Abstract

The covalent attachment of ubiquitin to target proteins is one of the most prevalent post-translational modifications, regulating a myriad of cellular processes including cell growth, survival, and metabolism. Recently, a novel RING E3 ligase complex was described, called linear ubiquitin assembly complex (LUBAC), which is capable of connecting ubiquitin molecules in a novel head-to-tail fashion via the N-terminal methionine residue. LUBAC is a heteromeric complex composed of heme-oxidized iron-responsive element-binding protein 2 ubiquitin ligase-1L (HOIL-1L), HOIL-1L–interacting protein, and shank-associated RH domain-interacting protein (SHARPIN). The essential role of LUBAC-generated linear chains for activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) signaling was first described in the activation of tumor necrosis factor-α receptor signaling complex. A decade of research has identified additional pathways that use LUBAC for downstream signaling, including CD40 ligand and the IL-1β receptor, as well as cytosolic pattern recognition receptors including nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain containing 2 (NOD2), retinoic acid–inducible gene 1 (RIG-1), and the NOD-like receptor family, pyrin domain containing 3 inflammasome (NLRP3). Even though the three components of the complex are required for full activation of NF-κB, the individual components of LUBAC regulate specific cell type– and stimuli-dependent effects. In humans, autosomal defects in LUBAC are associated with both autoinflammation and immunodeficiency, with additional disorders described in mice. Moreover, in the lung epithelium, HOIL-1L ubiquitinates target proteins independently of the other LUBAC components, adding another layer of complexity to the function and regulation of LUBAC. Although many advances have been made, the diverse functions of linear ubiquitin chains and the regulation of LUBAC are not yet completely understood. In this review, we discuss the various roles of linear ubiquitin chains and point to areas of study that would benefit from further investigation into LUBAC-mediated signaling pathways in lung pathophysiology.

Keywords: LUBAC, nondegradative ubiquitination, inflammation

First described in the 1980s, ubiquitination, the addition of ubiquitin molecules to a substrate protein, is a predominant post-translational modification regulating cellular homeostasis (1). Ubiquitination can target proteins for degradation via the proteasome or selective autophagy, alter subcellular location, affect activity, and regulate interactions with other proteins (2). Therefore, dysregulation of ubiquitin signaling or functional impairment of the proteasome can lead to many diseases.

Ubiquitin Proteasomal Pathway

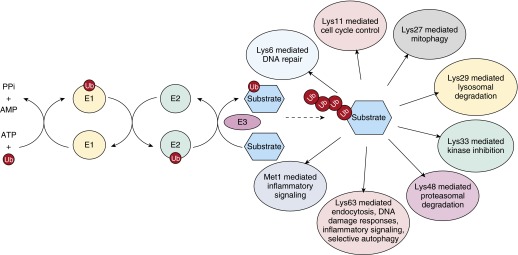

Three classes of enzymes mediate the formation of ubiquitin chains: ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1s), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2s), and ubiquitin ligases (E3s). As described in Figure 1, the enzymatic cascade leading to ubiquitin chain formation begins when E1 binds ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner. Activated ubiquitin is then transferred to an E2 and then, via a substrate-specific E3 ligase, the ubiquitin molecule is transferred to a target protein. Repetition of this sequential ubiquitin transfer, attaching the C- terminal glycine residue of the next ubiquitin to the ε-amino group of a substrate lysine residue, results in ubiquitin chains of various lengths (3). The human genome encodes two E1s, 35 E2s, and more than 600 E3 ligases (4–6). The diversity of E3 ligases enables their specificity in targeting protein substrates (7). E3 ligases fall into two broad categories: homologous to E6AP carboxyl terminus (HECT) or really interesting new gene (RING) ligases (8). HECT ligases, accounting for less than 10% of human E3s, form a covalent bond with ubiquitin from E2 before its transfer to the substrate protein, a situation in which the E3 is largely responsible for determining linkage specificity. In contrast, the more common RING ligases act as a scaffold, bringing the E2 and substrate protein together to facilitate ubiquitination and allowing for E2 to determine linkage type (9).

Figure 1.

The ubiquitination enzymatic cascade generates diverse ubiquitin chains capable of differentially affecting numerous cellular processes (24). Ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1) transfers ubiquitin in an ATP-dependent manner to the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2). The ubiquitin ligase (E3) then transfers ubiquitin molecules to the substrate. Repetition of this sequential ubiquitin transfer results in ubiquitin chains of various lengths, with each linkage type conferring differential downstream signaling (3). AMP, adenosine monophosphate; Lys, lysine residue; Met1, N-terminal methionine; PPi, pyrophosphate; Ub, ubiquitin.

Of its 76 amino acids, each ubiquitin molecule contains seven lysine residues (Lys6, Lys11, Lys27, Lys29, Lys33, Lys48, and Lys63), to which additional ubiquitin can be linked to form chains of various length with different functions, as depicted in Figure 1 (2). Of these, Lys48-linked chains, which target proteins for proteasome-dependent degradation, have been the most studied (10, 11). Most nonproteolytic roles of ubiquitin chains are related to Lys63-linked ubiquitin polymers, which function as signaling scaffolds in nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) signaling, DNA repair, and intracellular trafficking (12, 13). Lys63 polyubiquitin chains have also been identified as directing selective autophagy through the recruitment of the ubiquitin-binding proteins such as p62, neighbor of BRCA1 gene 1 (NBR1) or histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6), which trigger the formation inclusion bodies within the autophagic pathway (14–16). Less is known about the pathophysiological function of Lys6-, Lys11-, Lys27-, Lys29-, and Lys33-linked chains (17, 18). It has been suggested that Lys6-linked ubiquitin chains function in a nondegradative capacity, because proteasome inhibition does not result in increased abundance of cellular Lys6 polyubiquitin (19, 20). Specifically, Lys6 chains have been observed within DNA damage-repair complexes, which suggests a possible physiological role (21). Conversely, upon proteasome inhibition, abundance of Lys11, Lys27, Lys29, and Lys33 chains increases, which suggests proteasome signaling (20). Abundance of Lys11 polyubiquitin chains also increases as cells exit mitosis, which suggests an as-yet-unidentified role in the cell cycle (22). Lys27 has been observed in conjunction with mitochondrial damage, covalently attached to voltage-dependent anion channel 1 to facilitate selective autophagy of mitochondria (mitophagy) in a manner similar to that of the Lys63 chains described previously (23). Because of low abundance and limited linkage-specific tools, the function of Lys29 and Lys33 remains unclear (24). However, there have been reports of Lys29 chains on NF-κB essential modulator (NEMO) that target it for lysosomal degradation (25) and Lys33 linkages on several AMP-activated protein kinase–related protein kinases where it dampens their activity (26). On the basis of the topography of the chains, differentially linked ubiquitin chains can be classified as either compact or open conformations, which, in turn, determine the fate and/or function of the tagged protein (24). For example, Lys48-linked polyubiquitin chains form a globular structure that is recognized by the proteasome and serves as a signal for degradation, whereas Lys63-linked polyubiquitin chains have a more elongated topography and function in nondegradative signal transduction pathways in which they act as scaffolds for protein recruitment (27, 28). As the ubiquitination field evolves, new processes mediated by diverse ubiquitin linkages will continue to be described.

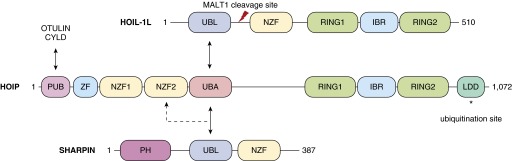

In addition to the seven internal lysine residues, the N-terminal methionine residue (Met1) of ubiquitin has been identified as a new linkage site. Iwai and colleagues described a novel RING E3 ligase complex capable of connecting ubiquitin molecules in this head-to-tail fashion (29). Met1 linked linear chains are formed by the linear ubiquitin assembly complex (LUBAC), a 600-kD E3 ligase complex composed of two RING-between-RING (RBR) ligases—the heme-oxidized iron-responsive element-binding protein 2 ubiquitin ligase-1L (HOIL-1L), and the HOIL-1L–interacting protein (HOIP)—in addition to shank-associated RH domain-interacting protein (SHARPIN) (30–32). The proteins within the heteromeric complex contain multiple domains for interactions within the complex, for ubiquitin binding, and for catalytic activity. As shown in Figure 2, the ubiquitin-like (UBL) domain of HOIL-1L interacts with the ubiquitin-associated domain of HOIP to enhance complex formation (33). HOIL-1L also contains a unique zinc finger domain (Npl4 zinc finger [NZF]), specifically oriented to detect the distinct spacing of hydrophobic patches between proximal and distal ubiquitin moieties linked in linear chains (34). Although HOIL-1L also contains functional RING domains, in vitro ubiquitination assays have shown that its rate of linear chain formation is slow (35). However, independent of LUBAC, the RBR of HOIL-1L has been shown to add Lys48 polyubiquitin chains to target proteins (36, 37). The RBR domain of HOIP is responsible for the generation of linear chains (29). Unlike the formation of lysine-linked chains by other RING ligases, linear chain formation is determined by the E3 ligase rather than by the E2 conjugating enzyme, and it has been suggested that a “HECT-like” ubiquitin transfer is involved (38). HOIP contains three zinc finger domains that function in ubiquitin binding as well as in interactions with target protein substrates and the third member of the complex, SHARPIN. Although HOIP can also bind the SHARPIN ubiquitin-associated domain via its UBL domain, both the UBL and NZF domain of SHARPIN have been shown to be necessary for interactions with HOIP (39). The exact stoichiometry of LUBAC remains unknown; however, in vitro ubiquitination assays show that HOIP is active when in complex with SHARPIN or HOIL-1L alone but it is maximally active when bound to both components, possibly because of an interaction that releases autoinhibitory folding of HOIP (29, 35). In addition to being necessary for maximal HOIP activity, complex formation has also been observed to stabilize the expression of each component within the cell by inhibiting proteasomal degradation (40, 41).

Figure 2.

Schematic of linear ubiquitin assembly complex (LUBAC) components and interaction domains. LUBAC is composed of two RING-between-RING ligases: heme-oxidized iron responsive element binding protein 2 ubiquitin lipase-1 (HOIL-1L), the HOIL-1L–interacting protein (HOIP), and SHARPIN (30–32). HOIL-1L and HOIP both contain RING-between-RING domains, whereas only HOIP is catalytically active. Multiple interaction domains exist within the complex: the ubiquitin-associated (UBA) domain of HOIP interacts with the ubiquitin-like (UBL) domain of HOIL-1L and SHARPIN. The NZF domains of each protein facilitate ubiquitin binding. The PUB domain of HOIP is also responsible for interaction with the deubiquitinases ovarian tumor deubiquitinating enzyme with linear linkage specificity (OTULIN) and cylindromatosis (CYLD) (60). *Ubiquitination site. IBR, in between RING; LDD, linear ubiquitin chain determining domain; MALT1, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma translocation gene 1; NZF, Npl4 zinc finger; PH, pleckstrin-homology; PUB, peptide N-glycanase; RING, really interesting new gene; SHARPIN, shank-associated RH domain-interacting protein; ZF, zinc finger.

Physiological Roles of Linear Ubiquitin Chains

Physiological roles for linear chains were first described downstream of tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (TNFR1) activation which, through interactions with NEMO, facilitates the robust activation of NF-κB (42). Upon ligand stimulation, multiple proteins, including several ubiquitin ligases that attach Lys63-linked polyubiquitin chains to various substrates, are recruited to the TNFR1 signaling complex (TNF-RSC). These anchored Lys63-linked ubiquitin chains create a signaling scaffold to which LUBAC binds (42). Once recruited to the TNF-RSC, LUBAC covalently attaches linear ubiquitin chains to NEMO, a component together with IKKα and IKKβ of the IκB kinase (IKK) complex. Because of the high affinity of NEMOs UBAN domain (ubiquitin binding in ABIN and NEMO) for linear chains, linear ubiquitination of NEMO facilitates the recruitment of additional IKK complexes to the TNF-RSC (43). Stably docked IKK complexes result in the efficient transautophosphorylation and activation of proximal IKKα/β, followed by the phosphorylation and degradation of the inhibitor of NF-κB (44). Activation of NF-κB downstream of IKK activation occurs in response to a variety of stimuli; as such, further investigations have revealed the necessity of LUBAC for signaling downstream of the IL-1 receptor, CD40, and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain containing 2 (NOD2) stimulation (45). However, LUBAC recruitment to these signaling complexes may require differential minimal components, many of which have yet to be identified (46).

LUBAC has also been implicated as affecting inflammation on additional host response pathways. The retinoic acid–inducible gene 1 (RIG-I) pathway senses viral replication within infected cells to activate pro-inflammatory (NF-κB) and anti-viral signaling (interferon response) cascades (47). Upon recognition of viral double-stranded RNA by RIG-I, tripartite motif 25 (TRIM25) attaches Lys63 chains to activated RIG-1 to facilitate downstream mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein (MAVS) binding and subsequent NEMO-dependent antiviral signaling (47). Recent studies have suggested that LUBAC interferes with RIG-I signaling by promoting the degradation of TRIM25 and/or inhibits MAVS complex formation in response to Sendai virus (48, 49). However, in response to vesicular stomatitis virus, where loss of LUBAC had only modest effects on interferon production, Liu and colleagues revealed a role for LUBAC in supporting MAVS signaling (50). The authors suggest that ubiquitination targets of LUBAC may function redundantly with ubiquitination by TNF receptor-associated factor 2 (TRAF2) in interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) activation (50). Despite diverging host response reports, these studies suggest new proteins with which LUBAC interacts.

LUBAC is also required for inflammasome activation and assembly in bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDM) independent from LUBAC’s ability to modulate NF-κB signaling (51). The NLRP3 inflammasome is an oligomeric signaling complex composed of NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase activating and recruiting domain (ASC), and caspase-1, which detects cytosolic danger signals in myeloid-lineage cells and processes pro–IL-1β and pro–IL-18 to active cytokines for immediate secretion and inflammatory action (52). Studies of LUBAC’s role in inflammasome signaling have identified ASC as a novel substrate of linear ubiquitination and show that the HOIL-1L–HOIP interaction is necessary for these processes (51). Recent studies have also established a critical function of SHARPIN showing that macrophages isolated from SHARPIN null mice have impaired inflammasome activation (53).

In addition to the E3 ligase activity of HOIP, a recent report suggests a catalytic-independent role of LUBAC in lymphocytes (54, 55). In a lymphoma model, LUBAC was shown to be a critical factor linking T-cell receptor engagement to NF-κB activation, such that lack of HOIP, SHARPIN, or to a lesser extent, HOIL-1L, resulted in a blunted NF-κB response (54, 55). However, unlike treatment with tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), linear polyubiquitin chain formation failed to be detected and the observed HOIP-null phenotype was rescued with a catalytically inactive mutant construct (54, 55). While further demonstrating the importance of LUBAC in inflammatory signaling, in the case of T-cell receptor ligation, LUBAC may provide a scaffolding, rather than an enzymatic, function.

The regulation of inflammatory signaling is critical for the maintenance of homeostasis, because aberrant NF-κB activity can lead to tissue damage and oncogenesis (56). As a key component of downstream NF-κB activity, linear ubiquitination appears to be critical in disease regulation (57). One way in which the physiological effects of ubiquitination are modulated is through specific deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) that recognize and disassemble ubiquitin chains (58). Ovarian tumor DUB with linear linkage specificity (OTULIN) and cylindromatosis (CYLD) have been identified as DUBs specific to the deconstruction of linear ubiquitin chains (59). These DUBs have been shown to interact directly with HOIP to regulate linear chain abundance and TNF-α–stimulated NF-κB activation (Figure 2) (59). CYLD has been shown to cleave Lys63 ubiquitin chains in addition to N-terminal methionine linear chains, whereas OTULIN is specific for linear ubiquitin chain degradation. It has been suggested that OTULIN, through its interaction with HOIP, may be an additional LUBAC component in the basal state, continuously balancing the complex activity until, upon stimulation, it is phosphorylated and detaches from the complex, becoming active (60). Supporting this, data show that in the absence of OTULIN, cells in a basal state spontaneously accumulate linear chains on LUBAC, which becomes more exaggerated in response to TNF-α stimulation (61).

In addition to DUBs, the paracaspase mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma translocation gene 1 (MALT1) has been shown to target HOIL-1L to disrupt complex activity downstream of NF-κB activation in lymphoid cells (62). After cleavage by MALT1, the C-terminal fragment of HOIL-1L disengages from the complex, whereas the N-terminal fragment remains bound to HOIP (Figure 2). However, because the C-terminal fragment, containing the NZF domain, is required for binding and positioning linear chains proximal to HOIP, loss of this fragment results in decreased LUBAC efficiency and thus reduced NF-κB.

Recently, it has been reported that LUBAC enzymatic activity is also regulated by post-translational modifications of HOIP (Figure 2) (63). Bowman and colleagues showed that, when nondegradative ubiquitin chains are attached to Lys1056, a conformational change is triggered that inhibits the ligase activity of HOIP. Conversely, a single amino acid substitution at this location (K1056R) prevents ubiquitination and results in a constitutively active LUBAC and corresponds to increased abundance of linear chains in resting and LPS-stimulated B cells (63). Together, these studies highlight the diverse pathways engaged in maintaining tight control over NF-κB activation downstream of LUBAC.

LUBAC Components and Disease

Autosomal defects in LUBAC are associated with autoinflammation and immunodeficiency, and patients with these mutations develop atypical disease courses (64). Autoinflammation in patients with LUBAC deficiency is characterized by recurrent fever with hepatosplenomegaly and lymphadenopathy at an early age, yet these patients do not develop additional hallmarks such as pleuritis, pericarditis, peritonitis, or neutrophilic dermatoses (65). These patients are prone to recurrent pyogenic infections and an abnormal antiviral host response. Fibroblast and lymphocytes isolated from these patients show diminished NF-κB activation, and monocytes have enhanced sensitivity to IL-1β stimulation, similar to that which has been described in experimental models. When subjected to allogenic engraftment of myeloid and lymphoid compartments, one patient was protected from pyogenic infection and systemic inflammation (65). The complex syndromes exhibited by these patients highlight the cell type–specific function of linear ubiquitination, which may contribute to this unique presentation of symptoms.

The essential role of LUBAC-generated linear chains on NEMO for the activation of NF-κB signaling in response to inflammatory stimuli has been well established (32). In addition, the loss of individual components of LUBAC leads to cell-type and stimuli-dependent effects (37–40). This can be best appreciated in mouse models of LUBAC deficiency in which HOIP-null mice fail to develop past midgestation (E10.5) because of aberrant endothelial cell death, which impairs vascularization (66). Although SHARPIN-deficient mice (cpdm mice) are viable, they exhibit severe multiorgan inflammation and chronic proliferative dermatitis (67). The aberrant apoptotic pathways in both of these mice can be corrected with concurrent TNFR1 ablation (66, 67). Conversely, naive HOIL-1L−/− mice are viable and show no overt phenotype compared with their wild-type (WT) counterparts (68). Interestingly, HOIL-1L knockout mice presented immunodeficiency on infection with Listeria monocytogenes, Citrobacter rodentium, or Toxoplasma gondii, whereas exposure to murine C-herpesvirus 68 or Mycobacterium tuberculosis was met with hyperinflammation (69). In addition, studies done in BMDM derived from mice lacking SHARPIN exhibit NF-κB defects classically associated with a loss of LUBAC function (70). However, HOIL-1L–deficient BMDMs respond to TNF-α stimulation in a similar manner to their WT counterparts (51). These phenotypic differences support the reasoning that HOIL-1L and SHARPIN may differentially contribute to complex formation and have distinct functions independent of the complex that may vary by cell type (69).

Although SHARPIN lacks a catalytic domain, it has been shown to interact with other proteins to affect physiological responses (69). In addition to binding to HOIP, the UBL domain of SHARPIN has been shown to bind cellular integrins (71). When not bound to HOIP, SHARPIN is a potent inhibitor of β1-integrin function by inhibiting talin binding in a variety of cell types (72). Moreover, HOIL-1L is able to modulate cellular responses through the addition Lys48-linked ubiquitin chains to target proteins via its RBR domain (40). Although LUBAC-independent functions of HOIL-1L have been described in numerous pathways including cell cycle regulation, iron storage, and adaptation to hypoxia in rapidly growing tumors, substrates of HOIL-1L are still being described (37, 73, 74).

In accordance with mouse models of LUBAC deficiency, in vitro investigations have revealed several pathways, including Jun amino-terminal kinase (JNK) and NF-κB, that are differentially affected depending on cell type and stimuli. The differential burden of each LUBAC component within the JNK pathway can be appreciated in studies of LUBAC depletion using a range of cell types and stimuli. In one study, HOIL-1L−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts treated with TNF-α had an unchanged level of JNK phosphorylation in knockout versus WT cells (44). In efforts to clarify the role of LUBAC in JNK signaling, additional investigations show that loss of HOIL-1L or HOIP additional cell lines results in reduced JNK signaling in response to TNF-α (42, 75). However, when exposed to genotoxic stress, HOIP deficiency in a separate cell panel enhanced JNK signaling (75). Collectively, these studies suggest a cell type– and stimuli-dependent task of LUBAC in JNK signaling that necessitates further investigation.

As with observations made in studying the JNK pathway, a cell type– and stimuli-specific NF-κB response has been reported. In contrast to previous studies in several cell lines, where deficiency of one or more LUBAC components impaired NF-κB signaling, as noted previously, the response of HOIL-1L–deficient BMDMs to TNF-α stimulation does not differ from that of WT BMDM (51). The mechanisms behind the differential response to stimuli remain unclear; however, it has been suggested that involvement of different host pathways for coordination with the innate and adaptive responses may play a role (69). It has also been suggested that various amounts of HOIL-1L, HOIP, and SHARPIN exist in different cell types (76). Subsequently, this may contribute to differential stoichiometry in different cell types in response to different stimuli, explaining the signaling differences in LUBAC complex deficiency.

LUBAC and the Lung

A variety of cancers, including colorectal tumors and pancreatic and lung carcinomas, are prone to develop with disruption of ubiquitination events (2, 77). In the lung, the ubiquitin proteasome system plays a critical role in homeostasis and disease, because it is involved in the adaptation to hypoxia through the degradation of the Na,K-ATPase (78, 79) and the regulation of ion balance and fluid transport in cystic fibrosis (80). In addition to the ubiquitin proteasome system, ubiquitin-mediated degradation of proteins through selective autophagy maintains intrinsic mitochondrial stability (81), degradation of intracellular pathogens (82), and maintenance of cilia length (83). Disruption of these pathways contributes to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, susceptibility to respiratory infections, acute lung injury, and pulmonary hypertension (84, 85). Ubiquitin-mediated nondegradative signaling has been shown to modulate the cellular response to ventilator-induced lung injury (86). Furthermore, analysis of the transcriptional profile of lung tissue samples obtained from 43 patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease revealed a set of genes in which ubiquitin pathways were enriched (87)

Little is known about the role of LUBAC components in lung pathophysiology. The assortment of pathways differentially affected by changes in LUBAC component expression may account for the effects seen in different disease states. For example, enhanced LUBAC expression seen in lung metastasis 8 osteosarcoma cells induced higher levels of intracellular adhesion molecule-1 than did the parental Dunn murine osteosarcoma cells, facilitating increased lung metastasis (88). Conversely, mice with an alveolar epithelial specific silencing of HOIL-1L have reduced lung tumor burden (74). Supporting these finding, transcriptional analysis of tumor biopsy specimens from patients with lung adenocarcinoma and glioblastoma revealed differential HOIL-1L expression in which higher HOIL-1L levels correlated with decreased survival (74). It has been suggested that the hypoxic tumor microenvironment drives HOIL-1L expression in a hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)–dependent manner. Although HOIL-1L expression within the tumor microenvironment is maladaptive, on systemic exposure to hypoxia, loss of HOIL-1L expression within the respiratory epithelium results in increased lung injury (79). Alternatively, in response to inflammatory lung injury caused by influenza infection, loss of HOIL-1L, specifically in the murine respiratory epithelium, results in improved survival as compared with its WT counterparts (89). A better understanding of the pathways that use linear chains for signaling will clarify the LUBAC contribution to specific diseases.

Unanswered Questions and Research Opportunities

Linear ubiquitin chains represent a novel atypical nondegradative ubiquitin modification. To date, LUBAC represents the only identified E3 ligase capable of generating these head-to-tail ubiquitin chains. A decade of research has identified diverse physiological roles of LUBAC in NF-κB, JNK, inflammasome, and RIG-I signaling. Although many advances have been made, there remain unanswered questions. As mentioned previously, the stoichiometry of the 600-kD LUBAC complex under homeostatic conditions is unknown. Furthermore, how, and if, stoichiometry changes differentially depend on cell type and stimuli remain to be investigated. In addition, although mechanisms for LUBAC recruitment to the TNF-RSC have been proposed, the minimal signaling complex requirements for recruitment of other signaling complexes have yet to be identified. Likewise, mechanisms of LUBAC activation and signal-dependent increases in LUBAC formation remain poorly understood. Investigations into the effects of linear chains in cellular systems have identified reader proteins that specifically recognize linear chains. Among them, NEMO has been shown to exhibit a 100-fold higher affinity for linear chains, even though it is also able to bind Lys63-linked chains (43, 90). This dual recognition by NEMO opens up the possibility that other readers, classically defined as Lys63 specific, may also bind linear chains that share a similar topography. In addition, a subset of signaling pathways attributed originally to Lys63 chains may indeed be modulated by newly identified linear chains. With its ability to enhance inflammation and inhibit apoptosis, a deeper understanding of LUBAC signaling is necessary to discover additional substrates and pathways that may represent therapeutic targets to treat disease.

In summary, LUBAC activity and its role in lung biology is an emerging area of discovery. This heteromeric complex generates head-to-tail nondegradative linear ubiquitin chains that have been shown to be critical in multiple cellular processes including apoptosis and inflammation. The role of LUBAC and new targets of LUBAC components in lung pathobiology are being actively investigated. Although the identified actions of LUBAC have thus far been limited to immunologic modulation, which is also the case with influenza pneumonitis, the recently described mechanism of the LUBAC component HOIL-1L in lung cancer is important, because it represents an important mechanism of adaptation to hypoxia. It is too early to ascertain how discoveries about the functions of LUBAC will fully impact pulmonary medicine; however, this pathway is amenable to regulation, especially as more selective compounds to modulate each of the LUBAC components are being developed (91).

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants HL48129, HL71643, HL76139.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0014TR on February 5, 2016

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Chen ZJ, Sun LJ. Nonproteolytic functions of ubiquitin in cell signaling. Mol Cell. 2009;33:275–286. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Popovic D, Vucic D, Dikic I. Ubiquitination in disease pathogenesis and treatment. Nat Med. 2014;20:1242–1253. doi: 10.1038/nm.3739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hershko A, Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin system for protein degradation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1992;61:761–807. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.003553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li W, Bengtson MH, Ulbrich A, Matsuda A, Reddy VA, Orth A, Chanda SK, Batalov S, Joazeiro CA. Genome-wide and functional annotation of human E3 ubiquitin ligases identifies MULAN, a mitochondrial E3 that regulates the organelle’s dynamics and signaling. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1487. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michelle C, Vourc’h P, Mignon L, Andres CR. What was the set of ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like conjugating enzymes in the eukaryote common ancestor? J Mol Evol. 2009;68:616–628. doi: 10.1007/s00239-009-9225-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jin J, Li X, Gygi SP, Harper JW. Dual E1 activation systems for ubiquitin differentially regulate E2 enzyme charging. Nature. 2007;447:1135–1138. doi: 10.1038/nature05902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Metzger MB, Pruneda JN, Klevit RE, Weissman AM. RING-type E3 ligases: master manipulators of E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes and ubiquitination. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1843:47–60. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Metzger MB, Hristova VA, Weissman AM. HECT and RING finger families of E3 ubiquitin ligases at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:531–537. doi: 10.1242/jcs.091777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mattiroli F, Sixma TK. Lysine-targeting specificity in ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like modification pathways. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21:308–316. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ciechanover A, Heller H, Elias S, Haas AL, Hershko A. ATP-dependent conjugation of reticulocyte proteins with the polypeptide required for protein degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:1365–1368. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.3.1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chau V, Tobias JW, Bachmair A, Marriott D, Ecker DJ, Gonda DK, Varshavsky A. A multiubiquitin chain is confined to specific lysine in a targeted short-lived protein. Science. 1989;243:1576–1583. doi: 10.1126/science.2538923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spence J, Sadis S, Haas AL, Finley D. A ubiquitin mutant with specific defects in DNA repair and multiubiquitination. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:1265–1273. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.3.1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haglund K, Dikic I. Ubiquitylation and cell signaling. EMBO J. 2005;24:3353–3359. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirkin V, McEwan DG, Novak I, Dikic I. A role for ubiquitin in selective autophagy. Mol Cell. 2009;34:259–269. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kraft C, Peter M, Hofmann K. Selective autophagy: ubiquitin-mediated recognition and beyond. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:836–841. doi: 10.1038/ncb0910-836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaid S, Brandts CH, Serve H, Dikic I. Ubiquitination and selective autophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2013;20:21–30. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ikeda F, Dikic I. Atypical ubiquitin chains: new molecular signals. ‘Protein Modifications: Beyond the Usual Suspects’ review series. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:536–542. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Helzer KT, Hooper C, Miyamoto S, Alarid ET. Ubiquitylation of nuclear receptors: new linkages and therapeutic implications. J Mol Endocrinol. 2015;54:R151–R167. doi: 10.1530/JME-14-0308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim W, Bennett EJ, Huttlin EL, Guo A, Li J, Possemato A, Sowa ME, Rad R, Rush J, Comb MJ, et al. Systematic and quantitative assessment of the ubiquitin-modified proteome. Mol Cell. 2011;44:325–340. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wagner SA, Beli P, Weinert BT, Nielsen ML, Cox J, Mann M, Choudhary C. A proteome-wide, quantitative survey of in vivo ubiquitylation sites reveals widespread regulatory roles. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10:013284. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.013284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morris JR, Solomon E. BRCA1 : BARD1 induces the formation of conjugated ubiquitin structures, dependent on K6 of ubiquitin, in cells during DNA replication and repair. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:807–817. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsumoto ML, Wickliffe KE, Dong KC, Yu C, Bosanac I, Bustos D, Phu L, Kirkpatrick DS, Hymowitz SG, Rape M, et al. K11-linked polyubiquitination in cell cycle control revealed by a K11 linkage-specific antibody. Mol Cell. 2010;39:477–484. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geisler S, Holmström KM, Skujat D, Fiesel FC, Rothfuss OC, Kahle PJ, Springer W. PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy is dependent on VDAC1 and p62/SQSTM1. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:119–131. doi: 10.1038/ncb2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kulathu Y, Komander D. Atypical ubiquitylation - the unexplored world of polyubiquitin beyond Lys48 and Lys63 linkages. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:508–523. doi: 10.1038/nrm3394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zotti T, Uva A, Ferravante A, Vessichelli M, Scudiero I, Ceccarelli M, Vito P, Stilo R. TRAF7 protein promotes Lys-29-linked polyubiquitination of IκB kinase (IKKγ)/NF-κB essential modulator (NEMO) and p65/RelA protein and represses NF-κB activation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:22924–22933. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.215426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Al-Hakim AK, Zagorska A, Chapman L, Deak M, Peggie M, Alessi DR. Control of AMPK-related kinases by USP9X and atypical Lys(29)/Lys(33)-linked polyubiquitin chains. Biochem J. 2008;411:249–260. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hicke L, Schubert HL, Hill CP. Ubiquitin-binding domains. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:610–621. doi: 10.1038/nrm1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Su V, Lau AF. Ubiquitin-like and ubiquitin-associated domain proteins: significance in proteasomal degradation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:2819–2833. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0048-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirisako T, Kamei K, Murata S, Kato M, Fukumoto H, Kanie M, Sano S, Tokunaga F, Tanaka K, Iwai K. A ubiquitin ligase complex assembles linear polyubiquitin chains. EMBO J. 2006;25:4877–4887. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dove KK, Klevit RE. RING-between-RINGs--keeping the safety on loaded guns. EMBO J. 2012;31:3792–3794. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ikeda F, Deribe YL, Skånland SS, Stieglitz B, Grabbe C, Franz-Wachtel M, van Wijk SJ, Goswami P, Nagy V, Terzic J, et al. SHARPIN forms a linear ubiquitin ligase complex regulating NF-κB activity and apoptosis. Nature. 2011;471:637–641. doi: 10.1038/nature09814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tokunaga F, Iwai K. LUBAC, a novel ubiquitin ligase for linear ubiquitination, is crucial for inflammation and immune responses. Microbes Infect. 2012;14:563–572. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yagi H, Ishimoto K, Hiromoto T, Fujita H, Mizushima T, Uekusa Y, Yagi-Utsumi M, Kurimoto E, Noda M, Uchiyama S, et al. A non-canonical UBA-UBL interaction forms the linear-ubiquitin-chain assembly complex. EMBO Rep. 2012;13:462–468. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sato Y, Fujita H, Yoshikawa A, Yamashita M, Yamagata A, Kaiser SE, Iwai K, Fukai S. Specific recognition of linear ubiquitin chains by the Npl4 zinc finger (NZF) domain of the HOIL-1L subunit of the linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:20520–20525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109088108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stieglitz B, Morris-Davies AC, Koliopoulos MG, Christodoulou E, Rittinger K. LUBAC synthesizes linear ubiquitin chains via a thioester intermediate. EMBO Rep. 2012;13:840–846. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tokunaga C, Kuroda S, Tatematsu K, Nakagawa N, Ono Y, Kikkawa U. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel protein kinase C-interacting protein with structural motifs related to RBCC family proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;244:353–359. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamanaka K, Ishikawa H, Megumi Y, Tokunaga F, Kanie M, Rouault TA, Morishima I, Minato N, Ishimori K, Iwai K. Identification of the ubiquitin-protein ligase that recognizes oxidized IRP2. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:336–340. doi: 10.1038/ncb952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smit JJ, Monteferrario D, Noordermeer SM, van Dijk WJ, van der Reijden BA, Sixma TK. The E3 ligase HOIP specifies linear ubiquitin chain assembly through its RING-IBR-RING domain and the unique LDD extension. EMBO J. 2012;31:3833–3844. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ikeda F, Deribe YL, Skånland SS, Stieglitz B, Grabbe C, Franz-Wachtel M, van Wijk SJ, Goswami P, Nagy V, Terzic J, et al. SHARPIN forms a linear ubiquitin ligase complex regulating NF-κB activity and apoptosis. Nature. 2011;471:637–641. doi: 10.1038/nature09814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elton L, Carpentier I, Verhelst K, Staal J, Beyaert R. The multifaceted role of the E3 ubiquitin ligase HOIL-1: beyond linear ubiquitination. Immunol Rev. 2015;266:208–221. doi: 10.1111/imr.12307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tokunaga F, Nakagawa T, Nakahara M, Saeki Y, Taniguchi M, Sakata S, Tanaka K, Nakano H, Iwai K. SHARPIN is a component of the NF-κB-activating linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex. Nature. 2011;471:633–636. doi: 10.1038/nature09815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haas TL, Emmerich CH, Gerlach B, Schmukle AC, Cordier SM, Rieser E, Feltham R, Vince J, Warnken U, Wenger T, et al. Recruitment of the linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex stabilizes the TNF-R1 signaling complex and is required for TNF-mediated gene induction. Mol Cell. 2009;36:831–844. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rahighi S, Ikeda F, Kawasaki M, Akutsu M, Suzuki N, Kato R, Kensche T, Uejima T, Bloor S, Komander D, et al. Specific recognition of linear ubiquitin chains by NEMO is important for NF-κB activation. Cell. 2009;136:1098–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tokunaga F, Sakata S, Saeki Y, Satomi Y, Kirisako T, Kamei K, Nakagawa T, Kato M, Murata S, Yamaoka S, et al. Involvement of linear polyubiquitylation of NEMO in NF-κB activation. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:123–132. doi: 10.1038/ncb1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shimizu Y, Taraborrelli L, Walczak H. Linear ubiquitination in immunity. Immunol Rev. 2015;266:190–207. doi: 10.1111/imr.12309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tarantino N, Tinevez JY, Crowell EF, Boisson B, Henriques R, Mhlanga M, Agou F, Israël A, Laplantine E. TNF and IL-1 exhibit distinct ubiquitin requirements for inducing NEMO-IKK supramolecular structures. J Cell Biol. 2014;204:231–245. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201307172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gack MU, Shin YC, Joo CH, Urano T, Liang C, Sun L, Takeuchi O, Akira S, Chen Z, Inoue S, et al. TRIM25 RING-finger E3 ubiquitin ligase is essential for RIG-I-mediated antiviral activity. Nature. 2007;446:916–920. doi: 10.1038/nature05732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Inn K-S, Gack MU, Tokunaga F, Shi M, Wong LY, Iwai K, Jung JU. Linear ubiquitin assembly complex negatively regulates RIG-I- and TRIM25-mediated type I interferon induction. Mol Cell. 2011;41:354–365. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Belgnaoui SM, Paz S, Samuel S, Goulet ML, Sun Q, Kikkert M, Iwai K, Dikic I, Hiscott J, Lin R. Linear ubiquitination of NEMO negatively regulates the interferon antiviral response through disruption of the MAVS-TRAF3 complex. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:211–222. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu S, Chen J, Cai X, Wu J, Chen X, Wu YT, Sun L, Chen ZJ. MAVS recruits multiple ubiquitin E3 ligases to activate antiviral signaling cascades. eLife. 2013;2:e00785. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rodgers MA, Bowman JW, Fujita H, Orazio N, Shi M, Liang Q, Amatya R, Kelly TJ, Iwai K, Ting J, et al. The linear ubiquitin assembly complex (LUBAC) is essential for NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J Exp Med. 2014;211:1333–1347. doi: 10.1084/jem.20132486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Latz E, Xiao TS, Stutz A. Activation and regulation of the inflammasomes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:397–411. doi: 10.1038/nri3452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gurung P, Lamkanfi M, Kanneganti TD. Cutting edge: SHARPIN is required for optimal NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J Immunol. 2015;194:2064–2067. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dubois SM, Alexia C, Wu Y, Leclair HM, Leveau C, Schol E, Fest T, Tarte K, Chen ZJ, Gavard J, et al. A catalytic-independent role for the LUBAC in NF-κB activation upon antigen receptor engagement and in lymphoma cells. Blood. 2014;123:2199–2203. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-05-504019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Beyaert R. An E3 ubiquitin ligase-independent role of LUBAC. Blood. 2014;123:2131–2133. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-02-556076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ruland J. Return to homeostasis: downregulation of NF-κB responses. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:709–714. doi: 10.1038/ni.2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tokunaga F. Linear ubiquitination-mediated NF-κB regulation and its related disorders. J Biochem. 2013;154:313–323. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvt079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Komander D, Clague MJ, Urbé S. Breaking the chains: structure and function of the deubiquitinases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:550–563. doi: 10.1038/nrm2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Takiuchi T, Nakagawa T, Tamiya H, Fujita H, Sasaki Y, Saeki Y, Takeda H, Sawasaki T, Buchberger A, Kimura T, et al. Suppression of LUBAC-mediated linear ubiquitination by a specific interaction between LUBAC and the deubiquitinases CYLD and OTULIN. Genes Cells. 2014;19:254–272. doi: 10.1111/gtc.12128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Elliott PR, Nielsen SV, Marco-Casanova P, Fiil BK, Keusekotten K, Mailand N, Freund SM, Gyrd-Hansen M, Komander D. Molecular basis and regulation of OTULIN-LUBAC interaction. Mol Cell. 2014;54:335–348. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fiil BK, Damgaard RB, Wagner SA, Keusekotten K, Fritsch M, Bekker-Jensen S, Mailand N, Choudhary C, Komander D, Gyrd-Hansen M. OTULIN restricts Met1-linked ubiquitination to control innate immune signaling. Mol Cell. 2013;50:818–830. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Klein T, Fung SY, Renner S, Blank MA, Dufour A, Kang S, Bolger-Munro M, Scurll JM, Priatel JJ, Schweigler P, et al. The paracaspase MALT1 cleaves HOIL1 reducing linear ubiquitination by LUBAC to dampen lymphocyte NF-κB signalling. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8777. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bowman J, Rodgers MA, Shi M, Amatya R, Hostager B, Iwai K, Gao SJ, Jung JU. Posttranslational modification of HOIP blocks Toll-like receptor 4-mediated linear-ubiquitin-chain formation. MBio. 2015;6:e01777–e15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01777-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Boisson B, Laplantine E, Prando C, Giliani S, Israelsson E, Xu Z, Abhyankar A, Israël L, Trevejo-Nunez G, Bogunovic D, et al. Immunodeficiency, autoinflammation and amylopectinosis in humans with inherited HOIL-1 and LUBAC deficiency. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:1178–1186. doi: 10.1038/ni.2457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Boisson B, Laplantine E, Dobbs K, Cobat A, Tarantino N, Hazen M, Lidov HG, Hopkins G, Du L, Belkadi A, et al. Human HOIP and LUBAC deficiency underlies autoinflammation, immunodeficiency, amylopectinosis, and lymphangiectasia. J Exp Med. 2015;212:939–951. doi: 10.1084/jem.20141130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Peltzer N, Rieser E, Taraborrelli L, Draber P, Darding M, Pernaute B, Shimizu Y, Sarr A, Draberova H, Montinaro A, et al. HOIP deficiency causes embryonic lethality by aberrant TNFR1-mediated endothelial cell death. Cell Reports. 2014;9:153–165. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.08.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rickard JA, Anderton H, Etemadi N, Nachbur U, Darding M, Peltzer N, Lalaoui N, Lawlor KE, Vanyai H, Hall C, et al. TNFR1-dependent cell death drives inflammation in Sharpin-deficient mice. eLife. 2014;3:3. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rahighi S, Ikeda F, Kawasaki M, Akutsu M, Suzuki N, Kato R, Kensche T, Uejima T, Bloor S, Komander D, et al. Specific recognition of linear ubiquitin chains by NEMO is important for NF-κB activation. Cell. 2009;136:1098–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.MacDuff DA, Reese TA, Kimmey JM, Weiss LA, Song C, Zhang X, Kambal A, Duan E, Carrero JA, Boisson B, et al. Phenotypic complementation of genetic immunodeficiency by chronic herpesvirus infection. eLife. 2015;4:4. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ikeda F, Deribe YL, Skånland SS, Stieglitz B, Grabbe C, Franz-Wachtel M, van Wijk SJ, Goswami P, Nagy V, Terzic J, et al. SHARPIN forms a linear ubiquitin ligase complex regulating NF-κB activity and apoptosis. Nature. 2011;471:637–641. doi: 10.1038/nature09814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.De Franceschi N, Peuhu E, Parsons M, Rissanen S, Vattulainen I, Salmi M, Ivaska J, Pouwels J. Mutually exclusive roles of SHARPIN in integrin inactivation and NF-κB signaling. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0143423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rantala JK, Pouwels J, Pellinen T, Veltel S, Laasola P, Mattila E, Potter CS, Duffy T, Sundberg JP, Kallioniemi O, et al. SHARPIN is an endogenous inhibitor of β1-integrin activation. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:1315–1324. doi: 10.1038/ncb2340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gustafsson N, Zhao C, Gustafsson JA, Dahlman-Wright K. RBCK1 drives breast cancer cell proliferation by promoting transcription of estrogen receptor α and cyclin B1. Cancer Res. 2010;70:1265–1274. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Queisser MA, Dada LA, Deiss-Yehiely N, Angulo M, Zhou G, Kouri FM, Knab LM, Liu J, Stegh AH, DeCamp MM, et al. HOIL-1L functions as the PKCζ ubiquitin ligase to promote lung tumor growth. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:688–698. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201403-0463OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Greenfeld H, Takasaki K, Walsh MJ, Ersing I, Bernhardt K, Ma Y, Fu B, Ashbaugh CW, Cabo J, Mollo SB, et al. TRAF1 coordinates polyubiquitin signaling to enhance Epstein-Barr virus LMP1-mediated growth and survival pathway activation. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004890. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Walczak H, Iwai K, Dikic I. Generation and physiological roles of linear ubiquitin chains. BMC Biol. 2012;10:23. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-10-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vadász I, Weiss CH, Sznajder JI. Ubiquitination and proteolysis in acute lung injury. Chest. 2012;141:763–771. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jaakkola P, Mole DR, Tian YM, Wilson MI, Gielbert J, Gaskell SJ, von Kriegsheim A, Hebestreit HF, Mukherji M, Schofield CJ, et al. Targeting of HIF-α to the von Hippel-Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2-regulated prolyl hydroxylation. Science. 2001;292:468–472. doi: 10.1126/science.1059796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Queisser MA, Dada LA, Deiss-Yehiely N, Zhou G, Liu J, Chandel NS, Budinger S, Ciechanover A, Iwai K, Sznajder JI. The ubiquitin ligase HOIL-1L targets PKCζ and regulates cellular adaptation to hypoxia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:A5991. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ye S, Cihil K, Stolz DB, Pilewski JM, Stanton BA, Swiatecka-Urban A. c-Cbl facilitates endocytosis and lysosomal degradation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in human airway epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:27008–27018. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.139881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lazarou M, Sliter DA, Kane LA, Sarraf SA, Wang C, Burman JL, Sideris DP, Fogel AI, Youle RJ. The ubiquitin kinase PINK1 recruits autophagy receptors to induce mitophagy. Nature. 2015;524:309–314. doi: 10.1038/nature14893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fujita N, Morita E, Itoh T, Tanaka A, Nakaoka M, Osada Y, Umemoto T, Saitoh T, Nakatogawa H, Kobayashi S, et al. Recruitment of the autophagic machinery to endosomes during infection is mediated by ubiquitin. J Cell Biol. 2013;203:115–128. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201304188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lam HC, Cloonan SM, Bhashyam AR, Haspel JA, Singh A, Sathirapongsasuti JF, Cervo M, Yao H, Chung AL, Mizumura K, et al. Histone deacetylase 6-mediated selective autophagy regulates COPD-associated cilia dysfunction. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:5212–5230. doi: 10.1172/JCI69636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mizumura K, Choi AMK, Ryter SW. Emerging role of selective autophagy in human diseases. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:244. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ryter SW, Choi AMK. Autophagy in lung disease pathogenesis and therapeutics. Redox Biol. 2015;4:215–225. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2014.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mitra S, Sammani S, Wang T, Boone DL, Meyer NJ, Dudek SM, Moreno-Vinasco L, Garcia JG, Jacobson JR. Role of growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible α in Akt phosphorylation and ubiquitination after mechanical stress-induced vascular injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:1030–1040. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201103-0447OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stepaniants S, Wang IM, Boie Y, Mortimer J, Kennedy B, Elliott M, Hayashi S, Luo H, Wong J, Loy L, et al. Genes related to emphysema are enriched for ubiquitination pathways. BMC Pulm Med. 2014;14:187. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-14-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tomonaga M, Hashimoto N, Tokunaga F, Onishi M, Myoui A, Yoshikawa H, Iwai K. Activation of nuclear factor-κB by linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex contributes to lung metastasis of osteosarcoma cells. Int J Oncol. 2012;40:409–417. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Brazee P, Dada L, Sun H, Deiss-Yehiely N, Welch L, Morales-Nebreda L, Chi M, Staricha K, Cheng Y, Radigan K, Ridge KM, Budinger S, Sznajder JI. Role of LUBAC in modulation of lung epithelium inflammatory response to influenza virus. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:A6157–A6157. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kensche T, Tokunaga F, Ikeda F, Goto E, Iwai K, Dikic I. Analysis of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) essential modulator (NEMO) binding to linear and lysine-linked ubiquitin chains and its role in the activation of NF-κB. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:23626–23634. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.347195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sakamoto H, Egashira S, Saito N, Kirisako T, Miller S, Sasaki Y, Matsumoto T, Shimonishi M, Komatsu T, Terai T, et al. Gliotoxin suppresses NF-κB activation by selectively inhibiting linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex (LUBAC) ACS Chem Biol. 2015;10:675–681. doi: 10.1021/cb500653y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]