Abstract

Background

Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae KP617 is a pathogenic strain that coproduces OXA-232 and NDM-1 carbapenemases. We sequenced the genome of KP617, which was isolated from the wound of a Korean burn patient, and performed a comparative genomic analysis with three additional strains: PittNDM01, NUHL24835 and ATCC BAA-2146.

Results

The complete genome of KP617 was obtained via multi-platform whole-genome sequencing. Phylogenetic analysis along with whole genome and multi-locus sequence typing of genes of the Klebsiella pneumoniae species showed that KP617 belongs to the WGLW2 group, which includes PittNDM01 and NUHL24835. Comparison of annotated genes showed that KP617 shares 98.3 % of its genes with PittNDM01. Nineteen antibiotic resistance genes were identified in the KP617 genome: blaOXA-1 and blaSHV-28 in the chromosome, blaNDM-1 in plasmid 1, and blaOXA-232 in plasmid 2 conferred resistance to beta-lactams; however, colistin- and tetracycline-resistance genes were not found. We identified 117 virulence factors in the KP617 genome, and discovered that the genes encoding these factors were also harbored by the reference strains; eight genes were lipopolysaccharide-related and four were capsular polysaccharide-related. A comparative analysis of phage-associated regions indicated that two phage regions are specific to the KP617 genome and that prophages did not act as a vehicle for transfer of antimicrobial resistance genes in this strain.

Conclusions

Whole-genome sequencing and bioinformatics analysis revealed similarity in the genome sequences and content, and differences in phage-related genes, plasmids and antimicrobial resistance genes between KP617 and the references. In order to elucidate the precise role of these factors in the pathogenicity of KP617, further studies are required.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13099-016-0117-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Klebsiella pneumoniae, OXA-232, NDM-1, Carbapenemases

Background

Klebsiella pneumoniae is a Gram-negative, non-motile, encapsulated, facultative anaerobic bacterium, which belongs to the family Enterobacteriaceae. K. pneumoniae is found in the normal flora of the mouth, skin, and intestines; however, this bacterium may act as an opportunistic pathogen, causing severe nosocomial infections such as septicemia, pneumonia, and urinary tract infections in hospitalized and immune-comprised patients with chronic ailments [1, 2].

Beta-lactam antibiotics, used as therapeutic agents against a broad range of bacteria, bind to the penicillin-binding protein and inhibit biosynthesis of the bacterial cell membrane. However, the extended spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) and carbapenemases confer resistance to penicillin, cephalosporins, or carbapenem [3, 4]. The β-lactamases are divided into four classes on the basis of the Ambler scheme: class A (Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase, KPC; imipenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase, IMI; Serratia marcescens enzyme, SME; Serratia fonticola carbapenemase, SFC), class B (Verona integron-encoded metallo-β-lactamase, VIM; imipenem-resistant Pseudomonas, IMP; New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase, NDM), class C (AmpC-type β-lactamase, ACT; cephamycin-hydrolyzing β-lactamase, CMY), and class D (oxacillinase, OXA) [5] are composed of transposon, cassettes, and integrons and transferred within and between species by HGT (horizontal gene transfer). Numerous carbapenemase-producing bacteria similarly harbor drug resistance genes that are transferred to other strains by horizontal gene transfer [6, 7]; infections caused by such multi-drug-resistant bacteria are difficult to treat [8]. The emergence of the novel carbapenemase NDM-1 (the New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase) is of great concern, as no therapeutic agents are available to treat infections caused by NDM-1-producing bacterial strains [9]. NDM-1-producing K. pneumoniae strains were first isolated from a Swedish patient who had travelled to India in 2009 [10]. Since then, NDM-1 has been reported to be produced by various species of Enterobacteriaceae, such as K. pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, Enterobacter spp. and Acinetobacter spp., in numerous countries [11].

The carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase OXA-232, which was first reported in E. coli and two K. pneumoniae strains [12], belongs to the OXA-48-like family. Carbapenemase-producing Gram-negative bacteria are often multi-drug resistant [13]. K. pneumoniae isolates that coproduce OXA-48-like β-lactamase and NDM-1 have been isolated in numerous countries [14–16]. Recently, K. pneumoniae isolates coproducing two carbapenemases, blaNDM-1 and blaOXA-232, have been identified in several countries; of these, two isolates originating in India were recovered in the USA and Korea, in January 2013, and sequenced [16, 17] but not studied yet the characteristics in the context of genomic contents by comparing these isolates. In the present study, we performed a comparative analysis of the genomes of these isolates.

Methods

Isolation and serotyping of strains

In January 2013, a 32-year-old man was hospitalized in the Intensive Care Unit of a general hospital in Seoul, Korea, two days after suffering burns during a visit to India. K. pneumoniae was isolated from his wound and another patient in the same room became infected with the same strain [18]. The K. pneumoniae isolate was identified as the KP617 strain belonging to the sequence type (ST)14, and found to coproduce NDM-1 and OXA-232, which conferred resistance to ertapenem, doripenem, imipenem, and meropenem (MICs: >32 mg/L). The K. pneumoniae strains PittNDM01 [17], NUHL24835 [19], and ATCC BAA-2146 [20] were used as reference strains for comparative genomic analysis.

Library preparation and whole-genome sequencing

Whole-genome sequencing of KP617 was performed using three platforms: Illumina-HiSeq 2500, PacBio RS II, and Sanger sequencing (GnC Bio: Daejeon, Republic of Korea) [16]. Sanger sequencing was used for the construction of a physical map of the genome.

Genome assembly and annotation

A hybrid assembly was performed using the Celera Assembler (version 8.2) [21] and a fosmid paired-end sequencing map was used to confirm the assembly. The final assembly was revised using proovread (version 2.12) [22]. An initial annotation of the KP617 genome was generated using the RAST (Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology, version 4.0) server pipeline [23]. The genomes of three K. pneumoniae strains, PittNDM01, NUHL24835, and ATCC BAA-2146, were annotated using the RAST server pipeline. In order to compare the total coding sequences (CDSs) of KP617 with those of the three K. pneumoniae strains, the sequence-based comparison functionality of the RAST server was utilized.

Phylogenetic analysis

Concatenated whole genomes of 44 K. pneumoniae strains, including KP617, and multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) of seven genes [24, 25] were used for the calculation of evolutionary distances. The seven genes used for MLST were as follows: gapA, infB, mdh, pgi, phoE, rpoB and tonB. Multiple sequence alignments were performed using Mugsy (version 1.2.3) [26]. The generalized time-reversible model [27] + CAT model [28] (FastTree Version 2.1.7) [29] was used to construct approximate maximum-likelihood phylogenetic trees. The resulting trees were visualized using FigTree (version 1.3.1) (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/).

Comparison of genomic structure

The chromosome and plasmids of KP617 and the reference strains were compared using Easyfig (version 2.2.2) [30]. Whole-genome nucleotide alignments were generated using BLASTN to identify syntenic genes. The syntenic genes and genomic structures were visualized using Easyfig. A stand-alone BLAST algorithm was used to analyze the structure of the genes of interest, i.e. the OXA-232- and NDM-1 carbapenemase-encoding genes.

Identification of the antimicrobial resistance genes

We identified the antibiotic resistance genes using complete sequences of chromosomes and plasmids of four K. pneumoniae isolates: KP617, PittNDM01, NUHL24853 and ATCC BAA-2146 using ResFinder 2.1 (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/ResFinder/) [31].

Analysis of virulence factors and phage-associated regions

The virulence factor-encoding genes were searched against the virulence factor database (VFDB) [32] using BLAST with an e-value threshold of 1e-5. Homologous virulence factor genes with a BLAST Score Ratio (BSR) of ≥0.4 were selected. The BSR score was calculated using our in-house scripts. Phage-associated regions in the genome sequences of the four K. pneumoniae strains were predicted using the PHAST server [33]. Three scenarios for the completeness of the predicted phage-associated regions were defined according to how many genes/proteins of a known phage the region contained: intact (≥90 %), questionable (90–60 %), and incomplete (≤60 %).

Quality assurance

Genomic DNA was purified from a pure culture of a single bacterial isolate of KP617. Potential contamination of the genomic library by other microorganisms was assessed using a BLAST search against the non-redundant database.

Results and discussion

General features

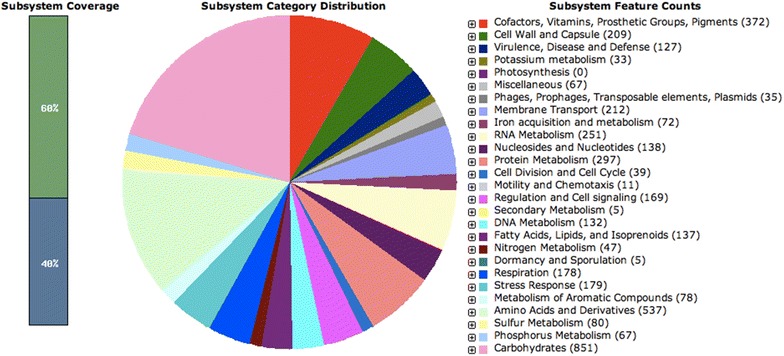

A total of 316,881,346 (32,005,015,946 bp) paired-end reads were generated using Illumina-HiSeq 2500. Using the PacBio RS II platform, 46,134 (421,257,386 bp) raw reads were produced. The complete genome of KP617 consists of a 5,416,282-bp circular chromosome and two plasmids of 273,628 bp and 6141 bp in size. The genomic features of KP617 and the reference strains are summarized in Table 1. Based on a RAST analysis, 5024 putative open reading frames (ORFs) and 110 RNA genes on the circular chromosome (Figs. 1, 2; Additional file 1: Table S1), 342 putative ORFs on plasmid 1, and 9 putative ORFs on plasmid 2 were identified.

Table 1.

Genomic features of Klebsiella pneumoniae KP617 and other strains

| Strain | KP617 | PittNDM01 | NUHL24835 | ATCC BAA-2146 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genome (Mb) | 5.69 | 5.81 | 5.53 | 5.78 |

| % GC (chromosome) | 57.4 | 57.5 | 57.4 | 57.3 |

| Total open reading frames | 5375 | 4940 | 5191 | 5883 |

| Plasmids | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

Fig. 1.

Subsystem category distribution of KP617 based on SEED databases

Fig. 2.

Circular map of the KP617 chromosome. Circular map of the KP617 genome, generated using cgview (version 2.2.2); from outside to inside, the tracks display the following information: CDSs of KP617 on the + strand (1); CDSs of KP617 on the − strand (2); tblastx result against PittNDM01 (3), tblastx result against NUHL24835 (4), tblastx result against ATCC BAA-2146 (5), GC content (6), GC skew with + value (green) and − value (purple) (7)

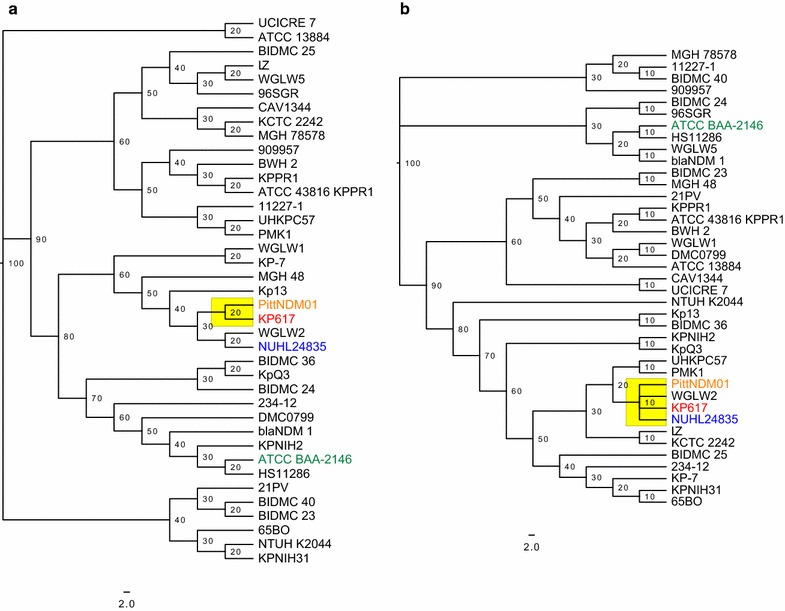

Comparison of KP617 and the reference strains based on sequence similarity (percent identity ≤80) showed that 32 genes are unique for KP617, and that most of the functional genes of this strain are also conserved in the reference strains. The genes unique to the KP617 strain, such as the SOS-response repressor and protease LexA (EC 3.4.21.88), integrase, and phage-related protein were identified as belonging to the genome of the prophage Salmonella phage SEN4 (GenBank accession: NC_029015). When the KP617 genome was compared with that of the PittNDM01 strain, which represents the closest neighbor of the former strain on the phylogenetic tree (Figs. 3a, b), 94 genes showed a percent similarity of below 80; most of these were phage protein-encoding genes. These results indicate that the presence of prophage DNA is an important feature of the KP617 genome.

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic tree of Klebsiella pneumoniae, a whole-genome phylogenetic tree; b MLSA phylogenetic tree; the scale represents the number of substitutions per site

Phylogenetic analysis

The whole-genome phylogenetic analysis indicated that KP617 is evolutionarily close to PittNDM01 and NUHL24835, and that the strains belong to the WGLW2 group. However, KP617 was found to be evolutionarily distant from ATCC BAA-2146 (Fig. 3). Concordantly, MLST-based phylogenetic analysis revealed that while KP617, PittNDM01, and NUHL24835 belong to the same group [sequence type (ST)14], ATCC BAA-2146 belongs to the HS11286 group, ST 11 [20]. The only difference between the whole-genome phylogenetic tree and the MLST-based phylogenetic tree was the divergence time within the same group; MLST-based phylogeny did not reveal the minor details of genomic evolution such as the divergence between KP617, PittNDM01 and NUHL24835 in the whole-genome phylogeny. The difference was attributed to horizontal gene transfer in regions not covered by the MLST genes.

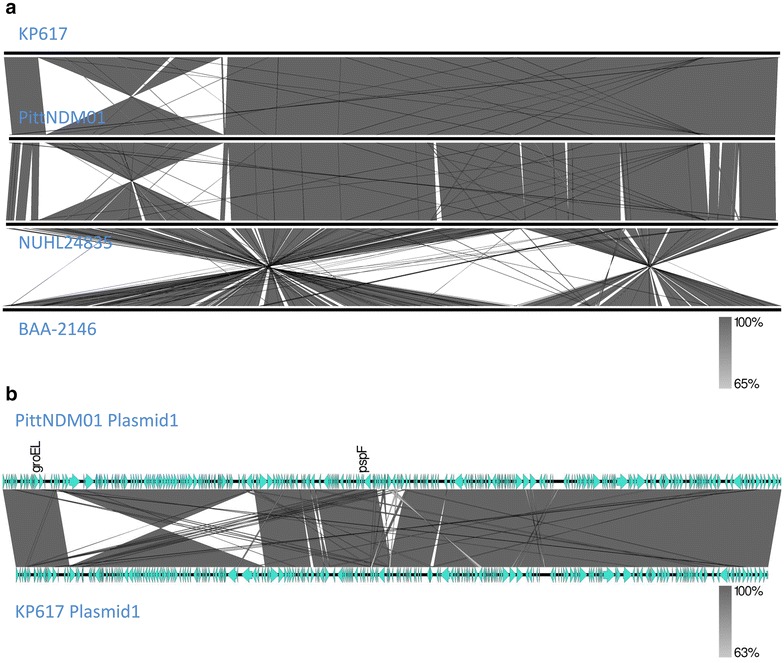

Comparison of genome structures

The comparison of genomic structures of the chromosome indicated the presence of highly conserved structures in the KP617, NUHL24835, and PittNDM01 strains (Fig. 4a). Interestingly, a 1-Mb region (233,805–1,517,597) of the KP617 chromosome was inverted relative to its arrangement in the chromosome of PittNDM01 (1,500,972–225,619). Despite this inversion, KP617 and PittNDM01 exhibited a lower substitution rate (score 20) than NUHL24835 (score 30) (Fig. 3). However, the chromosomal structure of the ATCC BAA-2146 strain, which consisted of two large inverted regions, was significantly different from that of the other strains. In addition, a 71 Kb inversion was found in the sequence of plasmid 1 of KP617 (18,633–90,686) relative to plasmid 1 of PittNDM01 (91,507–19,453); however, the two plasmids were highly homologous to each other (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

Comparative analysis of genome structures between KP617 and the reference strains PittNDM01, NUHL24835, and ATCC BAA-2146. a Comparison of chromosome structure between KP617 and the reference strains. An inversion spanning 233,805 bp to 1,517,597 bp (1 Mb in size) in the KP617 chromosome is shown. b Comparison between the structure of plasmid 1 of KP617 and plasmid 4 of PittNDM01. There was a 71 kb inversion, from 18,633 bp to 90,686 bp, in plasmid 1 of the KP617 strain

Antimicrobial resistance genes

Nineteen antibiotic resistance genes were identified in the genome of KP617, 39 in the genome of PittNDM01, 29 in that of ATCC BAA-2146, and nine in that of the NUHL24385 strain (Table 2). The β-lactam resistance genes in the KP617 genome were blaOXA-1 and blaSHV-28 in the chromosome, blaNDM-1 in plasmid 1, and blaOXA-232 in plasmid 2; however, genes conferring resistance to colistin and tetracycline were not found (Table 2). Plasmid 2 of KP617, which includes the OXA-232-encoding gene, consists of a 6141-bp sequence; the sequence of this plasmid was identical to that of plasmid 4 of PittNDM01 (100 % coverage and similarity) and the plasmid of E. coli (coverage: 100 %, similarity: 99.9 %). Plasmid 2 of KP617, plasmid 4 of PittNDM01 and E. coli Mob gene cluster (GenBank accession: JX423831) [12] carried the OXA-232-encoding gene, and pKF-3 of K. pneumoniae carried the OXA-181-encoding gene. However, pKF-3 was identical to plasmid 2 of KP617, except in that the insertion sequence ISEcp1 was inserted upstream of OXA-181 and included in the transposon Tn2013 [12, 34].

Table 2.

Antimicrobila resistance genes of KP617 and the reference strains

| Antibiotics | Resistance gene | % identity | Query/HSP length | Predicted phenotype | Accession number | Positiona | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KP617 | PittNDM01 | BAA-2146 | NHUL24385 | ||||||

| Aminoglycosides | aacA4 | 100 | 555/555 | Aminoglycoside resistance | KM278199 | P3_115183..115737 | |||

| aac(3)-IIa | 99.77 | 861/861 | X51534 | P2_41114..41974 | |||||

| aac(3)-IId | 99.88 | 861/861 | EU022314 | P3_64003..64863 | |||||

| aac(6′)-Ib | 100 | 606/606 | M21682 | P3_2456..3061 | P2_82742..83347 | ||||

| aadA1 | 100 | 789/789 | JQ480156 | P3_3131..3919 | |||||

| 99.75 | 792/798 | JQ414041 | P3_44412..45203 | ||||||

| aadA2 | 100 | 792/792 | JQ364967 | P1_261911..262702 | P1_271654..272445 | P1_53050..53841 | |||

| 100 | 780/780 | X68227 | C_2297697..2298476 | ||||||

| aph(3′)-VIa | 98.46 | 780/780 | X07753 | P1_4558..5337 | P1_4558..5337 | ||||

| armA | 100 | 774/774 | AY220558 | P1_267391..268164 | P1_277134..277907 | ||||

| rmtC | 100 | AB194779 | P3_120100..120945 | ||||||

| strA | 99.88 | 804/804 | AF321551 | P3_29207..30010 | |||||

| 100 | P2_53242..54045 | ||||||||

| strB | 99.88 | 837/837 | M96392 | P3_30010..30846 | |||||

| 100 | P2_52406..53242 | ||||||||

| aac(6′)Ib-cr | 100 | 600/600 | Fluoroquinolone and aminoglycoside resistance | DQ303918 | C_612688..613287 | C_1122863..1123462 | |||

| P1_136163..136762 | P2_38111..38710 | ||||||||

| Beta-lactams | blaOXA-1 | 100 | 831/831 | Beta-lactam resistance | J02967 | C_613418..614248 | C_1121902..1122732 | ||

| P1_136893..137723 | P2_38841..39671 | ||||||||

| blaOXA-9 | 100 | 840/840 | JF703130 | P3_3964..4803 | |||||

| blaOXA-232 | 100 | 798/798 | JX423831 | P2_3878..4675 | P4_3878..4675 | ||||

| blaNDM-1 | 100 | 813/813 | FN396876 | P1_7770..8582 | P1_7770..8582 | P3_122191..123003 | |||

| blaNDM-5 | 100 | 813/813 | JN104597 | P2_10716..11528 | |||||

| blaCTX-M-15 | 100 | 876/876 | DQ302097 | C_5407907..5408782 | |||||

| P3_68389..69264 | P2_47128..48003 | P1_47694..48569 | |||||||

| blaTEM-1A | 100 | 861/861 | HM749966 | P3_5503..6363 | |||||

| blaTEM-1B | 100 | 861/861 | JF910132 | P2_50825..51685 | |||||

| 595/861 | P1_49351..49945 | ||||||||

| blaSHV-11 | 100 | 861/861 | GQ407109 | P3_57446..58306 | C_2612965..2613825 | ||||

| 99.88 | P2_36311..37171 | ||||||||

| blaSHV-28 | 100 | 861/861 | HM751101 | C_1087615..1088475 | |||||

| 99.88 | C_1078475..1079335 | C_656815..657675 | |||||||

| blaCMY-6 | 100 | 1146/1146 | AJ011293 | P3_72203..73348 | |||||

| Fluoroquinolones | aac(6′)Ib-cr | 100 | 600/600 | Fluoroquinolone and aminoglycoside resistance | DQ303918 | C_612688..613287 | C_1122863..1123462 | ||

| P1_136163..136762 | P2_38111..38710 | ||||||||

| 99.42 | 519/519 | EF636461 | P3_2543..3061 | P2_82742..83260 | |||||

| 99.61 | P3_115219..115737 | ||||||||

| QnrB1 | 99.85 | 682/681 | Quinolone resistance | EF682133 | P1_130519..131200 | P1_130247..130928 | |||

| QnrB58 | 98.68 | 681/681 | JX259319 | P2_26062..26742 | |||||

| oqxA | 100 | 1176/1176 | EU370913 | C_4169699..4170874 | |||||

| 99.23 | C_4847144..4848319 | C_4793024..4794199 | C_4849531..4850706 | ||||||

| oqxB | 98.83 | 3153/3153 | EU370913 | C_4843968..4847120 | C_4789848..4793000 | C_4170898..4174050 | |||

| 98.79 | C_4846355..4849507 | ||||||||

| Fosfomycin | fosA | 97.38 | 420/420 | Fosfomycin resistance | NZ_AFBO01000747 | C_2957629..2958048 | C_2903507..2903926 | C_2946180..2946599 | |

| 97.14 | C_667959..668378 | ||||||||

| MLS—macrolide, lincosamide and streptogramin B | ere(A) | 95.11 | 1227/1227 | Macrolide resistance | AF099140 | P3_45289..46515 | |||

| mph(A) | 100 | 906/906 | D16251 | P1_16503..17408 | |||||

| mph(E) | 99.89 | 885/885 | EU294228 | P1_271994..272878 | P1_281737..282621 | ||||

| msr(E) | 100 | 1476/1476 | Macrolide, Lincosamide and Streptogramin B resistance | EU294228 | P1_270463..271938 | P1_280206..281681 | |||

| Phenicol | catB3 | 100 | 442/633 | Phenicol resistance | AJ009818 | P1_137861..138302 | P2_39809..40250 | ||

| C_614386..614827 | C_1121323..1121764 | ||||||||

| cmlA1 | 99.13 | AB212941 | P3_42931..44190 | ||||||

| Rifampicin | ARR-2 | 100 | 453/453 | Rifampicin resistance | HQ141279 | P3_46791..47243 | |||

| ARR-3 | CP002151 | C_2298894..2299820 | |||||||

| Sulphonamides | sul1 | 100 | 927/927 | Sulphonamide resistance | CP002151 | P1_263120..264046 | P1_272863..273789 | P3_116160..117086 | |

| sul1 | 100 | 837/837 | JN581942 | P3_41559..42395 | |||||

| sul2 | 100 | 816/816 | GQ421466 | P3_28331..29146 | |||||

| Tetracyclines | tet(A) | 100 | 1200/1200 | Tetracycline resistance | AJ517790 | P1_19168..20367 | |||

| Trimethoprim | dfrA1 | 100 | 474/474 | Trimethoprim resistance | X00926 | C_3627607..3628080 | C_3573485..3573958 | ||

| dfrA12 | 100 | 498/498 | AB571791 | P1_261006..261503 | P1_270749..271246 | P1_52145..52642 | |||

| dfrA14 | 99.59 | 483/483 | DQ388123 | P1_144525..145007 | P2_8272..8754 | ||||

KP617: C, CP012753.1; P1, CP012754.1; P2, CP012755.1

PittNDM01: C, CP006798.1; P1, CP006799.1; P2, CP006800.1; P3, CP006801.1; P4, CP006802.1

ATCC BAA-2146: C, CP006659.2; P1 (PCuAs), CP006663.1; P2 (PHg), CP006662.2; P3, CP006660.1; P4, CP006661.1

NUHL24385: C, CP014004.1; P1, CP014005.1; P2, CP014006.1

a C chromosome, P plasmid

The structure of plasmid 1 (273,628 bp in size) of the KP617 strain was similar to that of plasmid 1 (283,371 bp in size) of PittNDM01. A region of about 40 kb in size within plasmid 1 of the KP617 strain, which included the NDM-1-encoding gene, was composed of various resistance genes such as aadA2, armA, aac(3″)-VI, dfrA12, msrE, mphE, sul1 and qnrB1, and identical (coverage: 100 %, homology: 100 %) to a 40-kb sequence of plasmid 1 of PittNDM01 (Fig. 4b). Adjacent to the NDM-1-encoding gene, a region of about 70 kb in size was inverted in plasmid 1 of KP617 relative to plasmid 1 of PittNDM01. In addition, the OXA-1-encoding gene was identified in PittNDM01 but not in KP617. Transposases were found in a part of the NDM-1-encoding gene cluster (about 10 kb) in plasmid 1 of KP617. Gram-negative bacteria are known to possess a diverse range of transposases; moreover, the sequence of the NDM-1-encoding gene cluster includes a transposon [35, 36]. The partial, or complete, transfer of NDM-1-harboring plasmids between K. pneumoniae and E. coli, via conjugation, has been shown to result in the emergence of strains resistant to several antimicrobial agents [11, 32, 36, 37].

Following the initial identification of NDM-1 in a K. pneumoniae isolate from a patient who had travelled to India in 2008, most NDM-1-producing K. pneumoniae isolates have been recovered from patients associated with India; however, in some cases, these strains have been isolated from patients with no history of travelling abroad, or any association with India [38]. These observations suggest that the transfer of the NDM-1- and OXA-232-harboring plasmids between Gram-negative bacteria has resulted in the spread of carbapenem resistance and emergence of strong carbapenem-resistant strains outside the Indian subcontinent.

Virulence factors

Klebsiella pneumoniae, a significant pathogen of human hosts, causes urinary tract infections, pneumonia, septicemia, and soft tissue infections [1]. The clinical features of K. pneumoniae infections depend on the virulence factors expressed by the infecting strain [39]. Therefore, we investigated the virulence factors of the present strain and compared these with those of KP617 and the reference strains. A BLAST search was performed against VFDB to identify 117 virulence factors harbored by the KP617 strain (Table 3). All 117 virulence genes of KP617 were also harbored by the reference strains; KP617 did not possess any unique virulence factors. The PittNDM01 strain was also found to possess no unique virulence factors; however, NUHL24835 and ATCC BAA-2146 possessed 3 and 7 unique virulence factors, respectively. The 117 virulence genes of KP617 were classified into 31 the following categories: Iron uptake (30 genes), Immune evasion (12 genes), Endotoxin (11 genes), Adherence (10 genes), Fimbrial adherence determinants (8 genes), Toxin (7 genes), Antiphagocytosis (6 genes), Regulation (5 genes), Acid resistance (3 genes), Anaerobic respiration (2 genes), Cell surface components (2 genes) and Secretion system (2 genes). Among the 117 virulence genes identified, 8 genes were lipopolysaccharide [40]-related genes and 4 genes were capsular polysaccharide [41]-related.

Table 3.

Virulence genes of KP617 and the reference strains

| Strains | Category | Subcategory | Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| KP617, PittNDM01, NUHL24385 and ATCC BAA-2146 | Acid resistance | Urease | ureA, ureB, ureF, ureG, ureH |

| Adherence | Cell wall associated fibronectin binding protein | ebh | |

| Adherence | CFA/I fimbriae | ibeB | |

| Adherence | Flagella | fleN, fleR, fleS | |

| Adherence | Hsp60 | htpB | |

| Adherence | Intercellular adhesin | icaA, icaR | |

| Adherence | Listeria adhesion protein | lap | |

| Adherence | OapA | oapA | |

| Adherence | Omp89 | omp89 | |

| Adherence | P fimbriae | papX | |

| Adherence | PEB1/CBF1 | pebA | |

| Adherence | Phosphoethanolamine modification | lptA | |

| Adherence | Type I fimbriae | fimB, fimE, fimG | |

| Adherence | Type IV pili | comE/pilQ | |

| Adherence | Type IV pili biosynthesis | pilM, pilW | |

| Adherence | Type IV pili twitching motility related proteins | chpD, chpE | |

| Adhesin | Laminin-binding protein | lmb | |

| Adhesin | Streptococcal lipoprotein rotamase A | slrA | |

| Adhesin | Streptococcal plasmin receptor/GAPDH | plr/gapA | |

| Adhesin | Type IV pili | pilD, pilN, pilR, pilR, pilS, pilT | |

| Amino acid and purine metabolism | Glutamine synthesis | glnA1 | |

| Amino acid and purine metabolism | Leucine synthesis | leuD | |

| Amino acid and purine metabolism | Lysine synthesis | lysA | |

| Amino acid and purine metabolism | Proline synthesis | proC | |

| Amino acid and purine metabolism | Purine synthesis | purC | |

| Amino acid and purine metabolism | Tryptophan synthesis | trpD | |

| Anaerobic respiration | Nitrate reductase | narG, narH, narI, narJ | |

| Anaerobic respiration | Nitrate/nitrite transporter | narK2 | |

| Anti-apoptosis factor | NuoG | nuoG | |

| Antimicrobial activity | Phenazines biosynthesis | phzE1, phzF1, phzG1phzS | |

| Antiphagocytosis | Alginate regulation | algQ, algR, algU, algW, algZ, mucB, mucC, mucD, mucP | |

| Antiphagocytosis | Capsular polysaccharide | cpsB, wbfT, wbfV/wcvB, wbjD/wecB, wza, wzc | |

| Antiphagocytosis | Capsule | cpsF | |

| Antiphagocytosis | Capsule I | gmhA, wcbN, wcbP, wcbR, wcbT, wzt2 | |

| Cell surface components | GPL locus | fadE5, fmt, rmlB | |

| Cell surface components | MymA operon | adhD, fadD13, sadH, tgs4 | |

| Cell surface components | PDIM (phthiocerol dimycocerosate) and PGL (phenolic glycolipid) biosynthesis and transport | ddrA, mas, ppsC, ppsE | |

| Cell surface components | Potassium/proton antiporter | kefB | |

| Cell surface components | Proximal cyclopropane synthase of alpha mycolates | pcaA | |

| Cell surface components | Trehalose-recycling ABC transporter | lpqY, sugA, sugB, sugC | |

| Chemotaxis and motility | Flagella | flrA, flrB | |

| Efflux pump | FarAB | farA, farB | |

| Efflux pump | MtrCDE | mtrC, mtrD | |

| Endotoxin | LOS | gmhA/lpcA, kdtA, kpsF, lgtF, licA, lpxH, msbA, opsX/rfaC, orfM, rfaD, rfaE, rfaF, wecA, yhbX | |

| Endotoxin | LPS | bplA, bplC, bplF, wbmE, wbmI | |

| Endotoxin | LPS-modifying enzyme | pagP | |

| Exoenzyme | Cysteine protease | sspB | |

| Exoenzyme | Streptococcal enolase | eno | |

| Fimbrial adherence determinants | Agf/Csg | csgD | |

| Fimbrial adherence determinants | Fim | fimA, fimC, fimD, fimF, fimH, fimI | |

| Fimbrial adherence determinants | Lpf | lpfB, lpfC | |

| Fimbrial adherence determinants | Stg | stgA | |

| Fimbrial adherence determinants | Sth | sthA, sthB, sthC, sthD, sthE | |

| Fimbrial adherence determinants | Sti | stiB | |

| Glycosylation system | N-linked protein glycosylation | pglJ | |

| Host immune evasion | Exopolysaccharide | galE, galU, manA, mrsA/glmM, pgi | |

| Host immune evasion | LPS glucosylation | gtrB | |

| Host immune evasion | Polyglutamic acid capsule | capD | |

| Immune evasion | LPS | acpXL, htrB, kdsA, lpxA, lpxB, lpxC, lpxD, lpxK, pgm, wbkC | |

| Intracellular survival | LigA | ligA | |

| Intracellular survival | Lipoate protein ligase A1 | lplA1 | |

| Intracellular survival | Mip | mip | |

| Intracellular survival | Oligopeptide-binding protein | oppA | |

| Intracellular survival | Post-translocation chaperone | prsA2 | |

| Intracellular survival | Sugar-uptake system | hpt | |

| Invasion | Ail | ail | |

| Invasion | Cell wall hydrolase | iap/cwhA | |

| Iron acquisition | Cytochrome c muturation (ccm) locus | ccmA, ccmB, ccmC, ccmE, ccmF | |

| Iron acquisition | Ferrous iron transport | feoA, feoB | |

| Iron acquisition | Iron acquisition/assimilation locus | iraB | |

| Iron and heme acquisition | Haemophilus iron transport locus | hitA, hitB, hitC | |

| Iron and heme acquisition | Heme biosynthesis | hemA, hemB, hemC, hemD, hemE, hemG, hemH, hemL, hemM, hemN, hemX, hemY | |

| Iron uptake | ABC transporter | fagD | |

| Iron uptake | ABC-type heme transporter | hmuT, hmuU, hmuV | |

| Iron uptake | Achromobactin biosynthesis and transport | acsB, cbrB, cbrD | |

| Iron uptake | Aerobactin transport | iutA | |

| Iron uptake | ciu iron uptake and siderophore biosynthesis system | ciuD | |

| Iron uptake | Enterobactin receptors | irgA | |

| Iron uptake | Enterobactin synthesis | entE, entF | |

| Iron uptake | Enterobactin transport | fepA, fepB, fepC, fepD, fepG | |

| Iron uptake | Heme transport | shuV | |

| Iron uptake | Hemin uptake | chuS, chuT, chuY | |

| Iron uptake | Iron-regulated element | ireA | |

| Iron uptake | Iron/managanease transport | sitA, sitB, sitC, sitD | |

| Iron uptake | Periplasmic binding protein-dependent ABC transport systems | viuC | |

| Iron uptake | Pyochelin | pchA, pchB, pchR | |

| Iron uptake | Pyoverdine | pvdE, pvdH, pvdJ, pvdM, pvdN, pvdO | |

| Iron uptake | Salmochelin synthesis and transport | iroE, iroN | |

| Iron uptake | Vibriobactin biosynthesis | vibB | |

| Iron uptake | Vibriobactin utilization | viuB | |

| Iron uptake | Yersiniabactin siderophore | ybtA, ybtP | |

| Iron uptake systems | Ton system | exbB, exbD | |

| Lipid and fatty acid metabolism | FAS-II | kasB | |

| Lipid and fatty acid metabolism | Isocitrate lyase | icl | |

| Lipid and fatty acid metabolism | Pantothenate synthesis | panC, panD | |

| Lipid and fatty acid metabolism | Phospholipases C | plcD | |

| Macrophage inducible genes | Mig-5 | mig-5 | |

| Magnesium uptake | Mg2+ transport | mgtB | |

| Mammalian cell entry (mce) operons | Mce3 | mce3B | |

| Metal exporters | Copper exporter | ctpV | |

| Metal uptake | ABC transporter | irtB | |

| Metal uptake | Exochelin (smegmatis) | fxbA | |

| Metal uptake | Heme uptake | mmpL11 | |

| Metal uptake | Magnesium transport | mgtC | |

| Metal uptake | Mycobactin | fadE14, mbtH, mbtI | |

| Motility and export apparatus | Flagella | flhF, flhG, fliY | |

| Nonfimbrial adherence determinants | SinH | sinH | |

| Other adhesion-related proteins | EF-Tu | tuf | |

| Other adhesion-related proteins | PDH-B | pdhB | |

| Others | MsbB2 | msbB2 | |

| Others | Nuclease | nuc | |

| Others | VirK | virK | |

| Phagosome arresting | Nucleoside diphosphate kinase | ndk | |

| Protease | Trigger factor | tig/ropA | |

| Proteases | Proteasome-associated proteins | mpa | |

| Quorum sensing | Autoinducer-2 | luxS | |

| Quorum sensing systems | Acylhomoserine lactone synthase | hdtS | |

| Quorum sensing systems | N-(butanoyl)-l-homoserine lactone QS system | rhlR | |

| Regulation | Alternative sigma factor RpoS | rpoS | |

| Regulation | AtxA | atxA | |

| Regulation | BvrRS | bvrR | |

| Regulation | Carbon storage regulator A | csrA | |

| Regulation | DevR/S | devR/dosR | |

| Regulation | GacS/GacA two-component system | gacA, gacS | |

| Regulation | LetA/LetS two component | letA | |

| Regulation | LisR/LisK | lisK | |

| Regulation | MprA/B | mprA, mprB | |

| Regulation | PhoP/R | phoR | |

| Regulation | RegX3 | regX3 | |

| Regulation | RelA | relA | |

| Regulation | SenX3 | senX3 | |

| Regulation | Sigma A | sigA/rpoV | |

| Regulation | Two-component system | bvgA, bvgS | |

| Secreted proteins | Antigen 85 complex | fbpB, fbpC | |

| Secretion system | Accessory secretion factor | secA2 | |

| Secretion system | Bsa T3SS | bprC | |

| Secretion system | Flagella (cluster I) | fliZ | |

| Secretion system | Mxi-Spa TTSS effectors controlled by MxiE | ipaH, ipaH2.5 | |

| Secretion system | P. aeruginosa TTSS | exsA | |

| Secretion system | P. syringae TTSS | hrcN | |

| Secretion system | P. syringae TTSS effectors | hopAJ2, hopAN1, hopI1 | |

| Secretion system | TTSS secreted proteins | bopD | |

| Secretion system | Type III secretion system | bscS | |

| Secretion system | Type VII secretion system | essC | |

| Secretion system | VirB/VirD4 type IV secretion system & translocated effector Beps | bepA | |

| Serum resistance | BrkAB system | brkB | |

| Stress adaptation | AhpC | ahpC | |

| Stress adaptation | Catalase-peroxidase | katG | |

| Stress adaptation | Pore-forming protein | ompA | |

| Stress protein | Catalase | katA | |

| Stress protein | Manganese transport system | mntA, mntB, mntC | |

| Stress protein | Recombinational repair protein | recN | |

| Stress protein | SodCI | sodCI | |

| Surface protein anchoring | Lipoprotein diacylglyceryl transferase | lgt | |

| Surface protein anchoring | Lipoprotein-specific signal peptidase II | lspA | |

| Toxin | Beta-hemolysin/cytolysin | cylG | |

| Toxin | Enterotoxin | entA, entB, entC, entD | |

| Toxin | Hydrogen cyanide production | hcnC | |

| Toxin | Phytotoxin phaseolotoxin | argD, argK, cysC1 | |

| Toxin | Streptolysin S | sagA | |

| Toxins | Alpha-hemolysin | hlyA | |

| Toxins | Enterotoxin SenB/TieB | senB | |

| Two-component system | PhoPQ | phoP, phoQ | |

| Type I secretion system | ABC transporter for dispersin | aatC | |

| KP617, PittNDM01 and NUHL24385 | Antiphagocytosis | Capsular polysaccharide | cpsA |

| Cell surface components | GPL locus | pks | |

| Cell surface components | Mycolic acid trans-cyclopropane synthetase | cmaA2 | |

| Endotoxin | LOS | lgtA | |

| Iron uptake | Pyoverdine receptors | fpvA | |

| Iron uptake | Vibriobactin biosynthesis | vibA | |

| Iron uptake | Yersiniabactin siderophore | irp1, irp2, ybtE, ybtQ, ybtS, ybtT, ybtU, ybtX | |

| Secretion system | EPS type II secretion system | epsG | |

| Secretion system | Trw type IV secretion system | trwE | |

| Secretion system | VirB/VirD4 type IV secretion system & translocated effector Beps | virB11, virB4, virB9 | |

| Toxin | RTX toxin | rtxB, rtxD | |

| KP617 and PittNDM01 | Adhesin | Streptococcal collagen-like proteins | sclB |

| Chemotaxis and motility | Flagella | flrC | |

| Iron uptake | Yersiniabactin siderophore | fyuA |

KP617 and PittNDM01 were found to possess two virulence factors that were not present in the other two strains: invasion (encoded by ail, attachment invasion locus protein) [42] and Iron uptake (encoded by fyuA, Yersiniabactin siderophore) [43].

Phage-associated regions

Prophages contribute to the genetic and phenotypic plasticity of their bacterial hosts [44] and act as vehicles for the transfer of antimicrobial resistance genes [45] or virulence factors [46]. Six phage-associated regions (KC1–KC5) of the KP617 chromosome and one phage-associated region (KP1) in plasmid 1 of the KP617 strain were identified using the PHAST algorithm (Table 4). With regard to the reference strains, six phage-associated regions were identified in the PittNDM01 strain, six in NUHL24835, and 12 in ATCC BAA-2146.

Table 4.

Phage-associated regions of KP617 and the reference strains

| Strain | Chromosome/plasmid | Region | Region_length (Kb) | Completeness | Score | #CDS | Region_position | Possible phage | GC_percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATCC BAA-2146 | Chromosome | AC1 | 23.3 | Questionable | 75 | 14 | 596765–620097 | Entero_P4 | 43.01 |

| Chromosome | AC2 | 52 | Intact | 100 | 70 | 1293924–1345940 | Cronob_ENT47670 | 53.06 | |

| Chromosome | AC3 | 37.5 | Intact | 150 | 48 | 1785522–1823022 | Entero_Fels_2 | 51.11 | |

| Chromosome | AC4 | 25.7 | Incomplete | 50 | 31 | 2283748–2309524 | Entero_mEpX1 | 52.98 | |

| Chromosome | AC5 | 45.6 | Intact | 110 | 62 | 2342458–2388075 | Salmon_SEN34 | 51.79 | |

| Chromosome | AC6 | 7 | Incomplete | 30 | 7 | 3543581–3550658 | Shigel_SfIV | 48.73 | |

| Chromosome | AC7 | 45.1 | Intact | 106 | 57 | 3969834–4015015 | Salmon_SPN1S | 54.61 | |

| Chromosome | AC8 | 24.7 | Intact | 150 | 31 | 4128565–4153295 | Salmon_RE_2010 | 56.56 | |

| Chromosome | AC9 | 25.7 | Questionable | 90 | 26 | 4910621–4936374 | Salmon_ST64B | 52.32 | |

| Plasmid1 | AP1-1 | 16 | Questionable | 70 | 13 | 5385–21439 | Staphy_SPbeta_like | 57.65 | |

| Plasmid2 | AP2-1 | 46 | Intact | 130 | 38 | 3924–49935 | Stx2_converting_1717 | 51.29 | |

| Plasmid2 | AP2-2 | 18.1 | Questionable | 70 | 23 | 37308–55427 | Staphy_SPbeta_like | 50.68 | |

| Plasmid2 | AP2-3 | 18.7 | Incomplete | 30 | 21 | 66337–85097 | Entero_P1 | 51.85 | |

| KP617 | Chromosome | KC1 | 59.4 | Intact | 140 | 78 | 187337–246765 | Salmon_E1 | 53.99 |

| Chromosome | KC2 | 52.2 | Intact | 150 | 51 | 1148902–1201105 | Entero_HK140 | 54.02 | |

| Chromosome | KC3 | 37.3 | Intact | 150 | 39 | 1524848–1562220 | Salmon_SEN4 | 50.97 | |

| Chromosome | KC4 | 43.1 | Questionable | 90 | 52 | 4912300–4955407 | Escher_HK639 | 52.40 | |

| Chromosome | KC5 | 20 | Incomplete | 30 | 17 | 5015118–5035178 | Entero_phiP27 | 51.93 | |

| Plasmid1 | KP1-1 | 20.7 | Incomplete | 50 | 25 | 123005–143753 | Escher_Av_05. | 0.4718 | |

| NUHL24835 | Chromosome | NC1 | 41.6 | Intact | 140 | 47 | 132925–174606 | Entero_HK140 | 50.75 |

| Chromosome | NC2 | 12.8 | Incomplete | 30 | 14 | 1481474–1494341 | Thermu_phiYS40 | 58.36 | |

| Chromosome | NC3 | 34.7 | Intact | 150 | 32 | 1524859–1559640 | Entero_c_1 | 52.15 | |

| Chromosome | NC4 | 41.9 | Intact | 150 | 52 | 4283813–4325722 | Entero_Fels_2 | 53.26 | |

| Chromosome | NC5 | 38.7 | Intact | 150 | 45 | 5082826–5121566 | Entero_mEp235 | 50.24 | |

| Plasmid1 | NP1-1 | 21.4 | Incomplete | 30 | 6 | 65638–87083 | Entero_P1 | 49.29 | |

| PittNDM01 | Chromosome | PC1 | 50.8 | Intact | 130 | 63 | 209103–259953 | Vibrio_pYD38_A | 53.35 |

| Chromosome | PC2 | 49.9 | Intact | 120 | 65 | 4847596–4897574 | Salmon_SPN3UB | 51.59 | |

| Chromosome | PC3 | 20 | Incomplete | 30 | 19 | 4961006–4981067 | Entero_P4 | 51.92 | |

| Plasmid1 | PP1-1 | 30.8 | Questionable | 70 | 22 | 124082–154939 | Vibrio_pYD38_A | 48.18 | |

| Plasmid2 | PP2-1 | 34.3 | Questionable | 70 | 27 | 556–34952 | Entero_P1 | 52.30 | |

| Plasmid3 | PP3-1 | 50.3 | Intact | 150 | 56 | 8885–59236 | Entero_P1 | 53.90 |

Three of the six phages, KC1, KC2 and KC3, in the KP617 strain were intact, whereas the remaining prophages were incomplete (KC5 and KP1) or questionable (KC4) and had a low PHAST score of below 90. Based on the sequence similarity of their genomes, KP617 and PittNDM01 were found to have high similarity to each other (Figs. 2, 3a, b). Concordantly, the profile of prophage DNA in their genomes, as determined via a BLAST search, was similar, and the two strains shared four of the six prophages, whereas two phage regions, KC2 (Entero_HK140) and KC3 (Salmon_SEN4), were specific to the KP617 genome. Furthermore, it was found that one phage-associated region of KP617, namely KC2 (Entero_HK140), exhibited a high similarity to the phage-associated region of the NUHL24835 strain, NC1, with 60 % query coverage and 99 % identity. It should be noted that the strains compared in the present study, i.e. KP617 and the reference strain, ATCC BAA-2146, had no prophages in common.

Investigation of the antimicrobial resistance genes harbored by the strains, which was performed using ResFinder, and comparison with the prophage-associated region, as predicted using PHAST, did not reveal the presence of a prophage-delivered beta-lactamase-encoding gene in the KP617 genome, indicating that prophages did not act as a vehicle for the transfer of antimicrobial resistance genes in this strain. This finding is consistent with previous observations that beta-lactamase-encoding genes are borne by transposons [35, 36]. Bacteriophages are applicable to phage therapy. In particular, bacteriophages have been used as a potential therapeutic agent to treat patients infected with multidrug resistant bacteria [47] and have been used for serological typing for diagnostic and epidemiological typing in K. pneumoniae [48]. However, because we did not characterize the phages in KP617, we are not sure whether or not they are active.

Future directions

Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae KP617, which is strongly pathogenic, is known to cause severe nosocomial infections. This strain, as well as the PittNDM01 and NUHL24835 strains in the WGLW2 group, belongs to the sequence type ST14. In this study, we investigated specific antimicrobial resistance genes, virulence factors, and prophages related to pathogenicity and drug resistance in K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae KP617 via a comparative analysis of the genome of this strain and those of PittNDM01, NUHL24835, and ATCC BAA-2146. Significant homology was observed in terms of the genomic structure, gene content, antimicrobial resistance genes and virulence factors between KP617 and the reference strains; phylogenetic analysis indicated that KP617 is next to PittNDM01, despite the presence of large inversions. Moreover, KP617 shares 98.3 % of its genes with PittNDM01. Despite the similarity in genome sequences and content, there were differences in phage-related genes, plasmids, and plasmid-harbored antimicrobial resistance genes. PittNDM01 harbors two more plasmids and 21 more antimicrobial resistance genes than KP617. In order to elucidate the precise role of these factors in the pathogenicity of KP617, further studies are required.

Availability of supporting data

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers The complete genome sequence of K. pneumoniae KP617 has been deposited in DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession numbers CP012753, CP012754, and CP012755 [49].

Authors’ contributions

DWK and WK designed and led the project and contributed to the interpretation of the results. DWK drafted the manuscript. YHJ and TK interpreted the results. YHJ, SHL, MRY, and TK performed the gene annotation and bioinformatics analysis. TK and YHJ wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript before submission.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Marine Biotechnology Program (Genome Analysis of Marine Organisms and Development of Functional Applications) funded by the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries.

Abbreviations

- BSR

BLAST score ratio

- CDS

coding DNA sequences

- HGT

horizontal gene transfer

- MLST

multi-locus sequence typing

- NDM-1

New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase 1

- RAST

Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology

- ST

sequence type

- str

strain

- substr

substrain

Additional file

10.1186/s13099-016-0117-1 Annotated genes of KP617 and comparison of their sequences with those of the reference strains by using the RAST server.

Footnotes

Taesoo Kwon and Young-Hee Jung contributed equally to this work

Won Kim and Dae-Won Kim contributed equally to the work

Contributor Information

Taesoo Kwon, Email: joshuakwon@gmail.com.

Young-Hee Jung, Email: magic107@hanmail.net.

Sanghyun Lee, Email: cdcsanghyun@gmail.com.

Mi-ran Yun, Email: tkaleth3927@gmail.com.

Won Kim, Email: wonkim@plaza.snu.ac.kr.

Dae-Won Kim, Email: todaewon@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Podschun R, Ullmann U. Klebsiella spp. as nosocomial pathogens: epidemiology, taxonomy, typing methods, and pathogenicity factors. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11(4):589–603. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.4.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yinnon AM, Butnaru A, Raveh D, Jerassy Z, Rudensky B. Klebsiella bacteraemia: community versus nosocomial infection. QJM. 1996;89(12):933–941. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/89.12.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta N, Limbago BM, Patel JB, Kallen AJ. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: epidemiology and prevention. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(1):60–67. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poirel L, Heritier C, Tolun V, Nordmann P. Emergence of oxacillinase-mediated resistance to imipenem in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48(1):15–22. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.1.15-22.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Queenan AM, Bush K. Carbapenemases: the versatile beta-lactamases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20(3):440–458. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00001-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rogers BA, Sidjabat HE, Silvey A, Anderson TL, Perera S, Li J, Paterson DL. Treatment options for New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase-harboring enterobacteriaceae. Microb Drug Resist. 2013;19(2):100–103. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2012.0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gyles C, Boerlin P. Horizontally transferred genetic elements and their role in pathogenesis of bacterial disease. Vet Pathol. 2014;51(2):328–340. doi: 10.1177/0300985813511131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nordmann P, Poirel L. The difficult-to-control spread of carbapenemase producers among Enterobacteriaceae worldwide. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(9):821–830. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nordmann P, Naas T, Poirel L. Global spread of Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17(10):1791–1798. doi: 10.3201/eid1710.110655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yong D, Toleman MA, Giske CG, Cho HS, Sundman K, Lee K, Walsh TR. Characterization of a new metallo-beta-lactamase gene, bla(NDM-1), and a novel erythromycin esterase gene carried on a unique genetic structure in Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 14 from India. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53(12):5046–5054. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00774-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qu H, Wang X, Ni Y, Liu J, Tan R, Huang J, Li L, Sun J. NDM-1-producing Enterobacteriaceae in a teaching hospital in Shanghai, China: IncX3-type plasmids may contribute to the dissemination of blaNDM-1. Int J Infect Dis. 2015;34:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Potron A, Rondinaud E, Poirel L, Belmonte O, Boyer S, Camiade S, Nordmann P. Genetic and biochemical characterisation of OXA-232, a carbapenem-hydrolysing class D beta-lactamase from Enterobacteriaceae. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2013;41(4):325–329. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans BA, Amyes SG. OXA beta-lactamases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27(2):241–263. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00117-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balm MN, La MV, Krishnan P, Jureen R, Lin RT, Teo JW. Emergence of Klebsiella pneumoniae co-producing NDM-type and OXA-181 carbapenemases. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19(9):E421–423. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doi Y, O’Hara JA, Lando JF, Querry AM, Townsend BM, Pasculle AW, Muto CA. Co-production of NDM-1 and OXA-232 by Klebsiella pneumoniae. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(1):163–165. doi: 10.3201/eid2001.130904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwon T, Yang JW, Lee S, Yun MR, Yoo WG, Kim HS, Cha JO, Kim DW. Complete genome sequence of Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae KP617, Coproducing OXA-232 and NDM-1 Carbapenemases, isolated in South Korea. Genome Announc. 2016;4(1):e01550–15. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01550-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doi Y, Hazen TH, Boitano M, Tsai YC, Clark TA, Korlach J, Rasko DA. Whole-genome assembly of Klebsiella pneumoniae coproducing NDM-1 and OXA-232 carbapenemases using single-molecule, real-time sequencing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(10):5947–5953. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03180-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.(KCDC) KCfDCaP Epidemic investigation report for imported CRE outbreak in Korea. Public Health Wkly Rep KCDC. 2013;6(31):617–619. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu PP, Liu Y, Wang LH, Wei DD, Wan LG. Draft genome sequence of an NDM-5-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 14 strain of serotype K2. Genome Announc. 2016;4(2):e01610-15. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01610-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hudson CM, Bent ZW, Meagher RJ, Williams KP. Resistance determinants and mobile genetic elements of an NDM-1-encoding Klebsiella pneumoniae strain. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e99209. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Myers EW, Sutton GG, Delcher AL, Dew IM, Fasulo DP, Flanigan MJ, Kravitz SA, Mobarry CM, Reinert KH, Remington KA, et al. A whole-genome assembly of Drosophila. Science. 2000;287(5461):2196–2204. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hackl T, Hedrich R, Schultz J, Forster F. proovread: large-scale high-accuracy PacBio correction through iterative short read consensus. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(21):3004–3011. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, DeJongh M, Disz T, Edwards RA, Formsma K, Gerdes S, Glass EM, Kubal M, et al. The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genom. 2008;9:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khan NH, Ahsan M, Yoshizawa S, Hosoya S, Yokota A, Kogure K. Multilocus sequence typing and phylogenetic analyses of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from the ocean. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74(20):6194–6205. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02322-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glaeser SP, Kampfer P. Multilocus sequence analysis (MLSA) in prokaryotic taxonomy. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2015;38(4):237–245. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Angiuoli SV, Salzberg SL. Mugsy: fast multiple alignment of closely related whole genomes. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(3):334–342. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tavaré S. Some probabilistic and statistical problems in the analysis of DNA sequences. Lect Math Life Sci. 1986;17:57–86. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stamatakis A. Phylogenetic models of rate heterogeneity: a high performance computing perspective. In: Parallel and distributed processing symposium, 2006 IPDPS 2006 20th international. 2006.

- 29.Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP. FastTree: computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol Biol Evol. 2009;26(7):1641–1650. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sullivan MJ, Petty NK, Beatson SA. Easyfig: a genome comparison visualizer. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(7):1009–1010. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zankari E, Hasman H, Cosentino S, Vestergaard M, Rasmussen S, Lund O, Aarestrup FM, Larsen MV. Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(11):2640–2644. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen L, Yang J, Yu J, Yao Z, Sun L, Shen Y, Jin Q. VFDB: a reference database for bacterial virulence factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33((Database issue)):D325–328. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou Y, Liang Y, Lynch KH, Dennis JJ, Wishart DS. PHAST: a fast phage search tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39((Web Server issue)):W347–352. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rayamajhi N, Kang SG, Lee DY, Kang ML, Lee SI, Park KY, Lee HS, Yoo HS. Characterization of TEM-, SHV- and AmpC-type beta-lactamases from cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolated from swine. Int J Food Microbiol. 2008;124(2):183–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brovedan M, Marchiaro PM, Moran-Barrio J, Cameranesi M, Cera G, Rinaudo M, Viale AM, Limansky AS. Complete sequence of a bla(NDM-1)-harboring plasmid in an Acinetobacter bereziniae clinical strain isolated in Argentina. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(10):6667–6669. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00367-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim SY, Rhee JY, Shin SY, Ko KS. Characteristics of community-onset NDM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates. J Med Microbiol. 2014;63(Pt 1):86–89. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.067744-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Campos JC, da Silva MJ, dos Santos PR, Barros EM, Pereira Mde O, Seco BM, Magagnin CM, Leiroz LK, de Oliveira TG, de Faria-Junior C, et al. Characterization of Tn3000, a transposon responsible for blaNDM-1 dissemination among Enterobacteriaceae in Brazil, Nepal, Morocco, and India. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(12):7387–7395. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01458-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim MN, Yong D, An D, Chung HS, Woo JH, Lee K, Chong Y. Nosocomial clustering of NDM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 340 strains in four patients at a South Korean tertiary care hospital. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(4):1433–1436. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06855-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu VL, Hansen DS, Ko WC, Sagnimeni A, Klugman KP, von Gottberg A, Goossens H, Wagener MM, Benedi VJ, International Klebseilla Study AG Virulence characteristics of Klebsiella and clinical manifestations of K. pneumoniae bloodstream infections. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13(7):986–993. doi: 10.3201/eid1307.070187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rietschel ET, Kirikae T, Schade FU, Mamat U, Schmidt G, Loppnow H, Ulmer AJ, Zahringer U, Seydel U, Di Padova F, et al. Bacterial endotoxin: molecular relationships of structure to activity and function. FASEB J. 1994;8(2):217–225. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.8.2.8119492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shu HY, Fung CP, Liu YM, Wu KM, Chen YT, Li LH, Liu TT, Kirby R, Tsai SF. Genetic diversity of capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis in Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates. Microbiology. 2009;155(Pt 12):4170–4183. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.029017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parkhill J, Wren BW, Thomson NR, Titball RW, Holden MT, Prentice MB, Sebaihia M, James KD, Churcher C, Mungall KL, et al. Genome sequence of Yersinia pestis, the causative agent of plague. Nature. 2001;413(6855):523–527. doi: 10.1038/35097083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jacobi CA, Gregor S, Rakin A, Heesemann J. Expression analysis of the yersiniabactin receptor gene fyuA and the heme receptor hemR of Yersinia enterocolitica in vitro and in vivo using the reporter genes for green fluorescent protein and luciferase. Infect Immun. 2001;69(12):7772–7782. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.12.7772-7782.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deghorain M, Van Melderen L. The Staphylococci phages family: an overview. Viruses. 2012;4(12):3316–3335. doi: 10.3390/v4123316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Colomer-Lluch M, Imamovic L, Jofre J, Muniesa M. Bacteriophages carrying antibiotic resistance genes in fecal waste from cattle, pigs, and poultry. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(10):4908–4911. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00535-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O’Brien AD, Newland JW, Miller SF, Holmes RK, Smith HW, Formal SB. Shiga-like toxin-converting phages from Escherichia coli strains that cause hemorrhagic colitis or infantile diarrhea. Science. 1984;226(4675):694–696. doi: 10.1126/science.6387911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kutateladze M, Adamia R. Bacteriophages as potential new therapeutics to replace or supplement antibiotics. Trends Biotechnol. 2010;28(12):591–595. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hsu CR, Lin TL, Pan YJ, Hsieh PF, Wang JT. Isolation of a bacteriophage specific for a new capsular type of Klebsiella pneumoniae and characterization of its polysaccharide depolymerase. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e70092. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kwon T, Cho SH. Draft genome sequence of Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157 NCCP15739, isolated in the Republic of Korea. Genome Announc. 2015;3(3):e00522-15. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00522-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]