Abstract

Previous research showed that resveratrol (trans-3,4′,5-trihydroxystilbene) and pinostilbene (trans-3-methoxy-4′,5-dihydroxystilbene) were able to inhibit tyrosinase directly; however, anti-melanogenic effects of pterostilbene (trans-3,5-dimethoxy-4′-hydroxystilbene) and resveratrol trimethyl ether (RTE) have not been compared. To investigate the hypopigmentation effects of pterostilbene and RTE, melanin contents and intracellular tyrosinase activity were determined by western blot analysis. Firstly, pterostilbene showed the inhibitory effects on α-melanocyte stimulating hormone (MSH)-induced melanin synthesis stronger than RTE, resveratrol, and arbutin. Pterostilbene inhibited melanin biosynthesis in a dose-dependent manner in α-MSH-stimulated B16/F10 murine melanoma cells. Specifically, melanin content and intracellular tyrosinase activity were inhibited by 63% and 58%, respectively, in response to treatment with 10 μM of pterostilbene. The results of western blot analysis indicated that pterostilbene induced downregulation of tyrosinase protein expression and suppression of α-MSH-stimulated melan-A protein expression stronger than RTE or resveratrol. Based on these results, our study suggests that pterostilbene can induce hypopigmentation effects more effectively than resveratrol and RTE, and it functions via downregulation of protein expression associated with hyperpigmentation in α-MSH-triggered B16/F10 murine melanoma cells.

Keywords: pterostilbene, methyl resveratrol, depigmentation, tyrosinase, melan-A

INTRODUCTION

Acquired hyperpigmentation disorder is caused by external stimuli, including ultraviolet ray (UVR)-induced pigmentation, postinflammatory pigmentation, chemical/drug-induced pigmentation, and foreign material deposition (1). The anti-melanogenic process against hyperpigmentation can be accomplished by suppressing the transcription and activity of tyrosinase, tyrosinase related protein (TRP)-1, TRP-2, and/or sustained extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) 1/2 by inhibiting related signaling pathways. Tyrosinase and TRP-1 are indispensable enzymes involved in eumelanogenesis. Hypopigmentation is caused by inhibition of the uptake and distribution of melanosomes in keratinocytes, which takes place through induction of melanin and melanosome degradation or expeditious turnover of pigmented keratinocytes. Most hypopigmentation agents act specifically to impede the function of tyrosinase via several mechanisms. For instance, hydroquinone and arbutin work as competitive inhibitors, C2-ceramide and tretionin inhibit through blocking transcription, and linoleic acid and α-linolenic acid act by degrading tyrosinase (2). Additionally, the extracts of several plants and algae have been reported to suppress α-melanocyte stimulating hormone (MSH)-stimulated melanogenesis through sustained ERK 1/2 activation (3–6). There have been several investigations on anti-melanogenesis of methylated compounds, such as diosgenin, α-tocopheryl ferulic acid, and 2,5-dimethyl-4-hydroxy-3(2H)-furanone (7–9). Moreover, other reports show that melanogenesis is stimulated by methoxylated compounds, such as nobiletin, tangeretin, sinensetin, ferulic acid, and scoparone (10–15).

Resveratrol (trans-3,4′,5-trihydroxystilbene), a non-flavonoid polyphenol in the stilbene group, has been reported in various food sources, such as grapes, berries, red wine, chocolate, and peanuts (16–18). The di- and trimethylated anaolgues of resveratol, pterostilbene (trans-3,5-dimethoxy-4′-hydroxystilbene) and resveratrol trimethyl ether (RTE; trans-3,4′,5-trimethoxystilbene) are stilbenoids shown to have higher bioavailability than resveratrol which are found in grapes, blueberries and heart-wood (Pterocarpus marsupium) (19). Pterostilbene has been shown to exert anti-inflammatory, anti-proliferative, and anti-aging effects (20–23) and RTE showed anti-proliferative and/or apoptosis-inductive effects in various cancer cells with potency relatively higher than resveratrol (24–30). Our study shows that the differential hypopigmentation effects of resveratrol and its two methyl analogues can be associated with expression of melan-A and tyrosinase protein in α-MSH-triggered B16/F10 melanoma cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

All solvents were of analytical grade and used without further purification. α-MSH, arbutin, pterostilbene, resveratrol, RTE, and 3,4-dihydroxy-L-phenylalanine (L-DOPA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Arbutin was dissolved in 50% ethanol at a concentration of 360 mM and pterostilbene, resveratrol, and RTE were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide at a concentration of 10 mM. These compounds were used for an in vitro assay.

Antibodies

Antibodies against tyrosinase (M-19, sc-7834-R), melan-A (A103, sc-20032) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotech. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Antibody against β-actin (A2228-0.1) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Co..

Cell culture

B16/F10 murine melanoma cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco BRL), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (10,000 U/mL and 10,000 μg/mL, Gibco BRL). Cells were maintained in a humid atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Assessment of cytotoxicity

Cytotoxicity was determined by a lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release assay. The cytotoxic effects of RTE or arbutin in the presence of α-MSH were estimated by the measurement of LDH in culture media. Leakage of LDH is a well-known marker of damage to the cellular membrane. The cytotoxicity was expressed as the percentage of LDH released (LDH release in media of RTE or arbutin treatment in the presence of α-MSH/maximal LDH release×100). Maximal LDH release was measured after lysis of cells with 0.5% Triton X-100.

Determination of intracellular melanin contents and tyrosinase activity

The cells were seeded into 6 well plates at a density of 1×105 cells/well. The cells were then treated with or without α-MSH and test compounds at 37°C for 2 days. The cells were then washed with 1× phosphate buffered saline and then collected in 1× trypsin-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), after which they were lysed with 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and 1% Triton X-100 in 67 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.8). The samples were sonicated and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C and the supernatants were transfered into new eppendorf tube to measure intracellular tyrosinase activity, and the remaining pellets were used to determine melanin. To extract the melanin from the pellets, 1 N sodium hydroxide (NaOH) was added to the pellets, which was subsequently incubated at 70°C for 30 min. The absorbance was then measured at 405 nm and the corresponding total protein was determined and used to normalize the absorbance. The tyrosinase activity was determined based on the amount of DOPA chrome produced in response to the use of various substrates, including L-tyrosine and L-DOPA. To assess this, 100 μL of supernatants and 100 μL of 12.5 mM L-DOPA were then mixed and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. The absorbance was then measured at 475 nm and the corresponding total protein was determined and used to normalize the absorbance.

Western blot analysis

Cells were collected and lysed in 1× radio immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer [10× RIPA lysis buffer (Upstate, Boston, MA, USA), 0.1 mM PMSF, 0.1 M Na3VO4, 0.5 M NaF, 5 mg/mL aportinin, and 5 mg/mL leupeptin]. Thirty micrograms of protein per lane were then separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and subsequently blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. The nitrocellulose membranes were then blocked with 5% dried milk in tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween 20. Next, the blots were incubated with primary antibodies at a dilution of 1:1,000 and then further incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. The bound antibodies were then detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Amersham Cat. No. RPN2106V2, Amersham Life Science, Arlington Heights, IL, USA).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate. Treatment effects were analyzed using the Student’s t-test. P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Previous research reported that the anti-melanogenic mechanism of oxyresveratrol suppresses tyrosinase in a noncompetitive manner with L-tyrosine as the substrate (31). In addition, resveratrol and pinostilbene (trans-3-methoxy-4′,5-dihydroxystilbene) have been shown to exert inhibitory effects against tyrosinase, while pterostilbene and RTE did not suppress tyrosinase directly (31). To investigate the mechanism of action on hypopigmenting effects of pterostilbene and RTE in α-MSH-stimulated B16/F10 melanoma, cells were incubated with pterostilbene, RTE, resveratrol, or arbutin in the presence of α-MSH at indicated concentrations for 48 h (Fig. 1A). Arbutin was used as a reference. Treatment with 10 μM pterostibene or resveratrol for 48 h did not affect cytotoxicity in α-MSH-stimulated B16/F10 melanoma cells; however, treatment with 10 μM of RTE for 48 h induced cytotoxicity (Fig. 1B). Pterostilbene showed a greater suppressive effect on melanin biosynthesis than RTE, resveratrol, or arbutin (Fig. 1C), and these effects occurred in a dose-dependent manner, with up to 63% of the amount of melanin (Fig. 2A) and 58% of the tyrosinase activity being inhibited in response to treatment with 10 μM of pterostilbene (Fig. 2B). These results show that pterostilbene suppressed melanin synthesis via inhibition of nonspecific tyrosinase, meanwhile, resveratrol and arbutin suppressed melanin synthesis in a tyrosinase-specific manner.

Fig. 1.

Structure and activity relationships for resveratrol and its two methyl analogs. Chemical structures of resveratrol and its two methyl analogs, pterostilbene and resveratrol trimethyl ether (RTE) (A). Effects of resveratrol and its two methyl analogs on cytotoxicity in α-melanocyte stimulating hormone (MSH)-stimulated B16/F10 melanoma cells. Cytotoxicity was determined by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release assay (B). Effects of resveratrol and its two methyl analogs on melanin sysnthesis in α-MSH-stimulated B16/F10 melanoma cells (C). Cells were pre-incubated for 24 h, and then stimulated with α-MSH (50 nM) in the presence of pterostilbene, RTE, resveratrol (10 μM), or arbutin (360 μM). Data are presented as means±SD of three independent experiments. **P<0.01 vs α-MSH-treated cells.

Fig. 2.

Effects of pterostilbene on melanin sysnthesis (A) and intracellular tyrosinase activity (B) in α-melanocyte stimulating hormone (MSH)-stimulated B16/F10 melanoma cells. Cells were pre-incubated for 24 h, and then stimulated with α-MSH (50 nM) in the presence of pterostilbene (2.5, 5, and 10 μM). Data are presented as mean±SD of three independent experiments. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs α-MSH-treated cells.

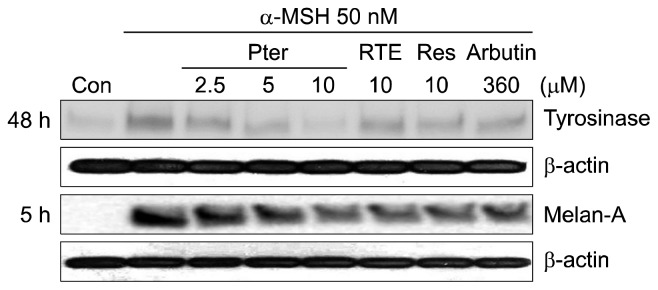

To examine the relationship between proteins associated with melanogenesis in α-MSH-induced B16/F10 murine melanoma, the cells were treated with resveratrol, pterostilbene or RTE in the presence of α-MSH for 5 h or 48 h. The total protein was then isolated and subjected to Western blot analysis. The examination of the protein expression revealed that pterostilbene suppressed tyrosinase protein expression, which is associated with eumelanogenesis, and downregulated melan-A protein expression, which is associated with α-MSH-induced differentiation of B16/F10 murine melanoma cells (Fig. 3). Previous studies have reported that protein melan-A also known as melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1 regulated melanosomal matrix protein Pmel17 processing and the maturation of melanosomes (32). Moreover, recent reports have shown that melanin biosynthesis is induced by methoxylated compounds, such as nobiletin, tangenretin, sinensetin, 4′-O-methylfisetin, scoparone, ferulic acid, while suppressed by diosgenin, α-tocopheryl ferulate, and 2,5-dimethyl-4-hydroxy-3(2H)-furanone (8–15,33,34). In the case of scoparone and ferulic acid, addition of methoxy groups to original compounds (coumarin and p-coumaric acid, respectively) is responsible for stimulating melanogenesis in B16 melanoma cells (13,15).

Fig. 3.

Effects of resveratrol and its two methyl analogs on melanogenic proteins, tyrosinase and melan-A protein levels in α-melanocyte stimulating hormone (MSH)-stimulated B16/F10 melanoma cells. Cells were pre-incubated for 24 h, and then stimulated with α-MSH (50 nM) in the presence of pterostilbene (2.5, 5, and 10 μM), RTE (10 μM), resveratrol (10 μM), or arbutin (360 μM) for 5 h and 48 h. The protein levels of tyrosinanse, melan-A, and β-actin were determined by Western blotting. β-Actin was used as a loading control.

Taken together, this study suggests that pterostilbene can ameliorate acquired hyperpigmentation disorders without cytotoxic effects, and functions via downregulation of tyrosinase protein expression and inhibition of melan-A protein expression in α-MSH-triggered B16/F10 melanoma cells. Furthermore, this research also suggests that pterostilbene can regulate α-MSH-induced melanogenic gene expression more efficiently than resveratrol and RTE.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the 2015 scientific promotion program funded by Jeju National University.

Footnotes

AUTHOR DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yamaguchi Y, Hearing VJ. Melanocytes and their diseases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4:a017046. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a017046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Briganti S, Camera E, Picardo M. Chemical and instrumental approaches to treat hyperpigmentation. Pigment Cell Res. 2003;16:101–110. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0749.2003.00029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoon HS, Kim JK. The inhibitory effect of Acanthopeltis japonica on melanogenesis. J Soc Cosmet Scientists Korea. 2007;33:87–92. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoon HS, Kim JK, Kim SJ. The inhibitory effect on the melanin synthesis in B16/F10 mouse melanoma cells by Sasa quelpaertensis leaf extract. J Life Sci. 2007;17:873–875. doi: 10.5352/JLS.2007.17.6.873. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoon HS, Koh WB, Oh YS, Kim IJ. The anti-melanogenic effects of Petalonia binghamiae extracts in α-melanocyte stimulating hormone-induced B16/F10 murine melanoma cells. J Korean Soc Appl Biol Chem. 2009;52:564–567. doi: 10.3839/jksabc.2009.095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoon HS, Yang KW, Kim JE, Kim JM, Lee NH, Hyun CG. Hypopigmenting effects of extracts from bulbs of Lilium oriental hybrid ‘Siberia’ in murine B16/F10 melanoma cells. J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr. 2014;43:705–711. doi: 10.3746/jkfn.2014.43.5.705. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Funasaka Y, Chakraborty AK, Komoto M, Ohashi A, Ichihashi M. The depigmenting effect of α-tocopheryl ferulate on human melanoma cells. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:20–29. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee J, Jung E, Lee J, Huh S, Boo YC, Hyun CG, Kim YS, Park D. Mechanisms of melanogenesis inhibition by 2,5-dimethyl-4-hydroxy-3(2H)-furanone. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:242–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.07934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee J, Jung K, Kim YS, Park D. Diosgenin inhibits melanogenesis through the activation of phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase pathway (PI3K) signaling. Life Sci. 2007;81:249–254. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoon HS, Kim IJ. Nobiletin induces differentiation of murine B16/F10 melanoma cells. J Korean Soc Appl Biol Chem. 2011;54:353–361. doi: 10.3839/jksabc.2011.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoon HS, Ko HC, Kim SJ, Kim SS, Choi YH, An HJ, Lee NH, Hyun CG. Stimulatory effects of a 5,6,7,3′,4′-pentamethoxyflavone, sinensetin, on melanogenesis in B16/F10 murine melanoma cells. Lat Am J Pharm. 2015;34:1087–1092. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoon HS, Ko HC, Kim SS, Park KJ, An HJ, Choi YH, Kim SJ, Lee NH, Hyun CG. Tangeretin triggers melanogenesis through the activation of melanogenic signaling proteins and sustained extracellular signal-regulated kinase in B16/F10 murine melanoma cells. Nat Prod Commun. 2015;10:389–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoon HS, Lee NH, Hyun CG, Shin DB. Differential effects of methoxylated p-coumaric acids on melanoma in B16/F10 cells. Prev Nutr Food Sci. 2015;20:73–77. doi: 10.3746/pnf.2015.20.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoon HS, Lee SR, Ko HC, Choi SY, Park JG, Kim JK, Kim SJ. Involvement of extracellular signal-regulated kinase in nobiletin-induced melanogenesis in murine B16/F10 melanoma cells. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2007;71:1781–1784. doi: 10.1271/bbb.70088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang JY, Koo JH, Song YG, Kwon KB, Lee JH, Sohn HS, Park BH, Jhee EC, Park JW. Stimulation of melanogenesis by scoparone in B16 melanoma cells. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2006;27:1467–1473. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2006.00435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paul S, Mizuno CS, Lee HJ, Zheng X, Chajkowisk S, Rimoldi JM, Conney A, Suh N, Rimando AM. In vitro and in vivo studies on stilbene analogs as potential treatment agents for colon cancer. Eur J Med Chem. 2010;45:3702–3708. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Lorgeril M, Salen P, Paillard F, Laporte F, Boucher F, de Leiris J. Mediterranean diet and the French paradox: two distinct biogeographic concepts for one consolidated scientific theory on the role of nutrition in coronary heart disease. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;54:503–515. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(01)00545-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Renaud S, de Lorgeril M. Wine, alcohol, platelets, and the French paradox for coronary heart disease. Lancet. 1992;339:1523–1526. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91277-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCormack D, McFadden D. A review of pterostilbene antioxidant activity and disease modification. Oxid Med Cell Longevity. 2013;2013:575482. doi: 10.1155/2013/575482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan MH, Chang YH, Tsai ML, Lai CS, Ho SY, Badmaev V, Ho CT. Pterostilbene suppressed lipopolysaccharide-induced up-expression of iNOS and COX-2 in murine macrophages. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:7502–7509. doi: 10.1021/jf800820y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paul S, Rimando AM, Lee HJ, Ji Y, Reddy BS, Suh N. Anti-inflammatory action of pterostilbene is mediated through the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in colon cancer cells. Cancer Prev Res. 2009;2:650–657. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rimando AM, Cuendet M, Desmarchelier C, Mehta RG, Pezzuto JM, Duke SO. Cancer chemopreventive and anti-oxidant activities of pterostilbene, a naturally occurring analogue of resveratrol. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:3453–3457. doi: 10.1021/jf0116855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joseph JA, Fisher DR, Cheng V, Rimando AM, Shukitt-Hale B. Cellular and behavioral effects of stilbene resveratrol analogues: implications for reducing the deleterious effects of aging. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:10544–10551. doi: 10.1021/jf802279h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bader Y, Madlener S, Strasser S, Maier S, Saiko P, Stark N, Popescu R, Huber D, Gollinger M, Erker T, Handler N, Szakmary A, Jäger W, Kopp B, Tentes I, Fritzer-Szekeres M, Krupitza G, Szekeres T. Stilbene analogues affect cell cycle progression and apoptosis independently of each other in an MCF-7 array of clones with distinct genetic and chemoresistant backgrounds. Oncol Rep. 2008;19:801–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cardile V, Chillemi R, Lombardo L, Sciuto S, Spatafora C, Tringali C. Antiproliferative activity of methylated analogues of E- and Z-resveratrol. Z Naturforsch C. 2007;62:189–195. doi: 10.1515/znc-2007-3-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pan MH, Gao JH, Lai CS, Wang YJ, Chen WM, Lo CY, Wang M, Dushenkov S, Ho CT. Antitumor activity of 3,5,4′-trimethoxystilbene in COLO 205 cells and xenografts in SCID mice. Mol Carcinog. 2008;47:184–196. doi: 10.1002/mc.20352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simoni D, Roberti M, Invidiata FP, Aiello E, Aiello S, Marchetti P, Baruchello R, Eleopra M, Di Cristina A, Grimaudo S, Gebbia N, Crosta L, Dieli F, Tolomeo M. Stilbene-based anticancer agents: resveratrol analogues active toward HL60 leukemic cells with a non-specific phase mechanism. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16:3245–3248. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang TT, Schoene NW, Kim YS, Mizuno CS, Rimando AM. Differential effects of resveratrol and its naturally occurring methylether analogs on cell cycle and apoptosis in human androgen-responsive LNCaP cancer cells. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2010;54:335–344. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200900143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weng CJ, Wu CF, Huang HW, Wu CH, Ho CT, Yen GC. Evaluation of anti-invasion effect of resveratrol and related methoxy analogues on human hepatocarcinoma cells. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:2886–2894. doi: 10.1021/jf904182y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoo KM, Kim S, Moon BK, Kim SS, Kim KT, Kim SY, Choi SY. Potent inhibitory effects of resveratrol derivatives on progression of prostate cancer cells. Arch Pharm. 2006;339:238–241. doi: 10.1002/ardp.200500228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim YM, Yun J, Lee CK, Lee H, Min KR, Kim Y. Oxyresveratrol and hydroxystilbene compounds: inhibitory effect on tyrosinase and mechanism of action. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:16340–16344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200678200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoashi T, Watabe H, Muller J, Yamaguchi Y, Vieira WD, Hearing VJ. MART-1 is required for the function of the melanosomal matrix protein PMEL17/GP100 and the maturation of melanosomes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:14006–14016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413692200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alesiani D, Cicconi R, Mattei M, Bei R, Canini A. Inhibition of Mek 1/2 kinase activity and stimulation of melanogenesis by 5,7-dimethoxycoumarin treatment of melanoma cells. Int J Oncol. 2009;34:1727–1735. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumagai A, Horike N, Satoh Y, Uebi T, Sasaki T, Itoh Y, Hirata Y, Uchio-Yamada K, Kitagawa K, Uesato S, Kawahara H, Takemori H, Nagaoka Y. A potent inhibitor of SIK2, 3,3′,7-trihydroxy-4′-methoxyflavon (4′-O-methylfisetin), promotes melanogenesis in B16F10 melanoma cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]