Abstract

Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) is the most widely used biomaterial for microencapsulation and prolonged delivery of therapeutic drugs, proteins and antigens. PLGA has excellent biodegradability and biocompatibility and is generally recognized as safe by international regulatory agencies including the United States Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency. The physicochemical properties of PLGA may be varied systematically by changing the ratio of lactic acid to glycolic acid. This in turn alters the release rate of microencapsulated therapeutic molecules from PLGA microparticle formulations. The obstacles hindering more widespread use of PLGA for producing sustained-release formulations for clinical use include low drug loading, particularly of hydrophilic small molecules, high initial burst release and/or poor formulation stability. In this review, we address strategies aimed at overcoming these challenges. These include use of low-temperature double-emulsion methods to increase drug-loading by producing PLGA particles with a small volume for the inner water phase and a suitable pH of the external phase. Newer strategies for producing PLGA particles with high drug loading and the desired sustained-release profiles include fabrication of multi-layered microparticles, nanoparticles-in-microparticles, use of hydrogel templates, as well as coaxial electrospray, microfluidics, and supercritical carbon dioxide methods. Another recent strategy with promise for producing particles with well-controlled and reproducible sustained-release profiles involves complexation of PLGA with additives such as polyethylene glycol, poly(ortho esters), chitosan, alginate, caffeic acid, hyaluronic acid, and silicon dioxide.

Keywords: PLGA microparticles, drug delivery system, hydrophilic molecule, biodegradation mechanisms, tuneable release, microfluidics, supercritical carbon dioxide, hydrogel template

Introduction

Drug delivery systems with high efficiency and tuneable release characteristics continue to be sought. This is despite recent advances in the field of nanobiotechnology that have produced a range of new materials for improving control over drug delivery rates (Hillery et al., 2005). The strategies used to produce these sustained-release dosage forms involve drug loading of biodegradable polymeric microspheres and have the potential to provide a more facile route to adjust release rates (Kapoor et al., 2015).

Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), is a widely used biodegradable material use for encapsulation of a broad range of therapeutic agents including hydrophilic and hydrophobic small molecule drugs, DNA, proteins, and the like (Zheng, 2009; Malavia et al., 2015), due to its excellent biocompatibility (Barrow, 2004; Kapoor et al., 2015). Complete release of encapsulated molecules is achieved via degradation and erosion of the polymer matrix (Anderson and Shive, 1997, 2012; Fredenberg et al., 2011). Importantly, PLGA is generally recognized as safe by international regulatory agencies such as the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for use in pharmaceutical products administered to humans via conventional oral and parenteral routes (Yun-Seok et al., 2010) as well as suspension formulations for implantation without surgical procedures (Freiberg and Zhu, 2004).

However, factors limiting more widespread use of PLGA in pharmaceutical products include relatively low drug loading efficiency, difficulties in controlling encapsulated drug release rates and/or formulation instability (Varde and Pack, 2004; Freitas et al., 2005; Yun-Seok et al., 2010; Ansari et al., 2012; Danhier et al., 2012; Reinhold and Schwendeman, 2013). In the following sections, we review strategies and new technologies with promise for addressing these issues.

Challenges in improving drug loading of microparticles with acceptable control over release rate profiles

Physicochemical properties of the incorporated drug(s)

Achieving the desired loading of low molecular weight (Mr), hydrophilic molecules in polymeric particles is more difficult than for hydrophobic small molecules, despite the large number of micro-encapsulation methods described in peer-reviewed publications and patents (Ito et al., 2011; Ansari et al., 2012). Manipulation of the physicochemical properties is often the most effective means for optimizing drug loading into PLGA microspheres (Curley et al., 1996; Govender et al., 1999). For example, small molecules that are hydrophilic in their salt form can be converted to the corresponding free acid or free base forms that are more hydrophobic, subsequently leading to higher drug loading (Han et al., 2015). The physicochemical properties of the incorporated drug(s) also significantly affect release rate profiles (Hillery et al., 2005).

For PLGA microparticles, release of the encapsulated drug occurs via diffusion and/or homogeneous bulk erosion of the biopolymer (Siegel et al., 2006; Kamaly et al., 2016) with the diffusion rate dependent upon drug diffusivity and partition coefficient (Hillery et al., 2005). These parameters are influenced by the physicochemical properties of the drug, such as molecular size, hydrophilicity, and charge (Hillery et al., 2005). A relatively high content of a water-soluble drug facilitates water penetration into particles and formation of a highly porous polymer network upon drug leaching (Feng et al., 2015). By contrast, hydrophobic drugs can hinder water diffusion into microparticulate systems and reduce the rate of polymer degradation (Klose et al., 2008). This is illustrated by observations that for six drugs with diverse chemical structures, viz. thiothixene, haloperidol, hydrochlorothiozide, corticosterone, ibuprofen and aspirin, there were significant between-molecule differences in release rate from PLGA (50:50) pellets, despite their similar drug loading at 20% by weight (Siegel et al., 2006). Hence, the design of biodegradable polymeric carriers with high drug loading must take into consideration the effects of the encapsulated drug itself on the mechanisms underpinning biopolymer degradation that influence release rate (Siegel et al., 2006).

Particle size

Key factors in the design of microparticle drug delivery systems include microsphere size and morphology (Langer et al., 1986; Shah et al., 1992; Mahboubian et al., 2010) as these parameters potentially affect encapsulation efficiency (EE), product injectability, in vivo biodistribution, and encapsulated drug release rate (Nijsen et al., 2002; Barrow, 2004), efficacy and side-effect profiles (Liggins et al., 2004). Typically, optimal release profiles are achieved by using microspheres with diameters in the range, 10–200 μm (Anderson and Shive, 1997). For particle diameters < 10 μm, there is a risk that microspheres will be phagocytosed by immune cells (Dawes et al., 2009). On the other hand, microspheres >200 μm may cause an immune response and inflammation (Dawes et al., 2009).

For large diameter particles, the small surface area per unit volume leads to a reduced rate of water permeation and matrix degradation relative to smaller particles and so the maximum possible rate of encapsulated drug release is reduced (Dawes et al., 2009). For drugs microencapsulated in larger microparticles, duration of action is potentially longer due to higher total drug loading and a longer particle degradation time (Klose et al., 2006). Hence, a good understanding of the relationship between biopolymer composition, microparticle morphology and size is essential for tailored production of particulate materials with pre-determined drug release profiles (Cai et al., 2009). However, based upon the diversity of encapsulated drug release profiles produced by PLGA microspheres of varying sizes to date (Table 1), release rates do not necessarily conform to predicted behavior and it is only possible to quantitatively predict the effect of microparticle size on drug release kinetics for certain well-defined formulations (Siepmann et al., 2004).

Table 1.

Influence of particle size, polymer physicochemical properties as well as PLGA composition on drug loading and release profiles.

| (1) Particle size | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug loading and release rates from PLGA particles do not necessarily conform to predicted behavior as the effect of microparticle size on drug release kinetics quantitatively can only be predicted for certain well-defined formulations. | ||||

| Encapsulated drug | Particle size (μm) | Drug loading or EE | Drug release profile | References |

| Lidocaine | Increase from 20 to 50 to 120 | N/A | Release rate ↓ as particle size ↑ | Klose et al., 2006 |

| Huperzine A | Increase from 125–200 to 200–400 to 400–700 | EE ↑ | Release rate ↓ as particle size ↑ | Fu et al., 2005 |

| Dexamethasone | 1.0 | 11% | Slow-release particles but with initial burst release | Dawes et al., 2009 |

| 20 | 1% | Sustained release over a 550 h period | ||

| 5-fluorouracil | 70–120 | 35% | ~90% release in 7 days | Siepmann et al., 2004 |

| 20 | 20% | 90% release over 21days | ||

| Drug-free | < 50, < 20 and < 1 (each size prepared by a different process) | N/A | At pH 7.4 and 37°C, ↑ polymer degradation rate for larger microspheres | Dunne et al., 2000 |

| (2) Physicochemical properties of the biopolymer | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The hydrophilicity or hydrophobicity of PLGA end-groups affect hydration during the pore diffusion phase thereby influencing the rate of drug release from the polymeric matrix. PLGA composition-dependent changes to microparticle morphology may also affect encapsulated drug release profiles. | ||||

| Encapsulated drug | PLGA Composition | Effect on particle size, drug loading and release profile | References | |

| FITC-dextran | PLGA (50:50) with a carboxylic acid-end group, viz RG503H (Mr 24000-38000) | Sustained release achieved by ↑ porosity, pore size, and loading | Cai et al., 2009 | |

| PLGA (50:50) with an ester-end group, viz RG502 (Mr 7000–17000) | Porosity and pore size had a minimal effect on release profile beyond initial release | |||

| Huperzine A | PLGA (75:25) of varying Mr, viz 15, 20, and 30 kDa | Drug loadings of 3.53, 1.03, and 0.41% respectively; inversely correlated with Mr | Fu et al., 2005; Ansari et al., 2012 | |

| Cephalexin | ↑ Concentration of PLGA in the organic solvent (chloroform) from 25 to 33.3 mg/ml | Higher drug loading and larger particle size | Wasana et al., 2009 | |

| (3) Recent advances with promise for improving PLGA delivery systems | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methods | Encapsulated drug | Particle size (μm) | Drug loading or EE | Drug release profile | References |

| Hydrogel template | OHR1031 | 60 ± 10 | 57% w/w, ~100% EE | Nearly zero-order for over 3 months, with no initial burst, which was desirable | Malavia et al., 2015 |

| Felodipine, Paclitaxel, Progesterone and Risperidone | 10–50 | 50–65% | Sustained release profiles | Acharya et al., 2010b | |

| scCO2 in combination with a w/o/o/o method | Dexamethasone phosphate | 70–80 | 90% EE | Sustained release profile without initial burst release | Thote and Gupta, 2005 |

| scCO2 | hGH | ~61 | Controlled release for > 7 days | Jordan et al., 2010 | |

| Tetanus toxoid (TT) | Single injection TT-loaded PLA particles in mice antibody titres similar to those evoked by multiple injections of a commercial alum-adsorbed TT vaccine was produced | Baxendale et al., 2011 | |||

| Coaxial electrospray (CES) | Levetiracetam | Double-layered: release over 18-days whereas encapsulation in classical core-shell fibers gave linear release for 4 days followed by steady-state | Viry et al., 2012 | ||

| Growth factors | Controlled-release: Coaxial electrospinning of biodegradable core-shell structured microfibrous scaffolds using PLGA as the shell and hyaluronic acid as the core | Joung et al., 2011 | |||

| Multiple drugs | Coaxial tri-capillary electrospray system produced monodispersed PLGA-coated particles containing multiple drugs in one step | Lee et al., 2011 | |||

| Spray drying | Double-layered enzyme-triggered release in the gastrointestinal tract: Negligible loss of the core in the gastric environment with gradual release of the core in the intestinal environment without initial burst release | Park et al., 2014 | |||

| Polymer self-healing | Spontaneous pore closure (or self-healing) of PLGA microparticles at temperatures greater than the polymer glass transition temperature is used to microencapsulate biomacromolecules (proteins, peptides, and polysaccharides) in aqueous media. This approach avoids exposure to organic solvents that would otherwise occur during PLGA conventional encapsulation and uses mild processing conditions, that together minimize damage to encapsulated naked DNA, proteins, etc. | Reinhold and Schwendeman, 2013 | |||

| (4) Various additives complexing with PLGA with increased drug loading and/or sustained release profiles | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additives | Encapsulated drug | Drug loading or EE | Drug release profile | References |

| POE/PLGA | BSA | 9–11% and EE 60–90% | 95% over 30 days | Shi et al., 2003 |

| POE/PLGA | Cyclosporin A | 6–10% and EE 60–90% | 14% over 15 days followed by 78% over the next 27 days | Shi et al., 2003 |

| Alginate and chitosan-PLGA double walled | BSA | EE at 75% c.f. 65% compared with single-walled systems | 5–10% in 30 min c.f. 30% for single-walled systems | Zheng and Liang, 2010 |

| Alginate-PLGA double walled | Metoclopramide HCl | EE increase from 30% to 60% c.f. single walled system | Improved release profile | Lim et al., 2013 |

| 4% w/w chitosan/PLGA | Resveratrol | EE 40–52% Particle size: 11 to 20 μm and more stable | Improved controlled release | Sanna et al., 2015 |

| Caffeic acid grafted PLGA (g-CA-PLGA) | Ovalbumin | EE increased from 35 to 95% c.f. PLGA alone (size 15–50 μm) | Unchanged | Selmin et al., 2015 |

| Mixed copolymer of PLGA 50:50 (Mr 100,000 and 14,000) 1:7 | Pentamidine | 23.7%, whereas only 9.8 and 13.9 %, when prepared with either of them alone | Produced microcapsules with desired release profiles | Graves et al., 2004 |

| Aqueous core-PLGA shell | Risedronate sodium | 2.5-fold increase: 31.6% c.f. 12.7% for classical PLGA microspheres | Sustained release according to diffusion-controlled Higuchi model | Abulateefeh and Alkilany, 2015 |

| Porous silicon oxide (pSiO2)-PLGA | Daunorubicin | Slightly increased loading (3.1–4.6%) c.f. 2.7% for PLGA-daunorubicin microspheres | A 2-5 fold longer duration of release c.f. PLGA-daunorubicin microspheres | Nan et al., 2014 |

BSA, Bovine serum albumin; EE, Encapsulation efficiency; hGH, Human growth hormone; Mr, Molecular weight; OHR1031, a small molecule for the treatment of glaucoma; PLA, poly(lactic acid); PLGA, poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid); POE, poly(ortho esters).

Biodegradation mechanisms of PLGA-microparticles

The two main mechanisms that drive drug release from PLGA microspheres are diffusion and degradation/erosion (Kamaly et al., 2016). For PLGA (50:50) particles, drug release occurs in two phases. In the first phase, there is a rapid decrease in molecular weight (Mr) but little mass loss whereas in the second phase, the opposite occurs. This indicates that PLGA particle degradation involves heterogeneous mechanisms and that drug release is underpinned primarily by diffusion rather than polymer degradation (Engineer et al., 2010).

PLGA is a typical bulk-eroding biopolymer such that water permeates readily into the polymer matrix forming pores so that degradation takes place throughout the microspheres (Varde and Pack, 2004). Comparison of encapsulated drug release profiles from surface eroding biopolymers such as poly(ortho esters) (POE) and polyanhydrides with bulk-eroding biopolymers such as PLGA, is lacking. Hence, future research addressing this knowledge gap is needed to better inform design of microparticle formulations with the desired release profiles (Engineer et al., 2010) that may potentially include formulations comprising mixed bulk and surface-eroding biopolymers (Feng et al., 2015).

Physicochemical properties of the biopolymer

For drugs encapsulated in PLGA microparticles, the desired release rates can be achieved by adjusting the ratio of lactic acid to glycolic acid and by altering the physicochemical properties [e.g., Mr, end-group (ester or carboxylic) functionality] that influence microparticle morphology (Table 1; Mao et al., 2007; Cai et al., 2009; Gasparini et al., 2010; Nafissi-Varcheh et al., 2011). The physical properties of PLGA particles are also dependent upon the drug delivery device size, exposure to water (surface shape), as well as storage temperature and humidity (Table 1) (Houchin and Topp, 2009). These properties not only affect the ability of the biopolymer to be formulated but also influence its degradation rate (Table 1; Makadia and Siegel, 2011). Another factor that contributes to encapsulated drug release from PLGA microspheres is the concentration of polymer in the organic solvent during formulation (Wasana et al., 2009).

Choice of surfactant

During microparticle formulation using conventional solvent evaporation methods, an emulsifier is required to ensure droplet stability until the polymer concentration in the organic solvent is sufficiently high to maintain particle conformation (Chemmunique, 1980; Hwisa et al., 2013). The most widely used emulsifier in the preparation of PLGA micro/nanoparticles is poly (vinyl alcohol) (PVA) (Wang et al., 2015). It is worth noting that D-α-tocopheryl polyethylene glycol 1000 succinate (vitamin E TPGS; FDA-approved as a water-soluble vitamin E nutritional supplement) markedly improved drug loading at a concentration an order of magnitude lower (0.3 mg/ml) than analogous systems that used PVA (5 mg/ml) (Feng et al., 2007).

Methods for producing microparticles for sustained-release formulations

Drugs, including many small molecules, that are soluble in the polymer solution, can be encapsulated by simply co-dissolving with the polymer for the most commonly used methods (Table 2).

Table 2.

Methods for producing PLGA based microparticles for sustained-release formulations: Advantages and Disadvantages.

| Methods | Schematic diagrams | • Advantages | • Disadvantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

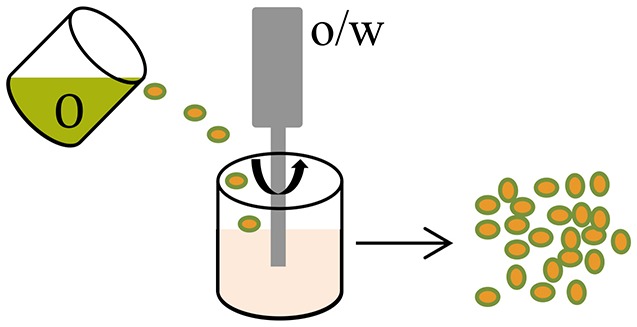

| Oil-in-water (o/w) emulsion |  |

|

|

Varde and Pack, 2004 |

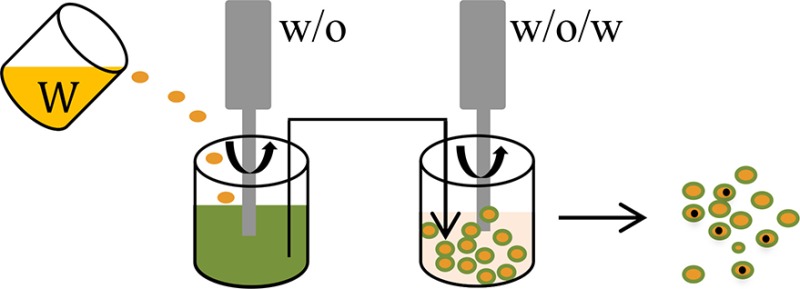

| Water-in-oil-in-water (w/o/w) emulsion |  |

|||

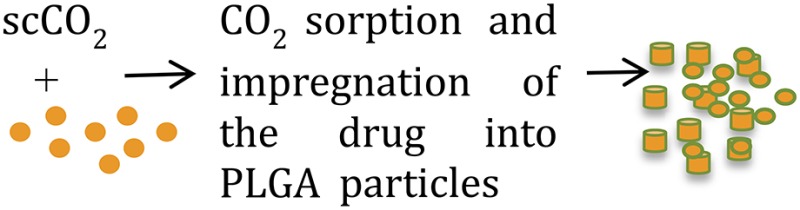

| Supercritical CO2 (scCO2) |  |

|

|

Falco et al., 2012; Dhanda et al., 2013 |

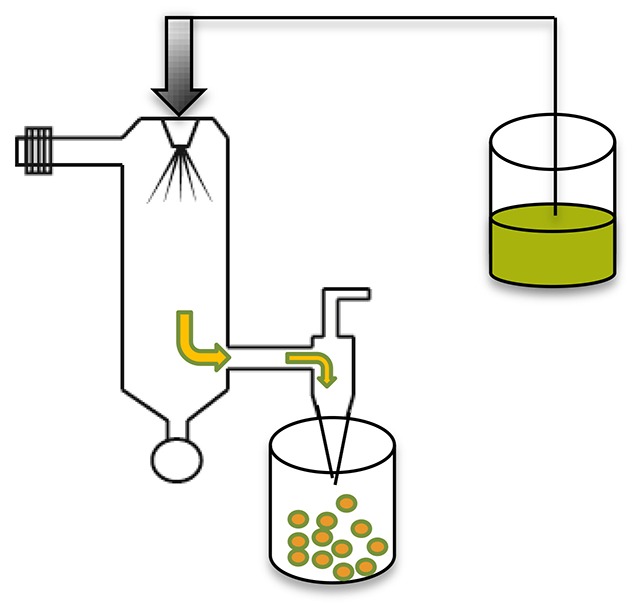

| Spray drying |  |

|

|

Makadia and Siegel, 2011; Sosnik and Seremeta, 2015; Wan and Yang, 2016 |

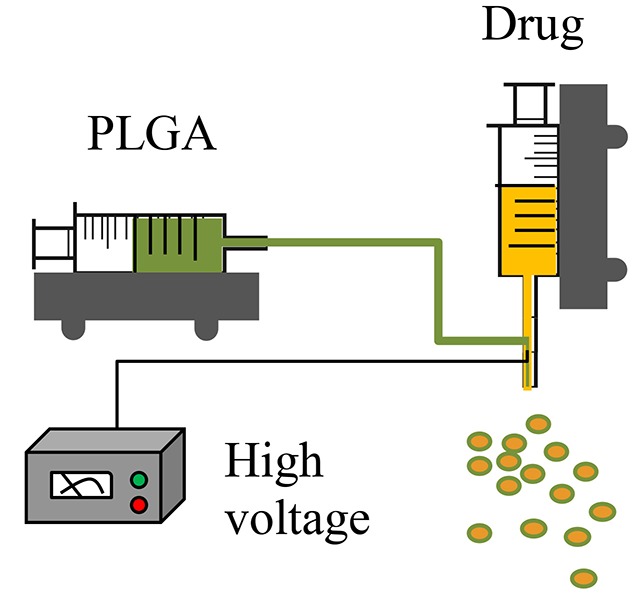

| CES (Other modification, such as, coaxial tri-capillary electrospray, Emulsion-coaxial electrospinning) |  |

|

|

Lee et al., 2011; Viry et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2012; Zamani et al., 2014; Yuan et al., 2015 |

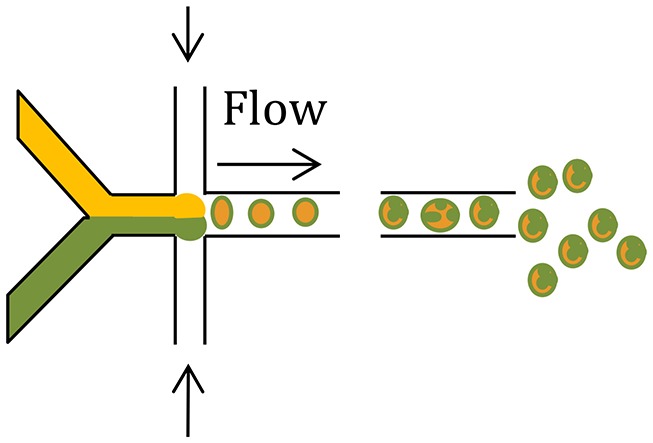

| Microfluidics (Other modification, such as, capillary microfluidics coupled with solvent evaporation) |  |

|

|

Demello, 2006; Hung et al., 2010; Xie et al., 2012; Cho and Yoo, 2015; Leon et al., 2015 |

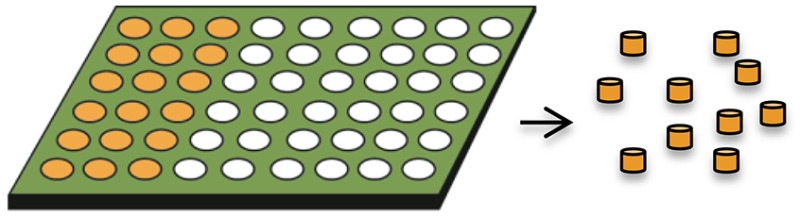

| Hydrogel template |  |

|

|

Acharya et al., 2010a,b; Malavia et al., 2015 |

CES, Coaxial electrospray; PLGA, Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid).

For the water-soluble salts of small molecule drugs, encapsulation efficiency can be improved by their conversion to a hydrophobic form, such as by complexation with ionic surfactants (Cohen et al., 1991) or to the corresponding free acid or free base form (Han et al., 2015). Alternative approaches include suspension of solid (e.g., lyophilized) particulates in the polymer solution; or use of a water-in-oil-in-water (w/o/w) solvent evaporation (double-emulsion) method. When using a w/o/w method, relatively higher drug loading and reproducible sustain-release profiles can be achieved by formulations that have a smaller volume for the inner water phase (Wasana et al., 2009; Chaudhari et al., 2010), a low preparation temperature (Yang et al., 2000; Fu et al., 2005; Chaudhari et al., 2010; Ito et al., 2011) and a suitable pH of the external phase (Bodmeier and Mcginity, 1988; Govender et al., 1999; Leo et al., 2004).

Newer technologies and approaches for achieving high levels of drug loading with suitable sustained release profiles are reviewed in the following sections and compared in Tables 1, 2.

Recent advances with promise for improving PLGA-based drug delivery systems

Hydrogel templates

Hydrogel templates enable high drug loading (~50%) and high incorporation efficiencies (~100%) to be achieved and are amenable to small molecules and biologics (Tables 1, 2) (Malavia et al., 2015). Any water insoluble material can be used as the microparticle matrix to produce the desired drug release profiles, and microparticles are recovered from the readily soluble hydrogel templates. The technology allows for precise control of the size and shape of template wells in every dimension so that microparticles with a narrow size distribution can be produced (Lu et al., 2014; Malavia et al., 2015). These attributes enable sustained-release microparticles to be produced for injection using narrow bore needles into sensitive spaces such as the eye, with nearly zero-order drug release for over 3 months with virtually no initial burst release (Malavia et al., 2015). However, more research is needed to better understand the effect of microparticle size and shape on encapsulated drug release kinetics and in vivo performance for a broad range of molecules with widely differing physicochemical properties.

Coaxial electrospray

Coaxial electrospray (CES) produces double-layered microparticles using an electric field applied to both the outer (PLGA carrier) and the inner (drug loaded) solutions sprayed simultaneously through two separate feeding channels of a coaxial needle into the one nozzle (Yuan et al., 2015). At a certain voltage threshold, a conical shape (e.g., “Taylor cone”) forms and the jets of liquids (both inner and outer flows) are broken into double-layered microparticles (Yuan et al., 2015). In the CES process, a compound Taylor cone with a core-shell structure is formed on top of the spray nozzle, and the outer polymeric solution encapsulates the inner liquid (Yuan et al., 2015). The bulk liquid is broken into small charged droplets by coulombic repulsion (Yuan et al., 2015). Using this technique, parameters such as orientation of the jets, material flow rates, and rate of solvent extraction can be controlled to create uniform and well-centered double-walled microspheres exhibiting a controllable shell thickness (Makadia and Siegel, 2011). The CES process enables effective encapsulation of proteins, drugs, and contrast agents with high efficiency, minimal loss of biological viability, and excellent control of core-shell architecture (Tables 1, 2) (Zamani et al., 2014; Yuan et al., 2015).

Microfluidic fabrication

Microfluidic devices use electrostatic forces to control the size and shape of particles for enhanced tuning of drug release characteristics (Zhang et al., 2013). Microfluidic systems have been employed for fabrication of complex drug carriers with precise size and composition leading to a predictable and tuneable release profile (Tables 1, 2) (Leon et al., 2015; Riahi et al., 2015). Two continuous and immiscible streams (i.e., oil and water) are infused via two separate inlets (Xu et al., 2009). Monodisperse droplets are generated at the junction where the two streams meet due to the high shear stress. The droplet sizes are in the range 20–100 μm (Xu et al., 2009) and 100–300 nm (Xie et al., 2012). In contrast to the classical double emulsion methods, multiple components are easily generated by a single-step emulsification in the microfluidic device (Xie et al., 2012). By introducing the second stream, droplets may be re-encapsulated which is useful for preparing core-shell structures (Nie et al., 2006).

A novel and versatile microfluidic approach for fabrication of PLGA/PCL Janus and microcapsule particles involves changing the organic solvent of the dispersed phase from dimethyl carbonate to dichloromethane (Li et al., 2015). The shell on the microcapsule particle surface is comprised of PLGA only, and the core is comprised of PCL in which tiny PLGA beads are embedded (Li et al., 2015). Interestingly, the Janus and microcapsule particles exhibited distinct degradation behaviors, implying their potential for differential effects on drug delivery and release profiles (Li et al., 2015).

Supercritical CO2

Supercritical CO2 (scCO2) provides a “green” alternative to traditional microparticle formulation techniques as it avoids use of toxic organic solvents or elevated temperatures (Tables 1, 2) (Budisa and Schulze-Makuch, 2014). Owing to the very short encapsulation process (5–10 min) at a relatively low temperature and modest pressure, and absence of organic solvents, the activity of bioactive molecules including proteins is maintained (Howdle et al., 2001; Koushik and Kompella, 2004; Della Porta et al., 2013). Because the complete process is anhydrous, it can be used to produce sustained-release formulations of multiple hydrophilic molecules (Thote and Gupta, 2005).

New variations to the use of scCO2 technology take advantage of other properties of CO2 such as its capacity to extract active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) from natural compounds or to form polymers (Champeau et al., 2015). New protocols under development hold promise for fabricating drug-eluting implants using a scCO2 impregnation process (Champeau et al., 2015).

Spray drying

Drug/protein/peptide loaded microspheres can be prepared by spraying a solid-in-oil dispersion or water-in-oil emulsion in a stream of heated air without significant losses (Makadia and Siegel, 2011). The type of drug (hydrophobic or hydrophilic) for encapsulation informs the choice and nature of the solvent to be used, whereas the temperature of the solvent evaporation step and feed rate affect microsphere morphology (Tables 1, 2) (Makadia and Siegel, 2011). Various spray drying techniques have been reported and are reviewed elsewhere (Wan and Yang, 2016).

Polymer self-healing

“Self-healing” is a phenomenon whereby polymers with damaged structures (e.g., pores, cracks, and dents), undergo spontaneous rearrangement of the polymer chains to produce healing (repair) (Syrett et al., 2010). This is important because pore closure in PLGA microparticles at physiological temperature impedes the pore-diffusion pathway and greatly reduces initial burst release of a micro-encapsulated peptide (Wang et al., 2002). Similarly, porous PLGA microspheres loaded with recombinant human growth hormone (rhGH) prepared by the solvent evaporation technique and using the surfactant pluronic F127 as porogen, underwent pore closure at the polymer surface following solvent exposure (Kim et al., 2006). These “healed” non-porous microspheres exhibited sustained drug release profiles over an extended period (Kim et al., 2006). The post-healing approach can be used to overcome shear-induced microparticle degradation, solvent-associated erosion of delicate core materials, or unexpected payload release during emulsification (Tables 1, 2) (Na et al., 2012). Strategies for “healing” pores in the microparticle surface include solvent swelling, or infrared irradiation which is potentially an even milder approach for inducing self-healing (Na et al., 2012).

Complexing PLGA with additives

As noted in an earlier section of this review, the chemical composition of PLGA-particulate drug delivery systems greatly influences their physicochemical properties, and this in turn governs the biodistribution and pharmacokinetics of the encapsulated drug (Zhang et al., 2013). Hence, complexation of PLGA with suitable additives (Table 1) including poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG), POE, chitosan and/or alginate, caffeic acid, hyaluronic acid, TPGS, and SiO2 (Shi et al., 2003; Graves et al., 2004; Zheng and Liang, 2010; Lim et al., 2013; Navaei et al., 2014; Abulateefeh and Alkilany, 2015; Sanna et al., 2015; Selmin et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015), may lead to higher drug loading and the desired sustained release profile (Shi et al., 2003; Graves et al., 2004; Zheng and Liang, 2010; Lim et al., 2013; Navaei et al., 2014; Abulateefeh and Alkilany, 2015; Sanna et al., 2015; Selmin et al., 2015).

Other strategies with promise for improving controlled-release drug delivery systems include double walled/layered PLGA (Navaei et al., 2014) and nanoparticles-in-microparticles (Lee et al., 2013). Additionally, polymer-brush PLGA-based drug delivery systems appear promising due to the versatility and controllability of the method for controlling particle shape (Huang et al., 2014).

Conclusions

In the past decade, considerable progress has been made on addressing the issues of (i) low drug loading, (ii) particle instability, and (iii) adequate control of drug release profiles for PLGA-based microparticle drug delivery systems. Strategies for increasing drug loading in PLGA-microspheres include modification of the classical solvent evaporation methods, preparation of multi-layered microparticles, and development of novel methods for microparticle fabrication including hydrogel templates, coaxial electrospray, microfluidics, and scCO2. Additionally, methods involving complexation of PLGA with additives such as PEG, POE, chitosan and/or alginate, caffeic acid, hyaluronic acid and SiO2, appear promising. Nevertheless, there is a great need for innovation in development of time-efficient methods for controlling the factors that influence drug loading and release profiles as a means to inform the design of next-generation controlled-release drug delivery systems (Draheim et al., 2015).

Author contributions

All authors listed, have made substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Funding

FH is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) grant, APP1107723.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Abulateefeh S. R., Alkilany A. M. (2015). Synthesis and characterization of PLGA shell microcapsules containing aqueous cores prepared by internal phase separation. AAPS PharmSciTech. 16. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1208/s12249-015-0413-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acharya G., Shin C. S., Mcdermott M., Mishra H., Park H., Kwon I. C., et al. (2010a). The hydrogel template method for fabrication of homogeneous nano/microparticles. J. Control Release 141, 314–319. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.09.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acharya G., Shin C. S., Vedantham K., Mcdermott M., Rish T., Hansen K., et al. (2010b). A study of drug release from homogeneous PLGA microstructures. J. Control Release 146, 201–206. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J. M., Shive M. S. (1997). Biodegradation and biocompatibility of PLA and PLGA microspheres. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 28, 5–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J. M., Shive M. S. (2012). Biodegradation and biocompatibility of PLA and PLGA microspheres. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 64, 72–82. 10.1016/S0169-409X(97)00048-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansari T., Farheen Hasnain, M. S., Hoda M. N., Nayak A. M. (2012). microencapsulation of pharmaceuticals by solvent evaporation technique: a review. Elixir Pharm. 47, 8821–8827. [Google Scholar]

- Barrow W. W. (2004). Microsphere technology for chemotherapy of mycobacterial infections. Curr. Pharm. Des. 10, 3275–3284. 10.2174/1381612043383197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxendale A., van Hooff P., Durrant L. G., Spendlove I., Howdle S. M., Woods H. M., et al. (2011). Single shot tetanus vaccine manufactured by a supercritical fluid encapsulation technology. Int. J. Pharm. 413, 147–154. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.04.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodmeier R., Mcginity J. W. (1988). Solvent selection in the preparation of poly(dl-lactide) microspheres prepared by the solvent evaporation method. Int. J. Pharmaceut. 43, 179–186. [Google Scholar]

- Budisa N., Schulze-Makuch D. (2014). Supercritical carbon dioxide and its potential as a life-sustaining solvent in a planetary environment. Life 4, 331–340. 10.3390/life4030331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai C., Mao S., Germershaus O., Schaper A., Rytting E., Chen D., et al. (2009). Influence of morphology and drug distribution on the release process of FITC-dextran-loaded microspheres prepared with different types of PLGA. J. Microencapsul. 26, 334–345. 10.1080/02652040802354707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champeau M., Thomassin J. M., Tassaing T., Jérôme C. (2015). Drug loading of polymer implants by supercritical CO2 assisted impregnation: a review. J. Control Release 209, 248–259. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhari K. R., Shah N., Patel H., Murthy R. (2010). Preparation of porous PLGA microspheres with thermoreversible gel to modulate drug release profile of water-soluble drug: bleomycin sulphate. J. Microencapsul. 27, 303–313. 10.3109/02652040903191818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemmunique (1980). The HLB System. Wilmington, DE: ICI Americas Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Cho D. I. D., Yoo H. J. (2015). Microfabrication methods for biodegradable polymeric carriers for drug delivery system applications: a review. J. Microelectromech. Sys. 24, 10–18. 10.1109/JMEMS.2014.2368071 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S., Yoshioka T., Lucarelli M., Hwang L. H., Langer R. (1991). Controlled delivery systems for proteins based on poly(lactic/glycolic acid) microspheres. Pharm. Res. 8, 713–720. 10.1023/A:1015841715384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curley J., Castillo J., Hotz J., Uezono M., Hernandez S., Lim J.-O., et al. (1996). Prolonged regional nerve blockade: Injectable biodegradable bupivacaine/polyester microspheres. Anesthesiology 84, 1401–1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danhier F., Ansorena E., Silva J. M., Coco R., Le Breton A., Préat V. (2012). PLGA-based nanoparticles: an overview of biomedical applications. J. Control Release 161, 505–522. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.01.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawes G. J. S., Fratila-Apachitei L. E., Mulia K., Apachitei I., Witkamp G. J., Duszczyk J. (2009). Size effect of PLGA spheres on drug loading efficiency and release profiles. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. M. 20, 1089–1094. 10.1007/s10856-008-3666-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Della Porta G., Falco N., Giordano E., Reverchon E. (2013). PLGA microspheres by supercritical emulsion extraction: a study on insulin release in myoblast culture. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 24, 1831–1847. 10.1080/09205063.2013.807457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demello A. J. (2006). Control and detection of chemical reactions in microfluidic systems. Nature 442, 394–402. 10.1038/nature05062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhanda D. S., Tyagi P., Mirvish S. S., Kompella U. B. (2013). Supercritical fluid technology based large porous celecoxib-PLGA microparticles do not induce pulmonary fibrosis and sustain drug delivery and efficacy for several weeks following a single dose. J. Control Release 168, 239–250. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.03.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draheim C., De Crécy F., Hansen S., Collnot E. M., Lehr C. M. (2015). A design of experiment study of nanoprecipitation and nano spray drying as processes to prepare PLGA nano- and microparticles with defined sizes and size distributions. Pharm. Res. 32, 2609–2624. 10.1007/s11095-015-1647-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunne M., Corrigan O. I., Ramtoola Z. (2000). Influence of particle size and dissolution conditions on the degradation properties of polylactide-co-glycolide particles. Biomaterials 21, 1659–1668. 10.1016/S0142-9612(00)00040-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engineer C., Parikh J., Raval A. (2010). Hydrolytic degradation behavior of 50/50 poly lactide-co-glycolide from drug eluting stents. Trends Biomater. Artif. Organs 24, 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Falco N., Reverchon E., Della Porta G. (2012). Continuous supercritical emulsions extraction: packed tower characterization and application to poly(lactic-co-glycolic Acid) plus insulin microspheres production. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 51, 8616–8623. 10.1021/ie300482n [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng S., Lu F., Wang Y., Suo J. (2015). Comparison of the degradation and release behaviors of poly(lactide-co-glycolide)-methoxypoly(ethylene glycol) microspheres prepared with single- and double-emulsion evaporation methods. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 132:41943. 10.1002/app.4194325866416 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng S.-S., Zeng W., Teng Lim Y., Zhao L., Yin Win K., Oakley R., et al. (2007). Vitamin E TPGS-emulsified poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles for cardiovascular restenosis treatment. Nanomedicine (Lond.) 2, 333–344. 10.2217/17435889.2.3.333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredenberg S., Wahlgren M., Reslow M., Axelsson A. (2011). The mechanisms of drug release in poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)-based drug delivery systems-A review. Int. J. Pharmaceut. 415, 34–52. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.05.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freiberg S., Zhu X. X. (2004). Polymer microspheres for controlled drug release. Int. J. Pharm. 282, 1–18. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas S., Merkle H. P., Gander B. (2005). Microencapsulation by solvent extraction/evaporation: reviewing the state of the art of microsphere preparation process technology. J. Control Release 102, 313–332. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu X., Ping Q., Gao Y. (2005). Effects of formulation factors on encapsulation efficiency and release behaviour in vitro of huperzine A-PLGA microspheres. J. Microencapsul. 22, 705–714. 10.1080/02652040500162196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparini G., Holdich R. G., Kosvintsev S. R. (2010). PLGA particle production for water-soluble drug encapsulation: degradation and release behaviour. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 75, 557–564. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2009.09.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govender T., Stolnik S., Garnett M. C., Illum L., Davis S. S. (1999). PLGA nanoparticles prepared by nanoprecipitation: drug loading and release studies of a water soluble drug. J. Control Release 57, 171–185. 10.1016/S0168-3659(98)00116-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves R. A., Pamujula S., Moiseyev R., Freeman T., Bostanian L. A., Mandal T. K. (2004). Effect of different ratios of high and low molecular weight PLGA blend on the characteristics of pentamidine microcapsules. Int. J. Pharmaceut. 270, 251–262. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2003.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han F. Y., Thurecht K. J., Lam A. L., Whittaker A. K., Smith M. T. (2015). Novel polymeric bioerodable microparticles for prolonged-release intrathecal delivery of analgesic agents for relief of intractable cancer-related pain. J. Pharm. Sci. 104, 2334–2344. 10.1002/jps.24497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillery A., Lloyd A., Swarbrick J. (2005). Drug Delivery and Targeting. London; New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Houchin M. L., Topp E. M. (2009). Physical properties of plga films during polymer degradation. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 114, 2848–2854. 10.1002/app.30813 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Howdle S. M., Watson M. S., Whitaker M. J., Popov V. K., Davies M. C., Mandel F. S., et al. (2001). Supercritical fluid mixing: preparation of thermally sensitive polymer composites containing bioactive materials. Chem. Commun. 2001, 109–110. 10.1039/b008188o [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Morinaga T., Tai Y., Tsujii Y., Ohno K. (2014). Immobilization of semisoft colloidal crystals formed by polymer-brush-afforded hybrid particles. Langmuir 30, 7304–7312. 10.1021/la5011488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung L. H., Teh S. Y., Jester J., Lee A. P. (2010). PLGA micro/nanosphere synthesis by droplet microfluidic solvent evaporation and extraction approaches. Lab Chip 10, 1820–1825. 10.1039/c002866e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwisa N. T., Katakam P., Chandu B. R., Adiki S. K. (2013). Solvent evaporation techniques as promising advancement in microencapsulation. VRI Biol. Med. Chem. 1, 8–22. 10.14259/bmc.v1i1.29 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ito F., Fujimori H., Kawakami H., Kanamura K., Makino K. (2011). Technique to encapsulate a low molecular weight hydrophilic drug in biodegradable polymer particles in a liquid-liquid system. Colloids Surf. A 384, 368–373. 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2011.04.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan F., Naylor A., Kelly C. A., Howdle S. M., Lewis A., Illum L. (2010). Sustained release hGH microsphere formulation produced by a novel supercritical fluid technology: in vivo studies. J. Control Release 141, 153–160. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joung Y. K., Heo J. H., Park K. M., Park K. D. (2011). Controlled release of growth factors from core-shell structured PLGA microfibers for tissue engineering. Biomater. Res. 15, 78–84. [Google Scholar]

- Kamaly N., Yameen B., Wu J., Farokhzad O. C. (2016). Degradable controlled-release polymers and polymeric nanoparticles: mechanisms of controlling drug release. Chem. Rev. 116, 2602–2663. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor D. N., Bhatia A., Kaur R., Sharma R., Kaur G., Dhawan S. (2015). PLGA: a unique polymer for drug delivery. Ther. Deliv. 6, 41–58. 10.4155/tde.14.91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. K., Chung H. J., Park T. G. (2006). Biodegradable polymeric microspheres with “open/closed” pores for sustained release of human growth hormone. J. Control Release 112, 167–174. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klose D., Siepmann F., Elkhamz K., Siepmann J. (2008). PLGA-based drug delivery systems: importance of the type of drug and device geometry. Int. J. Pharm. 354, 95–103. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.10.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klose D., Siepmann F., Elkharraz K., Krenzlin S., Siepmann J. (2006). How porosity and size affect the drug release mechanisms from PLGA-based microparticles. Int. J. Pharm. 314, 198–206. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2005.07.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koushik K., Kompella U. B. (2004). Preparation of large porous deslorelin-PLGA microparticles with reduced residual solvent and cellular uptake using a supercritical carbon dioxide process. Pharmaceut. Res. 21, 524–535. 10.1023/B:PHAM.0000019308.25479.A4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer R., Siegel R., Brown L., Leong K., Kost J., Edelman E. (1986). Controlled release: three mechanisms. Chemtech 16, 108–110. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. H., Bai M. Y., Chen D. R. (2011). Multidrug encapsulation by coaxial tri-capillary electrospray. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 82, 104–110. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2010.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. S., Johnson P. J., Robbins P. T., Bridson R. H. (2013). Production of nanoparticles-in-microparticles by a double emulsion method: a comprehensive study. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 83, 168–173. 10.1016/j.ejpb.2012.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leo E., Brina B., Forni F., Vandelli M. A. (2004). In vitro evaluation of PLA nanoparticles containing a lipophilic rug in water-soluble or insoluble form. Int. J. Pharmaceut. 278, 133–141. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon R.A.L., Somasundar A., Badruddoza A. Z. M., Khan S. A. (2015). Microfluidic fabrication of multi-drug-loaded polymeric microparticles for topical glaucoma therapy. Part. Part. Syst. Char. 32, 567–572. 10.1002/ppsc.201400229 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li W. X., Dong H., Tang G. N., Ma T., Cao X. D. (2015). Controllable microfluidic fabrication of Janus and microcapsule particles for drug delivery applications. RSC Adv. 5, 23181–23188. 10.1039/C4RA17153E [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liggins R. T., Cruz T., Min W., Liang L., Hunter W. L., Burt H. M. (2004). Intra-articular treatment of arthritis with microsphere formulations of paclitaxel: biocompatibility and efficacy determinations in rabbits. Inflamm. Res. 53, 363–372. 10.1007/s00011-004-1273-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim M. P. A., Lee W. L., Widjaja E., Loo S. C. J. (2013). One-step fabrication of core-shell structured alginate-PLGA/PLLA microparticles as a novel drug delivery system for water soluble drugs. Biomater. Sci. 1, 486–493. 10.1039/c3bm00175j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Sturek M., Park K. (2014). Microparticles produced by the hydrogel template method for sustained drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 461, 258–269. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.11.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahboubian A., Hashemein S. K., Moghadam S., Atyabi F., Dinarvand R. (2010). Preparation and in-vitro evaluation of controlled release PLGA microparticles containing triptoreline. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 9, 369–378. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makadia H. K., Siegel S. J. (2011). Poly Lactic-co-Glycolic Acid (PLGA) as biodegradable controlled drug delivery carrier. Polymers 3, 1377–1397. 10.3390/polym3031377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malavia N., Reddy L., Szinai I., Betty N., Pi J., Kanagaraj J., et al. (2015). Biodegradable sustained-release drug delivery systems fabricated using a dissolvable hydrogel template technology for the treatment of ocular indications. IOVS 56, 1296. [Google Scholar]

- Mao S., Xu J., Cai C., Germershaus O., Schaper A., Kissel T. (2007). Effect of WOW process parameters on morphology and burst release of FITC-dextran loaded PLGA microspheres. Int. J. Pharm. 334, 137–148. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.10.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na X. M., Gao F., Zhang L. Y., Su Z. G., Ma G. H. (2012). Biodegradable microcapsules prepared by self-healing of porous microspheres. ACS Macro. Lett. 1, 697–700. 10.1021/mz200222d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nafissi-Varcheh N., Luginbuehl V., Aboofazeli R., Merkle H. P. (2011). Preparing poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) microspheres containing lysozyme-zinc precipitate using a modified double emulsion method. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 10, 203–209. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nan K., Ma F., Hou H., Freeman W. R., Sailor M. J., Cheng L. (2014). Porous silicon oxide-PLGA composite microspheres for sustained ocular delivery of daunorubicin. Acta Biomater 10, 3505–3512. 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.04.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navaei A., Rasoolian M., Momeni A., Emami S., Rafienia M. (2014). Double-walled microspheres loaded with meglumine antimoniate: preparation, characterization and in vitro release study. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 40, 701–710. 10.3109/03639045.2013.777734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie Z., Li W., Seo M., Xu S., Kumacheva E. (2006). Janus and ternary particles generated by microfluidic synthesis: design, synthesis, and self-assembly. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 9408–9412. 10.1021/ja060882n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijsen J. F. W., Van Het Schip A. D., Hennink W. E., Rook D. W., Van Rijk P. P., De Klerk J. M. H. (2002). Advances in nuclear oncology: microspheres for internal radionuclide therapy of liver tumours. Curr. Med. Chem. 9, 73–82. 10.2174/0929867023371454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park K. M., Sung H., Choi S. J., Choi Y. J., Chang P.-S. (2014). Double-layered microparticles with enzyme-triggered release for the targeted delivery of water-soluble bioactive compounds to small intestine. Food Chem. 161, 53–59. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.03.125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhold S. E., Schwendeman S. P. (2013). Effect of polymer porosity on aqueous self-healing encapsulation of proteins in PLGA microspheres. Macromol. Biosci. 13, 1700–1710. 10.1002/mabi.201300323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riahi R., Tamayol A., Shaegh S. A. M., Ghaemmaghami A. M., Dokmeci M. R., et al. (2015). Microfluidics for advanced drug delivery systems. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 7, 101–112. 10.1016/j.coche.2014.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanna V., Roggio A. M., Pala N., Marceddu S., Lubinu G., Mariani A., et al. (2015). Effect of chitosan concentration on PLGA microcapsules for controlled release and stability of resveratrol. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 72, 531–536. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.08.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selmin F., Puoci F., Parisi O. I., Franzé S., Musazzi U. M., Cilurzo F. (2015). Caffeic Acid-PLGA conjugate to design protein drug delivery systems stable to irradiation. J. Funct. Biomater. 6, 1–13. 10.3390/jfb6010001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah S. S., Cha Y., Pitt C. G. (1992). Poly(glycolic acid-co-dl-lactic acid) - diffusion or degradation controlled drug delivery. J. Control Release 18, 261–270. 10.1016/0168-3659(92)90171-M21786745 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi M., Yang Y. Y., Chaw C. S., Goh S. H., Moochhala S. M., Ng S., et al. (2003). Double walled POE/PLGA microspheres: encapsulation of water-soluble and water-insoluble proteins and their release properties. J. Control Release 89, 167–177. 10.1016/S0168-3659(02)00493-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel S. J., Kahn J. B., Metzger K., Winey K. I., Werner K., Dan N. (2006). Effect of drug type on the degradation rate of PLGA matrices. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 64, 287–293. 10.1016/j.ejpb.2006.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siepmann J., Faisant N., Akiki J., Richard J., Benoit J. P. (2004). Effect of the size of biodegradable microparticles on drug release: experiment and theory. J. Control Release 96, 123–134. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosnik A., Seremeta K. P. (2015). Advantages and challenges of the spray-drying technology for the production of pure drug particles and drug-loaded polymeric carriers. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 223, 40–54. 10.1016/j.cis.2015.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syrett J. A., Becer C. R., Haddleton D. M. (2010). Self-healing and self-mendable polymers. Polymer Chem. 1, 978–987. 10.1039/c0py00104j [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thote A. J., Gupta R. B. (2005). Formation of nanoparticles of a hydrophilic drug using supercritical carbon dioxide and microencapsulation for sustained release. Nanomedicine 1, 85–90. 10.1016/j.nano.2004.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varde N. K., Pack D. W. (2004). Microspheres for controlled release drug delivery. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 4, 35–51. 10.1517/14712598.4.1.35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viry L., Moulton S. E., Romeo T., Suhr C., Mawad D., Cook M., et al. (2012). Emulsion-coaxial electrospinning: designing novel architectures for sustained release of highly soluble low molecular weight drugs. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 11347–11353. 10.1039/c2jm31069d [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wan F., Yang M. (2016). Design of PLGA-based depot delivery systems for biopharmaceuticals prepared by spray drying. Int. J. Pharm. 498, 82–95. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.12.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B. M., Wang J., Schwendeman S. P. (2002). Characterization of the initial burst release of a model peptide from poly(d,l-lactide-co-glycolide) microspheres. J. Control Release 82, 289–307. 10.1016/S0168-3659(02)00137-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Agarwal P., Zhao S., Xu R. X., Yu J., Lu X., et al. (2015). Hyaluronic acid-decorated dual responsive nanoparticles of Pluronic F127, PLGA, and chitosan for targeted co-delivery of doxorubicin and irinotecan to eliminate cancer stem-like cells. Biomaterials 72, 74–89. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.08.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasana C., Wim H., Siriporn O. (2009). Preparation and characterization of cephalexin loaded PLGA microspheres. Curr. Drug Deliv. 6, 69–75. 10.2174/156720109787048186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie H., She Z. G., Wang S., Sharma G., Smith J. W. (2012). One-step fabrication of polymeric janus nanoparticles for drug delivery. Langmuir 28, 4459–4463. 10.1021/la2042185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q. B., Hashimoto M., Dang T. T., Hoare T., Kohane D. S., Whitesides G. M., et al. (2009). Preparation of monodisperse biodegradable polymer microparticles using a microfluidic flow-focusing device for controlled drug delivery. Small 5, 1575–1581. 10.1002/smll.200801855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y. Y., Chia H.-H., Chung T.-S. (2000). Effect of preparation temperature on the characteristics and release profiles of PLGA microspheres containing protein fabricated by double-emulsion solvent extraction/evaporation method. J. Control Release 69, 81–96. 10.1016/S0168-3659(00)00291-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan S., Lei F., Liu Z., Tong Q., Si T., Xu R. X. (2015). Coaxial electrospray of curcumin-loaded microparticles for sustained drug release. PLoS ONE 10:e0132609. 10.1371/journal.pone.0132609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun-Seok R., Chun-Woong P., Patrick P. D., Heidi M. M. (2010). Sustained-release injectable drug delivery: a review of current and future systems. Pharmaceut. Tech. 2010(Suppl), 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zamani M., Prabhakaran M. P., Thian E. S., Ramakrishna S. (2014). Protein encapsulated core-shell structured particles prepared by coaxial electrospraying: investigation on material and processing variables. Int. J. Pharm. 473, 134–143. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2014.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Huang J., Si T., Xu R. X. (2012). Coaxial electrospray of microparticles and nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 9, 595–612. 10.1586/erd.12.58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Chan H. F., Leong K. W. (2013). Advanced materials and processing for drug delivery: the past and the future. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 65, 104–120. 10.1016/j.addr.2012.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng C., Liang W. (2010). A one-step modified method to reduce the burst initial release from PLGA microspheres. Drug Deliv. 17, 77–82. 10.3109/10717540903509001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng W. (2009). A water-in-oil-in-oil-in-water (W/O/O/W) method for producing drug-releasing, double-walled microspheres. Int. J. Pharmaceut. 374, 90–95. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]