Abstract

Although classical, negatively charged antifolates such as methotrexate possess high affinity for the dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) enzyme, they are unable to penetrate the bacterial cell wall, rendering them poor antibacterial agents. Herein, we report a new class of charged propargyl-linked antifolates that capture some of the key contacts common to the classical antifolates while maintaining the ability to passively diffuse across the bacterial cell wall. Eight synthesized compounds exhibit extraordinary potency against Gram-positive S. aureus with limited toxicity against mammalian cells and good metabolic profile. High resolution crystal structures of two of the compounds reveal extensive interactions between the carboxylate and active site residues through a highly organized water network.

Keywords: Dihydrofolate reductase, antifolate, MRSA, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, trimethoprim, methotrexate

The essential metabolic enzyme dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) has been a successfully and widely targeted protein for both oncology1 and infectious disease2 indications, delivering efficacious drugs such as methotrexate (MTX), pemetrexed (PMX), and trimethoprim (TMP). Its natural substrates, folic acid or dihydrofolate, possess a weakly basic pterin ring and a negatively charged glutamate extension that are critical for binding of the enzyme. Several crystal structures with different species of DHFR reveal that classical antifolates such as MTX (Figure 1) and PMX mimic these motifs of the substrate with a basic nitrogenous headgroup that forms strong contacts with an acidic residue in the active site and a glutamate tail that forms extensive ionic interactions with a basic amino acid (e.g., Arg 57 in S. aureus DHFR).3−5 As substrate mimics, classical antifolates often possess very high affinity for DHFR. For example, MTX inhibits human, Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus DHFR with Ki values of 3.4 pM, 1 pM, and 1 nM,6,7 respectively.

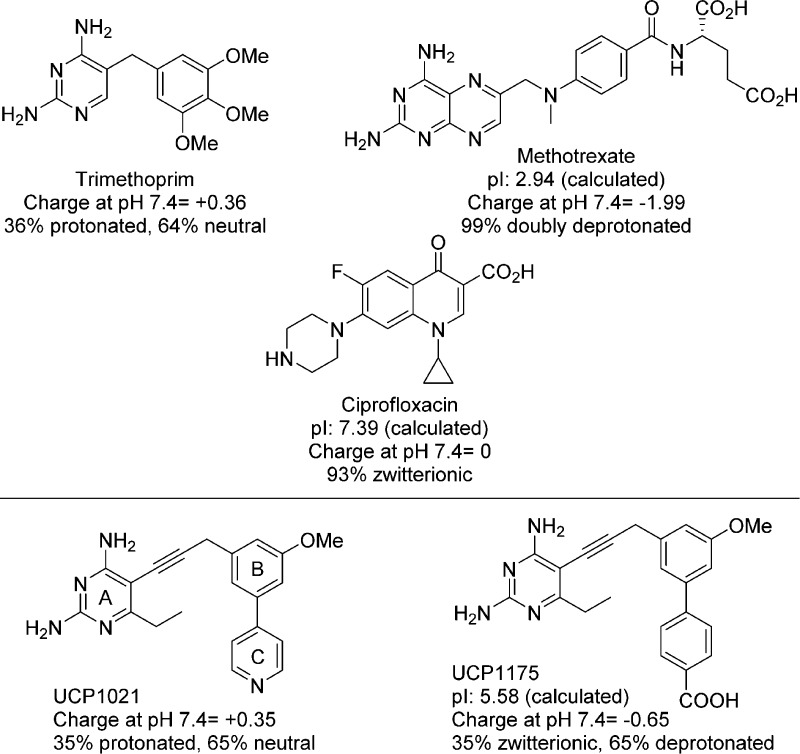

Figure 1.

Antibacterial agents effective against Gram-positive or Gram-negative bacteria with relevant physiological properties. A previous PLA (UCP10218) is compared to a PLA-COOH.

However, as these classical antifolates carry high negative charge at physiological pH, passive diffusion is limited and requires active transport through human cell membranes to obtain physiologically relevant concentrations. Currently, all approved anticancer DHFR inhibitors are categorized as classical antifolates. As bacteria rely on the de novo synthesis of folate cofactors, they do not possess folic acid transporters. Therefore, classical antifolates must enter bacteria by passive diffusion through the membrane to achieve antibacterial effects. Accordingly, the MIC value of the potent enzyme inhibitor MTX against wild-type Gram-negative E. coli is over 1 mM. Even when efflux pumps are genetically deleted, the MIC value is 64–256 μM,7 demonstrating that the compound has limited permeability and is subject to efflux. Similarly, against the Gram-positive methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), methotrexate has a MIC50 of 20 μg/mL or MIC90 of 100 μg/mL.9 In contrast, the weakly basic, nonclassical antifolate trimethoprim (Figure 1) with attenuated DHFR inhibition (IC50 values of 23 and 20 nM) is a potent antibacterial against both MRSA and E. coli (MIC values of 0.3125 μg/mL) and is a first-line agent with sulfamethoxazole against both Gram-negative and Gram-positive infections.10−13

The inclusion of two acidic functional groups in MTX results in a highly negatively charged population at physiological pH with a net −2 charge. However, it has been appreciated that zwitterionic compounds possessing only a single acidic functional group, such as fluoroquinolones (Figure 1) or tetracyclines, show utility against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. For example, ciprofloxacin exists almost exclusively as the neutral charge-balanced form. The zwitterionic character contributes to a lower clogD7.4 value (−1.35 for ciprofloxacin), which has been shown to correlate with activity in Gram-negative bacteria.14

We have been developing the class of propargyl-linked antifolates (PLAs) as inhibitors of DHFR for both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. The PLAs, like trimethoprim, are characterized as weakly basic nonclassical antifolates that passively diffuse through membranes and potently inhibit the DHFR enzyme,8,15,16 often inhibiting the growth of bacterial cells with submicromolar MIC values. We have achieved very potent MIC values against MRSA and Streptococcus pyogenes(8,15,17) and good inhibition of Klebsiella pneumoniae(16) with compounds similar to UCP1021 (Figure 1).

We considered a hybrid design that would allow us to capture contacts typically made by the negatively charged glutamate tail in folate, while increasing bacterial cell permeability. This design would center on replacing the pyridyl function of UCP1021 with a carboxylic acid. Replacing pyridine should also reduce a key metabolic liability (pyridyl N-oxide formation18) and cytochrome P450 inhibition. Using Marvin (ChemAxon, http://www.chemaxon.com), we calculated charges for the molecules in Figure 1 as well as designed PLAs. At neutral pH, the PLAs partition into two primary species: both are deprotonated at the carboxylate group. The pyrimidine ring is protonated in 35% of the species, forming a zwitterionic inhibitor species; the remainder possess a neutral pyrimidine ring, yielding a negatively charged molecule (−1). The C-ring carboxylic acid functionality (see Figure 1 for ring labels) is designed to form hydrogen bonds with a conserved basic residue (Arg 57 in SaDHFR or EcDHFR) in the active site, respectively. We synthesized eight PLA-COOHs with a C6-ethyl diaminopyrimidine ring, either unsubstituted or methyl-substituted at the propargylic position, and a biphenyl system with either 2′- or 3′-methoxy substituents. Any inhibitors synthesized with propargylic substitutions were prepared as enantiomerically pure entities.

Alternate t-butyl benzoates were coupled via Suzuki reaction to suitable B-ring partners to produce biphenyl aldehydes, 1a–d. The formyl group was elaborated through Wittig homologation and acetylene formation to produce terminal alkynes 2a–d, which were coupled with the diaminopyrimidine headgroup under Sonagashira conditions. We were pleased to observe that final deblocking of the t-butyl ester under strong acidic conditions proceeded smoothly and in good yield to deliver the unbranched inhibitors, 3a–d (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Unbranched and Asymmetric PLAs.

Reagents and conditions. Unbranched Synthesis: (a) Ar–B(OH)2 or Ar–Br, Pd(PPh3)4, Cs2CO3, dioxane/H2O, 90 °C; (b) methoxymethyl triphenylphosphonium chloride, NaOtBu, THF, 0 °C; (c) NaI, TMSCl, MeCN, −20 °C; (d) dimethyl(1-diazo-2-oxopropyl)phosphonate, K2CO3, MeOH; (e) iodoethyl diaminopyrimidine, Pd(PPh3)2Cl2, CuI, KOAc, DMF, 50 °C; (f) TFA, DCM. Asymmetric Synthesis: (a) PdCl2(PPh3)2, 4-methoxycarbonylphenylboronic acid, dioxane/H2O, 90 °C; (b) 10% Pd/C, Et3SiH, DCM; (c) nonaflyl fluoride, P1-t-Bu-tris(tetramethylene) phosphazene base, DMF, −15 °C to rt; (d) iodoethyl diaminopyrimidine, Pd(PPh3)2Cl2, CuI, KOAc, DMF, 50 °C; (e) LiOH, THF·H2O, 32 °C.

As initial biological evaluation revealed that the para substitution was superior, nonracemic, methyl-branched homologues of 3c and 3d were prepared using our previously reported method.15 Synthesis of PLA enantiomers began from the previously reported chiral thioesters (4–5R/S) that were coupled to 4-methylbenzoate boronic acid via Suzuki coupling. Similar to the earlier synthesis, methyl ester cleavage could be achieved as the last synthetic step, affording compounds 10–11R/S.

All eight compounds were evaluated for their inhibition (IC50 values) of the S. aureus (Sa), E. coli (Ec), and human (Hu) DHFR enzymes (Table 1). Structure–activity analysis of the placement of the carboxylic acid group showed that, while the ortho and meta placement yielded the greatest selectivity over the human enzyme, placement in the para position yields the highest affinity to the pathogenic enzymes. In SaDHFR, moving the carboxylate from para to meta or ortho results in a 5- and 12-fold loss in activity, respectively. Activity against EcDHFR decreases 6-fold when the carboxylic acid is moved from the para to meta position, but only 2.2-fold when moved to the ortho position.

Table 1. Charged PLA–COOH Structure and Biological Activity.

| compd | RP | R1 | R2 | Ar | Sa Ki (nM)a | Ec Ki (nM)a | Hu Ki (nM)a | S. aureus 43300 (μg/mL)b | E. coli 25922 (μg/mL)b | E. coli NR698 (μg/mL)b | IC50 MCF-10 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3a | H | OCH3 | H | o-COOH | 53. 47 | 2.12 | 2494.9 | >20 | >32 | 20 | NDc |

| 3b | H | OCH3 | H | m-COOH | 23.38 | 5.72 | 346.15 | 0.625 | >20 | 0.0391 | ND |

| 3c | H | OCH3 | H | p-COOH | 4.77 | 0.98 | 200.77 | 0.0195 | >20 | 0.0098 | >100 |

| 3d | H | H | OCH3 | p-COOH | 1.64 | 5.52 | 158.77 | 0.0195 | >20 | 0.0049 | >100 |

| 10S | S-CH3 | OCH3 | H | p-COOH | 5.51 | 1.93 | 376.62 | 0.625 | >20 | 0.0391 | >100 |

| 10R | R-CH3 | OCH3 | H | p-COOH | 32.17 | 3.14 | 451.15 | 0.0195 | 20 | 0.0012 | >100 |

| 11R | R-CH3 | H | OCH3 | p-COOH | 1.34 | 0.91 | 234.23 | 0.0098 | 10 | 0.0024 | >100 |

| 11S | S- CH3 | H | OCH3 | p-COOH | 2.09 | 1.806 | 388.62 | 0.0098 | 10 | 0.0024 | >100 |

| TMP | 3.43 | 0.22 | 45783.5 | 0.3125 | 0.3125 | 0.0098 | |||||

| MTX | >40 | >40 | 40 |

Further modifications were made to the para-COOH scaffold including methoxy substitution at the R2 position as well as hydrogen and enantiomerically specific methyl substitution at the RP position. Moving the methoxy from the R1 (3c) to the R2 (3d) position resulted in a 3-fold increase in SaDHFR activity, from 4.77 nM to 1.64 nM, respectively. The same change in methoxy position resulted in up to a 5.6-fold decrease in activity against the EcDHFR enzyme. The placement of the methoxy group had little effect on activity against HuDHFR.

Previous studies have shown the importance of evaluating enantiomerically pure PLAs as the methyl configuration is important not only for its noncovalent interactions but also for directing the binding position of the biaryl system and influencing the binding of alternative cofactor anomer.15 The S-enantiomer of 3c, inhibitor 10S, exhibits no significant change in IC50 value, unlike the R-enantiomer (10R) that has a 7-fold loss in activity. The 3′OMe R- and S- enantiomers, inhibitors 11R and 11S, maintain similar activity as their hydrogen-substituted counterpart (3d), with Ki values of 1.34, 2.09, and 1.64 nM, respectively.

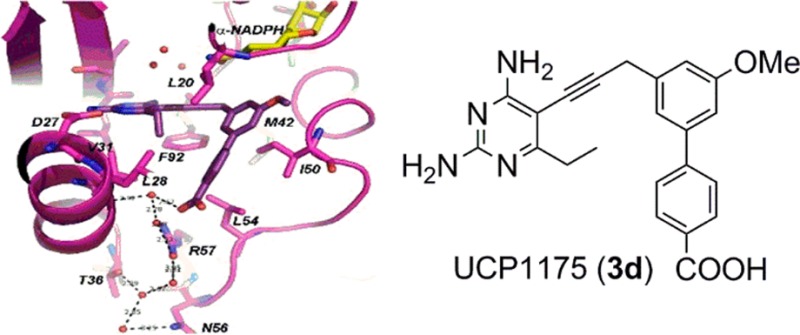

Structures of SaDHFR bound to the PLA-COOH compounds 3c and 3d were determined by X-ray crystallography in order to validate the design principles. Crystals of SaDHFR complexed with NADPH and inhibitor 3c or 3d produced diffraction amplitudes to 2.24 or 1.81 Å, respectively (diffraction data and model statistics shown in Table S3, omit map shown in Figure S1). The structures were solved using molecular replacement methods based on PDB 3F0Q(19) as a model. Both structures feature the bound antifolate and either dual occupancy of β-NADPH and its alternative α-anomer (structure with compound 3c shows the α-anomer in a ring-closed tautomer state20,21) or full occupancy of the α-anomer (structure with compound 3d). SaDHFR bound to 3c shows the coordination of a water molecule between the carboxylic acid and the side chain of Arg 57 (Figure 2a). SaDHFR bound to 3d exhibits an extensive water network involving at least four water molecules, coordinated between the carboxylic acid of 3d, both amino groups on Arg 57 as well as the carbonyl oxygen of Leu 28. The water network expands to include additional hydrogen bonding interactions with the side chains of Asn 56 and Thr 36 (Figure 2b). The binding modes of the inhibitor represent significant differences in the crystal structures with inhibitors 3c and 3d. The methoxy substitution in the R1 position of compound 3c shifts the biaryl system 1.2 Å toward the solvent exposed surface, which is likely responsible for differences in the observed water networks between compounds 3c and 3d (Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

Crystal structures of inhibitors 3c (PDB ID: 5HF0) and 3d (PDB ID: 5HF2) with SaDHFR and NADPH. (A) Compound 3c (dark green) and a mixture of β-NADPH (salmon) and α-NADPH (yellow) and SaDHFR (green). (B) Compound 3d (dark purple), α-NADPH, and SaDHFR (purple). (C) Overlay of compounds 3c and 3d. (D) β-NADPH and α-NADPH. Red spheres represent ordered water molecules observed in the structure.

PLA-COOH inhibitors exhibit high levels of activity against the SaDHFR enzyme as well as against S. aureus with the majority of MIC values ranging from 0.0098 to 0.625 μg/mL (Table 1). Furthermore, inhibitors 3d, 11R/S were shown to be bactericidal with minimum bactericidal concentrations (MBC) less than four times the MIC (Table S3).22 The compounds displayed reduced activity against wild-type E. coli, with compounds 11R and 11S exhibiting MIC values of 10 μg/mL. Two of the major barriers to activity against Gram-negative bacteria are permeability through the outer membrane and active removal of the inhibitor via efflux. MIC values were measured against NR698,23 an engineered E.coli strain containing an in-frame deletion in the imp gene, which encodes a protein essential for outer membrane assembly. This strain, with its compromised outer membrane, is used specifically to probe the role of compound permeability in antibacterial action.24 Inhibition concentrations against the NR698 strain with compounds 3a–d and 10–11R/S showed an approximately 2000–4000-fold decrease, indicating that reduced penetration through the outer membrane is limiting PLA activity in E. coli. Efflux activity is unlikely as MIC values were not shifted in ΔacrB, ΔmacB, ΔemrB, or ΔacrF strains (MIC values ΔacrB strain are shown in Supplemental Table S4, other data not shown). Similarly, MIC values were maintained between wild-type and porin knockout strains (ΔompF and ΔompC), validating that the compounds passively diffuse into the cells rather than gaining access through porins. MIC values for MTX for these strains were measured as ≥40 μg/mL, Table 1.

The extraordinary activity in the Gram-positive bacteria indicates that the design principles were successful, allowing the incorporation of negatively charged functionality to create key contacts with the enzyme without compromising cellular penetration, as with MTX. Alternatively in Gram-negative bacteria, the highly negative lipopolysaccharide barrier may mitigate the penetration of the negatively charged population of PLAs by electrostatic repulsion. This work motivates a further analysis of key physicochemical properties as outlined in Figure 1 to potentially reduce the population of negatively charged species to favor charge-neutral zwitterions and enhance Gram-negative penetration.

To examine the drug-like potential of the PLA-COOHs, a series of in vitro assays probed their effects on human cells, their inhibition of critical CYP isoforms, and their lifetime in microsomal stability assays. The PLA-COOHs have no measurable cytotoxicity toward mammalian cells at concentrations of at least 100 μM. For example, compound 3c has an IC50 value greater than 500 μM toward HepG2, MCF-10A, and human dermal fibroblast cells. Coupling the potent activity against Gram-positive bacterial cells with low cytotoxicity yields a high therapeutic index (>500,000). We have also been following cytochrome P450 inhibition for the PLA series and therefore measured the activity of compound 3c against CYP3A4 and CYP2D6, two of the most prevalent isoforms. Inhibition of both enzymes requires concentrations greater than 50 μM, indicating the compound may not interfere with the metabolism of other drugs. Finally, we tested the lifetime of compound 3c in microsomal stability assays. Compound half-life was measured by following the parent compound using UPLC. The phase I half-life is 99 min, and for phase II, approximately 87 min. The results of these in vitro experiments point toward an excellent drug-like profile for the PLA-COOHs.

In summary, this work presents a new series of hybrid antifolates that demonstrates how the incorporation of a carboxylate moiety to mimic one of the key interactions common to classical antifolates can be incorporated into the propargyl-linked antifolate architecture without compromising the ability to gain access to the target enzyme, DHFR. The preparation and evaluation of eight inhibitors shows that the compounds have high enzyme affinity and increased antibacterial activity against MRSA and E. coli relative to earlier PLAs. High resolution crystal structures of two compounds with S. aureus DHFR reveal that affinity is enhanced by water-mediated contacts between the carboxylate and Arg 57 in the active site. Additional profiling supports the development of these compounds as antibacterial candidates.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- DHFR

dihydrofolate reductase

- EcDHFR

E. coli DHFR

- HuDHFR

human DHFR

- IC50

inhibition concentration 50%

- MIC

minimum inhibition concentration

- MTX

methotrexate

- NADPH

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- PLA

propargyl-linked antifolate

- SaDHFR

S. aureus DHFR

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.6b00120.

Syntheses and characterization data for the reported compounds, including 1H, 13C NMR, and HRMS for all reported compounds, and HPLC purity analysis of tested final compounds. Biological evaluation error tables, diffraction data, and refinement statistics for crystal structures with SaDHFR:NADPH:3c or 3d. Bacteriostatic/bactericidal determination, table of MIC values for the ΔacrB strain, and omit maps (PDF)

Author Contributions

§ E.S. and S.M.R. contributed equally to this work. E.S. designed and synthesized the initial unbranched compounds and contributed to writing the manuscript. S.M.R. evaluated biological activity, determined crystal structures, and contributed to writing the manuscript. S.K. synthesized asymmetric compounds and edited the manuscript. M.N.L. and B.H. evaluated biological activity. A.E.S., J.B.A., and N.D.P. evaluated activity against mammalian cells. A.C.A. and D.L.W. conceived of and originated the project, directed studies, and wrote and edited the manuscript. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors thank the NIH for funding (AI104841 and AI111957 to A.C.A. and D.L.W.).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Hagner N.; Joerger M. Cancer chemotherapy: targeting folic acid synthesis. Cancer Manage. Res. 2010, 2, 293–301. 10.2147/CMAR.S10043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W.; Scocchera E.; Wright D.; Anderson A. Antifolates as effective antimicrobial agents: new generations of trimethoprim analogs. MedChemComm 2013, 4, 908–915. 10.1039/c3md00104k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett B.; Wan Q.; Ahmad M.; Langan P.; Dealwis C. X-ray structure of the ternary MTX.NADPH complex of the anthrax dihydrofolate reductase: a pharmacophore for dual-site inhibitor design. J. Struct. Biol. 2009, 166, 162–171. 10.1016/j.jsb.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawaya M.; Kraut J. Loop and subdomain movements in the mechanism of Escherichia coli dihydrofolate reductase: crystallographic evidence. Biochemistry 1997, 36, 586–603. 10.1021/bi962337c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R.; Sirawaraporn R.; Chitnumsub P.; Sirawaraporn W.; Wooden J.; Athappilly F.; Turley S.; Hol W. Three-dimensional structure of M. tuberculosis dihydrofolate reductase reveals opportunities for the design of novel tuberculosis drugs. J. Mol. Biol. 2000, 295, 307–323. 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchall J.; Hitchings G. Inhibitor Binding Analysis of Dihydrofolate Reductases from Various Species. Mol. Pharmacol. 1965, 1, 126–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopytek S.; Dyer J.; Knapp G.; Hu J. Resistance to methotrexate due to AcrAB-dependent export from Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 3210–3212. 10.1128/AAC.44.11.3210-3212.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan K.; Frey K.; Scocchera E.; Martin B.; Swain P.; Alverson J.; Priestley N.; Anderson A.; Wright D. Toward new Therapeutics for Skin and Soft Tissue Infections: Propargyl-linked Antifolates Are Potent Inhibitors of MRSA and Streptococcus pyogenes. PLoS One 2012, 7 (2), e29434. 10.1371/journal.pone.0029434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruszewska H.; Zareba T.; Tyski S. Antimicrobial activity of selected non-antibiotics - activity of methotrexate against Staphylococcus aureus strains. Acta Polym. Pharm. 2000, 57S, 117–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frei C.; Miller M.; Lewis J.; Lawson K.; Hunter J.; Oramasionwu C.; Talbert R. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or clindamycin for community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA) skin infections. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2010, 23, 714–719. 10.3122/jabfm.2010.06.090270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khawcharoenporn T.; Tice A. Empiric outpatient therapy with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, cephalexin, or clindamycin for cellulitis. Am. J. Med. 2010, 123, 942–950. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le J.; Lieberman J. Management of Community-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Infections in Children. Pharmacotherapy 2006, 26, 1758–1770. 10.1592/phco.26.12.1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood J.; Smith D.; Baker E.; Brecher S.; Gupta K. Has the emergence of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus increased trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole use and resistance?: a 10-year time series analysis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 5655–5660. 10.1128/AAC.01011-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea R.; Moser H. Physicochemical properties of antibacterial compounds: implications for drug discovery. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 2871–2878. 10.1021/jm700967e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshipeddy S.; Reeve S.; Anderson A.; Wright D. Nonracemic antifolates stereoselectively recruit alternate cofactors and overcome resistance in S. aureus. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 8983–8990. 10.1021/jacs.5b01442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb K.; Lombardo M.; Alverson J.; Priestley N.; Wright D.; Anderson A. Crystal structures of Klebsiella pneumoniae dihydrofolate reductase bound to propargyl-linked antifolates reveal features for potency and selectivity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 7484–7491. 10.1128/AAC.03555-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey K.; Viswanathan K.; Wright D.; Anderson A. Prospectively screening novel antibacterial inhibitors of dihydrofolate reductase for mutational resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 3556–3562. 10.1128/AAC.06263-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W.; Viswanathan K.; Hill D.; Anderson A.; Wright D. Acetylenic linkers in lead compounds: A study of the stability of the propargyl-linked antifolates. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2012, 40, 2002–2008. 10.1124/dmd.112.046870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey K.; Lombardo M.; Wright D.; Anderson A. Towards the Understanding of Resistance Mechanisms in Clinically Isolated Trimethoprim-resistant, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus Dihydrofolate Reductase. J. Struct. Biol. 2010, 170, 93–97. 10.1016/j.jsb.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox K.; Karplus A. Old yellow enzyme at 2A resolution: overall structure, ligand binding and comparison with related flavoproteins. Structure 1994, 2, 1089–1105. 10.1016/S0969-2126(94)00111-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer N. The primary acid product of DPNH. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1973, 50, 683–690. 10.1016/0006-291X(73)91298-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankey G.; Sabath L. Clinical Relevance of Bacteriostatic versus Bactericidal Mechanisms of Action its the Treatment of Gram-Positive Bacterial Infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004, 38, 864–870. 10.1086/381972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakeman D.; Sadeghi-Khomami A. A b-(1,2)-glycosynthase and an attempted selection method for the directed evolution of glycosynthases. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 10359–10366. 10.1021/bi201438q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz N.; Falcone B.; Kahne D.; Silhavy T. Chemical conditionality: a genetic strategy to probe organelle assembly. Cell 2005, 121, 307–317. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.