Abstract

Purpose

Mutations in the retinal transcription factor cone-rod homeobox (CRX) gene result in severe dominant retinopathies. A large animal model, the Rdy cat, carrying a spontaneous frameshift mutation in Crx, was reported previously. The present study aimed to further understand pathogenesis in this model by thoroughly characterizing the Rdy retina.

Methods

Structural and functional changes were found in a comparison between the retinas of CrxRdy/+ kittens and those of wild-type littermates and were determined at various ages by fundus examination, electroretinography (ERG), optical coherence tomography, and histologic analyses. RNA and protein expression changes of Crx and key target genes were analyzed using quantitative reverse-transcribed PCR, Western blot analysis, and immunohistochemistry. Transcription activity of the mutant Crx was measured by a dual-luciferase transactivation assay.

Results

CrxRdy/+ kittens had no recordable cone ERGs. Rod responses were delayed in development and markedly reduced at young ages and lost by 20 weeks. Photoreceptor outer segment development was incomplete and was followed by progressive outer retinal thinning starting in the cone-rich area centralis. Expression of cone and rod Crx target genes was significantly down-regulated. The mutant Crx allele was overexpressed, leading to high levels of the mutant protein lacking transactivation activity.

Conclusions

The CrxRdy mutation exerts a dominant negative effect on wild-type Crx by overexpressing mutant protein. These findings, consistent with those of studies in a mouse model, support a conserved pathogenic mechanism for CRX frameshift mutations. The similarities between the feline eye and the human eye with the presence of a central region of high cone density makes the CrxRdy/+ cat a valuable model for preclinical testing of therapies for dominant CRX diseases.

Keywords: animal model, cat, CRX, LCA, retinopathy

Inherited retinal degenerations result in a range of different phenotypes and can be caused by mutations in a multitude of different genes (currently mutations in 240 different genes that cause inherited retinal degenerations are listed. RetNet1, https://sph.uth.edu/retnet; available in the public domain). Mutations in one of these genes, the cone-rod homeobox (CRX) gene, cause a spectrum of retinopathies that vary in severity and age of onset. These CRX-linked retinopathies are mostly dominantly inherited. Among them, Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA) is the most severe, leading to vision loss starting in childhood. The less severe forms have a later onset and can cause a variety of phenotypes including cone-rod dystrophy, retinitis pigmentosa, and adult-onset macular dystrophy.2,3 CRX is an OTX-like homeodomain transcription factor expressed in both rod and cone photoreceptors and is essential for their development, maturation, and continued survival.4–7 CRX interacts with subtype-specific transcription factors to control rod-versus-cone specification during development and directly regulates many genes essential for normal retinal function, including key components of the phototransduction cascade and the CRX gene itself.8,9 CRX binds to regulatory sequences of target genes and interacts with cofactors to influence transcription levels.6,10–13 It has a homeodomain near the N terminus that mediates DNA binding6,14 and two transactivation domains in the C-terminal portion for activating target gene transcription.14

Disease-causing CRX mutations can be grouped into four classes based on the mutation type and functional characteristic of the resulting mutant protein.3 Among them, Class III mutations consist of frameshift and nonsense mutations causing truncations of the protein affecting the transactivation domains. The C-terminal truncated forms of CRX maintain DNA binding but lack transcriptional activation function and thus have an antimorphic effect.2,3,15,16 All identified Class III mutations are linked to autosomal dominant LCA or early onset severe cone-rod dystrophy. To understand the pathogenesis of the Class III mutations, a knock-in mouse model, Crx-E168d2, has been generated.15 The 2-bp deletion at the E168 codon (Glu168del2) is equivalent to a human CRX-LCA mutation.15,17 The heterozygous E168d2 mouse develops severe retinopathy, similar to that in CRX-LCA, and has been used to complete a detailed investigation of the disease mechanism.15 This investigation revealed that the mutant allele is overexpressed and interferes with the function of the wild-type (WT) allele. Although we have learned a great deal from this mouse model, it has certain limitations. First, the mouse retina differs from the human retina in photoreceptor distribution, particularly in the cone mosaic patterns.18–22 Humans have a macula, a central retinal region of higher photoreceptor density, particularly of cones, including a central cone-only foveola. This macula region is responsible for high-acuity color vision. The lack of an equivalent retinal region in the mouse is especially problematic for a disease primarily affecting cones at early stages. Second, it is unclear whether the pathogenic mechanisms learned from this singular animal model are conserved among mammalian species, including humans.

To overcome the above limitations, we carried out an in-depth characterization of a feline model, the rod-cone dysplasia (Rdy) cat, which has a dominantly inherited, severe retinal dystrophy23–27 due to a 1-bp deletion in Crx (p.A182d1).28 The frameshift mutation leads to a premature stop codon at the 185th residue with loss of the last 114 amino acids, eliminating the region of Crx that is presumed to mediate transactivation. Several human CRX retinopathies, most frequently classified as LCA, are due to frameshift mutations causing a stop codon at the same position (see Table 2 in Tran et al.3) (Supplementary Fig. S1).29–38 The Rdy cat is a valuable model for CRX-LCA because cats have an area centralis, a region of higher photoreceptor density, enriched with cones, which has strong similarities to human macula.39–41 Although the phenotype of the heterozygous Rdy cat (CrxRdy/+) has been partially characterized,23–26 the dynamics of disease progression and underlying molecular changes have not been investigated. The current study addresses this knowledge gap by providing a detailed investigation of the progression of functional, cellular, and molecular phenotypes of the CrxRdy/+cat. The mutant cat shows incomplete photoreceptor maturation with cones more severely affected than rods, followed by a progressive cone-led photoreceptor degeneration, starting in the cone-rich area centralis. This phenotype is more accurately classified at an early onset, severe cone-rod dystrophy (rather than a rod-cone dystrophy as originally described) that mimics CRX-LCA. Similar to the E168d2 mouse model, the CrxRdy/+cat retina undergoes significant biochemical and molecular changes before and during disease progression. More strikingly, the mutant Crx allele produces much more mRNA and protein than the WT allele, supporting across-species conservation of the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying Class III CRX mutation-mediated blinding disease. The CrxRdy/+ cat provides an excellent large animal model of CRX-LCA and will be invaluable for the preclinical testing of treatment strategies.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

All procedures were performed in accordance with the ARVO statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and approved by the Michigan State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Animals

Purpose-bred CrxRdy cats maintained as a colony at Michigan State University were used in this study. They were housed under 12L:12D cycles and fed a commercial feline dry diet (Purina One Smartblend and Purina kitten chow; Nestlé Purina, St. Louis, MO, USA). Animals ranging from 4 weeks to 1 year of age were studied.

Ophthalmic Examination and Fundus Imaging

Full ophthalmic examinations included indirect ophthalmoscopy, fundus photography (Ret-Cam II; Clarity Medical Systems, Inc., Pleasanton, CA, USA), and imaging using confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (Spectralis OCT+HRA; Heidelberg Engineering, Inc., Heidelberg, Germany).

Electroretinography (ERG)

The kittens were dark-adapted for 1 hour, and pupils were dilated with tropicamide ophthalmic solution, UPS 1% (Falcon Pharmaceuticals, Ltd., Fort Worth, TX, USA). Anesthesia was induced and, following intubation, maintained with isoflurane (IsoFlo; Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL, USA). A Burian-Allen bipolar electrode contact lens (Burian-Allen ERG electrode; Hansen Ophthalmic Development Lab, Coralville, IA, USA) was used, and a platinum needle skin electrode placed over the occiput was used for grounding (Grass Technologies, Warwick, RI, USA). ERGs were recorded using an Espion E2 electrophysiology system with ColorDome Ganzfeld (Diagnosys LLC, Lowell, MA, USA). A dark-adapted luminance-response series (−4.5 to 1.4 log cd.s/m2), followed by light adaptation (10 minutes exposure to a 30 cd/m2 white light), and a light-adapted series (−2.4 to 1.4 log cd.s/m2) and 33- Hz cone flicker (−0.4 log cd.s/m2) were recorded. ERG a- and b-wave amplitudes and implicit times were measured in a standard fashion.

The leading edge of the rod a-wave was fitted to the Birch and Hood42 version of the Lamb and Pugh rod phototransduction model by using the following equation:

|

The amplitude R is a function of the retinal luminance, I, and time, t, after the flash, and td is a brief delay. S is the sensitivity factor, and Rmax is the maximum amplitude of the response.

The first limb of the dark-adapted b-wave luminance:amplitude plot was fitted to the Naka-Rushton equation to derive values for retinal sensitivity (K is semisaturation constant, the luminance, L, that induces a response amplitude of ½Rmax).43

|

where Rmax represents the maximum response amplitude of the first limb of the b-wave luminance:response plot, the K is a semisaturation constant, considered a measurement of retinal sensitivity, and n is a factor of the slope of the plot at the position of K, suggested to indicate retinal homogeneity.

Retinal Morphology

In Vivo Spectral Domain - Optical Coherence Tomography (SD-OCT).

SD-OCT imaging (Heidelberg Engineering) was used to capture single-scan line and volume scan images from the central retina to include the area centralis and from the four retinal quadrants (4 optic nerve head distances from the edge of the optic nerve head superiorly, inferiorly, nasally, and temporally as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S2). Thicknesses of the total retinal and outer nuclear layers (ONL) and receptor+ (including layers between retinal pigmentary epithelium and outer plexiform layer44) and the inner retinal layers between the inner nuclear layer and internal limiting membrane were measured.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC).

After cats were euthanized, their eyes were removed and immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscope Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO, USA) on ice for 2 to 3.25 hours. They were then processed for immunohistochemistry and imaged as previously described45 (Supplementary Table S1 lists the antibodies used).

Plastic-Embedded Sections.

Eyes were fixed in a 3% glutaraldehyde, 2% paraformaldehyde solution (Electron Microscope Sciences) in 0.1 M PBS pH 7.4 (Sigma-Aldrich Corp.) on ice for 1 hour, then hemisectioned, and the posterior eyecups were placed in the same fixative overnight. Following rinsing in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, samples from the dorsal, central, and ventral retinal regions were dissected, embedded in 2% agarose gel, 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, and then embedded in resin (SPURR; low-viscosity embedding kit; Electron Microscope Sciences).46 Five hundred-nanometer sections were stained using epoxy tissue stain (Electron Microscope Sciences).

Quantitative Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

Two retinal regions (central and peripheral) from 2-week-old kittens were dissected (Supplementary Fig. S3A); in older animals samples were collected from five areas (superior far-periphery, superior mid-periphery, central [area centralis], inferior mid-periphery, inferior far-periphery [Supplementary Fig. S3B]). Samples were flash frozen and stored at −80°C until RNA extraction. RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and qRT-PCR reactions were performed as previously described.15 Levels of arrestin3 (Arr3, specific to cones), rhodopsin (Rho, specific to rods), and total Crx (WT and mutant) mRNA were measured and normalized to those of tubulin alpha-1B chain (Tuba1b) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; for primer sequences, see Supplementary Table S2).

Due to the difficulty of establishing a qRT-PCR assay to differentially amplify mutant and WT Crx cDNA a PCR restriction enzyme assay was developed to estimate the mutant-to-WT Crx mRNA ratio. Total combined Crx cDNA was amplified (forward primer, 5′-cgtggccacggtgcccatct-3′ reverse primer 5′-tccaggccactgaaatagga-3′), followed by HpaII digestion (BioLabs, Inc., Ipswich, MA, USA). The mutant Crx amplicon (189 bp) is not cut by HpaII, whereas the WT is (112- and 78-bp products). Following electrophoresis using 2% agarose gel, the bands were imaged and quantified, and the mutant amplicon-to-WT amplicon ratio was calculated (Image Lab version 5.2.1. software; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). A control using known WT-to-mutant Crx PCR product ratios generated from plasmid-cloned WT and mutant feline Crx was included to verify the accuracy of the technique.

Western Blot Assay

Retina tissue remaining after samples for qRT-PCR were dissected was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°. Protein extraction from nuclear versus cytoplasmic fractions and Western blot assay were performed as previously described.15 Monoclonal mouse anti-β-actin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich Corp.) and polyclonal rabbit anti-CRX 119b115 at 1:1000 dilution were used to probe the membranes. Secondary antibodies were goat anti-mouse IRDye 680LT and goat anti-rabbit IRDye 800CW (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA), respectively. Fluorescence was detected by using an Odyssey infrared imager (LI-COR Biosciences) and quantified by using ImageJ software (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/; provided in the public domain by the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).47

Dual-Luciferase Assay

Dual-luciferase assays were performed as previously described.15 HEK293 cells (catalog ATCC CRL-11268; American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) were cultured in Dulbecco minimum essential medium (Gibco, Life technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/mL; Gibco, Life technologies). Cells at 60% confluence were transfected with 2 μg of mCrx-Luc reporter, which carries 500 bp of the mouse Crx promoter driving firefly luciferase in the pGL3 vector (Promega Corp., Madison, WI, USA) and 100 ng of pcDNA3.1hisc, 100 ng of pCAGIG-feline Crx WT or 100 ng of pCAGIG-feline CrxRdy, using CaCl2 (0.25 M) and boric acid-buffered saline (1×), pH 6.75, as previously described.15 Cells were harvested 48 hours post transfection, and dual-luciferase assays were run.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses of ERG, SD-OCT, cDNA levels, Western blots, and fluorescence level data differences were tested for normality (Shapiro-Wilk test for normality). Normally distributed data were analyzed by using unpaired 2-tailed Student's t-tests (significance level set at P < 0.05), nonparametric data by a Mann-Whitney rank sum U-test (SigmaPlot version 12.0 software; Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis of mRNA levels (using qRT-PCR) was carried out using a 2-way repeat measure ANOVA (Holm-Sidak parametric method and Shapiro-Wilk normality test) (SigmaPlot 12.0; Systat Software).

Results

CrxRdy/+ Kittens Have Markedly Reduced Retinal Function

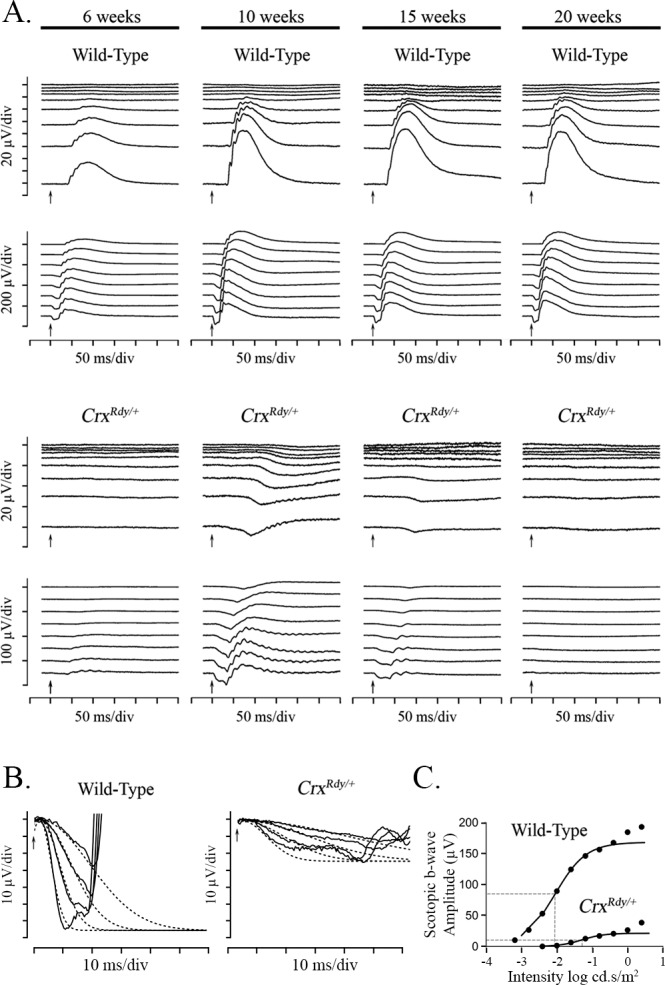

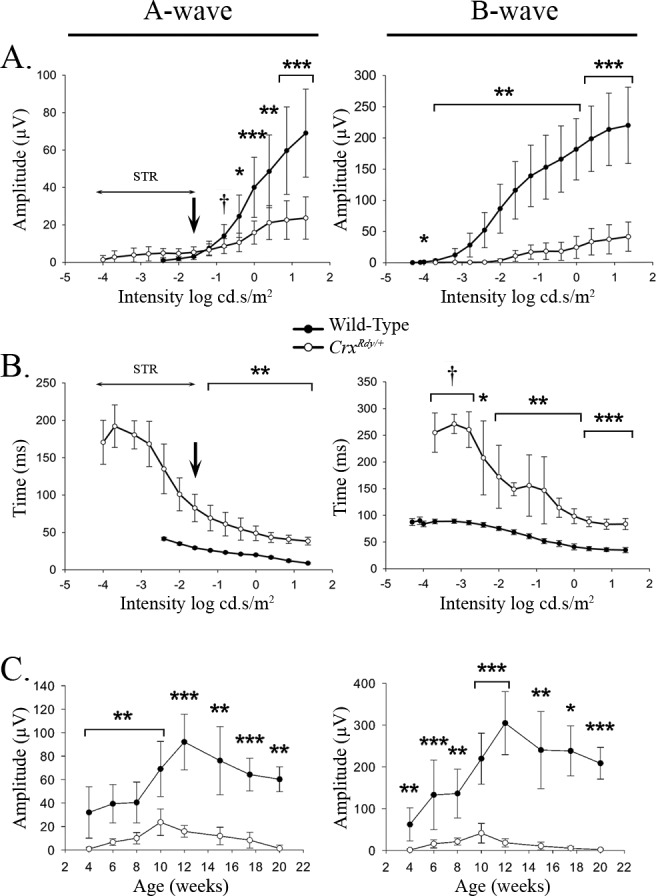

To examine the progression of functional changes in CrxRdy/+ kittens, ERGs were recorded at multiple time points from 4 to 20 weeks of age (n = 4–8) and compared with those of WT littermate controls (n = 3–7). Light-adapted ERGs could not be recorded from CrxRdy/+ kittens at any time point. Small dark-adapted responses were recordable and showed that the CrxRdy/+ kittens had severely reduced retinal function (Figs. 1, 2). At 4 weeks, a very low amplitude negative waveform typical of a scotopic threshold response (STR) was recordable from CrxRdy/+ kittens, whereas the waveform of WT kittens was similar in shape to that of adult cats (data not shown). By 6 weeks of age the CrxRdy/+ kittens had very small a- and b-wave responses. Interestingly, responses continued to develop through 10 weeks of age, although they were very reduced compared to those in the WT (WT kitten ERGs had peak amplitudes at 12 weeks of age). After peaking at 10 weeks of age, responses progressively declined until the ERG was unrecordable at approximately 20 weeks of age (Figs. 1A, 2C). At peak retinal function (10 weeks of age), the a-wave of CrxRdy/+ kittens had a threshold similar to that of WT kittens, although the relatively prominent STR made precise identification of the a-wave threshold difficult (Figs. 1A, 2A). However, compared to the peak WT controls, the peak mean maximum a-wave amplitude was significantly reduced and delayed, at only ∼30% of the mean control amplitude (P = 0.002) and with a mean implicit time approximately 2.5 to 4.5 times longer, depending on the stimulus strength (P < 0.001–0.003) (Figs. 1A, 1B, 2B, 2C). Although the a-wave of the CrxRdy/+ kitten was very reduced, it was still possible to fit the leading edge of the response at 10 weeks of age to the Birch-Hood model to assess rod phototransduction. This showed a significant decrease in Rmax in the CrxRdy/+ kittens compared to that in WT kittens (−23.86 ± 10.34 compared to −64.76 ± 25.87 μV, respectively; P = 0.003). The sensitivity log S of the response was also significantly decreased in the CrxRdy/+ kittens (0.54 ± 0.23 compared to 1.27 ± 0.12 log td−1 · s−3 (scotopic troland-seconds) in WT kittens; P < 0.001) (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Dark-adapted luminance series ERG from CrxRdy/+ and WT kittens, a-wave modeling and b-wave Naka-Ruston fitting. (A) Representative dark-adapted luminance series ERG from CrxRdy/+ and WT kittens at 6, 10, 15, and 20 weeks of age. Flash stimuli ranged from −4.5 (top) to 1.4 (bottom) log cd.s/m2. The CrxRdy/+ kitten has very reduced (note scale differences) and delayed a- and b-waves. Oscillatory potentials were present on the b-wave of the CrxRdy/+ kitten ERG. Note the relatively large STR in the CrxRdy/+ kitten, which remains prominent to higher flash luminances than normal; the developing a-wave becoming superimposed on it. A- and b-wave thresholds occurred at similar flash luminances in contrast to those of the WT, where b-wave threshold occurred at a much lower stimulus strength than the a-wave threshold. (B) Modeling of the leading edge of the rod-isolated ERG a-wave of a representative CrxRdy/+ and a WT kitten at 10 weeks of age. The raw a-waves (solid lines) and fitted curves (dashed lines) for four flash stimuli ranging from 0 to 1.4 log cd.s/m2. Note the CrxRdy/+ kitten rod photoreceptor Rmax (maximum receptor response) is much lower than that of the WT kitten. (C) Naka-Rushton fitting of the first limb of the dark-adapted b-wave luminance:response plot of a representative CrxRdy/+ and WT kitten at 10 weeks of age. The raw b-wave data values are shown by round symbols and the Naka-Rushton fit by solid lines. ½Rmax of each waveform is represented by the horizontal dashed lines, and the luminance required to elicit a response of ½Rmax (the semisaturation constant k) is indicated by the vertical dashed lines. Note the semisaturation constant k of the CrxRdy/+ kitten is elevated by approximately 0.8 log units compared to that of the WT, and the Rmax (maximum amplitude of the first limb of the b-wave luminance amplitude plot) is very reduced.

Figure 2.

A-wave and b-wave amplitude and implicit time plotted relative to flash luminance (A, B) and maximal recorded amplitude plotted relative to age (C). (A) Dark-adapted a- and b-wave luminance-response plots from 10-week-old WT and CrxRdy/+ kittens (the age at which maximum amplitudes were recordable from the CrxRdy/+ kittens). Note the CrxRdy/+ kittens had markedly reduced a- and b-wave amplitudes. The a-wave threshold was masked by the STR in the CrxRdy/+ kittens (Fig. 1A). Therefore, the negative component of the waveform at intensities lower than that indicated by the arrow in the figure consisted of the STR then with increasing intensities a combination of STR and a-wave. At intensities greater than −1.6 log cd.s/m2, the a-wave was clearly discernible. The b-wave threshold was elevated by ∼2 log units in CrxRdy/+ kittens. (B) Dark-adapted STR, a- and b-wave luminance:implicit time plots from 10-week-old WT and CrxRdy/+ kittens. Note the increased implicit times for the CrxRdy/+ kittens for both a- and b-waves. The implicit times (left plot) at intensities below that indicated by the arrow represent that of the STR. (C) A-wave and b-wave maximum amplitudes:age plots. The increase in ERG waveforms reflects retinal maturation. Peak amplitudes were recorded at 10 weeks of age for the CrxRdy/+ kitten compare to 12 weeks of age for WT kittens. By 20 weeks of age the CrxRdy/+ ERG was almost extinguished. †P ≤ 0.1; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; and ***P < 0.001 (n = 3 to 8).

The b-wave of the CrxRdy/+ kitten was even more severely decreased in amplitude than the a-wave and was also delayed. At 10 weeks of age, compared to that in WT controls, the b-wave response threshold was elevated by approximately 1.5 to 2 log units, and the mean maximum amplitude was only ∼20% that of controls (P < 0.001), and implicit times were 2 to 3 times longer (P < 0.001–0.071, respectively) (Figs. 1A, 2). Naka-Rushton fittings were performed in CrxRdy/+ kittens (n = 7) and WT control kittens (n = 6) at 10 weeks of age to derive values for the Rmax, the semisaturation constant k, and the slope factor n. All three factors were significantly different between CrxRdy/+ kittens and WT controls. The mean Rmax was much lower in CrxRdy/+ kittens (20.1 ± 14.7 compared with 169.3 ± 52.5 μV in controls; P = 0.001), indicating reduced retinal function. The mean n factor was increased, suggesting a reduction in the homogeneity of the retinal response (2.3 ± 1.98 compared to 0.91 ± 0.08, respectively; P = 0.035). Finally, the mean luminance required to induce a response of ½Rmax was significantly increased (0.027 ± 0.013 compared to 0.008 ± 0.003 cd.s/m2, respectively; P = 0.033), indicating decreased retinal sensitivity. This ∼0.5 log unit increase in stimulus luminance required to induce a response of ½Rmax was less than the increase in response threshold for the dark-adapted b-wave (1.5–2 log units) (Fig. 1C).

CrxRdy/+ Kittens Have a Progressive Photoreceptor Degeneration Starting in the Area Centralis

To determine how photoreceptor degeneration evolved in CrxRdy/+ kittens, in vivo ophthalmic imaging was performed at multiple time points from 6 weeks to 1 year of age. Ophthalmoscopic examinations revealed tapetal hyperreflectivity in CrxRdy/+ kittens (an indication of retinal thinning) in the area centralis from 7 weeks of age. Generalized tapetal hyperreflectivity and superficial retinal blood vessel attenuation was apparent from as early as 20 weeks of age (Fig. 3).

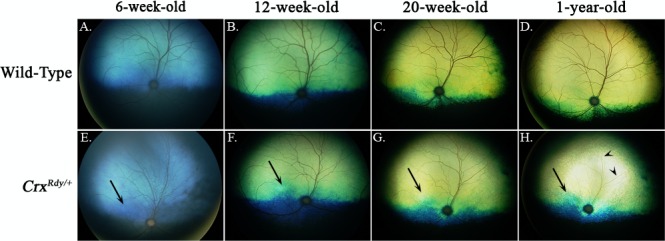

Figure 3.

Color fundus views showing progression of fundus changes in CrxRdy/+ kittens from 6 weeks to 1 year of age ([E–H] right eye shown) are compared to those of WT kittens (A–D). The CrxRdy/+ kitten developed tapetal hyperreflectivity (indicative of retinal thinning) in the area centralis (high photoreceptor density region [arrows]) as first seen in the image at 12 weeks of age. Hyperreflectivity of the entire tapetal fundus was discernible from 20 weeks of age and had progressed by 1 year of age. Superficial retinal blood vessel attenuation developed ([H] remaining very attenuated superficial retinal blood vessels are indicated by arrowheads.

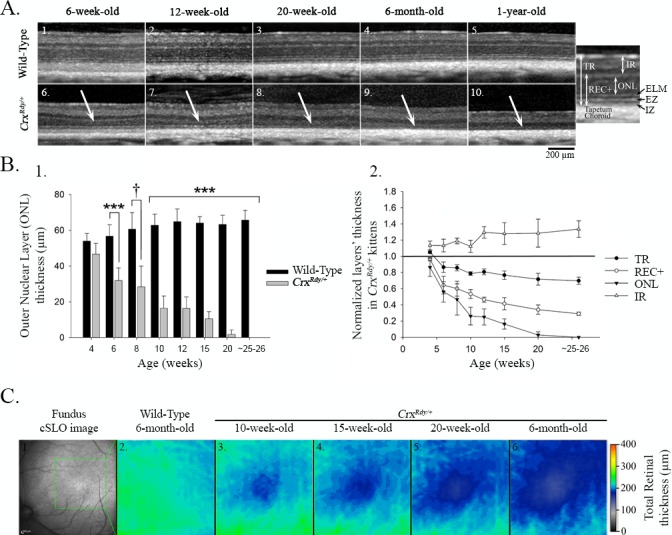

Retinal SD-OCT cross-sectional images were recorded from 4 to 26 weeks of age (n = 3–8 for CrxRdy/+ kittens and n = 2–8 for WT littermate controls). The first abnormality detected in the CrxRdy/+ kittens was a halt in the maturation of the zone on the SD-OCT image that corresponded to the photoreceptor inner and outer segments (IS/OS). This was followed by a progressive thinning of the outer retinal layers starting in the area centralis (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. S4. The SD-OCT image of layers representing inner and outer segments was thinner than in controls, and the bands that comprised the interdigitation and ellipsoid zones48 could not be discerned in the CrxRdy/+ kittens. In WT kittens, these zones became clearly visible as the retina matured (typically they could be seen easily by 6 weeks of age [Fig. 4A, top]). In the CrxRdy/+ kittens, there was further progressive thinning of the IS/OS until it disappeared as the entire outer retina progressively thinned (Fig. 4A, lower panel). The lamination of the rest of the retina on SD-OCT imaging initially appeared normal, and at 4 weeks of age, CrxRdy/+ and WT kittens had comparable ONL thicknesses in the area centralis (Fig. 4B). Thereafter a progressive outer retinal thinning occurred starting in the area centralis and eventually spreading to involve the peripheral retina (the heat map in Fig. 4C illustrates the more severe retinal thinning in the area centralis). Despite developing some retinal function, by 6 weeks of age, the ONL was significantly thinned in the region of the area centralis (Figs. 4A, 4B), and by 12 weeks of age, it was reduced to ∼25% the thickness of that in the WT kitten (P < 0.001) (Figs. 4A, 4B). The REC+ layer (which approximates the entire length of the photoreceptors, i.e., the synaptic termini, cell bodies, and IS/OS) was reduced by ∼50% by 12 weeks of age (P < 0.001) (Figs. 4A, 4B). The thinning of the outer retinal layers progressed, and by 26 weeks of age, the ONL in the area centralis was no longer discernible (Figs. 4A, 4B). As the outer retina thinned, the inner retina initially thickened, such that by 12 weeks the inner retina of the CrxRdy/+ kittens was ∼30% greater than that of controls in the area centralis region (P < 0.001), whereas due to the severe thinning of the outer retina, the total retinal thickness had decreased to ∼80% of normal (P < 0.001) (Figs. 4B, 4C). Similar retinal changes developed in the four retinal quadrants between 10 and 20 weeks of age (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Figure 4.

Spectral Domain - Optical Coherence Tomography (SD-OCT) in vivo retinal morphology analysis. (A) SD-OCT cross-section views of the retina in the region of the area centralis of representative WT (1–5) and CrxRdy/+ (6–10) cats at 6, 12, and 20 weeks, 6 months, and 1 year of age. The white arrows indicate the outer nuclear layer (ONL), which progressively thinned in the area centralis region of CrxRdy/+ cats. Note, specific features of the SD-OCT image including photoreceptor ellipsoid zone (EZ) and interdigitation zone (IZ) boundaries were not discernible in the CrxRdy/+ kittens. The magnified image of an OCT image from a WT retina on the right indicates the layers that were measured. TR, total retina; REC+, receptor plus, which includes all layers from the interdigitation zone to the outer plexiform layer (OPL), representing the entire photoreceptor cell length; ONL, outer nuclear layer; IR, inner retina, including all layers from the inner nuclear layer to the external limiting membrane. (B) Thickness of retinal layers in the area centralis. 1. ONL thickness in area centralis of CrxRdy/+ and WT kittens at 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 15, and 20 weeks and at 6 months of age. Significant ONL thinning was apparent at 6 weeks of age with a decrease of ∼50% normal thickness between 7 and 10 weeks of age in CrxRdy/+ kittens. By 6 months of age, the ONL was no longer apparent. †P ≤ 0.1; ***P < 0.001 (n = 2–8). 2. TR, REC+, ONL, and IR layer thicknesses in the area centralis of CrxRdy/+ kittens normalized to those of controls at 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 15, and 20 weeks and at 6 months of age. ONL, REC+, and TR thicknesses were decreased in CrxRdy/+ kittens from 6 weeks of age. In contrast, the IR became significantly thicker in CrxRdy/+ kittens compared to those in WT kittens. Those differences were statistically significant from 10 weeks of age (P < 0.001 for ONL, REC+, and TR; P = 0.008 for IR). (C) Total retinal thickness map in the area centralis. The region of the area centralis indicated on the confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscopy image (1) is represented as a color heat map (the optic nerve head is on the left lower). Warmer colors represent thicker retina, whereas cooler colors are thinner retina. Although the WT kittens had a relatively homogenous retinal thickness in this region at 6 months of age (2), the CrxRdy/+ kittens showed progressive thinning in the center of the area centralis, with severe thinning by 6 months of age (3–6). The color map also demonstrates that, in both WT and CrxRdy/+ kittens, the retina is thicker in the region of retinal vessels and thinner toward the periphery (top left).

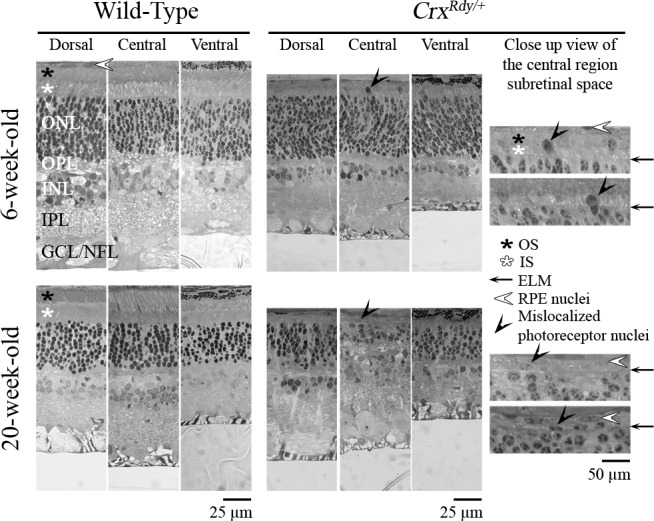

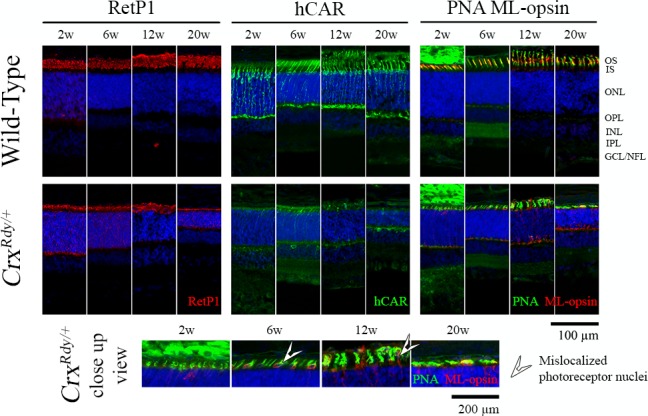

Examination of plastic-embedded semithin sections revealed that the maturation of the shape of CrxRdy/+ photoreceptor nuclei appeared delayed; at 6 weeks of age, they still had a spindle shape typical of the immature photoreceptor, whereas in WT kittens, they had gained a mature, round shape by this age (Fig. 5). Also at this age mislocalized photoreceptor nuclei could be seen in the subretinal space in the central region of the CrxRdy/+ kittens (Figs. 5, 6). These mislocalized photoreceptor nuclei were positive for ML-opsin (medium/long wavelength-opsin) immunolabeling (Fig. 6). Compared to the well-developed WT photoreceptor OS, those of CrxRdy/+ kittens were much shorter and were disorganized. Those defects worsened with age, and by 20 weeks, OS were no longer apparent (Figs. 5, 6).

Figure 5.

Representative plastic sections of retina from central, dorsal, and ventral regions in WT and CrxRdy/+ kittens at 6 and 20 weeks of age. Note that mislocalized photoreceptor nuclei ([black arrowheads] see magnified views) were present in the subretinal space or bulging through the ELM of the central region of the CrxRdy/+ retina at both ages. ONL, outer nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; GCL/NFL, ganglion cell layer/nerve fiber layer; white star, photoreceptor IS; black star, photoreceptor OS; black arrow, external limiting membrane (ELM); white arrowhead, retinal pigmentary epithelium (RPE) nuclei.

Figure 6.

Immunohistochemistry using rod and cone markers. Frozen sections from the dorsotemporal retinal region of CrxRdy/+ kittens and WT controls at the indicated ages were immunostained with rhodopsin (RetP1), cone arrestin (hCAR), and medium/long wavelength-opsin (ML-opsin) along with the pan cone marker peanut agglutinin (PNA). The higher magnification views of CrxRdy/+ sections (bottom row) show mislocalization of ML-opsin to the inner segments, cell bodies, and pedicles of the cones (white arrowheads). ONL, outer nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; GCL/ NFL, ganglion cell layer/nerve fiber layer; white arrowhead, mislocalized photoreceptor nuclei.

To further investigate rod versus cone subcellular structural changes, immunolabeling of key photoreceptor structural and phototransduction proteins was performed using frozen retinal sections (Fig. 6, Supplementary Fig. S5, Supplementary Table S1). At 2 weeks of age, CrxRdy/+ kittens had minimal human cone arrestin (hCAR) signals (hCAR labels both cone types) compared to the WT kittens (Fig. 6). By 6 weeks of age, a reduced number of hCAR-labeled cones (compared to those in WT controls) were detectable, but they had very short, stunted OS as well as shorter IS. At 12 weeks of age, although cones in the WT retina appeared mature, CrxRdy/+ retinas showed a severe loss of cones, and the remaining cones had severely shortened IS/OS. By 20 weeks of age, there were very few remaining cones. Short wave length cones were more severely affected than medium and long wave cones. At 2 weeks of age, S-opsin (short wavelength-opsin) labeling of a few cone cell bodies and OPL synaptic terminals could be seen in some animals, but no S-opsin immunolabeling was detected at 6, 12, and 20 weeks of age (Supplementary Fig. S5). Apart from the few S-opsin-positive cones at 2 weeks of age, the remaining cones were ML-opsin-positive (Fig. 6). Occasional stunted ML-opsin-labeled OS were present, but most labeling was of the stunted IS, cell bodies, and synaptic terminals, indicative of mislocalization (in WT controls, ML-opsin only labeled the OS) (Fig. 6, Supplementary Fig. S5).

CrxRdy/+ retinas had reduced labeling for rod opsin (RetP1, Fig. 6). Rod OS did start to develop, but this was halted prior to maturation and was followed by a progressive degeneration such that by 20 weeks of age they were markedly atrophied in all retinal regions. Parallel with the failure of rod maturation, mislocalization of rod opsin to the inner segments, cell body, and synaptic terminal occurred and was present at all ages tested.

Immunolabeling for rod bipolar cells (using an anti-PKCalpha antibody) showed apparently normal numbers of rod bipolar cells at the ages examined, but their dendrites were retracted from an early age (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Immunolabeling for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) was markedly increased by 12 weeks of age, indicative of extensive Müller cell activation (Supplementary Fig. S5).49–51

CrxRdy/+ Retinas Had Markedly Reduced Levels of Cone and Rod Transcripts

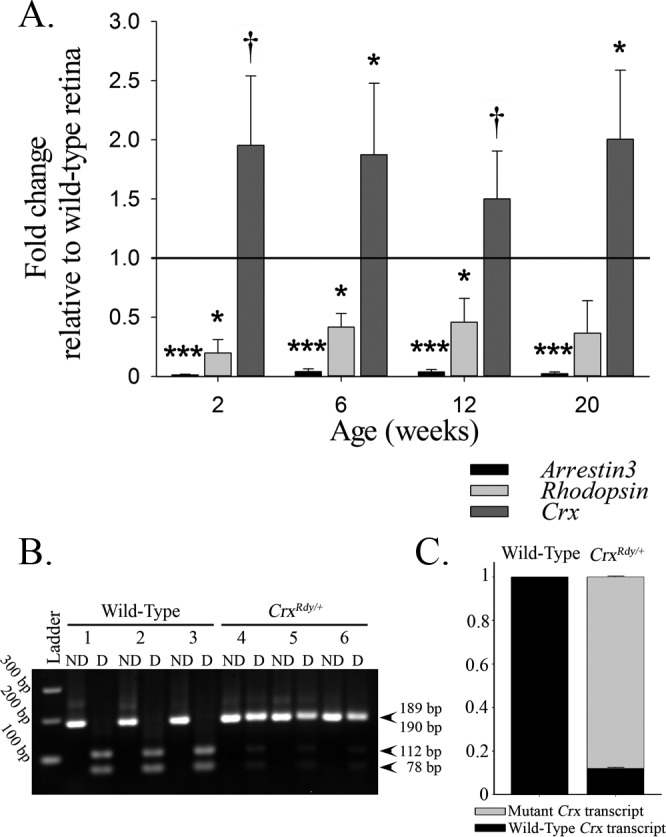

To decipher the molecular changes underlying CrxRdy/+ retinal pathology, we investigated mRNA levels of selected CRX target genes, cone arrestin (arrestin3 [Arr3]), rhodopsin (Rho, specific to rods), and total Crx (mutant plus WT) (Fig. 7, Supplementary Table S2) in retinal subregions (Supplementary Fig. S3). For all retinal regions at the four ages tested (2, 6, 12, and 20 weeks of age), mRNA levels for Arr3 and Rho in the CrxRdy/+ kittens were significantly decreased. Arr3 was more dramatically decreased (between 93% and 99%) than Rho (between 31% and 81%). There were no consistent differences in the mRNA levels between the different retinal regions tested. In contrast, Crx mRNA was overexpressed in the CrxRdy/+ kittens compared to WT controls (between 9% and 185%). For the average of all retinal regions, the difference was significant at 6 and 20 weeks of age (P = 0.037 and 0.038, respectively) (Fig. 7A); however, these differences did not achieve statistical significance for every retinal region tested at each age. More importantly, when allele-specific expression levels for the mutant versus WT allele were assessed, a significantly higher level of mutant Crx transcript than WT Crx transcript was detected (P < 0.001) (Figs. 7B, 7C), with a ratio of 7.4 ± 0.4 times the amount of mutant transcript in WT transcript at 6 weeks of age.

Figure 7.

Changes of mRNA expression in CrxRdy/+ retinas. (A) qRT-PCR overall (average of the areas assessed) mRNA expression levels of arrestin3 (Arr3 = cone arrestin), rhodopsin (Rho), and Crx in CrxRdy/+ retina at 2, 6, 12, and 20 weeks of age relative to levels in WT retinas. The CrxRdy/+ kitten retinas had significantly decreased levels of cone and rod opsin mRNA. In contrast, the expression of total Crx was significantly increased. P values comparing the mean CrxRdy/+ and WT expression levels are †P ≤ 0.1, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 (n = 3). (B, C) PCR restriction enzyme digest was used to compare the levels of mutant mRNA to those of WT mRNA by using cDNA from 6-week-old CrxRdy/+ and WT retinas. (B) Agarose gel of PCR nondigested (ND) and digested (D) products digested with HpaII, which digests the amplicon from WT cDNA. Note the presence of both the mutant Crx transcript (189 bp) and the WT Crx transcript (digested in two products of 78 and 112 bp) in the CrxRdy/+ kitten retina (kittens 4, 5, and 6). The WT kitten retina contains only WT Crx transcript (completely digested in kittens 1, 2, and 3). (C) Wild type-to-mutant Crx transcript level ratios in WT and CrxRdy/+ kittens. Densitometry measurements of the bands in the agarose gel ([B] mutant 189 bp and sum of WT transcript digested products 78 and 112 bp) from the CrxRdy/+ kitten retinas were assessed. In 6-week-old CrxRdy/+ kitten, the mutant-to-WT Crx transcript ratio was ∼7.4:1 (mutant transcripts represent 88% of the total transcript; P < 0.001). As expected in WT kittens, the WT transcript represents 100% of the total Crx mRNA.

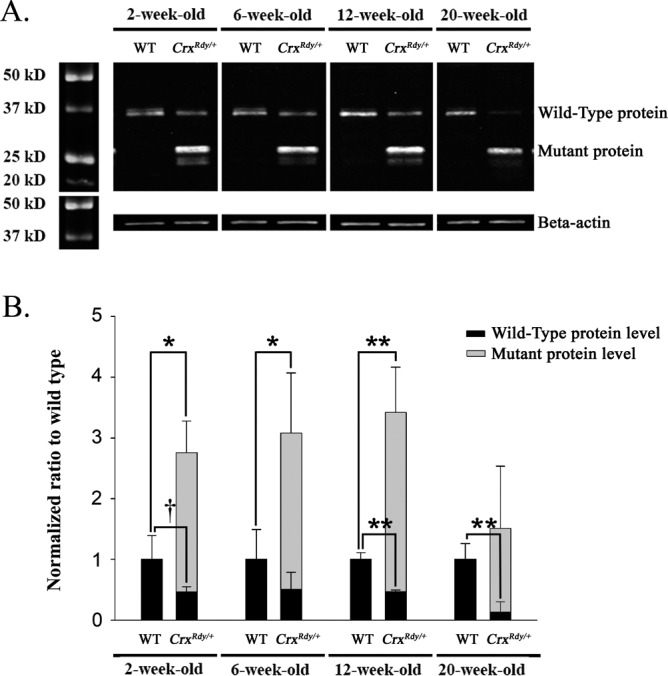

This allele-specific overexpression of the mutant product was confirmed by Western blot assays (Fig. 8). The mutant Crx protein was at higher levels than the WT Crx protein in the CrxRdy/+ retinas at each time point (Fig. 8B). The mutant protein was able to enter the nucleus as indicated by the results of Western blotting of separated retinal nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions (Supplementary Fig. S6). As anticipated for a heterozygous animal, the amount of WT Crx protein was lower in the CrxRdy/+ kittens than in WT and the difference was significant at 12 and 20 weeks of age (P < 0.01) (Fig. 8B). Because of the overproduction of the truncated mutant protein, the level of the combined Crx proteins was markedly higher in the CrxRdy/+ kittens compared to WT kittens at 2, 6, and 12 weeks of age but not at 20 weeks of age (an age at which photoreceptor degeneration was well established).

Figure 8.

Western blot analysis for Crx nuclear protein. (A) Western blot analysis of nuclear Crx protein (immunolabeled with antibody 119b1). The amount of Crx protein present in retinal nuclear extract was investigated by Western blot analysis from kittens at 2, 6, 12, and 20 weeks of age. Note the presence in the CrxRdy/+ kitten's retina of the truncated mutant Crx protein, which persisted to the 20-week-old time point, whereas the amount of WT protein had decreased by 20 weeks of age. Beta-actin was used as protein loading control. (B) Normal and mutant protein levels in CrxRdy/+ and WT kittens. Crx protein levels were normalized to beta-actin levels, and the CrxRdy/+ kitten protein levels are shown normalized to the Crx levels in the WT retinas. The level of normal protein was lower in the CrxRdy/+ kitten retina than in WT kittens at each age. Note high levels of the truncated mutant Crx protein compared to the amount of normal protein in CrxRdy/+ kitten retina and therefore the overall higher total Crx protein levels (normal plus mutant) in CrxRdy/+ kitten retina compared to WT kitten retina. †P ≤ 0.1; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 (n = 2 to 4; statistical analysis was applied only when n ≥ 3 for both the WT and the CrxRdy/+ kitten retina sample).

Effect of the Rdy Mutation on Crx's Transcription Regulatory Activity

To determine whether the Rdy mutation altered Crx function, we measured the ability of recombinant Crx proteins to activate the target gene promoter Crx, driving a luciferase reporter in HEK293 cells. This dual-luciferase reporter assay revealed that the mutant Crx protein failed to activate the Crx promoter (P = 0.729), whereas the WT protein led to significant activation (P < 0.001). (Supplementary Fig. S7), confirming that this Class III Crx mutation eliminated transactivation function.

Discussion

This study expanded on previous studies showing that the CrxRdy/+ cat has a severe, early onset, dominantly inherited retinal degeneration.24–27 Similar to other Class III CRX mutation models, overexpression of the mutant transcript occurs and most likely exerts a dominant negative effect. These findings support previous studies in mouse models that suggest a therapeutic approach by which early intervention to increase the normal-to-mutant CRX transcript ratios could lessen the disease severity in CRX-LCA patients.3,15 The CrxRdy/+ cat enables characterization of the early changes that occur in retinal regions of high cone density, which model the environment within the human macula. Such investigations are not possible in mouse models because mice lack the retinal regional differences in photoreceptor distribution and density of the human retina. The cat will be invaluable for preclinical testing of therapies to rescue photoreceptors in this region that is so critical for human visual function.

CrxRdy/+ Kitten Provides a Model for Human CRX- LCA Phenotype

CrxRdy/+ kittens show incomplete maturation of photoreceptors associated with reduced expression of photoreceptor transcripts and followed by progressive photoreceptor degeneration. Despite the importance of CRX as a transcription factor, the retina in the CrxRdy/+ kitten develops relatively normal stratification (Figs. 4, 5, 6, Supplementary Fig. S5). Cone nuclei do become aligned to form a single layer in the outer most row of the ONL, similar to the WT kittens, although from an early stage, some become mislocalized to the subretinal space, particularly in the area centralis. In the p.E168d2 mouse model of Class III CRX mutations, retinal stratification also develops normally, but in contrast to the cat model, more extensive mislocalization of cone nuclei to the inner portions of the ONL occurs.15 The photoreceptor nuclei in the CrxRdy/+ kittens retain an immature oval shape because they are delayed in attaining the adult circular appearance in retinal sections, reflecting incomplete photoreceptor maturation (Figs. 5, 6, Supplementary Fig. S5). Similarly, only partial development of IS and OS occurs. Cones are more severely affected than rods, with cone function not being recordable by ERG at any age and photoreceptor degeneration developing most rapidly in the area centralis, the region of highest cone density.39,41 Expression of the cone proteins investigated (cone arrestin by qRT-PCR and IHC, and cone opsins by IHC) was much reduced, more so than that of rod opsin (qRT-PCR and IHC). S-opsin positive cones were only detectable in some kittens at 2 weeks of age and at no other ages, showing the most severe effects were on the S-cones. The ML-cones remained present for longer but only developed very stunted outer segments which did not show expression of ML-opsin. The reduced amounts of ML-opsin present were mislocalized to other parts of the cell (Fig. 6, Supplementary Fig. S5).

Rod photoreceptors showed evidence of maturing further than cones. Although outer segments were stunted there was rod opsin present, although expression levels were much reduced. Rod function was recordable by ERG and showed evidence of maturation to 10 weeks of age prior to a rapid decline thereafter (Figs. 1A, 2C). Leon et al.26 had previously performed a detailed electrophysiological study on the Rdy cat but needed to use intravitreal recording, or to perform testing on ex vivo retinal pieces, to reliably record responses and overcome background electrical noise present when using corneal electrodes. In the current study it was possible to record very small ERGs using corneal contact lens electrodes without resorting to invasive methods. This probably reflects improvements in recording techniques rather than a drift in phenotype over the ∼25 years since the study by Leon et al.26 Similar to that study, a negative waveform ERG waveform was recorded to lower stimuli strengths in our study. The shape and timing of this waveform are in keeping with it representing an inner retinal component of the ERG present close to response threshold, the STR.52 A- and b-wave components of the ERG developed later in age than in WT cats reflecting the delay and only partial nature of rod photoreceptor maturation. They were much reduced in amplitude and showed delayed timing. Modeling of the leading edge of the rod a-wave showed a significant decrease in maximum amplitude response Rmax and sensitivity log S (Fig. 1B). This reflects the reduced rod outer segment length and low rod opsin levels in the affected cats. In the normal dark-adapted cat ERG the b-wave appears with increasing strength of stimuli initially superimposed on the STR and as its amplitude increases obscures it. In the CrxRdy/+ cat the appearance of the b-wave with increasing stimulus strength was more severely delayed than that of the a-wave meaning the a-wave became superimposed on the STR prior to the development of the b-wave. These findings of a more severe delay and suppression of the b-wave compared to the a-wave may reflect an altered maturation of rod bipolar cells which are the origin of the rod ERG b-wave.53 CRX is expressed in developing bipolar cells,54 so it is conceivable that impaired bipolar cell maturation may be a cause for the more severe changes in the b-wave than the a-wave. An electron microscopy study of Rdy cats previously reported an early reduction in the number of rod spherules and cone pedicles,25 and synaptophysin (a synaptic vesicle protein) immunolabeling was reported to be reduced in another study.27 PKCalpha immunolabeling of rod bipolar cells in this study did not reveal an alteration in numbers of labeled cells early in the disease process although an early retraction of dendrites was noted. Inner retinal components of the ERG such as the STR and oscillatory potentials which would require bipolar cell signal transmission were present and relatively prominent in the very small ERG responses from the CrxRdy/+ kittens.

Naka-Rushton fitting of the rod b-wave luminance:amplitude plots showed very reduced values for the receptor response and also for retinal sensitivity (Fig. 1C). There was an increase in the n value, which is a component reflective of the slope of the plot at the point of ½Rmax and has been suggested to reflect a less homogeneous retinal response55 and may reflect the regional variation in the rapidity of photoreceptor degeneration.

Of the nine reported human disease causing CRX frameshift mutations that result in a transcript shortened to 185 residues (as in the CrxRdy cat) (Supplementary Fig. S1), eight were reported to result in an LCA phenotype.29–38 ERG results were reported from patients representing seven of the nine mutations (Supplementary Fig. S1) (see Table 2 in Tran et al.3). ERGs were not recordable from infants when tested for three of the mutations.29,34,36,56 When tested in older children and adults the ERG was also reported to be nonrecordable,32,35,37,38 with the exception of one patient reported by Koenekoop et al.36 who had a p.A177d1 mutation. This patient had a nonrecordable ERG at 8 months of age, then as a child had some improvement in vision and a recordable cone ERG when tested at both 10 and 11 years of age. This is the only instance in the literature where improvement in visual function was noted in a CRX-LCA patient. It seems likely that this was due to some degree of delayed retinal maturation occurring prior to photoreceptor degeneration. Development of the small ERG responses in the CrxRdy cat are delayed and there is some evidence of rod maturation but unlike the human patient, cone function was not recordable and cones deteriorated prior to rods.

Following the halting of photoreceptor development in the CrxRdy/+ kitten, a rapid cone-led loss in photoreceptors occurs, resulting in outer retinal thinning starting in the area centralis (Fig. 4). With disease progression, outer retinal thinning in the more peripheral retinal regions also developed (Supplementary Fig. S4). The initial thickening of the inner retina detected on SD-OCT imaging, may be due to neuronal remodeling and glial activation as commonly seen in models of retinal degeneration57 (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Molecular Mechanism Underlying CrxRdy Phenotype and Implications in Therapy Development

The CrxRdy mutation results in a premature stop codon in the transactivation domain of Crx28 the mutant transcript escapes nonsense-mediated decay and as shown in this study is overexpressed (Fig. 7). Studies of other Class III CRX mutations have also shown that there is mutant allele overexpression (human CRX-LCA p.I138d1 mutation, truncation at codon 185, and the p.E168d2 knock-in mouse model, truncation at codon 171).15,16,29 The elevation of CrxRdy transcript levels may be the result of increased synthesis or decreased degradation of the mutant mRNA. Class III mutation-introduced premature stop codons could enhance RNA stability of the mutant allele over its WT counterpart. A feedback regulatory mechanism to decrease Crx transcripts when overexpressed could attribute to the reduction of WT Crx transcripts, while mutant allele transcript is resistant to this regulation. Further studies are required to ascertain the precise mechanism involved. In the CrxRdy/+ kitten the mutant transcript and protein remained at elevated levels even when photoreceptor degeneration was well established and the levels of expression of the WT allele were very reduced (Figs. 7, 8). This continued overexpression of mutant Crx despite photoreceptor loss has not been previously demonstrated in similar models. Similar to findings in the p.E168d2 knock-in mouse model, the truncated feline CrxRdy protein fails to activate its own promoter in vitro (Supplementary Fig. S7) thus showing across-species conservation of the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying Class III CRX mutations.

Prior to loss of photoreceptors potential therapeutic interventions that address the overexpression of the mutant Crx transcript may be translatable to human patients. These include either knocking down the levels of mutant transcript using, for example, anti-sense oligonucleotides,58–60 or shRNA,61–63 or overexpressing the WT transcript by gene supplementation using adeno-associated viral vectors,64–67 or a combination of both approaches. Supporting evidence for this approach is provided by a line of E168d2 mice where a Neo cassette was not excised (E168d2neo) resulting in lowered expression of the truncated Crx protein and a much milder phenotype than in the line of E168d2 mice where the Neo cassette had been excised.15 Also, mice or humans heterozygous for null mutations in CRX have either a mild phenotype or no phenotype indicating that severe phenotypes are not the result of simple haploinsufficiency and supporting the hypothesis of a dominant negative effect of the mutant protein.5,7

To summarize, the CrxRdy/+ cat provides a large animal model for the severe dominant CRX mutations associated with overexpression of a mutant transcript with an antimorphic effect resulting in a LCA phenotype. The area centralis is affected earliest and degenerates prior to the peripheral retina. Presence of the area centralis allows the assessment of therapeutic interventions aiming to rescue function in this critical retinal region meaning the CrxRdy cat has a valuable advantage over mouse models. The slow inner retinal degeneration in the face of photoreceptor loss and complete blindness will also make this an excellent model for testing optogenetic approaches to provide visual function by expression of light-sensitive proteins in bipolar or ganglion cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Cheryl Craft for donating the hCAR antibody, Nate Pasmanter for help with analyzing the ERG a-wave leading edges, and Hui Wang for constructing feline Crx expression vectors.

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grants EY012543 and EY025272-01A1 (SC), EY002687 (P30 Core Grant) (Washington University Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences [WU-DOVS]), EY013360 (T32 Predoctoral Training Grant) (WU), unrestricted funds from Research to Prevent Blindness (WU-DOVS), Foundation Fighting Blindness (SC), Hope for Vision (SC), George H. Bird and “Casper” Endowment for Feline Initiatives (LMO and SMPJ), Michigan State University Center for Feline Health and Well-Being (LMO and SMPJ), and Myers-Dunlap Endowment (SMPJ).

Disclosure: L.M. Occelli, None; N.M. Tran, None; K. Narfström, None; S. Chen, None; S.M. Petersen-Jones, None

References

- 1. Daiger SP,, Rossiter BJF,, Greenberg J,, Christoffels A,, Hide W. Data services and software for identifying genes and mutations causing retinal degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998. ; 39: S295. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hull S,, Arno G,, Plagnol V,, et al. The phenotypic variability of retinal dystrophies associated with mutations in CRX, with report of a novel macular dystrophy phenotype. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014. ; 55: 6934–6944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tran NM,, Chen S. Mechanisms of blindness: animal models provide insight into distinct CRX-associated retinopathies. Dev Dyn. 2014. ; 243: 1153–1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chau KY,, Chen S,, Zack DJ,, Ono SJ. Functional domains of the cone-rod homeobox (CRX) transcription factor. J Biol Chem. 2000. ; 275: 37264–37270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Morrow EM,, Furukawa T,, Raviola E,, Cepko CL. Synaptogenesis and outer segment formation are perturbed in the neural retina of Crx mutant mice. BMC Neurosci. 2005. ; 6: 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen S,, Wang QL,, Nie Z,, et al. Crx, a novel Otx-like paired-homeodomain protein, binds to and transactivates photoreceptor cell-specific genes. Neuron. 1997. ; 19: 1017–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Furukawa T,, Morrow EM,, Cepko CL. Crx, a novel otx-like homeobox gene, shows photoreceptor-specific expression and regulates photoreceptor differentiation. Cell. 1997. ; 91: 531–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hennig AK,, Peng GH,, Chen S. Regulation of photoreceptor gene expression by Crx-associated transcription factor network. Brain Res. 2008. ; 1192: 114–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Peng GH,, Chen S. Crx activates opsin transcription by recruiting HAT-containing co-activators and promoting histone acetylation. Hum Mol Genet. 2007. ; 16: 2433–2452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Corbo JC,, Lawrence KA,, Karlstetter M,, et al. CRX ChIP-seq reveals the cis-regulatory architecture of mouse photoreceptors. Genome Res. 2010. ; 20: 1512–1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Livesey FJ,, Furukawa T,, Steffen MA,, Church GM,, Cepko CL. Microarray analysis of the transcriptional network controlled by the photoreceptor homeobox gene Crx. Curr Biol. 2000. ; 10: 301–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Blackshaw S,, Fraioli RE,, Furukawa T,, Cepko CL. Comprehensive analysis of photoreceptor gene expression and the identification of candidate retinal disease genes. Cell. 2001. ; 107: 579–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hsiau TH,, Diaconu C,, Myers CA,, Lee J,, Cepko CL,, Corbo JC. The cis-regulatory logic of the mammalian photoreceptor transcriptional network. PLoS One. 2007. ; 2: e643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen S,, Wang QL,, Xu S,, et al. Functional analysis of cone-rod homeobox (CRX) mutations associated with retinal dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2002. ; 11: 873–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tran NM,, Zhang A,, Zhang X,, Huecker JB,, Hennig AK,, Chen S. Mechanistically distinct mouse models for CRX-associated retinopathy. PLoS Genet. 2014; 10: e1004111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Terrell D,, Xie B,, Workman M,, et al. OTX2 and CRX rescue overlapping and photoreceptor-specific functions in the Drosophila eye. Dev Dyn. 2012; 241: 215–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Freund CL,, Wang QL,, Chen S,, et al. De novo mutations in the CRX homeobox gene associated with Leber congenital amaurosis. Nat Genet. 1998. ; 18: 311–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Applebury ML,, Antoch MP,, Baxter LC,, et al. The murine cone photoreceptor: a single cone type expresses both S and M opsins with retinal spatial patterning. Neuron. 2000. ; 27: 513–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Provis JM,, Dubis AM,, Maddess T,, Carroll J. Adaptation of the central retina for high acuity vision: cones the fovea and the avascular zone. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2013. ; 35: 63–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rossi EA,, Roorda A. The relationship between visual resolution and cone spacing in the human fovea. Nat Neurosci. 2010. ; 13: 156–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Volland S,, Esteve-Rudd J,, Hoo J,, Yee C,, Williams DS. A comparison of some organizational characteristics of the mouse central retina and the human macula. PLoS One. 2015. ; 10: e0125631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jeon CJ,, Strettoi E,, Masland RH. The major cell populations of the mouse retina. J Neurosci. 1998. ; 18: 8936–8946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Barnett KC,, Curtis R. Autosomal dominant progressive retinal atrophy in the Abyssinian cat. J Hered. 1985. ; 76: 168–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Curtis R,, Barnett KC,, Leon A. An early-onset retinal dystrophy with dominant inheritance in the Abyssinian cat. Clinical and pathological findings. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1987. ; 28: 131–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Leon A,, Curtis R. Autosomal dominant rod-cone dysplasia in the Rdy cat. 1. Light and electron microscopic findings. Exp Eye Res. 1990. ; 51: 361–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Leon A,, Hussain AA,, Curtis R. Autosomal dominant rod-cone dysplasia in the Rdy cat. 2. Electrophysiological findings. Exp Eye Res. 1991. ; 53: 489–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chong NH,, Alexander RA,, Barnett KC,, Bird AC,, Luthert PJ. An immunohistochemical study of an autosomal dominant feline rod/cone dysplasia (Rdy cats). Exp Eye Res. 1999. ; 68: 51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Menotti-Raymond M,, Deckman KH,, David V,, Myrkalo J,, O'Brien SJ,, Narfstrom K. Mutation discovered in a feline model of human congenital retinal blinding disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010. ; 51: 2852–2859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nichols LL,, II, Alur RP,, Boobalan E,, et al. Two novel CRX mutant proteins causing autosomal dominant Leber congenital amaurosis interact differently with NRL. Hum Mutat. 2010. ; 31: E1472–E1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stone EM. Leber congenital amaurosis—a model for efficient genetic testing of heterogeneous disorders: LXIV Edward Jackson Memorial Lecture. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007. ; 144: 791–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wang P,, Guo X,, Zhang Q. Further evidence of autosomal-dominant Leber congenital amaurosis caused by heterozygous CRX mutation. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2007. ; 245: 1401–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ziviello C,, Simonelli F,, Testa F,, et al. Molecular genetics of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa (ADRP): a comprehensive study of 43 Italian families. J Med Genet. 2005. ; 42: e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Freund CL,, Gregory-Evans CY,, Furukawa T,, et al. Cone-rod dystrophy due to mutation in a novel photoreceptor-specific homeobox gene (CRX) essential for maintenance of the photoreceptor. Cell. 1997. ; 91: 543–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Perrault I,, Hanein S,, Gerber S,, et al. Evidence of autosomal dominant Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA) underlain by a CRX heterozygous null allele. J Med Genet. 2003. ; 40: e90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nakamura M,, Ito S,, Miyake Y. Novel de novo mutation in CRX gene in a Japanese patient with Leber congenital amaurosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002; 134: 465–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Koenekoop RK,, Loyer M,, Dembinska O,, Beneish R. Visual improvement in Leber congenital amaurosis and the CRX genotype. Ophthalmic Genet. 2002. ; 23: 49–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhang Q,, Li S,, Guo X,, et al. Screening for CRX gene mutations in Chinese patients with Leber congenital amaurosis and mutational phenotype. Ophthalmic Genet. 2001. ; 22: 89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zou X,, Yao F,, Liang X,, et al. De novo mutations in the cone-rod homeobox gene associated with Leber congenital amaurosis in Chinese patients. Ophthalmic Genet. 2015. ; 36: 21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Steinberg RH,, Reid M,, Lacy PL. The distribution of rods and cones in the retina of the cat (Felis domesticus). J Comp Neurol. 1973; 148: 229–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rapaport DH,, Stone J. The area centralis of the retina in the cat and other mammals: focal point for function and development of the visual system. Neuroscience. 1984. ; 11: 289–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Linberg KA,, Lewis GP,, Shaaw C,, Rex TS,, Fisher SK. Distribution of S- and M-cones in normal and experimentally detached cat retina. J Comp Neurol. 2001. ; 430: 343–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hood DC,, Birch DG. Light adaptation of human rod receptors: the leading edge of the human a-wave and models of rod receptor activity. Vision Res. 1993. ; 33: 1605–1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Evans LS,, Peachey NS,, Marchese AL. Comparison of three methods of estimating the parameters of the Naka-Rushton equation. Doc Ophthalmol. 1993. ; 84: 19–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hood DC,, Lin CE,, Lazow MA,, Locke KG,, Zhang X,, Birch DG. Thickness of receptor and post-receptor retinal layers in patients with retinitis pigmentosa measured with frequency-domain optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009. ; 50: 2328–2336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mowat FM,, Gornik KR,, Dinculescu A,, et al. Tyrosine capsid-mutant AAV vectors for gene delivery to the canine retina from a subretinal or intravitreal approach. Gene Ther. 2014. ; 21: 96–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Spurr AR. A low-viscosity epoxy resin embedding medium for electron microscopy. J Ultrastruct Res. 1969. ; 26: 31–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Schneider CA,, Rasband WS,, Eliceiri KWNIH. Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012. ; 9: 671–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Staurenghi G,, Sadda S,, Chakravarthy U,, Spaide RF;, International Nomenclature for Optical Coherence Tomography Panel. Proposed lexicon for anatomic landmarks in normal posterior segment spectral-domain optical coherence tomography: the IN·OCT consensus. Ophthalmology. 2014; 121: 1572–1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ekström P,, Sanyal S,, Narfström K,, Chader GJ,, van Veen T. Accumulation of glial fibrillary acidic protein in Müller radial glia during retinal degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1988. ; 29: 1363–1371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Linberg KA,, Fariss RN,, Heckenlively JR,, Farber DB,, Fisher SK. Morphological characterization of the retinal degeneration in three strains of mice carrying the rd-3 mutation. Vis Neurosci. 2005. ; 22: 721–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sarthy PV,, Fu M. Transcriptional activation of an intermediate filament protein gene in mice with retinal dystrophy. DNA. 1989. ; 8: 437–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sieving PA,, Frishman LJ,, Steinberg RH. Scotopic threshold response of proximal retina in cat. J Neurophysiol. 1986. ; 56: 1049–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Stockton RA,, Slaughter MM. B-wave of the electroretinogram. A reflection of ON bipolar cell activity. J Gen Physiol. 1989. ; 93: 101–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Glubrecht DD,, Kim JH,, Russell L,, Bamforth JS,, Godbout R,, Differential CRX. and OTX2 expression in human retina and retinoblastoma. J Neurochem. 2009. ; 111: 250–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Massof RW,, Wu L,, Finkelstein D,, Perry C,, Starr SJ,, Johnson MA. Properties of electroretinographic intensity-response functions in retinitis pigmentosa. Doc Ophthalmol. 1984. ; 57: 279–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Koenekoop RK. An overview of Leber congenital amaurosis: a model to understand human retinal development. Surv Ophthalmol. 2004. ; 49: 379–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhao TT,, Tian CY,, Yin ZQ. Activation of Müller cells occurs during retinal degeneration in RCS rats. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010. ; 664: 575–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ostergaard ME,, Southwell AL,, Kordasiewicz H,, et al. Rational design of antisense oligonucleotides targeting single nucleotide polymorphisms for potent and allele selective suppression of mutant Huntingtin in the CNS. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013. ; 41: 9634–9650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bennett CF,, Swayze EE. RNA targeting therapeutics: molecular mechanisms of antisense oligonucleotides as a therapeutic platform. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010. ; 50: 259–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Singh J,, Kaur H,, Kaushik A,, Peer SA. Review of antisense therapeutic interventions for molecular biological targets in various diseases. Int J Pharmacol. 2011; 7: 294–315. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Liao Y,, Tang L. Inducible RNAi system and its application in novel therapeutics. Crit Rev Biotech. 2016; 36: 630–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lambeth LS,, Smith CA. Short hairpin RNA-mediated gene silencing. Methods Mol Biol. 2013. ; 942: 205–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Rayburn ER, Antisense, Zhang R. RNAi, and gene silencing strategies for therapy: mission possible or impossible? Drug Discov Today. 2008; 13: 513–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Day TP,, Byrne LC,, Schaffer DV,, Flannery JG. Advances in AAV vector development for gene therapy in the retina. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014. ; 801: 687–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. McClements ME,, MacLaren RE. Gene therapy for retinal disease. Trans Res. 2013. ; 161: 241–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kotterman MA,, Schaffer DV. Engineering adeno-associated viruses for clinical gene therapy. Nat Rev Genet. 2014. ; 15: 445–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Dalkara D,, Sahel JA. Gene therapy for inherited retinal degenerations. C R Biol. 2014. ; 337: 185–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.