Summary

The differentiation of osteoclasts (OC) from early myeloid progenitors is a tightly regulated process that is modulated by a variety of mediators present in the bone microenvironment. Once generated, the function of mature OC depends on cytoskeletal features controlled by an αvβ3-containing complex at the bone-apposed membrane, and the secretion of protons and acid-protease cathepsin K. OC also have important interactions with other cells in the bone microenvironment including osteoblasts and immune cells. Dysregulation of OC differentiation and/or function can cause bone pathology. In fact, many components of OC differentiation and activation have been targeted therapeutically with great success. However, questions remain about the identity and plasticity of OC precursors, and the interplay between essential networks that control OC fate. In this review, we summarize the key principles of OC biology, and highlight recently uncovered mechanisms regulating OC development and function in homeostatic and disease states.

Introduction

Although bone is one of the hardest tissues in the body, necessary for its structural and protective roles, this organ is not static. Bone matrix must be renewed over time in order to maintain its mechanical properties and myeloid lineage cells called osteoclasts (OC) are the specialized cells that perform this critical function. Since bone is the major storage site for calcium, OC play an important role in the regulation of this signaling ion by releasing it from bone. In this process, OC respond indirectly to calcium-regulating hormones such as parathyroid hormone and 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D3. Growth factors such as insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and transforming growth factor- β (TGF-β) are also incorporated into bone matrix and released by OC, affecting the coupling of bone formation to bone resorption and potentially targeting other cells in the microenvironment such as metastatic tumors. Lastly, OC retain features of other myeloid cells such as antigen presentation and cytokine production which afford them the potential to affect immune responses. Thus, the OC plays many roles in health and disease.

OC are multinucleated cells formed by fusion of myeloid precursors. In normal circumstances, OC are only found on bone surfaces, although cells with similar features can be found in association with some tumors, even outside of the bone. In contrast with the multinucleated giant cells found in granulomas such as in sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, or foreign body responses, OC express tartrate resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP), the vitronectin receptor, αvβ3 integrin, and calcitonin receptor. These polykaryons have a unique cytoskeletal organization and membrane polarization that allows them to isolate the bone-apposed extracellular space where bone resorption occurs. Not surprisingly, OC differentiation and function are tightly regulated and rely on many signaling pathways important to other immune cells, both innate and adaptive, providing both challenges and opportunities for their therapeutic targeting in disease states.

In this chapter we will discuss the differentiation of OC, a process known as osteoclastogenesis, and the relationship of OC precursors to other myeloid lineages. We will also describe their unique functional features, providing a glimpse into their unusual cell biology, and interactions with other cells. Finally, we will address the pathophysiology of several diseases associated with bone loss, focusing on several key extracellular mediators dysregulated in osteolytic conditions.

Osteoclast precursors

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) differentiate into all blood cell lineages (1), including the mononuclear phagocyte system from which OC arise. Consistent with the conventional view that bone marrow niches are the primary sites of postnatal hematopoiesis (1), medullary fractions from humans and animal models are excellent sources of OC precursors. Indeed, unfractionated marrow leukocytes (2–4) or macrophages expanded in vitro in the presence of macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) (5, 6) are commonly used to induce in vitro osteoclastogenesis under the influence of appropriate cues, especially M-CSF and RANKL, as described below. OC can also be differentiated from peripheral blood (7–9), spleen and fetal liver (8, 10, 11). While early committed OC precursors express TRAP (12) and αvβ5 integrin (13), late precursors and fully differentiated OC up-regulate cathepsin K (14, 15), calcitonin receptor (16), OC-associated receptor (OSCAR) (17) and αvβ3 integrin (18, 19).

Bone marrow macrophages expanded in M-CSF for several days are technically easy to obtain, the yields are quite high (up to 50 million from one adult mouse), and the extent of OC formation reflects the intrinsic differentiation potential of a relatively uniform population of precursors. However, in some disease states or abnormal/mutant genotypes, there are changes in the frequency of precursors, rather than in the response of individual cells to differentiation cues (20). Use of unfractionated marrow cells rather than expanded macrophages can reveal alterations in early precursors and also prevents loss of effects due to the microenvironment in vivo, such as those stemming from hormonal effects or stromal cell support.

Much effort has gone into identifying specific precursor populations, but like many myeloid cell types, the OC precursor has defied a single definition. Hematopoietic cells from various developmental stages, including CD34+ HSC (21, 22), CD265 (RANK)+ monocytes (23), and CD14+ monocytes (9, 24, 25), possess the ability to undergo osteoclastogenesis. M-CSF-expanded marrow macrophages express CD11b (αM integrin), CD265 (RANK), and CD115 (M-CSF receptor/c-Fms) (8). The critical role of these last two receptors for OC differentiation will be discussed in detail below. The utility of CD11b as a marker of OC precursors, and its role in osteoclastogenesis is more complex. Some groups have found that precursors expressing CD11b have high osteoclastogenic potential (8, 26) while others claim that the CD11blow/neg population is more efficient (27, 28). Jacquin et al found that Cd11bhigh bone marrow fractions generate OC more slowly than a CD3−B220−CD11b− fraction, but with a similar efficiency (29). Conflicting results may come from differences in experimental techniques such as the time allowed for differentiation, the plasticity of the precursor populations, and the dynamic regulation of CD11b expression. Indeed, CD11b is up-regulated by M-CSF and subsequently down-regulated by RANKL (23, 29, 30). A recent study of CD11b-deficient mice showed that this molecule acts early as a negative regulator of OC differentiation, and its engagement favors an inflammatory macrophage phenotype (31).

Several groups have tried to further refine the identity of OC precursors, with the expectation of improving cellular homogeneity and differentiation efficiency. CD117 (c-kit) is expressed on all early hematopoietic progenitors, and cells expressing both CD115 and CD117 form OC readily (29). This population can also form phagocytic macrophages and dendritic cells (28). Ly6C, a component of the Gr1 epitope found on monocytic myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSC), was found on an OC precursor pool present in normal bone marrow, but amplified in inflammatory arthritis (27). However, the population identified in this study remained heterogeneous for other markers such as CD11b and CD117. Others have shown that OC can differentiate from Gr1+/CD11b+ MDSC in the context of cancer (32–34). Besides CD markers, OC precursors also display several additional surface molecules at some point during differentiation, including dendritic (DC)-specific transmembrane protein (DC-STAMP) (35), OC-STAMP (36), calcium-dependent cell-cell adhesion molecules, E-cadherin (37, 38) and protocadherin-7 (39), and a disintegrin and metalloproteinase (ADAM) family members, mainly ADAM8 (40). None of these is completely restricted to the OC lineage.

Osteoclast differentiation

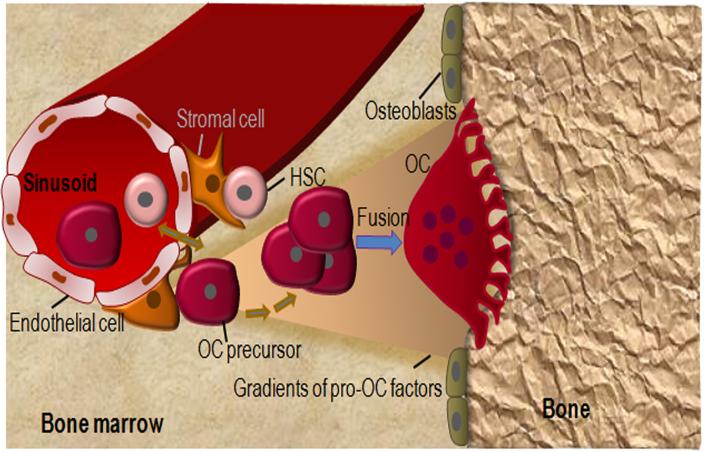

The presence in the bloodstream of cells capable of OC differentiation is well documented (9, 21, 22, 25). However, it is still unclear whether bone marrow-derived myeloid cells in the adult bone marrow directly differentiate into OC or enter the bloodstream before re-entering the bone microenvironment to form OC. It is possible that, rather than providing a source of homeostatic OC for bone, circulating OC precursors represent a pool that can be recruited in pathological states such as inflammatory arthritis or heterotopic ossification. Irrespective of the potential systemic circulation of OC precursors, the conceptual framework is that within the bone microenvironment, OC precursors are generated in or near perivascular HSC niches and migrate toward the bone surface where they terminally mature into OC (Fig. 1). According to this concept, OC precursors may be lured to bone surfaces by gradients generated by bone matrix proteins and degradation products, calcium ions, lipid mediators (e.g., sphingosine-1-phosphate (41–43) or chemokines such as CXCL12, which are produced by the osteoblast lineage cells (44), the main regulators of OC differentiation in homeostatic states.

Figure 1.

A model of OC differentiation. OC differentiate from HSC. The hematopoietic niche comprises endothelial cells and perivascular stromal cells, which exhibit MSC features. It is still unclear whether OC precursors directly differentiate into OC or enter the bloodstream before re-entering the bone microenvironment to form OC. In any scenario, higher levels of chemoattractants toward bone surfaces, including bone extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, lipid mediators (e.g., sphingosine-1-phosphate) and ECM degradation products create gradients that attract OC precursors to the hard tissue where they fuse and complete the differentiation process. Conversely, higher levels of peri-vascular chemorepellents (not drawn for simplicity) may also contribute to the migration of OC precursors toward the endosteum.

Even before the identification of specific factors governing osteoclastogenesis, it was clear that stromal, osteoblast lineage cells could provide support for this process (45, 46). The essential role of M-CSF in the proliferation and survival of the OC lineage was uncovered in the early 1980s following an observation that hematopoietic progenitors from op/op mice formed normal monocyte/macrophage colonies only when exposed to colony-stimulating activity derived from wild-type stromal cells (47). This activity was assigned to M-CSF a decade later when it was discovered that op/op mice failed to produce this growth factor due a mutation in the M-csf gene (48). Osteopetrosis in op/op mice stems from inadequate OC lineage commitment of macrophages, which are also diminished in numbers (49). M-CSF is involved in the growth and survival of the OC lineage through regulation of numerous pathways such as MAPK (ERK and JNK) (50), GSK-3β/β-catenin (51) and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), whose signaling intermediates include PI3K and Akt (52). Moreover, M-CSF was more recently found to increase diacyl glycerol levels through stimulation of PLCγ, an event that causes c-Fos activation (53), thus suggesting that this growth factor can also induce OC differentiation signals. The M-CSF receptor c-Fms (CD115) can also be activated by newly identified IL-34 (54, 55), and mice lacking c-Fms show a more severe osteopetrotic phenotype compared to those with impaired M-CSF production (56). M-CSF, as well as IL-34, promotes the expression of RANK (CD265), whose downstream signaling pathways also drive differentiation (see below). Other factors such as granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (57), vascular endothelial growth factor (58, 59), and hepatocyte growth factor (60) can also provide mitogenic and survival signals to the OC lineage, though with less efficiency compared to M-CSF.

RANKL is another essential factor required for the differentiation, survival and function of OC. Its discovery two decades ago was a breakthrough that reinvigorated the field of OC biology (61, 62). The findings that transgenic mice expressing high levels of RANKL develop osteoporosis whereas mice lacking RANKL or the decoy receptor OPG are osteopetrotic (63) and osteoporotic (64), respectively, underscore the central role of this pathway in OC development. Furthermore, rare cases of osteopetrosis have been ascribed to inactivation or deficiency of RANKL or RANK, its receptor (65). Deactivating mutations in OPG cause the high turnover bone disorder known as Juvenile Paget's Disease, and activating mutations of RANK lead to a range of osteolytic conditions, including familial expansile osteolysis (66).

Monocytes expressing RANK, a TNF receptor family member, exposed to RANKL exit the cell cycle and fuse to form multinucleated OC. This process involves activation of various pathways including MAPK (p38, JNK, ERK), mTor, PI3K, NF-κB (canonical and alternative) and microphthalamia-associated transcription factor (MiTF) (52, 67–69). Many of these pathways contribute to expression of NFATc1, the “master” osteoclastogenic transcription factor (70), whose activation also depends on a PLCγ2/Ca2+ pathway (71). As it is emerging for other signaling pathways, RANK signaling induces protein post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation (71), ubiquitination (72), SUMOylation (73), and poly-ADP-ribosylation (our unpublished data). Developing evidence also indicates a crucial role of epigenetic mechanisms in RANKL control of OC differentiation (74, 75). Indeed, RANKL regulates the expression of several species of microRNA (76). DNA methyltransferase 3a is a DNA-modifying enzyme with profound effects on bone homeostasis as mice lacking this protein develop a high bone phenotype due to defective osteoclastogenesis (77). RANKL also induces histone 3 (H3) trimethylation (H3K4me3, a mark of transcriptionally active chromatin) while attenuating H3K27me3 (a mark of silent chromatin) near the transcription start site of several genes encoding OC transcription factors such as NFATc1 and NF-κB (78). Pharmacological interference with the recruitment of CREB-binding protein (CBP) to acetylated histones at the NFATc1 promoter impairs RANKL's osteoclastogenic effects (79). Accordingly, the deacetylase SIRT1, which removes acetyl groups from proteins, including histones, also modulates RANKL-induced OC formation (80, 81). Thus, RANKL regulation of OC development involves a plethora of signaling networks, including epigenetic mechanisms.

A third signal reported to control osteoclastogenesis emanates from immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM)-harboring adaptors such as DNAX activation protein of 12 kDa (DAP12) (82) and Fc receptor γ (FcRγ). These cell surface molecules have very small extracellular domains, and interact with co-receptors TREM2 and Sirpβ1 (DAP12) or OSCAR and PIR-A (FcRγ) in order to signal to Ca2+/NFATc1 through PLCγ-2 (83, 84). In mice, deletion of either ITAM protein has no effect on bone mass, while deletion of both causes severe osteopetrosis. Initial reports concluded that this phenotype was the result of a failure in OC differentiation (83, 84). However, while Mocsai et al. (83) showed normal expression of a number of markers of mature OC (β3 integrin, calcitonin receptor, cathepsin K) suggesting intact differentiation, Koga et al. (84) found a failure to induce Ca2+ oscillations and NFATc1 induction, and thus poor differentiation, in DAP12/FcRγ double-deficient cells. Complicating interpretation of the phenotype, DAP12/FcRγ deficient mice lose bone very efficiently in response to ovariectomy in the long bones, but not vertebrae (85). RBP-J, a transcription factor usually associated with Notch signaling, was shown to impose a requirement for ITAM-mediated costimulation on RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis; in the absence of RBP-J, ITAM signaling was completely dispensible (86). Thus, a role for ITAM in OC differentiation may be site and/or context dependent. Other studies have indicated that the primary role of the ITAM-mediated signaling appears to be in the regulation of the OC cytoskeleton (discussed below), with little effect on differentiation (82, 87). Furthermore, loss of TREM2, the co-receptor for DAP12 increases osteoclastogenesis, via β-catenin, suggesting a Ca2+/NFATc1-independent effect (51). Thus, the role of ITAM signaling in OC differentiation remains incompletely resolved.

Beyond RANKL, M-CSF and the ligands for ITAM-associated receptors, the normal bone marrow microenvironment contains a wide variety of OC-regulating molecules, including cytokines, growth factors, hormones, and the recently reported danger signals, which function via the inflammasomes. These molecules act through or interact with M-CSF and RANKL, the most proximal signals in OC differentiation to fine-tune pro- and anti-osteoclastogenic inputs, thereby ensuring bone homeostasis. For example, although TNF-α is an important inflammatory cytokine (discussed in detail below), mice lacking TNF-α have higher bone mass at baseline, indicating a modulatory role in normal conditions as well (88). Thus, it is the imbalance in the levels or actions of osteoclastogenic factors that causes bone pathology, as discussed below.

Reciprocal regulation of OC and immune cells

Although osteoblast lineage cells have the strongest influence on OC development in homeostatic conditions, several immune cell types can influence this process too. Indeed, B cells (89) and activated T cells express RANKL (90–92), but ablation of RANKL expression from these cells does not affect bone mass at baseline through 7 months of age (89). Thus, lymphocyte-produced RANKL, as well as other cytokines, is likely important only in pathological bone loss. Nevertheless, in basal conditions, mice which lack T cells or B cells are osteopenic, at least in part due to reduced OPG production by B cells (93–96), indicating that lymphocytes play a role in bone homeostasis, acting to protect bone. There are many different subsets of T cells, and those that appear to have the dominant role in protecting bone are regulatory T cells. These T cells, that act to reduce effector T cell activity, differentiate from naïve CD4+T cells or CD8+T cells, are referred to as Treg and Tcreg, respectively, and express the transcription factor Forkhead box protein 3 (FoxP3) and CD25. The CD4+ Treg have been more extensively studied, and in many contexts they suppress OC formation and inflammatory osteolysis (97–100). The CD8+ Tcreg also inhibit OC differentiation and bone resorption in vitro and vivo in murine models (101–103). Moreover, forced expression of Foxp3 hinders OC differentiation (99) whereas loss-of-function of this protein causes severe osteoporosis, owing to the hypersensitivity of OC precursor pools to M-CSF (Chen, Cell Death & Disease, in press). Thus, regulatory T cells may limit bone resorption by affecting OC at multiple stages.

Interestingly, the relationship between OC and T cells appears to be bidirectional. Indeed, OC express major histocompatibility complex (MHC) classes I and II, co-stimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86, and are capable of presenting antigens. Cross presentation of antigens by OC leads naive CD8+ T cells to become Tcreg, which in turn inhibit bone resorption (102, 103). OC can also activate alloreactive CD4+ T cells, and CD8+ T cells to some extent, and suppress the ability of CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells to produce TNF-α and IFN-γ, respectively (104, 105). A recent study shows that the suppressive function of OC is inducible as it is triggered by activated T cell-derived IFN-γ and CD40 ligand (106). Whether the immune modulating function of OC is important at baseline, or only in disease states, remains an open question that is difficult to answer since there does not appear to be a unique molecule responsible and OC-specific conditional knockouts have not yet been studied.

Mechanisms of bone resorption

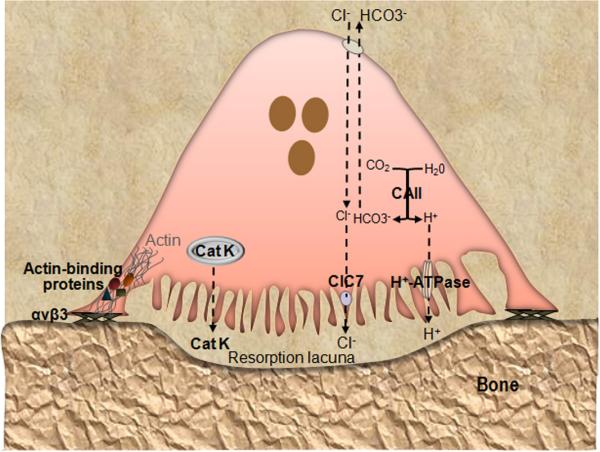

As noted earlier, terminal OC differentiation occurs on the bone surface. OC adhesion to bone is mainly mediated by the αvβ3 integrin, which recognizes the amino acid motif Arg-Gly-Asp contained in certain bone extracellular matrix proteins, including vitronectin, osteopontin, bone sialoprotein, and denatured collagen I. Although the αv subunit is expressed throughout differentiation, the β3 subunit is potently up-regulated downstream of RANKL and serves as a marker of OC differentiation. Accordingly, mice lacking the β3 subunit develop high bone mass late in life due to defective OC adhesion to bone matrix, diminishing their resorptive activity (107). The bone resorption phase starts with dramatic morphological changes in OC, a process referred to as OC polarization whereby a segment of the plasma membrane facing bone expands and becomes highly convoluted (and known as ruffled border) whereas the portion toward the marrow space, the basolateral membrane, is enriched in ion transporters (Fig. 2). The ruffled border is formed by fusion of secretory lysosomes with the plasma membrane in a process controlled by the autophagy machinery (108). This specialized membrane domain is surrounded by actin microfilaments and actin-binding proteins such as talin (109), vinculin (110), kindlin 3 (111), myosin IIA (112, 113) and paxillin (113) organized as podosomes, which cluster to form the actin ring, a dense cytoskeletal structure that excludes all organelles, also called the sealing zone (67). Loss of any of these actin-associated proteins in the podosome diminishes bone resorption, although they have distinct roles in organizing the cytoskeleton.

Figure 2.

Key molecules involved in OC function. Loss-of-function of any of the depicted molecules causes osteopetrosis due to defective OC activity. OC adhere to bone matrix proteins via integrin αvβ3 and polarized such that the plasma membrane facing bone is convoluted (ruffled) and contains the proton pump (v-ATPase) and Cl− channel 7 (ClC7), whereas the basolateral membrane is bears the HCO3−/Cl− antiporter. Cytoplasmic carbonic anhydrase type II (CAII) generates the protons to be secreted into the resorption lacuna beneath the cell. This lacuna becomes isolated from the rest of the extracellular space by the tight adhesion of αvβ3 to the bone surface at the sealing zone. The cytoplasmic domain of β3 recruits signaling proteins, which induce the association of actin with interacting partners (including talin, vinculin, kindlin, myosin IIA and paxillin), and formation of an actin ring that defines the periphery of the ruffled membrane. Concerted action of ClC7 and v-ATPase produces a high concentration of HCl that acidifies the resorption lacuna, leading to the dissolution of the inorganic components of the bone matrix. Acidified cytoplasmic vesicles containing lysosomal enzymes such as cathepsin K (Cat K) are also transported toward the bone-apposed plasma membrane, and ultimately, the sealed resorption lacuna, where they digest the exposed matrix proteins.

During the process of cytoskeletal reorganization, activated β3 recruits to its cytoplasmic domain a variety of signaling proteins, including tyrosine kinases (c-Src and Syk), guanine nucleotide exchange factors, primarily Vav3 (114), leading to activation Rac and formation of the actin ring (115). Mice lacking c-Src, Syk or Vav3 (114, 116, 117) exhibit higher bone mass due to defective resorption, which requires adhesion to bone, cell spreading and actin ring formation (Fig. 2). ITAM signaling is required for these signaling events downstream of the integrin (118). Interestingly, however, the two ITAMs, DAP12 and FcRγ, do not work identically. FcRγ requires the presence of β3 integrin to compensate for the absence of DAP12, while DAP12 can function with β1 integrin to mediate cytoskeletal organization (118). OC cytoskeletal reorganization is also indirectly regulated by M-CSF, which through c-Fms activates β3 integrin intracellularly, causing conformational changes to its extracellular ligand-binding region (inside-out activation). M-CSF stimulates phosphorylation of DAP12 by c-Src and its recruitment to the cytoplasmic tail of c-Fms, leading to activation of Syk and downstream signals to the cytoskeleton. This interaction with c-Fms is another example of differences between DAP12 and FcRγ, as the latter is not able to form this complex (82). In sum, αvβ3 integrin, c-Fms, and ITAM proteins work together to control the OC cytoskeleton, which mediates attachment to bone, migration along the surface, and formation of the actin ring to allow bone resorption.

OC polarization enables directed transport of acidified cytoplasmic vesicles toward the bone-apposed plasma membrane, i.e. at the ruffled border (119). The sealing zone creates an isolated extracellular microenvironment, enclosed by the cell and the bone surface, where bone resorption takes place in two steps. First, the acidification of the resorption lacuna leads to dissolution of the inorganic components of the bone matrix, including hydroxyapatite (119, 120). During this process, carbonic anhydrase type II generates protons and HCO3− by hydrating CO2 (121). The protons are released into the resorptive compartment via an electrogenic proton pump mediated by vacuolar H+-ATPase (v-H+-ATPase), contained in vesicles which fuse with and expand the ruffled border (120, 122). The combined actions of the Cl−/HCO3− anion exchanger and Cl− channel (ClC-7) located on the basolateral membrane and ruffled membrane, respectively, ensure OC cytoplasmic pH neutrality as the Cl− ions are released in the resorption lacuna. The most common forms of osteopetrosis in humans are caused by mutations in genes controlling acidification, including TCIRG1, CLCN7, and OSTM1 (123), emphasizing the importance of this step. Other rare forms of osteopetrosis include mutations in Pleckhm 1, which is involved is lysosomal trafficking (124, 125). HCl-mediated demineralization exposes the organic phase of the bone matrix, which is made up of approximately 95% of type I collagen. The degradation of bone matrix proteins is carried out by secreted lysosomal enzymes (122), mainly the cysteine protease cathepsin K. Indeed, deficiency of cathepsin K in humans causes pycnodysostosis, a high bone mass disease that can be mimicked in mouse models (14, 15, 126). Additionally, there is evidence that neutral matrix metalloproteinases (MMP), including MMP-2, -9 and -13, may also participate in bone resorption (127, 128).

Both the organic and inorganic degradation products from bone extracellular matrix are endocytosed by the ruffled membrane (129, 130), a trafficking process involving small GTPases and microtubules, and released from the basolateral membrane to the bloodstream. This process enables OC to excrete degraded matrix components while digging deep into bone and maintaining an enclosed resorption site. Some of the collagen I degradation products such as C-telopeptide of type I collagen (CTX-1), can be used as markers of bone resorption in patients (131) and animal models (4). The OC eventually detaches through yet unknown mechanisms, migrates and reinitiates another bone matrix degradation cycle. One potential mechanism for sustained bone resorption may be provided by degradation products of the mineral phase functioning as crystalline danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) that activate pathways such as the inflammasomes, which are expressed by the OC lineage (4, 132–135), and may function as a positive feedback mechanism that amplifies bone resorption.

Coupling of bone formation to bone resorption

In normal bone homeostasis, OC remove old or damaged bone matrix and then osteoblasts replace the matrix to restore the bone to its original state in a process known as the bone remodeling cycle. Thus, it makes sense that OC might send signals to osteoblasts to induce bone formation at sites of resorption. In fact, multiple molecules made or activated by OC have the potential to enhance bone formation, acting on various stages of osteoblast differentiation. TGF-β and IGF-1 are both stored in bone matrix and released by its resorption by OC, with the former acting to promote migration of mesenchymal stem cells to newly resorbed sites (136, 137). TGF-β also induces OC to express CXCL16 and Wnt10b, which induce recruitment and mineralization by osteoblasts, respectively (138, 139). Sphingosine-1-phosphate (140) and collagen triple helix repeat containing 1 (141) have been proposed as possible secreted coupling factors that enhance bone formation. In contrast, semaphorin 4D produced by OC appears to inhibit bone formation (142) and perhaps its role is analogous to that of OPG which limits the OC-promoting actions of RANKL. An additional proposed pathway for OC-osteoblast coupling is via direct cell-cell interactions between Ephrin B2 (on OC) and EphB4 (on osteoblasts). These transmembrane proteins can signal bidirectionally and in vitro experiments show enhanced osteoblast activity (143), but the in vivo evidence for coupling is not strong (144). While more work is required to resolve the specific mechanisms involved, it is clear that OC influence the differentiation and activity of osteoblasts in vivo.

Pathological bone loss

Although other cells are able to secrete matrix degrading enzymes, such as MMPs, it is generally accepted that OC are the primary effectors of bone loss in osteolytic disease states. Furthermore, up-regulation of the osteoclastogenic cytokine RANKL is a common feature in states of abnormal bone loss. Nevertheless, in most cases other cytokines and growth factors that interact directly with OC or their precursors have powerful effects on OC differentiation and function in these conditions, with each disease featuring a different “cocktail” of factors. In fact, both pro- and anti-OC signals may be increased, such that the net effects on bone resorption represent the relative amounts of the various factors. Similarly, bone formation may be increased through the normal coupling mechanisms, or decreased due to opposing effects of cytokines on osteoblasts versus OC. Thus, although the mechanisms for bone loss are complex in most diseases, our discussion here will focus specifically on bone resorption.

By far the most common form of bone loss, osteoporosis, affects a large portion of the elderly population. Although the timing and progression of this disease differs in men and women, age-related changes occur in both sexes and can be largely attributed to effects of estrogen loss, as estrogen acts to maintain bone formation and limit resorption (145). None of the effects of androgen on bone mass are through direct effects on OC (146). In osteoporosis, bone resorption outpaces formation, and drugs that inhibit OC (such as bisphosphonates and denosumab, an anti-RANKL antibody) significantly reduce the risk of fracture in patients (147). Another feature of aging probably linked to low estrogen is an increase in chronic low-grade inflammation, so-called “inflamm-aging” (148, 149). This is characterized by a generalized increase in the number of myeloid cells and cytokine levels, but without overt tissue-specific inflammatory infiltrates. T cells may be an important source of osteoclastogenic cytokines, as T cell production of TNF-α and RANKL is elevated in estrogen-deficient humans and mice (150, 151). Other age-related changes in the immune system, such as a failure of OC to induce Tcreg in the context of estrogen loss, may also contribute to bone loss (102). As will be discussed below, inflammatory cytokines have potent effects on OC, and although the rise in cytokines is likely mechanistically linked to estrogen loss, their effects on OC occur via separate molecular pathways. Much of our current understanding of cellular and molecular mechanisms is based on models of ovariectomy in rodents, which causes acute loss of estrogen and rapid, sustained loss of bone mass, particularly at trabecular sites.

Autoimmune inflammatory diseases, most frequently rheumatoid arthritis (RA), are associated with focal bone loss, and increased numbers of OC are generally found at inflamed bone surfaces. Because inflammatory cytokines (especially TNF-α and IL-1) are often co-regulated or induced in a cascade, activating both positive and negative feedback loops, there are many potential osteoclastogenic mediators present at the same time. Besides the cytokines with direct influence on OC, others including IL-17, generated by Th17 cells, and IL-6, produced by many cell types, act mainly by increasing RANKL produced by local osteoblasts and other stromal cells such as synovial fibroblasts (152, 153). Many cytokine-blocking agents (biologics) are now in clinical use to treat inflammatory arthritic diseases, and have shown efficacy in blocking the associated bone loss (154). Patients with RA also have a higher incidence of osteoporosis (155), and although anti-TNF-α therapies reduce generalized bone loss in these patients, recent studies suggest that the auto-antibodies themselves may initiate bone loss prior to the onset of inflammation (156).

Several murine models of inflammatory arthritis have been useful in advancing our understanding of inflammatory bone loss as they implicate the same cytokines (primarily RANKL, TNF-α, and IL-1) and cells (lymphocytes and myeloid cells). These include collagen-induced arthritis (157) and antigen-induced arthritis (158), both of which involve T cell mediated immune responses, recruitment of innate immune cells, and subsequent osteoclastic bone resorption localized to the joint (typically one knee) in which the antigen is injected. The serum transfer arthritis model (159) is a model of systemic antibody transfer and complement fixation that leads to inflammation and bone erosion in many peripheral joints, in a lymphocyte-independent manner. Antibodies to collagen II can also generate a similar form of arthritis (160). Another model that has been used extensively to study arthritis is the human TNF-α transgenic (hTNF-Tg) mouse (161, 162). In this purely cytokine-driven model, arthritis develops spontaneously and remains chronic for the life of the animal, which is a unique feature of this model. However, since cytokines often affect both the inflammatory component and the OC, many experiments need to be interpreted with caution regarding the direct effects of particular pathways on the osteolytic component of disease. The clearest results regarding effects on OC occur when bone loss can be evaluated in the presence of an intact inflammatory response (163–165). For example, NIK-deficient mice have reduced bone erosion in inflammatory arthritis models. Since they develop inflammation in the serum transfer model, but not in the antigen-induced model, we can conclude that osteolysis is specifically impacted by the loss of NIK only from the serum transfer model. In the end, however, none of the animal models precisely replicates the human disease state, nor captures the heterogeneity of real patient populations.

Joint manifestations also occur in sterile autoinflammatory disorders (166), including neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID), the most severe form of cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS). Cryopyrinopathy disorders are caused by activating-mutations in NLRP3, resulting in systemic inflammation driven by IL-1β and IL-18 over-secretion (166). NOMID patients exhibit prominent skeletal malformations, including short stature and low bone mass (167). Abnormal IL-1 biosynthesis or signaling also cause joint complications in a variety of other auto-inflammatory conditions, including TNF receptor-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS), due to mutations in the TNFRSF1A gene encoding the type 1 TNF receptor (168), familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) induced by mutated Pyrin (169), systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis (170), and Blau syndrome caused by NOD2 mutations (171).

Another very common form of inflammatory bone loss is that associated with periodontitis, a bacteria-driven process. Despite differences in the immune effector cells between periodontitis and autoimmune diseases, the direct modulators of OC are the same (RANKL, TNF-α, and IL-1) (172). Although periodontal bacteria may produce forms of LPS and other TLR activating ligands that could directly stimulate osteoclastogenesis (173), the strong induction of inflammatory cytokines is likely more important for osteolysis as cytokine blockade is effective, at least in animal models (174, 175).

Most types of solid tumors that readily metastasize to bone cause OC-mediated bone loss, also known as tumor-mediated osteolysis (176). Although there are complex interactions among tumor cells and the many cell types in the bone microenvironment that affect tumor growth, interactions with OC have perhaps received the most attention because the clinical consequences of their activity, known as skeletal-related events (e.g., fracture and hypercalcemia) are very significant. Abundant data from animal models of osteolytic metastasis indicate that increased OC activity correlates with higher tumor burden (177, 178), while defects therein reduce it (179, 180). OC inhibitory therapy with bisphosphonates or denosumab is now standard of care for many patients either at high risk or with clinically evident bone metastases, and these reduce skeletal related events (181). Through a variety of mediators and interactions with osteoblast-lineage cells, tumors increase local expression of RANKL and may decrease OPG as well (176). Other factors may include TGF-β which is thought to be another mediator of osteolysis in the tumor microenvironment (discussed below). Additionally, tumors increase the number of MDSC in the bone marrow, and in addition to their role in suppressing anti-tumor immune responses, these immature myeloid cells can serve as OC precursors (32–34).

Multiple myeloma, a highly osteolytic tumor of plasma B cells that originates in the bone marrow, secretes several factors that promote osteoclastogenesis, including Dickoppf-1 (DKK1), macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α), and IL-6. DKK1, which has inhibitory effects on osteoblasts, may also promote osteoclastogenesis through inhibition of β-catenin (182). MIP-1α can directly act on OC precursors to promote differentiation (183, 184). In contrast, the effects of IL-6 appear to be indirect, but its blockade may be useful in targeting tumor growth as well as osteolysis (185). Another interesting feature of multiple myeloma that has therapeutic implications is a commonality of signaling pathways in tumor cells and OC. A current first-line therapy is proteasome inhibition such as with bortezomib, whose mechanisms of action include inhibition of NF-κB, p38, NFATc1, and TRAF6, all pathways that impact osteoclastogenesis. In fact, studies have shown that these drugs have dual anti-tumor and anti-resorptive activity (186–188). Recent studies have shown that activating-mutations in the alternative NF-κB pathway are common in multiple myeloma, and play a role in tumor survival (189, 190). Since this pathway is also important for OC formation and function (191–193), its inhibition could also represent a powerful therapeutic strategy (194).

Modulators of osteoclast differentiation and function

In this section we will discuss several of the most important modulators of OC involved in pathological bone loss. We have chosen only those that bind to receptors on OC or their progenitors, and will not discuss those that are produced by other cells in the microenvironment, such as IL-17, IL-6, and Oncostatin M, but act indirectly and induce expression of RANKL and the inflammatory mediators discussed below.

Estrogen

In vitro studies demonstrated that mature OC express receptors for estrogen, especially, ERα, and respond to this hormone by undergoing apoptosis (195, 196). One study using ERα conditional knockout mice showed that this is due to up-regulation of FasL signaling (197). Further upstream, estrogen blocks differentiation of OC precursors in response to RANKL (198). It also affects the frequency of OC precursors, as more OC can be generated from the bones of ovariectomized mice (199) and from peripheral blood of postmenopausal women (200) than from healthy controls. The relative importance of the estrogen effects on different stages of OC survival and differentiation is not clear. A recent 3-D analysis of in vivo resorption in ovariectomized rats showed an increase in the number of resorption sites (reflecting increased differentiation) with little change in the size of the lacunae (presumably a measure of survival of individual OC), suggesting that perhaps early effects on differentiation that determine initiation are more important than those on OC lifespan (201).

Studies using a variety of mice with tissue specific deletions of ERα demonstrate an interesting and perhaps unexpected difference in the mechanism by which estrogen controls resorption in the cortical and trabecular compartments in females. Deletion of ERα from OC, either in progenitors using lysozyme M-Cre or more mature cells using cathepsin K-Cre, reveals bone loss only at trabecular sites but not in the cortex (197, 202). In contrast, deletion of ERα from OB progenitors, with either Prx1-Cre or osterix-Cre, leads to loss only of cortical bone (203) due to defects in bone formation and a secondary increase in endocortical resorption. The early and rapid bone loss seen at the onset of menopause is largely trabecular. Thus, despite the fact that ERα is deleted since conception in mouse models as opposed to menopausal estrogen decline in humans, these findings suggest that the direct inhibitory effects of estrogen on OC are physiologically important (204). In addition to the direct effects of estrogen on bone cells, this hormone also acts as an immunosuppressive agent, reducing levels of TNF-α and IL-1β whose osteoclastogenic actions are discussed below. Supporting these cytokines as significant mediators of bone loss in vivo, their removal or inhibition not only reduces osteoporosis in mouse models (205), but reduces bone turnover markers in women following acute estrogen withdrawal (206).

TNF-α

Even before the identification of RANKL as the “osteoclast differentiation factor”, TNF-α was recognized for its ability to stimulate bone resorption in vivo and in vitro (207, 208). We now know that TNF-α promotes RANKL and M-CSF expression by osteoblast lineage cells (209, 210), and also acts directly on OC precursors (211–214). Since TNF-α and RANKL, and their respective receptors are highly related, many of the signaling pathways activated by these two cytokines are very similar. Thus, it is not surprising that TNF-α can act with RANKL to promote OC differentiation (26, 215). However, the ability of TNF-α alone to induce osteoclastogenesis is quite low in most cases, due to subtle differences in signaling downstream of RANK and TNFR1. Indeed, RANK recruits TRAF3, allowing NIK-mediated processing of p100 to p52, thereby removing significant brakes on the alternative NF-κB signaling pathway (192). TNFR1 signaling increases expression of p100, but not its processing to p52, in wild type cells. However, in the absence of TRAF3, TNF-α is able to induce OC formation (216). Another molecule that limits the ability of TNF-α to promote osteoclastogenesis is RBP-J. This transcription factor strongly suppresses differentiation downstream of TNF-α but not RANKL, and its removal allows robust osteolysis in response to TNF-α (217). In normal cells, small amounts of RANKL appear to counteract the negative regulation of TNF-α such that the action of the two cytokines is synergistic. However, in conditions in which RANKL is stringently excluded from the system, exposure of precursors to TNF-α prior to RANKL inhibits osteoclastogenesis (26).

IL-1

IL-1, present as α and β isoforms (from distinct gene products), is another cytokine abundantly produced in a number of inflammatory conditions. Although not structurally related to RANKL and TNF-α, IL-1, when bound to its receptor, IL-1R1, activates the same signaling pathways as the other two cytokines, including TRAF6/src, NF-κB, ERK, and PI3K (218). IL-1 does not affect early stages of OC differentiation, likely due to low levels of expression of IL-1R1, which is up-regulated by RANKL, but promotes multinucleation and terminal differentiation of RANKL-treated precursors, even without further RANKL exposure (209, 219, 220). RANKL seems to sensitize NFATc1 to induction by IL-1 (220). Intriguingly, one study showed that ectopic expression of IL-1R1 allows IL-1 to drive osteoclastogenesis, dependent on MITF, but not c-Fos or NFATc1 (221). Since RANKL is likely present in the inflammatory environments in which IL-1 acts in vivo, a significant portion of its osteolytic activity may be due to promotion of bone resorption by mature OC rather than effects on early stages of differentiation. IL-1 appears to support actin ring formation and cell survival (222–224). The cytokine also promotes osteolysis indirectly via osteoblast lineage cells (209), in which IL-1 is an important mediator of TNF-α -induced RANKL expression.

IL-1β is initially produced in a pro-form that must be cleaved by caspase-1 to become mature and active, and this step is tightly controlled by the inflammasomes, including the NLRP3 inflammasome. As described above, activating-mutations of NLRP3 cause NOMID as a consequence of systemic elevation of IL-1β (167). Although high inflammatory cytokine levels certainly contribute to bone loss (4), a mouse model expressing NOMID-mutated NLRP3 in committed OC progenitors lacks inflammation but still demonstrates osteopenia (132). Interestingly, hydroxyapatite particles released from bone activate NLRP3 inflammasome in OC lineage cells (unpublished data), and mature osteoclasts show evidence of active inflammasomes in the absence of inflammatory stimuli (132). Thus, the NLRP3 inflammasome may amplify bone loss through IL-1β-dependent and -independent mechanisms.

TGF-β

TGF-β interacts directly with its receptor on OC progenitors and has significant osteoclastogenic effects. On early progenitors, TGF-β enhances lineage commitment through upregulation of SOCS (225) and RANK expression (226). These early effects may serve to limit differentiation down other lineages such as inflammatory macrophages (227). It also promotes signaling downstream of RANK via interactions between TRAF6, an adaptor for RANK, and Smad3, a transcription factor downstream of TGF-β receptor (228). A more recent study by the Tanaka group using genome-wide analysis of chromatin highlighted cooperativity of Smad2/3 with c-Fos in the promotion of NFATc1 expression (229). MiTF, another transcription factor important for osteoclastogenesis, is also enhanced by TGF-β treatment (230) likely due to activation of p38 (231), providing further mechanisms for promotion of differentiation. However, TGF-β does not appear to promote resorption by mature OC (232). In fact, we have found that stimulation of bone marrow macrophages with TGF-β for as little as 4 hours is sufficient for the full pro-osteoclastogenic effects of this factor (unpublished data).

Some early studies suggested inhibitory actions of TGF-β on OC differentiation, but these were all in complex co-culture or organ culture models in which effects on OC differentiation were likely indirect (233, 234). TGF-β is synthesized by osteoblasts, stored as a latent protein in the bone matrix, and mobilized by OC in an active form. Thus, TGF-β is thought to be an important player in the vicious cycle of osteolytic bone metastasis in which OC action enhances TGF-β release, feeding growth of tumor cells as well as differentiation of more OC. In multiple mouse models, blockade of TGF-β signaling increases bone mass and reduces bone metastasis (235–237). Despite the promise shown in animal models for therapy of bone metastasis, the role of TGF-β in the context of tumors as well as inflammatory diseases is very complex (238). For example, TGF-β may be an important mediator of disseminated tumor cell dormancy such that its inhibition could enhance bone metastasis in some cases (239). Furthermore, the effects of TGF-β or its inhibition in disease settings is complicated by the universality of TGF-β receptor expression. For bone, osteoblasts also mount physiologically relevant responses to TGF-β, and these may be dominant to the effects on OC, for example in renal osteodystrophy (240). In this study, TGF-β neutralization limited downstream signaling in osteoblasts and osteocytes, but not in OC. In diseases such as Marfan's syndrome, mutations in matrix proteins reduce the sequestration of TGF-β and increase free TGF-β levels, causing osteoblast lineage cells to secrete more RANKL, providing another mechanism for osteolytic effects of this factor (241–243). Aberrant activation of TGF-β may also play a role in the bone abnormalities in neurofibromatosis (244).

IFN-γ

OC precursors bear receptors for interferon-γ (IFN- γ), and the direct effects of this cytokine produced by T cells and innate immune cells are strongly inhibitory for osteoclastogenesis in mice (245) and humans (246). However, the net effects of T cells, and in fact even for IFN-γ, on bone resorption are complex. IFN-γ acts on early OC precursors, but prior exposure to RANKL seems to abrogate the inhibitory effects (247). In models of inflammatory bone loss or tumor-mediated osteolysis, IFN-γ has an inhibitory role, and global deletion of its receptor exacerbates disease (245, 248, 249). However, in some contexts this cytokine may support OC activity. IFN-γ has been used with some success to improve bone resorption in patients with osteopetrosis, possibly through induction of superoxide production as a direct effect on OC precursors (250, 251). In conditions of estrogen-deficiency, IFN-γ acts indirectly, causing T cell proliferation and increased TNF-α and RANKL expression that increase bone loss (252, 253). Thus, like TGF-β, the effects of IFN-γ on osteoclasts may be very context dependent.

Conclusion

While members of the myeloid lineage to which OC belong are specialized in the clearance of pathogens and cell debris, the function of OC is to remove damaged or aged components of the bone extracellular matrix, which are then replaced by osteoblasts. These tightly controlled sequential responses ensure that appropriate bone mass and quality is maintained throughout life. Perturbation of this equilibrium in metabolic, inflammatory and neoplastic diseases negatively impacts the skeleton. Despite the elusive identity of the most proximal OC precursors, considerable advances in the field have been achieved, including methods for efficient generation of OC in vitro, and elucidation of the molecular mechanisms that govern OC differentiation, survival and function. OC biology is driven mainly by RANKL and M-CSF, but is modulated by a variety of autocrine, paracrine and hormonal factors in health and disease conditions. Additionally, the active fields of co-stimulatory signaling and epigenetic effects have intersections with OC biology. OC develop and act in a rich microenvironment, and they have important reciprocal interactions with other immune cells and mesenchymal cells that impact homeostasis and disease states. Despite these breakthroughs, we still do not understand how all of the various modulators of the osteoclastogenic process interact at baseline and in disease states. In particular, we lack insight into differences between responses of OC at different sites (e.g., vertebrae vs. long bones) or compartments (cancellous vs. cortical) that are observed with systemic stimuli such as estrogen-deprivation. Further work into the dynamics of the various myeloid populations that can function as OC progenitors may provide further insight into pathological bone loss. Surprisingly, given that osteoporosis is an age-related disease, there is still much to be learned about changes in OC with aging as well. Considering all the newly emerging tools for generating highly manipulable animal models, as well as our ability to use human samples, the coming years should provide answers to many of these questions.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Roberta Faccio for critical reading of the manuscript. We have tried to cite primary research in most cases, but due to the large amount of research in this area we are sure to have missed some important papers. We apologize in advance to authors who have been omitted. We are grateful to support from the National Institutes of Health for funding, AR052705 (to DVN) and AR064755 (to GM).

Literature Cited

- 1.Mosaad YM. Hematopoietic stem cells: an overview. Transfus Apheresis Sci. 2014;51:68–82. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2014.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Demulder A, Takahashi S, Singer FR, Hosking DJ, Roodman GD. Abnormalities in osteoclast precursors and marrow accessory cells in Paget’s disease. Endocrinology. 1993;133:1978–1982. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.5.7691583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Demulder A, Suggs SV, Zsebo KM, Scarcez T, Roodman GD. Effects of stem cell factor on osteoclast-like cell formation in long-term human marrow cultures. J Bone Miner Res. 1992;7:1337–1344. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650071114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonar SL, Brydges SD, Mueller JL, McGeough MD, Pena C, Chen D, Grimston SK, Hickman-Brecks CL, Ravindran S, McAlinden A, Novack DV, Kastner DL, Civitelli R, Hoffman HM, Mbalaviele G. Constitutively activated NLRP3 inflammasome causes inflammation and abnormal skeletal development in mice. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mediero A, Perez-Aso M, Cronstein BN. Activation of EPAC1/2 is essential for osteoclast formation by modulating NFκB nuclear translocation and actin cytoskeleton rearrangements. FASEB J. 2014;28:4901–4913. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-255703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xing L, Boyce B. RANKL-Based Osteoclastogenic Assays from Murine Bone Marrow Cells. In: Hilton MJ, editor. Skeletal Development and Repair. Vol. 1130. Humana Press; 2014. pp. 307–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mabilleau G, Pascaretti-Grizon F, Baslé MF, Chappard D. Depth and volume of resorption induced by osteoclasts generated in the presence of RANKL, TNF-alpha/IL-1 or LIGHT. Cytokine. 2012;57:294–299. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li P, Schwarz EM, O'Keefe RJ, Ma L, Looney RJ, Ritchlin CT, Boyce BF, Xing L. Systemic tumor necrosis factor α mediates an increase in peripheral CD11bhigh osteoclast precursors in tumor necrosis factor α-transgenic mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:265–276. doi: 10.1002/art.11419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henriksen K, Karsdal M, Taylor A, Tosh D, Coxon F. Generation of Human Osteoclasts from Peripheral Blood. In: Ralston SH, editor. Bone Research Protocols. Vol. 816. Humana Press; Helfrich, MH.: 2012. pp. 159–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradley E, Oursler M. Osteoclast Culture and Resorption Assays. In: Westendorf J, editor. Osteoporosis. Vol. 455. Humana Press; 2008. pp. 19–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y, Menendez A, Fong C, ElAlieh HZ, Chang W, Bikle DD. Ephrin B2/EphB4 mediates the actions of IGF-I signaling in regulating endochondral bone formation. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:1900–1913. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayman AR, Jones SJ, Boyde A, Foster D, Colledge WH, Carlton MB, Evans MJ, Cox TM. Mice lacking tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (Acp 5) have disrupted endochondral ossification and mild osteopetrosis. Development. 1996;122:3151–3162. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.10.3151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sago K, Teitelbaum SL, Venstrom K, Reichardt LF, Ross FP. The integrin alphavbeta5 is expressed on avian osteoclast precursors and regulated by retinoic acid. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:32–38. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.1.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saftig P, Hunziker E, Wehmeyer O, Jones S, Boyde A, Rommerskirch W, Moritz JD, Schu P, von Figura K. Impaired osteoclastic bone resorption leads to osteopetrosis in cathepsin-K-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13453–13458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gowen M, Lazner F, Dodds R, Kapadia R, Feild J, Tavaria M, Bertoncello I, Drake F, Zavarselk S, Tellis I, Hertzog P, Debouck C, Kola I. Cathepsin K knockout mice develop osteopetrosis due to a deficit in matrix degradation but not demineralization. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:1654–1663. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.10.1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoff AO, Catala-Lehnen P, Thomas PM, Priemel M, Rueger JM, Nasonkin I, Bradley A, Hughes MR, Ordonez N, Cote G J, Amling M, Gagel RF. Increased bone mass is an unexpected phenotype associated with deletion of the calcitonin gene. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1849–1857. doi: 10.1172/JCI200214218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim N, Takami M, Rho J, Josien R, Choi Y. A novel member of the leukocyte receptor complex regulates osteoclast differentiation. J Exp Med. 2002;195:201–209. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sørensen MG, Henriksen K, Schaller S, Henriksen DB, Nielsen FC, Dziegiel MH, Karsdal MA. Char acterization of osteoclasts derived from CD14+ monocytes isolated from peripheral blood. J Bone Miner Metab. 2007;25:36–45. doi: 10.1007/s00774-006-0725-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McHugh KP, Hodivala-Dilke K, Zheng MH, Namba N, Lam J, Novack D, Feng X, Ross FP, Hynes RO, Teitelbaum SL. Mice lacking β3 integrins are osteosclerotic because of dysfunctional osteoclasts. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:433–440. doi: 10.1172/JCI8905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen THP, Swarnkar G, Mbalaviele G, Abu-Amer Y. Myeloid lineage skewing due to exacerbated NF-[kappa]B signaling facilitates osteopenia in Scurfy mice. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:e1723. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mbalaviele G, Jaiswal N, Meng A, Cheng L, Van Den Bos C, Thiede M. Human mesenchymal stem cells promote human osteoclast differentiation from CD34+ bone marrow hematopoietic progenitors. Endocrinology. 1999;140:3736–3743. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.8.6880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matayoshi A, Brown C, DiPersio JF, Haug J, Abu-Amer Y, Liapis H, Kuestner R, Pacifici R. Human blood-mobilized hematopoietic precursors differentiate into osteoclasts in the absence of stromal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10785–10790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muto A, Mizoguchi T, Udagawa N, Ito S, Kawahara I, Abiko Y, Arai A, Harada S, Kobayashi Y, Nakamichi Y, Penninger JM, Noguchi T, Takahashi N. Lineage-committed osteoclast precursors circulate in blood and settle down into bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:2978–2990. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Durand M, Komarova SV, Bhargava A, Trebec-Reynolds DP, Li K, Fiorino C, Maria O, Nabavi N, Manolson MF, Harrison RE, Dixon SJ, Sims SM, Mi zianty MJ, Kurgan L, Haroun S, Boire G, de Fatima Lucena-Fernandes M, de Brum-Fernandes AJ. Monocytes from patients with osteoarthritis display increased osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption: the In Vitro Osteoclast Differentiation in Arthritis study. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:148–158. doi: 10.1002/art.37722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hemingway F, Cheng X, Knowles HJ, Estrada FM, Gordon S, Athanasou NA. In vitro generation of mature human osteoclasts. Calcif Tissue Int. 2011;89:389–395. doi: 10.1007/s00223-011-9530-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lam J, Takeshita S, Barker JE, Kanagawa O, Ross FP, Teitelbaum SL. TNF-α induces osteoclastogenesis by direct stimulation of macrophages exposed to permissive levels of RANK ligand. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:1481–1488. doi: 10.1172/JCI11176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Charles JF, Hsu L-Y, Niemi EC, Weiss A, Aliprantis AO, Nakamura MC. Inflammatory arthritis increases mouse osteoclast precursors with myeloid suppressor function. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:4592–4605. doi: 10.1172/JCI60920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacome-Galarza CE, Lee S-K, Lorenzo JA, Aguila HL. Identification, characterization, and isolation of a common progenitor for osteoclasts, macrophages, and dendritic cells from murine bone marrow and periphery. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28:1203–1213. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacquin C, Gran DE, Lee SK, Lorenzo JA, Aguila HL. Identification of multiple osteoclast precursor populations in murine bone marrow. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:67–77. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.051007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takahashi N, Udagawa N, Tanaka S, Murakami H, Owan I, Tamura T, Suda T. Postmitotic osteoclast precursors are mononuclear cells which express macrophage-associated phenotypes. Dev Biol. 1994;163:212–221. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park-Min K-H, Lee EY, Moskowitz NK, Lim E, Lee SK, Lorenzo JA, Huang C, Melnick AM, Purdue PE, Goldring SR, Ivashkiv LB. Negative regulation of osteoclast precursor differentiation by CD11b and β2 integrin-B-cell lymphoma 6 signaling. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28:135–149. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhuang J, Zhang J, Lwin ST, Edwards JR, Edwards CM, Mundy GR, Yang X. Osteoclasts in multiple myeloma are derived from Gr-1+CD11b+myeloid-derived suppressor cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48871. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sawant A, Deshane J, Jules J, Lee CM, Harris BA, Feng X, Ponnazhagan S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells function as novel osteoclast progenitors enhancing bone loss in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73:672–682. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Danilin S, Merkel AR, Johnson JR, Johnson RW, Edwards JR, Sterling JA. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells expand during breast cancer progression and promote tumor-induced bone destruction. OncoImmunology. 2012;1:1484–1494. doi: 10.4161/onci.21990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yagi M, Miyamoto T, Sawatani Y, Iwamoto K, Hosogane N, Fujita N, Morita K, Ninomiya K, Suzuki T, Miyamoto K, Oike Y, Takeya M, Toyama Y, Suda T. DC-STAMP is essential for cell-cell fusion in osteoclasts and foreign body giant cells. J Exp Med. 2005;202:345–351. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miyamoto H, Suzuki T, Miyauchi Y, Iwasaki R, Kobayashi T, Sato Y, Miyamoto K, Hoshi H, Hashimoto K, Yoshida S, Hao W, Mori T, Kanagawa H, Katsuyama E, Fujie A, Morioka H, Matsumoto M, Chiba K, Takeya M, Toyama Y, Miyamoto T. Osteoclast stimulatory transmembrane protein and dendritic cell–specific transmembrane protein cooperatively modulate cell–cell fusion to form osteoclasts and foreign body giant cells. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:1289–1297. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mbalaviele G, Chen H, Boyce BF, Mundy GR, Yoneda T. The role of cadherin in the generation of multinucleated osteoclasts from mononuclear precursors in murine marrow. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:2757–2765. doi: 10.1172/JCI117979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van den Bossche J, Malissen B, Mantovani A, De Baetselier P, Van Ginderachter JA. Regulation and function of the E-cadherin/catenin complex in cells of the monocyte-macrophage lineage and DCs. 2012;119 doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-384289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakamura H, Nakashima T, Hayashi M, Izawa N, Yasui T, Aburatani H, Tanaka S, Takayanagi H. Global epigenomic analysis indicates protocadherin-7 activates osteoclastogenesis by promoting cell-cell fusion. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;455:305–311. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ishizuka H, García-Palacios V, Lu G, Subler MA, Zhang H, Boykin CS, Choi SJ, Zhao L, Patrene K, Galson DL, Blair HC, Hadi TM, Windle JJ, Kurihara N, Roodman GD. ADAM8 enhances osteoclast precursor fusion and osteoclast formation in vitro and in vivo. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:169–181. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ishii M, Egen JG, Klauschen F, Meier-Schellersheim M, Saeki Y, Vacher J, Proia RL, Germain RN. Sphingosine-1-phosphate mobilizes osteoclast precursors and regulates bone homeostasis. Nature. 2009;458:524–528. doi: 10.1038/nature07713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ishii M, Kikuta J, Shimazu Y, Meier-Schellersheim M, Germain RN. Chemorepulsion by blood S1P regulates osteoclast precursor mobilization and bone remodeling in vivo. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2793–2798. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ishii M, Kikuta J. Sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling controlling osteoclasts and bone homeostasis. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) -. Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2013;1831:223–227. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shahnazari M, Chu V, Wronski TJ, Nissenson RA, Halloran BP. CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling in the osteoblast regulates the mesenchymal stem cell and osteoclast lineage populations. FASEB J. 2013;27:3505–3513. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-225763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takahashi N, Akatsu T, Udagawa N, Sasaki T, Yamaguchi A, Moseley JM, Martin TJ, Suda T. Oste oblastic cells are involved in osteoclast formation. Endocrinology. 1988;123:2600–2602. doi: 10.1210/endo-123-5-2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Udagawa N, Takahashi N, Akatsu T, Tanaka H, Sasaki T, Nishihara T, Koga T, Martin TJ, Suda T. Origin of osteoclasts: mature monocytes and macrophages are capable of differentiating into osteoclasts under a suitable microenvironment prepared by bone marrow-derived stromal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7260–7264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.18.7260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wiktor-Jedrzejczak WW, Ahmed A, Szczylik C, Skelly RR. Hematological characterization of congenital osteopetrosis in op/op mouse. Possible mechanism for abnormal macrophage differentiation. J Exp Med. 1982;156:1516–1527. doi: 10.1084/jem.156.5.1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoshida H, Hayashi S, Kunisada T, Ogawa M, Nishikawa S, Okamura H, Sudo T, Shultz LD, Nishikawa S. The murine mutation osteopetrosis is in the coding region of the macrophage colony stimulating factor gene. Nature. 1990;345:442–444. doi: 10.1038/345442a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Felix R, Cecchini MG, Hofstetter W, Elford PR, Stutzer A, Fleisch H. J Bone Miner Res. Vol. 5. Rapid publication; 1990. Impairment of macrophage colony-stimulating factor production and lack of resident bone marrow macrophages in the osteopetrotic op/op mouse. pp. 781–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stanley ER, Chitu V. CSF-1 receptor signaling in myeloid cells. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014;6:6. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a021857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Otero K, Turnbull IR, Poliani PL, Vermi W, Cerutti E, Aoshi T, Tassi I, Takai T, Stanley SL, Miller M, S haw AS, Colonna M. Macrophage colony-stimulating factor induces the proliferation and survival of macrophages via a pathway involving DAP12 and beta-catenin. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:734–743. doi: 10.1038/ni.1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Glantschnig H, Fisher JE, Wesolowski G, Rodan GA, Reszka AA. M-CSF, TNFalpha and RANK ligand promote osteoclast survival by signaling through mTOR/S6 kinase. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:1165–1177. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zamani A, Decker C, Cremasco V, Hughes L, Novack DV, Faccio R. Diacylglycerol Kinase ζ (DGKζ) Is a Critical Regulator of Bone Homeostasis Via Modulation of c-Fos Levels in Osteoclasts. J Bone Miner Res. 2015;30:1852–1863. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baud'huin M, Renault R, Charrier C, Riet A, Moreau A, Brion R, Gouin F, Duplomb L, Heymann D. Interleukin-34 is expressed by giant cell tumours of bone and plays a key role in RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis. J Pathol. 2010;221:77–86. doi: 10.1002/path.2684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen Z, Buki K, Vääräniemi J, Gu G, Väänänen HK. The critical role of IL-34 in osteoclastogenesis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18689. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li J, Chen K, Zhu L, Pollard JW. Conditional deletion of the colony stimulating factor-1 receptor (cfms proto-oncogene) in mice. genesis. 2006;44:328–335. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee MS, Kim HS, Yeon J-T, Choi S-W, Chun CH, Kwak HB, Oh J. GM-CSF regulates fusion of mononuclear osteoclasts into bone-resorbing osteoclasts by activating the Ras/ERK pathway. J Immunol. 2009;183:3390–3399. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Niida S, Kaku M, Amano H, Yoshida H, Kataoka H, Nishikawa S, Tanne K, Maeda N, Nishikawa S, Koda ma H. Vascular endothelial growth factor can substitute for macrophage colony-stimulating factor in the support of osteoclastic bone resorption. J Exp Med. 1999;190:293–298. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.2.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nakagawa M, Kaneda T, Arakawa T, Morita S, Sato T, Yomada T, Hanada K, Kumegawa M, Hakeda Y. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) directly enhances osteoclastic bone resorption and survival of mature osteoclasts. FEBS Lett. 2000;473:161–164. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01520-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Adamopoulos IE, Xia Z, Lau YS, Athanasou NA. Hepatocyte growth factor can substitute for M-CSF to support osteoclastogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;350:478–483. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.09.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lacey DL, Timms E, Tan HL, Kelley MJ, Dunstan CR, Burgess T, Elliott R, Colombero A, Elliott G, Scully S, Hsu H, Sullivan J, Hawkins N, Davy E, Capparelli C, Eli A, Qian YX, Kaufman S, Sarosi I, Shalhou b V, Senaldi G, Guo J, Delaney J, Boyle WJ. Osteoprotegerin ligand is a cytokine that regulates osteoclast differentiation and activation. Cell. 1998;93:165–176. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yasuda H, Shima N, Nakagawa N, Yamaguchi K, Kinosaki M, Mochizuki S, Tomoyasu A, Yano K, Goto M, Murakami A, Tsuda E, Morinaga T, Higashio K, Udagawa N, Takahashi N, Suda T. Osteoclast differentiation factor is a ligand for osteoprotegerin/osteoclastogenesis-inhibitory factor and is identical to TRANCE/RANKL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3597–3602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kong Y-Y, Yoshida H, Sarosi I, Tan H-L, Timms E, Capparelli C, Morony S, Oliveira-dos-Santos AJ, Van G, Itie A, Khoo W, Wakeham A, Dunstan CR, Lacey DL, Mak TW, Boyle WJ, Penninge r JM. OPGL is a key regulator of osteoclastogenesis, lymphocyte development and lymph-node organogenesis. Nature. 1999;397:315–323. doi: 10.1038/16852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bucay N, Sarosi I, Dunstan CR, Morony S, Tarpley J, Capparelli C, Scully S, Tan HL, Xu W, Lacey DL, Boyle WJ, Simonet WS. osteoprotegerin-deficient mice develop early onset osteoporosis and arterial calcification. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1260–1268. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.9.1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Whyte MP, Tau C, McAlister WH, Zhang X, Novack DV, Preliasco V, Santini-Araujo E, Mumm S. Juvenile Paget's disease with heterozygous duplication within TNFRSF11A encoding RANK. Bone. 2014;68:153–161. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hughes AE, Ralston SH, Marken J, Bell C, MacPherson H, Wallace RGH, van Hul W, Whyte MP, Nakatsuka K, Hovy L, Anderson DM. Mutations in TNFRSF11A, affecting the signal peptide of RANK, cause familial expansile osteolysis. Nat Genet. 2000;24:45–48. doi: 10.1038/71667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Novack DV, Teitelbaum SL. The osteoclast: friend or foe? Annu Rev Pathol. 2008;3:457–484. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.151431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Smink JJ, Bégay V, Schoenmaker T, Sterneck E, de Vries TJ, Leutz A. Transcription factor C/EBPβ isoform ratio regulates osteoclastogenesis through MafB. 2009;28 doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Smink JJ, Tunn P-U, Leutz A. Rapamycin inhibits osteoclast formation in giant cell tumor of bone through the C/EBPβ - MafB axis. J Mol Med Berl. 2012;90:25–30. doi: 10.1007/s00109-011-0823-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Takayanagi H, Kim S, Koga T, Nishina H, Isshiki M, Yoshida H, Saiura A, Isobe M, Yokochi T, Inoue J, Wagner EF, Mak TW, Kodama T, Taniguchi T. Induction and activation of the transcription factor NFATc1 (NFAT2) integrate RANKL signaling in terminal differentiation of osteoclasts. Dev Cell. 2002;3:889–901. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00369-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mao D, Epple H, Uthgenannt B, Novack DV, Faccio R. PLCgamma2 regulates osteoclastogenesis via its interaction with ITAM proteins and GAB2. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2869–2879. doi: 10.1172/JCI28775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Alhawagri M, Yamanaka Y, Ballard D, Oltz E, Abu-Amer Y. Lysine392, a K63-linked ubiquitination site in NEMO, mediates inflammatory osteoclastogenesis and osteolysis. J Orthop Res. 2012;30:554–560. doi: 10.1002/jor.21555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bronisz A, Carey HA, Godlewski J, Sif S, Ostrowski MC, Sharma SM. The multifunctional protein fused in sarcoma (FUS) is a coactivator of microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF). J Biol Chem. 2014;289:326–334. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.493874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yasui T, Hirose J, Aburatani H, Tanaka S. Epigenetic regulation of osteoclast differentiation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1240:7–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kim JH, Kim N. Regulation of NFATc1 in Osteoclast Differentiation. J Bone Metab. 2014;21:233–241. doi: 10.11005/jbm.2014.21.4.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mizoguchi F, Izu Y, Hayata T, Hemmi H, Nakashima K, Nakamura T, Kato S, Miyasaka N, Ezura Y, Nod a M. Osteoclast-specific Dicer gene deficiency suppresses osteoclastic bone resorption. J Cell Biochem. 2010;109:866–875. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nishikawa K, Iwamoto Y, Kobayashi Y, Katsuoka F, Kawaguchi S, Tsujita T, Nakamura T, Kato S, Yam amoto M, Takayanagi H, Ishii M. DNA methyltransferase 3a regulates osteoclast differentiation by coupling to an S-adenosylmethionine-producing metabolic pathway. Nat Med. 2015;21:281–287. doi: 10.1038/nm.3774. advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yasui T, Hirose J, Tsutsumi S, Nakamura K, Aburatani H, Tanaka S. Epigenetic regulation of osteoclast differentiation: possible involvement of Jmjd3 in the histone demethylation of Nfatc1. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:2665–2671. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Park-Min K-H, Lim E, Lee MJ, Park SH, Giannopoulou E, Yarilina A, van der Meulen M, Zhao B, Smithers N, Witherington J, Lee K, Tak PP, Prinjha RK, Ivashkiv LB. Inhibition of osteoclastogenesis and inflammatory bone resorption by targeting BET proteins and epigenetic regulation. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5418. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shakibaei M, Buhrmann C, Mobasheri A. Resveratrol-mediated SIRT-1 interactions with p300 modulate receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand (RANKL) activation of NF-kappaB signaling and inhibit osteoclastogenesis in bone-derived cells. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:11492–11505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.198713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hah Y-S, Cheon Y-H, Lim HS, Cho HY, Park B-H, Ka S-O, Lee Y-R, Jeong D-W, Kim H-O, Han MK, Lee S-I. Myeloid deletion of SIRT1 aggravates serum transfer arthritis in mice via nuclear factor-κB activation. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87733. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zou W, Reeve JL, Liu Y, Teitelbaum SL, Ross FP. DAP12 couples c-Fms activation to the osteoclast cytoskeleton by recruitment of Syk. Mol Cell. 2008;31:422–431. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mócsai A, Humphrey MB, Van Ziffle JAG, Hu Y, Burghardt A, Spusta SC, Majumdar S, Lanier LL, Lowell CA, Nakamura MC. The immunomodulatory adapter proteins DAP12 and Fc receptor γ-chain (FcRgamma) regulate development of functional osteoclasts through the Syk tyrosine kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:6158–6163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401602101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Koga T, Inui M, Inoue K, Kim S, Suematsu A, Kobayashi E, Iwata T, Ohnishi H, Matozaki T, Kodama T, Taniguchi T, Takayanagi H, Takai T. Costimulatory signals mediated by the ITAM motif cooperate with RANKL for bone homeostasis. Nature. 2004;428:758–763. doi: 10.1038/nature02444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wu Y, Torchia J, Yao W, Lane NE, Lanier LL, Nakamura MC, Humphrey MB. Bone microenvironment specific roles of ITAM adapter signaling during bone remodeling induced by acute estrogen-deficiency. PLoS One. 2007;2:e586. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Li S, Miller CH, Giannopoulou E, Hu X, Ivashkiv LB, Zhao B. RBP-J imposes a requirement for ITAM-mediated costimulation of osteoclastogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:5057–5073. doi: 10.1172/JCI71882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zou W, Teitelbaum SL. Absence of Dap12 and the αvβ3 integrin causes severe osteopetrosis. J Cell Biol. 2015;208:125–136. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201410123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Li Y, Li A, Strait K, Zhang H, Nanes MS, Weitzmann MN. Endogenous TNFalpha lowers maximum peak bone mass and inhibits osteoblastic Smad activation through NF-kappaB. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:646–655. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]