Abstract

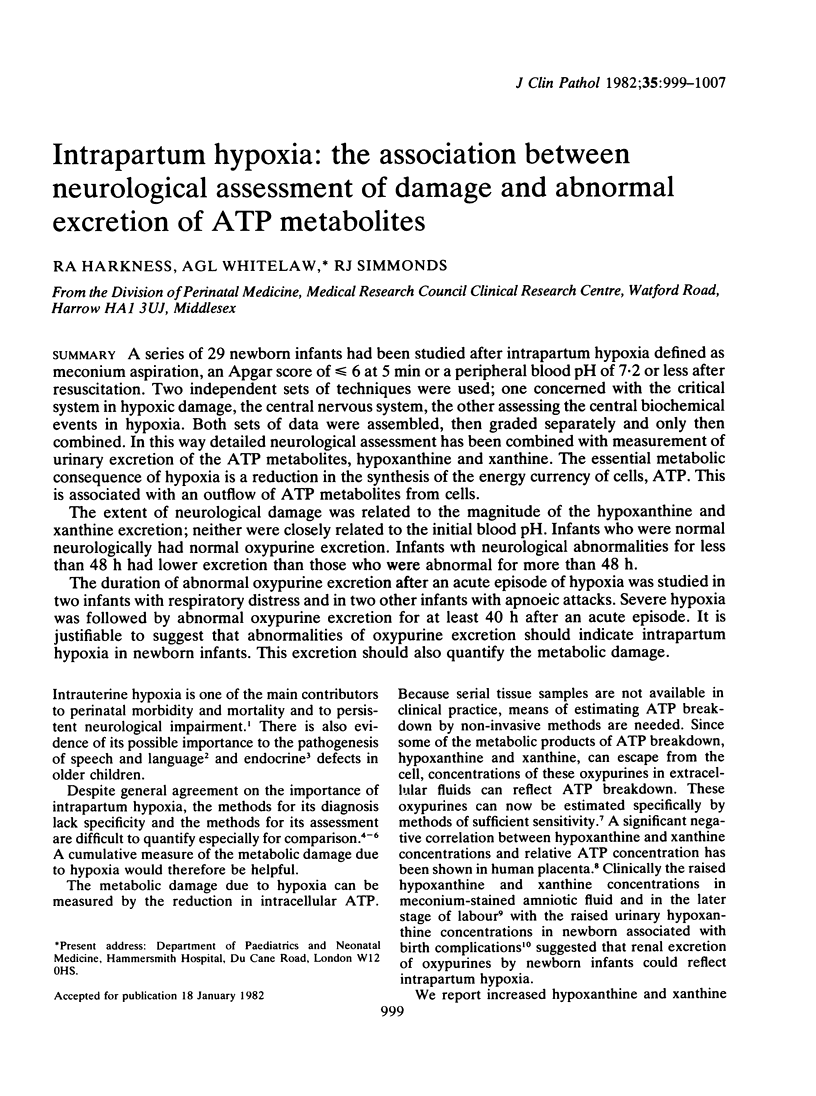

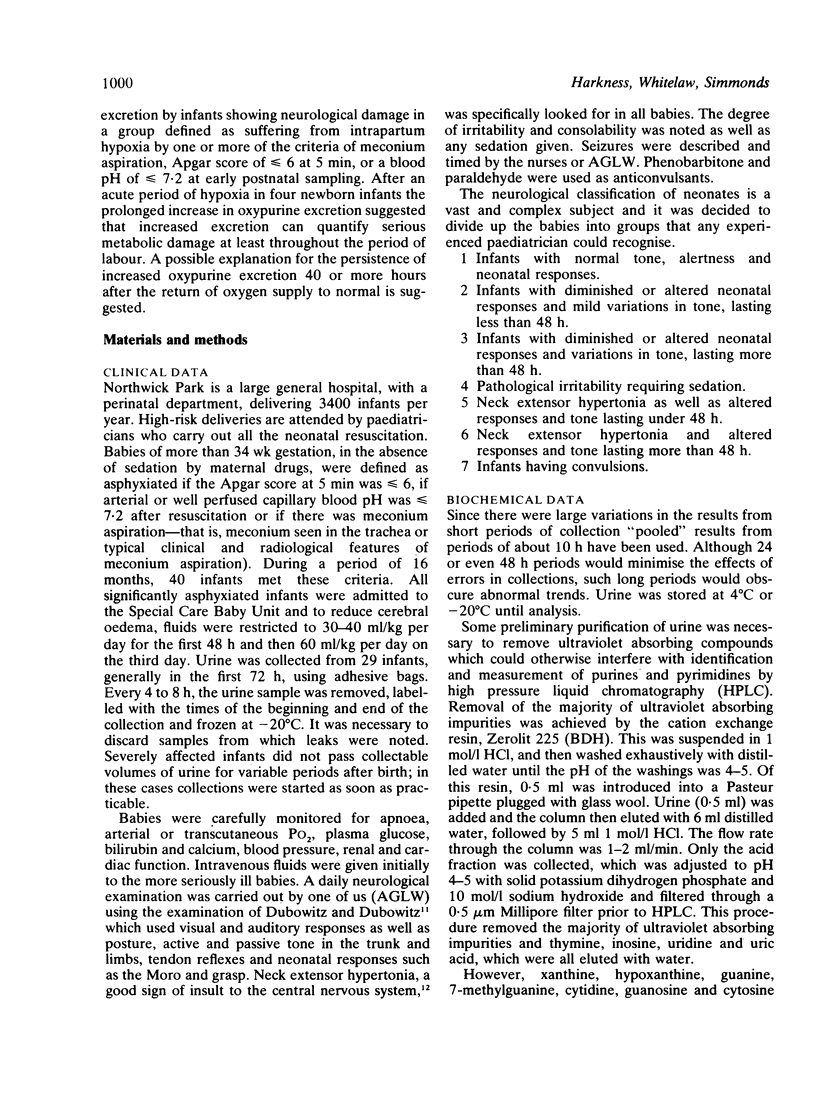

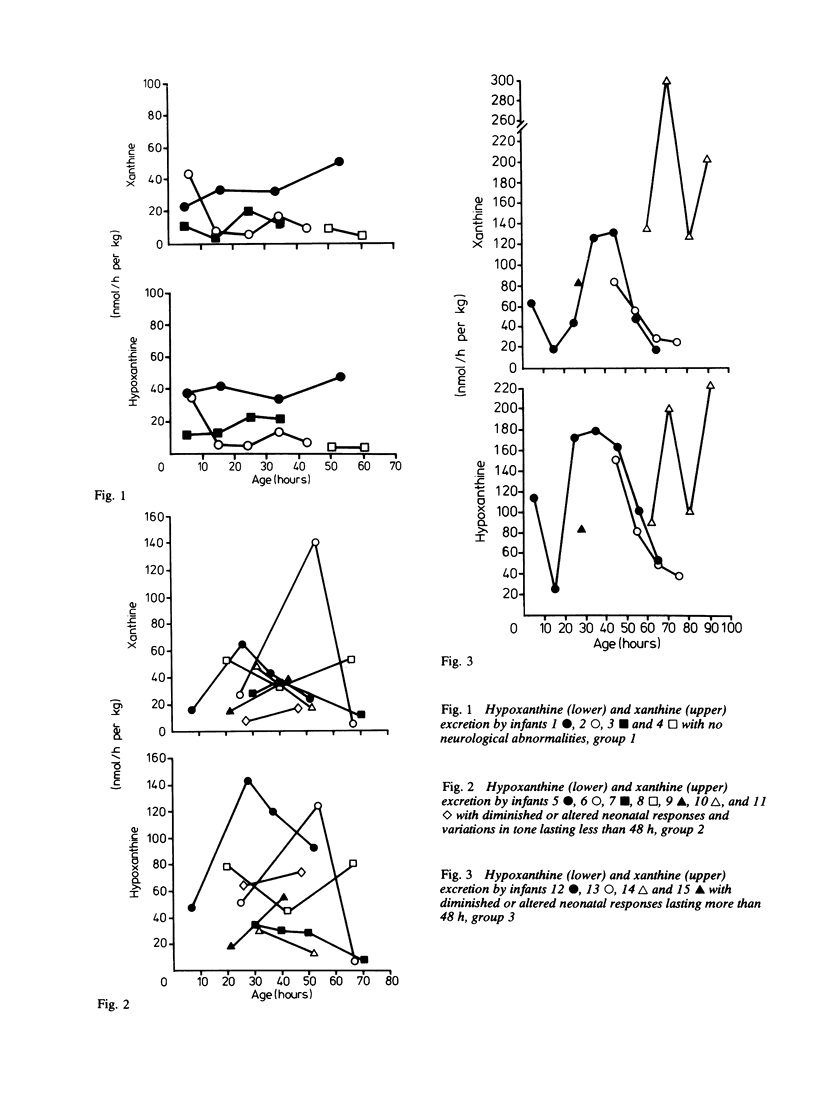

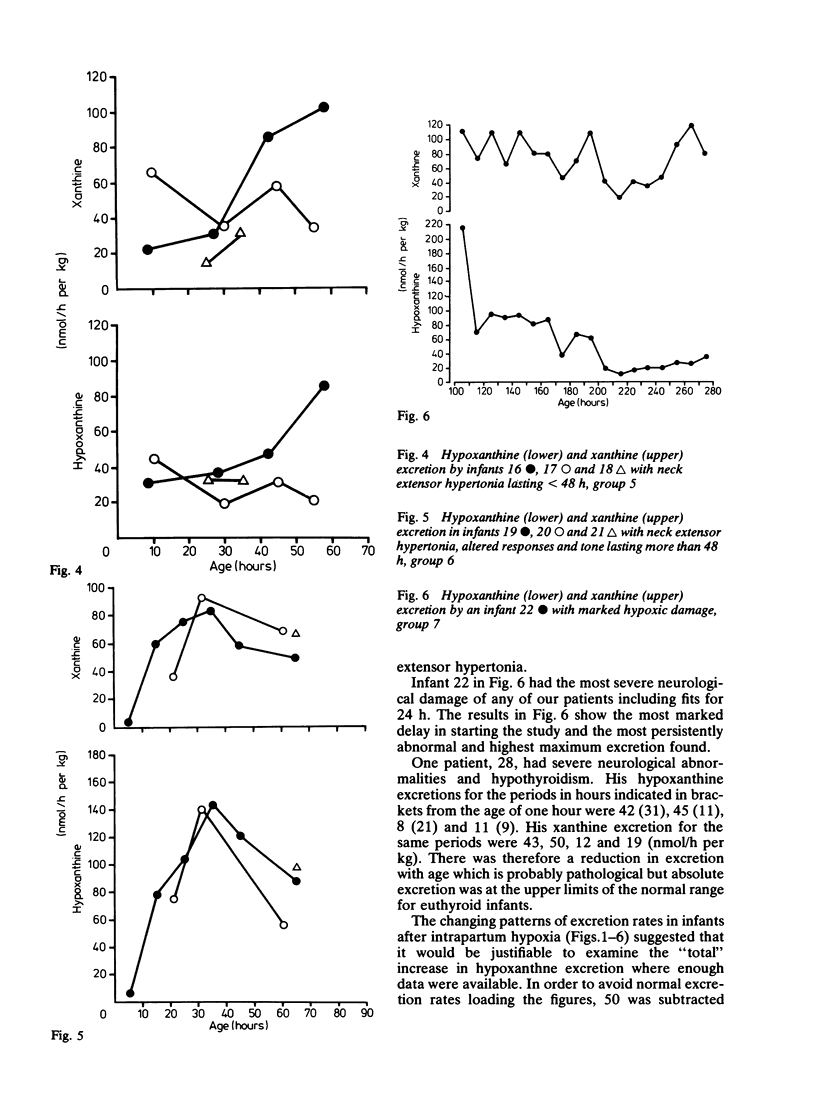

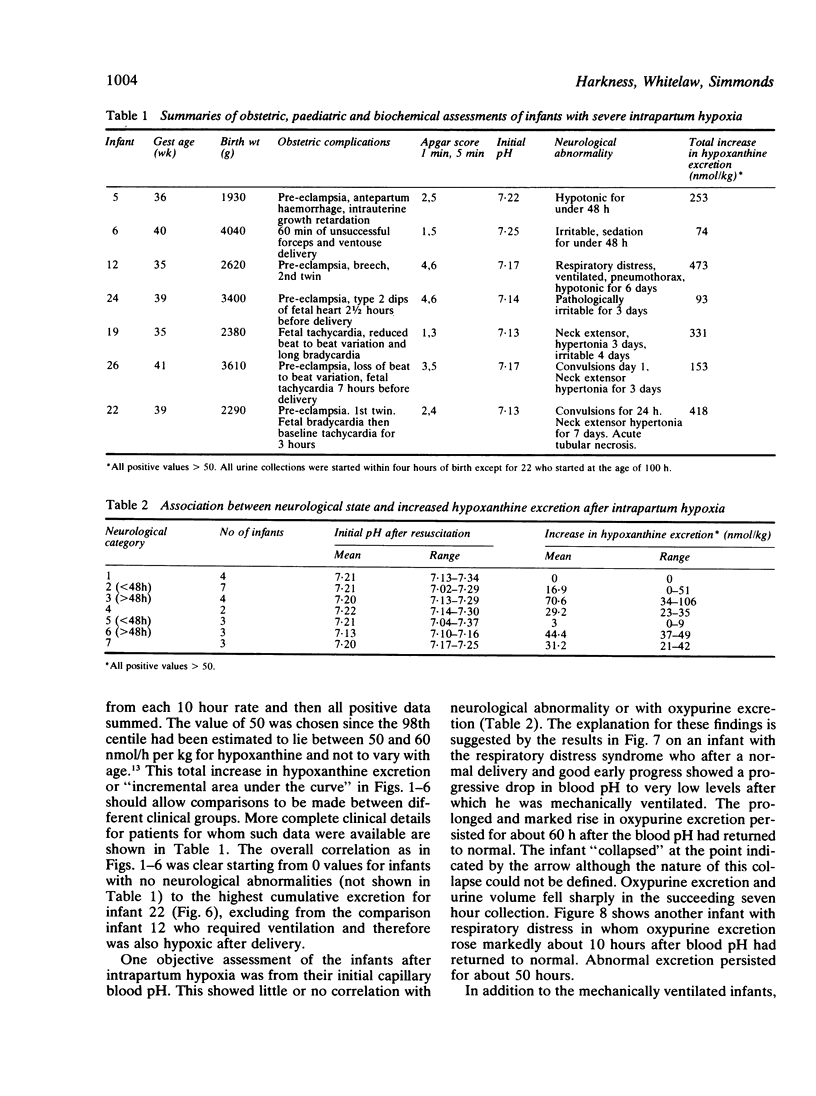

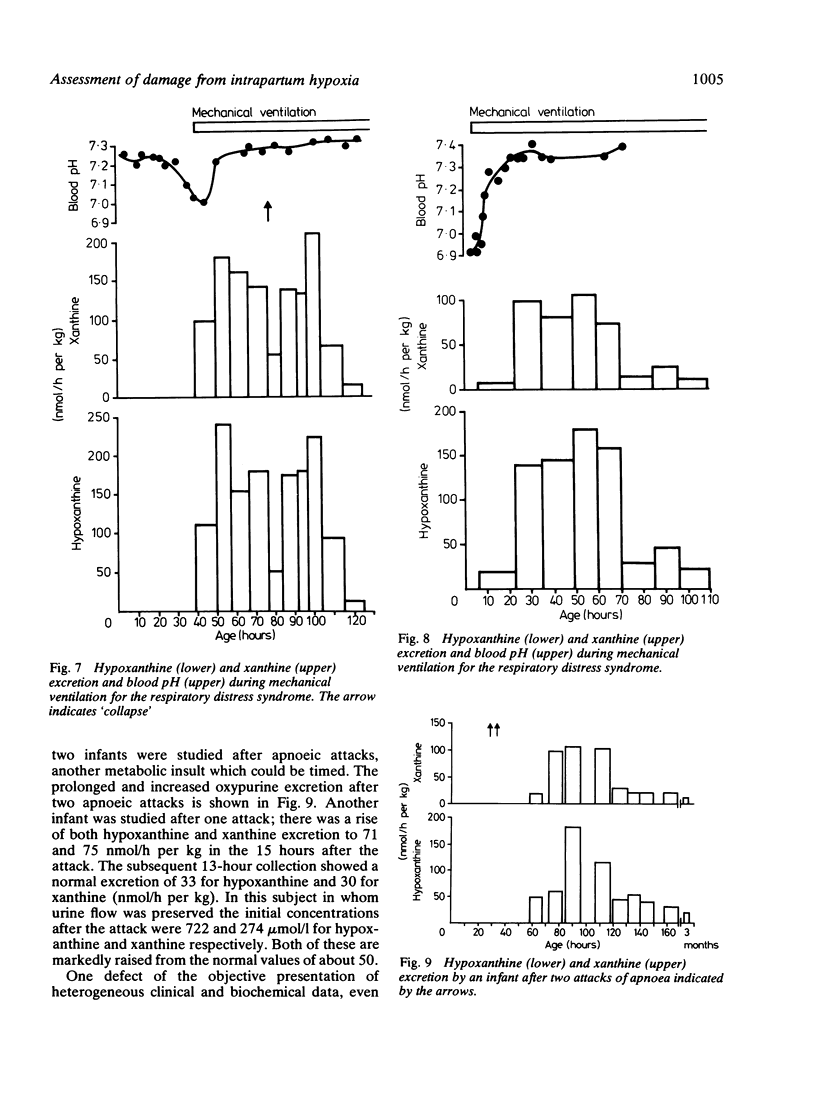

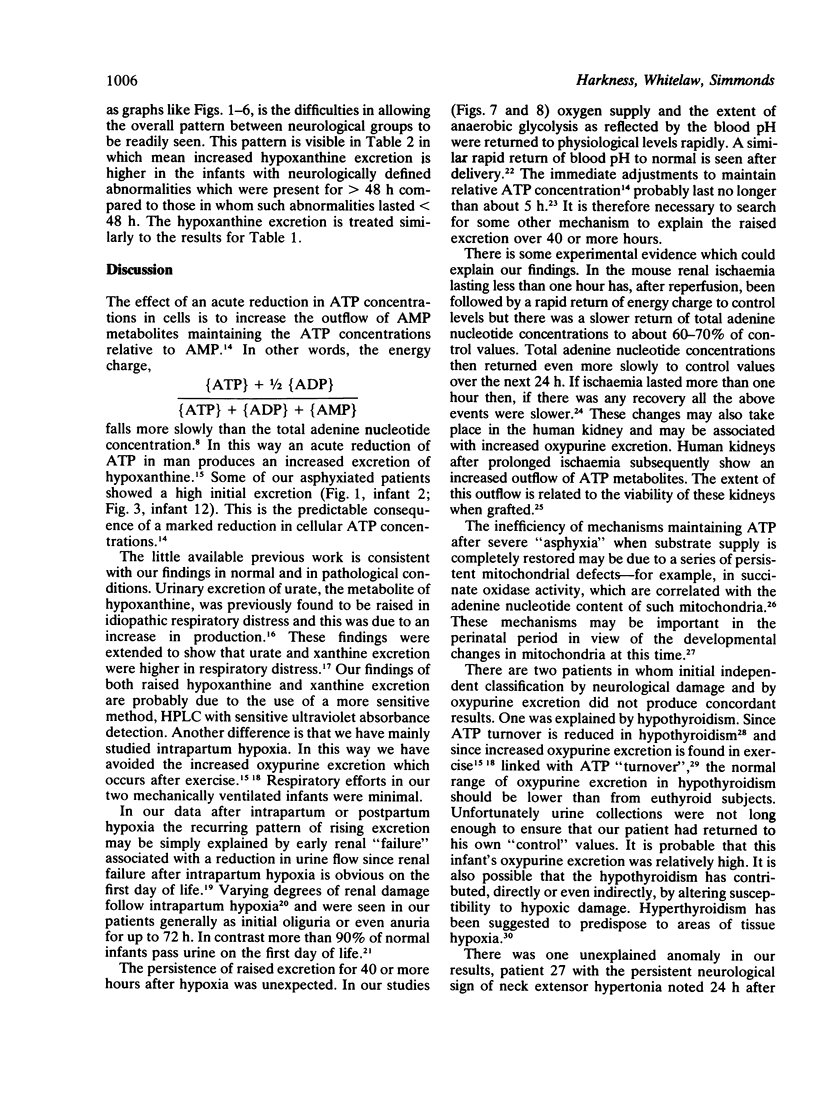

A series of 29 newborn infants had been studied after intrapartum hypoxia defined as meconium aspiration, an Apgar score of less than or equal to 6 at 5 min or a peripheral blood pH of 7.2 or less after resuscitation. Two independent sets of techniques were used; one concerned with the critical system in hypoxic damage, the central nervous system, the other assessing the central biochemical events in hypoxia. Both sets of data were assembled, then graded separately and only then combined. In this way detailed neurological assessment has been combined with measurement of urinary excretion of the ATP metabolites, hypoxanthine and xanthine. The essential metabolic consequence of hypoxia is a reduction in the synthesis of the energy currency of cells, ATP. This is associated with an outflow of ATP metabolites from cells. The extent of neurological damage was related to the magnitude of the hypoxanthine and xanthine excretion; neither were closely related to the initial blood pH. Infants who were normal neurologically had normal oxypurine excretion. Infants with neurological abnormalities for less than 48 h had lower excretion than those who were abnormal for more than 48 h. The duration of abnormal oxypurine excretion after an acute episode of hypoxia was studied in two infants with respiratory distress and in two other infants with apnoeic attacks. Severe hypoxia was followed by abnormal oxypurine excretion for at least 40 h after an acute episode. It is justifiable to suggest that abnormalities of oxypurine excretion should indicate intrapartum hypoxia in newborn infants. This excretion should also quantify the metabolic damage.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Amiel-Tison C., Korobkin R., Esque-Vaucouloux M. T. Neck extensor hypertonia: a clinical sign of insult to the central nervous system of the newborn. Early Hum Dev. 1977 Oct;1(2):181–190. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(77)90019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhl M. R. Oxypurine excretion during kidney preservation: an indicator of ischaemic damage. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1976 Mar;36(2):169–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabal L. A., Devaskar U., Siassi B., Hodgman J. E., Emmanouilides G. Cardiogenic shock associated with perinatal asphyxia in preterm infants. J Pediatr. 1980 Apr;96(4):705–710. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(80)80750-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel S. S., James L. S. Abnormal renal function in the newborn infant. J Pediatr. 1976 May;88(5):856–858. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(76)81131-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauber I. M., Krauss A. N., Symchych P. S., Auld P. A. Renal failure following perinatal anoxia. J Pediatr. 1976 May;88(5):851–855. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(76)81130-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ENGELMAN K., WATTS R. W., KLINENBERG J. R., SJOERDSMA A., SEEGMILLER J. E. CLINICAL, PHYSIOLOGICAL AND BIOCHEMICAL STUDIES OF A PATIENT WITH XANTHINURIA AND PHEOCHROMOCYTOMA. Am J Med. 1964 Dec;37:839–861. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(64)90128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelman I. S., Ismail-Beigi F. Thyroid thermogenesis and active sodium transport. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1974;30(0):235–257. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-571130-2.50010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen M. H., Brinkløv M. M., Lillquist K. Urinary loss of oxypurines in hypoxic premature neonates. Biol Neonate. 1980;38(1-2):40–48. doi: 10.1159/000241328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowenstein J. M. Ammonia production in muscle and other tissues: the purine nucleotide cycle. Physiol Rev. 1972 Apr;52(2):382–414. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1972.52.2.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzke H., Dörner K., Grünitz J. Urinary hypoxanthine, xanthine and uric acid excretion in newborn infants with perinatal complications. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1977 Nov;66(6):713–717. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1977.tb07977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller F. C., Sacks D. A., Yeh S. Y., Paul R. H., Schifrin B. S., Martin C. B., Jr, Hon E. H. Significance of meconium during labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1975 Jul 1;122(5):573–580. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(75)90052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore E. S., Galvez M. B. Delayed micturition in the newborn period. J Pediatr. 1972 May;80(5):867–873. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(72)80149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NASRALLAH S., AL-KHALIDI U. NATURE OF PURINES EXCRETED IN URINE DURING MUSCULAR EXERCISE. J Appl Physiol. 1964 Mar;19:246–248. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1964.19.2.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazawa T., Nunokawa T. Energy transduction and adenine nucleotides in mitochondria from rat liver after hypoxic perfusion. J Biochem. 1977 Dec;82(6):1575–1583. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a131852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor M. C., Harkness R. A., Simmonds R. J., Hytten F. E. Raised hypoxanthine, xanthine and uridine concentrations in meconium stained amniotic fluid and during labour. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1981 Apr;88(4):375–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1981.tb01000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor M. C., Harkness R. A., Simmonds R. J., Hytten F. E. The measurement of hypoxanthine, xanthine, inosine and uridine in umbilical cord blood and fetal scalp blood samples as a measure of fetal hypoxia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1981 Apr;88(4):381–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1981.tb01001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piatnek-Leunissen D., Olson R. E. Cardiac failure in the dog as a consequence of exogenous hyperthyroidism. Circ Res. 1967 Feb;20(2):242–252. doi: 10.1161/01.res.20.2.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raivio K. O. Neonatal hyperuricemia. J Pediatr. 1976 Apr;88(4 Pt 1):625–630. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(76)80023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmonds R. J., Coade S. B., Harkness R. A., Drury L., Hytten F. E. Nucleotide, nucleoside and purine base concentrations in human placentae. Placenta. 1982 Jan-Mar;3(1):29–38. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(82)80015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmonds R. J., Harkness R. A. High-performance liquid chromatographic methods for base and nucleoside analysis in extracellular fluids and in cells. J Chromatogr. 1981 Dec 11;226(2):369–381. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)86071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton J. R., Toews C. J., Ward G. R., Fox I. H. Purine metabolism during strenuous muscular exercise in man. Metabolism. 1980 Mar;29(3):254–260. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(80)90067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton R., Pollak J. K. The increasing adenine nucleotide concentration and the maturation of rat liver mitochondria during neonatal development. Differentiation. 1978 Nov 15;12(1):15–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1979.tb00985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnick C. T., Lazarus H. M. Recovery of nucleotide levels after cell injury. Can J Biochem. 1981 Feb;59(2):116–121. doi: 10.1139/o81-017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]