Abstract

Ureaplasma urealyticum and Ureaplasma parvum are pathogens involved in urogenital tract and intrauterine infections and also in systemic diseases in newborns and immunosuppressed patients. There is limited information on the antimicrobial susceptibility and clonality of these species. In this study, we report the susceptibility of 250 contemporary isolates of Ureaplasma (202 U. parvum and 48 U. urealyticum isolates) recovered at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN. MICs of doxycycline, azithromycin, ciprofloxacin, tetracycline, erythromycin, and levofloxacin were determined by broth microdilution, with MICS of the last three interpreted according to CLSI guidelines. Levofloxacin resistance was found in 6.4% and 5.2% of U. parvum and U. urealyticum isolates, respectively, while 27.2% and 68.8% of isolates, respectively, showed ciprofloxacin MICs of ≥4 μg/ml. The resistance mechanism of levofloxacin-resistant isolates was due to mutations in parC, with the Ser83Leu substitution being most frequent, followed by Glu87Lys. No macrolide resistance was found among the 250 isolates studied; a single U. parvum isolate was tetracycline resistant. tet(M) was found in 10 U. parvum isolates, including the single tetracycline-resistant isolate, as well as in 9 isolates which had low tetracycline and doxycycline MICs. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) performed on a selection of 46 isolates showed high diversity within the clinical Ureaplasma isolates studied, regardless of antimicrobial susceptibility. The present work extends previous knowledge regarding susceptibility to antimicrobial agents, resistance mechanisms, and clonality of Ureaplasma species in the United States.

INTRODUCTION

Ureaplasmas are bacteria belonging to the class Mollicutes. They are small, self-replicating organisms, capable of cell-free existence (1). Their small genomes and limited biosynthetic abilities are responsible for many of their biological characteristics and requirements for complex growth media for cultivation in vitro (1). Ureaplasmas of medical importance are subclassified into two distinct species, Ureaplasma parvum and Ureaplasma urealyticum; the former is more frequently recovered than the latter (1).

U. urealyticum and U. parvum are part of the human microbiota but are also involved in urogenital tract infection and associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes and bacteremia alongside complications such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia and meningitis in newborns (1–5). Recently, Ureaplasma species have been associated with fatal hyperammonemia among lung transplant patients (6). Furthermore, some authors suggest that Ureaplasma infections may be involved in other unexplained hyperammonemia syndromes (7).

Antimicrobial options for treating Ureaplasma infections are limited. Since this genus lacks peptidoglycan, ureaplasmas are not affected by β-lactams or other antimicrobial agents acting on this target. Moreover, they are not susceptible to sulfonamides or trimethoprim since they do not synthesize folic acid. However, members of this genus are frequently susceptible to antimicrobials that interfere with protein synthesis (macrolides and tetracyclines) and to DNA replication inhibitors (fluoroquinolones) (1, 8). Some reports of antimicrobial resistance in ureaplasmas have been published. Resistance to fluoroquinolones has been attributed to mutations in gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE, macrolide resistance has been attributed to mutations in the 23S rRNA subunit or in the ribosomal protein L4 or L22 gene, and tetracycline resistance has been attributed to the presence of tet(M) (9–14).

Reports on the antimicrobial susceptibility of Ureaplasma are limited, especially reports separated by species. Moreover, because the multilocus sequence typing (MLST) scheme for this species has been recently developed, there are only a few studies in which the population distribution of this genus has been analyzed. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the susceptibility and clonality of contemporary isolates of Ureaplasma from the United States recovered at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN (including isolates from Mayo Medical Laboratories patients).

(Part of this research was presented at ASM Microbe 2016, Boston, MA, 16 to 20 June 2016.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Specimens and isolates.

Over a 5-month period (October 2015 to February 2016), all patient specimens of any origin testing positive by PCR at Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN, USA) for U. parvum or U. urealyticum (15) were cultured in SP4 medium with urea (Hardy Diagnostics, Santa Maria, CA). A total of 250 clinical isolates (202 U. parvum and 48 U. urealyticum isolates) were recovered and characterized. The source of the samples was diverse and included urine (35.6%), vagina (31.2%), cervix (22.4%), semen (4.8%), bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (1.6%), urethra (1.2%), tracheal aspirates (1.2%), sputum (0.4%), vulva (0.4%), and other urogenital sources (1.2%).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Doxycycline, azithromycin, ciprofloxacin, tetracycline, erythromycin, and levofloxacin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) MICs were determined in duplicate by broth microdilution according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards (CLSI) guidelines (16), using a range of antimicrobial concentrations from 0.125 to 16 μg/ml in 10B broth (Remel, Lenexa, KS, USA). Only the MICs of the last three antimicrobials were interpreted since there are no CLSI breakpoints for the first three agents. U. urealyticum American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) 33175 was used as a quality control (QC) strain in each broth microdilution assay.

Identification of genes encoding tetracycline and fluoroquinolone resistance.

Bacterial DNA extraction from culture broth was performed using a DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The tet(M) gene was assessed by PCR, using previously described primers and cycling conditions, in all Ureaplasma isolates studied (11). For levofloxacin-resistant strains, PCR of the quinolone resistance-determining regions (QRDRs) of gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE was performed as previously described (9, 11). Both tet(M) and QRDR amplicons were purified using ExoSAP-IT (USB Corporation, Cleveland, OH, USA) and bidirectionally sequenced using an ABI 3730xl instrument (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE sequences were analyzed using Clone Manager software (Sci-Ed Software, Cary, NC) and compared with those of the reference strains U. parvum ATCC 700970 and U. urealyticum ATCC 33699 (GenBank accession numbers AF222894 and CP001184, respectively) (9–11).

MLST.

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) was performed according to the original scheme using primers targeting four housekeeping genes, ftsH, rpl22, valS, and thrS (17), on 46 isolates (30 U. parvum and 16 U. urealyticum isolates), including all levofloxacin-resistant isolates, all tet(M)-positive isolates, and a group of susceptible isolates representative of the different study periods and specimen sources. The eBURST package, version 3 (http://eburst.mlst.net/), was used based on allelic profiles with 1,000 resamplings for bootstrapping to establish clonality and determine potential relationships between isolates.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The following five new MLST locus alleles were deposited in the GenBank database under the indicated accession numbers: one for ftsH (KU710257), one for rpl22 (KU710255), two for valS (KU726275 and KU710256), and one for thrS (KU710258).

RESULTS

Prevalence of resistance in Ureaplasma by species.

Of the 202 U. parvum and 48 U. urealyticum isolates tested, levofloxacin resistance (MIC of >2 μg/ml) was found in 6.4% and 5.2%, respectively. All isolates had levofloxacin MICs at least one dilution lower than the ciprofloxacin MICs. Although there are no CLSI breakpoints for ciprofloxacin, 27.2% of U. parvum and the 68.8% of U. urealyticum isolates showed MICs of ≥4 μg/ml (the breakpoint for levofloxacin and moxifloxacin). All U. urealyticum isolates and all but one U. parvum isolate were susceptible to tetracycline (MICs of ≤2 μg/ml) and displayed equal or lower doxycycline MICs. Coresistance to levofloxacin was observed in the single tetracycline-resistant U. parvum isolate. All Ureaplasma isolates were susceptible to erythromycin and had equal or lower azithromycin MICs. Detailed results of MIC distributions, MIC50 and MIC90 values, and percentages of susceptibility by species of Ureaplasma are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

MIC distribution of Ureaplasma isolates separated by species

| Species and antimicrobiala | No. (%) of isolates with the indicated MIC (μg/ml) |

MIC50 (μg/ml) | MIC90 (μg/ml) | % susceptibleb | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤0.125 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | >16 | ||||

| U. parvum (n = 202) | ||||||||||||

| LEV | 14 (6.9) | 64 (31.7) | 85 (42.1) | 23 (11.4) | 3 (1.5) | 8 (4) | 4 (2) | 1 (0.5) | 0.5 | 1 | 93.6 | |

| CIP | 4 (2) | 9 (4.4) | 38 (18.8) | 96 (47.5) | 35 (17.3) | 7 (3.5) | 12 (5.9) | 1 (0.5) | 2 | 4 | NA | |

| TET | 161 (79.7) | 29 (14.4) | 8 (4) | 3 (1.5) | 1 (0.5) | ≤0.125 | 0.25 | 99.5 | ||||

| DOX | 194 (96) | 7 (3.5) | 1 (0.5) | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | NA | ||||||

| ERY | 8 (4) | 32 (15.8) | 63 (31.2) | 66 (32.7) | 31 (15.3) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0.5 | 2 | 100 | ||

| AZM | 8 (4) | 41 (20.3) | 66 (32.7) | 57 (28.2) | 28 (3.9) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0.5 | 2 | NA | ||

| U. urealyticum (n = 48) | ||||||||||||

| LEV | 8 (16.7) | 15 (31.2) | 17 (35.4) | 6 (12.5) | 2 (4.2) | 1 | 2 | 95.8 | ||||

| CIP | 1 (2.1) | 14 (29.2) | 23 (47.9) | 8 (16.7) | 2 (4.2) | 4 | 8 | NA | ||||

| TET | 17 (35.4) | 19 (39.6) | 9 (18.7) | 3 (6.2) | 0.25 | 0.5 | 100 | |||||

| DOX | 48 (100) | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | NA | ||||||||

| ERY | 1 (2.1) | 5 (10.4) | 2 (4.2) | 17 (35.4) | 22 (45.8) | 1 (2.1) | 1 | 2 | 100 | |||

| AZM | 1 (2.1) | 5 (10.4) | 5 (10.4) | 17 (35.4) | 20 (41.7) | 1 | 2 | NA | ||||

LEV, levofloxacin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; TET, tetracycline; DOX, doxycycline; ERY, erythromycin; AZM, azithromycin; n, number of isolates.

NA, not applicable (no CLSI breakpoint).

Molecular characterization of antimicrobial resistance.

Sequence comparison between the QRDRs of reference strains and the QRDRs of study levofloxacin-resistant isolates revealed no mutations in gyrA, gyrB, or parE in any isolate; however, previously described parC quinolone resistance-associated mutations were found. The most frequent mutation detected was Ser83Leu, which was present in 12 (92.1%) and 1 (50%) of the levofloxacin-resistant U. parvum and U. urealyticum isolates, respectively. The remaining levofloxacin-resistant U. parvum isolate harbored a Glu87Lys mutation, while no QRDR mutations were found in a single levofloxacin-resistant U. urealyticum isolate. Three levofloxacin-susceptible isolates (two U. urealyticum isolates and one U. parvum isolate) which showed ciprofloxacin MICs of ≥4 μg/ml were also amplified and sequenced, with no mutations found.

Screening of the tet(M) determinant, which is associated with tetracycline resistance, was carried out, and 10 (4.9%) of the U. parvum isolates were positive, while no U. urealyticum isolates harbored this gene. Interestingly, the 10 positive isolates included the single tetracycline-resistant U. parvum isolate, as well as 9 isolates for which the tetracycline and doxycycline MICs were low.

Detailed results of the genes responsible for antimicrobial resistance and the MICs for a selection of isolates are summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Microbiological features of representative Ureaplasma isolates of the study

| Species and isolate no. | Specimen sourcea | MIC (μg/ml)b |

tet(M) | QRDRc |

MLST |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LEV | CIP | TET | DOX | ERY | AZM | gyrA | gyrB | parC | parE | ftsH | rpl22 | valS | rprS | STd | |||

| U. parvum | |||||||||||||||||

| IDRL-10860 | Urine | 4 | 16 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | 0.5 | 0.5 | − | WT | WT | S83L | WT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ST1 |

| IDRL-10857 | Vagina | 4 | 16 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 2 | 2 | − | WT | WT | S83L | WT | 35 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ST95 |

| IDRL-10940 | Vagina | 8 | 16 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | 0.5 | 0.5 | − | WT | WT | S83L | WT | 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ST56 |

| IDRL-10790 | Urethra | 4 | 16 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | 0.5 | 0.5 | − | WT | WT | S83L | WT | 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ST56 |

| IDRL-10904 | Cervix | 4 | 16 | 8 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | + | WT | WT | S83L | WT | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ST2 |

| IDRL-11151 | Cervix | 4 | 16 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | 0.5 | 0.5 | − | WT | WT | S83L | WT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ST1 |

| IDRL-11156 | Urine | 4 | 16 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | 2 | 1 | − | WT | WT | S83L | WT | 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ST56 |

| IDRL-11160 | Urine | 16 | >16 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | 1 | 0.5 | − | WT | WT | S83L | WT | 2 | 1 | 22e | 1 | ST108f |

| IDRL-11170 | Vagina | 8 | 16 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | 0.25 | 0.25 | − | WT | WT | S83L | WT | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ST22 |

| IDRL-11178 | Vagina | 4 | 16 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | 0.5 | 0.5 | + | WT | WT | S83L | WT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ST1 |

| IDRL-11211 | Vagina | 4 | 16 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | 1 | 0.5 | − | WT | WT | S83L | WT | 1 | 1 | 23e | 1 | ST109f |

| IDRL-11260 | Vagina | 8 | 16 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | 2 | 2 | − | WT | WT | S83L | WT | 1 | 12 | 1 | 1 | ST103 |

| IDRL-11232 | Cervix | 8 | 16 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | 1 | 1 | − | WT | WT | E87K | WT | 20 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ST111f |

| IDRL-11141 | Vagina | 0.5 | 2 | 0.25 | ≤0.125 | 1 | 1 | + | ND | ND | ND | ND | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | ST105 |

| IDRL-11142 | Vagina | 0.5 | 2 | 0.25 | ≤0.125 | 0.5 | 0.5 | + | ND | ND | ND | ND | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ST4 |

| IDRL-11149 | Urine | 0.5 | 2 | 0.25 | ≤0.125 | 1 | 1 | + | ND | ND | ND | ND | 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ST56 |

| IDRL-11152 | Cervix | 0.5 | 2 | 0.25 | ≤0.125 | 0.5 | 0.5 | + | ND | ND | ND | ND | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ST4 |

| IDRL-11177 | Urine | 0.5 | 2 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | 0.5 | 0.5 | + | ND | ND | ND | ND | 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ST56 |

| IDRL-11179 | Vagina | 0.5 | 2 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | 0.5 | 0.25 | + | ND | ND | ND | ND | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ST38 |

| IDRL-11252 | Vagina | 0.25 | 0.5 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | 0.25 | 0.25 | + | ND | ND | ND | ND | 2 | 14e | 1 | 1 | ST110f |

| IDRL-11268 | Vagina | 0.5 | 2 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | 2 | 2 | + | ND | ND | ND | ND | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ST4 |

| IDRL-10852 | Vagina | 0.25 | 2 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | 2 | 2 | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ST4 |

| IDRL-10835 | Cervix | 2 | 8 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | 0.5 | 0.5 | − | WT | WT | WT | WT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ST1 |

| IDRL-10774 | BAL | 0.25 | 2 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | 0.5 | 0.5 | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ST22 |

| IDRL-10874 | Vagina | 0.5 | 2 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | 0.5 | 0.25 | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ST1 |

| IDRL-10923 | Cervix | 0.25 | 1 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | 0.25 | 0.25 | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ST2 |

| IDRL-11125 | Cervix | 0.25 | 2 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | 1 | 1 | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | 2 | 14e | 1 | 1 | ST110f |

| IDRL-11207 | Vagina | 1 | 4 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | 1 | 0.5 | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ST22 |

| IDRL-11257 | TA | 0.5 | 2 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | 0.25 | 0.25 | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ST1 |

| IDRL-11271 | Cervix | 0.5 | 2 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | 2 | 2 | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ST2 |

| U. urealyticum | |||||||||||||||||

| IDRL-10763 | BAL | 4 | 16 | 0.25 | ≤0.125 | 2 | 2 | − | WT | WT | S83L | WT | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ST7 |

| IDRL-11217 | Urine | 4 | 16 | 0.25 | ≤0.125 | 2 | 2 | − | WT | WT | WT | WT | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | ST47 |

| IDRL-10967 | Vagina | 2 | 8 | 0.5 | ≤0.125 | 2 | 2 | − | WT | WT | WT | WT | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | ST47 |

| IDRL-11184 | Vagina | 2 | 8 | 0.5 | ≤0.125 | 2 | 2 | − | WT | WT | WT | WT | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | ST47 |

| IDRL-11235 | TA | 0.5 | 4 | 0.25 | ≤0.125 | 2 | 2 | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | 42e | 3 | 4 | 18e | ST112f |

| IDRL-11135 | Urine | 1 | 4 | 0.5 | ≤0.125 | 2 | 2 | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | 6 | 3 | 4 | 11 | ST54 |

| IDRL-10787 | Cervix | 2 | 8 | 0.25 | ≤0.125 | 1 | 1 | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | ST47 |

| IDRL-10928 | Urine | 0.5 | 2 | 0.25 | ≤0.125 | 0.25 | 0.25 | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | 4 | 11 | 4 | 4 | ST113f |

| IDRL-11163 | Cervix | 0.5 | 4 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | 1 | 1 | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | ST9 |

| IDRL-11213 | Vagina | 0.5 | 4 | 0.25 | ≤0.125 | 2 | 2 | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | 41 | 3 | 4 | 11 | ST101 |

| IDRL-11269 | Cervix | 0.5 | 2 | 0.5 | ≤0.125 | 2 | 2 | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | 6 | 3 | 4 | 11 | ST54 |

| IDRL-11295 | Urine | 0.5 | 2 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | 1 | 1 | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | 42e | 3 | 4 | 18e | ST112f |

| IDRL-11298 | Urine | 0.5 | 2 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | 2 | 1 | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | ST47 |

| IDRL-11299 | Urine | 0.5 | 2 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | 1 | 0.5 | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | ST9 |

| IDRL-11306 | Urine | 0.5 | 2 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | 1 | 0.5 | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ST7 |

| IDRL-11308 | Urine | 2 | 8 | 0.25 | ≤0.125 | 1 | 0.5 | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | ST9 |

BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; TA, tracheal aspirate.

LEV, levofloxacin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; TET, tetracycline; DOX, doxycycline; ERY, erythromycin; AZM, azithromycin.

WT, wild type; ND, not done.

ST, sequence type.

MLST and clonality.

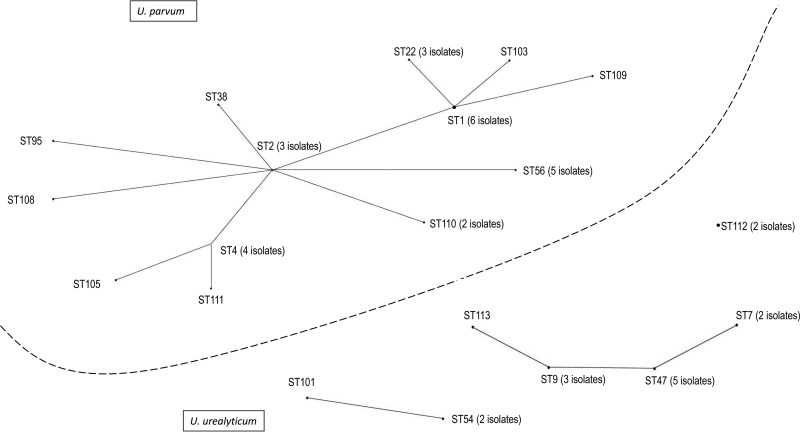

MLST revealed 14 clones among the 30 U. parvum isolates tested. ST1 and ST56, which belong to the same clonal complex (CC) and have three shared loci, were the most frequent clones, with six and five isolates, respectively, in each. Among the 16 U. urealyticum isolates studied, seven profiles were found with ST47 (five isolates) and ST9 (three isolates), which belong to the same CC, being the most common. Five and six new alleles and ST profiles, respectively, were discovered. Detailed results are shown in Table 2. The eBURST package revealed three main clusters (I to III) and a single nongroupable clone (two isolates). Cluster I comprised the totality of U. parvum isolates, while most of U. urealyticum isolates were distributed in clusters II and III (Fig. 1). No correlation between ST and antimicrobial resistance was observed (Table 2).

FIG 1.

Population distribution of 46 Ureaplasma isolates established with eBURST. Three clusters (cluster I, consisting of U. parvum isolates; clusters II and III, consisting of U. urealyticum isolates) and the remaining single clone are indicated. The number of isolates is shown for those sequence types with more than one isolate.

DISCUSSION

Ureaplasma species have been recognized as important pathogens in recent years, not only for their potential pathogenicity linked to urogenital tract or intrauterine infections but also for their ability to produce systemic diseases in newborns and immunosuppressed patients (1–4, 6, 18). The limited therapeutic options available to combat infections by these microorganisms make it important to understand their susceptibility to potentially active antimicrobials such as the fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, and macrolides. There are few data available on antimicrobial susceptibility of Ureaplasma, especially in terms of individual species. Prior data have been produced using the Mycoplasma IST2 kit (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Étoile, France), which has been shown to compare poorly with the reference broth microdilution method (9, 12). Also, inconsistencies can occur due to the use of varying interpretative criteria (9, 12). One of the reasons for the limited data available about Ureaplasma susceptibility relates to difficulties in cultivation and in the performance of broth microdilution (especially in regard to preparation of the inoculum). Although CLSI guidelines recommend testing each drug in duplicate, we suggest that this may be not necessary. Of the six antimicrobials tested against the 250 isolates (a total of 1,500 tests), only nine differences in the MICs between duplicates were found, and they were never greater than the single dilution variability inherent to any broth microdilution method. By eliminating the testing of duplicates, costs could be reduced, and the protocol could be simplified; this method would thus be rendered more applicable for use in clinical microbiology laboratories.

The fluoroquinolone resistance rate in Ureaplasma species varies widely among different countries and studies. For instance, in a recent study carried out in Switzerland, Schneider et al. reported a rate of nonsusceptibility to ciprofloxacin of 19.4% (9), while in a recent study in Italy, 41% of isolates were ciprofloxacin resistant (19). Levofloxacin was not tested in these studies. However, in another study carried out using clinical Ureaplasma isolates recovered from neonates in England and Wales between 2007 and 2013, a much lower ciprofloxacin resistance rate of 1.5% was reported, with no levofloxacin resistance found. Regarding the United States, very limited data have become available regarding the frequency of fluoroquinolone resistance in Ureaplasma species since the first description of a resistant strain in 2006 (13). Before our work, a single study was carried out to evaluate the occurrence and molecular mechanisms of fluoroquinolone resistance in clinical Ureaplasma isolates from the United States and reported a levofloxacin resistance rate of 5% (ciprofloxacin was not tested) (20). These results are similar to those from our study in which we found levofloxacin resistance rates of 6.4% and 5.2% in U. parvum and U. urealyticum, respectively. Interestingly, although there was no overall difference in the percentages of resistance between the species, fluoroquinolone MIC50 and MIC90 values were one dilution higher for U. urealyticum than for U. parvum. Furthermore, the percentage of isolates with ciprofloxacin MICs of ≥4 μg/ml was higher for U. urealyticum (68.8%) than for U. parvum (27.2%).

Sequence analysis of the QRDRs in levofloxacin-resistant isolates revealed that the mechanism of resistance was due to mutations in parC, with a Ser83Leu substitution being most frequent, followed by a Glu87Lys substitution (Table 2). Both substitutions have been previously reported, with the first being the most frequent mutation responsible for fluoroquinolone resistance in Ureaplasma species worldwide (9–12, 21). A single levofloxacin-resistant U. urealyticum isolate and the three levofloxacin-susceptible isolates with high ciprofloxacin MICs analyzed did not harbor QRDR mutations. An absence of QRDR mutations in fluoroquinolone-resistant isolates has been previously reported, suggesting that undescribed resistance mechanisms may exist in these isolates (9).

It is interesting that no macrolide resistance was found among the Ureaplasma isolates studied; this is consistent with the low rate of resistance to this antimicrobial group previously reported in several countries, including the United States (9, 12, 22).

A single doxycycline-resistant isolate (U. parvum) was found although 4.9% of the isolates of this species were positive for the tet(M) gene. These data contrast with the 33% tetracycline resistance rate previously reported in the United States in Ureaplasma species (22). The presence of tet(M) in tetracycline-susceptible isolates had been previously documented (11, 12, 23). Some tet(M) variants may exhibit inducible resistance, and therefore it may be necessary to screen by both broth microdilution to assess phenotypic susceptibility and molecular methods to detect tet(M) variants (12).

MLST showed a high diversity within the clinical Ureaplasma isolates studied, regardless of antimicrobial susceptibility. Isolates were grouped in three clusters and demonstrated high correlation between the groups and species for U. parvum (cluster I) and U. urealyticum (clusters II and III), as previously observed in studies from China and Switzerland (9, 17). Most of the clones found in this study were described in Chinese and Swiss populations; furthermore, some (ST1, ST2, ST4, ST9, ST47, ST54, and ST101) were associated with fluoroquinolone resistance in Switzerland (9). Since the Ureaplasma MLST scheme has been developed only recently, further studies are necessary to expand the knowledge about clonality in this species. Together with the information provided by the previous two studies, our results suggest that, as in other species, some clonal lineages of Ureaplasma species could have increased epidemic potential that may be associated with pathogenicity or spread of antimicrobial resistance.

In conclusion, the present work extends previous knowledge regarding susceptibility to antimicrobial agents, resistance mechanisms, and clonality in Ureaplasma species in the United States, knowledge which could contribute to optimized treatment of infections caused by these pathogens and better understanding of their epidemiology.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the staff of the Mayo Clinic Clinical Bacteriology Laboratory for their outstanding work performing Ureaplasma PCR. We also thank A. Endimiani for kindly providing advice for regarding MLST performance and interpretation.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN. J.F. was supported by a grant from the Sociedad Española de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica.

REFERENCES

- 1.Waites KB, Katz B, Schelonka RL. 2005. Mycoplasmas and ureaplasmas as neonatal pathogens. Clin Microbiol Rev 18:757–789. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.4.757-789.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fonseca LT, Silveira RC, Procianoy RS. 2011. Ureaplasma bacteremia in very low birth weight infants in Brazil. Pediatr Infect Dis J 30:1052–1055. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31822a8662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gwee A, Chinnappan M, Starr M, Curtis N, Pellicano Bryant. 2013. Ureaplasma meningitis and subdural collections in a neonate. Pediatr Infect Dis J 32:1043–1044. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31829ae285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Capoccia R, Greub G, Baud D. 2013. Ureaplasma urealyticum, Mycoplasma hominis and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Curr Opin Infect Dis 26:231–240. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328360db58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biran V, Dumitrescu AM, Doit C, Gaudin A, Bebear C, Boutignon H, Bingen E, Baud O, Bonacorsi S, Aujard Y. 2010. Ureaplasma parvum meningitis in a full-term newborn. Pediatr Infect Dis J 29:1154. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181f69013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bharat A, Cunningham SA, Budinger GRS, Kreisel D, DeWet CJ, Gelman AE, Waites K, Crabb D, Xiao L, Bhorade S, Ambalavanan N, Dilling DF, Lowery EM, Astor T, Hachem R, Krupnick AS, DeCamp MM, Ison MG, Patel R. 2015. Disseminated Ureaplasma infection as a cause of fatal hyperammonemia in humans. Sci Transl Med 7:284re3. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa8419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beeton ML. 28 September 2015. Possible missed diagnosis of Ureaplasma spp infection in a case of fatal hyperammonemia after repeat renal transplantation. J Clin Anesth doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2015.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waites KB, Crouse DT, Cassell GH. 1993. Therapeutic considerations for Ureaplasma urealyticum infections in neonates. Clin Infect Dis 17:S208–S214. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.Supplement_1.S208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneider SC, Tinguely R, Droz S, Hilty M, Dona V, Bodmer T, Endimiani A. 2015. Antibiotic susceptibility and sequence type distribution of Ureaplasma species isolated from genital samples in Switzerland. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:6026–6031. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00895-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beeton ML, Chalker VJ, Kotecha S, Spiller OB. 2009. Comparison of full gyrA, gyrB, parC and parE gene sequences between all Ureaplasma parvum and Ureaplasma urealyticum serovars to separate true fluoroquinolone antibiotic resistance mutations from non-resistance polymorphism. J Antimicrob Chemother 64:529–538. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beeton ML, Chalker VJ, Maxwell NC, Kotecha S, Spiller OB. 2009. Concurrent titration and determination of antibiotic resistance in Ureaplasma species with identification of novel point mutations in genes associated with resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:2020–2027. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01349-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beeton ML, Chalker VJ, Jones LC, Maxwell NC, Spiller OB. 2016. Antibiotic resistance among clinical Ureaplasma isolates recovered from neonates in England and Wales between 2007 and 2013. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:52–56. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00889-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duffy L, Glass J, Hall G, Avery R, Rackley R, Peterson S, Waites K. 2006. Fluoroquinolone resistance in Ureaplasma parvum in the United States. J Clin Microbiol 44:1590–1591. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.4.1590-1591.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Govender S, Gqunta K, le Roux M, de Villiers B, Chalkley LJ. 2012. Antibiotic susceptibilities and resistance genes of Ureaplasma parvum isolated in South Africa. J Antimicrob Chemother 67:2821–2824. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cunningham SA, Mandrekar JN, Rosenblatt JE, Patel R. 2013. Rapid PCR detection of Mycoplasma hominis, Ureaplasma urealyticum, and Ureaplasma parvum. Int J Bacteriol 2013:168742. doi: 10.1155/2013/168742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2011. Methods for antimicrobial susceptibility testing for human mycoplasmas; approved guideline. CLSI document M43-A. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang J, Kong Y, Feng Y, Huang J, Song T, Ruan Z, Song J, Jiang Y, Yu Y, Xie X. 2014. Development of a multilocus sequence typing scheme for Ureaplasma. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 33:537–544. doi: 10.1007/s10096-013-1981-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eilers E, Moter A, Bollmann R, Haffner D, Querfeld U. 2007. Intrarenal abscesses due to Ureaplasma urealyticum in a transplanted kidney. J Clin Microbiol 45:1066–1068. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01897-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pignanelli S, Pulcrano G, Iula VD, Zaccherini P, Testa A, Catania MR. 2014. In vitro antimicrobial profile of Ureaplasma urealyticum from genital tract of childbearing-aged women in Northern and Southern Italy. APMIS 122:552–555. doi: 10.1111/apm.12184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiao L, Crabb DM, Duffy LB, Paralanov V, Glass JI, Waites KB. 2012. Chromosomal mutations responsible for fluoroquinolone resistance in Ureaplasma species in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:2780–2783. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06342-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bebear CM, Renaudin H, Charron A, Gruson D, Lefrancois M, Bebear C. 2000. In vitro activity of trovafloxacin compared to those of five antimicrobials against mycoplasmas including Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma urealyticum fluoroquinolone-resistant isolates that have been genetically characterized. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 44:2557–2560. doi: 10.1128/AAC.44.9.2557-2560.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiao L, Crabb DM, Duffy LB, Paralanov V, Glass JI, Hamilos DL, Waites KB. 2011. Mutations in ribosomal proteins and ribosomal RNA confer macrolide resistance in human Ureaplasma spp. Int J Antimicrob Agents 37:377–379. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kotrotsiou T, Exindari M, Diza E, Gioula A, Melidou A, Malisiovas N. 2015. Detection of the tetM resistance determinant among phenotypically sensitive Ureaplasma species by a novel real-time PCR method. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 81:85–88. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2014.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]