Abstract

Objective

The primary aim was to compare the impact of NAVIGATE, a comprehensive, multidisciplinary, team-based treatment approach for first episode psychosis designed for implementation in the U.S. healthcare system, to Community Care on quality of life.

Methods

Thirty-four clinics in 21 states were randomly assigned to NAVIGATE or Community Care. Diagnosis, duration of untreated psychosis and clinical outcomes were assessed via live, two-way video by remote, centralized raters masked to study design and treatment. Participants (mean age 23) with schizophrenia and related disorders and ≤6 months antipsychotic treatment (N=404) were enrolled and followed for ≥2 years. The primary outcome was the Total Score of the Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale, a measure that includes sense of purpose, motivation, emotional and social interactions, role functioning and engagement in regular activities.

Results

223 NAVIGATE recipients remained in treatment longer, experienced greater improvement in quality of life, psychopathology and involvement in work/school compared to 181 Community Care participants. The median duration of untreated psychosis=74 weeks. NAVIGATE participants with duration of untreated psychosis <74 weeks had greater improvement in quality of life and psychopathology compared with those with longer duration of untreated psychosis and those in Community Care. Rates of hospitalization were relatively low compared to other first episode psychosis clinical trials and did not differ between groups.

Conclusions

Comprehensive care for first episode psychosis can be implemented in U.S. community clinics. and improves functional and clinical outcomes. Effects are more pronounced for those with shorter duration of untreated psychosis.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is associated with enormous personal suffering, disability, family burden, premature death, and societal cost (1,2). Randomized trials suggest that intervention close to psychosis onset improves symptoms and functioning more than traditional care (3,4). Comprehensive first episode psychosis programs that emphasize low-dose antipsychotic medications, cognitive behavioral psychotherapy, family education/support, and vocational/educational recovery have been implemented worldwide (5-11), but few randomized controlled trials have compared multimodal, multidisciplinary team approaches to usual care in first episode psychosis (12-16). Such programs can be easier to implement in settings with a national healthcare system, perhaps why a multi-site study of first episode psychosis treatment has never been conducted in the U.S. in non-academic, community clinics under existing reimbursement mechanisms. Despite the fact that academic centers play a key role in developing and testing new treatment strategies, such strategies must be implemented in typical, “real world” settings.

This report presents two-year outcome data from first episode psychosis subjects participating in a multi-site, randomized controlled trial comparing comprehensive, team-based treatment to usual care in U.S. community treatment centers. We also explored how the duration of untreated psychosis influences treatment response.

Methods

The Early Treatment Program (ETP) study is part of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode (RAISE) initiative. RAISE aims to develop, test, and implement person-centered, integrated treatment approaches for first episode psychosis that promote symptomatic and functional recovery. The background, rationale, and design of the RAISE-ETP trial is described elsewhere (17).

a. Subjects

404 individuals between ages 15-40 were enrolled. (a consort diagram appears in Supplemental Figure S1.) DSM-IV (18) diagnoses of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, schizophreniform disorder, brief psychotic disorder, or psychotic disorder not otherwise specified were included. Diagnoses of affective psychosis, substance-induced psychotic disorder, psychosis due to general medical conditions, clinically significant head trauma, or other serious medical conditions were excluded. All participants had experienced only one episode of psychosis (i.e. individuals with a psychotic episode followed by full symptom remission and relapse to another psychotic episode were excluded) and had taken ≤6 months of lifetime antipsychotics. All spoke English.

Written informed consent was obtained from adult participants and legal guardians of those under 18 years old, who provided written assent. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the coordinating center and the participating sites. The NIMH Data and Safety Monitoring Board provided study oversight.

b. Clinical Sites and Randomization

Thirty-four community mental health treatment centers in 21 states were selected via national search. Site eligibility criteria included (1) experience treating people with schizophrenia; (2) interest in offering early intervention services for first episode psychosis; (3) sufficient staff to implement the experimental intervention; (4) ability to recruit an adequate number of subjects; and (5) institutional assurance that research assessments would be completed. Academic centers or sites with existing first episode programs were excluded.

RAISE-ETP employed a cluster randomization design; i.e., randomization by clinic rather than individual patient (19). Clinics were randomly assigned to the experimental intervention (n=17) or standard care (n=17). None withdrew after randomization.

c. Interventions

The experimental treatment, NAVIGATE (20), includes four core interventions: personalized medication management (assisted by “COMPASS,” a secure, web-based, computerized decision support system developed for RAISE-ETP); family psychoeducation; resilience-focused individual therapy; and supported education and employment (SEE). Treatment was supported through existing funding mechanisms except for SEE, which is not supported in many locations. SEE services (5 hours/week) were supported with research funds.

Treatment components are offered/implemented within a shared decision-making, patient preference framework (21). Weekly team meetings facilitated communication and coordination. NAVIGATE sites received initial training in team-based first episode psychosis interventions and on-going expert consultation facilitated fidelity (20). We continually assessed clinicians’ competence and monitored team functioning. These assessments will be reported later.

The control condition, “Community Care”, is psychosis treatment determined by clinician choice and service availability. Community Care sites received no additional training or supervision, except for guidance regarding subject recruitment, retention, and collection of research data.

d. Research Infrastructure

Part-time Study Directors and Research Assistants recruited subjects and performed on-site research assessments. All research personnel participated in training on goals and procedures. Subject attrition was minimized though (1) regular contact by the coordinating team with research staff to reinforce retention efforts and (2) a progressive reimbursement schedule for trial participants completing outcome assessments.

f. Trial Duration

Enrollment occurred between July 2010 and July 2012. Each subject was provided at least two years of treatment. There was no threshold for discontinuing patients, even after lengthy interruptions. Study assessments were suspended during periods of incarceration/hospitalization, but resumed after release/discharge. Subjects could continue research assessments even if they discontinued NAVIGATE or Community Care treatment. The last subject who entered completed 2-years in July 2014.

g. Assessment Strategy and Measures

Well-trained interviewers using live, two-way, video conferencing performed diagnostic interviews and assessments of symptoms and quality of life. Remote assessment via two-way video conferencing is comparable to face-to-face assessments in patient acceptability and reliability (22). Centralized assessors, who were masked to individual treatment assignments and overall study design, administered Structured Clinical Interviews for DSM-IV (SCID) (23) for diagnosis and duration of untreated psychosis; the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (24); the Clinical Global Impressions Severity Scale (25); the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (26); and the Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale (27), our primary outcome measure. The Quality of Life Scale has 21-items rated from a semi-structured interview. It covers areas such as: sense of purpose, motivation, emotional and social interactions, role functioning and engagement in regular activities. The SCID was completed at baseline and one-year; other measures every six months.

Site Research Assistants interviewed participants monthly to complete the Service Use and Resource Form (28,29) to capture participation in work or school, inpatient, residential, emergency, and outpatient mental health and medical services in the previous month, as well as self-reported days of alcohol/drug use. The Service Use and Resource Form includes questions concerning four specific NAVIGATE interventions, allowing treatment groups to be compared on receipt of key services. Time remaining in treatment was defined as the time from randomization to the time of the last mental health service received based upon the Service Use and Resource Form assessments.

h. Data Analysis

The analysis of the primary outcome (Total Quality of Life score) compared treatments over two years (baseline, 6, 12, 18 and 24 months). The analysis model was a three level mixed-effects linear regression model with a linearized term for time, an interaction of treatment group by linearized time, and a random intercept and a random slope for linearized time at both patient and site levels. To enhance analysis interpretability, time was linearized through square root or logarithmic transformation because outcome plots over time for both treatment groups showed greater improvement in the earlier months leveling off in the later months. The group by linearized time interaction was tested to assess the difference between treatments in the rate of Quality of Life Scale improvement. Alpha level for the analysis of the total Quality of Life Scale score was preset at 0.05.

Clustered, randomized trials typically have a limited number of clusters potentially resulting in imbalance between treatment groups on baseline measures that may confound the relationship between treatments and patient-level outcomes. A generalized linear mixed-effects regression model with a random effect (intercept) for site was used to identify baseline measures that were significantly different between the treatment groups. The identified baseline variables that were also significantly correlated with the Quality of Life Scale were included in the above model. The main effect of treatment would have been included had the baseline Quality of Life Scale been significantly different between the two treatment groups since the baseline Quality of Life Scale was modeled as part of the longitudinal response. A sensitivity analysis (available upon request) with no baseline covariate adjustment was also conducted based on the expectation of no significant baseline differences between treatment groups due to randomization.

In a further analysis, time was coded into dummy variables for categorical levels following baseline (6, 12, 18 and 24 months). An additional dummy variable for baseline time (time=0) would have been included had the baseline Quality of Life Scale been significantly different between the two treatment groups. Random effects for site and patient were also included. The same adjustment for potentially confounding baseline variables, as described above, was used. Interaction between treatment group and each of the dummy variables of time were tested to identify specific times at which there were significant differences between treatment groups.

In models with either linearized or categorical time the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) was used to compare independent, first order autoregressive (AR1), and unstructured (UN) covariance structures for repeated measures. Analyses of secondary outcomes, using a comparable approach, were conducted on subscales of the Quality of Life Scale and on measures of symptoms (PANSS Total Score and five factors (30), the Clinical Global Impressions Severity Scale and the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia). Service use analyses were based on a mixed-effects Poisson regression model with both site- and patient-level random effects. The same approach, as described above, was applied to the inclusion of baseline covariates and time transformation. We did not adjust for multiple comparisons in secondary outcomes analyses; such adjustment would risk increasing type II error which is of concern given the descriptive nature of the secondary analyses (31).

To evaluate the impact of duration of untreated psychosis as a moderator of treatment effectiveness, an additional fixed effect of duration of untreated psychosis (representing values below or above the median) and a three-way interaction of duration of untreated psychosis by linearized time and by a treatment indicator (referring to one of the treatment groups) were evaluated. This three-way interaction compared the slope of linearized time for patients in the indicated treatment group who were above and who were below the median duration of untreated psychosis. The median split approach was selected to maximize statistical power and optimize interpretability of findings. The moderating effect of duration of untreated psychosis was tested using the three-way interaction only after the significant difference in the rate of improvement between the two treatment groups was declared.

The two-year treatment effect-size was determined by the change from the baseline to two years using the estimates derived from the mixed model dividing by the pooled baseline standard deviation of the outcome measure -Cohen's d (32).

For each analysis, we checked the model assumptions and diagnostics including the normality assumption for random effects and the distribution of residuals.

Sample size calculations for mixed-effects linear regression analyses assumed that the intra class correlation (ICC) within subject would range from .30 to .60 and the ICC within site would be 0.10. With at least N=145 per group, even after attrition, the proposed design provided power in excess of 0.90 to detect an overall group difference and the difference in rate of change over time for a standardized effect size at the 24 month visit as small as 0.40 standard deviation units (9 Quality of Life scale points).

Results

Participant Characteristics

NAVIGATE and Community Care groups included 223 and 181 patients, respectively. Demographic and other baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. The mean age was 23 in both groups. The proportion of patients meeting schizophrenia-spectrum criteria were 90% for Community Care and 89% for NAVIGATE; the proportions for schizophrenia were 56% and 51%, respectively. Mean duration of untreated psychosis did not differ between groups; median duration was 74 weeks for both. Most patients (71% in both groups) lived with their families. Detailed descriptions of duration of untreated psychosis findings (33), baseline medication status/history (34) and baseline medical/metabolic measures (35) have been published elsewhere. NAVIGATE participants differed significantly from Community Care participants on four measures. NAVIGATE had significantly more males (77.6% vs. 66.2%; p=0.05); a smaller proportion with prior hospitalization (76.3% vs. 81.6%; p<0.05), worse PANSS total scores (p<0.02), and fewer attending school at baseline (16.0% vs. 26%; p<0.02).

Table 1.

Participant demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline

| Categorical Variables | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community Care (N = 181) | NAVIGATE (N = 223) | |||||||

| N | % | N | % | Unadjusted p-value1 | F test statistic2 | Degrees of freedom2 | p-value2 | |

| Male | 120 | 66 | 173 | 78 | 0.04 | 3.86 | 1, 370 | 0.05† |

| Race | 0.01 | 1.28 | 2, 336 | 0.28 | ||||

| White | 80 | 44 | 138 | 62 | ||||

| African American | 89 | 49 | 63 | 28 | ||||

| Other | 12 | 7 | 22 | 10 | ||||

| Hispanic ethnicity | 18 | 10 | 55 | 25 | 0.01 | 3.24 | 1, 370 | 0.07 |

| Marital status | 0.67 | 0.28 | 2, 336 | 0.76 | ||||

| Presently married | 10 | 6 | 14 | 6 | ||||

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 8 | 4 | 14 | 6 | ||||

| Never married | 163 | 90 | 195 | 87 | ||||

| Current residence | 0.97 | 0.08 | 3, 302 | 0.97 | ||||

| Independent living | 32 | 18 | 40 | 18 | ||||

| Supported or structured | 7 | 4 | 7 | 3 | ||||

| Family, parents, grandparents, sibling | 129 | 71 | 158 | 71 | ||||

| Homeless, shelter, or other | 13 | 7 | 18 | 8 | ||||

| Patient's education | 0.74 | 0.36 | 3, 301 | 0.78 | ||||

| Some college or higher | 54 | 30 | 71 | 32 | ||||

| Completed high school | 58 | 32 | 75 | 34 | ||||

| Some high school | 58 | 32 | 67 | 30 | ||||

| Some or completed grade school | 11 | 6 | 9 | 4 | ||||

| Mother's education | 0.17 | 1.06 | 3, 302 | 0.37 | ||||

| Some college or higher | 65 | 36 | 102 | 46 | ||||

| Completed high school | 51 | 28 | 60 | 27 | ||||

| Some high school or grade school | 32 | 18 | 27 | 12 | ||||

| No school or unknown | 33 | 18 | 34 | 15 | ||||

| Current student | 47 | 26 | 35 | 16 | 0.01 | 4.77 | 1, 370 | 0.03† |

| Currently working | 30 | 17 | 28 | 13 | 0.25 | 1.30 | 1, 370 | 0.25 |

| Type of insurance | 0.03 | 1.28 | 2, 333 | 0.28 | ||||

| Private | 27 | 15 | 55 | 25 | ||||

| Public | 66 | 37 | 61 | 27 | ||||

| Uninsured | 88 | 49 | 104 | 47 | ||||

| SCID diagnoses | 0.60 | 0.58 | 5, 234 | 0.72 | ||||

| Schizophrenia | 101 | 56 | 113 | 51 | ||||

| Schizoaffective bipolar | 13 | 7 | 11 | 5 | ||||

| Schizoaffective depressive | 25 | 14 | 32 | 14 | ||||

| Schizophreniform provisional or definite | 24 | 13 | 43 | 19 | ||||

| Brief psychotic disorder | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Psychotic disorder not otherwise specified | 17 | 9 | 23 | 10 | ||||

| Lifetime alcohol use | 0.08 | 2.49 | 2, 336 | 0.08 | ||||

| Did not meet criteria | 123 | 68 | 134 | 60 | ||||

| Met abuse criteria | 16 | 9 | 36 | 16 | ||||

| Met dependence criteria | 42 | 23 | 53 | 24 | ||||

| Lifetime cannabis use | 0.22 | 146 | 2, 336 | 0.23 | ||||

| Did not meet criteria | 123 | 68 | 137 | 61 | ||||

| Met abuse criteria | 21 | 12 | 39 | 18 | ||||

| Met dependence criteria | 37 | 20 | 47 | 21 | ||||

| Prescribed one or more antipsychotics at consent | 155 | 86 | 182 | 82 | 0.28 | 0.36 | 1, 370 | 0.55 |

| Number of prior hospitalizations | 0.01 | 3.91 | 1, 368 | 0.05† | ||||

| 0 | 34 | 19 | 54 | 24 | ||||

| 1 | 75 | 41 | 106 | 48 | ||||

| 2 | 32 | 18 | 37 | 17 | ||||

| 3 or more | 40 | 22 | 24 | 11 | ||||

| Continuous Variables | ||||||||

| Community Care (N = 181) | NAVIGATE (N = 223) | |||||||

| Mean | standard deviation | Mean | standard deviation | Unadjusted p-value | F test statistic | df | p-value* | |

| Age | 23.08 | 4.90 | 23.18 | 5.21 | 0.83 | 0.14 | 1, 370 | 0.71 |

| Duration of untreated psychosis (weeks) | 211.43 | 277.49 | 178.91 | 248.73 | 0.35^ | 0.97 | 1, 369 | 0.33 |

| Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale | ||||||||

| Total score | 54.77 | 18.99 | 50.89 | 18.44 | 0.04 | 2.70 | 1, 369 | 0.10 |

| Interpersonal relations | 20.07 | 8.53 | 19.51 | 8.84 | 0.52 | 0.51 | 1, 369 | 0.48 |

| Instrumental role | 6.82 | 6.86 | 4.54 | 6.07 | 0.01 | 7.51 | 1, 369 | 0.01 |

| Intrapsychic foundations | 21.39 | 7.29 | 20.36 | 6.69 | 0.14 | 1.60 | 1, 369 | 0.21 |

| Common objects and activities | 6.49 | 2.25 | 6.48 | 2.36 | 0.95 | 0.03 | 1, 369 | 0.86 |

| Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale | ||||||||

| Total score | 74.54 | 14.87 | 78.32 | 14.95 | 0.01 | 5.56 | 1, 369 | 0.02† |

| Factor Scores (30) | ||||||||

| Positive | 12.13 | 3.79 | 12.32 | 3.88 | 0.62 | 0.32 | 1, 369 | 0.57 |

| Negative | 16.34 | 4.96 | 16.98 | 5.34 | 0.22 | 0.80 | 1, 369 | 0.37 |

| Disorganized/concrete | 7.34 | 2.63 | 8.18 | 2.83 | 0.01 | 7.03 | 1, 369 | 0.01 |

| Excited | 6.38 | 2.30 | 7.05 | 3.06 | 0.02 | 5.83 | 1, 369 | 0.02 |

| Depressed | 7.93 | 3.42 | 8.16 | 3.22 | 0.49 | 0.34 | 1, 369 | 0.56 |

| Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia | 4.66 | 4.30 | 4.65 | 4.27 | 0.99 | 0.01 | 1, 369 | 0.99 |

| Clinical Global Impressions Severity Scale | 3.96 | 0.83 | 4.12 | 0.80 | 0.05 | 3.37 | 1, 369 | 0.07 |

| Duration of lifetime anti-psychotic medication at consent (days) | 48.46 | 48.98 | 40.60 | 42.88 | 0.13^ | 2.74 | 1, 369 | 0.10 |

not adjusting for cluster randomized design

adjusting for cluster randomized design

SCID = Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV.

p-values are based on a linear, negative binomial, logit or generalized logit mixed effects model to account for cluster-randomized design.

The variables marked † were included as covariates in the adjusted model in following analyses.

For the duration measures, the unadjusted p-values are of the Mann-Whitney U test.

Main Outcomes

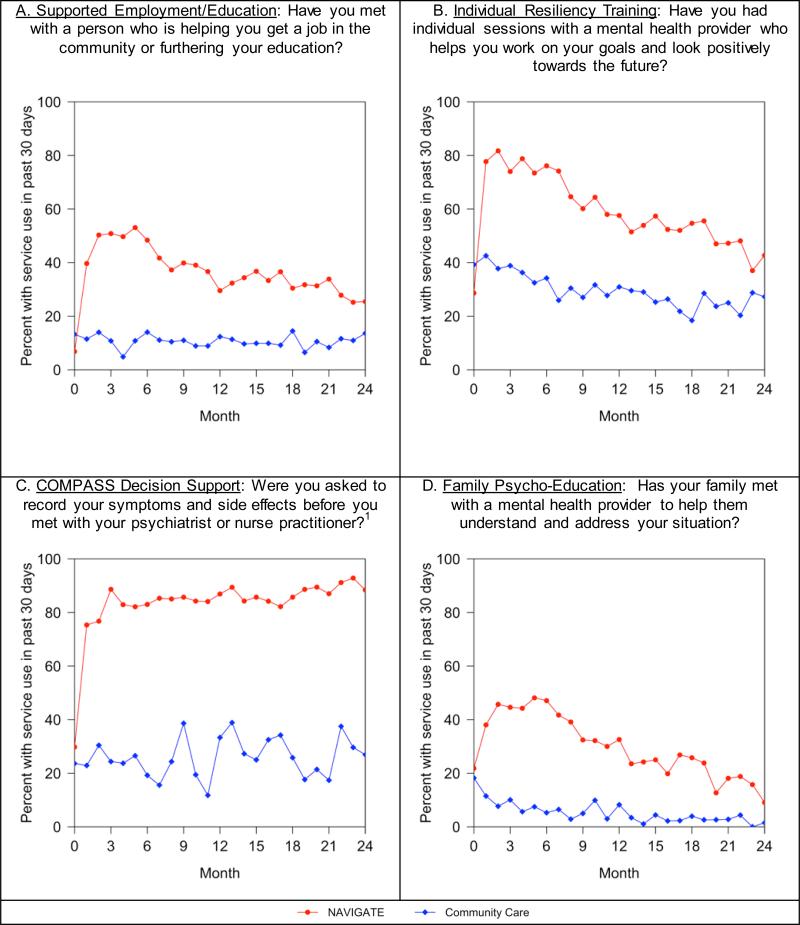

On a series of treatment validity measures, NAVIGATE participants were much more likely to endorse receipt of key services included in the experimental intervention than patients in Community Care (Figure 1; p<.0001 for each of the four services). Participants assigned to NAVIGATE remained in treatment longer than Community Care patients (median 23 months compared to 17 months, p<0.004; Supplemental Figure S2) and were more likely to have received mental health outpatient services each month than Community Care subjects (mean of 4.53 (standard deviation=5.07) versus 3.67 (standard deviation=5.93) services (t=2.49, p=0.013)).

Figure 1.

Patient self-report of use of NAVIGATE model targeted services during study period at NAVIGATE and Community Care Sites

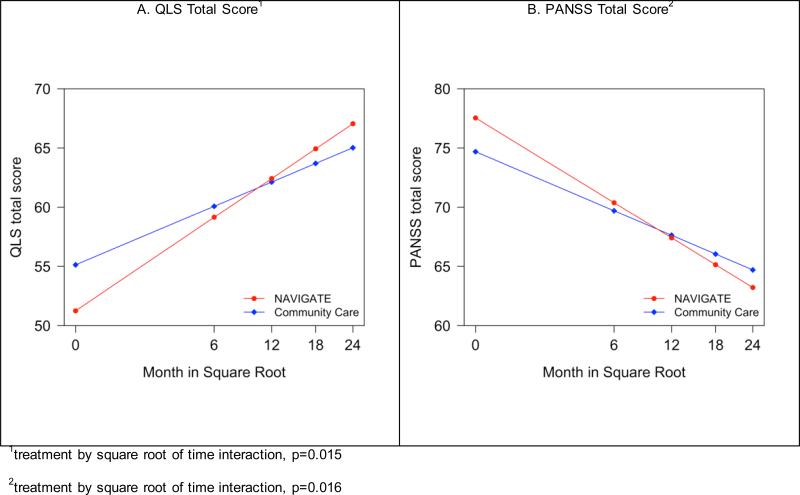

On the primary outcome measure, Quality of Life Scale total score; NAVIGATE participants experienced significantly greater improvement over the two year assessment period than those in Community Care (group by time interaction, p<0.02; Figure 2 and Tables 2 and S1), with an effect size of 0.31 and of a clinically meaningful magnitude (36). More improvement was also found on the subscales “interpersonal relations,” “intrapsychic foundations (i.e. sense of purpose, motivation, curiosity, and emotional engagement), and engagement with “common objects and activities”. Service Use and Resource Form data showed significantly greater gains for NAVIGATE regarding the proportion of participants who were either working or going to school at any time during each month (group by time interaction p<0.05; Supplemental Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Model-Based Estimates of Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life (QLS) Total Score and PANSS Total Score.

Table 2.

The estimated model-based change from baseline to 24 months and the differential change by treatment with effect size

| Change from baseline at 24 month | Differential change between CC and NAV at 24 month | Treatment by time interaction | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | Cohen's d | Mean | SE | Cohen's d | t | p-value | ||

| Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale | |||||||||

| Total scorea,b,c | CC | 9.891 | 1.918 | 0.53 | 5.902 | 2.408 | 0.31 | 2.45 | 0.0145 |

| NAV | 15.793 | 1.624 | 0.84 | ||||||

| Subscales | |||||||||

| Interpersonal relationsa,b,c | CC | 3.494 | 0.763 | 0.40 | 2.198 | 0.942 | 0.25 | 2.33 | 0.0199 |

| NAV | 5.691 | 0.635 | 0.65 | ||||||

| Instrumental rolea,b,c,e | CC | 3.418 | 0.801 | 0.52 | 1.854 | 1.059 | 0.28 | 1.75 | 0.0804 |

| NAV | 5.271 | 0.692 | 0.81 | ||||||

| Intrapsychic foundations,a,b,c | CC | 2.144 | 0.616 | 0.31 | 1.548 | 0.744 | 0.22 | 2.08 | 0.0377 |

| NAV | 3.692 | 0.510 | 0.53 | ||||||

| Common objects and activitiesa,b,c | CC | 0.971 | 0.184 | 0.42 | 0.483 | 0.221 | 0.21 | 2.18 | 0.0294 |

| NAV | 1.453 | 0.151 | 0.63 | ||||||

| Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale | |||||||||

| Total scorea,b,e | CC | −9.989 | 1.383 | −0.67 | −4.324 | 1.792 | −0.29 | −2.41 | 0.0161 |

| NAV | −14.313 | 1.140 | −0.95 | ||||||

| Factor scores (30) | |||||||||

| Positivea.b.e | CC | −2.519 | 0.385 | −0.66 | −0.224 | 0.502 | −0.06 | −0.45 | 0.6560 |

| NAV | −2.742 | 0.322 | −0.72 | ||||||

| Negativea,b,e | CC | −2.280 | 0.530 | −0.44 | −0.693 | 0.680 | −0.13 | −1.02 | 0.3087 |

| NAV | −2.972 | 0.426 | −0.57 | ||||||

| Disorganized/concretea,b,e | CC | −0.721 | 0.294 | −0.26 | −0.685 | 0.391 | −0.25 | −1.75 | 0.0804 |

| NAV | −1.406 | 0.258 | −0.51 | ||||||

| Exciteda,b,e | CC | −0.241 | 0.305 | −0.09 | −0.703 | 0.404 | −0.25 | −1.74 | 0.0823 |

| NAV | −0.944 | 0.265 | −0.34 | ||||||

| Depresseda,b,e | CC | −0.893 | 0.290 | −0.27 | −0.770 | 0.375 | −0.23 | −2.05 | 0.0407 |

| NAV | −1.662 | 0.239 | −0.50 | ||||||

| Clinical Global Impressions Severity Scale c | CC | −0.606 | 0.079 | −0.74 | −0.140 | 0.092 | −0.17 | −1.52 | 0.1292 |

| NAV | −0.746 | 0.066 | −0.91 | ||||||

| Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia a,c | CC | −1.196 | 0.327 | −0.28 | −0.785 | 0.365 | −0.18 | −2.15 | 0.0318 |

| NAV | −1.981 | 0.277 | −0.46 | ||||||

CC = Community Care; NAV = NAVIGATE. These means are based on a linear mixed effects model with random intercepts and slopes at the individual and site level with repeated measures.

In addition to the interaction of square root of time by treatment, models included co-variates of gender

student status

PANSS

d number of prior hospitalizations (0, 1, 2, 3 or more)

and/or main treatment effect as indicated.

NAVIGATE participants experienced greater improvement on PANSS total scores (p<0.02), the PANSS depressive factor (p<0.05), and the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (p<0.04) between baseline and 24 months. There were no significant group differences on the CGI.

The average rate of hospitalization was 3.2%/month for NAVIGATE and 3.7%/month for Community Care. Over the two years, 34% of the NAVIGATE group and 37% in the Community Care group (adjusted for length of exposure) had been hospitalized for psychiatric indications (p=NS).

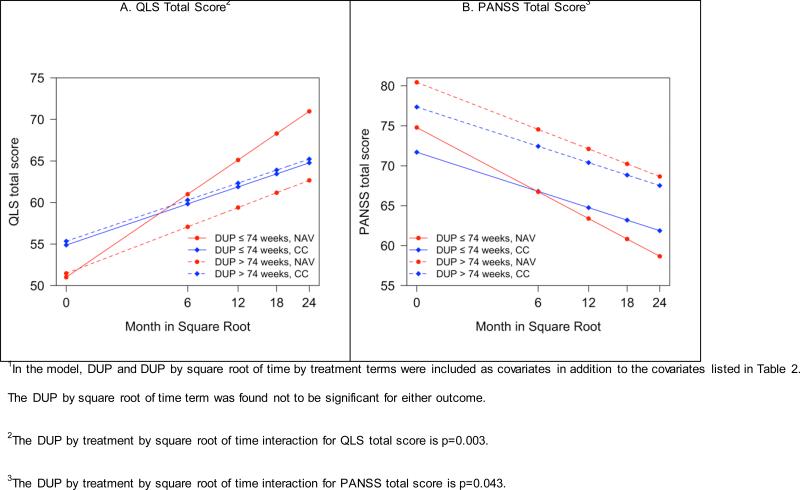

Moderating Effect of Duration of Untreated Psychosis

Median duration of untreated psychosis was a significant moderator of the treatment effect on total Quality of Life Scale and PANSS scores over time (Figure 3; Supplemental Table 2). The difference in effect sizes comparing change between treatments with participants with duration of untreated psychosis ≤ 74 weeks and those with duration of untreated psychosis > 74 weeks was substantial: 0.54 versus 0.07 for Quality of Life Scale and 0.42 versus 0.13 for PANSS scores.

Figure 3.

Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life (QLS) Total Score and PANSS Total Score: Effects of Shorter vs. Longer Duration of Untreated Psychosis (DUP) based on a model with square root transformation of months1.

Discussion

RAISE-ETP accomplished the primary goals of the NIMH RAISE initiative. We developed a comprehensive recovery-oriented, evidence-based intervention for first episode psychosis (20), trained over 100 community providers in early intervention principles and to deliver manual-based, coordinated specialty care, and successfully implemented the NAVIGATE model in 17 real world community clinics serving a racially and ethnically heterogeneous patient mix. NAVIGATE programs operated continuously between 2010 and 2014, demonstrating sustained model implementation. RAISE-ETP is the first multi-site, randomized, controlled trial of coordinated specialty care conducted in the United States, and the first anywhere to simultaneously include all of the following elements: randomized concurrent controls; masked assessment of primary and secondary outcomes; manual driven intervention with ongoing training and fidelity metrics. Most importantly, NAVIGATE improved outcomes for patients over 24 months; with effects seen on length of time in treatment, quality of life, participation in work and school, and symptoms - outcomes of importance to service users, family members, and clinicians.

Our results are likely to generalize to many U.S. community care settings that wish to implement specialty care teams for young persons with first episode psychosis. Insurance covered some NAVIGATE services (i.e., individual and family therapy, medication management), but supplements are needed to make first-episode services viable (37). Congress recently allocated additional funds to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) to subsidize first episode psychosis services not covered by insurance, like assertive outreach, care coordination, and supported employment/education (38,39). Since 2014, 32 states have moved toward earlier intervention by combining SAMHSA funds with services reimbursed by public or private insurance, and in some cases with increased state funding for first episode psychosis programs.

Three multi-element treatment studies have been conducted outside the U.S., although only one (14,15) included exclusively first episode psychosis patients. The Lambeth Early Onset (LEO) study (12,13,40) randomly allocated 144 patients in London with a first or second psychotic episode to “specialist services” or “care as usual” for 18 months. Patients had a median age of 25, 24% were Caucasian, 58% were living with family. Data on duration of untreated psychosis were not provided. Individuals receiving specialist services had fewer readmissions (but were not less likely to have ever been readmitted or to have shorter admissions) and better social and vocational functioning, quality of life and medication adherence. At follow up, only 58% of participants had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizotypal or delusional disorder.

In the Danish OPUS study (14,15) 547 first episode psychosis patients with <12 weeks exposure to antipsychotic medications were randomly assigned to “integrated” or “standard” treatment. The sample differed from ours in being 3 years older on average and with 78% living alone or with a partner. The only data reported on duration of untreated psychosis was a median of <50 weeks. At two-year follow up, the integrated treatment group was more likely to have remained in treatment and had significantly lower levels of psychotic and negative symptoms, but there was no difference in mean number of days spent in hospital. The proportion of patients hospitalized was 59% in year 1 and 26% in year 2 among patients receiving integrated care. With standard care, the respective rates were 71% and 39%. Differences were significant during year 1 but not during year 2. Of note, overall hospitalization rates in both groups were considerably higher than in our study. Patients in integrated care experienced significantly less substance misuse, better adherence and more satisfaction with care. Neither LEO nor OPUS included formal SEE, a robust evidence-based practice, which emphasizes further that these studies are not identical.

Grawe et al (41) studied 50 patients with less than two years illness duration and most diagnosed schizophrenia, but not necessarily first episode. At two years, hospitalization rates were 33% in the enhanced intervention group and 50% among controls (difference not significant). Although individual outcomes did not differ, the percent of participants having a good outcome based upon a “Clinical Composite Index” was significantly higher in the intervention group (53% versus 25%).

In the US, Srihari and colleagues (16) randomly assigned 120 first episode psychosis patients with <12 weeks antipsychotic medication exposure to the Specialized Treatment Early in Psychosis (STEP) program at an academic community mental health center or usual care in the community. The mean duration of untreated psychosis was 40 weeks. Assessments were not masked. After one year of participation, STEP compared with usual care recipients experienced significantly greater reductions in symptoms, required less inpatient care (hospitalization rates were 23% versus 44%), and were more likely to be working or going to school. Neither quality of life nor social functioning differed between treatments.

Given NAVIGATE's effect on treatment retention, quality of life, and symptom improvement, we expected a larger difference between treatment conditions in post-enrollment hospitalization. However, the 34% rate for NAVIGATE is comparable to hospitalization rates for integrated treatment programs in the four prior multi-component first episode psychosis intervention studies (23%-59%). Post-enrollment hospitalization rates for standard care in these studies (44%-71%) were uniformly higher than that in Community Care (37%). All sites randomized to Community Care had expressed eagerness to participate in RAISE-ETP and had the staff, administrative support and desire to implement a coordinated specialty care program. Hence, Community Care sites may have had the motivation and resources available to serve clients with first episode psychosis, resulting in lower hospitalization rates compared to unselected community sites.

The observation that patients with shorter duration of untreated psychosis derived substantially more benefit from NAVIGATE is important. Prolonged duration of untreated psychosis is an issue of national importance; reducing duration of untreated psychosis from current levels of >1 year to the recommended standard of <3 months (42) should be a major focus of applied research efforts.

A key question is the sustained benefit of comprehensive specialty care programs. The long-term OPUS trial outcomes suggest that the benefits of participation in a two-year intensive early intervention program do not persist in a five-year follow-up (43). It is also possible, as suggested by Linszen et al. (6), that the positive effects of intensive early treatment are only sustained when patients continue to receive specialized services. The length of time subjects were eligible to receive NAVIGATE services after the completion of 2 year period that is the focus of this report varied. An ongoing follow-up study will extend outcome assessment for a total of 5 years to provide information on longer-term effects and optimal treatment duration.

Conclusions

The RAISE-ETP study demonstrates that diverse U.S. community clinics can implement a team-based model of first episode psychosis care, producing greater improvement in clinical and functional outcomes as compared to standard care. These effects were more pronounced for those with shorter duration of untreated psychosis, suggesting that the receipt of appropriate first episode psychosis treatment at the proper time in the illness course can have a substantial impact on outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work has been funded in whole or in part with funds from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act and the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract No. HHSN271200900019C.

Additional support for these analyses was provided by an ACISR award (P30MH090590; PI: Dr. Kane) also from NIMH.

We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of our collaborating partner MedAvante for the conduct of the centralized diagnostic interviews and assessments. Without their involvement this study would not have been possible. We appreciate the efforts of the team at the Nathan Kline Institute for data management. Thomas Ten Have and Andrew Leon played key roles in the design of the study, particularly for the statistical analysis plan. We mourn the untimely deaths of both. Robert Gibbons and Donald Hedekker provided insightful consultation on data analysis. We thank all of our core collaborators and consultants for their invaluable contributions.

We are indebted to the many clinicians, research assistants and administrators at the participating sites for their enthusiasm and terrific work on the project as well as the participation of the hundreds of patients and families who made the study possible with their time, trust and commitment.

The participating sites are listed below:

Burrell Behavioral Health (Columbia), Burrell Behavioral Health (Springfield), Catholic Social Services of Washtenaw County, Center for Rural and Community Behavior Health New Mexico, Cherry Street Health Services, Clinton-Eaton-Ingham Community Mental Health Authority, Cobb County Community Services Board, Community Alternatives, Community Mental Health Center of Lancaster County, Community Mental Health Center, Inc., Eyerly Ball Iowa, Grady Health Systems, Henderson Mental Health Center, Howard Center, Human Development Center, Lehigh Valley Hospital, Life Management Center of Northwest Florida, Mental Health Center of Denver, Mental Health Center of Greater Manchester, Nashua Mental Health, North Point Health and Wellness, Park Center, PeaceHealth Oregon/Lane County Behavioral Health Services, Pine Belt Mental HC, River Parish Mental Health Center, Providence Center, San Fernando Mental Health Center, Santa Clarita Mental Health Center, South Shore Mental Health Center, St. Clare's Hospital, Staten Island University Hospital, Terrebonne Mental Health Center, United Services and University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Pharmacy.

Footnotes

Previous Presentation:

Partial data were presented at the 9th International Congress on Early Psychosis, Tokyo, Japan, November 17-19, 2014, the International Congress on Schizophrenia Research, Colorado Springs, Colorado, March 28-April 1, 2015, and the National Council for Behavioral Health Conference, Orlando, FL April 20-22, 2015.

Disclaimers:

The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of National Institute of Mental Health or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Disclosures:

Dr. Kane has been a consultant for Alkermes, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, EnVivo Pharmaceuticals (Forum), Forest, Genentech, H. Lundbeck. Intracellular Therapies, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Johnson and Johnson, Merck, Novartis, Otsuka, Pierre Fabre, Reviva, Roche, Sunovion and Teva. Dr. Kane has received honoraria for lectures from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Genentech, Lundbeck and Otsuka. Dr. Kane is a Shareholder in MedAvante, Inc. and the Vanguard Research Group. Dr. Robinson has been a consultant to Asubio, Shire and Otsuka, and he has received grants from Bristol Meyers Squibb, Janssen, and Otsuka. Dr. Schooler has served on Advisory Boards or as a consultant for Abbott, Alkermes, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Forum (formerly EnVivo), Janssen Psychiatry, Roche, Sunovion. She has received grant/research support from Neurocrine, Genentech and Otsuka. She served on a Data Monitoring Board for Shire and on the faculty of the Lundbeck International Neuroscience Foundation. Dr. Brunette has received grant support from Alkermes. Dr. Correll has been a consultant and/or advisor to or has received honoraria from AbbVie, Actavis, Actelion, Alexza; Alkermes, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, Eli Lilly, Genentech, Gerson Lehrman Group, IntraCellular Therapies, Janssen/J&J, Lundbeck, Medavante, Medscape, Merck, Otsuka, Pfizer, ProPhase, Reviva, Roche, Sunovion, Supernus, Takeda, Teva, and Vanda. He has received grant support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen/J&J, Novo Nordisk A/S, Otsuka and Takeda. Ms. Marcy is a shareholder in Pfizer. Mr. Robinson has received grant support from Otsuka and is a shareholder in Pfizer. Dr. Kurian has received grant support from Targacept, Pfizer, Johnson and Johnson, Evotec, Rexahn, Naurex, and Forest. Dr. Miller has received payments for service on a Data Monitoring Committee for a study sponsored by Otsuka.

The authors and their associates provide training and consultation about implementing NAVIGATE treatment that can include compensation. These activities started only after data collection for the manuscript was completed. As of the time of publication, authors Meyer-Kalos, Glynn and Robinson had received compensation for these activities.

Dr. Mueser, Dr. Penn, Dr. Rosenheck, Dr. Addington, Dr. Estroff, Dr. Gottlieb, Mr. Lynde, Mr. Pipes, Dr. Azrin, Dr. Goldstein, Ms. Severe, Dr. Lin, Mr. Sint, Dr. John and Dr. Heinssen have no financial interests to disclose.

Clinical Trials registration: NCT01321177: An Integrated Program for the Treatment of First Episode of Psychosis (RAISE ETP), http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01321177

References

- 1.Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ. Global Burden of Disease and Risk Factors. World Bank; Washington, DC: 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jaaskelainen E, Juola R, Hirvonen N, McGrath JJ, Saha S, Isohanni M, Veijola J, Miettunen J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of recovery in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(6):1296–306. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bird V, Premkumar P, Kendall T, Whittington C, Mitchell J, Kuipers E. Early intervention services, cognitive-behavior therapy and family intervention in early psychosis: systematic review. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;197(5):350–356. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.074526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alvarez-Jimenez M, Parker AG, Hetrick SE, McGorry PD, Gleeson JF. Preventing the second episode: A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial and pharmacological trials in first-episode psychosis. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2011;37(3):619–630. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Addington J. The promise of early intervention. Early Intervention in Psychiatry. 2007;1(4):294–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2007.00043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linszen D, Dingemans P, Lenoir M. Early intervention and a five year follow up in young adults with a short duration of untreated psychosis: ethical implications. Schizophrenia Research. 2001;51:55–61. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00239-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cullberg J, Levander S, Holmqvist R, et al. One-year outcome in first episode psychosis patients in the Swedish Parachute project. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2002;106:276–85. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.02376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGorry PD, Jackson HJ, editors. Recognition and Management of Early Psychosis: A Preventive Approach. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ventura J, Subotnik K, Guzik L, Hellemann G, Gitlin M, Wood R, Nuechterlein K. Remission and Recovery During the First Outpatient Year of the Early Course of Schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2011;132:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uzenoff S, Penn D, Graham K, Saade S, Smith B, Perkins D. Evaluation of a Multi-Element Treatment Center for Early Psychosis in the United States. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00127-011-0467-4. DOI 10.1007/s00127-011-0467-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bertolote J, McGorry P. Early intervention and recovery for young people with early psychosis: consensus statement. Br J Psychiatry. Suppl. 2005;48:s116–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.48.s116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Craig TK, Garety P, Power P, Rahaman N, Colbert S, Fornells-Ambrojo M, Dunn G. The Lambeth Early Onset (LEO) Team: randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of specialised care for early psychosis. Brit Med J. 2004;6329(7474):1067. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38246.594873.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garety PA, Craig TK, Dunn G, Fornells-Ambrojo M, Colbert S, Rahaman N, Read J, Power P. Specialised care for early psychosis: symptoms, social functioning and patient satisfaction: randomized controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2006 Jan;188:37–45. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.104.007286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thorup A, Petersen L, Jeppesen P, Ohlenschlaeger J, Christensen T, Krarup G, Jørgensen P, Nordentoft M. Integrated treatment ameliorates negative symptoms in first episode psychosis--results from the Danish OPUS trial. Schizophr Res. 2005 Nov 1;79(1):95–105. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petersen L, Jeppesen P, Thorup A, Abel MB, Øhlenschlaeger J, Christensen TØ, Krarup G, Jørgensen P, Nordentoft M. A randomised multicentre trial of integrated versus standard treatment for patients with a first episode of psychotic illness. Brit Med J. 2005;17331(7517):602. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38565.415000.E01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Srihari VH, Tek C, Kucukgoncu S, et al. First-episode service for psychotic disorders in the U.D. Public Sector: A pragmatic, randomized control trial. Psychiatr Serv. 2015 Feb 2;:appips201400236. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kane JM, Schooler NR, Marcy P, Correll CU, Brunette MF, Mueser KT, Rosenheck RA, Addington J, Estroff SE, Robinson R, Penn DL, Robinson DG. The RAISE Early Treatment Program for First Episode Psychosis: Background, Rationale and Study Design. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(3):240–6. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV [Internet] 4th ed. American Psychiatric Association; Washington (DC): 1994. [2010 Mar 8]. 866 p. Available from: http://www.psychiatryonline.com/DSMPDF/dsm-iv.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donner A, Klar N. Design and Analysis of Cluster Randomization Trials in Health Research. 1 edition. Wiley; Chichester: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mueser K, Penn D, Addington J, et al. The NAVIGATE program for first episode psychosis: Rational, overview and description of psychosocial components. Psychiatr Serv. 2015 Mar 16; doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Godolphin W. Shared decision-making. Healthcare Quarterly. 2009;12(Special Issue):p186–90. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2009.20947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zarate CA, Jr., et al. Applicabilityof telemedicine for assessing patients with schizophrenia: acceptance and reliability. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(1):22–5. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v58n0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV® Axis I Disorders (SCID-I), Clinician Version, Administration Booklet. American Psychiatric Pub. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guy W. ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology, revised (DHEW Publ No ADM 76-338) National Institute of Mental Health; Rockville, MD: 1976. Clinical Global Impressions. pp. 218–222. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Addington D, Addington J, Maticka-Tyndale E. Assessing depression in schizophrenia: The Calgary Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;163(Suppl 22):39–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heinrichs DW, Hanlon TE, Carpenter Jr WT. The Quality of Life Scale An Instrument for Rating the Schizophrenic Deficit Syndrome. Schizophr Bull. 1984;10(3):388–398. doi: 10.1093/schbul/10.3.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenheck RA, Leslie DL, Sindelar J, Miller EA, Lin H, Stroup TS, McEvoy J, Davis SM, Keefe RSE, Swartz M, Perkins DO, Hsiao JK, Lieberman J. Cost effectiveness of second-generation antipsychotics and perphenazine in a randomized trial of treatment for chronic schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:2080–2089. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.12.2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenheck RA, Resnick SG, Morrissey JP. Closing service system gaps for homeless clients with a dual diagnosis: integrated teams and interagency cooperation. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2003;6(2):77–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wallwork RS, Fortgang R, Hashimoto R, Weinberger DR, Dickinson D. Searching for a consensus five-factor model of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012 May;137(1-3):246–50. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rothman KJ. No adjustments are needed for multiple comparisons. Epidemiology. 1990 Jan;1(1):43–6. PubMed PMID: 2081237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen Jacob. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; New Jersey: 1988. ISBN 0-8058-0283-5. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Addington J, Heinssen RK, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, Marcy P, Brunette MF, Correll CU, Estroff S, Mueser KT, Penn D, Robinson JA, Rosenheck RA, Azrin ST, Goldstein AB, Severe J, Kane JM. Duration of Untreated Psychosis in Community Treatment Settings in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;15:appips201400124. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400124. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robinson DG, Schooler NR, John M, Correll CU, Marcy P, Addington J, Brunette MF, Estroff SE, Mueser KT, Penn D, Robinson J, Rosenheck RA, Severe J, Goldstein A, Azrin S, Heinssen R, Kane JM. Medication Prescription Practices for the Treatment of First Episode Schizophrenia-Spectrum Disorders: Data from the National RAISE-ETP Study. Amer J Psychiatry. 2015;172(3):237–248. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13101355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Correll CU, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, Brunette MF, Mueser KT, Rosenheck RA, Marcy P, Addington J, Estroff SE, Robinson J, Penn D, Azrin S, Goldstein A, Severe J, Heinssen R, Kane JM. Cardiometabolic Risk in First Episode Schizophrenia-Spectrum Disorder Patients: Baseline Results from the RAISE-ETP study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(12):1350–1363. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Falissard B, Sapin C, Loze JY, Landsberg W, Hansen K. Defining the Minimal Clinically Important Difference of the Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale (QLS). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2015 doi: 10.1002/mpr.1483. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goldman HH1, Karakus M, Frey W, Beronio K. Economic grand rounds: Financing first-episode psychosis services in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2013 Jun;64(6):506–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300106. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300106.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.U.S. Congress. (2013 - 2014). Consolidated Appropriations Act. Congress.Gov.; 2014. https://www.congress.gov/bill/113th-congress/house-bill/3547. [Google Scholar]

- 39.U.S. Congress. (2013 - 2014). Consolidated and Further Continuing Appropriations Act. Congress.Gov.; 2015. https://www.congress.gov/bill/113th-congress/house-bill/83. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gafoor R, Nitsch D, McCrone P, Craig TK, Garety PA, Power P, McGuire P. Effect of early intervention on 5-year outcome in non-affective psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(5):372–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.066050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grawe RW, Falloon IR, Widen JH, Skogvoll E. Two years of continued early treatment for recent-onset schizophrenia: a randomised controlled study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;114(5):328–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bertolote J, McGorry P. Early intervention and recovery for young people with early psychosis: consensus statement. British Journal of Psychiatry Supplement. 2005;48:s116–s119. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.48.s116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bertelsen M, Jeppesen P, Petersen L, Thorup A, Ohlenschlaeger J, le Quach P, Christensen TO, Krarup G, Jorgensen P, Nordentoft M. Five-year follow-up of a randomized multicenter trial of intensive early intervention vs standard treatment for patients with a first episode of psychotic illness: The OPUS trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(7):762–771. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.7.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.