cognitive activity, education and socioeconomic status as preventive factors for mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Psychiatry Res 2012;196:90–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Togo T, Cookson N, Dickson DW. Argyrophilic grain disease: Neuropathology, frequency in a dementia brain bank and lack of relationship with apolipoprotein E. Brain Pathol 2002;12:45–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sabbagh MN, Sandhu SS, Farlow MR, et al. Correlation of clinical features with argyrophilic grains at autopsy. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2009;23:229–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Steuerwald GM, Baumann TP, Taylor KI, et al. Clinical characteristics of dementia associated with argyrophilic grain disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2007;24:229–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schultz C, Koppers D, Sassin I, et al. Cytoskeletal alterations in the human tuberal hypothalamus related to argyrophilic grain disease. Acta Neuropathol 1998;96:596–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ahima RS, Antwi DA. Brain regulation of appetite and satiety. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2008;37:811–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cui Z, Gerfen CR, Young WS., III Hypothalamic and other connections with dorsal CA2 area of the mouse hippocampus. J Comp Neurol 2013;521:1844–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lein ES, Callaway EM, Albright TD, et al. Redefining the boundaries of the hippocampal CA2 subfield in the mouse using gene expression and 3-dimensional reconstruction. J Comp Neurol 2005;485:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.