Abstract

Key points

Most missense long QT syndrome type 2 (LQTS2) mutations result in Kv11.1 channels that show reduced levels of membrane expression.

Pharmacological chaperones that rescue mutant channel expression could have therapeutic potential to reduce the risk of LQTS2‐associated arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death, but only if the mutant Kv11.1 channels function normally (i.e. like WT channels) after membrane expression is restored.

Fewer than half of mutant channels exhibit relatively normal function after rescue by low temperature. The remaining rescued missense mutant Kv11.1 channels have perturbed gating and/or ion selectivity characteristics.

Co‐expression of WT subunits with gating defective missense mutations ameliorates but does not eliminate the functional abnormalities observed for most mutant channels.

For patients with mutations that affect gating in addition to expression, it may be necessary to use a combination therapy to restore both normal function and normal expression of the channel protein.

Abstract

In the heart, Kv11.1 channels pass the rapid delayed rectifier current (I Kr) which plays critical roles in repolarization of the cardiac action potential and in the suppression of arrhythmias caused by premature stimuli. Over 500 inherited mutations in Kv11.1 are known to cause long QT syndrome type 2 (LQTS2), a cardiac electrical disorder associated with an increased risk of life threatening arrhythmias. Most missense mutations in Kv11.1 reduce the amount of channel protein expressed at the membrane and, as a consequence, there has been considerable interest in developing pharmacological agents to rescue the expression of these channels. However, pharmacological chaperones will only have clinical utility if the mutant Kv11.1 channels function normally after membrane expression is restored. The aim of this study was to characterize the gating phenotype for a subset of LQTS2 mutations to assess what proportion of mutations may be suitable for rescue. As an initial screen we used reduced temperature to rescue expression defects of mutant channels expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Over half (∼56%) of Kv11.1 mutants exhibited functional gating defects that either dramatically reduced the amount of current contributing to cardiac action potential repolarization and/or reduced the amount of protective current elicited in response to premature depolarizations. Our data demonstrate that if pharmacological rescue of protein expression defects is going to have clinical utility in the treatment of LQTS2 then it will be important to assess the gating phenotype of LQTS2 mutations before attempting rescue.

Key points

Most missense long QT syndrome type 2 (LQTS2) mutations result in Kv11.1 channels that show reduced levels of membrane expression.

Pharmacological chaperones that rescue mutant channel expression could have therapeutic potential to reduce the risk of LQTS2‐associated arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death, but only if the mutant Kv11.1 channels function normally (i.e. like WT channels) after membrane expression is restored.

Fewer than half of mutant channels exhibit relatively normal function after rescue by low temperature. The remaining rescued missense mutant Kv11.1 channels have perturbed gating and/or ion selectivity characteristics.

Co‐expression of WT subunits with gating defective missense mutations ameliorates but does not eliminate the functional abnormalities observed for most mutant channels.

For patients with mutations that affect gating in addition to expression, it may be necessary to use a combination therapy to restore both normal function and normal expression of the channel protein.

Abbreviations

- CFTR

cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- CG

core glycosylated

- FG

fully glycosylated

- HEK

human embryonic kidney

- IKr

rapid delayed rectifier current

- IKv11.1

Kv11.1 channel current

- Kv

voltage‐gated potassium channel

- LQTS2

long QT syndrome type 2

- V0.5

membrane potential at half‐maximal activation/inactivation

Introduction

Kv11.1 (also called human ether‐a‐go‐go related gene: hERG) potassium channels pass the rapid delayed rectifier current (I Kr) which plays a critical role in repolarization of the cardiac action potential (Sanguinetti & Jurkiewicz, 1990; Sanguinetti et al. 1995) and in the suppression of arrhythmias caused by premature stimuli (Smith et al. 1996; Lu et al. 2001). Inherited mutations in Kv11.1 that result in decreased I Kr underlie the congenital form of long QT syndrome type 2 (LQTS2), a primary electrical disorder characterized by delayed repolarization of the cardiac ventricular action potential which manifests as a prolongation of the QT interval on the body surface ECG (Curran et al. 1995; Splawski et al. 2000). LQTS2 increases susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmias triggered by ectopic beats and is associated with an increased risk of sudden cardiac death (Curran et al. 1995; Splawski et al. 2000; Moss et al. 2002; Shimizu et al. 2009; Vandenberg et al. 2012; Bezzina et al. 2015).

LQTS2 is a genetically heterogeneous disease with more than 500 different Kv11.1 mutations identified to date (Zhang et al. 2010). In contrast to many other inherited diseases such as cystic fibrosis, in which one deletion mutant (Phe508del) in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) chloride channel accounts for the vast majority of cases (Riordan et al. 1989; Sosnay et al. 2013), most LQTS2‐affected families possess a novel Kv11.1 mutation (Splawski et al. 2000). LQTS2‐associated mutations in Kv11.1 can cause loss of channel function via several mechanisms (Delisle et al. 2004). Nonsense mutations typically lead to nonsense‐mediated mRNA decay (Gong et al. 2007). Conversely, most missense mutations result in a decrease in the amount of Kv11.1 channel protein expressed at the membrane, as a consequence of protein misfolding which triggers endoplasmic reticulum degradation of the channel protein (Gong et al. 2005; Anderson et al. 2006, 2014; Ke et al. 2013). The extent to which misfolded Kv11.1 proteins result in decreased plasma membrane expression is, however, quite variable (Anderson et al. 2006, 2014; Ke et al. 2013). Missense mutant channels may reach the plasma membrane but then have abnormal gating and/or ion permeation resulting in reduced channel function (Zhao et al. 2009). It is also possible for mutations to have multiple modes of action, for example partially reduced expression as well as abnormal gating (Berecki et al. 2005; Balijepalli et al. 2012; Kanters et al. 2015).

There are many inherited disorders, particularly those caused by mutations in membrane proteins, which result in protein misfolding and hence reduced membrane expression (Gomes, 2012; Conn et al. 2014, 2015; Leidenheimer & Ryder, 2014; Solomon et al. 2015). It has been estimated that up to 40% of diseases are attributable to protein misfolding (Leidenheimer & Ryder, 2014). The best known and most studied example is cystic fibrosis, which is caused by mutations in the CFTR chloride channel (Riordan et al. 1989; Solomon et al. 2015). Strategies to develop pharmacological chaperones, also termed pharmacoperones (Conn et al. 2014), that can ameliorate the assembly defects and restore expression of membrane proteins associated with various clinical disorders have been vigorously pursued (Gomes, 2012; Janovick et al. 2013; Conn et al. 2014, 2015; Leidenheimer & Ryder, 2014; Solomon et al. 2015). Understandably, there has therefore been great interest in applying this approach to rescue misfolded Kv11.1 channels (Zhou et al. 1999; Anderson et al. 2006, 2014; Balijepalli et al. 2010; Mehta et al. 2014; Zhang et al. 2014).

There is one caveat to the use of pharmacological chaperones. For such drugs to be therapeutically useful in the treatment of LQTS2, mutant channel proteins will not only have to express at the cell membrane, but will also need to have wild‐type‐like function once there. Similar to other voltage‐gated potassium channel (Kv) family members, Kv11.1 channels can exist in three main conformations: closed, open or inactivated (Vandenberg et al. 2012). Uniquely, Kv11.1 channels exhibit relatively slow kinetics for the activation (closed‐to‐open) and deactivation (open‐to‐closed) transitions, while the inactivation (open‐to‐inactivated) and recovery from inactivation (inactivated‐to‐open) transitions occur much more rapidly and with an intrinsic voltage dependence that is not linked to channel opening (Smith et al. 1996; Spector et al. 1996; Vandenberg et al. 2012). Given the complex and unique gating kinetics of Kv11.1 channels, as well as the critical role these channels play in cardiac repolarization, it seems likely that even subtle alterations to gating kinetics may not be well tolerated.

In this study, we wish to test the hypothesis that only a subset of missense Kv11.1 mutant channels when rescued would have a normal gating phenotype and so would be suitable candidates for rescue with pharmacological chaperones. As an initial screen we rescued expression defects using the Xenopus laevis expression system, which requires use of low temperatures and has previously been shown to permit rescue of expression defective Kv11.1 channels (Sanguinetti et al. 1996; Vandenberg et al. 2012). For most Kv11.1 mutants, the I Kv11.1 measured during a step ramp protocol to mimic the cardiac action potential was not significantly different to that seen for WT Kv11.1 channels. However, the complex kinetics of I Kv11.1 also plays an important role in how channels respond to premature beats and in this scenario the majority of mutants showed significantly reduced function and therefore would provide less protection against ectopic beats than WT Kv11.1. Our data suggest that the majority of mutant channels will have reduced function even after rescue of the expression defect and so may not be suitable candidates for rescue using pharmacological chaperones alone.

Methods

Molecular biology

A full‐length WT Kv11.1a construct with a C‐terminal HA‐tag was cloned into pIRES2‐eGFP (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA) to enable transfection into human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells. Mutagenesis of Kv11.1 cDNA was performed using the Quikchange method (Agilent Technologies, Santa, Clara, CA, USA) and confirmed by DNA sequencing. For Xenopus oocyte studies, the full‐length Kv11.1a cDNA was sub‐cloned into the pBluescript expression vector. Linearization of the plasmid was performed using BamHI–HF (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) and cRNA was in vitro transcribed using the mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA).

SDS‐PAGE and Western blot assay

HA‐tagged WT or mutant Kv11.1 constructs were transfected into HEK293 cells using the Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Life Technologies, Mulgrave, VIC, Australia) with 200 ng of DNA. Cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM, Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies) and stored at 37°C with 5% CO2. Cells were harvested 48 h after transfection and solubilized in Tris‐buffered saline (TBS, in mm: Tris 50, NaCl 137, pH 7.5) supplemented with 1% NP‐40 and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Castle Hill, NSW, Australia) for 1 h on a rotating wheel at 4°C. Cell lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 16,000 g at 4°C for 30 min. Lysates were then mixed with SDS‐PAGE sample buffer containing 5% β‐mercaptoethanol, then loaded and run on a 7.5% SDS‐PAGE gel before transfer to nitrocellulose membrane (Bio‐Rad, Gladesville, NSW, Australia). For quantitative Western blot analysis, membranes were probed simultaneously with mouse monoclonal anti‐HA antibody (HA.11, Covance, Princeton, NJ, USA) and a rabbit or mouse anti‐α‐actinin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), followed by anti‐rabbit IRDye680 or anti‐mouse IRDye800 to enable quantification with the Li‐Cor Odyssey infrared imaging system (Li‐Cor Biotechnology, Lincoln, NE, USA).

Kv11.1 channel protein was represented by two bands on the Western blot: a fully glycosylated band (FG, ∼155 kDa) which predominantly represents channel protein at the cell membrane, and a core glycosylated band (CG, ∼135 kDa) which represents immature protein that is intracellular and thus non‐functional. To account for changes in expression levels from experiment to experiment, membrane expression was calculated from the ratio of the FG/CG bands (i.e. the CG band acts as an internal loading control). For each experiment, the mutant FG/CG ratio was compared to corresponding measures from a WT construct expressed on the same day (i.e. mutants were normalized to WT). As FG/CG values were always normalized to WT protein (including for WT itself), then WT was expressed as 1 in every experiment and so no error bars are shown for WT (WT data from n = 17 experiments). An FG/CG value of 0 indicates the absence of membrane protein on Western blots, 1 indicates an expression level comparable to WT (no defect) and > 1 indicates improved expression compared to WT. An ANOVA test, with Dunnet's post hoc comparison, was used to determine statistical significance compared to WT (P < 0.05). For a discussion regarding the limitations of using the FG/CG ratio as a measure of expression, please see the limitations section of the discussion.

Electrophysiology assay

Functional assays were performed on LQTS2 mutant Kv11.1 channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. This expression system was chosen because the low temperature (17°C) used to incubate oocytes after injection with cRNA allows for the rescue of expression of the vast majority of mutations (Sanguinetti et al. 1996; Vandenberg et al. 2012). Anderson et al. (2014) recently performed large scale expression studies of LQTS2 mutant channel proteins in HEK293 cells and showed that low temperature (27°C) incubation was able to ameliorate expression defects associated with 13/15 LQTS2 mutations examined in our study, although the extent of this rescue was not quantified. The ability to rescue expression through low temperature incubation is therefore probably common to both oocyte and HEK293 expression systems, although the extent of the rescue is probably greater in oocytes because the lower temperatures at which they remain viable after > 24 h of incubation (i.e. 17°C for oocytes vs. 27–37°C for HEK293 cells) facilitates the rescue of misfolded proteins. In this study we did not set out to determine the extent to which mutation‐induced expression defects could be rescued. Instead low temperature rescue of expression in oocytes is used only as a tool to determine whether mutations would remain pro‐arrhythmic (due to functional defects) if normal expression could be restored. All functional measures of I Kv11.1 were normalized to the slope conductance (which acts as a measure of expression) measured in the same cell, to exclude variations in channel expression and measure only the changes in current caused by functional gating defects caused by the mutation.

Female Xenopus laevis frogs were purchased from Nasco (Fort Atkinson, WI, USA). All experiments were approved by the Garvan/St Vincent's Animal Ethics Committee (Approval ID 14/30). Following anaesthetization in 0.17% (w/v) tricaine (Sigma, Castle Hill, NSW, Australia) the ovarian lobes were removed through a small abdominal incision. The follicular cell layer was removed by ∼2 h digestion with 1 mg ml–1 Collagenase A (Roche Diagnostics, Castle Hill, NSW, Australia) in Ca2+‐free ND96 solution containing (mm): NaCl 96, KCl 2, MgCl2 1.0 and Hepes 5 (pH adjusted to 7.5 with NaOH). After rinsing with ND96 (as above, plus 1.8 mm CaCl2), stage V and VI oocytes were isolated and stored at 17°C in tissue culture dishes containing ND96 supplemented with 2.5 mm pyruvic acid sodium salt and 10 μg ml–1 amikacin.

Xenopus laevis oocytes were injected with cRNA and incubated at 17°C for 12–48 h prior to electrophysiological recordings. For co‐expression studies, 23 ng of mutant cRNA and 23 ng of WT cRNA (pre‐mixed at a 1:1 ratio prior to co‐injection) were typically injected and currents were recorded 12–36 h after injection. For some mutations a higher concentration of cRNA (41 ng for both mutant and WT, maintained at 1:1 ratio) or longer incubation time (up to 48 h) was required to observe current. Two‐electrode voltage‐clamp experiments were performed at room temperature (20–22°C) using a Geneclamp 500B amplifier (Molecular Devices Corp., Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Glass microelectrodes were filled with 3 m KCl and had tip resistances of 0.3–1.0 MΩ. Oocytes were perfused with solution containing (in mm): NaCl 94, KCl 4, MgCl2 1.0, CaCl2 1.8 and Hepes 5 (pH adjusted to 7.5 with NaOH). Data acquisition and analysis was performed using pClamp software (Version 10.4, Molecular Devices), as well as Microsoft Excel software (Microsoft Corporation), Prism 6 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) and Matlab (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA). All data are shown as mean ± SEM unless otherwise stated.

Voltage protocols and analysis

Voltage protocols are illustrated in each figure. To examine the extent to which LQTS2 mutations perturb the amount of I Kr contributing to cardiac repolarization, we used a step‐ramp voltage clamp protocol designed to mimic a ventricular action potential (see Fig. 2 A). Cells were clamped at a membrane potential of −80 mV prior to a depolarizing pulse to +30 mV for 500 ms (to mimic the plateau phase) followed by a ramp repolarization back to −80 mV over 220 ms (to mimic the repolarizing phase). WT or mutant currents elicited during the ramp repolarization phase were corrected for capacitance artefacts by subtracting the instantaneous drop in current observed at the onset of the ramp repolarization phase from the repolarizing current. In addition, to compensate for the variable expression levels observed between cells, current amplitudes were normalized to the whole cell conductance measured in the same cell from the peak negative currents elicited at voltages between −140 and −160 mV following a +40 mV depolarization for 1 s (see Fig. 2 E, F). To examine the extent to which LQTS2 mutations perturb the amount of protective I Kr elicited in response to premature beats, we delivered premature depolarizations at 20 ms intervals during or after the ramp phase of the step‐ramp protocol. Premature stimuli were mimicked by depolarizing the membrane potential to 0 mV for 40 ms, starting 120 ms after the start of the repolarizing ramp and continuing at 20 ms intervals in 23 successive sweeps, finishing 560 ms after the start of the repolarizing ramp (see Fig. 2 C). Peak protective I Kv11.1 current at each time point was measured by fitting the I Kv11.1 at 0 mV with a single exponential function and extrapolating back to the start of the 0 mV voltage step to eliminate capacitance spike artefacts. As before, peak I Kv11.1 levels were normalized to the whole cell conductance to compensate for variable expression levels.

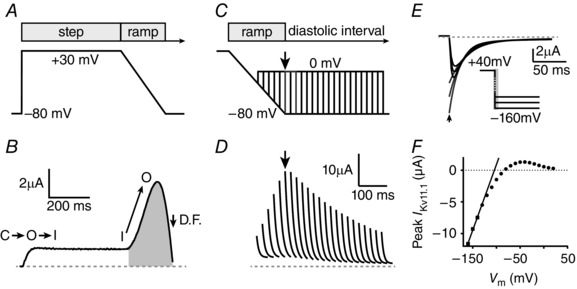

Figure 2. Functional analysis of WT Kv11.1 channels .

A, ventricular action potential ‘step‐ramp’ voltage protocol during which cells were held at a membrane potential of −80 mV prior to a depolarizing pulse to +30 mV for 500 ms, followed by a ramp repolarization back to −80 mV over 220 ms. B, typical WT‐I Kv11.1 in response to the voltage protocol shown in A. WT Kv11.1 channels activate slowly and inactivate rapidly (C→O→I), so minimal I Kv11.1 is observed during the +30 mV step pulse. Channels rapidly recover from inactivation (I→O) during the repolarization ramp allowing a large increase in I Kv11.1 which reaches peak amplitude about halfway through repolarization. The decline in I Kv11.1 during terminal repolarization is due to a decrease in driving force (D.F.) rather than channel deactivation, which occurs slowly during the diastolic interval. Repolarizing I Kv11.1 is defined as the area highlighted in grey. C, premature depolarizations (to 0 mV for 40 ms) were delivered during the step‐ramp protocol shown in A, starting 120 ms after the start of the ramp and continuing at 20 ms intervals in 23 successive sweeps, finishing 560 ms after the start of the repolarizing ramp. D, typical WT‐I Kv11.1 peaks measured at each premature depolarization time point by fitting the I Kv11.1 at 0 mV with a single exponential function and extrapolating back to the start of the voltage step. The envelope of peak current spikes for WT‐I Kv11.1 shows a typical biphasic profile, peaking 240 ms after the start of the repolarizing ramp. To compensate for the variable expression levels observed between cells, I Kv11.1 amplitudes were normalized to the whole cell conductance measured between −140 and −160 mV in the same cell. E, peak negative tail currents, measured at voltages between −140 and −160 mV following a 1 s depolarization to +40 mV (inset), were obtained by fitting exponential functions to the decaying portion of the current and extrapolating current back to the beginning of the voltage step (grey lines with peak denoted by arrow). F, whole cell conductance of a single cell measured from the linear slope of the peak currents, which provides an estimate of relative expression levels for normalization of I Kv11.1 from B and D.

To determine the mechanism(s) by which LQTS2 mutations alter the amount of repolarizing and/or protective I Kv11.1, we measured the kinetics and voltage dependence of channel activation (closed‐to‐open transition), deactivation (open‐to‐closed transition), inactivation (open‐to‐inactivated transition) and recovery from inactivation (inactivated‐to‐open transition), using protocols previously described (Vandenberg et al. 2012) and shown in the relevant figures.

Steady state inactivation of Kv11.1 channels can be measured in several different ways (Vandenberg et al. 2012). Most methods use two‐pulse protocols where deactivating currents are extrapolated back to the time of the voltage step. This works well for WT Kv11.1, but does not provide very accurate estimates for faster deactivating Kv11.1 mutant channels due to fitting errors. For this reason we chose to measure steady state inactivation from the rates of inactivation and recovery from inactivation (Wang et al. 2011). Rates for the onset of inactivation were measured using a triple pulse protocol shown in the left panel of Fig. 5 A(i). From a holding potential of −90 mV, cells were depolarized to +40 mV for 1 s to fully inactivate the channels (for some mutant channels a more depolarized potential of + 80 mV was required). A subsequent voltage step to −110 mV for 10 ms allowed channels to recover from inactivation into the open state, before the membrane potential was stepped in 10 mV increments to voltages between +60 and −60 mV to initiate inactivation. Rates of inactivation at each voltage were obtained by fitting a single exponential to the respective decaying current trace [left panel in Fig. 5 A(ii)]. Rates of recovery from inactivation were measured using a two‐step protocol, as shown in the right panel of Fig. 5 A(i). From a holding potential of −90 mV, cells were depolarized to +40 mV (or +80 mV) for 1 s to fully inactivate the channels, before channels were allowed to recover from inactivation by stepping to a range of potentials, from +20 to −160 mV in 10 mV increments, for 3 s. At each voltage a ‘hooked’ tail current was observed, where the initial rapid current increase represents the recovery from inactivation, whereas the much slower decay in current occurs due to channel deactivation [see right panel in Fig. 5 A(ii)]. Rates for recovery from inactivation were obtained from the time constant corresponding to the increasing portion of a double exponential function fitted to the hooked tail currents. When plotted against voltage (see Fig. 5 B), the forward (onset inactivation) and reverse (recovery from inactivation) rates give rise to a chevron plot. The linear portions of the two arms of the chevron plot were then extrapolated (see Fig. 5 B, dotted lines) and the intersect between the lines (i.e. the voltage at which the forward and reverse transition rates are equal) was taken as a measure of the half‐maximal voltage (V 0.5) for inactivation.

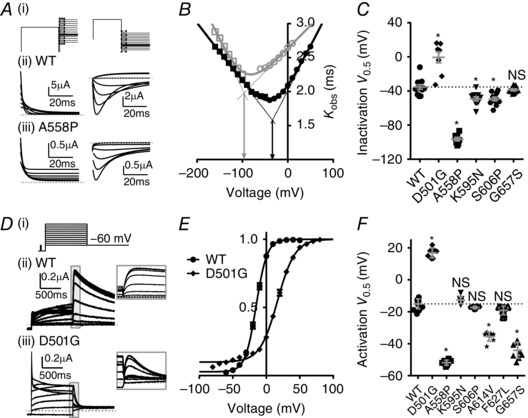

Figure 5. LQTS2 mutations alter Kv11.1 function by a variety of molecular mechanisms .

A, (i) Voltage protocols used to measure kinetics of onset of inactivation (left panels) and recovery from inactivation (right panels, see Methods for details). Typical I Kv11.1 for (ii) WT and (iii) mutant A558P channels recorded during voltage protocols shown in (i). Rates for onset of inactivation were obtained by fitting a single exponential function to the decaying current (fitted currents are shown) which represents channel transition from the open state to the inactivated state. Rates for recovery from inactivation were obtained from the time constant corresponding to the increase in current when a double exponential function was fitted to the hooked tail currents. B, rates for onset of inactivation (circles) and recovery from inactivation (squares) measured over a range of membrane potentials for WT (closed black symbols) and A558P (open grey symbols) channels. Linear portions of the two arms of the chevron plot were extrapolated (dotted lines) to find the voltage at which the two lines intersect (i.e. the voltage at which the forward and reverse transition rates are equal) which gives a measure of the half maximal voltage (V 0.5) for inactivation (indicated by arrows) for WT (black) and A558P mutant (grey) Kv11.1 channels. C, summary of the half maximal voltage (V 0.5) for inactivation for WT and five mutant channels. *P < 0.05 compared to WT using ANOVA test. Data points are from individual cells (between 8 and 12 cells depending on the mutation), with mean ± SEM bars shown in grey. Mean WT values are indicated with dotted line for comparison with mutants. D, typical I Kv11.1 traces from WT (ii) and mutant D501G (iii) Kv11.1 channels in response to a voltage protocol designed to measure the voltage dependence of channel activation (i) (see Methods for details). E, maximum peak tail currents (shown within inset in D) measured from WT (circles) and D501G (diamonds) channels were plotted against each voltage step. Peak tail currents were fitted with a Boltzmann equation to obtain the half‐maximum voltage (V 0.5) for activation. F, summary of the half maximal voltage (V 0.5) for activation of WT and seven mutant channels. *P < 0.05 compared to WT using ANOVA test. Data points are from individual cells (between 7 and 13 depending on the mutation), with mean ± SEM bars shown in grey. Mean WT values are indicated with dotted line for comparison with mutants.

The voltage dependence of steady‐state activation was measured using an isochronal tail current protocol [see Fig. 5 D(i)] (Vandenberg et al. 2012). From a holding potential of −90 mV, cells were depolarized for 1 s to voltages in the range of −60 to +50 mV (or to +80 mV for D501G), in 10 mV increments, before stepping to −60 mV to allow recovery from inactivation and to measure maximum peak tail currents from each preceding voltage step. Peak tail currents were fitted with a Boltzmann equation:

| (1) |

where V 0.5 is the half‐maximum activation voltage, V t is the test potential, k is the slope factor and g max is maximum conductance.

Rates of deactivation were measured using the same protocol as that used to measure the rate of recovery from inactivation (see Figs 5 A and 6 A). However, when cells were repolarized to voltages in the range −50 to −160 mV for 3 s, double exponential functions were fitted to the decaying portion of the current traces to obtain rates of deactivation at each voltage step. By extrapolating current back to the beginning of the voltage step, we also measured maximum negative peak tail currents at voltages between −140 and −160 mV and the linear slope of these values provided a measure of whole cell conductance, which in turn provided an estimate of relative expression levels for normalization of repolarizing I Kv11.1 and protective I Kv11.1 in response to premature stimuli.

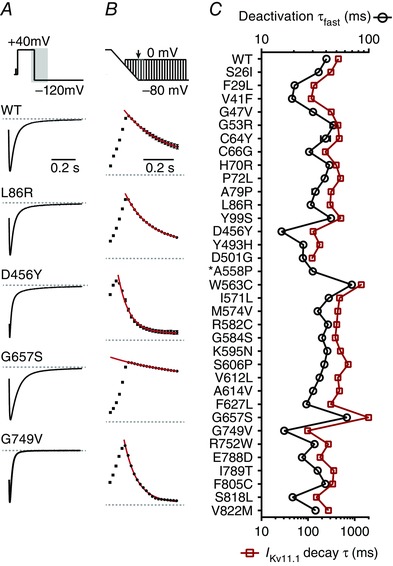

Figure 6. Faster deactivation kinetics cause reduced IKv11.1 in response to premature depolarizations for many LQTS2 mutant channels .

A, typical I Kv11.1 traces showing the rate of current decay for WT and four LQTS2 mutant Kv11.1 channels in response to a voltage protocol (shown in upper panel) designed to trigger channel deactivation. Tail currents were normalized to the peak negative current measured in the corresponding cell to aid comparison between mutants. Kinetics of deactivation were obtained by fitting a double exponential function to the decaying portion of the current. B, maximal peak I Kv11.1 elicited through WT and mutant channels in response to premature depolarizations elicited during the ramp repolarization phase and diastolic interval (see protocol in Fig. 2 C). All data are normalized to the peak outward current from the corresponding cell to aid comparison between mutants. Example raw currents for each mutant are shown in Fig. 4 A. Current decay was fitted with a single exponential function (red line) to obtain a single τ value. C, summary for WT and mutant Kv11.1 channels, which compares the time constant for the fast component of deactivation measured at −120 mV (open black circles, examples shown in A) with the time constant for I Kv11.1 decay (open red squares, examples shown in B) in response to premature depolarizations elicited during the diastolic interval. Data presented as mean ± SEM from 7 to 15 cells depending on the mutation. *It was not possible to accurately measure the decay in protective I Kv11.1 for mutant A558P due to the relatively small current amplitudes and minimal decay in protective I Kv11.1 (see Fig. 4 A for an example current profile).

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± SEM from n number of experiments, unless otherwise stated. Results for mutants and WT were compared using an ANOVA test with Dunnet's post hoc comparison (P < 0.05).

Results

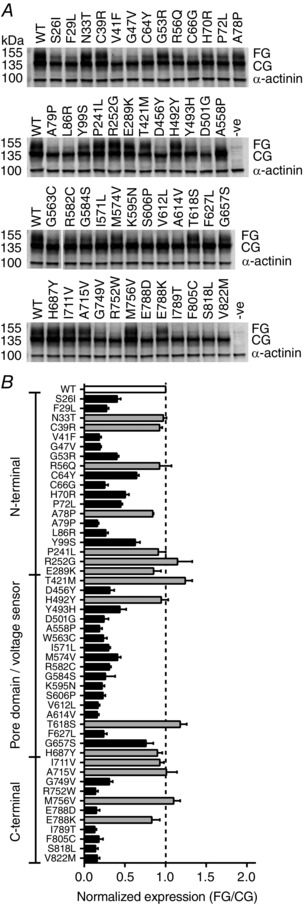

In this study we selected 49 missense LQTS2 mutations from the International long QT registry (Moss & Schwartz, 2005), ensuring reasonable distribution throughout the channel protein (i.e. representative numbers of mutations in the pore domain, N terminus and C terminus), but otherwise at random. To identify mutations that perturb the membrane expression of Kv11.1 channels, Western blot assays were performed to quantify the level of protein expression of these 49 LQTS2 mutant channels and WT (Fig. 1). Consistent with previous findings (Anderson et al. 2006, 2014; Ke et al. 2013, 2014) we observed two protein bands corresponding to Kv11.1 channels: a fully glycosylated (FG) band representing membrane protein and a core glycosylated (CG) band representing intracellular protein (Fig. 1 A). Protein expression was estimated from the ratio of the two bands (FG/CG), normalized to WT (Fig. 1 B). An FG/CG value of 0 indicates the absence of protein at the cell surface, 1 indicates an expression level comparable to WT (no defect) and > 1 indicates improved expression compared to WT. Of the 49 LQTS2 mutants tested, four exhibited expression levels that were increased by > 10% compared to WT (R252G, T421M, T618S and M756V), seven showed expression within ±10% of WT (N33T, C39R, R56Q, P241L, H492Y, I711V and A715V), while the remaining 38 showed a ≥10% decrease in expression level compared to WT. Of the 38 mutations with FG/CG ratios ≤90% of WT, four (A78P, E289K, H687Y, E788K) were identified as not significantly lower than WT (ANOVA, P > 0.05). Thus, from the original LQTS2 mutants we selected from the registry, about one‐third (15/49, ∼31%) had expression levels not significantly lower than WT, while the remaining 34 were expression defective mutations (Fig. 1 B).

Figure 1. Identification of expression defective LQTS2 mutations .

A, example Western blots showing protein levels for WT Kv11.1 and 49 different LQTS2 mutants. HEK293 cells were transfected with 200 ng of WT or mutant Kv11.1 DNA and harvested for Western blot after 48 h. Two protein bands corresponding to Kv11.1 channel protein were observed: a fully glycosylated (FG, ∼155 kDa) band representing channel protein expressed mostly at the cell membrane and a core glycosylated (CG, ∼135 kDa) band representing immature intracellular protein. α‐Actinin (∼100 kDa) was used as a loading control. B, membrane expression of 49 LQTS2 mutant proteins estimated from the ratio of FG/CG bands normalized to WT. An FG/CG value of 0 indicates the absence of protein at the cell surface, 1 indicates an expression level comparable to WT (no defect) and > 1 indicates improved expression compared to WT. Mutations with FG/CG values not significantly different from WT (white bar) are shown in grey (ANOVA, P > 0.05). Mutations that were considered expression defective (black bars) had FG/CG values significantly less than WT (ANOVA, P < 0.05, dashed line indicates WT level). The total number of experimental replicates (n) was between 4 and 14 for each mutant and 17 for WT.

To investigate whether LQTS2 mutations cause functional perturbations after the rescue of membrane expression, mutant Kv11.1 channels were expressed in Xenopus oocytes. This expression system was chosen because the low temperature (17°C) used to incubate oocytes after injection with cRNA allows for the rescue of expression of the vast majority of mutations (Sanguinetti et al. 1996; Vandenberg et al. 2012). The overall function of WT and mutant Kv11.1 channels was assessed using a step‐ramp protocol to mimic a ventricular action potential (Fig. 2 A, B) followed by a premature stimulation protocol to mimic early and delayed afterdepolarizations (Fig. 2 C, D). During the step‐ramp protocol, WT Kv11.1 channels pass little current (I Kv11.1) in response to the initial depolarization because they activate relatively slowly and then rapidly enter an inactivated state after opening (Fig. 2 B). During the ramp repolarization phase there is an increase in I Kv11.1 due to channels rapidly re‐entering the open state from the inactivated state (i.e. fast recovery from inactivation). The subsequent decline in I Kv11.1 near the end of the ramp is due to the decrease in electrochemical driving force (Smith et al. 1996; Lu et al. 2001). Importantly, at these voltages the rate of deactivation is very slow, so when premature stimuli are introduced during the repolarization ramp and subsequent diastolic interval, WT Kv11.1 channels pass an instantaneous spike in I Kv11.1 (Smith et al. 1996; Lu et al. 2001). Peak spike currents recorded in response to premature depolarizations given in 20 ms intervals show a biphasic pattern, where spike amplitude initially increases and then slowly decreases (Fig. 2 D). This biphasic time course reflects the rates of recovery from inactivation back into the open state followed by a much slower rate of deactivation.

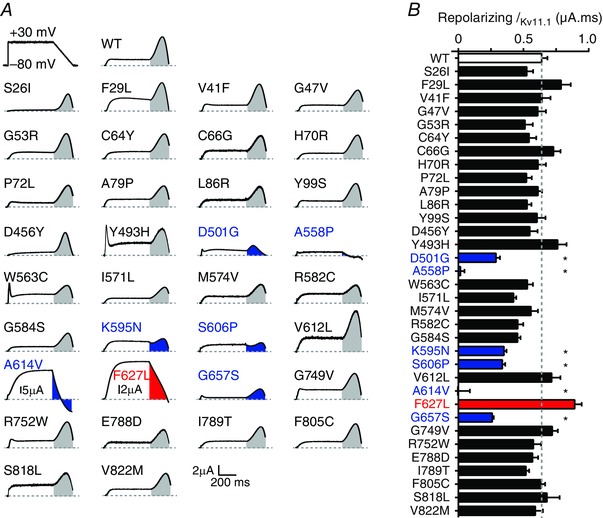

Given the complex interplay of the gating kinetics of Kv11.1 channels, if a mutation affects any of the gating transitions then it will affect the profile of I Kv11.1 flow during either the step ramp (Fig. 3) and/or the premature stimuli protocol (Fig. 4). These protocols therefore provide an efficient means of interrogating whether mutant channels have essentially normal or abnormal function. For the 34 mutants with rescued expression, most had I Kv11.1 profiles in response to the step ramp protocol that were broadly similar to that seen for WT (Fig. 3). Only seven mutant channels significantly perturbed the amount of repolarizing I Kv11.1 recording during the ramp phase: D501G, A558P, K595N, S606P, A614V, F627L and G657S (ANOVA, P < 0.05). All these mutations lie within the voltage sensor or pore domain of the Kv11.1 channel protein. With the exception of F627L, all passed significantly less repolarizing I Kv11.1 than WT (Fig. 3 B). Both A614V and F627L passed unusually large amounts of I Kv11.1 during the plateau phase of the action potential but this rapidly declined during the repolarization phase, so much so that for A614V a large negative current was observed at the terminal end of the repolarization ramp (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. IKv11.1 passed by LQTS2 mutant channels during the repolarization ramp of the step ramp protocol .

A, typical I Kv11.1 for WT and 34 LQTS2 mutants in response to the step‐ramp protocol, which is shown in upper left panel and in Fig. 2 A. Currents were corrected for capacitance artefacts and normalized to the whole cell conductance measured in the same cell (see Methods and Fig. 2). Scale bars are shown in bottom right but note that current scales are adjusted for mutants A614V and F627L. Shaded areas indicate I Kv11.1 passed during the repolarization ramp, where grey is similar to WT, blue is significantly less than WT and red is significantly greater than WT. B, summary showing charge during the repolarizing ramp phase. Colour coding as in A but with WT shown in white bar. *Significantly different from WT using ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc test (P < 0.05). Data presented as mean ± SEM from 7 to 15 cells depending on the mutation.

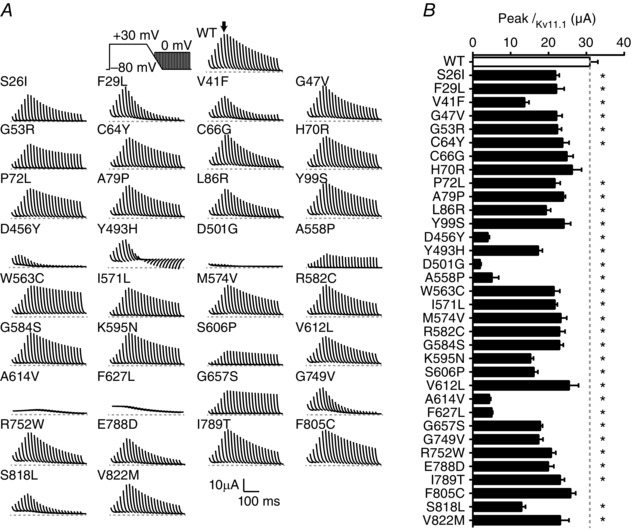

Figure 4. Many LQTS2 mutations reduce IKv11.1 amplitudes in response to premature depolarizations .

A, typical I Kv11.1 for WT and 34 LQTS2 mutants in response to premature depolarizations delivered in 20 ms intervals during and after the ramp repolarization. The voltage clamp protocol is shown in the upper left panel and in Fig. 2 C. Scale bars are shown in the bottom right. Currents were adjusted to compensate for expression levels by normalizing to the whole cell conductance measured in the same cell (see Fig. 2 E and F). B, summary data showing peak I Kv11.1 in response to a premature stimulus delivered at the end of the repolarizing ramp. *Significantly different from WT using ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc test (P < 0.05). Data presented as mean ± SEM from 7 to 15 cells depending on the mutation.

During premature stimuli protocols, the majority of mutant Kv11.1 channels generated I Kv11.1 spikes with the same biphasic distribution as observed for WT channels but many of these had reduced peak amplitudes (Fig. 4 B) and/or the magnitude of the spike amplitudes decayed more rapidly than seen for WT (Fig. 4 B and Fig. 6 B below). For example, mutation F29L exhibits similar peak I Kv11.1 to WT but the magnitude of the spike amplitudes decays much more rapidly. By contrast, V41F, D456Y, G749V and S818L exhibit both reduced peak I Kv11.1 amplitude as well as faster decay (Fig. 4 A). For other mutations, namely D501G, A558P, A614V and F627L, the amplitude of the I Kv11.1 spikes was very small across all time points (Fig. 4 A, B). In contrast to the relatively normal function of most mutant channels with regard to repolarizing I Kv11.1 during the ramp phase of the step‐ramp protocol, most mutants passed significantly less I Kv11.1 in response to premature stimuli (Fig. 4 B).

From the data in Figs 3 and 4 we can conclude that the majority of LQTS2 mutations affect Kv11.1 channel gating. To investigate which specific gating transitions were affected, we used a range of additional voltage protocols (see Methods and Fig. 5). Some of the mutations altered the voltage dependence of inactivation: for example, A558P caused a significant hyperpolarizing shift in the voltage dependence of C‐type inactivation [V 0.5 was: −96.4 ± 2.0 mV (n = 8) for A558P compared to −35.4 ± 2.7 mV (n = 12) for WT, P < 0.05 ANOVA, Fig. 5]. Smaller but significant hyperpolarizing shifts in the voltage dependence of inactivation were also observed for K595N (−49.3 ± 2.4 mV, n = 10) and S606P (−49.4 ± 2.2 mV, n = 11, Fig. 5) mutants. The enhanced inactivation caused by these mutations means that at physiological voltages more of the channels reside in an inactivated (non‐conducting) conformation, so they pass less I Kv11.1 during the ramp repolarization phase (Fig. 3) as well as less I Kv11.1 in response to premature stimuli (Fig. 4). Conversely, D501G showed reduced inactivation (Fig. 5 C). However, D501G also caused a depolarizing shift in the voltage dependence of activation [V 0.5 = +12.2 ± 3.2 mV (n = 7) for D501G compared to −15.1 ± 0.9 mV (n = 13) for WT, P < 0.05 ANOVA, Fig. 5 D–F] that was sufficient to reduce D501G‐I Kv11.1 during the ramp repolarization (Fig. 3) and almost eliminate D501G‐I Kv11.1 in response to premature stimuli (Fig. 4).

D501G mutant channels also showed much faster rates of channel deactivation (see Figs 5 D and 6), which was a feature seen in many LQTS2 mutant channels (Fig. 6). The rate of channel deactivation (measured at −120 mV) correlated well with the rate of decay of I Kv11.1 spike amplitude in response to premature stimuli elicited during the diastolic interval (Fig. 6), and largely explains why many LQTS2 mutants display reduced protective I Kv11.1 amplitudes in response to premature stimuli. Finally, two mutations, A614V and F627L, significantly altered the reversal potential [E rev = −14.8 ± 3.9 mV for A614V (n = 10) and −68.9 ± 0.6 mV for F627L (n = 7), compared to −82.7 ± 0.4 mV for WT (n = 13) Kv11.1] indicative of a loss of ion selectivity.

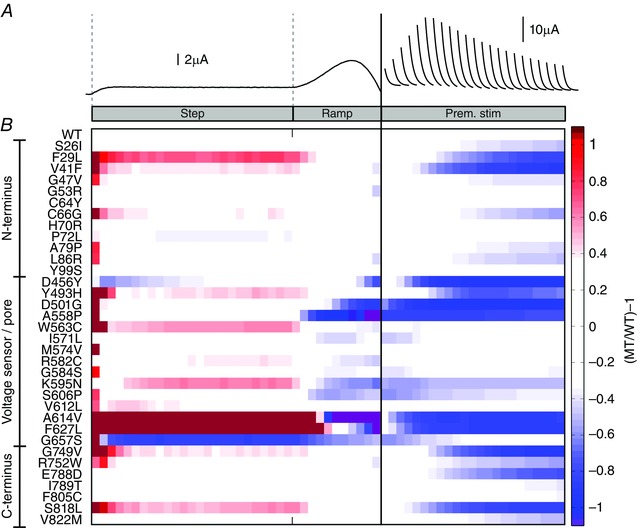

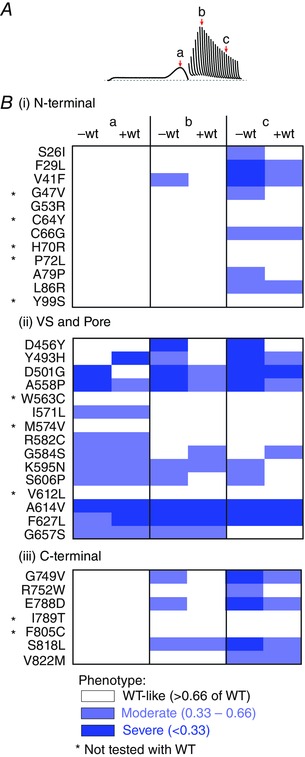

Our data demonstrate that different LQTS2‐causing mutations can differentially perturb all aspects of Kv11.1 gating to alter the finely balanced state occupation of the channel, resulting in complex and diverse alterations to I Kv11.1 profiles at different time points during the action potential and in response to early and delayed afterdepolarizations. This is summarized by the colour map shown in Fig. 7, where we compare the amount of I Kv11.1 passed by WT and mutant channels at 20 ms intervals during the plateau and repolarizing ramp phases of the step‐ramp protocol, as well as in response to premature stimuli. In this colour map white represents WT‐like levels of I Kv11.1, darker red represents progressively increased I Kv11.1 compared to WT, darker blue represents progressively less I Kv11.1 compared to WT and purple denotes inward I Kv11.1. Of the 34 LQTS2 mutations tested, ten were broadly similar to WT (defined as < 33% decrease compared to WT) with respect to both the peak I Kv11.1 available to repolarize the ventricular action potential and the amount of protective I Kv11.1 available to oppose premature stimuli. Ten mutations caused either moderate (defined as 33–66% decrease compared to WT: I571L, R582C, G584S, K595N, S606P, F627L, G657S) or severe (defined as > 66% decrease compared to WT: D501G, A558P, A614V) reductions in the peak repolarizing I Kv11.1 passed in response to a ventricular action potential. Of the mutants that effect peak repolarizing I Kv11.1, all but three (I571L, R582C and G584S) also reduced the amount of protective I Kv11.1 available to oppose premature stimuli. A few mutations, particularly A614V and F627L, greatly increased I Kv11.1 during the plateau phase of the ventricular action potential, largely due to reduced C‐type inactivation. Finally, 14/34 mutations showed only a reduction in the amount of protective I Kv11.1 available to oppose premature stimuli, although these effects ranged from moderate (33–66% decrease compared to WT; e.g. S26I, C66G) to severe (>66% decrease compared to WT; e.g. D456Y, G749V, S818L).

Figure 7. LQTS2 mutations alter the distribution of IKv11.1 during a step‐ramp protocol and in response to premature stimuli .

A, representative WT‐I Kv11.1 in response to a ‘step‐ramp’ protocol and in response to premature stimuli (separated by the solid vertical line). B, colour map comparing the amplitude of I Kv11.1 passed by WT and 34 LQTS2 mutant channels (MT/WT) at 20 ms intervals during the plateau and repolarizing ramp phases of the step‐ramp protocol, as well as in response to premature stimuli. White represents WT‐like levels of I Kv11.1, while darker red represents progressively increased I Kv11.1 compared to WT, darker blue represents progressively less I Kv11.1 compared to WT, and purple denotes inward I Kv11.1.

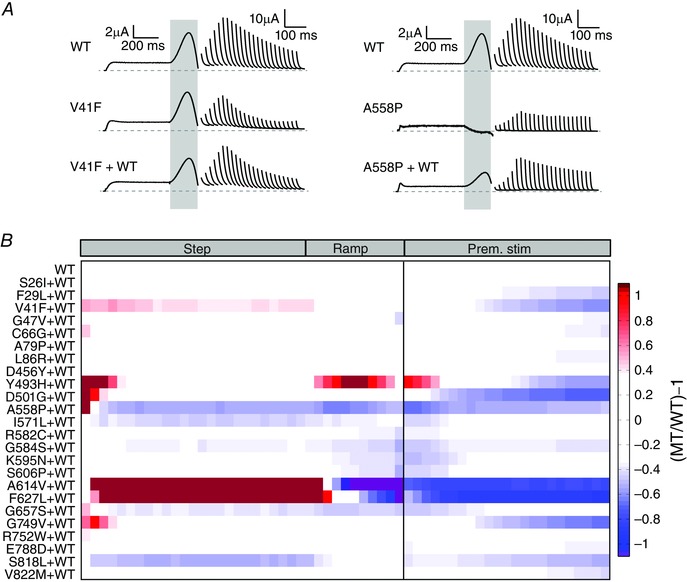

So far we examined the functional phenotype of LQTS2 mutations expressed alone. However, LQTS2 is an autosomal dominant disorder and almost all LQTS2 patients will possess both WT and mutant gene transcripts, so the resulting tetrameric Kv11.1 channels will be a heterologous mixture of WT and mutant subunits (Splawski et al. 2000). To examine whether this would alter the functional phenotype sufficiently to make rescue worthwhile, we examined the effect of WT co‐expression on each of 24 LQTS2 mutations that showed severe (defined as > 66% reduction compared to WT) or moderate (defined as 33–66% reduction compared to WT) perturbations to either repolarizing I Kv11.1, or I Kv11.1 elicited in response to premature stimuli, when expressed alone (Fig. 8). In most cases, co‐expression of mutant and WT subunits conferred a milder but broadly similar phenotype to that of the mutant alone. For example, compared to mutant alone the co‐expression of V41F with WT increased the amplitude and slowed the decay of I Kv11.1 spikes caused by premature stimuli, although not to WT levels (left panels in Fig. 8 A). Similarly, co‐expression of A558P with WT enhanced the amount of repolarizing I Kv11.1, as well as I Kv11.1 spikes produced in response to premature stimuli, but again these measures were still reduced compared to WT alone (right panels in Fig. 8 A). Overall, after co‐expression with WT at a 1:1 ratio, 19/24 mutants remained perturbing, while for five mutants (S26I, G47V, A79P, D456Y and R752W) WT‐like function was restored. In four of these five mutations, expression of mutant alone caused only moderate perturbations to I Kv11.1 elicited in response to premature stimuli, so even a relatively small reduction in the perturbation was sufficient to restore normal function when co‐expressed with WT subunits. In contrast, mutation D456Y caused a severe perturbation to I Kv11.1 elicited in response to premature stimuli when expressed alone, but this effect was completely abolished when co‐expressed with WT, suggesting either the resulting Kv11.1 channels mostly comprised WT subunits, or that perturbations caused by D456Y subunits are reduced when WT subunits are present. A summary colour map of the co‐expression data is shown in Fig. 8 B.

Figure 8. Co‐expression with WT subunits ameliorates but does not eliminate the perturbations caused by most LQTS2 mutations .

A, typical I Kv11.1 profiles in response to a step‐ramp protocol and in response to premature stimuli, for V41F and A558P mutant channels expressed alone (middle) or co‐expressed with WT (bottom), compared to WT alone (top). B, colour map showing the amplitude of I Kv11.1 passed by LQTS2 mutant channels co‐expressed with WT subunits (MT/WT). I Kv11.1 was measured at 20 ms intervals during the plateau and repolarizing ramp phases of the step‐ramp protocol, as well as in response to premature stimuli. White represents WT‐like levels of I Kv11.1, while darker red represents progressively increased I Kv11.1 compared to WT, darker blue represents progressively less I Kv11.1 compared to WT, and purple denotes inward I Kv11.1.

Overall, our data show that over half (19/34, ∼56%) of expression defective mutations cause either reduced repolarizing current or reduced protective current elicited in response to premature stimuli, even when co‐expressed with WT subunits (see Fig. 9) and these mutations would potentially still be pro‐arrhythmic following the rescue of expression defects.

Figure 9. Summary of perturbations in function caused by LQTS2 mutations .

A, I Kv11.1 amplitude was measured from the peak I Kv11.1 during the repolarizing ramp (a), as well as the peak protective I Kv11.1 in response to premature stimuli delivered 240 ms (b) or 440 ms (c) after the end of the plateau phase of the action potential mimic. B, colour coded summary of I Kv11.1 amplitudes for LQTS2 mutations, located within the N‐terminal (i), voltage sensor (VS)/pore (ii) or C‐terminal (iii) domains of the Kv11.1 channel protein, expressed alone (‐wt) or co‐expressed with WT subunits (+wt). White denotes WT‐like/mildly defective (I Kv11.1 > 66% of WT), light blue denotes moderate perturbations (I Kv11.1 between 66 and 33% of WT) and dark blue indicates severe loss of function (<33% of WT).

Discussion

Over 500 LQTS2‐associated mutations have been reported (Zhang et al. 2010), many of which result in loss of Kv11.1 channel protein expression at the membrane of cardiac myocytes (Gong et al. 2005; Anderson et al. 2006, 2014; Ke et al. 2013). Pharmacological chaperones that rescue mutant channel expression could have therapeutic potential to reduce the risk of LQTS2‐associated arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death, but only if the mutant Kv11.1 channels function normally (i.e. like WT channels) after membrane expression is restored. While the functional phenotype has been described for some expression defective mutant channels (Sanguinetti et al. 1996; Berecki et al. 2005; Zhao et al. 2009; Ke et al. 2013, 2014; Kanters et al. 2015), most have not been characterized. In this study we performed a large‐scale electrophysiological screen of LQTS2‐associated mutations to determine their functional phenotype following rescue of protein expression defects by low temperature. Our study shows that when expressed alone, 10/34 (∼29%) LQTS2 mutations functioned close to normal (defined as < 33% decrease compared to WT) in respect to both the amount of I Kv11.1 available to repolarize the ventricular action potential and the amount of protective I Kv11.1 available to oppose premature stimuli (see summary Fig. 9). In principal, pharmacological rescue of the expression defect for these ten LQTS2 mutations should restore a normal cardiac electrical phenotype, thereby reducing the risk of ventricular arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death. In contrast, when expressed alone, 10/34 (∼29%) LQTS2 mutations reduced the peak repolarizing current (defined as > 33% reduction vs. WT), either alone (I571L, R582C, G584S) or together with a decrease in the amount of protective I Kv11.1 elicited in response to premature stimuli (D501G, A558P, K595N, S606P, A614V, F627L, G657S). Furthermore, 14/34 (∼41%) mutations reduced only the protective current elicited in response to premature stimuli (Fig. 9). Of the 24 mutations that showed perturbed function when expressed alone, 19 (∼79%) remained perturbing even after co‐expression with WT subunits (Fig. 9). Many of the functionally perturbing mutations, especially those that significantly reduce the amount of repolarizing current, would clearly still be pro‐arrhythmic following rescue of their expression defects using pharmacological chaperones. Our study highlights the important need for electrophysiological screening of LQTS2 mutations before attempting pharmacological rescue of protein expression defects.

Kv11.1 channels are tetrameric proteins, with each of the four subunits comprising a voltage sensor (transmembrane segments S1–S4) and a pore domain (transmembrane segments S5 and S6) within the lipid membrane, flanked by large intracellular N‐ and C‐termini (Vandenberg et al. 2012). LQTS2 mutations are found throughout the length of the protein, although ‘hotspots’ of mutations seem to occur within the Per‐Arnt‐Sim (PAS) domain of the N‐terminus and in the pore domain (Vandenberg et al. 2012). Of the ten LQTS2 mutations that reduced the amount of repolarizing I Kv11.1 by 33% or more in our study, nine are located within the pore domain, one within the voltage sensor of the channel protein, but none is located within either the intracellular N‐ or C‐termini of the channel (see Figs 3 and 7). It has been shown that LQTS2 mutations within the pore domain of Kv11.1 channels are associated with more severe LQTS2 phenotypes – defined by a greater risk of cardiac events – than mutations within the voltage sensor, or intracellular N‐ or C‐termini (Moss et al. 2002; Shimizu et al. 2009). Although these more severe clinical phenotypes could reflect greater loss of membrane expression for the Kv11.1 pore mutants (Anderson et al. 2014), it seems likely that the more severe functional perturbations that we observed could also play an important role. Certainly, it is known that residues within the pore domain play direct roles in multiple facets of Kv11.1 channel gating (Wynia‐Smith et al. 2008; Ju et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2011; Ng et al. 2012; Perry et al. 2013). Consistent with this, our data showed that pore domain mutations can perturb almost any aspect of channel gating, either alone or in combination, to alter the distribution of current passed during an action potential. For example, perturbations to activation (i.e. D501G, A558P, A614V, G657S), deactivation (i.e. D501G), and C‐type inactivation or recovery from inactivation (i.e. A558P, K595N, S606P, A614V, F627L), as well as the selective permeation of K+ ions (A614V, F627L) were all observed. These perturbations severely reduced the amount of I Kv11.1, which impairs repolarization.

In addition to reducing the amount of repolarizing I Kv11.1, pore mutants A558P, K595N, S606P, A614V, F627L and G657S, as well as the voltage sensor mutation D501G, also perturbed the amount of protective I Kv11.1 generated in response to premature stimuli (see Figs 4 and 7). At least for D501G, A558P, A614V and F627L, as well as voltage sensor mutation D456Y (which did not affect repolarizing I Kv11.1), these effects were severe (>66% reduction) and observed across all premature stimuli time points both during repolarization and during the diastolic interval. The instantaneous I Kr spikes passed by Kv11.1 channels in response to premature stimuli during repolarization or early during the diastolic interval are thought to be important contributors of refractoriness of the cardiac tissue by opposing depolarization of the membrane potential and thereby suppressing the activation of Na+ channels and protecting against the formation of ectopic beats (Smith et al. 1996; Lu et al. 2001). That the pore mutants severely reduce the amplitude of protective I Kv11.1 spikes during this early period would probably increase the risk of early afterdepolarizations, which can trigger ectopic beats, ventricular arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death.

In contrast to the wide range of gating perturbations caused by mutations within the pore domain of Kv11.1 channels, mutations within the N‐ and C‐termini of the channel almost exclusively perturbed the kinetics of channel deactivation (Fig. 6). Recently, we (Ng et al. 2014) and others (Gustina & Trudeau, 2011; Muskett et al. 2011; Gianulis et al. 2013) showed that the large intracellular N‐ and C‐termini interact to control the kinetics of channel closure. In this study, we found a strong correlation between the kinetics of deactivation and the decay of the protective I Kv11.1 spikes elicited in response to premature stimuli during the diastolic interval (Fig. 6). This is not surprising as we know that the magnitude of the transient I Kv11.1 spike is proportional to the number of open channels at the time of the premature stimulus (Smith et al. 1996; Lu et al. 2001). Faster rates of channel closure will lower the percentage of channels existing in the open state early during the diastolic interval and thus reduce the protective I Kv11.1 spike amplitude. For mutants with the fastest rates of channel closure, such as V41F in the N‐terminus and S818L in the C‐terminus, spike amplitudes are reduced at all premature stimuli time points during the diastolic interval (Fig. 7). Just as with the pore mutations, this reduction in protective I Kv11.1 will reduce the refractoriness of the cardiac tissue and increase the risk of early after‐depolarizations generating ectopic beats and triggering episodes of ventricular arrhythmia (Smith et al. 1996; Lu et al. 2001). For mutations with moderately faster rates of channel deactivation (i.e. L86R and R752W) the protective I Kv11.1 spikes are only reduced when premature stimuli are given later during the diastolic interval (Fig. 7). Given the dominant role of I K1 (passed by Kir2 channels) during the diastolic period in ventricular myocytes (Nerbonne & Kass, 2005) it is possible that a modest reduction in protective I Kr spikes later during the diastolic interval may not have a significant impact. However, further studies are required to determine whether these moderately perturbing deactivation mutations will be pro‐arrhythmic.

For most mutants that had abnormal gating, co‐expression with WT subunits resulted in an amelioration of the abnormal function (Fig. 8), although function was restored to near normal levels in only 5/24 mutants. Whilst we expressed the mutant and WT subunits as separate plasmids, and so cannot be certain that there were equal levels of mutant and WT subunits, our results are broadly consistent with data obtained when using concatenated constructs containing mutant and WT subunits (Thomson et al. 2014; Wu et al. 2014). For the more perturbing mutants, e.g. A614V and F627L, the gating phenotype is still markedly abnormal (see Figs 8 and 9) and so still not suitable for rescue. However, for five mutants (S26I, G47V, A79P, D456Y and R752W) a normal phenotype was restored when co‐expressed with WT subunits, making these mutants suitable for rescue. Of these, all except D456Y showed moderate perturbations to I Kv11.1 elicited in response to premature stimuli when expressed alone, while the severe perturbations observed with D456Y alone were completely abolished when co‐expressed with WT subunits. In summary, our data show that when co‐expressed with WT Kv11.1, over half (19/34, ∼56%) of expression defective mutations would potentially still be pro‐arrhythmic following the rescue of expression defects.

So far, the successful rescue of expression defective Kv11.1 mutations has been achieved in vitro using reduced temperature or chemical/pharmacological chaperones (Zhou et al. 1999; Anderson et al. 2014), but none of these is currently suitable for in vivo use (for comprehensive reviews on current and potential rescue strategies see Balijepalli et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2014). To date, most of the identified pharmacological chaperones also show antagonist activity on Kv11.1 channels, so direct clinical application will require an improved pharmacological profile that allows rescue of expression defects without block of K+ permeation through the channel. In this respect, Kv11.1 channel activators might be potential alternatives (Balijepalli et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2014), although none has so far been shown to effectively restore expression defects associated with LQTS2 mutations. Proteasomal inhibitors can also rescue expression of mutant Kv11.1 channels (Kagan et al. 2000; Mehta et al. 2014) but non‐selective side effects would limit the utility of such an approach clinically. Better high‐throughput cell‐based pharmacological chaperone screening assays, similar to those successfully employed for gonadotropin releasing hormone receptor (Janovick et al. 2013; Conn et al. 2014, 2015) or CFTR chloride channels (Solomon et al. 2015), should facilitate the development of pharmacological chaperones that can selectively rescue Kv11.1 mutant channels and which can be tested as therapeutic agents for LQTS2 in clinical trials.

LQTS2 mutations have been subdivided into four categories according to the primary mechanistic defect: (1) abnormal biogenesis, (2) deficient protein expression, (3) perturbed gating or (4) altered selectivity for potassium ions (Delisle et al. 2004). However, any given LQTS2 mutation may not be limited to one mechanistic category. In cystic fibrosis, the most common CFTR chloride channel mutation – Phe508del – is associated with both an expression defect and a gating defect (Riordan et al. 1989; Sosnay et al. 2013), so clinical trials are now testing the therapeutic benefits of pharmacological chaperones (correctors) in combination with gating modifiers (potentiators) (Solomon et al. 2015) to correct both defects. Our study demonstrates that many LQTS2 mutations not only cause expression defects but also have diverse functional gating defects. Therefore, to restore normal function we may need to employ a similar mutation‐specific combined therapeutic approach to rescue both expression and function of Kv11.1 channels. In the last decade several Kv11.1 channel activators have been identified, and the mechanism(s) by which they enhance Kv11.1 function are varied (Kang et al. 2005; Zeng et al. 2006; Gerlach et al. 2010; Perry et al. 2010; Vandenberg et al. 2012). Type 2 activators such as ICA‐105574 predominantly enhance Kv11.1 function via impaired inactivation, caused by a depolarizing shift in the voltage dependence of inactivation (Gerlach et al. 2010), but it is not yet clear to what degree this type of activator could restore normal function to inactivation enhanced mutations such as A558P. Alternatively, the type 1 activator RPR260243 (Kang et al. 2005) and the naturally occurring mallotoxin (Zeng et al. 2006) predominantly slow Kv11.1 channel deactivation, so may be employed to restore normal function in fast deactivating LQTS2 mutations such as R56Q.

Limitations

To identify expression defective LQTS2 mutations we compared the FG/CG ratio for each mutant to WT. This measure does not account for the possibility that mutants can reduce biogenesis (i.e. reduced CG and FG bands) while retaining a relatively normal FG/CG ratio. An alternative measure of FG/α‐actinin (or FG/α‐actin), relative to WT, was made for all 49 mutants (data not shown). In most cases, the FG/CG ratio broadly correlated with the FG/α‐actinin ratio. However, four mutations showed FG/CG ratios not significantly lower than WT (R56Q, A78P, T421M, E788K) but with reduced (<0.9) FG/α‐actinin, and these were all excluded from the functional analysis. Just two mutations (G584S, G657S) showed reduced FG/CG but not reduced FG/α‐actinin. As FG/α‐actinin does not account for variations in transfection efficiency, because α‐actinin is a protein native to HEK293 cells (FG/CG does to some extent account for transfection efficiency), which is probably a large source of error in our experiments, we elected to use the FG/CG ratio, rather than FG/α‐actinin, as our measure of expression. At most this would lead to the inclusion of two mutations (G584S and G657S) in the functional analysis that would otherwise be removed if using the FG/α‐actinin data.

In this study we used a Xenopus laevis oocyte expression system to examine the functional phenotype of LQTS2 mutations after rescue of protein expression defects with low temperature. This system was ideal for our purposes, i.e. to rescue expression defects seen in mutant channels, but the recordings were undertaken at room temperature rather than at 37°C. Low temperature recording is known to slow gating kinetics, although it is likely that the relative differences between WT and mutants will be similar, as has been shown previously for some mutants (see e.g. F29L: Gianulis & Trudeau, 2011; Ke et al. 2013; Kanters et al. 2015). A second consideration is that Xenopus oocytes may not contain the same complement of accessory proteins as seen in cardiac myocytes, which may be important for some mutants. Also, effects related to phosphorylation, or regulation by other signalling pathways, have not been taken into account in our study. These limitations, however, are likely to lead us to have underestimated the number of mutations with functional defects, i.e. it may be > 56%.

Another potential limitation is that we have used low temperature as a non‐selective rescue strategy. It is quite possible that the extent of rescue achievable with pharmacological chaperones may be different from that for low temperature.

In this study we used an arbitrary cut‐off of a 33% decrease in I Kv11.1 to determine whether a mutation is likely to result in altered function in myocytes (see Fig. 9). Studies of nonsense LQTS2 mutations show that an approximate 50% reduction in I Kr results in a QTc prolongation in patients of between 10 and 15%, that is from a mean QTc of ∼420 ms in controls to between ∼460 and 480 ms in LQTS2 patients (Gong et al. 2007; Zarraga et al. 2011), which are approximately the median values for populations of control and LQTS patients (Viskin, 2009). Given these studies, our segregation of mild (>66% of WT), moderate (33–66% of WT) and severe (<33% of WT) phenotypes appears reasonable, although it is possible that this level may be too stringent if one takes into account that the phenotypes are likely to be ameliorated by co‐expression with WT subunits. In future studies it would be worth investigating, in more physiological systems, what level of deficit could be tolerated, for example by using in silico whole heart models (Zemzemi et al. 2013; Sadrieh et al. 2014), human‐induced pluripotent stem cell models (Bellin et al. 2013; Matsa et al. 2014; Liu & Trudeau, 2015) or animal models such as the zebrafish models developed by Jou et al. (2013).

Summary and translational perspectives

LQTS2 is a genetically heterogeneous disorder with most LQTS2 mutations occurring in just one or a few families. LQTS2 mutations can perturb Kv11.1 channel function through a variety of mechanisms, including reduced protein translation, reduced membrane expression and/or altered channel function. The vast majority of missense mutations, however, are known to reduce membrane expression of the Kv11.1 channel protein. Thus it is possible that pharmacological chaperones that correct expression defects could offer a therapeutic strategy to reduce the risk of arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death in a large proportion of patients. In this study we performed a large‐scale electrophysiological screen to assess the functional phenotype of LQTS2‐associated mutations following rescue of protein expression defects. Our data show that nearly half of the mutants function normally following rescue. Patients with these mutations could potentially benefit from therapy based on pharmacological chaperones. However, just over half of rescued LQTS2 mutations cause complex and diverse alterations to function that could potentially be pro‐arrhythmic. For patients with those mutations, if we have mutation‐specific information about the functional gating defect we may be able to use a combination therapy to restore both normal function and normal expression of the channel protein in a mutation‐specific manner. Similar strategies are in clinical trials for patients with CFTR chloride channel mutations that cause cystic fibrosis (Solomon et al. 2015) and offer an exemplar for the drive toward a precision medicine approach to diagnose and treat individual disease phenotypes (Collins & Varmus, 2015).

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

M.D.P. conceived and designed the experiments, collected and analysed data and drafted the manuscript. C.A.N., K.P., E.D. and K.S. collected and analysed electrophysiology data. C.A.N., M.J.H and Y.K. collected, analysed and interpreted the W.B. data. S.A.M., M.I. and A.P.H. designed analysis routines and assisted with data interpretation. J.I.V. assisted with design of experiments, data interpretation and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and qualify for authorship.

Funding

This research was supported by a Froulop grant awarded to M.D.P. by St Vincent's Research Foundation, as well as a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Program Grant (NHMRC 1074386) and an NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship (NHMRC 1019693) awarded to J.I.V.

References

- Anderson CL, Delisle BP, Anson BD, Kilby JA, Will ML, Tester DJ, Gong Q, Zhou Z, Ackerman MJ & January CT (2006). Most LQT2 mutations reduce Kv11.1 (hERG) current by a class 2 (trafficking‐deficient) mechanism. Circulation 113, 365–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CL, Kuzmicki CE, Childs RR, Hintz CJ, Delisle BP & January CT (2014). Large‐scale mutational analysis of Kv11.1 reveals molecular insights into type 2 long QT syndrome. Nat Commun 5, 5535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balijepalli SY, Anderson CL, Lin EC & January CT (2010). Rescue of mutated cardiac ion channels in inherited arrhythmia syndromes. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 56, 113–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balijepalli SY, Lim E, Concannon SP, Chew CL, Holzem KE, Tester DJ, Ackerman MJ, Delisle BP, Balijepalli RC & January CT (2012). Mechanism of loss of Kv11.1 K+ current in mutant T421M‐Kv11.1‐expressing rat ventricular myocytes: interaction of trafficking and gating. Circulation 126, 2809–2818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellin M, Casini S, Davis RP, D'Aniello C, Haas J, Ward‐van Oostwaard D, Tertoolen LG, Jung CB, Elliott DA, Welling A, Laugwitz KL, Moretti A & Mummery CL (2013). Isogenic human pluripotent stem cell pairs reveal the role of a KCNH2 mutation in long‐QT syndrome. EMBO J 32, 3161–3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berecki G, Zegers JG, Verkerk AO, Bhuiyan ZA, de Jonge B, Veldkamp MW, Wilders R & van Ginneken AC (2005). HERG channel (dys)function revealed by dynamic action potential clamp technique. Biophys J 88, 566–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezzina CR, Lahrouchi N & Priori SG (2015). Genetics of sudden cardiac death. Circ Res 116, 1919–1936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins FS & Varmus H (2015). A new initiative on precision medicine. N Engl J Med 372, 793–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn PM, Smithson DC, Hodder PS, Stewart MD, Behringer RR, Smith E, Ulloa‐Aguirre A & Janovick JA (2014). Transitioning pharmacoperones to therapeutic use: in vivo proof‐of‐principle and design of high throughput screens. Pharmacol Res 83, 38–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn PM, Spicer TP, Scampavia L & Janovick JA (2015). Assay strategies for identification of therapeutic leads that target protein trafficking. Trends Pharmacol Sci 36, 498–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran ME, Splawski I, Timothy KW, Vincent GM, Green ED & Keating MT (1995). A molecular basis for cardiac arrhythmia: HERG mutations cause long QT syndrome. Cell 80, 795–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delisle BP, Anson BD, Rajamani S & January CT (2004). Biology of cardiac arrhythmias: ion channel protein trafficking. Circ Res 94, 1418–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach AC, Stoehr SJ & Castle NA (2010). Pharmacological removal of human ether‐a‐go‐go‐related gene potassium channel inactivation by 3‐nitro‐N‐(4‐phenoxyphenyl) benzamide (ICA‐105574). Mol Pharmacol 77, 58–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianulis EC, Liu Q & Trudeau MC (2013). Direct interaction of eag domains and cyclic nucleotide‐binding homology domains regulate deactivation gating in hERG channels. J Gen Physiol 142, 351–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianulis EC & Trudeau MC (2011). Rescue of aberrant gating by a genetically encoded PAS (Per‐Arnt‐Sim) domain in several long QT syndrome mutant human ether‐a‐go‐go‐related gene potassium channels. J Biol Chem 286, 22160–22169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes CM (2012). Protein misfolding in disease and small molecule therapies. Curr Top Med Chem 12, 2460–2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Q, Keeney DR, Molinari M & Zhou Z (2005). Degradation of trafficking‐defective long QT syndrome type II mutant channels by the ubiquitin‐proteasome pathway. J Biol Chem 280, 19419–19425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Q, Zhang L, Vincent GM, Horne BD & Zhou Z (2007). Nonsense mutations in hERG cause a decrease in mutant mRNA transcripts by nonsense‐mediated mRNA decay in human long‐QT syndrome. Circulation 116, 17–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustina AS & Trudeau MC (2011). hERG potassium channel gating is mediated by N‐ and C‐terminal region interactions. J Gen Physiol 137, 315–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janovick JA, Stewart MD, Jacob D, Martin LD, Deng JM, Stewart CA, Wang Y, Cornea A, Chavali L, Lopez S, Mitalipov S, Kang E, Lee HS, Manna PR, Stocco DM, Behringer RR & Conn PM (2013). Restoration of testis function in hypogonadotropic hypogonadal mice harboring a misfolded GnRHR mutant by pharmacoperone drug therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110, 21030–21035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jou CJ, Barnett SM, Bian JT, Weng HC, Sheng X & Tristani‐Firouzi M (2013). An in vivo cardiac assay to determine the functional consequences of putative long QT syndrome mutations. Circ Res 112, 826–830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju P, Pages G, Riek RP, Chen PC, Torres AM, Bansal PS, Kuyucak S, Kuchel PW & Vandenberg JI (2009). The pore domain outer helix contributes to both activation and inactivation of the HERG K+ channel. J Biol Chem 284, 1000–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan A, Yu Z, Fishman GI & McDonald TV (2000). The dominant negative LQT2 mutation A561V reduces wild‐type HERG expression. J Biol Chem 275, 11241–11248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J, Chen XL, Wang H, Ji J, Cheng H, Incardona J, Reynolds W, Viviani F, Tabart M & Rampe D (2005). Discovery of a small molecule activator of the human ether‐a‐go‐go‐related gene (HERG) cardiac K+ channel. Mol Pharmacol 67, 827–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanters JK, Skibsbye L, Hedley PL, Dembic M, Liang B, Hagen CM, Eschen O, Grunnet M, Christiansen M & Jespersen T (2015). Combined gating and trafficking defect in Kv11.1 manifests as a malignant long QT syndrome phenotype in a large Danish p.F29L founder family. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 75, 699–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke Y, Hunter MJ, Ng CA, Perry MD & Vandenberg JI (2014). Role of the cytoplasmic N‐terminal Cap and Per‐Arnt‐Sim (PAS) domain in trafficking and stabilization of Kv11.1 channels. J Biol Chem 289, 13782–13791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke Y, Ng CA, Hunter MJ, Mann SA, Heide J, Hill AP & Vandenberg JI (2013). Trafficking defects in PAS domain mutant Kv11.1 channels: roles of reduced domain stability and altered domain‐domain interactions. Biochem J 454, 69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leidenheimer NJ & Ryder KG (2014). Pharmacological chaperoning: a primer on mechanism and pharmacology. Pharmacol Res 83, 10–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu QN & Trudeau MC (2015). Eag domains regulate LQT mutant hERG channels in human induced pluripotent stem cell‐derived cardiomyocytes. PLoS One 10, e0123951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Mahaut‐Smith MP, Varghese A, Huang CL, Kemp PR & Vandenberg JI (2001). Effects of premature stimulation on HERG K+ channels. J Physiol 537, 843–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsa E, Dixon JE, Medway C, Georgiou O, Patel MJ, Morgan K, Kemp PJ, Staniforth A, Mellor I & Denning C (2014). Allele‐specific RNA interference rescues the long‐QT syndrome phenotype in human‐induced pluripotency stem cell cardiomyocytes. Eur Heart J 35, 1078–1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta A, Sequiera GL, Ramachandra CJ, Sudibyo Y, Chung Y, Sheng J, Wong KY, Tan TH, Wong P, Liew R & Shim W (2014). Re‐trafficking of hERG reverses long QT syndrome 2 phenotype in human iPS‐derived cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc Res 102, 497–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss AJ & Schwartz PJ (2005). 25th anniversary of the International Long‐QT Syndrome Registry: an ongoing quest to uncover the secrets of long‐QT syndrome. Circulation 111, 1199–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss AJ, Zareba W, Kaufman ES, Gartman E, Peterson DR, Benhorin J, Towbin JA, Keating MT, Priori SG, Schwartz PJ, Vincent GM, Robinson JL, Andrews ML, Feng C, Hall WJ, Medina A, Zhang L & Wang Z (2002). Increased risk of arrhythmic events in long‐QT syndrome with mutations in the pore region of the human ether‐a‐go‐go‐related gene potassium channel. Circulation 105, 794–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muskett FW, Thouta S, Thomson SJ, Bowen A, Stansfeld PJ & Mitcheson JS (2011). Mechanistic insight into human ether‐a‐go‐go‐related gene (hERG) K+ channel deactivation gating from the solution structure of the EAG domain. J Biol Chem 286, 6184–6191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nerbonne JM & Kass RS (2005). Molecular physiology of cardiac repolarization. Physiol Rev 85, 1205–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng CA, Perry MD, Tan PS, Hill AP, Kuchel PW & Vandenberg JI (2012). The S4–S5 linker acts as a signal integrator for HERG K+ channel activation and deactivation gating. PLoS One 7, e31640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng CA, Phan K, Hill AP, Vandenberg JI & Perry MD (2014). Multiple interactions between cytoplasmic domains regulate slow deactivation of Kv11.1 channels. J Biol Chem 289, 25822–25832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry M, Sanguinetti M & Mitcheson J (2010). Revealing the structural basis of action of hERG potassium channel activators and blockers. J Physiol 588, 3157–3167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry MD, Ng CA & Vandenberg JI (2013). Pore helices play a dynamic role as integrators of domain motion during Kv11.1 channel inactivation gating. J Biol Chem 288, 11482–11491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riordan JR, Rommens JM, Kerem B, Alon N, Rozmahel R, Grzelczak Z, Zielenski J, Lok S, Plavsic N, Chou JL, et al (1989). Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science 245, 1066–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadrieh A, Domanski L, Pitt‐Francis J, Mann SA, Hodkinson EC, Ng CA, Perry MD, Taylor JA, Gavaghan D, Subbiah RN, Vandenberg JI & Hill AP (2014). Multiscale cardiac modelling reveals the origins of notched T waves in long QT syndrome type 2. Nat Commun 5, 5069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanguinetti MC, Curran ME, Spector PS & Keating MT (1996). Spectrum of HERG K+‐channel dysfunction in an inherited cardiac arrhythmia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93, 2208–2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanguinetti MC, Jiang C, Curran ME & Keating MT (1995). A mechanistic link between an inherited and an acquired cardiac arrhythmia: HERG encodes the IKr potassium channel. Cell 81, 299–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanguinetti MC & Jurkiewicz NK (1990). Two components of cardiac delayed rectifier K+ current. Differential sensitivity to block by class III antiarrhythmic agents. J Gen Physiol 96, 195–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]