Abstract

Autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is a treatment option for many patients diagnosed with lymphoma. The effects of patient-specific factors on outcomes after autologous HCT are not well characterized. Here, we studied a sequential cohort of 754 patients with lymphoma treated with autologous HCT between 2000 and 2010. In multivariate analysis, patient-specific factors that were statistically significantly associated with non-relapse mortality (NRM) included hematopoietic cell transplantation comorbidity index (HCT-CI) scores of ≥ 3 (hazard ratio [HR] 1.94, P = 0.05), a history of alcohol use disorder (AUD) (HR 2.17, P = 0.004), and older age stratified by decade (HR 1.29, P = 0.02). HCT-CI ≥ 3, a history of AUD, and age > 50 were combined into a composite risk model: non-relapse and overall mortality rates at 5 years increased from 6% to 30% and 32% to 58%, respectively, in patients with zero versus all 3 risk factors. The HCT-CI is a valid tool in predicting mortality risks after autologous HCT for lymphoma. AUD and older age exert independent prognostic impact on outcomes. Whether AUD indicates additional organ dysfunction or socio-behavioral abnormality warrants further investigation. The composite model may improve risk-stratification prior to autologous HCT.

Keywords: lymphoma, autologous, transplant, HCT-CI, alcohol

Introduction

High dose therapy followed by autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) can achieve long-term remission and, in certain settings, cure patients with lymphoma. Lymphoma-specific factors such as disease status and prior treatments are known to affect non-relapse mortality (NRM) and overall mortality (OM) after autologous HCT [1]. Whether patient-specific factors can contribute to prediction of outcomes after autologous SCT is not well characterized and there is currently no consensus for including these variables in risk-assessment stratification.

The HCT-specific comorbidity index (HCT-CI) was designed to stratify the risk of NRM in patients undergoing allogeneic HCT for hematologic malignancies [2–4] by synthesizing an array of comorbidities weighted according to diagnosis and severity. A limited number of studies have applied the HCT-CI to relapse-free outcomes after autologous HCT [5–8] and fewer still have examined this tool in patients with lymphoma [5, 7, 8].

The HCT-CI incorporates measurements of patient organ function, presence of comorbid medical conditions including active infection and a history of separate malignancy, and, to a limited extent, psychiatric disease. Elements of the psycho-social domain including substance abuse are not directly captured. Here, we asked whether 1) the HCT-CI is valid in predicting mortality risks after autologous HCT for lymphoma and 2) the index could be augmented by other patient-specific risk factors to design a composite model for decision-making. To this end, we retrospectively analyzed outcomes in a large, sequential cohort of 754 patients with lymphoma treated with autologous HCT between 2000 and 2010.

Materials and Methods

Study cohort

The study cohort included all patients with lymphoma that underwent autologous HCT at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (FHCRC) and the Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS) between 2000 and 2010 (N = 817). Data were collected from comprehensive medical record review and institutional databases. Patients given a planned tandem autologous-allogeneic HCT (N = 37), given a planned tandem autologous-autologous HCT (N = 22), or diagnosed with Burkitt’s lymphoma (N = 4) were excluded from analysis yielding a final total sample of 754 patients. The Institutional Review Boards (IRB) of both FHCRC and the VAPSHCS approved data collection and analysis for patients treated at their respective facilities.

Treatment and definitions

The HCT conditioning regimens were determined by each individual patient’s treatment team with consideration of age, comorbidities, diagnosis, remission status, and prior therapies. Conditioning regimens that consisted of only chemotherapy included busulfan, melphalan, and thiotepa (BuMELT) or carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan (BEAM), with or without rituximab. Total body irradiation (TBI) based regimens included TBI combined with cyclophosphamide with or without etoposide. High-dose radiolabeled antibody (RAB) based regimens consisted of iodine-131-labeled anti-CD20 antibodies either alone or in combination with cyclophosphamide and etoposide or combined with escalating doses of fludarabine.

HCT-CI scores were calculated by two investigators (J.E.V. scored 433 patients; M.L.S. scored 321 patients) according to previously published criteria [2, 9]. Inter-rater reliability was evaluated using weighted kappa statistic estimates (Kw) [10] with standard errors (SE) as previously described [9]. In a sample of 32 patients, there was consistent agreement between evaluators with Kw estimate of 0.88 (SE 0.06).

Response to chemotherapy was defined as chemo-sensitive if a complete remission (CR) or a partial remission (PR) had been achieved in response to last salvage therapy given prior to autologous HCT according to standard criteria [11, 12]. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) values were recorded and scored as normal or elevated (above the upper limit of normal) according to the respective institutions’ laboratory standards. Classification of alcohol use disorders (AUD) was performed according to standard criteria, and included self-identification as a current or past alcoholic, engaging in current or prior “heavy” or “binge” drinking, convictions for alcohol related crimes, or history of rehabilitation for alcoholism [13]. This classification was done retrospectively through comprehensive review of available medical records.

Statistical methods

Patient characteristics and causes of death were compared using a Fisher’s exact test where applicable. Cumulative incidence of NRM was estimated by standard methods [14], with relapse of lymphoma treated as a competing risk. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of autologous HCT using Kaplan-Meier estimates.

Patient-, lymphoma-, and treatment- specific factors were assessed for associations with NRM in univariate analysis. Age was stratified by decade. All factors with a P-value of < 0.1 were entered into a Cox proportional hazard regression model stratified by the institution at which the autologous HCT was performed. Two-sided P-values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Patient-specific factors that affected NRM after multivariate analysis were added to generate a composite risk factor score. The multivariate analysis considered age stratified by decade; to fit age into the composite risk factor model the variable was dichotomized and a cutoff of > 50 was selected based on optimal separation of outcomes comparing different age cut-off values. The discriminative capacity of age (stratified by decade), AUD, HCT-CI, and the composite model for NRM was evaluated using c-statistic estimates [15].

Results

Patient characteristics

Seven-hundred fifty-four patients met the above criteria and were evaluated in this study with a median follow-up period of 3.0 years (range, 0.1 – 13 years). Patient-specific characteristics are tabulated in Table 1; characteristics specific to lymphoma and treatment are shown in Supplementary Table S1. The median age at autologous HCT was 53 years (range 18 – 78). The majority of patients were Caucasian (86%), married (69%), never-smokers (55%), and, at the time of evaluation for autologous HCT, were active consumers of alcohol at least occasionally (56%). Eighty-one (11%) patients had a history of AUD. The median HCT-CI was 1 (range 0 – 9), with 44% of patients having a HCT-CI ≥ 3.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of study cohort

| Patient-specific factors (N = 754) | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Median (range) | 53 (18 – 78) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 516 (68) |

| Female | 238 (32) |

| Race | |

| White | 583 (86) |

| Other | 93 (14) |

| Unknown | 78 |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 512 (69) |

| Other | 230 (31) |

| Unknown | 12 |

| Tobacco use | |

| Never smoker | 418 (55) |

| Former smoker | 229 (30) |

| Current smoker1 | 105 (14) |

| Unknown | 2 |

| Tobacco quantity (smokers only) | 334 (100) |

| < 15 pack-years | 80 (32) |

| 15 – 30 pack-years | 74 (31) |

| ≥ 30 pack-years | 95 (40) |

| Unknown | 85 |

| Alcohol use | |

| No current use | 332 (44) |

| Current use1 | 422 (56) |

| No AUD | 673 (89) |

| AUD | 81 (11) |

| HCT-CI | |

| Median (range) | 1 (0 – 9) |

| 0 | 151 (20) |

| 1–2 | 274 (36) |

| ≥ 3 | 328 (44) |

| LDH | |

| Normal | 495 (67) |

| Elevated | 247 (33) |

| Unknown | 12 |

AUD, alcohol use disorder; HCT-CI, hematopoietic cell transplantation comorbidity index; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

At time of HCT intake.

Non-relapse mortality and its predictive factors

Direct unadjusted comparison of NRM among subgroups identified three patient-specific factors that associated with worse outcomes (Table 2): HCT-CI ≥ 3 (HR 2.38; CI 1.3 – 4.5, P = 0.007), AUD (HR 2.85; CI 1.7 – 4.7, P < 0.0001), and age (HR 1.27; CI 1.0 – 1.5, P = 0.01). Race, marital status, use of alcohol concurrent with autologous HCT, and smoking status had no statistically significant correlation with NRM. A history of heavy smoking, quantified as more than 30 total pack-years, showed some suggestion of association with NRM (HR 1.57; CI 0.9 – 2.8, P = 0.12) but did not meet significance statistically.

Table 2.

Univariate analysis showing association of patient-specific factors with non-relapse mortality in patients that underwent autologous HCT for lymphoma.

| Non-relapse mortality | ||

|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age | ||

| Per decade | 1.27 (1.0 – 1.5) | 0.01 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 0.90 (0.6 – 1.4) | 0.66 |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 1.0 | |

| Other | 1.32 (0.7–2.4) | 0.37 |

| Unknown | 1.46 (0.8–2.6) | 0.20 |

| Marital status | ||

| Other | 1.0 | |

| Married | 1.03 (0.7–1.6) | 0.90 |

| Smoking status | ||

| Never | 1.0 | |

| Former | 1.04 (0.6–1.7) | 0.86 |

| Current | 1.48 (0.8–2.6) | 0.18 |

| Smoking pack-years | ||

| Never | 1.0 | |

| < 15 | 0.96 (0.5–2.0) | 0.92 |

| 15–29 | 1.02 (0.5–2.2) | 0.96 |

| 30+ | 1.57 (0.9–2.8) | 0.12 |

| Unknown | 1.07 (0.5–2.1) | 0.84 |

| AUD | ||

| No | 1.0 | |

| Yes | 2.85 (1.7–4.7) | <0.0001 |

| Current alcohol use | ||

| No | 1.0 | |

| Use | 0.87 (0.6–1.3) | 0.51 |

| HCT-CI | ||

| 0 | 1.0 | |

| 1–2 | 1.29 (0.7–2.6) | 0.46 |

| ≥ 3 | 2.38 (1.3–4.5) | 0.007 |

| LDH > ULN | ||

| No | 1.0 | |

| Yes | 1.37 (0.9–2.1) | 0.17 |

AUD, alcohol use disorder; HCT-CI, hematopoietic cell transplantation comorbidity index; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; ULN, upper limit of normal (according to institution).

Multivariate analysis was performed for NRM adjusting for all examined variables significant at the P < 0.10 (overall) level in univariate analysis, including disease status at the time of autologous HCT, conditioning regimen, HCT-CI, age, and history of AUD (Table 2). The patient-specific factors HCT-CI ≥ 3 (HR 1.94; CI 1.0 – 3.7, P = 0.05), a history of AUD (HR 2.17; CI 1.3 – 3.7, P = 0.004), and age (HR 1.29; CI 1.0 – 1.6, P = 0.02) each retained association with NRM (Table 3 and Supplementary Table 1).

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis showing the associations between patient-specific factors and non-relapse mortality.

| Non-relapse mortality | ||

|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | |

| HCT-CI | ||

| 0 | 1.0 | |

| 1–2 | 1.15 (0.6–2.3) | 0.69 |

| ≥ 3 | 1.94 (1.0–3.7) | 0.05 |

| Age | ||

| Per decade | 1.29 (1.0 – 1.6) | 0.02 |

| AUD | ||

| No | 1.0 | |

| Yes | 2.17 (1.3–3.7) | 0.004 |

AUD, alcohol use disorder; HCT-CI, hematopoietic cell transplantation comorbidity index; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; ULN, upper limit of normal (according to institution).

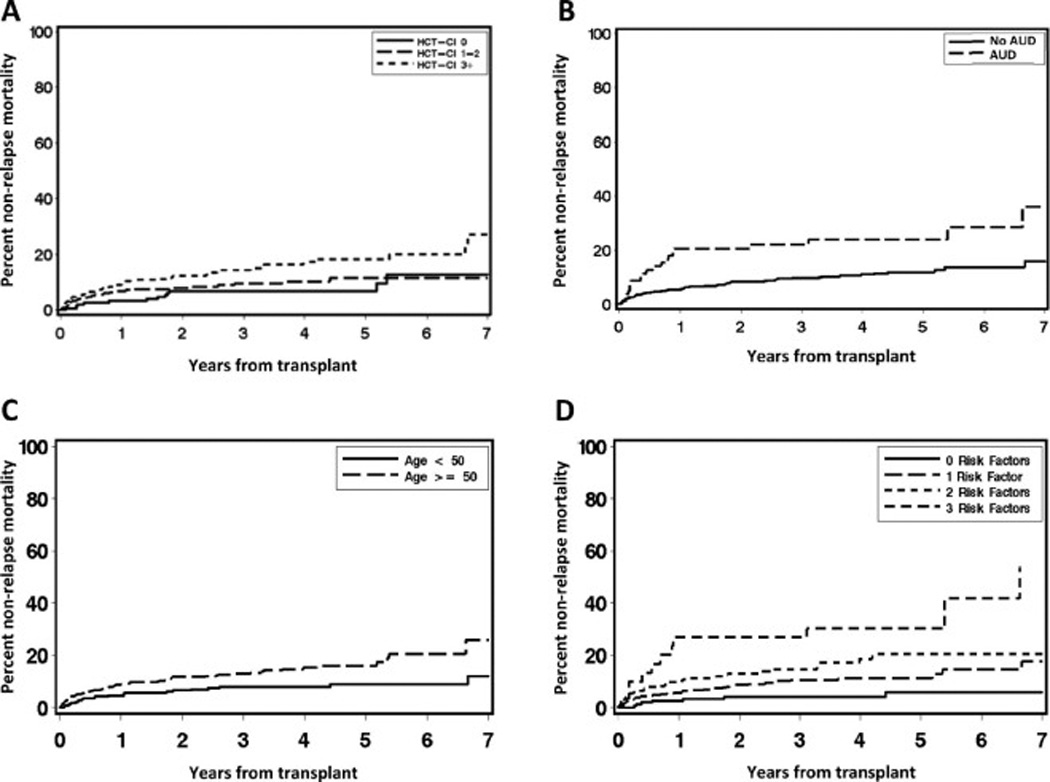

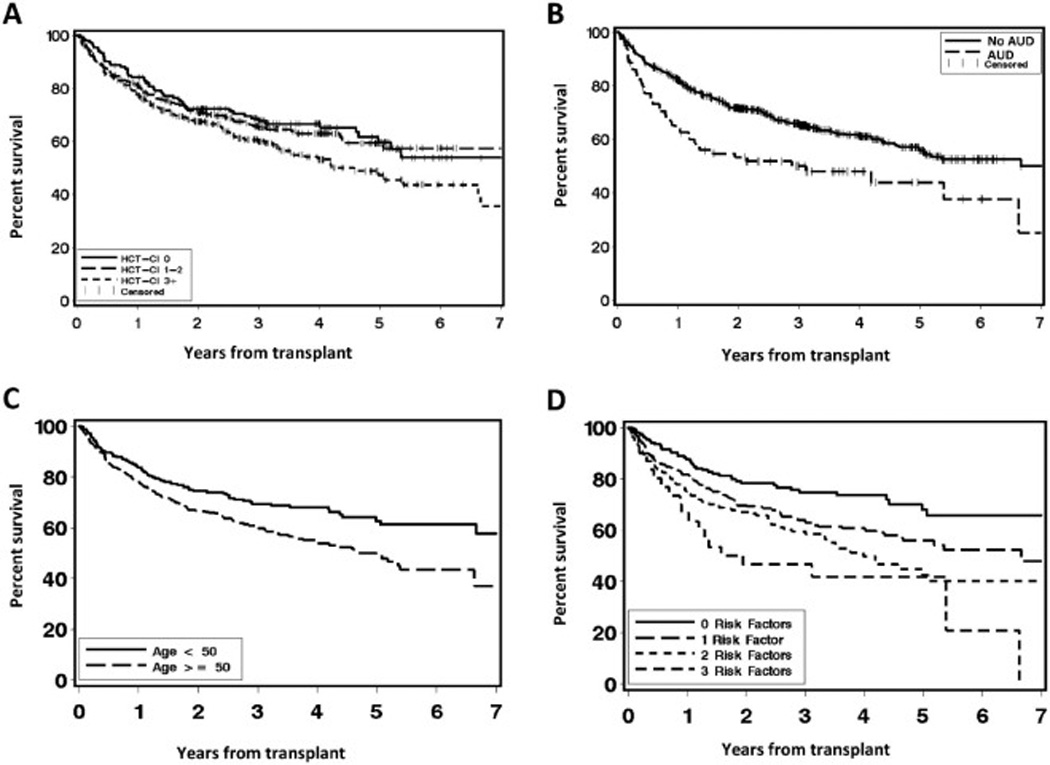

The effect of these patient-specific factors on NRM and overall survival (OS) is shown in Fig 1A–C and Fig 2A–C, respectively. Combining HCT-CI with AUD and age into a patient-specific composite risk factor score stratified patients into three groups: those with zero risk factors (N = 158, 21%), 1 risk factor (N = 359, 48%), 2 risk factors (N = 206, 27%), and 3 risk factors (N = 31, 4%). NRM at 5 years increased across these groups from 6% in patients with zero risk factors to 11% (1 risk factor), 20% (2 risk factors), and 30% (3 risk factors). Notably NRM at 100 days, a surrogate for treatment-related mortality (TRM), steadily increased across these groups from 1% in patients with 0 risk factors to 3% in patients with 1 risk factor and 6% in patients with 2 risk factors, but then jumped to 27% in patients with all 3 risk factors (Fig 1D). The c-statistic estimate for NRM was 0.59 for HCT-CI and improved to 0.63 for HCT-CI plus AUD to 0.64 for all 3 risk factors combined. The number of risk factors also associated with OS (Fig 2D), and ranged from 68% in patients with zero risk factors down to 56% in patients with 1 risk factor, 43% in patients with 2 risk factors, and 42% in patients with all 3 risk factors.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

To better understand the biologic basis underlying the effect of AUD on NRM, we performed correlation analyses between AUD and additional co-variables, where available (Table 4). AUD was significantly associated with male sex (P < 0.001), elevated aspartate aminotransferase (P = 0.007), and depression (P = 0.005); there was a suggestion of association with hepatic comorbidity (P = 0.10) and no association with disease histology (P = 0.95) or remission status at the time of transplant (P = 0.98).

Table 4.

Correlation of alcohol use disorder with elements of the hematopoietic cell transplant comorbidity index and with variables of disease and treatment.

| N | % AUD | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 516 | 14 | |

| Female | 238 | 3 | < 0.0001 |

| Hepatic comorbidity | |||

| None | 536 | 8 | |

| Mild | 86 | 15 | |

| Moderate / Severe | 15 | 13 | 0.10 |

| Missing | 117 | ||

| Liver enzymes | |||

| Normal AST | 185 | 7 | |

| AST > ULN | 20 | 25 | 0.007 |

| Normal ALT | 138 | 8 | |

| ALT > ULN | 67 | 10 | 0.56 |

| Normal Bilirubin | 200 | 9 | |

| Bilirubin > ULN | 5 | 0 | 0.48 |

| Missing | 549 | ||

| Depression | |||

| Yes | 119 | 16 | |

| No | 518 | 8 | 0.005 |

| Missing | 117 | ||

| Disease histology | |||

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 159 | 10 | |

| Diffuse large B cell lymphoma | 334 | 10 | |

| Mantle cell lymphoma | 127 | 11 | |

| Follicular lymphoma | 102 | 13 | |

| T-cell lymphoma / Other | 32 | 13 | 0.95 |

| Disease status | |||

| Relapse / refractory | 428 | 11 | |

| CR / PR | 319 | 11 | 0.98 |

AUD, alcohol use disorder; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ULN, upper limit of normal (according to institution). Hepatic comorbidity was scored as mild for chronic hepatitis or for bilirubin > ULN to 1.5 × ULN, or AST/ALT > ULN to 2.5 × ULN. Hepatic comorbidity was scored as moderate / severe for cirrhosis or for bilirubin > 1.5 × ULN, or AST/ALT > 2.5 × ULN, per published criteria [2]. Response to chemotherapy was defined as chemo-sensitive if a complete remission (CR) or a partial remission (PR) had been achieved in response to last salvage therapy given prior to autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation according to standard criteria [11, 12].

Ninety patients died after autologous HCT without known or suspected relapse of lymphoma; of these the primary cause of death was identifiable in N = 59 patients with the most common being infection (N = 19), second malignancy (N = 16), and pulmonary disease not primarily attributed to infection (N = 13). Liver failure from sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (SOS) was recorded as cause of death in N = 4 patients. Of these cases, 29% who died from infection, 38% who died of pulmonary disease not primarily attributed to infection, 25% who died from SOS, and 6% who died from second malignancy had AUD.

To investigate whether the effects of patient-specific factors associated with mortality might be augmented or attenuated by the conditioning regimen, an interaction analysis between these sets of variables was performed (data not shown). No association was apparent between the conditioning regimen and NRM when stratified by the risk factors individually or when stratified by the composite risk factor score. Further, HCT-CI did not associate with conditioning regimen used: for example, BEAM was used in 19% of patients with an HCT-CI of zero and in 24% of patients with and HCT-CI of ≥ 3 (P = 0.39); TBI-based therapy was used in 39% of patients with a HCT-CI of zero and in 37% of patients with an HCT-CI of ≥ 3 (P = 0.77) (Supplementary Table S2).

Discussion

Establishing a predictive risk-model of patient fitness can improve treatment selection and patient counseling before autologous HCT for treatment of lymphoma. Here, we show that among patient-specific factors, higher HCT-CI scores, a history of AUD, and increasing age independently increase the risk of NRM following autologous HCT. Patients with 2 (27% of patients) or 3 (4% of patients) risk factors have higher risk for 5-year NRM (20% and 30%, respectively). Other patient-specific factors, including history of smoking, had no independent impact on NRM.

Patient age has been studied relatively extensively in this context and has previously been shown to have little association with treatment related mortality (TRM) [7, 8, 16–18], suggesting that chronological age is significantly limited as a surrogate for patient tolerance of cancer therapy, including HCT [19, 20]. These aforementioned studies examined age either in an isolated cohort compared to historical controls or as a dichotomized variable. In our analysis, age was stratified by decade and, as such, added a statistically significant risk to NRM (HR 1.29, CI 1.0 – 1.6, P = 0.02). Indeed, if age is dichotomized in our cohort using the median value (age 53 years old) as a cutoff, it does not retain a statistically significant association with NRM in multivariate analysis (data not shown). Here, the incremental impact of advancing age on NRM is best captured through its analysis stratified by decade. Future evaluations of the impact of age might consider this possibility. Whether chronological age per se or the aging-related health problems in the physical, cognitive, social, and emotional domains are responsible for the increased risk of mortality requires further investigation.

Previously, Wildes et al. used the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) to assess impact of comorbidities on outcomes of autologous HCT. The CCI correlated with TRM (P = 0.03) and OS (P = 0.013) in a cohort of 152 patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) treated with autologous HCT following BEAM conditioning [21]. Compared with the CCI, the HCT-CI represents a more comprehensive evaluation of patient organ functions [2]. The HCT-CI has been used in two relatively small retrospective studies examining TRM after autologous HCT [5, 8]. These studies identified no association of the HCT-CI with TRM, though the number of patients with lymphoma studied (N = 202 and 259, respectively) was relatively modest. A recent prospective investigation from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) evaluated the predictive ability of the HCT-CI across more than 11,000 recipients of autologous HCT [7]. In a subset of 3,363 patients with lymphoma, HCT-CI scores of ≥ 3 were shown to predict NRM (HR 1.56, CI 1.12 – 2.17; P = 0.009). Our results are in agreement (HR 1.94, CI 1.0 – 3.7, P = 0.05), suggesting that the relatively large number of patients in the current study (N = 754) allows for appropriate evaluation of the model performance. In addition, similar to the CIBMTR study, we find that patients with HCT-CI scores of 1 or 2 tolerated autologous HCT as well as those with a score of 0 (HR 1.15, [CI 0.6 – 2.3, P = 0.69]). This result demonstrates the sensitivity of the discriminative capacity of the model to the type of therapy given since scores of 1–2 are associated with higher risk of NRM in high-dose allogeneic HCT [2].

A history of AUD, defined per standardized criteria [13], is associated with higher post- HCT NRM (HR 2.17, CI 1.3 – 3.7, P = 0.004). While AUD was correlated with pre-HCT depression and elevated AST, its impact on mortality was independent from that of the HCT-CI, suggesting that AUD may reflect an element of patient fitness not directly captured by the HCTCI. AUD should therefore be considered carefully before autologous HCT evaluation and factored into patient counseling. A single small study previously showed that substance abuse (alcohol in 70% of patients) in 17 patients given bone marrow transplantation (autologous, N = 4; allogeneic, N = 13) correlated negatively with OS [22].

Reasons behind the independent impact of AUD on NRM are not fully clear. AUD may cause hepatic, cardiopulmonary, bone marrow, or immune damage too subtle to be diagnosed biochemically or clinically before treatment [23–26]. Along those lines, we found that AUD was relatively prominent among patients experiencing NRM from infectious (26%) or other pulmonary complications (38%). Alternatively, AUD might be reflective of abnormal behavioral characteristics and psychological stressors affecting outcomes after HCT [27–32], including less social support or reduced compliance. AUD has previously been shown to contribute to medication noncompliance in various chronic illnesses [33, 34]. While suboptimal medication compliance has been observed in up to two-thirds of long-term survivors following allogeneic HCT [35], studies on patterns of medication compliance in the early post-transplant period are lacking.

The simple combination of higher HCT-CI scores, AUD, and increasing age could be used in the clinic to predict rates of NRM and overall mortality after autologous HCT for lymphoma. Future studies should focus on improving the management of patients with combined 2 or 3 of these risk factors. Risk-mitigation strategies would include exploring tolerable conditioning regimens, novel non-transplant therapies, or interventions aimed at alleviating the detrimental effects of comorbidities and AUD.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Higher HCT-CI score, alcohol use disorder, and older age each contribute risk to NRM

In a combined model, multiple risk factors associate with markedly increased mortality

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the patients who participated in this study.

Financial disclosure: This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health [Grant Numbers CA018029, HL088021 to M.L.S., T32 HL007093-38 to S.A.G., T32 HL007093-38 to J.E.V., K24 CA184039 to A.K.G]; American Cancer Society [Research Scholar Grant No. RSG-13-084-01-CPHPS to M.L.S.]; and the Patient-Centered Outcome Research Institute [Contract No. CE-1304-7451 to M.L.S.].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplementary Material for Online Publication

- Supplementary Table S1. Clinical characteristics of study cohort.

- Supplementary Table S2. Most common conditioning regimens stratified by HCT-CI.

Conflict of interest statement: There are no conflicts of interest to report.

Author contributions:

MLS designed the research study. SAG, JEV, TRC, and MLS collected data for the study. BES contributed to the study design and performed statistical analyses. TRC, AKG, LAH, WIB, DGM, OWP, and RS coordinated the study at their respective centers. SAG, JEV, TRC, BES, AKG, LAS, JSM, WIB, DGM, OWP, RS, and MLS contributed to the interpretation of the results. SAG, JEV, and MLS drafted the article. TRC, AKG, and JSM edited the article.

References

- 1.Gisselbrecht C, Glass B, Mounier N, et al. Salvage regimens with autologous transplantation for relapsed large B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28:4184–4190. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sorror ML, Maris MB, Storb R, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT)-specific comorbidity index: a new tool for risk assessment before allogeneic HCT. Blood. 2005;106:2912–2919. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farina L, Bruno B, Patriarca F, et al. The hematopoietic cell transplantation comorbidity index (HCT-CI) predicts clinical outcomes in lymphoma and myeloma patients after reduced-intensity or non-myeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Leukemia. 2009;23:1131–1138. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pollack SM, Steinberg SM, Odom J, Dean RM, Fowler DH, Bishop MR. Assessment of the hematopoietic cell transplantation comorbidity index in non-Hodgkin lymphoma patients receiving reduced-intensity allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaglowski SM, Ruppert AS, Hofmeister CC, et al. The hematopoietic stem cell transplant comorbidity index can predict for 30-day readmission following autologous stem cell transplant for lymphoma and multiple myeloma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49:1323–1329. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2014.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saad A, Mahindra A, Zhang MJ, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplant comorbidity index is predictive of survival after autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation in multiple myeloma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20:402–408. e401. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.12.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sorror ML, Logan BR, Zhu X, et al. Prospective Validation of the Predictive Power of the Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Comorbidity Index: A CIBMTR Study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dahi PB, Tamari R, Devlin SM, et al. Favorable outcomes in elderly patients undergoing high-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplantation for non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20:2004–2009. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sorror ML. How I assess comorbidities before hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2013;121:2854–2863. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-09-455063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen J. Weighted kappa: nominal scale agreement with provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychological bulletin. 1968;70:213–220. doi: 10.1037/h0026256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, et al. Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. NCI Sponsored International Working Group. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1999;17:1244. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, et al. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:579–586. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hasin D. Classification of alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Res Health. 2003;27:5–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gooley TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, Storer BE. Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks: new representations of old estimators. Statistics in medicine. 1999;18:695–706. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<695::aid-sim60>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harrell FE, Jr, Lee KL, Califf RM, Pryor DB, Rosati RA. Regression modelling strategies for improved prognostic prediction. Statistics in medicine. 1984;3:143–152. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780030207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chihara D, Izutsu K, Kondo E, et al. High-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation for elderly patients with relapsed/refractory diffuse large B cell lymphoma: a nationwide retrospective study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20:684–689. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jantunen E, Canals C, Rambaldi A, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation in elderly patients (>or =60 years) with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: an analysis based on data in the European Blood and Marrow Transplantation registry. Haematologica. 2008;93:1837–1842. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gopal AK, Gooley TA, Golden JB, et al. Efficacy of high-dose therapy and autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in adults 60 years of age and older. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;27:593–599. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson M. Chemotherapy treatment decision making by professionals and older patients with cancer: a narrative review of the literature. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2012;21:3–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2011.01294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Popplewell LL, Forman SJ. Is there an upper age limit for bone marrow transplantation? Bone Marrow Transplant. 2002;29:277–284. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wildes TM, Augustin KM, Sempek D, et al. Comorbidities, not age, impact outcomes in autologous stem cell transplant for relapsed non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14:840–846. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang G, Antin JH, Orav EJ, Randall U, McGarigle C, Behr HM. Substance abuse and bone marrow transplant. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1997;23:301–308. doi: 10.3109/00952999709040948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhatty M, Pruett SB, Swiatlo E, Nanduri B. Alcohol abuse and Streptococcus pneumoniae infections: consideration of virulence factors and impaired immune responses. Alcohol. 2011;45:523–539. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2011.02.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clark BJ, Williams A, Feemster LM, et al. Alcohol screening scores and 90-day outcomes in patients with acute lung injury. Critical care medicine. 2013;41:1518–1525. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318287f1bb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Wit M, Jones DG, Sessler CN, Zilberberg MD, Weaver MF. Alcohol-use disorders in the critically ill patient. Chest. 2010;138:994–1003. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Molina PE, Happel KI, Zhang P, Kolls JK, Nelson S. Focus on: Alcohol and the immune system. Alcohol Res Health. 2010;33:97–108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoodin F, Uberti JP, Lynch TJ, Steele P, Ratanatharathorn V. Do negative or positive emotions differentially impact mortality after adult stem cell transplant? Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;38:255–264. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoodin F, Weber S. A systematic review of psychosocial factors affecting survival after bone marrow transplantation. Psychosomatics. 2003;44:181–195. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.44.3.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knight JM, Lyness JM, Sahler OJ, Liesveld JL, Moynihan JA. Psychosocial factors and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: potential biobehavioral pathways. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:2383–2393. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knight JM, Moynihan JA, Lyness JM, et al. Peri-transplant psychosocial factors and neutrophil recovery following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. PLoS One. 2014;9:e99778. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sullivan AK, Szkrumelak N, Hoffman LH. Psychological risk factors and early complications after bone marrow transplantation in adults. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1999;24:1109–1120. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loberiza FR, Jr, Rizzo JD, Bredeson CN, et al. Association of depressive syndrome and early deaths among patients after stem-cell transplantation for malignant diseases. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20:2118–2126. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bryson CL, Au DH, Sun H, Williams EC, Kivlahan DR, Bradley KA. Alcohol screening scores and medication nonadherence. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:795–804. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-11-200812020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kalichman SC, Grebler T, Amaral CM, et al. Viral suppression and antiretroviral medication adherence among alcohol using HIV-positive adults. Int J Behav Med. 2014;21:811–820. doi: 10.1007/s12529-013-9353-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kirsch M, Gotz A, Halter JP, et al. Differences in health behaviour between recipients of allogeneic haematopoietic SCT and the general population: a matched control study. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49:1223–1230. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2014.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.