Abstract

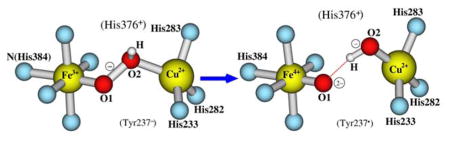

Broken-Symmetry density functional calculations have been performed on the [Fea3, CuB] dinuclear center (DNC) of ba3 cytochrome c oxidase from Thermus thermophilus in the states of [Fea33+-(HO2)−-CuB2+, Tyr237−] and [Fea34+=O2−, OH−-CuB2+, Tyr237•], using both PW91-D3 and OLYP-D3 functionals. Tyr237 is a special tyrosine cross-linked to His233, a ligand of CuB. The calculations have shown that the DNC in these states strongly favors protonation of His376, which is above propionate-A, but not of the carboxylate group of propionate-A. The energies of the structures obtained by constrained geometry optimizations along the O-O bond cleavage pathway between [Fea33+-(O-OH)−-CuB2+, Tyr237−] and [Fea34+=O2−···HO−-CuB2+, Tyr237•] have also been calculated. The transition of [Fea33+-(O-OH)−-CuB2+, Tyr237−] → [Fea34+=O2−···HO−-CuB2+, Tyr237•] shows a very small barrier, which is less than 3.0/2.0 kcal mol−1 in PW91-D3/OLYP-D3 calculations. The protonation state of His376 does not affect this O-O cleavage barrier. The rate limiting step of the transition from state A (in which O2 binds with Fea32+) to state PM ([Fea34+=O2−, OH−-CuB2+, Tyr237•], where O-O bond is cleaved) in the catalytic cycle is, therefore, the proton transfer originating from Tyr237 to O-O to form the hydroperoxo [Fea33+-(O-OH)−-CuB2+, Tyr237−] state. The importance of His376 in proton uptake and the function of propionate-A/neutral-Asp372 as a gate to prevent the proton from back-flowing to the DNC are also shown.

Graphic Abstract

The [Fea3, CuB] dinuclear center states along the O-O bond cleavage pathway in ba3 cytochrome c oxidase have been studied with broken-symmetry density functional calculations.

Introduction

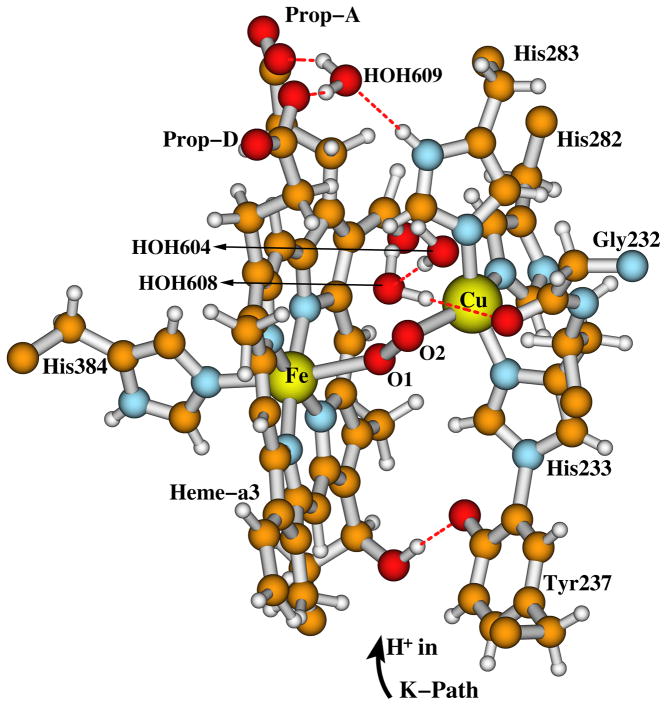

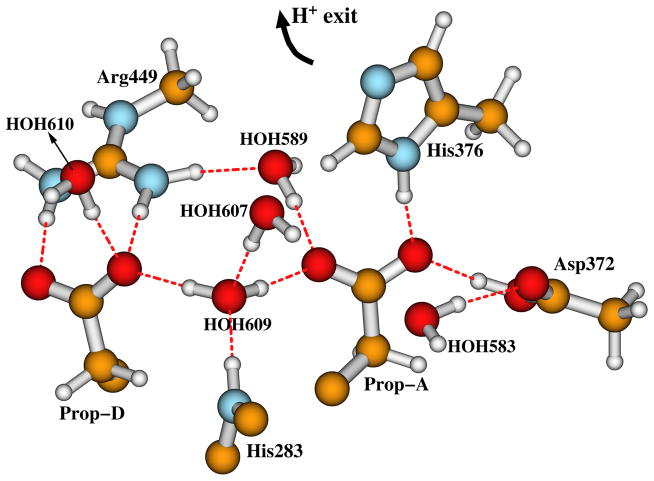

Cytochrome c oxidase (CcO) is the terminal enzyme of the respiratory chain in the inner mitochondrial membrane of eukaryotes or alternatively in the periplasmic membrane in aerobic bacteria. It reduces O2 to H2O and pumps protons across the membrane to create the chemiosmotic proton gradient.1–4 The catalytic site of CcO which binds and reduces O2 by 4e−/4H+ transfer contains a heme a3 (Fea3) and a Cu ion (CuB) — forming the dinuclear (or binuclear) center (DNC or BNC). CuB is in the proximity (~5 Å) of Fea3.5–15 Further, a CcO protein contains another two redox centers: a homodinuclear Cu dimer (CuA) which serves as the initial site of electron entry to CcO,16,17 and another heme, which is heme A (Fea) in the case of aa3 type of CcO, or heme B (Feb) in ba3 type of CcO. The structures and components of the DNC’s in aa3 and ba3 types of CcO’s are very similar.10–15 The DNC observed in the X-ray crystal structure (pdb code: 3S8G, 1.7 Å resolution)15 of ba3 CcO from Thermus thermophilus (Tt) is shown in Figure 1. The Fea3 site has one histidine ligand (His384) and CuB has three histidine ligands: His233, His282, and His283. His233 covalently links with the Tyr237 side chain. This linkage is common to all CcO’s but otherwise unknown in metalloenzymes. There is a water cluster above the DNC. The interstitial water molecules in CcO are probably involved in catalysis by assisting proton transfer and proton pumping, and by providing a water pool and mobile pathway for the product H2O (2H2O molecules per catalytic cycle).12 The water molecules (in 3S8G)15 and the H-bonding residues above the DNC included in our quantum calculation models are shown in Figure 2. HOH609, the two heme propionate carboxylate groups (Prop-A and Prop-D), and part of the His283 side chain are presented in both Figures 1 and 2, in order to show how the two figures are connected. In 3S8G, the water molecule HOH609 has hydrogen bonding interactions with both propionate carboxylate groups, with HOH607, and also with the His283 side chain. Similarly positioned water molecules were also found in other CcO X-ray crystal structures.6,10–13 During the catalytic cycle, protons enter the reaction chamber through the K-path that ends at Tyr237, and exit from the region above the two propionate side chains of the a3-heme into the water cluster.18,19

Figure 1.

The Fea3 and CuB dinuclear center (DNC) observed in the radiolyticly reduced X-ray crystal structure (pdb code: 3S8G with 1.7 Å resolution)15 of ba3 CcO from Thermus thermophilus (Tt). This figure is revised with permission from Figure 1 of Ref 50. Copyright 2013, American Chemical Society.

Figure 2.

The water molecules and the H-bonding residue sidechains above the DNC in the X-ray crystal structure 3S8G.15 Note that in His376+ state, an extra proton is added on top (Nε2) of His376 side chain. This figure is revised with permission from Figure 2 of Ref 50. Copyright 2013, American Chemical Society.

When the DNC is in the reduced state (state R), the molecular O2 binds with Fea32+ and forms a formally Fea33+-O2−···CuB+ state,20–22 which is called state (intermediate) A.23 The next observed state is called PM, which is however, not a peroxide-containing compound (as implied in the notation), but one in which the dioxygen O-O bond has already been cleaved.24–28 Four electrons are needed to transfer to O2 for the O-O bond cleavage. Now it is well established that, among the four electrons, two are from the Fea3 site (Fea32+ → Fea34+), one is from CuB (CuB+ → CuB2+), and the 4th is from the unique cross-linked tyrosine (Tyr237− → Tyr237• radical).29,30 Therefore, the PM state can be represented as [Fea34+=O2−, OH−-CuB2+, Tyr237•]. Although no stable intermediate states between A and PM are observed, it is generally believed that a bridging ferric-hydroperoxide state [Fea33+-(HO2)−-CuB2+, Tyr237−] has to be formed before the O-O bond cleavage, and the proton in the bridging OOH− originates from the unique cross-linked tyrosine.2,31 Correspondingly, heme-O22−-Cu2+ synthetic compounds have been obtained,32–35 and feasible A → PM pathways and intermediate states have been studied theoretically.17,36–40

Using density functional theory (DFT) with the B3LYP potential,41–43 Blomberg et al. calculated the activation energy for cleaving the O-O bond in CcO starting from a peroxide type structure, and compared the calculated activation energies with the observed life time of compound A in aa3 type CcO, which was given as 200 μs (equivalent to 12.4 kcal mol−1 based on transition state theory).39 Their calculations indicate that simultaneous transfer of an electron and a proton from the tyrosine to dioxygen during bond cleavage leads to a barrier more than 10 kcal mol−1 higher than the experimental value. They further found that an “extra” proton in the DNC would lower the calculated activation energy by ~9 kcal mol−1.39 In that model, it was assumed that an extra proton was on the heme-a3 farnesyl hydroxyl group, which has H-bonding interaction with the cross-linked tyrosine side chain. When the tyrosine donated a proton to Fe3+-O-O− (state A), the protonated farnesyl hydroxyl group (−OH2) then transferred a proton to the tyrosine. However, in such a model, their calculations showed that upon further increase of the O-O bond length, the energy of the product state went up. The tyrosine radical could not be produced, and instead, the electron needed for the O-O bond cleavage was taken from the porphyrin ring. Therefore, in order to obtain the stable tyrosine radical, this tyrosine should be in the deprotonated form in the hydroperoxo state.

In this paper, beginning with a proton transfer from the special tyrosine (Tyr237) to the dioxygen, we construct the DNC models in the hydroperoxo [Fea33+-(HO2)−-CuB2+, Tyr237−] state based on the X-ray crystal structure 3S8G of ba3 CcO from Tt, and study the O-O bond breaking barrier of the transition from [Fea33+-(HO2)−-CuB2+, Tyr237−] to state PM [Fea34+=O2−, OH−-CuB2+, Tyr237•] using DFT PW9144 and OLYP45,46 potentials with Grimme’s dispersion corrections (D3).47 Kinetic analysis of time-resolved optical absorption experiments revealed that the A → PM process in ba3 CcO from Tt was only 4.8 μs (equivalent to 10.2 kcal mol−1 based on transition state theory),48 which is faster than in the bovine aa3 system. This 10.2 kcal mol−1 energy includes the cost to generate the hydroperoxide complex from the neutral Tyr237 by proton transfer (A → [Fea33+-(HO2)−-CuB2+, Tyr237−]) and the energy barrier of the O-O cleavage in [Fea33+-(HO2)−-CuB2+, Tyr237−] → PM transition.

An extra “proton”, which was found to lower the O-O cleavage energy in Ref. 39, could instead be the proton at the proton loading site (PLS) near the DNC. It is still not certain where exactly the PLS resides in ba3 CcO’s. Fee et al.17 put an extra proton on top of the His376 side chain (see Fig. 2) to represent the protonated PLS in their ba3 DNC model for the reaction cycle calculations. On the other hand, molecular dynamics simulations and continuum electrostatic calculations performed by Kaila et al. indicated that the carboxylate group of Prop-A could act as a PLS.49 We will therefore analyze whether His376 or Prop-A can hold the “extra” proton, and whether the “extra” proton in the system lowers the O-O bond cleavage barrier.

Models and Compuational Methods

The initial Cartesian coordinates of the Fea33+-(HO2)−-CuB2+, Tyr237− and Fea34+=O2−, OH−-CuB2+, Tyr237• DNC structures in our calculations are taken from the X-ray crystal structure 3S8G.15 A dioxygen species (O1-O2), which was proposed as HO2− based on our DFT calculations,50 was observed between Fea3 and CuB in this radiolyticly reduced X-ray structure. This HO2− likely comes from the recombination of two radiation produced HO• radicals formed either very near to or even in the space between the two metals of the DNC during irradiation.15 The radiolyticly reduced structure is “off” the catalytic pathway, but still provides a very useful starting point for constructing and optimizing “on pathway” intermediates, particularly peroxo- and hydroperoxo-intermediates (see states 4, 52, 5, 62, and 6 in Ref 40). The size of our quantum DNC model (204/205 atoms) is basically the combination of figures 1 and 2, with different protonation states of the His376 side chain and the carboxylate group of Prop-A. The total charge of the system is zero (204 atoms) when His376 is neutral and the carboxylate group of Prop-A is not protonated, and is 1 (205 atoms) when His376 or Prop-A is protonated. The details of the oxygen components between the Fea33+/4+ and CuB2+ centers will be discussed in the Results section. In our DNC model, the Cα atoms of Tyr237, His282, His283, Asp372, His376, and His384 are each replaced with a link H atom (Hlink) along the original Cβ-Cα direction with the Cβ-Hlink distance 1.09 Å. The Cγ of Arg449, N of Gly232, C of His233, and C228 of the geranyl sidechain of the a3-heme are also replaced with an Hlink atom. During geometry optimization calculations, Hlink atoms on Tyr237, His282, His283, Asp372, His376, His384, and Arg449, and the Cα atom of Gly232 are fixed.

Two DFT exchange-correlation functionals, PW9144 and OLYP43,44 with Grimme’s dispersion corrections (D3)47 are used and compared in the current calculations. Fee et al. calculated the reaction free energies of several small-molecule reactions which involve oxygen chemistry (e.g. O2gas + H2gas → H2O2gas, see Table 3 of Ref 17), and found that in most of the cases, the PW91 potential yields better reaction free energies (closer to experimental results) than B3LYP and B3LYP* DFT hybrid potentials.17 For the reaction O2(aq) + 4e−(from cyt c) + 8H+(aq,pH=7) → 2H2O(liquid) + 4H+(aq,pH=3), PW91 also yields the closest reaction free energy (−27.3 kcal mol−1) to experiment (−36.9 kcal mol−1), compared with the corresponding results obtained from other potentials: OLYP(−19.2 kcal mol−1), OPBE(−21.4 kcal mol−1), B3LYP(−26.2 kcal mol−1), and B3LYP*(−24.7 kcal mol−1).40 On the other hand, based on the calculations for relative spin-state energetics of Fe2+ and Fe3+ heme models performed by Vancoillie, et al,51 none of the tested density functionals (B3LYP, B3LYP*, OLYP, BP86, TPSS, TPSSh, M06, and M06-L) consistently provides better accuracy than CASPT2 (multiconfigurational perturbation theory) for all their model complexes against available high-level coupled cluster singles and doubles (CCSD) results. However, the pure functional OLYP yields similar results to the hybrid functionals B3LYP* or B3LYP. And for their large heme models, the results of OLYP, B3LYP and B3LYP* are reasonably close to the best estimate of the spin-splittings, with errors typically ≤ 6 kcal mol−1.51 Radoń and Pierloot also investigated the performance of the CASSCF/CASPT2 approach and several DFT functionals (PBE0, B3LYP, BP86, and OLYP) in calculating the bonding of CO, NO, and O2 molecules to two model heme systems.52 They have found that the experimentally available binding energies are best reproduced by the CASPT2 method and with the OLYP functional. The CASSCF spin populations most closely correspond to the results obtained with the pure OLYP or BP86 rather than with the hybrid functionals.52 Therefore, we have used the OLYP functional in studying the geometric, energetic, and Mössbauer properties of Tt ba3 CcO,40,50,53 and will also use this functional in the current study.

All calculations are performed using the Amsterdam Density Functional Package (ADF2012.01)54–56 with integration grid accuracy parameter 4.0 within the conductor like screening (COSMO) solvation model.57–60 Since both the cluster and the surrounding protein environment are quite polar and contain many water molecules, to be consistent with Refs. 17, 50, and 53, a large dielectric constant of a simple ketone (ε = 18.5) is applied to the environment in all COSMO calculations. The van der Waals radii 1.5, 1.4, 1.7, 1.52, 1.55, and 1.2 Å are used for atoms Fe, Cu, C, O, N, and H, respectively.17,50 The triple-ζ plus polarization (TZP) Slater-type basis set is applied to the Fe and Cu atoms and double-ζ plus polarization (DZP) basis set to other atoms. The inner cores of C(1s), N(1s), O(1s), Fe(1s,2s,2p), and Cu(1s,2s,2p) are treated by frozen core approximation.

For state [Fea33+-(HO2)−-CuB2+, Tyr237−], we use the “broken-symmetry” (BS) state,61–63 in which the Fea33+ site has spin-up electrons as majority spin and the CuB2+ site has majority spin-down electrons, to represent the low-spin (LS) Fea33+ site antiferromagnetically (AF) coupling with the CuB2+ site. Similarly, for state [Fea34+=O2−, OH−-CuB2+, Tyr237•], we also use BS state calculations to treat the intermediate spin (IS) Fea34+ site AF-coupling with both CuB2+ and Tyr237•.

pKa calculations are also performed in this paper using the following equation40,50,53 to determine whether the system favors an “extra” proton, and whether the “extra” proton favors residing on His376 or Prop-A:

| (1) |

where E(A−) and E(AH) are the calculated “total” energies of the deprotonated (A−) and protonated (AH) states. In ADF, the “total energy” of the system is defined relative to a sum of atomic fragments (spherical spin-restricted atoms). The calculated gas-phase energy of a proton E(H+) is therefore relative to a spin-restricted hydrogen atom. ΔGsol(H+,1atm) is the solvation free energy of a proton at 1 atm pressure. We use the “best available” experimental value of −264.0 kcal mol−1 for this term, based on analysis of cluster-ion solvation data.64–67 For E(H−), here we take the empirically corrected values 291.5 kcal mol−1 (i.e. 12.64 eV) for PW91 and 293.1 kcal mol−1 (i.e. 12.71 eV) for OLYP based on experimental standard hydrogen electrode energy and the proton solvation free energy (see Appendix in Ref. 40). The translational entropy contribution to the gas-phase free energy of a proton is taken as −TΔSgas(H+) = −7.8 kcal mol−1 at 298 K and 1 atm pressure.68 (5/2)RT = 1.5 kcal mol−1 includes the proton translational energy (3/2)RT and PV = RT.68 The term ΔZPE is the zero point energy difference for the deprotonated state (A−) minus the protonated state (AH), and it is usually about −8.0 kcal mol−1. For simplicity we take ΔZPE = −8.0 kcal mol−1 in this paper for both PW91 and OLYP calculations on His376 and Prop-A.53

Results and Discussion

Hydroperoxo DNC State [Fea33+-(O-OH)−-CuB2+, Tyr237−] vs. [Fea33+-(HO-O)−-CuB2+, Tyr237−] with Neutral His376 or Protonated His376+

Depending on which oxygen atom (O1 or O2, see Figure 1) becomes protonated, potentially there are two forms of the hydroperoxo DNC state: (1) [Fea33+-(O-OH)−-CuB2+, Tyr237−], where the proton is on O2 that is closer to CuB; and (2) [Fea33+-(HO-O)−-CuB2+, Tyr237−], where the proton is on O1 that is closer to Fea3. Form (1) is ready for the O-O bond cleavage. It is likely that the proton from Tyr237 directly transfers (through one or two water molecules) to atom O2.39 However, if the bridging peroxo [Fea33+-(O1-O2)2−-CuB2+, Tyr237] state is really formed before the proton transfer,17,33,34,39,40 the atom O1 is actually closer to the −OH group of Tyr237. Here by energetic comparisons, we will see whether the proton favors residing on O1 or O2.

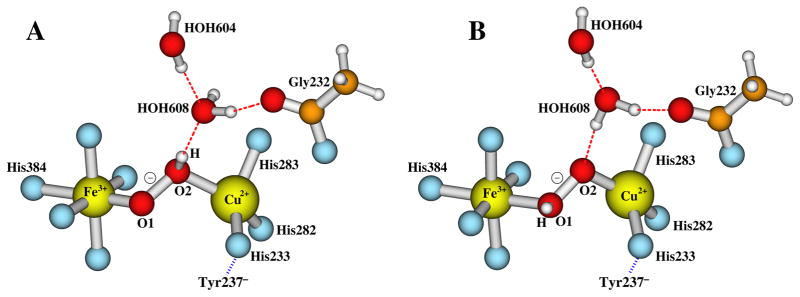

The central DNC structures of the [Fea33+-(O-OH)−-CuB2+, Tyr237−] and [Fea33+-(HO-O)−-CuB2+, Tyr237−] states are given in Figure 3A and 3B, respectively. Two water molecules HOH604 and HOH608 were observed above the dioxygen species in the DNC of the radiolyticly reduced X-ray crystal structure 3S8G.15 HOH608 is within H-bonding distance with both the carbonyl of Gly232 and HOH604.15 We also kept these two water molecules in our DNC models. In [Fea33+-(OOH)−-CuB2+, Tyr237−], the proton on O2 has H-bonding interaction with HOH608 (Figure 3A). While in [Fea33+-(HO-O)−-CuB2+, Tyr237−], HOH608 H-bonds with O2 (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

The central portions of the hydroperoxo DNC models. A: [Fea33+-(O-OH)−-CuB2+, Tyr237−] with H on O2. B: [Fea33+-(HO-O)−-CuB2+, Tyr237−] with H on O1.

We will use Fe3+-(O-OH)−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376/H376+ and Fe3+-(HO-O)−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376/H376+ (204/205 atoms in the model) to represent the [Fea33+-(O-OH)−-CuB2+, Tyr237−] and [Fea33+-(HO-O)−-CuB2+, Tyr237−] states with neutral-His376/protonated-His376+, respectively. The geometries of the four DNC clusters have been optimized with both PW91 and OLYP potentials with Grimme’s dispersion corrections (D3).47 The main geometric, energetic, pKa(His376), and Mulliken net spin population properties of the eight optimized DNC models are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

PW91-D3 and OLYP-D3 Calculated Properties for the Optimized Geometries of Fe3+-(O-OH)−-Cu2+-Y237− and Fe3+-(HO-O)−-Cu2+-Y237− DNC Models with or without the “Extra” Proton on His376.a

| State | Geometry

|

E | Q | pKa (H376) | Net Spin

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe-O1 | O1-O2 | Cu-O2 | Fe···Cu | Fea3 | CuB | O1 | O2 | Y237 | ||||

| PW91-D3: | ||||||||||||

| Fe3+-(O-OH)−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376 | 1.78 | 1.53 | 2.08 | 4.36 | 2.2 | 0 | 0.81 | −0.37 | 0.15 | −0.06 | −0.33 | |

| Fe3+-(O-OH)−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376+ | 1.78 | 1.53 | 2.10 | 4.38 | 0.0 | 1 | 11.2 | 0.81 | −0.37 | 0.15 | −0.06 | −0.34 |

| Fe3+-(HO-O)−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376 | 2.01 | 1.46 | 1.94 | 4.30 | 13.6 | 0 | 0.74 | −0.47 | −0.01 | −0.19 | 0.09 | |

| Fe3+-(HO-O)−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376+ | 2.00 | 1.47 | 1.94 | 4.31 | 10.8 | 1 | 11.7 | 0.84 | −0.41 | 0.00 | −0.14 | −0.15 |

| OLYP-D3: | ||||||||||||

| Fe3+-(O-OH)−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376 | 1.80 | 1.48 | 2.37 | 4.71 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.89 | −0.30 | 0.15 | −0.03 | −0.52 | |

| Fe3+-(O-OH)−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376+ | 1.79 | 1.49 | 2.32 | 4.67 | 0.0 | 1 | 11.0 | 0.89 | −0.30 | 0.15 | −0.03 | −0.52 |

| Fe3+-(HO-O)−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376 | 2.09 | 1.44 | 1.97 | 4.47 | 12.7 | 0 | 0.78 | −0.44 | −0.03 | −0.25 | 0.12 | |

| Fe3+-(HO-O)−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376+ | 2.08 | 1.45 | 1.98 | 4.50 | 11.8 | 1 | 11.5 | 0.91 | −0.37 | −0.01 | −0.17 | −0.22 |

The calculated properties include geometries (Å), energies (E, offset by −29320.2 kcal mol−1 and −28044.7 kcal mol−1, respectively, in PW91-D3 and OLYP-D3 calculations), the total charge (Q) of the model cluster, the pKa values of the His376 side chain, and the Mulliken net spin populations on Fea3, CuB, O1, O2, and on the heavy atoms of the Tyr237 side chain (the sum total).

The “extra” proton on His376 has no significant effect on the DNC structures of both Fe3+-(O-OH)−-Cu2+-Y237− and Fe3+-(HO-O)−-Cu2+-Y237− states. However, both states favor having the extra proton on His376 with the calculated pKa(H376) value in the range 11.0–11.7 for the PW91-D3 and OLYP-D3 calculations.

The PW91-D3 and OLYP-D3 calculated energies of the Fe3+-(HO-O)−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376/H376+ states are more than 10 kcal mol−1 higher than the corresponding energies of the Fe3+-(O-OH)−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376/H376+ states, showing that the proton transferred from Tyr237 would reside on atom O2 rather than O1, and the O-O bond is ready to cleave after O2 receives the proton.

The calculated net spins (0.81/0.89) on the Fea3 site in Fe3+-(O-OH)−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376+ obtained from PW91-D3/OLYP-D3 calculations reflect that the Fea3 is in low-spin Fea33+ state. The negative sign of the net spins on the CuB site (−0.37/−0.30) show that the spins of the Fea3 and CuB sites are AF-coupled. The net spin values on CuB, especially in OLYP-D3 calculations (−0.30), are rather small for a CuB2+ site. On the other hand, the Tyr237− ring shows substantial net spins with overall −0.34 in PW91-D3 and−0.52 in OLYP-D3 calculations (about 1/3 the net spins are on the O atom). Therefore, the CuB and Tyr237 are in the mixed state between CuB2+-Tyr237− and CuB+-Tyr237•. In OLYP-D3 calculations, the CuB has more CuB+ character, which results in a little longer Cu-O2 and shorter O1-O2 distances in Fe3+-(O-OH)−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376+ than for the corresponding PW91-D3 optimized structure.

The PM DNC State [Fea34+=O2−…OH−-CuB2+, Tyr237•] vs. [Fea34+=O2−···HO−-CuB2+, Tyr237•] with Neutral His376 or Protonated His376+

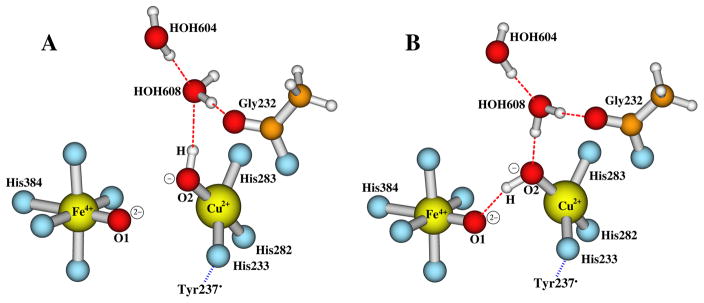

After the cleavage of the O-O bond from the Fe3+-(O-OH)−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376+ state, both Fea33+ and Tyr237− donate an electron to the hydroperoxo group (O2H−) and become Fea34+ and Tyr237• radical, respectively. There are also two potential DNC structures of the PM state can be formed: (1) [Fea34+=O2−…OH−-CuB2+, Tyr237•] (see Figure 4A for the central portion of this DNC cluster). In this state, which is formed by increasing of the O1-O2 distance, the newly formed OH− group that binds with CuB may keep the H-bonding interaction with HOH608. (2) [Fea34+=O2−···HO−-CuB2+, Tyr237•]. As shown in Figure 4B, during the O1-O2 cleavage, the proton on O2 may rotate toward O1 and form a H-bonding interaction with O1. Meanwhile the proton on HOH608 which has no interaction with other groups can rotate toward O2 and form a H-bonding interaction with O2. In order to see which form of the two PM models is energetically more favorable, and whether it is energetically favorably for His376 to remain protonated His376+, we have geometry optimized these two forms of the PM models in both neutral His376 and cationic His376+ states with both PW91-D3 and OLYP-D3 potentials.

Figure 4.

The central portions of two feasible DNC models for the PM state after the O-O bond cleavage. A: [Fea34+=O2−…OH−-CuB2+, Tyr237•] in which the OH− group H-bonds with HOH608. B: [Fea34+=O2−···HO−-CuB2+, Tyr237•] in which the OH− group H-bonds with O2− (O1).

Similar to the section above, here we use Fe4+=O2−…OH−-Cu2+-Y237•-H376/H376+ and Fe4+=O2−···HO−-Cu2+-Y237•-H376/H376+ to represent the [Fea34+=O2−…OH−-CuB2+, Tyr237•] and [Fea34+=O2−···HO−-CuB2+, Tyr237•] states with neutral-His376/protonated-His376+, respectively. The main calculated properties of these DNC clusters are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

PW91-D3 and OLYP-D3 Calculated Properties for the Optimized Geometries of Fe4+=O2−…OH−-Cu2+-Y237• and Fe4+=O2−···HO−-Cu2+-Y237• DNC Models with or without the “Extra” Proton on His376.a

| State | Geometry

|

E | Q | pKa (H376) | Net Spin

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe-O1 | O1···O2 | Cu-O2 | Fe···Cu | Fea3 | CuB | O1 | O2 | Y237 | ||||

| PW91-D3: | ||||||||||||

| Fe4+=O2−…OH−-Cu2+-Y237•-H376 | 1.65 | 2.79 | 1.89 | 4.59 | −0.1 | 0 | 1.11 | −0.50 | 0.78 | −0.32 | −0.71 | |

| Fe4+=O2−…OH−-Cu2+-Y237•-H376+ | 1.65 | 2.75 | 1.89 | 4.54 | −3.9 | 1 | 12.4 | 1.11 | −0.50 | 0.78 | −0.32 | −0.71 |

| Fe4+=O2−···HO−-Cu2+-Y237•-H376 | 1.66 | 2.64 | 1.91 | 4.52 | −14.8 | 0 | 1.25 | −0.52 | 0.75 | −0.17 | −0.89 | |

| Fe4+=O2−···HO−-Cu2+-Y237•-H376+ | 1.66 | 2.64 | 1.91 | 4.55 | −17.7 | 1 | 11.8 | 1.25 | −0.52 | 0.75 | −0.17 | −0.89 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| OLYP-D3: | ||||||||||||

| Fe4+=O2−…OH−-Cu2+-Y237•-H376 | 1.64 | 3.06 | 1.89 | 4.99 | −10.6 | 0 | 1.17 | −0.48 | 0.87 | −0.31 | −0.87 | |

| Fe4+=O2−…OH−-Cu2+-Y237•-H376+ | 1.65 | 3.14 | 1.89 | 5.09 | −12.0 | 1 | 11.8 | 1.17 | −0.48 | 0.88 | −0.30 | −0.90 |

| Fe4+=O2−···HO−-Cu2+-Y237•-H376 | 1.65 | 2.89 | 1.92 | 4.95 | −17.6 | 0 | 1.25 | −0.51 | 0.82 | −0.23 | −0.93 | |

| Fe4+=O2−···HO−-Cu2+-Y237•-H376+ | 1.65 | 2.87 | 1.93 | 4.93 | −18.9 | 1 | 11.8 | 1.25 | −0.51 | 0.81 | −0.23 | −0.93 |

The calculated properties include geometries (Å), energies (E, offset by −29320.2 kcal mol−1 and −28044.7 kcal mol−1, respectively, in PW91-D3 and OLYP-D3 calculations), the total charge (Q) of the model cluster, the pKa values of the His376 side chain, and the Mulliken net spin populations on Fea3, CuB, O1, O2, and on the heavy atoms of the Tyr237 side chain (the sum total).

After the cleavage of the O-O bond, the net spin values on CuB (0.48–0.52) and Tyr237 (0.71–0.93), especially in the geometry optimized Fe4+=O2−···HO−-Cu2+-Y237•-H376/H376+ states are significantly increased in both PW91-D3 and OLYP-D3 calculations, showing CuB and Tyr237 are indeed in the CuB2+ and Tyr237• radical states. In the ideal ionic limit, the net unpaired spin population for an intermediate-spin Fe4+ site is 2 (the Mulliken unpaired spin population is measured in unpaired electron spin units, so 2 unpaired spins corresponds to total spin S = 1). However, the absolute calculated net-spins on Fea34+ in Table 2 are all smaller than 2. In fact, the sum of the net-spins on Fea34+ (1.11–1.25) and O1 (0.75–0.88) for each DNC cluster is about 2, indicative of substantial Fea34+=O2− covalency.

PW91-D3 and OLYP-D3 calculations yield very similar results for Fe-O1 and Cu-O2 distances in Table 2. However, the O1-O2 distances predicted by the PW91-D3 potential, especially for the Fe4+=O2−…OH−-Cu2+-Y237•-H376/H376+ clusters, are much shorter (by 0.23–0.39 Å) than the corresponding values predicted by the OLYP-D3 potential. At this shorter distance, one expects increased repulsion between the oxygen atoms O1 and O2 for PW91-D3 compared to OLYP-D3 in the Fe4+=O2−…OH−-Cu2+-Y237•-H376/H376+ cluster, consistent with the trend in the reaction energy for O-O bond cleavage. Starting from Fe3+-(O-OH)−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376/H376+, the reaction energy is only 2.3/3.9 kcal mol−1 in PW91-D3, compared to 10.9/12.0 kcal mol−1 in OLYP-D3 calculations. However, both for PW91-D3 and OLYP-D3, the energies of the Fe4+=O2−···HO−-Cu2+-Y237•-H376/H376+ states are much lower than the corresponding Fe4+=O2−…OH−-Cu2+-Y237•-H376/H376+ states (by 6.9–14.7 kcal mol−1). These results indicate the presence of strong hydrogen bonding across the Fe4+=O2−···HO−-Cu2+ bridge. Further, the pKa calculations show that the His376 side chain is still in the protonated His376+ form. Therefore, after O-O cleavage, the PM state of the DNC favors the Fe4+=O2−···HO−-Cu2+-Y237•-H376+ conformation with H-bonding between Fe4+=O2− and HO−-Cu2+ and with an “extra” proton on His376+.

Energy Barriers of the O-O Cleavage in Fe3+-(O-OH)−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376/H376+ → Fe4+=O2−···HO−-Cu2+-Y237•-H376/H376+

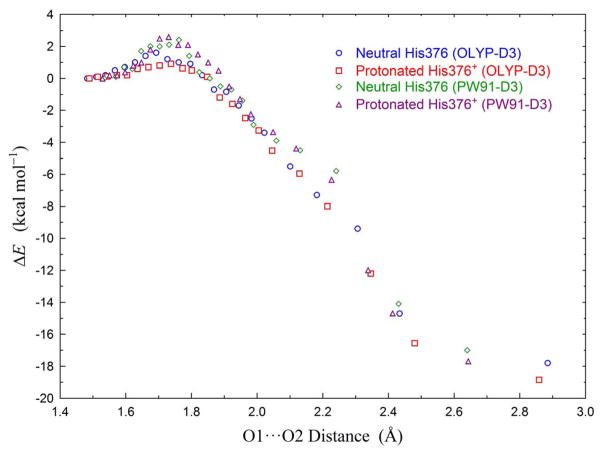

In the above sections, we have concluded that the hydroperoxo state of the DNC favors the Fe3+-(O-OH)−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376+ conformation (Figure 3A) with the proton on O2 and with an “extra” proton on His376+. If the O1-O2 bond is cleaved, this DNC structure will transit to the Fe4+=O2−···HO−-Cu2+-Y237•-H376+ state (Figure 4B). In order to estimate the energy barrier of the O1-O2 cleavage, a path that connects the Fe3+-(O-OH)−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376+ and Fe4+=O2−···HO−-Cu2+-Y237•-H376+ optimized geometries is constructed individually for PW91-D3 and OLYP-D3 potentials by linear interpolation of the Cartesian-coordinates. Then constrained geometry optimization calculations were performed on these transit structures by fixing the O1 and O2 positions (and the Hlink atoms). For the structures with O1-O2 distance in the region (1.65 Å, 1.90 Å), both H-bonding patterns shown in Figure 4A and 4B were geometry optimized, in order to get the lower-energy conformation. To see if the extra proton on His376+ affects this transition barrier, we also performed similar PW91-D3/OLYP-D3 constrained geometry optimizations on the Fe3+-(O-OH)−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376 → Fe4+=O2−···HO−-Cu2+-Y237•-H376 path. Then for each optimized structure along this path, the relative energy (ΔE) to the corresponding PW91-D3/OLYP-D3 geometry optimized Fe3+-(O-OH)−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376/H376+ state was calculated. The relative energy plots vs. the O1-O2 distance for the four Fe3+-(O-OH)−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376/H376+ → Fe4+=O2−···HO−-Cu2+-Y237•-H376/H376+ transitions obtained from PW91-D3 and OLYP-D3 calculations are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

PW91-D3 and OLYP-D3 transitional energy plots vs. O1-O2 distances along the Fe3+-(O-OH)2−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376/H376+ → Fe4+=O2−···HO−-Cu2−-Y237•-H376/H376+ (Fig. 3A → Fig. 4B) pathway. Energies are relative to the corresponding geometry optimized Fe3+-(O-OH) 2−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376/H376+ state. 1) Blue circles: OLYP-D3 calculations with neutral His376. 2) Red squares: OLYP-D3 calculations with protonated His376+. 3) Green diamonds: PW91-D3 calculations with neutral His376. 4) Purple triangles: PW91-D3 calculations with protonated His376+. The calculated properties of the highest-energy structures are given in Table 3.

Surprisingly, the barriers of these four reaction paths are all very small. When His376 is in neutral state, the highest energy obtained for the Fe3+-(O-OH)−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376 → Fe4+=O2−···HO−-Cu2+-Y237•-H376 transition is 2.4 kcal mol−1 for PW91-D3 and 1.6 kcal mol−1 for OLYP-D3. When an extra proton is on His376, the highest-energy barely changes to 2.6 and 0.9 kcal mol−1, in PW91-D3 and OLYP-D3 calculations, respectively. Therefore, the extra proton on His376 does not have a significant effect on the O-O bond cleavage barrier. In Ref 40 (state 62 → 6), we have computed the energy cost from neutral Tyr237 to the ferric peroxo isomer [Fea33+-(O-O)2−-CuB2+, Tyr237], which is 6 kcal mol−1 in PW91-D3 and 6.5 kcal mol−1 in OLYP-D3 calculations. This additional cost should be added to the cumulative barrier69 of the A → PM transition. Then the A → PM activation energy is around 8.6/7.4 kcal mol−1 in PW91-D3/OLYP-D3 calculations. Therefore, the experimental A → PM barrier of 10.2 kcal mol−1 is closely predicted by both PW91-D3 and OLYP-D3 calculations. The rate limiting step of the A → PM transition is the proton transfer from Tyr237 to O-O. Once the hydroperoxo state Fe3+-(O-OH)−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376+ is formed, the O-O bond is readily cleaved.

The calculated properties of the four highest-energy structures of the four profiles in Figure 5 are given in Table 3. The DNC reaches the highest energy when the O1-O2 distance increases by ~0.2 Å from the initial Fe3+-(O-OH)−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376/H376+ state. The calculated net spin values on Fea3, CuB, and Tyr237 in the four structures are all similar to the corresponding values in the Fe3+-(O-OH)−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376/H376+ state, as would be expected for an early transition state.

Table 3.

The Relative Energies (−E, kcal mol−1), Geometric Properties (Å) and Mulliken Net-Spin Populations of the Highest Energy Structures in Figure 5.a

| Transition | Highest ΔE | Geometry

|

Net Spin

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe-O1 | O1-O2 | Cu-O2 | Fea3 | CuB | O1 | O2 | Y237 | ||

| PW91-D3: | |||||||||

| Fe3+-(O-OH)−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376 → Fe4+=O2−···HO−-Cu2+-Y237•-H376 | 2.4 | 1.68 | 1.76 | 2.02 | 0.81 | −0.37 | 0.25 | −0.11 | −0.35 |

| Fe3+-(O-OH)−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376+ → Fe4+=O2−···HO−-Cu2+-Y237•-H376+ | 2.6 | 1.69 | 1.73 | 2.03 | 0.80 | −0.36 | 0.24 | −0.11 | −0.36 |

|

| |||||||||

| OLYP-D3: | |||||||||

| Fe3+-(O-OH)−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376 → Fe4+=O2−···HO−-Cu2+-Y237•-H376 | 1.6 | 1.71 | 1.69 | 2.16 | 0.90 | −0.33 | 0.23 | −0.12 | −0.48 |

| Fe3+-(O-OH)−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376+ → Fe4+=O2−···HO−-Cu2+-Y237•-H376+ | 0.9 | 1.69 | 1.74 | 2.09 | 0.91 | −0.33 | 0.26 | −0.16 | −0.47 |

Energies are relative to the corresponding optimized Fe3+-(O-OH)−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376/H376+ structure given in Table 1.

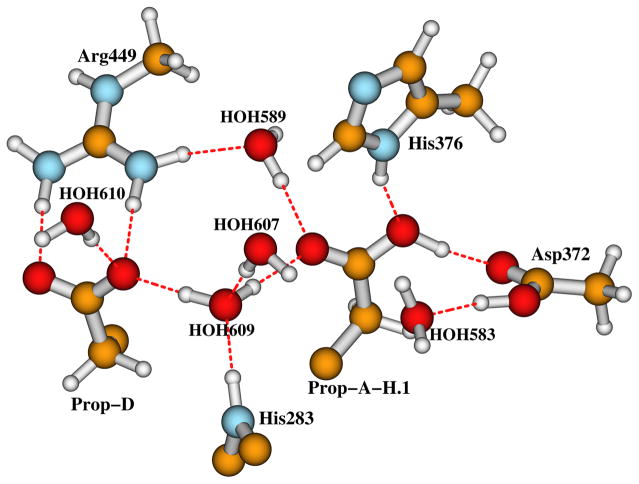

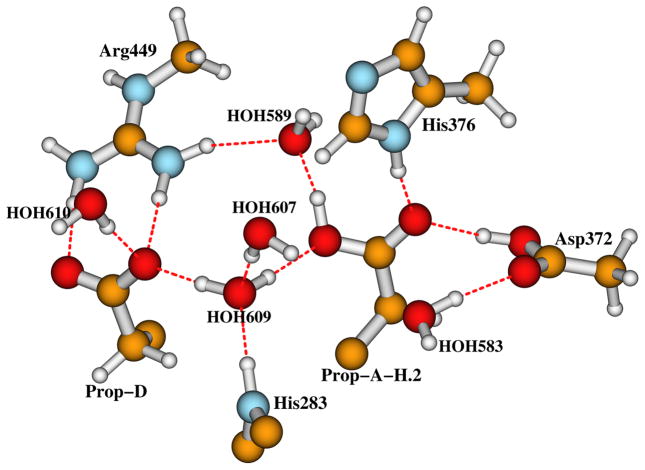

Testing Protonation of Prop-A at Two Alternative Positions

Our calculations have shown that, both Fe3+-(O-OH)−-Cu2+-Y237− and Fe4+=O2−···HO−-Cu2+-Y237• states energetically favor an extra proton on His376. In this section, through pKa calculations, we will study if this “extra” proton would stay on the carboxylate group of Prop-A instead. Theoretically Prop-A can be protonated either at the oxygen atom (we will call it position 1) which is close to Asp372, or at the oxygen atom (position 2) which H-bonds to HOH609 (see Figure 2). Here we investigate different H-bonding pattern of Prop-A with protonation on position 1 or 2. Site-directed mutagenesis experiments have shown that the proton pumping in ba3 CcO from Tt is inhibited by the single Asp372Ile mutation.70 Asp372 therefore plays a critical role in the proton transfer (pumping) pathway. The carboxylate groups of Asp372 and Prop-A are within a strong H-bonding distance in all available X-ray crystal structures of Tt ba3 CcO.10–12,15 Therefore Asp372 is usually considered being in the neutral protonated state (Figure 2).17 In order to add a proton to position 1 of Prop-A in Figure 2, we assume proton transfers from the K-path → Tyr237 → nearby residues (possibly Thr302)71 and H2O molecules → HOH583 → Asp372 → PropA. We then modified the proton positions of Asp372 and HOH583 in Figure 2 and obtained a DNC model with protonated Prop-A at position 1 (Prop-A-H.1, see Figure 6). This protonated carboxylate of Prop-A can rotate, or this proton can move from position 1 to 2, we then constructed another DNC model with protonated Prop-A at position 2 (Prop-A-H.2, see Figure 7).

Figure 6.

An extra proton is added to Prop-A at position 1.

Figure 7.

An extra proton is added to Prop-A at position 2.

Using both PW91-D3 and OLYP-D3 methods, we have optimized the geometries of the Fe3+-(O-OH)−-Cu2+-Y237−-Prop-A-H.1,2 and Fe4+=O2−···HO−-Cu2+-Y237•-Prop-A-H.1,2 states. The main calculated properties of the four states are given in Table 4.

Table 4.

PW91-D3 and OLYP-D3 Calculated Properties for the Fe3+-(OOH)−-Cu2+-Y237− and Fe4+=O2−···HO−-Cu2+-Y237• DNC Models with Prop-A being protonated at position 1 or 2 (see Figs. 6 and 7).

| State | Geometry

|

E | Q | pK a (Prop-A) | Net Spin

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe-O1 | O1-O2 | Cu-O2 | Fe···Cu | Fea3 | CuB | O1 | O2 | Y237 | ||||

| PW91-D3: | ||||||||||||

| Fe3+-(O-OH)−-Cu2+-Y237−-Prop-A-H.1 | 1.79 | 1.53 | 2.13 | 4.44 | 20.0 | 1 | −3.4 | 0.81 | −0.36 | 0.16 | −0.05 | −0.37 |

| Fe3+-(O-OH)−-Cu2+-Y237−-Prop-A-H.2 | 1.78 | 1.54 | 2.11 | 4.41 | 20.8 | 1 | −3.9 | 0.82 | −0.36 | 0.16 | −0.06 | −0.37 |

| Fe4+=O2−···HO−-Cu2+-Y237•-Prop-A-H.1 | 1.66 | 2.64 | 1.91 | 4.55 | 2.0 | 1 | −2.6 | 1.25 | −0.52 | 0.76 | −0.17 | −0.90 |

| Fe4+=O2−···HO−-Cu2+-Y237•-Prop-A-H.2 | 1.66 | 2.64 | 1.91 | 4.53 | 2.0 | 1 | −2.6 | 1.25 | −0.52 | 0.76 | −0.17 | −0.90 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| OLYP-D3: | ||||||||||||

| Fe3+-(OOH)−-Cu2+-Y237−-Prop-A-H.1 | 1.79 | 1.49 | 2.34 | 4.68 | 14.8 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.89 | −0.29 | 0.16 | −0.03 | −0.53 |

| Fe3+-(OOH)−-Cu2+-Y237−-Prop-A-H.2 | 1.80 | 1.49 | 2.36 | 4.70 | 14.7 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.89 | −0.29 | 0.15 | −0.03 | −0.53 |

| Fe4+=O2−···HO−-Cu2+-Y237•-Prop-A-H.1 | 1.65 | 2.83 | 1.92 | 4.83 | −3.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1.25 | −0.51 | 0.81 | −0.23 | −0.93 |

| Fe4+=O2−···HO−-Cu2+-Y237•-Prop-A-H.2 | 1.65 | 2.83 | 1.92 | 4.81 | −4.3 | 1 | 1.1 | 1.26 | −0.51 | 0.81 | −0.23 | −0.92 |

The calculated properties include geometries (Å), energies (E, offset by −29320.2 kcal mol−1 and −28044.7 kcal mol−1, respectively, in PW91-D3 and OLYP-D3 calculations), the total charge (Q) of the model cluster, the pKa values of Prop-A, and the Mulliken net spin populations on Fea3, CuB, O1, O2, and on the heavy atoms of the Tyr237 side chain (the sum total).

It is obvious that the system highly disfavors the extra proton on Prop-A. The calculated pKa’s of the Prop-A site (note that the non-protonated Prop-A states are Fe3+-(O-OH)−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376 given in Table 1 and Fe4+=O2−···HO−-Cu2+-Y237•-H376 in Table 2) are even below zero in PW91-D3 calculations (−3.4, −3.9, −2.6, and −2.6) and are near zero in OLYP-D3 results (0.2, 0.3, 0.5, and 1.1). The energies of the four Fe3+-(O-OH)−-Cu2+-Y237−-Prop-A-H.1,2/Fe4+=O2−···HO−-Cu2+-Y237•-Prop-A-H.1,2 states are much higher than the corresponding Fe3+-(O-OH)−-Cu2+-Y237−-H376+/Fe4+=O2−···HO−-Cu2+-Y237•-H376+ states (in Tables 1 and 2) by 20.0, 20.8, 19.7, and 19.7 kcal mol−1 in PW91-D3 and by 14.8, 14.7, 15.4, and 14.6 kcal mol−1 in OLYP-D3 calculations, respectively. Therefore, the extra proton would reside on His376, but not on Prop-A. The carboxylate group of Prop-A can be a part of the proton transfer pathway to pass on, but unlikely to hold the proton as a PLS.

Conclusions

Our current broken-symmetry DFT calculations on the DNC models of ba3 CcO from Tt show that, if the bridging [Fea33+-(O1-O2) 2−-CuB2+, Tyr237] state exists, atom O2, which is farther from Fea3, should receive the H+ (originated from Tyr237) to form the hydroperoxo [Fea33+-(OOH)−-CuB2+, Tyr237−] state before the O-O bond cleavage. The calculated net spin values indicate that, CuB and Tyr237 appear as a mixture of CuB2+-Tyr237− and CuB+-Tyr237• in the [Fea33+-(OOH)−-CuB2+, Tyr237−] state, and this CuB site has more CuB+ character in OLYP-D3 than in PW91-D3 calculations.

After the O-O bond cleavage, the PM state with Tyr237• radical has the DNC conformation of [Fea34+=O2−···HO−-CuB2+, Tyr237•] with inner H-bonding interaction between O2−and HO−. The calculated O-O bond cleavage barrier in the transition of [Fea33+-(O-OH)−-CuB2+, Tyr237−] → [Fea34+=O2−···HO−-CuB2+, Tyr237•] is very small in both PW91-D3 and OLYP-D3 calculations (0.9–2.6 kcal mol−1). Therefore, the rate limiting step of the A → PM transition is the proton transfer from Tyr237 to O2.

Our calculations on the [Fea33+-(O-OH)−-CuB2+, Tyr237−] and [Fea34+=O2−···HO−-CuB2+, Tyr237•] DNC’s also show that, the system highly favors an extra proton on His376 in these states, but not on the carboxylate group of Prop-A. A histidine residue at the position of His376 is totally conserved in all B-type CcO’s.71 Based on the site-directed mutagenesis experiments on ba3 CcO from Tt,70,71 Asp372, Prop-A, His376, and the nearby water molecules play an important role for proton pumping. The mutants His376Asn and Asp372Ile fail to pump protons.70,71 Our recent molecular dynamics simulations (manuscript under preparation) show that the imidazole group of His376 can easily rotate. This function is important for His376 to uptake the extra proton and serve as the proton loading site. We propose that when the system favors an extra proton on His376, the concerted proton transfer starting from the K-path will occur, in which Asp372 donates its proton to Prop-A and meanwhile receives a proton originated from the K-path, and the imidazole ring of His376 rotates to get the proton from Prop-A and becomes His376+. Because the system is strongly against an extra proton on Prop-A (when Asp372 is neutral-protonated), His376+ cannot give back the extra proton to Prop-A. Therefore, the pair of Prop-A/neutral-Asp372 serves as the gate to prevent the proton from back-flowing to the DNC. The X-ray crystal structures show that the carboxylate group of Glu126II (in subunit II) is close to the Nε2 atom (on top of Figure 2) of His376.10–12,15 When the extra proton on His376 needs to be pumped out at a certain state of the catalytic cycle, the carboxylate of Glu126II can pick up this proton and rotate about its Cβ-Cγ and Cγ-Cδ bonds to swing into the outside region where there are charged side chains and numerous water molecules.17 However, this Glu126II is not essential for proton pumping, since it can be mutated without loss of function.71 Therefore, the extra proton on His376+ can also be picked up by other residues or water molecules and transferred out of the enzyme.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

It is a great pleasure to dedicate this article to Prof. Evert Jan Baerends in honor of his 70th birthday. One of us (LN) worked with Evert Jan as a postdoc at VU Amsterdam about 35 years ago, while another (AWG) worked with him 30 years later. We thank NIH for financial support (R01 GM100934). L. Yang appreciates the support and help from Professor Sanguo Hong, Ning Zhang, and Hongming Wang from Nanchang University, China, and the funding from China Scholarship Council (CSC) for a two-year research visit in the USA. We also thank the computational resources from The Scripps Research Institute. This work also used the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE), which is supported by National Science Foundation (grant number ACI-1053575, resources at the San Diego Supercomputer Center through award TG-CHE130010 to AWG).

Footnotes

The Cartesian coordinates for the optimized clusters discussed in Tables 1–4 with protonated prop-A or His376+ are given as supporting information.

References

- 1.Wikström M. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1817:468–475. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaila VRI, Verkhovsky MI, Wikström M. Chem Rev. 2010;110:7062–7081. doi: 10.1021/cr1002003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Konstantinov AA. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:630–639. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.von Ballmoos C, Adelroth P, Gennis RB, Brzezinski P. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1817:650–657. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iwata S, Ostermeier C, Ludwig B, Michel H. Nature. 1995;376:660–669. doi: 10.1038/376660a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qin L, Hiser C, Mulichak A, Garavito RM, Ferguson-Miller S. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16117–16122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606149103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ostermeier C, Harrenga A, Ermler U, Michel H. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:10547–10553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsukihara T, Aoyama H, Yamashita E, Tomizaki T, Yamaguchi H, ShinzawaItoh K, Nakashima R, Yaono R, Yoshikawa S. Science. 1996;272:1136–1144. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5265.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Svensson-Ek M, Abramson J, Larsson G, Tornroth S, Brzezinski P, Iwata S. J Mol Biol. 2002;321:329–339. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00619-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soulimane T, Buse G, Bourenkov GP, Bartunik HD, Huber R, Than ME. EMBO J. 2000;19:1766–1776. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.8.1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunsicker-Wang LM, Pacoma RL, Chen Y, Fee JA, Stout CD. Acta Crystallogr Sect D Biol Crystallogr. 2005;61:340–343. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904033906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koepke J, Olkhova E, Angerer H, Muller H, Peng GH, Michel H. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1787:635–645. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aoyama H, Muramoto K, Shinzawa-Itoh K, Hirata K, Yamashita E, Tsukihara T, Ogura T, Yoshikawa S. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2165–2169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806391106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu B, Chen Y, Doukov T, Soltis SM, Stout CD, Fee JA. Biochemistry. 2009;48:820–826. doi: 10.1021/bi801759a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tiefenbrunn T, Liu W, Chen Y, Katritch V, Stout CD, Fee JA, Cherezov V. Plos One. 2011;6:e22348. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farver O, Chen Y, Fee JA, Pecht I. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:3417–3421. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fee JA, Case DA, Noodleman L. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:15002–15021. doi: 10.1021/ja803112w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luna VM, Chen Y, Fee JA, Stout CD. Biochemistry. 2008;47:4657–4665. doi: 10.1021/bi800045y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmidt B, McCracken J, Ferguson-Miller S. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15539–15542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2633243100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Varotsis C, Woodruff WH, Babcock GT. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:11131–11136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han SH, Ching YC, Rousseau DL. Biochemistry. 1990;29:1380–1384. doi: 10.1021/bi00458a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshikawa S, Shimada A. Chem Rev. 2015;115:1936–1989. doi: 10.1021/cr500266a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Einarsdottir O. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1229:129–147. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(94)00196-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wikström M. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78:4051–4054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.7.4051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weng LC, Baker GM. Biochemistry. 1991;30:5727–5733. doi: 10.1021/bi00237a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morgan JE, Verkhovsky MI, Wikstrom M. Biochemistry. 1996;35:12235–12240. doi: 10.1021/bi961634e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Proshlyakov DA, Pressler MA, Babcock GT. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:8020–8025. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fabian M, Wong WW, Gennis RB, Palmer G. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:13114–13117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Babcock GT. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:12971–12973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.12971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Proshlyakov DA, Pressler MA, DeMaso C, Leykam JF, DeWitt DL, Babcock GT. Science. 2000;290:1588–1591. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5496.1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gorbikova EA, Belevich I, Wikstrom M, Verkhovsky MI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:10733–10737. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802512105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Halime Z, Kieber-Emmons MT, Qayyum MF, Mondal B, Gandhi T, Puiu SC, Chufan EE, Sarjeant AAN, Hodgson KO, Hedman B, Solomon EI, Karlin KD. Inorg Chem. 2010;49:3629–3645. doi: 10.1021/ic9020993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kieber-Emmons MT, Li YQ, Halime Z, Karlin KD, Solomon EI. Inorg Chem. 2011;50:11777–11786. doi: 10.1021/ic2018727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kieber-Emmons MT, Qayyum MF, Li YQ, Halime Z, Hodgson KO, Hedman B, Karlin KD, Solomon EI. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:168–172. doi: 10.1002/anie.201104080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garcia-Bosch I, Adam SM, Schaefer AW, Sharma SK, Peterson RL, Solomon EI, Karlin KD. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:1032–1035. doi: 10.1021/ja5115198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoshioka Y, Satoh H, Mitani M. J Inorg Biochem. 2007;101:1410–1427. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoshioka Y, Mitani M. Bioinorganic Chemistry and Applications. 2010:182804. doi: 10.1155/2010/182804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blomberg MRA, Siegbahn PEM, Babcock GT, Wikstrom M. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:12848–12858. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blomberg MRA, Siegbahn PEM, Wikström M. Inorg Chem. 2003;42:5231–5243. doi: 10.1021/ic034060s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Noodleman L, Han Du W-G, Fee JA, Götz AW, Walker RC. Inorg Chem. 2014;53:6458–6472. doi: 10.1021/ic500363h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Becke AD. Phys Rev A. 1988;38:3098–3100. doi: 10.1103/physreva.38.3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Becke AD. J Chem Phys. 1993;98:1372–1377. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Becke AD. J Chem Phys. 1993;98:5648–5652. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perdew JP, Chevary JA, Vosko SH, Jackson KA, Pederson MR, Singh DJ, Fiolhais C. Phys Rev B. 1992;46:6671–6687. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.46.6671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Handy NC, Cohen AJ. Mol Phys. 2001;99:403–412. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee CT, Yang WT, Parr RG. Phys Rev B. 1988;37:785–789. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grimme S, Antony J, Ehrlich S, Krieg H. J Chem Phys. 2010;132:154104. doi: 10.1063/1.3382344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Szundi I, Funatogawa C, Fee JA, Soulimane T, Einarsdottir O. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:21010–21015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008603107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaila VRI, Sharma V, Wikstrom M. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta-Bioenergetics. 2011;1807:80–84. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Han Du W-G, Noodleman L. Inorg Chem. 2013;52:14072–14088. doi: 10.1021/ic401858s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vancoillie S, Zhao HL, Radon M, Pierloot K. J Chem Theory Comput. 2010;6:576–582. doi: 10.1021/ct900567c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Radoń M, Pierloot K. J Phys Chem A. 2008;112:11824–11832. doi: 10.1021/jp806075b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Han Du W-G, Noodleman L. Inorg Chem. 2015;54:7272–7290. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b00700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.ADF. Amsterdam Density Functional Software. SCM, Theoretical Chemistry, Vrije Universiteit; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: http://www.scm.com. [Google Scholar]

- 55.te Velde G, Bickelhaupt FM, Baerends EJ, Guerra CF, Van Gisbergen SJA, Snijders JG, Ziegler T. J Comput Chem. 2001;22:931–967. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guerra CF, Visser O, Snijders JG, te Velde G, Baerends EJ. In: Methods and techniques for computational chemistry. Clementi E, Corongiu C, editors. STEF; Cagliari: 1995. pp. 303–395. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Klamt A, Schüürmann G. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans. 1993;2:799–805. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Klamt A. J Phys Chem. 1995;99:2224–2235. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Klamt A, Jonas V. J Chem Phys. 1996;105:9972–9981. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pye CC, Ziegler T. Theor Chem Acc. 1999;101:396–408. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Noodleman L. J Chem Phys. 1981;74:5737–5743. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Noodleman L, Case DA. Adv Inorg Chem. 1992;38:423–470. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Noodleman L, Lovell T, Han W-G, Liu T, Torres RA, Himo F. In: Comprehensive Coordination Chemistry II, From Biology to Nanotechnology. Lever AB, editor. Vol. 2. Elsevier Ltd; 2003. pp. 491–510. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tissandier MD, Cowen KA, Feng WY, Gundlach E, Cohen MH, Earhart AD, Coe JV, Tuttle TR. J Phys Chem A. 1998;102:7787–7794. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Truhlar DG, Cramer CJ, Lewis A, Bumpus JA. J Chem Educ. 2004;81:596–604. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Truhlar DG, Cramer CJ, Lewis A, Bumpus JA. J Chem Educ. 2007;84:934. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Marenich AV, Ho JM, Coote ML, Cramer CJ, Truhlar DG. PCCP. 2014;16:15068–15106. doi: 10.1039/c4cp01572j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tawa GJ, Topol IA, Burt SK, Caldwell RA, Rashin AA. J Chem Phys. 1998;109:4852–4863. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fleck GM. Chemical reaction mechanisms. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 70.von Ballmoos C, Gonska N, Lachmann P, Gennis RB, Adelroth P, Brzezinski P. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:3397–3402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1422434112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chang HY, Choi SK, Vakkasoglu AS, Chen Y, Hemp J, Fee JA, Gennis RB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:5259–5264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107345109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.