Abstract

The potential for epigenetic changes in host cells following microbial infection has been widely suggested, but few examples have been reported. We assessed genome-wide patterns of DNA methylation in human macrophage-like U937 cells following infection with Burkholderia pseudomallei, an intracellular bacterial pathogen and the causative agent of human melioidosis. Our analyses revealed significant changes in host cell DNA methylation, at multiple CpG sites in the host cell genome, following infection. Infection induced differentially methylated probes (iDMPs) showing the greatest changes in DNA methylation were found to be in the vicinity of genes involved in inflammatory responses, intracellular signalling, apoptosis and pathogen-induced signalling. A comparison of our data with reported methylome changes in cells infected with M. tuberculosis revealed commonality of differentially methylated genes, including genes involved in T cell responses (BCL11B, FOXO1, KIF13B, PAWR, SOX4, SYK), actin cytoskeleton organisation (ACTR3, CDC42BPA, DTNBP1, FERMT2, PRKCZ, RAC1), and cytokine production (FOXP1, IRF8, MR1). Overall our findings show that pathogenic-specific and pathogen-common changes in the methylome occur following infection.

Melioidosis is an infectious disease caused by the intracellular bacterial pathogen Burkholderia pseudomallei. A recent study has found that the incidence of this disease is likely to have been significantly underestimated1. B. pseudomallei adopts various strategies to survive and replicate within host cells2. Avoiding or resisting the antimicrobial activities in the phagosome of host cells2,3 allows escape into the cytosol, the induction of actin polymerization and cell to cell spreading4. The transcriptional response of humans or mice to B. pseudomallei infection reveals changes in the expression of multiple genes, including loci associated with the inflammatory and innate immune responses5,6,7. These changes might be driven actively by bacteria, or they may be the consequence of altered responses of host cells to the infection.

Recently, a role for epigenetic regulation of host cell function during bacterial infection has been suggested8,9. DNA methylation, occurring exclusively at cytosine residues in mammals, is one of the best understood epigenetic mechanisms, playing a key role in transcriptional regulation during development and being increasingly implicated in a range of non-infectious diseases10. Epigenetic processes can be dynamic: they are influenced upon exposure to a range of external environmental factors and stochastic events in the cell11.

Few studies have investigated epigenetic changes in response to infection but there are reports of altered patterns on methylation in cultured cells infected with Helicobacter pylori12,13, Mycobacterium tuberculosis14 or Leishmania donovani15 and evidence that in mice the gut flora influences methylation of the IL-4 gene in intestinal epithelial cells resulting in the down-regulation of TLR4 expression16. Some of these studies have focussed on selected genes12,16, others have profiled genome wide changes in the methylome13,14,15. These studies have revealed linkage between methylation events and the level of expression of associated gene(s).

In this study we determined genome-wide changes in DNA methylation in human macrophage-like U937 cells following infection by B. pseudomallei. We identify widespread changes in host cell DNA methylation following infection, and show that these are enriched in the vicinity of loci involved in inflammatory responses, intracellular signalling, apoptosis and pathogen-induced signalling. By comparing our data with the previously reported data we have identified genes, which show differential patterns of methylation in cells infected with different pathogens.

Results

Infection Model

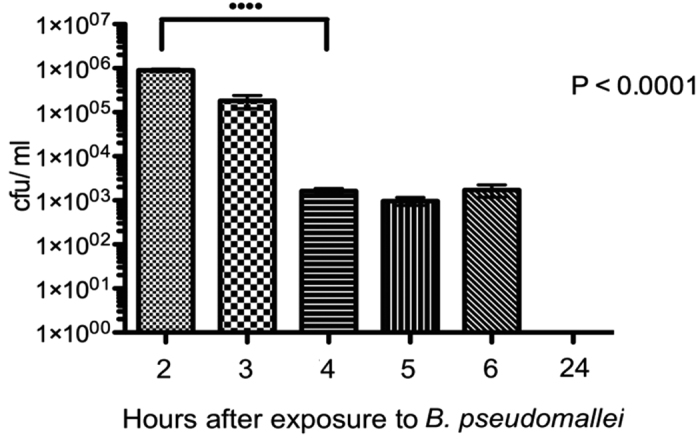

U937 cells can mature and differentiate to adopt the characteristics of mature human macrophages17. We established the pattern of infection of U937 cells, which had been activated with interferon gamma (IFN-γ), by B. pseudomallei K96243 expressing red fluorescent protein (RFP). At 2 hours (T2) post infection, 74% of the human cells were infected (Supplementary Fig. 1) and the number of intracellular bacteria was 106 CFU/ml (Fig. 1). After 4 (T4) or 6 hours (T6) post infection the number of intracellular bacteria had declined to 103 CFU/ml. No intracellular bacteria were recovered at 24 hours post infection (T24). We and others18 have found that the activation of macrophages with IFN-γ dramatically enhances the ability of the cells to control infection with B. pseudomallei and this explains the progressive reduction in the number of intracellular bacteria.

Figure 1. Bacterial loads at different time points in U937 cells infected with B. pseudomallei (MOI = 10).

Bacterial load was measured as colony forming units (CFU).

Multiple loci in U937 cells show reproducible changes in DNA methylation after B. pseudomallei infection

We infected U937 cells with B. pseudomallei and mapped changes in host cell DNA methylation at T2 and T4. DNA from the infected or uninfected (control) U937 cells was collected from two technical replicates and two experimental replicates at each time. We subsequently performed a second experiment following the same protocol but with additional sampling times included to provide samples at 1 hour (T1), 2 hours (T2), 3 hours (T3) and 4 hours (T4) post infection. The experimental design is shown in Supplementary Fig. 2.

DNA methylation was quantified using an Illumina 450K HumanMethylation array, with pre-processing, normalization and stringent quality control undertaken. In our first experiment we identified differentially-methylated positions (DMPs) between infected and uninfected cells at T2 or T4, allowing us to identify infection-induced DMPs (iDMPs).

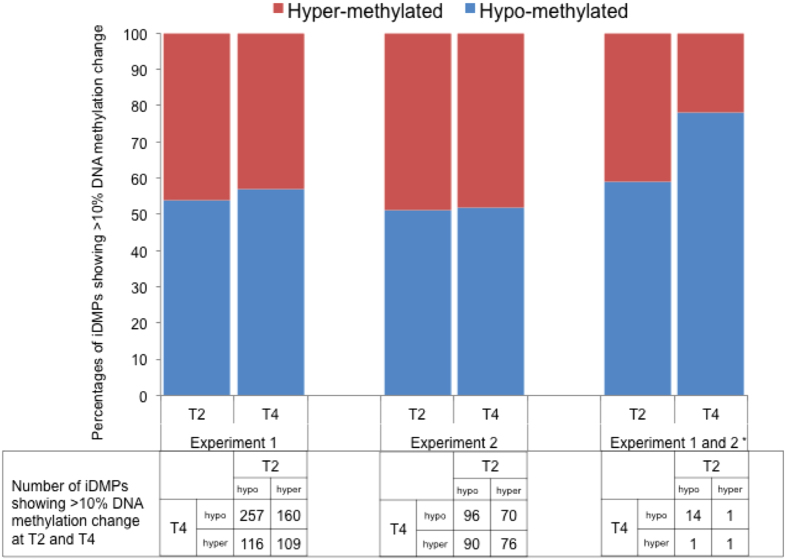

Reasoning that larger differences are potentially more biologically meaningful, our primary focus was on iDMPs characterized by >10% DNA methylation difference between groups19. We identified 10,279 iDMPs (54% hypo-methylated, 46% hyper-methylated) at T2 and 4850 iDMPs (57% hypo-methylated, 43% hyper-methylated) at T4, with 642 iDMPs differentially methylated at both T2 and T4 (Fig. 2). We next performed a second experiment to identify consistent changes and obtained a stringently-filtered dataset of 388 conserved iDMPs conserved between the two experiments and which were used for subsequent analysis. These DNA methylation changes were highly correlated across both experiments (T2: r = 0.83, p < 0.0001, Supplementary Fig. 3a; T4: r = 0.73, p < 0.0001, Supplementary Fig. 3b). 264 iDMPs were identical at T2, 141 iDMPs were conserved at T4 and 17 iDMPs conserved at both T2 and T4 (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 2. Quantification of Infection-induced iDMPs.

*iDMPs conserved between the two experiments.

The conserved iDMPs were not uniformly distributed across the genome (Supplementary Table 2). We found a highly-significant over- representation of infection-induced DNA methylation at probes located in the first exons of genes (compared to the frequency of positions in all probes on the Illumina 450K array analysed, relative enrichment (95% CI) = 3.34, P = 1.11 × 10−22).

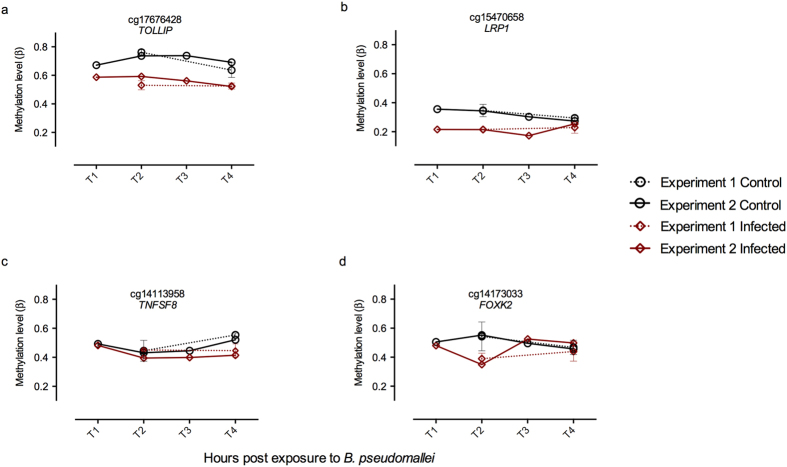

In addition to quantifying DNA methylation at T2 and T4 in experiment 1 and 2, we profiled samples collected at T1 and T3 in experiment 2 (Supplementary Fig. 2). Distinct patterns of DNA methylation across the four time points were observed (Table 1); 21 probes (5.41%) showed consistent changes in DNA methylation across all time points in both experiments (for example cg17676428 (Fig. 3a)), 23 (5.93%) showed large changes at the early time-points that diminished at the later time-points (for example cg15470658 (Fig. 3b)), 55 (14.18%) displayed a lag in response, with DNA methylation changes only occurring at the later time points after infection (for example cg14113958 (Fig. 3c)), 99 (25.52%) showed a transient (for example cg14173033 (Fig. 3d)), and 190 (48.97%) an oscillatory response. The losses of methylation were more prominent compared to gains in DNA methylation patterns, especially in iDMPs exhibiting a constant response.

Table 1. Number of iDMPs assigned to categories based on differential methylation patterns.

| Category | Number of probes | Hyper-methylated | Hypo-methylated |

|---|---|---|---|

| A: constant response | 21 | 3 | 18 |

| B: early response | 23 | 10 | 13 |

| C: late response | 55 | 11 | 44 |

| D: transient response | 99 | 42 | 57 |

| E: oscillatory response | 190 | NA | NA |

Signatures with differential methylation at all time points (1 hour (T1), 2 hours (T2), 3 hours (T3) and 4 hours (T4) post infection) were classified as, constant hyper- or constant hypo-methylated probes. Signatures with differential methylation at early time points (T1, T2, T3) and no change at the T4 time point were classified as early response probes. Signatures with no response at the T1 time point and with differential methylation at later time points were classified as late response probes. Signatures with no response at T1 and T4 and differential methylation at T2 or T3 were classified as transient responses. The remainder of the patterns were classified as oscillatory probes.

NA = not applicable.

Figure 3. Differential methylation patterns.

Each panel shows a representative gene, showing a particular temporal pattern as discussed in the main text and methods. The error bars represent the standard deviation of the methylation levels of the first experiment samples: (a) constant hypo-methylation; (b) early response hypo-methylation; (c) late response hypo-methylation; (d) transient response hypo-methylation.

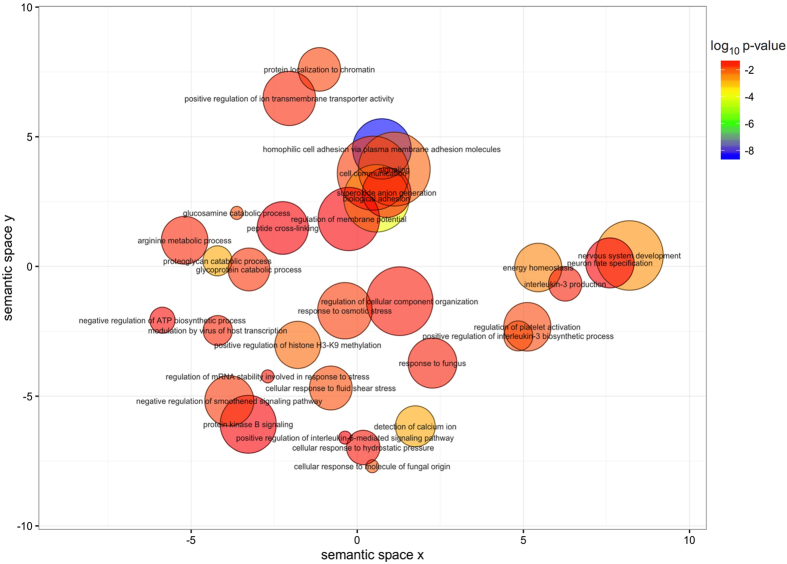

To explore the biological significance of the genes mapping to the set of iDMPs, we annotated their corresponding gene ontology (GO) term and searched for over-representation of categories using the package GOseq, which weights genes based on number of probes per gene. Enriched biological functions were summarised and visualised in Fig. 4 using semantic similarity, which provides a measure of functional similarity. Functionally similar GO terms appear closer in the plot.

Figure 4. Gene ontology terms enriched (p < 0.05) in genes mapping to conserved iDMPs.

The colour scale represents the p-values calculated using GOseq. The non-redundant gene ontology terms are clustered using REVIGO.

Comparison with publically available transcription data

We compared the iDMPs with transcriptomic data from a previous study of B. pseudomallei infection in humans which identified 2604 human genes, that were differentially expressed in patients with septicemic melioidosis6. Of these, 76 genes were annotated to the iDMPs we identified in our study. These included genes involved in immune system process (BCL11B, CDKN1C, GLMN, HLX, IL1R2, IRF8, MAEA, MEF2C, MR1, NBEAL2, PRKCH, PTGDR2, STK3, TNFSF8, TRIM27), response to stress (ADRB2, APBB1IP, DTNBP1, FBXO31, MARCH1, MSRA, PKD2, SCARB1, ZMYND11), and inflammatory response (CD44, HDAC4, HIF1A, IL18RAP, TOLLIP, IER3, NT5E).

Comparison with publically available DNA methylation changes during infection with other pathogens

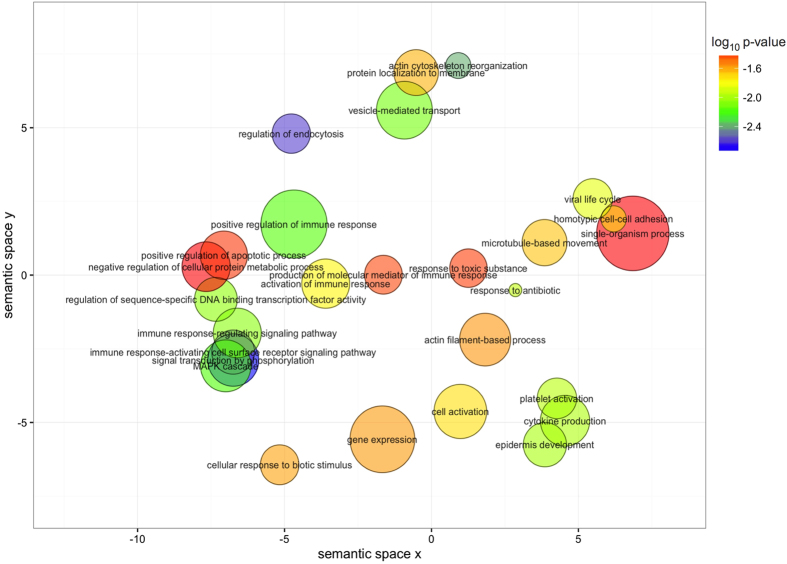

Innate immune cells, such as macrophages or dendritic cells, are recruited in response to pathogens to initiate defense mechanisms. While this study explores DNA methylation changes in macrophages, a recent study identified epigenetic regulation in human dendritic cells before and after in vitro infection (at 18 hours after infection) with Mycobacterium tuberculosis14. The proportions of iDMPs compared to the total number of sites probed were comparable to our study (0.000912 in our study; 0.000649 in the M. tuberculosis study). We did not identify any stringently-filtered iDMPs which were identical in cells infected with B. pseudomallei or with M. tuberculosis (Supplementary Fig. 4). However, when we considered the genes to which these iDMPs mapped we identified 121 genes (median distance of ~95 kb from the nearest transcription start site), which showed differential methylation in both studies (Supplementary Table 3). These included genes involved in T cell responses (BCL11B, FOXO1, KIF13B, PAWR, SOX4, SYK), actin cytoskeleton organization (ACTR3, CDC42BPA, DTNBP1, FERMT2, PRKCZ, RAC1), and cytokine production (FOXP1, IRF8, MR1) (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Gene ontology terms enriched (p < 0.05) in genes annotated to the iDMPs in B. pseudomallei and M. tuberculosis infections.

The colour scale represents the p-values calculated using GOseq. The non-redundant gene ontology terms are clustered using REVIGO.

Discussion

This study expands the limited knowledge on the role of epigenetics during infection by reporting temporal changes to the genome-wide methylome of human cells infected with a bacterial pathogen. For our study we have used human macrophages activated with interferon gamma, because we believe that this more accurately reflects the state of macrophages during sepsis caused by B. pseudomallei. We found that a range of genes associated with the immune response is differentially methylated in the host after infection with B. pseudomallei and these changes were replicated in a second experiment. These methylation events were associated with genes encoding cytokines, chemokines and their receptors (CCR4, IL1R2, IL18RAP, TNFSF15, TNFSF8, CCL28) and signalling pathways (CASP8AP2, TOLLIP, SYK, ZBP1, MAP4K4, MBIP). Immune system processes were also enriched in genes near iDMPs identified in this study and genes differentially expressed in patients’ blood infected with B. pseudomallei. Increased expression of the TOLLIP gene has previously been reported in humans infected with B. pseudomallei6. The precise role of TOLLIP in protective immunity is still being clarified. One function of the protein is to interact with IL1RI, TLR2 and TLR4 after lipopolysaccharide (LPS) activation, thereby modulating the NF-κB and JNK signaling pathways and consequently inflammatory responses to infection20. The role of B. pseudomallei LPS in virulence21 and the activation of TLR2 and TLR4 signalling during B. pseudomallei infection is well documented22,23,24. It is possible that the differential methylation of TOLLIP we have seen modulates the early immune response to B. pseudomallei LPS.

Another important feature of disease caused by B. pseudomallei is the ability of the pathogen to establish chronic or persistent infections. B. pseudomallei is an intracellular pathogen, and phagocytes are believed to be an important niche for growth and survival in the host25,26. The differential methylation of genes involved in memory T-cell responses, such as CD44, FOXO1 and FOXC1, might contribute to the inability of the host to mount responses capable of clearing infection. Other host defence systems involve interferon gamma and nitric oxide. Interferon gamma plays a key role in the control of B. pseudomallei infection27,28 and suppression of the host innate response to B. pseudomallei infection has previously been attributed to downregulation of the type I interferon gamma signalling pathway by the bacterial effector TssM29. Previously CD44high CD8 T-cells have been shown to be an important source of interferon gamma30 and we found evidence of differential methylation of CD44 in our study. We also found evidence of the differential methylation of a number of genes (IRF-8, IFNE and ZBP1), which are involved in the regulation of interferon gamma expression. Nitric oxide has potent antibacterial activity towards B. pseudomallei31,32. A DMP located upstream of the dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase 2 (DDAH2) gene that encodes an enzyme in the nitric oxide generation pathway is hypo-methylated at all time points. The differential methylation of the gene encoding the NOX4 NADPH oxidase that we have seen, might explain the activation of this enzyme in phagocytes infected by the bacterium33. Such observations provide new insights in the possible molecular mechanisms, which underpin suppression of the host response.

We also found differential methylation of genes associated with ubiquitination of proteins targeted for degradation, including the SPSB4 and WSB1 gene products, which are associated with substrate recognition and the NEDD4L and SIAH1 genes encoding ubiquitin ligases. The deamidation of the NEDD8L protein by a B. pseudomallei type III effector protein (CHBP) has previously been demonstrated, and this triggers apoptosis of host cells34. However, the modulation of host cell ubiquitination has also been associated with the suppression of host immunity35 and the downregulation of the NF-kappaB/type I interferon signalling pathways has been attributed to the ubiquitination of signalling molecules29. Our findings provide additional insight into the mechanisms that contribute to modulation of the ubiquitination pathway.

The most significantly enriched GO terms in the set of iDMPs were cell adhesion related (FDR corrected P < 0.05). B. pseudomallei is known to promote the polymerisation of host actin at one pole of the bacterium in an ARP2/3- dependent manner36. This enables motility of the bacteria and is essential for the uptake of bacteria into cells and the spread of bacteria within and between cells. Several iDMPs map to genes involved in actin binding or polymerisation. These include CDC42BPA, a component of the BLOC-1 complex, which can interact with WASH - a regulator of ARP2/337 and ACTR3, a major component of the ARP2/3 complex38. We also found differential methylation of one of the central regulators of actin polymerisation, the PAK1 p21-activated kinase39.

Our findings also suggest that there are some common targets for methylation in cells infected with pathogens. Most of the methylation changes in cells infected with M. tuberculosis or B. pseudomallei are losses rather than gains in methylation. A broadly similar trend has also been reported by Marr et al.15 who reported a larger proportion of hypo-methylated CpG sites in L. donovani infected macrophages. Overall it seems that there is a general trend toward demethylation of host cell DNA during infection. Our comparison of M. tuberculosis or B. pseudomallei induced changes in methylation patterns revealed that although a number of common genes were differentially methylated, there were no conserved iDMPs. However, since these studies used different cell types we cannot discount the possibility that there would be conserved iDMPs if the experimental conditions were identical.

We also found that the conserved iDMPs were significantly enriched in the first exon of genes, DNA methylation in this genomic compartment has been associated with transcriptional suppression40,41, suggesting that a large proportion of the infection associated DNA methylation changes observed could be altering gene transcription.

In summary, our work provides new insights into the extent to which infection with a bacterial pathogen results in differential methylation of host cell DNA. Our findings indicate that methylation of host DNA occurs on a much greater scale than previously suggested. None of the effector B. pseudomallei molecules identified to date have been shown to methylate host DNA. Whether differential methylation is a consequence of the direct interaction of bacterial methyltransferases with host cell DNA, or the consequence of modification of host cell methyltransferase activity awaits investigation.

Methods

Cell line and infection model

The human leukemic monocyte lymphoma cell line (U937, ATCC CRL-1593.2) was maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37 °C. U937 cells were differentiated to macrophage-like cells following exposure to 20 ng/ml (final concentration) of phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) for 48 hours at 37 °C and differentiation evidenced by increased adherence to tissue culture flasks. A total of eight flasks (four for infected cells and four for uninfected controls) were prepared.

Overnight cultures of B. pseudomallei K96243 were diluted in L-15 medium and added to differentiated U937 cells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10. Where indicated B. pseudomallei K96243 expressing red fluorescent protein (RFP) was used42. Uninfected controls in the remaining four flasks were overlaid with L15 medium only. The cells were then incubated at 37 °C for 2h to allow infection. The cells were washed 3 times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with fresh L15 medium containing 1 mg/ml kanamycin for 2 hr to kill extracellular bacteria. After 2 hrs the macrophage cells were held in fresh media containing 250 μg/ml kanamycin to supress the growth of extracellular bacteria. At appropriate time points the cells were washed 3 times in warm PBS and lysed with 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100. DNA was isolated using an AllPrep kit (Qiagen) and stored at −80 °C until required. DNA yield was measured using a Nanodrop instrument with measurements between 22.8–50.6 ng/ul.

Enumeration of adhesion and uptake of B. pseudomallei by U937 cells

At 1 hour (T1), 2 hours (T2), 4 hours (T4) and 24 hours (T24) post infection the cells were washed 3 times in warm PBS and lysed with 0.1% (vol/vol) triton X-100. Serial dilutions of the cell lysate were plated onto LB agar to determine the intracellular bacterial cell counts (Fig. 2).

Additionally at T2, cells were washed 3 times with PBS and overlaid with 200 μl paraformaldehyde 0.4%, ensuring any coverslips were fully immersed. Cells were than incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes. PFA was removed and coverslips were washed twice with PBS for 1 hour for each wash. Coverslips were removed and stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and cells visualized with epifluorescence. Eight fields of view were visualised and the number of uninfected or infected U937 cells counted. The mean number of cells associated with bacteria at T2 was calculated (Fig. 1).

A second experiment was designed to enable verification of the results of the first experiment. Similar procedures were followed as described above and DNA collected from uninfected and infected cells at 1 hour (T1), 2 hours (T2), 3 hours (T3) and 4 hours (T4) post infection.

DNA methylation analysis

The DNA methylation profile of the infected macrophage DNA was determined using the Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip (450K) (Illumina Inc.) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The 450 k BeadChip interrogates DNA methylation at >480,000CpG sites across the genome. Briefly, 500 ng of genomic DNA was sodium bisulfite converted using the EZ-96 DNA Methylation kit (Zymo research, CA, USA) using the manufacturer’s instructions. Post-hybridisation allelic-specific single-base extension of the probes incorporates a fluorescent label enabling detection. Replicates were processed together on the same array to reduce batch effects. The data was extracted and the initial analysis was performed using GenomeStudio (2010.3) methylation module (1.8.5). For further details please see Pidsley et al.43.

Data Analysis

For each CpG site a beta value was generated by the relative intensity of the green fluorescent signal (methylated (M)) to the red and green signal combined (M/M+U+100). Quality control checks and quantile normalisation were implemented using WateRmelon43. Samples with more than 1% of sites with a detection p-value greater than 0.05 were removed as were probes with 1% of samples with a detection p-value greater than 0.05. Probes were removed if they had a bead count less than 3 in 1% of samples. Cross-hybridizing probes were removed44, leaving 425496 probes for analysis. DMPs between infected and control cells were identified using Δβ cut-off of 0.1. iDMPs identified at T2 and T4 in the first experiment, were compared to the corresponding probes at the same time point in the second experiment. Probes exhibiting a Δβ change in the same direction of =>0.1 were taken for further analysis. Correlation of Δβ values between the two experiments was measured using Pearson Correlation Coefficient. This set of replicated iDMPs were tested for enrichment of genomic regions using a two-tailed Fisher’s exact test, compared to the frequency of all probes on the Illumina 450 K array. iDMPs with consistent up or down-methylation throughout T1, T2, T3 and T4 were determined. The temporal methylation patterns were assigned to categories based on the change in score at successive time points. As many of the differential methylation patterns found in disease or environmental factors are characterized by smaller changes, in the range of 5%15, this criterion was selected to identify temporal patterns of differential methylation. Signatures with more than 5% differential methylation at all time points were classified as, constant hyper- (+5%) or constant hypo-methylated (−5%) probes. Signatures with more than 5% differential methylation at early time points (T1, T2, T3) and no change at the T4 time point were classified as early response probes. Signatures with no response at the T1 time point and with more than 5% differential methylation at later time points were classified as late response probes. Signatures with no response at T1 and T4 and more than 5% differential methylation at T2 or T3 were classified as transient responses. The remainder of the patterns were classified as oscillatory probes.

Candidate genes were assigned to the probes using the GREAT software45, genes are allotted to genomic regions taking into account the functional significance of cis-regulatory regions. Gene ontology term enrichment analysis was performed using the Bioconductor package GOseq46. Enriched gene ontology terms are selected based on the criteria of having p-value < 0.05. Redundant gene ontology terms were removed and the non-redundant gene ontology terms were clustered using semantic similarity measures (the simRel score) using REVIGO47.

Additional Information

Accession codes: All of the DNA methylation data are available at the GEO database (accession number GSE83379).

How to cite this article: Cizmeci, D. et al. Mapping epigenetic changes to the host cell genome induced by Burkholderia pseudomallei reveals pathogen-specific and pathogen-generic signatures of infection. Sci. Rep. 6, 30861; doi: 10.1038/srep30861 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the UK Defence Science and Technology Laboratory, award DSTLX-1000060221 to R.W.T., O.S.S. and O.E.A.

Footnotes

Author Contributions D.C., O.L.C., O.S.S., J.M. and R.W.T. designed the study. O.L.C. and S.W. established the infection model. E.L.D. conducted the DNA methylation experiments. D.C. and E.L.D. analysed the DNA methylation data. D.C., E.L.D., O.L.C., O.E.A., J.L.P., O.S.S., J.M. and R.W.T. analysed the results. D.C. and R.W.T. wrote the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the manuscript.

References

- Limmathurotsakul D. et al. Predicted global distribution of Burkholderia pseudomallei and burden of melioidosis. Nat. Microbiol. 1, 15008 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiersinga W. J., van der Poll T., White N. J., Day N. P. & Peacock S. J. Melioidosis: insights into the pathogenicity of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4, 272–282 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galyov E. E., Brett P. J. & DeShazer D. Molecular insights into Burkholderia pseudomallei and Burkholderia mallei pathogenesis. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 64, 495–517 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens M. et al. Identification of a bacterial factor required for actin‐based motility of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Mol. Microbiol. 56, 40–53 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin C.-Y., Monack D. M. & Nathan S. Genome wide transcriptome profiling of a murine acute melioidosis model reveals new insights into how Burkholderia pseudomallei overcomes host innate immunity. BMC Genomics 11, 672 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankla R. et al. Genomic transcriptional profiling identifies a candidate blood biomarker signature for the diagnosis of septicemic melioidosis. Genome Biol. 10, R127 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joost Wiersinga W., Dessing M. C. & van der Poll T. Gene-expression profiles in murine melioidosis. Microbes Infect. 10, 868–877 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K. Influence of bacteria on epigenetic gene control. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 71, 1045–1054 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierne H., Hamon M. & Cossart P. Epigenetics and bacterial infections. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine 2, a010272 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M. M. & Bird A. DNA methylation landscapes: provocative insights from epigenomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 9, 465–476 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ushijima T. et al. Fidelity of the methylation pattern and its variation in the genome. Genome Res. 13, 868–874 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang F. Y. et al. Helicobacter pylori induces promoter methylation of E-cadherin via interleukin-1beta activation of nitric oxide production in gastric cancer cells. Cancer 118, 4969–4980 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa T. et al. Inflammatory processes triggered by Helicobacter pylori infection cause aberrant DNA methylation in gastric epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 70, 1430–1440 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacis A. et al. Bacterial infection remodels the DNA methylation landscape of human dendritic cells. Genome Res. 25, 1801–1811 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marr A. K. et al. Leishmania donovani Infection Causes Distinct Epigenetic DNA Methylation Changes in Host Macrophages. PLoS Pathog. 10, e1004419 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K. et al. Epigenetic control of the host gene by commensal bacteria in large intestinal epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 35755–35762 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann M. H. Recombinant human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor triggers interleukin-10 expression in the monocytic cell line U937. Mol. Immunol. 35, 479–485 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depke M. et al. Bone marrow-derived macrophages from BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice fundamentally differ in their respiratory chain complex proteins, lysosomal enzymes and components of antioxidant stress systems. J. Proteomics 103, 72–86 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mill J. & Heijmans B. T. From promises to practical strategies in epigenetic epidemiology. Nature reviews. Genetics 14, 585–594 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capelluto D. G. S. Tollip: A multitasking protein in innate immunity and protein trafficking. Microbes Infect. 14, 140–147 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeShazer D., Brett P. J. & Woods D. E. The type II O-antigenic polysaccharide moiety of Burkholderia pseudomallei lipopolysaccharide is required for serum resistance and virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 30, 1081–1100 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West T. E. et al. Toll-like receptor 4 region genetic variants are associated with susceptibility to melioidosis. Genes Immun. 13, 38–46 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West T. E., Ernst R. K., Jansson-Hutson M. J. & Skerrett S. J. Activation of Toll-like receptors by Burkholderia pseudomallei. BMC Immunol. 9, 46 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiersinga W. J. et al. Toll-like receptor 2 impairs host defense in gram-negative sepsis caused by Burkholderia pseudomallei (Melioidosis). PLoS Med. 4, 1268–1280 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limmathurotsakul D. & Peacock S. J. Melioidosis: A clinical overview. British Medical Bulletin 99, 125–139 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiersinga W. J., Currie B. J. & Peacock S. J. Melioidosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 367, 1035–1044 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santanirand P., Harley V. S., Dance D. A. B., Drasar B. S. & Bancroft G. J. Obligatory role of gamma interferon for host survival in a murine model of infection with Burkholderia pseudomallei. Infect. Immun. 67, 3593–3600 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauw F. N. et al. Soluble granzymes are released during human endotoxemia and in patients with severe infection due to Gram-negative bacteria. J. Infect. Dis. 182, 206–213 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan K. S. et al. Suppression of host innate immune response by Burkholderia pseudomallei through the virulence factor TssM. J. Immunol. 184, 5160–5171 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lertmemongkolchai G., Cai G., Christopher A., Bancroft G. J. & Hunter C. A. Bystander Activation of CD8 + T Cells Contributes to the Rapid Production of IFN- γ in Response to Bacterial Pathogens. J. Immunol. 166, 1097–1105 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Carson J., Laughlin J. R., Stewart A. L., Voskuil M. I. & Vázquez-Torres A. Nitric oxide-dependent killing of aerobic, anaerobic and persistent Burkholderia pseudomallei. Nitric Oxide - Biol. Chem. 27, 25–31 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitbach K., Wongprompitak P. & Steinmetz I. Distinct roles for nitric oxide in resistant C57BL/6 and susceptible BALB/c mice to control Burkholderia pseudomallei infection. BMC Immunol. 12, 20 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikraiphat C., Pudla M., Baral P., Kitthawee S. & Utaisincharoen P. Activation of NADPH oxidase is essential, but not sufficient, in controlling intracellular multiplication of Burkholderia pseudomallei in primary human monocytes. Pathog. Dis. 71, 69–72 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Q. et al. Structural mechanism of ubiquitin and NEDD8 deamidation catalyzed by bacterial effectors that induce macrophage-specific apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 20395–20400 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. H. et al. Burkholderia pseudomallei suppresses Caenorhabditis elegans immunity by specific degradation of a GATA transcription factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110, 15067–15072 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens J. M. et al. Actin-binding proteins from Burkholderia mallei and Burkholderia thailandensis can functionally compensate for the actin-based motility defect of a Burkholderia pseudomallei bimA mutant. J. Bacteriol. 187, 7857–7862 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryder P. V. et al. The WASH complex, an endosomal Arp2/3 activator, interacts with the Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome complex BLOC-1 and its cargo phosphatidylinositol-4-kinase type IIα. Mol. Biol. Cell 24, 2269–2284 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May R. C. The Arp2/3 complex: a central regulator of the actin cytoskeleton. Cell Mol Life Sci 58, 1607–1626 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sells M. a et al. Human p21-activated kinase (Pak1) regulates actin organization in mammalian cells. Curr. Biol. 7, 202–210 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenet F. et al. DNA methylation of the first exon is tightly linked to transcriptional silencing. PLoS One 6, e14524 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang T.-J., Chen F.-C. & Chen Y.-Z. Position-dependent correlations between DNA methylation and the evolutionary rates of mammalian coding exons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109, 15841–15846 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wand M. E., Müller C. M., Titball R. W. & Michell S. L. Macrophage and Galleria mellonella infection models reflect the virulence of naturally occurring isolates of B. pseudomallei, B. thailandensis and B. oklahomensis. BMC Microbiol. 11, 11 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pidsley R. et al. A data-driven approach to preprocessing Illumina 450K methylation array data. BMC Genomics 14, 293 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price M. E. et al. Additional annotation enhances potential for biologically-relevant analysis of the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip array. Epigenetics Chromatin 6, 4 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean C. Y. et al. GREAT improves functional interpretation of cis-regulatory regions. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 495–501 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young M. D., Wakefield M. J., Smyth G. K. & Oshlack A. Gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq: accounting for selection bias. Genome Biol. 11, R14 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supek F., Bosnjak M., Skunca N. & Smuc T. Revigo summarizes and visualizes long lists of gene ontology terms. PLoS One 6, e21800 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.