Abstract

Bacterial pathogens employ type IV secretion systems (T4SSs) for various purposes to aid in survival and proliferation in eukaryotic host. One large T4SS subfamily, the conjugation systems, confers a selective advantage to the invading pathogen in clinical settings through dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes and virulence traits. Besides their intrinsic importance as principle contributors to the emergence of multiply drug-resistant ‘superbugs’, detailed studies of these highly tractable systems have generated important new insights into the mode of action and architectures of paradigmatic T4SSs as a foundation for future efforts aimed at suppressing T4SS machine function. Over the past decade, extensive work on the second large T4SS subfamily, the effector translocators, has identified a myriad of mechanisms employed by pathogens to subvert, subdue, or bypass cellular processes and signaling pathways of the host cell. An overarching theme in the evolution of many effectors is that of molecular mimicry. These effectors carry domains similar to those of eukaryotic proteins and exert their effects through stealthy interdigitation of cellular pathways, often with the outcome not of inducing irreversible cell damage but rather of reversibly modulating cellular functions. This chapter summarizes the major developments for the actively studied pathogens with an emphasis on the structural and functional diversity of the T4SSs and the emerging common themes surrounding effector function in the human host.

INTRODUCTION

Bacterial type IV secretion systems (T4SSs) are widely distributed among Gram-negative and -positive bacteria. These systems contribute in various ways to infection processes among clinically-important pathogens, including Helicobacter pylori, Brucella and Bartonella species, Bordetella pertussis and Legionella pneumophila (1–3). The list of pathogens employing T4SSs to subvert host cellular pathways for establishment of a replication niche continues to expand, making these machines an important subject of study for defining critical features of disease progression and development of strategies aimed at suppressing T4SS function (4). Also of importance, studies of T4SSs and effector functions have coincidentally and appreciably augmented our understanding of basic cellular processes in the human host.

The T4SSs are a highly diverse translocation superfamily in terms of i) overall machine architecture, ii) the secretion substrates translocated, and iii) target cell types which can include bacteria, amoebae, fungal, plant, or human (5). Several classification schemes have emerged to describe the T4SSs, the most widely used being based on overall machine function (1). Accordingly, one subfamily existing within nearly all species of bacteria and even some Archaea are the conjugation systems (Fig. 1) (5). These systems mediate transfer of mobile genetic elements (MGEs) in the form of conjugative plasmids or chromsomally-located integrative and conjugative elements (ICEs) to other bacteria by a mechanism requiring direct cell-to-cell contact (6–8). These systems are highly important vehicles for the widespread and rapid transmission of antibiotic resistance genes and virulence traits among medically important pathogens. In a context of the recent emergence of multiply-resistant ‘superbugs’, the dissemination of MGEs via conjugation represents a huge threat to human health and an enormous financial burden to society (9).

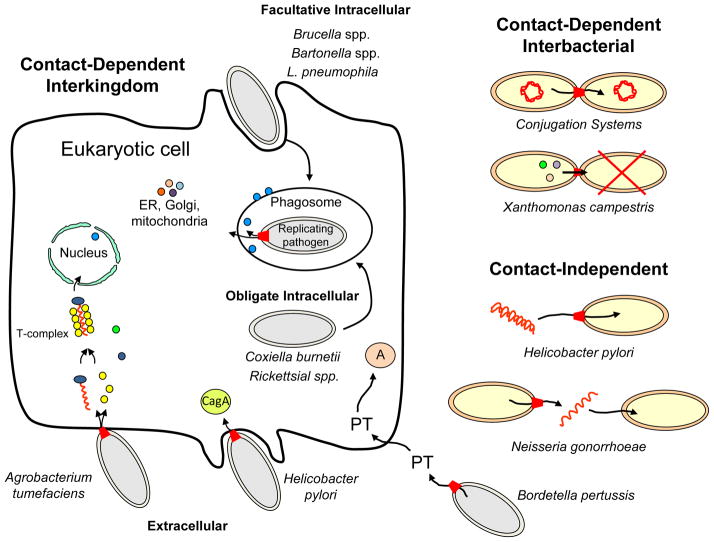

FIG. 1. Bacterial pathogens employing T4SSs for establishment within the human host, acquisition of DNA encoding virulence traits, or outcompetition of other bacteria for niche occupation.

Extracellular pathogens deliver substrates to human or plant cells by contact-dependent or -independent mechanisms. These pathogens deliver diverse substrates including oncogenic T-DNA, monomeric CagA, and multimeric PT toxin. Facultative intracellular pathogens enter the host cell from an environmental sample, whereas obligate intracellular pathogens enter directly from another host cell. The intracellular pathogens employ T4SSs to deliver a myriad of effectors whose collective function is to subvert host cellular processes principally for establishment of replicative niches. Shown are T4SSs on the bacterial cell envelope (red trapezoids), effectors (proteins: multicolor circles; T-DNA, red wavy line) and various target organelles/sites of effector action within the host cell. T4SSs also mediate interbacterial transfer by contact-dependent mechanisms for conjugative DNA transfer or to kill neighboring bacteria (red X), or by contact-independent mechanisms to exchange DNA with the environment.

The second subfamily, the ‘effector translocator’ systems, evolved from the conjugation systems but have acquired a different substrate repertoire composed mainly but not exclusively of proteins (1). Thus far, these systems have been identified only in Gram-negative pathogens, but recent work suggests a number of medically important Gram-positive species also rely on T4SSs for colonization through mechanisms not exclusively related to gene transfer (4, 10). The effector translocator systems deliver their cargoes into the eukaryotic cell cytosol usually by a cell-contact-dependent mechanism (Fig. 1). Upon translocation, the effector proteins target specific physiological pathways or biochemical processes with a variety of biological consequences that benefit survival, colonization, and transmission of the invading pathogens (3, 11, 12).

A third T4SS subfamily, the ‘DNA release and uptake systems’ presently is composed of a Neisseria gonorrhoeae T4SS functioning to deliver substrate DNA to the extracellular milieu and a H. pylori competence system used for DNA uptake by the bacterium (1). Both systems are closely functionally related to conjugation systems but adapted for DNA translocation in the absence of direct recipient cell contact (13, 14).

T4SSs alternatively have been designated as Type IVA, IVB or, recently, IVC (10, 15, 16). The IVA systems are composed of a dozen or so subunits homologous to components of the paradigmatic Agrobacterium tumefaciens VirB/VirD4 T4SS (17). This subfamily includes the well-characterized conjugation machines encoded by plasmids R388, pKM101, RP4, and F, as well as effector translocators employed by H. pylori, B. pertussis, Bartonella and Brucella spp., and Rickettsia spp (5). The IVB systems, exemplified by the L. pneumophila Dot/Icm system, bear little sequence relatedness to the IVA systems and are composed of over 25 subunits (16, 18). Other members of this family include the plasmid ColIb-P9 conjugation system and the Coxiella burnetii Dot/Icm effector translocator. The IVC systems, found almost exclusively in Gram-positive species, are composed of as few as five subunits and thus are also termed ‘minimized’ T4SSs (4, 10). Subunits of the IVC systems exhibit sequence similarities to a subset of the IVA components, and results of phylogenetic analyses suggest the IVC systems arose from the IVA systems (19).

An inherent difficulty in classifying T4SSs on the basis of function, structure, or phylogeny is that these are highly versatile and adaptive machines. A prominent example is the A. tumefaciens VirB/VirD4 T4SS, which functions both as a conjugation machine and an effector translocator and, while its target is plant cells in nature, it can also deliver substrates to other bacteria as well as various fungal and human cells (20). Many T4SSs also are highly mosaic in their subunit composition. For example, although the type IVA systems are built from homologs of VirB and VirD4 subunits, many systems have evolved specialized functions through loss of certain components or acquisition of others from unrelated ancestries (5, 19).

This chapter will summarize our recent progress in understanding the mechanism of action of T4SSs and their contributions to pathogenesis. We will focus the discussion mainly on contributions of the effector translocators to infection. To further highlight mechanistic themes and variations, we will group these systems according to the invasive mechanism, e.g., extracellular, facultative intracellular, obligate intracellular, of the pathogen, as illustrated in Figure 1. To further orient the reader, the pathogens discussed herein and some relevant properties relating to infection are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Type IV secretion systems and disease manifestations.

| Bacteria | T4SS | Diseases | Substrates | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interkingdom Transfer | ||||

| Extracellular Pathogens | ||||

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens | VirB/VirD4 | Crown Gall | Oncogenic T-DNA VirE2, VirE3, VirF | (20) |

| Bordetella pertussis | Ptl | Whooping cough | Pertussis Toxin | (47) |

| Helicobacter pylori | Cag | Gastritis, peptic ulcer, cancer | CagA | (65, 66, 90) |

| Facultative Intracellular | ||||

| Bartonella spp. | VirB/VirD4 | Cat-scratch, angiomatosis | BepA – BepG | (105) (95) |

| Trw | None | |||

| Brucella spp. | VirB | Brucellosis | ~14 | (95, 121, 222) |

| Legionella pneumophila | Dot/Icm | Legionnaire’s pneumonia | ~300 | (18, 127, 135, 137) |

| Obligate Intracellular | ||||

| Coxiella burnetti | Dot/Icm | Q fever | ~130 | (169, 223) |

| Anaplasma phagocytophilum | VirB/VirD4 | Granuloctyic anaplasmosis | AnkA, Ats-1, APH_0455 | (190, 224) |

| Anaplasma marginales | VirB/VirD4 | anaplasmosis | AM185, AM1141, AM470, AM705[AnkA] | (196) |

| Ehrlichia spp. | VirB/VirD4 | Ehrlichiosis | ECH0825 | (202) |

| Rickettsia spp. | VirB/VirD4 | Epidemic typhus, Mediterranean spotted fever | Unknown | (179, 188) |

| Wolbachia spp. | VirB/VirD4 | Endosymbiont of Filarial nematodes and arthropods | Unknown | (187) |

| Interbacterial Transfer | ||||

| Conjugation machines | Tra | Virulence and antibiotic resistance gene transfer Genome plasticity | Mobile elements | (5, 8, 9) |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens | VirB/VirD4 | Conjugation | IncQ plasmid | (35) |

| Bartonella spp. | VirB/VirD4 | Conjugation | IncQ plasmid | (111) |

| Legionella pneumophila | Dot/Icm | Conjugation | IncQ plasmid | (129) |

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Tra | DNA release | Chromosomal DNA | (14) |

| Helicobacter pylori | Com | DNA uptake | Exogenous DNA | (13) |

| Xanthomonas campestris | Xac | Killing: Interbacterial competition | Xac toxins | (219) |

T4SS ARCHITECTURES AND ADAPTATIONS

By way of introduction to these fascinating and complex machines, we will first summarize recent exciting progress in structure - function studies of the paradigmatic A. tumefaciens VirB/VirD4 T4SS and related conjugation systems, and then briefly describe some of the structural adaptations acquired by T4SSs for specialized functions in pathogenic settings.

The paradigmatic A. tumefaciens VirB/VirD4 T4SS

The T4SSs of Gram-negative bacteria are composed of four distinct machine subassemblies: i) the type IV coupling protein (T4CP), a hexameric ATPase related to the SpoIIIE/FtsK DNA translocases that recruits secretion substrates to the translocation machinery, ii) an inner membrane complex (IMC) responsible for substrate transfer across the inner membrane, iii) an envelope spanning outer membrane complex (OMC) required for substrate passage across the periplasm and outer membrane, and iv) the conjugative pilus, an extracellular organelle that initiates contact with potential recipient cells (Fig. 2) (8, 21, 22).

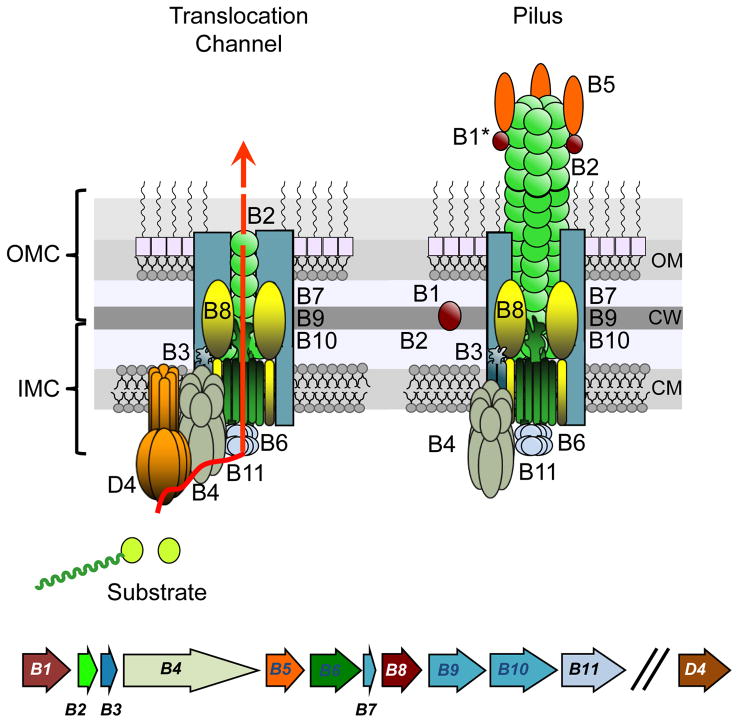

FIG. 2. Schematic of the Agrobacterium VirB/VirB T4SS.

Lower: virB genes are expressed from the same virB promoter and virD4 from a separate promoter (indicated by two slashes). Upper: The VirB and VirD4 subunits assemble as the translocation channel, which presents as two subcomplexes termed the outer membrane complex (OMC), composed of VirB7, VirB9, VirB10, and VirB2, and the inner membrane complex (IMC), composed of VirB3, VirB4, VirB6, VirB8, VirB11, and VirD4. VirB2, VirB5, and a proteolytic fragment of VirB1 (B1*) also assemble as the conjugative pilus without a requirement for VirD4. The physical and functional relationships between the translocation channel and the conjugative pilus are not yet known. OM, outer membrane; CW, cell wall; IM, CM, cytoplasmic membrane. See (24, 25, 237) for recent structures of related T4SSs.

A. tumefaciens is a phytopathogen that uses the VirB/VirD4 system to deliver oncogenic T-DNA and effector proteins to plants (Fig. 1) (20). A combination of structural and functional studies of the VirB/VirD4 T4SS and of closely related systems encoded by Escherichia coli conjugative plasmids, e.g., pKM101, R388, have generated for the first time a view of how the VirB/VirD4 T4SSs are architecturally arranged and function to convey secretion substrates across the Gram-negative cell envelope (Fig. 2). In studies carried out over a decade ago, the route of transfer of the oncogenic T-DNA substrate through the A. tumefaciens VirB/VirD4 T4SS was mapped with a formaldehyde (FA)-crosslinking assay termed transfer DNA immunoprecipitation (TrIP) (23). Results of the TrIP studies showed that the DNA substrate engages sequentially with VirD4, which then transfers it to the VirB11 ATPase. VirB11 in turn delivers the substrate to a putative translocation channel composed of VirB6 and VirB8 for delivery across the inner membrane. The substrate then passes through the periplasm and across the outer membrane via a channel minimally composed of VirB2 and VirB9.

More recent structural work has generated high-resolution structures of T4SS complexes, the latest of the near entire VirB/VirD4-like T4SS encoded by the conjugative plasmid R388 (24). Although the VirD4 and VirB11 ATPase subunits as well as the extracellular pilus were missing from this structure, the large ~3.2 MDa structure identified two VirB4 hexamers as part of a larger substructure the authors termed the IMC. Other IMC components include VirB3, VirB6 and VirB8. In the periplasm, the IMC is connected by a narrow stalk to the so-called OMC (also called the core complex). The OMC of the closely related E. coli pKM101-encoded T4SS is configured as a large barrel composed of 14 copies each of homologs of VirB7, VirB9, and VirB10 that extends across the entire cell envelope (25). Combining the results of the TrIP studies and the recent R388 structure, a cohesive model can thus be presented depicting the route(s) of substrate transfer across the Gram-negative bacterial cell envelope (Fig. 2) (22). Interestingly, in the pKM101 and R388 structures, the C-terminal regions of the VirB10-like scaffold proteins are predicted to form a channel across the outer membrane. While this might correspond to the pore through which substrates pass, it is likely this region of the channel is structurally more complex than currently depicted. This is because the structures solved to date lacked the pilin subunit and the conjugative pilus, which is also part of many T4SS structures (24, 25). In the TrIP studies, we did not detect DNA substrate crosslinking with A. tumefaciens VirB10, but rather contacts with the VirB2 pilin and VirB9. Conceivably, the distal portion of the translocation channel consists of a pilus-like structure that protrudes through the pore formed by the C terminus of VirB10 (Fig. 2) (17).

The A. tumefaciens VirB/VirD4 T4SS elaborates a conjugative pilus to mediate attachment to target cells. Assembly of the pilus does not require the VirD4 T4CP but does require the VirB1 lytic transglycosylase (17, 26). This pilus is composed of the pilin subunit VirB2 and the pilus-tip adhesin VirB5 (Fig. 2) (26). Its physical relationship to the VirB/VirD4 T4SS is not yet defined. However, in view of its role as an attachment organelle, it is interesting to speculate that the T4SS initially elaborates a pilus structure to establish contact with target cells. Then, once productive mating junctions are formed, the T4SS recruits the VirD4 T4CP for activation of the channel and subsequent substrate transfer. In such a model, the T4SS would function sequentially, first for elaboration of the pilus and second for biogenesis of the transfer channel.

Structure/function adaptations among T4SSs

While the R388 IMC/OMC complex can be viewed as a structural unit conserved among most if not all Gram-negative T4SSs, a large body of evidence now establishes that this structural unit has undergone extensive adaptation during establishment of pathogen - host relationships. Generally, the adaptations allow for i) substrate specific trafficking and spatiotemporal control of translocation during infection and ii) elaboration of novel and potentially antigenically variable pili or other surface structures. Examples of such adaptations are described briefly here and in Table 2, and discussed in more detail in subsequent sections.

Table 2.

T4SS machine adaptations enabling specialized functions.

| Bacteria | T4SS | T4SS Machine adaptation(s) | Specialized functions | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. tumefaciens | VirB/VirD4 | VirB1-VirB11, VirD4 | Transfer channel, Conjugative pilus Translocates DNA and protein substrates |

(35, 57) |

| B. pertussis | Ptl | No VirD4, VirB1, VirB5 homologs | Two-step translocation: PT subunits cross IM via GSP, PT crosses OM via Ptl T4SS No extracellular pilus |

(47) |

| H. pylori | Cag | VirB7-like CagT VirB10-like CagT have surface-exposed variable or repeat sequences | Phenotypic variation: Binding to different cell types, immune evasion | (40, 60, 69) |

| CagT | β1 integrin binding | |||

| VirB5-like CagL RGD motif | β1 integrin binding | |||

| CagA substrate at pilus tip | β1 integrin binding; translocation intermediate | |||

| Bartonella spp. | VirB/VirD4 | None | Translocates effectors & DNA substrate to human cells | (105)(110) |

| Trw | No VirD4 homolog | No substrate transfer | (42, 96) | |

| Multiple copies of VirB2 & VirB5 homologs | Variant forms of surface-exposed pilus for binding to different erythrocyte receptors? | |||

| Multiple copies of VirB6 & VirB7 homologs | Unknown | |||

| Brucella spp. | VirB | No VirD4 homolog | One-(?) and Two-step translocation via GSP and VirB systems | (114, 118, 225) |

| VirB12, orf13 | Serological marker, surface-exposed? | |||

|

A. phagocytophilum E. chaffeensis Rickettsia spp Wolbachia |

VirB/VirD4 | No VirB1, VirB5 homologs, but carries multiple copies of VirB2 paralogs and of ‘extended VirB6’ subunits | Variable pilus? Binding of different host cell/receptors? Immune modulation? | (41, 43, 187, 226,227) |

|

L. pneumophila C. burnetii |

Dot/Icm: Unrelated to VirB/VirD4 system | Translocates effectors & DNA substrate (to bacteria) | (18,44,130,131) | |

| VirB7 lipoprotein: N0 domain | Novel OMC structure | |||

| Fibrous surface mesh | Host cell binding? Immune modulation? | |||

| N. gonorrhoeae | Tra | No VirB11 homolog, Additional subunits related to F plasmid T4SS | DNA release to milieu | (228) |

| Variant forms of TraA pilin | Unknown | (14) | ||

| H. pylori | Com | No VirB, VirB5, VirB11 Com: DNA uptake across OM ComEC: DNA uptake across CM |

Natural transformation | (13) |

| X. campestris | Xac | VirB/VirD4 T4SS; VirB7 ortholog has N0 domain | Interbacterial delivery of Xac toxins for killing | (219) |

Substrate recruitment and translocation across the inner membrane

With a few notable exceptions, the T4SSs employ a T4CP receptor to recruit cognate substrates to the transfer channel. For docking with the T4CP, secretion substrates carry translocation signals located either C terminally and composed of clusters of positively-charged or hydrophobic residues, one or more internal signals of unspecified composition, or a combination of C-terminal and internal signals (27–31). Substrates also can have distinct translocation signals for docking with different T4SSs, providing another example of the functional versatility of these systems (30). In addition to these intrinsic translocation signals, T4SSs employ various chaperones or adaptor proteins for conferring substrate specificity and maintaining the substrate in a translocation competent form (32, 33). In the A. tumefaciens T4SS system, for example, translocation of the VirF effector proceeds independently of other known factors, whereas translocation of VirE2 requires cosynthesis of the VirE1 chaperone (34, 35). VirE2 is a single-stranded DNA binding protein that, upon transfer to plant cells interacts with the cotranslocated T-DNA to protect the DNA substrate and facilitate its delivery to the plant nucleus (Fig. 1). VirE1 shares several features of the specialized chaperones associated with type III secretion systems (T3SSs), including a small size, acidic pI, and an amphipathic helix. As discussed further below, the L. pneumophila Dot/Icm T4SS translocates hundreds of effectors to mammalian cells during infection. A subset of these is dependent on four accessory proteins residing in the cytoplasm or inner membrane. These include DotM, DotN, IcmS, and IcmW, which interact with each other in different combinations to mediate binding and recruitment of different substrates to the DotL T4CP (32). Thus, in L. pneumophila, a combination of C-terminal and internal translocation signals, together with a complex network of chaperone/adaptor/substrate interactions, regulates delivery of specific subsets of effector proteins through the Dot/Icm T4SS to host cells during L. pneumophila infection (32, 33).

T4SS structural and surface organelle variations

Many VirB/VirD4-like systems also have appropriated novel domains of functional importance (Table 2) (36). For example, some VirB6 subunits possess >30-kDa domains located at their C termini that have been shown or are proposed to localize at the cell surface (37, 38). Some VirB7-like lipoproteins and VirB10-like structural scaffolds also carry novel surface-localized motifs. Most notably, H. pylori CagT and CagY are classified as VirB7- and VirB10-like, respectively, but both subunits are considerably larger than their VirB counterparts and both localize extracellularly as a component of a large sheathed filament produced by the Cag T4SS (39). CagT and CagY also possess repeat regions that differ in size and composition among Cag systems of different H. pylori isolates (5, 40). Additionally, several systems including the Bartonella Trw system and VirB/VirD4 T4SSs carried by species in the order Rickettsiales carry multiple pilin genes in tandem array in their genomes, suggesting that variable pilus structures are elaborated through differential expression or intergenic recombination (41–43). Other T4SSs lack pilin genes or genes encoding the pilus tip protein VirB5, which is essential for elaboration of pili. These systems therefore probably do not elaborate pili but might still display surface structures, as exemplified by the L. pneumophila Dot/Icm, which encodes a fibrous structure on the cell surface (44). Collectively, the novel surface variable proteins or structures acquired by various T4SSs during evolution are thought to contribute to establishment of pathogen-host cell interactions, e.g., by mediating attachment to different host cells or host cell receptors or through modulation of the immune response.

T4SS EFFECTORS AND THEIR ROLES IN PATHOGENESIS

Besides appropriating novel structural motifs for specialized functions, the versatility of T4SSs is reflected in the diversity of substrates translocated to bacterial or eukaryotic target cells. Among the effector translocators employed by pathogens during infection, some translocate a single substrate, most deliver a restricted number of a half dozen or so, and a few highly promiscuous systems are estimated to translocate from fifty to several hundred effectors (Fig. 1, Table 1). In the following sections, we will review recent information about these systems, focusing mainly on the biochemical and cellular activities of effectors upon delivery to the host. Over the past decade, as studies have progressed on the T4SSs as well as the functionally (but not ancestrally) related T3SSs, it has become clear that common themes have emerged in the evolutionary design of many effectors. Most prominently, many effectors carry eukaryotic-like domains and thus exert their effects on various cellular processes or signaling pathways by mimicking activities of endogenous cellular proteins. For both the T4SSs and T3SSs, molecular mimicry has evolved predominantly to ‘fine-tune’ specific cellular functions to the advantage of the invading pathogen rather than irreversibly blocking cellular homeostasis. Indeed, recent work shows that both of these dedicated secretion pathways often target apoptotic pathways with the aim of inhibiting premature death of the host cell in which the pathogen is attempting to establish a replicative niche.

Extracellular pathogens

Bordetella pertussis is the causative agent of whooping cough, a respiratory illness spread mainly through aerosolization (45). Vaccination initiated in the 1940’s led to a decline in incidence, but since the 1990s the number of cases of whooping cough has increased worldwide (46). The reasons underlying the resurgence are not clear, but are generally attributed to waning of protective immunity from vaccination or natural infection, low vaccination coverage, transmission from individuals vaccinated with the currently used acellular vaccines, or genetic changes in B. pertussis to resistance against current vaccines (46). B. pertussis has several virulence factors of importance to infection and human-to-human spread, including pertussis toxin (PT) which is the sole substrate of the Ptl T4SS (47). PT is an ADP-ribosylating toxin composed of the catalytic A subunit and 5 B subunits required for translocation of the A subunit across eukaryotic cell membranes (48–51). Genes encoding PT subunits and the Ptl T4SS are genetically linked and coexpressed from the same promoter (52, 53).

Although the Ptl T4SS was recognized over 20 years ago to be closely related in overall gene order and subunit composition to the A. tumefaciens VirB/VirD4 T4SS and conjugation machines (54), it has several important distinctions that impart novel structural and functional features (Table 2). First, it lacks a homolog for the VirD4 substrate receptor, implying that an alternative mechanism has evolved for recruitment of the PT substrate to the transfer machine. In fact, the A and B subunits each carry a classical sec signal sequence and are translocated across the inner membrane via the general secretory pathway (GSP), completely independently of the Ptl system (55). Once in the periplasm, the subunits associate with the outer membrane and then assemble as the holotoxin, a process requiring extensive folding and disulfide bond formation. Mature holotoxin no longer associates with the outer membrane, but instead is released to periplasm, and becomes available for recruitment to the Ptl T4SS (47). The signal(s) mediating toxin recruitment to the T4SS is presently unspecified, although a domain of the A subunit may comprise part of it. Upon recruitment, the Ptl T4SS delivers PT across the outer membrane and to the extracellular milieu (56). Thus, two distinct machines, the Sec translocase and the Ptl T4SS, export PT in a two-step translocation reaction, in contrast to the one-step translocation route envisioned for the T4CP-dependent T4SSs (Fig. 2) (57).

Also in contrast to other T4SSs, which translocate partially or completely unfolded substrates, the Ptl system exports PT as a large, tightly folded multimer. The most recent structures obtained for VirB/VirD4 conjugation systems show no obvious portals of entry or outer membrane channels of a size sufficient to accommodate PT (24, 25, 58). This suggests that the Ptl T4SS must have acquired a novel outer membrane architecture for exporting this AB5-type toxin. Finally, the Ptl system lacks homologs for VirB1 and VirB5, two subunits required for biogenesis of pili (54). Accordingly, the Ptl system releases its cargo to the milieu, dispensing with a need for pilus or pilus-dependent contacts with the host cell.

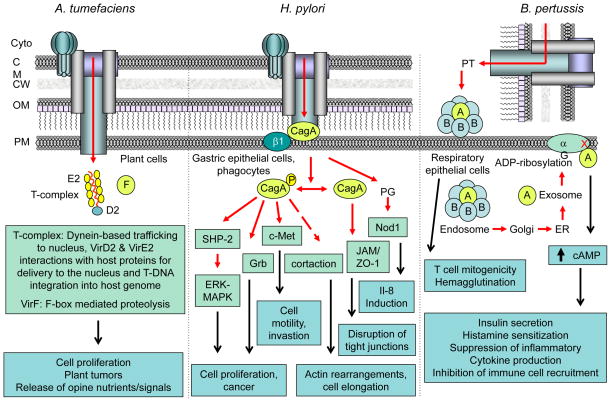

Once PT is released to the milieu, it can interact with various mammalian cells, predominantly respiratory epithelial cells (Fig. 3) (45). The B oligomer of the toxin mediates binding to cell surface receptors, predominantly glycosylated proteins or lipids, which can induce host cellular responses such as T cell mitogenicity and hemagglutination independently of the biological activities attributable to the catalytic function of the A subunit within the host cell (59). Entry of PT into the host cell occurs by receptor-mediated endocytosis. PT trafficking follows the retrograde transport system sequentially through the endosomal compartment, Golgi apparatus, and endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Independently of the B moiety, the A moiety translocates through the ER into the cytosol to its target protein, membrane-associated trimeric G proteins. Upon binding, the A subunit catalyzes ADP-ribosylation of Cys residues in the C-terminal part of the α subunit of trimeric G proteins. ADP-ribosylation of Giα locks the protein in an inactive state, resulting in a loss of inhibition of adenylate cyclase activity and an increase in intracellular concentration of cAMP. Increased cAMP levels disrupts many cellular processes, accounting for the majority of pathological consequences of B. pertussis infection. Common effects are increased insulin secretion, sensitization to histamine, and inhibition of immune cell recruitment (Fig. 3) (45, 47).

FIG. 3. T4SS effectors and cellular consequences of translocation by extracellular pathogens.

A. tumefaciens and H. pylori deliver substrates through direct cell-cell contact, and B. pertussis by a contact-independent mechanism. Pathogens target the host cell types listed. Translocated effectors interact (red arrows, dash denotes indirect interaction) with host cell proteins (light green boxes) to modulate various cellular processes and signaling pathways. Cellular consequences of the effector - host protein interactions (black arrows) are listed (aqua boxes).

Overall, the B. pertussis Ptl system represents a fascinating and, to date, novel example of a T4SS that evolved through loss of conserved subunits from an ancestral machine as a two-step translocation pathway capable of translocating a folded multimeric toxin to eukaryotic cells independently of direct cell-cell contact.

Helicobacter pylori is an extracellular pathogen that colonizes the gastric epithelium. It is the principal cause of chronic active gastritis and peptic ulcer disease and a risk factor for the development of gastric carcinoma and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma (Table 1) (60, 61). Virulent strains of H. pylori associated with the enhanced risk of developing peptic ulcers or adenocarcinoma harbor a 37-kilobase (kb) pathogenicity island (PAI) encoding the cytotoxin-associated gene (Cag) T4SS (62, 63). Also present on this PAI is a gene encoding CagA, the only known protein substrate of this T4SS (64). CagA is a ~120–145 kDa protein that shows no significant homology with other known proteins. Its size variation is due to structural diversity in its C-terminal region (65). In contrast to the B. pertussis Ptl system, the Cag T4SS recruits CagA from the bacterial cytoplasm via the Cagβ substrate receptor for transfer in one step across the H. pylori cell envelope and into mammalian target cells (Fig. 3).

The Cag T4SS is related to the A. tumefaciens VirB/VirD4 system but is also considerably more complex, as evidenced by the appropriation of more than a half dozen subunits and subdomains from unknown ancestries (66). As mentioned earlier, CagT and CagY are respectively classified as VirB7- and VirB10-like, yet both subunits are considerably larger than their VirB counterparts. These subunits comprise part of an OMC that is probably similar in overall structure to those solved for conjugation machines, while their additional domains localize extracellularly as a component of an extracellular pilus or large sheathed filament associated with the Cag T4SS (Table 2) (39). Importantly, these domains are composed of repeat regions that differ in size and composition among the various H. pylori strains (67, 68). Functions of these repeat regions are not yet defined, but are postulated to affect binding of H. pylori cells to mammalian cells through modulation of host β1 integrin interactions (69). There is also evidence that passage of H. pylori in mouse models results in variant forms of VirB10-like CagY, originally prompting the suggestion that CagY undergoes antigenic variation through homologous recombination within its repeat regions to evade the host immune response while maintaining T4SS function (67, 68). However, very recent work showed that immune driven DNA rearrangements in CagY serve not so much to evade the host immune response altogether, but rather to fine tune the response so as to establish the optimal homeostatic conditions of inflammation for persistent infection (40).

The Cag T4SS reportedly elaborates two types of surface structures, a large sheathed structure and pili, both implicated in interactions with host cells (39, 70, 71). The sheathed structures are 70 nm in diameter and are composed of pilin-like proteins CagC and CagL, as well as extracellular domains of CagY, CagT, and CagX (39). CagY and CagL bind β1 integrins, consistent with a role for this structure in attachment to host cells (69). More recent work has focused on the much narrower (~13 nm wide) pilus-like structures (71, 72). These pili are detected only when H. pylori cells are cocultured with gastric epithelial cells, in an abundance of 3 to 4 pili per adherent H. pylori cell. Most of the Cag T4SS subunits are required for pilus assembly, although strikingly not the VirB2 pilin-like CagC subunit or VirB10-like CagY, even though both of these subunits are required for T4SS function as monitored by induction of IL-8 production and CagA translocation (72). Together, these observations raise the interesting possibility that the Cag T4SS elaborates distinct organelles for different purposes in relation to the infection process. Although specific functions of these T4SS structures awaits further definition, it is noteworthy that CagL, a homolog of the VirB5 pilus tip protein in A. tumefaciens, clearly plays a role in mediating interaction with host cell β1 integrins via its RGD motif (73). Through its RGD-dependent integrin binding activities, purified CagL has been shown to elicit several responses in human cells, including cell adhesion, cell spreading, activation of host cell tyrosine kinases, and secretion of IL-8 (74, 75).

The importance of Cag T4SS-encoded pili to the H. pylori infection process is further underscored by the finding that strains that fail to produce pili are defective in Cag T4SS-dependent IL-8 induction in gastric epithelial cells (71, 76). Furthermore, changes in environmental conditions, such as reduced iron concentration, result in correlative increases in pilus production and Cag T4SS-associated activities (77). Also of interest, the sole protein substrate, CagA, of this T4SS is detectable on the H. pylori cell surface, particularly at the tip of pili (Fig. 3) (40, 69, 73). Both the surface display and pilus association of CagA are unique features among other known T4SS secretion substrates, and at least two lines of evidence support the notion that CagA surface accessibility is a biologically relevant entity. First, CagA binds phosphatidylserine at the outer leaflet of the host cell cytoplasmic membrane, which in turn induces its uptake into the cell (78). Second, as noted above, CagA translocation depends on the presence of β1 integrins as receptors for binding by the T4SS components CagL, CagY, CagI. However, CagA itself also binds strongly to β1 integrins, suggesting that the pilus-tip bound form is a translocation intermediate (69).

Several recent studies have explored the underlying mechanisms responsible for recruitment and passage of CagA through the Cag T4SS. Docking of CagA with the T4SS requires three proteins, a chaperone CagF, the VirD4 homolog Cagβ, and CagZ (79, 80). CagA is highly labile in H. pylori cells unless it is coproduced and forms a complex in a 1:1 stoichiometry with the CagF chaperone. CagF differs from other T4SS or T3SS secretion chaperones, e.g., A. tumefaciens VirE1. Besides being much larger (32-kDa) than the other (< 5-kDa) chaperones, CagF is highly hydrophobic and recently was shown to bind all five domains of CagA, presumably forming a broad interaction surface that protects the entire protein from degradation (81). CagF binding is also thought to prevent CagA intramolecular interactions of importance for protein function upon translocation to mammalian cells but might block CagA docking with the Cagβ receptor in H. pylori. While the nature of the CagA - Cagβ docking reaction remains to be defined, it is evident that the Cag T4SS has appropriated a novel CagF accessory factor to promote stabilization of the large, multidomain CagA substrate and docking with the Cagβ receptor (81).

Upon delivery into gastric epithelial cells, CagA is localized to the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane where it undergoes tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig. 3). The phosphorylated protein interacts with SH2-domain-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase (SHP2) (82). CagA resembles the Gab family of scaffold proteins, which also form a complex with SHP2 in a tyrosine phosphorylation dependent manner in juxtaposition to the plasma membrane. Thus, partly through Gab mimicry, CagA exerts its many effects in host cells through promiscuous binding of a variety of human proteins by both phosphorylation-dependent and -independent mechanisms (Table 3) (83).

Table 3.

Molecular Mimicry: Eukaryotic protein domains carried by T4SS effectors.

| Motif | Biochemical function | T4SS Effector* | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| EPIYA | Tyrosine phosphorylation |

Hp CagA Bh BepD, BepE, BepF Ap AnkA |

(87–89, 229) |

| Ank | Protein-protein interaction |

Ap, Ec, Rr AnkA Ec p200 Lp AnkB, AnkX, AnkH, AnkJ, 7 others Cb AnkA,B, D*,F,G Wolbachia wPip: 60 Ank proteins Ot: 50 Ank proteins Rf: 22 Ank proteins |

(198, 199, 230, 231) |

| F box | Interaction with SCF ubiquitination complexes |

At VirF Lp AnkB, LicA, LegU1, PpgA, Lpg2525 Cb AnkD, CBU0814, CBU0014 Ot Anklu9 |

(158, 159, 232, 233) |

| Farnesylation/Prenylation | Post-translational modification for protein - protein, protein - membrane interactions |

Lp AnkB Lp Lpg2525, LegU1? |

(234, 235) |

| FIC | AMPylation, phosphorylation, UMPylation, phosphocholination |

Lp AnkX Bh BepA, BepB, BepC |

(96, 102) |

| Gab | Family of scaffold protein | Hp CagA | (83) |

| ARF-, Ras-GEF | Guanine nucleotide exchange | Lp RalF, LegG2 | (152, 236) |

| SREBPs | Sterol regulatory element binding proteins | Am APH_0455 | (197) |

Abbreviations: Hp, Helicobacter pylori; Bh, Bartonella henselae; Ap, Anaplasma phagocytophilum; Ec, Ehrlichia chafeensis; Lp, Legionella pneumophila; Cb, Coxiella burnetii; Ot, Orientia tsutsugamushi; At, Agrobacterium tumefaciens; Am, Anaplasma marginales

CagA is phosphorylated by Src family kinases (SFKs) at Tyr residues in the Glu-Pro-Ile-Tyr-Ala (EPIYA) motifs that resemble c-Src consensus phosphorylation sites and are located in variable numbers in the C-terminal region of the protein (Table 3) (84). Binding of phosphorylated CagA (CagA-P) to SHP2 causes aberrant activation of SHP2 and consequently of the ERK-MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) pathway, which reportedly contributes to carcinogenesis by inducing mitogenic responses (Fig. 3) (65). CagA-activated SHP2 also dephosphorylates focal adhesion kinase, causing impaired focal adhesions that are associated with an elongated cell shape known as the hummingbird phenotype (85). Interestingly, East Asian CagA and Western CagA are respectively characterized by the presence of an EPIYA-D segment and an EPIYA-C segment to which SHP2 binds in a phosphorylation dependent manner. The EPIYA-D segment binds SHP2 more strongly than the -C segment, and it is speculated that H. pylori carrying the biologically more active East Asian CagA variant are responsible for the propensity of these strains to induce severe gastric atrophy and gastric cancers in infected patients (86).

Since the discovery of the CagA EPIYA motif, at least nine other T4SS or T3SS effectors were shown to carry such eukaryotic-like motifs with similar biochemical activities upon translocation to host cells. Among the T4SSs discussed in more detail below, the Bartonella henselae VirB/VirD4 T4SS translocates three effectors (BepD, PepE, and BepF) each with one or more EPIYA or EPIYA-like motifs (87). The Anaplasma phagocytophilum AnkA effector also bears multiple EPIYA motifs that display variations in number and subtypes among different bacterial strains (88). Other pathogens employing T3SSs to translocate EPIYA-bearing effectors during infection include Chlamydia trachomatis (the Tarp effector, induces cytoskeletal rearrangements) and enteropathogenic E. coli (Tir, triggers actin pedestal formation). Haemophilus dureyi also delivers two EPIYA-containing effectors, LspA1 and LspA2, via a two-partner secretion system to eukaryotic cells whereupon inhibition of Src family kinase (SFK) functions blocks Fcγ-mediated triggering of phagocytosis (Table 3) (89).

In addition to the SHP2 interaction, an array of other CagA-binding partners has been described, including carboxy-terminal Src kinase (Csk), growth factor receptor-bound protein 2 (Grb2), tight junction protein zonula occludens 1 (ZO-1), scatter factor receptor c-Met and phospholipase C-γ. This plethora of CagA phosphorylation-dependent and –independent interactions modulates pathways involved in the innate immune response, cell shape regulation, and signal transduction (Fig. 3) (see (90, 91)). There is also compelling evidence that the Cag T4S machine, through receptor dependent activation or translocation of fragments of peptidoglycan or another unidentified effector(s), operates independently of CagA and of VirD4-like Cagβ to elicit stress-response pathways that result in induction of IL-8 secretion (Fig. 3) (92).

Facultative intracellular pathogens

Bartonella spp. reside in erythrocytes and cause long-lasting bacteremic infections in diverse mammalian hosts. They are transmitted by blood-sucking arthropods most often through dermal inoculation. Upon reaching the blood stream, Bartonella spp. invade erythrocytes and persist intracellularly for the lifetime of the red blood cell. Adaptation to the reservoir host causes no or mild disease symptoms, whereas infection of incidental hosts can cause a spectrum of diseases including cat-scratch disease, Carrion’s disease, chronic lymphadenopathy, trench fever, chronic bacteraemia, endocarditis, bacillary angiomatosis, peliosis hepatis and neurological disorder. Without treatment, Bartonella infections are associated with high mortality and the potential for relapse due to the existence of an intraerythrocytic phase that may provide a protective niche for the bacteria (93–95).

Bartonella spp. employ two T4SSs for different purposes relating to the infection process (Table 2) (96). The Trw T4SS shares strong sequence similarities with the Trw system encoded by the IncW plasmid R388, with the exception that it lacks a homolog for the VirD4-like substrate receptor (97). The Trw homologs of the two systems share 20 to 80% sequence identities, and interestingly the Bartonella tribocorum Trw genes encoding VirB5-like TrwH, VirB10-like TrwE, and VirB11-like TrwD substitute for their homologs in the TrwR388 system (97, 98). This finding underscores the conservation of machine architecture between two T4SS that have evolved for completely different functions. However, since the Bartonella Trw system lacks a VirD4-like T4CP, it is postulated to function not as a translocation system but rather to mediate attachment to host cells. In line with such a function, the Trw locus possesses tandem copies of genes encoding homologs of the VirB2 and VirB5 pilin proteins, suggesting that this system is specifically adapted for the production of antigenically variable pili through intergenic recombination (97). The adaptation of a T4SS for elaboration of a variable surface structure aligns this system with the H. pylori Cag system, which elaborates variant forms of surface-exposed channel subunits, as well as Rickettsial systems discussed later in this chapter.

Studies have shown that the Trw system is required for establishing intra-erythrocytic infection in a B. tribocorum - rat model (93, 97). A signature-tagged mutagenesis (STM) screen further identified mutations in the trw locus that severely impaired adhesion of Bartonella birtlesii to erythrocytes (99). Based on the postulated surface location of the Trw components, this T4SS might directly interact with the erythrocyte surface thereby restricting the host range of the erythrocyte infection. A role for this system in host-specificity was confirmed through a demonstration that swapping of Trw from rat-specific B. tribocorum for that of cat-specific Bartonella henselae and human-specific Bartonella quintana shifted the host ranges of these latter species for erythrocyte infection towards rats (42). The further observation that the Trw pilin subunits exist in multiple copies suggests the trw locus encodes variant forms of surface-exposed pilus which might facilitate the specific interaction with polymorphic erythrocyte receptors either within the reservoir host population or among different reservoir hosts (42).

The second T4SS, designated VirB/VirD4, is composed of a complete set of homologs of the A. tumefaciens VirB and VirD4 subunits (100, 101). It contributes to pathogenicity by delivering up to seven effector proteins termed Beps (Bartonella effector proteins) into nucleated cells (Fig. 4). The Beps were identified originally by the presence of a ~140-residue domain near their C termini that was termed BID (Bep Intracellular Delivery). This domain and a positively charged C-terminal tail sequence correspond to a bipartite translocation signal required for delivery of several of the Beps through the VirB/VirD4 T4SS (28). For a few Beps, the BID domain is not required for translocation but rather contributes to effector function in the host cell.

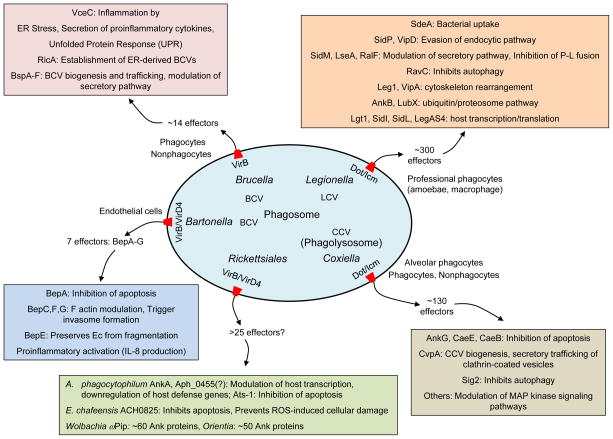

FIG. 4. T4SS effectors and cellular consequences of translocation by intracellular pathogens.

The pathogens listed deliver effector proteins to establish a replicative niche within phagosomal compartments. Associated with each organism is the name of the T4SS, the replicative niche (e.g., LCV for Legionella-containing vacuole), the host cell type(s) targeted, and the current number of known or estimated effectors. Also for each organism is a list of representative effectors and cellular consequences of their activity within the host cell (colored boxes).

Once inside the host cells, Beps target host components and modulate cellular processes to the benefit of the bacteria. A deletion of all seven bep genes (bepA-bepG) abolishes all VirB/VirD4-dependent cellular phenotypes, including cell invasion, pro-inflammatory activation, and the inhibition of apoptosis (Fig. 4) (28). The Beps have a modular architecture that includes one or more BID domains. BepA, BepB, and BepC also carry a FIC (filamentation induced by cAMP) domain, which is present in many bacteria and eukaryotes including mammals (Table 3) (96). FIC enzymes posttranslationally modify proteins through AMPylation, UMPylation, phosphorylation, or phosphocholination. All FIC enzymes catalyze the transfer of a part of a metabolite upon cleavage of a pyrophosphate-bond (102). Besides their presence in Bartonella Beps, FIC domains have been identified in effectors translocated by the L. pneumophila Dot/Icm system (AnkX) as well as T3SSs employed by Pseudomonas syringae (AvrB), Vibrio parahaemolyticus (VopS), and Xanthomonas campestris (AvrAC) (102). At this point, however, the contributions of Bep FIC domains to Bartonella infection processes have not been defined. As mentioned earlier, some Beps also carry EPIYA motifs serving as sites of tyrosine phosphorylation upon delivery into the mammalian host (Table 3) (28, 103).

Considerable progress has been made toward defining specific contributions of the Bep proteins to stages of the infection cycle (Fig. 4). In brief, upon deposition on the skin by a blood sucking arthropod, one or a few Bartonella cells are taken up by endocytosis into a vacuole called Bartonella-containing vacuole (BCV) (104, 105). The process of endocytosis is arrested by Beps (BepC, BepF, BepG) delivered into the host cytoplasm by the VirB/VirD4 T4SS (106, 107). Bacterial aggregates form at the cell surface, and these bacteria then invade the endothelial cells via F-actin-dependent invasome-mediated internalization (105). Bartonella then colonize the ‘dermal niche’ most likely within dendritic cells, which are considered important for dissemination to the ‘blood-seeding niche’. BepE is essential for invasion of cells in the dermal niche and for subsequent spread to the blood stream. Recently, it was reported that the BID domains of BepE contribute to endothelial cell migration and prevent cell fragmentation through interference of the RhoA signaling pathway (108). Furthermore, BepA mediates protection of endothelial cells from apoptosis through binding of a BID domain to host cell adenylyl cyclase with a consequence of elevated cAMP production and inhibition of apoptosis (109).

In sum, investigations to date point to essential contributions of the VirB/VirD4 T4SS and Bep effectors to the primary stages of infection. All Bep-dependent phenotypes have been shown to rely on the different BID domains, which collectively exert their effects on different physiological or signaling pathways in the human host and also serve as translocation signals in the bacterium presumably for productive binding with the VirD4 receptor. At this time, nothing is known of how the FIC and EPIYA domains contribute to the Bep-dependent phenotypes, despite evidence for tyrosine-phosphorylation of BepE’s EPIYA motif and binding of phosphorylated BepE to SHP2 and Csk, two well-characterized binding targets of H. pylori CagA. Of final note, the B. henselae VirB/VirD4 T4SS was shown to be capable of delivering DNA into vascular endothelial cells (110). This T4SS is closely related in subunit composition to conjugation systems, underscoring both the common ancestry and functional similarities of effector translocator and conjugation systems (111). Whether DNA transfer is a natural substrate that Bartonella delivers to eukaryotic cells during the infection process is an intriguing question for further study.

Brucella spp. cause abortion in their natural animal hosts (e.g., swine, goats/sheep, cattle, bison) and are responsible for human brucellosis. Brucella infect and replicate in phagocytic and non-phagocytic cells. The bacteria can persist for years in the reticuloendothelial system (RES) of their natural hosts as well as incidental human hosts (112). Human brucellosis is characterized by undulant fevers and constitutional symptoms including malaise, mayalgia, and enlarged spleens and livers. Chronic infection can progress to severe complications including arthritis and endocarditis. Factors mediating uptake are not completely defined, but once endocytosed, Brucella reside initially in the Brucella-containing vacuole (BCV). The BCV interacts sequentially with early and late endosomes and lysosomes, finally establishing an intracellular replicative niche derived from the ER. Subsequent to replication, Brucella exit host cells to reinfect adjacent cells (113).

The VirB T4SS of Brucella plays a critical role in establishment of the ER-derived replicative BCVs, and is an essential virulence factor in a mouse model of infection (114–116). It is also essential for persistence of the bacteria in a mouse model and goat host (115, 117). While the Brucella T4SS gene cluster contains homologs of all of the A. tumefaciens VirB genes, there is no VirD4-like receptor and the operon contains two additional genes, virB12 and orf13 (Table 2) (114). The absence of a VirD4-like receptor suggests either that an alternative routing mechanism exists for substrate transfer across the inner membrane (as shown for B. pertussis PT translocation) or that this machine does not translocate substrates but provides another function, e.g., attachment, of importance for infection (as proposed for the Bartonella Trw system). Confirming the former model, several Brucella effectors are now known to be translocated by a VirB-dependent mechanism to host cells (see below). Very intriguingly, only a subset of the effectors carry a classical sec signal suggestive of a two-step translocation route reminiscent of the PT toxin export system (118). The mechanism(s) by which other Brucella effectors engage with the VirB machine, and in which cellular compartment (e.g., cytoplasm, periplasm), remains to be determined.

Acidification of the phagosome is required for induction of the virB operon encoding the Brucella VirB T4SS during infection of macrophages (119). Production of the T4SS and effector translocation allows for evasion of lysosomal fusion with the BCV and association with the ER-derived intracellular compartment (120). Effector candidates were identified by bioinformatics screens for eukaryotic-like domains, genes that are coregulated with the virB operon, and genes whose products interact with human ER exit site (ERES)-associated proteins. At this time, 14 effectors have been identified, although in most cases their functions during infection are not yet established (Fig. 4). Interestingly, an additional 6 candidate effectors also appear to be translocated to human cells independently of the T4SS (121).

The first identified effectors were VceA and VceE, and VceE is currently the best characterized among all Brucella effectors (118). VceC has been shown to induce ER stress and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines (Fig. 4). Ectopically expressed VceC binds the ER in HeLa cells via an interaction with the ER chaperone BiP/Grp78, and VceC production is correlated with reorganization of ER structures (122). Furthermore, in macrophages, VceC triggers the unfolded protein response (UPR), resulting in the induction of inflammation by Brucella abortus (122). Whether VceC exerts its activity on the UPR through binding of BiP remains to be determined. VceC is not thought to be involved in establishment of the BCV, but rather contributes to long-term colonization and overall fitness of the infecting Brucella. However, another effector termed RicA (Rab2 interacting conserved protein A) binds the GDP-bound form of Rab2, a host GTPase shown to be essential for Brucella intracellular replication through binding of BCVs. Correspondingly, ricA mutants show a decrease in Rab2 recruitment to BCVs (123). These findings led the authors to postulate that T4SS-mediated translocation of RicA is important for establishment of the ER-derived replicative BCVs by enabling precise interactions with secretory pathway organelles (Fig. 4).

Two effectors, BrpA and BtpB, share a conserved TIR (Toll/Interleukin-1 receptor)-containing domain and both are essential for virulence (124, 125). BtpA exerts its effects through inhibition of NF-kB and the toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling pathway, whereas BtpB activates NF-kB and the TLR pathway. TIR-containing adaptors are widely present in mammals where the associated proteins regulate the signaling cascades of innate immune recognition. However, many bacteria besides Brucella employ TIR domain-containing proteins for modulation of the TLR signaling cascade, thus providing another example of molecular mimicry by pathogens for subversion of host cellular processes.

Finally, by use of a reporter assay for translocation, 5 candidate effectors designated BspA-F were identified whose delivery to human cells was dependent on the VirB T4SS (121). Importantly, several of these effectors were shown to localize to compartments of the secretory pathway when ectopically expressed in HeLa cells. Furthermore, ectopically expressed BsbA, BspB, and BspF were found to specifically inhibit host protein secretion and membrane trafficking along the secretory pathway, in line with observations that such perturbations are also observed during Brucella infection. Additionally, evidence was presented that these Bsp’s contribute to the biogenesis of BCVs and to bacterial replication in macrophages, as well as to long-term persistence in the liver of chronically infected mice. These new findings establish a possible link between BCV trafficking and VirB T4SS-dependent modulation of the secretory pathway (Fig. 4) (121).

Legionella pneumophila is ubiquitous in the environment, preferentially thriving in water systems. They colonize a variety of ecological niches, including various amoebae and other protozoa in which they can grow and replicate (126). Legionella enters the human lung via inhalation of Legionella-containing aerosols. The bacteria replicate in alveolar macrophages and can cause a potentially fatal pneumonia termed Legionnaires’ disease. The L. pneumophila infection cycle involves host-cell entry by phagocytosis, creation of a specialized vacuole termed the ‘Legionella-containing vacuole’ (LCV) for replication, macrophage lysis, and infection of neighboring cells (127). Creation of the LCV requires the Dot/Icm T4SS, which has the amazing capacity to translocate an estimated 300 effector proteins, approximately 10% of this organism’s proteome, into target cells (18, 128). Like the Bartonella spp. and A. tumefaciens VirB/VirD4 systems, the Dot/Icm T4SS has retained a functional vestige of its ancestral conjugation system in being able to mobilize transfer of IncQ plasmids to bacterial recipients, although the functional significance of DNA transfer during the infection process is not known (33, 129).

As mentioned earlier, the Dot/Icm systems are only weakly related to the VirB/VirD4 systems and thus were termed type IVB systems (15). The Dot/Icm systems are composed of at least 25–27 proteins, many of which localize to the cytoplasm or inner membrane (32). A number of these are chaperones or adaptors that fulfill the complex task of delivering the multitude of effectors to the host cell at appropriate times during the infection cycle. Recent structural work has shown that the cell envelope-spanning channel consists in part of a ring-shaped OMC similar to that of the VirB/VirD4 T4SSs (130). A notable variation from the latter systems is that DotD, a lipoprotein thought to provide a stabilizing function similar to that of VirB7, possesses a large domain structurally similar to N0 domains (131). Such domains are also found associated with secretins in the types II and III secretion systems, and might serve as a structural scaffold or for recruitment of substrates in the periplasm (see (131)). The Dot/Icm T4SS is thought to translocate substrates in one step across the cell envelope, but this model has not been rigorously tested, so a role for the N0 domain of DotD in substrate binding remains a possibility. Another difference with the VirB/VirD4 T4SSs is that the Dot/Icm system does not elaborate extracellular pili but rather a fibrous mesh on the bacterial cell surface composed at least in part of the DotH and DotO proteins. (44)

Most of the candidate effectors were identified through a combination of bioinformatics screens and assays for translocation using reporter protein fusions (132). Efforts to establish the importance of given effectors to the infection process, however, have been hampered by the fact that many effectors have redundant functions (133). In some cases, mutant strains lacking a single effector show intracellular growth defects upon depletion of specific host factors or are outcompeted by wild-type bacteria in competition assays (127, 134). Functions have been assigned for about 50 of the candidate effectors, which can be grouped based on their major cellular target pathway(s) during the infection cycle (135). A full description of the biochemical activities of the Dot/Icm T4SS effectors is beyond the scope of this chapter, and the interested reader is referred to several excellent reviews (127, 135–137). Here, we will identify and describe activities of a subset of the effectors shown to affect specific secretory pathways and cellular functions relevant to the infection process.

L. pneumophila replicates in ‘professional’ phagocytes such as amoebae and macrophages (133, 138). It employs the Dot/Icm T4SS to deliver effector proteins as soon as it contacts the cell (Fig. 4). One effector, SdeA, is implicated as being important for bacterial adherence and uptake, although further work is needed to confirm this function (139). However, the internalization process activates T4SS function, resulting in the translocation of presynthesized effector molecules (140, 141). Effector translocation enables L. pneumophila to evade endocytic (lysosome) fusion and intercept ER-to-Golgi vesicular traffic to remodel its phagosome into an ER-derived vacuole that serves as a proliferation niche (133). Internalization progresses to formation of the LCV, which communicates extensively with the endosomal trafficking route largely through acquisition of host molecules and effectors on the LCV membrane. For example, the LCV acquires two types of molecules, PI lipid phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate [Ptdlns(3)P] and Rab GTPases, that are key regulators of the early endocytic pathway (135). Several Dot/Icm substrates including LidA, LptD, RidL, and SetA have been shown to bind Ptdlns(3)P possibly as an LCV membrane anchor (142–145). The effector SidP is a PI 3-phosphatase that hydrolyses Ptdlns(3)P and thus might contribute to evasion of the endocytic pathway (146). A number of Rab GTPases (Rab5A, Rab7, Rab14, Rab21) are recruited to the LCV, and several effectors interact with these GTPases. One of these, VipD, is activated by Rab5 and one of its functions is to remove Ptdlns(3)P from the LCV membrane (147). Thus, like SidP, VipD is thought to promote LCV evasion of the endocytic pathway. Other effectors acting on the endocytic pathway include SidK, which binds one of the subunits of V-type H+-ATPase (a late endosomal marker that also binds the LCV) and inhibits ATP hydrolysis, proton translocation and LCV acidification (148).

The LCV compartment also modulates the secretory pathway by intercepting early secretory vesicles released from ER exit sites towards the Golgi apparatus. The Dot/Icm effectors SidM and LseA have been shown to modulate this secretory pathway by promoting the fusion of LCVs with ER-derived vesicles through effects on SNARE (soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor) complex formation (149, 150). SNARES are responsible for the docking and fusion of many different vesicle-mediated transport events. Another PI, Ptdlns(4)P, as well as the GTPase Rab1, are major regulators of Golgi-bound, secretory vesicle trafficking. Ptdlns(4)P is formed on the LCV membrane through the actions of SidF (151) and other effectors. Several Dot/Icm effectors bind the LCV via Ptdlns(4)P or Rab1. These effectors collectively modulate the secretory pathway through their various biochemical activities including AMPylation, deAMPylation, ubiquitination, phosphocholination, and guanine nucleotide exchange (see (135)). For example, RalF, the first identified Dot/Icm effector, functions as a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) that mediates LCV fusion with ER-derived secretory vesicles (ESVs) and the ER by recruiting and activating Arf1, another small GTPase involved in vesicle trafficking from the ER to Golgi (152).

Besides altering the endocytic and secretory pathways, L. pneumophila uses the Dot/Icm T4SS to translocate numerous other effectors that act on a plethora of other host cellular processes to benefit survival in the host cell (Fig. 4). In brief, effectors such as RavZ are known to inhibit autophagy (153) and RidL to modulate the retrograde pathway (145). Others such as Legs2 associate with mitochondria possibly disrupting host cell bioenergetics (154), VipA with actin to effect cytoskeleton remodeling (155, 156), or AnkB with the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway (157–159). Others modulate programmed cell death in several ways that include modulation of host transcription and translation (see (135)).

Studies over the past decade have generated an extensive literature about the L. pneumophila T4SS and contributions of effectors to the infection process. Equally importantly, these studies have identified novel features of fundamental biochemical and cellular processes in the host cell. Given that only a small subset of the candidate effectors have been characterized so far, future studies will assuredly continue to unveil new mechanistic insights at many levels into the fascinating L. pneumophila - host cell relationship.

Obligate intracellular pathogens

Coxiella burnetii is an intracellular bacterium that causes the zoonotic disease Q fever. It is transmitted by inhalation of contaminated aerosols, and can cause life threatening illness with vague symptoms similar to those described above for Rickettsial infections that can progress to pneumonia, hepatitis, myocarditis or central nervous system complications (160). C. burnetii can also cause long-term chronic disease that can manifest as endocarditis years after the initial infection (161). Ruminants are the natural reservoir for Coxiella, and infections of these animals can cause abortion and subsequent contamination of the environment. As for the Rickettsial species, studies of C. burnetii pathogenesis have been hampered by the obligate intracellular lifestyle of the bacterium. However, an axenic culture condition was described in 2009, which has revolutionized studies of this pathogen that have supplied important new information about the bacterial factors, particularly its Dot/Icm T4SS and translocated effectors, to virulence (162).

Coxiella has the capacity to enter both phagocytic and non-phagocytic cells, where it replicates to high numbers inside a specialized vacuole termed the Coxiella-containing vacuole (CCV) (163). The CCV undergoes normal endocytic trafficking through early and late endosomes to a lysosome. In contrast to the Legionella-containing vacuole that subverts the endocytic trafficking to avoid lysosome fusion, however, the CCV fuses with the lysosome. Within this acidic environment, Coxiella then differentiates from an environmentally stable small cell variant (SCV) into a replicating large cell variant (LCV). The CCV then undergoes expansion by recruitment of cellular vesicles that fuse with the vacuole membrane, during which time Coxiella replicates to large numbers (164).

The Dot/Icm system was discovered by genome sequencing and was shown to be essential for virulence through construction and analysis of dot/icm transposon insertion or deletion mutations (165–168). As discussed above, the L. pneumophila T4SS assembles prior to host cell uptake and delivers effectors upon initial contact to subvert the endocytic pathway and promote fusion with secretory vesicles. By contrast, the Coxiella T4SS translocates effectors only several hours after infection, following CCV-lysosome fusion, with the overall objective of remodeling this vacuole to facilitate replication.

To date, over 130 candidate effectors have been identified for this system, through bioinformatics screens to identify proteins with eukaryotic-like motifs and experimental verification by use of reporter protein translocation assays (see (169)). Interestingly, a large number of the candidate effectors were classified as pseudogenes in some strains that can block synthesis or translocation, or alter the protein’s activity in the host through loss of one or more domains. Such genetic alterations have been postulated to contribute to the evolution of different Coxiella variants (170).

Although biochemical characterization of Coxiella effectors is still in its infancy, a variety of screens and approaches have identified effectors that contribute to CCV biogenesis and intracellular growth, and that modulate different cellular processes and pathways (Fig. 4). The host cell must remain viable to support Coxiella replication, and several effectors have been shown to inhibit the host cell death pathway. AnkG, for example, blocks apoptosis by interacting first with the host mitochondrial protein p32 and subsequently with the nucleus where it exerts its anti-apoptotic effects by an unknown mechanism (171, 172). Other anti-apoptic effectors include CaeA and CaeB, which bind respectively to the mitochondria and nucleus where they are thought to interfere with apoptotic signaling (173). A number of other effectors, identified through large-scale transposon mutagenesis screens, have been shown to be important for intracellular replication. This list now includes CirA-E (Coxiella effector for intracellular replication) as well as Cig57, CoxCC8, CBU1754, and CvpA-CvpE (174, 175). Identification of CvpA was of interest in view of evidence that clathrin-mediated vesicular trafficking is important for CCV biogenesis. Clathrin was shown to be present on the CCV membrane, and reduction in the level of CCV-bound clathrin was correlated with diminished Coxiella replication. Further studies showed that CvpA interacts with the clathrin-adaptor complex AP2, leading to a proposal that this effector contributes to CCV biogenesis and intracellular replication through recruitment of host cell clathrin transport machinery and possibly other factors to the CCV (176). Another effector, Cig2, was shown to contribute to establishment of the replicative niche by blocking autophagy, a process used by the host cell to remove misfolded proteins, damaged organelles and intracellular pathogens through targeting to the lysosome (175). Finally, several effectors have been shown to modulate MAP kinase signaling pathways in yeast, possibly through disruption of the phosphorylation state of pro-apoptotic proteins (166, 177, 178).

At this time, studies of effector function have identified important contributions to establishment of the CCV and intracellular replication through effects on autophagy, secretory trafficking of clathrin-coated vesicles, apoptosis, and signal transduction. The challenges for the future are to define the specific biochemical functions of these effectors. Another important goal is to define the contributions of the Dot/Icm system and other virulence factors to the unique capacity of this bacterium to survive and replicate in the acidic, proteolytic and oxidative environment of the lysosome-derived CCV.

Rickettsial spp. are obligate intracellular pathogens or endosymbionts. The major genera include Anaplasma, Ehrlichia, Orientia, Rickettsia and Wolbachia (179). The Rickettsiales associate with diverse eukaryotic hosts in pathogenic or symbiotic relationships. Rickettsial species are responsible for major human diseases including Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (Rickettsia rickettsii), epidemic typhus (Rickettsia prowazekii), and zoonotic diseases of granulocytic anaplasmosis (Anaplasma phagocytophilum) and monocytic ehrlichiosis (Ehrlichia chaffeensis) (179, 180). Orientia tsutsugamushi is the causative agent of scrub typhus (181). Clinical signs of these diseases are similar and include fever, headache, myalgia, anorexia, and chills, frequently accompanied by leukopenia. Diseases can progress to meningitis and disseminated intravascular coagulation, which if left untreated can progress to multiple organ failure. Transmission is generally by a tick, mite or other insect vector from animal reservoirs (179, 180).

Wolbachia are endosymbionts or parasites associated with numerous invertebrates including arthropods and nematodes. In filarial nematodes, Wolbachia are essential for survival and replication of their host (182). In arthropods, Wolbachia are mostly parasites that affect reproduction of their hosts in ways that enhance their own transmission through maternal inheritance from infected females to progeny (183). Strikingly, there is evidence for widespread horizontal gene transfer of Wolbachia chromosomal fragments into many species of arthropods and nematodes, and in the latter for expression of the integrated genes (184). These findings raise the intriguing possibility that Wolbachia might employ their T4SSs to translocate chromosomal DNA for establishment of symbiotic or parasitic relationships with their hosts.

All characterized members of the Rickettsiales carry genes for T4SSs, although the genes typically are not clustered in a single operon but rather in two or three operons scattered around the genome (43, 185–188). O. tsutsugamushi offers the most extreme known example of the fragmentation of T4SS genes around the chromosome (189). The chromosomes of these bacteria are themselves highly fragmented, presumably as a result of extensive recombination at the 4,197 identical repeat sequences shown to be distributed around the genome. The O. tsutsugamushi genome also carries over 1,100 mobile genetic elements, which is especially intriguing in view of the fact that mobile elements are only rarely present in the genomes of other Rickettsial species (189). These findings provide compelling evidence that conjugative transfer has played an important role in the shaping of the O. tsutsugamushi genome throughout evolution.

Besides the unusual distribution of T4SS genes around the chromosome, the Rickettsial T4SSs possess a number of variations from the archetypal VirB/VirD4 T4SSs (Table 2). First, these systems lack pilus-associated proteins (VirB1, VirB5) thought to be involved in intercellular attachment processes, possibly reflecting the intracellular lifestyle of these bacteria (41, 43, 190). Another novel adaptation is the presence of multiple copies of genes encoding several of the VirB homologs. The genomes typically carry genes in single copy for the structural subunits VirB8, VirB9, and VirB10, as well as the ATPases VirB11 and VirD4. However, multiple copies exist for genes encoding inner membrane channel subunits VirB3 and the VirB4 ATPase as well as polytopic VirB6 (43, 190). Most noteworthy, the multiple VirB6 subunits display considerable variability in length and sequence composition, particularly in their hydrophilic C-terminal regions (5). There is evidence for surface exposure of VirB6 homologs in E. chaffeensis and Wolbachia, leading to the suggestion that these variable proteins promote survival in the host through binding of host cell receptors or evasion of host immune defenses (37, 191–193). Additionally, multiple copies exist of genes encoding sequence variable VirB2 pilin-like subunits, reminiscent of the Bartonella Trw T4SS (Table 2) (41). How these T4SS-encoded surface structures contribute to the infection processes of these intracellular pathogens is an intriguing question for further study.

Identification of T4SS effectors functioning in Rickettsial species has been challenging given a lack of genetic systems for mutant strain constructions and the inability to culture these bacteria axenically. However, a number of candidate or confirmed effectors have been identified through a combination of bioinformatics screens, two-hybrid assays for protein interactions with the VirD4-like substrate receptors, and use of surrogate T4SSs, e.g., the A. tumefaciens VirB/VirD4 and Legionella Dot/Icm systems, to assay for translocation (194–197). In bioinformatics screens, the ankryin repeat (Ank) is a particularly prominent eukaryotic-like domain identified in the genomes of various members of the Rickettsiales. Wolbachia strain ΩPip and O. tsutsugamushi respectively carry an astonishing 60 and 50 ank genes, the most identified to date for any bacterial species (198).

The Ank repeat is a 33-residue motif, often in tandem arrays, that cooperatively folds into structures that mediate molecular recognition via protein-protein interactions (Table 2). These are widespread interaction motifs in eukaryotes, and they are also features of T4SS as well as T3SS effectors, and there is evidence that such proteins play important roles in pathogenesis by mimicking or interfering with host cell functions (199). Indeed, the first T4SS effector identified among the Rickettsiales was AnkA shown to be a secretion substrate of the A. phagocytophilum T4SS (Fig. 4) (194). AnkA contains 11 Ank repeat motifs and a positively-charged C-terminal tail similar to those carried by secretion substrates of the A. tumefaciens VirB/VirD4 T4SS. Accordingly, AnkA was shown to be translocated through the A. tumefaciens VirB/VirD4 T4SS to plant cells (194). In its natural mammalian host cell, AnkA is phosphorylated by the Abl-1 and Src kinases, and phospho-AnkA then binds the host protein Src homology phosphatase-1 (SHP-1) (88). Interestingly, AnkA binds nuclear proteins and forms complexes with AT-rich DNA sequences, resulting in modulation of host gene transcription (200). Recently, AnkA was found to downregulate expression of multiple host defense genes, including the NADH oxidase component, CYBB. AnkA also binds the histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1), which is critical for AnkA-mediated CYBB repression. The consequence of CYBB downregulation is a decrease in superoxide anion production by the NADH oxidase, which is a key mechanism of pathogen killing for neutrophils (201). Given the observation that AnkA binds to numerous sites in the host genome and histone deacetylation is frequently observed at host promoters of host defense genes, it is likely that AnkA broadly impacts the host transcriptional response to A. phagocytophilum infection (Fig. 4).