Abstract

Heterotopic ossification (HO) consists of ectopic cartilage and bone formation following severe trauma or invasive surgeries, and a genetic form of it characterizes patients with Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva (FOP). Recent mouse studies showed that HO was significantly inhibited by systemic treatment with a corticosteroid or the retinoic acid receptor γ agonist Palovarotene. Because these drugs act differently, the data raised intriguing questions including whether the drugs affected HO via similar means, whether a combination therapy would be more effective or whether the drugs may hamper each other's action. To tackle these questions, we used an effective HO mouse model involving subcutaneous implantation of Matrigel plus rhBMP2, and compared the effectiveness of prednisone, dexamathaosone, Palovarotene or combination of. Each corticosteroid and Palovarotene reduced bone formation at max doses, and a combination therapy elicited similar outcomes without obvious interference. While Palovarotene had effectively prevented the initial cartilaginous phase of HO, the steroids appeared to act more on the bony phase. In reporter assays, dexamethasone and Palovarotene induced transcriptional activity of their respective GRE or RARE constructs and did not interfere with each other's pathway. Interestingly, both drugs inhibited the activity of a reporter construct for the inflammatory mediator NF-κB, particularly in combination. In good agreement, immunohistochemical analyses showed that both drugs markedly reduced the number of mast cells and macrophages near and within the ectopic Matrigel mass and reduced also the number of progenitor cells. In sum, corticosteroids and Palovarotene appear to block HO via common and distinct mechanisms. Most importantly, they directly or indirectly inhibit the recruitment of immune and inflammatory cells present at the affected site, thus alleviating the effects of key HO instigators.

Keywords: Heterotopic ossification, chondrogenesis, osteogenesis, retinoid agonists, anti-inflammatory drugs, progenitor cells, inflammatory cells

Introduction

Heterotopic ossification (HO) is a common, potentially debilitating, acquired disorder in which ectopic masses of endochondral and intramembranous bone form and accumulate within muscle and connective tissues, around joints, near blood vessels, subcutaneously or in other locations [1-3]. The extraskeletal bone can hamper routine daily functions and mobility, and can also cause chronic pain, formation of pressure ulcers, venous thrombosis and other complications [4]. HO is induced and propelled by trauma, burns, protracted immobilization and major surgeries [5, 6]. Given the nature of such inciting events, HO has been found to be particularly common in severely wounded soldiers returning from war [7-9]. The pathogenesis of HO remains unclear, but it is thought that trauma, burns and other inflammatory and non-inflammatory events lead to recruitment of local and distant progenitor cells, production and release of pro-skeletogenic factors, formation of ectopic cartilage and bone, and establishment of the extraskeletal heterotopic bone mass [10-13]. There is also a rare and exceedingly severe genetic form of HO that occurs in patients with Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva (FOP) [14]. Patients with FOP carry activating mutations in ACVR1 that encodes the type I bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) receptor ALK2 [15, 16]. About 13 mutations have been identified so far, with the most common one being ACVR1R206H which characterizes patients with classic FOP [15, 16]. All ALK2 mutants have been found to stimulate chondrogenic and osteogenic cell differentiation in vitro and to induce ectopic cartilage and bone formation when experimentally mis-expressed in animal models [17-20], thus likely representing a key mechanism inciting heterotopic cartilage and bone formation. FOP patients begin to develop HO at a young age, and a local flare-up involving tissue swelling, pain and redness usually precedes the initiation of the HO process [14, 21]. Unrelenting accumulation of HO at multiple sites over postnatal life leads to progressive paralysis and eventually premature death in most of these patients [21].

Current treatments for acquired forms of HO include systemic administration of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), local prophylactic low-dose irradiation limited to the involved site, or combination of both interventions [22-24]. NSAIDs inhibit the synthesis of both physiologic and inflammatory prostaglandins [25], and animals treated with the NSAID indomethacin were found to be more resistant to experimental HO induced by injury or intramuscular injection of recombinant BMPs and to display reduced skeletal cell differentiation [26, 27]. Local irradiation is thought to act more broadly on mesenchymal cells present in several tissues, to block their functioning and survival, and to ultimately reduce their ability to undergo skeletogenic differentiation [23, 28, 29]. These standard treatments are associated with a reduced incidence of HO, but are not always effective and cannot be given in certain circumstances such as after combat-related injuries [22-24]. In addition, NSAIDs can elicit well-known side effects that include gastrointestinal pain and ulceration, renal toxicity and lower platelet function [23], often reducing patient compliance [30]. Surgery is also used to remove the HO tissue, but it requires further hospitalization and can cause complications including infections, blood loss and even another round of HO [31, 32]. At present, there are even fewer therapeutic options for FOP children [33]. HO in FOP patients is exceedingly reactive and aggressive, and surgery cannot be used and is strictly avoided since it instigates far more serious HO. Because HO in FOP patients is most often preceded by local flare-ups, the current standard of care includes a brief 4-day course of high-dose corticosteroids initiated within 24 hr of a flare-up [33]. Though the steroid treatment can and does mitigate inflammation and pain, it is not able to consistently reduce progression to HO [21]. In sum, new and more effective treatments are needed for both acquired and congenital HO.

In recent studies from our laboratories, we have shown that synthetic retinoid agonists represent a new class of pharmaceuticals against HO in injury and genetic mouse models [34, 35]. Normally, endogenous retinoids such as all-trans-retinoic acid serve as ligands for, and transcriptional activators of, the nuclear retinoic acid receptors (RARα, RARβ and RARγ) in many tissues and organs and regulate major developmental and postnatal processes and events [36-38]. The rationale behind our therapeutic strategy was based on studies showing that: chondrogenic cell differentiation in vitro and in vivo actually requires a significant drop in endogenous retinoid signaling and RAR gene expression [39, 40]; endogenous retinoid levels are quite low in cartilage [41-43]; and exogenous retinoid agonists are potent inhibitors of chondrogenesis [44]. We found that systemic administration of a selective agonist for RARα or RARγ reduced HO in mouse subdermal and intramuscular injury models and in a genetic model expressing an inducible and constitutive-active ACVR1Q207D mutant transgene, with the RARγ agonists appearing more effective [34, 35]. Notably, the same transgenic mouse model had previously been used by Yu et al. to test other drugs to inhibit HO, including dexamethasone [19]. The authors found that ectopic calcification and limb impairment caused by ACVR1Q207D over-expression and tissue injury were reduced in corticosteroid-treated mice versus vehicle-treated mice. Considered together, the above studies raise intriguing and important questions and in particular whether retinoid agonists and corticosteroids inhibit HO via similar or dissimilar means, whether a combination therapy would be more beneficial and effective or whether the drugs may actually hamper each other's action. The present study was carried out to tackle these important issues.

Materials and methods

HO mouse model

All mouse studies were conducted after review and approval by the IACUC and fully complied with the ARRIVE guidelines. Accordingly, we used our standard, sensitive and convenient model of subcutaneous HO mouse that is mild and non invasive [45] as described previously [34]. Briefly, mixtures of growth factor-reduced Matrigel (Corning, NY, USA) and recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 (rhBMP2; Gene Script Corp., NJ, USA) were prepared on ice, and 250 μl aliquots containing 1 μg of rhBMP2 were injected at two ventral subcutaneous sites in 6-8 week-old CD-1 female mice averaging a weight of 25 grs. Female mice were used because they are easier to handle and elicit a consistent HO process indistinguishable from that in males [35]. Subcutaneous implantations were carried out under anesthesia by inhalation of 1.5% isoflurane in 98.5% oxygen as prescribed by IACUC. Following implantation, mice were randomized into control and experimental groups to minimize bias. Institutional LAS personnel provided animal housing and care.

Drug Administration

Stock solutions of the RARγ agonist Palovarotene, also known as R667, (Atomax Chemicals Co., Shenzhen, China), prednisone and dexamethasone (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) were prepared in DMSO and stored at −30°C under argon. Just before oral administration, 30 μl aliquots in DMSO was mixed with 70 μl of corn oil to obtain a 100 μl mixture used for each gavage according to IACUC instructions. Daily gavage administration started on the afternoon of day 1 from Matrigel/rhBMP2 implantation and continued until day 10 unless otherwise noted. When mice received a combination of two drugs, each drug was prepared in 50 μl of total gavage solution (15 μl of drug dissolved in DMSO mixed with 35 μl of corn oil) such that the total volume per gavage (100 μl) was kept constant. Control mice received similar mixtures of DMSO and corn oil without drug(s). No adverse effects were noted in control and treated animals during the course of experimentation.

Imaging and quantification by micro computed tomography (μCT)

Tissue samples were fixed in 10% formalin overnight and stored in PBS at 4°C. Analysis by μCT was performed using vivaCT 40 scanner (SCANCO USA, Southeastern, PA ) at 19 μm resolution, 200 ms integration time, 55 kVp energy and 145 μA intensity. Samples were analyzed at threshold 33 to measure total tissue volume (TV) and then re-analyzed at threshold 125 to measure bone volume (BV). Data were used to calculate bone volume/total volume (BV/TV) ratios and are presented in relation to control values. These ratios were calculated based on averages obtained by multiple samples from at least two independent experiments involving 4 to 6 mice per experimental group.

Histological and immunohistochemical analyses

HO samples were harvested on day 12, fixed overnight in 10% formalin, washed in PBS and then decalcified in 10% EDTA for 2 weeks followed by processing in Lynx II tissue processor (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA) [34, 35]. Samples harvested at day 4 and day 7 from Matrigel implantation were in 10% formalin overnight, but were immediately subjected to processing without decalcification. Fixed samples were embedded in paraffin, and 4.0 μm cross sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for routine histology, Alcian blue to reveal cartilage and toluidine blue to reveal the mast cells. Alcian blue-positive areas were quantified by Image J as described previously [46]. For immunohistochemistry, paraffin sections were deparaffinized and then hydrated in water. Sections were then autoclaved at 121°C for 10 minutes in 10 mM citrate buffer solution for antigen retrieval. The endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 10 mins. Sections were then rinsed in water and TBS and were blocked with 10% BSA and 1% goat serum in PBS for 30 mins. Sections were incubated with rabbit monoclonal anti-mouse F4/80/EMR1 primary antibody (1:100; Novus Biologicals, cat. No. NBP2-12506, Littleton, CO, USA) diluted in 1%BSA in PBS overnight at 4°C. Bound antibodies were detected by incubation with biotinylated rabbit secondary antibodies (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for 30 mins followed by ABC reaction (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA).

Blood tests

Blood samples were collected via retro-orbital bleeding following IACUC approved protocols. Briefly, mice were anesthetized and the head was held firm by gentle finger pressure. The tip of a non-heparinized capillary tube was placed at the medial canthus of the eye. A short thrust was slowly applied and as the sinus was punctured, blood was collected by capillary action (about 250 μl per mouse). Mice were immediately sacrificed after blood collection. Blood samples were transferred on ice to the Ryan Veterinary Hospital Laboratory at the University of Pennsylvania where basic blood chemistry analyses were performed by routine procedures. Only most representative and relevant data were chosen for inclusion and analysis here.

Primary cell cultures

Bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) were isolated from 6-8 weeks old C57BL6 mice as described [47]. Briefly, femurs and tibia were isolated and freed of surrounding tissues as thoroughly as possible. While holding each of them firmly with forceps, the epiphyseal ends were cut off with sharp disposable scissors, and bone marrow was immediately flushed out with a syringe using HBSS containing 2x Penicillin-Streptomycin mixture and was collected in 15 ml culture tube. Cells were collected by centrifugation at 400g for 10 min, rinsed three times with HBSS, re-suspended in 10 ml of complete tissue culture DMEM medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin mixture, and finally seeded in a 10 cm tissue culture plate. On day 3 of incubation, non-adherent cells were removed by rinsing 2 or 3 times with HBSS, and the adherent cells were then maintained in complete growth medium and serial sub-culturing.

Reporter assays

BMSCs were cultured for several passages to reduce presence of other cell types, and BMSCs from passage 10 to 12 were used in the present study. When the cells were about 70% confluent, they were detached by trypsinization and reverse-transfected by seeding 0.5 × 104 of them in 96 well plates with 200 ng/well of RARE-luc, GRE-luc or NF-κB-luc plasmids (Clonetech Labs, Mountain View, CA, USA) mixed with 0.4 μl of P-3000 reagent and 1 μl of lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). After 16 hours, cells were treated with: Palovarotene at 15 nM, 60 nM and 125 nM; dexamethasone at 10 nM, 30 nM and 100 nM; or combination of. Cells were lysed with 25 μls of Passive lysis buffer, and reporter activity was measured after 24 hrs of drug treatment, using a single luciferase kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). For measuring transcriptional activity of NF-κB reporter, BMSCs were treated with recombinant mouse IL-1β (R & D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) at a final concentration of 3 ng/ml in each well in the absence or presence of above drugs as indicated.

Statistical procedures

Results were analyzed using One-way analysis of variance followed by post-hoc tests using GraphPad Prism 6.0 (La Jolla, CA). In most experiments, the post-hoc test used was Dunnett. A statistical variance of p<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Single versus combination drug treatment in a mouse HO model

In our recent studies, we used an efficient and popular subcutaneous mouse model of HO [45] to determine and compare the ability of different synthetic retinoid agonists to inhibit this pathological process [34, 35]. In particular, we had found that oral treatment with the RARγ agonist Palovarotene at 0.4 mg/kg body weight/day moderately inhibited HO formation by day 12 as indicated by μCT and histological analyses, while a higher dose at 4.0 mg/kg/day was more effective. Here, we used those findings as a point of reference to determine whether prednisone alone or in combination with Palovarotene would elicit similar or dissimilar degrees of HO inhibition in this subcutaneous mouse model. Accordingly, 6-8 week-old female CD-1 mice were injected with a 250 μl mixture of Matrigel and 1.0 μg rhBMP2 at two neighboring ventral subdermal sites that produced well defined round-to-oval gelified Matrigel masses eliciting local swelling, some tissue disruption and likely inflammation. Mice were returned to their cages and randomized. On day 1 from Matrigel injection, groups of 4 to 6 mice each were subjected to gavage administration of Palovarotene (0.4 or 4.0 mg/kg/day), prednisone (10 mg/kg/day) or prednisone combined with Palovarotene at 0.4 or 4.0 mg/kg/day. Companion control mice received vehicle. Drug doses were based on previous mouse studies [19] and also considering mouse-to-human drug equivalent doses (http://www.fda.gov/cber/gdlns/dose.htm). The resulting 6 groups of mice then received daily doses of drug or vehicle and were sacrificed on day 12 at which point the ectopic tissue masses were harvested and subjected to μCT. As expected, samples from vehicle-treated control mice displayed very abundant mineralized tissue and a conspicuous size, reaffirming the efficiency of HO formation in this model (Fig. 1A-C). When given at a low dose, Palovarotene moderately inhibited mineralized tissue formation (Fig. 1D-F), but was more effective at the higher dose (Fig. 1G-I). Interestingly, prednisone by itself elicited a significant inhibition of mineralized tissue formation (Fig. 1J-L) and such degree of effectiveness was not significantly modulated in combination with Palovarotene at either low or high dose (Fig. 1M-O and 1P-R, respectively). Overall trends and data were affirmed by quantification of μCT scans and calculation of BV/TV ratios (Fig. 1S). While prednisone is commonly used in patient care including FOP patients, the corticosteroid more commonly used in mouse studies is dexamethasone. Thus, we carried out an analogous series of experiments using this steroid by itself or in combination with Palovarotene, and the data obtained closely mirrored those obtained with prednisone (Fig. 1T).

Fig. 1.

Effects of single or combination treatments on formation of ectopic mineralized tissue masses. (A-R) Representative μCT images of ectopic tissue masses present in 3 mice per treatment group (out of 10 total mice/group) on day 12 after daily oral administration of different drugs as follows: (A-C), Vehicle control; (D-F) and (G-I), Palovarotene (Palo) at 0.4 or 4.0 mg/kg/day, respectively; (J-L) Prednisone (Pred) at 10 mg/kg/day; (M-O) and (P-R), Prednisone at 10 mg/kg/day plus Palovarotene at 0.4 or 4.0 mg/kg/day, respectively. (S) Histograms representing quantification of bone volume over total volume (BV/TV) ± S.E.M. in each sample group by μCT analysis. (T) Quantification of BV/TV in ectopic masses from mouse groups treated with dexamethasone (rather than prednisone) alone or in combination with Palovarotene. Data from two independent experiments (n=10-12) were used for calculation of averages and statistical significance in (S) and (T). *p=< 0.05; **p=<0.01; ***p=<0.001. Bar in μCT panels, 1 mm.

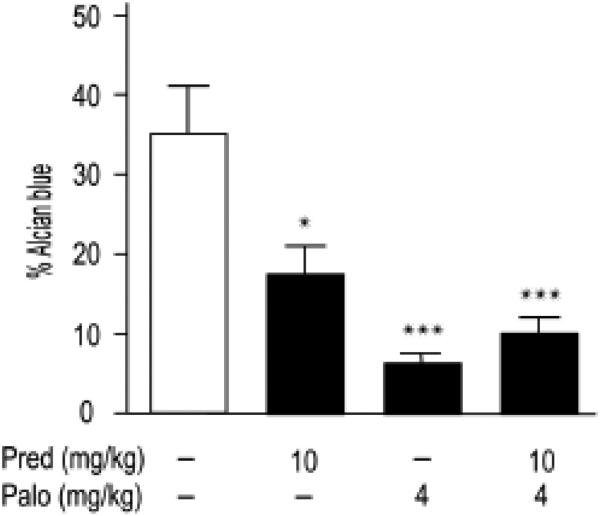

The HO process in FOP patients is often initiated, and probably triggered by, a flare-up with tissue swelling and redness and then proceeds by a seemingly stereotypic endochondral process [48] similar to that occurring during normal skeletal development; the process involves the initial formation of cartilage that undergoes hypertrophy, is invaded by blood vessels and osteoprogenitors, is mineralized and is finally replaced by bone and marrow [49]. The same cascade of events usually accompanies acquired forms of HO also [5]. Thus, it was important to determine whether the inhibition of HO by the corticosteroids with or without Palovarotene measured by μCT imaging above had occurred at the level of chondrogenesis and/or at the later developmental stage of tissue mineralization. Thus, we prepared serial sections of ectopic masses on day 7 and 12 from Matrigel implantation and stained them with Alcian blue, focusing on sections in the medial and largest portion of each mass. ImageJ computation of Alcian blue-positive areas on day 7 showed that control masses contained very large amounts of cartilage (Fig. 2) as to be expected [34, 35]. Treatment with dexamethasone or prednisone (each at 10 mg/kg/day) decreased the overall cartilage tissue area by over 60%, whereas Palovarotene (4 mg/kg/day) alone or in combination with either steroid had reduced it by over 80% (Fig. 2). By day 12 in controls, the cartilage area was reduced as it was undergoing its normal transition to endochodral bone (not shown). Similar trends were observed in the treated samples.

Fig. 2.

Fraction of cartilaginous tissue areas within ectopic Matrigel tissue masses. Samples were harvested on day 7 from control and treated mice and were serially sectioned and stained with alcian blue to reveal cartilaginous tissue. A minimum of 5 to 6 serial sections per sample were examined, and ImageJ was used to determine total cartilaginous area over total tissue area. Histograms represent averages ± S.E.M. from 3 independent experiments (n= 3). *p=< 0.05; ***p=<0.001.

Cellular levels of drug action

Retinoids and corticosteroids are very distinct molecules chemically and biologically and act by interacting with their respective nuclear receptors and altering expression of target genes [37, 50]. Retinoids interact with heterodimer RAR-RXR receptor complexes, whereas corticosteroids interact with homodimer GR receptor complexes [37], and both types of receptors require common co-activators such as CBP and p300 [51, 52], Thus, it was of interest to study whether Palovarotene and the two corticosteroids could individually inhibit HO with any interaction or without obvious interference. To clarify their respective action, we asked whether the drugs would nonetheless affect the transcriptional activities of reporter constructs containing their respective DNA response elements. Given that progenitors involved in HO formation have multiple origin [53, 54], we used primary cultures of bone marrow stromal cells as a surrogate model system. Cells were reverse-transfected with luciferase reporter plasmids containing retinoic acid response elements (RARE), glucocorticoid response elements (GRE) or NF-κB response elements. The latter was included as a measure of involvement in inflammatory responses [55] that usually accompany inception and progression of HO. After 12 hrs from transfection, the cells were treated with different concentrations of Palovarotene (15 to 125 nM) and dexamethasone (10 to 100 nM) singly or in combination for 24 hrs. Cells were homogenized with passive lysis buffer, and reporter activity was measured using luciferase assay kits as per manufacturer's instructions. Palovarotene treatment increased RARE reporter activity nearly 3 fold at 15 or 60 nM doses (Fig. 3A) which are doses in the physiologic range [56], and activity was not affected by higher Palovarotene doses nor co-treatment with dexamethasone at any concentration tested (Fig. 3A). GRE response activity was dose-dependently increased by dexamethasone treatment, reaching a maximum at 30 nM (Fig. 3B), and these trends were not significantly changed by co-treatment with Palovarotene (Fig. 3B). Of considerable interest were the results of NF-κB responsiveness. The activity of the NF-κB reporter construct was increased over 10-fold by exposing the cells to the inflammatory cytokine IL-1β as to be expected [57]. Treatment with 100 nM dexamethasome did significantly reduce the IL-1β-induced reporter activity, but so did treatment with 60 or 125 nM Palovarotene (Fig. 3C). The strongest reduction in IL-1β-elicited reporter activity was observed after combined treatment with dexamethasone plus Palovarotene (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Transfection assays using RARE, GRE and NF-κB reporters. (A-B) Primary stromal cell cultures transfected with (A) RARE-luc or (B) GRE-luc reporter constructs were treated with different doses of Palovarotene, dexamethasone or combination of for 24 hrs and processed for determination of luciferase activity, using a single reporter assay. Histograms represent data ± S.E.M. relative to controls that were set to 1. (C) Companion cultures transfected with NF-κB-luc reporter plasmid were treated with 3 ng/ml of IL-1β and then exposed to indicated concentrations of Palovarotene, dexamethasone or combination of for 24 hrs, and finally processed for reporter assays as above. Data are from a representative experiment with n= 5. Each experiment was independently repeated a minimum of 4 times. Ns, not statistically significant; *p=< 0.05; ***p=<0.001.

Cellular migration and invasion and HO genesis

By being an ectopic and invasive process, HO involves recruitment and migration of progenitors to the affected site promoted and propelled by local inflammation and other as yet unknown cues [54, 58]. Given the above results suggesting that dexamethasone and Palovarotene reduced inflammatory responses as indicated by NF-κB reporter activity, it became of interest to analyze how the drugs affected the HO process at the level of migration and recruitment of progenitors and other cells including vascular and immune cells. To this end, we monitored the histological organization and features of the ectopic masses at day 4, day 7 and day 12 from Matrigel/rhBMP2 implantation in control mice and companion mice treated with Palovarotene (4.0 mg/kg/day), prednisone (10 mg/kg/day) or combined drugs, paying particular attention to the border between the Matrigel tissue mass and surrounding host tissues. In controls at day 4, the border was very cellular, but relatively few cells had penetrated -and could be identified within- the Matrigel (Fig. 4A). By day 7, however, the border had become much more crowded and compacted, many cells had penetrated the Matrigel, and cartilage was obvious and abundant (Fig. 4B). By day 12, the control ectopic mass had acquired its endochondral nature rich in bone, marrow and remnants of cartilage and with the border now integrated into, and difficult to distinguish from, host tissues (Fig. 4C). Of interest was the finding that in day 4 and day 7 samples from mice treated with Palovarotene, prednisone or both, there was a paucity of cells within the Matrigel and the few present appeared to be distributed in various directions (Fig. 4DE, G-H and J-K, respectively). One distinct and clear difference was that the cells in the prednisone samples were mostly round in shape and organized in rows (Fig. 4D-E), while those in Palovarotene samples were flat and spindle-shaped (Fig.4G-H), reminiscent of the effects retinoid agonists have in cultured cells [59]. By day 12, the samples had become heterogeneous histologically due to the limited amount of ectopic tissue formation, and the prednisone samples contained some cartilage remnants (Fig. 4F, arrowhead) while the Palovarotene samples mostly had scattered cells (Fig. 4I). The combination treatment had even more profound inhibitory effects on these developmental trends, and scanty cells and tissues were observable at each time point (Fig. 4J-L). Notably, there were appreciable numbers of adipocytes in the samples from prednisone-treated mice on day 12 (Fig. 4F, arrow), in line with studies indicating that corticosteroids can promote adipogenic cell differentiation [60, 61].

Fig. 4.

Histological assessment of ectopic mass tissue development over time. (A-L) Serial sections were prepared through the central largest portion of the ectopic Matrigel masses present on days 4, 7 and 12 in mice treated with: (A-C) vehicle control; (D-F) Prednisone (Pred) at 10 mg/kg/day; (G-I) Palovarotene (Palo) at 4.0 mg/kg/day; and (J-L) combination of both drugs. Representative images are shown. Note that in controls (A-C), the outer border and peripheral portion of the Matrigel masses became occupied by numerous cells that invaded the Matrigel and differentiated in cartilage and bone by day 7 and 12. In comparison, both the outer border and periphery of the Matrigel remain sparsely populated in treated mice (D-L), particularly so in those receiving combination therapy (J-L). Note the appreciable number of adipocytes in the masses from Pred-treated mice (F, arrow). Scale bar, 100 μm.

To further characterize the cells near and around the border, we processed serial sections of day 4, 7 and 12 samples to immunostaining with antibodies specific for mast cells which are thought to be particularly relevant to the initiation of the HO process [12, 62]. Inhibition of mast cell degranulation has in fact been found to reduce experimental HO [63]. Immunostaining data analysis and quantification indicated that there was a readily appreciable number of mast cells in control samples at each time point examined, but particularly so at the earlier time points and around the border and periphery of the ectopic masses (Fig. 5 and Supplemental Table 1). However, the number of detectable mast cells was clearly lower in samples from drug-treated mice, with no major difference between mice receiving a single drug or combination treatment (Fig. 5B-D and 5E-G). To further probe these observations, we processed similar serial sections for analysis of macrophages that are also thought to play roles in HO [64, 65]. Using the macrophage marker F4/80 [66], we found that the number of these cells was markedly reduced in specimens from treated versus control mice (Fig. 6A-G and Supplemental Table 1).

Fig. 5.

Detection and quantification of mast cells. (A-D) Serial sections were stained with toluidine blue to reveal mast cells present around the outer border and peripheral area of Matrigel masses on day 4 in mice treated with: (A) vehicle control; (B) Prednisone (Pred) at 10 mg/kg/day; (C) Palovarotene (Palo) at 4.0 mg/kg/day; and (D) combination of both drugs. Inset in (A) shows a high magnification image of a mast cell exhibiting a typical intense vacuolar cytoplasmic staining. (E-G) Histograms showing average number of toluidine blue-positive mast cells per area ± S.E.M. in serial sections of ectopic masses present in drug-treated mice on days 4, 7 and 12 from Matrigel implantation relative to controls set to 1. For each group, 10 to 15 random images were analyzed from three independent samples. *p=< 0.05; **p=<0.001; ****p=<0.0001.

Fig. 6.

Detection and quantification of macrophages. (A-D) Serial sections were immunostained with F4/80 marker to reveal macrophages present around the outer border and peripheral area of Matrigel masses present on day 7 in mice treated with: (A) vehicle control; (B) Prednisone (Pred) at 10 mg/kg/day; (C) Palovarotene (Palo) at 4.0 mg/kg/day; and (D) combination of both drugs. (E-G) Histograms showing the average number of F4/80-positive macrophages per area ± S.E.M. in serial sections of ectopic masses present in drug-treated mice on day 4, 7 and 12 from Matrigel implantation relative to controls set to 1. For each group, an average of 10 images were analyzed from two independent samples. **p=<0.01; ***p=<0.001; ***p=<0.0001.

Body weight and blood chemistry

In our previous studies on HO and retinoid treatment [35], we monitored body weight, blood chemistry and other general parameters to assess whether drug treatment may have elicited unwanted side effects [35]. We found that Palovarotene, dexamethasone and prednisone singly or in combination did not change appreciably mouse body weight at any time point during the treatment period (Fig. 7), and general blood parameters were all normal except for a slight change in liver function markers in Palovarotene-treated mice (not shown). Liver is a main metabolizing and storage organ for retinoids [56] and is thus more sensitive.

Fig. 7.

Determination of body weight over time. Mice were implanted with Matrigel/rhBMP2, randomized and divided into subgroups each treated with vehicle control, one drug or combination drugs as indicated. Each mouse was weighted at the time of implantation and then at days 1, 5, 8 and 12. Data are from representative individual mice and show that whole body weight did not change appreciably during the 12 day treatment period.

Discussion

Our study provides clear evidence that dexamethasone, prednisone and Palovarotene are strong inhibitors of the otherwise rapid and efficient HO process triggered by Matrigel/rhBMP2 subcutaneous implantation in mice and do not appreciably interfere with each other's ultimate anti-HO effects when given in combination. Steroids and retinoids share the ability to act mainly at the nuclear level and exert their biological effects via interactions with their respective receptors and intervention by co-factors, but are otherwise very different agents with distinct chemistry and distinct overall functions [37, 67]. Our data indicate that these agents affect HO likely by acting on -and interfering with- distinct as well as common steps and phases that incite and sustain the extraskeletal heterotopic process. In terms of distinct action, our data suggest that Palovarotene inhibits HO by preventing chondrogenesis and cartilage formation [39, 44], whereas prednisone has a seemingly lower initial effect on cartilage formation but is more active against bone formation. Glucocorticoids have long been known to inhibit osteoblastogenesis, to induce apotosis of osteoblasts and osteocytes and to shift the progenitor cell differentiation balance toward adipogenesis and osteoclatogenesis [68, 69]. This is in line with our detection of obvious adipocytes scattered with the Matrigel masses in corticosteroid-treated mice. Thus, prednisone could have elicited its anti-HO effects by eliciting similar deranging effects on osteoblastogenesis and adipogenesis during the later phases of the HO process.

What about action on common steps? Our systematic morphological analyses of the HO process reveal that in control untreated mice, numerous cells had been recruited to -and around- the Matrigel implantation site and were actively invading the scaffold itself by day 4. As indicated by immunostaining, those cells certainly included mast cells and macrophages and could likely include also mesenchymal progenitors giving rise to cartilage and bone over time and angiogenic and vascular-associated cells to permit the replacement of cartilage with bone and marrow, in line with CD-31 immunostaining data (not shown). Following treatment with corticosteroids, Palovarotene or both, however, the surroundings and peripheral portion of the Matrigel scaffold were very poor in cells at day 4 as well as day 7. Why would such peripheral cell population be so reduced by drug treatment? It is possible that by reducing the initial number of mast cells and macrophages, both the corticosteroids and Palovarotene may have interrupted a key mechanism by which local and distant host cells are geared into action, sense the presence of growth factor gradients (such that elicited by the rhBMP2-loaded Matrigel scaffold), and migrate toward and gather around the scaffold. The initial inflammation may be needed to set this cascade in motion, for example via de-granulation of recruited mast cells [70]. Release of tumor necrosis factor by mast cells was shown to promote migration of dendritic cells into lymph nodes [71]. More generally, mast cells are well known for their roles in wound healing, tissue repair and angiogenesis by recruitment of progenitors at inflamed and damaged sites [70], and corticosteroids have been shown to reduce progenitor number at inflamed sites and tissues [72]. Clearly, the drugs may have hampered the release of cues that are needed by cells to migrate and navigate through matrix and tissues, and a decrease in mast cell number and activity could be an initial, important and comprehensive mechanism by which corticosteroids and Palovarotene inhibit HO. The apparent decrease in macrophage number could also have been aided as well. Indeed, genetic or pharmacologic depletion of macrophages has been shown to reduce HO in mice and to interfere also with osteoblastic differentiation and bone fracture repair [64, 65, 73].

Our plasmid reporter data provide additional important clues on common mechanisms of action. We find that while prednisone and Palovarotene increase the activity of their own reporter constructs as expected, they do not appreciably alter the response of each other's construct, reaffirming their independence at the transcriptional level of regulation. On the other hand, both drugs dampened the activity of the NF-κB reporter and did more so when given in combination, strengthening the argument that one common denominator in their action against HO may be inflammation. The ability of prednisone or dexamethasone to lower inflammation and inflammatory pathways is not at all surprising [74], but there is also evidence in literature dating back many years that retinoids can counter inflammation as well. For instance, all-transretinoic acid and its derivatives can reduce skin inflammation and are commonly used as topical treatments for acne [75]. This natural retinoid has also been found to reduce intestinal inflammation, to stabilize the function of T cells under other inflammatory conditions, and to improve inflammatory arthritis by reducing the production of inflammatory cytokines [76, 77]. Palovarotene itself has been tested in a phase 2 clinical trial for emphysema likely as a reflection of the ability of retinoid agonists in general to support and promote epithelial cell proliferation and differentiation and alveolar repair, but also for its possible anti-inflammatory action [78, 79].

As pointed out above, a short 4-day regimen of high-dose prednisone is currently recommended for FOP patients within 24 hrs of a flare-up, but continuous treatment is avoided because of the possible considerable side effects [33]. We tested a similar short-term treatment of prednisone in our HO system here and found that it had elicited only a moderate inhibition of HO by day 12 (not shown). We had previously shown that a short-term treatment with retinoid agonists produced a similar partial effect on HO [35]. Given the efficacy of prolonged corticosteroid treatment shown here and in previous studies [19], it could be desirable to use it in patients in certain specific circumstances, but this would depend on finding ways to reduce side effects. One possibility would be to define the minimal combined doses of Palovarotene plus a corticosteroid that elicit maximal HO inhibition and then determine whether this combination has fewer side effects long term or could be even used chronically as a maintenance treatment. Interestingly, a just published study has described a new pathogenic aspect of HO in FOP and a new possible treatment, using a conditional ACVR1R206H FOP mouse model [80]. The authors found that mutant ALK2R206H responded to the normally antagonistic ligand Activin A and signaled via canonical pSmad1/5/8 and that HO in the FOP mice was inhibited by treatment with neutralizing antibodies to Activin A. Though it remains to be established whether the Activin A antibodies would stop HO in FOP patients and do so safely, the study is exciting and establishes a concrete link between inflammation and HO, given that activins are normally produced by inflammatory cells [81]. Palovarotene and other retinoid agonists block canonical BMP signaling [35, 39] and thus, the study suggests that Palovarotene inhibits HO by blocking also BMP signaling induced by Activin A via mutant ALK2, reaffirming its encompassing potency. Together, all the above studies and the present one strongly demonstrate that progress is rapidly being made and that effective and safe single or combination measure(s) against acquired and congenital HO are likely to be within reach.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

-Heterotopic ossification (HO) is a pathology triggered by injury or mutations for which there is no definitive treatment

-Corticosteroids and retinoid agonists have been shown to dampen HO, but not fully

-Here we studied how these diverse drugs act on this pathology

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Grants H81XWH-13-2-0076 from the Department of Defense and NIH AR056837. We would like to thank Wei-Ju (Louis) Tseng for assistance with μCT analysis and the Penn Center for Musculoskeletal Disorders supported by NIH P30AR 050950 for the core facilities.

Abbreviations

- HO

heterotopic ossification

- FOP

Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva

- RAR

retinoic acid receptor

- BMP

bone morphogenetic protein

- GRE

glucocorticoid response element

- RARE

retinoic acid response element

- ACVR1

activin receptor 1

- ALK2

activin receptor-like kinase-2

- NSAIDs

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ahrengart L. Periarticular heterotopic ossification after total hip arthroplasty. Risk factors and consequences. Clin. Orth. Relat. Res. 1991;263:49–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garland DE. A clinical prospective on common forms of acquired heterotopic ossification. Clin. Orthop. 1991;263:13–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Subbarao JV, Garrison SJ. Heterotopic ossification: diagnosis and management, current concepts and controversies. J. Spinal Cord Med. 1999;22:273–283. doi: 10.1080/10790268.1999.11719580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shehab D, Elgazzar AH, Collier BD. Heterotopic ossification. J. Nucl. Med. 2002;43:346–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCarthy EF, Sundaram M. Heterotopic ossification: a review. Skeletal Radiol. 2005;34:609–619. doi: 10.1007/s00256-005-0958-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vanden Booshe L, Vanderstraeten G. Heterotopic ossification: a review. J. Rehabil. Med. 2005;37:129–136. doi: 10.1080/16501970510027628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans KN, Potter BK, Brown TS, Davis TA, Elster EA, Forsberg JA. Osteogenic gene expression correlates with development of heterotopic ossification in war wounds. Clin. Orth. Relat. Res. 2014;472:396–404. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3325-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forsberg JA, Potter BK. Heterotopic ossification in wartime wounds. J. Surg. Orthop. Adv. 2010;19:54–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Potter BK, Burns TC, Lacap AP, Granville RR, Gajewski DA. Heterotopic ossification following traumatic and combat-related amputations: prevalence, risk factors, and preliminary results of excision. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2007;89:476–486. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chalmers J, Gray DH, Rush J. Observation on the induction of bone in soft tissues. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 1975;57:36–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pape HC, Marsh S, Morley JR, Krettek C, Giannoudis PV. Current concepts in the development of heterotopic ossification. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 2004;86:783–787. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.86b6.15356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reichel LM, Salisbury E, Moustoukas MJ, Davis AR, Olmsted-David E. Molecular mechanisms of heterotopic ossification. J. Hand Surg. Am. 39:563–566. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2013.09.029. l2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shore E. Osteoinductive signals and heterotopic ossification. J. Bone Min. Res. 2011;26:1163–1165. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaplan FS, Le Merre M, Glaser DL, Pignolo RJ, Goldsby R, Kitterman JA, Groppe J, Shore E. Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2008;22:191–205. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shore E, Xu M, Feldman GJ, Fenstermacher DA, Consortium TFIR. Brown MA, Kaplan FS. A recurrent mutation in the BMP type I receptor ACVR1 causes inherited and sporadic fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Nature Genet. 2006;38:525–527. doi: 10.1038/ng1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whyte MP, Wenkert D, Demertziz JL, DiCarlo EF, Westenberg E, Mumm S. Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva: middle-age onset of heterotopic ossification from a unique missense mutation (c.974G > C, p.G325A) in ACVR1. J. Bone Min. Res. 2012;27:729–737. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Culbert AL, Chakkalakal SA, Theosmy EG, Breennan TA, Kaplan FS, Shore EM. Alk2 regulates early chondrogenic fate in Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva heterotopic endochondral ossification. Stem Cells. 2014;32:1289–1300. doi: 10.1002/stem.1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Dinther M, Visser N, de Gorter DJJ, Doorn J, Goumans M-J, de Boer J, ten Dijke P. ALK2 R206H mutation linked to fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva confers constitutive activity to the BMP type I receptor and sensitizes mesenchymal cells to BMP-induced osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. J. Bone Min. Res. 2010;25:1208–1215. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.091110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu PB, Deng DY. BMP type I receptor inhibition reduces heterotopic ossification. Nat. Med. 2008;14:1363–1369. doi: 10.1038/nm.1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang D, Schwarz EM, Rosier RN, Zuscik MJ, Puzas JE, O'Keefe RJ. ALK2 functions as a BMP type I receptor and induces Indian hedgehog in chondrocytes during skeletal development. J. Bone Min. Res. 2003;18:1593–1604. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.9.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shore EM, Kaplan FS. Inherited human diseases of heterotopic bone formation. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2010;6:518–527. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alfieri KA, Forsberg JA, Potter BK. Blast injuries and heterotopic ossification. Bone Joint Res. 2012;1:174–179. doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.18.2000102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sell S, Willms R, Jany R, Esenwein S, Gaissmaier C, Martini F, Bruhn G, Burkhardsmaier F, Bamberg M, Kusswetter W. The suppression of heterotopic ossifications: radiation versus NSAID therapy - A prospective study. J. Arthroplasty. 1998;13:854–859. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(98)90189-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teasell RW, Mehta S, Aubut JL, Ashe MC, Sequeira K, Macaluso S, Tu L, Team SR. A systematic review of the therapeutic interventions for heterotopic ossification after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2010;48:512–521. doi: 10.1038/sc.2009.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simmons DL, Botting RM, Hla T. Cyclooxygenase isozymes: the biology of prostaglandin synthesis and inhibition. Pharmacol. Rev. 2004;56:387–437. doi: 10.1124/pr.56.3.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DiCesare PE, Nimni ME, Pen L, Yazdi M, Cheung DT. Effects of indomethacin on demineralized bone-induced heterotopic ossification in the rat. J. Orthop. Res. 1991;9:855–861. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100090611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moed BR, Resnick RB, Fakhouri AJ, Nallamothu B, Wagner RA. Effect of two nonsteroidal antinflammatory drugs on heterotopic bone formation in a rabbit model. J. Arthoplasty. 1994;9:81–87. doi: 10.1016/0883-5403(94)90141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Craven PL, Urist MR. Osteogenesis by radioisotope labeled cell populations in implants of bone matrix under the influence of ionizing radiation. Clin. Orth. Relat. Res. 1971;76:231–233. doi: 10.1097/00003086-197105000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sautter-Bihl ML, Liebermeister E, Nanassy A. Radiotherapy as a local treatment option for heterotopic ossifications in patients with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2000;38:33–36. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karunakar MA, Sen A, Bosse MJ, Sims SH, Goulet JA, Kellam JF. Indometacin as prophylaxis for heterotopic ossification after the operative treatment of fractures of the acetabulum. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 2006;88:1613–1617. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B12.18151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meiners T, Abel R, Bohm V, Gerner HJ. Resection of heterotopic ossification of the hip in spinal cord injured patients. Spinal Cord. 1997;35:443–445. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Kuijk AA, Geurts AC, van Kuppevelt HJ. Neurogenic heterotopic ossification in spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2002;40:313–326. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaplan FS, Shore EM, Pignolo RJ. Clin. Proc. Intl. Clin. Consort. Vol. 4. FOP; 2011. The medical management of Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva: current treatment considerations. pp. 1–100. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shimono K, Morrison TN, Tung W-E, Chandraratna RAS, Williams JA, Iwamoto M, Pacifici M. Inhibition of ectopic bone formation by a selective retinoic acid receptor α-agonist: a new therapy for heterotopic ossification? J. Orthop. Res. 2010;28:271–277. doi: 10.1002/jor.20985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shimono K, Tung W-E, Macolino C, Chi A, Didizian JH, Mundy C, Chandraratna RAS, Mishina Y, Enomoto-Iwamoto M, Pacifici M, Iwamoto M. Potent inhibition of heterotopic ossification by nuclear retinoic acid receptor-γ agonists. Nature Med. 2011;17:454–460. doi: 10.1038/nm.2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duester G. Retinoic acid synthesis and signaling during early organogenesis. Cell. 134:921–931. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.002. l2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Evans RM, Mangelsdorf DJ. Nuclear receptors, RXR, and the big bang. Cell. 2014;157:255–266. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sucov HM, Evans RM. Retinoic acid and retinoic acid receptors in development. Mol. Neurobiol. 1995;10:169–184. doi: 10.1007/BF02740674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoffman LM, Garcha K, Karamboulas K, Cowan MF, Drysdale LM, Horton WA, Underhill TM. BMP action in skeletogenesis involves attenuation of retinoid signaling. J. Cell Biol. 2006;174:101–113. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weston AD, Chandraratna RAS, Torchia J, Underhill TM. Requirement for RAR- mediated gene repression in skeletal progenitor differentiation. J. Cell Biol. 2002;158:39–51. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200112029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koyama E, Golden EB, Kirsch T, Adams SL, Chandraratna RAS, Michaille J-J, Pacifici M. Retinoid signaling is required for chondrocyte maturation and endochondral bone formation during limb skeletogenesis. Dev. Biol. 1999;208:375–391. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Williams JA, Kane MA, Okabe T, Enomoto-Iwamoto M, Napoli JL, Pacifici M, Iwamoto M. Endogenous retinoids in mammalian growth plate cartilage. Analysis and roles in matrix homeostasis and turnover. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:36674–36681. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.151878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williams JA, Kondo N, Okabe T, Takeshita N, Pilchak DM, Koyama E, Ochiai T, Jensen D, Chu M-L, Kane MA, Napoli JL, Enomoto-Iwamoto M, Ghyselinck NB, Chambon P, Pacifici M, Iwamoto M. Retinoic acid receptors are required for skeletal growth, matrix homeostasis and growth plate function in postnatal mouse. Dev. Biol. 2009;328:315–327. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pacifici M, Cossu G, Molinaro M, Tato' F. Vitamin A inhibits chondrogenesis but not myogenesis. Exp. Cell Res. 1980;129:469–474. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(80)90517-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O'Connor JP. Animal models of heterotopic ossification. Clin. Orth. Relat. Res. 1998;346:71–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gutierrez ML, J. G, Barrera LA. Semi-automatic grading system in histologic and immunohistochemistry analysis to evaluate in vitro chondrogenesis. Vol. 17. Universitas Scientiarum; 2012. pp. 167–178. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nardi BN, Camassola M. Isolation and culture of rodent bone marrow-derived multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011;698:151–160. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-999-4_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaplan FS, Tabas JA, Gannon FH, Finkel G, Hahn GV, Zasloff MA. The histopathology of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. An endochondral process. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1993;75:220–230. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199302000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lefebvre V, Bhattaram P. Vertebrate skeletogenesis. Curr. Topics Dev. Biol. 2010;90:291–317. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(10)90008-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rochette-Egly C. Nuclear receptors: integration of multiple signalling pathways through phosphorylation. Cell. Signal. 2003;15:355–366. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(02)00115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barnes PJ. Anti-inflammatory actions of glucocorticoids: molecular mechanisms. Clin. Sci. 1998;94:557–572. doi: 10.1042/cs0940557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gillespie RF, Gudas LJ. Retinoid regulated association of transcriptional co-regulators and polycomb group proteins SUZ12 with the retinoid acid response element of Hoxa1, RARbeta(2), and Cyp26A1 in F9 embryonal carcinoma cells. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;372:298–316. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.06.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kan L, Kessler JA. Evaluation of the cellular origins of heterotopic ossification. Orthopedics. 2014;37:329–340. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20140430-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pignolo RJ, Foley KL. Nonhereditary heterotopic ossification. Clin. Rev. Bone Min. Met. 2005;3:261–266. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gilmore TD. Introduction to NF-kB: players, pathways, perspectives. Oncogene. 2006;25:6680–6684. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blaner WS, Olson JA. Retinol and retinoic acid metabolism. In: Sporn MB, Roberts AB, Goodman DS, editors. The retinoids: Biology, Chemistry, and Medicine. Second ed. Raven Press; New York, NY: 1994. pp. 229–255. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Garlanda C, Dinarello CA, Mantovani A. The interleukin-1 family: back to the future. Immunity. 2013;39:1003–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kaplan FS, Glaser DL, Hebela N, Shore EM. Heterotopic ossification. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2004;12:116–125. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200403000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Iwamoto M, Shapiro IM, Yagami K, Boskey AL, Leboy PS, Adams SL, Pacifici M. Retinoic acid induces rapid mineralization and expression of mineralization-related genes in chondrocytes. Exp. Cell Res. 1993;207:413–420. doi: 10.1006/excr.1993.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Atmani H, Chappard D, Basie MF. Proliferation an differentiation of osetoblasts and adipocytes in rat marrow stromal cell cultures: effects of dexamethasone and calcitriol. J. Cell. Biochem. 2003;89:364–372. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li J-S, Zhang N, Huang X, Xu J, Fernandes JC, Dai K, Zhang X. Dexamethasone shifts bone marrow stromal cells from osteoblasts to adipocytes by C/EBPalpha promoter methylation. Cell Death and Disease. 2013;4:e832. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gannon FH, Glaser DL, Caron R, Thompson LDR, Shore E, Kaplan FS. Mast cell involvement in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Hum. Pathol. 2001;32:842–848. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2001.26464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Salisbury E, Rodenberg E, Sonnet C, Hipp J, Gannon FH, Vadakkan TJ, Dickinson ME, Olmsted-David EA, Davis AR. Sensory nerve induced inflammation contributes to heterotopic ossification. J. Cell. Biochem. 2011;112:2748–2758. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Genet F, Kulina I, Vaquette C, Torossian F, Millard S, Pettit AR, Sims NA, Anginot A, Guerton B, Winkler IG, Barbier V, Lataillade J-J, Le Bousse-Kerdiles MC, Hutmacher DW, Levesque J-P. Neurological heterotopic ossification following spinal cord injury is triggered by macrophage-mediated inflammation in muscle. J. Pathol. 2015;236:229–240. doi: 10.1002/path.4519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kan L, Liu Y, McGuire TL, Berger DM, Awatramani RB, Dymecki SM, Kessler JA. Dysregulation of local stem/progenitor cells as a common cellular mechanism for heterotopic ossification. Stem Cells. 2009;27:150–156. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ji H, Cao R, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Iwamoto H, Lim S, Nakamura M, Andersson P, Wang J, sun Y, Dissing S, He X, Yang X, Cao Y. TNFR1 mediates TNF-a-induced tumor lymphangiogenesis and metastasis by modulating VEGF-CVEGFR3 signaling. Nat. Communications. 2014;5:4944. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Baker ME. Origin and diversification of steroids: co-evolution of enzymes and nuclear receptors. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2011;334:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Weinstein RS, Jilka RL, Parfitt aM, Manolagas SC. Inhibition of osteoblastogenesis and promotion of apoptosis of osteoblasts and osteocytes by glucocorticoids: potential mechanisms of their deleterious effects on bone. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;102:274–282. doi: 10.1172/JCI2799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yao W, Cheng Z, Busse C, Pham A, Nakamura MC, Lane NE. Glucocorticoid excess in mice results in early activation of osteoclastogenesis and adipogenesis and prolonged suppression of osteogenesis. Arthr. Rheum. 2008;58:1674–1686. doi: 10.1002/art.23454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.da Silva EZ, Jamur MC, Oliver C. Mast cell function: a new vision of an old cell. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2014;62:698–738. doi: 10.1369/0022155414545334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Suto H, Nakae S, Kakurai M, Sedgwick JD, Tsai M, Galli SJ. Mast cell-associated TNF promotes dendritic cell migration. J. Immunol. 2006;176:4102–4112. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.4102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.James A, Gylifors P, Henriksson E, Dahlen SE, Adner M, Nilsson G, Dahlen B. Corticosteroid treatment selectively decreases mast cells in the smooth muscle and epithelium of asthmatic bronchi. Allergy. 2012;67:958–961. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2012.02836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vi L, Baht GS, Whetstone H, Ng A, Wei QX, Poon R, Mylvaganam S, Grynpas M, Alman BA. Macrophages promote osteoblastic differentiation in vivo: implications in fracture repair and bone homeostasis. J. Bone Min. Res. 2014;30:1090–1102. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Barnes PJ. How corticosteroids control inflammation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2006;148:245–254. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Weiss JS. Current options for the topical treatment of acne vulgaris. Pediatr. Dermatol. 1997;14:480–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1997.tb00696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mielke LA, Jones SA, Raverdeau M, Higgs R, Stefanska A, Groom JR, Misiak A, Dungan LS, Sutton CE, Streubel G, Bracken AP, Mills KHG. Retinoic acid expression associates with enhanced IL-22 production in γδ T cells and innate lymphoid cells and attenuation of intestinal inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 2013;210:1117–1124. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nozaki Y, Yamagata T, Sugiyama M, Ikoma S, Kinoshita K, Funauchi M. Anti-inflammatory effect of all-trans-retinoic acid in inflammatory arthritis. Clin. Immunol. 2006;119:272–279. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Belloni PN, Garvin l, Mao CP, Bailey-Healy I, Leaffer D. Effects of all-trans-retinoic acid in promoting alveolar repair. Chest. 2000;117:235S–241S. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.5_suppl_1.235s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stolk J, Stockley R, Stoel B, Cooper BG, Pitulainen E, Seersholm N, Chapman KR, Burdon JG, Decramer M, Abboud RT, Mannes GP, E.F. W, Garrett JE, Barros-Tizon JC, Russi EW, Lomas DA, MacNee WA, Rames A. Randomised controlled trial for emphysema with a selective agonist of the γ-type retinoic acid receptor. Eur. Respir. J. 2012;40:306–312. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00161911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hatsell SJ, Idone V, Alessi Wolken DM, Huang L, Kim HJ, Wang LC, Wen X, Nannuru KC, Jimenez J, Xie L, das N, Makhoul G, Chernomorsky R, D'Ambrosio D, Corpina RA, Schoenherr CJ, Feeley K, Yu PB, Yancopoulos GD, Murphy AJ, Economides AN. ACVR1R206H receptor mutation causes fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva by imparting responsiveness to activin A. Science Trans. Med. 2015;7:303ra137. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac4358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Alemna-Muench GR, Soldevila G. When versatility matters: Activins/inhibins as key regulators of immunity. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2012;90:137–148. doi: 10.1038/icb.2011.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.