Abstract

Lanthanide-doped upconversion nanoparticles hold promises for bioimaging, solar cells, and volumetric displays. However, their emission brightness and excitation wavelength range are limited by the weak and narrowband absorption of lanthanide ions. Here, we introduce a concept of multistep cascade energy transfer, from broadly infrared-harvesting organic dyes to sensitizer ions in the shell of an epitaxially designed core/shell inorganic nanostructure, with a sequential nonradiative energy transfer to upconverting ion pairs in the core. We show that this concept, when implemented in a core–shell architecture with suppressed surface-related luminescence quenching, yields multiphoton (three-, four-, and five-photon) upconversion quantum efficiency as high as 19% (upconversion energy conversion efficiency of 9.3%, upconversion quantum yield of 4.8%), which is about ~100 times higher than typically reported efficiency of upconversion at 800 nm in lanthanide-based nanostructures, along with a broad spectral range (over 150 nm) of infrared excitation and a large absorption cross-section of 1.47 × 10−14 cm2 per single nanoparticle. These features enable unprecedented three-photon upconversion (visible by naked eye as blue light) of an incoherent infrared light excitation with a power density comparable to that of solar irradiation at the Earth surface, having implications for broad applications of these organic–inorganic core/shell nanostructures with energy-cascaded upconversion.

Keywords: Upconversion, Dye-Sensitized, Rare-Earth, Lanthanide, Core/Shell, Nanoparticles

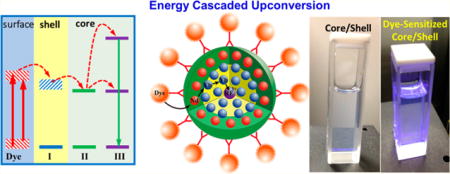

Graphical abstract

Upconversion nanoparticles (UCNPs) constitute a dilute guest–host system, in which lanthanide ions are doped as a guest in an appropriate dielectric host lattice, such as sodium yttrium fluoride (NaYF4), with a dimension of less than 100 nm.1 In UCNPs, typically, the doped Yb3+ ions (sensitizers) absorb infrared radiation and nonradiatively transfer excitation to the doped activators X3+ (X = Er, Ho, Tm) to produce visible or ultraviolet upconversion luminescence (UCL) (Figure 1a). Recent advances have enabled good control over UCNP size, phase, and emission colors.2–5 An improvement of the UCL intensity has also been reported through optimizing the concentration and distribution of doped lanthanide sensitizer/activator ions within a single nanoparticle,6–8 through coating nanoparticles with an inert/active shell to suppress surface-related luminescence quenching9,10 and by using metallic structures to plasmonically enhance the energy transfer rate.11 However, none of these approaches address the main limitation of UCNPs, namely the narrow and weak absorption associated with the nature of the 4f–4f electronic transitions of lanthanide ions. Specifically, the sensitizer ion Yb3+ absorbs light in a narrow spectral window of ~10 260–10 660 cm−1 (~10 times narrower than that of an organic dye),12 and with a critically small absorption cross section of ~10−20 cm2 (~1000–10 000 times lower than that of a dye molecule, ~10−17–10−16 cm2).13,14 This fundamental limitation impedes UCNPs in broadly harvesting infrared (IR) light and producing bright UCL, thus compromising their utility for a comprehensive range of applications.

Figure 1.

Simplified energy level diagrams depicting the classical and the proposed upconversion processes. (a) Energy transfer upconversion (ETU). An ETU mechanism involves two types of lanthanide ions in which one ion (ion I, sensitizer) successively transfers absorbed energy to a neighboring ion (ion II, activator), exciting ion II to its upper emitting state. (b) Proposed energy-cascaded upconversion (ECU), involving the use of an organic dye, three types of lanthanide ions, and a core–shell design. Note that the nanoparticle surface, the shell, and the core region are highlighted with three distinct colors. The dyes on the nanoparticle surface broadly harvest the excitation energy, which is nonradiatively transferred to the intermediate sensitizers (lanthanide ion I) in the shell, and then across the core/shell interface to the sensitizer (ion II) in the core, and finally to the activator (ion III) also in the core to produce upconversion via the classical ETU mechanism.

Addressing the problem of spectrally narrow and low intensity absorption of lanthanide-doped UCNPs, Hummelen’s group reported the design and synthesis of dye sensitized 10 nm NaYF4:Yb3+/Er3+ UCNPs in which excitation through absorption of the dye was realized.15 However, a large energy mismatch between the donating energy level of the dye and the accepting energy level of Yb3+ ions resulted in an inefficient energy transfer between them. Moreover, the utilized NaYF4:Yb3+/Er3+ nanoparticles had to be devoid of any shell in order to allow dye sensitization to occur. Consequently, strong surface-related deactivations were manifested that typically lead to UCL quenching, two to three orders stronger than that for a core/shell structure with suppressed deactivations.16 These limitations result in a very low upconversion quantum efficiency (UCQE) of ~0.2% (calculated from conventional upconversion quantum yield of ~0.1%),15 meaning that merely ~0.2% of the absorbed photons is upconverted into visible emission. The UCQE takes into consideration the conventional luminescence upconversion quantum yield (UCQY) and the order of photon processes involved in UCL (see Supporting Information Section G).17,18

Concept of Energy-Cascaded Upconversion

Herein, we introduce a new concept of energy-cascaded upconversion (ECU), which exploits a hybrid inorganic–organic system consisting of an epitaxial core/shell upconverting nanocrystal and near-infrared (NIR) dyes anchored on the core/shell nanocrystal surface (Figure 1b). The NIR dyes can broadly and strongly harvest NIR light, and subsequently initialize multistep directional nonradiative energy transfer to excite lanthanide ions positioned within the inorganic core to entail an upconversion process. Specifically, the steps of excitation energy transfer can be classified as (1) from NIR-absorbing organic dyes across the organic/inorganic interface to type I lanthanide ions (intermediate sensitizers) incorporated at the shell layer; (2) from the intermediate sensitizers in the shell across the core/shell lattice interface to type II lanthanide ions (sensitizers) in the core domain; and (3) from the sensitizer ions to type III lanthanide ions (activators) within the host lattice of the core to produce upconversion via the classical ETU mechanism (Figure 1a). This multistep cascade energy transfer strategy, in which each step involves a small energy gap and provides for a maximum overlap between the emission of an energy donor and the absorption of an energy acceptor, leads to high efficiency for the transfer of harvested light energy all the way down to the upconverting lanthanide ions in the core. A hierarchical alignment of electronic energy levels (the NIR dye, the intermediate sensitizer, and the sensitizer), as depicted in Figure 1b, favors an unidirectional transfer of the harvested energy to lanthanide activators, preventing inverse energy transfer that couples to the nanoparticle surface to decrease the UCL efficiency. Moreover, because a core/shell design has been employed, surface-related UCL quenching in the core is significantly suppressed by the shell. As a consequence, energy-cascaded upconversion in dye-sensitized core/shell nanoparticles synergistically combines the merits of a core/shell nanocrystal structure and the “antenna” effect from the dye, producing ultrabright UCL under excitation in a broad spectral range. As a proof of concept demonstration, we utilize the design of NIR dye sensitized core/shell (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ nanoparticles, in which Nd3+ ions are doped in the shell layer as the type I lanthanide ions (intermediate sensitizers), whereas the Yb3+ and Tm3+ ions are corresponding type II (sensitizer) and type III (activator) lanthanide ions positioned in the core.

Design of Efficient Inorganic Fluoride Core/Shell Upconversion Nanocrystals

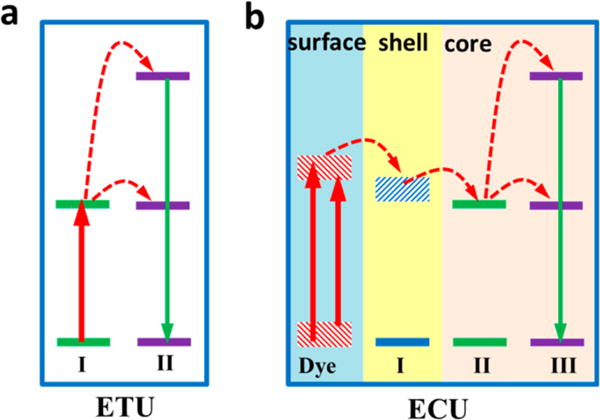

To realize high efficiency multistep energy-cascaded upconversion in a dye-sensitized core/shell structure, we first designed a core/shell nanocrystal of (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ and optimized nonradiative energy transfer from the Nd3+ in the shell to the Yb3+ ions in the core. We utilized NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5% UCNPs as a core with known efficient energy transfer between Yb3+ and Tm3+ ions.19 Monodispersed, hexagonal phase core/shell (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ x% nanoparticles of ~54 nm size, with a shell thickness of ~10 nm and x = 0–50% concentration of Nd3+ in the shell, were synthesized using a thermolysis procedure adapted from the literature (Supporting Information Section B).3 The crystallographic phase, the formation of a core/shell structure, the dimensions of the core and the shell, as well as the stoichiometric composition have been substantiated by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), X-ray diffraction (XRD), energy dispersive X-ray spectra (EDX), and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) (Figure 1a, Supporting Information Figures S4–S6 and Table S3). The observation of new intense absorption peaks of Nd3+ ions (at 740, 800, and 860 nm) from (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ 30% that are absent in (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4 core/shell nanoparticles confirms successful incorporation of Nd3+ ions in the NaYF4 shell layer (Supporting Information Figure S7). Core/shell nanoparticles of (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%, Nd3+ 3%)@NaYF4 were synthesized to examine the necessity of spatial isolation of the Yb3+/Tm3+ ion combination from the Nd3+ ions (to prevent possible cross-relaxation between the Tm3+ and Nd3+ ions). Complete quenching of UCL was observed when the Nd3+ ions were doped into the core, in contrast to UCL from the (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ 3% core/shell UCNPs (Supporting Information Figure S8). This validates the rational design of incorporation of the Nd3+ ions into the shell and of the Yb3+/Tm3+ ions into the core for high UCL, which at the same time grants an architecture for energy-cascaded upconversion.

The observed UCL in Figure 2b, when Nd3+ in the shell is excited at 800 nm, is the emission of Tm3+ peaked at: 340 nm (from the 1I6 state, five-photon process); 350, 450, and 510 nm (from the 1D2 state, four-photon process); and 480 and 660 nm (from the 1G4 state, three-photon process).20 The number of photons was determined from the dependence of the luminescence intensities on the laser excitation power density (Supporting Information Figure S35). The UCL intensities from the 1I6, 1D2 and 1G4 states of Tm3+ ions, all have a similar dependence on the Nd3+ concentration, reaching maximum at the Nd3+ concentration of 30% (Figure 2b and 2c). In analogy to UCL, the concurrent downconversion luminescence (DCL) from the Yb3+ ions is also dependent on the Nd3+ concentration (Supporting Information Figure S10). These dependences illustrate that the Nd3+ ions in the shell transfer excitation energy to the Yb3+ ions, which in turn sensitize the Tm3+ ions in the core. This conclusion is supported by the excitation spectra of UCL from the 1I6, 1D2, and 1G4 states of Tm3+ ions in the NaYbF4:Tm3+@NaYF4:Nd3+ 30% core/shell UCNPs (s). The observed UCL excitation peaks match the absorption peaks of the Nd3+ ions at 740, 800, and 860 nm, and the one of Yb3+ ions at 980 nm. Another evidence of energy transfer from Nd3+ in the shell to Yb3+ in the core was further provided by the luminescence spectra of the core/shell UCNPs without Tm3+ (NaYF4@ NaYF4:Nd3+ 3% and NaYF4:Yb3+ 30%@NaYF4:Nd3+ 3%) (s). The possible upconverting pathways in NaYbF4:Tm3+@NaYF4:Nd3+ core/shell UCNPs are described in Figure 3d, when exciting Nd3+ directly. An optimized UCL intensity at Nd3+ concentration of 30% arises from the competition between two parallel processes. One is to harvest light at ~800 nm and then transfer the harvested energy to Yb3+ ions. A high concentration of Nd3+ should favors the UCL process due to the increased absorption cross section of the core/shell nanoparticle as well as the elevated energy transfer rate from Nd3+ to Yb3+ ions. The other one is the detrimental cross relaxation process between the Nd3+ ions (4F3/2 + 4I9/2 → 24I15/2), which deactivates the harvested energy of Nd3+ ions (Figure S15 in the revised Supporting Information) and also increases with the increase of the Nd3+ concentration. A balanced effect might occur at an optimized Nd3+ concentration of 30%; increasing Nd3+ concentration over this value will make the detrimental effect surpass the beneficial effect, thus leading to the decrease of UCL.

Figure 2.

Design and characterizations of (NaYbF4:Tm3+)@ NaYF4:Nd3+ core/shell UCNPs. (a) TEM images of the synthesized (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ x% (x = 0, 10, 30) core/shell nanoparticles. (b) The UCL spectra of the colloidal (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ x% (x = 0, 3, 6, 10, 20, 30, 50) core/shell nanoparticles dispersed in hexane. Absorption of Yb3+ ion in all Nd3+-doped core/shell UCNPs were matched at ~980 nm to ensure an identical nanoparticle concentration for comparison (Supporting Information Figure S9). Excitation at 800 nm with a power density of 10 W/cm2. (c) Dependence of the UCL intensities from the 1I6, 1D2, and 1G4 states, on the Nd3+ concentration in the colloidal (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ x% core/shell UCNPs. The emissions peaked at 340 nm (1I6 →3F4), and at 350, 450, and 510 nm (from 1D2 state to 3H6, 3F4, and 3H5 states), as well as at 480 and 650 nm (from 1G4 to 3H6 and 3F4), were integrated to obtain the value of the overall emission intensities from the 1I6, 1D2, and 1G4 states, respectively.

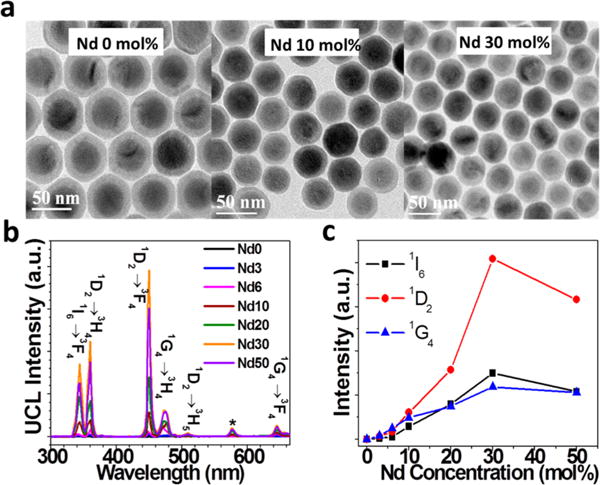

Figure 3.

Energy-cascaded upconversion in dye-sensitized fluoride core/shell nanocrystals. (a) Scheme of the proposed nanostructure. (b) UCL intensities from the 1I6, 1D2, and 1G4 states of Tm3+ as a function of the number ratio of IR-808 dye: NP for the (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ 30% UCNPs. Excitation at 800 nm, 10 W/cm2. (c) Dependencies of UCL enhancement in the (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ 30% UCNPs on the number ratio of IR 808 dye: NP for the (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ 30% UCNPs. The enhancement time is defined compared to the core/shell UCNPs without dye. Excitation at 800 nm, 10 W/cm2. (d) Proposed energy transfer pathways in the dye-sensitized core/shell structure. The higher energy levels of Nd3+ are omitted, as no UCL from the Nd3+ ions is observed. The dye molecules on the core/shell nanoparticle surface absorb photons and transfer excitation energy to the Nd3+ ions in the shell, which in turn sensitize Yb3+ ions in the core. Subsequently, intracore energy transfer from Yb3+ to Tm3+ excites the Tm3+ ions from the ground state to the 1G4, 1D2, and the 1I6 states. Radiative decays from these states produce five-photon induced UCL at 340 nm (1I6 → 3F4), four-photon induced UCL at 350, 450, and 510 nm (from 1D2 state to 3H6, 3F4, and 3H5 states), as well as three-photon luminescence at 480 and 650 nm (from 1G4 to 3H6 and 3F4). (e) UCL excitation spectra (for the integrated UCL intensity from the 1D2 state) for: IR-808 dye-sensitized (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ 30% (blue), (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ 30% (red), and canonical (NaYF4:Yb3+ 30%,Tm3+ 0.5%)/NaYF4 core/shell UCNPs (black). The broad and intense UCL excitation band peaked at ~800 nm proves the sensitization of the UCL by the IR-808 dye. (f) Fluorescence decay of the IR-808 dye from the IR-808 sensitized “blank” NaYF4 nanoparticles as well as the (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4, (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ 10%, and the (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ 30% core/shell nanoparticles.

Utilization of the Yb3+-enriched NaYbF4 host lattice as a core not only favors high UCL from Tm3+,19 but also facilitates the Nd3+ (shell) → Yb3+ (core) energy transfer process. The efficiency of a nonradiative energy transfer can be quantified using the following equation21

| (1) |

where ET stands for energy transfer efficiency, whereas τD and the τDA are the effective lifetimes of the energy donor in the absence and the presence of an energy acceptor, respectively. Following this equation and measuring decays of DCL from the Nd3+ ions, the energy transfer efficiency was determined to be ~39% and ~66% for (NaYF4:Yb3+)@NaYF4:Nd3+ 3% UCNPs containing 30% and 100% Yb3+ ions in the core, respectively (Supporting Information Figure S13). This result confirms the importance of using an Yb3+-enriched NaYbF4 host lattice as a core to produce efficient Nd3+ (shell) → Yb3+ (core) energy transfer. For the UCL-optimized core/shell nanoparticles of NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%@NaYF4:Nd3+ 30%, the energy transfer efficiency was determined to be as high as ~80% (Supporting Information Figure S14), despite an existence of the detrimental cross relaxation process between the Nd3+ ions (4F3/2 + 4I9/2 → 24I15/2, Supporting Information Figure S15).22

The integrated intensity of multiphoton UCL from the optimized (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ 30% UCNPs was found to be six times higher, when excited at ~980 nm, than that from the canonical ~30 nm sized NaYF4:Yb3+ 30%, Tm3+ 0.5%@NaYF4 core/shell nanoparticles, indicating successful suppression of surface-related quenching mechanisms and the importance of high Yb3+ content in the core for achieving intense UCL (Supporting Information Figures S16 and S17).23 When excited at ~800 nm, the integrated UCL from our optimized core/shell UCNPs is evaluated to be about ~41 times more intense than that from the (NaYF4:Yb3+ 20%, Tm3+ 0.5%, Nd3+ 1%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ 20% core/shell nanoparticles that have recently been reported as highly efficient UCNPs (Supporting Information Figure S18).24,25 The UCQE of our optimized (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ 30% core/shell UCNPs was determined to be about ~8.7% (UCQY is of 2.4%, upconversion energy conversion efficiency of 4.4%) when excited at 800 nm with 10 W/cm2 (Supporting Information Figure S34), which is about 40 times higher than 0.22% (UCQY of 0.11%), the highest value reported up to date for nanoparticles with UC induced by Nd3+ absorption (core/shell/shell nanostructure of NaYF4:Yb3+ 20%, Er3+ 2%@ NaYF4:Yb3+ 10%@NaNdF4:Yb3+ 10%, excited at 800 nm with 20 W/cm2).26 We attribute such a dramatic increase in UC efficiency to highly efficient energy transfer between Nd3+ in the shell and Yb3+ in the core, along with that between Yb3+ and Tm3+ within the core.

Energy-Cascaded Upconversion in Organic Dye-Sensitized Core/Shell Fluoride Nanocrystals

Nucleophilic substitution of the central chlorine atom in commercial IR-783 was used to prepare a carboxylic acid-functionalized derivative, coined as the IR-808 dye (see Supporting Information Scheme S1). The main absorption band of IR-808 is between 650 and 850 nm, with a maximum at 808 nm in DMF (Supporting Information Figure S19); dye mass extinction coefficient is 12.7 l g−1 cm−1, which is ~3000 times higher than that of the optimized (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ 30% core/shell nanoparticles at a peaked absorption wavelength of 794 nm (4.2 × 10−3 l g−1 cm−1) (Supporting Information Table S4). Negligible absorption of IR-808 below 650 nm is essential for the experiment, as the antenna dye should be transparent to the upconverted photons emitted by the nanoparticle (Supporting Information Figure S19). The emission spectrum of IR-808 overlaps strongly with the absorption peaks of Nd3+ in the shell and with that of the Yb3+ in the core of the (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ 30% core/shell nanoparticles (Supporting Information Figure S20). This overlap allows for nonradiative energy transfer from IR-808 to the Nd3+ ions in the shell and possibly to the Yb3+ ions in the core. A broad spectroscopic range (760–830 nm) of light excitation induced the same luminescence spectra of IR-808 (Supporting Information Figure S21). This spectroscopic behavior entails an identical mechanism of nonradiative energy transfer from IR-808 to doped trivalent lanthanides despite excitation at distinct wavelengths.

To produce a close contact between the IR-808 dye and the core/shell nanoparticle, a very short ionic NOBF4− ligand was first used to replace the original oleic ligand, following a protocol from the literature,27 and then further exchanged with the carboxylic-functionalized IR-808 dye. The success of ligand exchange in each step has been confirmed by the measured Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of involved samples (Supporting Information Figure S22). Attachment of IR-808 to the surface of the core/shell UCNPs was also clearly confirmed by changes in the spectral properties of the dye (Supporting Information Figures S23–S25). First, the emission peak for IR-808 attached to the core/shell UCNPs (dispersed in DMF) was shifted from 854 to 849 nm (Supporting Information Figure S23). At the same time, the absorption maximum wavelength of IR-808 in the dye-attached upconverting nanoparticles was blue-shifted from 808 to 804 nm (Supporting Information Figure S24). Second, fluorescence anisotropy measurement showed an apparent difference between a suspension of the dye attached to core/shell UCNPs and a free IR-808 solution, clearly revealing the binding of IR-808 to the surface of the nanoparticles (Supporting Information Figure S25). The attachment of the IR 808 dye to the nanoparticle surface is a complex process, involving three possible mechanisms that include electrostatic interaction, physical adsorption, and chemical coordination interaction. For chemical coordination mechanism, both the carboxylic acid and the sulfate groups of IR 808 dye can contribute to its anchoring to the nanoparticle surface (as confirmed by the FTIR spectra shown in Supporting Information Figure S22). The orientation of the dye molecules on the surface is difficult to ascertain but is supposed to be approximately parallel to the nanoparticle surface when chemical coordination plays the dominant role.

The possibility of energy transfer from IR 808 to the Nd3+ ions was experimentally verified through dye sensitization of pure Nd3+ doped NaYF4 nanoparticles, whereby luminescence from the Nd3+ ions was enhanced 33 times at an optimal dye concentration (Supporting Information Figure S26). We then tested the energy-cascaded upconversion by exploring the energy transfer pathways depicted in Figures 3a and 3d, that is, dye → Nd (in the shell) → Yb (in the core) → Tm (in the core), using a range of Nd3+-sensitized core/shell structures described in Figure 2. When introducing varied concentrations of the IR 808 dye into these core/shell nanoparticle dispersions (in DMF), the UCL intensities from the 1I6, 1D2, and 1G4 states exhibit a strong dependence on the dye: NP ratio (Figure 3b and c, Supporting Information Figure S27 for core/shell UCNPs with varied Nd3+ concentrations of 8–50% in the shell). The UCL intensities were all enhanced by more than 1 order of magnitude, when excited at 10 W/cm2 at 800 nm; for example, the UCL from the optimized (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@ NaYF4:Nd3+ 30% core/shell UCNPs were enhanced 14-fold (Figure 3c). We found that the photostability of the dye associated with UCNPs is similar to that of the free dye (Supporting Information Figure S28). It is worth noting that the nonlinear nature of upconversion makes the enhancement effect become much more pronounced at lower excitation density range (Supporting Information Figure S29).28 The UCL boost is also visible from the photographic images of UCNPs dispersions with and without the dye (s). These enhancement results verify the antenna effect provided by the dye attached to the core/shell nanoparticle surface. To confirm this, the excitation spectra for the upconversion emission from the 1D2 state (Figure 3e) as well as from the 1I6 and 1G4 states (Supporting Information Figure S31) were measured for the IR-808-sensitized in comparison to pure (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ 30% core/shell nanoparticles. A broad, intense band between 700 and 850 nm was clearly observed for the dye-sensitized UCNPs, in marked contrast to the narrow and weak peaks of Nd3+ ions at 800 and 860 nm for the nanoparticles without dye sensitization. Moreover, the shape of this broad excitation band exactly matches the absorption band of IR-808, clearly demonstrating that the antenna effect stems from the dye (Supporting Information Figure S31).

The dye antenna effect can take place through two mechanisms of energy transfer: (i) radiative type and (ii) nonradiative type. A linear dependence of the UCL intensity on the diluted concentrations of the dye-sensitized core/shell UCNPs rules out the radiative type mechanism (Supporting Information Figure S32). Moreover, we acquired the decay of fluorescence of the IR-808 bound to the surface of the (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ (0, 10, and 30%) core/shell nanoparticles (Figure 3f). The average lifetime of IR-808 fluorescence was gradually shortened with an increase of the Nd3+ concentration in the shell, from 2.10 ns (IR-808 for the blank NaYF4 nanoparticle) to 1.80, 1.62, and 0.37 ns for the shell Nd3+ concentration of 0, 10, and 30%, respectively. This shortening of fluorescence lifetime confirms a nonradiative type of energy transfer from the IR-808 dye to Nd3+, whereas the decreasing decay trend reveals the important impact of the Nd3+ concentration to enhance the energy transfer efficiency. The maximal efficiency of nonradiative energy transfer was determined to be about ~82% for the optimized core/shell UCNPs doped with 30% Nd3+ in the shell. Though nonradiative energy transfer from IR-808 to Nd3+ might take place through a Föster-type or a Dexter-type mechanism,29 we believe that the long-range Förster type is more likely to occur because of the unchanged spin associated with the energy transfer, as well as the distance between the dye and the Nd3+ ion, defined by the geometric size of the IR-808 dye (~2 nm) and a random distribution of the Nd3+ ion in a 10 nm thick shell. Moreover, the energy gap is ~170 cm−1 between the singlet electronic excitation level of the IR-808 dye and the 4F5/2/2H9/2 level of Nd3+, and 990 cm−1 between the 4F3/2 level of Nd3+ and the 2F5/2 level of Yb3+, whereas the energy gap between the NIR dye and Yb3+ is 2200 cm−1. According to these energy gaps as well as pertinent optical parameters, we calculated that multistep cascade energy transfer (from the dye to Nd3+, and then to Yb3+) can be about 1.5 times more efficient than a direct energy transfer from the IR-808 dye to the Yb3+ ions (Supporting Information Section J1). Moreover, the Förster radius was determined to be ~1.9 nm, and the actual distance between the IR-808 dye and the Nd3+ ions was estimated to be ~1.5 nm according to the measured energy transfer efficiency (~80%), indicating a close contact between the dye and the inorganic core/shell nanoparticle surface (Supporting Information Section J1).

As illustrated in Figure 3b and c, the luminescence intensities from the 1I6, 1D2, and 1G4 states all increase first with the increased dye: NP ratio, which is consistent with increasing overall absorption of the excitation energy at 800 nm by an increasing number of surface-bound antenna molecules. However, beyond a certain concentration, a further increase of the IR-808/nanoparticle ratio results in decreased luminescence intensities. The observed decline can be explained by two factors: increased mutual interactions between the antenna molecules on the core/shell nanoparticle surface (self-quenching) and an increasing concentration of unbound (excess) antenna molecules which absorb the excitation energy but do not transfer it to the nanoparticles. We theoretically modeled the kinetics to interpret the dependence of the UCL intensities from the 1I6, 1D2, and 1G4 states on the IR-808 dye concentration under an extreme saturation excitation regime as in the case shown in Figure 3b, where the intensity of UCL is proportional to the excitation power density (Supporting Information Figure S35).27 We consider the following dynamic process to model: laser excitation of the dye, radiative and nonradiative deexcitation of the dye in the excited state, concentration quenching of the dye in the excited state, energy transfer from the dye to the Nd3+, the back energy transfer from the Nd3+ to the dye, radiative and nonradiative deactivation of Nd3+ in the excited state, as well as concentration quenching of Nd3+ in the excited state (see Supporting Information Section J2). Our kinetic modeling results reveal that self-quenching of the antenna dyes is the main mechanism to decrease UCL at high concentrations, agreeing well with all measured experimental data (Figure 3b).

The optimum dye:NP number ratio was determined to be ~830 (corresponding to an optimum weight ratio of 1:304); this means that a mean of ~830 antenna molecules (absorption cross section, 1.84 × 10−17 cm2) is bound to the surface of per (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ 30% core/shell nanoparticle (absorption cross section, 1.48 × 10−15 cm2) at this ratio; the intermolecular distance of dyes is estimated to be ~3 nm, that is close to the length scale of the IR-808 dye (~2 nm) (Supporting Information Section F). The absorption cross section of a single dye-bound core/shell nanoparticle is calculated to be as large as 1.48 × 10−14 cm2 (in good agreement with the experiment-determined value of 1.47 × 10−14 cm2), which is about 10 times higher than that of a single (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ 30% core/shell nanoparticle, and ~1000 times higher than a single organic dye molecule (absorption cross section, ~10−17 cm2).

The optimized UCL from the IR-808 dye-sensitized (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ 30% core/shell UCNPs was shown to be ~14 times higher than that of (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ 30% UCNPs without the dye, 658 times higher than the reported highly efficient (NaYF4:Yb3+ 20%, Tm3+ 0.5%, Nd3+ 1%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ 20% core/shell nanoparticles,24 and more than 40 000 times higher than that of the (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)/NaYF4 nanoparticles when excited at ~800 nm (10 W/cm2) (Supporting Information Figure S33). Moreover, the intensity of UCL from the 1D2 state (~350 nm) in the IR 808 dye-sensitized core/shell structure, when excited at 800 nm, is about 25 times higher than that from the canonical core/shell nanoparticles of the hexagonal phase (NaYF4:Yb3+ 30%, Tm3+ 0.5%)/NaYF4 (size, 30 nm), when excited at ~980 nm using the same laser power (Figure 3e).23 The UCQE of the optimized IR 808 dye-sensitized (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4 Nd3+ 30% core/shell nanocrystals was evaluated to be as high as 19% (upconversion energy conversion efficiency 9.3%, UCQY 4.8%;) when excited at ~800 nm with 10 W/cm2 (Supporting Information Figure S34). This UCQE is also comparable to the highest reported one of 22% up to date for two-photon blue upconversion via organic triplet–triplet annihilation (~450 nm emission, excited at ~532 nm).30 This value is higher than that from the (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ 30% core/shell nanoparticles, dye-sensitized (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4 core/shell nanoparticles, and the dye-sensitized NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5% nanoparticles (Supporting Information Figure S34). In addition, we show that energy-cascaded upconversion is not limited to the type of inorganic host lattice employed here to build a core/shell structure (Supporting Information Figure S36), to the type of organic dyes employed to sensitize (Figure 4a), or to the type of activator utilized here to produce UCL (Supporting Information Figures S37 and S38), extending the proposed concept to a general type of dye-sensitized inorganic core/shell nanostructures.

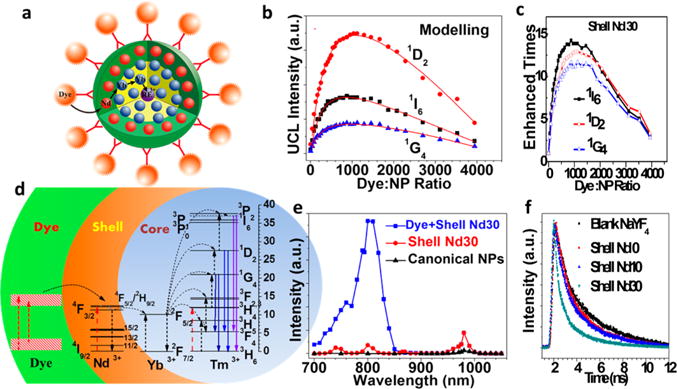

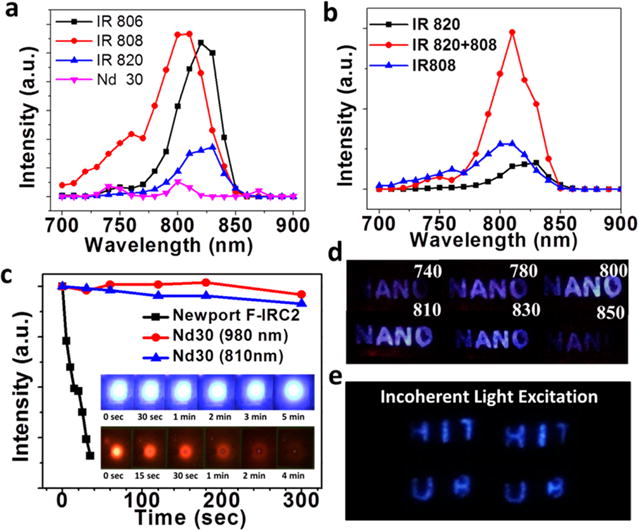

Figure 4.

Co-sensitization and applications of an inorganic fluoride core/shell nanostructure. (a) Excitation spectra of UCL peaked at 350 nm from the core/shell (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ 30% nanoparticles (Nd 30) as well as from the IR 808-sensitized (IR 808), the IR 806-sensitized (IR 806), and the IR 820-sensitized (IR 820) core/shell (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ 30% nanoparticles. (b) Excitation spectra of UCL peaked at 350 nm from IR 808-sensitized, IR 820-sensitized, as well as the IR 808 and IR 820-co-sensitized core/shell (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ 30% nanoparticles. An exact amount of IR 808 and IR 820 is utilized for the co-sensitization experiment as the one used for single dye sensitization. (c) Photostability of UCL from a homemade IR card and a commercial IR card (Newport F-IRC2, Irvine, CA) excited at 810 nm, 1 W/cm2. The inset shows the photographic images of both cards taken at different time points. The photostability of UCL from homemade IR card excited at ~980 nm is shown as a reference (1 W/cm2). As laser photons at ~980 nm directly act on the Yb3+ ions to excite the Yb3+/Tm3+ ion pairs for upconversion, no photobleaching exists under this excitation condition. (d) Blue upconversion from regular letters printed using an upconverting ink made by the IR-808-sensitized (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ core/shell nanoparticles and polystyrene. (e) Upconversion of incoherent light (halogen lamp) by the IR-808 and IR-820 co-sensitized (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ core/shell nanoparticles (0. 016 W/cm2). A long pass optical filter was used to cut off light below 750 nm.

Co-Sensitization and Applications of Dye-Sensitized Core/Shell Fluoride Nanocrystals

Along with IR-808, we showed that the commercially available IR dyes of IR-806 and IR-820 can sensitize (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ 30% core/shell nanoparticles to create energy-cascaded upconversion (Figure 4a). A simultaneous use of the IR-808 and the IR-820 dyes is able to produce a pronounced co-sensitizing antenna effect, which synergistically adds up the sensitization effect from each type of the involved dyes (Figure 4b). The dye co-sensitizing results provides an opportunity to produce a comprehensive IR harvesting spectral range for energy-cascaded upconversion through simultaneous use of a set of IR dyes that possess varying absorption spectra.

A broad spectral response as well as a high UCQE promises the use of dye-sensitized (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ 30% UCNPs in many applications. A straightforward application is visualization of a broad spectrum of invisible IR lasers. In fact, under excitation in the spectral range of 720–870 nm, blue UCL can be viewed by naked eye, from the IR-808 and IR-820 co-sensitized (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ 30% UCNPs in DMF and in our homemade IR card (Supporting Information Figure S39). In addition to this broad spectral response provided by IR dye sensitization, direct excitation of Yb3+/Tm3+ ions provides another spectral IR range of 920–1000 nm for visualizing via upconversion (Supporting Information Figure S40). We also compared the performance of our homemade IR card with that of a commercial IR card (Newport F-IRC2) under identical laser irradiance. As illustrated in Figure 4c, visible yellow luminescence from the commercial Newport IR card disappears after less than 20 s of illumination, whereas blue UCL from our homemade IR card exhibits a slight reduction of ~10% after 300 s of irradiation, which is apparently associated with dye photobleaching. As such, the necessity of frequent movement of a commercial IR card for visualization of lasers is eliminated when using homemade IR card containing dye-sensitized core/shell nanoparticles.

As a proof-of-concept demonstration of security applications of dye-sensitized core/shell nanoparticles, regular letters were printed using an invisible ink-like suspension, formulated by a mixture of IR-808-sensitized UCNPs and visibly transparent polystyrene polymer. These secured printed semitransparent letters appear to be slightly visible, with low contrast letters for the naked eye, but turn into high contrast blue letters when irradiated with a multitude of IR wavelengths in the range of 730–980 nm (Figure 4d, and Supporting Information Figure S40). The ability to utilize numerous excitation IR wavelengths for decoding provides strong potential for wide use of IR-808-sensitized core/shell UCNPs for security purpose. Moreover, we demonstrated that low power incoherent light from a conventional light source can be utilized to excite IR-808 and IR-820 co-sensitized core/shell UCNPs, producing adequate UCL for visualization (Figure 4e). Clear letters with blue upconversion (three photon process) can be seen and captured by an iPhone 5s camera, even with an excitation power density of 0.016 W/cm2 in the spectral range of 750–1100 nm. It should be noted that this level of power density is comparable with sun power density at Earth’s surface (~0.0163 W/cm2 of average power density and whole spectrum; sun power density at the equator can be as high as 0.1 W/cm2). According to our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of incoherent light induced three-photon upconversion. This highly efficient upconversion can have important implications in many fields (e.g., to increase the efficiency via circumventing IR transmission losses in solar cells and to visualize NIR light in night vision devices).

Conclusion

We have introduced and validated a concept of energy-cascaded upconversion using NIR dye sensitized (NaYbF4:Tm3+ 0.5%)@NaYF4:Nd3+ core/shell nanoparticles as a model. Broadly absorbing infrared dyes are able to efficiently harvest irradiation energy, which is nonradiatively transferred to the Nd3+ ions in the shell (efficiency, 82%) and, sequentially, to the Yb3+ ions in the core (efficiency, 80%) that sensitize Tm3+ ions positioned also in the core to produce multiphoton UCL. This multistep energy-cascaded transfer enables an upconversion quantum efficiency as high as 19% (upconversion energy conversion efficiency of 9.3%, upconversion quantum yield of 4.8%), a broad NIR excitation response range over 150 nm (700–850 nm), along with a large absorption cross section of 1.47 × 10−14 cm2 per single dye-sensitized core/shell nanoparticle. This energy-cascaded upconversion can be applied to a set of different IR dyes and lanthanide emitters, as well as to other fluoride host lattices. The utilization of dye-sensitized core/shell nanoparticles for several applications (IR laser detection, security decoding, as well as incoherent light upconversion) was demonstrated, with implications for a broad spectrum of photonic applications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a grant from the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (Grant No. 1096313-1-58130), the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (No.51325201), the International Cooperation Project in the Ministry of Science and Technology (No.2014DFA50740), the Program for Basic Research Excellent Talents in Harbin Institute of Technology, China (BRETIII 2012018), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, China (AUGA5710052614).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b02830.

Chemicals and instrumentation, synthetic procedures, sample preparations, supporting figures for core/shell nanostructures, supporting figures for IR dye-sensitized core/shell nanostructures, estimations of molecular weights, number of dyes per core/shell nanoparticle, and intermolecular distance of IR dye on the surface of a core/shell nanoparticle, quantification of upconversion quantum efficiency, pump power dependence, supporting figures for generalization of dye-sensitized core/shell structure, supporting figures for applications, and the theoretical modeling. (PDF)

Author Contributions

G.C. conceived the idea and designed all pertinent experiments. J.D. and W.S. synthesized inorganic core/shell nanoparticles; G.C., H.Q., and W.S. obtained dye-sensitization results; T.Y.O. contributed to the idea development and design the spectroscopy experiments and took part in the spectral measurements as well as in demonstration of incoherent light upconversion; R.R.V. and H.Å. did theoretical modeling; X.W. and G.H. synthesized IR-808 dyes, Y.W. measured lifetimes of IR dyes; G.C. and T.Y.O. prepared the manuscript, and all authors discussed and commented on the manuscript. G.C. and P.N.P. directed the project.

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Chen GY, Qiu HL, Prasad PN, Chen XY. Upconversion Nanoparticles: Design, Nanochemistry, and Applications in Theranostics. Chem Rev. 2014;114(10):5161–5214. doi: 10.1021/cr400425h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang F, Han Y, Lim CS, Lu YH, Wang J, Xu J, Chen HY, Zhang C, Hong MH, Liu XG. Simultaneous phase and size control of upconversion nanocrystals through lanthanide doping. Nature. 2010;463(7284):1061–1065. doi: 10.1038/nature08777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mai HX, Zhang YW, Si R, Yan ZG, Sun LD, You LP, Yan CH. High-quality sodium rare-earth fluoride nanocrystals: Controlled synthesis and optical properties. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128(19):6426–6436. doi: 10.1021/ja060212h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li ZQ, Zhang Y. An efficient and user-friendly method for the synthesis of hexagonal-phase NaYF4: Yb, Er/Tm nanocrystals with controllable shape and upconversion fluorescence. Nanotechnology. 2008;19(34):5. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/19/34/345606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deng RR, Qin F, Chen RF, Huang W, Hong MH, Liu XG. Temporal full-colour tuning through non-steady-state upconversion. Nat Nanotechnol. 2015;10(3):237–242. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao JB, Jin DY, Schartner EP, Lu YQ, Liu YJ, Zvyagin AV, Zhang LX, Dawes JM, Xi P, Piper JA, Goldys EM, Monro TM. Single-nanocrystal sensitivity achieved by enhanced upconversion luminescence. Nat Nanotechnol. 2013;8(10):729–734. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2013.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gargas DJ, Chan EM, Ostrowski AD, Aloni S, Altoe MVP, Barnard ES, Sanii B, Urban JJ, Milliron DJ, Cohen BE, Schuck PJ. Engineering bright sub-10-nm upconverting nanocrystals for single-molecule imaging. Nat Nanotechnol. 2014;9(4):300–305. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li XM, Wang R, Zhang F, Zhao DY. Engineering Homogeneous Doping in Single Nanoparticle To Enhance Upconversion Efficiency. Nano Lett. 2014;14(6):3634–3639. doi: 10.1021/nl501366x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yi GS, Chow GM. Water-soluble NaYF4:Yb,Er(Tm)/NaYF4/polymer core/shell/shell nanoparticles with significant enhancement of upconversion fluorescence. Chem Mater. 2007;19(3):341–343. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vetrone F, Naccache R, Mahalingam V, Morgan CG, Capobianco JA. The Active-Core/Active-Shell Approach: A Strategy to Enhance the Upconversion Luminescence in Lanthanide-Doped Nanoparticles. Adv Funct Mater. 2009;19(18):2924–2929. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu DM, Garcia-Etxarri A, Salleo A, Dionne JA. Plasmon-Enhanced Upconversion. J Phys Chem Lett. 2014;5(22):4020–4031. doi: 10.1021/jz5019042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carnall WT, Goodman GL, Rajnak K, Rana RS. A Systematic Analysis of the Spectra of the Lanthanides Doped into Single-Crystal LaF3. J Chem Phys. 1989;90(7):3443–3457. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deloach LD, Payne SA, Chase LL, Smith LK, Kway WL, Krupke WF. Evaluation of Absorption and Emission Properties of Yb3+ Doped Crystals for Laser Applications. IEEE J Quantum Electron. 1993;29(4):1179–1191. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt J, Penzkofer A. Absorption Cross-Sections, Saturated Vapor-Pressures, Sublimation Energies, and Evaporation Energies of Some Organic Laser-Dye Vapors. J Chem Phys. 1989;91(3):1403–1409. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zou WQ, Visser C, Maduro JA, Pshenichnikov MS, Hummelen JC. Broadband dye-sensitized upconversion of near-infrared light. Nat Photonics. 2012;6(8):560–564. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen GY, Agren H, Ohulchanskyy TY, Prasad PN. Light upconverting core-shell nanostructures: nanophotonic control for emerging applications. Chem Soc Rev. 2015;44(6):1680–1713. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00170b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh-Rachford TN, Castellano FN. Photon upconversion based on sensitized triplet-triplet annihilation. Coord Chem Rev. 2010;254(21–22):2560–2573. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou J, Liu Q, Feng W, Sun Y, Li FY. Upconversion Luminescent Materials: Advances and Applications. Chem Rev. 2015;115(1):395–465. doi: 10.1021/cr400478f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen GY, Ohulchanskyy TY, Kumar R, Agren H, Prasad PN. Ultrasmall Monodisperse NaYF4:Yb3+/Tm3+ Nanocrystals with Enhanced Near-Infrared to Near-Infrared Upconversion Photoluminescence. ACS Nano. 2010;4(6):3163–3168. doi: 10.1021/nn100457j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang GF, Qin WP, Wang LL, Wei GD, Zhu PF, Kim RJ. Intense ultraviolet upconversion luminescence from hexagonal NaYF4: Yb3+/Tm3+ microcrystals. Opt Express. 2008;16(16):11907–11914. doi: 10.1364/oe.16.011907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clapp AR, Medintz IL, Mauro JM, Fisher BR, Bawendi MG, Mattoussi H. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer between quantum dot donors and dye-labeled protein acceptors. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126(1):301–310. doi: 10.1021/ja037088b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bednarkiewicz A, Wawrzynczyk D, Nyk M, Strek W. Synthesis and spectral properties of colloidal Nd3+ doped NaYF4 nanocrystals. Opt Mater. 2011;33(10):1481–1486. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu CT, Svenmarker P, Liu HC, Wu X, Messing ME, Wallenberg LR, Andersson-Engels S. High-Resolution Fluorescence Diffuse Optical Tomography Developed with Nonlinear Upconverting Nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2012;6(6):4788–4795. doi: 10.1021/nn3015807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xie XJ, Gao NY, Deng RR, Sun Q, Xu QH, Liu XG. Mechanistic Investigation of Photon Upconversion in Nd3+-Sensitized Core-Shell Nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135(34):12608–12611. doi: 10.1021/ja4075002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang YF, Liu GY, Sun LD, Xiao JW, Zhou JC, Yan CH. Nd3+-Sensitized Upconversion Nanophosphors: Efficient In Vivo Bioimaging Probes with Minimized Heating Effect. ACS Nano. 2013;7(8):7200–7206. doi: 10.1021/nn402601d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhong YT, Tian G, Gu ZJ, Yang YJ, Gu L, Zhao YL, Ma Y, Yao JN. Elimination of Photon Quenching by a Transition Layer to Fabricate a Quenching-Shield Sandwich Structure for 800 nm Excited Upconversion Luminescence of Nd3+ Sensitized Nanoparticles. Adv Mater. 2014;26(18):2831–2837. doi: 10.1002/adma.201304903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dong AG, Ye XC, Chen J, Kang YJ, Gordon T, Kikkawa JM, Murray CB. A Generalized Ligand-Exchange Strategy Enabling Sequential Surface Functionalization of Colloidal Nanocrystals. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(4):998–1006. doi: 10.1021/ja108948z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suyver JF, Aebischer A, Garcia-Revilla S, Gerner P, Gudel HU. Anomalous power dependence of sensitized upconversion luminescence. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater Phys. 2005;71(12):125123. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.71.125123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ward MD. Mechanisms of sensitization of lanthanide(III)-based luminescence in transition metal/lanthanide and anthracene/lanthanide dyads. Coord Chem Rev. 2010;254(21–22):2634–2642. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim JH, Deng F, Castellano FN, Kim JH. High Efficiency Low-Power Upconverting Soft Materials. Chem Mater. 2012;24(12):2250–2252. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.