Abstract

Background

Parents of children with cancer desire information about late effects of treatment. We assessed parents’ preparedness for late effects at least 5 years after their child's diagnosis.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of all eligible parents of children with cancer between April 2004 and September 2005 at Dana-Farber/Boston Children's Cancer and Blood Disorders Center within a year of diagnosis, and administered a follow-up questionnaire at least 5 years later.

Results

66% of parents of children who were still living, and whom we were able to contact, completed the follow-up questionnaire (n=91/138). 77% (70/91) of respondents were parents of disease-free survivors; 23% (21/91) were parents of children with relapsed disease. Most parents felt well prepared for their child's oncology treatment (87%), but fewer felt prepared for future limitations experienced by their children (70%, p=0.003, McNemar's test) or for life after cancer (62%, p<0.001). In bivariable analysis among parents of disease-free survivors, parents were more likely to feel prepared for future limitations when they also reported that communication with the oncologist helped address worries about the future (OR 4.50, p=0.01). At diagnosis, both parents and physicians underestimated a child's risk of future limitations; 45% of parents and 39% of clinicians predicted future limitations in physical abilities, intelligence or quality of life, but more than 5 years later 72% of children experienced limitations in at least one domain.

Conclusions

Parents feel less prepared for survivorship than for treatment. High-quality communication may help parents feel more prepared for life after cancer therapy.

Keywords: child, parents, neoplasms, health communication, survivors, prognosis

Introduction

Nearly 80% of children with cancer will become long-term survivors.1 However, cancer and its treatments can cause late effects on health and quality of life (QOL) beyond treatment. More than 60% of childhood cancer survivors experience at least one chronic late effect of treatment, and over a quarter experience a severe or life-threatening chronic health condition.2 Studies have shown that parents would like additional information about late effects of treatment.3, 4 However, late effects are discussed far less than acute effects in initial discussions about treatment.5 Whereas parents report receiving high quality information about diagnosis and treatment, parents feel they receive lower quality information about what their child's diagnosis means for the future,6 and there is discordance between parental and clinician expectations for late effects.7 Late effects-related uncertainty causes substantial parental distress.8, 9

To make informed decisions about treatment, parents of children with cancer require accurate information about not only prognosis and acute effects of therapy, but also about potential late effects of treatment. In this study, we sought to evaluate how physician communication impacts parental preparedness for late effects and long-term QOL in children with malignancies. We previously interviewed parents of children with cancer within a year of diagnosis in order to assess medical communication.6, 7, 10 In this follow-up study, we interviewed the same group of parents at least five years after diagnosis in order to evaluate parental feelings of preparedness for child health outcomes after treatment for pediatric cancer. We also evaluated the extent to which initial parent and physician predictions of the risk of late effects matched actual experiences in survivorship.

Methods

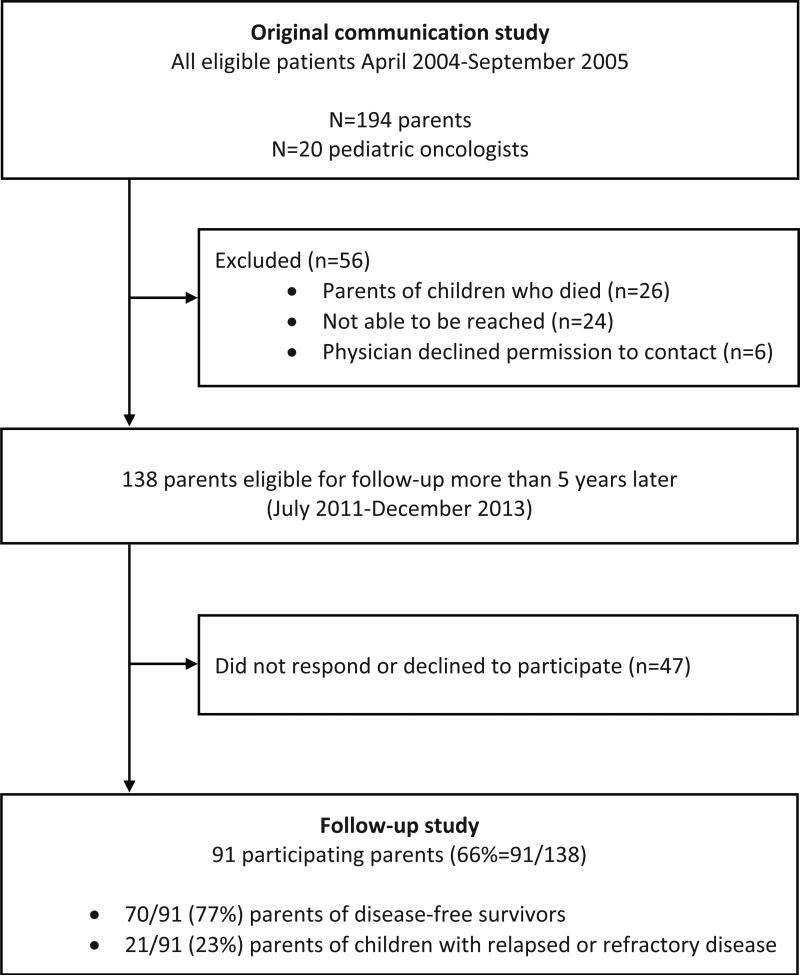

We interviewed parents of children treated for cancer at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute/Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, who had previously participated in a study about medical communication. In the original study, parents and physicians of 194 children with cancer were surveyed between 30 days and 1 year after diagnosis (Figure 1). . The original questionnaire focused on communication about prognosis and long-term complications of cancer therapy.6, 7, 10

Figure 1.

Study Participants: selection of analytic cohort

For the current study, we contacted the same group of parents at least 5 years after the initial survey. Study participants were mailed a letter inviting them to participate and a postcard to return if they declined participation. In-person or telephone interviews were arranged with parents who agreed to participate. Trained interviewers read aloud the study questionnaire question by question along with response options.

Parents of children who died (n=26) were excluded from this analysis given its focus on late effects and long-term outcomes. However, in order to fully capture the spectrum of communication needs and preferences, parents of all long-term survivors were included, both those with children with relapsed disease as well as disease-free survivors (Figure 1). In order to better understand their different experiences, separate though analogous questionnaires were administered to each group. The majority of items were the same in both questionnaires, however only the questionnaire for parents of disease-free survivors included items about the child's current state of health and life after cancer treatment. Parents of children with relapse, who might be on continued cancer therapy, may not be able to speak to life after cancer, and the child's current health state may reflect current therapy more than late effects of initial therapy. Questionnaires utilized items or modified items drawn from our previously developed questionnaire,6, 7, 10 with select new questions devised based on literature review and general principles of survey design.

Study Outcomes

Parental preparedness for cancer care and late effects:

The primary study outcome was parental feelings of preparedness for late effects and long-term QOL. Parents were asked how well information from the oncologist prepared them for, and the importance of receiving information about, “experiences with your child's treatment,” “day-to-day care of your child during cancer treatment,” “the chances that your child would be cured of cancer,” and “the possibility that your child would have future limitations after treatment was finished.” Response options were “extremely,” “very,” “somewhat,” “a little,” and “not at all.” Parents of disease-free survivors were also asked about their preparedness and information preferences for “life after your child's cancer treatment.”

We evaluated factors we hypothesized may affect parental feelings of preparedness including:

-

Patient Attributes:

Diagnosis, date of diagnosis, disease status (disease-free versus active disease/relapse), and date of birth were obtained by medical record review. Diagnosis and disease status were confirmed by the oncologist. Child's current state of health and limitations was determined by parental report and only asked of disease-free survivors.

-

Parent Characteristics:

Parents’ preferred and actual decision-making roles were evaluated using an ordinal scale developed by Degner and Sloan.11 Parental anxiety and depression were assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.12, 13 Parents’ sex, age, educational level, and race/ethnicity were obtained by questionnaire.

-

Parent communication experiences:

In the first year after diagnosis, parents had been asked to report the quality of information received about “what your child's diagnosis means for the future” with responses of excellent/good/satisfactory/fair/poor. In the follow-up questionnaire more than 5 years later, parents of disease-free survivors were asked how communication with the oncologist helped them “deal with worries about the future” with responses of a great deal/somewhat/a little/not at all.

Predicted and experienced limitations due to cancer treatment:

A secondary outcome was parent report of functional limitations experienced by their child as a result of cancer treatment and concordance of predictions in the first year after diagnosis with actual experiences more than 5 years later; this was only assessed among parents of disease-free survivors. In the original survey conducted within a year of diagnosis, parents and physicians were asked to predict the likelihood of a child experiencing functional limitations as a result of cancer treatment in three domains: “physical abilities (such as difficulty exercising),” “intelligence (such as difficulty with schoolwork),” and “quality of life (such as difficulty enjoying time with family or friends).” Response options included “extremely likely (>90%),” “very likely (75-90%),” “moderately likely (50-74%),” “somewhat likely (25-49%),” “unlikely (10-24%),” and “very unlikely (<10%).” In the current questionnaire, parents of disease-free survivors were asked whether their child experienced limitations in these same domains with response options “not at all,” “a little,” “some extent,” “a moderate extent,” or “a great deal.” Parent report of impairment was chosen over alternative methods such as medical record review in order to best capture the functional impact of limitations. Parents were also asked to rate their child's current overall state of health as excellent/very good/good/fair/poor.

Statistical Methods

Participant characteristics and responses to items about preparedness for information, importance of information, and perceptions of current limitations were summarized descriptively. After dichotomizing responses for preparedness as extremely/very prepared versus not at all/a little/somewhat prepared consistent with our prior work,6 and based on our clinical impression of optimal preparation, McNemar's test was used to compare whether parents reported that they were more prepared for treatment versus chances of cure, day-to-day care, future limitations, or life after cancer. Bivariable logistic regression was used to investigate factors associated with parental feelings of greater preparedness for future limitations. Parallel analyses were conducted for the outcome of greater preparedness for life after cancer, which was asked only of disease-free patient families. Multivariable modeling was not attempted due to the low number of parents who reported being less prepared for these outcomes.

To compare initial perception of risk of late effects at the time of diagnosis with late effects experienced at least 5 years later, parent and physician predictions of likelihood of future limitations from the original study were dichotomized as unlikely (very unlikely/unlikely) versus likely (somewhat to extremely likely). Experience of limitations was dichotomized as none (not at all) versus any limitations (a great deal/moderate/some/a little). Predictions were considered accurate if a parent or physician predicted at diagnosis that it was unlikely for a child to have limitations in a domain, and the child had no limitations in that domain at least 5 years later. Accurate predictions also included those in which a parent or physician predicted it was likely that a child would have a future limitation, and the child went on to have limitations in the same domain. Predictions were deemed inaccurate if there was a discrepancy between predicted and experienced limitations. Parent report of quality of information received at diagnosis about “what your child's diagnosis means for the future” was dichotomized as high quality (excellent/good) versus lower quality (satisfactory/fair/poor).6 Fisher's exact test was used to compare parent reports of likelihood of future limitations and quality of communication between the original study at the time of diagnosis, to parent responses of perceived limitations and accuracy of predictions 5 years later. Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station TX).

Results

Of the 138 families approached, 91 participated, for an overall response rate of 66% (Figure 1). 21/91 were parents of children with relapsed or refractory disease, and 70/91 were parents of disease-free survivors. The majority of parent respondents were female, white and well educated (Table 1). The median time from diagnosis to survey completion was 7.9 years (range 6.5-10.9).

Table 1.

Parent and Patient Characteristics, N=91

| Parent Characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gender | N | % |

| Female | 75 | 82 |

| Age at survey completion | N | % |

| 21-39 | 21 | 23 |

| ≥40 | 70 | 77 |

| Race/Ethnicity | N | % |

| White, non-Hispanic | 81 | 89 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 2 | 2 |

| Hispanic | 6 | 7 |

| Asian or Other | 2 | 2 |

| Highest level of education completed | N | % |

| High school graduate or less | 12 | 13 |

| Some college or technical school | 15 | 16 |

| College graduate or higher | 64 | 70 |

| Child Characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gender | N | % |

| Female | 48 | 53 |

| Age at diagnosis | ||

| Median, range | 4 | 0-17 |

| Cancer diagnosis | N | % |

| Hematologic malignancy | 58 | 64 |

| Brain tumor | 16 | 17 |

| Other solid tumor | 17 | 19 |

| Years since diagnosis* | ||

| Median, range | 7.9 | 6.5-10.5 |

| Current disease state | N | % |

| Disease-free survivor | 70 | 77 |

| Active disease/relapse | 21 | 23 |

From diagnosis through survey completion

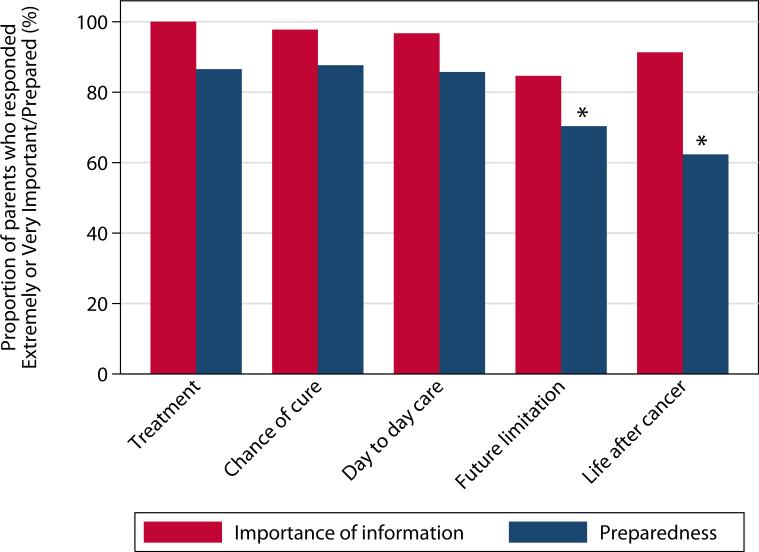

The majority of parents felt that it was extremely or very important to receive information about treatment (100%=90/90), day-to-day care of their child during treatment (97%=88/91), chance of cure (98%=87/89), the possibility of future limitations (85%=77/91), and life after cancer treatment (91%=63/69) (Figure 2). Most parents also felt that information from the oncologist prepared them extremely or very well for treatment (87%=77/89), day-to-day care during treatment (86%=78/91), and chances of cure (88%=78/89). However, in comparison to preparation for treatment, fewer parents reported feeling prepared for future limitations experienced by their children (p=0.003) with only 70% (64/91) feeling extremely or very prepared. Similarly, parents of disease-free survivors reported feeling less prepared for life after cancer with only 62% (43/69) feeling well prepared (p<0.001).

Figure 2.

Parent perceptions of importance of information and preparedness: percent of parents who felt information about this topic was extremely/very important, and percent who felt extremely/very prepared. N ranges from 89-91 for all items except for 'life after cancer,' which was only asked of parents of disease-free survivors (n=69).

Legend: * P<0.05 by McNemar's Test comparing preparedness for each item with preparedness for treatment. Parents were significantly less prepared for future limitations (p=0.003) and for life after cancer (p<0.001) than for treatment.

Factors associated with parental feelings of preparedness for future limitations in bivariable analyses are shown in Table 2. Parents were more likely to report feeling extremely or very prepared for future limitations if they also reported that their child had no limitations in intelligence (OR 3.60, p=0.02) or QOL (OR 3.60, p=0.02). Parents who reported receiving high quality information about what their child's diagnosis meant for the future at the time of diagnosis were more likely to report feeling prepared for future limitations in survivorship (OR 5.19, p=0.001). Similarly, at least 5 years later, parents who felt that communication with the oncologist helped them deal with worries about the future were more likely to feel prepared for future limitations (OR 4.50, p=0.01). Relative to parents who preferred to hold an active role in decision-making, parents who preferred a collaborative (OR 0.47) or passive role (OR 0.22) were less likely to report feeling prepared for future limitations (p=0.05). Child's oncology diagnosis, child's current disease state (disease-free vs. relapsed), parental anxiety and depression were not significantly associated with feelings of preparedness for future limitations.

Table 2.

Bivariate analysis of associations with parental feelings of preparedness for future limitations and life after treatment (extremely/very well prepared)‡

| Future limitations | Life after cancer* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % extremely or very well prepared | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P Value | % extremely or very well prepared | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P Value | |

| Overall | 70 | 63 | ||||||

| Child cancer diagnosis | 0.89 | 0.26 | ||||||

| Hematologic malignancy | 69 | 1.00 | 60 | 1.00 | ||||

| Brain tumor | 75 | 1.35 | 0.38-4.76 | 82 | 2.95 | 0.57-15.2 | ||

| Other solid tumor | 71 | 1.08 | 0.33-3.52 | 50 | 0.66 | 0.17-2.57 | ||

| Current disease state | ||||||||

| Disease-free survivor | 69 | 1.00 | 62 | |||||

| Active disease/relapse | 76 | 1.47 | 0.48-4.51 | 0.50 | -- | |||

| Current overall state of health* | ||||||||

| Not excellent | 58 | 1.00 | 55 | 1.00 | ||||

| Excellent | 76 | 2.33 | 0.83-6.54 | 0.11 | 68 | 1.78 | 0.67-4.77 | 0.25 |

| Limitations in physical abilities* | ||||||||

| Some | 59 | 1.00 | 56 | 1.00 | ||||

| None | 76 | 2.13 | 0.76-5.96 | 0.15 | 68 | 1.62 | 0.61-4.32 | 0.33 |

| Limitations in intelligence* | ||||||||

| Some | 56 | 1.00 | 53 | 1.00 | ||||

| None | 82 | 3.60 | 1.20-10.8 | 0.02 | 73 | 2.39 | 0.87-6.53 | 0.09 |

| Limitations in QOL* | ||||||||

| Some | 48 | 1.00 | 43 | 1.00 | ||||

| None | 77 | 3.60 | 1.21-10.7 | 0.02 | 70 | 3.14 | 1.08-9.13 | 0.04 |

| Preferred decision making role* | 0.051† | 0.12† | ||||||

| Active | 82 | 1.00 | 82 | 1.00 | ||||

| Collaborative | 68 | 0.47 | 0.09-2.47 | 62 | 0.36 | 0.07-1.85 | ||

| Passive | 50 | 0.22 | 0.03-1.59 | 40 | 0.15 | 0.02-1.08 | ||

| Communication helped deal with worries about the future* | ||||||||

| Not at all or a little | 40 | 1.00 | 33 | 1.00 | ||||

| Somewhat or a great deal | 75 | 4.50 | 1.34-15.1 | 0.01 | 71 | 4.93 | 1.44-16.9 | 0.01 |

| Quality of information about what child's diagnosis meant for the futureΔ | ||||||||

| Poor, Fair, or Satisfactory | 47 | 1.00 | 42 | |||||

| Good or Excellent | 82 | 5.19 | 1.97- 13.7 | 0.001 | 73 | 3.85 | 1.35-11.0 | 0.01 |

No statistically significant associations were found between preparedness for future limitations or life after cancer and parent age, parent gender, parent education, race/ethnicity, child age, child gender, parental anxiety, or parental depression.

Only asked of disease-free patient families

Test for trend across ordered categories

Asked in the original questionnaire, within a year of diagnosis

Only parents of disease-free survivors were asked about feelings of preparedness for life after treatment; associated factors are shown in Table 2 (bivariable relationships). Again, parents who reported receiving high quality information about what their child's diagnosis meant for the future when asked within a year of diagnosis (OR 3.85, p=0.01), and parents who reported that communication with the oncologist helped them deal with worries about the future at least 5 years later (OR 4.93, p=0.01) were more likely to feel prepared for life after cancer. Child's oncology diagnosis, parent preferred decision-making role, anxiety, and depression were not significantly associated with feelings of preparedness for life after cancer.

Predicted and experienced limitations due to cancer treatment

We compared parents’ and physicians’ predictions of future limitations in physical function, intellectual function, and QOL from the original study obtained in the first year after diagnosis, with parent report of limitations actually experienced at least 5 years later. When surveyed in the first year after diagnosis, 27% (18/67) of parents and 16% (11/67) of physicians anticipated that the child was likely to have limitations in physical abilities. 32% (21/66) of parents and 26% (17/66) of physicians predicted future limitations in intelligence, and 16% (11/67) of parents and 10% (7/67) of physicians predicted limitations in QOL (Table 3). More than 5 years later, 72% (46/64) of parents of disease-free survivors reported that their child had a limitation in at least one domain, with 45% of parents (30/67) reporting physical limitations, and nearly half (48%=32/66) reporting limitations in intelligence. Despite limitations, a majority of parents considered their child's current state of overall health to be “excellent” or “very good” (88%=61/69), and 70% (47/67) of parents reported no limitations in QOL compared with what would be expected if their child had not had cancer. Parents’ predictions at baseline were not significantly associated with their reports of actual limitations more than 5 years later in any domain: physical abilities (OR 1.81, p=0.41), intelligence (OR 1.86, p=0.30), or QOL (OR 3.6, p=0.07). Additionally, receipt of high quality information about the future was not significantly associated with increased parental accuracy of predictions for limitations: physical abilities (OR 2.51, p=0.12), intelligence (OR 0.94, p=1), or QOL (OR 2.99, p=0.08).

Table 3.

Relationship between parent and physician predictions of late effects at diagnosis and experience of late effects at least 5 years later.

| Number of patients* | Parent prediction at diagnosis | Physician prediction at diagnosis | Parents reporting child limitations ≥ 5 years later | Parents with accurate predictions† | Physicians with accurate predictions† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Limitations in physical abilities | 67 | 18 (27) | 11 (16) | 30 (45) | 39 (58) | 42 (63) |

| Limitations in intelligence | 66 | 21 (32) | 17 (26) | 32 (48) | 37 (56) | 37 (56) |

| Limitations in QOL | 67 | 11 (16) | 7 (10) | 20 (30) | 48 (72) | 48 (72) |

| Limitations in any domain | 64 | 29 (45) | 25 (39) | 46 (72) |

Number of patients with both parent and physician predictions at diagnosis, as well as parent estimates at least 5 years later. By study design, this sample only includes disease-free patient families.

Accuracy defined as parent or physician prediction at diagnosis matched limitations experienced by child at least 5 years later.

Discussion

We evaluated physician-parent communication about late effects of pediatric cancer therapy, and parent expectations and preparedness for future limitations. Results of our study suggest that many parents feel less prepared for the possibility of their child experiencing future limitations, or for their child's life after cancer, than they do for acute effects of treatment. However, high-quality communication and provision of information are associated with greater feelings of preparedness for life after treatment for pediatric malignancies. These findings are consistent with studies which showed that late effects of treatment are discussed far less frequently than acute affects of therapy in initial diagnosis and treatment discussions,5 and that both survivors and parents desire additional information about late effects.4, 14, 15 Our findings support candid discussions between physicians and families about possible late effects of pediatric cancer treatment.

We also evaluated parent and physician predictions of likelihood of late effects and parent reports of actual late effects experienced. Both parents and providers underestimate the risk of a child experiencing limitations in physical abilities, intelligence or QOL as a result of cancer treatment. The underestimation of late effects by parents is even more striking given that compared with physicians, parents were initially more optimistic about survival and more pessimistic about late effects.7 Additional information and discussions about late effect risk could improve parental knowledge and preparedness for future limitations, but this is contingent upon providers recognizing the risks. Providers may underestimate risks due to a focus on acute effects of treatment and rates of cure, lesser exposure to survivorship care, or unrealistic prognostic estimations. Studies of prognostic accuracy have shown that oncologists tend to be overly optimistic when estimating how long a patient has to live,16, 17 and delayed in recognizing when a child has no realistic chance of cure.18, 19 Physicians may be similarly optimistic in predicting late effects or functional outcomes. Additionally, given that we can't know which patients will develop late effects, but only which have a greater probability of doing so, perhaps helping to prepare parents for the possibility of late effects is more important than improving the accuracy of predictions. Targeted interventions with providers to encourage additional communication about late-effects and survivorship throughout therapy may increase both provider and parental awareness of risk.

How and when to best provide information about late effects and survivorship requires further investigation. Prior studies have shown a wide array of parental preferences for information about late effects of treatment. In one study, a third of parents preferred this information at the time of diagnosis, but the other two thirds preferred this information during treatment or in long-term follow-up care.3 Similarly, parents prefer to receive this information in a variety of modalities including verbal, written, video and online.3, 4, 15 Given variable preferences, we recommend assessing information needs throughout therapy, and offering information per family need and at key time points such as diagnosis, completion of therapy, and entry into survivorship clinic. While attendance in survivorship clinic is associated with increased knowledge about late effects,20 and the lived experience of late effects may contribute to parent knowledge and feelings of preparedness, some families may benefit from receiving information about late effects earlier in treatment as it could impact treatment choices. Better understanding of prognosis,21 and the functional outcomes22 associated with treatment choices impact adult patient decisions. It is possible that earlier and more comprehensive discussions about late effects of cancer will affect both parental feelings of preparation for these effects and treatment decisions.

There are several potential limitations to this study. It was conducted at a single pediatric oncology center, and the parent population may not be representative of parents nationwide. However, many children with pediatric malignancies are treated at large cancer centers similar to our institution. We also interviewed parents of children with a wide variety of malignancies, and there may be differences in informational needs and risks of late effects between cancer types. However, the rarity of pediatric cancers necessitated this broad representation of malignancies, and querying information needs across a variety of cancers may better capture the scope of parent preferences. Similarly, some parents could not be reached, or the physician requested that we not contact them; these children and families may have had worse health or communication outcomes. Given the diversity of patients included, we defined late effects quite broadly, with a focus on functional limitations, rather than asking about specific medical sequellae of pediatric cancer therapy; in doing so, we hoped to identify those issues most salient to families. We also relied on parent and physician perspectives on QOL, but do not fully understand how parents and physicians define QOL. Finally, our sample size was inadequate to allow multivariable analysis and offered limited power to detect differences based on child diagnosis, parent depression, or desired decision-making role.

Parents were asked to reflect on their feelings of preparedness based on conversations they may have had years prior to questionnaire administration. It is possible that providers addressed many late effects in early conversations, but that parents did not recall this information due to time elapsed, stress, or the number of critical topics being discussed.23 However, inability to recall information may suggest that providers should modify communication practices. In addition, as is standard in many studies of decision-making for pediatric patients, this study was conducted with parents regardless of the child's age, as parents are the primary medical decision-makers for their children. However, parental choices and parental perceptions of limitations may not always align with their children's,24 and many pediatric patients are teens or young adults by the time they are most affected by late effects of treatment. The informational needs and desires of patients themselves, and the appropriate age and time to include pediatric patients in discussions about late effects and long-term outcomes were not explored in this study, but should be further investigated. Strengths of this study include the opportunity to longitudinally track parent expectations from the year of diagnosis to many years after completion of therapy, and to compare parent and provider expectations with actual patient outcomes.

In this study, parents and physicians underestimated children's risks of late effects of cancer therapy. Given the discrepancy between parent expectations of late effects, and children's experiences of late effects, it is not surprising that parents felt unprepared for their child's life after cancer treatment. High quality communication between providers and parents at diagnosis and throughout therapy may enhance preparedness for survivorship. To make informed decisions about treatment, parents require accurate information about overall chance of cure, and about the likelihoods and impact of potential late effects of cancer treatments. Providers must reconsider how and when to discuss potential late effects and functional outcomes after pediatric cancer therapy in order to meet parental information desires, and to engage in true shared decision-making.

Precis.

Parents of children with cancer feel prepared to manage their child's cancer treatment, but they feel less prepared for survivorship. High quality communication with providers may help parents feel more prepared for their child's life after cancer therapy.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This work has been supported by NIH training grant T32 CA136432 (KAG) and a St. Baldrick's Foundation Supportive Care Research Grant (JWM).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

Author Contributions:

Conception and Design: JWM, KAG

Collection and assembly of data: JWM

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

References

- 1.Ward E, DeSantis C, Robbins A, Kohler B, Jemal A. Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:83–103. doi: 10.3322/caac.21219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1572–1582. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa060185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trask CL, Welch JJ, Manley P, Jelalian E, Schwartz CL. Parental needs for information related to neurocognitive late effects from pediatric cancer and its treatment. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;52:273–279. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vetsch J, Rueegg CS, Gianinazzi ME, et al. Information needs in parents of long-term childhood cancer survivors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:859–866. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramirez LY, Huestis SE, Yap TY, Zyzanski S, Drotar D, Kodish E. Potential chemotherapy side effects: what do oncologists tell parents? Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;52:497–502. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaye E, Mack JW. Parent perceptions of the quality of information received about a child's cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:1896–1901. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mack JW, Cook EF, Wolfe J, Grier HE, Cleary PD, Weeks JC. Understanding of prognosis among parents of children with cancer: parental optimism and the parent-physician interaction. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1357–1362. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.3170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boman K, Lindahl A, Bjork O. Disease-related distress in parents of children with cancer at various stages after the time of diagnosis. Acta Oncol. 2003;42:137–146. doi: 10.1080/02841860310004995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoven E, Anclair M, Samuelsson U, Kogner P, Boman KK. The influence of pediatric cancer diagnosis and illness complication factors on parental distress. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2008;30:807–814. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31818a9553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mack JW, Wolfe J, Grier HE, Cleary PD, Weeks JC. Communication about prognosis between parents and physicians of children with cancer: parent preferences and the impact of prognostic information. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5265–5270. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Degner LF, Sloan JA. Decision making during serious illness: what role do patients really want to play? J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:941–950. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gianinazzi ME, Essig S, Rueegg CS, et al. Information provision and information needs in adult survivors of childhood cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61:312–318. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wakefield CE, Butow P, Fleming CA, Daniel G, Cohn RJ. Family information needs at childhood cancer treatment completion. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58:621–626. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christakis NA, Lamont EB. Extent and determinants of error in doctors' prognoses in terminally ill patients: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2000;320:469–472. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7233.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wusthoff CJ, McMillan A, Ablin AR. Differences in pediatric oncologists' estimates of curability and treatment recommendations for patients with advanced cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;44:174–181. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenberg AR, Orellana L, Kang TI, et al. Differences in parent-provider concordance regarding prognosis and goals of care among children with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3005–3011. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.4659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ullrich CK, Dussel V, Hilden JM, Sheaffer JW, Lehmann L, Wolfe J. End-of-life experience of children undergoing stem cell transplantation for malignancy: parent and provider perspectives and patterns of care. Blood. 2010;115:3879–3885. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-250225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindell RB, Koh SJ, Alvarez JM, et al. Knowledge of diagnosis, treatment history, and risk of late effects among childhood cancer survivors and parents: The impact of a survivorship clinic. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:1444–1451. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mack JW, Cronin A, Keating NL, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussion characteristics and care received near death: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4387–4395. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.6055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fried TR, Bradley EH, Towle VR, Allore H. Understanding the treatment preferences of seriously ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1061–1066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levi RB, Marsick R, Drotar D, Kodish ED. Diagnosis, disclosure, and informed consent: learning from parents of children with cancer. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2000;22:3–12. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200001000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janse AJ, Sinnema G, Uiterwaal CS, Kimpen JL, Gemke RJ. Quality of life in chronic illness: children, parents and paediatricians have different, but stable perceptions. Acta Paediatr. 2008;97:1118–1124. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.00847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]