Abstract

The finding that bone marrow hosts several types of multipotent stem cell has prompted extensive research aimed at regenerating organs and building models to elucidate the mechanisms of diseases. Conventional research depends on the use of two-dimensional (2D) bone marrow systems, which imposes several obstacles. The development of 3D bone marrow systems with appropriate molecules and materials however, is now showing promising results. In this review, we discuss the advantages of 3D bone marrow systems over 2D systems and then point out various factors that can enhance the 3D systems. The intensive research on 3D bone marrow systems has revealed multiple important clinical applications including disease modeling, drug screening, regenerative medicine, etc. We also discuss some possible future directions in the 3D bone marrow research field.

Keywords: Three dimension, scaffold, bone marrow, stem cell, computational model, disease modeling, regenerative medicine

Introduction

The bone/bone marrow (B/BM) organ hosts several types of cells, including hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMMSCs), and their progenies. The HSCs can give rise to erythrocytes, leukocytes, and platelets, while the BMMSCs are able to differentiate into osteoblasts, chondroblasts, fibroblasts, endothelia, and adipocytes.1,2 HSCs mainly reside within the BM, whereas mesenchymal stem cells similar to BMMSCs, including adipose-derived mesenchymal cells (AMSCs), can be found in connective tissues outside the B/BM.3

The HSCs and BMMSCs play important roles in processes such as hematopoiesis and bone formation/remodeling. Microenvironments in the B/BM, called niches, temporospatially regulate the behaviors of these specialized stem cells, including self-renewal, proliferation, migration, and differentiation.4 Complex cell–cell interactions are important components of B/BM niches. For instance, studies show that BMMSCs help establish the hematopoietic niche and maintain HSCs in the B/BM by secreting ligands for chemokine receptors, cell adhesion molecules (CAMs), extracellular matrix (ECM), and their associated integrin receptors.4–8 In addition, a variety of soluble factors, e.g. bone morphogenetic proteins,9,10 Wnt,11 growth factors,12,13 and interleukins14 are involved in niche activities. Physical conditions such as mechanical or sheer forces and oxygen gradient also modulate the behaviors of these stem cells.15–18

The delicate balance in niches is maintained by complicated cross-talk between stem cells, ECM components, soluble factors, and physical properties of the microenvironment. Consequently, severe disturbances of B/BM functions that fail to be amended by the B/BM are associated with various disease processes; for instance, osteoarthritis,19 BM failure syndromes,20 multiple myeloma,21 and acute myeloid leukemia.22 In addition, B/BM functions can be compromised due to excessive radiation,23,24 drug toxicity,25–27 and traumatic accidents. The multipotencies of HSCs, MSCs, and very small embryonic-like cells28 and various disease processes associated with B/BM are intriguing and have led numerous researchers to investigate the B/BM and the stem cells within it, with the aim of using HSCs and MSCs to regenerate functional organs and to use the B/BM as a model to elucidate the mechanisms of diseases.

Two main obstacles currently limit regenerative research with stem cells from the B/BM. First, HSCs and BMMSCs occur at low frequency among the cells in the B/BM29 so in vitro expansions of HSCs and BMMSCs are often needed. However, conventional two-dimensional (2D) in vitro sub-culturing of HSCs and BMMSCs are associated with a reduction in the ability of BMMSCs to proliferate and differentiate.29 Second, in vitro 2D culturing of stem cells does not allow the extensive cell–cell, cell–ECM, or cell–physical environment cross-talk that occurs in vivo. This increases the difficulty of creating an in vitro functional B/BM resembling its authentic organ that is suitable for basic research and clinical application purposes.

Research projects looking into the behaviors of the B/BM system under pathological conditions (e.g. acute myeloid leukemia,30 myeloma,21 and BM metastasis of breast cancer31 and the construction of diseases models for drug screening are often conducted either with in vivo animal models32 or with in vitro human B/BM stem cell lines.33 Animal models allow for analysis of the in vivo interactions between key elements; however, the results from animal studies cannot always be translated to humans. On the other hand, in vitro studies of human B/BM stem cell lines in petri dishes fail to recreate microenvironments resembling those of the in vivo niches, making some of the results less applicable to in vivo systems. Hence, the limitations imposed by conventional animal models and culturing of B/BM stem cell lines in petri dishes restrict our investigations aimed at furthering the understanding of disease processes and hinder the development of high throughput drug screening protocols.34

Recent developments including 3D printing techniques, biocompatible and biodegradable materials, together with a deeper understanding of the importance of complex dialogues between different components of B/BM, are now fueling the emergence of 3D artificial BM. A 3D BM system induced by biologically modified degradable carrier scaffolds (made of natural or synthetic biocompatible and biodegradable materials) is composed of de novo generated hematopoietic stromal cells, associated growth factors/ECM proteins, and calcified bones. The ability to establish microenvironments resembling specific niches in authentic B/BM using 3D bioengineered scaffolds provides solutions to the various limitations associated with conventionally cultured B/BM mentioned above.

The purpose of this review is to discuss the advantages of the use of 3D BM systems over 2D systems, to provide a brief survey of various factors influencing the functions and efficacies of 3D systems and current applications, and to propose possible future directions.

Why 3D over 2D?

Morphology

Conventionally, cells are grown in 2D culture systems that put geometrical and mechanical constraints upon the cells and interfere with cell morphology.35 Research indicates that cell morphology has a strong influence on cell fate. For example, if a strain is placed along the axis of cell elongation, mesenchymal stem cells undergo proliferation. However, a strain placed perpendicular to the axis exerts no such proliferation.36,37 Some research also links morphology to differentiation and gene expression.38,39 Therefore, cell behaviors could be altered drastically in 2D culture, compared to in vivo behaviors. This emphasizes the need for well-developed 3D culture system that mimics in vivo cell–cell and cell–ECM interactions in order to develop a thorough understanding of how BM works and interacts with its surroundings.

Cell–cell interaction

Cell–cell interactions in 3D culture mimic the real BM interactions. Hematopoiesis, as an example, originates within the BM and is a dynamic process that creates all blood cellular components. In the BM microenvironment, fibroblasts and their products regulate hematopoiesis by interacting with hematopoietic cells.39 Cukierman et al. discovered that fibroblasts have higher motility and divide more rapidly in 3D than in 2D culture conditions. The asymmetric shape that fibroblasts acquire in 3D culture represents the shape seen in actual BM.33 In contrast, the mechanical constraint imposed by a 2D system causes the anchoring receptors to redistribute from the dorsal to ventral surfaces in adherent cells, creating an imbalance that deviates from the real tissue.40

BM niche

An important component in the process of life-long blood generation is the presence of long-term repopulating HSCs (LT-HSCs) that undergo unlimited cycles of self-renewal. One problem encountered with in vitro experiments is the maintenance of this LT-HSC self-renewal ability.15 Previously studies using 2D systems showed that even the addition of facilitating factors, such as stem cell factor (SCF) and thrombopoietin (TPO), was still not sufficient to maintain the unlimited self-renewal ability of LT-HSCs.41 Much research indicates that the 3D BM model recreates a niche that resembles in vivo interactions. For example, Reagan et al. discovered that 3D myeloma BM mimics cell–cell interactions and cell–ECM interactions. Beyond this, a 3D model could be used as a clinical tool to inspect skeletal cancer biology and osteogenesis.42

Optimizing 3D BM systems

Molecules

Multiple molecules are involved in regulation of BM niches. Different molecules promote proliferation or specific differentiation into different lineages. The molecules and their functions are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Essential molecules that regulate bone marrow niches

| Molecules | Actions | References |

|---|---|---|

| Angiopoietin (ANG) | Maintains HSC non-proliferation state | Arai et al.43 |

| Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) | Induces bone and cartilage formation; support growth and differentiation of HSC | An et al.9 |

| Yamaguchi et al.44 | ||

| Ogawa et al.45 | ||

| Torisawa et al.46 | ||

| Chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12), also called stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1) | Maintains HSC by binding to CXCR4 on HSC | Sugiyama et al.6 |

| Nagasawa et al.7 | ||

| Epidermal growth factor (EGF) | Increases cell counts | Quan et al.47 |

| Epinephrine and norepinephrine (EPI and NE) | Promotes migration, proliferation, and mobilization of CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors by activating β2-ARs | Méndez-Ferrer et al.48 |

| Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) | Maintains MSC self-renewal | Di Maggio et al.49 |

| Growth and differentiation factor 5 (GDF5) | Promotes intervertebral disc (IVD) phenotype. | Bucher et al.50 |

| Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1) | Facilitate cell homing via cell–cell interaction | Mercier et al.51 |

| Jagged1 (JAG-1) | Augments HSC cell counts by activating Notch1 signaling pathway | Stier et al.52 |

| Osteopontin (OPN) | Regulates HSC proliferation | Stier et al.52 |

| Parathyroid hormone (PTH) | Increases HSC cells counts by mediating proliferation | Calvi et al.53 |

| Steel factor (SF), also called stem cell factor (SCF) | Regulates HSC self-renewal | Kent et al.54 |

| Thrombopoietin (TPO) | Maintains HSC proliferation | Yoshihara et al.55 |

| Vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM1) | Facilitate cell homing via cell–cell interaction | Mercier et al.51 |

| Wnt | Regulates HSC self-renewal | Kim et al.56 |

| Schreck et al.57 |

Scaffolds

Scaffolds are often used by scientists to study BM and bone or cartilage tissue engineering in a 3D system due to multiple benefits of the 3D system in supporting proliferation and differentiation, as discussed above. Multiple factors, such as scaffold composition, influence the direction of differentiation of MSC.58 Porous scaffolds of varying pore sizes are good candidates for osteogenic differentiation.59 Hydroxyapatite (HA) has also been investigated as an adjuvant as the bone matrix contains a mineral analog to HA. HA inclusion in scaffolds supports stem cell adherence, ECM production, and differentiation.60,61

A good scaffold should create a supporting environment for stem cell proliferation and differentiation, leading to tissue regeneration. The properties of scaffolds, such as pore size and rigidness, also need to be considered.62,63 Adjuvants can be added to maximize the facilitation process of cell attachment and growth. Currently, most scaffold use focuses on creation of an environment that resembles the BM matrix.64 Various types of materials show promising results. These materials and their related features are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Features of different materials that are used for the fabrication of 3D scaffolds

| Material | Adjuvants | Ex vivo/In vivo | Stem cell types | Co-culture | Properties | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bioresorbable elastomeric polyurethane (PU) scaffolds | Hydroxyapatite (HA) | Ex vivo | MSC | Endothelial progenitor cells (EPC) | Volume: 9 mm3 (1 × 3 × 3 mm) Pore size: 200–630 µm | Duttenhoefer et al.65 |

| Chondrogenic fibrin hydrogel | HA HA–methacrylic anhydride (HA–MA) | Ex vivo | Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMMSCs) | Not reported | Sheet-like morphology Pore size: 10–100 µm | Snyder et al.66 |

| Fibroin protein/ chitosan scaffolds | Not reported | Ex vivo | BMMSC | Not reported | Not reported | Deng et al.67 |

| Inverted colloidal crystal (ICC) scaffolds | Not reported | Ex vivo | HSCs | CD34+ | 110 µm | Nichols et al.68 |

| Macroporous collagen scaffolds | Not reported | Ex vivo | Human cord blood CD34+ cells | Murine S1/S1 stromal cells | Pore size: 50–200 µm | Noll et al.69 |

| mPEG–PCL–mPEG (PCL) scaffolds | HA | Ex vivo | Porcine bone marrow stem cells (PBMMSCs) | Not reported | Pore size: 100 µm | Liao et al.70 |

| Nonwoven polyethylene terephthalate (PET) fabric | Not reported | Ex vivo | Human cord blood CD34+ cells | Not reported | Pore size: 10–60 µm | Li et al.71 |

| Photopolymerizable gelatin methacrylate (GelMA) hydrogel | Not reported | Ex vivo | BMMSC | Blood-derived endothelial colony-forming cells (ECFCs) | 49.7 ± 11.8 µm for 1 mol/L gelMA; 30.13 ± 6.12 µm for 5 mol/L gelMA; 23.6 ± 5.85 µm for 10 mol/L GelMA | Chen et al.72 |

| Plasma-medium gel | Fragmin/protamine nanoparticles and FGF-2 | Ex vivo | BMMSC; adipose tissue-derived multilineage stromal cells (ASCs) | Not reported | Not reported | Kishimoto et al.73 |

| Poly glycolic acid (PGA) and collagen scaffolds | Not reported | Ex vivo | Rat MSC | Not reported | Pore size: 8.0 ± 2.0 µm | Hosseinkhani et al.74 |

| Poly(ɛ-caprolactone) (PCL) scaffold | Not reported | Ex vivo | MSCs | Not reported | Pore size: 330 × 260 × 100 µm | Ousema et al.75 |

| Polyelectrolytes chitosan (CHT)/chondroitin sulfate (CS) multi-layered hierarchical scaffolds | Not reported | Ex vivo | BMMSC | Bovine chondrocytes (BCH) | Diameter size: 2 mm | Silva et al.76 |

| Polyester nonwoven disc carriers (fibra-cel) | Not reported | Ex vivo | Mouse bone marrow cells | Not reported | Pore size: 500 µm | Tomimori et al.77 |

| Porous cellulose microspheres | Not reported | Ex vivo | Bone marrow mononuclear cell | Not reported | Pore size: 300 µm | Mantalarisa et al.78 |

| PuraMatrix (BD Biosciences) peptide hydrogel | Not reported | Ex vivo | MSC | Not reported | Pore size: 50–200 nm | Chen et al.79 |

| Silk scaffolds in dexamethasone-free osteogenic media | Not reported | Ex vivo | MSC | GFP+ human multiple myeloma cell line (MM1S); endothelial co-culture | Pore size: 500–600 µm | Reagan et al.80 |

| 3D collagen scaffolds | Not reported | Ex vivo | BMMSC | Not reported | Pore size: 25 × 25 × 6 mm | Haneef et al.81 |

Computational modeling

Complex interactions occur between the stem cells, the growth factors, and the physical environment in the B/BM, so changes in these independent variables can significantly alter the behaviors of the B/BM—the dependent variables.82 Although the 3D architecture of the BM tissue in situ remains largely uncharacterized,83–86 quantitative analysis of the interactions between these independent and dependent variables using computational modeling can aid in determining which components are more important for the specific functions of the in vivo B/BM system under normal or pathological conditions.87–89 This in-depth understanding can guide the design of 3D de novo micro BM and advance investigations into disease processes using the 3D BM disease models.

Silva et al. developed a spatially-definite in silico model of the BM by employing TSim software and algorithm implementation.87 This hematopoietic simulation model provides a geometric and compartmental view of the distribution, replication, differentiation, and mobilization/migration of hematopoietic cells within 3D BM. The spatial restriction of bone may prevent exponential growth and the production of blood cells within the BM, but the fractal-like structure of the trabeculae and sinuses in the BM compensated for and overcome this restriction, leading to production of a large quantity of blood cells daily upon demand.

They modeled the fine architecture of the spatial BM with an emphasis on sinusoids—a network of vessels through which mature blood cells leave the BM.87 They used this model to simulate the replication, migration, and differentiation of HSCs and the exit of mature blood cells through the sinusoids. The behaviors of the model were assessed by measuring the percentages of HSCs, immature cells of granulocyte, erythrocyte, or platelet lineages, and mature cells of the three lineages. Data obtained by simulations were consistent with those obtained from asymptomatic patients under physiological conditions or after radiation. Their study shows that the fine architecture of the sinusoids in the B/BM is important for hematopoiesis and that maximization of hematopoiesis can be achieved by modulation of sinusoidal structures.

Colijn and Mackey modeled the dynamics in periodic chronic myelogenous leukemia (PCML) by regulating parameters such as the rate of differentiation into the leukocyte lineage.88 Their results indicate that changes in this rate of differentiation, as well as in the rate of leukocyte amplification and the rate of HCS apoptosis, are required to generate a PCML phenotype.

Current applications

Disease modeling and drug screening

The 3D BM system is a useful tool for modeling various diseases. The use of a 3D BM system together with recently developed microfluid46,90 or perfusion15 culture technologies can help in the development of ex vivo models of various diseases that provide accurate portraits of in vivo interactions in the niche and predict in vivo responses to different treatments. Several current studies on modeling of various diseases using 3D BM system are described below.

Aljitawi et al. created a scaffold of BMMSCs co-cultured with leukemia cells.34 Not only does this 3D system mimic the structure, it also offers the supporting microenvironment required by the leukemia cells. In this 3D system, leukemia cells are more chemo-resistant and proliferative due to this supporting niche. The cells in this 3D system also shows distinctive physiological features not seen when they are cultured in a petri dish (2D). For example, leukemia cells cultured in a 2D system undergo a short proliferation stage followed by inhibition.34,91 Cells grown in a 3D system do not show this deviation in proliferation.34

Ferrarini et al. used a 3D model to study multiple myeloma cell growth. They noted good preservation of myeloma cells in the supporting niche, complete with the development of bone lamellae and blood vessels, thereby achieving optimal nutritional support. They also screened the toxicity of the drug Bortezomib on myeloma cells. Importantly, the Bortezomib treatments in the 3D model showed a promising response consistent with that observed in vivo. Overall, the research indicates that 3D models are good tools for the study of multiple myeloma and for investigation of pre-clinical treatments.21

Mukhopadhyay et al. used 3D cultures of macrophages, derived from BM to study epithelioid granuloma, an inflammatory disease caused by macrophage accumulation as an inflammatory response.92 The addition of carbon nanomaterial to cells cultured in the 3D system was positively correlated with the induction of multinucleated epithelioid granulomas by asbestos fibers or multiwalled carbon nanotubes. This 3D system can serve as a tool to evaluate the potential risk of some engineered nanomaterials in inducing granulomas in lungs or mesothelium.93

Osteoarthritis is a degenerative disease of bone and cartilage.94 Over the years, scientists have used MSCs as the main material for the constructs used to study osteoarthritis because of their ability to differentiate into osteocytes and chondrocytes.95,96 Similar to some scaffolds described in Table 2, HA is often used in bone constructs.97 Chitosan with TGF-β3 is used in cartilage constructs.98 A study by Snyder et al. discussed the application of 3D systems in cartilage repair. The 3D system is composed of BMMSCs incubated in a hydrogel fabricated from fibrin/hyaluronic acid and methacrylic anhydride. The system shows induced BMMSC proliferation, early chondrogenesis, and increased mechanical strength, thereby supporting its application in the delivery of BMMSCs for potential repair of injured cartilage.66

Stem cell expansion

One barrier in much of the current BM research is the limited number of stem and nucleated cells in the BM. Therefore, expanding their number is desirable. A 2D system imposes multiple barriers to this expansion, such as reduction in clonogenicity and differentiation capacity; thereby posing a challenge to physiological and pathological studies.99

Papadimitropoulos et al. demonstrated a promising 3D system using a porous scaffold. Unlike the case in a 2D system, the proliferated and differentiated cells in their 3D system maintain their progenitor properties with a 4.3 fold higher clonogenicity and a higher efficiency of differentiation. The multipotency-related gene clusters are significantly upregulated in the 3D system. Overall, the 3D system creates a supportive niche that allows the expansion of MSCs while maintaining their normal functionality; thereby creating a system that can be used pre-clinically or clinically in the field of regenerative medicine.29

Other research done by Sadat Hashemi et al. suggested that ex vivo expansion of HSCs is a possible way to increase umbilical cord blood CD34+ cells (UCB-CD34+), which are useful in BM transplantation. UCB-CD34+ cells were co-cultured in the 3D scaffolds, which mimic the BM microenvironment and supports stem cell differentiation and expansion, leading to a significant increase in UCB-CD34+ cell counts.100

Regeneration

Regenerative medicine is a field dedicated to the regeneration of damaged tissues or organs by the body’s own repair mechanisms or by implantation of in vitro grown tissues and organs. Stem cells are commonly used in this field due to their ability to differentiate into many types of tissue and proliferate without losing their differentiation ability. Many types of stem cells are used in numerous studies, but MSCs or BMMSCs have received the most attention. Recognition of the benefits of 3D models had led to more researches focused on incorporating MSCs or BMMSCs into 3D scaffolds to optimize the B/BM formation results. The following recent studies all exploited the benefits of 3D scaffold models.101

For years, researchers have used dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) in the hope of regaining tooth sensitivity and vitality after root canal therapy.102 However, the limitation is the availability of DPSCs. Recently, Ravindran et al. discovered that incorporating BMMSCs into 3D scaffolds could lead to odontogenic lineage differentiation into DPSCs both in vitro and in vivo, resulting in the formation of vascularized tissue resembling dental pulp. The 3D scaffold provides insights into possible applications of dental pulp regeneration.103

Tang et al. focused on large bone reconstruction in an animal model. Treatment with biodegradable polydioxanone (PDO) alone is not sufficient as a long-term treatment as the PDO material was completely degraded and substituted with fibrous tissue after 24 weeks. More promising results (better shape and radian) were obtained using a 3D scaffold of BMMSCs. This research indicates a possible platform for long bone repair research and clinical applications using 3D BMMSC scaffolds.104

Haneef et al. evaluated the proliferation and differentiation of BMMSCs into cardiomyocytes in a 3D collagen scaffold. The 3D system supported proliferation of more cells following electrostimulation. Immunocytochemistry confirmed the differentiation of BMMSCs into cardiomyocytes, as indicated by the presence of the cardiac markers troponin I, myosin, and desmin. This research points out that 3D scaffolds could be valuable in regeneration of cardiomyocytes from patients suffering from myocardial infarction.81

Perspective

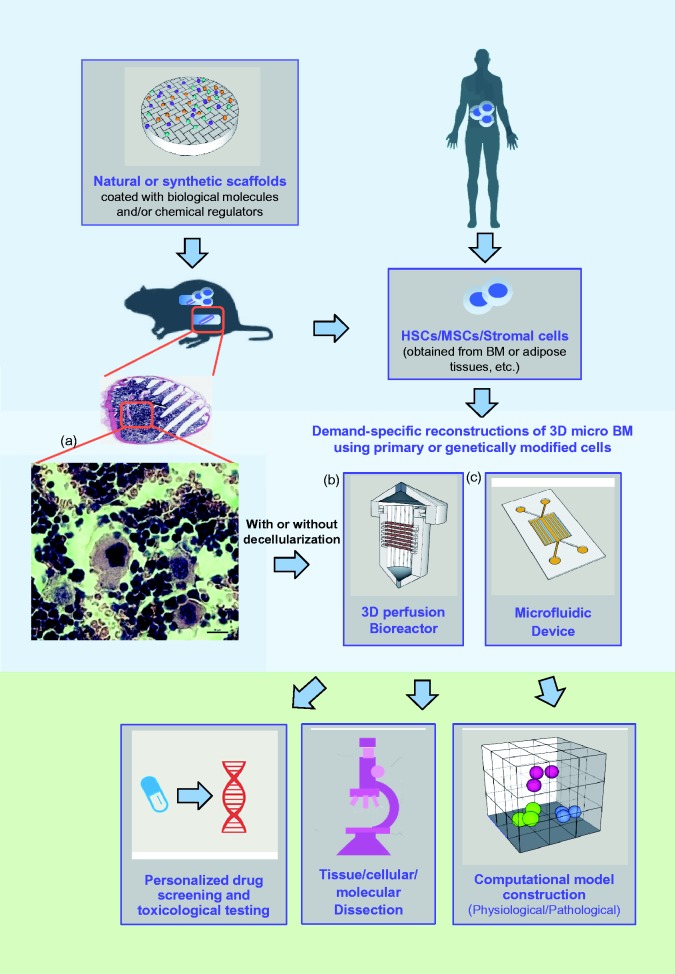

The development of functional de novo 3D B/BM in vitro has long been considered an important and challenging task. In adult mammals, BM is the only organ that is able to generate the full spectrum of hematopoiesis under normal conditions.105 This exceptional organ repairs itself in the same way that it originally forms in an embryo. The combination of in vivo, ectopic, de novo B/BM regeneration and in vitro bioengineering by utilizing a combination of chemical, biological, and molecular approaches will allow researchers to develop cost-effective and useful 3D B/BM.106 These manageable humanized 3D B/BM models will facilitate in-depth, dissectible, and integrated investigation into the temporospatial microenvironmental factors that regulate the fates of HSCs and MSCs. Stage- and lineage-specific niches will be established and identified by grafting specific types of stromal cells, including isogenic stromal cells, and by modifying these cells and their associated microenvironments with specific chemical and biological regulators (Figure 1). Human CD34+ as well as BMMSC cells will be appreciably expanded in ossicles containing human stromal cells, rather than animal stromal cells, because the human stromal cells may provide more compatible growth factors, interleukins, and CAMs than can be provided by mouse stromal cells. Bioengineered human stromal cells, such as paired isogenic gene knock-in and knock-out cells could be stably transduced with GFP, which will allow researchers to track them continuously in order to monitor their fate and geometrical contribution with time. With the help of 3D multiphoton microscopy, qRT-PCR and microarray techniques, researchers will be able to establish the tissue architecture, heterotypic cell–cell interactions, cell replication/differentiation, dedifferentiation/transdifferentiation,107,108 and differential gene expression profiles. The establishment of efficient and reproducible 3D B/BM culture and stem cell expansion protocols suitable for industry and automated high throughput platforms will enable the development of time-saving strategies for clinical applications. The outcomes of these efforts and studies will provide useful and important information for carrying out microenvironmental and HSC research to develop experimental approaches that more realistically create 3D B/BM systems. In addition, this research will increase the understanding of the sophisticated cellular and molecular mechanisms that govern the microenvironmental regulation of hematopoiesis and de novo tissue regeneration.

Figure 1.

A cartoon representation of a bioengineered 3D micro bone marrow system and its applications. a,106; b, Biotek; c,46

The low frequency of BMMSCs motivates the use of stem cells from other sources. For example, adipose mesenchymal stem cells are promising due to their large quantities and the procedure for obtaining adipose MSCs is relatively noninvasive and causes little discomfort.73,109 In addition, the in vivo microenvironment can be optimally mimicked by incorporating, co-culture into research projects. Co-culture techniques play an important role in enabling complex cell–cell interaction, allowing better elucidation of in vivo activities. Furthermore, co-culture technique can create a platform for clinical applications in regenerative medicine. In vitro perfusion can also substitute for static media in order to mimic the dynamic microenvironment in vivo.

Concluding remarks

Much evidence indicates that 3D BM models have multiple advantages over 2D systems. Different 3D scaffold materials and molecules can be used to achieve different functionalities by optimizing microenvironments for specific stem cell sources. 3D models offer insightful platforms for researchers and clinicians in multiple fields, including disease modeling, drug screening, regenerative medicine, etc. The goal of further research should be the optimization of 3D scaffold efficacy by modulating cellular and molecular components and properties.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by grants from the Hill Collaboration, the Carol M. Baldwin Breast Cancer Research Fund, the Connolly Endowment/Hendricks Fund, and the LUNGevity Foundation.

Author contributions

All authors participated in writing and reviewing the manuscript.

References

- 1.Sacchetti B, Funari A, Michienzi S, Di Cesare S, Piersanti S, Saggio I, Tagliafico E, Ferrari S, Robey PG, Riminucci M, Bianco P. Self-renewing osteoprogenitors in bone marrow sinusoids can organize a hematopoietic microenvironment. Cell 2007; 131: 324–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miura Y, Yoshioka S, Yao H, Takaori-Kondo A, Maekawa T, Ichinohe T. Chimerism of bone marrow mesenchymal stem/stromal cells in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: is it clinically relevant? Chimerism 2013; 4: 78–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mesimäki K, Lindroos B, Törnwall J, Mauno J, Lindqvist C, Kontio R, Miettinen S, Suuronen R. Novel maxillary reconstruction with ectopic bone formation by GMP adipose stem cells. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2009; 38: 201–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Méndez-Ferrer S, Michurina TV, Ferraro F, Mazloom AR, MacArthur BD, Lira SA, Scadden DT, Ma’ayan A, Enikolopov GN, Frenette PS. Mesenchymal and haematopoietic stem cells form a unique bone marrow niche. Nature 2010; 466: 829–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Isern J, García-García A, Martín AM, Arranz L, Martín-Pérez D, Torroja C, Sánchez-Cabo F, Méndez-Ferrer S. The neural crest is a source of mesenchymal stem cells with specialized hematopoietic stem cell niche function. eLife 2014; 3: e03696–e03696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sugiyama T, Kohara H, Noda M, Nagasawa T. Maintenance of the hematopoietic stem cell pool by CXCL12-CXCR4 chemokine signaling in bone marrow stromal cell niches. Immunity 2006; 25: 977–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagasawa T, Hirota S, Tachibana K, Kitamura Y, Yoshida N, Kikutani H, Kishimoto T. Defects of B-cell lymphopoiesis and bone-marrow myelopoiesis in mice lacking the CXC chemokine PBSF/SDF-1. Nature 1996; 382: 635–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishihara J, Umemoto T, Yamato M, Shiratsuchi Y, Takaki S, Petrich BG, Nakauchi H, Eto K, Kitamura T, Okano T. Nov/CCN3 regulates long-term repopulating activity of murine hematopoietic stem cells via integrin αvβ3. Int J Hematol 2014; 99: 393–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.An J, Rosen V, Cox K, Beauchemin N, Sullivan AK. Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 induces a hematopoietic microenvironment in the rat that supports the growth of stem cells. Exp Hemat 1996; 24: 768–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldman DC, Bailey AS, Pfaffle DL, Al Masri A, Christian JL, Fleming WH. BMP4 regulates the hematopoietic stem cell niche. Blood 2009; 114: 4393–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schreck C, Bock F, Grziwok S, Oostendorp RAJ, Istvánffy R. Regulation of hematopoiesis by activators and inhibitors of Wnt signaling from the niche: regulation of hematopoiesis by activators and inhibitors. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2014; 1310: 32–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas D, Vadas M, Lopez A. Regulation of haematopoiesis by growth factors – emerging insights and therapies. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2004; 4: 869–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lataillade JJ, Pierre-Louis O, Hasselbalch HC, Uzan G, Jasmin C, Martyré MC, Le Bousse-Kerdilès MC. Does primary myelofibrosis involve a defective stem cell niche? From concept to evidence. Blood 2008; 112: 3026–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schürch CM, Riether C, Ochsenbein AF. Cytotoxic CD8+ T cells stimulate hematopoietic progenitors by promoting cytokine release from bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells. Cell Stem Cell 2014; 14: 460–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Maggio N, Piccinini E, Jaworski M, Trumpp A, Wendt DJ, Martin I. Toward modeling the bone marrow niche using scaffold-based 3D culture systems. Biomaterials 2011; 32: 321–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berniakovich I, Giorgio M. Low oxygen tension maintains multipotency, whereas normoxia increases differentiation of mouse bone marrow stromal cells. Int J Mol Sci 2013; 14: 2119–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Durant TJS, Dyment N, McCarthy MBR, Cote MP, Arciero RA, Mazzocca AD, Rowe D. Mesenchymal stem cell response to growth factor treatment and low oxygen tension in 3-dimensional construct environment. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J 2014; 4: 46–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ribeiro AJ, Tottey S, Taylor RW, Bise R, Kanade T, Badylak SF, Dahl KN. Mechanical characterization of adult stem cells from bone marrow and perivascular niches. J Biomech 2012; 45: 1280–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muraoka T, Hagino H, Okano T, Enokida M, Teshima R. Role of subchondral bone in osteoarthritis development: a comparative study of two strains of guinea pigs with and without spontaneously occurring osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2007; 56: 3366–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kastrinaki MC, Pavlaki K, Batsali AK, Kouvidi E, Mavroudi I, Pontikoglou C, Papadaki HA. Mesenchymal stem cells in immune-mediated bone marrow failure syndromes. Clin Dev Immunol 2013; 2013: 265608–265608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrarini M, Steimberg N, Ponzoni M, Belloni D, Berenzi A, Girlanda S, Caligaris-Cappio F, Mazzoleni G, Ferrero E. Ex-vivo dynamic 3-D culture of human tissues in the RCCSTM bioreactor allows the study of multiple myeloma biology and response to therapy. PLoS ONE 2013; 8: e71613–e71613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishikawa F, Yoshida S, Saito Y, Hijikata A, Kitamura H, Tanaka S, Nakamura R, Tanaka T, Tomiyama H, Saito N, Fukata M, Miyamoto T, Lyons B, Ohshima K, Uchida N, Taniguchi S, Ohara O, Akashi K, Harada M, Shultz LD. Chemotherapy-resistant human AML stem cells home to and engraft within the bone-marrow endosteal region. Nature Biotechnol 2007; 25: 1315–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meng A, Wang Y, Van Zant G, Zhou D. Ionizing radiation and busulfan induce premature senescence in murine bone marrow hematopoietic cells. Cancer Res 2003; 63: 5414–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carbonneau CL, Despars G, Rojas-Sutterlin S, Fortin A, Le O, Hoang T, Beausejour CM. Ionizing radiation-induced expression of INK4a/ARF in murine bone marrow-derived stromal cell populations interferes with bone marrow homeostasis. Blood 2012; 119: 717–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Papież MA. The effect of quercetin on oxidative DNA damage and myelosuppression induced by etoposide in bone marrow cells of rats. Acta Biochim Pol 2014; 61: 7–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li J, Zhang N, Huang X, Xu J, Fernandes JC, Dai K, Zhang X. Dexamethasone shifts bone marrow stromal cells from osteoblasts to adipocytes by C/EBPalpha promoter methylation. Cell Death Dis 2013; 4: e832–e832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Das B, Antoon R, Tsuchida R, Lotfi S, Morozova O, Farhat W, Malkin D, Koren G, Yeger H, Baruchel S. Squalene selectively protects mouse bone marrow progenitors against cisplatin and carboplatin-induced cytotoxicity in vivo without protecting tumor growth. Neoplasia 2008; 10: 1105–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kassmer SH, Krause DS. Very small embryonic-like cells: biology and function of these potential endogenous pluripotent stem cells in adult tissues. Mol Reprod Dev 2013; 80: 1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Papadimitropoulos A, Piccinini E, Brachat S, Braccini A, Wendt D, Barbero A, Jacobi C, Martin I. Expansion of human mesenchymal stromal cells from fresh bone marrow in a 3D scaffold-based system under direct perfusion. PLoS ONE 2014; 9: e102359–e102359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schuurhuis GJ, Meel MH, Wouters F, Min LA, Terwijn M, de Jonge NA, Kelder A, Snel AN, Zweegman S, Ossenkoppele GJ, Smit L. Normal hematopoietic stem cells within the AML bone marrow have a distinct and higher ALDH activity level than co-existing leukemic stem cells. PLoS ONE 2013; 8: e78897–e78897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thibaudeau L, Taubenberger AV, Holzapfel BM, Quent VM, Fuehrmann T, Hesami P, Brown TD, Dalton PD, Power CA, Hollier BG. A tissue-engineered humanized xenograft model of human breast cancer metastasis to bone. Dis Model Mech 2014; 7: 299–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Erb U, Megaptche A, Gu X, Büchler MW, Zöller M. CD44 standard and CD44v10 isoform expression on leukemia cells distinctly influences niche embedding of hematopoietic stem cells. J Hematol Oncol 2014; 7: 29–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cukierman E, Pankov R, Stevens DR, Yamada KM. Taking cell-matrix adhesions to the third dimension. Science 2001; 294: 1708–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aljitawi OS, Li D, Xiao Y, Zhang D, Ramachandran K, Stehno-Bittel L, Van Veldhuizen P, Lin TL, Kambhampati S, Garimella R. A novel three-dimensional stromal-based model for in vitro chemotherapy sensitivity testing of leukemia cells. Leuk Lymphoma 2014; 55: 378–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thery M. Micropatterning as a tool to decipher cell morphogenesis and functions. J Cell Sci 2010; 123: 4201–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rossi MI, Barros AP, Baptista LS, Garzoni LR, Meirelles MN, Takiya CM, Pascarelli BM, Dutra HS, Borojevic R. Multicellular spheroids of bone marrow stromal cells: a three-dimensional in vitro culture system for the study of hematopoietic cell migration. Braz J Med Biol Res 2005; 38: 1455–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kurpinski K, Chu J, Hashi C, Li S. Anisotropic mechanosensing by mesenchymal stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006; 103: 16095–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thomas CH, Collier JH, Sfeir CS, Healy KE. Engineering gene expression and protein synthesis by modulation of nuclear shape. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002; 99: 1972–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rougier F, Dupuis F, Denizot Y. Human bone marrow fibroblasts–an overview of their characterization, proliferation and inflammatory mediator production. Hematol Cell Ther 1996; 38: 241–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beningo KA, Dembo M, Wang YL. Responses of fibroblasts to anchorage of dorsal extracellular matrix receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004; 101: 18024–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fraser CC, Eaves CJ, Szilvassy SJ, Humphries RK. Expansion in vitro of retrovirally marked totipotent hematopoietic stem cells. Blood 1990; 76: 1072–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reagan MR, Mishima Y, Glavey SV, Zhang Y, Manier S, Lu ZN, Memarzadeh M, Zhang Y, Sacco A, Aljawai Y, Shi J, Tai YT, Ready JE, Kaplan DL, Roccaro AM, Ghobrial IM. Investigating osteogenic differentiation in multiple myeloma using a novel 3D bone marrow niche model. Blood 2014; 124: 3250–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arai F, Hirao A, Ohmura M, Sato H, Matsuoka S, Takubo K, Ito K, Koh GY, Suda T. Tie2/angiopoietin-1 signaling regulates hematopoietic stem cell quiescence in the bone marrow niche. Cell 2004; 118: 149–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamaguchi A, Katagiri T, Ikeda T, Wozney JM, Rosen V, Wang EA, Kahn AJ, Suda T, Yoshiki S. Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 stimulates osteoblastic maturation and inhibits myogenic differentiation in vitro. J Cell Biol 1991; 113: 681–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ogawa Y, Schmidt DK, Nathan RM, Armstrong RM, Miller KL, Sawamura SJ, Ziman JM, Erickson KL, de Leon ER, Rosen DM. Bovine bone activin enhances bone morphogenetic protein-induced ectopic bone formation. J Biol Chem 1992; 267: 14233–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Torisawa Y, Spina SC, Mammoto T, Mammoto A, Weaver JC, Tat T, Collins JJ, Ingber DE. Bone marrow-on-a-chip replicates hematopoietic niche physiology in vitro. Nature Methods 2014; 11: 663–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Quan H, Kim SK, Heo SJ, Koak JY, Lee JH. Optimization of growth inducing factors for colony forming and attachment of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells regarding bioengineering application. J Adv Prosthodont 2014; 6: 379–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Méndez-Ferrer S, Battista M, Frenette PS. Cooperation of β2- and β3-adrenergic receptors in hematopoietic progenitor cell mobilization. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2010; 1192: 139–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Di Maggio N, Mehrkens A, Papadimitropoulos A, Schaeren S, Heberer M, Banfi A, Martin I. Fibroblast growth factor-2 maintains a niche-dependent population of self-renewing highly potent non-adherent mesenchymal progenitors through FGFR2c. Stem Cells Int 2012; 30: 1455–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bucher C, Gazdhar A, Benneker LM, Geiser T, Gantenbein-Ritter B. Nonviral gene delivery of growth and differentiation factor 5 to human mesenchymal stem cells injected into a 3D bovine intervertebral disc organ culture system. Stem Cells Int 2013; 2013: 326828–326828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mercier FE, Ragu C, Scadden DT. The bone marrow at the crossroads of blood and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2011; 12: 49–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stier S, Cheng T, Dombkowski D, Carlesso N, Scadden DT. Notch1 activation increases hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal in vivo and favors lymphoid over myeloid lineage outcome. Blood 2002; 99: 2369–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Calvi LM, Adams GB, Weibrecht KW, Weber JM, Olson DP, Knight MC, Martin RP, Schipani E, Divieti P, Bringhurst FR, Milner LA, Kronenberg HM, Scadden DT. Osteoblastic cells regulate the haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature 2003; 425: 841–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kent D, Copley M, Benz C, Dykstra B, Bowie M, Eaves C. Regulation of hematopoietic stem cells by the steel factor/KIT signaling pathway. Clin Cancer Res 2008; 14: 1926–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yoshihara H, Arai F, Hosokawa K, Hagiwara T, Takubo K, Nakamura Y, Gomei Y, Iwasaki H, Matsuoka S, Miyamoto K, Miyazaki H, Takahashi T, Suda T. Thrombopoietin/MPL signaling regulates hematopoietic stem cell quiescence and interaction with the osteoblastic niche. Cell Stem Cell 2007; 1: 685–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim JA, Kang YJ, Park G, Kim M, Park YO, Kim H, Leem SH, Chu IS, Lee JS, Jho EH, Oh IH. Identification of a stroma-mediated Wnt/beta-catenin signal promoting self-renewal of hematopoietic stem cells in the stem cell niche. Stem Cells Int 2009; 27: 1318–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schreck C, Bock F, Grziwok S, Oostendorp RA, Istvánffy R. Regulation of hematopoiesis by activators and inhibitors of Wnt signaling from the niche. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2014; 1310: 32–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huebsch N, Arany PR, Mao AS, Shvartsman D, Ali OA, Bencherif SA, Rivera-Feliciano J, Mooney DJ. Harnessing traction-mediated manipulation of the cell/matrix interface to control stem-cell fate. Nat Mater 2010; 9: 518–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Karageorgiou V, Kaplan D. Porosity of 3D biomaterial scaffolds and osteogenesis. Biomaterials 2005; 26: 5474–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Storrie H, Stupp SI. Cellular response to zinc-containing organoapatite: an in vitro study of proliferation, alkaline phosphatase activity and biomineralization. Biomaterials 2005; 26: 5492–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tortelli F, Cancedda R. Three-dimensional cultures of osteogenic and chondrogenic cells: a tissue engineering approach to mimic bone and cartilage in vitro. Eur Cell Mater 2009; 17: 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dalby MJ, Gadegaard N, Tare R, Andar A, Riehle MO, Herzyk P, Wilkinson CD, Oreffo RO. The control of human mesenchymal cell differentiation using nanoscale symmetry and disorder. Nat Mater 2007; 6: 997–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, Discher DE. Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell 2006; 126: 677–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang G. Biomimicry in biomedical research. Organogenesis 2012; 8: 101–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Duttenhoefer F, Lara de Freitas R, Meury T, Loibl M, Benneker LM, Richards RG, Alini M, Verrier S. 3D scaffolds co-seeded with human endothelial progenitor and mesenchymal stem cells: evidence of prevascularisation within 7 days. Eur Cell Mater 2013; 26: 49–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Snyder TN, Madhavan K, Intrator M, Dregalla RC, Park D. A fibrin/hyaluronic acid hydrogel for the delivery of mesenchymal stem cells and potential for articular cartilage repair. J Biol Eng 2014; 8: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Deng J, She RF, Huang WL, Yuan C, Mo G. Fibroin protein/chitosan scaffolds and bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells culture in vitro. Genet Mol Res 2014; 13: 5745–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nichols JE, Cortiella J, Lee J, Niles JA, Cuddihy M, Wang S, Bielitzki J, Cantu A, Mlcak R, Valdivia E, Yancy R, McClure ML, Kotov NA. In vitro analog of human bone marrow from 3D scaffolds with biomimetic inverted colloidal crystal geometry. Biomaterials 2009; 30: 1071–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Noll T, Jelinek N, Schmid S, Biselli M, Wandrey C. Cultivation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells: biochemical engineering aspects. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol 2002; 74: 111–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liao HT, Chen YY, Lai YT, Hsieh MF, Jiang CP. The osteogenesis of bone marrow stem cells on mPEG-PCL-mPEG/hydroxyapatite composite scaffold via solid freeform fabrication. Biomed Res Int 2014; 2014: 321549–321549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li Y, Ma T, Kniss DA, Yang ST, Lasky LC. Human cord cell hematopoiesis in three-dimensional nonwoven fibrous matrices: in vitro simulation of the marrow microenvironment. J Hematother Stem Cell Res 2001; 10: 355–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chen YC, Lin RZ, Qi H, Yang Y, Bae H, Melero-Martin JM, Khademhosseini A. Functional human vascular network generated in photocrosslinkable gelatin methacrylate hydrogels. Adv Funct Mater 2012; 22: 2027–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kishimoto S, Ishihara M, Mori Y, Takikawa M, Sumi Y, Nakamura S, Sato T, Kiyosawa T. Three-dimensional expansion using plasma-medium gel with fragmin/protamine nanoparticles and fgf-2 to stimulate adipose-derived stromal cells and bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Biores Open Access 2012; 1: 314–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hosseinkhani H, Hong PD, Yu DS, Chen YR, Ickowicz D, Farber IY, Domb AJ. Development of 3D in vitro platform technology to engineer mesenchymal stem cells. Int J Nanomed 2012; 7: 3035–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ousema PH, Moutos FT, Estes BT, Caplan AI, Lennon DP, Guilak F, Weinberg JB. The inhibition by interleukin 1 of MSC chondrogenesis and the development of biomechanical properties in biomimetic 3D woven PCL scaffolds. Biomaterials 2012; 33: 8967–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Silva JM, Georgi N, Costa R, Sher P, Reis RL, Van Blitterswijk CA, Karperien M, Mano JF. Nanostructured 3D constructs based on chitosan and chondroitin sulphate multilayers for cartilage tissue engineering. PLoS One 2013; 8: e55451–e55451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tomimori Y, Takagi M, Yoshida T. The construction of an in vitro three-dimensional hematopoietic microenvironment for mouse bone marrow cells employing porous carriers. Cytotechnology 2000; 34: 121–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mantalarisa A, Bourned P, Wu J. Production of human osteoclasts in a three-dimensional bone marrow culture system. Biochem Eng J 2004; 20: 189–96. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chen J, Shi ZD, Ji X, Morales J, Zhang J, Kaur N, Wang S. Enhanced osteogenesis of human mesenchymal stem cells by periodic heat shock in self-assembling peptide hydrogel. Tissue Eng Part A 2013; 19: 716–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Reagan MR, Seib FP, McMillin DW, Sage EK, Mitsiades CS, Janes SM, Ghobrial IM, Kaplan DL. Stem cell implants for cancer therapy: TRAIL-expressing mesenchymal stem cells target cancer cells in situ. J Breast Cancer 2012; 15: 273–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Haneef K, Lila N, Benadda S, Legrand F, Carpentier A, Chachques JC. Development of bioartificial myocardium by electrostimulation of 3D collagen scaffolds seeded with stem cells. Heart Int 2012; 7: e14–e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Adimy M, Crauste F. Mathematical model of hematopoiesis dynamics with growth factor-dependent apoptosis and proliferation regulations. Math Comput Model 42009; 9: 2128–37. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Albrektsson T, Albrektsson B. Microcirculation in grafted bone. A chamber technique for vital microscopy of rabbit bone transplants. Acta Orthop Scand 1978; 49: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Takaku T, Malide D, Chen J, Calado RT, Kajigaya S, Young NS. Hematopoiesis in 3 dimensions: human and murine bone marrow architecture visualized by confocal microscopy. Blood 2010; 116: e41–e55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Calvi LM, Adams GB, Weibrecht KW, Weber JM, Olson DP, Knight MC, Martin RP, Schipani E, Divieti P, Bringhurst FR, Milner LA, Kronenberg HM, Scadden DT. Osteoblastic cells regulate the haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature 2003; 425: 841–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bourke VA, Watchman CJ, Reith JD, Jorgensen ML, Dieudonne A, Bolch WE. Spatial gradients of blood vessels and hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells within the marrow cavities of the human skeleton. Blood 2009; 114: 4077–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Silva A, Anderson ARA, Gatenby R. A multiscale model of the bone marrow and hematopoiesis. Math Biosci Eng 2011; 8: 643–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Colijn C, Mackey MC. A mathematical model of hematopoiesis—I. Periodic chronic myelogenous leukemia. J Theor Biol 2005; 237: 117–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Vaughan TJ, Voisin M, Niebur GL, McNamara LM. Multiscale modeling of trabecular bone marrow: understanding the micromechanical environment of mesenchymal stem cells during osteoporosis. J Biomech Eng 2015; 137: 011003–011003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Heylman C, Sobrino A, Shirure VS, Hughes CC, George SC. A strategy for integrating essential three-dimensional microphysiological systems of human organs for realistic anticancer drug screening. Exp Biol Med 2014; 239: 1240–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Burke PJ, Diggs CH, Owens AHJ. Factors in human serum affecting the proliferation of normal and leukemic cells. Cancer Res 1973; 33: 800–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mukhopadhyay S, Farver CF, Vaszar LT, Dempsey OJ, Popper HH, Mani H, Capelozzi VL, Fukuoka J, Kerr KM, Zeren EH, Iyer VK, Tanaka T, Narde I, Nomikos A, Gumurdulu D, Arava S, Zander DS, Tazelaar HD. Causes of pulmonary granulomas: a retrospective study of 500 cases from seven countries. J Clin Pathol 2012; 65: 51–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sanchez VC, Weston P, Yan A, Hurt RH, Kane AB. A 3-dimensional in vitro model of epithelioid granulomas induced by high aspect ratio nanomaterials. Part Fibre Toxicol 2011; 8: 17–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hunter DJ, Felson DT. Osteoarthritis. BMJ 2006; 332: 639–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chen FH, Rousche KT, Tuan RS. Technology insight: adult stem cells in cartilage regeneration and tissue engineering. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol 2006; 2: 373–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kraus KH, Kirker-Head C. Mesenchymal stem cells and bone regeneration. Vet Surg 2006; 35: 232–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hillig WB, Choi Y, Murthy S, Natravali N, Ajayan P. An open-pored gelatin/ hydroxyapatite composite as a potential bone substitute. J Mater Sci Mater Med 2008; 19: 11–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yan LP, Wang YJ, Ren L, Wu G, Caridade SG, Fan JB, Wang LY, Ji PH, Oliveira JM, Oliveira JT, Mano JF, Reis RL. Genipin-cross-linked collagen/chitosan biomimetic scaffolds for articular cartilage tissue engineering applications. J Biomed Mater Res A 2010; 95: 465–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Banfi A, Muraglia A, Dozin B, Mastrogiacomo M, Cancedda R, Quarto R. Proliferation kinetics and differentiation potential of ex vivo expanded human bone marrow stromal cells: implications for their use in cell therapy. Exp Hematol 2000; 28: 707–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sadat Hashemi Z, Forouzandeh Moghadam M, Soleiman M. Comparison of the ex vivo expansion of UCB-derived CD34+ in 3D DBM/MBA scaffolds with USSC as a feeder layer. Iran J Basic Med Sci 2013; 16: 1075–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hipp J, Atala A. Sources of stem cells for regenerative medicine. Stem Cell Rev 2008; 4: 3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gronthos S, Brahim J, Li W, Fisher LW, Cherman N, Boyde A, DenBesten P, Robey PG, Shi S. Stem cell properties of human dental pulp stem cells. J Dent Res 2002; 81: 531–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ravindran S, Huang CC, George A. Extracellular matrix of dental pulp stem cells: applications in pulp tissue engineering using somatic MSCs. Front Physiol 2014; 4: 395–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tang H, Wu B, Qin X, Zhang L, Kretlow J, Xu Z. Tissue engineering rib with the incorporation of biodegradable polymer cage and BMSCs/decalcified bone: an experimental study in a canine model. J Cardiothorac Surg 2013; 8: 133–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hartenstein V. Hartenstein V. Blood cells and blood cell development in the animal kingdom. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2006; 22: 677–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bao W, Gao M, Cheng Y, Lee H-J, Zhang Q, Hemingway S, Krol A, Yang G, An J. Biomodification of PCL scaffolds with matrigel, HA, and SR1 enhances de novo ectopic bone marrow formation induced by rhBMP-2. BioResearch Open Access 2015; 4: 298–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Shen JF, Sugawara A, Yamashita J, Ogura H, Sato S. Dedifferentiated fat cells: an alternative source of adult multipotent cells from the adipose tissues. Int J Oral Sci 2011; 3: 117–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Phinney DG, Prockop DJ. Concise Review: mesenchymal stem/multipotent stromal cells: the state of transdifferentiation and modes of tissue repair—current views. Stem Cells 2007; 25: 2896–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Romagnoli C, Brandi ML. Adipose mesenchymal stem cells in the field of bone tissue engineering. World J Stem Cells 2014; 6: 144–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]