Abstract

Background

Cardiovascular risk factors tend to aggregate. The biological and predictive value of this aggregation is questioned and genetics could shed light on this debate. Our aim was to reappraise the impact of risk factor confluence on ischemic heart disease (IHD) risk by testing whether genetic risk scores (GRSs) associated with these factors interact on an additive or multiplicative scale, and to determine whether these interactions provide additional value for predicting IHD risk.

Methods and Results

We selected genetic variants associated with blood pressure, body mass index, waist circumference, triglycerides, type-2 diabetes, HDL and LDL cholesterol, and IHD to create GRSs for each factor. We tested and meta-analyzed the impact of additive (Synergy Index –SI–) and multiplicative (βinteraction) interactions between each GRS pair in one case-control (n=6,042) and four cohort studies (n=17,794), and evaluated the predictive value of these interactions. We observed two multiplicative interactions: GRSLDL·GRSTriglycerides (βinteraction=−0.096; Standard Error=0.028) and non-pleiotropic GRSIHD·GRSLDL (βinteraction=0.091; Standard Error=0.028). Inclusion of these interaction terms did not improve predictive capacity.

Conclusions

The confluence of LDL cholesterol and triglycerides genetic risk load has an additive effect on IHD risk. The interaction between LDL cholesterol and IHD genetic load is more than multiplicative, supporting the hazardous impact on atherosclerosis progression of the combination of inflammation and increased lipid levels. The capacity of risk factor confluence to improve IHD risk prediction is questionable. Further studies in larger samples are warranted to confirm and expand our results.

Keywords: risk factor, genetic variation, risk assessment, genetics, association studies, clustering, interactions

Introduction

The Framingham Heart Study introduced the term “cardiovascular risk factor”1 to define traits that are associated with cardiovascular disease and have a capacity to predict future events2. Some of these risk factors are interrelated and tend to aggregate. A paradigm of this aggregation is metabolic syndrome3, which is associated with an increase in cardiovascular events4,5. However, there is an open debate about whether this confluence of cardiovascular risk factors provides clinical or mechanistic information beyond the mere addition of its individual components6-8. In other words, is the combination of risk factors more valuable than the sum of its parts?

An ideal way to reliably assess the impact of these risk factors on cardiovascular risk, individually and in combination, would be to perform a prospective cohort study of individuals with different, stable, long-term levels of exposure to these risk factors and with different combinations of each. Alternatively, this approach could be circumvented by genetic analysis, in which variants associated with cardiovascular risk factors are used as a proxy for the risk factors themselves. Specifically, each risk factor could be represented by a genetic risk score (GRS) composed of multiple variants that are known to be robustly associated with that risk factor9,10. While this approach has the disadvantage of capturing a limited fraction of the total variance of the risk factor itself, it does have some important advantages. First, a GRS represents constant lifetime exposure within individuals and variable exposure between individuals, with random combinations of alleles according to Mendel's Second Law11. Second, it is an efficient and economically feasible approach to this clinically important question.

In this study, we used the genetically determined variability of classical risk factors to reappraise the value of risk factor confluence in assessing ischemic heart disease (IHD) risk. Our specific aims were i) to analyze whether GRSs associated with the individual cardiovascular risk factors interact and present more than an additive or multiplicative association with IHD, and ii) to determine whether these interactions provide additional value for predicting the risk of future IHD events.

Methods

Design

A meta-analysis of five studies, one case-control and four prospective cohorts, was carried out. The studies included the Myocardial Infarction Genetics Consortium (MIGen)12 and the Framingham Heart Study (FHS), FINRISK 1997, FINRISK 2002, and Estonian Biobank (EGCUT)13 cohorts. A total of 23,836 participants were included in the meta-analysis, 6,042 from the case-control study and 17,794 from the four cohorts.

MIGen, an international case-control study, included 2,967 cases of early-onset myocardial infarction (MI) (men ≤50 and women ≤60 years old) and 3,075 age- and sex-matched controls (12). The FHS sample consisted of 3,557 individuals from the FHS offspring cohort attending exam 5. Genome-wide genotype and associated phenotype data from MIGen and FHS were obtained via the database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP; http://dbgap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov; project number #5195). The FINRISK cohorts are comprised of representative, cross-sectional population survey respondents. Surveys have been carried out every 5 years since 1972 to assess the risk factors of chronic diseases and health behaviors in the working age population; 5,562 individuals were included from the FINRISK 1997 cohort and 2,314 from the FINRISK 2002 cohort. Finally, the EGCUT cohort of 50,750 participants recruited between 2002 and 2011 includes adults (aged 18-103 years) from all counties of Estonia, approximately 5% of the Estonian average-adult population13. A subset of 6,361 individuals was included in the study selected for this meta-analysis.

SNP Selection

We mined published data from a series of large meta-analyses of Genome Wide Association studies for each of the selected phenotypes. From these studies we identified SNPs that were associated (p<5×10-8) with the trait of interest, and grouped these into 8 categories broadly definable as distinct cardiovascular risk factors or coronary endpoints (Supplementary Table 1): low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol14, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol14, triglycerides (TG)14, blood pressure (BP)15-16, type 2 diabetes (T2D)17, body mass index (BMI)18, waist circumference19 and ischemic heart disease (IHD)20. We additionally included genetic variants associated with schizophrenia21 as a negative control.

Genotyping

Four different arrays and two reference panels were used for genotyping and imputing. The MIGen study used the Affymetrix 6.0 GeneChip and imputing was performed with MACH 1.0 using the HapMap CEU phased chromosomes as reference. The FHS used the Affymetrix 500K and 50K chips, imputing was performed using HapMap CEU as reference. FINRISK used the Illumina HumanCoreExome chip, imputation was performed using IMPUTE v222 and the 1000 Genomes Project sequencing data as a reference panel23. EGCUT used the Illumina OmniExpress BeadChip, imputation was implemented in IMPUTE v2 using the 1000 Genomes Project as a reference. In all the cohorts, directly genotyped SNPs were coded as 0, 1 or 2, while the dosage was used for the imputed SNPs with values ranging between 0 and 2. SNPs with an imputation quality <0.4 were excluded.

Construction of the genetic risk scores (GRS)

We constructed a weighted GRS for each cardiovascular risk factor of interest and IHD independently by adding the number of risk alleles weighted by their effect sizes on the phenotype of interest (Supplementary Table 1). One SNP could be included in more than one GRS when associated with more than one risk factor, although with different weight.

We also constructed a weighted GRS for each cardiovascular risk factor, excluding those SNPs that were related to any trait other than that of interest (non-pleiotropic GRSs). From the list of variants associated with each trait, we excluded those that were associated with any other trait with a p-value less than 0.10 in the Framingham cohort.

Ischemic heart disease outcomes

In the MIGen case-control study, only early-onset myocardial infarction cases were included. In the cohort studies, two IHD outcomes were defined: hard IHD, including fatal and non-fatal myocardial infarction and coronary death, and all IHD, additionally including angina and revascularization. The follow-up methodology in the prospective cohorts is explained in detail in the supplementary material. In summary, a follow-up or linkage with national databases was implemented using predefined ICD9 and ICD10 codes. In each cohort, cases were categorized by an event committee.

Statistical methods

The association between each GRS and IHD was tested by a logistic regression model in the case-control study and by Cox proportional hazards models in the cohort studies. Furthermore, we analyzed all potential pairwise interactions between the GRSs of interest and IHD. In the analysis of these interactions –and from a methodological point of view– we considered their departure from additivity and multiplicativity24: i) to test for multiplicative interactions we added, one by one, all pairwise products of GRSs to the logistic or Cox regression models; and ii) to analyze departure from additivity several metrics have been recommended, relative excess risk due to interaction (RERI), attributable proportion (AP), and synergy index (SI)24-25. We selected the SI metric because it has been proposed as the most robust when the model includes covariates to control for confounding 26:

Where:

- HR/ORA+B+ = Hazard ratio/Odds ratio of those exposed to factor A and B compared to those non-exposed to factor A and B.

- HR/ORA+B- = Hazard ratio/Odds ratio of those exposed to factor A but not to factor B compared to those non-exposed to factor A and B.

- HR/ORA-B+ = Hazard ratio/Odds ratio of those exposed to factor B but not to factor A compared to those non- exposed to factor A and B.

This index measures the extent to which the hazard or odds ratio for both exposures together exceeds 1, and whether this is greater than the sum of the extent to which each risk ratio, considered separately, exceeds 1. A SI > 1 would indicate the presence of an additive interaction. Bootstrapping was used to calculate 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) of the estimate25.

All the analyses were adjusted for age, sex, and principal genetic components to account for population stratification and family relatedness27. We used a Bonferroni-adjusted p-value to account for independent multiple testing. Due to the correlation between the 36 pairs of tested interactions (each GRS of interest was included in 8 different pairwise interaction terms, we estimated the number of effective independent tests according to the matrix of variance-covariance28; the resulting value was 35.88. Therefore, the statistical threshold was set at 0.05/35.88=0.0014. A meta-analysis of the results observed in the different studies was undertaken using an inverse-variance weighting under a random-effects model (DerSimonian-Laird method)29. Heterogeneity between studies included in this meta-analysis was also analyzed by estimating the I2 and its p-value. To assess whether an individual study had strong effects and influenced the pooled results, a sensitivity analysis was performed by excluding one study at a time and calculating the multiplicative and additive interaction metrics for the remaining studies.

The improvement in the predictive capacity of the statistically significant interaction terms was evaluated by assessing improvements in discrimination and reclassification in the cohort studies:

The improvement in the discriminative capacity of the model was evaluated using the change in the c-statistic30. We first evaluated the discriminative capacity of a multivariate model including age, sex, and all the individual GRSs of interest; additionally, we evaluated the discriminative capacity of this multivariable model, further including the significant interaction terms individually in different models.

The reclassification capacity of the interactions of interest was evaluated by calculating the continuous net reclassification improvement index (c-NRI) and the integrated discrimination improvement index (IDI)31-32.

These analyses were also performed in the individual studies and meta-analyzed using an inverse-variance weighting under a random-effects model.

All statistical analyses were carried out using packaged or custom functions written in R-3.02 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna)33.

Ethics Statement

All participants gave written informed consent to be included in these studies. The study was approved by the local Clinical Research Ethics Committees.

Results

The characteristics of the individuals included in the five studies, and the number of incident coronary events (938 hard events and 1,453 events in total) and median follow-up in the four cohorts, are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Participants in the Five Studies Included in the Meta-analysis (Number and Percentage Shown for Categorical Variables, Mean and Standard Deviation for Continuous Variables).

| Study | MIGen* | FHS* | FINRISK1997 | FINRISK2002 | EGCUT* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design | Case-control | Cohort | Cohort | Cohort | Cohort |

| N | 6,042 | 3,557 | 5,562 | 2,314 | 6,361 |

| Hard IHD events | 2967 | 168 | 367 | 145 | 258 |

| All IHD events | --- | 251 | 447 | 185 | 570 |

| Follow-up, years (SD) | --- | 12.8 (6.2) | 13.8 (2.9) | 9.2 (1.9) | 5.4 (2.4) |

| N women (%) | 1,422 (23.54%) | 1,880 (52.9%) | 2,878 (51.7%) | 1,106 (47.8%) | 3,615 (56.8%) |

| Age, in years | NA* | 54.61 (9.8) | 47.9 (13.3) | 51.7 (12.6) | 48.2 (19.4) |

| SBP*, in mmHg | NA | 125.8 (18.6) | 135.8 (19.7) | 137.9 (20.4) | 128.6 (18.1) |

| DBP*, in mmHg | NA | 74.5 (9.9) | 82.3 (11.3) | 80.2 (11.3) | 78.7 (10.9) |

| BMI*, in kg/m2 | NA | 27.4 (5.0) | 26.6 (4.5) | 27.5 (5.1) | 26.5 (5.2) |

| HTN*, n (%) | NA | 1,020 (28.7%) | 2,477 (44.5%) | 1,143 (49.4%) | 1,771 (27.8) |

| LDL cholesterol*, in mg/dL | NA | 125.1 (34.5) | 134.8 (35.9) | 138.2 (48.7) | 137.3 (40.8)† |

| HDL cholesterol*, in mg/dL | NA | 50.1 (15.1) | 54.8 (13.5) | 58.7 (18.9) | 58.8 (15.9)† |

| Triglycerides, in mg/dL | NA | 139.4 (78.6) | 130.1 (90.3) | 137.2 (92.9) | 139.2 (90.9)† |

| Current Smoking, n (%) | NA | 610 (17.2%) | 1,355 (24.4%) | 617 (26.7%) | 1,904 (29.9%) |

MIGen: Myocardial Infarction Genetics Consortium; FHS: Framingham Heart Study; EGCUT: Estonian Biobank; SBP: Systolic blood pressure; DBP: Diastolic blood pressure; BMI: Body mass index; HTN: Hypertension; LDL: Low-density lipoprotein; HDL: High-density lipoprotein; NA: Not available.

Data available in a subsample of 3,782 individuals.

SNP selection and sample description

From the literature sources described above, 484 independent SNPs were reported to be robustly associated with cardiovascular risk factors or coronary endpoints14-20. The number of SNPs included in the GRSs ranged from 23 for Type 2 diabetes (T2D) to 81 for BMI (Supplementary Table 1). There was a slight overlap between the different GRSs in terms of number of shared SNPs or loci but the Spearman correlation coefficient between GRSs was weak (correlation coefficient, ρ<0.100) with the exception of the associations between GRSs for TG and HDL (ρ=-0.391), IHD and LDL (ρ=0.182), TG and LDL (ρ=0.170), and HDL and LDL (ρ=0.129) (Supplementary Table 2). When the non-pleiotropic GRSs were considered only the correlation between TG and HDL GRSs (ρ=-0.142), and between TG and LDL GRSs (ρ=0.379) remained significant. A strong and consistent association across studies between the GRS and their corresponding risk factors was observed, remaining strong and consistent for lipids and body mass index when the non-pleiotropic GRS were analyzed (Supplementary Table 3).

Association between genetic risk scores and ischemic heart disease

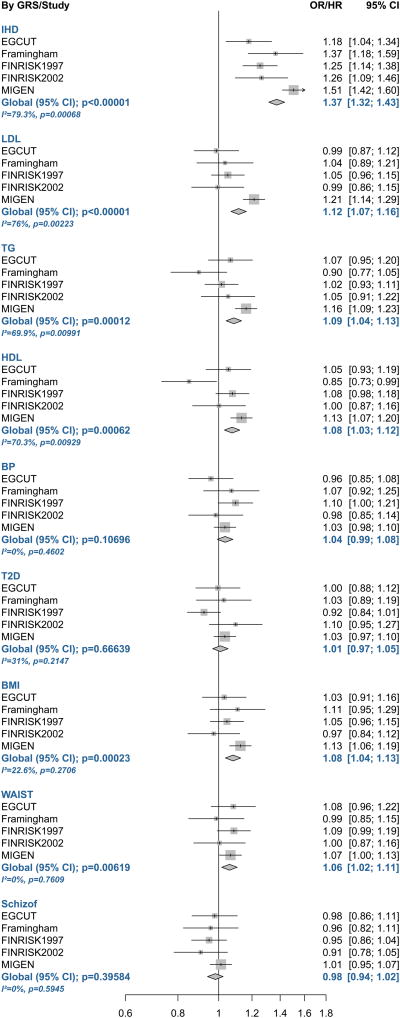

We observed significant associations between the GRS for IHD and hard coronary events in all the studies and in the meta-analysis (p-value=9.4×10-47) (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 4; and Supplementary Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 5 for all IHD events). The TG, HDL, LDL, BMI, and waist GRSs were also associated with coronary events in the meta-analyses of hard IHD events, although these associations were mainly driven by the MIGen study (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 4). The blood pressure, diabetes, and schizophrenia GRSs were not associated with coronary events in this meta-analysis (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 4). When the non-pleiotropic GRSs were considered, only the association between the GRS for IHD and coronary events remained significant (Supplementary Table 6).

Figure 1.

Forest Plot of the Association Between the Weighted Genetic Risk Scores for Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Ischemic Heart Disease and the Prevalence/Incidence of Hard Ischemic Heart Disease Events (Myocardial Infarction or Ischemic Heart Disease Death) Across Studies and in the Meta-analysis.

Assessment of interactions between genetic risk scores and impact on ischemic heart disease risk

We tested all pairwise interactions between the GRSs of interest and IHD in the different studies. In the meta-analyses we found two statistically significant multiplicative interactions (Supplementary Tables 7 and 8). A negative multiplicative interaction between the LDL and TG GRSs on all IHD events (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 8). When hard IHD events were considered, the magnitude of the association of the interaction term decreased, from -0.096 to -0.047) (Table 3), but this decrease was driven by the MIGen study; when that study was excluded the effect of the interaction term on hard IHD remained similar and statistically significant (β=-0.116; p-value=1.3×10-4) (Supplementary Table 9). A positive multiplicative interaction between the non-pleiotropic LDL and IHD GRSs on all IHD and hard IHD was also observed (Table 2), and was robust and consistent in the sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Table 9).

Table 2.

Significant Multiplicative Interaction Terms Between Genetic Risk Scores of Interest Associated with Ischemic Heart Disease Identified in the Meta-analyses.

| Regression coefficient (Standard Error) | P-value | P-value Heterogeneity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GRSLDLxGRSTG | |||

| Hard events | -0.047 (0.021) | 0.027 | 0.011 |

| All events | -0.096 (0.028) | 5.2×10-4 | 0.252 |

| Non-pleiotropic GRSLDLxGRSIHD | |||

| Hard events | 0.064 (0.022) | 0.022 | 0.003 |

| All events | 0.091 (0.028) | 1.2×10-3 | 0.461 |

GRS: Genetic risk score; IHD: Ischemic heart disease; TG: Triglycerides; LDL: Low-density lipoprotein.

Table 3.

Results of the Improvement in Predictive Capacity when the GRSLDL and GRSTG, and the Non-pleiotropic GRSLDL and GRSIHD Interaction Terms Were Added to the Model Based on the Individual Genetic Risk Scores: Changes in Discrimination Capacity (δ c-Statistics) and in Reclassification (Continuous Net Reclassification Index –c-NRI– and Integrated Discrimination Improvement –IDI–) for the Two Ischemic Heart Disease Outcomes in the Meta-analyses.

| Hard IHD Outcomes | All IHD Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|

| GRSLDL·GRSTG | ||

| δ c-statistic (p-value) | 0.000 (0.471) | 0.000 (0.217) |

| c-NRI (95% CI)* | 0.011 (-0.030, 0.052) | 0.030 (-0.021, 0.081) |

| IDI (95% CI)* | 0.000 (-0.001, 0.001) | 0.000 (-0.001, 0.002) |

| Non-pleiotropic GRSIHD·GRSLDL | ||

| δ c-statistic (p-value) | 0.001 (0.263) | 0.000 (0.637) |

| c-NRI (95% CI)* | 0.031 (-0.011, 0.073) | 0.029 (-0.019, 0.077) |

| IDI (95% CI)* | 0.001 (-0.000, 0.001) | 0.001 (-0.000, 0.003) |

c-NRI (95% CI): Continuous Net Reclassification Index (95% Confidence Interval); IDI (95% CI): Integrated Discrimination Improvement (95% Confidence Interval)

We also analyzed the presence of additive interactions. In the meta-analysis, we did not find any statistically significant additive interaction term (Supplementary Tables 10 and 11).

We estimated 80% statistical power to detect a multiplicative interaction regression coefficient higher or lower than ± 0.077, considering the observed standard error (0.020) and a p-value=0.0014. We also estimated 80% power to detect a synergy index higher than 1.28 or lower than 0.72, considering the lower observed standard error (0.07), and a synergy index higher than 2.57 or lower than -0.57, considering the higher observed standard error (0.39), always with a p-value=0.0014.

Assessment of the predictive capacity of the scores

We evaluated improvement in the discrimination of coronary events in the different cohort studies. First we used a model that included age, sex, the GRSs for all the cardiovascular risk factors evaluated, and the first two principal genetic components. Second, we added to the model, the interaction terms that were associated with IHD (GRSLDL·GRSTG, and non-pleiotropic GRSIHD·GRSLDL). Including these interaction terms did not improve the discriminative or reclassification capacity of coronary events in the meta-analysis (Table 3).

Discussion

In the present study, we evaluated the potential interaction effects between cardiovascular risk factors on ischemic heart disease risk using a genetic approach. We tested the departure from an additive or multiplicative effect of the different two-pair combinations of GRSs related to these risk factors and their association with coronary events. We report two significant multiplicative interactions (GRSLDL·GRSTG and non-pleiotropic GRSIHD·GRSLDL) modulating coronary risk. The inclusion of these interaction terms in the multivariate model did not improve the predictive capacity of the model based on the individual effects of the GRSs of interest.

We first evaluated the association of each individual GRS with its corresponding risk factors and these associations were strong and consistent across studies. We also evaluated the effects of each individual GRS on IHD risk in each study and meta-analyzed the results. The GRS for IHD was associated with coronary events in all the studies and also in the meta-analysis. The GRSs for the different risk factors were also associated with hard coronary events in the meta-analysis, with the exception of the GRSs for blood pressure, diabetes, and schizophrenia (which was included as a negative control). These results validate the GRSs; the lack of association of IHD events with blood pressure and diabetes could be related to the lack of causal relationship11, low statistical power in the prospective studies, or other factors.

The debate about whether the aggregation of cardiovascular risk factors provides additional information on vascular health beyond that of each individual components is still open. The paradigm for this discussion is metabolic syndrome. Our choice of a genetic approach to assess whether different risk factors interact to modulate the risk of IHD was based on the premise that a genetic score for a given risk factor captures some of its population variability; however, the extent to which this is true varies markedly between risk factors. The amount of variance in the traits of interest that is accounted for by genetic scores varies from ∼25% to 30% for LDL cholesterol14 down to no more than 3% for blood pressure15. However, the loss of information that this represents, with respect to measuring the phenotype itself, is counterbalanced by the fact that genetic risk is a constant exposure throughout an individual's lifespan. Some studies have suggested that selecting a list of SNPs nominally associated with a trait increases the explained variability of that trait34. In this study, we selected only those SNPs consistently replicated in GWAS to be associated with the phenotypes of interest. The allelic scores that include thousands of genetic variants tend to lack specificity, and therefore should be used with caution and perhaps only to analyze proxy biological intermediates, not to analyze the association with other related clinical phenotypes34, as in the present study. Moreover, the list of nominally associated SNPs could vary across studies. For all these reasons, we preferred to select those variants with a statistically significant association, considering the GWAS threshold for our analyses.

In the analysis of these interactions we considered their departure from additivity and multiplicativity24 and identified two multiplicative interaction terms, one showing a less than multiplicative effect (GRSLDL·GRSTG) and other a more than multiplicative effect (non-pleiotropic GRSLDL·GRSIHD). The LDL and TG GRSs were slightly correlated. This association could be related to common molecular mechanisms or to the use of the Friedewald equation to estimate LDL in most epidemiological studies. Although this collinearity could decrease the statistical power of our analyses, we report a statistically significant multiplicative interaction between the genetic load for LDL cholesterol and TG. This interaction term had a negative value, indicating that the joint effect of these two factors is less than multiplicative in the risk ratio scale. Moreover, as the additive interaction between these two factors was not statistically significant, we can assume an additive effect of these two factors on IHD risk in the risk ratio scale. This type of additive but not multiplicative effect of two risk factors has also been reported in other diseases, e.g., to describe the joint effects of smoking and asbestos on lung cancer35. The explanation of this additive effect could be related to basic lipid profile concepts36. The lipid profile includes measurement of the total amount of the two most important lipids in the plasma compartment: cholesterol and TG. These lipids are not soluble in plasma, and are carried in association with proteins, the so-called lipoproteins: HDL, LDL and TG-rich lipoproteins. The TG-rich lipoproteins also transport remnant cholesterol. Triglycerides can be degraded by most cells, but cholesterol cannot; therefore, the cholesterol content of TG-rich lipoproteins, rather than increased TG levels per se, is the more likely contributor to atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease36. The negative multiplicative interaction indicates an additive effect between TG and LDL cholesterol on IHD risk, and supports the suggestion that TG-rich particles act as an additional source of cholesterol in the arterial wall.

We also report a more than multiplicative effect between the non-pleiotropic genetic load for LDL and IHD. The IHD genetic load has been related to lipid, inflammatory and immune pathways that could potentiate the progression of atherosclerosis37. The non-pleiotropic GRS for IHD excluded SNPs associated with lipids and mainly reflects inmuno-inflammatory mechanisms. Therefore, this interaction could be explained by the independent interrelationships between lipids and inmuno-inflammation that could trigger the deleterious consequences of these two factors through different mechanisms38,39.

We also analyzed the improvement in predictive capacity when the interaction terms were included in the model. However, we did not observe any improvement in the discrimination or reclassification. Recent meta-analyses focused on metabolic syndrome have shown that the population with this syndrome has a two-fold higher risk of cardiovascular disease than the rest of the population4-5 but the added value of this clinical constellation of risk factors is questioned6-8. We identified 1 cross-sectional study40 and 6 cohort studies41-46 that assessed the unadjusted and adjusted association between metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk. When the models were adjusted for all or some of the classical cardiovascular risk factors, 3 of these studies showed an association between metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular events43,45-46. However, Girman et al only adjusted for the estimated coronary risk obtained with the Framingham function, categorized as ≤20% or >20%45, and McNeill et al did not adjust for HDL cholesterol and BP46. In contrast, our analyses did not show any interaction between the GRSs related to the risk factors that define metabolic syndrome. Our results are in line with the two remaining studies, which specifically analyzed whether metabolic syndrome improves the predictive capacity of its individual components. Neither study reported significant improvement in discrimination capacity44,46; this shared finding calls into question the capacity of the metabolic syndrome diagnosis to improve a cardiovascular risk calculation based on the individual classical cardiovascular risk factors.

Limitations of the study

Four main limitations should be considered: i) The variability of the cardiovascular traits explained by the genetic scores considered in this analysis is not very high, in general, but represents lifetime exposure. Moreover, some interacting genetic variants could have been overlooked by GWAS and therefore not included in our GRSs; ii) The small number of events observed in the cohort studies limited the statistical power to explore the interactions of interest. We have also to consider that when the magnitude of the association between the two individual components of the interaction and the outcome of interest is small the power to differentiate between additive and multiplicative effects is reduced; iii) IHD clinical endpoints are the result of a complex phenomenon, which includes endothelial dysfunction, plaque formation and growth, plaque stability, and thrombosis. Interaction could happen in the context of one of these pathways and be diluted in the observation of clinical end-points; and iv). Although the approach we used could be considered as Mendelian randomization11, we must be cautious about interpreting the causality and synergistic effect of the confluence of risk factors. First, the genetic instrumental variable is a genetic score composed by multiple risk alleles10. In some cases, the biological pathway linking each risk allele to the intermediate trait of interest is unknown, and therefore the assumption that the only causal pathway from the genetic variant to IHD involves the trait of interest is questionable. Moreover, there may be association(s) between the genetic variants and unmeasured/unknown confounders; for example, the genetic load of obesity could be related to food choices that could also be directly related to coronary risk. We also must consider the presence of pleiotropic effects that are reflected in the correlation between the GRSs analyzed and that violate one of the assumptions of Mendelian randomization studies.

Finally, we would note that 339 of the FINRISK participants were also included in the MIGen sample; however, this is a small proportion (<1.5%) of the whole sample, the sensitivity analyses carried out are consistent, and we could consider the effect of this duplication to be minimal.

Conclusions

The genetic risk loads for LDL cholesterol and TG interact, suggesting that the effect of these two risk factors on IHD risk is additive rather than multiplicative. Moreover, the non-pleiotropic GRSs for LDL and IHD also interact on IHD risk and have a more than multiplicative effect. This interaction supports the hazardous impact on atherosclerosis progression of the combination of inflammation and increased lipid levels. Our results question the added value of the confluence of risk factors in improving the estimation of cardiovascular risk beyond the predictive capacity provided by individual risk factors. However, further studies in larger samples are warranted to confirm and expand our results, due to the limited statistical power of the present analysis.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspective.

Cardiovascular risk factors tend to aggregate but the biological and predictive value of this aggregation is questioned and genetics could shed light on this debate. Our aim was to test whether genetic risk scores (GRSs) associated with these cardiovascular risk factors interact on an additive or multiplicative scale and whether these interactions add predictive value. The genetic risk loads for LDL cholesterol and triglycerides (TG) interacted, but with a less than multiplicative joint effect. Therefore, the confluence of these two risk factors has an additive effect on ischemic heart disease (IHD) risk. This result suggests that the cholesterol content of TG-rich lipoproteins, rather than increased TG levels per se, is the more likely contributor to atherosclerosis. The non-pleiotropic GRSs for LDL and IHD also interact, but have a more than multiplicative effect. This finding supports the hazardous impact on atherosclerosis progression of the combination of inflammation and increased lipid levels. The inclusion of these two interaction terms in a risk function did not improve the predictive capacity of the individual genetic risk loads. Our results question the added value of the confluence of risk factors to improve the estimation of cardiovascular risk beyond the predictive capacity provided by individual risk factors. However, further studies in larger samples are warranted to confirm and expand our results, due to the limited statistical power of the present analysis.

Acknowledgments

Access to the Myocardial Infarction Genetics Consortium (MIGen) and Framingham data was provided through the Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP; http://dbgap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov; project number #5195). The MIGen Consortium was funded by grant R01 HL087676 (NIH, USA). The Framingham Heart Study is conducted and supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) in collaboration with Boston University (Contract No.N01-HC-25195). This manuscript was not prepared in collaboration with investigators of the Framingham Heart Study and does not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the Framingham Heart Study, Boston University, or NHLBI. Funding for SHARe genotyping was provided by NHLBI Contract N02-HL-64278. To Elaine M. Lilly, PhD, (Writer's First Aid) for her critical reading and revision of the English text.

Sources of Funding: This work was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Innovation through the Carlos III Health Institute [Red de Investigación Cardiovascular RD12/0042, CIBER Epidemiología y Salud Pública, PI09/90506, PI12/00232], European Funds for Development (ERDF-FEDER), and by the Catalan Research and Technology Innovation Interdepartmental Commission [SGR 1195]. GL was funded by the Juan de la Cierva Program, Ministry of Education (JCI-2009-04684). SSB was funded by an iPFIS contract, Carlos III Health Institute (IFI14/00007). FINRISK: The FINRISK surveys were mainly funded from budgetary funds of Finland's National Institute for Health and Welfare. Important additional funding has been obtained from the Academy of Finland (grant # 139635) and from the Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research. EGCUT received financing from FP7 grants (278913, 306031, 313010), an Estonian Research Council Grant (GP1GV9353), the Center of Excellence in Genomics (EXCEGEN), and the University of Tartu (SP1GVARENG).

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

References

- 1.Kannel WB, Dawber TR, Kagan A, Revotskie N, Stokes J., III Factors of risk in the development of Coronary Heart Disease—Six-Year Follow-up Experience. The Framingham Study. Ann Intern Med. 1961;55:33–50. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-55-1-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Donnell CJ, Elosua R. Cardiovascular risk factors. Insights from Framingham Heart Study. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2008;61:299–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donate KA, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome. Circulation. 2009;120:1640–1645. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gami AS, Witt BJ, Howard DE, Erwin PJ, Gami LA, Somers VK, et al. Metabolic syndrome and risk of incident cardiovascular events and death. A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:403–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mottillo S, Filion KB, Genest J, Joseph L, Pilote L, Poirier P, et al. The metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1113–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reaven GM. The metabolic syndrome: requiescat in pace. Clin Chem. 2015;51:931–938. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.048611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kahn R, Buse J, Ferrannini E, Stern M. The metabolic syndrome: time for a critical appraisal. Joint statement from the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2289–2304. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.9.2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woodward M, Tunstall-Pedoe H. The metabolic syndrome is not a sensible tool for predicting the risk of coronary heart disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2009;16:210–214. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3283282f8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hindorff LA, MacArthur J, Morales J, Junkins HA, Hall PN, Klemm AK, et al. A Catalog of Published Genome-Wide Association Studies. [Accessed [15-01-2013]]; Available at: www.genome.gov/gwastudies.

- 10.Burgess S, Thompson SG. Use of allele scores as instrumental variables for Mendelian randomization. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:1134–1144. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burges S, Timpson NJ, Ebrahim S, Davey Smith G. Mendelian randomization: where are we now and where are we going? Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44:379–388. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kathiresan S, Voight BF, Purcell S, Musunuru K, Ardissino D, Mannucci, et al. Genome-wide association of early-onset myocardial infarction with single nucleotide polymorphisms and copy number variants. Nat Genet. 2009;41:334–341. doi: 10.1038/ng.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leitsalu L, Haller T, Esko T, Tammesoo ML, Alavere H, Snieder H, et al. Cohort Profile: Estonian Biobank of the Estonian Genome Center, University of Tartu. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;44:1137–1147. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Global Lipids Genetics Consortium. Willer CJ, Schmidt EM, Sengupta S, Peloso GM, Gustafsson S, et al. Discovery and refinement of loci associated with lipid levels. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1274–1283. doi: 10.1038/ng.2797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ehret GB, Munroe PB, Rice KM, Bochud M, Johnson AD, Chasman DI, et al. Genetic variants in novel pathways influence blood pressure and cardiovascular disease risk. Nature. 2011;478:103–109. doi: 10.1038/nature10405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wain LV, Verwoert GC, O'Reilly PF, Shi G, Johnson T, Johnson AD, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies six new loci influencing pulse pressure and mean arterial pressure. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1005–1011. doi: 10.1038/ng.922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahajan A, Go MJ, Zhang W, Below JE, Gaulton KJ, Ferreira T, et al. Genome-wide trans-ancestry meta-analysis provides insight into the genetic architecture of type 2 diabetes susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2014;46:234–244. doi: 10.1038/ng.2897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Locke AE, Kahali B, Berndt SI, Justice AE, Pers TH, Day FR, et al. Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology. Nature. 2015;518:197–206. doi: 10.1038/nature14177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shungin D, Winkler TW, Croteau-Chonka DC, Ferreira T, Locke AE, Mägi R, et al. New genetic loci link adipose and insulin biology to body fat distribution. Nature. 2015;518:187–196. doi: 10.1038/nature14132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nikpay M, Goel A, Won HH, Hall LM, Willenborg C, Kanoni S, et al. A comprehensive 1,000 Genomes-based genome-wide association meta-analysis of coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2015;47:1121–1130. doi: 10.1038/ng.3396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature. 2014;511:421–427. doi: 10.1038/nature13595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Howie BN, Donnelly P, Marchini J. A flexible and accurate genotype imputation method for the next generation of genome-wide association studies. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000529. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.1000 Genomes Project Consortium. Abecasis GR, Auton A, Brooks LD, DePristo MA, Durbin RM, et al. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature. 2012;491:56–65. doi: 10.1038/nature11632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.VanderWeele TJ, Knol MJ. A Tutorial on Interaction. Epidemiol Method. 2014;3:33–72. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knol MJ, Van der Tweel I, Grobbee DE, Numans ME, Geerlings MI. Estimating interaction on an additive scale between continuous determinants in a logistic regression model. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:1111–1118. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skrondal A. Interaction as departure from additivity in case-control studies: A cautionary note. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:251–258. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Price AL, Patterson NJ, Plenge RM, Weinblatt ME, Shadick NA, Reich D. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2006;38:904–909. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheverud JM. A simple correction for multiple comparisons in interval mapping genome scans. Heredity. 2001;87:52–58. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2540.2001.00901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newson R. Confidence intervals for rank statistics: Somers' D and extensions. Stata Journal. 2006;6:309–334. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB, Sr, Steyerberg EW. Extensions of net reclassification improvement calculations to measure usefulness of new biomarkers. Stat Med. 2011;30:11–21. doi: 10.1002/sim.4085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chambless LE, Cummiskey CP, Cui G. Several methods to assess improvement in risk prediction models: Extension to survival analysis. Stat Med. 2011;30:22–38. doi: 10.1002/sim.4026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Team RDC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Evans DM, Brion MJ, Paternoster L, Kemp JP, McMahon G, Munafò M, et al. Mining the human phenome using allelic scores that index biological intermediates. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003919. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hilt B, Langard S, Lund-Larsen PG, Lien JT. Previous asbestos exposure and smoking habits in the county of Telemark, Norway - A cross-sectional population study. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1986;12:561–566. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nordestgaard BG, Varbo A. Triglycerides and cardiovascular disease. Lancet. 2014;384:626–635. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61177-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.CARDIoGRAMplusC4D Consortium. Deloukas P, Kanoni S, Willenborg C, Farrall M, Assimes TL, et al. Large-scale association analysis identifies new risk loci for coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2013;45:25–33. doi: 10.1038/ng.2480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shapiro MD, Fazio S. From Lipids to Inflammation: New Approaches to Reducing Atherosclerotic Risk. Circ Res. 2016;118:732–749. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tall AR, Yvan-Charvet L. Cholesterol, inflammation and innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:104–116. doi: 10.1038/nri3793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alexander CM, Landsman PB, Teutsch SM, Haffner SM. NCEP-defined metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and prevalence of coronary heart disease among NHANES III participants age 50 years and older. Diabetes. 2003;52:1210–1214. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.5.1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilson PW, D'Agostino RB, Levy D, Belanger AM, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation. 1998;97:1837–1847. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.18.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yarnell JW, Patterson CC, Bainton D, Sweetnam PM. Is metabolic syndrome a discrete entity in the general population? Evidence from the Caerphilly and Speedwell population studies. Heart. 1998;79:248–252. doi: 10.1136/hrt.79.3.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sattar N, Gaw A, Scherbakova O, Ford I, O'Reilly DS, Haffner SM, et al. Metabolic syndrome with and without C-reactive protein as a predictor of coronary heart disease and diabetes in the West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study. Circulation. 2003;108:414–419. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000080897.52664.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stern MP, Williams K, González-Villalpando C, Hunt KJ, Haffner SM. Does the metabolic syndrome improve identification of individuals at risk of type 2 diabetes and/or cardiovascular disease? Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2676–2681. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.11.2676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Girman CJ, Rhodes T, Mercuri M, Pyörälä K, Kjekshus J, Pedersen TR, et al. The metabolic syndrome and risk of major coronary events in the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S) and the Air Force/Texas Coronary Atherosclerosis Prevention Study (AFCAPS/TexCAPS) Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:136–141. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McNeill AM, Rosamond WD, Girman CJ, Golden SH, Schmidt MI, East HE, et al. The metabolic syndrome and 11-year risk of incident cardiovascular disease in the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:385–390. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.2.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.