Abstract

The wavelength-selective, reversible photocontrol over various molecular processes in parallel remains an unsolved challenge. Overlapping ultraviolet-visible spectra of frequently employed photoswitches have prevented the development of orthogonally responsive systems, analogous to those that rely on wavelength-selective cleavage of photo-removable protecting groups. Here we report the orthogonal and reversible control of two distinct types of photoswitches in one solution, that is, a donor–acceptor Stenhouse adduct (DASA) and an azobenzene. The control is achieved by using three different wavelengths of irradiation and a thermal relaxation process. The reported combination tolerates a broad variety of differently substituted photoswitches. The presented system is also extended to an intramolecular combination of photoresponsive units. A model application for an intramolecular combination of switches is presented, in which the DASA component acts as a phase-transfer tag, while the azobenzene moiety independently controls the binding to α-cyclodextrin.

While molecular photoswitches have proven useful in many fields, selective and reversible control over multiple switches is an unsolved challenge. Here, the authors report on a system consisting of two classes of photoswitches that can be addressed orthogonally and demonstrate the applicability in phase-transfer control.

While molecular photoswitches have proven useful in many fields, selective and reversible control over multiple switches is an unsolved challenge. Here, the authors report on a system consisting of two classes of photoswitches that can be addressed orthogonally and demonstrate the applicability in phase-transfer control.

Light as an external stimulus has been extensively used in chemistry, biology and material sciences to control processes and properties in a non-invasive manner with high spatiotemporal precision1,2,3,4,5,6,7. However, as systems grow more complex, this control often needs to be extended to processes that act simultaneously, using multiple sources of light at different wavelenghts8 in an orthogonal manner. When Bochet and co-workers9,10 reported the proof-of-principle for the irreversible wavelength-selective removal of photolabile protecting groups (PPGs; Fig. 1a) in 2000, it paved the way for numerous impressive applications8. These include functionalized surfaces11, hydrogels12 and lithography13, control of nucleic acids14, gene expression15,16, regulation of enzyme activity17,18 and interfering with neuronal processes19. Despite the successful use of this concept, light-mediated uncaging is an inherently irreversible process6, which limits future applications towards responsive systems both in material and life sciences.

Figure 1. Orthogonal reversible photoswitching.

Comparison of concepts described in this manuscript: wavelength-selective uncaging of photolabile protecting groups (a) and orthogonal photoswitching (b). Molecular structures and switching of DASAs (DASA 1 and 2 (c)) and azobenzenes (3–6 (d)) with a conceptual representation of the ultraviolet-visible spectra of compounds 1 and 3 (e).

On the other hand, the field of molecular photoswitches exploits the reversibility of the photoswitching process2,3,20,21,22,23,24. However, the concept of addressing photoactive molecules in parallel with light of different wavelengths has not been translated from wavelength-selective uncaging of PPGs to independent photoswitching (Fig. 1b). Such orthogonal control has great potential for employment in various fields, as many of the above-mentioned applications used for wavelength-selective uncaging would benefit from the reversibility of activation. Furthermore, reversible orthogonal control would enable independent modulation of different material properties and investigation of complex networks of signalling pathways in biological systems. The wavelength selectivity (orthogonality) of the photoswitching is essential and the lack thereof currently represents a major limiting factor for successful applications (N.B.: throughout this article we refer to orthogonality as a characteristic of a system, where each component of the system can be controlled independently and irrespective of the order of addressing)25.

Although the idea of combining two different photoswitches in an intermolecular manner and addressing them independently may seem simple, its execution remains a major challenge26. Wavelength-selective control was so far confined to irreversible processes likely because of the fact that many of the most abundantly used photoswitches, such as azobenzenes, diarylethenes and spiropyrans, have overlapping absorption bands in the ultraviolet-visible region2,8. Thus, it is difficult to find spectral regions with large differences in photoswitching efficiency (defined, at a given wavelength, as a product of extinction coefficient, ɛ and quantum yield, φ). Moreover, the possibility of undesirable energy transfer between the chromophores27 can lead to a major loss of selectivity. Herein, we present an orthogonal, intermolecular combination of two classes of photoswitches and their intramolecular combination as a first-generation orthogonally addressable, dual functional molecular system. The reported intermolecular combination of photoswitches is based on a donor–acceptor Stenhouse adduct (DASA, Fig. 1c) and an azobenzene (Fig. 1d). Both photoswitches can be independently controlled by irradiation with light of three different wavelengths and by taking advantage of a thermal isomerization process. The modular and experimentally robust combination allows for functionalization of each constituent. A model application for an intramolecular combination of switches is presented, in which the DASA component acts as a phase-transfer tag, while the azobenzene moiety independently controls the binding to α-cyclodextrin (α-CD).

Results

Selecting a compatible photoswitch pair

Defining a photochromically compatible pair of photoswitches would constitute the first example of wavelength-selective/orthogonal control of multiple photoswitches in one solution. For this reason, we aimed to find compatible classes of photoswitches (Fig. 1), especially those that would exhibit a high complementarity in the 300–800 nm spectral region where photoswitches normally operate (Fig. 1e). We chose azobenzene photoswitches as one class: they have been successfully applied in molecular photocontrol20,21,22,23,24,28,29,30,31, are easily accessible and allow for custom modification, functionalization and spectral fine-tuning. Azobenzenes have their main absorption bands located between 300 and 500 nm (π–π* and n–π* transitions; Fig. 1d,e and Table 1)20,32. We envisioned that the T-type2 DASAs (DASA 1 and DASA 2, Fig. 1c) could be used as the complementary class33,34 since they show very little absorption between 300 and 500 nm (Fig. 1c,e and Table 1)35,36,37. Owing to the fact that the reverse switching of DASAs is thermally driven33,34,36,37, three different wavelengths would be sufficient for wavelength-selective control. Importantly, for the design of orthogonal systems, one can exploit the tunability of thermal half-lives of the thermodynamically unstable states of the photoswitches in use. By changing the substitution pattern of azobenzenes, both very long and very short thermal half-lives have been attained. Increased thermal stability could be achieved, for example, through ortho-substitution32,38,39,40,41. On the other hand, compounds with shortened thermal half-lives can be obtained by tuning of the electron density, through incorporation of both electron-donating groups (for example, -NMe2 and -OMe), electron-withdrawing groups and combinations of both (push–pull systems)42. For the DASAs a clear relation between half-life and structure has not been determined yet33,34. However, it has been shown that changing the acceptor can influence the half-life to some extent33,34. Methylbarbituric acid-based cyclized DASAs (Fig. 1c, X=NMe; Y=C=O) are generally less thermally stable in comparison with the ones based on Meldrum's acid (Fig. 1c, X=O; Y=C(Me)2). Finally, tuning half-lives of switches is often relatively independent of structural features required for function. This leaves ample space to tune the thermal relaxation rate of switches to magnitudes needed for different applications20,21,22,23,24,28,29,30,31,43.

Table 1. Properties of photoswitches 1 and 3.

| Entry | λ (nm) | Open-DASA 1, ɛ (102 M−1 cm−1) | Trans-azobenzene 3, ɛ (102 M−1 cm−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 360 | <3 | 356.5±4.1 |

| 2 | 365 | <3 | 349.4±4.2 |

| 3 | 370 | <3 | 324.8±4.1 |

| 4 | 430 | <3 | 17.0±0.8 |

| 5 | 445 | 5.7±1.5 | 16.7±0.7 |

| 6 | 515 | 279.7±2.9 | 4.3±0.7 |

| 7 | 570 | 1758.0±15.3 | <3 |

DASA, donor–acceptor Stenhouse adduct.

Overview of molar absorptivities of photoswitches 1 and 3 at relevant wavelengths.

Intermolecular combination of photoswitches

Initially, we studied push–pull azobenzene 3 in combination with DASA 1 (Fig. 1 and Table 1). The 4′-methoxy group in azobenzenes increases photostationary states44 (PSS, defined as the percentage of the thermodynamically unstable isomer that can be produced upon irradiation at a given wavelength), while the ester moiety represents a handle for convenient functionalization. The absorption spectrum of the mixture of 1 and 3 is, to a large degree, a linear combination of the spectra of the separate photoswitches, indicating a low level of intermolecular energy transfer (Supplementary Fig. 39)26.

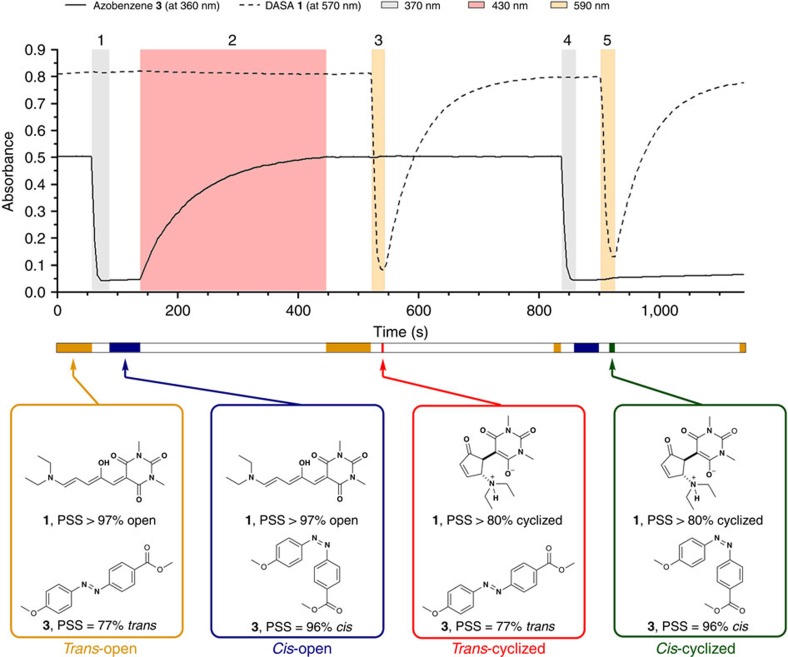

The combination of photoswitches 1 and 3 showed a remarkably high level of wavelength selectivity, apparent in ultraviolet-visible spectra and reversible photochromism plots (Fig. 2). Irradiation of azobenzene 3 led to a selective, nearly quantitative trans–cis isomerization (λ=370 nm, irradiation 1, Fig. 2), which proceeds with a quantum yield of ϕ=0.15. The relatively long half-life of the cis-isomer of azobenzene 3 (t1/2>8 h; Table 2) makes it thermally stable on the timescale of the experiment (<1 h). Irradiation of the cis-3 isomer (λ=430 nm, irradiation 2, Fig. 2) allowed selective cis–trans isomerization without affecting photoswitch 1. DASA 1 could be selectively cyclized by longer wavelength irradiation (λ=590 nm, irradiation 3, Fig. 2), without affecting the azobenzene, after which it showed a short thermal half-life for cycloreversion (37 s at room temperature; Table 2). DASA 1 can also be switched selectively (irradiation 5, Fig. 2) without affecting the azobenzene 3 after it has been switched to the cis-isomer (irradiation 4, Fig. 2). By using a broad-spectrum visible light source (white light, Supplementary Table 1), both switches could be addressed at the same time (Supplementary Fig. 41) and different combinations of PSS could be attained by adjusting the irradiation intensity and/or duration (Supplementary Fig. 41). Moreover, this intermolecular combination operates successfully throughout a large concentration range (Supplementary Figs 51–53).

Figure 2. Orthogonal control of a mixture of photoswitches.

Proof-of-concept for the reversible and orthogonal photocontrol in a mixture of DASA 1 (—) and azobenzene 3 (- - -). The orthogonal photoswitching of both compounds in one solution (1: ∼4 μM; 3: ∼20 μM; toluene, room temperature) was monitored at characteristic wavelengths for each photoswitch (λ=360 nm for 3 and λ=570 nm for 1). Steps 1–5 indicate distinct irradiation experiments. Coloured areas indicate different wavelengths of irradiation. The coloured bar below the figure indicates the different states of the photoswitches. The structure of photoswitches and their corresponding photostationary states (determined by 1H-NMR and ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy) are given for the different states during photoswitching.

Table 2. Overview of photoswitch characteristics.

| Entry | Switch | t1/2 | λmax (nm) |

PSS for irradiation at

λ** |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 365 | 430 | 590 | White light | ||||

| 1 | Azo 3 | >8 h | 360 (π–π*) | 4:96 | 70:30 | ND | 77:23 |

| 445 (n–π*) | |||||||

| 2 | Azo 4 | 180 s | 434 (π–π*) | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 374 (n–π*) | |||||||

| 3 | Azo 5 | >8 h | 320 (π–π*) | 32:68† | 82:18 | ND | 77:23 |

| 436 (n–π*) | |||||||

| 4 | Azo 6 | >8 h | 348 (π–π*) | <3:97 | 69:31 | ND | 76:24 |

| 444 (n–π*) | |||||||

| 5 | DASA 1 | 37 s | 570 | ND | ND | <20:80‡ | <20:80‡ |

| 6 | DASA 2 | 130 s | 545 | ND | ND | <20:80‡,§ | <20:80‡ |

DASA, donor–acceptor Stenhouse adduct; ND, not determined; PSS, photostationary state.

**Trans/cis

†Same for 312 nm.

‡Open/cyclized.

§546 nm.

In summary, in a mixture of photoswitches 1 and 3 (Fig. 2), azobenzene 3 could be selectively switched from trans to cis (irradiation 1) and back from cis to trans (irradiation 2). The same applies for DASA photoswitch 1, which could be selectively cyclized (irradiation 3) and then relaxed back to its thermally stable state. It is important to note that full chromatic orthogonality was observed because both states of 1, as well as the thermal relaxation process, were not affected by light pulses that address 3 (irradiations 1, 2 and 4). Similarly, both states of 3 were not affected by light pulses addressing 1 (irradiations 3 and 5).

Structural scope of photoswitches

Subsequently, we investigated whether other azobenzenes could be used in a two-switch system with compound 1. Towards that end, azobenzenes 4–6 (Fig. 3 and Table 2) were selected. These photochromes are not only structurally diverse, but they also exhibit very different functional characteristics: the λmax of 4 is bathochromically shifted20,38,39,40,41,42, whereas λmax of 5 and 6 are hypsochromically shifted (Fig. 3 and Table 2) as compared with compound 3. Moreover, they differ markedly in the half-lives of their thermally unstable cis-isomers as compared with 3, with a shortened half-life for 4 20,32,38,39,40,41,42, comparable half-life for 6 and a longer half-life for 5 (ref. 20; Table 2; Supplementary Figs 16, 20 and 24). All combinations of DASA 1 with azobenzenes 3, 4, 5 or 6 showed chromatic orthogonality, thus showing the tolerance of this photoswitch combination towards structural modification of the azobenzene core with functionally different behaviour (Supplementary Figs 43–48).

Figure 3. Structural scope of photoswitches.

Structural scope of DASAs (1 and 2) and azobenzenes (3–6). Overlay of the ultraviolet-visible absorption spectra of compounds 1–6 (compounds 1 and 2: ∼4 μM; compounds 3–6: ∼20 μM; toluene; room temperature) with their corresponding absorption maxima.

We then investigated possibilities for structural diversity of DASAs that can be incorporated in an orthogonal switching system with azobenzenes. In principle, changing the acceptor part of this photochromic compound affects the absorption maximum and thermal half-life, while the donor moiety has little influence on λmax, affecting only its solubility33,34. DASA 2 (Fig. 3), with a Meldrum's acid-derived acceptor moiety, shows a hypsochromically shifted absorption maximum (Fig. 3 and Table 2) and its cyclized form exhibits a longer half-life (∼130 s; Supplementary Fig. 8), when compared with that of DASA 1 (refs 33, 34). We selected azobenzene 6 (Fig. 3) to study the orthogonality of photoswitching in solution since it is compatible with DASA 2 because of its hypsochromically shifted π–π* absorption band (Fig. 3, Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 22). Gratifyingly, both switches 2 and 6 can also be selectively addressed in parallel with light of different wavelengths (Supplementary Figs 49 and 50). The flexibility with regard to the DASA photoswitch highlights the robustness and modularity of the photoswitch combination and bodes well for versatile use in different applications.

Orthogonal photoswitching in an intramolecular system

Apparently, loss of selectivity through energy transfer did not pose a problem for the intermolecular system described thus far, even at high concentrations up to ∼80 μM (1) and ∼400 μM (3; Supplementary Figs 51–53). Therefore, the reversible photocontrol in the intermolecular case is purely dependent on the spectral properties of the two photoswitches involved. For an intramolecular combination, on the other hand, linker design, geometry and distance of the photochromes become more important26. While intramolecular energy transfer between chromophores can drastically reduce the switching selectivity8,26,27, it can be partially controlled by adjusting the lifetime of the photo-excited state and/or by changing the design of the linker8,26,27. Furthermore, properties that arise from energy transfer and the interplay of the combination of two photoswitches can sometimes be desired. This is the case, for example, in molecular logics26,45,46,47,48, where such hybrid multiswitches (or multiphotochromes) allow (sequential) access to multiple different states45,46, usually in combination with external stimuli other than light49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56.

To probe whether the level of selectivity of the intermolecular combination could be retained in the intramolecular system, or whether new properties could be observed, we combined an azobenzene and a DASA photoswitch into a single molecule. Towards that end, compounds 7 and 8, which differ only in the length of the linker, were synthesized (Fig. 4) and the selectivity of their photoresponsiveness was evaluated (Fig. 5).

Figure 4. Synthesis of compounds 7 and 8.

Compounds 7 and 8 were used to probe the chromatic selectivity in intramolecular photoswitching.

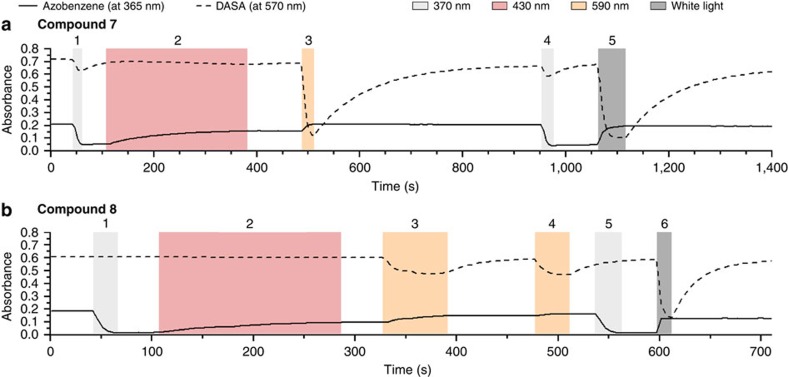

Figure 5. Selectivity in intramolecular photoswitching.

Reversible photochromism of an intramolecular photoswitch combination of azobenzene and DASA with different linker lengths. Compound 7 (a) and compound 8 (b; ∼4 μM; toluene, room temperature). Steps 1–6 indicate distinct irradiation experiments.

Importantly, the selective switching of the azobenzene moiety is retained. However, irradiation with λ=590 nm not only switched the DASA moiety but also affected, to some extent, the azobenzene part in both 7 and 8 (Fig. 5). Generally, improved selectivities were observed with the elongated linker unit (from -(CH2)4- to -(CH2)12-). In compound 7 (shorter linker), irradiation at λ=370 nm (Fig. 5a) does partially affect the DASA moiety, which is not observed for compound 8 (longer linker). Interestingly, compound 8 shows a slight decrease in addressability of exclusively the DASA photoswitch with λ=590 nm, but not with white light (Fig. 5b). No such effect is observed for the compound with shorter linker (compound 7). As a control experiment, the intermolecular switching of the corresponding azobenzenes in combination with the DASA photoswitch 1 was studied and orthogonality was observed (Supplementary Figs 54–58).

Modulation of phase transfer and supramolecular interactions

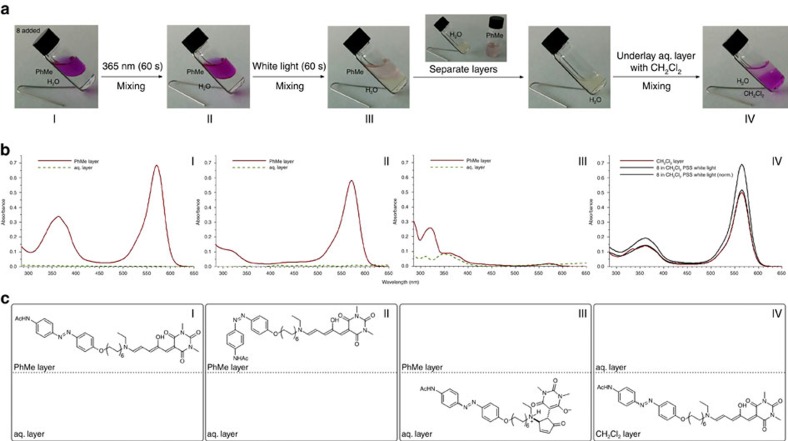

We proceeded to apply this intramolecular system for controlling the location and the function of the molecule. Previously reported extraction experiments of DASA molecules33,34 established the potential of DASAs as a phase-transfer tag34,37. Reversible photoswitching of DASAs is only observed in aromatic solvents. Polar protic solvents (as, for example, methanol or water) stabilize DASA's zwitterionic cyclized state, whereas halogenated solvents favour the elongated triene structure. Photoswitching results in formation of the hydrophilic zwitterionic cyclized form and phase transfer to the aqueous layer34. We envisioned exploiting this behaviour to transport photoswitchable cargo that is, an azobenzene. On an independent level of photocontrol, the isomerization of the azobenzene could be used to manipulate a certain function, for example, the well-known host–guest binding to CDs (especially α-CD)57,58,59,60. Therefore, we set off to evaluate a model system with dual functionality (Fig. 6) in which the DASA moiety of 8 controls the phase where the molecule resides (location), whereas the azobenzene moiety controls the supramolecular binding to α-CD (function). In toluene, the azobenzene moiety of compound 8 could be switched selectively between trans- and cis-forms (Fig. 5b). Upon cyclization of the DASA moiety, phase transfer of compound 8 to the aqueous layer is expected. In the aqueous layer, the photocontrol of the azobenzene moiety would allow control over binding to the water-soluble α-CD.

Figure 6. Design principle of switchable phase transfer and binding.

Schematic outline of the application of light-controlled guest 8 with light-controlled phase-transfer properties. Compound 8 (trans-open) is soluble in toluene. Irradiation with λ=365 nm (trans–cis isomerization) and λ=430 nm (cis–trans isomerization) controls the state of the azobenzene. Cyclization of the DASA moiety with visible light results in phase transfer of compound 8. In the aqueous layer (pH ⩾9), the azobenzene binds the water-soluble α-CD in its trans-state, but not in the cis-state.

Towards that end, we established the phase-transfer behaviour of DASA in the intramolecular system 8. Inspired by traditional logPI(oct/wat) measurements61, a functional phase-transfer system was designed to operate at pH 9 (using a saturated aqueous NaHCO3 solution to adjust the pH Fig. 7). The extraction experiment described in Fig. 7 establishes the photoswitching and light-controlled phase-transfer behaviour of compound 8. Compound 8 is dissolved in toluene and the organic layer is underlayed with water (pH 9). Upon irradiation of the biphasic mixture (stage I, Fig. 7) with λ=365 nm, the azobenzene part of 8 is selectively switched, as can be observed by ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy (stage II, Fig. 7). Subsequent irradiation with white light results in a successful phase transfer of 8 to the aqueous layer (stage III, Fig. 7). Separation of the biphasic mixture and addition of dichloromethane to the aqueous phase results in back-extraction and recolouration of the organic solution (stage IV, Fig. 7), taking advantage of the short half-life of the DASA 1-type moiety. Importantly, the geometry of the azobenzene moiety can be controlled without affecting the DASA moiety in the organic phase (Fig. 7). Isolation of phase-transferred compound 8 and photoswitching in water (pH ⩾9, K2CO3) established reversibility with negligible fatigue of the azobenzene moiety in the basic aqueous phase (Supplementary Figs 61, 62 and 69).

Figure 7. Demonstration of light-controlled phase transfer.

Dynamic phase transfer of compound 8 in a toluene/aqueous NaHCO3 (pH=9) mixture. The independent switching and phase-transfer events can be monitored by phase-colour (a) and ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy (b). Stage I: initial conditions, compound 8 resides in the organic phase (purple colour). Stage II: the azobenzene part of compound 8 was switched with irradiation at λ=365 nm. The DASA part remains untouched. Stage III: irradiation with white light results in the cyclization of the DASA moiety, decolouration and phase transfer of compound 8. Stage IV: separating the layers and back-extraction of the aqueous layer with dichloromethane results in back-transfer of compound 8 to the organic phase, as can be observed by the recolouration of this phase (purple colour). The presence of compounds in the different phases is schematically depicted (c).

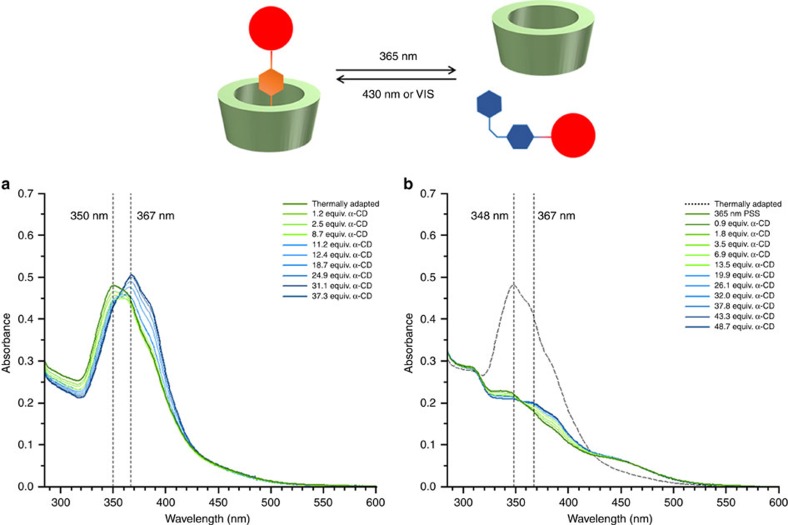

Having established the light-induced phase transfer of compound 8 through DASA cyclization (light-control of location), we studied the possibility of controlling host–guest binding of compound 8 in water (light control of function). CDs are well known as host molecules with a multitude of studied guest molecules57,58,60. α-CD binds trans-azobenzenes but not cis-azobenzenes59,62.

Compound 8 was isolated after phase transfer and was then subjected to binding studies with α-CD in water (pH ⩾9; ref. 57). A clear change in the absorption spectrum upon titration of the host was observed (Supplementary Fig. 63) for the thermally adapted compound 8, indicating the binding of trans-azobenzene moiety of 8 to α-CD. For irradiated samples, this effect was markedly reduced (Supplementary Figs 64–67), suggesting a much weaker binding of the cis-azobenzene moiety of 8 to α-CD. Photoswitching is retained even in the bound state, where interestingly different PSS values are observed (Supplementary Figs 68–70). Thus, by switching the azobenzene moiety, the affinity for the α-CD host can be tuned (Fig. 8).

Figure 8. Binding between azobenzene and α-CD.

Binding studies on the host–guest binding of α-CD and compound 8. Titration of α-CD to an aqueous solution (pH ⩾9) of compound 8 (11 μM). A clear change of the absorption spectrum is observed, indicating the binding of the trans-azobenzene moiety of 8 (a). Binding is significantly reduced in a photostationary state reached under 365 nm irradiation (inducing trans–cis isomerization; b).

Overall, the azobenzene moiety of compound 8 can be independently controlled by light in the organic phase with irradiation at λ=365 nm (trans–cis isomerization; Figs 5b and 7) and λ=430 nm (cis–trans isomerization; Fig. 5b). Upon switching of the DASA moiety with white light, compound 8 undergoes phase transfer to the basic aqueous layer. Herein, the trans-azobenzene moiety binds to α-CD more strongly than the cis-azobenzene one. Compound 8 can be recovered from the aqueous layer by back-extraction to dichloromethane. In summary, compound 8 incorporates the two independently photocontrolled, functionally different capabilities for phase transfer, induced by DASA cyclization and host–guest binding, dependent on the geometry of the azobenzene moiety.

Discussion

In conclusion, an intermolecular two-switch system consisting of a DASA and an azobenzene was developed by a rational, spectra-guided design. The robustness of the photoswitch combination is illustrated by the compatibility of differently substituted azobenzenes, as well as DASAs. The flexibility in functional group substitution emphasizes the generality and modularity of this approach and may potentially also allow combination with other classes of photoswitches or PPGs. Furthermore, control of thermal relaxation allows specific tailoring of the switch to the needs of the system. Recent non-orthogonal applications of independent switches in the same solution highlight the great potential of our approach63,64,65,66,67,68. The intramolecular photoswitching extends the applicability of this combination, which was exemplified by a dual functional molecule where both the binding to α-CD and phase transfer can be controlled with different wavelengths of light. The intramolecular combination shows interesting switching behaviour dependent on the linker length—an aspect that will be studied in-depth in the future. The presented study show levels of orthogonal selectivity that are unparalleled both for wavelength-selective uncaging8 and multiphotochromes26. It represents a major step towards the development of future orthogonal and reversible photoswitchable tools that can be used for non-invasively interfering with and the manipulation of multifunctional molecular systems. Future research should focus on overcoming the strong solvent dependence of the photoswitching of the DASAs and orthogonal switching in the near infrared region of the spectrum38,39,40,41.

Methods

Synthesis of photoswitches and combinations thereof

The synthesis of compounds 1–9 is detailed in Supplementary Methods. For NMR characterization of the described compounds, see Supplementary Figs 71–83.

Photochemical characterization

Irradiation of samples in toluene (Uvasol) was performed with different light sources and filters (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Photoswitching was observed with an Agilent 8453 UV-Visible Spectrophotometer in a 10 mm quartz cuvette using Uvasol grade solvents. Generally, the concentrations of the photoswitches were adjusted to result in a measured absorbance between 0.5 and 1.0 (a.u.). Half-lives of photoswitches were measured at λmax and fitted with single exponential process.

For the photochemical characterization of photoswitches 1–9, see Supplementary Figs 1–31. For the determination of photostationary states reached, see Supplementary Figs 32–38.

Determination of quantum yields

The quantum yield was determined by following initial photoswitching kinetics (percentage of switching ∼10%) as decrease in absorbance at λmax and using the light intensity determined from standard ferrioxalate actinometry69. A more detailed description can be found in Supplementary Methods.

Photoswitching experiments

Each mixture of compounds was analysed by measuring ultraviolet-visible spectra of the different accessible states and by kinetic measurement of the time-dependent reversible photochromism. Henceforth, each photoswitch was followed at its λmax. Importantly, samples were irradiated during measurements at an ∼90° angle to the light path of the ultraviolet-visible spectrometer with distances from light source and their respective intensities at this distance detailed in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. For the photochemical characterization of two-photoswitch mixtures, see Supplementary Figs 39–50. For photoswitching at higher concentrations, see Supplementary Figs 51–53. For the photochemical characterization of the intramolecular combinations of both switches, see Supplementary Figs 54–58.

Model application studies

For an analysis of the phase-transfer behaviour of compounds 3 and 9, see Supplementary Fig. 59. For the phase-transfer behaviour of compound 8, see Supplementary Fig. 60. Experimental details for the binding studies and switching behaviour of the azobenzene moiety of cyclized-8 can be found in the Supplementary Methods section and Supplementary Figs 61–70 and Supplementary Tables 3–7.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information Files.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Lerch, M. M. et al. Orthogonal photoswitching in a multifunctional molecular system. Nat. Commun. 7:12054 doi: 10.1038/ncomms12054 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1-83, Supplementary Tables 1-7, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge generous support from NanoNed, The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO-CW, Top grant to B.L.F. and NWO VIDI grant no. 723.014.001 for W.S.), the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Science (KNAW), the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science (Gravitation programme 024.001.035) and the European Research Council (Advanced Investigator Grant no. 227897 to B.L.F). Furthermore, we thank the Swiss Study Foundation for a fellowship to M.M.L. We also thank T. Tiemersma-Wegman for ESI-MS analyses and we especially thank Professor Dr W.R. Browne, Dr S.J. Wezenberg and Juan Chen for technical assistance and discussions, and Professor Dr Denis Jacquemin for fruitful discussions.

Footnotes

Author contributions B.L.F. and W.S. guided the research. B.L.F., W.S., M.J.H., W.A.V. and M.M.L. have designed the experiments. M.M.L. has conducted the experiments. M.M.L. has drafted the article, and all authors contributed to the final manuscript.

References

- Griesbeck A. G., Oelgemöller M. & Ghetti F. in Handbook of Organic Photochemistry and Photobiology CRC Press (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Feringa B. L., Browne W. R. (eds). Molecular Switches 2nd edWiley-VCH: Weinheim (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Russew M.-M. & Hecht S. Photoswitches: from molecules to materials. Adv. Mater. 22, 3348–3360 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klán P. et al. Photoremovable protecting groups in chemistry and biology: reaction mechanisms and efficacy. Chem. Rev. 113, 119–191 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.-M., Larson D. R. & Lawrence D. S. Illuminating the chemistry of life: design, synthesis, and applications of ‘caged' and related photoresponsive compounds. ACS Chem. Biol. 4, 409–427 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brieke C., Rohrbach F., Gottschalk A., Mayer G. & Heckel A. Light-controlled tools. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 8446–8476 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szobota S. & Isacoff E. Y. Optical control of neuronal activity. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 39, 329–348 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen M. J., Velema W. A., Lerch M. M., Szymanski W. & Feringa B. L. Wavelength-selective cleavage of photoprotecting groups: Strategies and applications in dynamic systems. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 3358–3377 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bochet C. G. Wavelength-selective cleavage of photolabile protecting groups. Tetrahedron Lett. 41, 6341–6346 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Blanc A. & Bochet C. G. Wavelength-controlled orthogonal photolysis of protecting groups. J. Org. Chem. 67, 5567–5577 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguel V. S., Bochet C.G. & del Campo A. Wavelength-selective caged surfaces: how many functional levels are possible? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 5380–5388 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azagarsamy M. A. & Anseth K. S. Wavelength-controlled photocleavage for the orthogonal and sequential release of multiple proteins. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 13803–13807 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Fernández L. et al. Dual photosensitive polymers with wavelength-selective photoresponse. Adv. Mater. 26, 5012–5017 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues-Correia A., Weyel X. M. M. & Heckel A. Four levels of wavelength-selective uncaging for oligonucleotides. Org. Lett. 15, 5500–5503 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier L. et al. A blue-absorbing photolabile protecting group for in vivo chromatically orthogonal photoactivation. ACS Chem. Biol. 8, 1528–1536 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazoe S., Liu Q., McQuade L. E., Deiters A. & Chen J. K. Sequential gene silencing using wavelength-selective caged morpholino oligonucleotides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 10114–10118 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priestman M. A., Sun L. & Lawrence D. S. Dual wavelength photoactivation of cAMP- and cGMP-dependent protein kinase signaling pathways. ACS Chem. Biol. 6, 377–384 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velema W. A., van der Berg J. P., Szymanski W., Driessen A. J. M. & Feringa B. L. Orthogonal control of antibacterial activity with light. ACS Chem. Biol. 9, 1969–1974 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amatrudo J. M., Olson J. P., Agarwal H. K. & Ellis-Davies G. C. R. Caged compounds for multichromic optical interrogation of neural systems. Eur. J. Neurosci. 41, 5–16 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beharry A. A. & Woolley G. A. Azobenzene photoswitches for biomolecules. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 4422–4437 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymański W., Beierle J. M., Kistemaker H. A. V, Velema W. A. & Feringa B. L. Reversible photocontrol of biological systems by the incorporation of molecular photoswitches. Chem. Rev. 113, 6114–6178 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehrentz T., Schönberger M. & Trauner D. Optochemical genetics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 12156–12182 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velema W. A., Szymanski W. & Feringa B. L. Photopharmacology: Beyond proof of principle. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 2178–2191 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broichhagen J., Frank J. A. & Trauner D. A roadmap to success in photopharmacology. Acc. Chem. Res. 48, 1947–1960 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barany G. & Merrifield R. B. A new amino protecting group removable by reduction. Chemistry of the dithiasuccinoyl (Dts) function. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 99, 7363–7365 (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fihey A., Perrier A., Browne W. R. & Jacquemin D. Multiphotochromic molecular systems. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 3719–3759 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymo F. M. & Tomasulo M. Electron and energy transfer modulation with photochromic switches. Chem. Soc. Rev. 34, 327–336 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göstl R., Senf A. & Hecht S. Remote-controlling chemical reactions by light: towards chemistry with high spatio-temporal resolution. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 1982–1996 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iamsaard S. et al. Conversion of light into macroscopic helical motion. Nat. Chem. 6, 229–235 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware T. H., McConney M. E., Wie J. J., Tondiglia V. P. & White T. J. Actuating materials. Voxelated liquid crystal elastomers. Science 347, 982–984 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baroncini M. et al. Photoinduced reversible switching of porosity in molecular crystals based on star-shaped azobenzene tetramers. Nat. Chem. 7, 634–640 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandara H. M. D. & Burdette S. C. Photoisomerization in different classes of azobenzene. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 1809–1825 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmy S. et al. Photoswitching using visible light: a new class of organic photochromic molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 8169–8172 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmy S., Oh S., Leibfarth F. A., Hawker C. J. & Read de Alaniz J. Design and synthesis of donor-acceptor Stenhouse adducts: a visible light photoswitch derived from furfural. J. Org. Chem. 79, 11316–11329 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S. et al. Spatiotemporal photopatterning on polycarbonate surface through visible light responsive polymer bound DASA compounds. ACS Macro Lett. 4, 1273–1277 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason B. P. et al. A temperature-mapping molecular sensor for polyurethane-based elastomers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, 041906 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Helmy S. & Read de Alaniz J. Chapter three - photochromic and thermochromic heterocycles. Adv. Heterocycl. Chem. 117, 131–177 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Beharry A. A., Sadovski O. & Woolley G. A. Azobenzene photoswitching without ultraviolet light. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 19684–19687 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong M., Babalhavaeji A., Samanta S., Beharry A. A. & Woolley G. A. Red-shifting azobenzene photoswitches for in vivo use. Acc. Chem. Res. 48, 2662–2670 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bléger D., Schwarz J., Brouwer A. M. & Hecht S. o-Fluoroazobenzenes as readily synthesized photoswitches offering nearly quantitative two-way isomerization with visible light. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 20597–20600 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bléger D. & Hecht S. Visible-light-activated molecular switches. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 11338–11349 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura N. et al. Thermal cis-to-trans isomerization of substituted azobenzenes II. Substituent and solvent effects. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 49, 1381–1387 (1976). [Google Scholar]

- Kienzler M. A. et al. A red-shifted, fast-relaxing azobenzene photoswitch for visible light control of an ionotropic glutamate receptor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 17683–17686 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymański W., Wu B., Poloni C., Janssen D. B. & Feringa B. L. Azobenzene photoswitches for Staudinger-Bertozzi ligation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 2068–2072 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frigoli M. & Mehl G. H. Multiple addressing in a hybrid biphotochromic system. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 5048–5052 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szalóki G., Sevez G., Berthet J., Pozzo J.-L. & Delbaere S. A simple molecule-based octastate switch. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 13510–13513 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Silva A. P. in Molecular Logic-Based Computation, Monographs in Supramolecular Chemistry RSC Publishing (2012). [Google Scholar]

- de Silva A. P., James M. R., McKinney B. O. F., Pears D. A. & Weir S. M. Molecular computational elements encode large populations of small objects. Nat. Mater. 5, 787–790 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straight S. D. et al. All-photonic molecular XOR and NOR logic gates based on photochemical control of fluorescence in a fulgimide–porphyrin–dithienylethene triad. Adv. Funct. Mater. 17, 777–785 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Andréasson J., Straight S. D., Moore T. A., Moore A. L. & Gust D. Molecular all-photonic encoder-decoder. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 11122–11128 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andréasson J. et al. All-photonic multifunctional molecular logic device. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 11641–11648 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bälter M., Li S., Nilsson J. R., Andréasson J. & Pischel U. An all-photonic molecule-based parity generator/checker for error detection in data transmission. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 10230–10233 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myles A. J., Wigglesworth T. J. & Branda N. R. A multi-addressable photochromic 1,2-dithienylcyclopentene-phenoxynaphthacenequinone hybrid. Adv. Mater. 15, 745–748 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Kinashi K. & Ueda Y. Synthesis and photochromic behavior of bi-functional photochromic compound. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 445, 223/[513]–230/[520] (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Kinashi K., Ono Y., Naitoh Y., Otomo A. & Ueda Y. Time-resolved fluorescence study on the photomerocyanine form of spiropyran and its derivative with azobenzene. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 217, 35–39 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- He Y., Zhu Y., Chen Z., He W. & Wang X. Remote-control photocycloreversion of dithienylethene driven by strong push-pull azo chromophores. Chem. Commun. 49, 5556–5558 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rekharsky M. V. & Inoue Y. Complexation thermodynamics of cyclodextrins. Chem. Rev. 98, 1875–1918 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors K. A. Population characteristics of cyclodextrin complex stabilities in aqueous solution. J. Pharm. Sci. 84, 843–848 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nepogodiev S. A. & Stoddart J. F. Cyclodextrin-based catenanes and rotaxanes. Chem. Rev. 98, 1959–1976 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crini G. Review: a history of cyclodextrins. Chem. Rev. 114, 10940–10975 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leo A., Hansch C. & Elkins D. Partition coefficients and their uses. Chem. Rev. 71, 525–616 (1971). [Google Scholar]

- Tomatsu I., Hashidzume A. & Harada A. Photoresponsive hydrogel system using molecular recognition of α-cyclodextrin. Macromolecules 38, 5223–5227 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Scott T. F., Kowalski B. A., Sullivan A. C., Bowman C. N. & McLeod R. R. Two-color single-photon photoinitiation and photoinhibition for subdiffraction photolithography. Science 324, 913–917 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W.-C., Lee Y.-W. & Chen C.-T. Diastereoselective, synergistic dual-mode optical switch with integrated chirochromic helicene and photochromic bis-azobenzene moieties. Org. Lett. 12, 1472–1475 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube H. & Rebek J. Selective guest exchange in encapsulation complexes using light of different wavelenghts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 3207–3210 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishioka H., Liang X., Kato T. & Asanuma H. A photon-fueled DNA nanodevice that contains two different photoswitches. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 1165–1168 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiltebrandt K. et al. λ-Orthogonal pericyclic macromolecular photoligation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 2838–2843 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna D., Udayabhaskararao T., Zhao H. & Klajn R. Orthogonal light-induced self-assembly of nanoparticles using differently substituted azobenzenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 12394–12397 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatchard C. G. & Parker C. A. A new sensitive chemical actinometer. II. Potassium ferrioxalate as a standard chemical actinometer. Proc. R Soc. Lond. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 235, 518–536 (1956). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1-83, Supplementary Tables 1-7, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information Files.