Abstract

Background: Knowledge on specific biological pathways mediating disease occurrence (e.g., inflammation) may be utilized to construct hypotheses-driven dietary patterns that take advantage of current evidence on disease-related hypotheses and the statistical methods of a posteriori patterns.

Objective: We developed and validated an empirical dietary inflammatory index (EDII) based on food groups.

Methods: We entered 39 pre-defined food groups in reduced rank regression models followed by stepwise linear regression analyses in the Nurses' Health Study (NHS, n = 5230) to identify a dietary pattern most predictive of 3 plasma inflammatory markers: interleukin-6 (IL-6), C-reactive protein (CRP), and tumor necrosis factor α receptor 2 (TNFαR2). We evaluated the construct validity of the EDII in 2 independent samples from NHS-II (n = 1002) and Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS, n = 2632) using multivariable-adjusted linear regression models to examine how well the EDII predicted concentrations of IL-6, CRP, TNFαR2, adiponectin, and an overall inflammatory marker score combining all biomarkers.

Results: The EDII is the weighted sum of 18 food groups; 9 are anti-inflammatory and 9 proinflammatory. In NHS-II and HPFS, the EDII significantly predicted concentrations of all biomarkers. For example, the relative concentrations comparing extreme EDII quintiles in NHS-II were: adiponectin, 0.88 (95% CI, 0.80, 0.96), P-trend = 0.003; and CRP, 1.52 (95% CI, 1.18, 1.97), P-trend = 0.002. Corresponding associations in HPFS were: 0.87 (95% CI, 0.82, 0.92), P-trend < 0.0001; and 1.23 (95% CI, 1.09, 1.40), P-trend = 0.002.

Conclusion: The EDII represents, to our knowledge, a novel, hypothesis-driven, empirically derived dietary pattern that assesses diet quality based on its inflammatory potential. Its strong construct validity in independent samples of women and men indicates its usefulness in assessing the inflammatory potential of whole diets. Additionally, the EDII may be calculated in a standardized and reproducible manner across different populations thus circumventing a major limitation of dietary patterns derived from the same study in which they are applied.

Keywords: hypothesis-driven, dietary patterns, dietary inflammatory potential, inflammatory markers, inflammation

Introduction

Dietary patterns capture multiple dietary factors and provide a comprehensive assessment of diet, which may account for the complex interactions between nutrients and foods. Derived dietary patterns thus may be more predictive of diet–disease associations than are analyses that use single foods or nutrients (1, 2). The 2 main approaches for creating dietary patterns are the a priori or index-based approach and the a posteriori or data-driven approach. A priori pattern scores are developed on the basis of current scientific evidence with respect to the relation between diet and disease, e.g., the Alternative Healthy Eating Index (3), or current dietary guidelines or recommendations, e.g., the dietary index based on adherence to the 2007 World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research recommendations for cancer prevention (4). In contrast, the a posteriori approach is based on statistical exploratory methods such as factor analysis or principal components analysis (5–7), and the dietary pattern derived is not necessarily based on any disease-related hypothesis. Knowledge of specific biological pathways mediating disease occurrence (e.g., inflammation) may be harnessed to construct hypothesis-driven dietary patterns that take advantage of both current scientific evidence for disease-related hypotheses and the statistical exploratory methods of a posteriori dietary patterns. Hypothesis-driven dietary patterns then can be applied in a more standardized manner across different populations in a manner similar to a priori patterns.

Chronic inflammation plays an important role in the development of many chronic diseases (8–10), and some dietary patterns have been shown to be associated with inflammation. Higher scores on a priori–defined dietary patterns such as the Healthy Eating Index and the Mediterranean diet are associated with lower concentrations of inflammatory markers (11–13), although the development of these indexes was not focused on inflammation. A posteriori–defined patterns such as the Western dietary pattern have been associated with higher concentrations of inflammatory markers, whereas higher consumption of the prudent pattern is linked with lower concentrations of inflammatory markers (11, 14). However, the evidence of the association between dietary patterns and inflammation is still inconsistent, especially for dietary patterns derived with the use of a posteriori methods (11, 15).

Approaches to develop hypothesis-driven dietary patterns that can be applied across different populations could enhance between-study comparability and utility of study findings (2, 7). In addition, developing standardized patterns on the basis of specific disease mechanisms such as inflammation that mediates the risk of many chronic diseases could elucidate biological mechanisms relating dietary patterns to disease development or progression. This could be achieved with the use of reduced rank regression (RRR)11, an a posteriori statistical method that determines linear functions of predictors (e.g., food groups in the current study) by maximizing the explained variation in the responses (e.g., inflammatory markers in the current study) (16–18). Unlike other widely used statistical exploratory methods such as principal components analysis or factor analysis, which derive dietary patterns based on the covariance structure of foods, RRR uses information on the response variables to derive the dietary patterns (16, 17).

Our objectives in the current study were 3-fold: 1) to use RRR to develop an empirical dietary inflammatory index (EDII) with the use of dietary and inflammatory markers data from the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS); 2) to evaluate the construct validity of the EDII in 2 independent samples of women and men in the Nurses’ Health Study II (NHS-II) and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (HPFS), respectively; and 3) to conduct sensitivity analyses with the use of potential alternative versions of the EDII.

Methods

Study populations.

The NHS, NHS-II, and HPFS are ongoing prospective cohorts established in 1976, 1989, and 1986, respectively. The NHS (n = 121,701) enrolled female registered nurses aged 30–55 y, whereas the NHS-II (n = 116,430) enrolled younger female registered nurses 25–42 y of age (19). The HPFS (n = 51,529) enrolled male health professionals aged 40–75 y. Blood samples were collected from subpopulations of the 3 cohorts that were free of diagnosed cancer, diabetes, heart disease or stroke as follows: NHS (n = 32,826) from 1989 to 1990, NHS-II (n = 29,611) from 1996 to 1999, and HPFS (n = 18,225) from 1993 to 1994 (20). Blood collection was conducted with the use of similar protocols for all cohorts. The procedures, including collection, handling, and storage, have been summarized previously (21). In the current study, we used data from previous matched case-control studies nested within each of the 3 cohorts that measured plasma concentrations of IL-6, C-reactive protein (CRP), TNF-α receptor 2 (TNFαR2), and adiponectin. The institutional review boards at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health approved this study.

Assessment of inflammatory markers.

Procedures for the measurement of plasma inflammatory markers (IL-6, CRP, TNFαR2, and adiponectin) in the NHS, NHS-II, and HPFS have been described previously (20, 22–25). Briefly, concentrations of IL-6 and TNFαR2 were measured with the use of ELISAs (R&D Systems). CRP was measured with the use of a high-sensitivity immunoturbidimetric assay with reagents and calibrators from Denka Seiken Company. We excluded participants with CRP concentrations >10 mg/L, because this likely may have been due to infection or medication use (26). Concentrations of adiponectin were measured with the use of a competitive radioimmunoassay (Linco Research). In the nested case-control studies in which these biomarkers were measured, samples from cases and their matched controls were analyzed in the same batch. Quality-control samples were interspersed randomly among the case-control samples, and laboratory personnel were blinded to quality-control and case-control status for all assays. The intra-assay CV from blinded quality-control samples ranged from 2.9% to 12.8% for IL-6, 1.0% to 9.1% for CRP, 4.0% to 10.0% for TNFαR2, and 8.1% to 11.1% for adiponectin across batches. In NHS-II and HPFS, we derived an overall inflammatory marker score by computing a z score for each of the 4 inflammatory markers and then summing the z scores to create a standardized overall inflammatory marker score for each participant as follows:

|

Assessment of dietary and nondietary data.

Dietary data are updated every 4 y in the NHS (since 1980), NHS-II (since 1991), and HPFS (since 1986) with a semi-quantitative FFQ, the validity and reliability of which have been reported (27–29). We used dietary data from the questionnaires closest to the blood draw, i.e., the 1986 and 1990 FFQs for the NHS, the 1995 and 1999 FFQs for the NHS-II, and the 1990 and 1994 FFQs for the HPFS, averaging dietary data across the 2 FFQs to reduce within-subject variability in long-term diet (30). Participants with excessive missing items (≥70) on the FFQs, implausibly low or high energy intake (<600 or >3500 kcal/d for women and <800 or >4200 kcal/d for men) were excluded (31).

All 3 cohorts collected nondietary data (e.g., medical history and health practices) and updated the data through biennial self-administered questionnaires. We calculated participants’ BMIs (in kg/m2) with the use of height (meters) reported at baseline for each cohort, and weight (kilograms) reported at each biennial questionnaire cycle. Participants reported smoking status (classified as never, former, or current), and we calculated physical activity, expressed in metabolic equivalent task hours per week, by summing the mean metabolic equivalent task hours per week for each activity, which included tennis/squash/racquetball, rowing, calisthenics, walking, jogging, running, bicycling, and swimming. We averaged data for BMI and physical activity across the 2 questionnaires and replaced missing data with available corresponding data from the previous questionnaire for all variables. Regular use of aspirin or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) was defined as the use of ≥2 standard tablets (325 mg) of aspirin or ≥2 tablets of NSAIDs/wk. We derived an inflammation-related chronic disease comorbidity score by summing the presence (1) or absence (0) of the following chronic diseases and conditions: hypercholesterolemia, cancer, diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, and rheumatoid or other arthritis).

In the NHS, we excluded participants with missing diet and covariate data (n = 1329), retaining a final sample of 5230 for EDII development. For EDII validation, we excluded 217 women and 223 men with missing diet and covariate data, leaving a final sample of 1002 women in the NHS-II and 2632 men in the HPFS.

Development of the EDII.

The goal for developing the EDII was to create empirically a score based on food groups to assess the overall inflammatory potential of whole diets. We based the score on food groups rather than nutrients to approximate how people perceive diet. We used dietary and inflammatory marker data in the NHS to develop the EDII. We first calculated the mean daily intake of 39 previously defined food groups (31) from the 1986 and 1990 FFQs. We then applied RRR (16) to derive a dietary pattern associated with 3 inflammatory markers: IL-6, CRP, and TNFαR2—inflammatory markers that have been associated with a number of diseases and are among the most commonly used inflammatory markers to examine disease endpoints (20, 32–34). RRR identifies linear functions of predictors (e.g., food groups) that simultaneously explain as much variation in the responses of interest (e.g., inflammatory markers) as possible (16, 35). The first factor obtained by RRR was retained for subsequent analyses (we called this the RRR dietary pattern). We then used stepwise linear regression analyses to identify the most important component food groups contributing to the RRR dietary pattern, with the biomarker response score (RRR dietary pattern) as the dependent variable, the 39 food groups as independent variables, and a significance level of P = 0.05 for entry into and retention in the model. The intake of the food groups identified in the stepwise linear regression analyses was weighted by the regression coefficients derived from the final stepwise linear regression model and then summed to constitute the EDII score. Finally, the EDII was rescaled by dividing by 1000 to reduce the magnitude of the scores and aid in interpretation of statistical analyses. The EDII assesses the inflammatory potential of an individual’s diet on a continuum from maximally anti-inflammatory to maximally proinflammatory, with higher (more positive) scores indicating more proinflammatory diets and lower (more negative) scores indicating anti-inflammatory diets.

Sensitivity analyses.

In the sensitivity analyses, we created 6 alternative versions of the EDII: 1) an EDII without weights; 2) an EDII that included added nutrients, including supplements, in the food groups; 3) an EDII that included added nutrients, but not supplements, in the food groups; 4) an EDII from BMI-adjusted biomarkers; 5) an EDII for nonusers of aspirin/NSAIDs; and 6) an EDII for control subjects only. In version 3, nutrients that have been associated with inflammatory markers (36) were selected for this sensitivity analysis. They included thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, vitamin A, vitamin B-12, vitamin C, vitamin D, vitamin E, selenium, β-carotene, folate, iron, magnesium, ω-3 fats, zinc, ω-6 fats, vitamin B-6, total fiber, alcohol, caffeine, carbohydrates, total cholesterol, monounsaturated fats, polyunsaturated fats, trans fats, protein, saturated fats, isoflavones, anthocyanidins, flavan-3-ols, flavanones, flavonols, and flavones. The first 17 nutrients listed also had separate variables with supplements, and all nutrients were energy-adjusted with the use of the residual method (37). In version 4, we also used BMI-adjusted biomarkers as responses in the RRR model, given that BMI may mediate and/or confound the association of the EDII with inflammatory markers. The biomarkers were adjusted for BMI before they were used in the RRR model, i.e., we adjusted biomarkers for BMI by regressing each of the 3 biomarkers on BMI in 3 separate univariate linear regression models and then used the residuals (instead of the original biomarker) in the RRR procedure. In version 5, we constructed the EDII for nonusers of aspirin/NSAIDs, because in previous studies, a nutrient-based dietary inflammatory index was not associated with inflammatory markers in NSAID users (38–40). Finally, in version 6, we constructed the EDII for only control participants of the nested case-control studies (although all nested case-control studies that generated the data for the current study used prediagnostic blood samples in individuals free from diagnosed chronic diseases). This alternative EDII tested the robustness of the EDII to using the entire sample of cases and controls compared with the use of only the controls.

Statistical analysis.

In the NHS, 5230 women with data on the 3 inflammatory markers (IL-6, CRP, and TNFαR2) were used to develop the EDII, whereas in the NHS-II and HPFS, 1002 women and 2632 men, respectively, with data on these same biomarkers plus adiponectin were used to evaluate the construct validity of the EDII. We expected the EDII developed without the use of adiponectin to be associated with concentrations of adiponectin and in the expected (inverse) direction. We described participants’ characteristics with the use of means ± SDs for continuous variables, geometric means ± CVs for log-transformed variables, and frequencies (%) for categorical variables. Concentrations of all 4 biomarkers were back-transformed to their original units (ex, where x is the transformed biomarker value) because biomarkers were ln-transformed before analyses. We calculated correlation coefficients between the EDII, its potential alternative versions, and inflammatory markers in the NHS.

In the NHS, we graphically assessed the distribution of the absolute mean concentrations of IL-6, CRP, and TNFαR2 across quintiles of the EDII stratified by aspirin/NSAID use (regular users compared with nonusers) and by BMI [normal weight (<25 kg/m2) compared with overweight/obese (≥25 kg/m2)], while adjusting for the following covariates: age at blood draw (continuous), total energy intake, physical activity, smoking status, BMI, regular aspirin/NSAID use (when not stratifying on these 2 covariates), case-control status, batch effects for biomarker measurements, the inflammation-related chronic disease comorbidity score, and menopausal status and postmenopausal hormone use (for women). We adjusted for case-control status in the multivariable models, given that the data were from matched nested case-control studies. Also, the biomarkers were determined in several batches; therefore, we adjusted for batch number in order to minimize potential batch effects.

In the validation phase in the NHS-II and HPFS samples, we derived scores for the EDII and its potential alternative versions and calculated correlations among the derived pattern scores and the construct validators of the EDII (IL-6, CRP, TNFαR2, adiponectin, and the overall inflammatory marker score). The association between the EDII and biomarkers was assessed with the use of multivariable-adjusted linear regression models to calculate relative concentrations of the biomarkers in EDII quintiles with the lowest quintile as reference (i.e., the ratios of biomarker concentrations in the higher EDII quintiles to the concentration in the lowest quintile).

All multivariable models were adjusted for the previously described potential confounding variables. We used the continuous index values adjusted for multiple covariates to assess the linear trend of biomarker concentrations across quintiles of the categorized index. Potential effect modification of the association between the EDII and inflammatory markers by BMI and aspirin/NSAID use was assessed by including EDII × covariate interaction terms in the multivariable-adjusted models.

In sensitivity analyses, we applied each of the alternative versions of the EDII (the unweighted EDII, the EDII including nutrients with supplements, the EDII including nutrients without supplements, the EDII from BMI-adjusted biomarkers, the EDII derived in nonusers of aspirin/NSAIDs, and the EDII derived in control subjects only) in multivariable-adjusted linear regression models to determine relative concentrations of the 4 biomarkers across index quintiles. All analyses were conducted with the use of SAS version 9.3 for UNIX. All tests were 2-sided and P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistically significant results (including interaction terms).

Results

Among the 39 food groups entered in the RRR model, there was wide variation in the magnitude of associations for each of the biomarkers (Supplemental Table 1). Eighteen food groups were identified in the subsequent stepwise linear regression model as significant contributors to the EDII (Table 1). The intake of fish (other than dark-meat fish), tomatoes, processed meats, high-energy beverages, other vegetables (i.e., vegetables other than leafy green vegetables and dark yellow vegetables), red meats, low-energy beverages, refined grains, and organ meats was positively related to concentrations of inflammatory markers, whereas the intake of pizza, wine, leafy green vegetables, dark yellow vegetables (comprising carrots, yellow squash, yams), beer, coffee, fruit juice, snacks, and tea was inversely related to concentrations of inflammatory markers (Table 1). Components of the potential alternative versions of the EDII are presented in Supplemental Table 2. The potential alternative EDII version from BMI-adjusted biomarkers had the fewest components.

TABLE 1.

Components of the EDII and their correlations with plasma inflammatory markers in the Nurses’ Health Study (n = 5230, 1986–1990)1

| RRR dietary pattern2 | EDII | CRP | IL-6 | TNFαR2 | Weights | |

| RRR dietary pattern2 | 1.00 | 0.96 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.15 | NA |

| EDII3 | 1.00 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.15 | NA | |

| EDII components3 | ||||||

| Positive associations | ||||||

| Processed meat | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.08 | 0.09 | −0.0001* | 165.03 |

| Red meat | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.07 | 0.06 | −0.03 | 140.19 |

| Organ meat | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.01* | 144.61 |

| Other fish | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.05 | −0.02* | −0.04 | 252.45 |

| Other vegetables | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.03 | −0.003* | 0.002* | 136.14 |

| Refined grains | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.02* | 81.21 |

| High-energy beverages | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.01* | 156.85 |

| Low-energy beverages | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.07 | 0.05 | −0.01* | 94.77 |

| Tomatoes | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.02* | −0.002* | 167.92 |

| Inverse associations | ||||||

| Beer | −0.19 | −0.19 | −0.09 | −0.08 | −0.12 | −136.99 |

| Wine | −0.38 | −0.38 | −0.12 | −0.13 | −0.15 | −249.70 |

| Tea | 0.02* | 0.02* | 0.01* | −0.02 | −0.01* | −42.25 |

| Coffee | −0.49 | −0.51 | −0.11 | −0.07 | −0.10 | −83.18 |

| Dark yellow vegetables | −0.13 | −0.14 | −0.02* | −0.06 | −0.02* | −165.37 |

| Leafy green vegetables | −0.23 | −0.24 | −0.02* | −0.07 | −0.06 | −190.29 |

| Snacks | −0.06 | −0.06 | −0.004* | −0.02* | −0.04 | −45.08 |

| Fruit juice | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.02* | −0.02* | −0.02* | −58.95 |

| Pizza | −0.07 | −0.08 | −0.03 | 0.001* | −0.06 | −1175.21 |

Values in columns 2–6 are Spearman correlation coefficients, *P > 0.05. Column 7 values are regression coefficients for each EDII component obtained from the last step of the stepwise linear regression analysis. CRP, C-reactive protein; EDII, empirical dietary inflammatory index; NA, not applicable; RRR, reduced rank regression; TNFαR2 = TNF-α receptor 2.

The RRR dietary pattern was the first factor obtained from RRR with all 36 food groups. It was then retained for subsequent analyses as the dependent variable in the stepwise linear regression analyses to identify the most important food groups contributing to this pattern (i.e., the 18 EDII components).

The food groups (including serving size per day for specific foods) retained were defined as follows: other fish [3–5 oz (70–117 g) canned tuna, shrimp, lobster, scallops, fish, or other seafood other than dark-meat fish], tomatoes [1 fresh tomato, 1 small glass of tomato juice, or 1/2 cup (115 g) tomato sauce], high-energy beverages (1 glass, 1 bottle, or 1 can cola with sugar; other carbonated beverages with sugar; or fruit punch drinks), red meat [4–6 oz (113–170 g) beef, pork, or lamb, or 1 hamburger patty], low-energy beverages (1 glass, 1 bottle, or 1 can low-energy cola; other low-energy carbonated beverages), refined grains [1 slice white bread, 1 English muffin, 1 bagel or roll, 1 muffin or biscuit, 1 cup (250 g) white rice, 1 cup (140 g) pasta, or 1 serving of pancakes or waffles], organ meat [4 oz (113 g) beef, calf, or pork liver; 1 oz (28.3 g) chicken or turkey liver], 2 slices pizza, wine [4-oz (113-g) glass red or white wine], leafy green vegetables (1/2 cup spinach, 1 serving of iceberg or head lettuce, or 1 serving of romaine or leaf lettuce), dark yellow vegetables [1/2 cup carrots, 1/2 cup yellow (winter) squash, or 1/2 cup (100 g) yams or sweet potatoes], beer (1 bottle, 1 glass, or 1 can), 1 cup coffee, fruit juices (1 small glass apple juice or cider, orange juice, grapefruit juice, or other fruit juice), snacks [1 small bag or 1 oz (28.3 g) potato chips, corn chips, or popcorn; or 1 cracker], 1 cup tea (not herbal), processed meat (1 piece or 1 slice processed meats, 2 slices bacon, or 1 hot dog), 1 pat margarine, whole fruit [1 oz or small pack raisins, 1/2 cup grapes, 1 avocado, 1 banana, 1/4 cantaloupe, 1 slice watermelon, 1 orange, 1 fresh apple or pear, 1/2 cup (112 g) canned grapefruit, 1/2 cup (100 g) strawberries or blueberries, 1 fresh or 1/2 cup (112 g) canned peaches, or 1 fresh or 1/2 cup (95 g) canned apricots or plums (1 oz = 28.3 g; 1/2 cup = 50 g)], 1 egg, and other vegetables [4-inch (10.2-cm) stick celery, 1/2 cup fresh or cooked or 1 can mushrooms, 1/2 green pepper, 1 ear or 1/2 cup (90 g) frozen or canned corn, 1/2 cup (75 g) mixed vegetables, 1 eggplant, 1/2 cup (90 g) zucchini, 1/2 cup (16 g) alfalfa sprouts, or 1/4 cucumber].

The proportion of overweight/obese participants, as well as concentrations of IL-6, CRP, TNFαR2, and the overall inflammatory marker score were higher in the most proinflammatory quintile of the EDII than in the most anti-inflammatory quintile, whereas concentrations of adiponectin were higher in quintile 1 than in quintile 5 in all 3 cohorts. Reported physical activity level in men was ≥2 times higher than in both cohorts of women; in both women and men, activity levels were highest in quintile 1 compared with quintile 5. The majority of older women were postmenopausal and more than one-half of them used postmenopausal hormones, whereas the majority of younger women were premenopausal (Table 2). In the NHS, the 5th and 95th percentiles of the RRR dietary pattern score consisting of all 39 food groups (servings per day) were −1.56 and 1.60, respectively. The EDII based on 18 food groups had similar distributions in all 3 cohorts: −0.54 to 0.41 in the NHS, −0.54 to 0.49 in the NHS-II, and −0.57 to 0.85 in the HPFS. In the NHS, the EDII was highly correlated with its potential alternative versions, with Spearman correlation coefficients ranging from 0.67 (the EDII from BMI-adjusted biomarkers) to 0.96 (RRR dietary pattern that included all 39 food groups). The EDII, its components food groups, and potential alternative versions had low to moderate correlations with biomarkers (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Participant characteristics across quintiles of the empirical dietary inflammatory index for all 3 cohorts1

| Nurses’ Health Study (n = 5230; 1986–1990) |

Nurses’ Health Study II (n = 1002; 1995–1999) |

Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (n = 2632; 1990–1994) |

|||||||

| Quintile 1(−2.27 to <−0.28) | Quintile 3(−0.12 to <0.004) | Quintile 5(0.16–1.49) | Quintile 1(−1.26 to <−0.28) | Quintile 3(−0.12 to <0.03) | Quintile 5(0.22–1.18) | Quintile 1(−2.67 to <−0.24) | Quintile 3(−0.03 to <0.17) | Quintile 5(0.41–2.08) | |

| Age, y | 57.8 ± 6.6 | 58.6 ± 6.9 | 57.4 ± 7.3 | 42.6 ± 4.3 | 41.9 ± 4.5 | 40.7 ± 4.6 | 59.1 ± 9.2 | 60.1 ± 10.7 | 62.3 ± 9.1 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.0 ± 3.8 | 25.6 ± 4.5 | 28.1 ± 5.9 | 24.3 ± 4.8 | 25.2 ± 5.7 | 27.5 ± 6.6 | 25.6 ± 3.0 | 25.7 ± 3.8 | 26.5 ± 3.5 |

| Overweight/obese (≥25 kg/m2), % | 30.7 | 46.6 | 64.6 | 31.0 | 37.5 | 57.0 | 54.9 | 53.0 | 63.7 |

| Physical activity, MET-h/wk | 17.2 ± 22.4 | 16.6 ± 23.8 | 13.3 ± 23.6 | 20.2 ± 21.3 | 16.6 ± 16.9 | 16.3 ± 22.5 | 38.4 ± 35.9 | 36.6 ± 34.1 | 33.8 ± 33.1 |

| Current smokers, % | 15.9 | 11.8 | 12.3 | 16.5 | 6.0 | 8.5 | 8.0 | 6.1 | 7.0 |

| Alcohol,2 servings/d | 0.9 ± 1.1 | 0.4 ± 0.6 | 0.2 ± 0.5 | 0.8 ± 0.9 | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 2.0 | 1.0 ± 1.3 | 0.8 ± 1.3 |

| Plasma CRP,3 mg/L | 1.2 ± 1.4 | 1.8 ± 1.5 | 2.5 ± 1.5 | 0.7 ± 1.7 | 0.8 ± 1.7 | 1.1 ± 1.7 | 0.5 ± 1.7 | 0.6 ± 1.7 | 0.7 ± 1.6 |

| Plasma CRP >3 mg/L, % | 17.3 | 27.3 | 40.4 | 13.5 | 16.5 | 22.5 | 9.1 | 11.0 | 13.1 |

| Plasma IL-6,3 pg/mL | 1.2 ± 1.1 | 1.5 ± 1.1 | 1.6 ± 1.1 | 1.0 ± 1.0 | 1.1 ± 1.0 | 1.2 ± 1.0 | 1.2 ± 1.1 | 1.3 ± 1.1 | 1.5 ± 1.1 |

| Plasma TNFαR2,3 ng/mL | 2.5 ± 0.6 | 2.5 ± 0.6 | 2.7 ± 0.6 | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 2.5 ± 0.6 | 2.7 ± 0.6 | 2.7 ± 0.6 |

| Plasma adiponectin,3 μg/mL | NA | NA | NA | 6.7 ± 0.8 | 6.7 ± 0.8 | 5.5 ± 0.8 | 7.4 ± 1.0 | 7.4 ± 1.0 | 6.7 ± 0.9 |

| Regular aspirin/NSAID users, % | 34.0 | 34.8 | 39.3 | 21.5 | 20.5 | 16.5 | 20.5 | 15.2 | 16.0 |

| Chronic diseases or conditions comorbidity score,4 % | |||||||||

| 0 chronic diseases or conditions | 50.6 | 41.6 | 35.5 | 73.5 | 72.5 | 68.0 | 43.2 | 47.0 | 40.5 |

| 1 chronic disease or condition | 31.5 | 34.0 | 34.8 | 22.0 | 23.5 | 21.5 | 32.7 | 32.1 | 33.5 |

| 2 chronic diseases or conditions | 14.7 | 17.8 | 19.3 | 4.5 | 3.5 | 7.5 | 17.1 | 13.9 | 18.4 |

| ≥3 chronic diseases or conditions | 3.3 | 6.6 | 10.4 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 3.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 7.6 |

| Postmenopausal women, % | 85.7 | 85.9 | 82.6 | 27.5 | 24.5 | 17.0 | NA | NA | NA |

| Postmenopausal hormone users, % | 55.4 | 55.0 | 51.1 | 36.5 | 38.5 | 32.5 | NA | NA | NA |

Values are means ± SDs (geometric means ± CVs for all inflammatory markers), or percentages. The Quan-Zhang formula (41), CV = (eSD − 1)1/2, was used to calculate CVs. Nurses’ Health Study, n = 1046 for each quintile; Nurses’ Health Study II, n = 200 for each quintile; Health Professionals Follow-Up Study, n = 526 for each quintile. CRP, C-reactive protein; MET-h, metabolic equivalent task hours; NA, not applicable; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; TNFαR2, TNF-α receptor 2.

Total servings per day of wine [4-oz (113.4-g) glass], beer (1 bottle, can, or glass), and liquor (1 drink or shot).

Geometric means ± CVs are presented for the biomarkers because all 4 biomarkers were log-transformed before analyses.

Chronic diseases or conditions included in the score were hypercholesterolemia, cancer, diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, and rheumatoid or other arthritis.

TABLE 3.

Spearman correlation coefficients between the EDII, its potential alternative versions, and plasma inflammatory markers in all 3 cohorts1

| EDII | CRP | IL-6 | TNFαR2 | Adiponectin | Overall inflammatory marker score2 | |

| Nurses’ Health Study (n = 5230; 1986–1990) | ||||||

| EDII | 1.00 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.15 | NA | NA |

| Unweighted EDII | 0.88 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.13 | NA | NA |

| EDII with nutrients (including supplements) | 0.90 | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.16 | NA | NA |

| EDII with nutrients (no supplements) | 0.87 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.16 | NA | NA |

| EDII from BMI-adjusted biomarkers | 0.67 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.15 | NA | NA |

| EDII in nonusers of aspirin/NSAIDs | 0.94 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.15 | NA | NA |

| EDII in control subjects | 0.91 | 0.28 | 0.22 | 0.17 | NA | NA |

| Nurses’ Health Study-II (n = 1002; 1995–1999) | ||||||

| EDII | 1.00 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.11 | −0.14 | 0.18 |

| Unweighted EDII | 0.88 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.10 | −0.10 | 0.16 |

| EDII with nutrients (including supplements) | 0.88 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.11 | −0.12 | 0.19 |

| EDII with nutrients (no supplements) | 0.84 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.09 | −0.10 | 0.17 |

| EDII from BMI-adjusted biomarkers | 0.67 | −0.01* | 0.02* | 0.06 | −0.09 | 0.06 |

| EDII in nonusers aspirin/NSAIDs | 0.94 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.14 | −0.15 | 0.19 |

| EDII in control subjects | 0.90 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.13 | −0.07* | 0.16 |

| Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (n = 2632; 1990–1994) | ||||||

| EDII | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.13 | −0.06 | 0.14 |

| Unweighted EDII | 0.89 | 0.03* | 0.07 | 0.11 | −0.09 | 0.12 |

| EDII with nutrients (including supplements) | 0.71 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.15 | −0.05 | 0.17 |

| EDII with nutrients (no supplements) | 0.73 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.12 | −0.04 | 0.14 |

| EDII from BMI-adjusted biomarkers | 0.53 | −0.002* | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.01* | 0.07 |

| EDII in nonusers aspirin/NSAIDs | 0.85 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.12 | −0.09 | 0.14 |

| EDII in control subjects | 0.87 | 0.03* | 0.06 | 0.08 | −0.05 | 0.08 |

All values are Spearman correlation coefficients, *P > 0.05. CRP, C-reactive protein; EDII, empirical dietary inflammatory index; NA, not applicable; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; TNFαR2, TNF-α receptor 2.

Computed by summing the z scores of all 4 biomarkers for each participant.

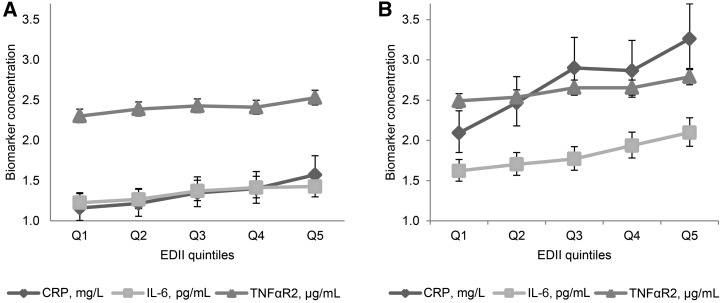

In multivariable-adjusted models in the NHS, the EDII was significantly associated with concentrations of all 3 biomarkers (IL-6, CRP, and TNFαR2) used in the development of the EDII. The tests for linear trend were significant for each biomarker across quintiles of the EDII (P-trend < 0.0001 for all biomarkers) (Table 4). In the stratified analyses, there were no significant differences in biomarker concentrations by aspirin/NSAID use (P-interaction = 0.11, 0.36, and 0.21 for IL-6, CRP, and TNFαR2, respectively). However, within each stratum of aspirin/NSAID use, there were significant trends of increasing biomarker concentrations across EDII quintiles (P-trend < 0.0001 for all biomarkers) (Figure 1).

TABLE 4.

Relative concentrations of plasma inflammatory markers across quintiles of the EDII in the Nurses’ Health Study (n = 5230)1

| Quintile 1 (−2.27 to <−0.28; most anti-inflammatory diets) | Quintile 2(−0.28 to <−0.12) | Quintile 3(−0.12 to <0.004) | Quintile 4(0.004 to <0.16) | Quintile 5 (0.16–1.49; most proinflammatory diets) | P-trend2 | |

| IL-6 | ||||||

| Age-adjusted | 1 | 1.10 (1.03, 1.17) | 1.22 (1.14, 1.30) | 1.31 (1.23, 1.40) | 1.47 (1.38, 1.58) | <0.0001 |

| Multivariable-adjusted3 | 1 | 1.09 (1.03, 1.16) | 1.20 (1.12, 1.27) | 1.25 (1.17, 1.33) | 1.36 (1.28, 1.45) | <0.0001 |

| CRP | ||||||

| Age-adjusted | 1 | 1.29 (1.16, 1.42) | 1.41 (1.28, 1.56) | 1.62 (1.46, 1.79) | 2.09 (1.89, 2.31) | <0.0001 |

| Multivariable-adjusted3 | 1 | 1.27 (1.15, 1.39) | 1.38 (1.26, 1.52) | 1.52 (1.38, 1.57) | 1.82 (1.65, 2.01) | <0.0001 |

| TNFαR2 | ||||||

| Age-adjusted | 1 | 1.03 (1.01, 1.06) | 1.05 (1.03, 1.08) | 1.09 (1.06, 1.12) | 1.14 (1.11, 1.17) | <0.0001 |

| Multivariable-adjusted3 | 1 | 1.03 (1.00, 1.06) | 1.05 (1.03, 1.08) | 1.09 (1.06, 1.11) | 1.13 (1.10, 1.16) | <0.0001 |

Values are relative concentrations (95% CIs) of biomarkers in higher EDII quintiles relative to quintile 1 as the reference quintile (e.g., the ratio of the concentration in quintile 5 to that in quintile 1), n = 1046 in each quintile. All values were back-transformed (ex) because biomarker data were ln-transformed before analyses. CRP, C-reactive protein; EDII, empirical dietary inflammatory index; TNFαR2, TNF-α receptor 2.

The P-value of the dietary index as a continuous variable adjusted for all covariates listed in footnote 3.

Adjusted for age, physical activity, smoking status, case-control status, batch effects for biomarker measurements, regular aspirin/nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, menopausal status, postmenopausal hormone use, and an inflammation-related chronic disease comorbidity score. Chronic diseases and conditions included in the score were hypercholesterolemia, cancer, diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, and rheumatoid or other arthritis.

FIGURE 1.

Adjusted mean (95% CI) plasma inflammatory marker concentrations in quintiles of the EDII in regular users (A) and nonusers (B) of aspirin/NSAIDs (Nurses’ Health Study; n = 5230; 1986–1990). Values are mean concentrations of biomarkers adjusted for age at blood draw, physical activity, smoking status, BMI, menopausal status, postmenopausal hormone use, case-control status, batch effects for biomarker measurements, and an inflammation-related chronic disease comorbidity score. Chronic diseases and conditions included in the score were hypercholesterolemia, cancer, diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, and rheumatoid or other arthritis. All tests were 2-sided and all 95% CIs were statistically significant (i.e., did not include 1). All biomarker concentrations were back-transformed (ex), and all P-trends < 0.0001. P values for the interaction of EDII and aspirin/NSAIDs were as follows: IL-6 = 0.11; CRP = 0.36; TNFαR2 = 0.21. Sample sizes in EDII quintiles were as follows—nonusers of aspirin/NSAIDs: Q1 = 668, Q2 = 669, Q3 = 669, Q4 = 669, and Q5 = 669; regular aspirin/NSAID users: Q1 = 377, Q2 = 377, Q3 = 378, Q4 = 377, and Q5 = 377. CRP, C-reactive protein; EDII, empirical dietary inflammatory index; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; Q, quintile; TNFαR2, TNF-α receptor 2.

In the validation phase with the use of NHS-II and HPFS data, the EDII was significantly associated with concentrations of all 3 biomarkers that were used in its development in the NHS, plus concentrations of adiponectin and an overall inflammatory marker score (not involved in its development). There were significant linear trends of higher concentrations of all biomarkers in EDII quintiles. For example, in the NHS-II, the relative concentrations (95% CIs) for the highest compared with the lowest EDII quintile were 0.88 (95% CI: 0.80, 0.96), P-trend = 0.003 for adiponectin and 3.18 (95% CI: 1.93, 5.26), P-trend = 0.002 for the overall inflammatory marker score. Corresponding associations in the HPFS were 0.87 (95% CI: 0.82, 0.92), P-trend < 0.0001 for adiponectin and 2.19, (95% CI: 1.70, 2.82), P-trend < 0.0001 for the overall inflammatory marker score (Tables 5 and 6).

TABLE 5.

Relative concentrations of plasma inflammatory markers across quintiles of the EDII in the Nurses’ Health Study II (n = 1002; 1995–1999)1

| Quintile 1(−1.26 to <−0.28; most anti-inflammatory diets) | Quintile 2(−0.28 to <−0.12) | Quintile 3(−0.12 to <0.03) | Quintile 4(0.03 to <0.22) | Quintile 5(0.22–1.18; most proinflammatory diets) | P-trend2 | |

| IL-6 | ||||||

| Age-adjusted | 1 | 0.97 (0.84, 1.11) | 1.07 (0.93, 1.23) | 1.09 (0.95, 1.25) | 1.24 (1.08, 1.42) | <0.0001 |

| Multivariable-adjusted3 | 1 | 0.96 (0.84, 1.09) | 1.07 (0.93, 1.22) | 1.02 (0.89, 1.18) | 1.17 (1.02, 1.34) | 0.001 |

| CRP | ||||||

| Age-adjusted | 1 | 1.22 (0.94, 1.60) | 1.21 (0.93, 1.60) | 1.36 (1.04, 1.77) | 1.74 (1.33, 2.27) | <0.0001 |

| Multivariable-adjusted3 | 1 | 1.24 (0.97, 1.60) | 1.20 (0.93, 1.54) | 1.24 (0.96, 1.60) | 1.52 (1.18, 1.97) | 0.002 |

| TNFαR2 | ||||||

| Age-adjusted | 1 | 1.02 (0.97, 1.06) | 1.04 (0.99, 1.08) | 1.06 (1.01, 1.10) | 1.10 (1.05, 1.15) | <0.0001 |

| Multivariable-adjusted3 | 1 | 1.02 (0.98, 1.07) | 1.04 (0.99, 1.09) | 1.06 (1.01, 1.10) | 1.09 (1.04, 1.14) | 0.0003 |

| Adiponectin | ||||||

| Age-adjusted | 1 | 1.01 (0.92, 1.11) | 1.01 (0.92, 1.11) | 0.93 (0.84, 1.02) | 0.83 (0.75, 0.91) | <0.0001 |

| Multivariable-adjusted3 | 1 | 1.01 (0.92, 1.11) | 1.03 (0.94, 1.13) | 0.97 (0.87, 1.07) | 0.88 (0.80, 0.96) | 0.003 |

| Overall inflammatory marker score4 | ||||||

| Age-adjusted | 1 | 1.19 (0.71, 1.99) | 1.45 (0.87, 2.43) | 2.09 (1.25, 3.50) | 4.49 (2.67, 7.54) | <0.0001 |

| Multivariable-adjusted3 | 1 | 1.18 (0.72, 1.92) | 1.39 (0.85, 2.28) | 1.62 (0.99, 2.67) | 3.18 (1.93, 5.26) | <0.0001 |

Values are relative concentrations (95% CIs) of biomarkers in higher EDII quintiles relative to quintile 1 as the reference quintile (e.g., ratio of concentration in quintile 5 to concentration in quintile 1). All values were back-transformed (ex) because biomarker data were ln-transformed before analysis. Quintile 1: n = 200, quintile 2: n = 201, quintile 3: n = 200, quintile 4: n = 201, and quintile 5: n = 200. CRP, C-reactive protein; EDII, empirical dietary inflammatory index; TNFαR2, TNF-α receptor 2.

The P value of the dietary index as a continuous variable adjusted for all covariates listed in footnote 3.

Adjusted for age, physical activity, smoking status, case-control status, batch effects for biomarker measurements, regular aspirin/nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, and an inflammation-related chronic disease comorbidity score. Chronic diseases or conditions included in the score were hypercholesterolemia, cancer, diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, and rheumatoid or other arthritis, with additional adjustment for menopausal status and postmenopausal hormone use in women.

Computed by summing the z scores of all 4 biomarkers for each participant.

TABLE 6.

Relative concentrations of plasma inflammatory markers across quintiles of the EDII in the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (n = 2632; 1990–1994)1

| Quintile 1(−2.67 to <−0.24; most anti-inflammatory diets) | Quintile 2(−0.24 to <−0.03) | Quintile 3(−0.03 to <0.17) | Quintile 4(0.17 to <0.41) | Quintile 5(0.41–2.08; most proinflammatory diets) | P-trend2 | |

| IL-6 | ||||||

| Age-adjusted | 1 | 1.13 (1.04, 1.24) | 1.10 (1.01, 1.21) | 1.15 (1.06, 1.26) | 1.14 (1.04, 1.25) | 0.01 |

| Multivariable-adjusted3 | 1 | 1.11 (1.02, 1.21) | 1.11 (1.01, 1.21) | 1.16 (1.06, 1.27) | 1.14 (1.04, 1.24) | 0.01 |

| C-reactive protein | ||||||

| Age-adjusted | 1 | 1.12 (0.94, 1.32) | 1.07 (0.90, 1.27) | 1.20 (1.01, 1.41) | 1.22 (1.03, 1.45) | 0.05 |

| Multivariable-adjusted3 | 1 | 1.15 (1.02, 1.30) | 1.19 (1.06, 1.34) | 1.22 (1.08, 1.38) | 1.23 (1.09, 1.40) | 0.002 |

| TNF-α receptor 2 | ||||||

| Age-adjusted | 1 | 1.04 (1.01, 1.07) | 1.06 (1.03, 1.09) | 1.07 (1.03, 1.09) | 1.07 (1.04, 1.11) | <0.0001 |

| Multivariable-adjusted3 | 1 | 1.03 (1.00, 1.07) | 1.06 (1.03, 1.09) | 1.05 (1.02, 1.09) | 1.07 (1.04, 1.10) | 0.0001 |

| Adiponectin | ||||||

| Age-adjusted | 1 | 1.02 (0.95, 1.10) | 1.01 (0.93, 1.09) | 0.90 (0.84, 0.98) | 0.86 (0.79, 0.92) | <0.0001 |

| Multivariable-adjusted3 | 1 | 1.00 (0.94, 1.05) | 0.97 (0.92, 1.03) | 0.91 (0.86, 0.96) | 0.87 (0.82, 0.92) | <0.0001 |

| Overall inflammatory marker score4 | ||||||

| Age-adjusted | 1 | 1.43 (1.07, 1.90) | 1.47 (1.10, 1.96) | 1.97 (1.48, 2.62) | 2.28 (1.70, 3.04) | <0.0001 |

| Multivariable-adjusted3 | 1 | 1.44 (1.12, 1.85) | 1.66 (1.29, 2.13) | 1.97 (1.53, 2.53) | 2.19 (1.70, 2.82) | <0.0001 |

Values are relative concentrations (95% CIs) of biomarkers in higher EDII quintiles relative to quintile 1 as the reference quintile (e.g., ratio of concentration in quintile 5 to concentration in quintile 1). All values were back-transformed (ex) because biomarker data were ln-transformed before analysis. Quintile 1: n = 526, quintile 2: n = 527, quintile 3: n = 526, quintile 4: n = 527, and quintile 5, n = 526. CRP, C-reactive protein; EDII, empirical dietary inflammatory index; TNFαR2, TNF-α receptor 2.

The P value of the dietary index as a continuous variable adjusted for all covariates listed in footnote 3.

Adjusted for age, physical activity, smoking status, case-control status, batch effects for biomarker measurements, regular aspirin/nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, and an inflammation-related chronic disease comorbidity score. Chronic diseases or conditions included in the score were hypercholesterolemia, cancer, diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, and rheumatoid or other arthritis, with additional adjustment for menopausal status and postmenopausal hormone use in women.

Computed by summing the z scores of all 4 biomarkers for each participant.

Associations between alternative versions of the EDII and the 4 biomarkers in sensitivity analyses in the NHS-II and HPFS are presented in Supplemental Table 3. Associations between the unweighted EDII and all biomarkers were significant although smaller in magnitude than were those obtained with the weighted EDII. The potential alternative version of the EDII that included nutrients with supplements and the version that included nutrients without supplements were both associated with concentrations of all 4 biomarkers in women and men. The EDII version derived in nonusers of aspirin/NSAIDs in the NHS and applied in nonusers of aspirin/NSAIDs in the NHS-II (n = 812) and HPFS (n = 2174) was associated with concentrations of all 4 biomarkers. The alternative version derived in control subjects in the NHS-II (n = 594) and HPFS (n = 1606) was significantly associated with concentrations of biomarkers except for IL-6, CRP, and TNFαR2 in the HPFS (Supplemental Table 3).

In the NHS, we observed stronger associations between the EDII and IL-6 and CRP in overweight/obese women than in normal-weight women (P-interaction = 0.07, 0.04, and 0.39 for IL-6, CRP, and TNFαR2, respectively), although there were significant trends of higher biomarker concentrations in both normal-weight and overweight/obese women across EDII quintiles (Figure 2 and Supplemental Table 4). In the multivariable models, associations with adjustment for BMI, although significant, were weaker than those without adjustment for BMI (data not shown). In the NHS-II and HPFS, associations were attenuated and mostly statistically nonsignificant in both women and men when the EDII was used to predict BMI-adjusted biomarkers, except for TNFαR2, adiponectin, and the overall inflammatory marker score in the HPFS (Supplemental Table 3). In the NHS-II, there was no statistical evidence for effect modification by BMI status for any biomarker except for TNFαR2 (P-interaction = 0.95, 0.58, 0.007, 0.88, and 0.60 for IL-6, CRP, TNFαR2, adiponectin, and overall inflammatory marker score, respectively). Also, in the HPFS, with 1142 normal-weight men and 1490 overweight/obese men, there was no significant effect modification by BMI (P-interaction = 0.25, 0.85, 0.17, 0.99, and 0.57 for IL-6, CRP, TNFαR2, adiponectin, and overall inflammatory marker score, respectively). However, we found stronger associations between the EDII and IL-6, CRP, and overall inflammatory marker score in normal weight men than in overweight/obese men (Supplemental Table 4).

FIGURE 2.

Adjusted mean (95% CI) plasma inflammatory marker concentrations in quintiles of the EDII in normal-weight women (BMI <25 kg/m2) (A) and overweight/obese women (BMI ≥25 kg/m2) (B) from the Nurses’ Health Study (n = 5230; 1986–1990). Values are mean concentrations of biomarkers, adjusted for age at blood draw, physical activity, smoking status, aspirin/NSAID use, menopausal status, postmenopausal hormone use, case-control status, batch effects for biomarker measurements, and an inflammation-related chronic disease comorbidity score. Chronic diseases and conditions included in the score were hypercholesterolemia, cancer, diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, and rheumatoid or other arthritis. All tests were 2-sided and all 95% CIs were statistically significant (i.e., did not include 1). All biomarker concentrations were back-transformed (ex), and all P-trends < 0.0001. P values for interaction of EDII and aspirin/NSAIDs were as follows: CRP = 0.13, IL-6 = 0.12, and TNFαR2 = 0.43. Sample sizes in EDII quintiles were as follows—normal-weight women: Q1 = 544, Q2 = 545, Q3 = 544, Q4 = 545, and Q5 = 544; overweight/obese women: Q1 = 501, Q2 = 502, Q3 = 502, Q4 = 502, and Q5 = 501. CRP, C-reactive protein, EDII, empirical dietary inflammatory index; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; Q, quintile; TNFαR2, TNF-α receptor 2.

Discussion

Using RRR and stepwise linear regression analyses in a large cohort of women, we developed a hypothesis-driven index of dietary inflammatory potential (the EDII) based on the intake of 18 food groups, and evaluated its construct validity in 2 independent cohorts of women and men. The construct validation of this index showed robust associations between the EDII and 3 plasma inflammatory markers: IL-6, CRP, and TNFαR2, and additional markers, adiponectin and an overall inflammatory marker score, which were not included in its development. These associations were also robust to several sensitivity analyses. The EDII thus may be derived in a standardized manner across different populations and used to examine associations with diseases hypothesized to have chronic inflammation as a major pathogenesis pathway. A previously developed literature-derived nutrient-based dietary inflammatory index (36), whose validity has been evaluated (38, 42), has shown strong associations with disease risk, e.g., with colorectal cancer risk (39, 43) and pancreatic cancer risk (44). Both dietary indexes assess the inflammatory potential of an individual’s diet, but differ in conception and design. Dietary patterns based on food groups, such as the EDII, are most directly related to dietary guidelines for health promotion and disease prevention.

The EDII is similar to 2 dietary patterns derived previously in the NHS by using the RRR procedure. Schulze et al. (45) used soluble TNFαR2, IL-6, CRP, E-selectin, the soluble intracellular cell adhesion molecule, and the soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 as responses in the RRR procedure to develop a dietary pattern associated with type 2 diabetes that comprised 9 food groups (all except cruciferous vegetables included in the EDII). They found positive associations between higher scores of this pattern and risk of type 2 diabetes (OR: 3.09; 95% CI: 1.99, 4.79). More recently, Lucas et al. (46) derived a similar dietary pattern with the use of CRP, IL-6, and soluble TNFαR2 as responses in the RRR procedure, and examined its association with the risk of depression in women. They identified a pattern comprising 11 food groups (all included in the EDII), which was significantly associated with risk of depression in the NHS (RR: 1.41; 95% CI: 1.22, 1.63), by comparing extreme quintiles of the dietary pattern. Unlike the previous studies, the EDII focuses on the inflammatory potential of diet more generally rather than on specific diseases, and its validity was assessed in 2 independent cohorts of women and men. In addition, we constructed several potential alternative versions of the EDII in the NHS sample, applied them in the 2 independent validation samples, and found the EDII to be robust to these alternative hypotheses.

Among the 18 EDII components, fish (other than dark-meat fish) and tomatoes were positively associated with inflammatory markers, whereas pizza was inversely related. This may likely reflect fish preparation methods, but this information was not collected. For example, well-done or browned fried, grilled, or barbecued fish may be more proinflammatory and associated with a higher risk of chronic diseases (47). The oils used for deep frying have low amounts of n–3 FAs because of the oxidation of these acids (48), and, until the regulation of trans fats in the United States, they also contained high amounts of trans fats, which are proinflammatory. Three trials investigated the effect of tomato intake on concentrations of inflammatory markers with conflicting findings (49–51). One trial found a significantly reduced concentration of adiponectin (49), but others found no effect on IL-6, CRP, and other inflammatory markers (50, 51). Indeed, at the end of the intervention, one trial reported significantly higher concentrations of inflammatory markers in the intervention group than in the control group (50). It is therefore possible that the mechanisms of the potential benefit of a tomato-rich diet may not be related directly to the inflammation process. Tomato paste contains 2.5- to 4-fold higher bioavailable lycopene than fresh tomatoes (52), and lycopene has shown anti-inflammatory properties (53), which could explain the inverse association of pizza with inflammatory markers.

The association between the inflammatory potential of diet and concentrations of inflammatory markers may be confounded by BMI, mediated through BMI, and/or modified by BMI. That is, BMI or weight gain has been associated with the quality of dietary intake (54) and with inflammatory markers (55), and it is possible also that overweight/obesity, a state of low-grade chronic inflammation (56, 57), may partly mediate the association between dietary inflammatory potential and concentrations of inflammatory markers or chronic disease outcomes. In sensitivity analyses in the NHS-II and HPFS with the EDII from BMI-adjusted biomarkers, associations with all biomarkers were attenuated, and most became nonsignificant (Supplemental Table 3), which may reflect more mediation than confounding. Adjusting for BMI (and other potential confounders) is important for etiologic purposes to identify the independent association between the inflammatory potential of diet and concentrations of inflammatory markers, but the proportion of this association mediated by BMI is important to inform the design of public health interventions. Evidence for mediation is strengthened by findings from well-designed meta-analyses that combine data from highly powered prospective studies addressing dietary determinants of long-term weight gain and randomized clinical trials evaluating the short-term effects of specific dietary factors on weight changes (58–60) . For example, replacing sugar-sweetened beverage intake with water, coffee, or tea is inversely associated with weight gain (60). In the current study, we found the same direction of association between coffee and inflammatory markers. Also, other evidence shows that weight loss leads to changes in concentrations of inflammatory markers (61, 62). In our large NHS sample, we found effect modification by BMI of the association between higher EDII scores and IL-6 and CRP concentrations, with higher concentrations in overweight/obese women than in normal-weight women, but it is not clear why there were differences between women and men. Perhaps the multiplicative effects of overweight/obesity may be more dominant than those of diet alone and thus explain the stronger associations we found in normal-weight men than overweight/obese men.

Our approach in developing the EDII in the NHS was based on the relatively large sample with inflammatory marker data. Evaluating the construct validity of the EDII in both the HPFS and NHS-II samples was done not only to avoid the statistical over-fitting of NHS data, but also to determine the association of EDII scores with concentrations of inflammatory markers in independent populations of men and women. Thus, one contribution of the current analysis is that studies that lack inflammatory marker data may derive EDII scores to investigate associations between dietary inflammatory potential and disease outcomes. The composition of food groups may not be uniform across studies, which may limit the ability to apply EDII scores across studies in a standardized manner; however, investigators may be able to create unified food groups in pooled analyses of primary data or in multicenter studies, thus enhancing the usefulness of this hypothesis-driven dietary pattern in large-scale epidemiologic research. Although the component food groups of the EDII and its potential alternative versions are not exactly the same, the correlations between these potential alternative versions and the EDII were quite strong, ranging from 0.67 to 0.94 in the NHS; 0.67 to 0.90 in the NHS-II, and 0.53 to 0.89 in the HPFS. The use of repeated dietary and covariate measures is another strength of our study design. The use of >1 measurement has been shown to reduce measurement error and also accounts for potential changes over a 4-y time period in dietary and lifestyle behavior.

Our study is not without limitations: the NHS, NHS-II, and HPFS study populations are mostly white, thus warranting the need to apply further the EDII in multiethnic/multiracial populations. Although we used repeated dietary and covariate data, we had only one measurement of the inflammatory markers that would tend to underestimate validity assessed by correlation coefficients (63). Although we adjusted for a large number of potential confounding factors, including a history of inflammation-related chronic diseases and conditions, these potential confounding factors were self-reported, allowing for the possibility of residual confounding.

To our knowledge, the EDII represents a novel hypothesis-driven dietary inflammatory index that assesses diet quality based on its inflammatory potential. Its construct validity in independent samples of women and men with the use of 4 different inflammatory markers indicates its usefulness in assessing the inflammatory potential of whole diets. In addition, the EDII may be derived in a standardized and reproducible manner across different populations, thus circumventing a major limitation of dietary patterns derived from the same study in which they are applied.

Acknowledgments

FKT and ELG designed the research; FKT conducted the research and performed the statistical analysis; SAS-W, JEC, KW, CSF, FBH, ATC, and WCW analyzed and interpreted the data and provided critical intellectual input; FKT and ELG wrote the paper; SAS-W reviewed all results for accuracy; and ELG provided study oversight and had primary responsibility for the final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: CRP, C-reactive protein; EDII, empirical dietary inflammatory index; HPFS, Health Professionals Follow-Up Study; NHS, Nurses’ Health Study; NHS-II, Nurses’ Health Study II; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; RRR, reduced rank regression; TNFαR2, TNF-α receptor 2.

References

- 1.Hu FB. Dietary pattern analysis: a new direction in nutritional epidemiology. Curr Opin Lipidol 2002;13:3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacques PF, Tucker KL. Are dietary patterns useful for understanding the role of diet in chronic disease? Am J Clin Nutr 2001;73:1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiuve SE, Fung TT, Rimm EB, Hu FB, McCullough ML, Wang M, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC. Alternative dietary indices both strongly predict risk of chronic disease. J Nutr 2012;142:1009–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Cancer Research Fund and the American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, nutrition and prevention of cancer: a global perspective 2007. Washington (DC). Report No.: 978–0-9722522–2-5.

- 5.Varraso R, Garcia-Aymerich J, Monier F, Le Moual N, De Batlle J, Miranda G, Pison C, Romieu I, Kauffmann F, Maccario J. Assessment of dietary patterns in nutritional epidemiology: principal component analysis compared with confirmatory factor analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2012;96:1079–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moeller SM, Reedy J, Millen AE, Dixon LB, Newby PK, Tucker KL, Krebs-Smith SM, Guenther PM. Dietary patterns: challenges and opportunities in dietary patterns research: an experimental biology workshop, April 1, 2006. J Am Diet Assoc 2007;107:1233–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schulze MB, Hoffmann K, Kroke A, Boeing H. An approach to construct simplified measures of dietary patterns from exploratory factor analysis. Br J Nutr 2003;89:409–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krintus M, Kozinski M, Kubica J, Sypniewska G. Critical appraisal of inflammatory markers in cardiovascular risk stratification. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 2014;51:263–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donath MY, Shoelson SE. Type 2 diabetes as an inflammatory disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2011;11:98–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guina T, Biasi F, Calfapietra S, Nano M, Poli G. Inflammatory and redox reactions in colorectal carcinogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2015;1340:95–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barbaresko J, Koch M, Schulze MB, Nöthlings U. Dietary pattern analysis and biomarkers of low-grade inflammation: a systematic literature review. Nutr Rev 2013;71:511–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fung TT, McCullough ML, Newby PK, Manson JE, Meigs JB, Rifai N, Willett WC, Hu FB. Diet-quality scores and plasma concentrations of markers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. Am J Clin Nutr 2005;82:163–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lopez-Garcia E, Schulze MB, Fung TT, Meigs JB, Rifai N, Manson JE, Hu FB. Major dietary patterns are related to plasma concentrations of markers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. Am J Clin Nutr 2004;80:1029–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wood AD, Strachan AA, Thies F, Aucott LS, Reid DM, Hardcastle AC, Mavroeidi A, Simpson WG, Duthie GG, Macdonald HM. Patterns of dietary intake and serum carotenoid and tocopherol status are associated with biomarkers of chronic low-grade systemic inflammation and cardiovascular risk. Br J Nutr 2014;112:1341–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nanri A, Moore MA, Kono S. Impact of C-reactive protein on disease risk and its relation to dietary factors: literature review. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2007;8:167–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffmann K, Schulze MB, Schienkiewitz A, Nöthlings U, Boeing H. Application of a new statistical method to derive dietary patterns in nutritional epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:935–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffmann K, Zyriax BC, Boeing H, Windler E. A dietary pattern derived to explain biomarker variation is strongly associated with the risk of coronary artery disease. Am J Clin Nutr 2004;80:633–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jankovic N, Steppel MT, Kampman E, de Groot LC, Boshuizen HC, Soedamah-Muthu SS, Kromhout D, Feskens EJ. Stability of dietary patterns assessed with reduced rank regression; the Zutphen Elderly Study. Nutr J 2014;13:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colditz GA, Hankinson SE. The Nurses’ Health Study: lifestyle and health among women. Nat Rev Cancer 2005;5:388–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pai JK, Pischon T, Ma J, Manson JE, Hankinson SE, Joshipura K, Curhan GC, Rifai N, Cannuscio CC, Stampfer MJ, et al. Inflammatory markers and the risk of coronary heart disease in men and women. N Engl J Med 2004;351:2599–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hankinson SE, Willett WC, Manson JE, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Longcope C, Speizer FE. Alcohol, height, and adiposity in relation to estrogen and prolactin levels in postmenopausal women. J Natl Cancer Inst 1995;87:1297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song M, Zhang X, Wu K, Ogino S, Fuchs CS, Giovannucci EL, Chan AT. Plasma adiponectin and soluble leptin receptor and risk of colorectal cancer: a prospective study. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2013;6:875–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan AT, Ogino S, Giovannucci EL, Fuchs CS. Inflammatory markers are associated with risk of colorectal cancer and chemopreventive response to anti-inflammatory drugs. Gastroenterology 2011;140:799–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu FB, Meigs JB, Li TY, Rifai N, Manson JE. Inflammatory markers and risk of developing type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes 2004;53:693–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pai JK, Hankinson SE, Thadhani R, Rifai N, Pischon T, Rimm EB. Moderate alcohol consumption and lower levels of inflammatory markers in US men and women. Atherosclerosis 2006;186:113–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pearson TA, Mensah GA, Alexander RW, Anderson JL, Cannon RO 3rd, Criqui M, Fadl YY, Fortmann SP, Hong Y, Myers GL, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; American Heart Association. Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: application to clinical and public health practice: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Heart Association. Circulation 2003;107:499–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Willett WC, Sampson L, Stampfer MJ, Rosner B, Bain C, Witschi J, Hennekens CH, Speizer FE. Reproducibility and validity of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. Am J Epidemiol 1985;122:51–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feskanich D, Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Litin LB, Willett WC. Reproducibility and validity of food intake measurements from a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. J Am Diet Assoc 1993;93:790–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Litin LB, Willett WC. Reproducibility and validity of an expanded self-administered semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire among male health professionals. Am J Epidemiol 1992;135:1114–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Rimm E, Ascherio A, Rosner BA, Spiegelman D, Willett WC. Dietary fat and coronary heart disease: a comparison of approaches for adjusting for total energy intake and modeling repeated dietary measurements. Am J Epidemiol 1999;149:531–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu FB, Rimm E, Smith-Warner SA, Feskanich D, Stampfer MJ, Ascherio A, Sampson L, Willett WC. Reproducibility and validity of dietary patterns assessed with a food frequency questionnaire. Am J Clin Nutr 1999;69:243–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chocano-Bedoya PO, Mirzaei F, O’Reilly EJ, Lucas M, Okereke OI, Hu FB, Rimm EB, Ascherio A. C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, soluble tumor necrosis factor α receptor 2 and incident clinical depression. J Affect Disord 2014;163:25–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Song M, Wu K, Ogino S, Fuchs CS, Giovannucci EL, Chan AT. A prospective study of plasma inflammatory markers and risk of colorectal cancer in men. Br J Cancer 2013;108:1891–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inamura K, Song M, Jung S, Nishihara R, Yamauchi M, Lochhead P, Qian ZR, Kim SA, Mima K, Sukawa Y, et al. Prediagnosis plasma adiponectin in relation to colorectal cancer risk according to KRAS mutation status. J Natl Cancer Inst 2015;108: djv363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schulze MB, Hoffmann K. Methodological approaches to study dietary patterns in relation to risk of coronary heart disease and stroke. Br J Nutr 2006;95:860–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shivappa N, Steck SE, Hurley TG, Hussey JR, Hebert JR. Designing and developing a literature-derived, population-based dietary inflammatory index. Public Health Nutr 2014;17:1689–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Willett WC, Howe GR, Kushi LH. Adjustment for total energy intake in epidemiologic studies. Am J Clin Nutr 1997;65:1220S–8S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tabung FK, Steck SE, Zhang J, Ma Y, Liese AD, Agalliu I, Hou L, Hurley TG, Hingle M, Jiao L, et al. Construct validation of the dietary inflammatory index among postmenopausal women. Ann Epidemiol 2015;25:398–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tabung FK, Steck SE, Ma Y, Liese AD, Zhang J, Caan B, Hou L, Johnson KC, Mossavar-Rahmani Y, Shivappa N, et al. The association between dietary inflammatory index and risk of colorectal cancer among postmenopausal women: results from the Women’s Health Initiative. Cancer Causes Control 2015;26:399–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tabung FK, Steck SE, Burch JB, Chen CF, Zhang H, Hurley TG, Cavicchia P, Alexander M, Shivappa N, Creek KE, et al. A healthy lifestyle index is associated with reduced risk of colorectal adenomatous polyps among non-users of non-steroidal anti-Inflammatory drugs. J Prim Prev 2015;36:21–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quan H, Zhang J. Estimate of standard deviation for a log-transformed variable using arithmetic means and standard deviations. Stat Med 2003;22:2723–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shivappa N, Steck SE, Hurley TG, Hussey JR, Ma Y, Ockene IS, Tabung FK, Hebert JR. A population-based dietary inflammatory index predicts levels of C-reactive protein in the Seasonal Variation of Blood Cholesterol Study (SEASONS). Public Health Nutr 2014;17:1825–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zamora-Ros R, Shivappa N, Steck SE, Canzian F, Landi S, Alonso MH, Hébert JR, Moreno V. Dietary inflammatory index and inflammatory gene interactions in relation to colorectal cancer risk in the Bellvitge colorectal cancer case–control study. Genes Nutr 2015;10:447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shivappa N, Bosetti C, Zucchetto A, Serraino D, La Vecchia C, Hébert JR. Dietary inflammatory index and risk of pancreatic cancer in an Italian case–control study. Br J Nutr 2015;113:292–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schulze MB, Hoffmann K, Manson JE, Willett WC, Meigs JB, Weikert C, Heidemann C, Colditz GA, Hu FB. Dietary pattern, inflammation, and incidence of type 2 diabetes in women. Am J Clin Nutr 2005;82:675–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lucas M, Chocano-Bedoya P, Shulze MB, Mirzaei F, O’Reilly ÉJ, Okereke OI, Hu FB, Willett WC, Ascherio A. Inflammatory dietary pattern and risk of depression among women. Brain Behav Immun 2014;36:46–53. Corrected and republished from: Brain Behav Immun 2015;46:327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.He K, Xun P, Brasky TM, Gammon MD, Stevens J, White E. Types of fish consumed and fish preparation methods in relation to pancreatic cancer incidence: the VITAL cohort study. Am J Epidemiol 2013;177:152–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Echarte M, Zulet MA, Astiasaran I. Oxidation process affecting fatty acids and cholesterol in fried and roasted salmon. J Agric Food Chem 2001;49:5662–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li YF, Chang YY, Huang HC, Wu YC, Yang MD, Chao PM. Tomato juice supplementation in young women reduces inflammatory adipokine levels independently of body fat reduction. Nutrition 2015;31:691–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Markovits N, Ben Amotz A, Levy Y. The effect of tomato-derived lycopene on low carotenoids and enhanced systemic inflammation and oxidation in severe obesity. Isr Med Assoc J 2009;11:598–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blum A, Monir M, Khazim K, Peleg A, Blum N. Tomato-rich (Mediterranean) diet does not modify inflammatory markers. Clin Invest Med 2007;30:E70–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gärtner C, Stahl W, Sies H. Lycopene is more bioavailable from tomato paste than from fresh tomatoes. Am J Clin Nutr 1997;66:116–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marcotorchino J, Romier B, Gouranton E, Riollet C, Gleize B, Malezet-Desmoulins C, Landrier JF. Lycopene attenuates LPS-induced TNF-α secretion in macrophages and inflammatory markers in adipocytes exposed to macrophage-conditioned media. Mol Nutr Food Res 2012;56:725–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fung TT, Pan A, Hou T, Chiuve SE, Tobias DK, Mozaffarian D, Willett WC, Hu FB. Long-term change in diet quality is associated with body weight change in men and women. J Nutr 2015;145:1850–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Strohacker K, Wing RR, McCaffery JM. Contributions of body mass index and exercise habits on inflammatory markers: a cohort study of middle-aged adults living in the USA. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Trayhurn P, Wood IS. Adipokines: inflammation and the pleiotropic role of white adipose tissue. Br J Nutr 2004;92:347–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee H, Lee IS, Choue R. Obesity, inflammation and diet. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr 2013;16:143–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Malik VS, Schulze MB, Hu FB. Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;84:274–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hu FB. Resolved: there is sufficient scientific evidence that decreasing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption will reduce the prevalence of obesity and obesity-related diseases. Obes Rev 2013;14:606–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pan A, Malik VS, Hao T, Willett WC, Mozaffarian D, Hu FB. Changes in water and beverage intake and long-term weight changes: results from three prospective cohort studies. Int J Obes (Lond) 2013;37:1378–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ruth MR, Port AM, Shah M, Bourland AC, Istfan NW, Nelson KP, Gokce N, Apovian CM. Consuming a hypocaloric high fat low carbohydrate diet for 12weeks lowers C-reactive protein, and raises serum adiponectin and high density lipoprotein-cholesterol in obese subjects. Metabolism 2013;62:1779–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Khoo J, Dhamodaran S, Chen DD, Yap SY, Chen RY, Tian HH. Exercise-induced weight loss is more effective than dieting for improving adipokine profile, insulin resistance and inflammation in obese men. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2015;25:566–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Perrier F, Giorgis-Allemand Li, Slama R, Philippat C. Within-subject pooling of biological samples to reduce exposure misclassification in biomarker-based studies. Epidemiology 2016;27:378–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]