Abstract

Targeted human cytolytic fusion proteins (hCFPs) represent a new generation of immunotoxins (ITs) for the specific targeting and elimination of malignant cell populations. Unlike conventional ITs, hCFPs comprise a human/humanized target cell‐specific binding moiety (e.g., an antibody or a fragment thereof) fused to a human proapoptotic protein as the cytotoxic domain (effector domain). Therefore, hCFPs are humanized ITs expected to have low immunogenicity. This reduces side effects and allows long‐term application. The human ribonuclease angiogenin (Ang) has been shown to be a promising effector domain candidate. However, the application of Ang‐based hCFPs is largely hampered by the intracellular placental ribonuclease inhibitor (RNH1). It rapidly binds and inactivates Ang. Mutations altering Ang's affinity for RNH1 modulate the cytotoxicity of Ang‐based hCFPs. Here we perform in total 2.7 µs replica‐exchange molecular dynamics simulations to investigate some of these mutations—G85R/G86R (GGRRmut), Q117G (QGmut), and G85R/G86R/Q117G (GGRR/QGmut). GGRRmut turns out to perturb greatly the overall Ang‐RNH1 interactions, whereas QGmut optimizes them. Combining QGmut with GGRRmut compensates the effects of the latter. Our results explain the in vitro finding that, while Ang GGRRmut‐based hCFPs resist RNH1 inhibition remarkably, Ang WT‐ and Ang QGmut‐based ones are similarly sensitive to RNH1 inhibition, whereas Ang GGRR/QGmut‐based ones are only slightly resistant. This work may help design novel Ang mutants with reduced affinity for RNH1 and improved cytotoxicity.

Keywords: targeted therapy, cytolytic fusion protein, apoptosis, angiogenin, ribonuclease inhibitor, mutagenesis, replica exchange, molecular dynamics

Introduction

Immunotoxins (ITs) are recombinant fusion proteins consisting of a toxin genetically fused to a target cell‐specific binding moiety. The latter is usually an antibody or a derivative thereof.1 The toxin moiety is typically derived from plants or bacteria, e.g., ricin A from Ricinus communis or Pseudomonas aeruginosa exotoxin A (ETA). The binding moieties are originated from mice, human or chimeric. Compared to the traditional cancer chemotherapy, ITs have the advantage that they are exceptionally specific for a distinctive target cell population. However, their non‐human components are potentially immunogenic and can lead to several side effects upon repeated application.2 In addition, host development of neutralizing antibodies against these components promotes rapid clearance of the ITs from blood circulation and limits long‐term treatment.3, 4, 5

To circumvent these problems, a new generation of ITs called targeted human cytolytic fusion proteins (hCFPs) is being developed. In these fusion proteins, humanized or fully human antibody fragments replace the murine counterparts and human proapoptotic proteins such as granzymes, ribonucleases (RNases) or microtubule‐associated proteins (MAPs) substitute the bacterial/plant toxins to be the effector domain. Human CFPs are expected to be better tolerated than conventional ITs upon application.6

In this context, the human RNase angiogenin (Ang) is a promising candidate for the effector domain. Ang is a 14‐kDa stress‐activated enzyme with both angiogenic and ribonucleolytic activities. On the one hand, it enhances overall biogenesis, supports the synthesis of proteins necessary for blood vessel growth and promotes primary tumor development and metastasis.7 On the other hand, it induces translational repression by cleaving the 3'‐CAA terminus, the anticodon loop of tRNA as well as 5S, 18S and 28S rRNA.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 Using its ribonucleolytic activity, Ang has been successfully implemented as the effector domain in hCFPs.16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 Unfortunately, therapeutic applications of Ang‐based hCFPs are currently challenged by the ubiquitously expressed intracellular placental ribonuclease inhibitor RNH1.22 RNH1 has an extraordinary affinity for Ang in the femtomolar range23 and it is present in very high content (representing ≥0.01% of total intracellular proteins across almost all human cell types).22, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 RNH1 binding completely abolishes Ang's activities.23, 28, 29, 30 Hence, the efficacy of Ang‐based hCFPs would be greatly improved by evading RNH1, which undesirably mitigates most of the hCFPs delivered into the target cells.

Some of us have shown that a dramatic decrease of Ang‐RNH1 affinity by site‐directed point mutations could significantly enhance the cytotoxicity of Ang‐based hCFPs.31 We generated hCFPs composed of Ang variants genetically fused to the anti‐CD64 H22 single‐chain variable fragment. The variants are: Ang G85R/G86R mutant (hereafter Ang GGRRmut), Ang Q117G mutant (Ang QGmut) and Ang G85R/G86R/Q117G mutant (Ang GGRR/QGmut). Ang GGRRmut is known to have 106‐fold lower binding affinity for RNH1 than Ang wild type (WT),32 whereas Ang QGmut shows higher ribonucleolytic activity than Ang WT.33 To assess the inhibition of these hCFPs (denoted H22‐Ang variants) by the ribonuclease inhibitor in vitro, we measured the biological activity of these hCFPs in HL‐60 cells and human M1 macrophages (hM1Φ) (Supporting Information).34 In the in vitro experiments performed in the absence of ribonuclease inhibitor, we found more potent ribonuleolytic activity of both H22‐Ang QGmut and H22‐Ang GGRR/QGmut in comparison to H22‐Ang WT, whereas H22‐Ang GGRRmut exhibited no significant difference. In the presence of ribonuclease inhibitor, however, H22‐Ang GGRRmut showed the strongest ribonucleolytic activity, while the other hCFPs variants were significantly inhibited resulting in comparably lower efficiency (Supporting Information Fig. S1). Consistently, in both HL‐60 cells and hM1Φ, H22‐Ang GGRRmut showed remarkably lower EC50 values than H22‐Ang WT (Supporting Information Fig. S2).34 However, since H22‐Ang QGmut and H22‐Ang GGRR/QGmut were sensitive to the ribonuclease inhibitor, they were only slightly more cytotoxic than H22‐Ang WT (Supporting Information Fig. S2).31, 34

Providing the molecular basis of the mutational effects on Ang's affinity for RNH1 may help design new Ang variants with improved cytotoxicity. Here we predict the structure and the conformational flexibility of Ang WT, Ang GGRRmut, Ang QGmut and Ang GGRR/QGmut, each in complex with RNH1 in aqueous solution, by replica‐exchange molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. The RNH1‐Ang WT complex in aqueous solution turns out to preserve the X‐ray structure in the solid state.35 RNH1‐Ang GGRRmut experiences the largest fluctuations and a number of intermolecular interactions are disrupted. The results are consistent with the remarkable decrease in affinity induced by the GGRR mutation.32 RNH1‐Ang QGmut shows the smallest fluctuations and forms the most extensive intermolecular interactions among the four variants. This is consistent with the in vitro finding that the Ang QGmut‐based hCFP is sensitive towards RNH1. We find that combining QGmut with GGRRmut enables Ang to recover the interactions with RNH1 that are otherwise disrupted by GGRRmut. Also these findings are fully consistent with in vitro data, which indicate that Ang GGRR/QGmut has much higher affinity for RNH1 than Ang GGRRmut.31, 34

Results and Discussion

RNH1‐Ang WT in aqueous solution

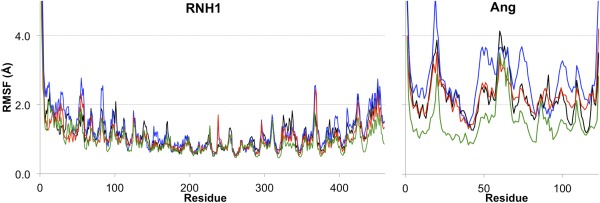

The RNH1‐Ang WT complex is similar to the X‐ray structure, as shown by a superimposition of the latter with the most populated conformer cluster in our simulations (Fig. 1). Ang binds in the center of the RNH1 ‘horseshoe’‐shaped structure, forming extensive contacts with the C‐terminal fraction of RNH1. Ang helix 2 and residues 85‐59 interact with the N‐terminal fraction of RNH1 and the middle of the horseshoe inner surface, respectively. The Cα's RMSD of RNH1 and Ang are 2.0 ± 0.3 Å and 3.0 ± 0.6 Å, respectively (Supporting Information Fig. S3). Not unexpectedly, the C‐terminus of RNH1 (Residues 1–5) is more flexible in solution than in the solid state, where it forms crystal‐packing contacts.35 The Cα's RMSF values (Fig. 2) correlate fairly well with the Debye–Waller factors of the X‐ray structure. In particular, loops and the N‐ and C‐termini of Ang feature relatively high RSMF and Debye–Waller values (Fig. 1). The RNH1 backbone is more rigid than that of Ang (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Representative structure of the RNH1‐Ang WT trajectory (green) superimposed on the X‐ray structure. The red to blue color indicates low to high Debye–Waller factors in the X‐ray structure.35 The representative structure is obtained by cluster analysis of the trajectory using 2.5‐Å cutoff on Ang Cα's RMSD. It corresponds to the middle structure of the most populated cluster (including 54% of the frames).

Figure 2.

Cα's RMSF values of (A) RNH1 and (B) the Ang variants, in RNH1‐Ang WT (black), RNH1‐Ang GGRRmut (blue), RNH‐Ang QGmut (green), and RNH1‐Ang GGRR/QGmut (red).

The intermolecular and intramolecular interactions formed by residues AngG85, AngG86, and AngQ117 are analyzed in detail here because these residues are mutated in this study. In solution, AngG85 and AngG86 interact largely with water molecules. This could be the case also for the X‐ray structure in which likely not all the water molecules are resolved. AngG86 here also forms hydrogen bond (H‐bond) with RNH1Q346 side chain and, to a lesser extent, with RNH1S289 side chain [Supporting Information Table S2, Fig. 3(A)]. In the X‐ray structure AngG86 appears to interact only with RNH1S289 side chain. In solution, AngQ117 backbone is largely solvent‐exposed. It also forms H‐bonds with AngF120 and AngR121 backbones (Supporting Information Table S2). In the X‐ray structure, it forms a water‐bridged H‐bond with RNH1D435 backbone and direct H‐bonds with AngF120 and AngR121 backbones. AngQ117 side chain forms H‐bond with AngT44 backbone both in solution [Supporting Information Table S2, Fig. 4(A)] and in the X‐ray structure. In solution, it forms H‐bonds also with RNH1D435 side chain and AngI42 backbone. In the X‐ray structure, water molecules interacting with the two proteins are not all resolved, thus the interactions described here are putative.

Figure 3.

Representative structures (from a cluster analysis) of (A) RNH1‐Ang WT, (B) RNH1‐Ang GGRRmut, (C) RNH1‐Ang QGmut, and (D) RNH1‐Ang GGRR/QGmut around Ang Residues 85–89. RNH1 and Ang backbones are shown in gray and yellow ribbons, respectively. Residues discussed in the main text are shown in sticks. Magenta dashed lines indicate H‐bonds. Water molecules are not shown for clarity.

Figure 4.

Salt bridge and H‐bond contacts (magenta dashed lines) around the C‐terminus of Ang. The RNH1 backbone is shown in gray ribbon. The Ang backbone is shown in cartoon and colored by secondary structure. Positively and negatively charged residues that form salt bridges are labeled in blue and red, respectively. Main‐chain and side‐chain atoms are shown in sticks and balls, respectively. (A) RNH1‐Ang WT preserves a salt‐bridge/H‐bond network throughout the simulation. (B) In RNH1‐Ang GGRRmut, AngQ117 side chain swings between the original position (such as in RNH1‐Ang WT) and a solvent‐exposed one (shown here) where it forms an H‐bond with RNH1N406. (C) RNH1‐Ang QGmut maintains the same C‐terminal conformation and intra‐/intermolecular interactions as those in RNH1‐Ang WT, except for the H‐bonds involving the mutated Ang residue 117. (D) Ang GGRR/QGmut C‐terminus adjusts its position with respect to RNH1 and forms stable salt bridges with the latter via AngR121 and AngR122.

RNH1‐Ang GGRRmut in aqueous solution

The overall RNH1 structure is similar to the X‐ray structure (Cα's RMSD 2.1 ± 0.5 Å, Supporting Information Fig. S3). Its conformational flexibility is similar to that in RNH1‐Ang WT [Fig. 2(A)]. However, Ang GGRRmut shows larger Cα's RMSD (3.4 ± 0.8 Å, Supporting Information Fig. S3) and Cα's RMSF (Fig. 2B) than Ang WT. Not unexpectedly, conformational rearrangements occur around the Ang mutation site (residues 85‐89). Moreover, they also occur in distant regions from the mutation site, namely around Ang C‐terminus (residues 117–123) and helix 2 (residues 23–33). This indicates mutation‐induced long‐range effects on the overall complex structure (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Superimposition of representative structures of RNH1‐Ang GGRRmut (blue) and RNH1‐Ang WT (yellow) obtained by cluster analysis on the trajectories using 2.5 Å cutoff on Ang Cα's RMSD. The most populated cluster of RNH1‐Ang GGRRmut contains 39% of the frames. The mutation sites are indicated by red dots.

Ang GGRRmut residues 85‐89 increase their bend conformation by 33% relative to that in Ang WT (Table 1). The backbone dihedrals of the mutated residues differ from those of Ang WT (Supporting Information Fig. S4). AngR85 and AngR86 backbone units are largely solvent exposed. In contrast to RNH1‐Ang WT, AngG86 forms a H‐bond with RNH1Q346 side chain (Fig. 3). AngR85 side chain forms salt bridges with RNH1E149 and, to a lesser extent, with RNH1E206, while AngR86 side chain forms salt bridge with RNH1E206 and, to a lesser extent, with RNH1E264 [Fig. 3(B), Supporting Information Table S3]. The hydrophobic parts of R85 and R86 side chains form van der Waals contacts with the surrounding residues. While AngS87 and AngW89 maintain similar side‐chain conformations to those in RNH1‐Ang WT, AngP88 interacts more weakly with RNH1W375 than in RNH1‐Ang WT (Supporting Information Table S4).

Table 1.

Frequency of secondary structures (in %[Link]) in selected regions that differ among the four Ang variants

| Region (residues) | Variant | α‐Helix | 310‐Helix | β‐Sheet | β‐Turn | Bend | Coil |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Helix 3 (50–58) |

Ang WT | 81 (16) | |||||

| Ang GGRRmut | 78 (17) | ||||||

| Ang QGmut | 74 (16) | 11 (11) | |||||

| Ang GGRR/QGmut | 92 (14) | ||||||

|

β‐Strand 3 (69–72) |

Ang WT | 85 (15) | 15 (15) | ||||

| Ang GGRRmut | 85 (14) | 13 (14) | |||||

| Ang QGmut | 87 (13) | 13 (13) | |||||

| Ang GGRR/QGmut | 90 (14) | ||||||

| Residues 85–89 | Ang WT | 61 (20) | 35 (18) | ||||

| Ang GGRRmut | 81 (15) | 19 (15) | |||||

| Ang QGmut | 67 (15) | 32 (14) | |||||

| Ang GGRR/QGmut | 30 (15) | 70 (15) | |||||

| C‐Terminus (117–121) | Ang WT | 53 (40) | 17 (30) | 20 (24) | |||

| Ang GGRRmut | 37 (40) | 32 (38) | 14 (21) | ||||

| Ang QGmut | 76 (18) | 11 (13) | |||||

| Ang GGRR/QGmut | 30 (40) | 37 (38) | 28 (28) |

Those with frequency <10% are not shown.

aStandard deviation is indicated in parenthesis.

The C‐terminus of Ang GGRRmut shows higher 310‐helix content than that in Ang WT and lower α‐helix content (Table 1). The C‐terminus partially dissociates from RNH1 and the salt‐bridge/H‐bond network present in RNH1‐Ang WT is largely disrupted (Fig. 4, Supporting Information Tables S2 and S3). The rearrangements appear to destabilize the AngQ117 side chain, which swings between the original position and a solvent‐exposed one [Fig. 4(B)].

Around Ang helix 2, intermolecular salt bridges and H‐bonds are weaker than in RNH1‐Ang WT, as indicated by their lifetime (Supporting Information Tables S2 and S3).

These results might be consistent with the fact that in vitro GGRRmut remarkably reduces Ang's binding affinity for RNH1.32

RNH1‐Ang QGmut in aqueous solution

Among the four variants studied here, RNH1‐Ang QGmut shows the smallest Cα's RMSF (Fig. 2), and the smallest Cα's RMSD relative to the X‐ray structure (1.3 ± 0.2 Å and 1.9 ± 0.4 Å for RNH1 and Ang QGmut, respectively, Supporting Information Fig. S3). The overall conformation appears nearly identical to that of RNH1‐Ang WT (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Superimposition of representative structures of RNH1‐Ang QGmut (green) and RNH1‐Ang WT (yellow). Cluster analysis on the RNH1‐Ang QGmut trajectories used 1.1 Å cutoff on Ang Cα's RMSD. The most populated cluster contains 68% of the frames. The mutation site is indicated by a red dot.

Around Ang residues 85‐89, the RNH1‐Ang QGmut complex displays a very similar conformation and intermolecular interactions to those in RNH1‐Ang WT (Fig. 3). The AngP88‐RNH1W375 hydrophobic contacts are enhanced when compared to RNH1‐Ang WT (Supporting Information Table S4).

At Ang C‐terminus, the mutation eliminates AngQ117 side chain and its H‐bonds with surrounding residues (Fig. 4). Local intra‐ and intermolecular salt‐bridge and H‐bond contacts are slightly altered (Supporting Information Tables S2 and S3). In particular, AngR121 forms more persistent salt bridge and H‐bond interactions with AngD41 and AngG117, respectively, which contribute to reinforce the α‐helix structure in Ang C‐terminus (Table 1).

Around Ang helix 2, intermolecular salt bridges are remarkably strengthened, despite the loss of the weak AngS28‐RNH1D36 H‐bond (Supporting Information Tables S2 and S3). This corresponds to the small RMSF around helix 2.

Crystallographic studies36 have reported that Ang QGmut shows no structural changes from Ang WT other than the loss of residue 117 side chain. Here we find that in complex with RNH1, Ang QGmut has overall more extensive intra‐ and intermolecular interactions than the WT form, suggesting higher affinity for RNH1. This is consistent with the mutant's sensitivity towards RNH1 in vitro.

RNH1‐Ang GGRR/QGmut in aqueous solution

RNH1 features similar overall strucrural determinants to those of the X‐ray one (Cα's RMSD 1.8 ± 0.2 Å, Supporting Information Fig. S3). Its conformational flexibility is similar to that in RNH1‐Ang WT [Fig. 2(A)]. In particular, Ang GGRR/QGmut shows large Cα's RMSD (4.2 ± 0.7 Å, Supporting Information Fig. S3) and similar Cα's RMSF [Fig. 2(B)] to Ang WT. This indicates that the mutant deviates notably from the initial position (Fig. 7) without increasing its conformational flexibility. Conformational rearrangements occur not only around the mutation sites (residues 85‐89 and the C‐terminus) but also at helix 2.

Figure 7.

Representative structure of RNH1‐Ang GGRR/QGmut (red) from the most populated cluster (including 43% of the frames) superimposed on that of RNH1‐Ang WT (yellow). The mutation sites are indicated by blue dots.

Around Ang residues 85‐89, AngR85 and AngR86 backbone dihedrals are similar to those of Ang GGRRmut (Supporting Information Fig. S4). However, we find different features from those in Ang GGRRmut. Residues 85‐89 bend conformation decreases by 51% relative to that in Ang WT, unlikely in Ang GGRRmut (Table 1). AngR85 side chain forms weaker salt bridges with RNH1E149 and RNH1E206 than those in Ang GGRRmut (Supporting Information Table S3). AngR86 backbone forms H‐bond with RNH1Q346, similar to that in Ang WT (Fig. 3). AngR86 side chain forms salt bridges mainly with RNH1E264 and, to a lesser extent, with RNH1E206 (Supporting Information Table S3). AngP88 forms more extensive interactions with RNH1W375 than in Ang WT, in contrast to that in Ang GGRRmut (Supporting Information Table S4).

Around Ang C‐terminus, Residues 117–121 show even less α‐helix and more 310‐helix than those in RNH1‐Ang GGRRmut (Table 1). QGmut allows Ang C‐terminus to adapt to the impact by GGRRmut and form new salt bridges [Fig. 4(C)]. The backbone of Ang GGRR/QGmut Residues 114–119 are close to RNH1, similar to that in Ang WT (Fig. 7). This contrasts with what has been observed in Ang GGRRmut (see the section above). These residues also enhance the adjacent intermolecular interactions with RNH1Y437 (Supporting Information Tables S2 and S3), which stabilizes Ang β‐strand 3 and helix 3 in a long range. Indeed, the latter two regions show longer lifetime than in Ang WT and in Ang GGRRmut (Table 1).

Around Ang helix 2, the intermolecular salt bridges and H‐bonds are more stable than those in RNH1‐Ang GGRRmut and in RNH1‐Ang WT (Supporting Information Tables S2 and S3). In particular, the AngR31‐RNH1D35 salt bridge is very stable (lifetime 100%).

Materials and Methods

Our initial structural models were built based on the X‐ray structure of the RNH1‐Ang complex (PDB entry 1A4Y).35 Using Modeller 9.9,38 we added seven residues of the linkers to Ang (ESR‐ at the C‐terminus and ‐AEHE at the N‐terminus) in the initial models to mimic the linkers present in the in vitro assays of the hCFPs mentioned in this work.31, 34

The Ang mutations were introduced into the structure using the SWISS PDB Viewer.39 The NQ‐Flipper40 and H++41 webservers were used to assign the asparagine and glutamine side‐chain rotamers and the histidine side‐chain protonation state, respectively. Each model was then solvated in a periodic cubic box ensuring a 20‐Å buffer zone around the protein. The box size was set sufficiently large to allow possible dissociation of the complex during the simulation course. Each system contained in total about 1.3 × 105 atoms including about 4.2 × 104 explicit water molecules as well as approx. 40 Na+ and Cl− ions. This gave an ionic strength of 30 mM NaCl, consistent with that in our previous in vitro experiments.31

The simulations were performed using the Gromacs 4.6 package.42 The AMBER 99SBildn,43 the TIP3P,44 and the Åqvist45 force fields were used to treat the proteins, the water, and the ions, respectively. We performed canonical‐ensemble MD followed by Replica Exchange with Solute Tempering MD simulations in its latest implementation (REST2).46 REST2 requires considerably less number of replicas than standard Replica Exchange MD.46 It is a particularly suitable enhanced sampling scheme for large systems like those studied here.

Each system underwent 1000 steps of steepest‐descent energy minimization with 5000 kcal·mol−1·Å−2 harmonic positional restraints on the protein‐ligand complex, followed by 2500 steps of steepest‐descent and 2500 steps of conjugate‐gradient minimization without restraints. Then the system was gradually heated to 310 K in 5 steps of 100‐ps simulations. Afterward, the system was pre‐equilibrated in the NPT‐ensemble (T = 298 K, P = 1 bar) for 5 ns by coupling the systems with the Nose‐Hoover thermostat47 and the Andersen–Parrinello–Rahman barostat.48 The van der Waals and short‐range electrostatic interactions were cutoff at 12 Å. Long‐range electrostatic interactions were computed using the Particle Mesh Ewald summation (PME)49 method. The LINCS algorithm50 was applied to constrain all the bond lengths, which allowed for a 2‐fs time step.

Finally, each system underwent 672 ns (21 ns × 32 replicas) REST2 simulations in the effective temperature range of 310–430 K. The temperature distribution of the replicas was determined using the Patriksson and van der Spoel approach,51 which enabled the exchange probability of ∼0.45. The trajectories generated at 310 K—excluding the first 3 ns—were used for analysis using Gromacs tools42 and VMD.52 Salt bridge cutoff was 6 Å between N‐O atom pairs of residues of opposite charges. H‐bond cutoff was 3.5 Å for donor–acceptor distance and 30˚ for acceptor–donor–hydrogen angle. For the RMSD calculations and cluster analysis, each trajectory was aligned by RNH1 Cα atoms to characterize the stability of the human Ang variants with respect to RNH1. Cluster analysis was carried out by g_cluster in Gromacs tools42 using the Gromos method.53 Secondary structures were analyzed using the DSSP program.54, 55

Conclusions

Our molecular‐simulation based structural predictions suggest that the G85R/G86R double mutation weakens a number of the RNH1‐Ang interactions, mainly involving Ang Residues 85–89, the C‐terminus and helix 2. This is consistent with the large loss of affinity of Ang GGRRmut compared to that of Ang WT. The Q117G mutation eliminates the side chain of residue 117 and its H‐bonds with RNH1D435, AngI42, and AngT44. However, other intra‐ and intermolecular interactions are enhanced locally and globally. The complex remains nearly identical to the WT conformation but is more rigid. Therefore, Ang QGmut‐based hCFP likely has higher affinity for RNH1 than the WT form, which explains its in vitro sensibility toward RNH1. Combining Q117G with G85R/G86R “counteracts” the effect of the latter by enabling Ang to adjust its position and recover the interactions with RNH1. Again, this is consistent with the in vitro data for Ang GGRR/QGmut, which shows similar sensibility for RNH1 to that of Ang WT.31, 34 Indeed, mutational effects on RNH1‐Ang binding affinity are nonlocal and can be superadditive or subadditive.37 Novel Ang mutant design should take into account the structural flexibility and dynamics. These findings might help design new Ang mutants for IT‐based anticancer therapy.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Jülich Supercomputing Center (Jülich, Germany) for computing resources. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Risberg K, Fodstad O, Andersson Y (2010) Immunotoxins: a promising treatment modality for metastatic melanoma? Ochsner J 10:193–199. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tsutsumi Y, Onda M, Nagata S, Lee B, Kreitman RJ, Pastan I (2000) Site‐specific chemical modification with polyethylene glycol of recombinant immunotoxin anti‐Tac(Fv)‐PE38 (LMB‐2) improves antitumor activity and reduces animal toxicity and immunogenicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:8548–8553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mossoba ME, Onda M, Taylor J, Massey PR, Treadwell S, Sharon E, Hassan R, Pastan I, Fowler DH (2011) Pentostatin plus cyclophosphamide safely and effectively prevents immunotoxin immunogenicity in murine hosts. Clin Cancer Res 17:3697–3705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pai LH, FitzGerald DJ, Tepper M, Schacter B, Spitalny G, Pastan I (1990) Inhibition of antibody response to Pseudomonas exotoxin and an immunotoxin containing Pseudomonas exotoxin by 15‐deoxyspergualin in mice. Cancer Res 50:7750–7753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Skrlj N, Vranac T, Popovic M, Curin Serbec V, Dolinar M (2011) Specific binding of the pathogenic prion isoform: development and characterization of a humanized single‐chain variable antibody fragment. PLoS One 6:e15783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mathew M, Verma RS (2009) Humanized immunotoxins: a new generation of immunotoxins for targeted cancer therapy. Cancer Sci 100:1359–1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Olson KA, Fett JW, French TC, Key ME, Vallee BL (1995) Angiogenin antagonists prevent tumor growth in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92:442–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Czech A, Wende S, Morl M, Pan T, Ignatova Z (2013) Reversible and rapid transfer‐RNA deactivation as a mechanism of translational repression in stress. PLoS Genet 9:e1003767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. St Clair DK, Rybak SM, Riordan JF, Vallee BL (1987) Angiogenin abolishes cell‐free protein synthesis by specific ribonucleolytic inactivation of ribosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 84:8330–8334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shapiro R, Riordan JF, Vallee BL (1986) Characteristic ribonucleolytic activity of human angiogenin. Biochemistry 25:3527–3532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Saxena SK, Rybak SM, Davey RT, Jr. , Youle RJ, Ackerman EJ (1992) Angiogenin is a cytotoxic, tRNA‐specific ribonuclease in the RNase A superfamily. J Biol Chem 267:21982–21986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rybak SM, Vallee BL (1988) Base cleavage specificity of angiogenin with Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Escherichia coli 5S RNAs. Biochemistry 27:2288–2294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yamasaki S, Ivanov P, Hu GF, Anderson P (2009) Angiogenin cleaves tRNA and promotes stress‐induced translational repression. J Cell Biol 185:35–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ivanov P, Emara MM, Villen J, Gygi SP, Anderson P (2011) Angiogenin‐induced tRNA fragments inhibit translation initiation. Mol Cell 43:613–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Emara MM, Ivanov P, Hickman T, Dawra N, Tisdale S, Kedersha N, Hu GF, Anderson P (2010) Angiogenin‐induced tRNA‐derived stress‐induced RNAs promote stress‐induced stress granule assembly. J Biol Chem 285:10959–10968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stocker M, Tur MK, Sasse S, Krussmann A, Barth S, Engert A (2003) Secretion of functional anti‐CD30‐angiogenin immunotoxins into the supernatant of transfected 293T‐cells. Protein Expr Purif 28:211–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Krauss J, Arndt MA, Vu BK, Newton DL, Rybak SM (2005) Targeting malignant B‐cell lymphoma with a humanized anti‐CD22 scFv‐angiogenin immunoenzyme. Br J Haematol 128:602–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Huhn M, Sasse S, Tur MK, Matthey B, Schinkothe T, Rybak SM, Barth S, Engert A (2001) Human angiogenin fused to human CD30 ligand (Ang‐CD30L) exhibits specific cytotoxicity against CD30‐positive lymphoma. Cancer Res 61:8737–8742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Reiners KS, Hansen HP, Krussmann A, Schon G, Csernok E, Gross WL, Engert A, Von Strandmann EP (2004) Selective killing of B‐cell hybridomas targeting proteinase 3, Wegener's autoantigen. Immunology 112:228–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schirrmann T, Krauss J, Arndt MA, Rybak SM, Dubel S (2009) Targeted therapeutic RNases (ImmunoRNases). Expert Opin Biol Ther 9:79–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yoon JM, Han SH, Kown OB, Kim SH, Park MH, Kim BK (1999) Cloning and cytotoxicity of fusion proteins of EGF and angiogenin. Life Sci 64:1435–1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. De Lorenzo C, Di Malta C, Cali G, Troise F, Nitsch L, D'Alessio G (2007) Intracellular route and mechanism of action of ERB‐hRNase, a human anti‐ErbB2 anticancer immunoagent. FEBS Lett 581:296–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lee FS, Vallee BL (1989) Binding of placental ribonuclease inhibitor to the active‐site of angiogenin. Biochemistry 28:3556–3561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee FS, Vallee BL (1993) Structure and action of mammalian ribonuclease (angiogenin) inhibitor. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol 44:1–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Leland PA, Raines RT (2001) Cancer chemotherapy–ribonucleases to the rescue. Chem Biol 8:405–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Erickson HA, Jund MD, Pennell CA (2006) Cytotoxicity of human RNase‐based immunotoxins requires cytosolic access and resistance to ribonuclease inhibition. Protein Eng Des Sel 19:37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Furia A, Moscato M, Cali G, Pizzo E, Confalone E, Amoroso MR, Esposito F, Nitsch L, D'Alessio G (2011) The ribonuclease/angiogenin inhibitor is also present in mitochondria and nuclei. FEBS Lett 585:613–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rutkoski TJ, Raines RT (2008) Evasion of ribonuclease inhibitor as a determinant of ribonuclease cytotoxicity. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 9:185–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shapiro R, Vallee BL (1987) Human placental ribonuclease inhibitor abolishes both angiogenic and ribonucleolytic activities of angiogenin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 84:2238–2241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Haigis MC, Kurten EL, Raines RT (2003) Ribonuclease inhibitor as an intracellular sentry. Nucleic Acids Res 31:1024–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cremer C, Vierbuchen T, Hein L, Fischer R, Barth S, Nachreiner T (2015) Angiogenin mutants as novel effector molecules for the generation of fusion proteins with increased cytotoxic potential. J Immunother 38:85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dickson KA, Kang DK, Kwon YS, Kim JC, Leland PA, Kim BM, Chang SI, Raines RT (2009) Ribonuclease inhibitor regulates neovascularization by human angiogenin. Biochemistry 48:3804–3806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Russo N, Shapiro R, Acharya KR, Riordan JF, Vallee BL (1994) Role of glutamine‐117 in the ribonucleolytic activity of human angiogenin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91:2920–2924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cremer C, Braun H, Mladenov R, Schenke L, Cong X, Jost E, Brummendorf TH, Fischer R, Carloni P, Barth S, et al. (2015) Novel angiogenin mutants with increased cytotoxicity enhance the depletion of pro‐inflammatory macrophages and leukemia cells ex vivo. Cancer Immunol Immunother 64:1575–1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Papageorgiou AC, Shapiro R, Acharya KR (1997) Molecular recognition of human angiogenin by placental ribonuclease inhibitor—an X‐ray crystallographic study at 2.0 angstrom resolution. Embo J 16:5162–5177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Leonidas DD, Shapiro R, Subbarao GV, Russo A, Acharya KR (2002) Crystallographic studies on the role of the C‐terminal segment of human angiogenin in defining enzymatic potency. Biochemistry 41:2552–2562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chen CZ, Shapiro R (1999) Superadditive and subadditive effects of “hot spot” mutations within the interfaces of placental ribonuclease inhibitor with angiogenin and ribonuclease A. Biochemistry 38:9273–9285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Eswar N, Webb B, Marti‐Renom MA, Madhusudhan MS, Eramian D, Shen MY, Pieper U, Sali A (2006) Comparative protein structure modeling using Modeller. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics Chapter 5:Unit 5 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39. Guex NPM (1997) SWISS‐MODEL and the Swiss‐PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis 18:2714–2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Weichenberger CX, Sippl MJ (2007) NQ‐Flipper: recognition and correction of erroneous asparagine and glutamine side‐chain rotamers in protein structures. Nucl Acids Res 35:W403–W406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gordon JC, Myers JB, Folta T, Shoja V, Heath LS, Onufriev A (2005) H++: a server for estimating pKas and adding missing hydrogens to macromolecules. Nucl Acids Res 33:W368–W371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hess B, Kutzner C, van der Spoel D, Lindahl E (2008) GROMACS 4: algorithms for highly efficient, load‐balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J Chem Theory Comput 4:435–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lindorff‐Larsen K, Piana S, Palmo K, Maragakis P, Klepeis JL, Dror RO, Shaw DE (2010) Improved side‐chain torsion potentials for the Amber ff99SB protein force field. Proteins 78:1950–1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Impey RW, Klein ML (1983) Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J Chem Phys 79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Aqvist J (1990) Ion water interaction potentials derived from free‐energy perturbation simulations. J Phys Chem 94:8021–8024. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wang LL, Friesner RA, Berne BJ (2011) Replica exchange with solute scaling: a more efficient version of replica exchange with solute tempering (REST2). J Phys Chem B 115:9431–9438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nose S, Klein ML (1983) Constant pressure molecular‐dynamics for molecular‐systems. Mol Phys 50:1055–1076. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Parrinello M, Rahman A (1981) Polymorphic transitions in single‐crystals—a new molecular‐dynamics method. J Appl Phys 52:7182–7190. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Darden T, Perera L, Li LP, Pedersen L (1999) New tricks for modelers from the crystallography toolkit: the particle mesh Ewald algorithm and its use in nucleic acid simulations. Structure 7:R55–R60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hess B, Bekker H, Berendsen HJC, Fraaije JGEM (1997) LINCS: a linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J Comput Chem 18:1463–1472. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Patriksson A, van der Spoel D (2008) A temperature predictor for parallel tempering simulations. Phys Chem Chem Phys 10:2073–2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K (1996) VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J Mol Graph Model 14:33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Daura X, Gademann K, Jaun B, Seebach D, van Gunsteren WF, Mark AE (1999) Peptide folding: when simulation meets experiment. Angew Chem Intl Ed 38:236–240. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kabsch W, Sander C (1983) Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen‐bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers 22:2577–2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Joosten RP, te Beek TA, Krieger E, Hekkelman ML, Hooft RW, Schneider R, Sander C, Vriend G (2011) A series of PDB related databases for everyday needs. Nucl Acids Res 39:D411–D419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information