Abstract

HDAC4 is a potent memory repressor with overexpression of wild type or a nuclear-restricted mutant resulting in memory deficits. Interestingly, reduction of HDAC4 also impairs memory via an as yet unknown mechanism. Although histone deacetylase family members are important mediators of epigenetic mechanisms in neurons, HDAC4 is predominantly cytoplasmic in the brain and there is increasing evidence for interactions with nonhistone proteins, suggesting HDAC4 has roles beyond transcriptional regulation. To that end, we performed a genetic interaction screen in Drosophila and identified 26 genes that interacted with HDAC4, including Ubc9, the sole SUMO E2-conjugating enzyme. RNA interference-induced reduction of Ubc9 in the adult brain impaired long-term memory in the courtship suppression assay, a Drosophila model of associative memory. We also demonstrate that HDAC4 and Ubc9 interact genetically during memory formation, opening new avenues for investigating the mechanisms through which HDAC4 regulates memory formation and other neurological processes.

Keywords: histone deacetylase, SUMOylation, plasticity, neuron, memory

THE histone deacetylase HDAC4 is widely expressed in neurons throughout the brain (Darcy et al. 2010) and an increasing body of evidence indicates that HDAC4 plays important roles in neurological function (Kumar et al. 2005; Chen and Cepko 2009; Kim et al. 2012; Li et al. 2012; Sando et al. 2012; Sarkar et al. 2014). To that end, we recently demonstrated that in Drosophila, RNA interference (RNAi)-mediated knockdown of HDAC4 in the adult brain impairs long-term memory (LTM) in the courtship suppression assay, a model of associative memory (Fitzsimons et al. 2013). Similarly in humans, loss of one copy of HDAC4 correlates with brachydactyly mental retardation syndrome (BDMR), the neurological symptoms of which include intellectual disability and autism (Williams et al. 2010; Morris et al. 2012; Villavicencio-Lorini et al. 2013), and in mice, conditional knockout of HDAC4 in the brain results in impairments in hippocampal-dependent associative LTM (Kim et al. 2012). Despite this growing evidence of a critical role, the mechanism(s) through which HDAC4 positively influences LTM is unknown. This is in part because HDAC4 exists in both nuclear and cytoplasmic pools, and under basal conditions, the majority of HDAC4 is localized to the cytoplasm (Chawla et al. 2003; Darcy et al. 2010). Given the predominant nonnuclear localization, particularly the concentration of HDAC4 at dendritic spines (Darcy et al. 2010), we hypothesize that cytoplasmic HDAC4 is required in memory formation; however, the mechanisms through which HDAC4 acts outside the nucleus are unknown.

The nuclear role of HDAC4 is less of an enigma. When in the nucleus, HDAC4 acts as a transcriptional repressor; although vertebrate HDAC4 is catalytically inactive as a histone deacetylase, rather it facilitates changes in gene expression through direct binding and inhibition of transcription factors such as MEF2 (Miska et al. 1999; Wang et al. 1999; Lu et al. 2000). As described above, HDAC4 must be present for normal LTM; however, increased nuclear HDAC4 also impairs memory (Williams et al. 2010; Sando et al. 2012). An individual with BDMR was identified to carry a point mutation that resulted in a truncated HDAC4 protein (Williams et al. 2010), and further investigation of a similar HDAC4 variant in the mouse revealed a gain of function, with this truncated protein lacking a nuclear export signal and thus being sequestered in the nucleus. The truncated form of HDAC4 also caused cognitive deficits in mice, which were associated with reduced expression of plasticity-related genes (Sando et al. 2012). We also demonstrated that overexpression of HDAC4 in Drosophila resulted in impaired LTM and recruited MEF2 to discrete foci within nuclei (Fitzsimons et al. 2013). Taken together, these data indicate that when in the nucleus, HDAC4 has the capacity to repress expression of plasticity-related genes, which correlates with memory impairment (Sando et al. 2012); however, it also plays a promemory role, as evidenced by the memory impairments that result from reduction of HDAC4 in the adult brain (Kim et al. 2012; Fitzsimons et al. 2013).

Here, we sought to increase understanding of the molecular mechanisms through which HDAC4 regulates memory via a two-pronged approach. First, in order to investigate whether the memory deficits we observed following overexpression of HDAC4 were accompanied by alterations in gene expression, we performed RNA sequencing (RNAseq) on heads of flies that overexpressed HDAC4 in the adult brain; however, very few changes were found, suggesting that wild-type (WT) HDAC4 elicits limited transcriptional effects.

For our second approach, we sought to identify genes that interact with HDAC4 by making use of a rough eye enhancer/suppressor screen, which would capture both transcriptional and nontranscriptional interactions. Our results indicate that HDAC4 interacts with genes that are important for transcription, the cytoskeleton, and SUMOylation. This study thus provides several new avenues for investigation of the mechanisms through which HDAC4 regulates memory formation.

Materials and Methods

Fly strains

All flies were cultured on standard medium on a 12-hr light/dark cycle and maintained at a temperature of 25° unless otherwise indicated. The UAS-HDAC4OE transgenic line harbors a UAS upstream of WT Drosophila HDAC4 fused to an N-terminal FLAG-tag, as previously described (Fitzsimons et al. 2013). GMR-HDAC4 was generated by fusing HDAC4 directly under control of GMR by standard methods; human HDAC4 and 3SA were cloned into pUASTattB by standard methods. The UAS-HDAC4 and GMR-HDAC4 transgenic flies were generated by GenetiVision (Houston, TX), using the P2 injection strain (attP insertion site 3L68A4). elavc155-GAL4 (no. 458), GMR-GAL4 (no. 1104), ey-GAL4 (no. 5535), OK107-GAL4 (no. 854), and tub-GAL80ts (no. 7108) were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (Bloomington, IN). All were outcrossed into the w(CS10) background. The HDAC4::YFP protein trap strain CPTI-000077 (no. 115008) was obtained from the Kyoto Stock Center. The elav-GAL4; tub-GAL80ts and OK107-GAL4; tub-GAL80ts lines were generated via standard genetic crosses, as were GMR-GAL4; UAS-HDAC4OE and ey-GAL4; GMR-HDAC4. Transgenic RNAi lines containing an inducible UAS-RNAi construct targeted to a single protein-coding gene were obtained from the Vienna Drosophila Resource Center (VDRC). Control crosses were performed with reference strain in the appropriate genetic background [w(CS10) or w1118].

Transcriptome analysis

To express HDAC4 in the adult brain, UAS-HDAC4OE flies (Fitzsimons et al. 2013) were crossed to elav-GAL4; tub-GAL80ts flies and raised at the permissive temperature of 19°. w(CS10) flies crossed to elav-GAL4; tub-GAL80ts served as the control. Three days after eclosion, flies were transferred to 30° to induce HDAC4 expression. After 48 hr, three biological replicates (i.e., from three separate crosses) were snap frozen in a dry ice/ethanol bath and vortexed to remove the heads. Heads were collected over dry ice and RNA was extracted with TRIzol and purified with an RNeasy microarray tissue mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Whole heads were used in order to reduce variation from individual dissection of brains and this method has been successfully employed to analyze brain-specific changes in gene expression in Drosophila (Winbush et al. 2012). The high quality of the RNA was confirmed on a Bioanalyzer (Agilent). Illumina libraries were prepared with an Illumina RNA TruSeq kit and run on an Illumina HiSeq with three samples per lane (North Carolina State University Genomic Sciences Laboratory). Over 60 million 100-bp reads were obtained per sample, which were mapped to the Drosophila reference genome (release 5.41, FB2011_09; 15,438 predicted genes). The reads were mapped using TopHat and analyzed for reads alignment percentage and gene coverage (Trapnell et al. 2012). Data analysis was restricted to genes with fragment per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped (FPKM) value of at least 1.0 as employed by the ModENCODE Consortium and in other studies (Roy et al. 2010; Winbush et al. 2012). The Cufflinks pipeline, version 2.2.1 was used to assemble mapped reads into transcripts, estimate their abundances, and test for differential expression between samples (Trapnell et al. 2012). Assemblies resulting from Cufflinks analysis were merged together using the Cuffmerge utility, which is included in the Cufflinks package. The merged assemblies were provided to Cuffdiff, a program included in the Cufflinks package that tests the statistical significance of each observed change in expression between the samples. The statistical model used to evaluate changes assumes that the number of reads produced by each transcript is proportional to its abundance. The expression level of transcripts across the runs was normalized by the total number of mapping reads using the FPKM normalization method (Mortazavi et al. 2008; Trapnell et al. 2012). Cuffdiff implements a linear statistical model to estimate an assignment of abundance to each transcript. Fold changes, expressed in log2 scale, raw P-values, and adjusted Q-values were calculated by standard methods. Plots were generated using the CummeRbund tool, which analyzes the Cuffdiff data into the R statistical computing environment, helping visualize the data (R version 3.2.0). We observed that one of the three control samples displayed different FKPM distribution; therefore, we performed the analysis both including and excluding the control and we detected significant changes in transcript abundance in 32 genes, and 28 of these genes were still significantly differentially expressed when analyzed with all three controls.

Rough eye phenotype screen

All crosses were performed at 25°, unless otherwise stated. GMR-GAL4; HDAC4OE flies were crossed to each RNAi line and the eye phenotypes of progeny were assessed at ∼7 days of age. Eyes were examined under a stereomicroscope (Olympus SZX12, DP controller imaging software, manual exposure, ISO 200, zoom 108 mm, exposure time 1/20 sec). A semiquantitative scoring system was used to evaluate the rough eye phenotype by scoring bristles, ommatidia, pigmentation, and shape. GMR-GAL4 flies were also crossed to each RNAi line to assess the effect of knockdown of each target gene on the eye phenotype (in the absence of HDAC4 overexpression) and lines with more than a very mild rough eye were excluded. Similarly, ey-GAL4, GMR-HDAC4 flies were crossed to appropriate RNAi lines and the eye phenotype was compared to that of ey-GAL4-driven expression of each RNAi line.

Quantitative RT-qPCR

The efficiency of Ubc9 knockdown was examined by RT-qPCR. elav-GAL4/+; tub-GAL80ts/Ubc9kd flies and control elav-GAL4/+; tub-GAL80ts/+ flies were raised at the permissive temperature of 19° and then adults were shifted to the restrictive temperature of 30° for 48 hr. Flies were snap frozen and heads collected over dry ice, and then total RNA was extracted from ∼50 heads with TRIzol and quantified on a NanoDrop. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized with random primers (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and Transcriptor Reverse Transcriptase (Sigma-Aldrich). For PCR amplification, the following primers were used: Ubc9 5′-ATTTCCGCTAGCAGTCCCAC-3′ and 5′-TGCTTGGAACCACTGGAGAC-3′; and EF1a48D, 5′-ACTTTGTTCGAATCCGTCGC-3′ and 5′-TACGCTTGTCGATACCACCG-3′. PCR was performed with SsoFast EvaGreen supermix (BioRad) on a Roche Lightcycler 480 Instrument II (Roche) under standard cycling conditions. Both primer sets were confirmed to yield one major band of the correct size via agarose gel electrophoresis and melt curve analysis. Standard curves for each primer set were generated using fivefold dilutions of cDNA, and primer efficiency was between 95 and 105%. The comparative Ct method (also known as the 2-ΔΔCt method) was used to normalize Ubc9 transcript levels to those of the housekeeping gene EF1a48D. The 2-ΔΔCt of EF1a48D was set to 1. Data were collected from three independent RNA samples for each genotype, and significance was assessed by Mann–Whitney U-test, with the significance level set at P < 0.05.

Courtship suppression assay

The courtship suppression assay was performed as previously described (Fitzsimons and Scott 2011; Fitzsimons et al. 2013). Briefly, male flies to be tested were collected and housed in single vials for 4–6 days. For each experiment, control genotypes were tested at the same time as those expressing the RNAi. In all experiments, the scorer was blind to the genotype of the flies. All naïve and trained groups contained (n = 15–25) males. All experiments were performed under ambient light. For experiments using the TARGET system (McGuire et al. 2004), the temperature was modulated by placing flies at the permissive temperature of 19° (GAL80ts active) or the restrictive temperature of 30° (GAL80ts inactive), as appropriate. Unless otherwise indicated, for induction of transgene expression, flies were transferred to 30° 3 days prior to training to allow maximum GAL4-mediated expression of the UAS construct. Flies were trained at 30° in an incubator under white light and remained at 30° until 30 min before testing, at which time they were transferred to 25° for equilibration to the testing conditions. A courtship index (CI) was calculated as the percentage of the 10-min period spent in courtship behavior. In order to compare memory across genotypes, a memory index (MI) was calculated by dividing the courtship index (CI) of each test fly by the mean CI of the sham flies of the same genotype (CItest/mCIsham) (Mehren and Griffith 2004; Ejima et al. 2005, 2007). A score of 0 indicated the highest memory performance possible, and a score ≥1.0 indicated no memory. For statistical analyses, data were arcsine transformed in order to approximate a normal distribution and significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s honest significant difference (HSD) test or a Student’s t-test (two tailed, unpaired) with the significance level set at P < 0.05.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry on whole mount brains was performed as previously described (Fitzsimons et al. 2013). Brains were incubated overnight at room temperature with primary antibody (mouse anti-FasII, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, 1:100), and then incubated overnight at 4° with secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse Alexa555, 1:500; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and mounted with Antifade. For confocal microscopy, optical sections were taken with a Leica TCS SP5 DM6000B confocal microscope. Image stacks were taken at intervals of 1 μm and processed with Leica Application Suite Advanced Fluorescence (LAS AF) software.

Luciferase assay

Whole cell extracts were prepared from ∼50 snap-frozen heads by homogenizing heads in 1× Reporter Lysis Buffer (Promega, Madison, WI) with a disposable mortar and pestle, and then centrifuging at 12,000 × g for 5 min at 4°. A total of 2 µl of lysate was incubated in a well of a 96-well plate with 50 µl Bright Glo (Promega). Luminescence was measured on a POLARstar Omega microplate reader (BMG Labtech). All samples were assayed in triplicate.

Western blotting

Whole cell extracts were prepared from 50–100 snap-frozen heads by homogenizing heads in 50 μl of RIPA buffer ± 10 mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) with a disposable mortar and pestle, and then centrifuging at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4°. A total of 30 μg of each sample was loaded onto a 4–20% SDS-PAGE gel (BioRad) and resolved at 180 V. Protein was transferred onto nitrocellulose and blocked for >1 hr in 5% skim milk powder in TBST (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween-20, pH 7.6). The membrane was incubated overnight at 4° in primary antibody and 1 hr in secondary anti-mouse or anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated antibodies (GE Life Sciences) as appropriate. Antibodies used were rabbit anti-SUMO (kind gift from Albert Courey, University of California, Los Angeles; 1:5000) (Smith et al. 2004), rabbit anti-CaMKII (Cosmo Bio, 1:500), mouse anti-CREB (48H2 clone, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:1000), rabbit anti-MEF2 (kind gift from Bruce Paterson, 1:1000) (Lilly et al. 1995), and mouse anti-α-tubulin (12G10 clone, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, 1:500) obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and maintained by the University of Iowa, Department of Biology, Iowa City, IA. Detection was performed with Amersham ECL Select or ECL Plus (GE Life Sciences).

Immunoprecipitation

The HDAC4::EYFP fly strain (Cambridge Protein Trap Project) was used for immunoprecipitation (IP) of HDAC4. This consists of an artificial exon containing the EYFP gene flanked by splice acceptor and donor sequences, which is inserted into the endogenous HDAC4 gene, resulting in an internal incorporation of EYFP into the HDAC4 protein (Knowles-Barley et al. 2010; Fitzsimons et al. 2013). Whole cell extracts from ∼100 heads were prepared as per the Western blotting method above. IP was performed with the Pierce Classic IP Kit (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. One microliter of anti-GFP antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was incubated overnight with 600 μg of lysate. Following elution in 2× sample buffer, IP samples were processed for SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with anti-GFP (1:1000) or anti-SUMO (1:5000) antibodies alongside 30-μg input samples. Anti-α-tubulin (1:500) was used as a loading control.

Data availability

The authors state that all data necessary for confirming the conclusions presented in the article are represented fully within the article.

Results

Identification of HDAC4 gene targets in neurons

We initially sought to examine whether HDAC4 regulates transcription in the Drosophila brain and if so, to identify the specific gene targets. In order to compare transcript abundance between control and HDAC4-overexpressing flies, we expressed HDAC4 with the panneuronal elav driver (Robinow and White 1991) and induced expression in the adult brain with the TARGET system (McGuire et al. 2004). Analysis of differential expression confirmed that HDAC4 was significantly overexpressed by approximately twofold, but we did not observe global changes in gene expression. Thirteen genes (excluding HDAC4 and white, which was the selectable marker for transgenesis) were increased in abundance and 13 were decreased (Table 1). Of the putative HDAC4 transcriptional targets, few have been implicated in neurological functioning. The mammalian homolog of activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein 1 (Arc1) is an immediate-early gene that is essential for synaptic plasticity and long-term memory and its expression is positively regulated by MEF2 in neurons (Flavell et al. 2006); therefore, it is likely that HDAC4 reduces Arc1 expression by direct inhibition of MEF2. However Arc1 mutants did not display impaired synaptic plasticity in Drosophila (Mattaliano et al. 2007).

Table 1. Genes with transcripts that differ significantly in abundance on overexpression of HDAC4.

| FlyBase ID | Gene name | Log2 fold change | P-value | Q-value | Molecular function/biological process |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBgn0030773 | CG9676 | 1.17 | 5.00E-5 | 0.0160689 | Serine-type endopeptidase activity/proteolysis |

| FBgn0041210 | Histone deacetylase 4 | 1.09 | 5.00E-5 | 0.0160689 | Histone deacetylase activity/long-term memory; regulation of transcription, DNA templated |

| FBgn0041210 | CG11211 | 1.07 | 5.00E-5 | 0.0160689 | Carbohydrate binding; mannose binding/unknown |

| FBgn0040733 | CG15068 | 1.03 | 5.00E-5 | 0.0160689 | Unknown/unknown |

| FBgn0032507 | CG9377 | 0.95 | 5.00E-5 | 0.0160689 | Unknown/unknown |

| FBgn0026314 | UDP-glycosyltransferase 35b | 0.94 | 5.00E-5 | 0.0160689 | UDP glycosyltransferase activity, transferring hexosyl groups/UDP glucose metabolic process |

| FBgn0040502 | CG8343 | 0.89 | 5.00E-5 | 0.0160689 | Carbohydrate binding; mannose binding/unknown |

| FBgn0036022 | CG8329 | 0.84 | 5.00E-5 | 0.0160689 | Serine-type endopeptidase activity/proteolysis |

| FBgn0039800 | Niemann-Pick type C-2g | 0.80 | 5.00E-5 | 0.0160689 | Sterol binding/hemolymph coagulation; mesoderm development; sterol transport |

| FBgn0036015 | CG3088 | 0.71 | 5.00E-5 | 0.0160689 | Unknown/unknown |

| FBgn0013307 | Ornithine decarboxylase 1 | 0.69 | 5.00E-5 | 0.0160689 | Ornithine decarboxylase activity/polyamine biosynthetic process |

| FBgn0038516 | CG5840 | 0.68 | 5.00E-5 | 0.0160689 | Pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase activity/oxidation reduction process; proline biosynthetic process |

| FBgn0003996 | whitea | 0.67 | 5.00E-5 | 0.0160689 | Eye pigment precursor/eye pigment precursor transporter activity |

| FBgn0040606 | CG6503 | 0.67 | 5.00E-5 | 0.0160689 | Unknown/unknown |

| FBgn0052667 | Short spindle 7 | 0.66 | 5.00E-5 | 0.0160689 | Unknown/mitotic spindle assembly; multicellular organism reproduction |

| FBgn0039684 | Odorant-binding protein 99d | −1.68 | 5.00E-5 | 0.0160689 | Odorant binding/autophagic cell death, intermale aggressive behavior |

| FBgn0002565 | Larval serum protein 2 | −1.38 | 5.00E-5 | 0.0160689 | Nutrient reservoir activity/motor neuron axon guidance; synaptic target inhibition |

| FBgn0036659 | CG9701 | −1.35 | 5.00E-5 | 0.0160689 | Hydrolase activity, hydrolyzing O-glycosyl compounds/carbohydrate metabolic process |

| FBgn0027584 | CG4757 | −1.27 | 5.00E-5 | 0.0160689 | Carboxylic ester hydrolase activity/unknown |

| FBgn0037683 | CG18473 | −1.27 | 5.00E-5 | 0.0160689 | Aryldialkylphosphatase activity; hydrolase activity; zinc ion binding/catabolic process |

| FBgn0036106 | CG6409 | −0.90 | 5.00E-5 | 0.0160689 | Unknown/GPI anchor biosynthetic process |

| FBgn0002526 | Laminin A | −0.77 | 5.00E-5 | 0.0160689 | Receptor binding/axon guidance; brain morphogenesis, cell adhesion by integrin; intermale aggressive behavior; locomotion involved in locomotory behavior; negative regulation of synaptic growth at neuromuscular junction |

| FBgn0015400 | Kekkon-2 | −0.72 | 5.00E-5 | 0.0160689 | Unknown/unknown |

| FBgn0027843 | Carbonic anhydrase 2 | −0.71 | 5.00E-5 | 0.0160689 | Carbonate dehydratase activity; one carbon metabolic process |

| FBgn0033926 | Activity-regulated cytoskeleton associated protein 1 | −0.69 | 5.00E-5 | 0.0160689 | Nucleic acid binding/zinc ion binding; behavioral response to starvation; muscle system process |

| FBgn0034470 | Odorant-binding protein 56d | −0.68 | 5.00E-5 | 0.0160689 | Odorant binding/olfactory behavior; response to pheromone; sensory perception of chemical stimulus |

| FBgn0040211 | Homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase | −0.55 | 1.50E-4 | 0.0414082 | Homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase activity; L-phenylalanine catabolic process; oxidation-reduction process, tyrosine catabolic and metabolic process |

| FBgn0051205 | CG31205 | −0.54 | 1.50E-4 | 0.0414082 | Serine-type endopeptidase activity/proteolysis |

white was used as an eye color selectable marker and is differentially expressed in the HDAC4OE and control samples, with HDAC4OE flies harboring three copies of w+, in comparison to two in the control (genotypes: w[CS10],elav/+; GAL80ts/+; HDAC4OE/+ and w[CS10]elav/+; GAL80ts/+).

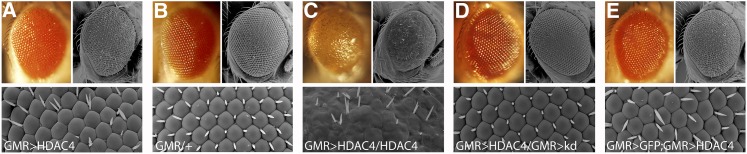

A screen for modifiers of the HDAC4-induced rough eye phenotype

As genetic screens can identify genes that interact through nontranscriptional mechanisms (Kaplow et al. 2007; Cao et al. 2008; Kim et al. 2010), and given that we detected minimal changes in gene expression at the transcriptional level, we elected to perform a rough eye enhancer genetic screen on a panel of RNAi lines. We observed that overexpression of HDAC4 in the eye with the glass multimer reporter driver (GMR-GAL4) (Freeman 1996) results in a rough eye phenotype, with disorganized ommatidia and bristles (Figure 1A) compared to the GMR-GAL4 control (Figure 1B). How increased HDAC4 specifically disrupts eye development is unknown; however, known HDAC4 interactors including MEF2, CREB, Gcn5, and 14-3-3ζ have been identified to play roles in the development of photoreceptors, which are specialized neurons (Kockel et al. 1997; Anderson et al. 2005; Andzelm et al. 2015). The severity of the phenotype correlated with the dose of HDAC4, as flies harboring two copies of UAS-HDAC4 displayed a severe phenotype, with fusion of most ommatidia, widespread bristle loss, and severely reduced pigmentation (Figure 1C). Thus the mild rough eye observed with one copy of UAS-HDAC4 provides an ideal system for screening for modifiers as it allows for easy identification of enhancers of this phenotype. Further, as expression is predominantly restricted to the eye, the flies are viable and fertile. When an inverted repeat RNAi targeted to HDAC4 was cointroduced with UAS-HDAC4, the eye phenotype was restored to WT (Figure 1D), confirming that the rough eye phenotype was a result of HDAC4 expression and not caused by nonspecific effects. As the presence of a second UAS line could theoretically decrease HDAC4 expression due to titration of GAL4, (rather than by a specific genetic interaction between HDAC4 and the RNAi-targeted gene), initial control experiments were undertaken to examine the effect of expressing a second UAS-driven construct on the rough eye phenotype. UAS-HDAC4 was coexpressed with either UAS-lacZ or UAS-EGFP, and neither of them altered the HDAC4 rough eye phenotype, confirming that the presence of a second UAS line does not itself alter the level of expression of HDAC4 (Figure 1E).

Figure 1.

Rough eye phenotypes associated with overexpression of HDAC4. Stereomicrographs and scanning electron micrographs of Drosophila eyes. (A) GMR-GAL4/+; UAS-HDAC4/+ flies display a mild rough eye phenotype. (B) This phenotype is not observed in control GMR-GAL4 heterozygotes. (C) A second copy of HDAC4 enhances the rough eye phenotype. (D) Coexpression of UAS-HDAC4 and an RNAi hairpin targeted to HDAC4 (kDa) restores with WT eye. (E) Coexpression of UAS-HDAC4 with a second UAS construct (GFP) does not alter the rough eye phenotype.

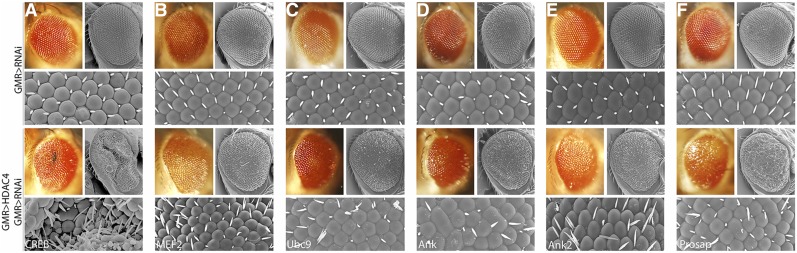

A candidate screen of RNAi lines available from VDRC was performed with the purpose of identifying modifiers of the HDAC4-induced phenotype. The RNAi lines to be included in the screen were chosen by mining literature and databases such as DroID (Murali et al. 2011). The criteria for selection included genes known to be involved in synaptic plasticity, memory, and/or neurological functioning, other chromatin modifiers, as well as genes with identified interactions with HDAC4 in other model systems and/or nonneuronal tissues (e.g., potential pleiotropic effectors). The RNAi lines were screened by scoring the eye phenotypes that resulted from coexpression with HDAC4. Eyes were scored semiquantitatively on the appearance of their bristles, pigmentation, and ommatidia. The eye phenotype resulting from GMR-driven expression of each RNAi line was also scored and lines with more than a very mild rough eye phenotype were excluded. Sixteen genes that are already known to interact with HDAC4 in other model systems or tissues were initially screened in order to identify interactions that are conserved between Drosophila and other species, as well as pleiotropic interactions in Drosophila (Supplemental Material, Table S1). Two genes, smt3 (SUMO) and nejire (Creb binding protein), were excluded, as they caused a rough eye phenotype when knocked down with GMR-GAL4. Of the remaining 14 genes, 8 enhanced the HDAC4 rough eye phenotype (Table 2), providing validation for the ability of the screen to detect interactions with HDAC4. These included the transcription factors CrebB and Mef2, the transcriptional corepressors Smrter and Sin3A, and the histone acetyl transferase Gcn5. We also observed interactions with the molecular chaperone 14-3-3ζ, the nucleoporin Nup358 (RanBP2), and the E2 SUMO-conjugating enzyme lwr (Ubc9). Examples of rough eye phenotypes are shown in Figure 2, A–C. The enhancement of the rough eye phenotype when these genes are knocked down strongly suggests that these interactions are also conserved in Drosophila.

Table 2. Genes previously identified to interact with hdac4 that also interact genetically with HDAC4 in Drosophila.

| Gene name | Annotation symbol | VDRC/BDSC no. | Method | Molecular function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gcn5 (PCAF) | CG4107 | VDRC 21786 | RNAi | H4 histone acetyltransferase activity; chromatin binding; H3 histone acetyltransferase activity; histone acetyltransferase activity. |

| Cyclic-AMP response element binding protein B | CG6103 | VDRC 101512 BDSC 29332 | RNAi RNAi | DNA binding; sequence-specific DNA binding transcription factor activity; protein dimerization activity; sequence-specific DNA binding. |

| Myocyte enhancer factor 2 | CG1429 | VDRC 15550 In house | RNAi Dom neg | Metalloendopeptidase activity; DNA binding; RNA polymerase II distal enhancer or core promoter proximal region sequence-specific DNA binding transcription factor activity involved in positive regulation of transcription; sequence-specific DNA binding transcription factor activity; protein dimerization activity; enhancer sequence-specific DNA binding. |

| 14-3-3ζ (leo) | CG17870 | VDRC 104496 | RNAi | Protein binding; protein domain specific binding; protein kinase C inhibitor activity; protein homodimerization activity; protein heterodimerization activity; tryptophan hydroxylase activator activity. |

| Smrter | CG4013 | VDRC 106701 | RNAi | DNA binding; chromatin binding; transcription corepressor activity; protein binding. |

| Lesswright (Ubc9) | CG3018 | VDRC 33685 BDSC 9318 | RNAi Dom neg | SUMO transferase activity; SUMO ligase activity; transcription factor binding; heat shock protein binding; ubiquitin activating enzyme binding. |

| Nup358 (RanBP2) | CG11856 | VDRC 38583 | RNAi | Zinc ion binding; Ran GTPase binding. |

| Sin3A | CG8815 | VDRC 105852 | RNAi | Sequence-specific DNA binding transcription factor activity; transcription cofactor activity; protein heterodimerization activity; chromatin binding. |

CG, computed gene name; VDRC/BDSC no., catalogue number from the Vienna Drosophila Resource Center or the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center; dom neg, dominant negative.

Figure 2.

Enhancers of the HDAC4 rough eye phenotype. (Top) Stereomicrographs and scanning electron micrographs of the eye phenotypes resulting from GMR-GAL4 induced expression of the RNAi lines only. (Bottom) Phenotypes resulting from coexpression of the RNAi and HDAC4. The phenotype due to GMR-GAL4-induced expression of one copy of HDAC4 was enhanced by coexpression of the RNAi targeted to (A) CrebB, (B) MEF2, (C) Ankyrin, (D) Ankyrin 2, (E) Ubc9, and (F) Prosap.

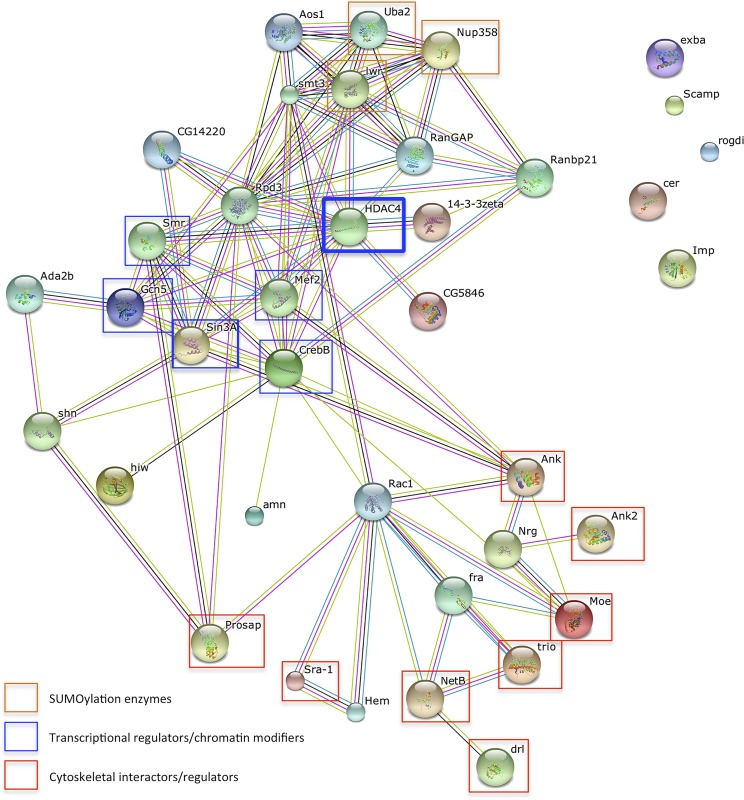

A further panel of 96 RNAi lines was then screened and 18 were found to enhance the HDAC4 rough eye phenotype (Table 3). Examples of eye phenotypes from interacting genes are shown in Figure 2, D–F. Additional RNAi lines targeted to different regions of the mRNA were tested for a subset of the genes to confirm the specificity of the knockdown (Table 3). We also screened a subset of genes we identified by RNAseq, which consisted of those that were expressed significantly in the brain (as assessed by a score of >10 on FlyAtlas); however, none of these 11 genes enhanced the HDAC4 rough eye phenotype (Table S1). An in-depth functional network analysis was then performed in order to identify subsets of genes with functions in common that could be used as an aid to guide further investigation. The Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes (STRING) database predicts physical and functional links between proteins and provides an integrated confidence score for the predicted associations (Franceschini et al. 2013; Szklarczyk et al. 2015); and furthermore, genes that represent real interactions, are more likely to connect in a network than false positives (Wang et al. 2009). STRING analysis of the 26 genes identified in our screen revealed potential mechanistic links between HDAC4 and genes encoding proteins with nuclear functions (Smr, Gcn5, Sin3A, and CrebB), proteins involved in SUMOylation (Nup358 and Ubc9), and proteins that interact with the cytoskeleton or influence cytoskeletal growth (Moesin, Ankyrin, Ankyrin 2, Netrin-B, trio, Sra-1, derailed, and Prosap) (Figure 3). In neurons, the latter group of genes also regulates axon and/or dendritic growth (Harris et al. 1996; Bonkowsky et al. 1999; Schenck et al. 2003; Lee et al. 2007; Briancon-Marjollet et al. 2008; Iyer et al. 2012; Siegenthaler et al. 2015; Yasunaga et al. 2015).

Table 3. Novel genes identified to interact with HDAC4 in Drosophila.

| Gene name | CG no. | VDRC no. | Molecular function/biological process |

|---|---|---|---|

| krasavietz | CG2922 | 102609 | Ribosome binding; translation initiation factor binding/axon midline choice point recognition; neuron fate commitment; positive regulation of filopodium assembly; behavioral response to ethanol; long-term memory; negative regulation of translation. |

| Prosap | CG30483 | 103592 21216 | GKAP/Homer scaffold activity; postsynaptic density assembly. |

| rogdi | CG7725 | 107310 | Unknown/learning or memory; behavioral response to ethanol; olfactory learning. |

| Ankyrin 2 | CG42734 | 107369 40638 | Cytoskeletal protein binding; structural constituent of cytoskeleton/neuromuscular junction development; short-term memory; positive regulation of synaptic growth at neuromuscular junction; negative regulation of neuromuscular synaptic transmission; axon extension. |

| CG5846 | CG5846 | 107793 | Unknown/unknown. |

| Moesin | CG10701 | 110654 | Cytoskeletal protein binding; protein binding; actin binding; phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate binding/actin filament-based process; sensory organ development. |

| Ankyrin | CG1651 | 25945 25946 | Cytoskeletal protein binding; structural constituent of cytoskeleton/cytoskeletal anchoring at plasma membrane; signal transduction. |

| RanBP21 | CG12234 | 31706 | Ran GTPase binding/intracellular protein transport. |

| trio | CG18214 | 40138 | Protein serine/threonine kinase activity; Rho guanyl-nucleotide exchange factor activity/actin filament-based process; regulation of neurogenesis; neuron differentiation. |

| Scamp | CG9195 | 9130 | Unknown/protein transport; long-term memory; neuromuscular synaptic transmission; synaptic vesicle exocytosis. |

| schnurri | CG7734 | 105643 | Sequence-specific DNA binding transcription factor activity; RNA polymerase II transcription coactivator activity/learning or memory; sensory organ development. |

| amnesiac | CG11937 | 5606 | G-protein coupled receptor binding; neuropeptide hormone activity/learning or memory; associative learning; thermosensory behavior. |

| Imp | CG1691 | 20321 | mRNA binding; nucleotide binding/nervous system development; mRNA splicing, via spliceosome; synaptic growth at neuromuscular junction. |

| Netrin-B | CG10521 | 100840 | Unknown/motor neuron axon guidance; regulation of photoreceptor cell axon guidance; dendrite guidance; synaptic target attraction; glial cell migration; synaptic target recognition; axon guidance. |

| derailed | CG17348 | 27053 | Serine-threonine/tyrosine-protein kinase/protein tyrosine kinase activity; transmembrane receptor protein tyrosine kinase activity. |

| crammer | CG10460 | 22752 | Cysteine-type peptidase activity; cysteine-type endopeptidase inhibitor activity/short-term memory; inhibition of cysteine-type endopeptidase activity; long-term memory. |

| Sra-1 | CG4931 | 108876 | Rho GTPase binding; cell morphogenesis; axon guidance; regulation of cell shape; cell projection assembly; cortical actin cytoskeleton organization; regulation of synapse organization; cell adhesion mediated by integrin; phagocytosis; compound eye morphogenesis. |

| highwire | CG32592 | 26998 | Ubiquitin-protein transferase activity; protein binding; zinc ion binding; single-organism process; regulation of synapse assembly; regulation of synaptic growth at neuromuscular junction; regulation of growth; metabolic process; response to axon injury; cellular metabolic process; regulation of metabolic process; regulation of signal transduction; cellular protein metabolic process; locomotion. |

Figure 3.

STRING network analysis of genes identified in the rough eye screen. Functional network analysis was performed using the STRING database, which integrates known and predicted interactions to construct and visualize protein interaction networks. Each edge represents a known or predicted interaction. Analysis of the 26 genes revealed several classes of genes that interacted with HDAC4. HDAC4 is highlighted by a bold blue rectangle. Orange, blue, and red rectangles highlight genes identified in the screen that are involved in SUMOylation, chromatin modification/transcriptional regulation, and regulation of the actin cytoskeleton, respectively.

HDAC4 interacts with the SUMOylation machinery

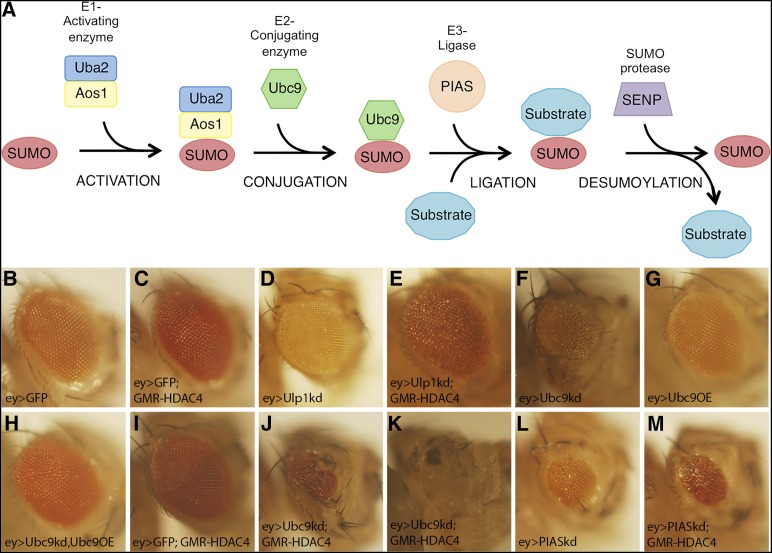

We chose to initially focus on the interaction between HDAC4 and Ubc9, the sole E2-conjugating enzyme in the SUMOylation pathway. SUMOylation is a process by which a small SUMO peptide is conjugated to a protein substrate (Figure 4A). It is a similar process to ubiquitination; however, rather than targeting the protein for degradation, the conjugation of SUMO alters properties of the substrate protein such as activity, stability, or subcellular localization (Wilkinson et al. 2010). The genes encoding the SUMOylation machinery are conserved in Drosophila (Long and Griffith 2000; Talamillo et al. 2008) and the SUMOylation machinery is enriched in fly heads (Long and Griffith 2000). SUMOylation is dependent on the presence of Ubc9 (Bhaskar et al. 2000), and Ubc9 mutants display impaired SUMOylation of substrates (Miles et al. 2008). The genetic interaction between HDAC4 and Ubc9 was particularly interesting as a growing body of evidence indicates that SUMOylation is an important mechanism for regulation of neuronal protein activity (Henley et al. 2014) and for regulation of memory formation (Yang et al. 2012; Castro-Gomez et al. 2013; Luo et al. 2013; Chen et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2014; Drisaldi et al. 2015). Moreover, HDAC4 has also been implicated as a putative E3 SUMO ligase, as its presence enhances the SUMOylation of MEF2 (Gregoire and Yang 2005; Zhao et al. 2005) and of the androgen receptor (Yang et al. 2011) in mammalian cells. To further explore the link between HDAC4 and SUMOylation, we investigated the interaction of HDAC4 with Ubc9 and other members of the SUMOylation machinery (Table 4). We found that a dominant negative mutant of Ubc9 also enhanced the HDAC4 eye phenotype. In addition, Ubc9 interacted with a catalytically inactive mutant of HDAC4, H968A, in which a histidine residue in the active site is replaced with an alanine (Wang et al. 1999; Huang et al. 2000; Cohen et al. 2009; Fitzsimons et al. 2013), indicating that this interaction is not dependent on deacetylase activity (Table S1). Ulp1, the SUMO protease, also enhanced the HDAC4 phenotype, as did the E1-conjugating enzyme Uba2 and the E3 SUMO ligase PIAS (also known as Su(var)2-10). Notably, the nucleoporin RanBP2, which we identified as an HDAC4 interactor, is also an E3 SUMO ligase. The only component of the core SUMOylation machinery that we did not detect an interaction with was the E1-conjugating enzyme subunit Aos1.

Figure 4.

SUMOylation genes enhance the HDAC4 rough eye phenotype. (A) Schematic showing the process of SUMOylation and deSUMOylation of a target protein. (B–M) Stereomicrographs of Drosophila eyes. Flies in B–E were raised at 30° and flies in F–M were raised at 22°. (B) Ey-GAL4-induced expression of GFP does not affect eye development. (C) GMR-HDAC4 results in a mild rough eye phenotype at 30°. (D) Knockdown of Ulp1 has no effect on eye development. (E) Coexpression of Ulp1 and HDAC4 results in a severe rough eye phenotype. (F) Ey-induced expression of Ubc9 RNAi results in a small rough eye. (G) Expression of Ubc9 does not affect eye development. (H) Ubc9 overexpression rescues the Ubc9 RNAi eye phenotype. (I) Eyes appear normal when GMR-HDAC4 is expressed at 25°. (J and K) Coexpression of ey > Ubc9 and GMR-HDAC4 enhances the HDAC4 eye phenotype, sometimes causing complete loss of the eye. (L) Eye-driven expression of PIAS RNAi impairs eye development. (M) This phenotype is significantly enhanced by GMR-HDAC4.

Table 4. Genes that encode components of the SUMOylation machinery and their effect on the HDAC4-induced rough eye phenotype.

| Gene name | Annotation symbol | VDRC/BDSC no. | Method | Molecular function | REP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesswright (Ubc9) | CG3018 | VDRC 33685 BDSC 9318 | RNAi Dom neg | SUMO ligase activity; transcription factor binding; heat shock protein binding; ubiquitin-activating enzyme binding. | E/E |

| Nucleoporin 358 kDa (RanBP2) | CG11856 | VDRC 38583 | RNAi | Zinc ion binding; Ran GTPase binding. | E/N |

| Ulp1 | CG12359 | VDRC 31744 | RNAi | SUMO-specific protease activity; protein binding. | E/E |

| Uba2 | CG7528 | VDRC 110173 | RNAi | SUMO-activating enzyme activity; small protein activating enzyme activity; ubiquitin-activating enzyme binding; ubiquitin-activating enzyme activity. | E/Ex |

| Activator of SUMO 1 | CG12276 | VDRC 47256 | RNAi | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme binding; ubiquitin-activating enzyme binding; small protein activating enzyme activity; SUMO-activating enzyme activity. | N/Ex |

| Suppressor of variegation 2-10 (PIAS) | CG8068 | VDRC 30709 | RNAi | Zinc ion binding; DNA binding; DEAD/H-box RNA helicase binding. | E/E |

The REP results are shown for each RNAi line tested in combination with UAS-HDAC4; GMR-GAL4 and GMR-HDAC4; ey-GAL4, respectively, separated with a backslash. Uba2 and Aos1 were unable to be tested in the GMR-HDAC4; ey-GAL4 screen as RNAi expression in combination with GMR-HDAC4 was lethal. REP, rough eye phenotype; Dom neg, dominant negative mutant; E, enhancer of rough eye phenotype; N, no effect on rough eye phenotype; Ex, excluded.

Although the control GMR-GAL4 heterozygote did not have a visible eye phenotype, it has been previously reported that when driven by GMR at high levels, GAL4 can itself impair eye development. To validate that the phenotype was not due to an interaction with GMR-GAL4, we circumvented the use of GMR-GAL4 by generating flies in which the GMR enhancer directly drives HDAC4 in the eye (GMR-HDAC4). Additionally, expression of RNAi lines was driven by GAL4 under control of the eyeless (ey) enhancer rather than the GMR enhancer–promoter (Hazelett et al. 1998). Ey drives expression of GAL4 primarily anterior to the morphogenetic furrow in eye disc and GMR-driven expression is predominantly posterior to the furrow; however, there is some overlap (Cao et al. 2008). Thus in flies that carry GMR-HDAC4, ey-GAL4, and UAS-RNAi, only a fraction of the eye cells would coexpress HDAC4 and GAL4 (and the regulated RNAi). The limited coexpression would increase the chance of false negatives; however, an advantage of employing ey-GAL4 is that since heterozygous ey-GAL4 flies have normal eye development (Figure 4B), the temperature can be raised to 30° to enhance GAL4 activity and therefore RNAi expression. At 30° GMR-HDAC4 heterozygotes displayed a minimal rough eye phenotype (Figure 4C). Knockdown of the SUMO protease Ulp1 had no effect on eye development by itself (Figure 4D), but noticeably enhanced the GMR-HDAC4 phenotype (Figure 4E). Knockdown of Ubc9 with ey-GAL4 was lethal at 30°; however, at 22° there were some survivors with severely reduced eyes (Figure 4F). This was not due to an off-target effect, as the eye deficits resulting from knockdown of Ubc9 were largely rescued by coexpression of Ubc9 (Ubc9OE) (Figure 4H). Ey-GAL4 driven expression of Ubc9 alone did not appreciably affect eye development (Figure 4G). GMR-HDAC4 heterozygotes displayed almost WT eyes at 22° (Figure 4I); however, coexpression with Ubc9 resulted in a very severe rough eye (Figure 4J) and in some cases, complete loss of the eye (Figure 4K), indicating a genetic interaction between HDAC4 and Ubc9. Similarly, knockdown of the E3 ligase PIAS was semilethal, with survivors displaying rough eyes that were reduced in size (Figure 4L). Coexpression of HDAC4 resulted in a more severe phenotype with necrotic patches (Figure 4M). A summary of the HDAC4 eye phenotypes resulting from knockdown of the SUMOylation machinery genes with GMR-GAL4 and ey-GAL4 is provided in Table 4.

Ubc9 is required for LTM

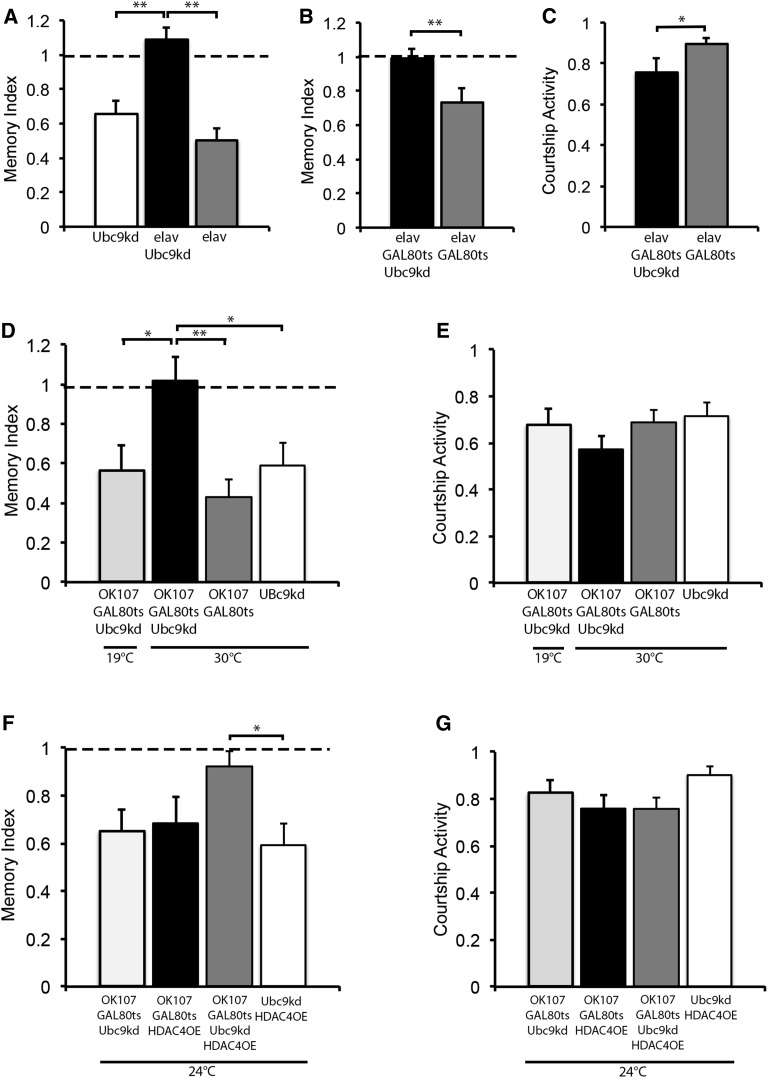

In a proof-of-principle experiment to determine whether SUMOylation is required for LTM in Drosophila, we knocked down Ubc9 panneuronally with the elav driver, which was confirmed by RT-qPCR (Figure S1), and assessed 24-hr memory using the courtship suppression assay. In this assay, a male fly is exposed to a freshly mated nonresponsive female and his ability to remember this rejection behavior is measured as a reduction in courtship toward subsequent females. Flies with intact memory will form a robust LTM that is stable for at least 24 hr following a 7-hr training session (Keleman et al. 2007; Fitzsimons and Scott 2011). Memory is calculated by dividing the CI of each male fly of the test genotype by the mean CI of the sham flies of the test genotype that received no training (CItrained/mCIsham), allowing comparison of memory between genotypes (Mehren and Griffith 2004; Ejima et al. 2005, 2007). A score of 0 indicates the highest memory performance possible, and a score of ≥1.0 indicates performance similar to untrained sham controls. LTM was completely disrupted in flies with reduced Ubc9 (Figure 5A). Immunohistochemistry against Fasciclin II, which is expressed in the α-, β-, and γ-lobes of the mushroom body (MB) and allows visualization of the gross MB structure, did not reveal any obvious deficits in brain development; however, when we elevated the temperature from 25° to 30°, which results in higher GAL4 activity, we did observe deficits in α- and β-lobe development (Figure S1). Therefore to dissociate an effect on brain development from a specific role in the adult brain, the TARGET system was used to restrict Ubc9 knockdown to adulthood. Flies were raised at the permissive temperature of 19°, then transferred to 30° to induce RNAi expression at 3 days posteclosion, and were trained after 48 hr at 30°. These flies were also severely impaired, with 24-hr memory scores similar to untrained controls (Figure 5B), indicating a nondevelopmental impairment in LTM. However analysis of courtship activity revealed that Ubc9 knockdown flies also displayed a small but significant reduction in courtship activity (Figure 5C), which confounded this analysis as the decreased courtship may alter the flies’ ability to form a memory. We therefore elected use of the OK107 driver to restrict Ubc9 knockdown largely to the MB (Aso et al. 2009; Fitzsimons and Scott 2011). This is a critical brain region for long-term courtship memory (McBride et al. 1999; Keleman et al. 2007) but is dispensable for courtship activity (McBride et al. 1999). Induction of Ubc9 knockdown in the adult MB had no effect on naïve courtship compared to controls (Figure 5E). Flies of the same genotype in which Ubc9 RNAi was not induced (e.g., raised and maintained at 19°) displayed normal LTM, whereas those in which Ubc9 knockdown was induced in adulthood were deficient in LTM formation (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

Knockdown of Ubc9 impairs LTM. (A) Knockdown of Ubc9 throughout development with elav-GAL4 resulted in a significant impairment in 24-hr LTM compared to control genotypes (ANOVA, post hoc Tukey’s HSD, ** P < 0.01). (B) Flies were raised to adulthood at 19° and switched to 30° 3 days prior to testing at 25° in order to induce expression of the Ubc9 RNAi. Twenty-four hour LTM was significantly impaired (Student’s t-test, two tailed, unpaired, ** P < 0.01). (C) There was also a significant reduction in courtship activity in these flies (Student’s t-test, two tailed, unpaired, *P < 0.05). (D) Flies with OK107-GAL4 driving Ubc9 RNAi under control of the TARGET system had normal memory in the uninduced state (raised at 19°); however, memory was abolished when gene expression was induced at 30°. (ANOVA, post hoc Tukey’s HSD, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01). (E) Courtship activity was unaffected by knockdown of Ubc9 in the adult brain with OK107-GAL4. (F) Flies were raised at 19° and then incubated at 24° for 72 hr. The combination of Ubc9 knockdown and HDAC4 overexpression resulted in a specific impairment in LTM compared to the control (ANOVA, post hoc Tukey’s HSD, * P < 0.05). (G) Courtship activity was unaffected. Full genotype abbreviations are as follows: Ubc9kd, UAS-Ubc9kd/+; elav, elav-GAL4/Y; elav Ubc9kd, elav-GAL4/Y;UAS-Ubc9kd/+; elav GAL80ts Ubc9, elav-GAL4/Y;UAS-Ubc9kd/tub-GAL80ts; elav GAL80ts, elav-GAL4/Y;tub-GAL80ts/+; OK107 GAL80ts Ubc9kd, tub-GAL80ts/UAS-Ubc9kd;OK107-GAL4/+;OK107 GAL80ts, tub-GAL80ts/+;OK107-GAL4/+; OK107 GAL80ts HDAC4OE, tub-GAL80ts/+;UAS-HDAC4OE/+;OK107-GAL4/+; and OK107 GAL80ts Ubc9kd HDAC4OE, tub-GAL80ts/UAS-Ubc9kd;UAS-HDAC4OE/+;OK107-GAL4/+.

HDAC4 and Ubc9 interact during LTM formation

Taken together, these data indicate that HDAC4 interacts with the SUMOylation machinery, and depletion of the E2 SUMO-conjugating enzyme in the adult MB prevents LTM formation. Since overexpression of HDAC4 in the MB also results in impaired LTM (Fitzsimons et al. 2013), we therefore sought to determine whether this interaction is important for normal memory formation. As the TARGET system is temperature sensitive, we reasoned that lowering expression of HDAC4 and Ubc9 RNAi by approximately half may provide a scenario in which there was insufficient expression to impair LTM, which would allow assessment of a genetic interaction between the two genes. We found that at 24°, expression of the quantitative reporter luciferase was induced to half the maximal expression obtained at 30° (Figure S2). We raised flies at 19° and then incubated individual males of each genotype at 24° for 3 days. Males expressing Ubc9 RNAi or HDAC4 did develop LTM although the memory indices were lower than controls (Figure 5F). Expression of both Ubc9 RNAi and HDAC4 together resulted in a significant impairment in memory compared to the control group (Figure 5F), and there was no significant difference in courtship activity between the groups (Figure 5G). Therefore, these data provide further evidence that HDAC4 and Ubc9 interact during LTM.

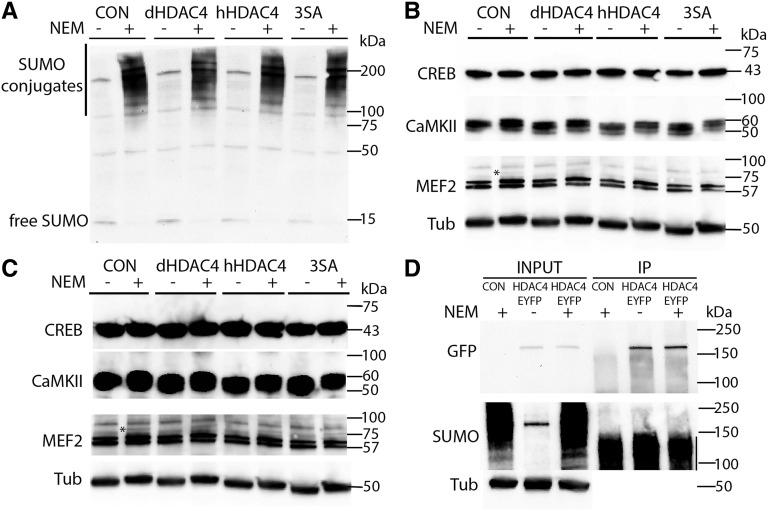

We next sought to determine if HDAC4 alters protein SUMOylation in Drosophila. In WT head extracts, high molecular weight SUMOylated proteins are observed as a smear in the presence of NEM, which inhibits the deconjugating activity of SUMO protease (Figure 6A, compare control lanes ± NEM), as previously characterized (Kanakousaki and Gibson 2012). We did not observe a global change in the abundance or molecular weights of SUMOylated conjugates following panneuronal overexpression of HDAC4 (Figure 6A, compare control and dHDAC4 lanes). This may indicate that HDAC4 influences the SUMOylation state of a limited number of targets. Thus we next examined the impact of HDAC4 overexpression on the SUMOylation of candidate proteins CaMKII, MEF2, and CREB, neuronal proteins that are involved in memory formation (Mehren and Griffith 2004; Barbosa et al. 2008; Cole et al. 2012; Tubon et al. 2013), which also have been demonstrated to interact physically with HDAC4 (Miska et al. 1999; McKinsey et al. 2000; Backs et al. 2008; Li et al. 2012), and are SUMO substrates (Long and Griffith 2000; Gregoire and Yang 2005; Zhao et al. 2005; Chen et al. 2014). However, we did not observe any species indicative of a SUMOylated form of CREB or CaMKII with standard (Figure 6B) or long exposures (Figure 6C). When probed with anti-MEF2, the samples treated with NEM did contain an additional band ∼15–20 kDa larger, which could indicate a SUMOylated form (Bhaskar et al. 2000). However the abundance of this higher molecular weight form was not altered by overexpression of HDAC4. Given that a high proportion of SUMOylated proteins are nuclear (Hendriks et al. 2014), we also generated transgenic flies harboring a nuclear-restricted phosphomutant of human HDAC4 (3SA) that is unable to exit the nucleus (Grozinger and Schreiber 2000; Chawla et al. 2003). However, neither 3SA nor WT human HDAC4 altered the SUMOylation profile of proteins extracted from fly heads (Figure 6A). Lastly, we examined whether the interaction with the SUMOylation machinery might indicate SUMOylation of HDAC4 itself. However, following IP of HDAC4::EYFP (an internal fusion of EYFP into the endogenous HDAC4 protein) (Knowles-Barley et al. 2010), a SUMOylated form of HDAC4 was not detected (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

Assessment of SUMOylation of proteins in whole cell lysates of Drosophila heads. (A) Whole cell lysates were prepared from fly heads in which elav-driven expression of Drosophila HDAC4, human HDAC4, or a nuclear-restricted mutant of human HDAC4 (3SA) were induced in adulthood with the TARGET system. Lysates were prepared ± 10 mM NEM, which inhibits SUMO protease. Free SUMO is observed in the absence of NEM, whereas SUMO conjugates are observed in the presence of 10 mM NEM. There were no obvious differences in SUMOylation profiles in any of the HDAC4-overexpressing samples in comparison to the control. (B) The same samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and probed with anti-MEF2, CaMKII, and CREB. Asterisk indicates a protein species only present in samples +NEM. Tubulin was used as a loading control. (C) Long exposure of B. (D) IP of HDAC4. Whole cell lysates from heads of HDAC4::EYFP (± 10 mM NEM) and WT control (+10 mM NEM) flies were immunoprecipitated with anti-GFP and processed for SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with the antibodies indicated on the left of the blots. Input HDAC4::EYFP samples show a band of the expected size of ∼170 kDa that is not present in the control. Control and HDAC4::EYFP input samples processed with NEM display a profile of SUMOylated proteins (as seen in A). Following IP, the HDAC4::EYFP band is detected with anti-GFP; however, a product of ∼190 kDa that would indicate a SUMOylated form of HDAC4::EYFP is not detected with the anti-SUMO antibody. The vertical line indicates the smear in the IP lanes, which is signal originating from the IgG heavy chain that is detected at high levels due to the very long exposure.

Discussion

We sought to progress our understanding of the mechanisms through which HDAC4 regulates memory by analysis of both transcriptional changes resulting from genetic manipulation of HDAC4 and identification of genes that interact genetically with HDAC4. We detected very few changes in transcription induced by overexpression of HDAC4; indeed the gene for which transcript abundance increased the most was HDAC4 itself. This lack of HDAC4-induced transcriptional changes is consistent with recent studies in the mouse in which manipulation of WT HDAC4 expression did not result in significant alteration of the transcriptome (Kim et al. 2012; Mielcarek et al. 2013), providing further support for the hypothesis that WT HDAC4 has a minimal effect on transcription. An alternative explanation for the lack of transcriptional changes could be that HDAC4 does not engage with the endogenous transcriptional machinery; however, we believe this to be less likely, as we have previously shown that when overexpressed in the mushroom body, HDAC4 induces redistribution of the transcription factor MEF2 into HDAC4-positive punctate nuclear foci (Fitzsimons et al. 2013). The lack of transcriptional changes also does not exclude the possibility that HDAC4 regulates local changes in gene expression in a subset of nuclei that are not detectable by whole head transcriptome analyses. Indeed, a nuclear-restricted HDAC4 mutant resulted in changes in transcript abundance of a subset of genes in primary cortical neurons that was enriched for genes involved in synaptic function (Sando et al. 2012). Further, we found genetic interactions between HDAC4 and known gene regulators (see below). Thus it could be worthwhile to use the INTACT technique (Deal and Henikoff 2011; Henry et al. 2012) to investigate HDAC4-dependent gene expression changes in specific neurons in the adult brain (e.g., Kenyon cells). However, given the largely nonnuclear subcellular localization of both mammalian (Darcy et al. 2010) and Drosophila HDAC4 (Fitzsimons et al. 2013), and the impairment in memory that results from reduction of HDAC4, we have proposed that the presence of HDAC4 is also required for normal memory formation through nontranscriptional mechanisms (Fitzsimons 2015). This led us to extend our search beyond differential gene expression and perform a rough eye screen to identify genes that enhance the HDAC4-induced rough eye phenotype.

We identified 26 genes that interacted with HDAC4 and many of these genes could be classed into the three broad categories of transcriptional regulators/chromatin modifiers, cytoskeletal interactors/regulators, and components of the SUMOylation machinery. Several of the transcriptional regulators have previously been identified to interact with HDAC4 in mammalian cells. A physical interaction between HDAC4 and MEF2, which results in repression of MEF2 activity, has been well documented (Miska et al. 1999; Wang et al. 1999; Lu et al. 2000; Fitzsimons et al. 2013). Similarly, HDAC4 also binds to and inhibits CREB in mouse brain (Li et al. 2012). We also confirmed that HDAC4 interacts with the transcriptional corepressor Smrter, the Drosophila ortholog of human SMRT, which requires HDAC4 binding for its corepressor activity (Huang et al. 2000; Fischle et al. 2002). The enhancement of the HDAC4 rough eye phenotype when these genes are knocked down strongly suggests that these interactions are also conserved in Drosophila neurons. We also identified putative novel interactions with transcriptional regulators schnurri and rogdi, which were both previously identified in a screen for Drosophila olfactory memory mutants, with transposon insertions in both of the genes resulting in severely impaired 24-hr memory, without affecting learning (Dubnau et al. 2003).

We also identified a number of genes encoding proteins that interact with or regulate the actin cytoskeleton, including trio, Sra-1, Prosap, Netrin-B, krasavietz, Moesin, Ankyrin 2, and Ankyrin. This is of particular interest as activity-dependent reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton occurs during growth of dendritic spines, which are thought to represent the structural changes that underpin the formation of new memories (Engert and Bonhoeffer 1999; Holtmaat and Svoboda 2009; Yang et al. 2009). Several of these genes including trio (Iyer et al. 2012; Shivalkar and Giniger 2012), Netrin B (Harris et al. 1996; Mitchell et al. 1996), krasavietz (Lee et al. 2007; Sanchez-Soriano et al. 2009), and Ankyrin 2 (Siegenthaler et al. 2015) regulate axon and/or dendrite growth in Drosophila. Moreover, krasavietz (Dubnau et al. 2003) and Ankyrin 2 (Iqbal et al. 2013) are also required for memory formation. Axon and dendritic growth and branching can easily be visualized and assessed in Drosophila (Leiss et al. 2009; Goossens et al. 2011), which will facilitate investigation of the relationships between these genes and HDAC4.

As HDAC4 has also been shown to modulate SUMOylation, and accumulating evidence indicates that regulation of SUMOylation is an important mechanism for synaptic plasticity, we chose to initially focus our attention on the HDAC4-Ubc9 interaction. Although SUMOylation has been most studied in the nucleus, the SUMOylation machinery also operates at extranuclear locations, including at synapses (Loriol et al. 2012) where it is dynamically regulated in response to synaptic activity, resulting in transient reduction of SUMOylated proteins at synaptosomes (Loriol et al. 2013). The list of neuronal proteins known to be SUMOylated is rapidly rising (Chao et al. 2008; Chamberlain et al. 2012; Cheng et al. 2014; for review see Henley et al. 2014) and this modification can have dramatic effects on function, e.g., SUMOylation of an isoform of CREB resulted in increased BDNF expression in the mouse hippocampus, and was associated with enhanced spatial memory in the mouse (Chen et al. 2014). The prion-like cytoplasmic polyadenylation element-binding protein (CPEB3) regulates the activity-dependent translation of dormant messenger RNAs (mRNAs) at the synapse, which are required for maintenance of LTM (Kandel et al. 2014) and this process is regulated by SUMOylation. Formation of the insoluble prion-like form of CPEB3 is required for its activity, and this aggregation is inhibited by SUMOylation; thus when SUMOylated, CPEB3-induced translation of synaptic mRNA is inhibited and and memory formation is constrained (Drisaldi et al. 2015). The SUMOylation machinery is also conserved in Drosophila (Talamillo et al. 2008) and is enriched in the adult CNS where it is required for normal neuronal function (Long and Griffith 2000). Here, we have shown Ubc9 is critically required for LTM in Drosophila. Moreover, nearly all components of the SUMOylation machinery interact genetically with HDAC4, suggesting the importance of SUMO for HDAC4 function. Overexpression of HDAC4 combined with knockdown of Ubc9 resulted in a more severe memory phenotype, suggesting an interaction between them during LTM formation. We did not observe any global changes in SUMOylation when HDAC4 was overexpressed. This was not necessarily unexpected, as E3 ligases impart substrate specificity, rather than being essential for the process of SUMOylation (Wang and Dasso 2009; Gareau and Lima 2010), and as yet, very few putative HDAC4 substrates have been identified. Also, functionally important HDAC4-mediated changes in SUMOylation could be restricted to localized regions of brain and subsets of proteins that interact with HDAC4. We were unable to detect changes in SUMOylation of candidate proteins MEF2, CaMKII, or CREB. More than 100 proteins in Drosophila have been identified to bind SUMO (Lehembre et al. 2000; Sahota et al. 2009; Abed et al. 2011; Guruharsha et al. 2011; Handu et al. 2015) and further investigation of these and other SUMOylated proteins that are involved in synaptic plasticity in other organisms may shed light on the nature of this interaction. It also should be considered that the interaction between HDAC4 and Ubc9 could be independent of SUMOylation. Indeed, there are a few studies in which a SUMOylation-independent role for Ubc9 has been reported, which include modulation of invasion and metastasis in a breast cancer cell line (Zhu et al. 2010), regulation of insulin sensitivity of glucose transport (Liu et al. 2007), and transcriptional activation of PLAGL2 (Guo et al. 2008). The specific mechanisms through which Ubc9 acts were not determined except for the latter report, in which it displayed transcriptional coactivator activity.

In summary, our findings that HDAC4 interacts with several components of the SUMOylation machinery in Drosophila, and that Ubc9 is required for LTM formation in Drosophila, suggest that this would be an informative model to further investigate these interactions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Niki Murray and the Manawatu Microscopy and Imaging Center, (Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand), for scanning electron microscopy; David Wheeler for bioinformatics advice; Elizabeth Scholl for bioinformatic analyses; and Albert Courey and Bruce Paterson for kind gifts of the SUMO and MEF2 antibodies. We also thank New Zealand Genomics Limited for providing the bioIT platform. This work was supported by a Health Research Council of New Zealand Sir Charles Hercus Health Research fellowship and a Palmerston North Medical Research Foundation grant to H.L.F.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: M. F. Wolfner

Supplemental material is available online at www.genetics.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1534/genetics.115.183194/-/DC1.

Literature Cited

- Abed M., Barry K. C., Kenyagin D., Koltun B., Phippen T. M., et al. , 2011. Degringolade, a SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligase, inhibits Hairy/Groucho-mediated repression. EMBO J. 30: 1289–1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J., Bhandari R., Kumar J. P., 2005. A genetic screen identifies putative targets and binding partners of CREB-binding protein in the developing Drosophila eye. Genetics 171: 1655–1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andzelm M. M., Cherry T. J., Harmin D. A., Boeke A. C., Lee C., et al. , 2015. MEF2D drives photoreceptor development through a genome-wide competition for tissue-specific enhancers. Neuron 86: 247–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aso Y., Grubel K., Busch S., Friedrich A. B., Siwanowicz I., et al. , 2009. The mushroom body of adult Drosophila characterized by GAL4 drivers. J. Neurogenet. 23: 156–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backs J., Backs T., Bezprozvannaya S., McKinsey T. A., Olson E. N., 2008. Histone deacetylase 5 acquires calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II responsiveness by oligomerization with histone deacetylase 4. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28: 3437–3445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa A. C., Kim M. S., Ertunc M., Adachi M., Nelson E. D., et al. , 2008. MEF2C, a transcription factor that facilitates learning and memory by negative regulation of synapse numbers and function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105: 9391–9396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskar V., Valentine S. A., Courey A. J., 2000. A functional interaction between dorsal and components of the Smt3 conjugation machinery. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 4033–4040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonkowsky J. L., Yoshikawa S., O’Keefe D. D., Scully A. L., Thomas J. B., 1999. Axon routing across the midline controlled by the Drosophila Derailed receptor. Nature 402: 540–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briancon-Marjollet A., Ghogha A., Nawabi H., Triki I., Auziol C., et al. , 2008. Trio mediates netrin-1-induced Rac1 activation in axon outgrowth and guidance. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28: 2314–2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao W., Song H. J., Gangi T., Kelkar A., Antani I., et al. , 2008. Identification of novel genes that modify phenotypes induced by Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid overexpression in Drosophila. Genetics 178: 1457–1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Gomez S., Barrera-Ocampo A., Machado-Rodriguez G., Castro-Alvarez J. F., Glatzel M., et al. , 2013. Specific de-SUMOylation triggered by acquisition of spatial learning is related to epigenetic changes in the rat hippocampus. Neuroreport 24: 976–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain S. E., Gonzalez-Gonzalez I. M., Wilkinson K. A., Konopacki F. A., Kantamneni S., et al. , 2012. SUMOylation and phosphorylation of GluK2 regulate kainate receptor trafficking and synaptic plasticity. Nat. Neurosci. 15: 845–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao H. W., Hong C. J., Huang T. N., Lin Y. L., Hsueh Y. P., 2008. SUMOylation of the MAGUK protein CASK regulates dendritic spinogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 182: 141–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawla S., Vanhoutte P., Arnold F. J., Huang C. L., Bading H., 2003. Neuronal activity-dependent nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of HDAC4 and HDAC5. J. Neurochem. 85: 151–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B., Cepko C. L., 2009. HDAC4 regulates neuronal survival in normal and diseased retinas. Science 323: 256–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. C., Hsu W. L., Ma Y. L., Tai D. J., Lee E. H., 2014. CREB SUMOylation by the E3 ligase PIAS1 enhances spatial memory. J. Neurosci. 34: 9574–9589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J., Huang M., Zhu Y., Xin Y. J., Zhao Y. K., et al. , 2014. SUMOylation of MeCP2 is essential for transcriptional repression and hippocampal synapse development. J. Neurochem. 128: 798–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen T. J., Barrientos T., Hartman Z. C., Garvey S. M., Cox G. A., et al. , 2009. The deacetylase HDAC4 controls myocyte enhancing factor-2-dependent structural gene expression in response to neural activity. FASEB J. 23: 99–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole C. J., Mercaldo V., Restivo L., Yiu A. P., Sekeres M. J., et al. , 2012. MEF2 negatively regulates learning-induced structural plasticity and memory formation. Nat. Neurosci. 15: 1255–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darcy M. J., Calvin K., Cavnar K., Ouimet C. C., 2010. Regional and subcellular distribution of HDAC4 in mouse brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 518: 722–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deal R. B., Henikoff S., 2011. The INTACT method for cell type-specific gene expression and chromatin profiling in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat. Protoc. 6: 56–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drisaldi B., Colnaghi L., Fioriti L., Rao N., Myers C., et al. , 2015. SUMOylation is an inhibitory constraint that regulates the prion-like aggregation and activity of CPEB3. Cell Reports 11: 1694–1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubnau J., Chiang A. S., Grady L., Barditch J., Gossweiler S., et al. , 2003. The staufen/pumilio pathway is involved in Drosophila long-term memory. Curr. Biol. 13: 286–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ejima A., Smith B. P., Lucas C., Levine J. D., Griffith L. C., 2005. Sequential learning of pheromonal cues modulates memory consolidation in trainer-specific associative courtship conditioning. Curr. Biol. 15: 194–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ejima A., Smith B. P., Lucas C., van der Goes van Naters W., Miller C. J., et al. , 2007. Generalization of courtship learning in Drosophila is mediated by cis-vaccenyl acetate. Curr. Biol. 17: 599–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engert F., Bonhoeffer T., 1999. Dendritic spine changes associated with hippocampal long-term synaptic plasticity. Nature 399: 66–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischle W., Dequiedt F., Hendzel M. J., Guenther M. G., Lazar M. A., et al. , 2002. Enzymatic activity associated with class II HDACs is dependent on a multiprotein complex containing HDAC3 and SMRT/N-CoR. Mol. Cell 9: 45–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimons H. L., 2015. The Class IIa histone deacetylase HDAC4 and neuronal function: Nuclear nuisance and cytoplasmic stalwart? Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 123: 149–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimons H. L., Scott M. J., 2011. Genetic modulation of Rpd3 expression impairs long-term courtship memory in Drosophila. PLoS One 6: e29171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimons H. L., Schwartz S., Given F. M., Scott M. J., 2013. The histone deacetylase HDAC4 regulates long-term memory in Drosophila. PLoS One 8: e83903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flavell S. W., Cowan C. W., Kim T. K., Greer P. L., Lin Y., et al. , 2006. Activity-dependent regulation of MEF2 transcription factors suppresses excitatory synapse number. Science 311: 1008–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschini A., Szklarczyk D., Frankild S., Kuhn M., Simonovic M., et al. , 2013. STRING v9.1: protein-protein interaction networks, with increased coverage and integration. Nucleic Acids Res. 41: D808–D815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman M., 1996. Reiterative use of the EGF receptor triggers differentiation of all cell types in the Drosophila eye. Cell 87: 651–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gareau J. R., Lima C. D., 2010. The SUMO pathway: emerging mechanisms that shape specificity, conjugation and recognition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11: 861–871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goossens T., Kang Y. Y., Wuytens G., Zimmermann P., Callaerts-Vegh Z., et al. , 2011. The Drosophila L1CAM homolog Neuroglian signals through distinct pathways to control different aspects of mushroom body axon development. Development 138: 1595–1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregoire S., Yang X. J., 2005. Association with class IIa histone deacetylases upregulates the sumoylation of MEF2 transcription factors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25: 2273–2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grozinger C. M., Schreiber S. L., 2000. Regulation of histone deacetylase 4 and 5 and transcriptional activity by 14–3-3-dependent cellular localization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97: 7835–7840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y., Yang M. C., Weissler J. C., Yang Y. S., 2008. Modulation of PLAGL2 transactivation activity by Ubc9 co-activation not SUMOylation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 374: 570–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guruharsha K. G., Rual J. F., Zhai B., Mintseris J., Vaidya P., et al. , 2011. A protein complex network of Drosophila melanogaster. Cell 147: 690–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handu M., Kaduskar B., Ravindranathan R., Soory A., Giri R., et al. , 2015. SUMO-enriched proteome for Drosophila innate immune response. G3 (Bethesda) 5: 2137–2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris R., Sabatelli L. M., Seeger M. A., 1996. Guidance cues at the Drosophila CNS midline: identification and characterization of two Drosophila Netrin/UNC-6 homologs. Neuron 17: 217–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazelett D. J., Bourouis M., Walldorf U., Treisman J. E., 1998. decapentaplegic and wingless are regulated by eyes absent and eyegone and interact to direct the pattern of retinal differentiation in the eye disc. Development 125: 3741–3751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks I. A., D’Souza R. C., Yang B., Verlaan-de Vries M., Mann M., et al. , 2014. Uncovering global SUMOylation signaling networks in a site-specific manner. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 21: 927–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henley J. M., Craig T. J., Wilkinson K. A., 2014. Neuronal SUMOylation: mechanisms, physiology, and roles in neuronal dysfunction. Physiol. Rev. 94: 1249–1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry G. L., Davis F. P., Picard S., Eddy S. R., 2012. Cell type-specific genomics of Drosophila neurons. Nucleic Acids Res. 40: 9691–9704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtmaat A., Svoboda K., 2009. Experience-dependent structural synaptic plasticity in the mammalian brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10: 647–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang E. Y., Zhang J., Miska E. A., Guenther M. G., Kouzarides T., et al. , 2000. Nuclear receptor corepressors partner with class II histone deacetylases in a Sin3-independent repression pathway. Genes Dev. 14: 45–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal Z., Vandeweyer G., van der Voet M., Waryah A. M., Zahoor M. Y., et al. , 2013. Homozygous and heterozygous disruptions of ANK3: at the crossroads of neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders. Hum. Mol. Genet. 22: 1960–1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer S. C., Wang D., Iyer E. P., Trunnell S. A., Meduri R., et al. , 2012. The RhoGEF trio functions in sculpting class specific dendrite morphogenesis in Drosophila sensory neurons. PLoS One 7: e33634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanakousaki K., Gibson M. C., 2012. A differential requirement for SUMOylation in proliferating and non-proliferating cells during Drosophila development. Development 139: 2751–2762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel E. R., Dudai Y., Mayford M. R., 2014. The molecular and systems biology of memory. Cell 157: 163–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplow M. E., Mannava L. J., Pimentel A. C., Fermin H. A., Hyatt V. J., et al. , 2007. A genetic modifier screen identifies multiple genes that interact with Drosophila Rap/Fzr and suggests novel cellular roles. J. Neurogenet. 21: 105–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keleman K., Kruttner S., Alenius M., Dickson B. J., 2007. Function of the Drosophila CPEB protein Orb2 in long-term courtship memory. Nat. Neurosci. 10: 1587–1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M. S., Akhtar M. W., Adachi M., Mahgoub M., Bassel-Duby R., et al. , 2012. An essential role for histone deacetylase 4 in synaptic plasticity and memory formation. J. Neurosci. 32: 10879–10886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. I., Ryu T., Lee J., Heo Y. S., Ahnn J., et al. , 2010. A genetic screen for modifiers of Drosophila caspase Dcp-1 reveals caspase involvement in autophagy and novel caspase-related genes. BMC Cell Biol. 11: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles-Barley, S., M. Longair and J. D. Armstrong, 2010 BrainTrap: a database of 3D protein expression patterns in the Drosophila brain. Database (Oxford) 2010: baq005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kockel L., Vorbruggen G., Jackle H., Mlodzik M., Bohmann D., 1997. Requirement for Drosophila 14–3-3 zeta in Raf-dependent photoreceptor development. Genes Dev. 11: 1140–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Choi K. H., Renthal W., Tsankova N. M., Theobald D. E., et al. , 2005. Chromatin remodeling is a key mechanism underlying cocaine-induced plasticity in striatum. Neuron 48: 303–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Nahm M., Lee M., Kwon M., Kim E., et al. , 2007. The F-actin-microtubule crosslinker Shot is a platform for Krasavietz-mediated translational regulation of midline axon repulsion. Development 134: 1767–1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehembre F., Badenhorst P., Muller S., Travers A., Schweisguth F., et al. , 2000. Covalent modification of the transcriptional repressor tramtrack by the ubiquitin-related protein Smt3 in Drosophila flies. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20: 1072–1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiss F., Koper E., Hein I., Fouquet W., Lindner J., et al. , 2009. Characterization of dendritic spines in the Drosophila central nervous system. Dev. Neurobiol. 69: 221–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Chen J., Ricupero C. L., Hart R. P., Schwartz M. S., et al. , 2012. Nuclear accumulation of HDAC4 in ATM deficiency promotes neurodegeneration in ataxia telangiectasia. Nat. Med. 18: 783–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]