Abstract

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) constitute the largest family of molecules that transduce signal across the plasma membrane. Herpesviruses are successful pathogens that evolved diverse mechanisms to benefit their infection. Several human herpesviruses express GPCRs to exploit cellular signaling cascades during infection. These viral GPCRs demonstrate distinct biochemical and biophysical properties that result in the activation of a broad spectrum of signaling pathways. In immune-deficient individuals, human herpesvirus infection and the expression of their GPCRs are implicated in virus-associated diseases and pathologies. Emerging studies also uncover diverse mutations in components, particularly GPCRs and small G proteins, of GPCR signaling pathways that render the constitutive activation of proliferative and survival signal, which contributes to the oncogenesis of various human cancers. Hijacking GPCR-mediated signaling is a signature shared by diseases associated with constitutively active viral GPCRs and cellular mutations activating GPCR signaling, exposing key molecules that can be targeted for anti-viral and anti-tumor therapy.

Keywords: GPCR, signaling, hijack, herpesvirus, pathogens, cancer

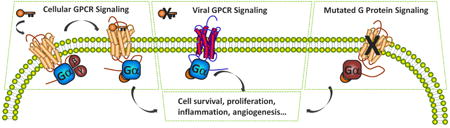

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) family is comprised of over 800 members, making it the largest family of cell-surface molecules. GPCRs can respond to a wide range of stimuli, such as light, ions, odorants, neurotransmitters and bio-active lipids, to elicit diverse signaling cascades [1, 2]. Upon agonist engagement, GPCRs rapidly change their conformation, which couples to the activation of G proteins, including Gα and Gβγ. This is followed by receptor internalization and desensitization, which are regulated by GPCR kinases (GRKs) and arrestins [3]. Gα proteins can be divided into four families: Gαs, Gαi, Gαq and Gα12. Each Gα protein can initiate distinct signaling cascades. Gβγ can also trigger downstream signaling when released from Gα. Notably, GPCRs can also provoke G-protein-independent signaling through β-arrestins or other GPCR scaffold proteins [4].

GPCRs are involved in nearly all physiological processes. Not surprisingly, aberrant expression or mutation of GPCRs and G proteins contributes to many pathological conditions. In fact, GPCRs are the target of around 30% of drugs on the market [5, 6]. Mutated GPCRs and their downstream signaling are emerging as drivers of many oncogenic events, more than previously thought. Surprisingly, nearly 20% of all human tumors carry mutations in GPCRs [7], highlighting the importance of elucidating the oncogenic potential of these mutations. Indeed, mutations in human GPCRs that result in constitutive activation have been linked to diverse human diseases [8]. Moreover, mutations in Gα proteins, especially Gαs and Gαq, are highly represented in various tumors [7]. Mutations in GPCRs and their downstream signaling molecules may provide potential therapeutic targets for disease treatment.

Many human cancer-associated viruses exploit GPCR signaling to benefit their life cycle [9]. Among them, herpesviruses are intricate pathogens that can establish life-long persistent infection in immune competent humans. In particular, reactivation of herpesviruses in immunocompromised patients, such as HIV-infected individuals or organ transplantation recipients, may lead to severe morbidity and mortality [10, 11]. This review will focus on viral G protein-coupled receptors (vGPCR) encoded by human herpesviruses: Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). KSHV and EBV are causally linked to human cancers, while HCMV is believed to modulate the oncogenic process. These viral GPCRs resemble human chemokine receptors and guide immune cells to the site of inflammation and actively participate in many physiological and pathological processes, such as tumor survival, growth and metastasis [12, 13]. Unlike human chemokine receptors, which are predominantly coupled to Gαi, viral GPCRs may signal through several Gα proteins independent of ligand activation [9, 14]. The term “constitutive activation” was coined to describe the ligand-independent signaling capacity of viral GPCRs. Furthermore, viral GPCRs promiscuously bind to a broad spectrum of chemokines, suggesting that they may exploit the host immune system to facilitate viral dissemination as part of the immunopathology of viral infection. The study of the constitutive activity of these viral GPCRs may provide significant insight into how emerging mutations in components of GPCR-mediated signaling relate to human pathology, especially cancer. We will review the signaling events downstream of herpesvirus GPCRs and compare them to pathological signaling events induced by aberrant expression or mutations of cellular GPCRs or Gα proteins.

2. KSHV vGPCR

2.1. KSHV vGPCR and KSHV-associated malignancies

KSHV (also known as human herpesvirus 8 or HHV-8) was originally identified as the etiological agent of Kaposi's sarcoma (KS) in AIDS patients [15]. It is also associated with two rare B cell malignancies, primary effusion lymphoma and multicentric Castleman's disease [16-19]. KS lesions contain highly proliferative KSHV-infected spindle-shaped endothelial cells and abundant erythrocytes among other infiltrated immune cells [20]. It is believed that the inflammatory and angiogenic factors secreted by KSHV-infected cells drive the development of KS tumors [21]. In particular, vGPCR (ORF74) is a viral constitutively active GPCR and its expression leads to cell transformation and tumorigenesis in xenograft mouse model [22, 23]. This was further confirmed by several studies showing that vGPCR transgenic expression in mice can lead to KS-like tumor development [24, 25]. Moreover, vGPCR is a homologue of the human CXCR2 (also known as interleukin 8 receptor, IL8R) and binds to a broad spectrum of CXCL and CCL chemokines. KSHV vGPCR can be detected in KS lesions [26-28]. An elegant study employed an endothelial cell specific retroviral delivery system to demonstrate that the expression of vGPCR, among multiple suspected KSHV oncogenes, was sufficient to induce KS-like tumors in mice [29]. Murine gamma herpesvirus 68 (γHV68) carrying KSHV vGPCR, rather than murine γHV68 GPCR (mGPCR), induced angiogenic lesions in virus-infected mice, offering a murine model of viral oncogenesis in the context of true viral infection [30]. Together, these studies support that KSHV vGPCR may significantly contribute to the sarcomagenesis of KSHV-infected patients.

It seems counterintuitive that vGPCR is implicated in KSHV-induced tumorigenesis, because vGPCR is an early lytic gene and cells supporting lytic viral replication are destined to die [31, 32]. It is only expressed in a small subset of cells (∼5%) in human KS or KS-like lesions in model animals [25, 29, 30, 33]. To reconcile this paradox, it is postulated that dysregulated abortive lytic replication may permit the expression of a subset of lytic genes, including vGPCR, to avoid late gene expression and lysis of host cells. Interestingly, vGPCR is a lytic gene whose expression is up-regulated by RTA [34] and vGPCR also promotes RTA protein expression. Thus RTA and vGPCR signaling constitute a positive feedback loop to increase the expression of early lytic genes[35] rather than genes needed for late gene expression such as ORF31, ORF24, ORF34, ORF18 and ORF30 [36-38]. These observations support the hypothesis that a dysregulated abortive lytic replication program permits GPCR expression and cell transformation of KSHV-infected cells without progressing to late gene expression. vGPCR can activate proliferative signaling and survival pathways via both autocrine and paracrine mechanisms [39]. Furthermore, KSHV-induced tumorigenesis is often associated with immune suppression, consistent with the notion that lytic replication of KSHV is required for KSHV oncogenesis. This is further supported by the observations that lytic replicating cells are invariably found in KS tumors and that inhibition of KSHV lytic replication by antiviral treatment suppresses KSHV tumorigenesis [40]. Thus, tumorigenesis induced by KSHV infection and vGPCR expression defines a new paradigm in which a lytic protein engenders oncogenesis via paracrine and autocrine mechanisms.

Currently, there is no effective treatment for KSHV infection. Thus, antagonists targeting vGPCR and its downstream signaling components may provide new therapeutic strategies to treat KSHV-associated malignancies. To date, no antagonistic compound targeting vGPCR has been reported.

2.2. The constitutive activity of vGPCR

The highly conserved DRY (Asp3.49-Arg3.50-Tyr3.51; Ballesteros and Weinstein notation) motif is essential to GPCR function [41]. In contrast to its KSHV homologue, γHV68 mGPCR doesn't have constitutive activity [30, 42] and it has an HRC motif rather than the conventional DRY motif. Interestingly, KSHV vGPCR has a VRY motif, rather than a DRY motif and the V142D revertant mutation didn't alter the constitutive activity of vGPCR [43]. Surprisingly, introduction of the mutation of residues within the transmembrane helix that are expected to face the lipid bilayer, either Leu91Asp or Leu94Asp, reduced the constitutive activity of vGPCR, but it retained its responsiveness to its agonists such as CXCL1 [43]. In another study, the V142D vGPCR mutant showed >70% increased activity compared to WT vGPCR [44]. Collectively, these studies show that the introduction of the DRY motif into vGPCR results in similar or higher constitutive activity. At this point, it is unclear what structural features account for these observed effects. In contrast, the R to A mutation in the VRY motif abolishes the constitutive activity of vGPCR [44, 45]. The same finding holds true for other GPCRs. Importantly, murine endothelial cells stably expressing the inactive vGPCR R143A mutant are not tumorigenic in vivo [46, 47], supporting the notion that that the constitutive activity of vGPCR is required for its tumorigenesis.

Although the afore-mentioned studies identified key residues that contribute to the constitutive activity of vGPCR, it is believed that a remarkably large number of residue substitutions in KSHV vGPCR compensate for the negative effect caused by the individual substitutions. Consequently, the conformational changes induced by these substitutions shift vGPCR towards an active state, leading to its constitutive activity in triggering downstream G protein-dependent signaling [48]. Identifying the structure of vGPCR will be very informative to define the molecular basis underpinning its constitutive activity and may help to guide screening for vGPCR antagonists.

2.3. Responsiveness to chemokine stimulation

Despite being constitutively active, vGPCR can interact with chemokines and chemokine binding regulates vGPCR signaling and tumorigenesis. vGPCR with point mutations that makes it unresponsive to agonist stimulation has reduced oncogenic potential in transgenic mice [47, 49], suggesting that responsiveness to agonist stimulation, in addition to its constitutive activity, is required for its oncogenic activity. Although being a homologue of human CXCR2, vGPCR induces a set of downstream signaling distinct from those of cellular chemokine receptors. While human chemokine receptors predominantly signal via Gαi proteins, vGPCR promiscuously couples to multiple Gα proteins and activates diverse downstream signaling cascades, such as phospholipase C (PLC) [22], NFAT [50, 51], MAPK [52, 53], PI3K-AKT [54] and Hippo-YAP [55]. Activation of phosophoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) occurs largely through Gαi [54], while activation of YAP is dependent on Gαq/11 and Gα12/13 [55]. Another difference between vGPCR and its cellular homologues is that vGPCR is constitutively active, but still maintains binding to and regulation by various human chemokines, including CXCL1 (full agonist), CXCL8 (low potency agonist), CXCL2 (partial agonist), CXCL10 and CXCL12 (inverse agonist) [56-59]. vGPCR recruits β-arrestins and is subsequently internalized in response to human CXCL1 and CXCL8, but not CXCL10, suggesting that β-arrestin-related signaling is not constitutively activated [45]. vGPCR activity is also regulated by KSHV encoded chemokines and proteins, highlighting its tight regulation during viral infection. vMIP-II, a chemokine encoded within the K3-K7 immune-modulatory locus, inhibits vGPCR signaling and provides a negative regulation to modulate the activation of vGPCR [57, 60]. A small membrane protein, K7, retains vGPCR in the ER and promotes its degradation, thereby reducing its tumorigenesis potential [32].

2.4. The complex signaling network downstream of vGPCR

vGPCR induces NF-κB activation through a pertussis toxin (PTX)-sensitive and Gβγ subunit-mediated pathway in endothelial cells [61]. Further studies indicate that the activation of NF-κB is dependent on PI3K-AKT, but not p38 [62]. Interestingly, several kinases appear to be critical for NF-κB activation by vGPCR. Inflammation-inducible IκB kinase epsilon (IKKε) is required for vGPCR-induced tumorigenesis in vivo [33]. vGPCR activates IKKε to induce NF-κB dependent cytokine production [33]. Transforming growth factor β (TGF-β)-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) is also activated by vGPCR and is required for activation of NF-κB [63]. vGPCR induces the expression cytokines, such as IL-6, IL-8, and CCL5, and adhesion molecules, such as VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and E-selectin, in an NF-κB dependent manner. These secreted factors can activate the NF-κB signalingcascade in neighboring cells [64] and elicit the chemotaxis of immune cells, constituting a feed-forward mechanism of NF-κB activation [62, 65]. The NF-κB pathway has long been considered to be pro-inflammatory and drives the expression of pro-inflammatory genes, including cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules [66]. Interestingly, it is known that IKKε can directly phosphorylate and thereby activiate AKT [67, 68]. Thus, the IKKε-NF-κB and PI3K-AKT signaling pathways are interconnected, suggesting that a ‘cocktail’ strategy of targeting multiple signaling branches may have synergistic effect against vGPCR-induced tumor formation. The activation of the PI3Kγ/Akt/mTOR-signaling axis by vGPCR occurs largely through Gαi [54]. vGPCR-induced AKT activation promotes endothelial cell survival, possibly by stimulating the NF-κB transcription factor [69]. PI3Kγ has been shown to have restricted tissue distribution and it is activated by direct interaction with the Gβγ subunit that is released from Gα proteins upon GPCR activation [70]. AS-605240, a widely used PI3Kγ inhibitor, diminished vGPCR-induced sarcomagenesis as potently as an mTOR inhibitor, rapamycin [54]. Downstream of PI3K, AKT plays essential roles in vGPCR-induced tumorigenesis and pharmacologic inhibition of AKT reduces tumor formation in mouse models [71]. vGPCR also induces AKT activation through a paracrine mechanism and the activation of AKT in neighboring cells is mediated by the action of secreted factors such as VEGF, IL-8 and potentially other cytokines. These secreted cytokines and growth factors activate multiple kinases in bystander cells, including AKT that can promote TSC1/2 phosphorylation, mTOR activation, HIF up-regulation and VEGF production [72].

Small GTPases also actively participate in vGPCR-driven inflammation. vGPCR simulates the secretion of many pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, IL-8, and CXCL1 through activation of the Rac small GTPase. Interestingly, inhibition of Rac1, rather than Rho, blocks vGPCR-induced cytokine secretion and reduces vGPCR-induced tumor growth in vivo [65]. Expression of a constitutively active mutant Rac1 in mice is sufficient to produce high levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which drive the development of KS-like tumors. Treatment with an antioxidant completely abolished tumor formation induced by the constitutively active Rac1, suggesting that KS-related tumors may be treated with an antioxidant [73].

Originally, NFAT activation by vGPCR was thought to be dependent on Gαq [50, 53, 74]. However, it was shown that vGPCR can mobilize calcium release from the ER compartment via inhibiting the Sarco/Endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase (SERCA) [51]. The possible cooperation between Gαq and SERCA signaling warrants further investigation. Nonetheless, it is known that the potent activation of NFAT by vGPCR promotes the secretion of IL-8, Angiopoietin-2 (ANGPT2) and the expression of other NFAT-dependent proteins such as RCAN1 and COX-2, all of which are directly or indirectly implicated in angiogenesis [51, 75]. Similar to NF-κB activation induced by vGPCR, NFAT activation and factors secreted by vGPCR-expressing cells constitute a feed-forward circuit that fuels NFAT activation and chemokine production. This study raises the question of how NFAT activation and chemokine production are circumscribed in vGPCR-expressing cells. Conceivably, negative regulators may curtail the hyper-activation of NFAT, given that hyper-activation of NFAT in endothelial cells induces precocious cell death [76]. Given the inflammatory nature of KS tumors, it is not surprising to find that inhibiting NFAT activation impairs vGPCR-induced tumorigenesis in a xenograph mouse model [51].

vGPCR can also activate AP-1, NF-κB, CREB, and NFAT signaling in primary effusion lymphoma cells (PEL) [77]. While vGPCR-induced activation of AP-1 and CREB requires the Gαq-ERK1/2 and Gαi-PI3K-Src cascades in PEL cells, NF-κB activation by vGPCR is not mediated by Gαi, indicating that NF-κB activation induced by vGPCR is cell type specific [78].

Upon its initial identification, vGPCR was reported to increase VEGF release and promote angiogenesis [23]. vGPCR increasesVEGF production by stimulating HIF1α-mediated transcription, which is dependent on p38 and MAPK [52]. Targeting p38 and MAPK with specific inhibitors reduces the transactivation of HIF1α and VEGF secretion [52]. Activation of HIF1α by KSHV infection and vGPCR-expressioncan up-regulate PKM2, which is sufficient to cause the Warburg effect. PKM2 cooperates with HIF1α to increase VEGF production and promote the angiogenic potential of KSHV-infected cells. These signaling events constitute a feed-forward circuit that engenders angiogenesis. As such, shRNA interference or pharmacological inhibition of PKM2 reduces the tumorigenesis of vGPCR [79]. KSHV infection and vGPCR-expression up-regulates angiopoietin-like 4 (ANGPTL4), which promotes vascular permeability through Rho-ROCK activation in neighboring cells. Inhibition of ANGPTL4 potently blocks vGPCR-induced tumor formation, similar to the extent of VEGF inhibition, suggesting that ANGPTL4 may be a viable therapeutic target for KS treatment [80]. vGPCR expression in lymphatic endothelial cells (LEC) induces Angiopoietin-2 via both autocrine and paracrine mechanisms. Angiopoietin-2 is up-regulated by NFAT activation and functions as an important pro-angiogenic and lymphangiogenic factor [81].

Collectively, these findings implicate that a complex signaling network downstream of vGPCR contributes to the strong inflammatory and angiogenic phenotype of KS tumors. Since there is no effective treatment available, these critical signaling molecules downstream of vGPCR may represent suitable targets to treat KS tumor and the KSHV-associated malignancies.

3. HCMV US28

3.1. US28 and its downstream signaling cascade

HCMV (also known as human herpesvirus 5 or HHV5) belongs to the β-herpesvirus family and is a ubiquitous pathogen that infects up to 90% of the human population [82]. Most infected people are asymptomatic since HCMV remains latent in immune-competent individuals. However, its reactivation in immune-compromised patients and primary infection in infants can cause severe disease.

In contrast to KSHV and EBV, which encode one GPCR, HCMV encodes four GPCRs: US27, US28, UL33 and UL78 [83]. Among these four GPCRs, US28 is the most extensively characterized to date. Similar to vGPCR, US28 promiscuously binds to multiple chemokines. US28 constitutively activates PLCβ and NF-κB through Gαq and Gβγ, respectively [84, 85]. Interestingly, similar to KSHV vGPCR, US28 also mobilizes calcium and activates NFAT by inhibiting SERCA [50, 51]. NFAT activation is critical for US28 oncogenesis, because pharmacological inhibition of NFAT suppresses US28-induced tumor formation in xenograft nude mice [50, 51]. HCMV infection has long been implicated in vascular diseases. US28 promotes smooth muscle cell migration through Gα12 [86-88], implying that US28 contributes to the infiltration of smooth muscle cells into blood vessels. These studies establish a potential link between HCMV infection and vascular disease development. US28 expression induces multiple proliferative and inflammatory factors such as VEGF and IL8, thereby promoting angiogenesis, aberrant cell proliferation and tumor formation in a xenograft mouse model [89]. COX-2 is highly induced by US28 through activation of NFAT and NF-κB [51, 90]. Targeting COX-2 with a pharmacological inhibitor dramatically reduced US28-induced tumor formation in nude mice [90]. US28 contains aclassic DRY motif that engages PLCβ to activate downstream signaling. The R to A mutantin the DRY motif of US28 cannot activate PLCβ, and fails to induce COX-2 or VEGF production, ultimately demonstrating much weaker oncogenic activity in vivo [89-91]. Collectively, these results suggest that G protein-coupling activity is required for US28 signaling and tumorigenesis. VEGF and the subsequent elevation of prostaglandins (e.g., PGE2) driven by COX-2 may confer a growth advantage to both HCMV-infected (US28-expressed) cells and bystander cells to accelerate the development and progression of cancer.

3.2. Implications in cancers

HCMV infection has been linked to cancers of the brain, colon and other organs/tissues [92, 93]. HCMV infection and US28 expression are found in glioblastoma (GBM) [94-97]. HCMV infection correlates with reduced survival rate of glioblastoma patients and anti-HCMV treatment with valganciclovir increases patient survival [94], suggesting that HCMV infection promotes glioblastoma progression. Similarly, HCMV infection can be detected in a large proportion of medulloblastoma tissues and cell lines. Treatment with valganciclovir blocks HCMV replication and reduces medulloblastoma tumor formationin a xenograft mouse model [98]. Mechanistically, HCMV infection and US28 expression induce COX-2 expression, STAT3 activation and the secretion of IL-6 and VEGF, which collectively promote brain tumor development [98]. HCMV US28 can induce IL-6 expression, thereby activating the JAK1-STAT3 signaling axis to promote cell proliferation in both an autocrine and paracrine fashion. Moreover, US28 induces STAT3 phosphorylation in glioblastoma tissue and this correlates with poor patient outcome, supporting the pivotal roles of the JAK1-STAT3 signaling in US28-driven proliferation [97]. It is noteworthy that the IL-6-STAT3 signaling axis is aberrantly activated in a wide range of tumors of the hematological system and some solid organs [99, 100]. US28-mediated increased invasion of primary GBM cells can be further enhanced by CCL5, a known US28 ligand. Knockdown of US28 or treatment with a CCL5 neutralizing antibody inhibits VEGF expression and invasion of GBM cells [92]. These studies indicate that the constitutive and ligand-dependent activity of US28 are involved in the proliferation and invasiveness of brain tumor cells.

HCMV infection is also found in human colorectal cancer [93, 101]. US28 expression is linked to colorectal cancer, because US28 can induce β-catenin activation to promote cell proliferation (discussed in another part of this review). Furthermore, US28 can induce COX-2, which is strongly implicated in colorectal cancer development [90, 102].

3.3. Targeting US28

Mounting evidence supports the conclusion that US28 is causally linked to HCMV-associated inflammatory and proliferative diseases. Extensive effort has been spent to develop inhibitors that target US28 to abrogate its constitutive and ligand-induced activity. To this end, an array of small-molecule compounds that bind to US28 and inhibit its constitutive signaling activity have been identified. A number of compounds that target US28 have been filed for patent protection [14]. VUF2274, originally discovered as a CCR1 antagonist, is among the first to be characterized as a full inverse agonist of US28 [103-105]. VUF2274 and its derivatives abrogate PLCβ activation induced by US28. Di- and tetra-hydro-isoquinolines were identified as promising lead structures as allosteric inverse agonists of US28 and several derivatives have been shown to reduce US28 signaling [106]. Recently, flavonoid-based compounds were shown to inhibit US28 as inverse agonists [107]. A recent study suggests that some inverse agonists of US28 desensitize its downstream signaling via constitutive endocytosis of US28. Using a US28 mutant that lacks most of its constitutive endocytosis activity [108, 109], Nuska Tschammer showed that some of the previously reported US28 inverse agonists can actually function as ‘camouflage’ agonists [110]. However, even these classical inverse agonists suffer from low potency in vitro, which make it difficult to inhibit US28 in vivo. A synthetic CX3CL1 variant fused with the cytotoxic domain of Pseudomonas exotoxin A demonstrated high affinity for US28. This new strategy of making fusion toxin proteins (FTPs) demonstrates strong anti-HCMV activity via binding to US28 in vitro and in vivo [111]. The successful targeting of US28 by pharmacological inhibitors among other strategies apears promising in our search for more effective compounds and new approaches to target viral GPCRs.

3.4. US28 structure

The number of available structures of GPCRs has grown exponentially in the last few years due to methodological advancement. These structures provide invaluable insight into the distinct functional states, ligand binding and signal transduction of GPCRs [112]. The crystal structure of US28 in complex with the chemokine domain of human CX3CL1 was very recently determined [113]. This is the first structure of a viral GPCR and provides critical information concerning structural features underpinning the constitutive activity and chemokine-binding of viral GPCRs. CX3CL1 was shown to function as a ‘camouflage’ agonist for US28 [108] to explain the opposing effect of CX3CL1 on signaling downstream of US28. The structural analysis of CX3CL1-bound US28 clearly shows that CX3CL1 doesn't induce the inactive state of US28, supporting that CX3CL1 is an agonist for US28. Specifically, the conformation of transmembrane helix 6 (TM6), DRY motif in TM3 and NPXXY motif in TM7 of US28 all adopt states of an activated GPCR [114, 115]. Moreover, this study also defines the structural basis underlying the constitutive activity of US28. US28 has a very distinct structure near the DRY motif compared with other chemokine receptors, which may help to destabilize the inactive state [112]. The most important contributing factor is Glu1243.45, which forms an ionic interaction with Arg139 in the second intracellular loop and prevents interaction between Arg139 and Asp1283.49. The strategy that US28 takes to preserve the G protein-binding site is very similar to what the constitutive active mutation does in the photoreceptor rhodopsin [116, 117]. The M257Y6.40 mutation, located in a series of highly conserved hydrophobic residues between the DRY motif in TM3 and the NPxxY motif in TM7, stabilizes the G protein binding site and constitutively activates rhodopsin. The presence of Glu1243.45 seems to be unique for US28, and is not present in human GPCRs or other viral GPCRs such as KSHV vGPCR (Cysteine) and BILF1 (Glycine). Although the presence of VRY in KSHV vGPCR abrogates the ionic interaction in the conventional DRY motif, the V142D revertant mutant doesn't reduce its constitutive activity [43]. The absence of Glu3.45 in vGPCR suggests that the conformational architecture enabling the constitutive activity of vGPCR is likely distinct from that of US28. Alternatively, vGPCR may possess another negatively charged residue that functions similarly to Glu1243.45 in US28. Future detailed structural studies will eventually provide answers to these questions.

3.5. Other HCMV GPCRs

Compared to US28, our knowledge of the other three HCMV GPCRs is rudimentary at best. UL33 is conserved among all β-herpesviruses and promiscuously activates diverse G proteins. It constitutively activates PLC via Gαq/11 and partly via Gαi/o, and it also stimulates the transcription factor CREB through the Rho/p38 pathway via Gβγ [85, 118]. UL78 lacks constitutive activity, but UL33 and UL78 are able to hetero-dimerize with US28 and diminish NF-κB activation induced by US28. These results indicate that UL33 and UL78 can regulate the signaling of US28 [119]. UL33 and UL78 also hetero-dimerize with the HIV co-receptors, CCR5 and CXCR4, to impair their activity [120]. US27 is a heavily glycosylated viral GPCR that is predominantly expressed during the late phase of viral replication [121]. US27 can hetero-dimerize with US28 in vitro [119]. It is required for efficient extracellular virus spread but not required for direct cell-to-cell spread, suggesting that US27may act at late stage to support efficient viral release [122]. Alternatively, US27 may play an essential function during viral entry to extend dissemination in vivo. Additionally, US27 has been shown to enhance CXCR4 signaling, indicating that it may function as an immune regulatory molecule [123].

4. EBV BILF1

EBV (HHV4) is a lymphotropic virus implicated in Burkitt's lymphoma and Hodgkin's lymphoma [124, 125]. The EBV BILF1 gene encodes a GPCR, which is a lytic gene. BILF1 is a constitutively active GPCR coupled to Gαi, and it is proposed that BILF1 activates GαI to regulate viral lytic replication [126]. Instead of the DRY motif, BILF1 contains an EKT (Glu–Lys–Thr) motif. The EKT motif is vital as the K to A mutation in the motif abolishes BILF1 constitutive activity. Interestingly, a BILF1 revertant mutant containing the DRY motif demonstrates reduced signaling and transformation activity [127]. A unique function of BILF1 is to dimerize with CXCR4 and scavenge Gαi proteins and thereby impair signaling downstream of the CXCL12-CXCR4 interaction [128]. BILF1 can also form heterodimers with other chemokine receptors, which may affect the responsiveness of B lymphocytes to chemokines [129]. Other than modulating chemokine signaling, BILF1 actively participates in immune evasion, which will be discussed in another part of this review.

BILF1 expression can transform NIH3T3 cells, in a manner that is dependent on its constitutive activity. Using a xenograft model, BILF1 was shown to induce tumor formation in nude mice [127]. Surprisingly, the mutant that lacks constitutive activity can still induce tumor formation, suggesting that the oncogenic signaling downstream of BILF1 is partly independent of coupling to G proteins [127]. BILF1 is distinct from vGPCR and US28, in that it doesn't inhibit SERCA, nor activate NFAT signaling [51], suggesting that BILF1 is not coupled to Gαq.

5. Other herpesvirus GPCRs

Human herpesvirus-6 (HHV-6) and human herpesvirus-7 (HHV-7) each encode two viral GPCRs, U12 and U51. HHV-6 U12 mobilizes calcium in response to β-chemokines [130]. The HHV-7 U12 gene also encodes a calcium-mobilizing receptor that responds to the stimulation of MIP-3β, but not to other chemokines [131]. Despite that HHV-7 U51 mobilizes calcium in response to β-chemokines, the expression of U51 doesn't promote cell migration towards those chemokines [132]. Although HHV-6 U51 has been shown to specifically bind CCL5 [133], the downstream signaling events of these vGPCRs have not been extensively explored.

Nonhuman herpesviruses also encode open reading frames for viral GPCRs. MHV68 encodes a viral GPCR that is closely related to KSHV vGPCR [134]. Similarly, the murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV) encodes a viral GPCR termed M33, which is related to HCMV US28 [85]. The rhesus rhadinovirus (RRV) GPCR shares highly sequence identity with KSHV vGPCR and its expression induces constitutive signaling activity and promotes tumor formation in nude mice [135]. These viral GPCRs from animal viruses provide a valuable platform for investigating the regulation and roles of viral GPCR in in vivo infection.

6. The similar pathological signaling network of viral and cellular GPCRs

6.1. Regulation of host immune system

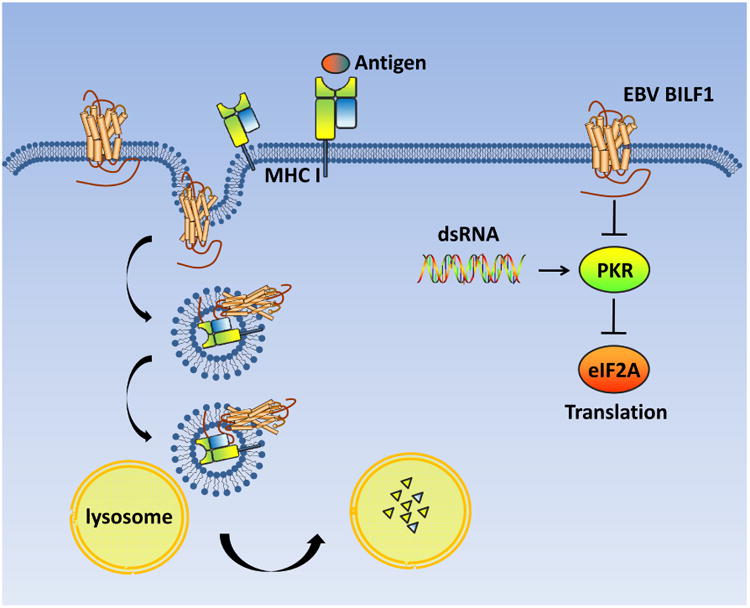

GPCRs, especially receptors for chemokines and other ligands (i.e. bioactive lipids) are crucial in regulating immune function. Those GPCRs detect chemokines in order to mobilize immune cells, while deregulation of chemokine signaling induces inflammation [136, 137]. Among the herpesviral GPCRs, BILF1 is primarily involved in immune regulation. BILF1 is reported to be constitutively active and when coupled to Gαi is sensitive to PTX inhibition [126]. However, BILF1 demonstrates distinct properties from KSHV vGPCR and HCMV US28. For example, both vGPCR and HCMV US28 constitutively activate PLC through Gαq or partially through Gαi [22, 50, 91], while BILF1 cannot activate PLC. In stark contrast to vGPCR and US28, BILF1 apparently doesn't interact with SERCA and fails to activate NFAT signaling [51]. Instead, BILF1 has been extensively linked to immune evasion, distinguishing it from the other viral GPCRs. BILF1 was initially found to inhibit the phosphorylation of PKR. Upon viral infection, double-stranded RNA(dsRNA) binding to PKR leads to its activation [138]. Activated, PKR can phosphorylate the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2A (eIF2A) to inhibit mRNA translation, thereby preventing viral protein synthesis and replication [139]. BILF1 can antagonize the activity of PKR and dampen antiviral response to facilitate viral replication [138]. Furthermore, BILF1 reduces the expression levels of MHC class I by interacting with MHC class I molecules to facilitate their endocytosis and lysosomal degradation, thereby restricting CD8 T cell response. In contrast, vGPCR cannot down-regulate MHC class I. Down-regulation of MHC class I by BILF1 is independent of its constitutive GPCR signaling, becausea BILF1 mutant that is unable to activate G-protein signaling is still capable of down-regulating MHC class I [140]. The cytoplasmic tail of BILF1 is required for the down-regulation of MHC-I [141, 142]. Together, these studies define a viral immune-modulatory function of BILF1 that dysregulates both innate and adaptive immune response.

Recently, a very interesting study shows that COX-driven production of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) by melanoma and other cancer cells helps such cells evade anti-tumor immunity [143]. COX-dependent secretion of PGE2 by melanoma cells is required for tumor growth in immune-competent mice, but not in immune-deficient mice. Inhibition of COX synergized with antibody disruption of programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) to reduce tumor growth in mice. Furthermore, in human patients with melanoma, COX2 expression positively correlated with tumor-promoting inflammatory factors and inversely correlated with antitumor factors, especially the expression of IFN-stimulated genes [143]. COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes, which are critical for the production of PGE2, are often overexpressed in colorectal cancer, among other cancer types [144, 145]. Inhibiting COX2 by treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can reduce the incidence of multiple human cancers. For example, COX2 inhibition can significantly reduce tumor occurrence in patients with mutations in adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) tumor suppressor [102, 146]. It is not surprising that multiple viral GPCRs can also potently induce COX-2 expression. Treatment with an inhibitor of COX-2 delays tumor development induced by US28 in mice [90]. Moreover, US28 expression can promote intestinal neoplasia in a transgenic mouse model by inhibiting GSK-3β and stabilizing β-catenin [147]. KSHV infection, as well as vGPCR expression, can strongly induce COX-2 expression [148, 149]. It is known that US28 and vGPCR can stimulate Gαq and activate PLCβ to up-regulate COX-2 expression [22, 53, 89], while recent studies suggest that US28 and vGPCR can also target SERCA to increase calcium concentration to promote COX-2 expression through NFAT [51]. Because the immune-modulatory function of vGPCR and US28 is poorly studied, it is tempting to speculate that the strong induction of COX-2 and the metabolite PGE2 may modulate host antiviral immune responses in order to facilitate viral replication and dampen antiviral/antitumor immune responses.

6.2. Activation of PI3K-AKT signaling axis

The aberrant activation of PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling represents one of the most frequent events in cancer [150-152], hence the molecular targets of this signaling pathway have been extensively explored to develop cancer therapy [153-155]. Many cellular and viral GPCRs can activate PI3K through Gβγ subunits. For example, vGPCR activates PI3K by stimulating PI3Kγ in a Gαi dependent manner [54]. Thyroid stimulating hormone receptor (TSHR) is one of the most frequently mutated GPCRs in thyroid cancer. Although the signaling network induced by gain-of-function mutations of TSHR is not fully understood, it is believed that the Gβγ-dependent activation of PI3K, in addition to cAMP signaling, contributes to thyroid adenoma development [156]. Smoothened (SMO) is an important component of the Hedgehog signaling pathway and mutations of SMO are often found in sporadic basal-cell carcinoma [157]. Recent sequencing revealed that mutations of SMO arise in the colon and neural systems, among other cancer types [7]. SMO can activate PI3K through Gβγ and block PKA via Gαi, to release the inhibition of the central transcription factor, Gli, in the Hedgehog signaling pathway [158]. As such, SMO potently activates the Hedgehog signaling cascade to promote tumorigenesis. Despite the constitutive activation of PLC through Gαq by US28, US28 cannot activate PI3K [53], suggesting that KSHV vGPCR may rewire a larger signaling network compared with US28. The aberrant activation of PI3K-AKT by viral and mutated cellular GPCRs provides a strong rationale to target this signaling axis for therapeutic intervention.

6.3. Regulation of the Hippo signaling pathway

vGPCR can strongly activate transcription co-activator, yes-associated protein (YAP). YAP/TAZ, oncoproteins that are inhibited by large tumor suppressor (LATS) kinase, are induced in KS tumor tissues and cells undergoing KSHV lytic replication. vGPCR acts mainly through Gαq/11 and Gα12/13 to inhibit the Hippo pathway kinases, thereby promoting the activation of YAP/TAZ. Depletion of YAP with shRNA blocks vGPCR-induced cell proliferation and tumorigenesis in a xenograft mouse model. Furthermore, vGPCR-transformed endothelial cells are sensitive to a YAP specific inhibitor, verteporfin [55, 159]. Gαq/11-Hippo signaling is also involved in many types of cancer, especially uveal melanoma (UM). Gαq or Gα11 mutations are found in more than 80% of UM. Interestingly, all mutations in Gαq or Gα11 occur in a mutually exclusive manner at either arginine 183 (R183) or glutamine 209 (Q209), respectively, suggesting that these mutations in Gαq or Gα11 have similar functions in uveal tumor development [160-162]. These mutations render Gα defective of GTPase activity and lock it in a constitutively active state. Thus, these mutations are considered to be driver mutations in UM. Recent evidence indicate that the Gαq and Gα11 mutations activate the transcriptional coactivator, YAP [163], a critical component of the Hippo signaling pathway that has been extensively studied in controlling tissue homeostasis and organ size [164-166]. The role of aberrant Hippo signaling in cancer development is also under active investigation [167, 168]. GPCRs have been reported to differentially modulate YAP activation. GPCRs coupled to Gα12/13 inhibit the activity of LATS kinase to promote YAP activation, while GPCRs coupled to Gαs promote LATS activation and inhibit YAP activation [169]. Interestingly, the Gαq/11 mutations in UM add another layer of activation of the Hippo pathway by GPCRs. It was found that mutations in Gαq/11 largely activate YAP through a LATS-independent pathway. Specifically, mutated Gαq and Gα11 act through Trio-Rho/Rac signaling to promote actin polymerization [163]. Collectively, previous studies support that actin polymerization can lead to YAP activation [170-172]. Indeed, the expression of Gαq and Gα11 mutants enhance F-actin accumulation and disrupt the angiomotin-YAP complex to release YAP, promoting the nuclear translocation and activation of YAP. Importantly, treatment with a specific YAP inhibitor blocks tumor growth of UM cells harboring Gαq/11 mutations [163, 173]. These studies collectively support the conclusion that YAP represents a therapeutic target for the treatment of UM and other tumors that are driven by GPCRs and gain-of-function mutations in Gαq/11 or Gα12/13.

6.4. Activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling

Deregulation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is frequently found in diverse cancer types [174]. vGPCR activates the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway through PI3K-AKT. Treatment with a PI3K-specific inhibitor blocked the induction of β-catenin-dependent genes [175]. This is reminiscent of PGE2, the main metabolite of COX2, one of the best-studied prostaglandins. The contribution of PGE2 to colorectal cancer and other cancer types has been extensively investigated [144]. PGE2 can stimulate EP1-EP4 receptors to activate β-catenin signaling in human tumors. For example, EP2 receptor couples to Gαs and stimulates the accumulation of cAMP and the activation of PKA. Concomitantly, Gβγ stimulates PI3K-AKT, which functions together with PKA to inhibit the β-catenin degradation complex, stabilize β-catenin and initiate downstream gene expression [176].

On the other hand, HCMV US28 appears to activate β-catenin independent of PI3K-AKT and key components of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway [177]. The coupling to Gαq and Gα12/13 and the activation of Rho-ROCK signaling by US28 are required for β-catenin activation. How Rho-ROCK signaling relays to β-catenin warrants further study. Importantly, transgenic expression of US28 in intestinal epithelial cells promotes intestinal neoplasia in mice. The transgenic expression of US28 inhibits the function of glycogen synthase 3β (GSK-3β) and increases the stability, nuclear translocation and activation of β-catenin [147]. Interestingly, the simultaneously transgenic expression of US28 and its ligand CCL2 increases intestinal epithelial cell proliferation and tumor burden, suggesting that CCL2 may further simulate US28 to promote the activation of β-catenin signaling in vivo [147, 178].

Since both vGPCR and US28 strongly induce COX-2 expression, the production of PGE2 will further enhance β-catenin signaling in vGPCR- or US28-expressing cells, and their neighboring cells. Thus, β-catenin signaling may represent a suitable molecular target to treat human cancers associated with KSHV and HCMV infection.

7. Concluding remarks

Successful pathogens like herpesvirus have co-evolved with the host to generate virus-host interactions that have been perfected over millions of years. GPCRs regulate a broad spectrum of signaling cascades to coordinate key cellular processes and herpesviruses may pirate host GPCRs to benefit their own infection. Studies of these viral GPCRs and signaling circuitries thereof expand our understanding of the functional repertoire of GPCRs and expose key components for therapeutic design to treat human diseases associated with herpesvirus infection. Herpesvirus infection in normal (immune competent) and diseased (immune compromised) hosts represents unique platforms to determine the roles of viral GPCRs in viral infection and pathogenesis. Examination of constitutively active viral GPCRs afford opportunities to define structural determinants of activated GPCRs and unique regulation by ligands in signaling and tumorigenesis. The wide-spread of GPCR and G protein mutations in cancers highlight the oncogenic potential of these proteins. Our knowledge of GPCR structure is expected to guide the search for allosteric modulators that thwart GPCR signaling in human diseases associated with herpesvirus infection and activated GPCR signaling in cancers. To date, our effort has been largely restricted to GPCRs of HCMV, KSHV and EBV. Studies on GPCRs of other human and animal herpesviruses will be crucial to compare and contrast their biophysical and biochemical properties. Our understanding of the well-studied viral GPCRs, including US28, vGPCR and BILF1, has substantially improved in the past two decades. These studies have been primarily conducted outside the context of viral infection, so the next logical step is to investigate the signaling and pathogenesis of viral GPCR in viral infection under normal and diseased conditions. Finally, structure-guided design of pharmacological modulators of viral GPCRs may enable translating our knowledge to clinical applications.

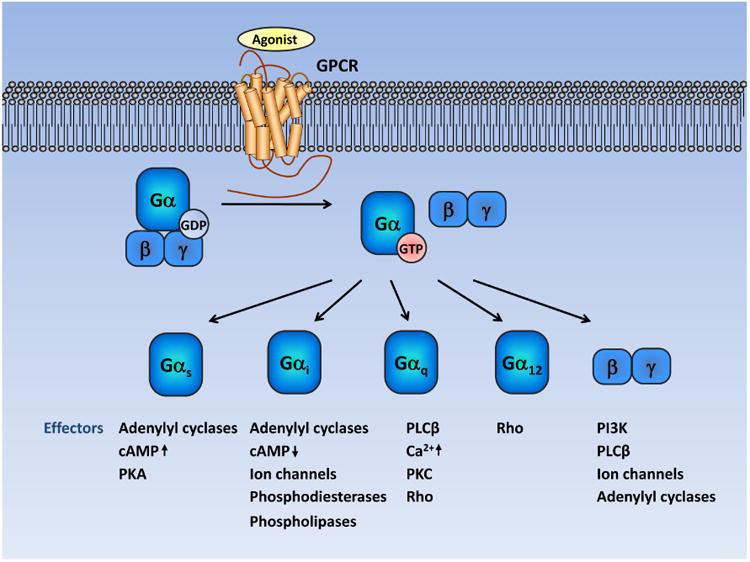

Figure 1. Summary of G-protein-coupled receptor signaling.

Under resting state, GPCRs interact with heterotrimeric G proteins composed of Gα and Gβγ. Agonist stimulation induces a conformational change in GPCR, which catalyzes the exchange of GDP to GTP in the Gα subunit, followed by dissociation of Gα and Gβγ. Gβγ and GTP-bound Gα proteins can then stimulate diverse downstream signaling cascades. Gα proteins can be divided into four families: Gαs, Gαi, Gαq and Gα12. Typically, Gαs activates adenylyl cyclases and increases cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels. The Gαi members inhibit adenylyl cyclases and reduce cAMP levels. When coupled to GPCRs, Gαq activates phospholipase C-β (PLCβ), which eventually leads to increased intracellular calcium concentration and the activation of several protein kinases, such as proteinkinase C (PKC). In contrast, GTP-bound Gα12/13 strongly stimulates the small GTPase Rho by activating guanine nucleotide-exchange factors. Released from Gα, the Gβγ subunit can also trigger various downstream signaling cascades, including PI3K-AKT, PLCβ, adenylyl cyclases and ion channels.

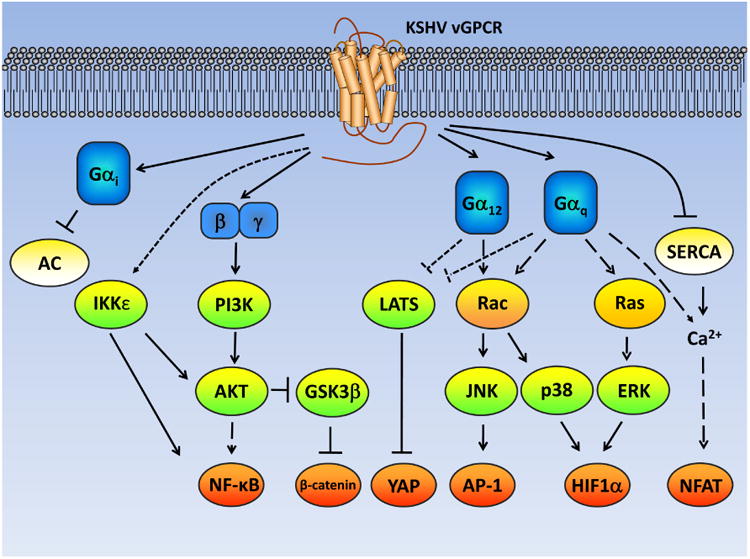

Figure 2. Signaling cascades induced by KSHV vGPCR.

The expression of KSHV vGPCR can induce growth and transformation of endothelial cells by activating multiple signaling cascades. vGPCR activates PI3K through released Gβγ, and in turn induces NF-κB and β-catenin activation. vGPCR also stimulates the activity of IκB kinase epsilon (IKKε) to promote NF-κB activation. Coupling to Gαq and Gα12by vGPCR suppresses the activity of large tumor suppressor kinase (LATS), thereby activating the transcription co-activator yes-associated protein (YAP). Additionally, coupling to Gαq and Gα12 by vGPCR also activates multiple mitogen-activated-protein-kinases (MAPKs), including Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), p38 and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) by stimulating the small GTPases, Rac and Ras. The MAPK signaling cascade leads to the activation of multiple transcription factors, such as activating protein-1 (AP-1), NF-κB and hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF1). Coupling to Gαq by vGPCR increases the intracellular calcium concentration and activates the transcription factor, nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT). Alternatively, vGPCR can directly inhibit the Sarco/Endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase (SERCA) to mobilize calcium influx and activate NFAT. These transcription factors promote the production of pro-angiogenic and pro-inflammatory factors, such as interleukin-8 (IL-8), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and interleukin-6 (IL-6). The secreted factors then activate their respective signaling cascades via autocrine and paracrine mechanisms. (AC: adenylyl cyclase)

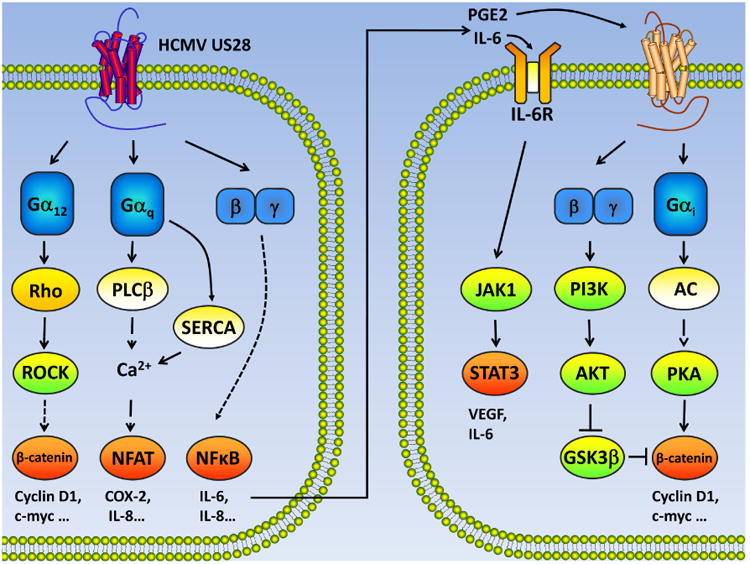

Figure 3. Signaling cascades induced by HCMV US28.

US28 couples to Gα12 family members and activates β-catenin through Rho-ROCK signaling. Concomitantly, US28 coupling to Gαq stimulates PLCβ and increases intracellular calcium concentration, leading to NFAT activation. US28 can directly target SERCA to mobilize calcium signaling and activate NFAT. Released from Gα, the Gβγ subunit promotes NF-κB activation. In the nucleus, these activated transcription factors up-regulate the expression of a large array of proteins that promote cell survival and proliferation. Moreover, IL-6 secreted by US28-expressing cells can activate JAK1-STAT3 in a paracrine manner. The cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) induced by US28 catalyzes the synthesis of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). PGE2 binding to its receptor strongly activates β-catenin signaling by stimulating both PI3K-AKT and adenylyl cyclase (AC)- protein kinase A (PKA) pathways.

Figure 4. The immune regulatory function of EBV BILF1.

BILF1 inhibits the phosphorylation of PKR to dampen antiviral signaling. Additionally, BILF1 directly interacts with MHC class I and promotes the endocytosis and lysosomal degradation of MHC I, which suppresses the antiviral immune response of CD8 T cells.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Jun Zhao for the help with figure preparation. We apologize to those authors whose important work has not been cited due to space constraints. Research of the Feng lab is supported by grants from NIDCR (DE021445, DE026003) and NCI (CA180779, CA134241).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fredriksson R, Lagerstrom MC, Lundin LG, Schioth HB. The G-protein-coupled receptors in the human genome form five main families. Phylogenetic analysis, paralogon groups, and fingerprints. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:1256–72. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.6.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Granier S, Kobilka B. A new era of GPCR structural and chemical biology. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:670–3. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenbaum DM, Rasmussen SG, Kobilka BK. The structure and function of G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature. 2009;459:356–63. doi: 10.1038/nature08144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Magalhaes AC, Dunn H, Ferguson SS. Regulation of GPCR activity, trafficking and localization by GPCR-interacting proteins. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;165:1717–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01552.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rask-Andersen M, Almen MS, Schioth HB. Trends in the exploitation of novel drug targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:579–90. doi: 10.1038/nrd3478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lappano R, Maggiolini M. G protein-coupled receptors: novel targets for drug discovery in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:47–60. doi: 10.1038/nrd3320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Hayre M, Vazquez-Prado J, Kufareva I, Stawiski EW, Handel TM, Seshagiri S, et al. The emerging mutational landscape of G proteins and G-protein-coupled receptors in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:412–24. doi: 10.1038/nrc3521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smit MJ, Vischer HF, Bakker RA, Jongejan A, Timmerman H, Pardo L, et al. Pharmacogenomic and structural analysis of constitutive g protein-coupled receptor activity. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;47:53–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slinger E, Langemeijer E, Siderius M, Vischer HF, Smit MJ. Herpesvirus-encoded GPCRs rewire cellular signaling. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;331:179–84. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.White MK, Gorrill TS, Khalili K. Reciprocal transactivation between HIV-1 and other human viruses. Virology. 2006;352:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jenkins FJ, Rowe DT, Rinaldo CR., Jr Herpesvirus infections in organ transplant recipients. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2003;10:1–7. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.10.1.1-7.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barbieri F, Bajetto A, Florio T. Role of chemokine network in the development and progression of ovarian cancer: a potential novel pharmacological target. J Oncol. 2010:426956. doi: 10.1155/2010/426956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balkwill F. Cancer and the chemokine network. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:540–50. doi: 10.1038/nrc1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vischer HF, Siderius M, Leurs R, Smit MJ. Herpesvirus-encoded GPCRs: neglected players in inflammatory and proliferative diseases? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13:123–39. doi: 10.1038/nrd4189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang Y, Cesarman E, Pessin MS, Lee F, Culpepper J, Knowles DM, et al. Identification of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma. Science. 1994;266:1865–9. doi: 10.1126/science.7997879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cesarman E, Nador RG, Aozasa K, Delsol G, Said JW, Knowles DM. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus in non-AIDS related lymphomas occurring in body cavities. Am J Pathol. 1996;149:53–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dupin N, Fisher C, Kellam P, Ariad S, Tulliez M, Franck N, et al. Distribution of human herpesvirus-8 latently infected cells in Kaposi's sarcoma, multicentric Castleman's disease, and primary effusion lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:4546–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soulier J, Grollet L, Oksenhendler E, Cacoub P, Cazals-Hatem D, Babinet P, et al. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in multicentric Castleman's disease. Blood. 1995;86:1276–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dupin N, Diss TL, Kellam P, Tulliez M, Du MQ, Sicard D, et al. HHV-8 is associated with a plasmablastic variant of Castleman disease that is linked to HHV-8-positive plasmablastic lymphoma. Blood. 2000;95:1406–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mesri EA, Cesarman E, Boshoff C. Kaposi's sarcoma and its associated herpesvirus. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:707–19. doi: 10.1038/nrc2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ganem D. KSHV infection and the pathogenesis of Kaposi's sarcoma. Annu Rev Pathol. 2006;1:273–96. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.1.110304.100133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arvanitakis L, Geras-Raaka E, Varma A, Gershengorn MC, Cesarman E. Human herpesvirus KSHV encodes a constitutively active G-protein-coupled receptor linked to cell proliferation. Nature. 1997;385:347–50. doi: 10.1038/385347a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bais C, Santomasso B, Coso O, Arvanitakis L, Raaka EG, Gutkind JS, et al. G-protein-coupled receptor of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus is a viral oncogene and angiogenesis activator. Nature. 1998;391:86–9. doi: 10.1038/34193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang TY, Chen SC, Leach MW, Manfra D, Homey B, Wiekowski M, et al. Transgenic expression of the chemokine receptor encoded by human herpesvirus 8 induces an angioproliferative disease resembling Kaposi's sarcoma. J Exp Med. 2000;191:445–54. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.3.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo HG, Sadowska M, Reid W, Tschachler E, Hayward G, Reitz M. Kaposi's sarcoma-like tumors in a human herpesvirus 8 ORF74 transgenic mouse. J Virol. 2003;77:2631–9. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.4.2631-2639.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cesarman E, Nador RG, Bai F, Bohenzky RA, Russo JJ, Moore PS, et al. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus contains G protein-coupled receptor and cyclin D homologs which are expressed in Kaposi's sarcoma and malignant lymphoma. J Virol. 1996;70:8218–23. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.8218-8223.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Staskus KA, Zhong W, Gebhard K, Herndier B, Wang H, Renne R, et al. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus gene expression in endothelial (spindle) tumor cells. J Virol. 1997;71:715–9. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.715-719.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boshoff C, Schulz TF, Kennedy MM, Graham AK, Fisher C, Thomas A, et al. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infects endothelial and spindle cells. Nat Med. 1995;1:1274–8. doi: 10.1038/nm1295-1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Montaner S, Sodhi A, Molinolo A, Bugge TH, Sawai ET, He Y, et al. Endothelial infection with KSHV genes in vivo reveals that vGPCR initiates Kaposi's sarcomagenesis and can promote the tumorigenic potential of viral latent genes. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:23–36. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00237-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang J, Zhu L, Lu X, Feldman ER, Keyes LR, Wang Y, et al. Recombinant Murine Gamma Herpesvirus 68 Carrying KSHV G Protein-Coupled Receptor Induces Angiogenic Lesions in Mice. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1005001. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sandford G, Choi YB, Nicholas J. Role of ORF74-encoded viral G protein-coupled receptor in human herpesvirus 8 lytic replication. J Virol. 2009;83:13009–14. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01399-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feng H, Dong X, Negaard A, Feng P. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus K7 induces viral G protein-coupled receptor degradation and reduces its tumorigenicity. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000157. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Y, Lu X, Zhu L, Shen Y, Chengedza S, Feng H, et al. IKK epsilon kinase is crucial for viral G protein-coupled receptor tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:11139–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219829110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liang Y, Ganem D. RBP-J (CSL) is essential for activation of the K14/vGPCR promoter of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus by the lytic switch protein RTA. J Virol. 2004;78:6818–26. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.13.6818-6826.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bottero V, Sharma-Walia N, Kerur N, Paul AG, Sadagopan S, Cannon M, et al. Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpes virus (KSHV) G protein-coupled receptor (vGPCR) activates the ORF50 lytic switch promoter: a potential positive feedback loop for sustained ORF50 gene expression. Virology. 2009;392:34–51. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davis ZH, Verschueren E, Jang GM, Kleffman K, Johnson JR, Park J, et al. Global mapping of herpesvirus-host protein complexes reveals a transcription strategy for late genes. Mol Cell. 2014;57:349–60. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gong D, Wu NC, Xie Y, Feng J, Tong L, Brulois KF, et al. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus ORF18 and ORF30 are essential for late gene expression during lytic replication. J Virol. 2014;88:11369–82. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00793-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brulois K, Wong LY, Lee HR, Sivadas P, Ensser A, Feng P, et al. Association of Kaposi's Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus ORF31 with ORF34 and ORF24 Is Critical for Late Gene Expression. J Virol. 2015;89:6148–54. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00272-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jham BC, Montaner S. The Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus G protein-coupled receptor: Lessons on dysregulated angiogenesis from a viral oncogene. J Cell Biochem. 2010;110:1–9. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Casper C, Wald A. The use of antiviral drugs in the prevention and treatment of Kaposi sarcoma, multicentric Castleman disease and primary effusion lymphoma. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2007;312:289–307. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-34344-8_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rovati GE, Capra V, Neubig RR. The highly conserved DRY motif of class A G protein-coupled receptors: beyond the ground state. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:959–64. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.029470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Verzijl D, Fitzsimons CP, Van Dijk M, Stewart JP, Timmerman H, Smit MJ, et al. Differential activation of murine herpesvirus 68- and Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-encoded ORF74 G protein-coupled receptors by human and murine chemokines. J Virol. 2004;78:3343–51. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.7.3343-3351.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosenkilde MM, Kledal TN, Holst PJ, Schwartz TW. Selective elimination of high constitutive activity or chemokine binding in the human herpesvirus 8 encoded seven transmembrane oncogene ORF74. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:26309–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003800200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ho HH, Ganeshalingam N, Rosenhouse-Dantsker A, Osman R, Gershengorn MC. Charged residues at the intracellular boundary of transmembrane helices 2 and 3 independently affect constitutive activity of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus G protein-coupled receptor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:1376–82. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007885200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Munnik SM, Kooistra AJ, van Offenbeek J, Nijmeijer S, de Graaf C, Smit MJ, et al. The Viral G Protein-Coupled Receptor ORF74 Hijacks beta-Arrestins for Endocytic Trafficking in Response to Human Chemokines. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0124486. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chaisuparat R, Hu J, Jham BC, Knight ZA, Shokat KM, Montaner S. Dual inhibition of PI3Kalpha and mTOR as an alternative treatment for Kaposi's sarcoma. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8361–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Holst PJ, Rosenkilde MM, Manfra D, Chen SC, Wiekowski MT, Holst B, et al. Tumorigenesis induced by the HHV8-encoded chemokine receptor requires ligand modulation of high constitutive activity. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1789–96. doi: 10.1172/JCI13622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Montaner S, Kufareva I, Abagyan R, Gutkind JS. Molecular mechanisms deployed by virally encoded G protein-coupled receptors in human diseases. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;53:331–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010510-100608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Feng H, Sun Z, Farzan MR, Feng P. Sulfotyrosines of the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus G protein-coupled receptor promote tumorigenesis through autocrine activation. J Virol. 2010;84:3351–61. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01939-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McLean KA, Holst PJ, Martini L, Schwartz TW, Rosenkilde MM. Similar activation of signal transduction pathways by the herpesvirus-encoded chemokine receptors US28 and ORF74. Virology. 2004;325:241–51. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang J, He S, Wang Y, Brulois K, Lan K, Jung JU, et al. Herpesviral G protein-coupled receptors activate NFAT to induce tumor formation via inhibiting the SERCA calcium ATPase. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004768. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sodhi A, Montaner S, Patel V, Zohar M, Bais C, Mesri EA, et al. The Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpes virus G protein-coupled receptor up-regulates vascular endothelial growth factor expression and secretion through mitogen-activated protein kinase and p38 pathways acting on hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4873–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smit MJ, Verzijl D, Casarosa P, Navis M, Timmerman H, Leurs R. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-encoded G protein-coupled receptor ORF74 constitutively activates p44/p42 MAPK and Akt via G(i) and phospholipase C-dependent signaling pathways. J Virol. 2002;76:1744–52. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.4.1744-1752.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martin D, Galisteo R, Molinolo AA, Wetzker R, Hirsch E, Gutkind JS. PI3Kgamma mediates kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus vGPCR-induced sarcomagenesis. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:805–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu G, Yu FX, Kim YC, Meng Z, Naipauer J, Looney DJ, et al. Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus promotes tumorigenesis by modulating the Hippo pathway. Oncogene. 2014;34:3536–46. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rosenkilde MM, Kledal TN, Brauner-Osborne H, Schwartz TW. Agonists and inverse agonists for the herpesvirus 8-encoded constitutively active seven-transmembrane oncogene product, ORF-74. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:956–61. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.2.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Geras-Raaka E, Varma A, Clark-Lewis I, Gershengorn MC. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) chemokine vMIP-II and human SDF-1alpha inhibit signaling by KSHV G protein-coupled receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;253:725–7. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Geras-Raaka E, Varma A, Ho H, Clark-Lewis I, Gershengorn MC. Human interferon-gamma-inducible protein 10 (IP-10) inhibits constitutive signaling of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus G protein-coupled receptor. J Exp Med. 1998;188:405–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gershengorn MC, Geras-Raaka E, Varma A, Clark-Lewis I. Chemokines activate Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus G protein-coupled receptor in mammalian cells in culture. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1469–72. doi: 10.1172/JCI4461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cesarman E, Mesri EA, Gershengorn MC. Viral G protein-coupled receptor and Kaposi's sarcoma: a model of paracrine neoplasia? J Exp Med. 2000;191:417–22. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.3.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Couty JP, Geras-Raaka E, Weksler BB, Gershengorn MC. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus G protein-coupled receptor signals through multiple pathways in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:33805–11. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104631200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pati S, Cavrois M, Guo HG, Foulke JS, Jr, Kim J, Feldman RA, et al. Activation of NF-kappaB by the human herpesvirus 8 chemokine receptor ORF74: evidence for a paracrine model of Kaposi's sarcoma pathogenesis. J Virol. 2001;75:8660–73. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.18.8660-8673.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bottero V, Kerur N, Sadagopan S, Patel K, Sharma-Walia N, Chandran B. Phosphorylation and polyubiquitination of transforming growth factor beta-activated kinase 1 are necessary for activation of NF-kappaB by the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus G protein-coupled receptor. J Virol. 2010;85:1980–93. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01911-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Martin D, Galisteo R, Ji Y, Montaner S, Gutkind JS. An NF-kappaB gene expression signature contributes to Kaposi's sarcoma virus vGPCR-induced direct and paracrine neoplasia. Oncogene. 2008;27:1844–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Montaner S, Sodhi A, Servitja JM, Ramsdell AK, Barac A, Sawai ET, et al. The small GTPase Rac1 links the Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus vGPCR to cytokine secretion and paracrine neoplasia. Blood. 2004;104:2903–11. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lawrence T. The nuclear factor NF-kappaB pathway in inflammation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a001651. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Guo JP, Coppola D, Cheng JQ. IKBKE protein activates Akt independent of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/PDK1/mTORC2 and the pleckstrin homology domain to sustain malignant transformation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:37389–98. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.287433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 68.Xie X, Zhang D, Zhao B, Lu MK, You M, Condorelli G, et al. IkappaB kinase epsilon and TANK-binding kinase 1 activate AKT by direct phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:6474–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016132108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Montaner S, Sodhi A, Pece S, Mesri EA, Gutkind JS. The Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus G protein-coupled receptor promotes endothelial cell survival through the activation of Akt/protein kinase B. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2641–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lopez-Ilasaca M, Crespo P, Pellici PG, Gutkind JS, Wetzker R. Linkage of G protein-coupled receptors to the MAPK signaling pathway through PI 3-kinase gamma. Science. 1997;275:394–7. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5298.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sodhi A, Montaner S, Patel V, Gomez-Roman JJ, Li Y, Sausville EA, et al. Akt plays a central role in sarcomagenesis induced by Kaposi's sarcoma herpesvirus-encoded G protein-coupled receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4821–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400835101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jham BC, Ma T, Hu J, Chaisuparat R, Friedman ER, Pandolfi PP, et al. Amplification of the angiogenic signal through the activation of the TSC/mTOR/HIF axis by the KSHV vGPCR in Kaposi's sarcoma. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19103. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ma Q, Cavallin LE, Yan B, Zhu S, Duran EM, Wang H, et al. Antitumorigenesis of antioxidants in a transgenic Rac1 model of Kaposi's sarcoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8683–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812688106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pati S, Foulke JS, Jr, Barabitskaya O, Kim J, Nair BC, Hone D, et al. Human herpesvirus 8-encoded vGPCR activates nuclear factor of activated T cells and collaborates with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat. J Virol. 2003;77:5759–73. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.10.5759-5773.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mancini M, Toker A. NFAT proteins: emerging roles in cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:810–20. doi: 10.1038/nrc2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ryeom S, Baek KH, Rioth MJ, Lynch RC, Zaslavsky A, Birsner A, et al. Targeted deletion of the calcineurin inhibitor DSCR1 suppresses tumor growth. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:420–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cannon M, Philpott NJ, Cesarman E. The Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus G protein-coupled receptor has broad signaling effects in primary effusion lymphoma cells. J Virol. 2003;77:57–67. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.1.57-67.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cannon ML, Cesarman E. The KSHV G protein-coupled receptor signals via multiple pathways to induce transcription factor activation in primary effusion lymphoma cells. Oncogene. 2004;23:514–23. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ma T, Patel H, Babapoor-Farrokhran S, Franklin R, Semenza GL, Sodhi A, et al. KSHV induces aerobic glycolysis and angiogenesis through HIF-1-dependent upregulation of pyruvate kinase 2 in Kaposi's sarcoma. Angiogenesis. 2015;18:477–88. doi: 10.1007/s10456-015-9475-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ma T, Jham BC, Hu J, Friedman ER, Basile JR, Molinolo A, et al. Viral G protein-coupled receptor up-regulates Angiopoietin-like 4 promoting angiogenesis and vascular permeability in Kaposi's sarcoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14363–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001065107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vart RJ, Nikitenko LL, Lagos D, Trotter MW, Cannon M, Bourboulia D, et al. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-encoded interleukin-6 and G-protein-coupled receptor regulate angiopoietin-2 expression in lymphatic endothelial cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4042–51. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gandhi MK, Khanna R. Human cytomegalovirus: clinical aspects, immune regulation, and emerging treatments. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4:725–38. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01202-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vischer HF, Leurs R, Smit MJ. HCMV-encoded G-protein-coupled receptors as constitutively active modulators of cellular signaling networks. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Casarosa P, Bakker RA, Verzijl D, Navis M, Timmerman H, Leurs R, et al. Constitutive signaling of the human cytomegalovirus-encoded chemokine receptor US28. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:1133–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008965200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Waldhoer M, Kledal TN, Farrell H, Schwartz TW. Murine cytomegalovirus (CMV) M33 and human CMV US28 receptors exhibit similar constitutive signaling activities. J Virol. 2002;76:8161–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.16.8161-8168.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Melnychuk RM, Streblow DN, Smith PP, Hirsch AJ, Pancheva D, Nelson JA. Human cytomegalovirus-encoded G protein-coupled receptor US28 mediates smooth muscle cell migration through Galpha12. J Virol. 2004;78:8382–91. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.15.8382-8391.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Streblow DN, Vomaske J, Smith P, Melnychuk R, Hall L, Pancheva D, et al. Human cytomegalovirus chemokine receptor US28-induced smooth muscle cell migration is mediated by focal adhesion kinase and Src. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:50456–65. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307936200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Streblow DN, Soderberg-Naucler C, Vieira J, Smith P, Wakabayashi E, Ruchti F, et al. The human cytomegalovirus chemokine receptor US28 mediates vascular smooth muscle cell migration. Cell. 1999;99:511–20. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81539-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Maussang D, Verzijl D, van Walsum M, Leurs R, Holl J, Pleskoff O, et al. Human cytomegalovirus-encoded chemokine receptor US28 promotes tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:13068–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604433103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Maussang D, Langemeijer E, Fitzsimons CP, Stigter-van Walsum M, Dijkman R, Borg MK, et al. The human cytomegalovirus-encoded chemokine receptor US28 promotes angiogenesis and tumor formation via cyclooxygenase-2. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2861–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Miller WE, Zagorski WA, Brenneman JD, Avery D, Miller JL, O'Connor CM. US28 is a potent activator of phospholipase C during HCMV infection of clinically relevant target cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50524. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Soroceanu L, Matlaf L, Bezrookove V, Harkins L, Martinez R, Greene M, et al. Human cytomegalovirus US28 found in glioblastoma promotes an invasive and angiogenic phenotype. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6643–53. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Harkins L, Volk AL, Samanta M, Mikolaenko I, Britt WJ, Bland KI, et al. Specific localisation of human cytomegalovirus nucleic acids and proteins in human colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2002;360:1557–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11524-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Soderberg-Naucler C, Rahbar A, Stragliotto G. Survival in patients with glioblastoma receiving valganciclovir. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:985–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1302145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bhattacharjee B, Renzette N, Kowalik TF. Genetic analysis of cytomegalovirus in malignant gliomas. J Virol. 2012;86:6815–24. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00015-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Soroceanu L, Matlaf L, Bezrookove V, Harkins L, Martinez R, Greene M, et al. Human cytomegalovirus US28 found in glioblastoma promotes an invasive and angiogenic phenotype. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6643–53. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Slinger E, Maussang D, Schreiber A, Siderius M, Rahbar A, Fraile-Ramos A, et al. HCMV-encoded chemokine receptor US28 mediates proliferative signaling through the IL-6-STAT3 axis. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra58. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Baryawno N, Rahbar A, Wolmer-Solberg N, Taher C, Odeberg J, Darabi A, et al. Detection of human cytomegalovirus in medulloblastomas reveals a potential therapeutic target. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4043–55. doi: 10.1172/JCI57147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Siveen KS, Sikka S, Surana R, Dai X, Zhang J, Kumar AP, et al. Targeting the STAT3 signaling pathway in cancer: role of synthetic and natural inhibitors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1845:136–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yu H, Lee H, Herrmann A, Buettner R, Jove R. Revisiting STAT3 signalling in cancer: new and unexpected biological functions. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:736–46. doi: 10.1038/nrc3818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chen HP, Jiang JK, Chen CY, Chou TY, Chen YC, Chang YT, et al. Human cytomegalovirus preferentially infects the neoplastic epithelium of colorectal cancer: a quantitative and histological analysis. J Clin Virol. 2012;54:240–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Brown JR, DuBois RN. COX-2: a molecular target for colorectal cancer prevention. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2840–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Casarosa P, Menge WM, Minisini R, Otto C, van Heteren J, Jongejan A, et al. Identification of the first nonpeptidergic inverse agonist for a constitutively active viral-encoded G protein-coupled receptor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:5172–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210033200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hulshof JW, Casarosa P, Menge WM, Kuusisto LM, van der Goot H, Smit MJ, et al. Synthesis and structure-activity relationship of the first nonpeptidergic inverse agonists for the human cytomegalovirus encoded chemokine receptor US28. J Med Chem. 2005;48:6461–71. doi: 10.1021/jm050418d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]