Abstract

Osteoporosis is a medical condition of global concern, with increasing incidence in both sexes. Bone mineral density (BMD), a highly heritable trait, has been proven a useful diagnostic factor in predicting fracture. Because medical information is lacking about male osteoporotic genetics, we conducted a genome-wide association study of BMD in Korean men. With 1,176 participants, we analyzed 4,414,664 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) after genomic imputation, and identified five SNPs and three loci correlated with bone density and strength. Multivariate linear regression models were applied to adjust for age and body mass index interference. Rs17124500 (p = 6.42 × 10-7), rs34594869 (p = 6.53 × 10-7) and rs17124504 (p = 6.53 × 10-7) in 14q31.3 and rs140155614 (p = 8.64 × 10-7) in 15q25.1 were significantly associated with lumbar spine BMD (LS-BMD), while rs111822233 (p = 6.35 × 10-7) was linked with the femur total BMD (FT-BMD). Additionally, we analyzed the relationship between BMD and five genes previously identified in Korean men. Rs61382873 (p = 0.0009) in LRP5, rs9567003 (p = 0.0033) in TNFSF11 and rs9935828 (p = 0.0248) in FOXL1 were observed for LS-BMD. Furthermore, rs33997547 (p = 0.0057) in ZBTB and rs1664496 (p = 0.0012) in MEF2C were found to influence FT-BMD and rs61769193 (p = 0.0114) in ZBTB to influence femur neck BMD. We identified five SNPs and three genomic regions, associated with BMD. The significance of our results lies in the discovery of new loci, while also affirming a previously significant locus, as potential osteoporotic factors in the Korean male population.

Keywords: bone density, genome-wide association study, Koreans, men, single nucleotide polymorphisms

Introduction

Osteoporosis is defined as a chronic condition that is characterized by low bone mass and the micro-architectural deterioration of osseous tissue, leading to fragility. Bone mineral density (BMD) has been established as the most significant diagnostic factor for osteoporotic fracture [1,2].

Although more widespread in women, about 1.5 million males over the age of 65 have osteoporosis and another 3.5 million are at risk in the United States [3]. Among Korean men, the prevalence of the condition has also increased by about 7.5%, according to national health survey data [4]. Major risk factors of male osteoporosis are aging and lifestyle choices, such as smoking, alcohol, and lack of exercise [5,6,7]. Genetic factors may also play a significant role, because BMD has been observed to have similar heritability patterns in both men and women [8]. Thought to be heritable, BMD is 78% in the lumbar spine and 84% in the femoral neck [9]. Up to 100 genes, associated with BMD, have been identified to date by various genetic studies [10,11]. One current meta-analysis identified 56 loci including 32 new regions associated with BMD with highly significant level [12]. The study had demonstrated several genetic loci such as myocyte enhancer factor 2C (MEF2C), zinc finger- and BTB-domain containing 40 (ZBTB40), low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5), and forkhead box L1 (FOXL1) which have been significantly replicated in Korean population in later studies [13,14].

However, the influence of sex-specific genes remains unclear, because most of the research has been conducted on highly homogeneous population samples, mostly European post-menopausal women [11]. Several investigations of genetic components in male osteoporosis are available, but they rely on candidate data or produced no significant results [15]. Moreover, cases of East Asian populations as the participating demographic are largely absent from the literature or consist of replications and attempts to confirm results already derived from Caucasian samples [13,14,16]. A recent study of a Korean group was able to newly identify several polymorphic factors, but unfortunately, it utilized BMD from the radius and tibia, which is less important in the development of bone deterioration than that of the lumbar spine and hip bone [17]. Investigating the etiology behind osteoporosis in males of East Asian descent is of high diagnostic and clinical importance. Therefore, our study aimed to evaluate the role of genetic polymorphisms in forming the BMD at the lumbar spine and femur bone in Korean men.

Methods

Study populations

We selected non-osteoporotic participants who were tested via dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry from the Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention of Seoul National University Hospital and the Gangnam Center for Health Promotion. The subjects underwent regular health check-ups from May 2009 to December 2013. Our sample consisted exclusively of Korean men aged between 20 and 60 years. This initial step of the procedure was performed to detect genetic defects associated with obesity and metabolic syndrome [18,19]. Those with conditions that could affect body weight were excluded from the study. We also excluded individuals who had taken any medication that might influence BMD, such as bisphosphonate, within the last 3 months or had a history of surgery or foreign body insertion at the spine or femur. After applying the above criteria, 1,192 subjects were selected. After excluding 16 participants who were related to each other, our final sample consisted of 1,176 individuals.

Phenotype measurement

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (Prodigy Advance; General Electric Company, Fairfield, CT, USA) measurements at the lumbar spine and femur were obtained from all patients, following standard protocols. We distinguished and analyzed three BMD phenotypes—lumbar spine (L1-L4) (LS-BMD), femur neck (FN-BMD), and femur total (FT-BMD)—identified here as the average value of mineral density at the neck and greater trochanter of the femur bone.

Genotyping and quality control

All participants underwent a microarray assay, using the Illunina HumanCore BeadChip kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). We filtered out poor quality single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and samples, which were defined as SNPs with a monographic genotype, a Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium p < 10-6, a call rate <95%, and a minor allele frequency <1%. After quality control, the remaining 264,283 SNPs were used in subsequent analysis.

Genotype imputation

All missing genotypes were imputed in order to examine any potential effect of the unmeasured variants. We used 1,000 Genomes ASN Phase I integrated variant set release (v3) in National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) build 37 (hg19) as a reference panel, along with PLINK software (version 1.07) [20] for strand alignment, SHAPEIT2 [21] for phasing, and IMPUTE2 [22] for the imputation procedure. Only variants with Info Score ≥0.9 were included in the final count, resulting in a total of 4,414,664 SNPs, which were either genotyped or imputed with high confidence.

Statistical analyses

Multivariate linear regressions, adjusted for the effects of age and body mass index (BMI, weight/height2, kg/m2) [23] via an additive model, were used to further investigate the influence of SNPs on BMD. Genome-wide association patterns were analyzed by the PLINK software package version 1.07 [20], while quantile-quantile and Manhattan plots were obtained by R software 3.2.2 (2015 The R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Regional association plots of the significant SNPs were generated by LocusZoom software [24]. All results with p < 1 × 10-6 were considered statistically significant.

Association with previously identified loci

We attempted to determine similarities between our selected markers and five other genes, which have previously been identified as indicative of osteoporosis in Korean male populations. Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 11 (TNFSF11) on 13q14, FOXL1 on 16q24, LRP5 on 11q13.4, ZBTB40 on 1q31.3, and MEF2C on 5q14 have been connected to BMD in several different genome-wide association studies (GWASs)—an association confirmed in Korean males by a number of replication studies [13,14]. We examined the most significant SNP regions of these five genes by applying our markers and considering only results with a p < 0.05.

Ethics statement

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Seoul National University Hospital (IRB No. H-0911-010-299) and all participants provided written informed consent.

Results

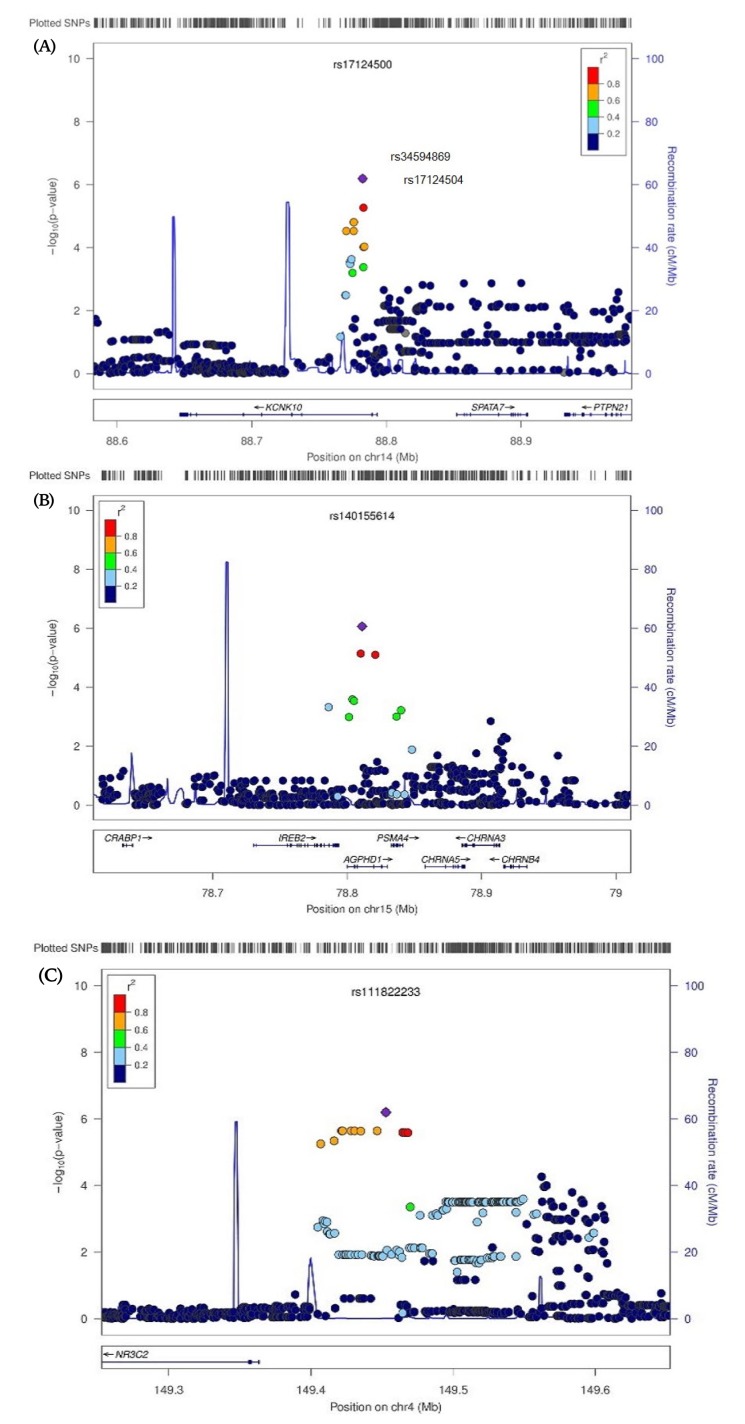

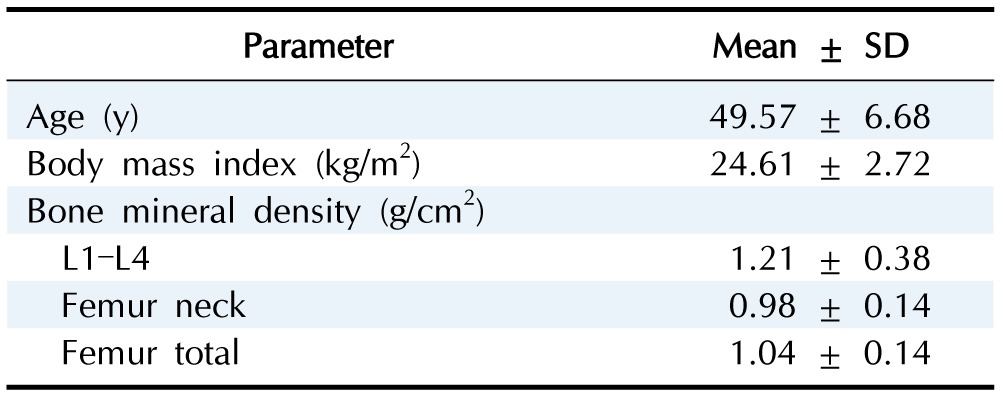

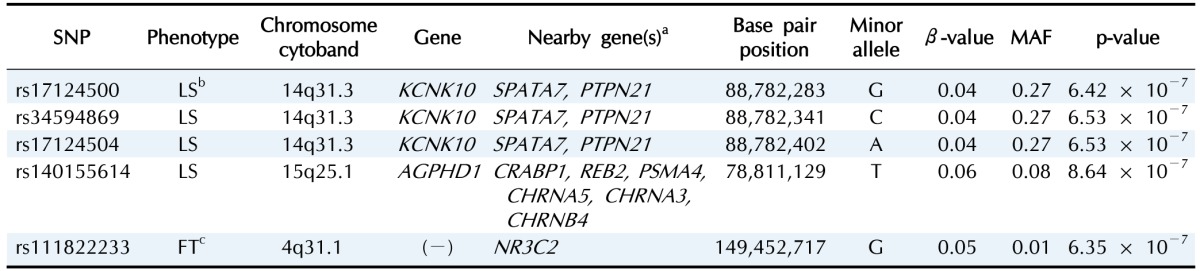

The mean age of the study subjects was 49.57 years, with BMI values between 16.58 kg/m2 and 37.27 kg/m2. We examined distribution patterns of three BMD phenotypes: LS-BMD, FN-BMD, and FT-BMD. LS-BMD ranged between 0.78 g/cm2 and 1.84 g/cm2 (mean ± SD, 1.21 ± 0.38 g/cm2), FN-BMD ranged between 0.64 g/cm2 and 1.93 g/cm2 (mean ± SD, 0.98 ± 0.14 g/cm2), and FT-BMD ranged between 0.29 g/cm2 and 1.93 g/cm2 (mean ± SD, 1.04 ± 0.14 g/cm2) (Table 1). We identified five SNPs with a significant influence on BMD. Rs17124500 (p = 6.42 × 10-7), rs34594869 (p = 6.53 × 10-7), rs17124504 (p = 6.53 × 10-7), and rs140155614 (p = 8.64 × 10-7) were significantly associated with LS-BMD, and rs111822233 (p = 6.35 × 10-7) was associated with FT-BMD (Table 2). Fig. 1 illustrates regional plots of the five significant SNPs within 200 kilobytes. No genomic association between FN-BMD and any polymorphic nucleotides was established. Quantile–quantile and Manhattan plots of the p-values are shown in Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of study subjects.

Table 2. Summary of 5 SNPs significantly associated with bone mineral density at lumbar spine and femur.

SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; MAF, minor allele frequency.

aGenes located within 200 KB of the SNPs; bBone mineral density at lumbar spine; cBone mineral density of femur total.

Fig. 1. Regional plots of genome wide significant associations for bone mineral density (BMD), adjusted for age and body mass index. (A) Regional plot of significant associated single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with BMD at lumbar spine in chromosome 14. (B) Regional plot of significant associated SNPs with BMD at lumbar spine in chromosome 15. (C) Regional plot of significant associated SNPs with BMD at femur total in chromosome 4.

Examination of genomic location revealed that rs17124500, which was the polymorphic nucleotide most closely associated with LS-BMD, is generally detected in potassium channel, subfamily K, member 1 (KCNK10) in 14q31.3 (Fig. 1A). Rs34594869 and rs17124504, were observed upstream of regions with high linkage disequilibrium constants, defined here as D' >0.8. Rs140155614 was most prominent in the aminoglycoside phosphotransferase domain containing 1 (AGPHD1) locus 15q25.1 (Fig. 1B). All four of these SNPs occurred as intron variants. rs111822233, the only sequence to influence the mineral density of the femur total, was positioned around the nuclear receptor subfamily 3, group C, member 2 (NR3C2) in 4q31.1 (Fig. 1C). The function of this SNP is currently undetermined.

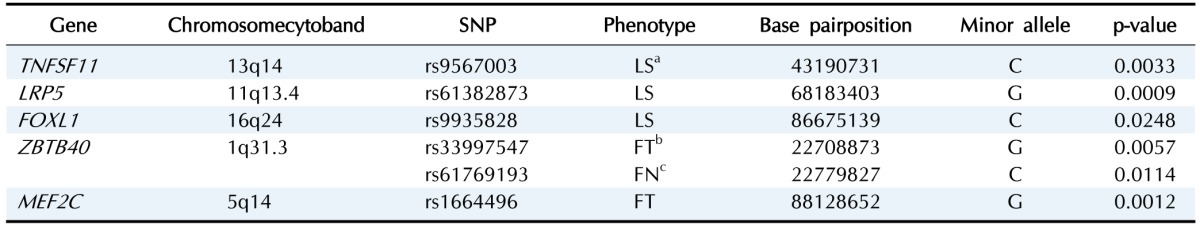

In addition to establishing links between genetic polymorphisms and BMD, our studies aimed to identify loci previously confirmed as osteoporosis factors in Korean male populations in order to verify our outcomes (Table 3). Rs61382873 in LRP5 exhibited the highest association with LS-BMD (p = 0.0009). Rs9567003 (p = 0.0033) in TNFSF11 and rs9935828 (p = 0.0248) in FOXL1 were also linked to the lumbar spine region, albeit with higher p-values. Patterns of rs33997547 (p = 0.0057) in ZBTB and rs1664496 (p = 0.0012) in MEF2C were correlated with FT-BMD, while rs61769193 (p = 0.0114) in ZBTB was found to influence FN-BMD.

Table 3. Summary of the association with previously identified gene in Korean men.

SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; TNFSF11, tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 11; LRP5, low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5; FOXL1, forkhead box L1; ZBTB40, zinc finger- and BTB-domain containing 40; MEfC, myocyte enhancer factor 2C.

aBone mineral density at lumbar spine; bBone mineral density at femur total; cBone mineral density at femur neck.

Discussion

We identified five SNPs and three genomic regions, associated with BMD. Four of these SNPs (rs17124500, rs34594869, rs17124504, and rs140155614) were linked with LS-BMD and dispersed between two loci (14q31.1 and 15q25.1). One SNP (rs111822233) found in 4q31.1 was exclusively associated with FT-BMD. We also re-evaluated three previously established genetic relationships. First, we confirmed the connection between LS-BMD and the following loci: rs61382873 in LRP5, rs9567003 in TNFSF11, and rs9935828 in FOXL1. Next, we linked rs33997547 in ZBTB40 and rs1664496 in MEF2C with FT-BMD and analyzed rs61769193 expression patterns in FN-BMD.

Three of our significant markers—rs17124500, rs34594869, and rs17124504—were located on the KCNK10 gene. This channel protein, embedded in the cellular membrane, consists of two pore-forming P domains and regulates K+ concentration. The role of potassium ions in maintaining the acid-base homeostasis of most organs and tissues, including bones, has been well established in the literature [25]. Additionally, KCNK10 is located on 14q31, a locus previously associated with LS-BMD in linkage analyses [26]. Although the relationship between the gene and osseous metabolism is not clear, it is highly possible that its translational mechanisms influence bone biological parameters.

rs140155614 was prominent in the AGPHD1 domain. Alternatively known as hydroxylysine kinase (HYKK), this protein-coding gene and its associated pathway, catalyze the GTP-dependent phosphorylation of 5-hydroxy-L-lysine. Located on 15q25.1, it has a well-known connection to the development of lung cancer. CHRNA3-CHRNA5-CHRNB4, a gene complex near AGPHD1, has been linked to nicotine dependence in several genetic studies [27]. Current scientific evidence is insufficient in determining the role of this locus in BMD development 's replication patterns is needed to validate or dispute a relationship with BMD.

rs111822233 was the only genetic marker with a direct relationship to FT-BMD levels. Located on 4q31.1, it is near NR3C2, a nuclear receptor involved in steroid signaling and regulation. Mineralocorticoid and various sex hormones, such as testosterone and estradiol, alternatively bind to the protein, which influences their secretion via a feedback loop [28]. Bone resorption has been reported to increase with the withdrawal of these sex hormones. Although estrogen is the major steroid in regulating ossein metabolism, testosterone is also important in the resorption mechanism [29]. Moreover, prevalence of osteoporosis in the hipbone has been shown to increase in men whose testosterone levels are lower than the reference range [30].

As established in our introduction, research conducted with Korean participants tends to be inconclusive owing to extensive focus on replication of results obtained by the original GWASs. Thus, we attempted to bridge this gap in information by validating previously established genetic linkages in Caucasian populations, whose significance has been confirmed in Korean men by replication studies [13,14]. LRP5, MEF2C, and ZBTB40 belong to the Wnt signaling pathway, which is largely related to cellular development and growth. Several studies have observed a link between this cascade and BMD [31]. We utilized a series of SNP markers from various Wnt-associated genes and were able to prove as association between rs61382873 in LRP5 and LS-BMD, between rs33997547 in ZBTB40 and rs1664496 in MEF2C and FT-BMD, and between rs61769193 in ZBTB40 and FN-BMD. TNFSF11, also known as receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL) plays a critical role in adequate bone metabolism via activation of osteoclast cells to regulate resorption [31]. We identified a significant SNP marker in TNFSF11, rs9567003, which was related to LS-BMD. Our results were consistent with those of a previous genetic research, which has established a connection between TNFSF11 and BMD of the lumbar spinal cord [31]. FOXL1 was originally identified by Genetic Factors for Osteoporosis (GEFOS) and has been associated with LS-BMD in European sample groups; this result has been replicated with high significance in Korean populations [13]. Our marker in FOXL1, rs9935828, was also correlated with LS-BMD levels. In conclusion, we described a series of new loci and confirmed GWAS results in Korean male populations by working with skeletal-specific BMD and gene associations.

There were several limitations to our study. First, no replications were performed to validate our results. Because indicators for measuring BMD in men tend to be narrow, recruiting a sufficient replication sample proved challenging. Thus, we aimed to use previously identified genetic markers, which have been established as valid in our selected ethnicity and gender. Despite our efforts, BMD is a less meaningful factor of osteoporosis in men than in women. Additionally, we could not consider all factors, including sex, age, weight, and menopausal status, owing to using only young men as our test subjects. Finally, we needed a very large sample because phenotypic variations are hard to detect in homogenous populations. However, our sample size was too small to employ a Bonferroni correction, and we were forced to set the significant threshold as p < 1 × 10-6, thus increasing the chance of false-positives. To minimize statistical error, we thoroughly analyzed gene functions and mechanisms. Nevertheless, further research is necessary to validate our findings.

In conclusion, our study identified novel loci correlated with BMD at 14q31.3, 15q25.1, and 4q31.1 in Korean men. Future studies should investigate these associations and the underlying genetic mechanisms.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary data including two figures can be found with this article online at http://www.genominfo.org/src/sm/gni-14-62-s001.pdf.

Quantile-quantile plots. (A) Quantile-quantile plot of p-values of bone mineral density (BMD) at the lumbar spine. (B) Quantile-quantile plot of pvalues of BMD at femur total.

Manhattan plots. (A)Manhattan plot of bone mineral density (BMD) at the lumbar spine. (B) Manhattan plot of BMD at femur total.

References

- 1.Johnell O, Kanis JA, Oden A, Johansson H, De Laet C, Delmas P, et al. Predictive value of BMD for hip and other fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:1185–1194. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O, Johansson H, De Laet C, Brown J, et al. The use of clinical risk factors enhances the performance of BMD in the prediction of hip and osteoporotic fractures in men and women. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:1033–1046. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0343-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siddiqui NA, Shetty KR, Duthie EH., Jr Osteoporosis in older men: discovering when and how to treat it. Geriatrics. 1999;54:20–22. 27–28, 30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi YJ, Oh HJ, Kim DJ, Lee Y, Chung YS. The prevalence of osteoporosis in Korean adults aged 50 years or older and the higher diagnosis rates in women who were beneficiaries of a national screening program: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2008-2009. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:1879–1886. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orwoll ES, Klein RF. Osteoporosis in men. Endocr Rev. 1995;16:87–116. doi: 10.1210/edrv-16-1-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drake MT, Murad MH, Mauck KF, Lane MA, Undavalli C, Elraiyah T, et al. Clinical review. Risk factors for low bone mass-related fractures in men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:1861–1870. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-3058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jutberger H, Lorentzon M, Barrett-Connor E, Johansson H, Kanis JA, Ljunggren O, et al. Smoking predicts incident fractures in elderly men: Mr OS Sweden. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:1010–1016. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.091112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peacock M, Turner CH, Econs MJ, Foroud T. Genetics of osteoporosis. Endocr Rev. 2002;23:303–326. doi: 10.1210/edrv.23.3.0464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arden NK, Baker J, Hogg C, Baan K, Spector TD. The heritability of bone mineral density, ultrasound of the calcaneus and hip axis length: a study of postmenopausal twins. J Bone Miner Res. 1996;11:530–534. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650110414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mo XB, Lu X, Zhang YH, Zhang ZL, Deng FY, Lei SF. Genebased association analysis identified novel genes associated with bone mineral density. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0121811. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Urano T, Inoue S. Recent genetic discoveries in osteoporosis, sarcopenia and obesity. Endocr J. 2015;62:475–484. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.EJ15-0154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Estrada K, Styrkarsdottir U, Evangelou E, Hsu YH, Duncan EL, Ntzani EE, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies 56 bone mineral density loci and reveals 14 loci associated with risk of fracture. Nat Genet. 2012;44:491–501. doi: 10.1038/ng.2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim YA, Choi HJ, Lee JY, Han BG, Shin CS, Cho NH. Replication of Caucasian loci associated with bone mineral density in Koreans. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24:2603–2610. doi: 10.1007/s00198-013-2354-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park SE, Oh KW, Lee WY, Baek KH, Yoon KH, Son HY, et al. Association of osteoporosis susceptibility genes with bone mineral density and bone metabolism related markers in Koreans: the Chungju Metabolic Disease Cohort (CMC) study. Endocr J. 2014;61:1069–1078. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.ej14-0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roshandel D, Thomson W, Pye SR, Boonen S, Borghs H, Vanderschueren D, et al. A validation of the first genome-wide association study of calcaneus ultrasound parameters in the European Male Ageing Study. BMC Med Genet. 2011;12:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-12-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Styrkarsdottir U, Halldorsson BV, Gudbjartsson DF, Tang NL, Koh JM, Xiao SM, et al. European bone mineral density loci are also associated with BMD in East-Asian populations. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho YS, Go MJ, Kim YJ, Heo JY, Oh JH, Ban HJ, et al. A large-scale genome-wide association study of Asian populations uncovers genetic factors influencing eight quantitative traits. Nat Genet. 2009;41:527–534. doi: 10.1038/ng.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim HJ, Park JH, Lee S, Son HY, Hwang J, Chae J, et al. A common variant of NGEF is associated with abdominal visceral fat in Korean men. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0137564. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Son KY, Son HY, Chae J, Hwang J, Jang S, Yun JM, et al. Genetic association of APOA5 and APOE with metabolic syndrome and their interaction with health-related behavior in Korean men. Lipids Health Dis. 2015;14:105. doi: 10.1186/s12944-015-0111-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delaneau O, Marchini J 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. Integrating sequence and array data to create an improved 1000 Genomes Project haplotype reference panel. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3934. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Howie B, Fuchsberger C, Stephens M, Marchini J, Abecasis GR. Fast and accurate genotype imputation in genome-wide association studies through pre-phasing. Nat Genet. 2012;44:955–959. doi: 10.1038/ng.2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Felson DT, Zhang Y, Hannan MT, Anderson JJ. Effects of weight and body mass index on bone mineral density in men and women: the Framingham study. J Bone Miner Res. 1993;8:567–573. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650080507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pruim RJ, Welch RP, Sanna S, Teslovich TM, Chines PS, Gliedt TP, et al. LocusZoom: regional visualization of genome-wide association scan results. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2336–2337. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bushinsky DA. Acidosis and bone. Miner Electrolyte Metab. 1994;20:40–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ralston SH, Galwey N, MacKay I, Albagha OM, Cardon L, Compston JE, et al. Loci for regulation of bone mineral density in men and women identified by genome wide linkage scan: the FAMOS study. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:943–951. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amos CI, Wu X, Broderick P, Gorlov IP, Gu J, Eisen T, et al. Genome-wide association scan of tag SNPs identifies a susceptibility locus for lung cancer at 15q25.1. Nat Genet. 2008;40:616–622. doi: 10.1038/ng.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takeda AN, Pinon GM, Bens M, Fagart J, Rafestin-Oblin ME, Vandewalle A. The synthetic androgen methyltrienolone (r1881) acts as a potent antagonist of the mineralocorticoid receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:473–482. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.031112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Falahati-Nini A, Riggs BL, Atkinson EJ, O'Fallon WM, Eastell R, Khosla S. Relative contributions of testosterone and estrogen in regulating bone resorption and formation in normal elderly men. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:1553–1560. doi: 10.1172/JCI10942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fink HA, Ewing SK, Ensrud KE, Barrett-Connor E, Taylor BC, Cauley JA, et al. Association of testosterone and estradiol deficiency with osteoporosis and rapid bone loss in older men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:3908–3915. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thakker RV, Whyte MP, Eisman JA, Igarashi T. Genetics of Bone Biology and Skeletal Disease. San Diego: Academic Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Quantile-quantile plots. (A) Quantile-quantile plot of p-values of bone mineral density (BMD) at the lumbar spine. (B) Quantile-quantile plot of pvalues of BMD at femur total.

Manhattan plots. (A)Manhattan plot of bone mineral density (BMD) at the lumbar spine. (B) Manhattan plot of BMD at femur total.