Abstract

Background

The association between resting heart rate and ischemic stroke remains unclear.

Methods

A total of 24,730 participants (mean age: 64 ± 9.3 years; 59% women; 41% blacks) from the REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study who were free of stroke at the time of enrollment (2003-2007) were included in this analysis. Resting heart rate was determined from baseline electrocardiogram data. Heart rate was examined as a continuous variable per 10 bpm increase and also as a categorical variable using tertiles (<61 bpm, 61 to 70 bpm, and >70 bpm). First-time ischemic stroke events were identified during follow-up and adjudicated by physician review.

Results

Over a median follow-up of 7.6 years, a total of 646 ischemic strokes occurred. In a Cox regression model adjusted for socio-demographics, cardiovascular risk factors, and potential confounders, each 10 bpm increase in heart rate was associated with a 10% increase in the risk of ischemic stroke (HR=1.10, 95%CI=1.02, 1.18). In the categorical model, an increased risk of ischemic stroke was observed for heart rates in the middle (HR=1.29, 95%CI=1.06, 1.57) and upper (HR=1.37, 95%CI=1.12, 1.67) tertiles compared with the lower tertile. The results were consistent when the analysis was stratified by age, sex, race, exercise habits, hypertension, and coronary heart disease.

Conclusion

In REGARDS, high resting heart rates were associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke compared with low heart rates. Further research is needed to examine whether interventions aimed to reduce heart rate decrease stroke risk.

Keywords: heart rate, stroke, epidemiology

Introduction

High resting heart rates are associated with an increased risk for coronary heart disease and cardiovascular-related mortality (1-6). High resting heart rates possibly are a manifestation of altered autonomic nervous tone associated with increased vascular resistance and high blood pressure that predisposes to the development of coronary heart disease and adverse cardiovascular outcomes.

The association between resting heart rate and stroke remains unclear as the reports that have examined this relationship are conflicting. Data from patients with stable coronary artery disease and hypertension have shown that high resting heart rates are associated with an increased risk of stroke (7, 8). Similarly, a study from the general Chinese population has suggested that high resting heart rates are associated with an increased stroke risk (9). In contrast, reports from the general French population and the Women's Health Initiative Study have shown that resting heart rate is not associated with stroke (10, 11). Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine the association between resting heart rate and first-time ischemic stroke events in the REasons for Geographic And Ethnic Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study.

Methods

Study Population and Design

Details of REGARDS have been published previously (12). Briefly, REGARDS was designed to identify causes of regional and racial disparities in stroke mortality. Between January 2003 and October 2007, the study over sampled blacks and residents of the stroke belt (North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, Arkansas, and Louisiana). This included participants from the stroke buckle (coastal plains of North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia) as this region experiences a stroke mortality rate considerably higher than the rest of the United States (13). A total of 30,239 participants were recruited from a commercially available list of residents using postal mailings and telephone data. Demographic information and medical histories were obtained using a computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI) system that was conducted by trained interviewers. Additionally, a brief in-home physical examination was performed approximately 3 to 4 weeks after the telephone interview. During the in-home visit, trained staff collected information regarding medications, blood and urine samples, and a resting electrocardiogram. Participants provided verbal consent by telephone interview followed by written consent during the in-home visit. The institutional review boards of participating institutions approved the study protocol.

For the purpose of this analysis, participants were excluded with data anomalies (n=56), baseline stroke (n=1,930), baseline atrial fibrillation (n=2,156), missing baseline characteristics (n=945), and missing follow-up data (n=422).

Heart Rate

Resting heart rate was determined from baseline electrocardiogram data that were obtained during the in-home examination. Heart rate was determined from the R to R interval. The electrocardiograms were read and coded at a central reading center (Epidemiological Cardiology Research Center, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, USA) by analysts who were blinded to other REGARDS data.

Ischemic Stroke

The adjudication process for stroke events in REGARDS has been previously reported (14). Briefly, during follow-up, reports of possible strokes, transient ischemic attacks, deaths, hospitalizations or emergency department visits for stroke symptoms, or unknown reasons generated a request for medical record review. For possible stroke events, records were centrally adjudicated by physicians. Strokes were defined using the World Health Organization (WHO) definition (15). Events that did not meet the WHO definition but with symptoms lasting more than 24 hours and with imaging consistent with acute ischemia or hemorrhage were classified as “clinical strokes.” Strokes subsequently were classified as ischemic or hemorrhagic. This analysis included both WHO and clinical ischemic stroke events. Hemorrhagic strokes were excluded.

Covariates

Age, sex, race, income, education, exercise habits, and smoking status were self-reported. Annual household income was dichotomized at $20,000. Education was categorized into “high school or less,” or “some college or more.” Exercise was dichotomized at ≥4 times per week. Smoking was defined as active (e.g., current) cigarette use. Fasting blood samples were obtained and assayed for serum glucose. Diabetes was defined as a fasting glucose level ≥126 mg/dL (or a non-fasting glucose ≥200 mg/dL among those failing to fast) or self-reported diabetes medication use. The current use of aspirin and antihypertensive medications was self-reported. The use of beta blockers, non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, digoxin, statins, warfarin, and other antiarrhythmic agents were ascertained during the in-home visit by pill bottle review. After the participant rested for 5 minutes in a seated position, blood pressure was measured using a sphygmomanometer. Hypertension was defined as blood pressure ≥140/90 or by the self-reported use of antihypertensive medications. Using baseline electrocardiogram data, left ventricular hypertrophy was defined by the Sokolow-Lyon Criteria (16). Atrial fibrillation was identified at baseline by the study-scheduled electrocardiogram and also from self-reported history of a physician diagnosis during the CATI survey. Coronary heart disease was ascertained by self-reported history of myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass grafting, coronary angioplasty or stenting, or if evidence of prior myocardial infarction was present on the baseline electrocardiogram. Prior stroke also was ascertained by self-reported history.

Statistics

The association between heart rate and ischemic stroke was examined as a continuous variable per 10 bpm increase and also as a categorical variable using tertiles with the lower tertile as the reference group. Categorical variables were reported as frequency and percentage while continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical significance for categorical variables was tested using the chi-square method and the Kruskal-Wallis procedure for continuous variables. Incidence rates per 1000 person-years were computed for ischemic stroke by heart rate tertiles. Kaplan-Meier estimates were used to compute the cumulative incidence of ischemic stroke events by heart rate, and the differences in estimates were compared using the log-rank procedure (17). Cox regression was used to compute hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the association between heart rate and ischemic stroke. Multivariable models were constructed as follows: Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, race, education, income, and region of residence; Model 2 adjusted for Model 1 covariates plus systolic blood pressure, smoking, diabetes, left ventricular hypertrophy, antihypertensive medications, antiarrhythmic agents (class I-IV), statins, aspirin, warfarin, and coronary heart disease. A sensitivity analysis was performed with the exclusion of participants taking heart rate modifying drugs (digoxin and class I-IV antiarrhythmic agents). An additional analysis was performed excluding participants who were taking beta blockers. We also examined if the association between heart rate and ischemic stroke varied by age (<65 years vs. ≥65 years), sex, race (black vs. white), exercise habits (≥4 days/week vs. <4 days/week), hypertension, or coronary heart disease using a stratification technique and comparing models with and without interaction terms. Statistical significance for all comparisons including interactions was defined as p <0.05. SAS® Version 9.3 (Cary, NC) was used for all analyses.

Results

A total of 24,730 study participants (mean age: 64 ± 9.3 years; 59% women; 41% blacks) were included in this analysis. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics across heart rate tertiles. Differences were observed for all characteristics except for calcium channel blockers, antiarrhythmic agents, and warfarin. A larger percentage of participants who were taking beta blockers were in the lower heart rate tertile.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics (N=24,730).

| Characteristic | Lower Tertile (<61 bpm) (n=7,951) |

Middle Tertile (61 to 70 bpm) (n=8,606) |

Upper Tertile (>70 bpm) (n=8,173) |

P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), years | 65 (9.3) | 64 (9.4) | 64 (9.3) | <0.0001 |

| Male Sex (%) | 4,265 (54) | 3,642 (42) | 3,136 (38) | <0.0001 |

| Black (%) | 2,791 (35) | 3,366 (39) | 3,919 (48) | <0.0001 |

| Region | ||||

| Stroke buckle (%) | 1,672 (21) | 1,890 (22) | 1,614 (20) | |

| Stroke belt (%) | 2,582 (32) | 2,943 (34) | 3,022 (37) | |

| Non-belt (%) | 3,697 (47) | 3,773 (44) | 3,537 (43) | <0.0001 |

| Education, high school or less (%) | 2,721 (34) | 3,092 (36) | 3,356 (41) | <0.0001 |

| Annual income, <$20,000 (%) | 1,051 (13) | 1,355 (16) | 1,721 (21) | <0.0001 |

| Exercise, ≥4 times per week (%) | 2,771 (35) | 2,582 (30) | 2,130 (26) | <0.0001 |

| Active smoker (%) | 770 (9.7) | 1,045 (12) | 1,688 (21) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes (%) | 1,126 (14) | 1,517 (18) | 2,254 (28) | <0.0001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | 127 (16) | 126 (16) | 129 (16) | <0.0001 |

| Aspirin (%) | 3,596 (45) | 3,507 (41) | 3,139 (38) | <0.0001 |

| Beta blockers (%) | 2,358 (30) | 1,528 (18) | 1,017 (12) | <0.0001 |

| Calcium channel blockers (%) | 408 (5.1) | 451 (5.2) | 482 (5.9) | 0.065 |

| Digoxin (%) | 97 (1.2) | 90 (1.1) | 137 (1.7) | 0.0011 |

| Antiarrhythmic agents (%) | 24 (0.30) | 34 (0.40) | 27 (0.33) | 0.57 |

| Warfarin (%) | 141 (1.8) | 133 (1.6) | 150 (1.8) | 0.31 |

| Statin (%) | 2,625 (33) | 2,441 (28) | 2,267 (28) | <0.0001 |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy (%) | 780 (9.8) | 767 (8.9) | 812 (9.9) | 0.048 |

| Coronary heart disease (%) | 1,392 (18) | 1,201 (14) | 1,157 (14) | <0.0001 |

Statistical significance for categorical variables tested using the chi-square method and for continuous variables the Kruskal-Wallis procedure was used.

Bpm=beats per minute; SD=standard deviation.

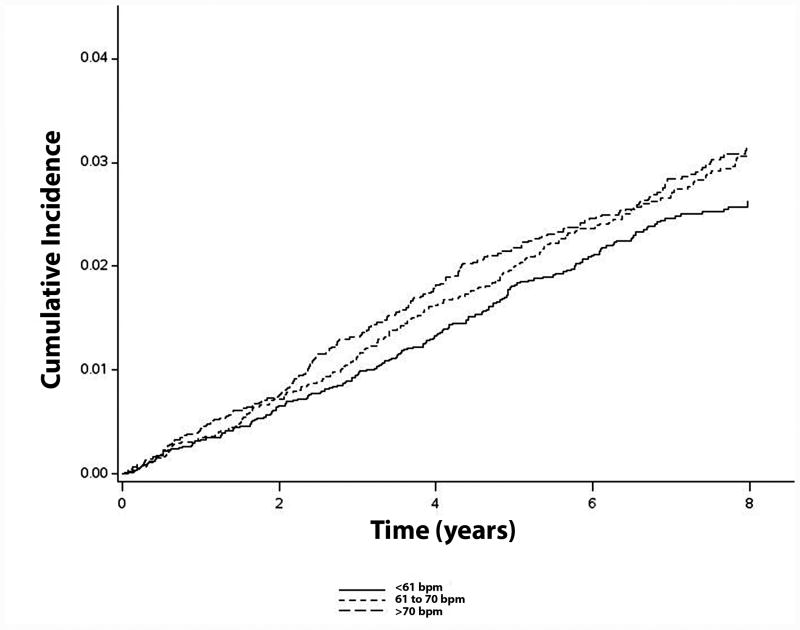

Over a median follow-up of 7.6 years, a total of 646 ischemic strokes occurred. Higher heart rates were associated with an increased incidence of ischemic stroke (incidence rates for lower, middle, and upper tertiles were 3.3, 3.7, and 4.1 per 1000 person-years, respectively) (Table 2). Figure 1 shows the unadjusted cumulative incidence curves of ischemic stroke across heart rate tertiles.

Table 2. Association between Resting Heart Rate and Ischemic Stroke (N=24,730).

| Events/No. At Risk | Incidence Rate per 1000 person-years | Model 1* HR (95%CI) |

P-value | Model 2† HR (95%CI) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Tertile (<61 bpm) | 192/7,951 | 3.3 (2.9, 3.8) | 1.0 | - | 1.0 | - |

| Middle Tertile (61 to 70 bpm) | 229/8,606 | 3.7 (3.3, 4.3) | 1.22 (1.01, 1.48) | 0.042 | 1.29 (1.06, 1.57) | 0.011 |

| Upper Tertile (>70 bpm) | 225/8,173 | 4.1 (3.6, 4.6) | 1.35 (1.11, 1.65) | 0.0025 | 1.37 (1.12, 1.67) | 0.0026 |

|

| ||||||

| Per 10 bpm increase | 646/24,730 | 3.7 (3.4, 4.0) | 1.10 (1.03, 1.18) | 0.0054 | 1.10 (1.02, 1.18) | 0.0086 |

Adjusted for age, sex, race, education, income, and region of residence.

Adjusted for Model 1 covariates with the addition of systolic blood pressure, smoking, diabetes, left ventricular hypertrophy, antihypertensive medications, antiarrhythmic agents, statins, aspirin, warfarin, and coronary heart disease.

Bpm=beats per minute; CI=confidence interval; HR=hazard ratio.

Figure 1. Cumulative Incidence of Ischemic Stroke by Heart Rate (N=24,730)*.

*Cumulative incidence curves are not statistically different (log-rank p=0.13). Bpm=beats per minute.

In a model adjusted for socio-demographics, cardiovascular risk factors, and potential confounders, each 10 bpm increase in heart rate was associated with a 10% increase in the risk of ischemic stroke (p=0.0086) (Table 2). In a similar model, a 29% (p=0.011) and 37% (p=0.0026) increased risk of ischemic stroke was observed for heart rates in the middle and upper tertiles compared with the lower tertile (Table 2). The association between resting heart rate and ischemic stroke did not vary by age, sex, race, exercise habits, hypertension, or coronary heart disease (Table 3).

Table 3. Subgroup Analyses by Age, Sex, Race, Exercise, Hypertension, and Coronary Heart Disease (N=24,730)*.

| Model 1† HR (95%CI) |

P-value | Model 2‡ HR (95%CI) |

P-value | Interactionδ P-value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||

| <65 years | 1.21 (1.07, 1.38) | 0.0033 | 1.16 (1.02, 1.32) | 0.029 | 0.12 |

| ≥65 years | 1.05 (0.97, 1.14) | 0.24 | 1.07 (0.98, 1.16) | 0.13 | |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 1.07 (0.97, 1.19) | 0.16 | 1.07 (0.97, 1.19) | 0.17 | 0.62 |

| Male | 1.13 (1.03, 1.24) | 0.011 | 1.12 (1.02, 1.24) | 0.019 | |

| Race | |||||

| Black | 1.15 (1.04, 1.27) | 0.0049 | 1.16 (1.05, 1.28) | 0.0046 | 0.12 |

| White | 1.06 (0.96, 1.17) | 0.24 | 1.05 (0.95, 1.16) | 0.34 | |

| Exercise | |||||

| ≥4 days/week | 1.14 (1.01, 1.30) | 0.042 | 1.14 (1.001, 1.30) | 0.048 | 0.54 |

| <4 days/week | 1.08 (1.00, 1.18) | 0.054 | 1.08 (0.99, 1.18) | 0.072 | |

| Hypertension | |||||

| No | 1.10 (0.96, 1.27) | 0.16 | 1.07 (0.93, 1.23) | 0.34 | 0.51 |

| Yes | 1.10 (1.01, 1.19) | 0.021 | 1.10 (1.02, 1.20) | 0.018 | |

| Coronary heart disease | |||||

| No | 1.13 (1.04, 1.22) | 0.0025 | 1.13 (1.04, 1.23) | 0.0036 | 0.57 |

| Yes | 1.03 (0.90, 1.18) | 0.63 | 1.02 (0.89, 1.17) | 0.81 |

HRs presented for heart rate per 10 bpm increase.

Adjusted for age, sex, race, education, income, and region of residence.

Adjusted for Model 1 covariates with the addition of systolic blood pressure, smoking, diabetes, left ventricular hypertrophy, antihypertensive medications, antiarrhythmic agents, statins, aspirin, warfarin, and coronary heart disease.

Interactions tested using Model 2.

CI=confidence interval; HR=hazard ratio.

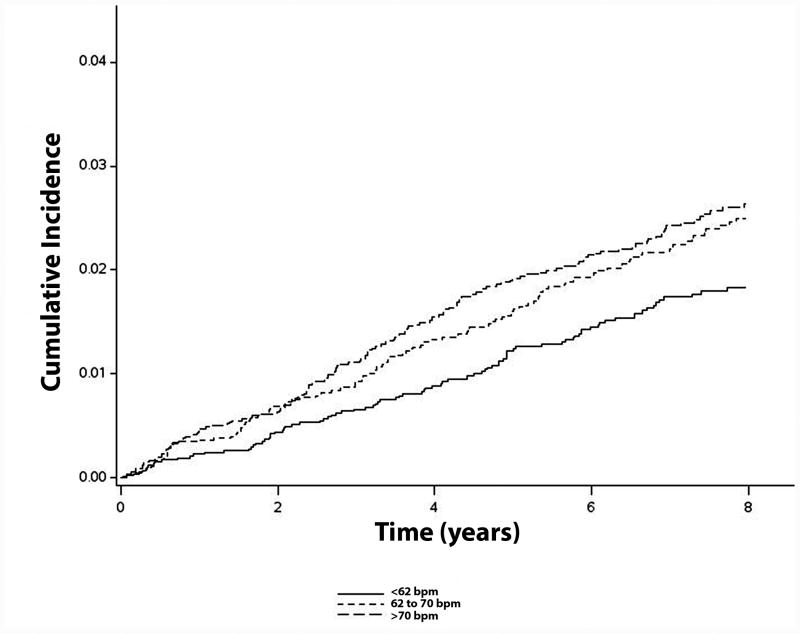

In a sensitivity analysis in which participants who reported taking heart rate modifying drugs (digoxin and antiarrhythmic agents) were excluded, a similar increased risk for ischemic stroke was observed for high compared with low resting heart rates (N=18,549; <62 bpm: HR=1.0, referent; 62 to 70 bpm: HR=1.32, 95%CI=1.02, 1.72; >70 bpm: HR=1.38, 95%CI=1.06, 1.78). Similar results were observed when the analysis excluded participants who reported using beta blockers (N=19,827; <62 bpm: HR=1.0, referent; 62 to 70 bpm: HR=1.44, 95%CI=1.12, 1.85; >70 bpm: HR=1.44, 95%CI=1.13, 1.84). A similar trend was observed when heart rate was examined as a continuous variable per 10 bpm increase (HR=1.08, 95%CI=0.99, 1.18). Figure 2 shows the unadjusted cumulative incidence curves of ischemic stroke across heart rate categories in study participants who were not receiving heart rate modifying drugs.

Figure 2. Cumulative Incidence of Ischemic Stroke by Heart Rate (N=18,549)*.

*Cumulative incidence curves are statistically different (log-rank p=0.016). Bpm=beats per minute.

Discussion

In this analysis from REGARDS, high resting heart rates were associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke compared with low resting heart rates. These results were consistent when the analysis was stratified by age, sex, race, exercise habits, hypertension, and coronary heart disease.

Several reports have examined the relationship between resting heart rate and future stroke events. A secondary analysis from the Ongoing Telmisartan Alone and in Combination with Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial (ONTARGET) and Telmisartan Randomized Assessment Study in ACE Intolerant Subjects with Cardiovascular Disease (TRANSCEND) trials among participants with stable cardiovascular disease (e.g., coronary, peripheral, or cerebrovascular disease, or diabetes with end organ damage) showed that high resting heart rates were associated with stroke (8). Data from the Valsartan Antihypertensive Long-term Use Evaluation (VALUE) trial also have shown that among patients with hypertension, high resting heart rates are associated with an increased stroke risk (7). However, both studies failed to report stroke subtype in their analyses (e.g., ischemic vs. hemorrhagic). In contrast, a study of 169,871 Chinese adults ≥40 years of age showed that high heart rates were associated with an increased risk of stroke in men but not women, and this association was limited to hemorrhagic events (9). A serious limitation of this analysis was that medications that influence heart rate were not included in the multivariable models (e.g., digoxin and antiarrhythmic agents). Similar null findings between resting heart rate and stroke (unspecified subtype) have been reported form the general French population and the Women's Health Initiative Study (10, 11). Both of the aforementioned studies did not account for medications that influence heart rate and the Women's Health Initiative Study only included women.

The results of the current study provide evidence that high resting heart rates are associated with an increased risk of stroke, and specifically identify ischemic stroke as the outcome of interest regarding the association between heart rate and cerebrovascular disease. Our results support the positive association between heart rate and stroke similar to that reported from specific subpopulations of patients with hypertension and cardiovascular disease (7, 8). Our findings also suggest that the association between heart rate and stroke possibly depends on medications that influence heart rate. Data from ONTARGET and TRANSCEND showed that the association between heart rate and stroke strengthens with adjustment for medications likely to influence heart rate (e.g., beta blockers and non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers) and a similar phenomenon was observed in our analysis.

Several mechanisms possibly explain the association between high heart rate and ischemic stroke. Animal models have shown that high heart rates are associated with higher levels of oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction that lead to a higher rate of atherosclerosis compared with mice treated with ivabradine for selective heart rate reduction (18, 19). Additionally, lower heart rates improve vascular compliance, an important determinant of blood pressure and cardiac autonomic tone (20). In aggregate, these data provide evidence that high heart rates predispose to several markers that are associated with the development of atherosclerotic disease, and also link high heart rates with ischemic stroke through shared risk factors (e.g., atherosclerosis, hypertension).

Due to the known risk of ischemic stroke with atrial fibrillation, it is possible that atrial fibrillation mediates the association between resting heart rate and ischemic stroke. Recent reports have implicated low resting heart rate with the development of atrial fibrillation. This has been shown in older persons (≥65 years), among persons with atherosclerotic disease or diabetes with evidence of end-organ damage, and among healthy middle-aged men (21-23). Possibly, individuals who develop atrial fibrillation and subsequent ischemic stroke have a stronger association between low resting heart rate and stroke. However, cardioembolism accounts for nearly 25% of acute ischemic strokes, and over 40% of these events are due to large vessel atherosclerosis and microvascular disease (e.g., lacunar stroke) (24). Therefore, the association between resting heart rate and ischemic stroke would be expected to show a positive association with high resting heart rates as the majority of known causes of ischemic stroke are related to poor cardiovascular disease risk factor profiles (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, smoking) (1-6). Potentially, low resting heart rates are associated with ischemic stroke subtypes more commonly found with cardioembolism (e.g., non-lacunar stroke) but the differentiation of ischemic stroke subtype was not available in this study. Additionally, incident atrial fibrillation cases were not recorded in REGARDS. Nonetheless, our findings suggest that the relationship between resting heart rate and ischemic stroke favors high heart rates. Further research is needed to determine if atrial fibrillation mediates the relationship between resting heart rate and ischemic stroke, with an emphasis on stroke subtypes commonly associated with this arrhythmia.

The prognostic implications of heart rate have been studied in several cardiovascular diseases. Improvements in outcomes of patients who have coronary heart disease and heart failure have been observed with pharmacological reductions in heart rate (25-27). Low heart rate also is associated with a lower mortality risk, better functional outcomes, and less cognitive decline after ischemic stroke (28). Possibly, those who have high heart rates are high risk for future cerebrovascular events and will benefit from pharmacologic interventions to decrease heart rate. However, further research is needed to determine which groups will benefit before changes in clinical practice are recommended. Additionally, although our data provide further evidence that the risk of ischemic stroke increases with higher heart rates, we were unable to determine if a target heart rate exists in which the stroke risk is lowest, and further research is needed to determine if such a group exists.

Our results should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. Several baseline characteristics (e.g., smoking, exercise) that likely influenced heart rate were self-reported and subjected our analysis to recall and misclassification biases. Beta blockers, non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, digoxin, and other antiarrhythmic agents were ascertained at baseline and it is possible that participants were prescribed these medications at later time points which would weaken the observed association between heart rate and stroke. Heart rate was measured during the baseline in-home examination and the results possibly vary with repeat measurements. We explored the association between heart rate and ischemic stroke due to the small number of hemorrhagic strokes in REGARDS. Additionally, we examined the association between heart rate and ischemic stroke after excluding participants who reported the use of medications that influenced heart rate. Although a non-significant result was observed in the continuous model, this likely is due to the reduced number of ischemic stroke cases (n=393). Several subgroup analyses were performed and possibly were underpowered to detect differences. Furthermore, residual confounding remains a possibility similar to other epidemiological studies.

In this analysis from REGARDS, high resting heart rates were associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke. Further studies are needed to confirm our findings and to examine whether heart rate modifying therapies are able to prevent future cerebrovascular events.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the REGARDS study for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating REGARDS investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.regardsstudy.org.

Funding: This research project is supported by a cooperative agreement U01 NS041588 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Service. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

References

- 1.Kannel WB, Kannel C, Paffenbarger RS, Jr, Cupples LA. Heart rate and cardiovascular mortality: the Framingham Study. Am Heart J. 1987;113(6):1489–94. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(87)90666-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenland P, Daviglus ML, Dyer AR, et al. Resting heart rate is a risk factor for cardiovascular and noncardiovascular mortality: the Chicago Heart Association Detection Project in Industry. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149(9):853–62. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gillum RF, Makuc DM, Feldman JJ. Pulse rate, coronary heart disease, and death: the NHANES I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study. Am Heart J. 1991;121(1 Pt 1):172–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(91)90970-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaper AG, Wannamethee G, Macfarlane PW, Walker M. Heart rate, ischaemic heart disease, and sudden cardiac death in middle-aged British men. Br Heart J. 1993;70(1):49–55. doi: 10.1136/hrt.70.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kovar D, Cannon CP, Bentley JH, Charlesworth A, Rogers WJ. Does initial and delayed heart rate predict mortality in patients with acute coronary syndromes? Clin Cardiol. 2004;27(2):80–6. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960270207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diaz A, Bourassa MG, Guertin MC, Tardif JC. Long-term prognostic value of resting heart rate in patients with suspected or proven coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2005;26(10):967–74. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Julius S, Palatini P, Kjeldsen SE, et al. Usefulness of heart rate to predict cardiac events in treated patients with high-risk systemic hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 2012;109(5):685–92. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lonn EM, Rambihar S, Gao P, et al. Heart rate is associated with increased risk of major cardiovascular events, cardiovascular and all-cause death in patients with stable chronic cardiovascular disease: an analysis of ONTARGET/TRANSCEND. Clin Res Cardiol. 2014;103(2):149–59. doi: 10.1007/s00392-013-0644-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mao Q, Huang JF, Lu X, et al. Heart rate influence on incidence of cardiovascular disease among adults in China. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(6):1638–46. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benetos A, Rudnichi A, Thomas F, Safar M, Guize L. Influence of heart rate on mortality in a French population: role of age, gender, and blood pressure. Hypertension. 1999;33(1):44–52. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsia J, Larson JC, Ockene JK, et al. Resting heart rate as a low tech predictor of coronary events in women: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2009;338:b219. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howard VJ, Cushman M, Pulley L, et al. The reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study: objectives and design. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25(3):135–43. doi: 10.1159/000086678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howard G, Anderson R, Johnson NJ, Sorlie P, Russell G, Howard VJ. Evaluation of social status as a contributing factor to the stroke belt region of the United States. Stroke. 1997;28(5):936–40. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.5.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howard VJ, Kleindorfer DO, Judd SE, et al. Disparities in stroke incidence contributing to disparities in stroke mortality. Ann Neurol. 2011;69(4):619–27. doi: 10.1002/ana.22385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stroke--1989. Recommendations on stroke prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. Report of the WHO Task Force on Stroke and other Cerebrovascular Disorders. Stroke. 1989;20(10):1407–31. doi: 10.1161/01.str.20.10.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sokolow M, Lyon TP. The ventricular complex in left ventricular hypertrophy as obtained by unipolar precordial and limb leads. Am Heart J. 1949;37(2):161–86. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(49)90562-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gray RJ, Tsiatis AA. A linear rank test for use when the main interest is in differences in cure rates. Biometrics. 1989;45(3):899–904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Custodis F, Baumhakel M, Schlimmer N, et al. Heart rate reduction by ivabradine reduces oxidative stress, improves endothelial function, and prevents atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circulation. 2008;117(18):2377–87. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.746537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kroller-Schon S, Schulz E, Wenzel P, et al. Differential effects of heart rate reduction with ivabradine in two models of endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress. Basic Res Cardiol. 2011;106(6):1147–58. doi: 10.1007/s00395-011-0227-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Custodis F, Fries P, Muller A, et al. Heart rate reduction by ivabradine improves aortic compliance in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J Vasc Res. 2012;49(5):432–40. doi: 10.1159/000339547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Neal WT, Almahmoud MF, Soliman EZ. Resting heart rate and incident atrial fibrillation in the elderly. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2015;38(5):591–7. doi: 10.1111/pace.12591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bohm M, Schumacher H, Linz D, et al. Low resting heart rates are associated with new-onset atrial fibrillation in patients with vascular disease: results of the ONTARGET/TRANSCEND studies. J Intern Med. 2015;278(3):303–312. doi: 10.1111/joim.12373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grundvold I, Skretteberg PT, Liestol K, et al. Low heart rates predict incident atrial fibrillation in healthy middle-aged men. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2013;6(4):726–31. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.113.000267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grau AJ, Weimar C, Buggle F, et al. Risk factors, outcome, and treatment in subtypes of ischemic stroke: the German stroke data bank. Stroke. 2001;32(11):2559–66. doi: 10.1161/hs1101.098524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gundersen T, Grottum P, Pedersen T, Kjekshus JK. Effect of timolol on mortality and reinfarction after acute myocardial infarction: prognostic importance of heart rate at rest. Am J Cardiol. 1986;58(1):20–4. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(86)90234-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lechat P, Escolano S, Golmard JL, et al. Prognostic value of bisoprolol-induced hemodynamic effects in heart failure during the Cardiac Insufficiency BIsoprolol Study (CIBIS) Circulation. 1997;96(7):2197–205. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.7.2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Der Vring JA, Daniels MC, Holwerda NJ, et al. Combination of calcium channel blockers and beta-adrenoceptor blockers for patients with exercise-induced angina pectoris: a double-blind parallel-group comparison of different classes of calcium channel blockers. Netherlands Working Group on Cardiovascular Research (WCN) Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;47(5):493–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00924.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bohm M, Cotton D, Foster L, et al. Impact of resting heart rate on mortality, disability and cognitive decline in patients after ischaemic stroke. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(22):2804–12. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]