Abstract

Background:

Use of electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) among adolescents has not been fully described, in particular their motivations for using them and factors associated with use. We sought to evaluate the frequency, motivations and associated factors for e-cigarette use among adolescents in Ontario.

Methods:

We conducted a cross-sectional study in the Niagara region of Ontario, Canada, involving universal screening of students enrolled in grade 9 in co-operation with the Heart Niagara Inc. Healthy Heart Schools’ Program (for the 2013–2014 school year). We used a questionnaire to assess cigarette, e-cigarette and other tobacco use, and self-rated health and stress. We assessed household income using 2011 Canadian census data by matching postal codes to census code.

Results:

Of 3312 respondents, 2367 answered at least 1 question in the smoking section of the questionnaire (1274 of the 2367 respondents [53.8%] were male, with a mean [SD] age of 14.6 [0.5] yr) and 2292 answered the question about use of e-cigarettes. Most respondents to the questions about use of e-cigarettes (n = 1599, 69.8%) had heard of e-cigarettes, and 380 (23.8%) of these respondents had learned about them from a store sign or display. Use of e-cigarettes was reported by 238 (10.4%) students. Most of the respondents who reported using e-cigarettes (171, 71.9%) tried them because it was “cool/fun/new,” whereas 14 (5.8%) reported using them for smoking reduction or cessation. Male sex, recent cigarette or other tobacco use, family members who smoke and friends who smoke were strongly associated with reported e-cigarette use. Reported use of e-cigarettes was associated with self-identified fair/poor health rating (odds ratio [OR] 1.9 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.2–3.0), p < 0.001), high stress level (OR 1.7 (95% CI 1.1–2.7), p < 0.001) and lower mean (33.4 [8.4] × $1000 v. 36.1 [10.7] × $1000, p = 0.001) and median [interquartile range] (26.2 [5.6] × $1000 v. 28.1 [5.7] × $1000) household incomes.

Interpretation:

Use of e-cigarettes is common among adolescents in the Niagara region and is associated with sociodemographic features. Engaging in seemingly exciting new behaviours appears to be a key motivating factor rather than smoking cessation.

Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) are novel devices that are designed to mimic the physical and tactile experience of conventional cigarettes while producing a smoke-free vapour. They have quickly gained popularity despite limited evidence regarding the health risks associated with their use and a lack of regulation.1 In addition, existing literature about e-cigarettes suggests that they may not be effective for achieving smoking reduction or cessation, a use for which they are often marketed.1–3 Given their physical similarities to conventional cigarettes, there are concerns that the increasing use of e-cigarettes may result in the “renormalization” of cigarette smoking.4,5 Previous studies have suggested that use of e-cigarettes among adolescents and young adults may be associated with use of and exposure to tobacco.1,6,7

Rates of the use of e-cigarettes at least once among high school students in the United States have increased annually.6,8 Among adolescents in Canada, use of e-cigarettes is now more common than cigarette use.9 However, questions still remain regarding the motivations and factors associated with e-cigarette use among adolescents. Therefore, we sought to evaluate the frequency, motivations and associated factors for use of e-cigarettes by students in grade 9 who were undergoing universal school-based screening for cardiovascular risk factors in the Niagara region in Ontario.

Methods

Setting, participants and study design

We conducted a cross-sectional, school-based study of grade 9 students (aged 14–15 yr) in the Niagara region of Ontario during the 2013–2014 academic school year. We undertook this study in co-operation with the Heart Niagara Inc. Healthy Heart Schools’ Program, a curriculum-enrichment program that provides personalized education about cardiometabolic risk and healthy lifestyle behaviours, and individualized testing for cardiovascular risk factors to students in the classroom setting. This program performs universal screening annually for students enrolled in grade 9 in the Niagara region. The methodology of this program was described previously.10,11

We obtained written consent from parents and written assent from students to participate in the assessment.

We provided students with questionnaires that were to be completed at home before each school’s predetermined screening day. The front page of the questionnaire contained the consent form for parents to complete. The first section of the questionnaire was an assessment of family history of cardiometabolic disease (the only section that would require parental assistance to complete). The student was expected to complete the rest of the questionnaire on their own.

For the smoking and tobacco portion of the questionnaire, students were asked to select only 1 option for each question. Questions for this section included “Have you ever taken at least one puff from an electronic cigarette?” and “If yes, why did you try an e-cigarette?” (options: “a. It’s cool/fun/something new; b. For the buzz; c. To help me quit smoking; d. To help me smoke less; e. To help me when I’m not allowed to smoke”). Regarding cigarette smoking, students were asked “Do you smoke now?” and “Think about the last 30 days. Did you smoke a cigarette, even a puff?” Students were also asked questions about their frequency of smoking, if they had used other forms of tobacco (e.g., cigars, cigarillos and water pipes), their exposure to smoke in the home, whether they had family members who smoked, whether their friends smoked and their knowledge of the detrimental effects of smoking. We adapted these questions from the Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol, and Drugs Use Survey,12 Ontario Student Drug Use and Health Survey,13 Canadian Tobacco Use Monitoring Survey14 and the Propel Centre for Population Health Impact (youth respondents questionnaire template).15 We also asked questions about self-perceived health and stress levels.

We recorded the residence postal codes of the students and, through a link with data from the 2011 Canadian Census,16 we estimated household income. Completed questionnaires were returned to Heart Niagara Inc. during that particular school’s designated Healthy Heart Schools’ Program day. Questionnaires did not need to be completed in their entirety to be included for data analysis. Teachers and other school employees did not have access to the individual responses.

Outcomes

Our main outcome for this study was to evaluate the prevalence of and motivations for using e-cigarettes among students in the Niagara region, and the sociodemographic associations with e-cigarette use, including concomitant tobacco use, use of tobacco by family and friends, self-rated health and stress levels, and socioeconomic status.

Data analysis

We reported the data either as means with standard deviations, medians with interquartile ranges or frequencies, as appropriate, based on the type and distribution of the data. We used multiple imputation to account for missing values. Specifically, we created 100 imputed data sets and conducted logistic regression analysis to quantify the association between e-cigarette use and prespecified risk factors in terms of odds ratios (ORs). Some of the risk factors we considered included sex, home smoking environment, smoking status of responders, family members and friends, and self-reported health and stress levels. We used 2-sample t tests to assess the association between income estimates and e-cigarette use.

All statistical analyses assumed a significance of 5% and were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Ethics approval

Heart Niagara Inc. received formal ethics approval from the research ethics committees of both the Niagara Catholic District School Board and the District School Board of Niagara. We obtained approval for retrospective data analysis of deidentified data provided by Heart Niagara Inc. from the Research Ethics Board of The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ont.

Results

In the 2013–2014 school year, there were 4390 students enrolled in grade 9 in the Niagara region, 4109 received a questionnaire, 3312 submitted a questionnaire, 2367 answered at least 1 question in the smoking section of the questionnaire (response rate of 57.6%) and 2292 answered the e-cigarette use section (Table 1). We found no significant difference between the 2367 students who answered at least 1 question in the smoking section of the questionnaire and the 945 students who did not answer at least 1 question (Appendix 1, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.151169/-/DC1).

Table 1:

Characteristics of respondents in the Niagara region by population, e-cigarette use, cigarette use and use of other tobacco products

| Characteristic | No. (%) of respondents n = 3312* |

Percentage of total |

|---|---|---|

| Population | ||

| Answered at least 1 question in the smoking section of the survey | 2367 (71.5) | |

| Male (n = 2367) | 1274 (53.8) | |

| E-cigarette use | ||

| Heard of e-cigarettes (n = 2292) | 1599 (69.8) | |

| How students learned about e-cigarettes (n = 1599) | ||

| Friends | 485 (30.3) | |

| Store sign/display | 380 (23.8) | |

| Internet | 186 (11.6) | |

| Other | 529 (33.1) | |

| No answer | 19 (1.2) | |

| Had used e-cigarettes (n = 2278) | 238 (10.4) | |

| Quantity of e-cigarette use (n = 238) | ||

| Once | 134 (56.3) | 5.8† |

| A few times | 79 (33.2) | 3† |

| Frequently | 13 (5.5) | 0.6† |

| Daily | 5 (2.1) | 0.2† |

| No answer | 7 (2.9) | 0.3† |

| Cigarette use | ||

| Currently smoke (n = 2344) | 61 (2.6) | |

| Had smoked cigarettes during the last 30 d (n = 2302) | 66 (2.9) | |

| Frequency of smoking during the last 30 d (n = 66) | ||

| 1–2 d | 25 (37.9) | 1.0‡ |

| Some days | 17 (25.8) | 1.0‡ |

| Every day or almost every day | 24 (36.4) | 1.0‡ |

| Quantity of cigarettes smoked during the last 30 d (n = 66) | ||

| ≤ 1 per d | 35 (53.0) | 1.5‡ |

| 2–5 per d | 14 (21.2) | 0.6‡ |

| > 5 per d | 7 (10.6) | 0.3‡ |

| No response | 10 (15.1) | 0.4‡ |

| Type of smoker (self-defined) (n = 2205) | ||

| Nonsmoker | 2128 (96.5) | |

| Nonsmoker who sometimes smokes | 32 (1.5) | |

| Former smoker, quit completely | 11 (0.5) | |

| Light smoker | 14 (0.6) | |

| Moderate/heavy smoker | 20 (0.9) | |

| Other tobacco products | ||

| Had smoked cigarillos (n = 2297) | 84 (3.7) | |

| Had used smokeless tobacco (n = 2291) | 33 (1.4) | |

| Had smoked using a water pipe (n = 2288) | 57 (2.5) | |

Note: e-cigarette = electronic cigarette.

Unless otherwise indicated.

Distribution of frequency of e-cigarette use among all respondents to the e-cigarette questionnaire (n = 2278).

Distribution of smoking frequency and quantity during the last 30 d among all respondents to the smoking section of the questionnaire (n = 2302).

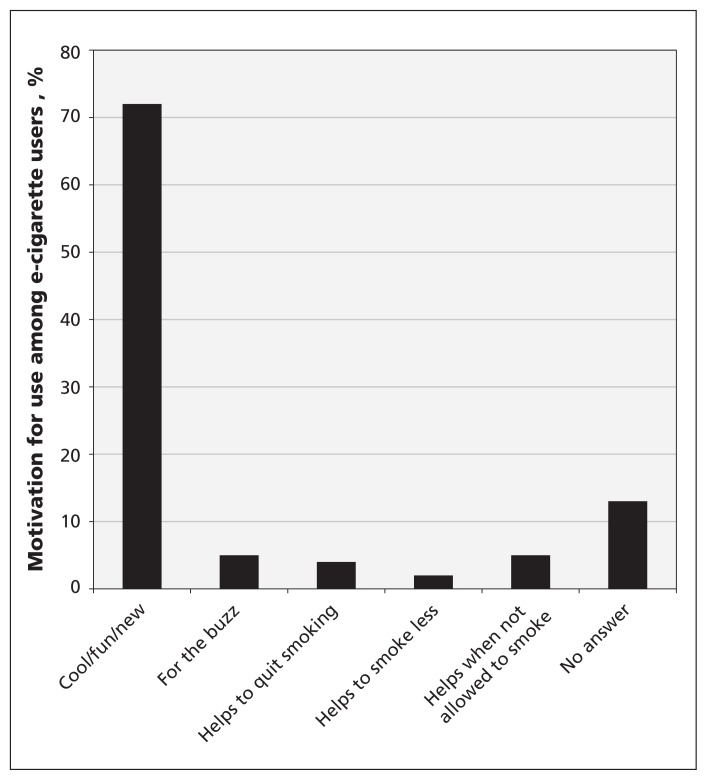

Sixty-six (2.8%) students reported cigarette use during the previous 30 days, and 174 (7.6%) had used cigarillos, smokeless tobacco or water pipes at least once (Table 1). Of 2321 respondents to the environment question, 1201 (51.7%) had family members who smoked and 811 (35.3%) had friends who smoked (Appendix 2, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.151169/-/DC1). Of 2278 respondents, 238 (10.4%) reported using e-cigarettes. Of these, 134 (56.3%) reported using them once, whereas 79 (33.2%) reported using them “a few times.” The most common reason for trying e-cigarettes was that they were “cool/fun/something new” (n = 171, 71.8%), whereas 9 (3.8%) and 5 (2.1%) respondents reported using them to quit smoking or smoke less, respectively (Figure 1). Forty-six students reported smoking cigarettes during the last 30 days and reported using e-cigarettes. Of these respondents, 22 (47.8%) used them because they were “cool/fun/something new,” whereas 15 (32.6%) respondents used e-cigarettes to help them quit smoking, smoke less or to help when they were not allowed to smoke.

Figure 1:

Motivating factors for using e-cigarettes among study respondents (n = 238).

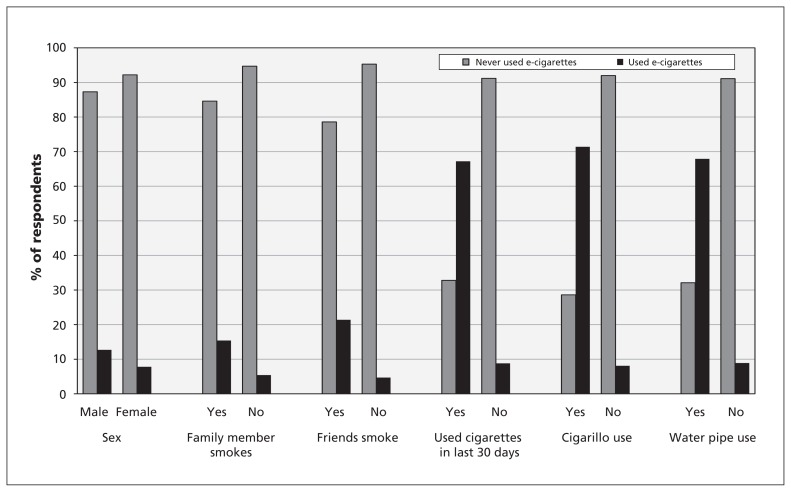

Male sex, previous tobacco use, having family members who smoke and having friends who smoke were all significantly associated with having used e-cigarettes (Figure 2, Table 2). Students who self-identified as currently smoking had the strongest association with using e-cigarettes (OR 12.1, 95% CI 6.6–22.4). Among students who reported smoking cigarettes during the last 30 days (n = 61), 41 (67.2%) had reported using e-cigarettes; among students who reported not smoking during the last 30 days (n = 2194), only 193 (8.8%) had reported using e-cigarettes (p < 0.001). Conversely, among those respondents who reported using e-cigarettes (n = 234), 41 (17.5%) reported smoking cigarettes during the last 30 days compared with 20 of 2001 (1.0%) respondents who reported never using e-cigarettes (p < 0.001). Reported use of e-cigarettes was associated with lower self-reported health rating, higher self-reported stress level and lower estimated household income (i.e., mean [SD] (33.4 [8.4] × $1000 v. 36.1 [10.7] × $1000, p = 0.001) and median [interquartile range] (26.2 [5.6] × $1000 v. 28.1 [5.7] × $1000) household incomes) (Appendix 3, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.151169/-/DC1).

Figure 2:

Characteristics of respondents, by use of e-cigarettes. Note: Total no. of respondents who had used e-cigarettes: Sex, n = 238; Family member smokes, n = 236; Friends smoke, n = 236; Used cigarettes in last 30 d, n = 234; Cigarillo use, n = 236; Water pipe use, n = 234. Total no. of respondents who had not used e-cigarettes: Sex, n = 2040; Family member smokes, n = 2005; Friends smoke, n = 1999; Used cigarettes in last 30 d, n = 2021; Cigarillo use, n = 2034; Water pipe use, n = 2025.

Table 2:

Odds ratios calculated using multivariable logistic regression* for the association between e-cigarette use and sociodemographic factors, by risk factor

| Risk factor | OR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 1.7 (1.2–2.3) | 0.002 |

| Respondent knew that smoking can cause lung cancer | 0.2 (0.02–1) | 0.05 |

| Respondent had family members who smoke tobacco | 1.7 (1.2–2.4) | 0.003 |

| Respondent had friends who smoke tobacco | 3.6 (2.6–4.9) | < 0.001 |

| Respondent currently smoked tobacco | 12.1 (6.6–22.4) | < 0.001 |

| Smoking allowed inside respondent’s home | 1.8 (1.2–2.7) | 0.007 |

| Respondent reported excellent or good stress level | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) | 0.003 |

Note: CI = confidence interval, e-cigarette = electronic cigarette, OR = odds ratio. OR > 1 suggests a positive association between e-cigarette use and risk factor.

With multiple imputation of missing data.

Interpretation

We found that most respondents (n = 1599) to the survey were aware of e-cigarettes and 238 (10.4%) had used them previously. Most users of e-cigarettes did so because they were “cool/fun/new,” whereas only a few used them for smoking cessation. E-cigarette use was more common among male respondents and strongly associated with cigarette use, other tobacco use and tobacco use among family members and friends. Use of e-cigarettes was associated with lower self-identified health level, greater stress level and a lower estimated household income, which suggests that e-cigarette use may have some key associations that may help to identify adolescents at risk.

The popularity of e-cigarettes has increased in recent years,17 including among youth. Previous data from Canada showed use rates in adolescents and young adults that ranged from 15% to 20%.9,18,19 In our study, the lower use rate of 10.4% may be due to our assessment of younger adolescents (aged 14–15 yr). While e-cigarettes are frequently used as devices for smoking cessation in adults,3,20–22 we found most students in our survey (including 47.8% of those who recently smoked cigarettes) were motivated by the “cool/fun/something new” features of e-cigarettes. A survey involving adolescents in Hawaii similarly found their motivations to be curiosity and exploration,23 whereas 2 studies involving adults who used e-cigarettes found only 10% were motivated by curiosity.3,21 Thus, motivations for use may differ between adolescents and adults.

We found strong associations between e-cigarette use and recent cigarette smoking, a finding that has been shown both in adults8,24,25 and youth.6,8,18,19,26 Despite these strong associations, we found 82.5% of respondents who had used e-cigarettes had not smoked cigarettes during the previous 30 days. Two recent longitudinal studies involving adolescents and young adults showed significantly increased tobacco uptake among those who used e-cigarettes compared with those who had never used them.27,28 Further studies are required to assess whether e-cigarette use is a contributing factor toward increased future tobacco uptake among youth.

Use of e-cigarettes was greater among male respondents, a finding that has been noted previously.6,7,18,26 Use was also strongly associated with having family members and friends who smoked. Cardenas and colleagues similarly noted that living with people who smoke was associated with increased awareness and use of e-cigarettes.7 We found e-cigarette use to be associated with lower estimated household income. Two previous studies showed use to be associated with lower education,19,25 whereas a study involving Canadian youth found having more spending money was associated with e-cigarette use,26 and a study of adults noted greater use among those with greater incomes.2 Further studies are required to evaluate the associations between e-cigarette use and socioeconomic status.

We found strong associations between use of e-cigarettes and worsened perceived ratings of health and stress levels. Future studies will be required to further explore this novel finding.

Limitations

Our study had a number of limitations. Because it was cross-sectional, we derived associations rather than causations. We administered the questionnaire in only 1 region; therefore, the results may not be generalizable to the rest of Canada. However, census data suggest that, other than immigrant/ethnic distributions in the Niagara region population (lower proportion in the Niagara region compared with the distribution in Ontario), the population distribution is quite similar to the broader Ontario population.29,30 We evaluated use of cigarettes during the previous 30 days rather than rates of ever having used cigaretes. Although the questionnaire was structured such that parental involvement was only required at the beginning (consent and family history assessment), it is possible that parents may have been able to see the students’ responses. This may have resulted in underreporting and may have contributed to our low response rate. Finally, use of residential postal codes and census data may have been inaccurate at the individual level.

Conclusion

Use of e-cigarettes is common among students enrolled in grade 9 in the Niagara region and is associated with numerous potential risk factors, including exposure to use of tobacco by family members and friends, and personal tobacco use. Smoking reduction and cessation do not appear to be motivating factors for the use of e-cigarettes among these respondents. Adolescents in this population appear to be motivated by the appeal of trying something new. Future studies will be required to assess the short- and long-term health impact of e-cigarettes and whether they play a role in the adoption of future tobacco use. Our findings support the ongoing implementation of strict regulations to help reduce e-cigarette use among adolescents.

See also page 785 and www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.160728

Footnotes

CMAJ Podcasts: author interview at https://soundcloud.com/cmajpodcasts/151169-res

Competing interests: Brian McCrindle has received consultant fees from Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Aergerion Pharmaceuticals, Merck and Bristol-Myers Squibb, and grants from Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Amgen and Daiichi Sankyo. No other competing interests were declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Michael Khoury, Cedric Manlhiot, Don Gibson, Nita Chahal and Brian McCrindle contributed to the conception and design of the study. Don Gibson, Karen Stearne and Stafford Dobbin were involved in the acquisition of data. Michael Khoury, Cedric Manlhiot, Steve Fan and Brian McCrindle were involved in the analysis and interpretation of the data. Michael Khoury, Cedric Manlhiot, Steve Fan and Brian McCrindle drafted the manuscript. All of the authors reviewed the manuscript critically for intellectual content and approved the final version to be published.

Funding: Support for this study was received from CIBC World Markets Children’s Miracle Foundation Chair in Child Health Research, a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Team Grant in Childhood Obesity and Heart Niagara Inc.

References

- 1.Grana R, Benowitz N, Glantz SA. E-cigarettes: a scientific review. Circulation 2014;129:1972–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adkison SE, O’Connor RJ, Bansal-Travers M, et al. Electronic nicotine delivery systems: international tobacco control four-country survey. Am J Prev Med 2013;44:207–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vickerman KA, Carpenter KM, Altman T, et al. Use of electronic cigarettes among state tobacco cessation quitline callers. Nicotine Tob Res 2013;15:1787–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Labonte R, Lencucha R. Regulating electronic cigarettes: finding the balance between precaution and harm reduction. CMAJ 2015;187:862–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fairchild AL, Bayer R, Colgrove J. The renormalization of smoking? E-cigarettes and the tobacco “endgame.” N Engl J Med 2014;370:293–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dutra LM, Glantz SA. Electronic cigarettes and conventional cigarette use among US adolescents: a cross-sectional study. JAMA Pediatr 2014;168:610–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cardenas VM, Breen PJ, Compadre CM, et al. The smoking habits of the family influence the uptake of e-cigarettes in US children. Ann Epidemiol 2015;25:60–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease C. Prevention. Notes from the field: electronic cigarette use among middle and high school students — United States, 2011–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013;62:729–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey (CTADS): summary of results for 2013. Ottawa: Government of Canada; 2015. Available: http://healthycanadians.gc.ca/science-research-sciences-recherches/data-donnees/ctads-ectad/summary-sommaire-2013-eng.php. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Narang I, Manlhiot C, Davies-Shaw J, et al. Sleep disturbance and cardiovascular risk in adolescents. CMAJ 2012; 184: e913–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCrindle BW, Manlhiot C, Millar K, et al. Population trends toward increasing cardiovascular risk factors in Canadian adolescents. J Pediatr 2010;157:837–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2013. Available: www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p3Instr.pl?Function=assembleInstr&lang=en&Item_Id=202746. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ontario Student Drug Use and Health Survey. Toronto: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health; 2015. Available: www.camh.ca/en/research/news_and_publications/ontario-student-drug-use-and-health-survey/Pages/default.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Canadian Tobacco Use Monitoring Survey (CTUMS). Ottawa: Health Canada; 2014. Available: www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hc-ps/tobac-tabac/research-recherche/stat/index-eng.php. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Core indicators and measures of youth health: tobacco control module. Waterloo (ON): University of Waterloo: Propel Centre for Population Health Impact; 2012; Available: https://uwaterloo.ca/propel/program-areas/healthy-living/core-indicators-and-measures-youth-health/tobacco-control. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Census of population program datasets: 2011 Census of Population. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2011. Available: www12.statcan.gc.ca/datasets/Index-eng.cfm?Temporal=2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamin CK, Bitton A, Bates DW. E-cigarettes: a rapidly growing Internet phenomenon. Ann Intern Med 2010;153:607–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamilton HA, Ferrence R, Boak A, et al. Ever use of nicotine and nonnicotine electronic cigarettes among high school students in Ontario, Canada. Nicotine Tob Res 2015;17:1212–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Czoli CD, Hammond D, White CM. Electronic cigarettes in Canada: prevalence of use and perceptions among youth and young adults. Can J Public Health 2014;105:e97–e102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franck C, Budlovsky T, Windle SB, et al. Electronic cigarettes in North America: history, use, and implications for smoking cessation. Circulation 2014;129:1945–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Etter JF. Electronic cigarettes: a survey of users. BMC Public Health 2010;10:231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pokhrel P, Fagan P, Little MA, et al. Smokers who try e-cigarettes to quit smoking: findings from a multiethnic study in Hawaii. Am J Public Health 2013;103:e57–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wills TA, Knight R, Williams RJ, et al. Risk factors for exclusive e-cigarette use and dual e-cigarette use and tobacco use in adolescents. Pediatrics 2015;135:e43–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pearson JL, Richardson A, Niaura RS, et al. e-Cigarette awareness, use, and harm perceptions in US adults. Am J Public Health 2012;102:1758–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Regan AK, Promoff G, Dube SR, et al. Electronic nicotine delivery systems: adult use and awareness of the ‘e-cigarette’ in the USA. Tob Control 2013;22:19–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Czoli CD, Hammond D, Reid JL, et al. Use of conventional and alternative tobacco and nicotine products among a sample of Canadian youth. J Adolescent Health 2015;57:123–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leventhal AM, Strong DR, Kirkpatrick MG, et al. Association of electronic cigarette use with initiation of combustible tobacco product smoking in early adolescence. JAMA 2015; 314:700–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Primack BA, Soneji S, Stoolmiller M, et al. Progression to traditional cigarette smoking after electronic cigarette use among US adolescents and young adults. JAMA Pediatr 2015; 169: 1018–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Population and demographics — statistics in Niagara. Thorold (ON): Niagara Region; 2015. Available: https://www.niagararegion.ca/health/statistics/demographics/default.aspx (accessed 2015 Dec. 26). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Focus on geography series, 2011 census. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2015. Available: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/as-sa/fogs-spg/Facts-csd-eng.cfm?LANG=Eng&GK=CSD&GC=3526043 (accessed 2015 Dec. 26). [Google Scholar]