Abstract

Diverse somatic mutations have been reported to serve as cancer drivers. Recently, it has also been reported that epigenetic regulation is closely related to cancer development. However, the effect of epigenetic changes on cancer is still elusive. In this study, we analyzed DNA methylation data on colon cancer taken from The Caner Genome Atlas. We found that several promoters were significantly hypermethylated in colon cancer patients. Through clustering analysis of differentially methylated DNA regions, we were able to define subgroups of patients and observed clinical features associated with each subgroup. In addition, we analyzed the functional ontology of aberrantly methylated genes and identified the G-protein-coupled receptor signaling pathway as one of the major pathways affected epigenetically. In conclusion, our analysis shows the possibility of characterizing the clinical features of colon cancer subgroups based on DNA methylation patterns and provides lists of important genes and pathways possibly involved in colon cancer development.

Keywords: colon neoplasm, CpG islands, DNA methylation, epigenomics

Introduction

Generally, it is known that cancer is a result of somatic mutations in DNA. These mutations are located in genes that have important roles in regulating cell growth, cell differentiation, and DNA damage control [1,2]. Over the past decades, many cancer driver genes have been found by high-throughput sequencing technology, and thus, the number of cancer driver genes may have reached the limit [1,3]. Until now, many researchers have studied the mechanism of carcinogenesis and highlighted the biological role of driver mutations, such as TP53, PIK3CA, and KRAS [4]. However, in many types of cancers, the etiology of cancer cannot be explained only by DNA mutations. Researchers have found that epigenetic factors, such as DNA methylation and histone modification, also contribute to cancer formation and development [5]. Epigenetic factors are dynamic modifications that can change the state of gene expression or regulate expression rates. Some studies have shown that a large group of cancer patients have both globally low and high levels of DNA methylation (hypomethylation and hypermethylation, respectively) in specific promoter regions [6]. Based on analysis of DNA methylation data, they listed a few cancer-related genes that carry significant methylation changes as biomarkers [7]. However, the biological meaning of these markers is still not well known. Hence, in this study, we used colon cancer (COAD) datasets taken from The Caner Genome Atlas (TCGA) to observe a CG dense region called CpG islands (CGIs) that showed significant aberrations in DNA methylation and also analyzed changes in DNA methylation patterns to further understand the relationship between epigenetic changes and cancer mechanism.

Methods

TCGA COAD DNA methylation datasets and expression datasets

Both methylation and gene expression data were obtained from the TCGA Data Portal (https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/tcga/). We collected COAD Level 3 (pre-processed) JHU-USC HumanMethylation450 data for methylation and UNC illuminaHiSeq_RNASeqV2 data for gene expression. We neglected a normalization step for both datasets, since they were pre-processed and normalized by uploaded groups. We matched methylation and gene expression data by patient header ID using the TCGA barcode. Beta-value, a value of the ratio of the methylated probe intensity and the overall intensity, was used to represent the methylation percentage. Gene expression fold-change was calculated by taking scaled estimate values, multiplying by 106 (transcripts per million, TPM), adding 1 to each normal and tumor TPM, and then taking the log2 value of tumor and normal per gene.

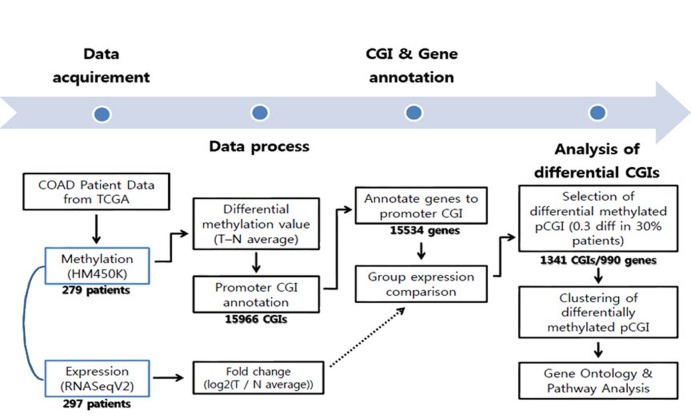

Differential methylation and expression analysis and clustering

To get differential DNA methylation values between normal tissue and tumor, we averaged all normal samples using annotated probes. For CGI analysis purposes, we intersected each beta-value for a total of 485,579 probes from the methylation data to the CGI location (provided by University of California Santa Cruz [UCSC]), averaged them using CGIs, and then subtracted the averaged DNA methylation value of normal samples from individual tumor samples. To focus on the effect of promoter CGIs, we selected CGIs that fell only into our defined promoter region, which covers the transcription start site ± 1 kb. Using this boundary, a total of 15,966 promoter CGIs were counted. The methylation distribution pattern of promoter CGIs was plotted by taking the mean promoter CGI methylation from the entire tumor and normal sample datasets. To get differentially methylated promoter CGIs, the averaged normal data were used as a reference, since there were no significant variations among normal samples. Differential patient data were calculated by subtracting this reference from each patient methylation data point (n = 297). In order to define the differential methylation cutoff, we referred to the methylation distribution pattern between normal samples and tumors. Methylated CGI annotated genes varied in their methylation percentage throughout the patients. Therefore, differentially methylated CGIs were identified as absolute difference of 0.3 in beta-values in at least 30% of total patients to obtain a broader range for gene selection (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Workflow of the COAD data analysis. CGI, CpG island; COAD, colon cancer; TCGA, The Caner Genome Atlas.

We grouped COAD patients by clustering their CGI differential methylation values using Cluster3.0 (http://bonsai.hgc.jp/~mdehoon/software/cluster/software.htm). We specifically used hierarchical clustering using the Euclidean distance similarity metric and the complete linkage clustering method, which grouped the patients the best. To reveal the direct methylation effect on gene expression, we selected an expression dataset that only matched with the methylation dataset, as well as a normal sample-tumor paired dataset (n = 26). We then aligned 26 paired patient data to the each group, divided by the CGI methylation clustering value. Expression level of patients in each group were averaged by genes and then plotted with mean values and 95% confidence levels.

Gene ontology analysis and pathway analysis

To gain a biological understanding from the selected genes, we carried out gene ontology analysis and pathway analysis using InnateDB [8]. A hypergeometric algorithm was selected, and Benjamini-Hochberg was used for the correction method. All three ontology results, including molecular function, cellular components, and biological process, were considered. Pathway results were also sourced from various databases, including Integrating Network Objects with Hierarchies (INOH), Reactome, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), Pathway Interaction Database (PID) NIC, and PID BioCarta. Significant Gene Ontology (GO) terms and pathways were selected based on p-value selection (p < 0.05). We combined functionally redundant GO terms, because genes that contained such ontologies were nearly identical. Pathways were sorted and grouped by their functional similarity of each pathway. From the many selected pathways, we focused on pathways that were previously found to be involved in tumorigenesis. G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling pathway-related genes were gathered from the InnateDB and KEGG pathways, and we indicated the hypermethylated genes involved in GPCR-related signaling.

Results

Cluster pattern of DNA methylation of promoter CGI and COAD patients

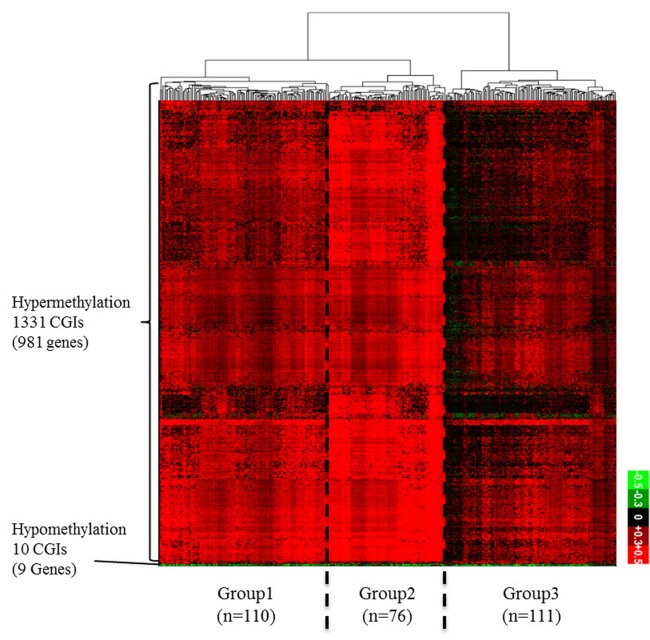

From the TCGA data portal, we collected array-based DNA methylation data of 279 patients. We then derived differential DNA methylation values between tumor and averaged normal samples. Differential methylation values of single-base probes were averaged by individual CGIs, and the data were filtered to indicate CGIs with significant changes in methylation as described in the "Methods" section (Fig. 1). We also checked the distribution of DNA methylation within promoter CGIs between normal and tumor samples by taking the mean of each condition per CGI. We observed that in general, promoter CGIs were hypermethylated in COAD patients in comparison to those in normal samples (Fig. 2A). We went on to group COAD patients based on their differential methylation status in promoter CGIs using clustering analysis. Since it is rare to see promoter CGIs being differentially methylated across an entire group of patients, clustering was focused on selecting CGIs, as well as identifying patient groups, based on their differential methylation patterns. From our results, we observed a greater number of hypermethylated CGIs than hypomethylated CGIs (Fig. 2B). As indicated by previous studies, COAD follows a common methylation pattern in cancer, which is hypermethylation of promoter CGIs [9]. We were also able to distinguish three distinctive clustered groups by their differential methylation patterns. Group 2 (n = 76) showed a much higher level of methylation within selected CGIs than groups 1 and 3. Group 1 showed intermediate differential methylation.

Fig. 2. (A) Differential DNA methylation pattern in promoter CpG islands (CGIs) between colon cancer (COAD) patients and normal. A distribution plot of mean beta-value between all tumor (red) and all normal (blue) samples. X-axis indicates beta-value ranging from 0 to 1. Y-axis indicates the density of accumulated beta-values. (B) Differential DNA methylation pattern in promoter CGIs between COAD patients and normal. A heatmap of clustered differentially methylated promoter CGIs. We defined promoter CGI that has ±0.3 differential beta-value in at least 30% patients as differentially methylated promoter CGIs. X-axis represents individual promoter CGIs (1,341 CGIs), and Y-axis represents each patient. (n = 297). Patients are divided based on hierarchical clustering using Euclidian distance similarity metric. Scale bar ranging from -0.5 to +0.5 tumor-normal beta-value.

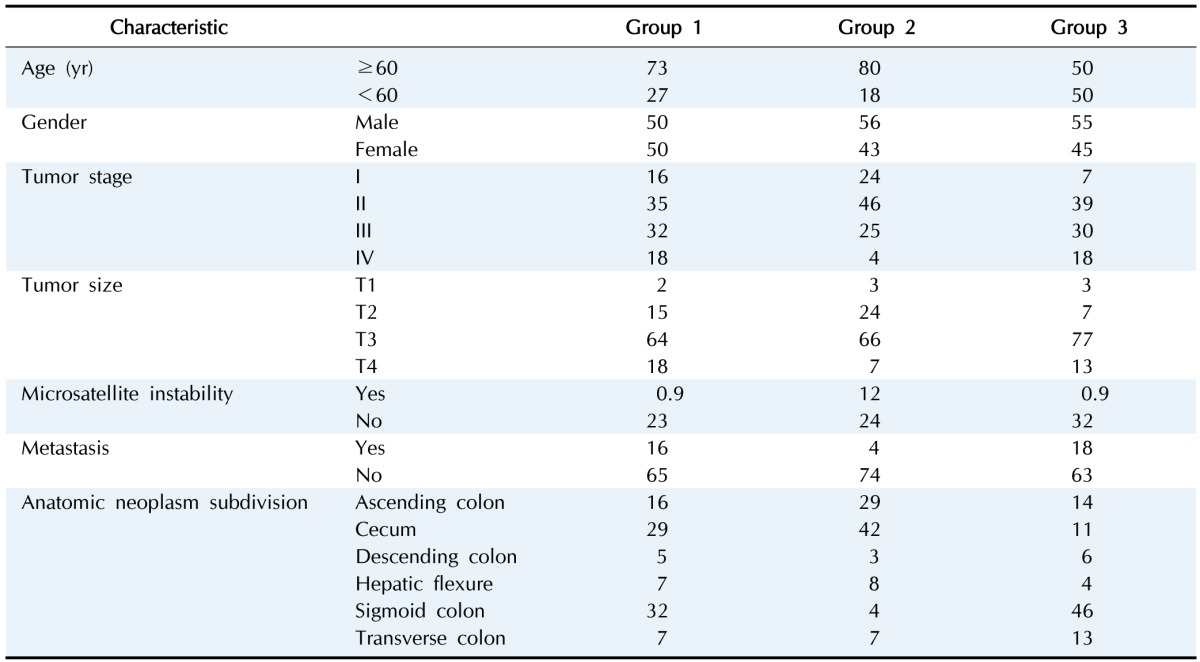

To find the meaning of each classified patient group, we investigated their respective clinical data (Table 1, Supplementary Table 1). When we analyzed the groups by clinical category, such as race, age, gender, and tumor stage, we could not find any discriminating factor among the three groups. However, we observed a distinct rate of metastasis in group 2, which showed the highest level of hypermethylation. At the same time, group 2 showed a higher rate of microsatellite instability (MSI). MSI is a hypermutable phenotype caused by impaired DNA mismatch repair. It is already known that MSI is associated with hypermethylation in the promoter region of the MLH1 gene [10]. Although the MLH1 gene was not detected in our filtered data, we surmised that the MSI phenotype in COAD patients can be affected by both DNA hypermethylation and MLH1 gene activity itself. Interestingly, the tumor sites differed among the three groups. In group 2, the cecum was the most frequent tumor site, while the sigmoid colon was the least frequent site in comparison with groups 1 and 3. These results provide a few insights about epigenetic mechanisms in COAD. First, the varying methylation patterns across COAD patient groups imply distinctive epigenetic cancer mechanisms pertaining to different patient groups. This could lead to subtyping COAD with varying promoter CGI methylation status, which can be utilized for treatment in patients. Second, hypermethylated promoter CGIs were enriched in differentially methylated region, which implies that the mechanism for COAD in promoter CGIs might be driven predominantly by methylating factors, such as DNA methyltransferases.

Table 1. Clinical data of three patient groups in colon cancer.

Values are presented as percentage.

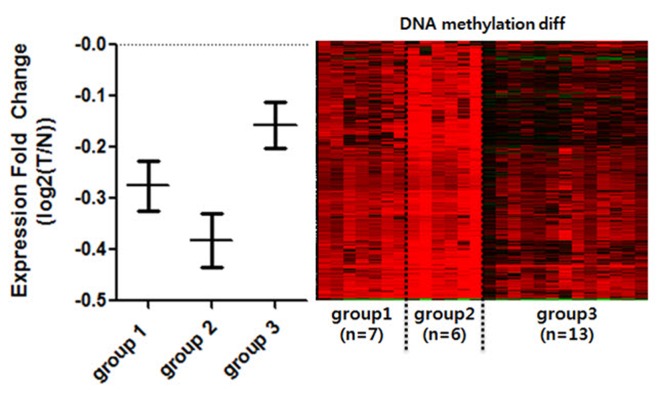

Downregulated gene expression in hypermethylated promoter CGI group

To see whether DNA methylation directly affects gene expression within selected CGIs, we annotated genes to promoter CGIs. For the sake of accuracy, we selected only gene expression datasets that matched the methylation data. We further selected datasets that had both normal and tumor samples from identical patients (n = 26). Since we expected different gene expression levels within the divided groups, we averaged the expression level of patients by each group. We then compared the mean values of promoter-overlapping genes between the groups to see the general expression level (Fig. 3). It is well known that the effect of promoter CGI methylation is repression of gene expression. We observed that group 2 experienced the highest repression of gene expression levels, thus reflecting the role of promoter CGI methylation as a gene-repressive marker. In comparison, we noted the highest overall gene expression levels in group 3. COAD patients in less hypermethylated groups, however, were less affected by hypermethylation in their promoter region. We noted that there were some patients in all groups whose gene expression was not affected by methylation. We assumed that there were not only epigenetic factors but many other varying factors among cancer patients that could result in regulation at individual genes. This DNA methylation change in promoter CGIs, which alters gene expression, is called epi-mutation [11]. Using this analogy, some patients were epi-mutated in aberrantly methylated promoter CGIs, while others were not affected significantly. In general, we were able to see that promoter CGI hypermethylation is mostly linked to the overall repression of gene expression, confirming the epi-mutation effect.

Fig. 3. Expression comparison among the groups of clustered hypermethylated promoter CpG islands (CGIs). Only the normal-tumor paired, and methylation-expression matched patients were selected for comparison of gene expression (n = 26). Patients were divided into the previously clustered groups by promoter CGI methylation. Expression fold change (Y-axis) was calculated by log2(T/N). Genes that overlap with hypermethylated promoter CGI were averaged by each patient and each group. Each bar represents standard error mean of each patient. Right panel is DNA methylation changing pattern of corresponding individual patients. T, tomor; N, normal.

Epi-mutated genes and pathways in COAD

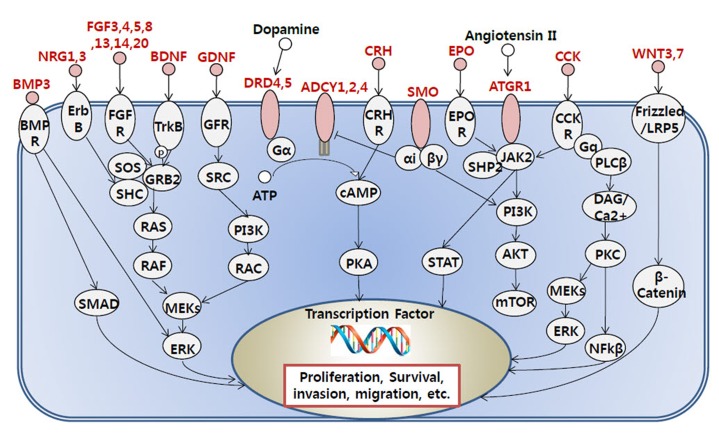

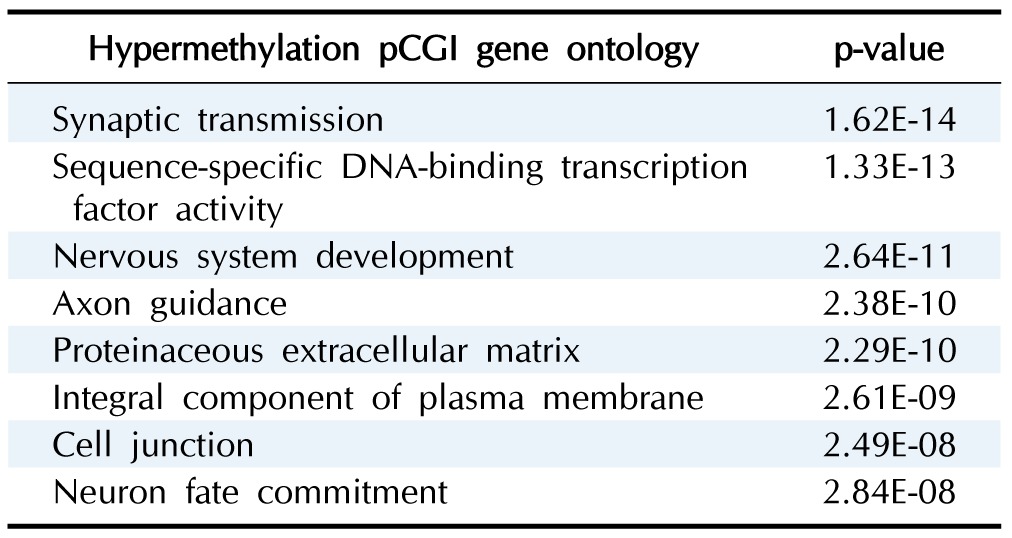

To see the biological function of hypermethylated promoter CGI genes, we performed gene ontology analysis [8]. Gene ontology analysis provides a functional interpretation of biological process, molecular function, and cellular component among selected genes. The ontology results included mainly neural development-related terms, such as synaptic transmission and nervous system development (Table 2). Interestingly, the gene ontology term of sequence-specific DNA-binding transcription factor activity was found. This implies that a large group of downstream genes that are targeted by the affected transcription factors could have a potential role in cancer initiation and development. Additionally, we carried out pathway analysis to further understand cancer-related biological processes affected by epi-mutated genes (Supplementary Table 2). In fact, many recent cancer-related pathways are found with mutations among patients, and this information is useful for functional studies of cancer mechanisms [2]. We attempted to provide an extended network that involves hypermethylated promoter CGI genes to expand our understanding of epi-mutational pathways in cancer. Selected pathways with p-value <0.05 include Wnt signaling, the RAS pathway, migration and invasion, extracellular matrix organization, and cell adhesion. These pathways are commonly related to cancer proliferation and metastasis [12]. In addition to the pathways previously mentioned, we found the following pathways to be distinctive to only hypermethylated promoter CGI genes in COAD: calcium signaling, ion channel, and GPCR signaling; especially interesting is the observation of hypermethylation in many ligands and receptors that are involved in GPCR signaling (Fig. 4) [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. This implies that epigenetic mechanisms play a role upstream of the pathway, regulating many downstream signaling pathways that are involved in cancer growth. Epi-mutated pathway analysis thus allows us to find additional cancer-related pathways that have not been previously highlighted by analyses based on somatic mutations. Overall, these results suggest the function of hypermethylation in promoter CGI genes in colon cancer as a driver of transcriptional regulation and developmental events and indicate that epi-mutated genes are involved in regulating various cancer-related pathways, like GPCR signaling, in favor of colon cancer development.

Table 2. Ontology analysis results from hypermethylated pCGI genes.

pCGI, promoter CpG island.

Fig. 4. Representation of G protein-coupled receptor related signaling pathway affected by the hypermethylated promoter CpG island (CGI) genes. Hypermethylated promoter CGI genes are marked as red.

Discussion

In contrast to somatic mutations, epigenetic changes are reversible phenomena. Using this property, epigenetic factors can be therapeutic targets of cancer treatments. Until now, DNA methylation inhibitors, such as azacitidine, have been used as one of many cancer drugs. However, this kind of drug is not able to specify the target molecule and shows differential drug effects in individual cancer patients. In this paper, we observed impaired DNA methylation in colon cancer patients—so-called epi-mutation [21]. We can confirm that DNA methylation aberrations in specific promoter regions were widely distributed in cancer patients and that patient groups can be divided by the extent of DNA methylation change. We expect that by introducing the epi-mutation concept, patients of a certain cancer type that is not explained by somatic mutations can be diagnosed more sensitively. Moreover, the subgroups of patients will provide a clue for the different drug effects between individual cancer patients. Further epi-mutation studies in each cancer type will define cancer-specific related biological pathways, and overall, these results will help us understand the cancer mechanisms and develop target-specific cancer drugs.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Global Research Laboratory Program of the National Research Foundation (NRF; grant No. NRF-2007-00013) and a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant No. HI14C1277).

Supplementary materials

Supplementary data including two tables can be found with this article online at http://www.genominfo.org/src/sm/gni-14-46-s001.pdf.

Clinical data of three patients groups in colon cancer

Pathway analysis result from hypermethylated promoter CGI genes

References

- 1.Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu VE, Zhou S, Diaz LA, Jr, Kinzler KW. Cancer genome landscapes. Science. 2013;339:1546–1558. doi: 10.1126/science.1235122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kan Z, Jaiswal BS, Stinson J, Janakiraman V, Bhatt D, Stern HM, et al. Diverse somatic mutation patterns and pathway alterations in human cancers. Nature. 2010;466:869–873. doi: 10.1038/nature09208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schweiger MR, Barmeyer C, Timmermann B. Genomics and epigenomics: new promises of personalized medicine for cancer patients. Brief Funct Genomics. 2013;12:411–421. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elt024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martincorena I, Campbell PJ. Somatic mutation in cancer and normal cells. Science. 2015;349:1483–1489. doi: 10.1126/science.aab4082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suvà ML, Riggi N, Bernstein BE. Epigenetic reprogramming in cancer. Science. 2013;339:1567–1570. doi: 10.1126/science.1230184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baylin SB. DNA methylation and gene silencing in cancer. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2005;2(Suppl 1):S4–S11. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim MS, Lee J, Sidransky D. DNA methylation markers in colorectal cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010;29:181–206. doi: 10.1007/s10555-010-9207-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breuer K, Foroushani AK, Laird MR, Chen C, Sribnaia A, Lo R, et al. InnateDB: systems biology of innate immunity and beyond: recent updates and continuing curation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D1228–D1233. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herman JG, Baylin SB. Gene silencing in cancer in association with promoter hypermethylation. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2042–2054. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra023075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boland CR, Goel A. Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2073–2087.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horsthemke B. Epimutations in human disease. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2006;310:45–59. doi: 10.1007/3-540-31181-5_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colussi D, Brandi G, Bazzoli F, Ricciardiello L. Molecular pathways involved in colorectal cancer: implications for disease behavior and prevention. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:16365–16385. doi: 10.3390/ijms140816365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuan W, López Bernal A. Cyclic AMP signalling pathways in the regulation of uterine relaxation. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2007;7(Suppl 1):S10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-7-S1-S10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ritter SL, Hall RA. Fine-tuning of GPCR activity by receptor-interacting proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:819–830. doi: 10.1038/nrm2803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agid Y, Buzsáki G, Diamond DM, Frackowiak R, Giedd J, Girault JA, et al. How can drug discovery for psychiatric disorders be improved? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:189–201. doi: 10.1038/nrd2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dufresne M, Seva C, Fourmy D. Cholecystokinin and gastrin receptors. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:805–847. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00014.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodchild RE, Grundmann K, Pisani A. New genetic insights highlight 'old' ideas on motor dysfunction in dystonia. Trends Neurosci. 2013;36:717–725. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ligeti E, Welti S, Scheffzek K. Inhibition and termination of physiological responses by GTPase activating proteins. Physiol Rev. 2012;92:237–272. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00045.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dorsam RT, Gutkind JS. G-protein-coupled receptors and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:79–94. doi: 10.1038/nrc2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Airaksinen MS, Saarma M. The GDNF family: signalling, biological functions and therapeutic value. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:383–394. doi: 10.1038/nrn812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hitchins MP. Constitutional epimutation as a mechanism for cancer causality and heritability? Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15:625–634. doi: 10.1038/nrc4001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Clinical data of three patients groups in colon cancer

Pathway analysis result from hypermethylated promoter CGI genes