Abstract

Objective

Treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) is complicated by comorbid psychiatric disorders. Successful treatment of two pediatric patients with severe OCD and comorbid attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is described.

Method

A report on two pediatric clinical cases (ages 9 and 10) with comorbid OCD and ADHD was used to describe response to medication management via the serotonin transporter inhibitor, sertraline, and the noradrenergic α2A receptor agonist, guanfacine, along with Cognitive Behavior Therapy.

Results

Cognitive behavioral therapy combined with titrated doses of the serotonin transporter inhibitor, sertraline, and the noradrenergic α2A receptor agonist, guanfacine, resolved OCD symptomology and the underlying ADHD.

Conclusion

The novel observations support a focused psychological and pharmacological approach to successful treatment of complex symptomology in patients with comorbid OCD and ADHD. Limitations to generalizability are discussed.

KEY TERMS: OCD, ADHD, CBT, Guanfacine, Pediatric

INTRODUCTION

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is a frequently comorbid condition1–6 affecting approximately 2–3% of children worldwide.7, 8 Treatment resistant OCD is often correlated with comorbidity.5, 9, 10 ADHD, which affects 8–12% of children worldwide8 and is comorbid in up to 30% of children with OCD,6 for example, can contribute to complex dysfunction beyond that noted in a sole OCD diagnosis, including additional difficulties in social functioning, school performance, self-reported depression, and family functioning.11–14 Such children also tend to have an earlier age of onset of OCD symptoms, greater symptom severity and higher persistence rate than children without comorbid ADHD.3, 8, 10, 15, 16

Differential diagnosis is complicated by both conditions commonly presenting with symptoms of inattention and impulsive behaviors.16, 17 Comorbidity between OCD and other conditions tends to affect behavioral rather than pharmacological interventions.4, 5, 18 Though the mechanism of impact of comorbid conditions on behavioral treatment strategies is not yet fully understood, it has been suggested that the difficulties with attention, concentration and impulse control inherent in ADHD for example, interfere with effective participation in exposure trials used in evidence-based behavioral interventions for OCD. Such exposure trials require active participation, ability to focus on both the trial, as well as the associated discomfort, while delaying or abstaining from blocking rituals or avoidance behaviors.16, 18 With respect to cognitive perseveration and the control of motor programs, the clinical presentations of OCD and ADHD have been considered polar opposites19 with distinct neuroanatomical substrates.20 On the other hand, like ADHD, OCD also involves an inability to inhibit inappropriate motor behavior.21

The cases presented below, describe two children with comorbid OCD and ADHD and the possible effects of ADHD symptoms (e.g. inattention, impulsivity) on OCD treatment response. Inattention and impulsiveness appeared to have negative impact on ability to identify compulsions or engage behavioral strategies aimed at blocking rituals or avoidance behaviors. This reduced the effectiveness of behavioral interventions, resulting in plateaus and incomplete OCD treatment response prior to appropriate management of ADHD symptoms. We also report that OCD-targeting cognitive behavioral therapy combined with titrated doses of the serotonin transporter inhibitor sertraline and the noradrenergic α2A receptor agonist guanfacine corresponded with remission of OCD symptomology and improvement of the underlying ADHD.

Case 1

AB, a 10-year-old Caucasian male from a middle-socioeconomic status (SES) family, who lives with his biological parents and 2 younger siblings, received 3 years of treatment for OCD with significant worsening of symptoms and increasingly negative impact on functioning. AB was born full term, despite pre-eclampsia, via vaginal delivery with vacuum. He was prescribed the dopamine D2 receptor antagonist metoclopramide when he was a few days old, for gastrointestinal reflux disease (GERD), which is currently controlled with the histamine H2 receptor antagonist ranitidine. AB met developmental milestones within typical ranges.

Family history is significant for both OCD and anxiety (mother, maternal aunt, and maternal grandfather). Thyroid disease was ruled out (AB’s mother has Hashimoto’s Disease). AB maintained “A/B” grades in 4th grade with no history of behavioral problems. AB was taking fluoxetine (20mg/20mg/40mg 3-day rotation) prescribed by an outside psychiatrist, with no improvement in OCD symptoms. He had previously experienced severe disinhibition and dangerous behaviors at a 40mg dose.

Three years of previous psychotherapy included weekly play therapy and CBT without exposure and response prevention - an empirically supported technique specific to the treatment of pediatric OCD. AB constantly needed reassurance and to “confess” daily “transgressions” due to fears he may have harmed or angered someone in innocuous situations. Obsessions affected his ability to stay on task. Comprehensive psychiatric evaluation revealed an OCD diagnosis with a current Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale score (CYBOCS) of 28 (severe range). History of tic behaviors, which did not meet diagnostic criteria for a tic disorder due to low frequency and lack of interference or distress, was also reported.

AB was 32 kg and 56 inches (10th and 25th percentiles respectively) at the start of treatment and his pediatrician denied concerns about his growth throughout treatment. The treatment plan addressed AB’s OCD symptoms with medication and weekly CBT with exposure and response prevention (OCCBT), while monitoring closely for emergence of ADHD and/or mood disorder (including self-harm). Fluoxetine was carefully discontinued while beginning sertraline 25mg, slowly titrated (Δ25mg /week) until optimal symptom reduction was noted (without negative side-effects) (Figure 1). A 12-point reduction on the CYBOCS (moderate range) was noted at sertraline 100mg/day and 4 sessions of OCCBT. Symptoms then remained stable before worsening as AB struggled with adjustment to 5th grade (week 8 of OCCBT), fueling OCD symptoms. His teacher viewed his behaviors as purposeful, disruptive, inattentive and defiant. AB began to report feelings of failure, hopelessness, and helplessness (Figure 1). An in-service which included psychoeducation, tips and accommodations for managing AB’s specific behaviors in the classroom, was well-received and implemented by school personnel. However, given a relative plateau followed by some gradual worsening in symptoms over the course of 6 weeks, AB’s sertraline dose was slowly raised.

Figure 1.

After tapering fluoxetine for 2 weeks, AB was started on sertraline (Week 1) with a resultant decrease in OCD symptoms after 5 weeks. At week 9, the psychologist met with school personnel to outline special needs for AB. The addition of extended release guanfacine further reduced the OCD severity and substantially improved attention. Left Y-axis: Drug dose is mg/day for guanfacine and (mg/day)/10 for sertraline; right Y-axis: Child Yale Brown obsessive compulsive scale. X-axis is treatment week (one CBT session per week).

At sertraline 150mg daily, AB’s family noted significant reduction in OCD symptoms, where it plateaued in the mild range. AB’s difficulty focusing while completing homework however, did not improve. There was now clear distinction between difficulty focusing due to obsessive thoughts and inattention. Comorbid ADHD became evident. Extended release guanfacine (Intuniv) 1mg per day was added to address inattention, corresponding with significant improvement in AB’s ability to concentrate on homework within one week. His OCD symptoms also reduced and positive use of OCCBT tools increased despite an unchanged sertraline dose. Academic and social functioning improved and CYBOCS scores placed him in clinical remission by week 18 where he remains to date (1 year post remission). Recommended dosing range for extended release guanfacine is 0.05–0.12 mg/kg per day, starting at 1mg/day and increasing by no more than 1mg/day per week.

Case 2

CD is a 9-year-old Caucasian male from a middle-SES family, who lives with his biological parents and two older sisters. He had experienced recent onset of OCD (previous 3 months) and intense fear of harm befalling his parents. He required his mother on site at school, calling and texting repeatedly and begging to leave school early if she was not, putting a strain on her career. CD also asked to leave social engagements early due to discomfort from OCD. CD had received 2 weeks of “mindfulness” therapy immediately prior to entering current treatment.

Prenatal history includes gestational diabetes mellitus and elevated blood pressure. Born full term without complications during labor, vaginal delivery or post-delivery, he met developmental milestones within typical ranges. CD had myringotomy surgery 3 times prior to age 6 due to chronic sinusitis. He was 32 kg and 54 inches (25th percentile) at the start of treatment and his pediatrician denied concerns about his growth throughout treatment. Comprehensive psychiatric evaluation revealed OCD (CYBOCS = 28, severe range), separation anxiety disorder and ADHD. Maternal family history was significant for bipolar disorder, depression, and alcohol abuse and possible OCD. CD was an “A” student in 4th grade with no history of behavioral problems.

CD began OCCBT and sertraline 25mg (slowly titrated for optimal symptom reduction). He also started extended release guanfacine (guanfacine-ER) 1mg, for impulsive behavior. Guanfacine-ER was raised as needed in 1mg increments (4mg maximum), on opposing weeks from sertraline dosage changes. The family history of bipolar disorder required caution when raising the sertraline dose (no more than 25mg increments, minimum of 1 week interval). Similar caution was necessary when medicating for ADHD, particularly with respect to use of stimulant medications.

CD’s treatment was complicated by impulsively performing compulsions. Significant negative social impact from impulsivity was also noted. By week 3, the family requested an increase in guanfacine-ER dose. CD’s OCD slowly responded to the combination of medication and OCCBT management, finally dropping into the moderate range after 4 weeks (sertraline 75mg; guanfacine-ER 2mg). His CYBOCS scores remained in the mild-moderate range for 6 weeks despite gradually increasing his sertraline dose up to 125mg (Figure 2).

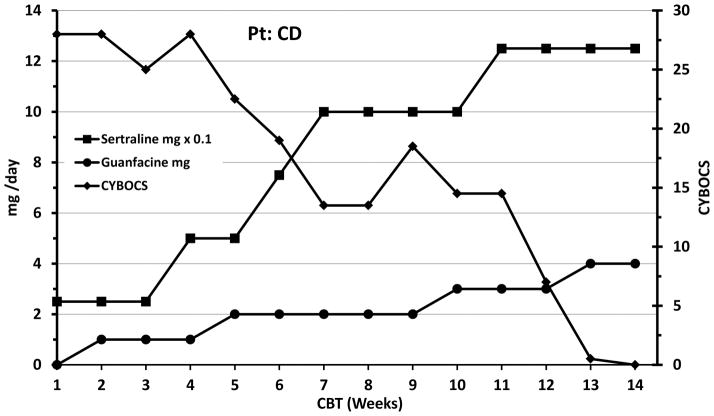

Figure 2.

Patient CD was started on sertraline (week 1) and guanfacine (week 2) with a substantial decrease in OCD symptoms after 7 weeks. Left Y-axis: Drug dose is mg/day for guanfacine and (mg/day)/10 for sertraline; right Y-axis: Child Yale Brown obsessive compulsive scale. X-axis is treatment week (one CBT session per week).

CD’s guanfacine-ER dose was slowly raised to 4 mg before the family finally noted significant improvement in impulsivity. This change corresponded with dramatic improvement in OCD symptoms and positive use of OCCBT tools as well, despite an unchanged sertraline dose. CYBOCS scores began a rapid decline into subthreshold ranges within 1 week on guanfacine-ER 4mg and sertraline 125mg, where they have remained to date (11 months post remission).

DISCUSSION

Both patients (AB and CD) were male, close in age, with early onset OCD as well as ADHD. AB’s ADHD symptoms presented primarily as inattention and were difficult to separate from his obsessions. His inattention had little impact on initial response of OCD symptoms to treatment until the CY-BOCS-PL plateaued (Figure 1). The moderate response to OCD treatment however, facilitated the distinction between inattentive behaviors caused by obsessions versus those due to ADHD. The addition of guanfacine-ER, targeting ADHD symptoms, then coincided with a further decline in OCD symptoms (Figure 1) without changing the sertraline dose or response.

CD’s ADHD symptoms were primarily poor impulse control, impeding his ability to engage in therapy and utilize therapeutic tools appropriately4–6, 18. Until CD’s ADHD symptoms were controlled by guanfacine-ER, the OCD symptoms were difficult to target with sertraline and OCCBT.

In both cases, strategically targeting ADHD symptoms in concert with pharmacological and psychological management of OCD symptoms coincided with a steady decline in OCD symptoms down to remission (Figures). Early treatment with guanfacine-ER during CBT and titration with sertraline may quicken the overall therapeutic response (compare Figure 2 and Figure 1 time course). Impulsiveness negatively impacted treatment response and fueled compulsive behavior in both children; as such, the management of impulsivity helped both children recognize compulsive urges and then engage behavioral strategies to resist the urges.

Glutamate disruption has been reported in both OCD and ADHD.22–26 Brem and colleagues27 suggest that though OCD and ADHD symptoms appear to be antipodes, their frequent comorbidity likely stems from both being the result of abnormal inhibitory processes. Although pharmacologic treatments for OCD may work by normalizing cortical glutamatergic activity, resulting in decreased attention to detail, decreased interest in planning, desire to “live in the present”, and increased dependence on exteroceptive stimulation,19 the positive resolution of OCD symptoms potentially may promote symptoms that mimic ADHD. Thus the novel medication strategy reported herein (titrated sertraline combined with non-sedative doses of guanfacine-ER), to treat comorbid OCD/ADHD avoids the non-specific, unregulated activation of multiple monoaminergic receptors attendant with stimulant pharmacotherapy. In addition to guanfacine’s direct noradrenergic effects in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex,28 guanfacine indirectly adjusts 5HT output by α2A autoreceptor mediated inhibition of locus coeruleus drive onto 5HT cells in the raphe. Consequently, in conjunction with sertraline inhibition of 5HT reuptake, the guanfacine effect on 5HT tone could yield a clinically favorable balanced 5HT tone. Finally, the favorable response to sertraline, compared to the ineffectiveness of fluoxetine (patient AB), may relate to sertraline’s inhibition of the dopamine transporter29 and a subsequent, albeit modest, clinically-significant elevation of dopamine tone stabilizing reinforcement domains by influencing glutamate effects on brain function.

Though promising, the current findings must be considered within the context of limitations inherent in two case studies. Furthermore, the demographic similarities of both cases (e.g. ethnicity, gender, age, SES), and confounds related to differing ADHD presentations between AB (primarily inattentive) and CD (primarily impulsive), multimodal interventions and additional comorbid diagnoses, may present limitations for generalizability. The use of multiple interventions (OCCBT, sertraline and guanfacine), make it difficult to determine the relative effects of each intervention on symptom change. The additional diagnosis of separation anxiety disorder in CD adds a further potential confound. Comorbid OCD with separation anxiety disorder is not uncommon, and may be related to poor treatment response and increased dysfunction.15, 30 It is neither possible to determine the effect of comorbid separation anxiety on poor initial treatment response for CD, nor the potential treatment effects of sertraline and CBT on his symptoms of separation anxiety. Similarly, it is not possible to determine the true effects of the school intervention on subsequent OCD symptom reduction in AB, although educating teachers about appropriate management of psychological symptoms in the classroom is a common and accepted practice in psychotherapy. Such limitations of comorbidity and multimodal interventions are frequently encountered by clinicians in practice and underscore the necessity and importance of subsequent design controlled clinical trials.

SUMMARY

In this case study, we suggest a rational pharmacological strategy to treat pediatric OCD with comorbid ADHD. With regularly scheduled OCD-targeting cognitive behavioral therapy, sertraline combined with guanfacine-ER led to remission of both OCD and ADHD symptoms, respectively. Effective medication treatment targeted to improve impulsivity had the greatest impact on behavioral response. Limitations due to sample size, demographics, comorbidity and multimodal interventions are discussed and design controlled clinical trials are recommended.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: This work was supported by Wayne State University and Children’s Hospital of Michigan. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), grant number NIMH 2 R01 MH059299-10A1, 1/3.

Supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health (MH059299), the Children’s Hospital of Michigan Foundation, the Prechter World Bipolar Foundation, the Lycaki-Young Fund from the State of Michigan, the Miriam Hamburger Endowed Chair of Child Psychiatry, the Paul and Anita Strauss Endowment, the Donald and Mary Kosch Foundation, The Mark M. Cohen Neuroscience Research Fund, Detroit Wayne County Health Authority and Gateway Community Health.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angst J, Gamma A, Endrass J, et al. Obsessive-compulsive syndromes and disorders: significance of comorbidity with bipolar and anxiety syndromes. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;255:65–71. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0576-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Masi G, Millepiedi S, Mucci M, et al. Comorbidity of obsessive-compulsive disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in referred children and adolescents. Compr Psychiatry. 2006;47:42–47. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Overbeek T, Schruers K, Vermetten E, et al. Comorbidity of obsessive-compulsive disorder and depression: prevalence, symptom severity, and treatment effect. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:1106–1112. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pallanti S, Grassi G, Sarrecchia ED, et al. Obsessive-compulsive disorder comorbidity: clinical assessment and therapeutic implications. Front Psychiatry. 2011;2:70. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2011.00070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geller DA, Biederman J, Faraone SV, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: fact or artifact? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:52–58. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200201000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fullana MA, Mataix-Cols D, Caspi A, et al. Obsessions and compulsions in the community: prevalence, interference, help-seeking, developmental stability, and co-occurring psychiatric conditions. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:329–336. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08071006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walitza S, Zellmann H, Irblich B, et al. Children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder and comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: preliminary results of a prospective follow-up study. J Neural Transm. 2008;115:187–190. doi: 10.1007/s00702-007-0841-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Magalhaes PV, Kapczinski NS, Kapczinski F. Correlates and impact of obsessive-compulsive comorbidity in bipolar disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2010;51:353–356. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheppard B, Chavira D, Azzam A, et al. ADHD prevalence and association with hoarding behaviors in childhood-onset OCD. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:667–674. doi: 10.1002/da.20691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sukhodolsky DG, do Rosario-Campos MC, Scahill L, et al. Adaptive, emotional, and family functioning of children with obsessive-compulsive disorder and comorbid attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1125–1132. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geller DA, Coffey B, Faraone S, et al. Does comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder impact the clinical expression of pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder? CNS Spectr. 2003;8:259–264. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900018472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geller DA. Obsessive-compulsive and spectrum disorders in children and adolescents. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2006;29:353–370. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geller DA, Biederman J, Faraone S, et al. Re-examining comorbidity of Obsessive Compulsive and Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder using an empirically derived taxonomy. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;13:83–91. doi: 10.1007/s00787-004-0379-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Mathis MA, Diniz JB, Hounie AG, et al. Trajectory in obsessive-compulsive disorder comorbidities. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23:594–601. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geller B, Zimerman B, Williams M, et al. DSM-IV mania symptoms in a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype compared to attention-deficit hyperactive and normal controls. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2002;12:11–25. doi: 10.1089/10445460252943533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Geus F, Denys DA, Sitskoorn MM, et al. Attention and cognition in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;61:45–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2007.01609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.March JS. Cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy for children and adolescents with OCD: a review and recommendations for treatment. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:7–18. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199501000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carlsson ML. On the role of cortical glutamate in obsessive-compulsive disorder and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, two phenomenologically antithetical conditions. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;102:401–413. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102006401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arnsten AF, Rubia K. Neurobiological circuits regulating attention, cognitive control, motivation, and emotion: disruptions in neurodevelopmental psychiatric disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51:356–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenberg DR, Averbach DH, O’Hearn KM, et al. Oculomotor response inhibition abnormalities in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:831–838. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830210075008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pittenger C, Bloch MH, Williams K. Glutamate abnormalities in obsessive compulsive disorder: neurobiology, pathophysiology, and treatment. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;132:314–332. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Starck G, Ljungberg M, Nilsson M, et al. A 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy study in adults with obsessive compulsive disorder: relationship between metabolite concentrations and symptom severity. J Neural Transm. 2008;115:1051–1062. doi: 10.1007/s00702-008-0045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brennan BP, Rauch SL, Jensen JE, et al. A critical review of magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodriguez CI, Kegeles LS, Levinson A, et al. In vivo effects of ketamine on glutamate-glutamine and gamma-aminobutyric acid in obsessive-compulsive disorder: Proof of concept. Psychiatry Res. 2015;233:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rubia K, Alegria AA, Brinson H. Brain abnormalities in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a review. Rev Neurol. 2014;58(Suppl 1):S3–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brem S, Grunblatt E, Drechsler R, et al. The neurobiological link between OCD and ADHD. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. 2014;6:175–202. doi: 10.1007/s12402-014-0146-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arnsten AF, Jin LE. Guanfacine for the treatment of cognitive disorders: a century of discoveries at Yale. Yale J Biol Med. 2012;85:45–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Owens MJ, Knight DL, Nemeroff CB. Second-generation SSRIs: human monoamine transporter binding profile of escitalopram and R-fluoxetine. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50:345–350. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Franz APA. Separation anxiety disorder in adult patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder: prevalence and clinical correlates. Eur psychiatry. 30:145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]