Abstract

This article reviews fundamental and applied aspects of silk–one of Nature’s most intriguing materials in terms of its strength, toughness, and biological role–in its various forms, from protein molecules to webs and cocoons, in the context of mechanical and biological properties. A central question that will be explored is how the bridging of scales and the emergence of hierarchical structures are critical elements in achieving novel material properties, and how this knowledge can be explored in the design of synthetic materials. We review how the function of a material system at the macroscale can be derived from the interplay of fundamental molecular building blocks. Moreover, guidelines and approaches to current experimental and computational designs in the field of synthetic silklike materials are provided to assist the materials science community in engineering customized finetuned biomaterials for biomedical applications.

Keywords: biomimetic, silk, multiscale modeling, spinning, materiomics

Graphical abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

Nature’s Building Blocks

Nature is rich in structure, which defines the properties of the tiniest pieces of matter, atoms, molecules, galaxies, and the universe. Amino acids are the building blocks of proteins, the most abundant and fundamental class of biological macromolecules. There are only 20 commonly occurring amino acids in natural proteins, and their properties determine the nature of the resulting protein. This limited set of building blocks, i.e., amino acids, gives rise to some of the most diverse material functions identified in protein materials that not only make up everything from silk to skin, and many other organs such as the brain, but also living materials that interact with the environment in many active, dynamic, and controlled ways. These features also drive the interactions and interfaces of these proteins with other materials, including other organic matrices to inorganic components. For instance, abalone shell is made of minerals of calcium carbonate platelets glued by protein1,2 and human bone is primarily composed of collagen protein and hydroxyapatite mineral.3 As we learn more about these processing in Nature, we begin to appreciate the universal importance of hierarchical structures in defining how the living world works.4 This implies exciting possibilities based on the idea of transforming the understanding of these amino acid patterns to new material functions that can find diverse applications in areas of energy and sustainability, health care, and design of novel devices.5–9

From Sequence to Structure

The 20 different chemical building blocks (amino acids) are linked by peptide bonds and dominate biological functions in Nature, from molecular recognition and catalysis to structures. Fibrous proteins, such as silk, collagen, elastin, and keratin are distinguished from globular proteins (such as hemoglobin, immunoglobulins) by their repetitive peptide domains which promote regularity in secondary structure, control of molecular recognition and structural integrity. Fibrous proteins require interchain as well as intrachain interactions to achieve structural function, which is in contrast to globular proteins where single folded chains can achieve catalysis or recognition. The chemistry of the building blocks provides modes for physical associations between chains, including hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions, and the precise control of primary sequence allows for programmed self-assembly. When these features are combined with the power of biological synthesis of the proteins, driven by enzymatic reactions to generate the peptide bonds, control of chirality of the chains is also achieved, helping to preserve registry and molecular fit to give additional molecular recognition and self-assembly to provide the basis for structural hierarchy.9–13

Silk Properties and Production

Silk, with its remarkable structure and versatility, has emerged as a particularly exciting topic of study because of its physical, chemical, and biological properties that lend themselves to many applications, while also serving as a prototype model for future material designs.14–19 Production of silk fiber starts from making polymer from amino acid building blocks. The process continues with change in concentration of the protein and ionization of the environment followed by application of an elongational flow (shear stress). The whole process of building the 3D web is similar to an advanced 3D printer that builds the final product from a digital file using an additive process by laying down successive layers of material and controlling environmental conditions (curing material). Spiders have invented multimaterial 3D printing billions of years ago. Spider web has a multiscale structure that controls mechanical properties of the fiber such as β sheet crystal size and fiber diameter (Figure 1). Silk in its natural forms and two examples of applications are shown in Figure 2

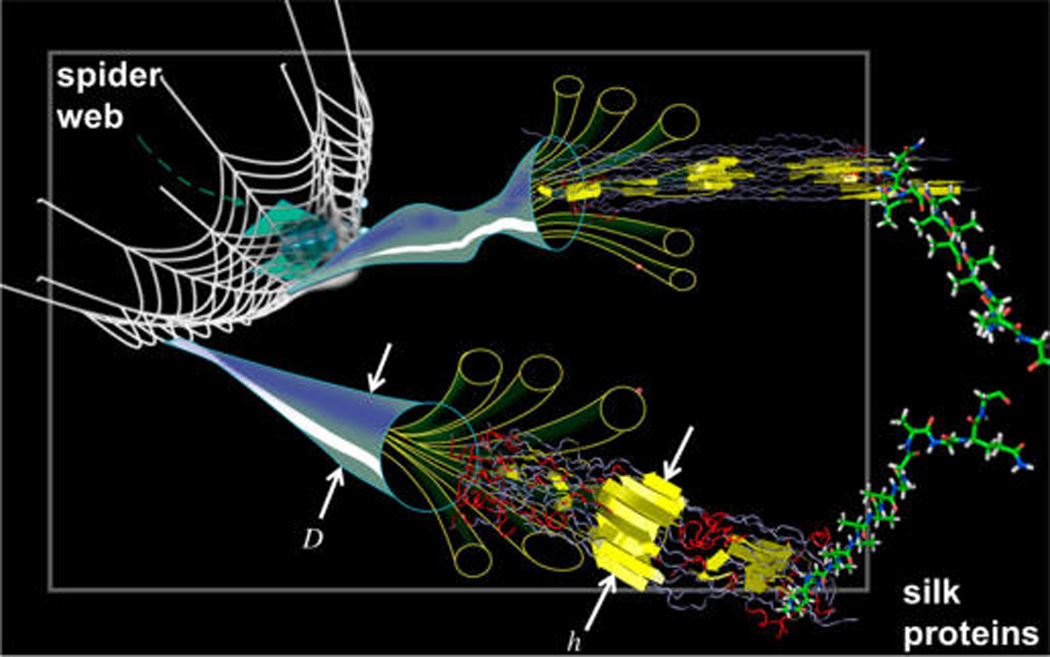

Figure 1.

Visualization of the hierarchical material makeup of silk, achieved by controlling all length-scales from the molecular to the macroscopic scale (examples given here include the fiber diameter D, and the beta-sheet crystal size h).4 Spiders and other silk-spinning insects create these complex structures in a combination of chemical cues and self-assembly (directed via the amino acid sequence), physical mechanisms such as shear flow, and large-scale additive processing realized by the movement of the insect akin to a modern 3D printer, and with multiple materials that are placed in and around the web (spiders have invented multimaterial 3D printing billions of years ago). Original figure courtesy National Science Foundation, and adapted here.

Figure 2.

Samples of different uses of silk, natural and biomedical ones. Images show a spider web (photo courtesy Francesco Tomasinelli and Emanuele Biggi), silk cocoons, silk-based electronics (Reprinted by permission from ref 17. Copyright 2010 Macmillan Publishers.) and the “Silk Pavilion” (Designed by the Mediated Matter Group in collaboration with James Weaver, WYSS Institute, Harvard University and Prof. Fiorenzo Omenetto, TUFT University. Contributing researchers: Markus Kayser, Jared Laucks, Carlos David Gonzalez Uribe, Jorge Duro-Royo and Steven Keating. Photo credit: Steven Keating. Courtesy of Mediated Matter). These examples showcase the versatility of silk in its natural and synthetic uses.

Silks are generally recognized for their unique combination of mechanical properties, including remarkable strength and toughness (Figure 3A). The toughness of spider silk dragline or orb web fibers can be higher than even the best synthetic high performance fibers such as Kevlar, varying depending on the specific source of silk. For example, the strength of spider dragline silk can be in the GPa range, around the same value as steel, yet it has a much lower density than steel. The toughness of spider dragline silk, around 165 ± 30 kJ kg−1, is about two times that of Kevlar 81. One of the constraints in using silk as an industrial material to achieve high toughness is the required extreme extensibility which must be overcome. Importantly, it is not only these high-end mechanical properties that attract attention, but also the fact that these remarkable fibers are generated from a relatively simple protein processed in water under ambient conditions.20 There exist a myriad of silks available that cover a wide range of mechanical properties, from highly compliant with large extension to stiff.21–24

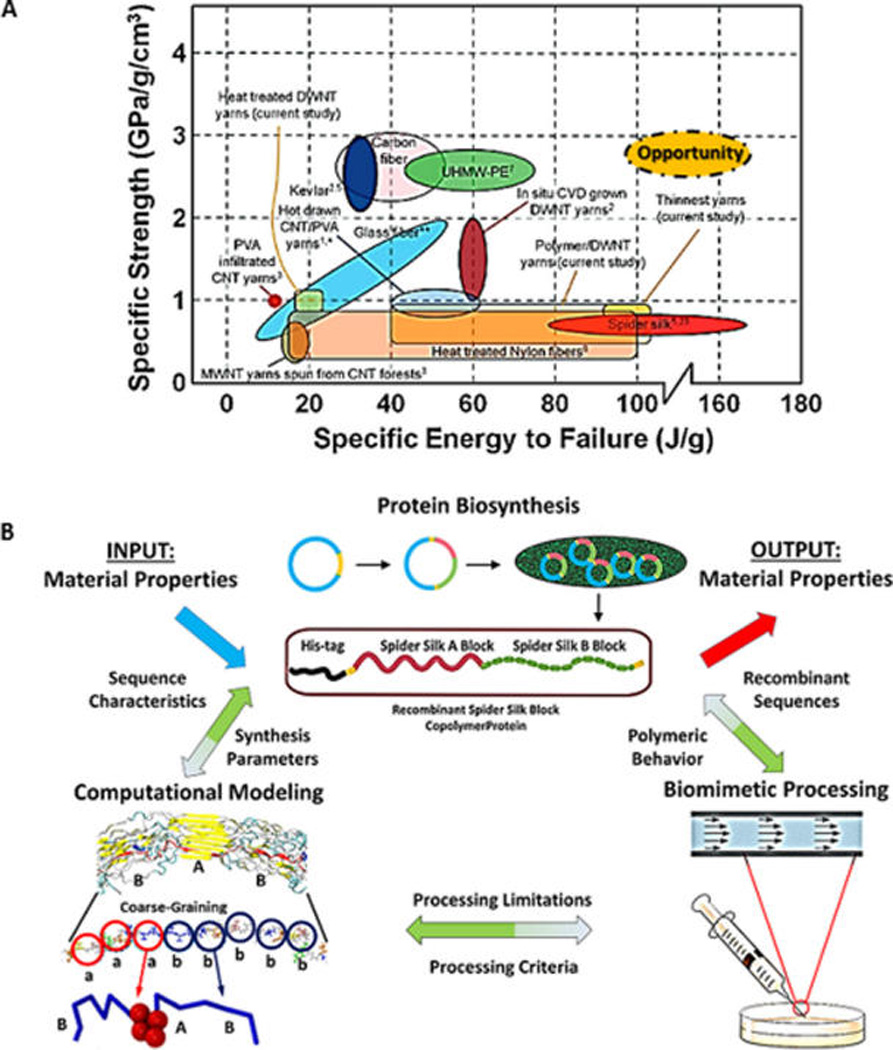

Figure 3.

(A) Ashby plot to illustrate the properties of silk fibers in comparison with other materials. Adapted with permission from ref 177. Copyright 2010 American Chemical Society. An opportunity exists to use the material platform of silk, apply the principles that lead to its remarkable properties in carbon materials (graphene, carbon nanotubes, and other materials), and achieve a material performance that features high specific energy to failure at a high specific strength. (B) Synergetic integrations of multiscale modeling, silk polymer synthesis, and microfluidic fiber spinning to study the hierarchical structure of silk polymers and their self-assembly process.

In addition, different silk material formats are generated in nature, from traditional fibers to sheetlike and ribbonlike morphologies such as those formed by the tarantula. Different material formats are responsible for different functions including protection from the environment during molting (cocoons) and prey capture (orb webs), which are critical for survival of silkworms and spiders, respectively.25 These morphological features originate in the spinning apparatus of the animal but remain underpinned by structural hierarchy. Aside from chemistry, processing conditions directly impact the properties of spun silk fibers.26 For example, although orb web spider silks are generally considered stronger than silkworm silk, properties of silkworm silk fibers analogous to spider silks have been generated by exploiting the native organism using artificial spinning rates.27–29 Also, conventional wet spinning followed by immersion post spinning drawing step has been used to produce silk fibers from regenerated silk worm with mechanical properties comparable to that of spider silk despite their difference in amino acid sequence.30,31 Another way of tuning tensile behavior is combination of supercontraction (see section 3) with wet spinning.32

The range of different spider and silkworm silks is extensive with only a few to date having yielded detailed sequence chemistry and protein domain organization, yet most with similar design features as outlined above. Generally, silk from the domesticated silkworm (Bombyx mori) consists of a single core protein, termed fibroin with high molecular weight (~390 kDa) and spun into a capsule or cocoon during molting from the worm to moth, serving a protective function. The timing of protein production can therefore be programmed with domestication or the process of sericulture with the coordinated raising of silkworms, which has been practiced for centuries in textile production. The macroscale structures of silks represent some of the most advanced biological engineering found in nature, where structural hierarchy has achieved remarkable functional outcomes. For example, an exceedingly small amount of spider silk (milligrams) can generate an exceptionally functional large aerial array (orb web) to capture prey. Further, all aspects of the web design are matched to optimize mechanics related to prey size and environmental conditions such as humidity and temperature.33–37 The physics and biology of such minimalist, lightweight, yet functional materials remains to be emulated with synthetic materials, not to mention the entirely green process utilized in terms of synthesis, processing, and degradation.

Silk Protein Domains

The modular protein designs in silk chains include specific peptide domains that have evolved to accommodate mechanical functions for the fibers formed within the constraints of biological processing (i.e., aqueous environment, ambient temperature). The modular design features include N- and C-terminal peptide domains of around 100 amino acids (N-terminus around 130 amino acids, C-terminus around 100 amino acids). While C-terminus is conserved among species of silkworms and spiders, N-terminus is conserved among spiders (N-terminus of silkworm is different from that of spider silk). These termini provide charge dense regions to facilitate aqueous solubility and to modulate self-assembly via pH induced changes in structure.38,39 The core of the silk, which is composed of repetitive hydrophobic/ hydrophilic sections is responsible for its mechanical properties. Its specific amino acid motifs are explained in section 3.

Stability and Solubility

Silk fibers can withstand wide ranges of moisture, pH, organic solvents, salts and temperature, in contrast to most globular proteins.43 Only a limited number of conditions (salt solutions and solvents) have been identified that solubilize silk protein fibers without destroying the molecular weight of the chains, including lithium bromide, lithium thiocyanate, calcium nitrate, and hexafluoroisopropanol.44 Silks are susceptible to proteolytic digestion45 and also exhibit excellent biological compatibility, allowing silk-based medical devices to be pursued.42

Scope of the Current Review

Silk has different interesting properties and applications and a single review article cannot cover all aspect of the subject in detail. There are numerous review papers focusing on different aspects of the research at the time. Some of them are focusing on spinning process into different morphologies and potential applications,14,40,46–51 some on the role of terminals,52,53 some on the molecular biology and production processes,37,44,54–64 some on the biomedical applications,45,65–71 some on the water sensitivity,19,72,73 and some on using Raman spectroscopy74 or solid-state NMR to study structure of silk.74,75 The purpose of this review is to present progresses of the field in the recent past with emphasize on the power of genetic encoding and the integration of simulation with experiment to tailor material properties.

2. NATURAL AND SYNTHETIC MAKING OF SILK

Mimicking Nature

Silk generally comes from Nature in fiber form, from cocoons to orb webs. However, the reverse engineering technique of silk fibers back into solution has been achieved. This technique generally encompasses disruption of the hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions that modulate intra- and interchain interactions. This process leads to the formation of solutions of silk whereby subsequent steps to disrupt water of hydration (e.g., exposure to methanol, heat, low pH) or to add energy related to protein chain dynamics (e.g., shear, electric fields, sonication) drive interchain interactions leading to new silk material morphologies such as hydrogels, films, new fibers, coatings, and 3D matrices.76–82 Water annealing from exposing silk materials to high humidity results in slow and controllable crystallization.83,84 This approach is in contrast to exposure to methanol,85 which results in uncontrolled and rapid crystallization. The extent of reformation of beta sheets in these silk materials impacts their stability, mechanical properties, optical properties, and degradation rate. For example, higher crystallinity impedes proteolytic digestion of the silk.86

There are a wide variety of processes by which silk can be processed, but here we focus on processes that mimic those found in nature. Although the exact natural mechanisms remain unclear, there are several key anatomical elements in common to the silkworm and spider involved in fiber formation. Silk proteins are extruded through long sections of glands that enable protein–protein interactions that stabilize β sheet formation. Changes in ion concentrations and pH of the solution are also known to affect fiber formation.87–91 Much of what is known about silk assembly is through the extraction of solutions from specific regions of the gland. The protein mixtures and their dynamic assembly properties can then be studied in the laboratory using techniques such as mass spectrometry, circular dichroism, protein electrophoresis, and dynamic light scattering.92–99

Another approach to study silk assembly is to use microfluidics to not only mimic the natural assembly process but also enable direct visualization of fiber formation under flow focusing conditions with controllable flow rates. Silk has its remarkable properties at the micron scale which makes it unique compared to the other materials. This is another reason to use microfluidic device to assemble protein sequence starting from the small scale in a controlled environment up to the micrometer scale. For example, the spider gland is known to dynamically change the thickness of the silk fibers in its spinnerets. In the spinning duct of the silkworm, shear stress or stretching in the thin duct cause the orientation of the fiber, stretching the globular protein as well as significant drop in pH.

Subsequently, crystallization occurs with shearing and dehydration. Similarly, in the microfluidic setup, one can apply shear stress with high flow rate to silk fibroin stream to help forming silk fiber or introduce PEG (polyethylene glycol) solution to mimic pH drop or changes in ion concentration to mimic what happens in the natural process.100–103 Using solvent bath to dehydrate and crystallize is another example of mimicking natural spinning process, which also affects the mechanical property of silk fiber. Another advantage of microfluidic processing is the low amounts of material required. This is particularly useful for studies in which one would like to characterize the relationship between sequence and structure in recombinant silk proteins, which can be time-consuming and costly to express in large quantities. Using an approach that uses the anatomy of the natural gland as inspiration, one can systematically study the effects of shear rate, composition of additives (e.g., other proteins, ions), pH on silk fiber formation.103–107 Moreover, one can investigate the minimal structural unit required for assembly. Postprocessing steps such as fiber drawing that can occur especially in spider silk assembly can also be included in these systems. Importantly, the relationships between composition, structure, processing, and properties can be systematically studied and applied to the design of silk materials with tunable properties (Figure 3B).108

Silk as a Model System

The modular nature of the silk protein design can also serve as Natures’ mimic for synthetic polymer designs. Thus, silks can serve as accessible block copolymer models for future designs of synthetic analogs, e.g., exploiting the useful features of silks but with alternative building block chemistries. Silk protein-based block copolymers have been pursued based on this concept, as a highly controllable approach to study silk designs related to understanding self-assembly and material functions. The ability to program sequence chemistry, domain sizes, molecular weight distributions, and overall chain length provide unprecedented opportunity to probe structure–function with control of secondary structure at levels of structural hierarchy that cannot be achieved today via chemical synthesis.109,110 Recombinant DNA technology is exploited, where silk variants in terms of size and variations in hydrophobicity–hydrophilicity have been synthesized, purified, and studied related to β sheet formation, morphology from solution, fiber spinning, and mechanical properties.93,111–115

Using this tool, hierarchical structures of silk are explored in synthetic polymer designs. For instance, bacterial expression of a group of uniform family of periodic polypeptides shows that the periodicity of the primary sequence of polypeptide controls the thickness of the β sheet structures in the solid state.116 Moreover, NMR spectroscopy on the polypeptides with labeled alanine-rich segments shows conformational rearrangement of the amphiphilic alanine-rich segments from alpha helices to beta strands during self-assembly of the protein into memberane.117 This finding suggests manipulation of stability conditions of alpha helices versus β sheet to control self-assembly of the block copolymer. As another example, sensitivity of the self-assembly of a silk like amphiphilic block copolymer to the solvent condition such as pH or aqueous alkaline versus methanol solution has been used to control morphology of the polymer at the macroscale.118

The integration of experiment and simulation in multiscale design opens new avenues to explore the physics of materials from a fundamental perspective, and using complementary strengths from models and empirical techniques. Using silk as a model material–driven by its relative simplicity in amino acid sequence–recent developments illustrate a new paradigm by which complex function is achieved through the explicit design of hierarchical structuring. An important impact is that computational experiments helped to identify common principles shared by a broad range of biological materials. A comparative approach that studied the structure and function of silk with that of bone or nacre shows the universal role of hierarchical mechanisms in creating material function.119–125 For instance, the ratio of the hydrophilic to hydrophobic block of amino acids in recombinant spider silk controls the secondary structure and connectivity of the polymer network, which results in different material properties at the macroscale.126

There is a need to use different computational and experimental methods with different resolution in length (and time) scale to study material properties. As Figure 4 shows, we can start from modeling electrons to study band structures (quantum mechanics) at the scale of angstrom and transfer information across scales up to the continuum level at the scale of centimeter and beyond. Similarly, studying different phenomenon occurring during synthesis and processing of the material requires different experimental techniques ranging from X-ray diffraction and transmission electron microscopy to imaging methods. For instance, mechanical response of silk crystalline domain was measured with combination of tensile test and X-ray diffraction127 and modeled with molecular dynamics combined with finite element method.128 Recently, new fiber rheology measurements like measuring wave speed129 or thermal analysis130 were used to address performance of silk in nature.

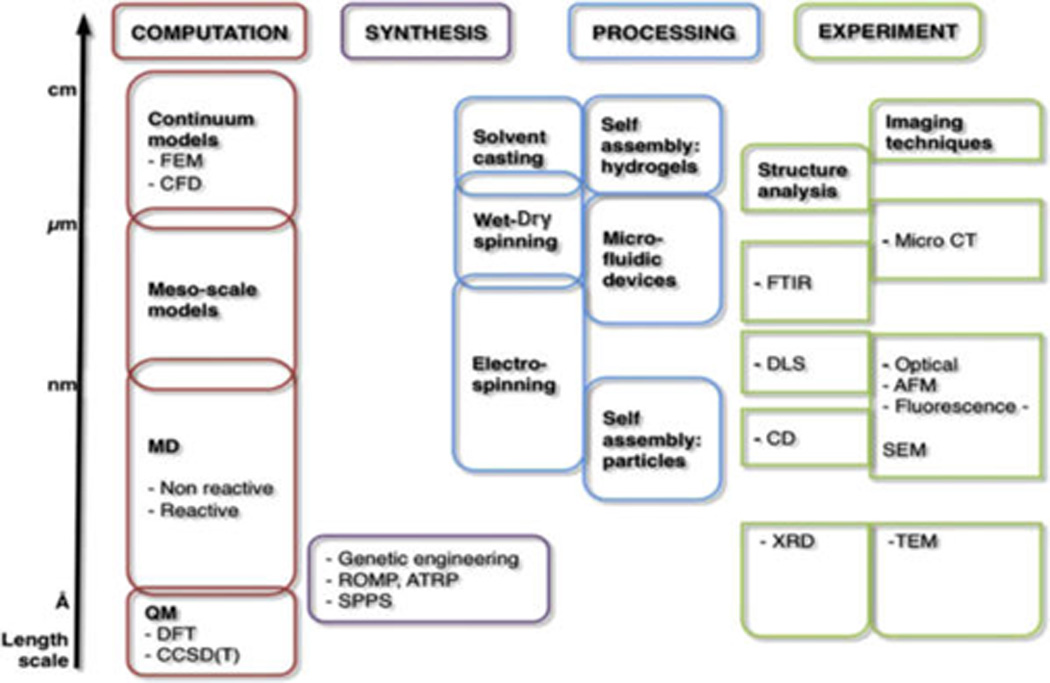

Figure 4.

Overview of computational and experimental techniques that cover multiple scales, necessary for the systematic and holistic analysis of silk and silk-like materials, including materials design. Reprinted with permission from ref 178. Copyright 2012 Elsevier. The complex hierarchical structure of silk requires the use of a host of experimental and computational technique to move the analysis and synthesis of this material forward. Abbreviations are as follows: FEM, finite element method; CFD, computational fluid dynamics; MD, molecular dynamics; QM, quantum mechanics; DFT, density functional theory; CCSD(T), coupled cluster method; ROMP, ring opening metathesis polymerization; ATRP, atom transfer radical polymerization; SPPS, solid phase peptide synthesis; FTIR, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy; DLS, dynamic light scattering; CD, circular dichroism spectroscopy; XRD, X-ray diffraction; MicroCT, microtomography; AFM, atomic force microscopy; SEM, scanning electron microscopy; TEM, transmission electron microscopy.

Enabled by the significant development of computational resources and new algorithms to enhance sampling, atomistic modeling can now be applied to treat very large systems at increasingly large time-scales. In particular, the combined application of atomistic-based multiscale modeling and experiment has emerged as an important area with very broad reach, as the use of such material models provides fundamental insights into the mechanisms by which materials function and fail, enable one to explain experimental observations, and facilitate the use of this insight into design new materials. For instance, Figure 5 shows integration of simulation and experiment to explain the role of shear flow in fiber assembly. The simulation of increasingly complex process conditions is an important frontier, and applications to silks and silk-inspired materials are no exception. Indeed, the combined application of modeling and experiment has been particularly impactful in comparative studies aimed at investigating the origin of the diversity of protein material properties in spite of their similar building blocks (amino acids), as well as different types of silks. Recent work has exploited the use of models in the design of novel silk materials, for example, in the development of bioengineered design of silks.

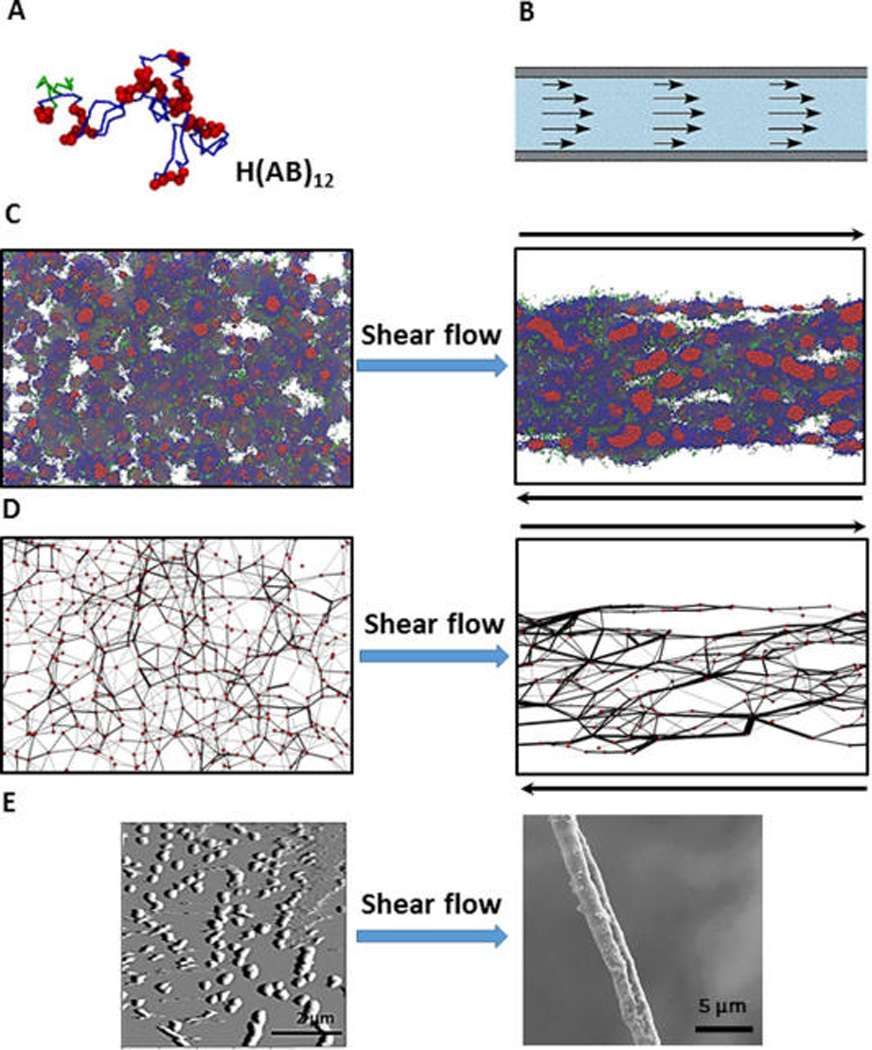

Figure 5.

Fiber spinning combining experiment and simulation. (A) Color code of a single recombinant silk protein H(AB)12 in simulation: green, H domain, hexahistidine fusion tag; red, A domain, hydrophobic block; blue, B domain, hydrophilic block. (B) Shear flow in syrange provides flow focusing process of spinning duct of spider. (C) Simulation snapshots after equilibration (left) and after shear flow (right) show that isolated clusters of hydrophobic domains (red spheres) get connected and directed toward shear flow. (D) Post processing of the simulation results. Red circles (nodes) are assigned to the center of the hydrophobic clusters. Two nodes are assumed to be connected by a black line connection (bridge) if part a chain appears in those two nodes. Shear processing increases the connectivity of the network of polymer (E) AFM result on the left shows formation of micels (corresponding to nodes in the simulation). SEM image of the dried fiber on the right shows flow focusing effect after spinning. Reprinted with permission from ref 179. Copyright 2015 Macmillan.

3. STRUCTURAL-MECHANICAL FUNCTION

Silk Function within Web

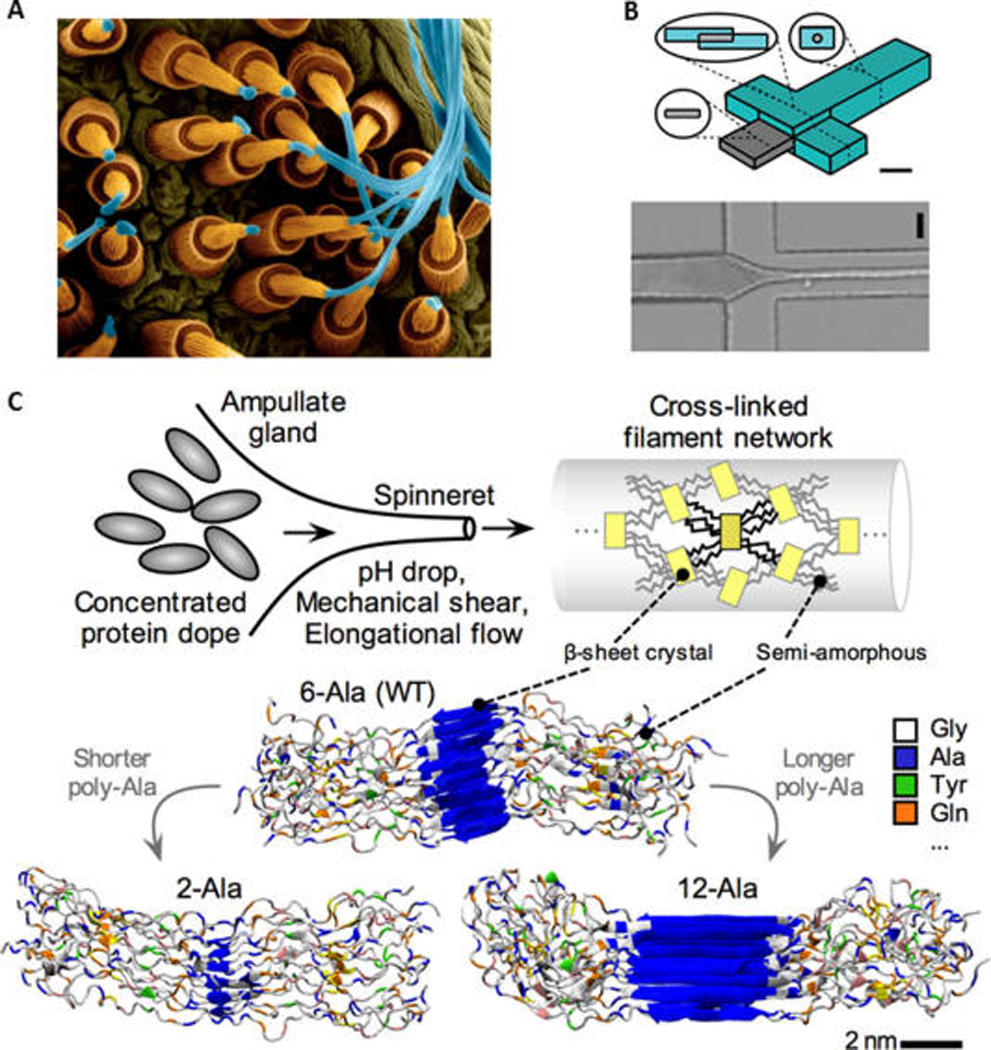

In its natural role, silk features a hierarchical structure (Figure 1). In a series of studies,11,131–135 it was demonstrated how different hierarchical levels in silk, from the protein molecules to a spider web or cocoon, play together to create a strong and resilient structure. This example shows how merging “structure” and “material” is critical to overcome the limitations of the inferior natural building blocks of this material to achieve a system whose overall performance cannot yet be rivaled by any engineered substitute, and how processing plays a critical role. Figure 6 as a general overview shows fiber formation from silk protein in nature, using microfluidic device to mimick natural process and using simulation tool to explain the effect of the size of poly alanine (crystalline section) in mechanical properties of the silk. The strength, stiffness and toughness of spider silk can be explained by the material’s unique structural organization. The multiple hierarchical levels are a manifestation of how the biochemical information that defines the protein sequence directly affects the behavior of the system at the structural scale of a web, which can be exposed to a range of mechanical loading. This work has also shown that each level in the material contributes to the overall properties, and that the remarkable properties of the entire system emerge because of a series of synergistic interactions across the scales (where the sum is more than its parts).136 A particularly interesting aspect is how the nonlinear material behavior of silk fibers affects the web behavior.132

Figure 6.

Fiber formation from spider silk proteins upward: (A) Natural. Copyright Dennis Kunkel Microscopy, Inc./Visuals Unlimited/Corbis. (B) Bioinspired microfluidic process, which used microfluidic for silk worm silk. (Adapted with permission from ref 103. Copyright 2011 American Chemical Society.) Similar principles apply to the production of spider silk. (C) Detailed molecular view. (B) Regenerated silk fibroin (RSF) solution flows through the central channel while acidic poly(ethylene-oxide) (PEO) solution flows through the side channels. As these solutions combine and flow in the device, the PEO solution surrounds the silk solution, focusing hydrodynamic silk solution stream, causing a narrowing of fiber diameter, permitting diffusion of hydrogen ions into the silk to generate RSF fiber. The schematic of the device (B left side) features a scale bar 400 um, and the microscopic image (B bottom) of the actual spinning process has a scale bar 200 um, where RSF solution inlet is the left channel, PEO solution inlet for top/bottom channel and silk stream outlet is right channel. (C) In the process of silk spinning, a combination of chemistry and shear flow transform the concentrated protein dope into a network cross-linked by aligned crystalline overlaps held by aligned hydrogen bonds. Lower images reprinted from ref 180. Copyright 2011 Wiley. The image also explains the effect the amino acid sequence has on the molecular structure of the silk fiber, where the number of alanine amino acid repeats controls the size of beta-sheet nanocrystals at the nanometer length-scale.

Silk fibers typically soften at the yield point to dramatically stiffen during large deformations until point of failure, whose origin has been traced to the particular structure of silk proteins and the nanocomposite they form. Their particular stress– strain behavior and their geometrical arrangement in a web allows localization of deformation upon loading (around loading point), and makes spider webs robust and extremely resistant to defects, as compared to a hypothetical linear-elastic or elastic-plastic models of silk fiber. Through in situ experiments on spider webs the computational prediction was validated that locally applied loading results in minimal damage. It was also found that under global loads such as wind, the behavior of silk material under small-deformation–typically showing a small but very stiff regime–is crucial to maintain the structural integrity of the web.132 A combined computational-experimental study paired with a theoretical mechanics analysis of the findings helped to gain a generalized insight of the strength of the fiber by identifying a fracture mechanics-based scaling law. What is unique about this work is that it began at the molecular level and assessed the impact of the material composition from the chemical scale all the way to the macroscopic structure of a web.

Molecular Structure of Silk

Different species of spider produce different webs with vastly different constitutive laws. Up to now, most of the research has been focused on orb web weaving spiders which we explain in the following section. We should note that features are not universal. Different web architectures exist, and the correlation between mechanical response, molecular structure, and web response is still an outstanding “mystery”.

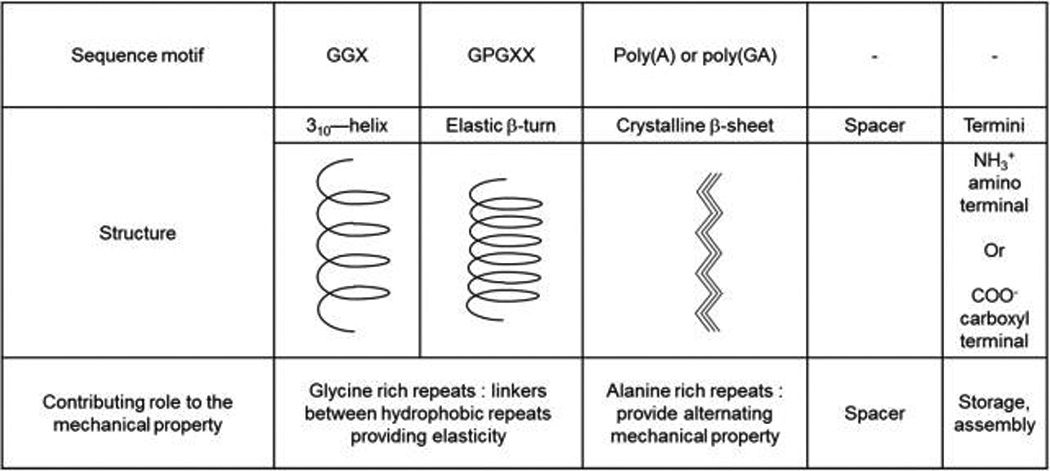

The combination of computational and experimental work has revealed simple physical mechanisms by which the nonlinear material behavior of silk fibers can be controlled. These features were all due to the protein sequence, which is used to generate distinct microstructures (so-called secondary structures) which are realized by sequence patterns rich in the amino acid Alanine that generate very stiff and strong crystals and support mechanical integrity (they do not like to mix with water, called “A” block), and those rich in glycine amino acids that lead to more disorganized, labile and very soft regions (they like to mix with water, called “B” block).133,135,137,138 The relative amount and combination of these building blocks is the paradigm by which silk threads can achieve very diverse mechanical signatures (spiders can produce different types of silks for different purposes with diverse range of mechanical behaviors).11 The difference in mechanical properties is dictated by differences in the secondary structure of silks (Table 1). The core regions of the majority of spider silks are made up from four different motifs: (i) 310-helix forming repeats GXX; (ii) crystalline β-sheet rich poly(A)/poly(GA) motifs (where A and G are alanine and glycine)., (iii) an elastic β-turn-like proline-rich region, composed of multiple GPGXX motifs (where P is proline and X is mostly glutamine); and (iv) a spacer region with unknown functions.139 These glycine-rich repeats (i.e., GGX and GPGX) serve as linkers connecting hydrophobic repeats and provide silk with elasticity.40,41 Recently, it was shown that amorphous phase containing GGX and GPG motifs can take up polyglycine II nanocrystal structure.140 Moreover, different types of similar secondary structures result in alternating mechanical properties. For example, in dragline silks, the tensile strength of the silk fiber is controlled by the silk primary structure, which in turn dictates the strength of interactions between β-sheets. In the case of poly(A) repeats, each A residue is placed on alternative sides of a protein backbone. The hydrophobic interactions that arise from such conformation connect poly(A) chains together by protruding methyl groups occupying the void space near the α carbon of a residue on a neighboring chain. As a result, β-sheets have no void space and are impenetrable to water. The poly(GA) regions form a similar secondary structure, but with a different hydrophobic pattern. The glycine side chain is unable to form the same hydrophobic interactions as the A side chain resulting in fewer links in the β-sheet structure, and thus different mechanical properties.24,48 The same observations are true in the case of B.mori silk. The core of the silkworm silk (which is weaker than spider silk) is composed of sequences of hexapeptides including: GAGAGS, GAGAGY, GAGAGA, or GAGYGA (where S is serine and Y is tyrosine).42

Table 1.

Four Different Motifs of Core Regions in Spider Silk Fibrila

|

Supercontraction

Certain spider dragline silk fibers show an unusual behavior at high humidity. They can shrink up to 50% if unconstrained. In a constrained fiber change of humidity results in a substantial change in internal stress. This phenomenon is known as supercontraction.141 There is a controversy about the biological importance of the effect.142 Tensile test of supercontracted fibers in water shows rubberlike behavior with a large increase in elasticity and decrease in stiffness compared to the dry fibers.143 Also, dragline silk undergoes cyclic relaxation-contraction response upon change in humidity.144 While in some applications supercontraction effect is undesirable, it could be useful to make biomimetic muscle fibers145 Moreover, the interplay between supercontraction and mechanical properties could be used to tailor material property of silk fibers.146 It has been hypothesized that the origin of the supercontraction should be inside semi amorphous part of the dragline silk since little change was observed in structural properties of the hydrophobic region (crystalline beta sheets) after wetting147 Using NMR studies, it is suggested that highly conserved YGGLGS(N)QGAGR block which only exists in spider dragline silk, plays the key role in the supercontraction effect.148 Further investigation of the nanostructure revealed the importance of hydrophobic residues, and suggested a suppression of the supercontraction effect by targeted sequence mutation.149

4. FUTURE CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES

Biomedical Applications

Silks are attractive scaffold materials for tissue engineering because of their biocompatibility and tunable (based on β sheet content) biodegradability.150–152 Moreover, as described above, silk can be genetically programmed and assembled into hierarchical structures with tunable mechanical properties, which lends itself well to assembling biomaterials and thus tissues which themselves display complex hierarchical organization. There are several approaches to generate silk scaffolds that are integrated with cells. Using an additive manufacturing approach, individual 2D sheets of silk (fibrous mats or films) can be stacked into 3D structures.153 To promote cell adhesion, one can include cell adhesive ligands, which can be achieved by genetic modification or, as described in the next section, by forming alloys with cell adhesive proteins such as fibronectin and collagen.154 There can also be natural adsorption of cell adhesive proteins once silk is implanted in vivo. Silk or silk composites have been explored in a wide variety of tissue engineering examples including tendon, nerve, blood vessels and bone, among others.81,155–167

Silk can be used for both soft and hard tissue applications as further example of its versatility. Bone mineralization can be accelerated by promoting the deposition of calcium phosphate in combination with silks. Silks are nonimmunogenic and also induce low inflammatory responses in vivo, further reasons for the utility of silks for biomedical applications.45,65,68,168–173

Infusion of Other Particles, Ions, or Molecules

The unique assembly properties of silk can also be exploited to assemble nanostructures. These bioinspired materials are formed by essentially templating nanoparticles or other structures onto silk assemblies. For example, quantum dots or metal (e.g., silver) nanoparticles can be added to produce composite materials with unique mechanical, optical, and electrical properties. The silver nanoparticles also have antimicrobial properties which makes them suitable for biomedical applications.174 A particularly interesting example is in the area of energy materials for electrocatalysts.175 Many of the advantageous properties of silk described above can be exploited, namely specific amino acids in silk fibroin can interact with graphene oxide to help dispersion, and other silk amino acids can interact with metal nanoparticles that result in their unique assembly. Furthermore, because silk fibroin is water-soluble, these processes lend themselves for green manufacturing. These approaches can also be enhanced with the bioengineered silk variants mentioned above, where selective peptide chemistries can be added into silk to optimize interfaces with metals or other components.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Silks arguably are the quite remarkable materials in nature. As evolved, they already are exemplary models of material efficiency and function, with lightweight mechanically robust systems that exist in virtually any environment on the planet. Their diversity of functions provides a template to study and exploit structure–function relationships in future material designs to modify an unending set of options to expand functional features, and to perform all aqueous and ambient processing conditions along with 100% degradability. These features provide a template for design of new devices with environmental and biological compatibility as well as a model for future designs of synthetic polymers to emulate silks. The tunable mechanical properties, tunable degrade rates, and the robust β sheet physical cross-links that negate the need for chemical cross-linking and the diverse modes of processing material, they all drive interest and an exciting future in silks. There are no other synthetically or biologically derived polymer systems that offer this range of useful material properties or biological interfaces. Thus, silk remains as a model to study, copy, and exploit in the future and we are just starting on this path, with exploration of future matches between needs and designs.

It is interesting therefore to look back to envision the future. The origins of silk back to more than 5000 years ago served as a bridge between cultures and as an economic engine for developing countries over the millennia, due to the emergence of silk as a commodity textile. With the advances in silk in high technology applications and the growing insight into the origins of the unique properties, silk serves as a nucleus of inquiry into the future. Sericulture established large scale production of silk, however, this tip of the iceberg is clear when considering the range of silk in Nature, options for bioengineered silk variants and the versatile processing modes to produce a range of material morphologies. We are just at the beginning of this new Silk Road, one with impact into medical materials and devices, high technology applications, and new polymer designs. Nature continues to provide inspiration and silk remains at the center of this web of inquiry with seemingly endless opportunities.176

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support from NIH (U01 EB014976). Additional support provided by ONR-PECASE, ARO-MURI, and AFOSR.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Smith BL, et al. Molecular mechanistic origin of the toughness of natural adhesives, fibres and composites. Nature. 1999;399(6738):761–763. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sellinger A, Weiss PM, Nguyen A, Lu Y, Assink RA, Gong W, Brinker C, et al. Continuous self-assembly of organic–inorganic nanocomposite coatings that mimic nacre. Nature. 1998;394(6690):256–260. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wahl D, Czernuszka J. Collagen-hydroxyapatite composites for hard tissue repair. Eur. Cell Mater. 2006;11:43–56. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v011a06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buehler MJ. Materials by design—A perspective from atoms to structures. MRS Bull. 2013;38(02):169–176. doi: 10.1557/mrs.2013.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ragauskas AJ, et al. The path forward for biofuels and biomaterials. Science. 2006;311(5760):484–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1114736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sudesh K, Iwata T. Sustainability of biobased and biodegradable plastics. Clean: Soil, Air, Water. 2008;36(5–6):433–442. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams DF. On the nature of biomaterials. Biomaterials. 2009;30(30):5897–5909. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakiyama-Elbert S, Hubbell J. Functional biomaterials: design of novel biomaterials. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2001;31(1):183–201. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang S. Fabrication of novel biomaterials through molecular self-assembly. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21(10):1171–1178. doi: 10.1038/nbt874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rockwood DN, et al. Materials fabrication from Bombyx mori silk fibroin. Nat. Protoc. 2011;6(10):1612–1631. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giesa T, et al. Nanoconfinement of spider silk fibrils begets superior strength, extensibility, and toughness. Nano Lett. 2011;11(11):5038–5046. doi: 10.1021/nl203108t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aggeli A, et al. Hierarchical self-assembly of chiral rod-like molecules as a model for peptide β-sheet tapes, ribbons, fibrils, and fibers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98(21):11857–11862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191250198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whitesides GM, Grzybowski B. Self-assembly at all scales. Science. 2002;295(5564):2418–2421. doi: 10.1126/science.1070821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Omenetto FG, Kaplan DL. New opportunities for an ancient material. Science. 2010;329(5991):528–531. doi: 10.1126/science.1188936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tao H, et al. Implantable, multifunctional, bioresorbable optics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109(48):19584–19589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209056109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hwang S-W, et al. A physically transient form of silicon electronics. Science. 2012;337(6102):1640–1644. doi: 10.1126/science.1226325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim D-H, et al. Dissolvable films of silk fibroin for ultrathin conformal bio-integrated electronics. Nat. Mater. 2010;9(6):511–517. doi: 10.1038/nmat2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xia X-X, et al. Native-sized recombinant spider silk protein produced in metabolically engineered Escherichia coli results in a strong fiber. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107(32):14059–14063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003366107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vollrath F, Porter D. Spider silk as archetypal protein elastomer. Soft Matter. 2006;2(5):377–385. doi: 10.1039/b600098n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vollrath F, Knight DP. Liquid crystalline spinning of spider silk. Nature. 2001;410(6828):541–548. doi: 10.1038/35069000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swanson B, et al. Variation in the material properties of spider dragline silk across species. Appl. Phys. A: Mater. Sci. Process. 2006;82(2):213–218. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Madsen B, Shao ZZ, Vollrath F. Variability in the mechanical properties of spider silks on three levels: interspecific, intraspecific and intraindividual. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 1999;24(2):301–306. doi: 10.1016/s0141-8130(98)00094-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vollrath F. Strength and structure of spiders’ silks. Rev. Mol. Biotechnol. 2000;74(2):67–83. doi: 10.1016/s1389-0352(00)00006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gosline J, Guerette PA, Ortlepp CS, Savage KN. The mechanical design of spider silks: from fibroin sequence to mechanical function. J. Exp. Biol. 1999;202(23):3295–3303. doi: 10.1242/jeb.202.23.3295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jin H-J, Kaplan DL. Mechanism of silk processing in insects and spiders. Nature. 2003;424(6952):1057–1061. doi: 10.1038/nature01809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perea GB, et al. The variability and interdependence of spider viscid line tensile properties. J. Exp. Biol. 2013;216(24):4722–4728. doi: 10.1242/jeb.094011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shao Z, Vollrath F. Materials: Surprising strength of silkworm silk. Nature. 2002;418(6899):741–741. doi: 10.1038/418741a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khan MMR, et al. Structural characteristics and properties of Bombyx mori silk fiber obtained by different artificial forcibly silking speeds. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2008;42(3):264–270. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elices M, et al. Example of microprocessing in a natural polymeric fiber: role of reeling stress in spider silk. J. Mater. Res. 2006;21(08):1931–1938. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Plaza GR, et al. Correlation between processing conditions, microstructure and mechanical behavior in regenerated silkworm silk fibers. J. Polym. Sci., Part B: Polym. Phys. 2012;50(7):455–465. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Plaza GR, et al. Old silks endowed with new properties. Macromolecules. 2009;42(22):8977–8982. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guinea G, et al. Stretching of supercontracted fibers: a link between spinning and the variability of spider silk. J. Exp. Biol. 2005;208(1):25–30. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vollrath F, Downes M, Krackow S. Design variability in web geometry of an orb-weaving spider. Physiol. Behav. 1997;62(4):735–743. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(97)00186-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sandoval C. Plasticity in web design in the spider Parawixia bistriata: a response to variable prey type. Functional Ecology. 1994;8:701–707. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henschel J, Lubin Y. Environmental factors affecting the web and activity of a psammophilous spider in the Namib Desert. J. Arid Environ. 1992;22(2):173–189. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pasquet A, Ridwan A, Leborgne R. Presence of potential prey affects web-building in an orb-weaving spider Zygiella x-notata. Anim. Behav. 1994;47(2):477–480. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vollrath F. Biology of spider silk. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 1999;24(2):81–88. doi: 10.1016/s0141-8130(98)00076-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hagn F, et al. A conserved spider silk domain acts as a molecular switch that controls fibre assembly. Nature. 2010;465(7295):239–242. doi: 10.1038/nature08936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Askarieh G, et al. Self-assembly of spider silk proteins is controlled by a pH-sensitive relay. Nature. 2010;465(7295):236–238. doi: 10.1038/nature08962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kluge JA, et al. Spider silks and their applications. Trends Biotechnol. 2008;26(5):244–251. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guerette PA, et al. Silk properties determined by gland-specific expression of a spider fibroin gene family. Science. 1996;272(5258):112–115. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vepari C, Kaplan DL. Silk as a biomaterial. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2007;32(8):991–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Silk . Van Nostrand’s Scientific Encyclopedia. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Winkler S, Kaplan DL. Molecular biology of spider silk. Rev. Mol. Biotechnol. 2000;74(2):85–93. doi: 10.1016/s1389-0352(00)00005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murphy AR, Kaplan DL. Biomedical applications of chemically-modified silk fibroin. J. Mater. Chem. 2009;19(36):6443–6450. doi: 10.1039/b905802h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hardy J, Scheibel T. Silk-inspired polymers and proteins. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2009;37(4):677. doi: 10.1042/BST0370677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Humenik M, Smith AM, Scheibel T. Recombinant spider silks—biopolymers with potential for future applications. Polymers. 2011;3(1):640–661. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eisoldt L, Smith A, Scheibel T. Decoding the secrets of spider silk. Mater. Today. 2011;14(3):80–86. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hardy JG, Scheibel TR. Composite materials based on silk proteins. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2010;35(9):1093–1115. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen X, Shao Z, Vollrath F. The spinning processes for spider silk. Soft Matter. 2006;2(6):448–451. doi: 10.1039/b601286h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schacht K, Scheibel T. Processing of recombinant spider silk proteins into tailor-made materials for biomaterials applications. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2014;29:62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2014.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eisoldt L, Thamm C, Scheibel T. The role of terminal domains during storage and assembly of spider silk proteins. Biopolymers. 2012;97(6):355–361. doi: 10.1002/bip.22006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hagn F. A structural view on spider silk proteins and their role in fiber assembly. J. Pept. Sci. 2012;18(6):357–365. doi: 10.1002/psc.2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hu X, et al. Molecular mechanisms of spider silk. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2006;63(17):1986–1999. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6090-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Heim M, Keerl D, Scheibel T. Spider silk: from soluble protein to extraordinary fiber. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48(20):3584–3596. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Römer L, Scheibel T. The elaborate structure of spider silk. Prion. 2008;2:154–161. doi: 10.4161/pri.2.4.7490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tokareva O, et al. Structure–function–property–design interplay in biopolymers: Spider silk. Acta Biomater. 2014;10(4):1612–1626. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hinman MB, Jones JA, Lewis RV. Synthetic spider silk: a modular fiber. Trends Biotechnol. 2000;18(9):374–379. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(00)01481-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chung H, Kim TY, Lee SY. Recent advances in production of recombinant spider silk proteins. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2012;23(6):957–964. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Scheibel T. Spider silks: recombinant synthesis, assembly, spinning, and engineering of synthetic proteins. Microb. Cell Fact. 2004;3(1):14. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-3-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lewis RV. Spider silk: ancient ideas for new biomaterials. Chem. Rev. 2006;106(9):3762–3774. doi: 10.1021/cr010194g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fahnestock SR, Yao Z, Bedzyk LA. Microbial production of spider silk proteins. Rev. Mol. Biotechnol. 2000;74(2):105–119. doi: 10.1016/s1389-0352(00)00008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Heim M, Römer L, Scheibel T. Hierarchical structures made of proteins. The complex architecture of spider webs and their constituent silk proteins. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010;39(1):156–164. doi: 10.1039/b813273a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rising A, et al. Spider silk proteins-mechanical property and gene sequence. Zool. Sci. 2005;22(3):273–281. doi: 10.2108/zsj.22.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rising A, Widhe M, Johansson J. Spider silk proteins: recent advances in recombinant production, structure–function relationships and biomedical applications. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2011;68(2):169–184. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0462-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Numata K, Kaplan DL. Silk-based delivery systems of bioactive molecules. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2010;62(15):1497–1508. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wenk E, Merkle HP, Meinel L. Silk fibroin as a vehicle for drug delivery applications. J. Controlled Release. 2011;150(2):128–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Spiess K, Lammel A, Scheibel T. Recombinant spider silk proteins for applications in biomaterials. Macromol. Biosci. 2010;10(9):998–1007. doi: 10.1002/mabi.201000071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang Q, Yan S, Li M. Silk fibroin based porous materials. Materials. 2009;2(4):2276–2295. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tao H, Kaplan DL, Omenetto FG. Silk materials–a road to sustainable high technology. Adv. Mater. 2012;24(21):2824–2837. doi: 10.1002/adma.201104477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pritchard EM, Kaplan DL. Silk fibroin biomaterials for controlled release drug delivery. Expert Opin. Drug Delivery. 2011;8(6):797–811. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2011.568936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Elices M, et al. The hidden link between supercontraction and mechanical behavior of spider silks. J. Mech. Behavior Biomed. Mater. 2011;4(5):658–669. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Porter D, Vollrath F. Silk as a biomimetic ideal for structural polymers. Adv. Mater. 2009;21(4):487–492. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lefevre T, Paquet-Mercier F, Rioux-Dube J-F, Pezolet M. Structure of silk by raman spectromicroscopy: from the spinning glands to the fibers. Biopolymers. 2012;97(6):322–336. doi: 10.1002/bip.21712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Asakura T, Suzuki Y, Nakazawa Y, Holland GP, Yarger JL. Elucidating silk structure using solid-state NMR. Soft Matter. 2013;9(48):11440–11450. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang X, Kluge JA, Leisk GG, Kaplan DL. Sonication-induced gelation of silk fibroin for cell encapsulation. Biomaterials. 2008;29(8):1054–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rössle M, Panine P, Urban VS, Riekel C. Structural evolution of regenerated silk fibroin under shear: Combined wide-and small-angle X-ray scattering experiments using synchrotron radiation. Biopolymers. 2004;74(4):316–327. doi: 10.1002/bip.20083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sukigara S, et al. Regeneration of Bombyx mori silk by electrospinning—part 1: processing parameters and geometric properties. Polymer. 2003;44(19):5721–5727. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sukigara S, et al. Regeneration of Bombyx mori silk by electrospinning. Part 2. Process optimization and empirical modeling using response surface methodology. Polymer. 2004;45(11):3701–3708. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ayutsede J, et al. Regeneration of Bombyx mori silk by electrospinning. Part 3: characterization of electrospun nonwoven mat. Polymer. 2005;46(5):1625–1634. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Li C, et al. Electrospun silk-BMP-2 scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2006;27(16):3115–3124. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chronakis IS. Novel nanocomposites and nanoceramics based on polymer nanofibers using electrospinning process—a review. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2005;167(2):283–293. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jin HJ, et al. Water-Stable Silk Films with Reduced β-Sheet Content. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2005;15(8):1241–1247. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hu X, et al. Regulation of silk material structure by temperature-controlled water vapor annealing. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12(5):1686–1696. doi: 10.1021/bm200062a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nam J, Park YH. Morphology of regenerated silk fibroin: Effects of freezing temperature, alcohol addition, and molecular weight. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2001;81(12):3008–3021. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Breslauer D, Kaplan D. 9.04–Silks. In: Krzysztof M, Martin M, editors. Polymer Science: A Comprehensive Reference. Vol. 9. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2012. pp. 57–69. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Terry AE, et al. pH Induced Changes in the Rheology of Silk Fibroin Solution from the Middle Division of Bombyx m ori Silkworm. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5(3):768–772. doi: 10.1021/bm034381v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Foo CWP, et al. Role of pH and charge on silk protein assembly in insects and spiders. Appl. Phys. A: Mater. Sci. Process. 2006;82(2):223–233. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dicko C, Vollrath F, Kenney JM. Spider silk protein refolding is controlled by changing pH. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5(3):704–710. doi: 10.1021/bm034307c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhou P, et al. Effects of pH and calcium ions on the conformational transitions in silk fibroin using 2D Raman correlation spectroscopy and 13C solid-state NMR. Biochemistry. 2004;43(35):11302–11311. doi: 10.1021/bi049344i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kim U-J, et al. Structure and properties of silk hydrogels. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5(3):786–792. doi: 10.1021/bm0345460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Geddes A, Graham G, Morris H. Mass-spectrometric determination of the amino acid sequences in peptides isolated from protein silk fibroin of Bombyx mori. Biochem. J. 1969;114:695–702. doi: 10.1042/bj1140695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Arcidiacono S, et al. Purification and characterization of recombinant spider silk expressed in Escherichia coli. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1998;49(1):31–38. doi: 10.1007/s002530051133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Iizuka E, Yang JT. Optical rotatory dispersion and circular dichroism of the beta-form of silk fibroin in solution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1966;55(5):1175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.55.5.1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chen Y-H, Yang JT, Martinez HM. Determination of the secondary structures of proteins by circular dichroism and optical rotatory dispersion. Biochemistry. 1972;11(22):4120–4131. doi: 10.1021/bi00772a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Prince JT, et al. Construction, cloning, and expression of synthetic genes encoding spider dragline silk. Biochemistry. 1995;34(34):10879–10885. doi: 10.1021/bi00034a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Brahms S, et al. Identification of β, β-turns and unordered conformations in polypeptide chains by vacuum ultraviolet circular dichroism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1977;74(8):3208–3212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.8.3208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ochi A, et al. Rheology and dynamic light scattering of silk fibroin solution extracted from the middle division of Bombyx mori silkworm. Biomacromolecules. 2002;3(6):1187–1196. doi: 10.1021/bm020056g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Arcidiacono S, et al. Aqueous processing and fiber spinning of recombinant spider silks. Macromolecules. 2002;35(4):1262–1266. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chae SK, et al. Micro/Nanometer-scale fiber with highly ordered structures by mimicking the spinning process of silkworm. Adv. Mater. 2013;25(22):3071–3078. doi: 10.1002/adma.201300837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Luo J, et al. A bio-inspired microfluidic concentrator for regenerated silk fibroin solution. Sens. Actuators, B. 2012;162(1):435–440. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Luo J, et al. Tough silk fibers prepared in air using a biomimetic microfluidic chip. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014;66:319–324. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kinahan ME, et al. Tunable silk: using microfluidics to fabricate silk fibers with controllable properties. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12(5):1504–1511. doi: 10.1021/bm1014624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rammensee S, et al. Assembly mechanism of recombinant spider silk proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105(18):6590–6595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709246105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bettinger CJ, et al. Silk fibroin microfluidic devices. Adv. Mater. 2007;19(19):2847–2850. doi: 10.1002/adma.200602487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Martel A, et al. A microfluidic cell for studying the formation of regenerated silk by synchrotron radiation small-and wide-angle X-ray scattering. Biomicrofluidics. 2008;2(2):024104. doi: 10.1063/1.2943732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Elices M, et al. Bioinspired fibers follow the track of natural spider silk. Macromolecules. 2011;44(5):1166–1176. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tokareva OS, et al. Effect of sequence features on assembly of spider silk block copolymers. J. Struct. Biol. 2014;186(3):412–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Rabotyagova OS, Cebe P, Kaplan DL. Protein-based block copolymers. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12(2):269–289. doi: 10.1021/bm100928x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.van Hest JC, Tirrell DA. Protein-based materials, toward a new level of structural control. Chem. Commun. 2001;(19):1897–1904. doi: 10.1039/b105185g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Rabotyagova OS, Cebe P, Kaplan DL. Role of Polyalanine Domains in β-Sheet Formation in Spider Silk Block Copolymers. Macromol. Biosci. 2010;10(1):49–59. doi: 10.1002/mabi.200900203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Rabotyagova OS, Cebe P, Kaplan DL. Self-assembly of genetically engineered spider silk block copolymers. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10(2):229–236. doi: 10.1021/bm800930x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Tokareva O, Michalczechen-Lacerda VA, Rech EL, Kaplan DL, et al. Recombinant DNA production of spider silk proteins. Microbial biotechnology. 2013;6(6):651–663. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Rathore O, Sogah DY. Self-assembly of β-sheets into nanostructures by poly (alanine) segments incorporated in multiblock copolymers inspired by spider silk. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123(22):5231–5239. doi: 10.1021/ja004030d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Teulé F, et al. A protocol for the production of recombinant spider silk-like proteins for artificial fiber spinning. Nat. Protoc. 2009;4(3):341–355. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Krejchi MT, et al. Chemical sequence control of beta-sheet assembly in macromolecular crystals of periodic polypeptides. Science. 1994;265(5177):1427–1432. doi: 10.1126/science.8073284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Qu Y, et al. Self-assembly of a polypeptide multi-block copolymer modeled on dragline silk proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122(20):5014–5015. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Werten MW, et al. Biosynthesis of an amphiphilic silk-like polymer. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9(7):1705–1711. doi: 10.1021/bm701111z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Espinosa HD, et al. Merger of structure and material in nacre and bone–perspectives on de novo biomimetic materials. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2009;54(8):1059–1100. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Fratzl P, Weinkamer R. Nature’s hierarchical materials. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2007;52(8):1263–1334. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Meyers MA, et al. Biological materials: structure and mechanical properties. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2008;53(1):1–206. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Meyers MA, McKittrick J, Chen P-Y. Structural biological materials: critical mechanics-materials connections. Science. 2013;339(6121):773–779. doi: 10.1126/science.1220854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Bechtle S, Ang SF, Schneider GA. On the mechanical properties of hierarchically structured biological materials. Biomaterials. 2010;31(25):6378–6385. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Cranford S, Buehler MJ. Materiomics: biological protein materials, from nano to macro. Nanotechnol., Sci. Appl. 2010;3:127–148. doi: 10.2147/NSA.S9037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Bhushan B. Biomimetics: lessons from nature–an overview. Philos. Trans. R. Soc., A. 2009;367(1893):1445–1486. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2009.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Lin S, Ryu S, Tokareva O, Gronau G, Jacobsen MM, Huang W, Rizzo DJ, Li D, Staii C, Pugno NM. Predictive modelling-based design and experiments for synthesis and spinning of bioinspired silk fibres. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:6892. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Krasnov I, Diddens I, Hauptmann N, Helms G, Ogurreck M, Seydel T, Funari SS, Muller M. Mechanical properties of silk: interplay of deformation on macroscopic and molecular length scales. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008;100(4):048104. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.048104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Xiao S, et al. Mechanical response of silk crystalline units from force-distribution analysis. Biophys. J. 2009;96(10):3997–4005. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Mortimer B, et al. The speed of sound in silk: Linking material performance to biological function. Adv. Mater. 2014;26(30):5179–5183. doi: 10.1002/adma.201401027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Guan J, Porter D, Vollrath F. Thermally induced changes in dynamic mechanical properties of native silks. Biomacromolecules. 2013;14(3):930–937. doi: 10.1021/bm400012k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Bratzel G, Buehler MJ. Sequence-structure correlations in silk: Poly-Ala repeat of N. clavipes MaSp1 is naturally optimized at a critical length scale. J. Mech. Behavior Biomed. Mater. 2012;7:30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2011.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Cranford SW, et al. Nonlinear material behaviour of spider silk yields robust webs. Nature. 2012;482(7383):72–76. doi: 10.1038/nature10739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Keten S, Buehler MJ. Nanostructure and molecular mechanics of spider dragline silk protein assemblies. J. R. Soc., Interface. 2010;7:1709. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2010.0149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Keten S, et al. Nanoconfinement controls stiffness, strength and mechanical toughness of [beta]-sheet crystals in silk. Nat. Mater. 2010;9(4):359–367. doi: 10.1038/nmat2704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Nova A, et al. Molecular and nanostructural mechanisms of deformation, strength and toughness of spider silk fibrils. Nano Lett. 2010;10(7):2626–2634. doi: 10.1021/nl101341w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Tarakanova A, Buehler MJ. A materiomics approach to spider silk: protein molecules to webs. JOM. 2012;64(2):214–225. [Google Scholar]

- 137.Kaplan D, et al. Silk: biology, structure, properties, and genetics. Silk Polymers; ACS Symposium Series; American Chemical Society; Washington, D.C. 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 138.Omenetto F, Kaplan D. From silk cocoon to medical miracle. Sci. Am. 2010;303(5):76–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Hayashi CY, Shipley NH, Lewis RV. Hypotheses that correlate the sequence, structure, and mechanical properties of spider silk proteins. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 1999;24(2):271–275. doi: 10.1016/s0141-8130(98)00089-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Perea G, Riekel C, Guinea GV, Madurga R, Daza R, Burghammer M, Hayashi C, Elices M, Plaza GR, Perez-Rigueiro J. Identification and dynamics of polyglycine II nanocrystals in Argiope trifasciata flagelliform silk. Sci. Rep. 2013;3 doi: 10.1038/srep03061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Work RW. Dimensions, birefringences, and force-elongation behavior of major and minor ampullate silk fibers from orb-web-spinning spiders—the effects of wetting on these properties. Text. Res. J. 1977;47(10):650–662. [Google Scholar]

- 142.Bell FI, McEwen IJ, Viney C. Fibre science: Supercontraction stress in wet spider dragline. Nature. 2002;416(6876):37–37. doi: 10.1038/416037a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Gosline JM, Denny MW, DeMont ME. Spider silk as rubber. Nature. 1984;309(5968):551–552. [Google Scholar]

- 144.Blackledge TA, et al. How super is supercontraction? Persistent versus cyclic responses to humidity in spider dragline silk. J. Exp. Biol. 2009;212(13):1981–1989. doi: 10.1242/jeb.028944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Agnarsson I, et al. Spider silk as a novel high performance biomimetic muscle driven by humidity. J. Exp. Biol. 2009;212(13):1990–1994. doi: 10.1242/jeb.028282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Liu Y, Shao Z, Vollrath F. Relationships between supercontraction and mechanical properties of spider silk. Nat. Mater. 2005;4(12):901–905. doi: 10.1038/nmat1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Simmons AH, Michal CA, Jelinski LW. Molecular orientation and two-component nature of the crystalline fraction of spider dragline silk. Science. 1996;271(5245):84–87. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5245.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Yang Z, et al. Supercontraction and backbone dynamics in spider silk: 13C and 2H NMR studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122(37):9019–9025. [Google Scholar]

- 149.Giesa T, et al. Molecular origin of supercontraction in spider dragline silk revealed by simulation and experiment. 2015 in submission. [Google Scholar]

- 150.Zhang J, et al. Stabilization of vaccines and antibiotics in silk and eliminating the cold chain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109(30):11981–11986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206210109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 151.Fan H, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament regeneration using mesenchymal stem cells and silk scaffold in large animal model. Biomaterials. 2009;30(28):4967–4977. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Wang Y, et al. In vitro cartilage tissue engineering with 3D porous aqueous-derived silk scaffolds and mesenchymal stem cells. Biomaterials. 2005;26(34):7082–7094. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Vaezi M, Seitz H, Yang S. A review on 3D micro-additive manufacturing technologies. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology. 2013;67(5–8):1721–1754. [Google Scholar]

- 154.Yanagisawa S, et al. Improving cell-adhesive properties of recombinant Bombyx mori silk by incorporation of collagen or fibronectin derived peptides produced by transgenic silkworms. Biomacromolecules. 2007;8(11):3487–3492. doi: 10.1021/bm700646f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Chen JL, et al. Efficacy of hESC-MSCs in knitted silk-collagen scaffold for tendon tissue engineering and their roles. Biomaterials. 2010;31(36):9438–9451. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Fang Q, et al. In vitro and in vivo research on using Antheraea pernyi silk fibroin as tissue engineering tendon scaffolds. Mater. Sci. Eng., C. 2009;29(5):1527–1534. [Google Scholar]

- 157.Yang Y, et al. Biocompatibility evaluation of silk fibroin with peripheral nerve tissues and cells in vitro. Biomaterials. 2007;28(9):1643–1652. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Allmeling C, et al. Use of spider silk fibres as an innovative material in a biocompatible artificial nerve conduit. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2006;10(3):770–777. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2006.tb00436.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Allmeling C, et al. Spider silk fibres in artificial nerve constructs promote peripheral nerve regeneration. Cell Proliferation. 2008;41(3):408–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2008.00534.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Lovett M, et al. Silk fibroin microtubes for blood vessel engineering. Biomaterials. 2007;28(35):5271–5279. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Nakazawa Y, et al. Development of small-diameter vascular grafts based on silk fibroin fibers from Bombyx mori for vascular regeneration. J. Biomater. Sci., Polym. Ed. 2011;22(1–3):195–206. doi: 10.1163/092050609X12586381656530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Gomes S, et al. Spider silk-bone sialoprotein fusion proteins for bone tissue engineering. Soft Matter. 2011;7(10):4964–4973. [Google Scholar]

- 163.Sofia S, et al. Functionalized silk-based biomaterials for bone formation. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2001;54(1):139–148. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(200101)54:1<139::aid-jbm17>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Meinel L, Karageorgious V, Hofmann S, Fajardo R, Snyder B, Li C, Zichner L, Langer R, Vunjak-Novakovic G, Kaplan DL. Engineering bone-like tissue in vitro using human bone marrow stem cells and silk scaffolds. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2004;71(1):25–34. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Kim HJ, et al. Bone tissue engineering with premineralized silk scaffolds. Bone. 2008;42(6):1226–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Kong X, et al. Silk fibroin regulated mineralization of hydroxyapatite nanocrystals. J. Cryst. Growth. 2004;270(1):197–202. [Google Scholar]

- 167.Karageorgiou V, Tomkins M, Fajardo R, Meinel L, Snyder B, Wade K, Chen J, Vunjak-Novakovic G, Kaplan DL. Porous silk fibroin 3-D scaffolds for delivery of bone morphogenetic protein-2 in vitro and in vivo. J. Biomed. Mater. Res., Part A. 2006;78(2):324–334. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Widhe M, Johansson J, Rising A. Current progress and limitations of spider silk for biomedical applications. Biopolymers. 2012;97(6):468–478. doi: 10.1002/bip.21715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Leal-Egaña A, Scheibel T. Silk-based materials for biomedical applications. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2010;55(3):155–167. doi: 10.1042/BA20090229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Altman GH, et al. Silk-based biomaterials. Biomaterials. 2003;24(3):401–416. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00353-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Panilaitis B, et al. Macrophage responses to silk. Biomaterials. 2003;24(18):3079–3085. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00158-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Mathur AB, Gupta V. Silk fibroin-derived nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Nanomedicine. 2010;5(5):807–820. doi: 10.2217/nnm.10.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Liu H, Ge Z, Wang Y, Toh SL, Sutthikhum V, Goh JCH. Modification of sericin-free silk fibers for ligament tissue engineering application. J. Biomed. Mater. Res., Part B. 2007;82(1):129–138. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Gulrajani M, et al. Preparation and application of silver nanoparticles on silk for imparting antimicrobial properties. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2008;108(1):614–623. [Google Scholar]

- 175.Xu S, Yong L, Wu P. One-pot, green, rapid synthesis of flowerlike gold nanoparticles/reduced graphene oxide composite with regenerated silk fibroin as efficient oxygen reduction electrocatalysts. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2013;5(3):654–662. doi: 10.1021/am302076x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Wong JY, et al. Materials by design: merging proteins and music. Nano Today. 2012;7(6):488–495. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.Naraghi M, et al. A Multiscale Study of High Performance Double-Walled Nanotube– Polymer Fibers. ACS Nano. 2010;4(11):6463–6476. doi: 10.1021/nn101404u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Gronau G, et al. A review of combined experimental and computational procedures for assessing biopolymer structure–process–property relationships. Biomaterials. 2012;33(33):8240–8255. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.06.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Lin S, Ryu S, Tokareva O, Gronau G, Jacobsen MM, Huang W, Rizzo DJ, Li D, Staii C, Pugno NM. Predictive modelling-based design and experiments for synthesis and spinning of bioinspired silk fibres. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:6892. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180.Bratzel G, Buehler MJ. Molecular mechanics of silk nanostructures under varied mechanical loading. Biopolymers. 2012;97(6):408–417. doi: 10.1002/bip.21729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181.Rising A, et al. Spider silk proteins–mechanical property and gene sequence. Zool. Sci. 2005;22(3):273–281. doi: 10.2108/zsj.22.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182.Hinman MB, Jones JA, Lewis RV. Synthetic spider silk: a modular fiber. Trends Biotechnol. 2000;18(9):374–379. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(00)01481-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]