SUMMARY

A SNP (rs8004664) in the first intron of the FOXN3 gene is associated with human fasting blood glucose. We find that carriers of the risk allele have higher hepatic expression of the transcriptional repressor FOXN3. Rat Foxn3 protein and zebrafish foxn3 transcripts are downregulated during fasting, a process recapitulated in human HepG2 hepatoma cells. Transgenic overexpression of zebrafish foxn3 or human FOXN3 increases zebrafish hepatic gluconeogenic gene expression, whole-larval free glucose, and adult fasting blood glucose, and also decreases expression of glycolytic genes. Hepatic FOXN3 overexpression suppresses expression of mycb, whose ortholog MYC is known to directly stimulate expression of glucose-utilization enzymes. Carriers of the rs8004664 risk allele have decreased MYC transcript abundance. Human FOXN3 binds DNA sequences in the human FOXN3 and zebrafish mycb loci. We conclude that the rs8004664 risk allele drives excessive expression of FOXN3 during fasting and that FOXN3 regulates fasting blood glucose.

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 100 genes have been associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus, a common multi-organ disease marked by strong, but complex genetic propensity (Bonnefond and Froguel, 2015; Grarup et al., 2014). Most of the genes identified in such population-based studies that have been studied mechanistically appear to act primarily, albeit not exclusively, in the development, survival, and function of pancreatic β-cells (Bonnefond and Froguel, 2015; Grarup et al., 2014). Nevertheless, functional dissection of the contributions of individual genome-wide association study (GWAS) “hits” are lacking for the majority of identified associations (Sanghera and Blackett, 2012). Understanding how these population genetics-derived findings impact metabolic regulation holds the promise of developing more effective diagnostic and therapeutic tools.

Here we examine the basis for the statistically significant and independent association of the SNP rs8004664, which occurs in the first intron of human FOXN3, with altered fasting blood glucose (Manning et al., 2012). FOXN3 interacts with transcriptional repressors, and binds DNA through a highly conserved Forkhead box domain (Pati et al., 1997; Scott and Plon, 2005). We show that FOXN3 transcript and FOXN3 protein abundance are increased in primary hepatocytes from carriers of the rs8004664 risk allele. This risk-allele-linked increase in FOXN3 expression contrasts with the normal downregulation of Rat Foxn3 protein and zebrafish foxn3 transcripts during fasting, as well as the rapid decreases in human HepG2 hepatoma cell FOXN3 protein abundance in minimal medium. To test whether excessive FOXN3 protein modulates glucose metabolism, we prepared transgenic zebrafish lines overexpressing zebrafish foxn3 and human FOXN3. These lines show increased hepatic gluconeogenic gene expression, decreased hepatic glycolytic gene expression, increased whole-larval free glucose, and increased adult fasting blood glucose, all findings suggesting FOXN3 drives excessive glucose production. To understand the molecular basis of these findings, we examined the whole transcriptomes of transgenic animal livers, comparing them to non-transgenic animals. Hepatic FOXN3 overexpression suppresses expression of mycb, which encodes a MYC family transcription factor whose mouse and human orthologs are known to directly stimulate expression of multiple glucose-utilization enzymes. Carriers of the rs8004664 risk allele had decreased MYC transcript abundance, suggesting that FOXN3 might directly inhibit MYC expression. We found human FOXN3 precipitates DNA sequences within the human MYC and zebrafish mycb genes. We conclude that the rs8004664 risk allele drives inappropriate (excessive) expression of FOXN3 during fasting. We conclude FOXN3 is a pathological regulator of fasting blood glucose.

RESULTS

The rs8004664 Risk Allele Increase Expression of FOXN3

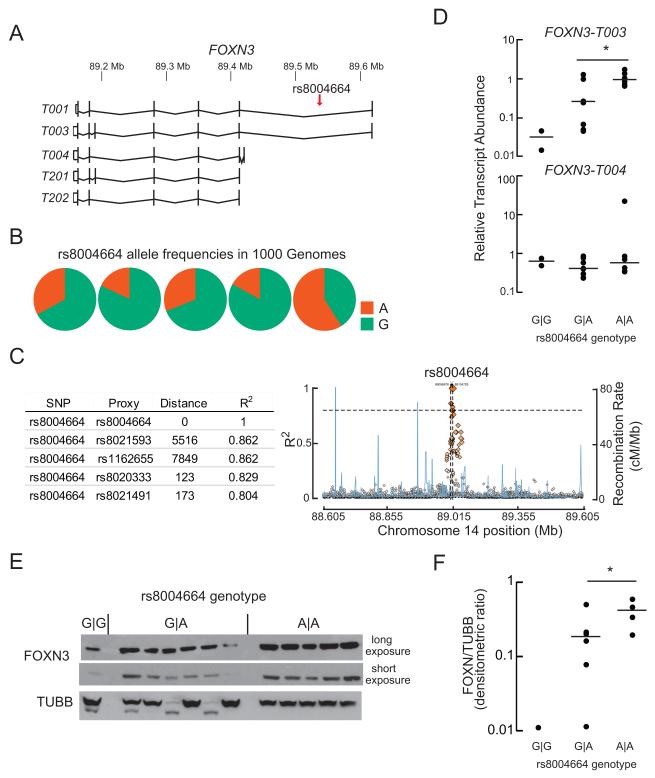

The rs8004664 SNP resides in the first, large intron of the FOXN3 gene, which has several annotated transcript variants (Figure 1A). The most-abundant transcript variant FOXN3–T003 encodes the full-length protein. Allele frequencies vary among populations, with an overall frequency in the 1000 Genomes database of the hyperglycemia risk allele of 30% (Figure 1B). Over a 100 kb interval flanking it, rs8004664 appears to be in linkage disequilibrium only with nearby (less than 8,000 bp) SNPs (Figure 1C and S1). This SNP does not appear to be in a recombination hot spot nor does it appear to be in an annotated transcription factor binding site (Motallebipour et al., 2009).

Figure 1. The rs8004664 risk allele increases FOXN3 gene expression.

(A) The 514.28kb FOXN3 locus is on the reverse strand of human chromosome 14. The -003 transcripts variant encodes the full-length protein. Four other major, protein-coding transcript variants are annotated in GENCODE 24. Note the location of rs8004664, within the first, large intron. Transcript variant -T001 encodes a 468-aminoacyl residue (aa) protein; -T003 encodes a 490 aminoacyl residue (aa) protein; -T004 encodes a 468aa protein; -T201 encodes a 490aa protein; and -T202 encodes a 468aa protein.

(B) Allele frequencies in the 1000 Genomes dataset. ‘A’ is the hyperglycemia risk allele. The overall minor (risk) allele frequency is 30%.

(C) The distance in base pairs of the nearest SNPs in linkage disequilibrium to rs8004664 are shown in the table (left). Linkage disequilibrium (R2 values) and recombination rate (cM/Mb) plots for the 10 kb flanking the rs8004664 are shown for the entire 1000 Genomes data set (plotted with SNAP). Note the chromosomal position of rs8004664 is different from that shown in A because different builds of the human genome were queried.

(D) Steady-state transcript abundance of FOXN3-T003 and -T004 in cryopreserved human hepatocytes from donors with the indicated rs8004664 genotypes, G∣G (n=2), A∣G (n=8), and A∣A (n=6). Horizontal lines indicate the median value. Transcript variants -T003 is the most abundant, followed by -T004. Mean ± s.e.m. values are shown. Ct = 26.9 ± 0.3 for –T003 and 31.7 ± 0.4 cycles for –T004. *P = 0.03; two-tailed Student’s t-test.

(E, F) Sufficient protein was retrieved from 12 of the 16 donor liver samples analyzed in panel D for immunoblot analysis. FOXN3 protein showed a similar trend as FOXN3 transcript, with increasing abundance proportional to the number of rs8004664 risk alleles present. Horizontal lines indicate the median value. *P = 0.06; two-tailed Student’s t-test. TUBB, β-Tubulin) See also Figure S1 and Table S1.

Query of The Human Protein Atlas (Uhlen et al., 2015), the largest repository of human immunohistochemical and RNA-seq data publically available, revealed human FOXN3 protein and mRNA are not detected in the pancreas, but are expressed in liver and renal tubules. These are both gluconeogenic organs that participate in maintaining fasting glucose levels. To determine if the rs8004664 SNP affects FOXN3 transcript abundance, we genotyped 16 primary human hepatocyte samples for the rs8004664 SNP (Table S1). Gene expression analysis showed that as compared to the protective allele (G), the rs8004664 risk allele (A) dose-dependently increased the abundance of the dominant FOXN3 transcript variant (–T003) by nearly two orders of magnitude, but did not alter the (far lower) expression of the next most abundant transcript variant FOXN3-T004 (Figure 1D and Table S1). The rs8004664 risk allele also increased FOXN3 protein expression (Figure 1D and 1E).

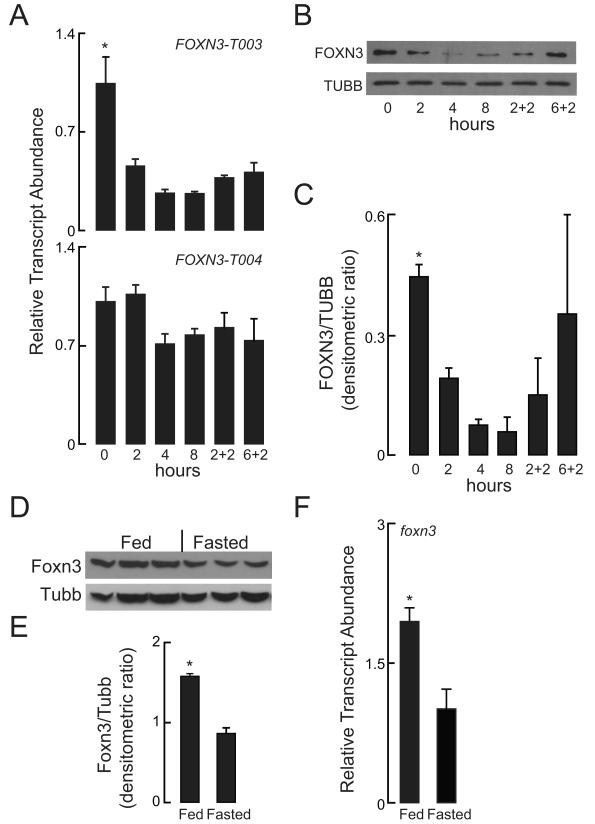

FOXN3 Is Normally Downregulated in Fasting

In order to determine whether FOXN3 is metabolically regulated, changes in gene regulation in response to glucose were measured by assessing FOXN3 transcript and FOXN3 protein abundance in human HepG2 hepatoma cells, which are homozygous for the rs8004664 protective allele (Motallebipour et al., 2009). Within 2 hours of switching HepG2 cells from a complete medium to a minimal medium (low glucose, no serum), FOXN3-T003 transcript and FOXN3 protein abundance decreased, while the far-lower abundance FOXN3-T004 transcript did not (Figure 2A). Furthermore, the acute restoration of complete medium increased FOXN3 protein abundance to a greater degree than it did FOXN3-T003 transcript abundance (Figure 2B and 2C). Supporting these findings of acute metabolic regulation of FOXN3 transcript abundance, we observed that Foxn3 protein content was increased in livers of fed rats as compared to livers of fasted rats (Figure 2D and 2E). Likewise, we found that the livers of fasted adult zebrafish had decreased foxn3 transcript abundance than the livers of fed adult zebrafish (Figure 2F).

Figure 2. FOXN3 Is Nutritionally Regulated.

(A) HepG2 cells were grown in complete medium (0 hours) and then subjected to nutrient deprivation for the indicated times (all in hours). Where indicated, samples were returned to complete medium for the indicated time (‘+’), RT-PCR was performed to measure FOXN3-T003 and FOXN3-T004 transcript abundance. Mean ± s. e. m. values are shown. * P <0.001; one way ANOVA.

(B, C) Immunoblot analysis and densitometric analysis was performed for human FOXN3 and TUBB at the times indicated in panel A. Mean ± s. e. m. values are shown. P = 0.06 in one-way ANOVA.

(D, E) Foxn3 protein abundance was quantified with immunoblot analysis of liver homogenates from fed and fasted rat livers. Mean ± s. e. m. values are shown. *P = 0.0007; two-tailed Student’s t-test.

(F) foxn3 transcript abundance was measured in fed and fasted adult zebrafish livers. Mean ± s.e.m. values are shown. *P < 0.004; two-tailed Student’s t-test.

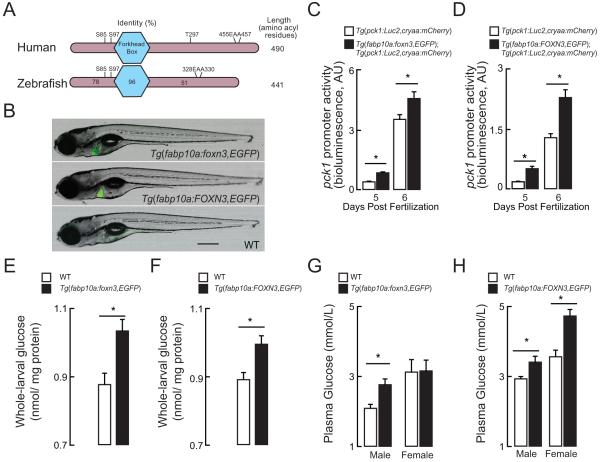

FOXN3 Overexpression Drives Hepatic Glucose Production

Zebrafish Foxn3 shares strong sequence homology to human FOXN3 (Figure 3A). Beyond this narrow primary structure conservation, zebrafish models for studying glucose metabolism have emerged as a powerful approach to answering mechanistic questions relating to physiology and gene regulation (Schlegel and Gut, 2015) . Thus, we generated two transgenic zebrafish lines expressing the zebrafish foxn3 and human FOXN3 under the control of the constitutively active, liver-specific fabp10a promoter. The transgenic constructs contained the “liberated” P2A-EGFP tag (Provost et al., 2007), which allowed us to identify carriers readily (Figure 3B). Both the Tg(fabp10a:foxn3,EGFP)z106 and the Tg(fabp10a:FOXN3,EGFP)z107 transgenic lines were crossed to the Tg(pck1:Luc2;cryaa:mCherry)s952 transgenic reporter line, which carries a cDNA encoding Luciferase 2 under the control of zebrafish phosphoenylpyruvate carboxykinase 1 promoter sequences (Gut et al., 2013). Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1 is a rate-limiting enzyme of gluconeogenesis whose expression is strongly induced by in fasting zebrafish liver; the Tg(pck1:Luc2,cryaa:mCherry)s952 transgenic reporter line serves as an in vivo gauge of gluconeogenic gene expression through whole-larval extract Luciferase assays (Gut et al., 2013). Both Tg(fabp10a:foxn3,EGFP)z106; Tg(pck1:Luc2,cryaa:mCherry)s952 and Tg(fabp10a:FOXN3,EGFP)z107; Tg(pck1:Luc2,cryaa:mCherry)s952 transgenic lines showed increased Luciferase activity when compared to the Tg(pck1:Luc2,cryaa:mCherry)s952 line in never-fed larvae at points in development when pck1 activity is normally induced (Figure 3C and 3D).

Figure 3. FOXN3 drives increased hepatic glucose production.

(A) Human FOXN3 and zebrafish Foxn3 orthologs are shown with the central DNA-binding Forkhead Box (nearly invariant amino-acyl residues 112-204) and length marked (to the right). The percent identity of the zebrafish amino-terminus, Forkhead Box and carboxy-terminus relative to human FOXN3 is shown. The conserved Sin3-binding signature (EAA within the carboxy-terminus) is marked. Putative phosphorylation sites found in five or more published phospho-proteomic surveys are shown, as well: the significance of these residues’ phosphorylation has not been established in any organism.

(B) A non-transgenic (wild-type, WT) 7 days post-fertilization larva and two transgenic larvae were photographed in light- and green fluorescent channels in the left-lateral view. The Tg(fabp10a:foxn3,EGFP)z106 transgenic line over-expresses zebrafish foxn3 and EGFP and the Tg(fabp10a:FOXN3,EGFP)z107 transgenic line over-expresses human FOXN3 and EGFP (transcript variant –T003). The encoded EGFP protein is translated as a free (not as a fusion) protein (Provost et al., 2007). Bar 500 μm.

(C, D) pck1 promoter activity (bioluminescence derived from assay of Luciferase; AU, arbitrary units) in lysates prepared from 5 and 6 days post-fertilization (dpf), never-fed Tg(pck1:Luc2,cryaa:mCherry)s952, Tg(fabp10a: foxn3,EGFP)z106; Tg(pck1:Luc2,cryaa:mCherry)s952 and Tg(fabp10a:FOXN3,EGFP)z107; and Tg(pck1:Luc2,cryaa:mCherry)s952 larvae. P <0.02; two-tailed Student’s t-test. n = 5-7.

(E,F) Whole body glucose levels in 6 dpf wild-type (WT), Tg(fabp10a: foxn3,EGFP)z106 and Tg(fabp10a:FOXN3,EGFP)z107larval extracts. *P < 0.02; two-tailed Student’s t-test. n = 4-5 pooled samples of 10 larvae each. All values are mean ± s. e. m.

(G, H), Fasting blood glucose levels in WT, Tg(fabp10a: foxn3,EGFP)z106 and Tg(fabp10a:FOXN3,EGFP)z107 transgenic adult animals of both sexes after an overnight fast.*P = 0.01; 2-tailed t Student’s t-test. n = 9-13.

Paralleling this increase in gluconeogenic transcriptional reporter activity, we observed that whole-larval free glucose levels, which exclusively reflect newly synthesized glucose levels in this model (Jurczyk et al., 2011), were higher in both Tg(fabp10a:foxn3,EGFP)z106 and Tg(fabp10a:FOXN3,EGFP)z107 transgenic larvae than in non-transgenic (wildtype [WT]) controls (Figure 3E and 3F). Third, fasting blood glucose was increased in both Tg(fabp10a:foxn3,EGFP)z106 and Tg(fabp10a:FOXN3,EGFP)z107 transgenic adults compared to WT controls, except in females overexpressing the zebrafish foxn3 ortholog (Figure 3G and 3H). Collectively, these results indicate that FOXN3 overexpression increases blood glucose through driving enhanced liver glucose production.

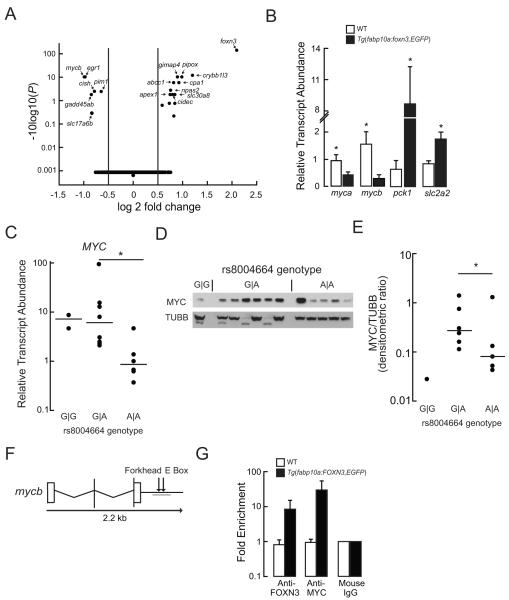

FOXN3 Suppresses Expression of MYC

Previous work in cell culture established a role for FOXN3 as a transcriptional repressor (Pati et al., 1997; Samaan et al., 2010; Schuff et al., 2007; Scott and Plon, 2005). Specifically, human FOXN3 and Xenopus Foxn3 bind the histone deacetylase complex (HDACs) component Sin3 using a glutamyl-alanyl-alanyl (EAA) carboxy terminal motif that is conserved in zebrafish Foxn3 (Figure 3A). Xenopus Foxn3 also binds the HDAC class I catalytic subunit Rpd3 via its N-terminal 135 aminoacyl residues, a region conserved highly among vertebrate FOXN3 ortholog (Schuff et al., 2007). HDACs repress gene transcription by remodeling chromatin. Thus, we posited that Foxn3 directs HDAC activity to genes controlling liver glucose metabolism.

To get a global view of the gene regulatory changes caused by Foxn3, we performed whole transcriptome (RNA-seq) analysis on livers dissected from WT and Tg(fabp10a:foxn3,EGFP)z106 transgenic animals, analyzing the data with DESeq2 (Anders and Huber, 2010). The most-upregulated gene in Tg(fabp10a:foxn3,EGFP)z106 transgenic livers was the transgene itself (Figure 4A). The most-downregulated transcript in Tg(fabp10a:foxn3,EGFP)z106 transgenic animals was mycb, encoding Mycb, a transcription factor whose human and mouse orthologs are known to regulate expression of multiple glycolytic enzymes (Kim et al., 2004; Peterson and Ayer, 2011). Overexpression of Myc in mouse liver causes a 25% decrease fasting blood glucose via coordinated modulation of glycolytic and gluconeogenic gene expression (Kim et al., 2004; Morrish et al., 2009; Osthus et al., 2000; Peterson and Ayer, 2011; Valera et al., 1995). Using RT-PCR, we confirmed the RNA-seq- detected down-regulation of myca and mycb, and up-regulation of pck1 transcript abundance in Tg(fabp10a:foxn3,EGFP)z106 transgenic animals (Figure 4B). Similar to pck1 induction, we found the transcript for the liver glucose exporter Slc2a2 (Glut2) to be induced in Tg(fabp10a:foxn3,EGFP) transgenic animals (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. FOXN3 Suppresses MYC Expression.

(A) Volcano plot of differentially expressed transcripts from the RNA pools (n = 3) extracted from the livers of never-fed WT and Tg(fabp10a: foxn3,EGFP)z106 larvae. Note the adjusted P values are plotted on a log base 10 scale, with higher values indicating increased significance.

(B) Quantitative PCR validation of the indicated mRNA steady state levels in the livers of WT and Tg(fabp10a: foxn3,EGFP)z106 adult livers. Mean ± s. e. m. values are shown. *P <0.05; two-tailed Student’s t-test (n = 5). slc2a2, solute carrier family 2 (facilitated glucose transporter), member 2.

(C) MYC transcript abundance in cryopreserved human hepatocytes. Horizontal lines indicate the median value. *P <0.05; two-tailed Student’s t-test.

(D, E) The membrane shown in Figure 1E was immunoblotted with anti-MYC IgG and the density of the MYC band was normalized to the TUBB band densities; this is the same blot as in Figure 1E. Horizontal lines indicate the median value. *P = 0.019 by Mann-Whitney Rank Sum Test after excluding an outlier (determined using the Grub’s test) from the A∣A genotype values.

(F) Structure of the zebrafish mycb gene. A Forkhead binding site and a MYC binding site (E box) are located distal to the 3′-UTR. The target PCR product for the ChIP assay is underlined.

(G) Quantitative PCR analysis following ChIP with the indicated antibodies was performed in WT and Tg(fabp10a:FOXN3,EGFP)z107 livers. Fold enrichment was calculated relative to the mouse IgG levels. Mean ± s. e. m. values are shown. See also Table S1 and Figure S2.

The gene expression changes seen in Tg(fabp10a:foxn3,EGFP)z106 transgenic animals suggested that FOXN3 may regulate fasting glucose metabolism by inducing gluconeogenic gene expression and by repressing MYC-driven glycolysis. Indeed, MYC protein is briefly induced when HepG2 cells are placed in low glucose medium, partially mirroring the down-regulation of FOXN3 seen under these conditions (Figure 2B, 2C, S2A and S2B). Thus, we measured the MYC transcript abundance in our panel of primary human hepatocyte samples. The rs8004664 risk allele was gene dose dependently associated with lower MYC transcript abundance (Figure 4C and Table S1). Immunoblot analysis of the 12 primary human hepatocytes examined in Figure 1E and 1F revealed that the rs8004664 dose dependently decreased MYC protein abundance (Figure 4D and 4E).

Next we assessed whether FOXN3 directly regulates MYC expression. We found a putative Forkhead binding site distal to the 3′UTR of human MYC, near the MYC-binding site (E-Box) annotated in the ENCODE and JASPAR databases (Figure S2C). Anti-FOXN3 immunoglobulin Gs specifically immunoprecipitated chromatin (ChIP) containing the Forkhead-binding sequences from HepG2 cells, suggesting that FOXN3 may regulate MYC expression via binding to sequences distal to the 3′UTR of MYC (Figure S2D and S2E). A similar arrangement of putative Forkhead binding site and E-Box was found distal to the 3′-UTR of zebrafish mycb (Figure 4F and S4F). Compared to WT animals, we found that Tg(fabp10a:FOXN3,EGFP)z107 transgenic animals showed increased binding of both of these DNA elements by FOXN3 and endogenous Myc proteins (Figure 4G).

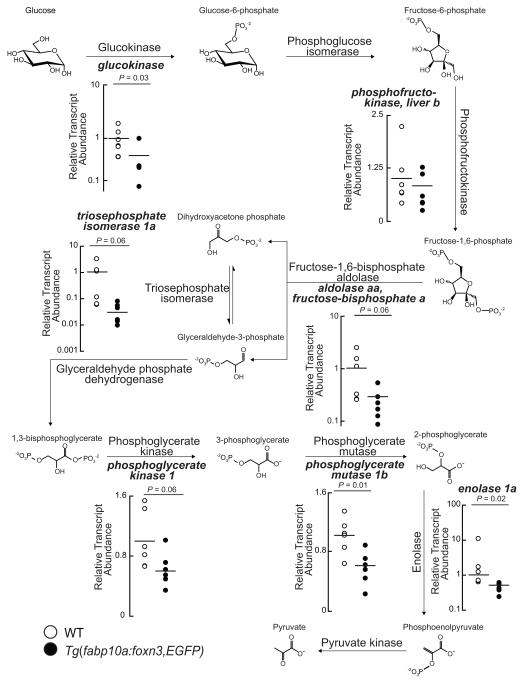

FOXN3 Overexpression suppresses glycolytic gene expression

In mouse livers overexpression of MYC induces the glycolytic transcripts Slc2a3, which encodes Glucose transporter 1; Gpi1, encoding Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase 1; and Pfk1, which encodes Phosphofructokinase 1 (Osthus et al., 2000). Further, Myc directly transactivates Slc2a1, Pfk1, Eno1 (Osthus et al., 2000). We posited that over-expression of FOXN3 in zebrafish livers would suppress expression of MYC glycolytic targets, and tested the model by measuring the abundance of glycolytic transcripts in fasted WT and transgenic livers. Adult Tg(fabp10a:foxn3,EGFP)z106 transgenic livers showed decreased expression of multiple glycolytic transcripts, including orthologs of the mouse direct Myc targets phosphofructokinase, and enolase 1. Additionally, glucokinase and phosphoglycerate mutase 1b transcripts were significantly decreases in Tg(fabp10a:foxn3,EGFP)z106 transgenic livers, and triosephosphate isomerase 1a and phosphoglycerate kinase 1 were nearly significantly decreased in Tg(fabp10a:foxn3,EGFP)z106 transgenic livers (Figure 5).

Figure 5. FOXN3 over-expression suppresses glycolytic gene expression.

Quantitative PCR analysis of the indicated transcripts encoding glycolytic enzymes in WT and Tg(fabp10a:foxn3,EGFP)z106 livers. Horizontal lines indicate the mean value. Two-tailed Student’s t-test results are shown. See also Figure S3.

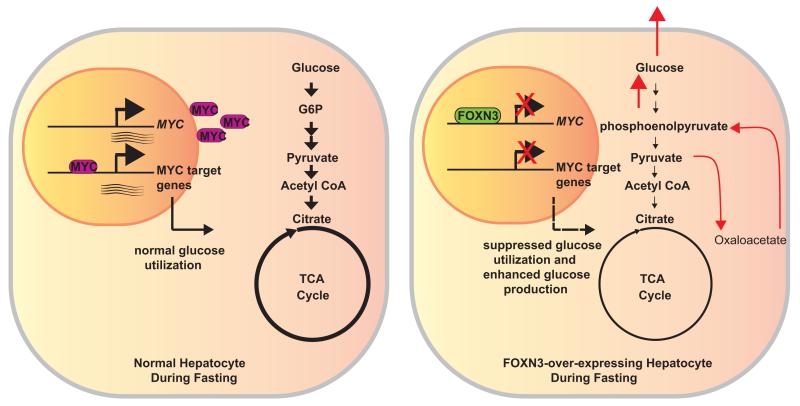

While the nutritional status of the primary human hepatocyte donors was not known at the time of death, we examined the abundance of glycolytic and gluconeogenic transcripts in these samples (Figure S3). ENOLASE 1 and TRIOSEPHOSPHATE ISOMERASE transcripts showed non-significant trends toward decreased transcript abundance in homozygous carriers of the rs8004664 SNP. PHOSPHOGLYCERATE MUTASE and PHOSPHOGLYCERATE KINASE transcript abundance was significantly decreased expression in homozygous carriers of the rs8004664 risk allelle. Curiously, PFK1 transcript abundance was highest in homozygous carriers of the rs8004664 risk allele. Finally, we found that PCK1 and GLUCOSE-6-PHOSPHATASE, CATALYTIC transcripts were not associated with the rs8004664 genotype. Collectively, these results indicate that Foxn3 suppresses hepatic glucose utilization, in large part, through downregulating the glycolytic program driven by Myc (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Model for how FOXN3 suppresses MYC transcription, and blunts hepatic glucose utilization.

During the fasted state (left), normally reduced FOXN3 expression allows for increased MYC expression. MYC regulates the expression of numerous genes encoding enzymes of glycolytic and tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle flux in hepatocytes thereby promoting net hepatic glucose utilization during the fasted state. Conversely, during the fed state or when over-expressed in hepatocytes either transgenically or through the rs8004664 risk allele’s direction (right), increased FOXN3 represses MYC gene expression, leading to reduced glycolytic gene expression and flux through glycolysis and the TCA cycle decrease (noted by altered weight of arrows and circle). In parallel, gluconeogenesis is induced by FOXN3, as noted with red arrows for the hypothesized route of carbon atoms. The net effect of increased FOXN3 expression and reduced MYC expression is increased hepatic glucose production, leading to pathologically increased blood glucose concentrations.

DISCUSSION

The Drosophila mutant forkhead (fkh) was the first “terminal” homeotic (body plan-controlling) mutant identified. In contrast to the more centrally acting homeotic mutants in the Antennapedia and Bithorax complexes, which control “core” body segment planning (i.e., head, thorax, abdomen), fkh is a master regulator of development of the extreme anterior and extreme posterior of the body. Loss of fkh function gives rise to ectopic head structures in the head and loss of tail regions that derive from primordial gut cells (Jürgens and Weigel, 1988; Weigel et al., 1989). The Fkh protein has a signature, approximately 100 aminoacyl residue long, DNA-binding domain called the Forkhead Box (FOX) that is highly conserved in higher-vertebrate orthologs. There are 50 Fox family members in humans (Hannenhalli and Kaestner, 2009). Similar to Drosophila Fkh, mouse FOXA family members (formerly Hepatocyte Nuclear Factors 1, 2 and 3) are specific regulators of the development, cell architecture, and function of another “terminal” structure, namely the liver (Lai et al., 1991). Since the discovery of fkh and its mammalian orthologs, numerous paralogs have been identified in vertebrates, with Mendelian diseases including familial cancer syndromes, immune deficiencies, glaucoma and speech disorders being caused by mutations in human FOX genes (Hannenhalli and Kaestner, 2009). Several FOX family members have “neo-functionalized” in higher vertebrates to govern specific aspects of metabolism (Benayoun et al., 2011; Le Lay and Kaestner, 2010). For instance, FOXO is firmly established as a master regulator of hepatic glucose production. FOXO nuclear localization and transcriptional activity are directly inhibited by insulin signaling, through phosphorylation of FOXO by the insulin-effector kinase Akt; conversely, c-Jun-catalyzed phosphorylation of other sites induces FOXO nuclear localization and activation (Pajvani and Accili, 2015).

Human FOXN3 was identified in a high-copy suppressor screen of budding yeast checkpoint mutants (Pati et al., 1997). Checkpoint suppressor 1 (Ches1), the first suppressor identified in this screen encodes FOXN3; and the protein interacts with transcriptional repressive machinery (Scott and Plon, 2005). Notably, FOXN3 suppresses the transcriptional activity of the MENIN transcription factor, whose encoding gene sustains dominant-activating mutations in the Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia, Type 1 syndrome (Busygina et al., 2006). Since both Xenopus embryos injected with anti-foxn3 morpholino oligonucleotides and Foxn3−/− mice die at early stages as a result of craniofacial defects (Samaan et al., 2010; Schuff et al., 2007), the role of FOXN3 in adult metabolism was not explored previously in either gain- or loss-of-function models.

We observed that hepatocyte FOXN3 transcript abundance is nutritionally regulated (normally induced by nutrient sufficiency), and that the risk allele of rs8004664 associated with elevated fasting human blood glucose is also associated with higher FOXN3 transcript and protein abundance in primary human hepatocytes. Second, we found that over-expression of both zebrafish foxn3 and human FOXN3 in zebrafish livers increases gluconeogenic gene expression, larval free glucose levels, and fasting blood glucose levels in adults when fed their normal diets. Third, we found FOXN3 binds DNA regulatory sequence of the glucose-utilization factor human MYC, and observed enriched binding to the orthologous Forkhead box in the zebrafish mycb gene in intact livers; both results suggesting that FOXN3 represses MYC expression. Fourth, we found that FOXN3 overexpression suppresses expression of glycolytic gene transcripts, many of which are under direct transcriptional control by MYC (Osthus et al., 2000).

While we found a robust and direct suppressive role for FOXN3 in regulating MYC expression in our zebrafish model based on the inverse association of FOXN3 and MYC transcripts in the 16 samples we obtained from commercial vendors, lack of information regarding the nutritional status of these donors (whether they received intravenous glucose or parenteral nutrition at the time of death is not known) makes interpretation of the select glycolytic and gluconeogenic transcripts difficult. Some transcripts show the expected association with the rs8004664 risk allele, while others do not. In future studies larger cohorts of more carefully phenotyped primary human hepatocyte samples should be examined. Relatedly, the mechanisms through which FOXN3 induces gluconeogenic expression merit additional investigation. Specifically, it will be important to determine what transcriptional programs are being modulated by FOXN3 to allow for coordinated induction of gluconeogenesis and suppression of glucose utilization. Factors other than MYC are likely to be implicated in these processes.

Another open question that greater numbers of more thoroughly characterized human samples will allow us to address is the molecular basis for the rs8004664 risk allele’s association with greater FOXN3 expression. While we did not find an annotated transcription factor binding site in this locus in the ENCODE data set (Motallebipour et al., 2009), it is formally possible that this SNP reflects differential transcription factor binding in a linked region (Claussnitzer et al., 2015). Furthermore, it is conceivable that this locus regulates FOXN3 transcription initiation, for example, by dictating preferential CpG island methylation (Dayeh et al., 2014; Deaton and Bird, 2011). Likewise, pre-mRNA stability or splicing might be affected by the rs8004664 risk allele.

Related to these molecular concerns, our findings in liver do not exclude the possibility of other functions for FOXN3 in regulating metabolism in other organs, particularly the kidney, where the protein was detected in a systematic human immunohistochemical survey (Uhlen et al., 2015). Indeed, by analogy to the most strongly associated diabetes gene TCF7L2, it is quite likely that extra-hepatic functions of FOXN3 in regulating aspects of glucose homeostasis exist (Boj et al., 2012; Dayeh et al., 2014; Grant et al., 2006; Lyssenko et al., 2007; van Es et al., 2012; van Vliet-Ostaptchouk et al., 2007). Preparation of conditional loss-of-function and inducible gain-of-function foxn3 alleles will allow dissection of the role(s) of this factor in other organs. Moreover, this approach will allow us to examine MYC-independent FOXN3 functions in regulating metabolism.

The interface between regulation of hepatic intermediary metabolism and neoplastic transformation also merits further exploration in light of our study. Human hepatocellular carcinoma relies on MYC gene amplification as a major driver of growth (Kaposi-Novak et al., 2009). Overexpression of MYC in the livers of mice is sufficient to cause hepatocellular carcinoma (Murakami et al., 1993; Sandgren et al., 1989; Wu et al., 2002); this pathological event is recapitulated in zebrafish over-expressing mouse Myc in an inducible manner (Li et al., 2013). Conversely, even brief inactivation of MYC is sufficient to restore normal cell fate in mouse models of hepatocellular carcinoma (Shachaf et al., 2004) and sarcoma (Jain et al., 2002). Most likely, FOXN3’s regulation of MYC targets also serves to dampen MYC-driven hepatocyte proliferation. This hypothesis will require similar genetic strategies to those needed to assess the role of FOXN3 outside the liver.

Finally, future work will seek to establish the acute nutritional and hormonal cues that regulate FOXN3 protein function, including those factors that regulate its (potential) phosphorylation, nucleo-cytoplasmic trafficking, and protein-protein interactions. Such knowledge may reveal the interaction of this factor with known signaling pathways that regulate hepatocyte function. Similarly, comprehensive evaluation of FOXN3’s direct and indirect targets might disclose potentially druggable targets to treat type 2 diabetes mellitus.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cryopreserved Human Hepatocytes

Cryopreserved human hepatocytes were purchased from Zen-Bio (ZBH) and Triangle Research Labs (HUM) (both in Research Triangle Park, NC). The lot numbers, phenotypes, and genotypes of individual samples are listed in Table S1. Hepatocytes were thawed and aliquoted for RNA, DNA and protein extraction.

Zebrafish Fasting Studies and Blood Chemistry

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Utah approved all studies. Three-month old fish were fed standard zebrafish diets supplemented with brine shrimp. Animals were housed at 28°C, and exposed to 14 hours light and 10 hours of darkness per day. Thirty minutes after lights were turned on each morning, fish were euthanized by immersing in ice water (Wilson et al., 2009) and blood was drawn from the caudal vein. Blood glucose levels were measured using a glucose meter (Contour, Bayer). Livers were harvested, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

Generation of Transgenic Fish

Tol2 transposon-mediated transgenesis was used to generate the Tg(fapb10a:foxn3,EGFP)z106 and Tg(fapb10a:FOXN3,EGFP)z107 (Kwan et al., 2007). Three founders were recovered for both the transgenic lines and all the lines had equally bright EGFP fluorescence. Single integration was evidenced by the 50% Mendelian ratio of carriers obtained after outcrossing the founders with the wild-type strain WIK. The primers used to generate the Gateway entry clones are listed in the Table S2. The fabp10a promoter that drives liver-specific expression was described previously (Her et al., 2003).

Cell Culture

HepG2 cells were purchased from ATCC and grown in Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics. For the serum depravation experiments, cells were grown in complete medium for 48 hours and then deprived of serum as indicated.

Rat Fasting Study

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Utah approved all studies. Eight-month old male rats were fed a standard chow diet (Harlan Teklad TD.8640, Madison, WI). Where indicated they were fasted for 15 hours prior to treatment with isoflurane anesthesia and cervical dislocation. Livers were harvested, quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

Immunoblotting

Cryopreserved hepatocytes, HepG2 cells or livers were sonicated in 400 μL RIPA buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche Complete MINI and PhosSTOP). Protein concentration was determined using the bicinchoninic acid method (Pierce, ThermoFisher Scientific). Fifteen to 30 μg of protein from each lysate was separated by SDS-PAGE using precast Tris-Glycine (Bio-Rad) or Bis-Tris (Thermofisher) gels, transferred to nitrocellulose or PVDF membranes and detected with commercially available antibodies. The antibodies used were anti-FOXN3 from Abgent (AP19255B); anti-β-Tubulin (TUBB) from Abcam (ab6046); and anti-c-Myc (clone 9E10) from Thermofisher. ImageJ was used to quantify the relative density of protein bands. Following exposure, X-ray films of immunoblots were scanned. The images were inverted, and the raw integral density was quantified for each band. Then the raw integral density of each FOXN3 or c-MYC band was divided by the raw integral density of the corresponding TUBB band.

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and quantitative PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cryopreserved hepatocytes, HepG2 cells or rat livers using a standard TRIzol method (Thermofisher). mRNA in 2 μg of total RNA was converted to cDNA using oligo(dT) primer and random hexamers according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Clontech EcoDry Premix). The primers for all the measured transcripts are listed in Table S2. To measure the steady-state mRNA abundance of MYC transcript, we used a predesigned assay (Hs.PT.58.26770695, Integrated DNA Technologies). For thermal cycling and fluorescence detection, an Agilent Technologies Stratagene MX 3000P machine was used (Genomics Core Facility, University of Utah). The threshold (Ct) values of fluorescence for each readout was normalized to corresponding Ct values from ef1a (zebrafish liver), HMBS (HepG2 cells) and HMBS (cryopreserved human hepatocytes) and fold change was calculated using the ΔΔCt method (Pfaffl, 2001).

DNA isolation, PCR and genotyping

Following TRIzol RNA extraction, DNA was precipitated from the remaining interphase and phenol phase following manufacturer’s instructions (Thermofisher). DNA was precipitated with ethanol, and the resulting pellet was washed with 0.1 M sodium citrate and 75% ethanol. DNA was resuspended in 8 mM NaOH. Twenty ng of DNA was used as template in a PCR reaction to amplify a 257 bp product surrounding the rs8004664 SNP. The PCR products were extracted from an agarose gel after electrophoresis, purified and Sanger sequenced.

RNA-Seq Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from 6 pools of approximately 30 livers dissected from 7 dpf Tg(fapb10a:foxn3,EGFP)z106 and non-transgenic siblings using a DirectZol RNA miniprep kit (Zymo Research). Isolated RNA was run on a Bioanalyzer 2100 Nano Chip (Agilent) to confirm RNA quantity and quality. Illumina TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Sample Prep Kit was used to prepare the library. Samples were barcoded as Transgenic versus wild-type and single-end 50-bp reads were generated on a Hiseq 2000 machine. Analysis was performed as described previously (Hill et al., 2013). Reads were aligned to the genome using NovoAlign version 3.02.07 and a custom index created using the Zv9 genome build, including unassigned scaffolds, and annotated splice junctions generated by the MakeTranscriptome command in the USeq package (version 8.7.0). Splice junction reads were then converted to genomic coordinates using the SamTranscriptomeParser command in USeq and assigned to genes using the Rsubread package for the R programming language (Liao et al., 2013) and the Ensembl RNA annotation. Differential gene expression analysis was performed on the resulting count table using DESeq2 (Love et al., 2014).

In vivo Luciferase reporter assay

Luciferase reporter assays were carried out as described previously (Gut et al., 2013). Heterozygous carriers of Tg(pck1:Luc2,cryaa:mCherry)s952 were crossed to heterozygous carriers of Tg(fapb10a:foxn3,EGFP)z106 and Tg(fapb10a:FOXN3,EGFP)z107. Larvae carrying both transgenes (as scored by green fluorescent livers and red fluorescent eyes) and control larvae Tg(pck1:Luc2,cryaa:mCherry)s952 (red fluorescent eyes only) were selected. Four larvae from each group were placed in a single well of a 96 well, opaque white microplate (Perkin Elmer), and anesthetized with Tricaine. One hundred microliters of Steady-Glo luciferase assay solution (Promega) was added to disintegrate the larvae and solubilize Luciferase. The plates were incubated for 30 minutes, and a plate reader (BioTek) was used to measure luminescence.

Total Whole Body Glucose in Larvae

A colorimetry based enzymatic detection kit (Biovision) was used to measure the total whole body glucose in larvae (Jurczyk et al., 2011). Four replicate pools of 10 larvae were homogenized using a sonicator and centrifuged. The supernatant was collected and used for measuring glucose and protein.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

Chromatin for ChIP was prepared by fixing HepG2 cells and zebrafish livers in 1% formaldehyde for 12 minutes followed by quenching with 0.125 M glycine for 5 minutes. A previously described protocol for the ChIP assays for Myc was followed (Barrilleaux et al., 2013). Briefly 5 to 6 ×106 fixed HepG2 cells or 50 mg of fixed zebrafish liver were lysed in the cell lysis buffer and centrifuged to collect the pelleted nuclear fraction, which was then lysed in nuclear lysis buffer using sonication. Reactions were performed using 3 μg of anti-FOXN3 or anti-MYC IgGs and 20 μL of Protein G magnetic beads (Thermofisher). Washes were performed using IP wash buffers and the resulting DNA was purified using Bioneer PCR clean up kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. ChIP experiments were repeated in triplicate. Five ng of DNA was used as a template in the quantitative PCR reactions. Primers are listed in Table S2.

Data and Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed with SigmaPlot 13 (Systat Software). Data displayed are mean ± s.e.m. Pairwise comparisons between groups (for example, WT versus transgenic) were made using paired or unpaired Student’s t-tests, as appropriate. For time series or multiple group comparisons, one-way ANOVA was used, as appropriate. Unless otherwise indicated, P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health (K08DK078605 and R01DK096710 to A.S., and UM1HL098160 to H.J.Y), and funds from the University of Utah Diabetes and Metabolism Center (A.S.), the University of Utah Molecular Medicine Program (A.S.) and the Department of Internal Medicine, University of Utah School of Medicine (A.S.). We thank Philipp Gut and Didier Y.R. Stainier for sharing the pck1 reporter strain, Kristen Kwan for sharing reagents and Simon J. Fisher for comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

ACCESSION NUMBERS

The accession number for the RNA-Seq data reported in this study is GEO: GSE80003.

Supplemental Information includes three figures, two tables, and three references.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, S.K. and A.S.; Methodology, S.K., E.K.Z., J.T.H; Investigation S.K., E.K.Z., J.T.H, A.S.; Writing – Original Draft, S.K. and A.S.; Writing – Reviewing & Editing, S.K., E.K.Z., J.T.H., H.J.Y. and A.S.; Funding Acquisition H.J.Y. and A.S.; Resources, S.K., J.T.H., H.J.Y. and A.S.; Supervision, A.S.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrilleaux BL, Cotterman R, Knoepfler PS. Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays for Myc and N-Myc. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;1012:117–133. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-429-6_9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benayoun BA, Caburet S, Veitia RA. Forkhead transcription factors: key players in health and disease. Trends Genet. 2011;27:224–232. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boj SF, van Es JH, Huch M, Li VS, Jose A, Hatzis P, Mokry M, Haegebarth A, van den Born M, Chambon P, et al. Diabetes risk gene and Wnt effector Tcf7l2/TCF4 controls hepatic response to perinatal and adult metabolic demand. Cell. 2012;151:1595–1607. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnefond A, Froguel P. Rare and common genetic events in type 2 diabetes: what should biologists know? Cell Metab. 2015;21:357–368. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busygina V, Kottemann MC, Scott KL, Plon SE, Bale AE. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 interacts with forkhead transcription factor CHES1 in DNA damage response. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8397–8403. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claussnitzer M, Dankel SN, Kim K-H, Quon G, Meuleman W, Haugen C, Glunk V, Sousa IS, Beaudry JL, Puviindran V, et al. FTO obesity variant circuitry and adipocyte browning in humans. New Engl J Med. 2015;373:895–907. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1502214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayeh T, Volkov P, Salo S, Hall E, Nilsson E, Olsson AH, Kirkpatrick CL, Wollheim CB, Eliasson L, Ronn T, et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis of human pancreatic islets from type 2 diabetic and non-diabetic donors identifies candidate genes that influence insulin secretion. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004160. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deaton AM, Bird A. CpG islands and the regulation of transcription. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1010–1022. doi: 10.1101/gad.2037511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant SF, Thorleifsson G, Reynisdottir I, Benediktsson R, Manolescu A, Sainz J, Helgason A, Stefansson H, Emilsson V, Helgadottir A, et al. Variant of transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCF7L2) gene confers risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2006;38:320–323. doi: 10.1038/ng1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grarup N, Sandholt CH, Hansen T, Pedersen O. Genetic susceptibility to type 2 diabetes and obesity: from genome-wide association studies to rare variants and beyond. Diabetologia. 2014;57:1528–1541. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3270-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gut P, Baeza-Raja B, Andersson O, Hasenkamp L, Hsiao J, Hesselson D, Akassoglou K, Verdin E, Hirschey MD, Stainier DYR. Whole-organism screening for gluconeogenesis identifies activators of fasting metabolism. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9:97–104. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannenhalli S, Kaestner KH. The evolution of Fox genes and their role in development and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:233–240. doi: 10.1038/nrg2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Her GM, Chiang C-C, Chen W-Y, Wu J-L. In vivo studies of liver-type fatty acid binding protein (L-FABP) gene expression in liver of transgenic zebrafish (Danio rerio) FEBS Lett. 2003;538:125–133. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00157-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JT, Demarest BL, Bisgrove BW, Gorsi B, Su YC, Yost HJ. MMAPPR: mutation mapping analysis pipeline for pooled RNA-seq. Genome Res. 2013;23:687–697. doi: 10.1101/gr.146936.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain M, Arvanitis C, Chu K, Dewey W, Leonhardt E, Trinh M, Sundberg CD, Bishop JM, Felsher DW. Sustained koss of a neoplastic phenotype by brief inactivation of MYC. Science. 2002;297:102–104. doi: 10.1126/science.1071489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurczyk A, Roy N, Bajwa R, Gut P, Lipson K, Yang C, Covassin L, Racki WJ, Rossini AA, Phillips N, et al. Dynamic glucoregulation and mammalian-like responses to metabolic and developmental disruption in zebrafish. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2011;170:334–345. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jürgens G, Weigel D. Terminal versus segmental development in the Drosophila embryo: the role of the homeotic gene fork head. Roux's Arch Dev Biol. 1988;197:345–354. doi: 10.1007/BF00375954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaposi-Novak P, Libbrecht L, Woo HG, Lee Y-H, Sears NC, Conner EA, Factor VM, Roskams T, Thorgeirsson SS. Central role of c-Myc during malignant conversion in human hepatocarcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2775–2782. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.-w., Zeller KI, Wang Y, Jegga AG, Aronow BJ, O'Donnell KA, Dang CV. Evaluation of Myc E-Box phylogenetic footprints in glycolytic genes by chromatin immunoprecipitation assays. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5923–5936. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.5923-5936.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan KM, Fujimoto E, Grabher C, Mangum BD, Hardy ME, Campbell DS, Parant JM, Yost HJ, Kanki JP, Chien C-B. The Tol2kit: a multisite gateway-based construction kit for Tol2 transposon transgenesis constructs. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:3088–3099. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai E, Prezioso VR, Tao WF, Chen WS, Darnell JE., Jr. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 3 alpha belongs to a gene family in mammals that is homologous to the Drosophila homeotic gene fork head. Genes Dev. 1991;5:416–427. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.3.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Lay J, Kaestner KH. The Fox Genes in the liver: from organogenesis to functional integration. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:1–22. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Zheng W, Wang Z, Zeng Z, Zhan H, Li C, Zhou L, Yan C, Spitsbergen JM, Gong Z. A transgenic zebrafish liver tumor model with inducible Myc expression reveals conserved Myc signatures with mammalian liver tumors. Dis Model Mech. 2013;6:414–423. doi: 10.1242/dmm.010462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. The Subread aligner: fast, accurate and scalable read mapping by seed-and-vote. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:e108. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyssenko V, Lupi R, Marchetti P, Del Guerra S, Orho-Melander M, Almgren P, Sjogren M, Ling C, Eriksson KF, Lethagen AL, et al. Mechanisms by which common variants in the TCF7L2 gene increase risk of type 2 diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2155–2163. doi: 10.1172/JCI30706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning AK, Hivert MF, Scott RA, Grimsby JL, Bouatia-Naji N, Chen H, Rybin D, Liu CT, Bielak LF, Prokopenko I, et al. A genome-wide approach accounting for body mass index identifies genetic variants influencing fasting glycemic traits and insulin resistance. Nat Genet. 2012;44:659–669. doi: 10.1038/ng.2274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrish F, Isern N, Sadilek M, Jeffrey M, Hockenbery DM. c-Myc activates multiple metabolic networks to generate substrates for cell-cycle entry. Oncogene. 2009;28:2485–2491. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motallebipour M, Ameur A, Reddy Bysani MS, Patra K, Wallerman O, Mangion J, Barker MA, McKernan KJ, Komorowski J, Wadelius C. Differential binding and co-binding pattern of FOXA1 and FOXA3 and their relation to H3K4me3 in HepG2 cells revealed by ChIP-seq. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R129. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-11-r129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami H, Sanderson ND, Nagy P, Marino PA, Merlino G, Thorgeirsson SS. Transgenic mouse model for synergistic effects of nuclear oncogenes and growth factors in tumorigenesis: interaction of c-myc and Transforming Growth Factor α in hepatic oncogenesis. Cancer Res. 1993;53:1719–1723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osthus RC, Shim H, Kim S, Li Q, Reddy R, Mukherjee M, Xu Y, Wonsey D, Lee LA, Dang CV. Deregulation of glucose transporter 1 and glycolytic gene expression by c-Myc. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21797–21800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000023200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajvani UB, Accili D. The new biology of diabetes. Diabetologia. 2015;58:2459–2468. doi: 10.1007/s00125-015-3722-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pati D, Keller C, Groudine M, Plon SE. Reconstitution of a MEC1-independent checkpoint in yeast by expression of a novel human fork head cDNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3037–3046. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.6.3037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson CW, Ayer DE. An extended Myc network contributes to glucose homeostasis in cancer and diabetes. Front Biosci. 2011;16:2206–2223. doi: 10.2741/3848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provost E, Rhee J, Leach SD. Viral 2A peptides allow expression of multiple proteins from a single ORF in transgenic zebrafish embryos. Genesis. 2007;45:625–629. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samaan G, Yugo D, Rajagopalan S, Wall J, Donnell R, Goldowitz D, Gopalakrishnan R, Venkatachalam S. Foxn3 is essential for craniofacial development in mice and a putative candidate involved in human congenital craniofacial defects. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;400:60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.07.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandgren EP, Quaife CJ, Pinkert CA, Palmiter RD, Brinster RL. Oncogene-induced liver neoplasia in transgenic mice. Oncogene. 1989;4:715–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanghera DK, Blackett PR. Type 2 Diabetes Genetics: Beyond GWAS. J Diabetes Metab. 2012;3:6948. doi: 10.4172/2155-6156.1000198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel A, Gut P. Metabolic insights from zebrafish genetics, physiology, and chemical biology. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72:2249–2260. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1816-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuff M, Rossner A, Wacker SA, Donow C, Gessert S, Knochel W. FoxN3 is required for craniofacial and eye development of Xenopus laevis. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:226–239. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott KL, Plon SE. CHES1/FOXN3 interacts with Ski-interacting protein and acts as a transcriptional repressor. Gene. 2005;359:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shachaf CM, Kopelman AM, Arvanitis C, Karlsson A, Beer S, Mandl S, Bachmann MH, Borowsky AD, Ruebner B, Cardiff RD, et al. MYC inactivation uncovers pluripotent differentiation and tumour dormancy in hepatocellular cancer. Nature. 2004;431:1112–1117. doi: 10.1038/nature03043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlen M, Fagerberg L, Hallstrom BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, Sivertsson A, Kampf C, Sjostedt E, Asplund A, et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science. 2015;347:1260419. doi: 10.1126/science.1260419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valera A, Pujol A, Gregori X, Riu E, Visa J, Bosch F. Evidence from transgenic mice that myc regulates hepatic glycolysis. FASEB J. 1995;9:1067–1078. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.11.7649406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Es JH, Haegebarth A, Kujala P, Itzkovitz S, Koo BK, Boj SF, Korving J, van den Born M, van Oudenaarden A, Robine S, et al. A critical role for the Wnt effector Tcf4 in adult intestinal homeostatic self-renewal. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:1918–1927. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06288-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Vliet-Ostaptchouk JV, Shiri-Sverdlov R, Zhernakova A, Strengman E, van Haeften TW, Hofker MH, Wijmenga C. Association of variants of transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCF7L2) with susceptibility to type 2 diabetes in the Dutch Breda cohort. Diabetologia. 2007;50:59–62. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0477-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigel D, Jurgens G, Kuttner F, Seifert E, Jackle H. The homeotic gene fork head encodes a nuclear protein and is expressed in the terminal regions of the Drosophila embryo. Cell. 1989;57:645–658. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JM, Bunte RM, Carty AJ. Evaluation of rapid cooling and tricaine methanesulfonate (MS222) as methods of euthanasia in zebrafish (Danio rerio) J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci. 2009;48:785–789. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Renard CA, Apiou F, Huerre M, Tiollais P, Dutrillaux B, Buendia MA. Recurrent allelic deletions at mouse chromosomes 4 and 14 in Myc-induced liver tumors. Oncogene. 2002;21:1518–1526. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.