Abstract

Among over 5 million people in the USA with dementia, neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) are almost universal, occurring across disease etiology and stage. If untreated, NPS can lead to significant morbidity and mortality including increased cost, distress, depression, and faster disease progression, as well as heightened burden on families. With few pharmacological solutions, , identifying nonpharmacologic strategies is critical. We describe a randomized clinical trial, the Dementia Behavior Study, to test the efficacy of an activity program to reduce significant existing NPS and associated caregiver burden at 3 and 6 months compared to a control group intervention. Occupational therapists deliver 8 in-home sessions over 3 months to assess capabilities and interests of persons with dementia, home environments, and caregiver knowledge, and readiness from which activities are developed and families trained in their use. Families learn to modify activities for future declines and use strategies to address care challenges. The comparison group controls for time and attention and involves 8 in-home sessions delivered by health educators who provide dementia education, home safety recommendations, and advanced care planning. We are randomizing 250 racially diverse families (person with dementia and primary caregiver dyads) recruited from community-based social services, conferences and media announcements. The primary outcome is change in agitation/aggression at 3 and 6 months. Secondary outcomes assess quality of life of persons with dementia, other behaviors, burden and confidence of caregivers, and cost effectiveness. If benefits are supported, this activity intervention will provide a clinically meaningful approach to prevent, reduce, and manage NPS.

Keywords: dementia, neuropsychological behaviors, family caregiving, activities, occupational therapy, psychosocial intervention

1. Introduction

Of 5+ million Americans with Alzheimer's disease or related disorders, most are cared for at home by over 15 million family caregivers (Alzheimer's Association, 2016). A hallmark of dementia, and its most challenging and costly aspect, is neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS). NPS, including agitation, aggression, irritability, apathy, rejection of care, depression and others, are almost universal, occurring across disease types and stages (Lyketsos et al., 2011). If untreated, NPS hasten disease progression, worsen daily functioning, impair quality of life, increase healthcare utilization, and accelerate nursing home placement (Cooper, et al., 2015; Rabins et al., 2013). For caregivers, NPS are associated with depression, worse quality of life, and increased time caregiving (Gitlin, et al., 2012; Miyamoto et al., 2010). NPS account for a significant portion of the estimated $152 billion spent annually in dementia care (Beeri, 2002; Murman et al., 2002).

NPS are consistently under-detected and undertreated. If treatment occurs, it typically involves antipsychotics (Small, 2014). However, pharmacological options have modest to no benefits compared to placebo, with serious risks, including mortality in older adults with dementia (Maust et al., 2015). One exception, Citalopram, reduced agitation in 186 patients (Porsteinsson et al., 2014), although with some adverse effects and further study is underway. Nevertheless, there are no medications for behaviors of most concern to families (e.g., rejection of care).

As dementia will affect over 16 million Americans in 2050 (Alzheimer's Association, 2015), a critical public health priority is reducing disease burden on families. Developing and testing behavioral care strategies provide an alternative treatment approach to prevent, reduce and/or manage NPS.

One promising nonpharmacologic approach is use of activities that capitalize on preserved capabilities and life-long social roles and interests. Evidence suggests that persons with dementia can effectively engage in activities graded to their abilities (Trahan, et al., 2014), resulting in reduced NPS (Cohen-Mansfield et al., 2010; Gitlin et al., 2008; Kolanowski et al., 2008). Tailored activities may afford engagement and positive affect, thus minimizing or preventing build-up of frustration and agitation, or other NPS. Moreover, activities may fill a void, help to maintain roles, and enable positive expressions in persons with dementia (Gitlin et al., 2016). Additionally, instruction to caregivers to effectively involve persons with dementia in activities may minimize supervisory time and enhance their own wellbeing. However, limitations of previous activity-based research include small sample sizes, lack of randomized trial methodology, poorly characterized samples, inattention to fidelity and caregiver abilities, and lack of control of therapeutic processes (e.g., attention) inherent in providing activity (Jutkowitz et al., 2016).

The Dementia Behavior Study tests the efficacy of a novel activity intervention to reduce NPS among community-dwelling persons with dementia and to enhance caregiver well-being. The intervention is compared to an intervention that controls for effects of empathy, validation, and attention. Unique to this trial is an analysis of cost, and cost-effectiveness and treatment fidelity, both of which are necessary for translation and wide-scale implementation if the intervention is effective. In addition to describing the study design, this paper highlights the interventions.

2. Study Design

In a pilot randomized trial of 60 families, we demonstrated that tailoring activities to the capabilities and interests of persons with dementia, and training families in their use, can reduce the overall occurrence of NPS, specifically agitation, as well as reduce time spent caregiving by family members (Gitlin et al., 2008; Gitlin et al., 2009). Building on our previous work, the Dementia Behavior Study is a randomized two-group parallel design with an expected enrollment of 250 community-dwelling persons with dementia and their primary caregivers (dyads).

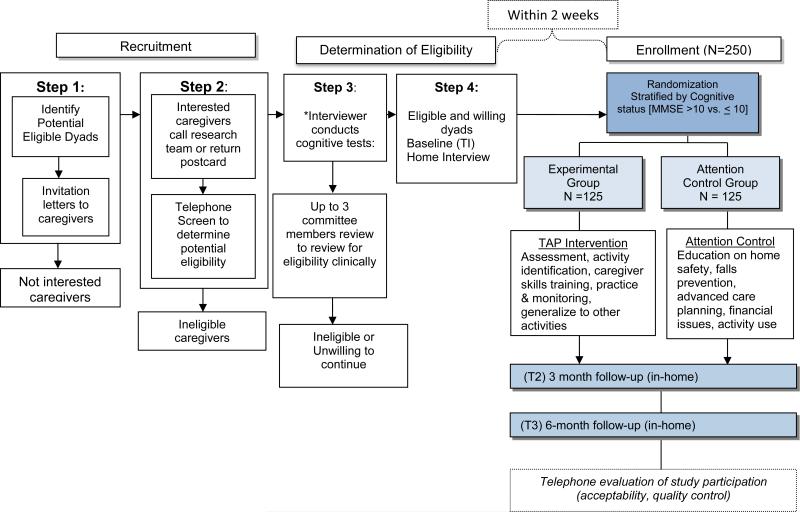

Figure 1 displays the study design and design elements are described below.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of Study Design

This is one of the few large-scale rigorously designed randomized clinical trials (RCT) to determine whether participation in activities that match interests and abilities and account for caregiver readiness and environmental factors, reduces NPS. Similar trials and demonstration projects of this intervention are also underway in the Veterans Administration (Gitlin et al., 2013), Australia (O'Connor et al., 2015) and Brazil (Novelli et al., 2016). Also, this intervention (referred to as New Ways for Better Days, Tailoring Activities for Persons with Dementia and Caregivers [TAP]), is being used and evaluated in a variety of sites (Scotland, adult day services in the United States, England). However, the study trial described here includes design elements that distinguish it from other efforts and which elevates the science of activity intervention research in important ways as described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of Novel Features of the Dementia Behavior Study

| • Use of a comparison group to control for unknown effects of empathy, validation, and attention, time spent in sessions, and therapeutic engagement. |

| • Cost-effectiveness measures and associated analyses including evaluation of the willingness of families to pay for training in use of tailored activities. |

| • Non-clinical study staff members trained to obtain medical history that is then reviewed by a clinical team |

| • Substantiation of clinical level of behavioral occurrences and dementia diagnosis by board-certified geriatric psychiatrists and/or a PhD nurse researcher with expertise in dementia through documentation and audiotape review. |

| • Rigorous oversight of intervention fidelity. |

| • Use of a decision-making tree for identification of tailored activities for persons with dementia. |

2.2 Research Aims

Primary Aim

The primary study aim is to evaluate the immediate effect of the activity intervention on the frequency and severity of agitation and aggression at 3 months. Our hypothesis is that persons with dementia in the activity intervention arm, compared to those in the control group intervention arm, will have a greater reduction in agitated/aggressive behaviors (frequency and severity) from baseline to 3 months as rated by primary caregivers using items from the Neuropsychiatric Inventory–Clinician Rating (NPI-C) subscales of agitation and aggression (21 items).

Secondary Aims

One secondary aim is to evaluate the effects of the activity program from baseline to 6 months on behavioral symptoms, and quality of life in persons with dementia. We hypothesize that persons with dementia in the activity treatment arm compared to those in the control group intervention arm will have a greater reduction in agitated/aggressive behaviors (frequency and severity) from baseline to 6 months as rated by primary caregivers using items from the NPI-C agitation and aggression subscales. Similarly, we hypothesize that caregivers in the activity group compared to those in the control group will report improved quality of life for persons with dementia from baseline to 6 months. We will also consider whether the number and frequency of other behaviors are reduced by 3 and 6 months. Another secondary aim is to evaluate the effects of the activity program at 3 and 6 months on caregiver wellbeing (burden, skill acquisition, efficacy using activities), and time spent providing care. We hypothesize that caregivers receiving the activity intervention arm will report improved wellbeing and less time caregiving compared to those in the control group intervention arm from baseline to 3 and 6 months.

Finally, we will evaluate intervention costs, cost effectiveness and financial acceptability. We hypothesize that from a societal perspective the activity program will be cost-effective compared to the control program at 3 and 6 months. For financial acceptability, we will examine the level of a caregiver's willingness to pay for the activity program prior to and after receiving it.

Exploratory Aims

To further understand treatment effects and enhance implementation potential we will also evaluate: 1) the impact of the activity intervention on psychotropic medication use versus control condition at 3 and 6 months by comparing the proportion of persons with dementia who require dose increases or new use of psychotropic medications (negative outcome) and the proportion of persons with dementia who reduce or eliminate medication use because agitation improved (positive outcome); 2) whether treatment effects differ at 3 and 6 months by baseline cognitive status; 3) whether the activity intervention reduces total NPI-C scores at 3 and 6 months; 4) if at 6-months caregivers receiving the activity intervention are using prescribed activities and with what frequency; and how caregivers use personal time gained; and 5) the extent to which implementation processes (number of sessions, time spent in treatment, extent of activity use ) affects NPI-C scores.

2.2 Conceptual Framework

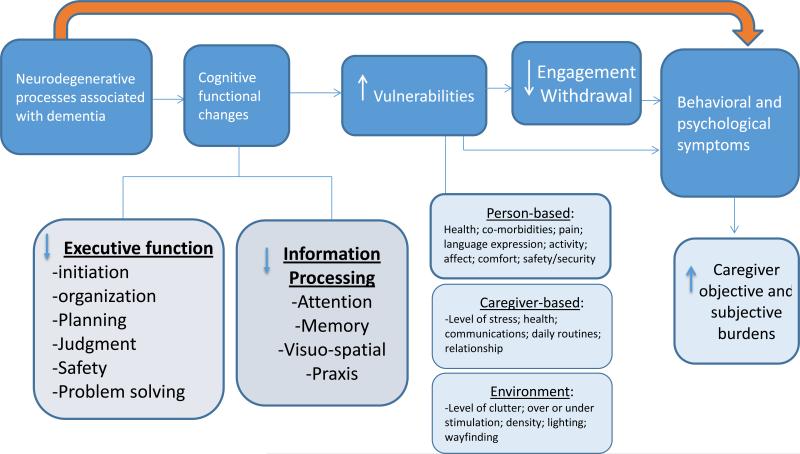

The trial is based on a broad conceptualization as to why and how NPS occur. As Figure 2 displays, NPS may be a direct consequence of the neurodegenerative processes; this pathway may lead to pharmacologic interventions for specific NPS. However, with degradation in neuro-circuitry, other processes are impacted which may contribute to NPS and warrant other intervention strategies. As suggested by Figure 2, brain damage impairs cognitive functions including executive control (e.g., initiating, organizing, sequencing, planning or executing activities), and new learning and problem solving. These deficits in turn may lead to greater vulnerabilities to the physical (e.g., home clutter) and social (e.g., stressed caregiver, ineffective communication style, and unrealistic expectations) environments and the inability to meaningfully and effectively engage in daily activities. A consequence may be NPS (e.g., agitation, anxiety, rejection of care) due to unmet needs, mismatches between a person's capabilities and caregiver and environmental expectations), including under or inappropriate stimulation, and an inability to effectively engage in previous roles and preferred activities.

Figure 2.

Conceptual Model Linking Neurodegenerative Changes with Decreased Engagement and Behavioral Symptoms

2.3 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Both persons with dementia and caregivers must meet eligibility requirements (e.g., if one is ineligible, the dyad is not randomized). Persons with dementia are eligible who: 1) are English-speaking; 2) have a physician diagnosis of dementia (mild, moderate, severe); 3) are able to participate in at least two activities of daily living (e.g., bathing, dressing, grooming, toileting, transferring from bed to chair); and 4) demonstrate agitated/aggressive behaviors.

For the latter, caregivers must endorse at least one item on the agitation/aggression subscale of NPI-C with a frequency or severity score ≥2. If only one item on the agitation/aggression subscale is endorsed with a frequency of ≥ 2, then at least two additional behaviors need to be endorsed with a frequency of ≥ 2. This is to assure that the behavioral symptoms which occur are clinically meaningful.

If persons with dementia are on any of four classes of psychotropic medications (antidepressants, benzodiazepines, antipsychotics, or anticonvulsants) or an anti-dementia medication (memantine or a cholinesterase inhibitor), they must have been on a stable dose for 60 days prior to enrollment to minimize confounding effects of medications on NPS.

Caregivers are eligible if they are: 1) English-speaking; 2) a family member (defined broadly to include neighbors, fictive kin) 21 years of age or older (male or female); 3) living with the person with dementia or within 5 miles or 15 minutes; 4) accessible by telephone to schedule interview and intervention sessions; and 5) planning to live in the area for 6 months (to reduce loss to follow-up). Finally, we require that caregivers taking a psychotropic medication (antidepressants, benzodiazepines, antipsychotics, or anticonvulsants) be on a stable dose of medication for 60 days prior to enrollment.

Persons with dementia are excluded from participation if they: 1) have schizophrenia or a bipolar disorder; 2) have dementia secondary to head trauma; or 3) are unresponsive to their environment (e.g., unable to understand short commands or recognize a person coming in or out of the room).

Caregivers are excluded if they are: 1) currently involved in another clinical trial of psychosocial or educational interventions; or 2) planning to place their family member in a nursing home within the next 6-months. Dyads are excluded if either caregivers or persons with dementia: 1) have a terminal illness with life expectancy <6 months; 2) are in active treatment for cancer; or 3) have had >3 acute medical hospitalizations in the past year. These criteria are designed to minimize attrition due to poor health or exclude dyads who would not potentially benefit from the interventions dues to their poor health status.

3. Recruitment and Sample Size

Dyads are recruited using approved Institutional Review Board materials and include mailings by local aging service providers, media announcements, local community health seminars and events, and online trial searches (e.g., Alzheimer's Association TrialMatch® and www.clinicaltrials.gov). Interested caregivers participate in a telephone screen conducted by trained study staff to determine eligibility (see Figure 1). For those eligible at this stage, an in-home visit is scheduled to obtain consent using an IRB approved form, and conduct a baseline interview. Consent is obtained from caregivers and persons with dementia, if possible, or if not, proxy consent from caregivers who are authorized agents is secured. To obtain consent from persons with dementia, we use an approach that involves asking a question following each section of the consent to assess level of understanding (e.g., What is study purpose? What are study risks?). If the person with dementia demonstrates confusion, agitation or prefers that the family caregiver review the consent form, then proxy consent is sought and the person with dementia is asked to provide verbal assent to participate in a clinical interview that follows. If either the person with dementia or caregiver refuses study participation during the consenting process, the dyad is not enrolled.

The baseline interview involves an assessment of capacity including cognitive status and judgment of the person with dementia using standardized approaches (Mini-mental State Examination, Clinical Dementia Rating and clinical interview of caregiver). This assessment (audiotaped), along with portions of the telephone screen, are reviewed by up to three clinical experts: board-certified gero-psychiatrists (CGL & DJ) and/or a doctoral-level geriatric nurse researcher (NH), all of whom are experts in dementia care. Their review is designed to: a) determine medication profile to assure stability in dosage; b) identify any immediate safety issues; c) assure that level of behavioral frequency and severity is clinically meaningful and meets our a priori inclusion criteria; and d) confirm diagnosis based on MMSE and CDR ratings. Following confirmation of eligibility, a researcher not associated with the research team or knowledgeable about trial hypotheses, randomly assigns dyads to either the treatment (activity intervention group) or attention control (referred to as the Home Safety and Education group) arms. Randomization is stratified by cognitive state (MMSE >10 vs. ≤10) to assure balance in treatment arms as pilot work showed differential treatment effects by cognitive levels. By altering the block sizes for stratification, we will enhance and protect the allocation concealment aspect of the randomization procedure in which the randomization schedule has been prepared in advance. All dyads receive $15 for each completed home interview (baseline, 3, and 6 months).

Sample size calculations were based upon: a) one primary outcome at 3 months; b) treatment effect sizes for outcomes from the pilot phase and other nonpharmacologic trials; c) ability to detect a near medium effect size (d) of 0.40; and d) a type I error rate of .05. A smaller effect size would bring us at or near levels where the study could have statistical but not clinical significance [i.e., number needed to treat (NNT) of 4.5]. To attain 80% power for a two-sided comparison of the two treatment groups at 3 months will require 100 dyads per group. We plan to recruit an additional 25 per group or 50 dyads for a total of 250 (125 per group) allowing for 20% attrition by 6 months.

4. Measures

A summary of all primary and secondary endpoints, covariates and descriptive variables are shown in Table 2. .

Table 2.

Summary of Descriptive and Secondary Endpoint Measures and Testing Occasions

| Domain (purpose) | Measure (Citation/ Source) | Description (alpha based on previous trials) | Respondent | Testing Occasion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PwD cognitive status (descriptive, possible covariate) | MMSE (Folstein, 1999) | Cognitive status | PwD | Screening process |

| PwD physical health and comorbidities (descriptive, possible covariate) | Caregiver assessment of function (CAFU).(Gitlin, 2005) | CG proxy report of PwD dependence level (a little to complete help) (alpha =.90) | Caregiver | Screening process |

| PwD Quality of life as rated by CG (secondary outcome) | QOL-AD (Logsdon, 2002) | 12 domains; PwD with MMSE>10 can respond; also proxy report is used | Caregiver | T1, T2, T3 |

| Demographics (descriptive, possible covariate) | Caregiver and PwD Information (US Census + other sources) | Basic background characteristics | Caregiver | T1 |

| Medications (descriptive, possible covariate) | PwD and CG medications (Adapted from REACH) | Brown bag review of prescription and non-prescription meds | Brown bag review | T1 |

| PwD physical health (descriptive, possible covariate) | SF-36, other health measures | CG Proxy report of health | Caregiver | T1 |

| CG Objective and subjective burden (secondary outcomes) | -Upset with behaviors (NPI-C);burden;(Bedard, 2001) Vigilance Items (Hrs. on duty + doing things)(Mahoney, 2003) | For each NPI-C behavior, CG rates upset (0=no upset to 4=very upset); Vigilance items ask CG to estimate time spent in care (alpha = .89) | Caregiver | T1, T2, T3 T1, T2, T3 |

| CG Depressive symptoms (potential moderator) | CES-D short form179,(Santor, 1997)188 | 10-items; sensitive to change; Cut off for depression ≥8 (alpha = .91) | Caregiver | T1, T2, T3 |

| CG Skill acquisition (secondary outcome) | Task Management Strategies Index (Gitlin, 2002)87 | Frequency using simplification techniques. Likert scale (1= never use to 5 = always use) (alpha = .80) | Caregiver | T1, T2, T3 |

| CG Efficacy (secondary outcome) | Caregiver confidence using activities (Gitlin, 2008)86 | 5 items reported on a 10 point scale (0=Not confident, 10=Very confident). | Caregiver | T1, T2, T3 |

| Activity use and CG use of discretionary time (exploratory outcome) | Investigator developed(Gitlin, 2008)86,92 | Track use of prescribed activities in treatment arm | Caregiver | Telephone survey following T3 |

| Treatment implementation - Delivery; Receipt Enactment (description of intervention processes) | Intervention Delivery Assessment form Investigator developed (adapted from REACH and refined in pilot work) | a) dose (# of contacts); b) intensity (time spent each contact); c) session content; d) CG acceptability (receipt) and perceived benefit (enactment; e) acceptability (receipt) and perceived benefit and activity use (enactment) | Interventionist | Interventionist completes within 48 hrs. of each |

| Evaluation of study/ Quality control (descriptive, quality control) | Program Evaluation (Adapted from previous studies | Caregiver satisfaction with and utility of intervention; quality assurance | Caregiver | Telephone survey following T3 |

Note: CG=caregivers; PwD= person with dementia; T1 = baseline, T2 = 3-month follow-up; T3 = 6-month follow-up. We estimate interviews with CGs to average 1½ hours.

Here we highlight two primary measures. For the primary study endpoint, change in frequency and severity of agitated-type behaviors, we use an adaptation of the NPI-C. Originally developed for administration and response by clinicians, in this trial, we employ the items but obtain caregiver (versus clinician) responses. Fourteen NPS domains are assessed for presence or absence; if present, follow-up questions identify the specific behaviors that may occur, their frequency and severity. For this trial, all follow-up questions are asked for items in the agitation and aggression domains, even if the participant reports absence in the screen question. Each follow-up item (e.g., “Does (S) ask repetitive questions or make repetitive statements?”) is rated for frequency along 5-point Likert scales (0=never to 4=very frequently-once or more/day), and severity along 4-point Likert scales (0=none to 3=a major source of behavioral abnormality), and caregiver distress along 6-point Likert scales (0=not distressing to 5=extremely).

The primary cost-effectiveness measure is defined as the difference between the cost of the intervention and the attention control groups divided by the difference in quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) at both 3 and 6 months (i.e., incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; ICER). A secondary cost-effectiveness measure compares the difference in cost of the intervention and attention control group divided by the difference in time spent providing care at 3 and 6 months. Financial acceptability for intervention and control group interventions are evaluated by examining the caregiver's willingness to pay to participate in the intervention compared to the cost of delivering the program (measured at baseline, 3 and 6 months).

5. Intervention Protocol

The activity-based intervention is delivered by occupational therapists and involves up to 8 face-to-face contacts over 3 months with each session averaging 1½ hours. The intervention unfolds in 3 phases (see Table 3). Phase I (sessions 1-2) involves assessments of the capacity and interests of persons with dementia, caregiver communication style, coping mechanisms, and readiness to use new strategies, and the setup of the physical environment. Caregivers receive educational resources including the Caregiver Guide to Dementia: Using Activities and other Strategies to Manage Behavioral Symptoms (Gitlin & Piersol, 2014). This booklet provides tips for addressing behavioral symptoms in the form of helpful checklists and recommendations for taking care of self as a caregiver and medical considerations in the care of persons with dementia (e.g., monitoring hydration, pain, medications). Also in these visits, simple stress reduction techniques (deep breathing) are provided to caregivers to help them manage situational stress and set a calm tone in the environment prior to using activities as a therapeutic tool.

Table 3.

Overview of the Activity Program

| Session # | Week # | Type of contact | Session content |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 – Assessment of Caregiver, Dementia Patient and Environment | |||

| 1 | 1 | Home visit | • Provide overview of intervention goals and particular session goals • Provide caregiver with 36 hour day as a resource book and the Caregiver Notebook - Discuss how Notebook will be used in each session and help caregiver find a place to keep the Notebook for easy access - Provide basic information about caregiving, dementia, challenging behaviors, and value of structured and customized activities - Refer to materials in Caregiver Notebook • Conduct clinical interview with caregiver (review daily routines, preferences and interests and pleasant event) • Observe caregiver-patient communication and management techniques • Begin assessment of dementia patient (MMSE, Allen's cognitive assessments) • Evaluate patient comportment • Have caregiver complete Pleasant Event Survey • Review main points made in session and obtain closure • Establish next meeting date |

| 2 | 2 | Home visit | • Provide overview of specific session goals • Review education materials and inquire if caregiver has questions • Review Pleasant Event Survey and information from clinical interview to begin to brainstorm and identify specific activities that may be of interest • Continue with Allen cognitive assessments with dementia patient (ALLLEN Placemat) • Introduce stress reduction technique (signal breadth) to help caregiver manager their stress and set a positive emotional tone for activity engagement • Observe/evaluate areas of home (lighting, safety) in which activity will be conducted • Review main points made in session and obtain closure • Establish next meeting date |

| Phase 2 – Introduction of Activity, Communication, Task breakdown and Environmental Simplification Techniques | |||

| 3 | 3-4 | Home visit | • Provide overview of sessions goals • Review assessment results with caregiver • Provide 3 written activity prescriptions and ask caregiver/dementia patient (if appropriate) to select first activity to focus on • Review first activity prescription and implement: - Use role play to show caregiver how to set up activity or if possible demonstrate set up and activity with dementia patient - Instruct in relevant strategies (communication, cueing, environmental and task simplification techniques) - Introduce activity with dementia patient and have caregiver practice how to set up activity - Practice reinforce and validate caregiver techniques and dementia patient participation • Provide specific practice schedule (e.g., when to introduce activity each day and number of times in day/week to use) and how to integrate within a structured daily routine • Review main points made in session and obtain closure • Establish next meeting date |

| 4 | 5-6 | Home visit | • Provide overview of session goals • Review progress in use of first activity prescription with caregiver and use activity record to record number of times activity was used and outcome • Reinforce use of specific strategies (communication, task simplification, cueing) • Problem solve with caregiver if unable to use activity prescription or if activity was not received well and modify activity prescription if necessary • Identify and introduce next activity prescription with caregiver and dementia patient if appropriate using procedures outlined above in previous session • Reinforce and validate caregiver techniques • Provide specific recommendations as to when to introduce activity and number of times • Review main points made in session and obtain closure • Establish next meeting date |

| 5 | 7 | Tele-contact* | • Review progress and reinforce strategy use • Review, practice communication, environment and task simplification techniques • Determine with caregiver what was effective and modify strategies if necessary • Problem solve with caregiver how to use activities and generalize strategies to other types of activities or newly emerging problems (e.g., behavioral manifestations) • Establish next contact date/time |

| 6 | 8-9 | Home visit | • Provide overview of session goals • Review progress in use of first and second activity prescription with caregiver and use activity record to record number of times each activity was used and outcomes • Reinforce use of specific strategies (communication, task simplification, cueing) • Problem solve with caregiver if unable to use activity prescriptions or if activity was not received well; modify activity prescriptions if necessary • Identify and introduce 3rd activity prescription with caregiver and dementia patient if appropriate using procedures outlined above in previous sessions • Reinforce and validate caregiver use of techniques • Provide specific recommendations as to when to introduce each activity and number of times day/week • Review main points made in session and obtain closure • Establish next meeting date |

| Phase 3 – Generalize Strategies | |||

| 7 | 10 | Tele-contact * | • Review progress with caregiver • Reinforce use of all activities and strategies • Problem solve with caregiver if unable to continue to use activities • Discuss how to use strategies such as relax rules, divergence, cueing etc) to address other daily care challenges (e.g., resistance to bathing) • Establish next contact date/time |

| 8 | 11-12 | Home visit | • Review progress • Reinforce use of activities • Generalize use of strategies (e.g., simplifying the environment) to other care activities • For each activity prescription, provide written instructions for how to change activity for future declines • Obtain study closure |

Note.

If caregiver is having difficulty using activity prescriptions, then this will be a home visit and outline for session 6 will be followed.

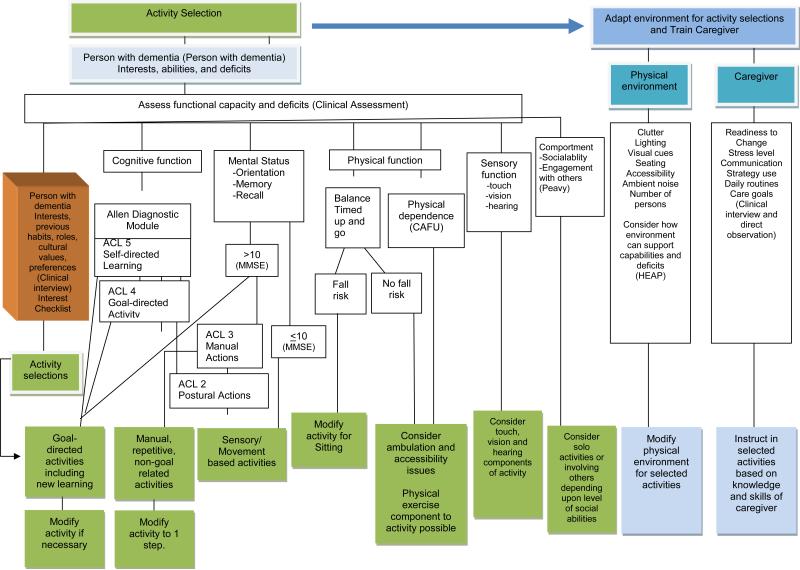

Based on a decision-making matrix that systematically moves interventionists through a clinical reasoning process (Figure 3), activities are identified with involvement of family caregivers, and persons with dementia (if possible). Although activities are case specific, examples include a craft, painting/coloring or preparing a simple meal for individuals with mild dementia; beading, sorting, walking, putting flowers in a vase for individuals with moderate dementia; listening to music, viewing a soothing video, or manipulating sensory-type objects for individuals with severe dementia.

Figure 3.

Decision-matrix for Identifying and Tailoring Activities

Phase II (sessions 3-6) involves providing families with a written Assessment Report summarizing results of the assessment to help caregivers understand the capabilities of the person with dementia. This is followed by providing three “Activity Prescriptions” each tailored to the cognitive, functional, social and interest profiles of persons with dementia as well as factors related to the physical and social environment, such as the location in which an activity should occur (e.g., dining room table, in a well-lit area), caregiver time needed to setup or supervise activities, and so forth. Figure 3 shows the domains and specific considerations involved in constructing activity prescriptions. Each activity prescription summarizes in lay language the capabilities of the person with dementia (e.g. good coordination and use of arms and hands), the activity (e.g., folding towels), when and where and for how long to conduct the activity (e.g., 20 minutes twice daily while caregiver prepares lunch and dinner meals), and specific instructions for introducing and using the activity. Specific instructions may include how to set up the activity, modify the environment and communicate effectively. Caregivers are further instructed in how to integrate activities in daily care (time of day, number of times per week, potential length of an activity session).

In Phase III (sessions 7-8), caregivers learn how to simplify each activity for future cognitive declines and how to use strategies (e.g., simplify environment, relax the rules) to address other care challenges (e.g., rejection of care, repetitive questioning).

While dyads receive all treatment phases, the pace by which treatment progresses depends upon caregiver readiness and acceptability and use of each activity. Caregivers observed by interventionists to be at a low level of readiness tend to demonstrate a poor understanding of dementia and overestimate the abilities of the person for whom they care. In these cases, interventionists provide more education and demonstration of how changing communications or simplifying an activity can yield positive results. Caregivers observed by interventionists to be at a high level of readiness tend to have a good understanding of dementia and the abilities of the person they care for and move more quickly through intervention phases. Following study conclusion, the activity group receives the educational resources provided to the attention control group.

Interventionists receive training using a detailed treatment manual (unpublished) and face-to-face didactic and interactive teaching modalities. An online program has now been developed to enable replication and scalability of training (http://learn.nursing.jhu.edu/face-to-face/institutes/NewWay-TAP/index.html).

6. Attention Control Protocol

The control condition is designed to control for elements of the activity intervention, such as a positive therapeutic alliance and social engagement with dyads, which may affect outcomes. The attention control intervention referred to as the Home Safety and Education Program, is a fully-structured, nondirective, supportive educational approach that conveys empathy, respect, and specific disease education elements that developed and tested in other trials. Unlike the activity intervention, this contains no active elements beyond its nonspecific components, ostensibly has no long-lasting treatment effects on persons with dementia, and no theoretical basis to support an impact on NPS, although it may improve caregiver confidence and well-being. It is delivered by research staff members who do not have the same level or type of training of occupational therapists providing the activity program. Interventionists for the attention intervention group provide education on various topics using scripted material. With caregivers, interventionists use active listening, open questioning, and reflecting back; with persons with dementia, interventionists provide brief assessments (e.g., Timed Up and Go Test) and social contact.

Attention control participants receive an equivalent number of and time in sessions as those in the activity group (up to 8 home sessions of up to 1½ hours in length). Caregivers are provided basic educational materials including The 36-Hour Day (Mace & Rabins, 2012) and each contact provides structured education based on a specific book chapter. Table 4 outlines the content of each session. At the conclusion of the study, participants in the attention control group receive the booklet, A Caregiver's Guide to Dementia: Using activity and other strategies to prevent, reduce, and manage behavioral symptoms (Gitlin & Piersol, 2014) which the intervention arm uses.

Table 4.

Overview of the Home and Safety Education Group (Attention Control)

| Session # | Week # | Type of contact | Session content | The 36-Hour Day chapter # | Length of time (CG/ PWD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | Home visit | Introduction; About Dementia; Home Safety Assessment; TUG | #1 | CG 1.5 hours PwD 15-20 minutes |

| 2 | 2 | Home visit | Review findings from Home Safety Assessment and TUG; Discuss Mitigating risk factors; Assessment of Medical Knowledge | #5: ‘Problems Arising in Daily Care’ pp. 59-64, 95-97. | CG 1.5 hours PwD 15-20 minutes |

| 3 | 3-4 | Home visit | Being an active member of the health team; Talking with your doctor; Advanced care planning | #6: ‘Medical Problems’ pp. 98-110. | CG 1.0 hours PwD 15-20 minutes |

| 4 | 5-6 | Home visit | Finding information and services; Resources Follow up/review of material presented | #10: ‘Getting Outside Help’ pp.168-171, 179-181. | CG 15 minutes |

| 5 | 7 | Home visit | Planning Ahead; Legal, Financial and Advanced Care | #15: ‘Financial and Legal Issues’ pp.242-252. | CG 1.0 hours |

| 6 | 8-9 | Home visit | Telephone Check in and review | -- | CG 15 minutes |

| 7 | 10 | Home visit | Taking Care of yourself | # 13 | CG 1.0 hours |

| 8 | 11-12 | Home visit | Final review and Closure | -- | CG 1.0 hours; PwD 15 minutes |

Note. TUG = Timed up and Go; CG = caregiver; PwD = Person with Dementia

7. Fidelity

We have a well-defined plan for treatment implementation oversight for both conditions (Gitlin & Parisi, 2016). Guided by Lichstein and colleagues’ fidelity model, we have incorporated recommended strategies including use of treatment manuals, systematic training of interventionists, regular contact with interventionists who present cases and discuss protocol issues, and on-going monitoring through direct observation and audiotaping of randomly selected sessions. All sessions (baseline, 3 and 6-month interviews, activity and attention control interventionist sessions) are audiotaped. Of these, 10% are selected for review by members of the research team using checklist monitoring forms developed expressly for the content and protocol expectations of each session. Timely individualized and group feedback is provided for course corrections.

We also are quantitatively evaluating treatment delivery (whether participants are provided the materials and number and time spent in intervention sessions are as intended); treatment receipt (whether participants receive the materials and have an understanding of strategies provided); and treatment enactment (whether participants utilize the activities). Biweekly supervisory sessions, held separately with treatment and control group interventionists, involve case presentations evaluated for respective protocol adherence, adjustments to coding of documentation and for updates of participant progression through the interventions.

8. Data Collection and Management

Data are collected at baseline and 3 or 6-months (T3). Within two weeks of the 6 month visit, a telephone survey is conducted by a research team member who is not involved in interviewing to assess caregiver appraisals of study experience and if they are using strategies introduced in either study arms.

All interviewers undergo standardized training in interviewing caregivers and persons with dementia. Data from interviews are collected on paper forms created in the TeleForm system (http://teleform-cardiff.com/), a platform for research data capture developed by Cardiff Software. TeleForm utilizes optical scanning to capture data; it then verifies the data, and exports them to a statistical software package such as SPSS, Excel, or CSV for analysis. The TeleForm software package has features designed to facilitate collection, storage, and validation of data from research studies. Prior to scanning, all interviews are checked first by the initial interviewer and then again by a second research team member for completeness and coding accuracy.

9. Data Analysis

Descriptive analyses and univariate comparisons of the experimental and control intervention group conditions will be conducted. A series of chi-square and independent sample t-tests will be employed on categorical and continuous variables, respectively, to identify differences between experimental and control group participants at baseline. In addition to serving as a final data quality check, these analyses will characterize the study sample, assess the effect of randomization in balancing the two groups and determine whether there is a differential dropout rate with respect to potentially important prognostic factors (e.g., age, caregiver education level). Covariates such as comorbidities, disease stage, psychotropic medication use, gender of caregiver and person with dementia will also be considered. All analyses will use current versions of SPSS, SAS, or Statistica.

For the primary trial aim, we will use an intention-to-treat (ITT) approach. We will calculate adjusted mean differences from baseline and 3months and baseline and 6 months in treatment effects on the outcome measure using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). The ITT approach tests the effect of the intervention without taking into account the extent to which dyads actually receive intervention and thus effectively penalizes the activity program if dyads are not willing to receive it or if they receive different doses or treatment exposures. If non-compliance exceeds a minimal threshold (e.g., 15%), we will supplement our ITT analyses with complier-average causal effect (CACE) models. Both ITT and CACE approaches can readily incorporate covariates, which will include baseline value of the outcome measure, MMSE group (>10 vs.≤10) of persons with dementia and other background characteristics if large or statistically significant differences between experimental and control group dyads are found for those variables.

ANCOVA analyses will test the normality assumption for the dependent measure (total severity score on NPI-C agitation and aggression domains) by examining the distribution of residuals. If the residual distribution is skewed, data transformation will be used. Covariates including comorbidities, disease stage, number/type of medications for both persons with dementia and caregivers, caregiver relationship, gender of both persons with dementia and caregivers will also be considered and evaluated as to whether they strengthen intervention benefit. As a follow-up to this primary outcome, and in keeping with other trials, clinical significance of findings will be assessed by calculating the number of dyads improving by ≥0.40 SD from baseline to 3 months and comparing proportions between treatment groups using Mantel-Haenszel chi-square analyses, controlling for MMSE. Also, a comparison will be made between the proportion of intervention and attention control intervention group dyads who had ≥1 behavior eliminated on the NPI-C agitation and aggression subscales by 3 months using chi-square analysis, controlling for MMSE and also examine net effects comparing proportions who improved to worsened.

For the first two secondary aims, we follow the approach for the primary aim. In separate analyses, we will examine whether the activity program has a 6-month effect (T1-T3) on NPI-C caregiver rated severity agitation+aggression scores and caregiver rated quality of life (QOL-AD) using ANCOVA analyses which control for baseline values of each, stratifying and other potential covariates (e.g., comorbidities). The other secondary endpoints, address caregiver outcomes and similar procedures will be followed. Measures include: caregiver burden (Upset on NPI scale and Zarit Short Burden Scale), skill acquisition (Task Management Index), self-efficacy (confidence using activities and managing behaviors), and time spent caregiving.

The primary ICER calculation will indicate the additional costs to bring about one additional QALY from the intervention compared to usual care. Health utilities will be obtained from Euro-QOL 5 Dimension (Herdman et al., 2011; Janssen et al., 2013, Pickard et al., 2004; van Hout et al., 2012) and the Health Utilities Index (Horsman et al., 2003; Kavirajan et al., 2009), expressed as QALYs. A secondary cost effectiveness measure is the cost per caregiver hour saved, measured as caregiver time spent “on duty” and time “doing things” (Mahoney, 2003),to determine value of the activity program in terms of its capacity to save caregiver time.

To determine the total cost of participating in each intervention, we will sum intervention costs, healthcare costs (e.g., hospital stays, nursing home stays, outpatient care, medications, and use of other health and community services), and caregiver costs (payments to formal caregivers, healthcare costs for the caregiver, and wages lost as a result of caregiving). The cost of delivering the intervention will be calculated using time logs retained by interventionists of treatment and attention control groups that includetime spent in preparation and provision of respective interventions, and supervision and training and materials used. Healthcare utilization will be captured using the Resource Utilization in Dementia—Lite (RUD-Lite) (Gustavsson et al., 2010; Gustavsson et al., 2011; Neubauer et al., 2009; Wimo et al., 1998; Wimo et al., 2007; Wimo et al., 2010; Wimo et al., 2013) and the Service Use and Resource Form (SURF) (Rosenheck et al., 2006; Rosenheck et al., 2007; Schneider et al., 2001), questionnaires developed specifically for clinical trials involving persons with dementia. Utilization will be converted to cost by applying prevailing reimbursement rates and case mix-based costs (using DRGs) for inpatient stays. Payments to formal caregivers will be calculated by applying a proxy wage rate (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2015) to formal caregiving hours reported. Informal caregiver lost wages will be measured as the product of their work time lost (obtained from the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire-Specific Health Problem (WPAI-SHP) (Reilly et al., 1993)) and a proxy wage rate for their reported occupation (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2015).

Sensitivity analyses will be completed to determine robustness of the cost-effectiveness analysis. Both univariate sensitivity analysis (whereby one variable is changed at a time and impact on the ICER will be examined), and probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA, whereby all relevant variables are simultaneously modified within reasonable ranges) will be conducted. The PSA will be conducted using a second order Monte Carlo simulation, which is based on estimated distributions for costs and effectiveness measures used to calculate the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio. The simulation will consist of up to 1,000 random iterations with the goal of determining the likelihood that the activity program is cost-effective compared to the attention control group. The PSA will be performed using the TreeAge Pro software program. Since the trial employs a time horizon of <1 year, discounting of future costs and benefits is not required.

Caregiver willingness to pay (WTP) for the activity program will be collected using a contingent valuation method, where caregivers are provided a starting price for the program per day, then asked if they would be WTP more or less for it until their acceptable price point is reached. The resulting WTP will be compared to actual program costs.

10. Discussion

NPS are a serious public health problem as they are a prodrome to dementia, worsen disease progression, add considerable burden to individuals with dementia and their family caregivers, and substantially contribute to health care utilization and care costs. There are few effective and safe treatments for NPS; even with the potential for future drug discoveries, the NPS of most concern to families may be difficult to address pharmacologically. As agitated and aggressive forms of behaviors often occur in the context of care provision, nonpharmacological approaches that provide caregivers with specific techniques to prevent and manage such behaviors before or as they occur are necessary. This clinical trial is the first large-scale study with an adequate comparison group, that controls for the effects of attention and empathy, and which carefully characterizes the clinical population from which to evaluate the effects of tailored activities in reducing NPS (agitation/aggression specifically) in persons with dementia. Additionally, the focus on enrolling both African American and Caucasian as well as community-dwelling families with a range of socioeconomic levels, will enable determination as to who benefits most and particularly among families less resourced. Furthermore, the trial's attention to staff training, and single blinding of interviewers, provide a level of control not achieved previously in most activity trials. Our findings will have broad clinical significance in that if positive, it would provide an evidence-based approach to help families manage challenging behaviors. Negative or null findings will provide an understanding of the limits of activity as a therapeutic strategy. Additional research will be necessary to evaluate strategies for large scale implementation and specific methodologies for training interventionists (occupational therapists and others) in this approach.

The activity program draws upon the knowledge and skill set of occupational therapists who are explicitly trained in activity analysis through assessing and integrating cognitive, functional, psychosocial and environmental factors in treatment planning. However, the protocol does vary from traditional occupational therapy in several important ways. First, the treatment focus is directed at both the person with dementia and the caregiver. Training in the activity protocol is necessary and involves how best to elicit and engage both individuals, identify activities based on assessment results, help caregivers understand behaviors and importance of structured activities, and train families in their use. Second, the caregiver is viewed as a collaborator and is engaged in the intervention as a partner in the construction of activities and their use; this family-centered approach is in contrast to prescriptive or didactic treatments focused on a “patient.” Third, the intervention is tailored to the readiness level of caregivers; those observed to have a low level of readiness to use new strategies (simplifying communications and everyday tasks) may need more basic dementia education than those entering the intervention with a higher level of readiness. Finally, for many occupational therapists working within rehabilitation settings, the activity program will represent a different paradigm from curative and new learning to compensatory and an emphasis on engagement. Hence, training in this program is required.

NPS, one of the most disabling symptoms of dementia, result in lower overall quality of life for both persons with dementia and their caregivers, and contribute to disease-related morbidity and mortality. A common complaint of families is their inability to effectively engage a person with dementia and concern for a low quality of life. Activity may be an antidote. Families typically overestimate the abilities of persons with dementia and have a poor understanding of how dementia impacts behaviors. Typically behavioral symptoms are assumed to be purposeful, reflect mal intentions or are directed negatively towards the caregiver to “spite” them. Thus, caregivers need education about the disease and concrete understanding of why and how behavioral symptoms manifest as a consequence of dementia. A novel feature of the intervention is its assessment phase. It provides families with concrete information concerning what the person with dementia can and can not do. Specific information is conveyed about the executive (e.g., their initiation, types of cueing needed), as well as social and physical abilities (e.g., fall risk, preference for being with others) of the person with dementia, safety at home, and previous occupations, habits and interests that can be tapped into for providing an activity with appropriate set up and customization. Activities are designed to capitalize on the preserved capabilities, strengths, and lifelong roles/interests of persons with dementia versus activities that emphasize new learning or seek to improve memory (a common goal imposed by families and sometimes health providers). Our premise is that an activity can be designed for a person at any level of impairment as long as they are responsive to their environment. Persons with severe cognitive impairment may benefit from sensory type activities such as bouncing a balloon, listening to music or watching videos of animals. Persons with moderate cognitive impairment may benefit from procedural activities or activities using repetitive actions such as washing dishes, sorting beads or cards; whereas persons with mild dementia may benefit from goal-directed activities such as arts and crafts, preparing simple meals, painting or puzzles. The purpose of activity is to engage the person and provide a pleasant experience to promote a sense of self, connectedness, belonging, and identity with disease progression.

Limitations of the proposed protocol should be noted. First, the follow-up period is relatively short (up to 6 months) due to funding constraints. It does not permit exploration of how long activities are used and how long treatment effects endure. Another limitation is reliance on family caregivers to report occurrences, frequency and severity of neuropsychiatric symptoms and perceptions of the quality of life of persons with dementia. Nevertheless, our approach reflects the state-of-the-science widely used in drug and non-drug trials.

If clinical trial findings are positive, the activity program has potential to transform the current paradigm of dementia care that relies primarily on pharmacologic solutions and undertreats and undermanages NPS. It will offer clinicians and families a proven nonpharmacologic approach to enhance quality of life that can be replicated, has reimbursement potential, and resonates with medical treatment guidelines and health care reform efforts aimed at reducing pharmacologic use and helping individuals be cared for at home. The importance of this trial is underlined by the increasing numbers of persons with dementia, the high prevalence and burden of NPS, and the lack of effective treatments to date for NPS. This activity program, as a therapeutic modality,may be a “pill” to ease disease burden and provide persons with dementia and caregivers better quality of life.

Acknowledgements

Funding source: Funded by the National Institute on Aging (Grant # R01 AG041781-01A1) and by the Johns Hopkins ADRC (P50AG005146).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial disclosure: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Clinical trial registration: NCT01892579

References

- Alzheimer's Association . 216 Alzheimer's Disease Facts and Figures. 4. Vol. 12. Alzheimer's & Dementia; 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang H, Zhao H. Median-based incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). Journal of Statistical Theory and Practice. 2012;6(3):428–442. doi: 10.1080/15598608.2012.695571. doi:10.1080/15598608.2012.695571 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedard M, Molloy DW, Squire L, Dubois S, Lever JA, O'Donnell M. The Zarit Burden Interview: A new short version and screening version. The Gerontologist. 2001;41:652–657. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.5.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeri MS, Werner P, Davidson M, Noy S. The cost of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) in community dwelling Alzheimer's disease patients. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2002;17(5):403–408. doi: 10.1002/gps.490. doi:10.1002/gps.490 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazier JE, Harper R, Jones NMB, O'Cathain A, Thomas KJ, Usherwood T, Westlake L. Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care. BMJ. 1992;305:160–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6846.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J, Marx MS, Dakheel-Ali M, Regier NG, Thein K, Freedman L. Can agitated behavior of nursing home residents with dementia be prevented with the use of standardized stimuli? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2010;58(8):1459–1464. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02951.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper C, Sommerlad A, Lyketsos CG, Livingston G. Modifiable predictors of dementia in mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2015;(7) doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14070878. appi.ajp.2014.1. http://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14070878. [DOI] [PubMed]

- de Medeiros K, Robert P, Gauthier S, Stella F, Politis A, Leoutsakos J, Lyketsos C. The neuropsychiatric inventory-clinician rating scale (NPI-C): Reliability and validity of a revised assessment of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia. International Psychogeriatrics / IPA. 2010;22(6):984–994. doi: 10.1017/S1041610210000876. doi:10.1017/S1041610210000876 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Bylsma FW. Noncognitive symptoms of Alzheimer's disease. In: Terry RD, Katzman R, Bick KL, Sisodia SS, editors. Alzheimer Disease. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 1999. pp. 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. doi:0022-3956(75)90026-6 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Piersol CV. A Caregiver's Guide to Dementia: Using activity and other strategies to prevent, reduce, and manage behavioral symptoms. Camino Books, Inc.; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Parisi J. Are treatment effects real? The importance of treatment fidelity. In: Gitlin LN, Czaja SJ, editors. Behavioral Intervention Research: Designing, Evaluating and Implementing. Springer Publ; NY.: 2016. pp. 213–239. [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Roth D, Burgio L, Loewenstein DA, Winter L, Nichols L, et al. Assessment of dependence in individuals with Alzheimer's disease and dependence-associated burden: Psychometric evaluation of a new measure for use with caregiver–care recipient dyads. Journal of Aging and Health. 2005;17(2):148–171. doi: 10.1177/0898264304274184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Winter L, Earland TV, Herge EA, Chernett NL, Piersol CV, Burke JP. The Tailored Activity Program to reduce behavioral symptoms in individuals with dementia: Feasibility, acceptability, and replication potential. The Gerontologist, Practice Concepts. 2009;49(3):428–439. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Kales HC, Lyketsos CG. Nonpharmacologic management of behavioral symptoms in dementia. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;308(19):2020–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.36918. http://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.36918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Mann WC, Vogel WB, Arthur PB. A non-pharmacologic approach to address challenging behaviors with Dementia: Description of the Tailored Activity Program-VA randomized trial. BMC Geriatrics. 2013;13:96. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-13-96. doi:10.1186/1471-2318-13-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Marx KA, Alonzi D, Kvedar T, Moody J, Trahan M, Van Haitsma K. Nonpharmacological care of patients with dementia hospitalized for behavioral symptoms: Feasibility of the Tailored Activity Program for Hospitals (TAP-H). The Gerontologist, Practice Concepts. 2016 doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw052. doi:10.1093/geront/gnw052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Winter L, Burke J, Chernett N, Dennis MP, Hauck WW. Tailored activities to manage neuropsychiatric behaviors in persons with dementia and reduce caregiver burden: a randomized pilot study. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2008;16(3):229–239. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318160da72. http://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e318160da72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Winter L, Dennis MP, Hauck WW. Assessing perceived change in the well-being of family caregivers: Psychometric properties of the perceived change index and response patterns. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Disorders. 2006;21:304. doi: 10.1177/1533317506292283. DOI: 10.1177/1533317506292283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Winter L, Dennis M, Corcoran M, Schinfeld S, Hauck W. Strategies used by families to simplify tasks for individuals with Alzheimer's disease and related disorders: Psychometric analysis of the task management strategy index (TMSI). The Gerontologist. 2002;42:61–69. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.1.61. PMCID: Not available. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustavsson A, Jonsson L, Rapp T, Reynish E, Ousset P, Andrieu S, ICTUS Study Group Differences in resource use and costs of dementia care between European countries: baseline data from the ICTUS study. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging. 2010;14(8):648–54. doi: 10.1007/s12603-010-0311-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustavsson A, Cattelin F, Jönsson L. Costs of care in a mild-to-moderate Alzheimer clinical trial sample: key resources and their determinants. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2011;7(4):466–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, Janssen M, Kind P, Parkin D, Badia X. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Quality of Life Research : An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation. 2011;20(10):1727–1736. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x. doi:10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoe J, Katona C, Roch B, Livingston G. Use of the QOL-AD for measuring quality of life in people with severe dementia – the LASER-AD study. Age and Ageing. 2005;34:130–5. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afi030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horr T, Messinger-Rapport B, Pillai JA. Systematic review of strengths and limitations of randomized controlled trials for non-pharmacological interventions in mild cognitive impairment: Focus on alzheimer's disease. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging. 2015;19(2):141–153. doi: 10.1007/s12603-014-0565-6. doi:10.1007/s12603-014-0565-6 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsman J, Feeny D, Torrance G. The health utilities index (HUI(R)): Concepts, measurement properties and applications. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2003;16(1):54. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen MF, Pickard AS, Golicki D, Gudex C, Niewada M, Scalone L, Swinburn P, Busschbach J. Measurement properties of the EQ-5D-5L compared to the EQ-5D-3L across eight patient groups: A multi-country study. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation. 2013;22(7):1717–1727. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0322-4. doi:10.1007/s11136-012-0322-4 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF. A short form of the informant questionnaire on cognitive decline in the elderly (IQCODE): Development and cross-validation. Psychological Medicine. 1994;24(1):145–153. doi: 10.1017/s003329170002691x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jutkowitz E, Brasure M, Fuchs E, Shippee T, Kane RA, Fink HA, Butler M, Sylvanus T, Kane RL. Care-Delivery Interventions to Manage Agitation and Aggression in Dementia Nursing Home and Assisted Living Residents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of American Geriatrics Society. 2016;64:477–488. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kales HC, Gitlin LN, Lyketsos CG. Assessment and management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. British Medical Journal. 2015;350:h369–h369. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h369. http://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavirajan H, Hays RD, Vassar S, Vickrey BG. Responsiveness and construct validity of the health utilities index in patients with dementia. Medical Care. 2009;47(6):651–661. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819241b9. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819241b9 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolanowski AM, Buettner L. Prescribing activities that engage passive residents. An innovative method. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2008;34(1):13–18. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20080101-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolanowski AM, Litaker M, Buettner L. Efficacy of theory-based activities for behavioral symptoms of dementia. Nursing Research. 2005;54(4):219–228. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200507000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logsdon RG, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, Teri L. Assessing quality of life in older adults with cognitive impairment. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2002;64(3):510–519. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200205000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyketsos CG, Carrillo MC, Ryan JM, Khachaturian AS, Trzepacz P, Amatniek J, Miller DS. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2011;7(5):532–539. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.05.2410. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2011.05.2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mace NL, Rabins PV. The 36-hour day: A family guide to caring for people who have Alzheimer's disease, related dementias, and memory loss (Fifth Edition) Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore, Maryland: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney DF, Jones RN, Coon DW, Mendelsohn AB, Gitlin LN, Ory M. The caregiver vigilance scale: Application and validation in the resources for enhancing Alzheimer's caregiver health (REACH) project. American journal of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias. 2003;18(1):39–48. doi: 10.1177/153331750301800110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maust DT, Kim HM, Seyfried LS, Chiang C, Kavanagh J, Schneider LS, Kales HC. Antipsychotics, other psychotropics, and the risk of death in patients with dementia. Journal of the American Medical Association, Psychiatry. 2015;72(5):438–445. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.3018. http://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.3018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto Y, Tachimori H, Ito H. Formal caregiver burden in dementia: Impact of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia and activities of daily living. Geriatric Nursing. 2010;31(4):246–253. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2010.01.002. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC. The clinical dementia rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murman DL, Chen Q, Powell MC, Kuo SB, Bradley CJ, Colenda CC. The incremental direct costs associated with behavioral symptoms in AD. Neurology. 2002;59(11):1721–1729. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000036904.73393.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics . Data File Documentation, National Health Interview Survey, 2012 (machine readable data file and documentation) National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Hyattsville, Maryland: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer S, Holle R, Menn P, Grässel E. A valid instrument for measuring informal care time for people with dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2009;24(3):275–82. doi: 10.1002/gps.2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novelli M, et al. The Brazilian version of Tailored Activity Program (TAP-Br) to manage Neuropsychiatric Behaviors in persons with dementia and reduce Caregiver Burden in Brazil: a randomized pilot study.. Poster presentation at the AAIC; Toronto, Canada. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor CM, Clemson L, Brodaty H, Gitlin LN, Piguet O, Mioshi E. Enhancing caregivers' understanding of dementia and tailoring activities in frontotemporal dementia: two case studies. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2015;00(00):1–11. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2015.1055375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, Skaff MM. Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. The Gerontologist. 1990;30:583–594. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickard AS, Johnson JA, Feeny DH, Shuaib A, Carriere KC, Nasser AM. Agreement between patient and proxy assessments of health-related quality of life after stroke using the EQ-5D and Health Utilities Index. Stroke. 2004;35(2):607–612. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000110984.91157.BD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porsteinsson AP, Drye LT, Pollock BG, Devanand DP, Frangakis C, Ismail Z, CitAD Research Group Effect of citalopram on agitation in alzheimer disease: The CitAD randomized clinical trial. Jama. 2014;311(7):682–691. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.93. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.93 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabins PV, Schwartz S, Black BS, Corcoran C, Fauth E, Mielke M, Tschanz J. Predictors of progression to severe Alzheimer's disease in an incidence sample. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2013;9(2):204–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.01.003. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodakowski J, Saghafi E, Butters MA, Skidmore ER. Nonpharmacological interventions for adults with mild cognitive impairment and early stage dementia: An updated scoping review. Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 2015;43-44:38–53. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2015.06.003. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2015.06.003 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovner BW, Casten RJ, Leiby BE. Determinants of activity levels in African Americans with mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 2015 doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000096. doi:10.1097/WAD.0000000000000096 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovner BW, Casten RJ, Hegel MT, Leiby BE. Preventing cognitive decline in older African Americans with mild cognitive impairment: Design and methods of a randomized clinical trial. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2012;33(4):712–720. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.02.016. doi:10.1016/j.cct.2012.02.016 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santor DA, Coyle JC. Shortening the CES-D to improve its ability to detect cases of depression. Psychological Assessment. 1997;9:233–243. PMCID: Not available. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider L, Lyketsos C, Davis K, Hsiao J, Katz I, Pollock B, Lebowitz B. National Institute of Mental Health Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE). The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2001;9(4):346–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Gallagher-Thompson D, Haley WE, Czaja S. Understanding the intervention process: A theoretical/conceptual framework for intervention approaches to caregivers. In: Schulz R, editor. Handbook on dementia caregiving: Evidence-based interventions for family caregivers. Springer Publishing Company; New York: 2000. pp. 33–60. [Google Scholar]

- Small GW. Treating dementia and agitation. Jama. 2014;311(7):677–678. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.94. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.94 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly M, Zbrozek A, Dukes E. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment measure. PharmacoEconomics. 1993;4(5):353–65. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199304050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenheck R, Leslie D, Sindelar J, Miller E, Lin H, Stroup T, CATIE Study Investigators Cost-effectiveness of second-generation antipsychotics and perphenazine in a random trial of treatment for chronic schizophrenia. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(12):2080–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.12.2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenheck R, Leslie D, Sindelar J, Miller E, Tariot P, Dagerman K, Clinical Antipsychotic Trial of Intervention Effectiveness-Alzheimer's Disease (CATIEAD) investigators Cost-benefit analysis of second-generation antipsychotics and placebo in a randomized trial of the treatment of psychosis and aggression in Alzheimer's disease. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64(11):1259–68. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.11.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The EuroQol Group EuroQol-a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16(3):199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trahan MA, Kuo J, Carlson MC, Gitlin LN. A systematic review of strategies to foster activity engagement in persons with dementia. Health Education & Behavior. 2014;41(1 Suppl):70S–83S. doi: 10.1177/1090198114531782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics [01/06/2015];Wage data by area and occupation. Available at: http://www.bls.gov/bls/blswage.htm.

- van Hout B, Janssen MF, Feng YS, Kohlmann T, Busschbach J, Golicki D, Pickard AS. Interim scoring for the EQ-5D-5L: Mapping the EQ-5D-5L to EQ-5D-3L value sets. Value in Health: The Journal of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. 2012;15(5):708–715. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2012.02.008. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2012.02.008 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimo A. The Health Economics of Dementia. John Wiley & Sons; London: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wimo A, Gustavsson A, Jönsson L, Winblad B, Hsu M, Gannon B. Application of Resource Utilization and Dementia (RUD) instrument in a global setting. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2013;9(4):429–435. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimo A, Jönsson L, Zbrozek A. The Resource Utilization in Dementia (RUD) instrument is valid for assessing informal care time in community-living patients with dementia. The Journal of Nutrition Health and Aging. 2010;14(8):685–90. doi: 10.1007/s12603-010-0316-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimo A, Nordberg G. Validity and reliability of assessments of time: comparisons of direct observations and estimates of time by the use of the resource utilization in dementia (RUD)-instrument. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2007;44(1):71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimo A, Winblad B. Resource Utilization in Dementia: RUD lite. Brain Aging. 2003;3(1):48–59. [Google Scholar]