Abstract

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) is a common circulatory disorder of the lower limb arteries that reduces functional capacity and quality of life of patients. Despite relatively effective available treatments, PAD is a serious public health issue associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) cycles during PAD are responsible for insufficient oxygen supply, mitochondriopathy, free radical production, and inflammation and lead to events that contribute to myocyte death and remote organ failure. However, the chronology of mitochondrial and cellular events during the ischemic period and at the moment of reperfusion in skeletal muscle fibers has been poorly reviewed. Thus, after a review of the basal myocyte state and normal mitochondrial biology, we discuss the physiopathology of ischemia and reperfusion at the mitochondrial and cellular levels. First we describe the chronology of the deleterious biochemical and mitochondrial mechanisms activated by I/R. Then we discuss skeletal muscle I/R injury in the muscle environment, mitochondrial dynamics, and inflammation. A better understanding of the chronology of the events underlying I/R will allow us to identify key factors in the development of this pathology and point to suitable new therapies. Emerging data on mitochondrial dynamics should help identify new molecular and therapeutic targets and develop protective strategies against PAD.

Keywords: peripheral artery disease, ischemia-reperfusion, skeletal muscle, mitochondria, oxidative stress

peripheral artery disease (PAD) refers to a common circulatory disorder of the lower limb caused by chronic narrowing of the arteries (e.g., stenosis and occlusion) or atherosclerosis. PAD represents a broad spectrum of disease severity, ranging from asymptomatic disease to frequent pain when walking (i.e., intermittent claudication or limping) or critical limb ischemia associated with decubitus pain and/or ulcers (114, 126).

PAD is known to be associated with reduced functional capacity and quality of life. It is a major cause of limb amputation, as well as an increased risk factor for myocardial infarction, stroke, and death. The incidence of PAD varies with age, from 3–10% in young people to 15–20% in people >70 yr of age, and is asymptomatic in 40% of the cases (1), with greater prevalence among men. The major PAD risk factors, including smoking, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and obesity, are the same as those for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases (35).

Three main complementary treatment options improve the functional status and other clinical outcomes in PAD patients (54). 1) Optimization of medical therapy (i.e., pharmacotherapy) reduces the risk of cardiac ischemia, increases the distance a patient can walk, and improves the functional capacity of patients. 2) When possible, exercise training, a noninvasive and nonpharmacological therapy, improves walking ability and has protective effects in patients with PAD characterized by intermittent claudication and infrainguinal lesions (67). 3) Complementing treatment options 1 and 2, revascularization (either endovascular or open) prevents limb pain at rest and limb loss in patients with intermittent claudication who continue to have symptoms impacting their quality of life or in patients with critical limb ischemia.

However, despite relatively effective available treatments (14), PAD remains a serious public health issue associated with significant morbidity and mortality. A better understanding of physiopathology should lead to improved therapies.

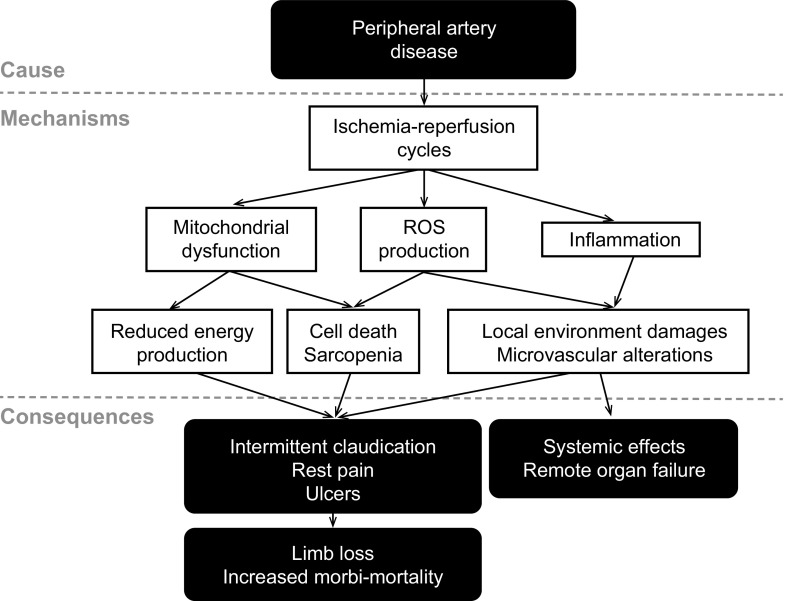

The reduction or cessation of blood circulation followed by reperfusion [i.e., ischemia-reperfusion (I/R)] is the cause of local and distant alterations. I/R during PAD results in insufficient oxygen supply secondary to reduced blood flow, mitochondriopathy leading to reduced energy supply, oxidative stress (i.e., imbalance between free radical production and elimination), and inflammation, which lead to intermittent claudication, limb pain at rest, ulcers, and, potentially, limb loss and increased morbidity/mortality (13, 39, 71, 95, 114, 162) (Fig. 1). Depending on the mass of ischemic muscle and the duration of ischemia, these mechanisms can trigger remote complications in organs such as the kidney, liver, heart, and lung and lead to death (47, 200). A hypothesis explaining the failure of these remote organs is that liberation of toxic metabolites into the blood contributes to systemic inflammation (13, 47, 63). However, PAD occurs in parallel with comorbidity factors such as aging, diabetes, and hypertension, which share common etiology and are also at the origin of several pathological states and likely modulate local and remote effects of I/R (33, 35). Thus, in conjunction with comorbidity factors, local and distant sequential events that occur in skeletal muscle fibers during ischemia and reperfusion progressively (and irreversibly) impair muscle tissue to trigger death.

Fig. 1.

Pathogenesis of peripheral artery disease. Peripheral artery disease triggers hindlimb ischemia-reperfusion cycles that, in interactions with comorbidity factors and via several mechanisms, including mitochondrial dysfunction, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and inflammation, lead to both local and remote organ impairments. [Modified from Lejay et al. (97).]

Several experimental models have been developed to investigate PAD. Acute models have limitations, since skeletal muscle is subjected to a single episode of ischemia followed by a single period of reperfusion. This might be only partially relevant in the case of PAD, which leads to chronicity because of recurrent episodes of ischemia and reperfusion (91, 101). Thus recent experimental models of chronic PAD have been proposed to be more relevant to clinical PAD (91, 96). Interestingly, we observed that the mechanisms involved in chronic lower limb I/R that best reflect human pathology are very similar to those observed in acute models (96) and human physiopathology (149). The use of such experimental models, therefore, remains relevant and indispensable to understand the mechanisms underlying I/R and tissue damage leading to PAD and to develop new therapeutic strategies. One of these strategies is ischemic conditioning, which corresponds to several brief I/R episodes before (i.e., preconditioning), during (i.e., perconditioning), or after (i.e., postconditioning) prolonged ischemia. Ischemic preconditioning is frequently used in acute experimental models and appears to be protective (88, 135, 176). Importantly, the report of Mansour et al. (108) that remote and local ischemic preconditioning equivalently protect skeletal muscle mitochondrial function during lower limb I/R opens therapeutic avenues, since remote (at a distant organ, not suffering from ischemia) ischemic preconditioning is easier to accomplish than local preconditioning. In the context of chronic PAD, ischemic conditioning, a natural phenomenon that occurs during walking, must be considered a part of PAD physiopathology. This reinforces the need to develop chronic experimental models better mimicking the human physiopathology of PAD.

The chronology of these I/R events is poorly described in the literature. In this context, after a review of the basal state of skeletal muscle cells and mitochondrial function, our purpose is to review the physiopathology of I/R at the level of the myocyte. We will focus on cellular and mitochondrial impairments during ischemia and reperfusion in skeletal muscle and on associated events (inflammation and morphological and microvascular changes) in surrounding tissues, finally leading to cell death.

BASIC KNOWLEDGE OF MYOCYTES: IMPORTANCE OF MITOCHONDRIA

Skeletal muscle is composed of excitable cells that have been studied at rest and during contractile activity. At rest, myocyte membrane potential ranges from −60 to −90 mV, and intracellular pH is ∼7. The pH decreases during contractile activity (37, 64, 158).

Ca2+ plays a central role as the main regulatory and signaling molecule in muscle physiology. Indeed, expression of several genes, as well as muscular contraction and relaxation, is a phenomenon controlled by Ca2+. Free cytosolic Ca2+ concentration in the resting skeletal muscle cell is maintained at ∼50 nM but can reach ∼100-fold higher levels during contraction (12). Intracellular Ca2+ concentrations depend on the fiber type: they are more elevated in red slow-twitch (type I) fibers (oxidative metabolism) than in white fast-twitch (type II) fibers (glycolytic metabolism) (87, 105). Cellular Ca2+ dynamics that accompany the action potentials are characterized by specific kinetics according to the fiber phenotype: lower amplitude and longer duration in oxidative fibers and higher amplitude and shorter duration in glycolytic fibers (9, 10, 23, 141). These specific kinetics are related to sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) isoforms of Ca2+-ATPase and ryanodine receptors and to their density (156). This difference is also observed in mitochondria of these various fiber types (140).

Mitochondria are essential organelles found in nearly all eukaryotic cells. They participate in many physiological functions, such as cell differentiation, energy metabolism, Ca2+ signaling, and apoptosis (53, 175). Their density and localization vary according to cell type. In skeletal muscle, their number depends on the fiber type: they are more numerous in oxidative fibers (141). Mitochondria occupy a small myocyte volume. In humans, mitochondrial volume is ∼6%, ∼4.5%, and ∼2.3% in type I, IIA, and IIX fibers, respectively (165). In rats, mitochondrial volume is ∼2.2% and ∼10% in white gastrocnemius (predominantly glycolytic) and soleus (predominantly oxidative) muscles, respectively (165). Mitochondria are located around nuclei or between bundles of myofilaments (20, 190). This location allows mitochondria to communicate with one another via a complex network (100) and to participate in physiological functions by regulated fission and fusion mechanisms, termed “mitochondrial dynamics.” Although little is known about mitochondrial dynamics in skeletal muscle, mitochondrial dynamics have been implicated in mitochondrial DNA renewal, cell differentiation and development, mitochondrial respiration, and bioenergetics (46, 100, 120, 129, 142).

Mitochondria, the “Powerhouse” of the Cells

Skeletal muscle is highly energy-dependent: 95% of the energy stores contribute to mitochondrial metabolic activity (192). This energy is provided by ATP molecules, for which storage is limited (∼35–55 μmol/mg protein) (2, 64, 66).

In the resting myocyte, ATP is mainly produced in mitochondria by the oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) process, after transformation of free fatty acids or glucose by β-oxidation, glycolysis, and the tricarboxylic acid (Krebs) cycle (192), and lactate production from metabolism is low. However, according to the fiber type and, thus, the metabolic pathway, muscle tissues have developed a specific adaptation in terms of respiratory control and energy distribution, depending on their needs. The mitochondrial oxidative capacity of glycolytic muscles is greater than that of oxidative muscles with glycerol-3-phosphate, a substrate of glycolysis. Conversely, the mitochondrial oxidative capacity of oxidative muscles is greater than that of glycolytic muscles with palmitoylcarnitine, a substrate of β-oxidation (141, 150).

Under normal circumstances, mitochondria are the most important source of ATP. Skeletal muscle can increase its ATP turnover, allowing it to transition from rest to exercise/contractile activity, where different energy-producing substrates (high-energy phosphate compounds, glucose, glycogen, and lipids) can be oxidized (49, 66, 84, 135). The most concentrated substrates in skeletal muscle are glycogen and phosphocreatine (PCr) (192), with higher PCr levels in glycolytic muscles (26). Some authors have demonstrated that ATP content remains stable during contraction (49, 84), while others have found that it decreases (72, 106); this discrepancy may be explained by the use of different species and contraction protocols. However, all agree that there is a shift in metabolites used to synthesize ATP, with a decrease in glycogen (increase in glycolysis) and PCr [increase in creatine kinase (CK) reactions] and an accumulation of lactate in myocytes.

Energy-consuming processes are essentially localized in myofibrillar compartments, the sarcolemma, and the SR, whereas energy is produced within mitochondria or glycolytic complexes. Because of the restricted diffusion of adenine nucleotides near the ATPases of myofilaments and SR, there are local systems for rephosphorylating ADP. The CK system is localized near or within these different compartments and efficiently controls local adenylate pools, linking energy production and utilization (185). CK isoenzymes catalyze the reversible transfer of a phosphate moiety between creatine and ATP. The mitochondrial CK isoenzyme, bound to the outer surface of the inner mitochondrial membrane, generates ATP by OXPHOS and transphosphorylated PCr (85). In addition, the cytosolic CK isoenzyme, which is structurally associated with myofibrils and SR membranes, can use PCr to rephosphorylate ADP and, thus, provide enough energy for normal contractile kinetics or SR Ca2+ uptake (160, 185).

Mitochondria, an Important Source of Reactive Oxygen Species

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species are free radicals produced in myocytes, endothelium, and extracellular space from peroxisomes, SR, PLA2, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidases, xanthine oxidases (XO), and nitric oxide (NO) synthases (111, 139). However, mitochondria of skeletal muscle cells are the predominant source of ROS (139). They are mainly produced by complexes I and III of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Some research groups have shown higher ROS concentrations in mitochondria from glycolytic muscles (3, 141), whereas others have observed higher ROS concentrations in oxidative muscles (15, 115). The primary reactive species produced in myocytes are superoxide anion (O2·−) and NO, which lead to formation of several secondary reactive species, such as H2O2, hydroxyl radical (HȮ), and peroxynitrite (7).

Low cellular production of free radicals is involved in physiological signaling and regulatory functions (7, 153). As second messengers, they modulate changes in cell and tissue homeostasis and gene expression. They are rapidly eliminated by enzymatic and nonenzymatic antioxidant systems, such as catalase, superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), glutathione, thioredoxin reductase, coenzyme Q, and vitamin E, in myocytes, endothelium, and extracellular space (7, 77). Nevertheless, the activity of antioxidant enzymes, particularly GPx, is significantly lower in glycolytic than oxidative muscles (141).

Myocytes respond to contractile activity by an increase in intra- and extracellular production of free radicals (77). Indeed, in different contraction protocols, an increase in reactive species production, particularly HȮ and H2O2, has been observed (128, 134, 188). In parallel, myocyte antioxidant defenses are modified after contractile activity or exercise. Some researchers have found an increase in enzymatic antioxidant systems, such as SOD and catalase (82, 113), while others have demonstrated that muscle contractile activity decreases glutathione and thiol protein contents, two nonenzymatic antioxidant systems (188).

Thus mitochondria play a key role in skeletal muscle fiber physiology at rest and during contractile activity. They are essential 1) in energetic metabolism, supplying necessary energy, and 2) in cell signaling, mediating adaptive and protective processes through Ca2+ and low ROS production.

PHYSIOPATHOLOGY OF I/R IN SKELETAL MUSCLE

Lower limb ischemia resulting from PAD complications is defined as oxygen and nutrient deprivation following reduced blood flow, leading to cell impairment. Reperfusion allows blood to recirculate in ischemic tissues but is paradoxically associated with further damage. I/R of the lower limb impairs the entire local muscle environment (endothelial and muscle cells, vessels, and nerves) via complex processes, leading to loss of muscle function and failure of remote organs.

In contrast to the myocardium, where lesions are generally irreversible after 20–40 min of ischemia (80, 157), skeletal muscle seems relatively tolerant to ischemia, with the degree of injury directly related to the severity and duration of ischemia (138). In rats, Belkin et al. (11) showed that the first muscle injuries appear at 3 h of ischemia, while severe injury appears at 4–6 h. Martou et al. (110) reported that 3–4 h of hypoxia followed by 2 h of normoxia is needed to significantly alter human skeletal muscle. Other parameters, such as temperature, presence or absence of collateral flow, and fiber type, influence the tolerance of skeletal muscle for ischemia (138, 193, 198). In mice, the vastus muscle (predominantly glycolytic) is more vulnerable to ischemia than the soleus muscle (predominantly oxidative) (25). This difference in vulnerability has also been observed between the gastrocnemius (predominantly glycolytic) and soleus (predominantly oxidative) muscles in rats (193). We have proposed that reduced antioxidant capacity in the gastrocnemius might explain the greater sensitivity to ischemia (27, 50).

Regardless of fiber type, I/R induces locally histomorphological and biochemical changes in myocytes that lead to cell death and systemic injuries. PAD-induced I/R leads to important myopathic (necrosis, phagocytosis, central nuclei, and fibrosis) and neuropathic (myofibrillar denervation) changes (147). It also modifies the cellular organelle structure, particularly mitochondria, leading to functional alterations and oxidative damage (145, 146).

Chronology of Events at the Level of Skeletal Muscle Fiber

Cellular and mitochondrial events during ischemia.

ADENOSINE TRIPHOSPHATE DEPLETION, INTRACELLULAR PH DECREASE, AND CYTOSOLIC CALCIUM OVERLOAD.

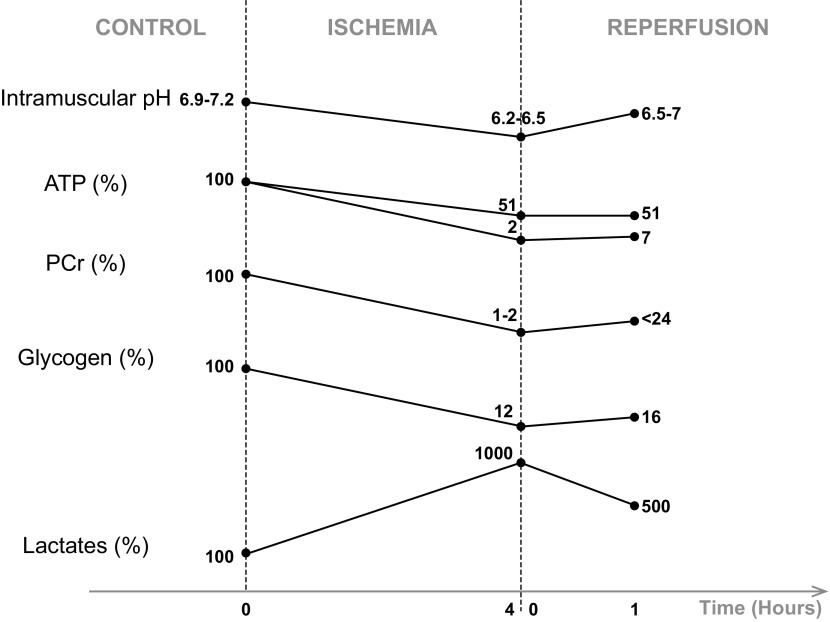

During ischemia, the nutrient- and oxygen-deprived blood supply cannot meet the energy demands of muscles, leading to numerous ionic and metabolic changes. The low ATP reserve is used predominantly to maintain membrane potential and ion compartmentalization, but because of oxygen deprivation, mitochondrial OXPHOS and the electron transport chain are inhibited, and the mitochondrial membrane potential decreases (26, 102). Brandão et al. (17) showed in isolated rat mitochondria that respiration and membrane potential are altered after 5 h of ischemia. More specifically, mitochondrial activity of complexes I, II, and IV is altered during prolonged ischemia (176, 177). This leads to a fall in ATP synthesis and a rise in inorganic phosphate (Pi) and adenine nucleotide concentrations (135, 192). After 2–3 h of ischemia, ADP is catabolized into hypoxanthine and xanthine (18, 135), substrates that will contribute to ROS production during reperfusion. Chouchani et al. (30) demonstrated in the heart that succinate is another universal metabolite produced during ischemia by reversal of succinate dehydrogenase, which accumulates in cells and contributes to deleterious effects at the moment of reperfusion. To continue to produce ATP, anaerobic metabolism and PCr pathways are activated. In skeletal muscle, ATP falls at a very low rate during the first 3 h, when PCr and glycogen reserves are large. After 3 h of ischemia, the ATP store declines rapidly until 6–7 h, when exhaustive depletions of ATP, PCr, and glycogen occur (correlated with almost complete skeletal muscle death) (Fig. 2) (92, 123, 181, 183, 192). These changes in metabolism lead to accumulation of NAD, lactate, and H+, acidifying the intra- and extracellular environments (Fig. 2) (47, 64, 109, 195) and inhibiting glycolysis (66, 154). Harris et al. (70) showed that lactate production is continuous during skeletal muscle ischemia (up to 6 h) (70). This accumulation was observed after 4 h of anoxia by Vezzoli et al. (191). Noll et al. (125) showed local lactate accumulation after 2 h of ischemia in mice. Na+/H+ exchangers are activated to restore pH. Different ionic exchangers of the sarcolemma (Na+-K+-ATPases and Ca2+-ATPases) are inhibited by the low ATP concentration, inducing an increase in cytosolic Na+. The mechanism of Na+-Ca2+ antiporters is reversed in an attempt to restore the cytosolic Na+ concentration, which leads to the accumulation of cytosolic Ca2+ (47, 74). In addition, SR Ca2+-ATPases are impaired, while Ca2+ continues to be extruded from the SR to the cytosol (83, 177). This Ca2+ accumulation can cause irreversible damage to cell integrity by degrading cellular enzymes such as phospholipases, lysozymes, proteases, and nucleases, contributing to inflammation and cell death by necrosis and apoptosis (38, 63, 178).

Fig. 2.

Expected changes in pH, adenosine triphosphate (ATP), phosphocreatine (PCr), glycogen, and lactate after 4 h of ischemia and 1 h of reperfusion of the lower limb in rats. These selected data were obtained from the literature, based on their consistency. Intramuscular pH (103, 104, 180) and concentrations of ATP (93, 103, 104, 183, 184), PCr (93, 183, 184), and glycogen (183, 184) decrease during ischemia and increase after reperfusion. Intramuscular lactate concentration increases during ischemia and decreases after reperfusion (183, 184). Such changes can vary according to species, muscle phenotypes, ischemia-reperfusion protocols, and measurement instruments, but trends seem to be similar regardless of the context. Values are expressed as percentages compared with control.

REACTIVE OXYGEN SPECIES PRODUCTION.

In parallel, ischemia participates in production of ROS, mainly O2·− and H2O2 (5, 159, 168). Few studies have examined the effects of ischemia alone in skeletal muscle by measuring either ROS production directly or oxidative stress products. Guillot et al. (61) showed biphasic ROS production: during ischemia and during reperfusion. Kocman et al. (88) demonstrated an increase in malondialdehyde, an oxidative stress marker, after ischemia. During ischemia, xanthine dehydrogenase, which is found in the microvascular endothelial cells of skeletal muscle, is converted to XO (189), which, in turn, catalyzes the conversion of hypoxanthine to xanthine by producing O2·−. Thus the primary sources of ROS during ischemia seem to be XO and mitochondrial complexes I and III (8, 154, 184). Skeletal muscle contains 10–15% of the body's iron stores, mainly in mitochondria and myoglobin (7). The progressive reduction of proteins with an iron-sulfur cluster during prolonged ischemia releases iron ions, which participate in ROS production by the Fenton reaction at the moment of reperfusion. All these free radicals contribute to membrane injury and permeabilization, nonfunctional protein formation, and DNA mutations (139).

A decrease in nonenzymatic antioxidants during ischemia makes cells more vulnerable to oxidative stress (204). However, to our knowledge, no data concerning the enzymatic antioxidant systems in skeletal muscle are available. In other organs such as the heart, kidney, and brain, enzymatic and nonenzymatic antioxidant activities are significantly decreased during ischemia (42, 69, 78).

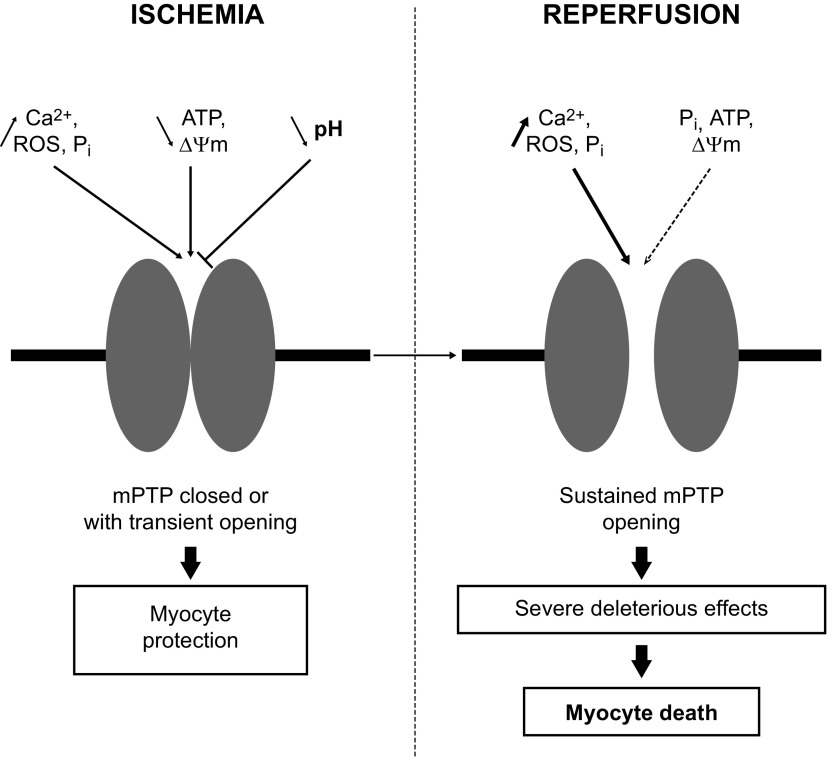

MITOCHONDRIAL PERMEABILITY TRANSITION PORE FORMATION.

The mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) is a nonselective multiprotein channel located in the inner mitochondrial membrane that is permeable to ≤1.5-kDa solutes. It plays an important role in I/R-induced damage and is well studied in the heart, but not in skeletal muscle. The exact composition of the mPTP remains uncertain, although several proteins seem to be involved in its formation and regulation (adenine nucleotide translocase, phosphate carrier, F0F1-ATP synthase, cyclophilin D, voltage-dependent anion channel, translocator protein, hexokinase II, Bcl-2 family members, glycogen synthase kinase-3β, and PKCε) (65, 122, 130).

The mPTP is regulated by various cell factors, such as ROS, Ca2+, ATP, and Pi concentrations, pH, and membrane potential (121). Griffiths and Halestrap (58) showed that mPTP remains closed during cardiac ischemia. After the biochemical changes that occur during ischemia (increase in ROS, Ca2+, and Pi levels and decrease in ATP content and membrane potential), the mPTP was primed but remained closed because of the low intracellular pH. More recently, Seidlmayer et al. (168) demonstrated that cardiac ischemia is associated with transient mPTP opening to protect cells from Ca2+ accumulation and ROS production (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Cell factors that regulate mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) opening during ischemia-reperfusion: Ca2+ concentration, reactive oxygen species (ROS), inorganic phosphate (Pi), adenosine triphosphate (ATP), pH, and membrane potential (ΔΨm).

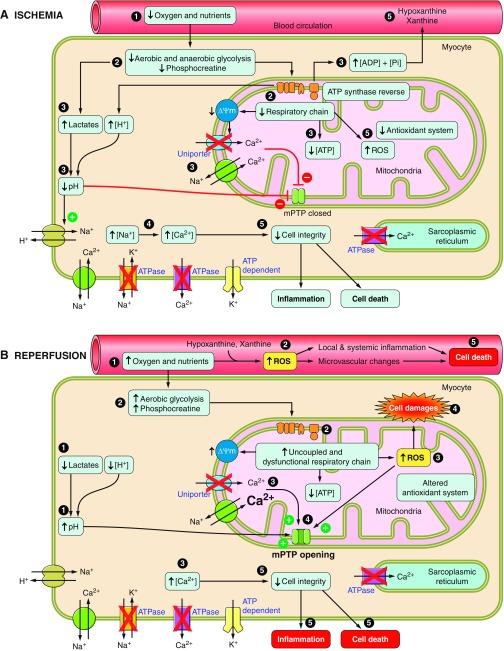

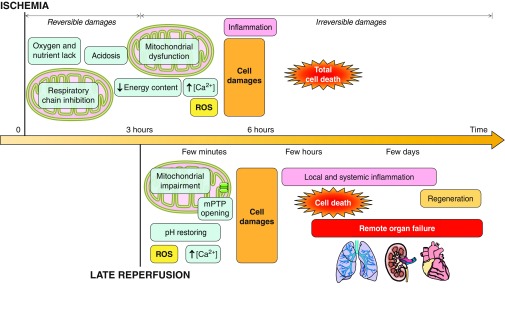

In summary, skeletal muscle ischemia is associated with a number of deleterious consequences, which are shown chronologically in Fig. 4A. There is a gradual depletion of intracellular energy stores together with an accumulation of products from glycolysis: H+ and Ca2+. Mitochondria are particularly affected; there are changes in OXPHOS and ROS generation. Cell damage is likely irreversible after ∼4 h of ischemia. Because 7 h of ischemia causes the death of almost all the muscle tissue, reperfusion is necessary and should be initiated promptly to preserve skeletal muscle.

Fig. 4.

Chronological events during ischemia-reperfusion in myocytes. A: ischemia decreases energy content, acidifies intra- and extracellular environments, and alters mitochondria. Ca2+ accumulation and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production impair cell integrity. B: reperfusion restores pH, produces more ROS, and induces Ca2+ uptake, triggering inflammation, mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) opening, and cell death. ADP, adenosine diphosphate; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; Pi, inorganic phosphate; ΔΨm, membrane potential.

Cellular and mitochondrial events during reperfusion.

Reperfusion, which is necessary to stop ischemic injury, is an additional source of cell damage, termed “reperfusion injury.” Jennings et al. (80, 81) were the first to show the deleterious effects of reperfusion on the myocardium. In skeletal muscle, as in other organs, reperfusion injury can be fatal, damaging cells and organelles such as mitochondria by different mechanisms (83).

OXYGEN PARADOX.

A high oxygen supply at the beginning of reperfusion is the primary cause of reperfusion injury and myocyte death by generation of excessive quantities of ROS. At the cell surface, hypoxanthine produced during ischemia is converted to uric acid by XO in the presence of oxygen molecules (133), producing O2·− and H2O2 and participating in local and systemic inflammatory processes in vascular cells.

Therefore, contrary to hindlimb ischemia, with few sources of ROS, several potential sources are activated at the moment of reperfusion and generate a massive burst of free radicals with a greater variety of reactive molecules (mainly O2·−, H2O2, HȮ, NO, and peroxynitrite) (63, 83, 184). This was the case in the extracellular environment and endothelial and muscle cells (47, 192). At the onset of reperfusion, mitochondria damaged during ischemia are no longer able to function efficiently. Complex I is reversed following the accumulation of succinate during ischemia (30), and mitochondrial complexes I and III are impaired and produce O2·−. It is known that mitochondrial ROS production is a self-amplified process, termed “ROS-induced ROS release.” The possible mechanisms described in the literature are 1) a mitochondrial membrane depolarization that triggers mPTP opening and 2) opening of a mitochondrial inner membrane anion channel (57, 205). Other potential important sources of free radical generation at reperfusion include NADPH oxidases, NO synthases, and XO (8, 57, 83, 86, 98). However, even if some reports suggest that mitochondria could not be a predominant source of ROS (76), activation of these processes seems to require an initial burst of mitochondrial ROS and contributes to secondary tissue damage and inflammation (31).

The possibility that these different sources do not produce ROS separately but, rather, together comes to light. Indeed, ROS produced by one enzymatic source could activate another source and enhance ROS production (57). Interactions between NADPH oxidases and mitochondria or between NO synthases and XO have been reported, but not in skeletal muscle (34, 36, 40, 43, 155).

This burst of ROS cannot be eliminated, because the antioxidant defenses (at least nonenzymatic) are also altered by ischemia. Indeed, excessive ROS production and a decrease in antioxidant systems, such as glutathione, GPx, SOD, and catalases, after reperfusion have been demonstrated (28, 61, 107, 151, 174, 178, 179). Decreases in SOD2, catalases, and GPx have been verified in patients with PAD (146, 148).

Oxidative stress induces nonspecific changes in lipids via lipoperoxidation, proteins via nitration and oxidation, and DNA via base and sugar mutations (139). All these modifications are responsible for protein, enzyme, and receptor dysfunctions, membrane rigidity and permeabilization, and cell death (48, 59, 62, 192). For example, ROS may directly release mitochondrial endonuclease G or apoptosis-inducing factor, two proteins that promote DNA fragmentation and apoptosis in skeletal muscle (45). Also, cardiolipin oxidation may impair mitochondrial complex activities, release cytochrome c, and be responsible for apoptosis and mPTP opening (97, 172).

CALCIUM PARADOX.

With reoxygenation, the respiratory chain of undamaged mitochondria produces ATP and the mitochondrial membrane potential is recovered. However, in cells subjected to ischemia, reperfusion further alters the activity of mitochondrial complexes I–IV as described in experimental models and PAD (28, 108, 146, 147, 176, 179). The impaired function decreases ATP synthesis (Fig. 2) (2, 92, 135, 181) and produces excessive ROS, which affects the membrane channel, including ATP-dependent and -independent exchangers, and further increases cytosolic Ca2+ concentration (18, 87, 184). To attempt to reduce this Ca2+ accumulation, mitochondria take up Ca2+ via the membrane potential-dependent Ca2+ uniporter (112). However, the elevated cytosolic Ca2+ concentration activates phospholipases and proteases and interacts with other cell compounds. Membrane receptors, enzymes, and ion channels are affected, leading to cell membrane degradation, decreased cell viability, and cell death (55, 194).

PH PARADOX.

Osmotically active molecules accumulate in the extracellular environment during ischemia and are eliminated by blood recirculation, generating an osmotic gradient between the extra- and intracellular environments (Fig. 2). This leads to water uptake, swelling, and breakup of cells (192). Lactate, H+, and precursors of adenine nucleotide metabolism are also washed out (66, 133, 135). Extra- and intracellular pH are rapidly restored via activation of several exchangers at the beginning of reperfusion (37, 118), inducing lethal cell injury through mPTP opening (168). Indeed, this rapid regularization of acidosis plays an essential role in reperfusion injury. Maintaining a low intracellular pH at the onset of reperfusion delays mPTP opening and is cardioprotective (32, 73).

MITOCHONDRIAL PERMEABILITY TRANSITION PORE OPENING.

Opening of the mPTP at the onset of reperfusion occurs due to ROS, pH, Ca2+, ATP, and membrane potential (Fig. 3). This opening leads to mitochondrial OXPHOS uncoupling, resulting in further ATP depletion, membrane potential depolarization, and water entry into the mitochondrial matrix. The mitochondrial swelling permeabilizes and ruptures the mitochondrial membranes and leads to cell death. Apoptosis is related to the release of proapoptotic factors (cytochrome c and apoptosis-inducing factor) from the mitochondrial intermembrane space and activation of the caspase cascade. Necrosis results from the activation of proteases, caspases, and phospholipases and inflammation (122, 178). Specific inhibition of mPTP opening by cyclosporine A in skeletal muscle partly protects mitochondrial functions and limits deleterious effects of reperfusion, demonstrating the essential role of mPTP in I/R injury (151). However, cyclosporine A protection is lost in aged animals (152).

In summary, even if reperfusion is essential to skeletal muscle survival, numerous deleterious events occur in muscular fibers and mitochondria following reperfusion. Excessive ROS production, Ca2+ overload, mitochondrial dysfunction, and mPTP opening lead to myocyte death, as detailed chronologically in Fig. 4B.

Phenomena Associated with Skeletal Muscle Injuries Following I/R

Morphological changes in the entire muscle environment.

Muscle cell structural changes and morphological lesions were identified during ischemia, with the degree of severity increasing with the duration of ischemia and during reperfusion, when alterations increase (22, 88, 96, 118, 182). Hindlimb ischemia alters the fiber structure and begins to disorganize and degenerate myocytes. Fibers are atrophic, have smaller diameters, and are cytoplasmically heterogeneous, and the morphology of their mitochondrial cristae is modified (13, 22). Ischemia also progressively alters the microcirculation and endothelial cells. Vascular permeability increases following complete disjunction of adjacent endothelial cells, and endothelial cells develop interspersed edema. Furthermore, erythrocytic, thrombotic, and leukocytic interactions develop in the microcirculation after ≥4 h of ischemia (13).

Reperfusion further degenerates fibers that are highly disorganized and hypercontracted, with clusters of mitochondria and SR swelling. In the microcirculation, red blood cells are compacted and deform and break the endothelium, which damages the local environment (13, 22). Cytosolic enzymes are released into the blood circulation, and ROS are produced by XO through 1) oxygen molecules, which mediate prominent thrombotic interactions, characterized by an increase in platelets (13), and 2) leukocytic interactions, characterized by white blood cell adherence, infiltration, and activation (see below). Muscle tissue shows edema, inflammation, and necrosis, contributing to the no-reflow phenomenon (13, 63). Necrosis still develops 72 h after reperfusion, whereas edema progressively disappears. Severe inflammatory infiltrates are observed at 24 h of reperfusion and decrease at 72 h, when regeneration phenomena were observed (22).

Impairments in mitochondrial dynamics.

Mitochondria are dynamic and motile organelles that continuously collide, fuse, or divide (197). Emerging data suggest that changes in mitochondrial dynamics occur in response to acute I/R and are involved in deleterious effects, modifying mitochondrial morphology and functions (19, 131). Although mechanisms are unclear, a high cytosolic Ca2+ concentration and an imbalance between fission and fusion proteins seem to be involved. Indeed, several research groups have demonstrated in cardiomyocytes that simulated I/R reduces fusion protein expression [optic atropy-1 (OPA-1) and mitofusin 2] and increases fission protein expression [dynamin-related peptide 1 (DRP-1) and mitochondrial fission protein 1], which modify mitochondrial morphology (fragmentation and changes in cristae) and motility, alter mitochondrial functions, and favor mPTP opening and cell death (16, 29, 79, 132, 187). Ong et al. (132) showed that simulated I/R in HL-1 cells increases mitochondrial fission through DRP-1 and that transfection of HL-1 cells with fusion proteins or with a dominant-negative mutant form of DRP-1 protects cells from I/R damage. Varanita et al. (187) demonstrated that mild OPA-1 overexpression in transgenic mice protects from muscular atrophy and I/R damage in the heart and brain. These protections imply the preservation of mitochondrial morphology in OPA-1 transgenic mice, as mitochondria are longer in diaphragm muscle and cristae are tighter in the heart. Furthermore, recent work has demonstrated that protection against cardiac I/R injury implies inhibition of mitochondrial fission, either directly by inhibiting fission machinery (41) or via remote ischemic preconditioning (24). Mitochondrial dynamics in skeletal muscle have been studied during exercise (44), but not during I/R, which is an important area for future studies.

Recently, Picard et al. (144) demonstrated that muscle contractile inactivation alters mitochondrial morphology and mitochondrial dynamics. They showed that mechanical ventilation suppresses the contractile activity of the diaphragm, resulting in the increase in mitochondrial fragmentation that can favor ROS production and apoptosis. This study raises an important point about acute experimental models of prolonged ischemia, where animals are anesthetized and immobile: the contractile inactivation could be a confounding factor and contribute to I/R injury via alterations in mitochondrial dynamics.

Local and systemic inflammation.

Ischemia induces numerous modifications of cellular molecules that pave the way for inflammation following reperfusion. Damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), which are endogenous molecules derived from damaged cells, are implied in the inflammatory response following ischemia. They notably include high-mobility group box 1 and ATP (75, 136, 164, 196). Mitochondria altered by different cellular stresses and necrosis also release mitochondrial DNA, which could be involved in I/R-induced inflammation (102, 127, 143, 203). In several organs, DAMPs are ligands of Toll-like receptors (TLR), which participate in inflammation through the release of cytokines, chemokines, and interferons during the pathogenesis of ischemic injury. It has been suggested that TLR are also implied in the skeletal muscle inflammatory response (52, 60, 94, 99), and, for the first time, Patel et al. (136) recently showed that some of these TLR are upregulated in muscle biopsies of patients with critical limb ischemia, the most severe form of PAD. Other molecules secreted or expressed during ischemia participate in inflammation. Nonmuscle myosin heavy chain type II, a stress-induced self-antigen, is expressed on the cell surface (201). Chemokines are locally secreted (169, 186), and adhesion receptors, such as E-selectin and ICAM-1, are expressed on the surface of endothelial cells (51, 117).

At reperfusion, in association with muscle and endothelial cell injuries listed above and adhesion molecules expressed at the cell surface during ischemia, ROS produced via XO in endothelial cells elicit an intense proinflammatory response that increases muscle damage (21, 63, 89, 116). Indeed, ROS participate in the elaboration of chemoattractant stimuli and expression and/or activation of adhesion molecules to allow the interaction between neutrophils and endothelial cells. Leukocyte recruitment involves a complex series of events requiring several adhesive molecules (for review see Refs. 13, 56, 63, and 90). Briefly, leukocytes, particularly neutrophils, attracted by chemokines accumulate in the microcirculation during reperfusion (21, 163, 167, 202) and express adhesion molecules, such as CD11/CD18, at their surface. In the presence of adhesion molecules, such as E-selectin, P-selectin, and ICAM-1, at the endothelial cell surface, neutrophils migrate into the extravascular space through endothelial adhesion receptors, where they are activated via sensing of DAMPs by innate immune receptors (62, 161). Once activated, neutrophils also produce ROS through NADPH oxidases, and this burst of ROS causes further cell injuries such as lipid peroxidation (56, 63). Leukocyte extravasation in the reperfused muscle is highly correlated with muscle injury (166). Neutrophils are among the first cells recruited to the inflammatory site, at 1 h after reperfusion. In association with other phenomena, such as complement and coagulation activation (4, 61), they provoke muscle cell lysis and necrosis through their myeloperoxidase activity (124, 171) and contribute to the no-reflow phenomenon (62, 63), increasing I/R-induced tissue damage. Macrophages reach the ischemic site 48–72 h after reperfusion (68, 170). Their exact role remains unclear, since they may be implicated in both I/R-induced tissue damage and recovery; Hammers et al. (68) identified two prominent macrophage populations (inflammatory and anti-inflammatory) at 3 and 5 days of reperfusion. Noncellular factors, especially natural IgM, also mediate reperfusion injury by recognizing nonmuscle myosin heavy chain type II expressed during ischemia and activating the complement system (6, 201).

Succinate could also participate in inflammation during I/R. Indeed, Chouchani et al. (30) demonstrated in the heart and other organs that accumulation of succinate during ischemia leads to deleterious effects through ROS production by the mitochondrial respiratory chain and can participate in inflammation. Recent evidence supports the idea that this metabolite acts as a proinflammatory signal via direct (i.e., stabilizing hypoxia-inducible factor-1α and favoring inflammation via IL-1β) and indirect (i.e., producing ROS for stabilizing hypoxia-inducible factor-1α) mechanisms (119).

Depending on the skeletal muscle mass subjected to I/R and the duration of ischemia, systemic inflammation and remote organ failure can occur following an increase in enzymes and cellular molecules in the systemic circulation, a phenomenon known as “crush syndrome” (173). Several proinflammatory cytokines produced during I/R, especially TNFα and IL-1, can mediate lung failure (167). A high level of K+ leads to cardiac dysfunction, whereas the release of myoglobin causes renal failure (47). Other factors are implied in multiple organ lesions after hindlimb I/R (199, 200).

CONCLUSION

Skeletal muscle I/R injury is an important clinical problem in PAD that, if not promptly treated, results in significant morbidity and mortality. I/R injury begins with biochemical and morphological changes, and mitochondria play a crucial role, as they are at the crossroads of energy production, cell signaling, oxidative stress, and cell death. Mitochondrial damage can lead to cell death, contribute to inflammation, and elicit changes in remote organs (Fig. 5). Numerous pharmacological and surgical interventions have improved patient recovery and clinical outcome. However, knowledge of mechanisms responsible for I/R and their chronology will allow the development of new therapies. Emerging data on mitochondrial dynamics should identify new therapeutic targets and develop protective strategies against PAD.

Fig. 5.

Schematic overview of the chronology of myocyte ischemia-reperfusion injury. Ischemia triggers deleterious events that become irreversible after 3 h and induce total myocyte death at ∼7 h. Necessary, but late, reperfusion rapidly induces mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) opening and inflammation, causing further myocyte death and remote organ failure. ROS, reactive oxygen species.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.P. and A.-L.C. prepared the figures; S.P. drafted the manuscript; S.P., A.-L.C., A.M., A.L., J.W.S., N.C., J.Z., and B.G. edited and revised the manuscript; S.P., A.-L.C., A.M., A.L., J.W.S., N.C., J.Z., and B.G. approved the final version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdulhannan P, Russell DA, Homer-Vanniasinkam S. Peripheral arterial disease: a literature review. Br Med Bull 104: 21–39, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Addison PD, Neligan PC, Ashrafpour H, Khan A, Zhong A, Moses M, Forrest CR, Pang CY. Noninvasive remote ischemic preconditioning for global protection of skeletal muscle against infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H1435–H1443, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson EJ, Neufer PD. Type II skeletal myofibers possess unique properties that potentiate mitochondrial H2O2 generation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 290: C844–C851, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arumugam TV, Shiels IA, Woodruff TM, Granger DN, Taylor SM. The role of the complement system in ischemia-reperfusion injury. Shock 21: 401–409, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Assaly R, de Tassigny AD, Paradis S, Jacquin S, Berdeaux A, Morin D. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening and cell death during hypoxia-reoxygenation in adult cardiomyocytes. Eur J Pharmacol 675: 6–14, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Austen WG Jr, Zhang M, Chan R, Friend D, Hechtman HB, Carroll MC, Moore FD Jr. Murine hindlimb reperfusion injury can be initiated by a self-reactive monoclonal IgM. Surgery 136: 401–406, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barbieri E, Sestili P. Reactive oxygen species in skeletal muscle signaling. J Signal Transduct 2012: 982794, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baudry N, Laemmel E, Vicaut E. In vivo reactive oxygen species production induced by ischemia in muscle arterioles of mice: involvement of xanthine oxidase and mitochondria. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H821–H828, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baylor SM, Hollingworth S. Sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release compared in slow-twitch and fast-twitch fibres of mouse muscle. J Physiol 551: 125–138, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baylor SM, Hollingworth S. Intracellular calcium movements during excitation-contraction coupling in mammalian slow-twitch and fast-twitch muscle fibers. J Gen Physiol 139: 261–272, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belkin M, Brown RD, Wright JG, LaMorte WW, Hobson RW 2nd. A new quantitative spectrophotometric assay of ischemia-reperfusion injury in skeletal muscle. Am J Surg 156: 83–86, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berchtold MW, Brinkmeier H, Müntener M. Calcium ion in skeletal muscle: its crucial role for muscle function, plasticity, and disease. Physiol Rev 80: 1215–1265, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blaisdell FW. The pathophysiology of skeletal muscle ischemia and the reperfusion syndrome: a review. Cardiovasc Surg 10: 620–630, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonaca MP, Creager MA. Pharmacological treatment and current management of peripheral artery disease. Circ Res 116: 1579–1598, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bouitbir J, Charles AL, Echaniz-Laguna A, Kindo M, Daussin F, Auwerx J, Piquard F, Geny B, Zoll J. Opposite effects of statins on mitochondria of cardiac and skeletal muscles: a “mitohormesis” mechanism involving reactive oxygen species and PGC-1. Eur Heart J 33: 1397–1407, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brady NR, Hamacher-Brady A, Gottlieb RA. Proapoptotic BCL-2 family members and mitochondrial dysfunction during ischemia/reperfusion injury, a study employing cardiac HL-1 cells and GFP biosensors. Biochim Biophys Acta 1757: 667–678, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brandão ML, Roselino JE, Piccinato CE, Cherri J. Mitochondrial alterations in skeletal muscle submitted to total ischemia. J Surg Res 110: 235–240, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bushell AJ, Klenerman L, Davies H, Grierson I, McArdle A, Jackson MJ. Ischaemic preconditioning of skeletal muscle. 2. Investigation of the potential mechanisms involved. J Bone Joint Surg Br 84: 1189–1193, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Calo L, Dong Y, Kumar R, Przyklenk K, Sanderson TH. Mitochondrial dynamics: an emerging paradigm in ischemia-reperfusion injury. Curr Pharm Des 19: 6848–6857, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Capel F, Barquissau V, Richard R, Morio B. Evaluation of mitochondrial functions and dysfunctions in muscle biopsy samples. In: Muscle Biopsy, edited by Sundaram C. Rijeka, Croatia: InTech, 2012, p. 85–110. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carden DL, Smith JK, Korthuis RJ. Neutrophil-mediated microvascular dysfunction in postischemic canine skeletal muscle. Role of granulocyte adherence. Circ Res 66: 1436–1444, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carmo-Araújo EM, Dal-Pai-Silva M, Dal-Pai V, Cecchini R, Anjos Ferreira AL. Ischaemia and reperfusion effects on skeletal muscle tissue: morphological and histochemical studies. Int J Exp Pathol 88: 147–154, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carroll SL, Klein MG, Schneider MF. Decay of calcium transients after electrical stimulation in rat fast- and slow-twitch skeletal muscle fibres. J Physiol 501: 573–588, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cellier L, Tamareille S, Kalakech H, Guillou S, Lenaers G, Prunier F, Mirebeau-Prunier D. Remote ischemic conditioning influences mitochondrial dynamics. Shock 45: 192–197, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan RK, Austen WG Jr, Ibrahim S, Ding GY, Verna N, Hechtman HB, Moore FD Jr. Reperfusion injury to skeletal muscle affects primarily type II muscle fibers. J Surg Res 122: 54–60, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Charles AL, Dufour S, Tran TN, Bouitbir J, Geny B, Zoll J. Metabolic exploration of muscle biopsy. In: Muscle Biopsy, edited by Sundaram C. Rijeka, Croatia: InTech, 2012, p. 111–132. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Charles AL, Lejay A, Zoll J, Chakfe N, Geny B. Re: “Protective effect of focal adhesion kinase against skeletal muscle reperfusion injury after acute limb ischemia.” Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 49: 753, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Charles AL, Guilbert AS, Bouitbir J, Goette-Di Marco P, Enache I, Zoll J, Piquard F, Geny B. Effect of postconditioning on mitochondrial dysfunction in experimental aortic cross-clamping. Br J Surg 98: 511–516, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen L, Gong Q, Stice JP, Knowlton AA. Mitochondrial OPA1, apoptosis, and heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 84: 91–99, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chouchani ET, Pell VR, Gaude E, Aksentijević D, Sundier SY, Robb EL, Logan A, Nadtochiy SM, Ord EN, Smith AC, Eyassu F, Shirley R, Hu CH, Dare AJ, James AM, Rogatti S, Hartley RC, Eaton S, Costa AS, Brookes PS, Davidson SM, Duchen MR, Saeb-Parsy K, Shattock MJ, Robinson AJ, Work LM, Frezza C, Krieg T, Murphy MP. Ischaemic accumulation of succinate controls reperfusion injury through mitochondrial ROS. Nature 515: 431–435, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chouchani ET, Pell VR, James AM, Work LM, Saeb-Parsy K, Frezza C, Krieg T, Murphy MP. A unifying mechanism for mitochondrial superoxide production during ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cell Metab 23: 254–263, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen MV, Yang XM, Downey JM. Acidosis, oxygen, and interference with mitochondrial permeability transition pore formation in the early minutes of reperfusion are critical to postconditioning's success. Basic Res Cardiol 103: 464–471, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Colloca G, Santoro M, Gambassi G. Age-related physiologic changes and perioperative management of elderly patients. Surg Oncol 19: 124–130, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cote CG, Yu FS, Zulueta JJ, Vosatka RJ, Hassoun PM. Regulation of intracellular xanthine oxidase by endothelial-derived nitric oxide. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 271: L869–L874, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Criqui MH, Aboyans V. Epidemiology of peripheral artery disease. Circ Res 116: 1509–1526, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Daiber A, Di Lisa F, Oelze M, Kröller-Schön S, Steven S, Schulz E, Münzel T. Crosstalk of mitochondria with NADPH oxidase via reactive oxygen and nitrogen species signalling and its role for vascular function. Br J Pharmacol. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Hemptinne A, Huguenin F. The influence of muscle respiration and glycolysis on surface and intracellular pH in fibres of the rat soleus. J Physiol 347: 581–592, 1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Di Lisa F, Canton M, Carpi A, Kaludercic N, Menabò R, Menazza S, Semenzato M. Mitochondrial injury and protection in ischemic pre- and postconditioning. Antioxid Redox Signal 14: 881–891, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dick F, Li J, Giraud MN, Kalka C, Schmidli J, Tevaearai H. Basic control of reperfusion effectively protects against reperfusion injury in a realistic rodent model of acute limb ischemia. Circulation 118: 1920–1928, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dikalov S. Cross talk between mitochondria and NADPH oxidases. Free Radic Biol Med 51: 1289–1301, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Disatnik MH, Ferreira JC, Campos JC, Gomes KS, Dourado PM, Qi X, Mochly-Rosen D. Acute inhibition of excessive mitochondrial fission after myocardial infarction prevents long-term cardiac dysfunction. J Am Heart Assoc 2: e000461, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dobashi K, Ghosh B, Orak JK, Singh I, Singh AK. Kidney ischemia-reperfusion: modulation of antioxidant defenses. Mol Cell Biochem 205: 1–11, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doughan AK, Harrison DG, Dikalov SI. Molecular mechanisms of angiotensin II-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction: linking mitochondrial oxidative damage and vascular endothelial dysfunction. Circ Res 102: 488–496, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Drake JC, Wilson RJ, Yan Z. Molecular mechanisms for mitochondrial adaptation to exercise training in skeletal muscle. FASEB J 30: 13–22, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dupont-Versteegden EE. Apoptosis in skeletal muscle and its relevance to atrophy. World J Gastroenterol 12: 7463–7466, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eisner V, Lenaers G, Hajnóczky G. Mitochondrial fusion is frequent in skeletal muscle and supports excitation-contraction coupling. J Cell Biol 205: 179–195, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eliason JL, Wakefield TW. Metabolic consequences of acute limb ischemia and their clinical implications. Semin Vasc Surg 22: 29–33, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fariss MW, Chan CB, Patel M, Van Houten B, Orrenius S. Role of mitochondria in toxic oxidative stress. Mol Interv 5: 94–111, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ferguson RA, Ball D, Krustrup P, Aagaard P, Kjaer M, Sargeant AJ, Hellsten Y, Bangsbo J. Muscle oxygen uptake and energy turnover during dynamic exercise at different contraction frequencies in humans. J Physiol 536: 261–271, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Flück M, von Allmen RS, Ferrié C, Tevaearai H, Dick F. Protective effect of focal adhesion kinase against skeletal muscle reperfusion injury after acute limb ischemia. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 49: 306–313, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Formigli L, Manneschi LI, Adembri C, Orlandini SZ, Pratesi C, Novelli GP. Expression of E-selectin in ischemic and reperfused human skeletal muscle. Ultrastruct Pathol 19: 193–200, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Frost RA, Nystrom GJ, Lang CH. Multiple Toll-like receptor ligands induce an IL-6 transcriptional response in skeletal myocytes. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 290: R773–R784, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Trojel-Hansen C, Kroemer G. Mitochondrial control of cellular life, stress, and death. Circ Res 111: 1198–1207, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gardner AW, Afaq A. Management of lower extremity peripheral arterial disease. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 28: 349–357, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gissel H. The role of Ca2+ in muscle cell damage. Ann NY Acad Sci 1066: 166–180, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Grace PA. Ischaemia-reperfusion injury. Br J Surg 81: 637–647, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Granger DN, Kvietys PR. Reperfusion injury and reactive oxygen species: the evolution of a concept. Redox Biol 6: 524–551, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Griffiths EJ, Halestrap AP. Mitochondrial non-specific pores remain closed during cardiac ischaemia, but open upon reperfusion. Biochem J 307: 93–98, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grisotto PC, dos Santos AC, Coutinho-Netto J, Cherri J, Piccinato CE. Indicators of oxidative injury and alterations of the cell membrane in the skeletal muscle of rats submitted to ischemia and reperfusion. J Surg Res 92: 1–6, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Grundtman C, Bruton J, Yamada T, Ostberg T, Pisetsky DS, Harris HE, Andersson U, Lundberg IE, Westerblad H. Effects of HMGB1 on in vitro responses of isolated muscle fibers and functional aspects in skeletal muscles of idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. FASEB J 24: 570–578, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guillot M, Charles AL, Chamaraux-Tran TN, Bouitbir J, Meyer A, Zoll J, Schneider F, Geny B. Oxidative stress precedes skeletal muscle mitochondrial dysfunction during experimental aortic cross-clamping but is not associated with early lung, heart, brain, liver, or kidney mitochondrial impairment. J Vasc Surg 60: 1043–1051, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Guillot M, Pottecher J, Boisramé-Helms J, Meyer A, Charles AL, Mansour Z, Diemunsch P, Zoll J, Geny B. Involvement of inflammation on skeletal muscle ischemia-reperfusion deleterious effects. In: Skeletal Muscle: Physiology, Classification and Disease. New York: Nova Science, 2013, chapt. 5. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gute DC, Ishida T, Yarimizu K, Korthuis RJ. Inflammatory responses to ischemia and reperfusion in skeletal muscle. Mol Cell Biochem 179: 169–187, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hagberg H. Intracellular pH during ischemia in skeletal muscle: relationship to membrane potential, extracellular pH, tissue lactic acid and ATP. Pflügers Arch 404: 342–347, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Halestrap AP, Richardson AP. The mitochondrial permeability transition: a current perspective on its identity and role in ischaemia/reperfusion injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol 78: 129–141, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Haljamäe H, Enger E. Human skeletal muscle energy metabolism during and after complete tourniquet ischemia. Ann Surg 182: 9–14, 1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hamburg NM, Balady GJ. Exercise rehabilitation in peripheral artery disease: functional impact and mechanisms of benefits. Circulation 123: 87–97, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hammers DW, Rybalko V, Merscham-Banda M, Hsieh PL, Suggs LJ, Farrar RP. Anti-inflammatory macrophages improve skeletal muscle recovery from ischemia-reperfusion. J Appl Physiol 118: 1067–1074, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hansel G, Ramos DB, Delgado CA, Souza DG, Almeida RF, Portela LV, Quincozes-Santos A, Souza DO. The potential therapeutic effect of guanosine after cortical focal ischemia in rats. PLos One 9: e90693, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Harris K, Walker PM, Mickle DA, Harding R, Gatley R, Wilson GJ, Kuzon B, McKee N, Romaschin AD. Metabolic response of skeletal muscle to ischemia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 250: H213–H220, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hiatt WR, Armstrong EJ, Larson CJ, Brass EP. Pathogenesis of the limb manifestations and exercise limitations in peripheral artery disease. Circ Res 116: 1527–1539, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hultman E, Sjöholm H. Energy metabolism and contraction force of human skeletal muscle in situ during electrical stimulation. J Physiol 345: 525–532, 1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Inserte J, Ruiz-Meana M, Rodríguez-Sinovas A, Barba I, Garcia-Dorado D. Contribution of delayed intracellular pH recovery to ischemic postconditioning protection. Antioxid Redox Signal 14: 923–939, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ivanics T, Miklós Z, Ruttner Z, Bátkai S, Slaaf DW, Reneman RS, Tóth A, Ligeti L. Ischemia/reperfusion-induced changes in intracellular free Ca2+ levels in rat skeletal muscle fibers—an in vivo study. Pflügers Arch 440: 302–308, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Iyer SS, Pulskens WP, Sadler JJ, Butter LM, Teske GJ, Ulland TK, Eisenbarth SC, Florquin S, Flavell RA, Leemans JC, Sutterwala FS. Necrotic cells trigger a sterile inflammatory response through the Nlrp3 inflammasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 20388–20393, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jackson MJ, Pye D, Palomero J. The production of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species by skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol 102: 1664–1670, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jackson MJ. Control of reactive oxygen species production in contracting skeletal muscle. Antioxid Redox Signal 15: 2477–2486, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jassem W, Fuggle SV, Rela M, Koo DD, Heaton ND. The role of mitochondria in ischemia/reperfusion injury. Transplantation 73: 493–499, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Javadov S, Rajapurohitam V, Kilić A, Hunter JC, Zeidan A, Said Faruq N, Escobales N, Karmazyn M. Expression of mitochondrial fusion-fission proteins during post-infarction remodeling: the effect of NHE-1 inhibition. Basic Res Cardiol 106: 99–109, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jennings RB, Sommers HM, Smyth GA, Flack HA, Linn H. Myocardial necrosis induced by temporary occlusion of a coronary artery in the dog. Arch Pathol 70: 68–78, 1960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jennings RB, Reimer KA. Factors involved in salvaging ischemic myocardium: effect of reperfusion of arterial blood. Circulation 68: I25–I36, 1983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ji LL. Antioxidant enzyme response to exercise and aging. Med Sci Sports Exerc 25: 225–231, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kalogeris T, Baines CP, Krenz M, Korthuis RJ. Cell biology of ischemia/reperfusion injury. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 298: 229–317, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Katz A. Differential responses of glycogen synthase to ischaemia and ischaemic contraction in human skeletal muscle. Exp Physiol 82: 203–211, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kay L, Nicolay K, Wieringa B, Saks V, Wallimann T. Direct evidence for the control of mitochondrial respiration by mitochondrial creatine kinase in oxidative muscle cells in situ. J Biol Chem 275: 6937–6944, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Khanna A, Cowled PA, Fitridge RA. Nitric oxide and skeletal muscle reperfusion injury: current controversies. J Surg Res 128: 98–107, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Klenerman L, Lowe NM, Miller I, Fryer PR, Green CJ, Jackson MJ. Dantrolene sodium protects against experimental ischemia and reperfusion damage to skeletal muscle. Acta Orthop Scand 66: 352–358, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kocman EA, Ozatik O, Sahin A, Guney T, Kose AA, Dag I, Alatas O, Cetin C. Effects of ischemic preconditioning protocols on skeletal muscle ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Surg Res 193: 942–952, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Korthuis RJ, Granger DN. Reactive oxygen metabolites, neutrophils, and the pathogenesis of ischemic-tissue/reperfusion. Clin Cardiol 16: I19–I26, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Korthuis RJ, Gute DC. Postischemic leukocyte/endothelial cell interactions and microvascular barrier dysfunction in skeletal muscle: cellular mechanisms and effect of Daflon 500 mg. Int J Microcirc Clin Exp 17 Suppl 1: 11–7, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Krishna SM, Omer SM, Golledge J. Evaluation of the clinical relevance and limitations of current pre-clinical models of peripheral artery disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 130: 127–150, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kuzon WM Jr, Walker PM, Mickle DA, Harris KA, Pynn BR, McKee NH. An isolated skeletal muscle model suitable for acute ischemia studies. J Surg Res 41: 24–32, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lagerwall K, Madhu B, Daneryd P, Scherstén T, Soussi B. Purine nucleotides and phospholipids in ischemic and reperfused rat skeletal muscle: effect of ascorbate. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 272: H83–H90, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lang CH, Silvis C, Deshpande N, Nystrom G, Frost RA. Endotoxin stimulates in vivo expression of inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-1β, -6, and high-mobility-group protein-1 in skeletal muscle. Shock 19: 538–546, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lejay A, Charles AL, Zoll J, Bouitbir J, Thaveau F, Piquard F, Geny B. Skeletal muscle mitochondrial function in peripheral arterial disease: usefulness of muscle biopsy. In: Muscle Biopsy, edited by Sundaram C. Rijeka, Croatia: InTech, 2012, p. 133–154. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lejay A, Choquet P, Thaveau F, Singh F, Schlagowski A, Charles AL, Laverny G, Metzger D, Zoll J, Chakfe N, Geny B. A new murine model of sustainable and durable chronic critical limb ischemia fairly mimicking human pathology. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 49: 205–212, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lejay A, Meyer A, Schlagowski AI, Charles AL, Singh F, Bouitbir J, Pottecher J, Chakfé N, Zoll J, Geny B. Mitochondria: mitochondrial participation in ischemia-reperfusion injury in skeletal muscle. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 50: 101–105, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lepore DA. Nitric oxide synthase-independent generation of nitric oxide in muscle ischemia-reperfusion injury. Nitric Oxide 4: 541–545, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Liu Y, Steinacker JM. Changes in skeletal muscle heat shock proteins: pathological significance. Front Biosci 6: D12–D25, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Liu R, Jin P, Yu L, Wang Y, Han L, Shi T, Li X. Impaired mitochondrial dynamics and bioenergetics in diabetic skeletal muscle. PLos One 9: e92810, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lotfi S, Patel AS, Mattock K, Egginton S, Smith A, Modarai B. Towards a more relevant hind limb model of muscle ischaemia. Atherosclerosis 227: 1–8, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lu B, Kwan K, Levine YA, Olofsson PS, Yang H, Li J, Joshi S, Wang H, Andersson U, Chavan SS, Tracey KJ. α7-Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor signaling inhibits inflammasome activation by preventing mitochondrial DNA release. Mol Med 20: 350–358, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lundberg J, Elander A, Soussi B. Effect of hypothermia on the ischemic and reperfused rat skeletal muscle, monitored by in vivo 31P-magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Microsurgery 21: 366–373, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lundberg J, Lindgård A, Elander A, Soussi B. Improved energetic recovery of skeletal muscle in response to ischemia and reperfusion injury followed by in vivo 31P-magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Microsurgery 22: 158–164, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lynch GS, Fary CJ, Williams DA. Quantitative measurement of resting skeletal muscle [Ca2+]i following acute and long-term downhill running exercise in mice. Cell Calcium 22: 373–383, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.MacInnes A, Timmons JA. Metabolic adaptations to repeated periods of contraction with reduced blood flow in canine skeletal muscle. BMC Physiol 5: 11, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mansour Z, Charles AL, Bouitbir J, Pottecher J, Kindo M, Mazzucotelli JP, Zoll J, Geny B. Remote and local ischemic postconditioning further impaired skeletal muscle mitochondrial function after ischemia-reperfusion. J Vasc Surg 56: 774–782, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mansour Z, Bouitbir J, Charles AL, Talha S, Kindo M, Pottecher J, Zoll J, Geny B. Remote and local ischemic preconditioning equivalently protects rat skeletal muscle mitochondrial function during experimental aortic cross-clamping. J Vasc Surg 55: 497–505, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Marcinek DJ, Kushmerick MJ, Conley KE. Lactic acidosis in vivo: testing the link between lactate generation and H+ accumulation in ischemic mouse muscle. J Appl Physiol 108: 1479–1486, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Martou G, O'Blenes CA, Huang N, McAllister SE, Neligan PC, Ashrafpour H, Pang CY, Lipa JE. Development of an in vitro model for study of the efficacy of ischemic preconditioning in human skeletal muscle against ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Appl Physiol 101: 1335–1342, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Mason S, Wadley GD. Skeletal muscle reactive oxygen species: a target of good cop/bad cop for exercise and disease. Redox Rep 19: 97–106, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.McAllister SE, Ashrafpour H, Cahoon N, Huang N, Moses MA, Neligan PC, Forrest CR, Lipa JE, Pang CY. Postconditioning for salvage of ischemic skeletal muscle from reperfusion injury: efficacy and mechanism. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295: R681–R689, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.McArdle A, Pattwell D, Vasilaki A, Griffiths RD, Jackson MJ. Contractile activity-induced oxidative stress: cellular origin and adaptive responses. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 280: C621–C627, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.McDermott MM. Lower extremity manifestations of peripheral artery disease: the pathophysiologic and functional implications of leg ischemia. Circ Res 116: 1540–1550, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.McMillan EM, Quadrilatero J. Differential apoptosis-related protein expression, mitochondrial properties, proteolytic enzyme activity, and DNA fragmentation between skeletal muscles. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 300: R531–R543, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Menger MD, Lehr HA, Messmer K. Role of oxygen radicals in the microcirculatory manifestations of postischemic injury. Klin Wochenschr 69: 1050–1055, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Merchant SH, Gurule DM, Larson RS. Amelioration of ischemia-reperfusion injury with cyclic peptide blockade of ICAM-1. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 284: H1260–H1268, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Messina LM. In vivo assessment of acute microvascular injury after reperfusion of ischemic tibialis anterior muscle of the hamster. J Surg Res 48: 615–621, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Mills E, O'Neill LA. Succinate: a metabolic signal in inflammation. Trends Cell Biol 24: 313–320, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Mishra P, Varuzhanyan G, Pham AH, Chan DC. Mitochondrial dynamics is a distinguishing feature of skeletal muscle fiber types and regulates organellar compartmentalization. Cell Metab 22: 1033–1044, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Miura T, Tanno M. The mPTP and its regulatory proteins: final common targets of signalling pathways for protection against necrosis. Cardiovasc Res 94: 181–189, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Morciano G, Giorgi C, Bonora M, Punzetti S, Pavasini R, Wieckowski MR, Campo G, Pinton P. Molecular identity of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore and its role in ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol 78: 142–153, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Moses MA, Addison PD, Neligan PC, Ashrafpour H, Huang N, McAllister SE, Lipa JE, Forrest CR, Pang CY. Inducing late phase of infarct protection in skeletal muscle by remote preconditioning: efficacy and mechanism. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 289: R1609–R1617, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Nguyen HX, Lusis AJ, Tidball JG. Null mutation of myeloperoxidase in mice prevents mechanical activation of neutrophil lysis of muscle cell membranes in vitro and in vivo. J Physiol 565: 403–413, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Noll E, Bouitbir J, Collange O, Zoll J, Charles AL, Thaveau F, Diemunsch P, Geny B. Local but not systemic capillary lactate is a reperfusion biomarker in experimental acute limb ischaemia. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 43: 339–340, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Norgren L, Hiatt WR, Dormandy JA, Nehler MR, Harris KA, Fowkes FG, TASCII Working Group. Inter-society consensus for the management of peripheral arterial disease (TASCII). J Vasc Surg 45: S5–S67, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Oka T, Hikoso S, Yamaguchi O, Taneike M, Takeda T, Tamai T, Oyabu J, Murakawa T, Nakayama H, Nishida K, Akira S, Yamamoto A, Komuro I, Otsu K. Mitochondrial DNA that escapes from autophagy causes inflammation and heart failure. Nature 485: 251–255, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.O'Neill CA, Stebbins CL, Bonigut S, Halliwell B, Longhurst JC. Production of hydroxyl radicals in contracting skeletal muscle of cats. J Appl Physiol 81: 1197–1206, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Ong SB, Hausenloy DJ. Mitochondrial morphology and cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Res 88: 16–29, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Ong SB, Samangouei P, Kalkhoran SB, Hausenloy DJ. The mitochondrial permeability transition pore and its role in myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol 78: 23–34, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Ong SB, Hall AR, Hausenloy DJ. Mitochondrial dynamics in cardiovascular health and disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 19: 400–414, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Ong SB, Subrayan S, Lim SY, Yellon DM, Davidson SM, Hausenloy DJ. Inhibiting mitochondrial fission protects the heart against ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circulation 121: 2012–2022, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Ostman B, Michaelsson K, Rahme H, Hillered L. Tourniquet-induced ischemia and reperfusion in human skeletal muscle. Clin Orthop Relat Res 418: 260–265, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Palomero J, Pye D, Kabayo T, Spiller DG, Jackson MJ. In situ detection and measurement of intracellular reactive oxygen species in single isolated mature skeletal muscle fibers by real time fluorescence microscopy. Antioxid Redox Signal 10: 1463–1474, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Pang CY, Yang RZ, Zhong A, Xu N, Boyd B, Forrest CR. Acute ischaemic preconditioning protects against skeletal muscle infarction in the pig. Cardiovasc Res 29: 782–788, 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Patel H, Shaw SG, Shi-Wen X, Abraham D, Baker DM, Tsui JC. Toll-like receptors in ischaemia and its potential role in the pathophysiology of muscle damage in critical limb ischaemia. Cardiol Res Pract 2012: 121237, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Perry MO, Fantini G. Ischemia: profile of an enemy. Reperfusion injury of skeletal muscle. J Vasc Surg 6: 231–234, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Petrasek PF, Homer-Vanniasinkam S, Walker PM. Determinants of ischemic injury to skeletal muscle. J Vasc Surg 19: 623–631, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Phaniendra A, Jestadi DB, Periyasamy L. Free radicals: properties, sources, targets, and their implication in various diseases. Indian J Clin Biochem 30: 11–26, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Picard M, Csukly K, Robillard ME, Godin R, Ascah A, Bourcier-Lucas C, Burelle Y. Resistance to Ca2+-induced opening of the permeability transition pore differs in mitochondria from glycolytic and oxidative muscles. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295: R659–R668, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Picard M, Hepple RT, Burelle Y. Mitochondrial functional specialization in glycolytic and oxidative muscle fibers: tailoring the organelle for optimal function. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 302: C629–C641, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Picard M, Gentil BJ, McManus MJ, White K, St Louis K, Gartside SE, Wallace DC, Turnbull DM. Acute exercise remodels mitochondrial membrane interactions in mouse skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol 115: 1562–1571, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Picard M, Juster RP, McEwen BS. Mitochondrial allostatic load puts the “gluc” back in glucocorticoids. Nat Rev Endocrinol 10: 303–310, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Picard M, Azuelos I, Jung B, Giordano C, Matecki S, Hussain S, White K, Li T, Liang F, Benedetti A, Gentil BJ, Burelle Y, Petrof BJ. Mechanical ventilation triggers abnormal mitochondrial dynamics and morphology in the diaphragm. J Appl Physiol 118: 1161–1171, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Pipinos II, Sharov VG, Shepard AD, Anagnostopoulos PV, Katsamouris A, Todor A, Filis KA, Sabbah HN. Abnormal mitochondrial respiration in skeletal muscle in patients with peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg 38: 827–832, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Pipinos II, Judge AR, Zhu Z, Selsby JT, Swanson SA, Johanning JM, Baxter BT, Lynch TG, Dodd SL. Mitochondrial defects and oxidative damage in patients with peripheral arterial disease. Free Radic Biol Med 41: 262–269, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Pipinos II, Judge AR, Selsby JT, Zhu Z, Swanson SA, Nella AA, Dodd SL. The myopathy of peripheral arterial occlusive disease. 1. Functional and histomorphological changes and evidence for mitochondrial dysfunction. Vasc Endovasc Surg 41: 481–489, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Pipinos II, Judge AR, Selsby JT, Zhu Z, Swanson SA, Nella AA, Dodd SL. The myopathy of peripheral arterial occlusive disease. 2. Oxidative stress, neuropathy, and shift in muscle fiber type. Vasc Endovasc Surg 42: 101–112, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Pipinos II, Swanson SA, Zhu Z, Nella AA, Weiss DJ, Gutti TL, McComb RD, Baxter BT, Lynch TG, Casale GP. Chronically ischemic mouse skeletal muscle exhibits myopathy in association with mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295: R290–R296, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]